Abstract

Mutations in the genes encoding enzymes responsible for the incorporation of d-Ala into the cell wall of Lactococcus lactis affect autolysis. An L. lactis alanine racemase (alr) mutant is strictly dependent on an external supply of d-Ala to be able to synthesize peptidoglycan and to incorporate d-Ala in the lipoteichoic acids (LTA). The mutant lyses rapidly when d-Ala is removed at mid-exponential growth. AcmA, the major lactococcal autolysin, is partially involved in the increased lysis since an alr acmA double mutant still lyses, albeit to a lesser extent. To investigate the role of d-Ala on LTA in the increased cell lysis, a dltD mutant of L. lactis was investigated, since this mutant is only affected in the d-alanylation of LTA and not the synthesis of peptidoglycan. Mutation of dltD results in increased lysis, showing that d-alanylation of LTA also influences autolysis. Since a dltD acmA double mutant does not lyse, the lysis of the dltD mutant is totally AcmA dependent. Zymographic analysis shows that no degradation of AcmA takes place in the dltD mutant, whereas AcmA is degraded by the extracellular protease HtrA in the wild-type strain. In L. lactis, LTA has been shown to be involved in controlled (directed) binding of AcmA. LTA lacking d-Ala has been reported in other bacterial species to have an improved capacity for autolysin binding. Mutation of dltD in L. lactis, however, does not affect peptidoglycan binding of AcmA; neither the amount of AcmA binding to the cells nor the binding to specific loci is altered. In conclusion, d-Ala depletion of the cell wall causes lysis by two distinct mechanisms. First, it results in an altered peptidoglycan that is more susceptible to lysis by AcmA and also by other factors, e.g., one or more of the other (putative) cell wall hydrolases expressed by L. lactis. Second, reduced amounts of d-Ala on LTA result in decreased degradation of AcmA by HtrA, which results in increased lytic activity.

AcmA, the major autolysin of Lactococcus lactis MG1363, is responsible for stationary phase cellular lysis and is involved in cell separation of this organism (9). The enzyme consists of two domains: the N-terminal region contains an N-acetyl-glucosaminidase active site domain (9; A. Steen, G. Buist, G. Horsburgh, S. J. Foster, O. P. Kuipers, and J. Kok, unpublished data) while the C-terminal region contains three so-called LysM domains, with which it specifically binds to peptidoglycan of L. lactis and of other gram-positive bacteria (49). Peptidoglycan, the major cell wall component in bacteria and the substrate of AcmA, consists of glycan strands cross-linked by peptide side chains. The peptide chain contains alternating l- and d-amino acids. d-Alanine (d-Ala) is incorporated into the peptidoglycan peptide moiety as a d-Ala-d-Ala dipeptide, where it is involved in cross-linking of adjacent peptidoglycan strands. In many bacteria alanine racemase is responsible for the synthesis of d-Ala from l-Ala, the naturally occurring alanine isomer (53). Bacillus subtilis expresses at least one alanine racemase: Dal (14). A dal mutant is dependent on d-Ala supplementation to be able to grow in a rich medium; cells start to lyse in the absence of d-Ala (4, 14, 20). In minimal medium the mutant is d-Ala dependent when l-Ala is supplemented, suggesting that a second, l-Ala-repressible racemase is present (4, 14). Lactobacillus plantarum probably expresses only one alanine racemase, as an alr mutant is totally dependent on d-Ala for growth (22). d-Ala deprivation of an alr mutant of L. plantarum resulted in growth arrest, a rapid loss of cell viability, and an aberrant cell morphology (43). Electron microscopy analyses showed that mainly the cell septum is affected in this mutant. Like L. plantarum alr, L. lactis alr is totally dependent on the addition of d-Ala to the growth medium (23); when d-Ala was removed from the growth medium when the cells were in exponential growth phase, L. lactis alr growth was impaired and the culture started to lyse (17). The alr gene was used as a food-grade plasmid selection marker in the alr mutants of L. plantarum and L. lactis, complementing the d-Ala auxotrophy (7). Moreover, the alr mutants of L. plantarum and L. lactis were used in a mucosal vaccination study, in which these two mutants were shown to enhance the mucosal delivery of the tetanus toxin fragment C model antigen in mice (17).

Although peptidoglycan covers the whole surface of L. lactis, AcmA binds to lactococcal cells at specific loci, namely around the poles and septum of the cell, exactly those places where cell lysis has been shown to start (35, 49). Trichloroacetic acid treatment of cells causes binding of AcmA over the whole cell surface. Lipoteichoic acid (LTA) is a candidate-hindering component that is removed by this treatment, as it seems to be present in L. lactis at those positions where AcmA is not able to bind (49). LTA is a secondary cell wall polymer suggested to be involved in the control of autolysin activity (5, 15), in determining the electrochemical properties of the cell wall (42), in establishing a magnesium ion concentration (2, 21, 26, 31), and in determining the physicochemical properties of the cytoplasmic membrane (18). LTA can be modified by various compounds, such as glycosyl residues (15) and d-Ala esters (1).

In gram-positive bacteria, the products of the dlt operon are involved in d-alanylation of LTA. The operon comprises four genes: dltA, encoding d-alanine-d-alanine carrier protein ligase (Dcl), the product of which is an activated d-Ala; dltC, specifying the d-alanyl-carrier protein (Dcp); dltB, which encodes a putative transmembrane protein involved in the secretion of the activated d-alanine; and dltD, encoding a protein that facilitates the binding of Dcp and Dcl for ligation with d-Ala and has thioesterase activity for mischarged d-alanyl-acyl carrier proteins (11, 28, 38). A link between d-alanylated LTA and autolysin activity has been reported earlier: autolysis of B. subtilis dltA, dltB, dltC, or dltD mutants was enhanced, and the bacteria were more susceptible to methicillin, which resulted in accelerated cell wall lysis, a faster loss of cell viability, and a slower recovery of the cells in the post-antibiotic phase (52). Furthermore, the absence of d-Ala in the LTA of a dltB as well as a dltD mutant of B. subtilis causes an increase in the net negative charge of the cell wall, resulting in an increase in the rate of posttranslational folding of some exported proteins (27). In the absence of d-alanylation, the yield of secreted recombinant anthrax protective antigen was increased 2.5-fold (50). B. subtilis cell growth, basic metabolism, cellular content of phosphorus-containing compounds, cell separation, and surface charge were not altered (52). Insertional mutagenesis in the dlt operon of Staphylococcus aureus resulted in methicillin resistance and an increased autolysis (36). In L. lactis subsp. lactis IL1403, the dlt operon comprises four genes: dltA, dltB, dltC, and dltD (6). An L. lactis dltD mutant was obtained by random insertion mutagenesis and screening for UV-sensitive mutants (13). Apart from its UV sensitivity, the dltD mutant was characterized by having a lower plasmid transfer rate during conjugation, and it was possible to make the mutant electrocompetent without the addition of glycine to the growth medium (13). Insertion mutagenesis of dltA of L. lactis resulted in secretion defects of the staphylococcal nuclease, which was used as a reporter for secretion. The secretion defect is most probably caused by an entrapment of the reporter protein in the cell wall, which could be the result of the interaction of the positively charged nuclease with the expected negatively charged cell wall of the dltA mutant (41).

In this paper we show that mutations in the alr and dltD genes of L. lactis differentially affect autolysis, and we investigate the role of the major autolysin AcmA therein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. L. lactis was grown at 30°C in M17 broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) or on twofold diluted M17 (1/2M17) medium containing 0.5% glucose (GM17 or G1/2M17, respectively). When appropriate d-alanine was added to reach a 2 mM end concentration. For plasmid selection in L. lactis, chloramphenicol or erythromycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.) was added (each to a concentration of 5 μg/ml). For plasmid selection in Escherichia coli, erythromycin or ampicillin (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at a concentration of 100 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| L. lactis strains | ||

| MG1363 | Plasmid-free and prophage-cured derivative of NCDO712 | 16 |

| NZ3900 | MG1363 derivative, used as wild-type control (ΔlacF pepN::nisR-nisK) | 12 |

| PH3960 | NZ3900 derivative carrying a deletion in alr (Δalr) | This study |

| GB3960 | PH3960 derivative carrying a deletion in acmA (Δalr acmAΔ1) | This study |

| MG1363acmAΔ1 | MG1363 derivative carrying a deletion in acmA (acmAΔ1) | 9 |

| MG1363 (dltD) | MG1363 derivative carrying an ISS1 insertion in dltD (dltD::ISS1) | 13 |

| MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) | MG1363 (dltD) derivative carrying a deletion in acmA (dltD::ISS1 acmAΔ1) | This study |

| NZ9000 | MG1363 pepN::nisRK | 30 |

| NZ9700 | Nisin producing transconjugant of NZ9000 containing the nisin-sucrose transposon Tn5276 | 29 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pINTAA | Integration plasmid used for the introduction of a 701-bp deletion in acmA; Emr | 9 |

| pGIP011 | PJDC9 derivative containing an internal fragment of alr from MG1363; Emr | 23 |

| pGIP016 | PGIP011 derivative containing an in frame deletion of alr from MG1363; Emr | This study |

| pNG3041 | Plasmid used for the nisin induced overexpression of MSA2cA; Cmr | Laboratory collection |

Chemicals and enzymes.

All chemicals used were of analytical grade and, unless indicated otherwise, were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Enzymes for molecular biology were purchased from Roche Molecular Biochemicals (Mannheim, Germany) and used according to the suppliers' instructions.

DNA manipulations and transformation.

Molecular cloning techniques were performed essentially as described by Sambrook et al. (47). Electrotransformation of E. coli and L. lactis was performed by using a gene pulser (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.) as described by Zabarovsky and Winberg (54) and Leenhouts and Venema (32), respectively. Mini-preparations of plasmid DNA from E. coli and L. lactis were obtained by the alkaline lysis method as described by Sambrook et al. (47) and Seegers et al. (48), respectively. PCR products were purified by using a High Pure PCR purification kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

Construction of an alanine racemase-deficient mutant and acmA knockouts in L. lactis.

The suicide plasmid used to generate the alr disruption was constructed as follows. A 0.68-kb PCR product was amplified from MG1363 chromosomal DNA by using primers derived from the L. lactis IL1403 genome sequence (LLALR3, 5′-CCTGTCGAAAATATTTATAAAGCTG, and LLALR4, 5′-CGAGGATCCCCAAATTTCCGCATTAGGGTGAATATG [BamHI site in italics]). This DNA fragment was restricted with PstI and BamHI and cloned into the corresponding sites of the pBLUESCRIPT SK+ (Stratagene GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) plasmid. The DNA fragment was next recovered as a SalI-BamHI fragment and cloned into the corresponding sites of the suicide plasmid pGIP011 (described in reference 23) to generate plasmid pGIP016. The resulting plasmid contains an in-frame deletion of the alr gene (30 nucleotides), resulting in the removal of the pyridoxal-P binding site of the Alr enzyme. The stable alr mutant was constructed by two successive crossover events. First-step integrant candidates of strain NZ3900 (isogenic to MG1363) resulting from a single crossover recombination of the pGIP016 suicide vector at the alr locus were selected on GM17 plates containing both erythromycin and d-Ala. Three d-Ala auxotroph candidates were obtained and were grown in GM17 (plus d-Ala) without erythromycin during 120 generations in order to allow excision of the plasmid through intrachromosomal recombination. A total of 1,500 colonies (GM17 plus d-Ala) were examined by replica plating on GM17 containing both d-Ala and erythromycin or on GM17 without d-Ala. Twenty-seven erythromycin-sensitive candidates were obtained, one of which was a d-Ala auxotroph. This mutant strain (named PH3960) was retained for detailed phenotypic analysis following further validation by PCR amplification and Southern blotting (data not shown).

The acmA deletion derivatives of L. lactis MG1363 (dltD) and L. lactis PH3960 (Δalr) were obtained by replacement recombination with plasmid pINTAA, replacing acmA with the acmAΔ1 gene which has an internal deletion, as described by Buist et al. (9).

Enzyme assays and optical density measurements.

AcmA activity was visualized on G1/2M17 agar plates containing 0.2% autoclaved lyophilized Micrococcus lysodeikticus 4698 cells (Sigma-Aldrich) as halos around L. lactis colonies after overnight growth at 30°C.

X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase (PepX) was measured as described by Buist et al. (10). Similar patterns were obtained in three independent experiments. Optical densities at 600 nm (OD600) of cell cultures were measured in a Novaspec II spectrophotometer (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden).

To study lysis caused by AcmA, 1 ml of an overnight culture of L. lactis MG1363acmAΔ1 or L. lactis MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) was mixed with 1 ml of AcmA-containing supernatant of an overnight L. lactis MG1363 culture. After overnight incubation at 37°C, the amount of PepX released from the cells was measured as described above.

Lactate dehydrogenase activity in the supernatant was determined by using pyruvate as a substrate as previously reported (23). Aliquots (1 ml) of the culture were withdrawn at various time points, cells were removed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was stored immediately at −20°C until enzyme assays were performed. One unit of activity corresponds to the oxidation of 1 μmol of NADH per min.

Total protein concentration was measured by the Bio-Rad protein assay method.

Triton X-100 induced lysis under nongrowing conditions.

The procedure of Triton X-100-induced lysis was performed as described previously (46) with the following modifications. Cells were grown in GM17 for 16 h at 30°C, harvested by centrifugation (12,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature), washed three times with an equal volume of a potassium-sodium phosphate (K-NaPO4) buffer (10 mM; pH 6.5) and resuspended in K-NaPO4 buffer (200 mM; pH 6.5) containing 0.05% Triton X-100 (vol/vol). The cell suspension was incubated at 37°C under agitation, and autolysis was monitored by the decrease in OD600 in time.

SDS-PAGE, AcmA zymograms, and Western hybridization.

L. lactis cell and supernatant samples were prepared as described previously (10). AcmA activity was detected by a zymogram staining technique by using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) with 12.5 or 17.5% polyacrylamide gels containing 0.15% autoclaved, lyophilized M. lysodeikticus ATCC 4698 cells as described before (9). The standard low-range and prestained low- and high-range SDS-PAGE molecular weight markers of Bio-Rad were used as references. Proteins were transferred from SDS-10% polyacrylamide gels to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Roche Molecular Biologicals) as described by Towbin et al. (51). MSA2 antigen was detected with 10,000-fold diluted rabbit polyclonal anti-MSA2 antiserum (45), and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Pharmacia) by using an ECL chemiluminescence detection system and protocol (Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.).

Binding of MSA2cA and AcmA to L. lactis cells.

Binding of the MSA2cA fusion protein was studied by growing L. lactis NZ9000 (pNG3041) at 30°C until an OD600 of 0.4 was reached. L. lactis NZ9000 (pNG3041) was induced with nisin by adding a 1/1000 volume of the supernatant of the nisin producer L. lactis NZ9700 and incubated at 30°C for 2 h. The cells of 1 ml of L. lactis MG1363acmAΔ1 or L. lactis MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) culture were resuspended in 1 ml of supernatant of the induced L. lactis NZ9000 (pNG3041) culture. The suspensions were incubated for 5 min at room temperature and spun down, after which the cells were washed with 1 ml of fresh 1/2M17 medium and resuspended in 100 μl of denaturation buffer (3). After boiling for 5 min, the samples were subjected to SDS-10% PAGE, followed by Western hybridization by using anti-MSA2 antibodies. The binding of AcmA to lactococcal cells was studied by mixing the cells of 1 ml of an overnight culture of L. lactis MG1363acmAΔ1 or L. lactis MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) with 1 ml of AcmA-containing supernatant of an L. lactis MG1363 culture. The suspensions were incubated for 5 min at room temperature and centrifuged. The supernatant (0.5 ml) was mixed with 0.5 ml of an M. lysodeikticus suspension (0.2% in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 5.4). The OD600 of the suspensions were measured at time zero and at 30 min. To determine the maximal amount of AcmA activity present in the MG1363 supernatant, 0.5 ml of L. lactis MG1363 supernatant was mixed with the M. lysodeikticus cells (control suspension). The ΔOD600 of the M. lysodeikticus suspensions with MG1363 supernatant preincubated with wild-type or mutant cells was calculated as a percentage of the ΔOD600 of the control suspension, resulting in the percentage of AcmA that did not bind to the cells. The unbound percentage was then subtracted from 100% to give the bound percentage.

Immunofluorescence microscopy, electron microscopy, and measurement of cell wall and septum thickness.

Immunofluorescence studies to localize MSA2cA on the cell surface of L. lactis were performed as described before (49) by using anti-MSA2 antibodies and Oregon green-labeled secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Oreg.).

Samples for transmission electron microscopy were prepared as follows. Cells (mid-exponential or stationary phase) were harvested by low-speed centrifugation (3,000 × g for 5 min). The cells were washed twice in sodium cacodylate buffer (200 mM; pH 7.3), prefixed in 2.5% (wt/vol) glutaraldehyde and fixed with 1% (wt/vol) OsO4. The samples were embedded in Epon resin (Fluka Chemie, Buchs, Switzerland), and thin sections were prepared by using a Reichert-Jung Ultracut microtome (Milton Keynes, United Kingdom). The sections were stained with 4% (wt/vol) uranyl acetate and then with 0.4% (wt/vol) lead citrate and were examined with a JEOL JEE 1200 EXII electron microscope at 100 kV. Cell wall and septum thickness was measured by using the software program XL Docu version 3.0 (Soft Imaging System GmbH, Munster, Germany).

RESULTS

Mutation of alr in L. lactis increases autolysis.

The stable isogenic L. lactis NZ3900 alr deletion mutant L. lactis PH3960 (Δalr) is only able to grow when d-Ala is present in the growth medium (17, 23). When d-Ala is removed from the growth medium in exponential phase by washing the culture with fresh medium and resuspending the culture in medium without d-Ala, the growth of L. lactis PH3960 (Δalr) is impaired and cell lysis starts (reference 17 and Fig. 1A). Depletion of d-Ala did not affect L. lactis NZ3900 with respect to growth and autolysis. L. lactis PH3960 (Δalr) behaved like the control strain L. lactis NZ3900 in the presence of d-Ala (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Effect of d-Ala depletion on growth and lysis of L. lactis PH3960. (A) Growth and lysis, as measured by following the OD600, of L. lactis strains NZ3900 (control) and PH3960 (Δalr) in the presence and absence of d-Ala. The strains were grown in GM17 supplemented with 2 mM d-Ala until an OD600 of 0.6 was reached. Subsequently, the cultures were split: one half was grown in GM17 with 2 mM d-Ala while the other half was grown without d-Ala. (B) Growth and lysis of PH3960 (Δalr) after d-Ala depletion and in the presence of 0.5 M sucrose or 0.5 M NaCl. Similar results were obtained in independent experiments.

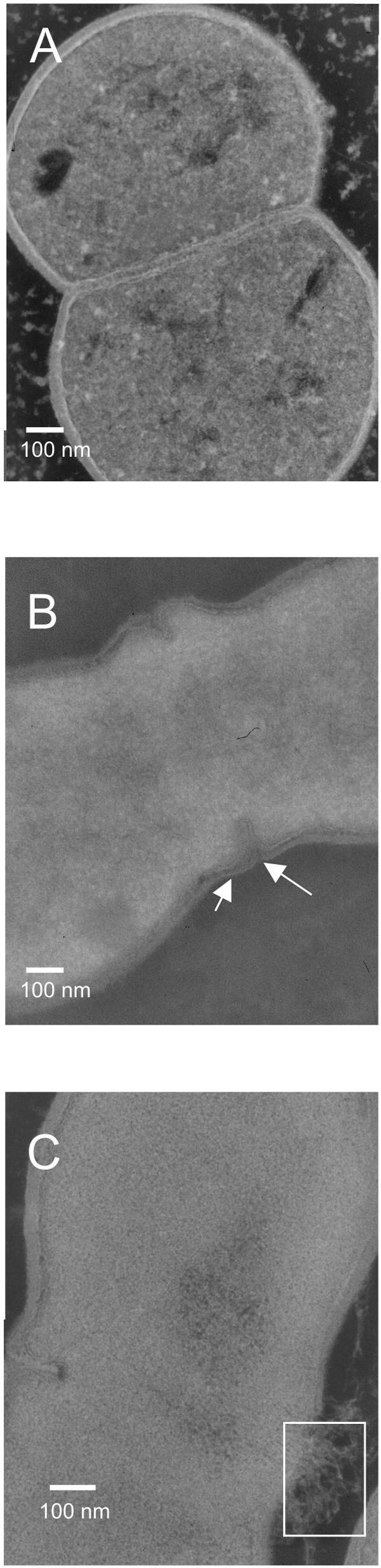

When glycine is added to the growth medium, it will be incorporated in the peptidoglycan in place of d-Ala, affecting the peptidoglycan cross-linking and resulting in a destabilized cell wall (19). Indeed, when glycine was added to the growth medium, more lysis was observed than when no glycine was added, both for the wild-type L. lactis NZ3900 and for strain PH3960 (Δalr) (Table 2). However, strain PH3960 (Δalr) is more sensitive to glycine and lyses to a greater extent than strain NZ3900, even when grown in the presence of d-Ala (Table 2). When d-Ala is depleted, the addition of glycine (1 as well as 2%) increases the lysis of strain PH3960 (Δalr); lysis of strain PH3960 (Δalr) under these conditions was almost complete after 22 h, as evidenced by a very low OD600 (Table 2). To examine whether osmotic stabilizers could reduce lysis of L. lactis PH3960 (Δalr), sodium chloride or sucrose was added at a concentration of 0.5 M during d-Ala starvation. An effect on lysis was observed, as the OD600 of the cultures grown in the presence of the osmotic stabilizers were higher than when no osmotic stabilizers were present (Fig. 1B). Protoplast formation in the presence of 0.5 M NaCl after d-Ala starvation was observed by using a light microscope (data not shown). The morphology of strain PH3960 (Δalr) during d-Ala starvation was studied by using transmission electron microscopy; the septum and cell wall were thinner than those of the wild-type (Fig. 2, compare A and B), and occasionally holes were observed in the septal region (Fig. 2C).

TABLE 2.

Effect of glycine on lysis of L. lactis NZ3900 (control) and L. lactis PH3960 (Δalr) in the presence or absence of d-Alaa

| Strain | % Glycine added | % of maximum OD600

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| With D-Ala | Without D-Ala | ||

| NZ3900 | 0 | 98 | 94 |

| NZ3900 | 1 | 94 | 97 |

| NZ3900 | 2 | 89 | 84 |

| PH3960 (Δalr) | 0 | 99 | 30 |

| PH3960 (Δalr) | 1 | 83 | 5.7 |

| PH3960 (Δalr) | 2 | 60 | 5.9 |

Strains were grown until an OD600 of 0.5 was reached, after which the cultures were split in two, centrifuged, washed once with an equal volume of fresh medium, and resuspended in fresh medium. d-Ala (2 mM) and/or glycine (1 or 2%) were added and growth was followed during 22 h.

FIG. 2.

Effect of d-Ala depletion on the cell integrity. (A) Electron microscopy image of L. lactis NZ3900 in stationary phase. (B) Electron microscopy image of L. lactis PH3960 (Δalr) after 5 h of d-Ala depletion. Arrows show the thinner cell wall around the septum. (C) Electron microscopy image of L. lactis PH3960 (Δalr) after 2 h of d-Ala depletion. The white rectangle shows where release of cytoplasmic material occurs.

The major autolysin AcmA of L. lactis MG1363 binds around the septal region of the cell (49). To study the possible involvement of AcmA in the lysis of L. lactis PH3960 (Δalr), an isogenic acmA alr double mutant was constructed. In the absence of d-Ala, L. lactis GB3960 (Δalr acmAΔ1) still lyses and releases intracellular proteins into its medium, albeit to a much lesser extent than strain PH3960 (Δalr) (Fig. 3). After 20 h of d-Ala starvation, the OD600 of strain GB3960 (Δalr acmAΔ1) was approximately two times higher (Fig. 3) than that of strain PH3960 (Δalr). Total protein release from strain GB3960 (Δalr acmAΔ1) is two times lower than that from strain PH3960 (Δalr) upon d-Ala starvation (Fig. 3). In an acmAΔ1 mutant of L. lactis MG1363, the isogenic parent of all strains used in this study, neither lysis nor a decrease in the OD600 value was observed (Fig. 4A) (9).

FIG. 3.

Growth (OD600, solid lines) and release of cytoplasmic proteins (dashed lines) by L. lactis PH3960 (Δalr) and L. lactis GB3960 (Δalr acmAΔ1). The two strains were grown in GM17 medium with 2 mM d-Ala until exponential phase, after which d-Ala was removed from the growth medium by centrifugation and cells were resuspended in fresh GM17 broth without d-Ala.

FIG. 4.

(A) Effect of AcmA on growth and lysis of L. lactis NZ3900, MG1363acmAΔ1, MG1363 (dltD), and MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1). The OD600 of GM17 cultures of L. lactis was followed for 24 h (solid lines). Lactate dehydrogenase release in culture supernatant of the same strains was measured at time (t) = 7 and t = 22 h (dashed lines). The data are from a single experiment that was representative of two independent analyses in which similar results were obtained. (B) Effect of Triton X-100 on lysis of cell suspensions of L. lactis NZ3900 (control), MG1363acmAΔ1, MG1363 (dltD), and MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1). Cells were harvested, washed, resuspended in phosphate buffer supplemented with 0.05% Triton X-100, and incubated at 37°C. The OD600 of the cell suspensions was followed for 5 h (solid lines). Total protein release in the supernatant of the cell suspensions was measured at t = 0, t = 0.5, and t = 5 h (dashed lines). The data are from a single experiment that was representative of two independent analyses in which similar results were obtained.

The thickness of the septum and cell wall (excluding septum) of the mutant strains was measured. Global cell wall thickness of strains PH3960 (Δalr) and GB3960 (Δalr acmAΔ1) are not affected by the absence of d-Ala. The septum of strain PH3960 (Δalr) is a bit thinner than that of strain NZ3900. Strain GB3960 (Δalr acmAΔ1) has a thinner septum than strain PH3960 (Δalr), which is an effect of the absence of AcmA (Table 3 and see below).

TABLE 3.

Cell wall and septum thickness of the strains used in this studya

| Strain | Thickness (nm)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Cell wall | Septum | |

| MG1363 | 39.9 ± 8.5 | 51.9 ± 3.8 |

| MG1363acmAΔ1 | 34.8 ± 11.6 | 33.2 ± 4.5 |

| MG1363 (dltD) | 29.4 ± 3.9 | 55.4 ± 3.0 |

| MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) | 29.0 ± 2.0 | 37.8 ± 3.1 |

| PH3960 (Δalr) | 32.6 ± 8.9 | 43.8 ± 2.9 |

| GB3960 (Δalr acmAΔ1) | 33.9 ± 6.5 | 33.3 ± 0.8 |

Measurements on L. lactis NZ3900 (control), L. lactis MG1363acmAΔ1, L. lactis MG1363 (dltD), and L. lactis MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) were performed on exponentially growing cells. L. lactis PH3960 (Δalr) and L. lactis GB3960 (Δalr acmAΔ1) were depleted for d-Ala for 5 h before measurements were performed. For measurement the standard deviations are given.

A mutation in dltD affects growth and autolysis of L. lactis.

A mutation in alr affects both peptidoglycan synthesis and LTA decoration with d-Ala, while a mutation in dltD only affects decoration of LTA with d-Ala (37). In L. lactis MG1363 the organization of dltA, dltB, dltC, and dltD and their surrounding genes is identical to that in L. lactis IL1403. L. lactis MG1363 dltD was obtained by insertion of ISS1 in the dltD gene (13), and this mutant was used to investigate the effect of changes in LTA on AcmA activity. Growth and lysis of L. lactis MG1363 (dltD) were followed in time (Fig. 4A). L. lactis MG1363 (dltD) grows more slowly and lyses to a greater extent than strain MG1363, releasing more intracellular protein in the culture supernatant when stationary phase is reached, as attested in the supernatant by an increase in activity of the cytoplasmic enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (Fig. 4A).

As the mutation in dltD clearly affects autolysis, the role of AcmA in this phenomenon was investigated by constructing an isogenic dltD acmA double mutant. Growth and lysis of L. lactis strains MG1363acmAΔ1 and MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) are similar, and no proteins are released (Fig. 4A), which is a clear indication that AcmA is responsible for the increased lysis of MG1363 (dltD). L. lactis MG1363 (dltD) is more sensitive to incubation with Triton X-100 (a lysis inducer) than L. lactis MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) (Fig. 4B). The OD600 of L. lactis MG1363 (dltD) drops dramatically in the first 30 min of incubation compared to the value in the control strain L. lactis NZ3900, and more proteins are released into the supernatant. Only limited lysis is observed for strains MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) and MG1363acmAΔ1, with small amounts of proteins being released under these circumstances.

The mutation of dltD does not affect septum and cell wall thickness (Table 3) and cell shape (data not shown). By contrast, the septa of L. lactis MG1363acmAΔ1 and L. lactis MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) are thinner than that of L. lactis NZ3900. Apparently, AcmA is involved in the synthesis of the septum.

AcmA binding to dltD mutant cells is not affected.

AcmA has to bind to the peptidoglycan of the lactococcal cell wall to be able to lyse the cell (49). It is an enzyme with a high pI of approximately 10 and is, therefore, positively charged at the pH value of the medium (pH 6.8). During growth of L. lactis the pH value drops due to the production of lactate. L. lactis MG1363 (dltD) contains a fivefold reduced amount of d-Ala on its LTA compared to MG1363 (d-Ala to GroP ratio of 5.8% in L. lactis MG1363 [dltD], compared to d-Ala to GroP ratio of 28.5% in L. lactis MG1363; N. Kramer, S. Morath, T. Hartung, E. J. Smid, E. Breukink, J. Kok, and O. P. Kuipers, unpublished data).

The LTA of d-Ala-depleted L. lactis MG1363 (dltD) is expected to have an increased net negative charge, which could possibly allow this mutant to bind, via electrostatic interactions, more AcmA at the pH value of the medium than the wild-type strain. To investigate whether an increase in the binding of AcmA could explain the increase in lysis of L. lactis MG1363 (dltD), equal amounts of exponential phase cells of L. lactis MG1363acmAΔ1 and L. lactis MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) were mixed with an AcmA-containing supernatant of an L. lactis MG1363 culture. After mixing, the cell-AcmA suspensions were centrifuged and the supernatants, containing nonbound AcmA, were mixed with M. lysodeikticus autoclaved cells. The resulting decrease in the OD600 value was taken as a measure of the amount of AcmA present in the supernatants with the original AcmA-containing supernatant set at 100%. Equal amounts of AcmA bound to the cells of L. lactis MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) and L. lactis MG1363acmAΔ1 (Table 4), and lysis of both strains, as measured by the release of the intracellular marker enzyme PepX, was the same (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Quantification of AcmA-binding to L. lactis MG1363acmAΔ1 and L. lactis MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1)a

| Cells added | OD600 reduction | Bound AcmA activity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No cells | 0.053 | 0 |

| MG1363acmAΔ1 | 0.032 | 40 |

| MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) | 0.031 | 42 |

The percentage of AcmA activity from 1-ml supernatant samples that bound to cells from 1-ml culture samples was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Samples containing AcmA were incubated with M. lysodeikticus cells for 30 min. Similar results were obtained in independent experiments.

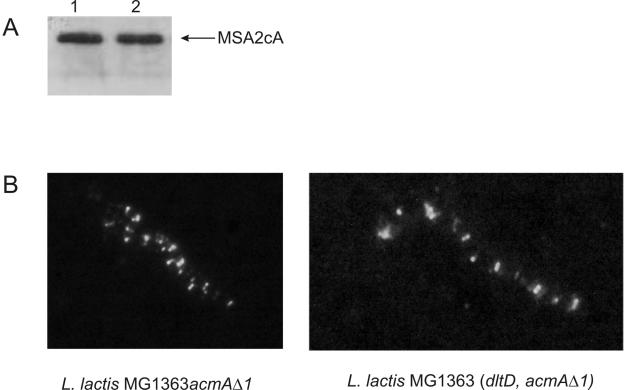

AcmA binds with its C-terminal domain (cA) to specific loci on the lactococcal cell surface, namely, around the septum and at the poles of the cell (49). To examine whether a mutation in dltD affects the localization of AcmA and, consequently, influences its activity, immunofluorescence studies were performed. The MSA2cA protein, which is a fusion of the reporter protein MSA2 of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum and the cA domain of AcmA (49), bound to the same loci on the cell surface of strains MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) and MG1363acmAΔ1 (Fig. 5), indicating that the distribution of AcmA over the cell surface is not altered by the inactivation of dltD. Western hybridization analysis with MSA2-specific antibodies showed that equal amounts of MSA2cA were bound to cells of L. lactis MG1363acmAΔ1 and L. lactis MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

(A) MSA2cA binding to cells. Equal amounts of cells of overnight cultures of L. lactis strains MG1363acmAΔ1 and MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) were mixed with MSA2cA, a fusion protein consisting of the Plasmodium falciparum protein MSA2 and the C-terminal cell wall binding domain of AcmA. The suspensions were incubated for 5 min and centrifuged. The cells were washed once and cell-bound protein was visualized by Western hybridization with anti-MSA2 antibodies. Lane 1, MSA2cA bound to L. lactis MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1); lane 2, MSA2cA bound to L. lactis MG1363acmAΔ1. (B) Localization of MSA2cA on the cell surface of L. lactis. MSA2cA was visualized on cells of L. lactis strains MG1363acmAΔ1 and MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) by immunofluorescence microscopy by using anti-MSA2 antibodies and a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody.

A dltD mutation reduces the breakdown of AcmA.

From studies in B. subtilis, it is known that d-alanylation of LTA affects the stability and breakdown of several heterologous proteins (27). To examine whether the stability of AcmA of L. lactis is affected by a mutation in dltD, supernatants of stationary phase cultures of L. lactis strains MG1363 and MG1363 (dltD) were analyzed on a zymogram containing M. lysodeikticus cell wall fragments (Fig. 6). Next to mature AcmA, several smaller bands of activity of breakdown products of AcmA were observed in the supernatant of L. lactis MG1363, as shown previously (9). In the supernatant of L. lactis MG1363 (dltD) only full-size AcmA was detectable.

FIG. 6.

Zymographic analysis of AcmA activity in the supernatant of L. lactis MG1363 and L. lactis MG1363 (dltD) after culturing for 16 h or 48 h in G1/2M17 at 30°C. dAcmA, breakdown products of AcmA generated by the protease HtrA.

DISCUSSION

d-Ala is essential for L. lactis. An L. lactis alr mutant, which does not synthesize d-Ala from l-Ala, starts to lyse upon d-Ala depletion. This mutant is expected to be defective in cross-linking of the glycan strands, which is necessary for the rigid structure of peptidoglycan, since d-Ala in the disaccharide pentapeptide precursor of peptidoglycan plays an important role in the cross-linking process. In addition, d-alanylation of the LTA in this mutant will be affected since this process also depends on the formation of d-Ala from l-Ala. In an analysis of the lysis of the alr mutant, we show that cell lysis increases when glycine is added to the growth medium, even in the presence of d-Ala, showing that glycine and d-Ala compete; it has been shown that during the biosynthesis of the peptidoglycan precursor (disaccharide pentapeptide), glycine can replace d-Ala in, e.g., L. plantarum and Staphylococcus aureus (19). While L. lactis Alr+ is able to synthesize d-Ala from l-Ala, the L. lactis alr mutant depends on the d-Ala that is added to the culture growth medium. When the d-Ala concentration becomes limiting for the alr mutant, the glycine incorporation into the peptidoglycan will increase. The alr mutant of L. lactis is therefore more sensitive to the addition of glycine than L. lactis Alr+.

Analysis of L. lactis cell morphology by electron microscopy confirms that mutation of alr affects cell wall synthesis; cell wall defects are observed, mainly in the septal region of the cell. The major autolysin, AcmA, is involved in cell separation and has been shown to bind and act in this region (49). We show here that, indeed, AcmA is involved in the increased lysis of L. lactis (alr). To our knowledge, this is the first time that an autolysin is shown to be directly involved in the lysis of mutants defective in peptidoglycan precursor biosynthesis.

The lysis observed in the alr mutant is not fully AcmA mediated. The L. lactis alr acmA double mutant still lyses, albeit to a lesser extent than L. lactis alr. Other factors, e.g., the activity of one or more other cell wall hydrolases, could be involved. Indeed, genes for three homologues of AcmA (AcmB, AcmC, and AcmD) and a putative lytic endopeptidase (YjgB) are present in the genome of L. lactis (6), and recently activity of these peptidoglycan hydrolases has been shown in vitro (24). AcmB has autolytic activity, since an acmB mutant of MG1363 lyses to a lesser extent than its parent (25). Lytic activity of AcmB, however, depends on the presence of AcmA as MG1363 (acmAΔ1 acmB) lyses to the same extent as MG1363acmAΔ1 (25). AcmB is, therefore, not expected to be involved in the lysis of L. lactis GB3960 (Δalr, acmAΔ1) observed in this study.

Since mutating alr will not only affect peptidoglycan synthesis but also the d-alanylation of LTA, we also investigated whether a reduction of the d-alanyl substitution level of LTA could stimulate autolysis. A dltD mutant of L. lactis was examined with respect to lysis behavior, since a mutation in the dlt operon is expected to affect only the d-alanylation of LTA and not the peptidoglycan cross-linking (37).

d-Ala substitution in LTA is strongly reduced in the dltD mutant of L. lactis; a fivefold reduced amount of d-Ala in its LTA compared to levels in the wild-type L. lactis MG1363 is observed (d-Ala to GroP ratio of 5.8% for the dltD mutant compared to d-Ala to GroP ratio of 28.5% for the wild-type strain; N. Kramer et. al., unpublished data). We show here that this strong reduction in d-Ala substitution in LTA results in increased lysis of L. lactis. A slower growth rate of the mutant is also observed. The same phenomena have been observed in B. subtilis (52). A dltD acmA double mutant of L. lactis does not lyse more, and growth is completely restored; the increased lysis and the effect on growth of L. lactis MG1363 (dltD) are, therefore, dependent on the presence of AcmA. LTA lacking d-Ala substitutions is expected to be more negatively charged. Fischer et al. (15) have reported in S. aureus that acidified LTA, due to a lack of d-Ala, has an improved capacity for binding of the S. aureus autolysin. The possibility that the increased lysis of L. lactis (dltD) was the result of increased binding of AcmA to the cell wall was investigated, since autolysins, including Atl of S. aureus and AcmA, are positively charged enzymes. Mutation of dltD in L. lactis, however, did not influence the binding of AcmA; similar amounts of AcmA bound to cells of L. lactis MG1363acmAΔ1 and L. lactis MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1), and the binding was at the same loci in both strains. Also lysis of both strains upon the external addition of AcmA was identical, indicating that the lysis activity of AcmA remained unchanged and is not influenced by d-alanylation of LTA. In a previous study (49) it has been shown that LTA is likely to be involved in hindering of AcmA binding to cells. Since d-Ala in LTA has no effect on AcmA binding, the present study supports the conclusion that d-Ala in LTA is not involved in hindering AcmA binding.

Although the quantity and location of AcmA binding are not affected in L. lactis (dltD), the strain lyses to a higher extent than its parent. The thickness of the cell wall and septum is not affected by the dltD mutation, precluding the possibility that the lysis increase of L. lactis (dltD) is a consequence of a thinner cell wall. On the other hand, a direct correlation between the mutation of AcmA and a thinner septum was observed, indicating that AcmA is important for the development of a normal septum.

The cell wall of L. lactis MG1363 (dltD) does seem to be weaker than that of the wild-type strain. When lysis is induced with Triton X-100, L. lactis MG1363 (dltD) lyses to a greater extent than its parent. Triton X-100-induced lysis of L. lactis MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) and L. lactis MG1363acmAΔ1 is of the same low level. Incubation of stationary phase cells of L. lactis MG1363acmAΔ1 or L. lactis MG1363 (dltD acmAΔ1) with AcmA does not result in increased lysis of the double mutant, which indicates that AcmA, only when expressed in L. lactis MG1363 (dltD) during growth, results in a weaker cell wall.

d-Alanylation of LTA has been shown previously to be an important factor in the stability of secreted proteins. A dlt mutant of B. subtilis showed an increase in the rate of posttranslational folding of exported proteins, especially those proteins that are susceptible to proteolytic degradation (27). In the absence of d-alanylation, the yield of secreted recombinant anthrax protective antigen was increased 2.5-fold (50). The protease that is involved in this phenomenon has not been identified. Here we show that in L. lactis a mutation in the dltD gene also stabilizes a secreted protein, i.e., AcmA. Zymographic analysis of AcmA activity in supernatants of L. lactis MG1363 and its dltD mutant revealed that the HtrA-mediated breakdown of AcmA (44), which can be seen in MG1363, is not detectable in the mutant.

L. lactis HtrA cleaves AcmA in the C-terminal peptidoglycan-binding domain (8, 44). The AcmA breakdown products are still active (Fig. 6) but will bind less strongly to the lactococcal cell wall, and, as a consequence, they have a lower lytic ability (A. Steen et al., unpublished data, and reference 8). HtrA degradation of AcmA could be a way for the cell to modulate the activity of this potentially lethal enzyme. This control mechanism on AcmA activity is absent in L. lactis (dltD) and could result in the weakening of the peptidoglycan sacculus by the hydrolytic action of AcmA, resulting in increased lysis.

The mutation in dltD could influence the stability of AcmA in two ways. First, HtrA activity could be decreased by the altered physicochemical properties of the cell wall. Second, since folded proteins are expected to be less prone to degradation by HtrA, the folding of AcmA could be faster, due to the proposed increase of cation concentration in the cell envelope (26), a factor known to influence the folding rate of secreted proteins (27, 50). The exact mechanism in the case of AcmA is unknown.

Interestingly, B. subtilis expresses autolysins which contain peptidoglycan binding domains homologous to that of AcmA (33, 34), as well as homologues of HtrA (39, 40). It would be interesting to investigate the role of HtrA in the stability of autolysins and other secreted proteins in dlt mutants of B. subtilis, as it is known that mutation in the dlt operon increases cell lysis in B. subtilis (52).

In conclusion, whereas in the dltD mutant the increased lysis is caused by an effect of reduced d-alanylation levels of LTA on HtrA activity, cell lysis of the alr mutant of L. lactis is likely a combined effect of a defective peptidoglycan synthesis and a reduced d-alanylation level of LTA (Fig. 7). Since a dltD acmA double mutant of L. lactis does not lyse, d-alanylation of LTA only affects cell lysis when AcmA is expressed; d-alanylation of LTA is therefore not involved in the observed lysis of the alr acmA double mutant. The lysis of this double mutant is most likely caused by the defective peptidoglycan synthesis, which makes the cell wall more sensitive to other factors, including, e.g., one or more of the (putative) cell wall hydrolases other than AcmA.

FIG. 7.

Schematic representation of the main conclusions of this paper. (A) In L. lactis MG1363 (and, for that matter, L. lactis NZ3900) AcmA hydrolyses peptidoglycan, resulting in cell lysis and subsequent protein release. AcmA is degraded by HtrA in the C-terminal domain which contains the LysM motifs (small black ovals). AcmA degradation results in a less active enzyme. (B) Since no AcmA is present in the acmA mutant of L. lactis MG1363, no lysis and protein release are observed for this strain. (C) In the dltD mutant of L. lactis, the reduction of d-alanylation of LTA results in a strong reduction of degradation of AcmA by HtrA. As a result, increased cellular lysis and protein release are observed. When AcmA is deleted in this dltD mutant, no lysis is observed (not shown in this figure, but compare with panel B). (D) An alr acmA double mutant, however, lyses, although AcmA is not present in this strain. The lysis of this strain is caused by an unknown factor. The high cellular lysis of the alr single mutant is most likely a combination of the reduced degradation of AcmA by HtrA, as shown in panel C and the AcmA-independent lysis as shown in panel D. A, AcmA; H, HtrA.

Acknowledgments

This research has been carried out with financial support from the Commission of the European Communities, specific RTD projects LABVAC (BIO4-CT96-0542), LABDEL (QLK3-2000-00340) and FAIR (CT98-4396). The content of this article does not necessarily reflect the Commission's views and in no way anticipates the its future policy in this area.

E.P. holds a doctoral fellowship from FRIA. P.H. holds a scientific collaborator fellowship from FNRS.

We are grateful to K. Schanck for skillful help in the construction and characterization of the stable alr mutant. We thank E. Maguin for providing strain MG1362 (dltD) and P. Renault for sequence information on the alr gene from L. lactis IL1403 preceding publication. We thank Naomi Kramer, Siegfried Morath, Thomas Hartung, Eddy J. Smid, Eefjan Breukink, Jan Kok, and Oscar P. Kuipers for sharing the results on the d-Ala determination prior to publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Archibald, A. R., and J. Baddiley. 1966. The teichoic acids. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 21:323-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archibald, A. R., J. Baddiley, and S. Heptinstall. 1973. The alanine ester content and magnesium binding capacity of walls of Staphylococcus aureus H grown at different pH values. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 291:629-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beliveau, C., C. Potvin, J. Trudel, A. Asselin, and G. Bellemare. 1991. Cloning, sequencing, and expression in Escherichia coli of a Streptococcus faecalis autolysin. J. Bacteriol. 173:5619-5623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berberich, R., M. Kaback, and E. Freese. 1968. d-amino acids as inducers of l-alanine dehydrogenase in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 243:1006-1011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bierbaum, G., and H. G. Sahl. 1985. Induction of autolysis of staphylococci by the basic peptide antibiotics Pep 5 and nisin and their influence on the activity of autolytic enzymes. Arch. Microbiol. 141:249-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolotin, A., P. Wincker, S. Mauger, O. Jaillon, K. Malarme, J. Weissenbach, S. D. Ehrlich, and A. Sorokin. 2001. The complete genome sequence of the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis IL1403. Genome Res. 11:731-753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bron, P. A., M. G. Benchimol, J. Lambert, E. Palumbo, M. Deghorain, J. Delcour, W. M. de Vos, M. Kleerebezem, and P. Hols. 2002. Use of the alr gene as a food-grade selection marker in lactic acid bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5663-5670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buist, G. 1997. Ph.D. thesis. University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

- 9.Buist, G., J. Kok, K. J. Leenhouts, M. Dabrowska, G. Venema, and A. J. Haandrikman. 1995. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding the major peptidoglycan hydrolase of Lactococcus lactis, a muramidase needed for cell separation. J. Bacteriol. 177:1554-1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buist, G., G. Venema, and J. Kok. 1998. Autolysis of Lactococcus lactis is influenced by proteolysis. J. Bacteriol. 180:5947-5953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Debabov, D. V., M. Y. Kiriukhin, and F. C. Neuhaus. 2000. Biosynthesis of lipoteichoic acid in Lactobacillus rhamnosus: role of DltD in d-alanylation. J. Bacteriol. 182:2855-2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Ruyter, P. G., O. P. Kuipers, M. M. Beerthuyzen, I. Alen-Boerrigter, and W. M. de Vos. 1996. Functional analysis of promoters in the nisin gene cluster of Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 178:3434-3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duwat, P., A. Cochu, S. D. Ehrlich, and A. Gruss. 1997. Characterization of Lactococcus lactis UV-sensitive mutants obtained by ISS1 transposition. J. Bacteriol. 179:4473-4479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrari, E., J. Henner, and M. Yang. 1985. Isolation of an alanine racemase gene from Bacillus subtilis and its use for plasmid maintenance in B. subtilis. Bio/Technology 3:1003-1007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer, W., P. Rosel, and H. U. Koch. 1981. Effect of alanine ester substitution and other structural features of lipoteichoic acids on their inhibitory activity against autolysins of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 146:467-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gasson, M. J. 1983. Plasmid complements of Streptococcus lactis NCDO 712 and other lactic streptococci after protoplast-induced curing. J. Bacteriol. 154:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grangette, C., H. Muller-Alouf, P. Hols, D. Goudercourt, J. Delcour, M. Turneer, and A. Mercenier. 2004. Enhanced mucosal delivery of antigen with cell wall mutants of lactic acid bacteria. Infect. Immun. 72:2731-2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutberlet, T., J. Frank, H. Bradaczek, and W. Fischer. 1997. Effect of lipoteichoic acid on thermotropic membrane properties. J. Bacteriol. 179:2879-2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammes, W., K. H. Schleifer, and O. Kandler. 1973. Mode of action of glycine on the biosynthesis of peptidoglycan. J. Bacteriol. 116:1029-1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heaton, M. P., R. B. Johnston, and T. L. Thompson. 1988. Controlled lysis of bacterial cells utilizing mutants with defective synthesis of d-alanine. Can. J. Microbiol. 34:256-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heptinstall, S., A. R. Archibald, and J. Baddiley. 1970. Teichoic acids and membrane function in bacteria. Nature 225:519-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hols, P., C. Defrenne, T. Ferain, S. Derzelle, B. Delplace, and J. Delcour. 1997. The alanine racemase gene is essential for growth of Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Bacteriol. 179:3804-3807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hols, P., M. Kleerebezem, A. N. Schanck, T. Ferain, J. Hugenholtz, J. Delcour, and W. M. de Vos. 1999. Conversion of Lactococcus lactis from homolactic to homoalanine fermentation through metabolic engineering. Nat. Biotechnol. 17:588-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huard, C., G. Miranda, Y. Redko, F. Wessner, S. J. Foster, and M. P. Chapot-Chartier. 2004. Analysis of the peptidoglycan hydrolase complement of Lactococcus lactis: identification of a third N-acetylglucosaminidase, AcmC. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3493-3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huard, C., G. Miranda, F. Wessner, A. Bolotin, J. Hansen, S. J. Foster, and M. P. Chapot-Chartier. 2003. Characterization of AcmB, an N-acetylglucosaminidase autolysin from Lactococcus lactis. Microbiology 149:695-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes, A. H., I. C. Hancock, and J. Baddiley. 1973. The function of teichoic acids in cation control in bacterial membranes. Biochem. J. 132:83-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyyrylainen, H. L., M. Vitikainen, J. Thwaite, H. Wu, M. Sarvas, C. R. Harwood, V. P. Kontinen, and K. Stephenson. 2000. d-Alanine substitution of teichoic acids as a modulator of protein folding and stability at the cytoplasmic membrane/cell wall interface of Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 275:26696-26703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiriukhin, M. Y., and F. C. Neuhaus. 2001. d-Alanylation of lipoteichoic acid: role of the d-alanyl carrier protein in acylation. J. Bacteriol. 183:2051-2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuipers, O. P., M. M. Beerthuyzen, R. J. Siezen, and W. M. de Vos. 1993. Characterization of the nisin gene cluster nisABTCIPR of Lactococcus lactis. Requirement of expression of the nisA and nisI genes for development of immunity. Eur. J. Biochem. 216:281-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuipers, O. P., P. G. G. A. de Ruyter, M. Kleerebezem, and W. M. de Vos. 1998. Quorum sensing-controlled gene expression in lactic acid bacteria. J. Biotechnol. 64:15-21. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lambert, P. A., I. C. Hancock, and J. Baddiley. 1975. Influence of alanyl ester residues on the binding of magnesium ions to teichoic acids. Biochem. J. 151:671-676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leenhouts, K. J., and G. Venema. 1992. Molecular cloning and expression in Lactococcus. Meded. Fac. Landbouwwet. Univ. Gent. 57:2031-2043. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Margot, P., M. Pagni, and D. Karamata. 1999. Bacillus subtilis 168 gene lytF encodes a gamma-d-glutamate-meso-diaminopimelate muropeptidase expressed by the alternative vegetative sigma factor, sigmaD. Microbiology 145:57-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Margot, P., M. Wahlen, A. Gholamhoseinian, P. Piggot, and D. Karamata. 1998. The lytE gene of Bacillus subtilis 168 encodes a cell wall hydrolase. J. Bacteriol. 180:749-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mou, L., J. J. Sullivan, and G. R. Jago. 1976. Autolysis of Streptococcus cremoris. J. Dairy Sci. 43:275-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakao, A., S. Imai, and T. Takano. 2000. Transposon-mediated insertional mutagenesis of the d-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid (dlt) operon raises methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Res. Microbiol. 151:823-829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neuhaus, F. C., and J. Baddiley. 2003. A continuum of anionic charge: structures and functions of d-alanyl-teichoic acids in gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:686-723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neuhaus, F. C., M. P. Heaton, D. V. Debabov, and Q. Zhang. 1996. The dlt operon in the biosynthesis of d-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid in Lactobacillus casei. Microb. Drug Resist. 2:77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noone, D., A. Howell, R. Collery, and K. M. Devine. 2001. YkdA and YvtA, HtrA-like serine proteases in Bacillus subtilis, engage in negative autoregulation and reciprocal cross-regulation of ykdA and yvtA gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 183:654-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noone, D., A. Howell, and K. M. Devine. 2000. Expression of ykdA, encoding a Bacillus subtilis homologue of HtrA, is heat shock inducible and negatively autoregulated. J. Bacteriol. 182:1592-1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nouaille, S., J. Commissaire, J. J. Gratadoux, P. Ravn, A. Bolotin, A. Gruss, Y. Le Loir, and P. Langella. 2004. Influence of lipoteichoic acid d-alanylation on protein secretion in Lactococcus lactis as revealed by random mutagenesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1600-1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ou, L. T., and R. E. Marquis. 1970. Electromechanical interactions in cell walls of gram-positive cocci. J. Bacteriol. 101:92-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palumbo, E., C. F. Favier, M. Deghorain, P. S. Cocconcelli, C. Grangette, A. Mercenier, E. E. Vaughan, and P. Hols. 2004. Knockout of the alanine racemase gene in Lactobacillus plantarum results in septation defects and cell wall perforation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 233:131-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poquet, I., V. Saint, E. Seznec, N. Simoes, A. Bolotin, and A. Gruss. 2000. HtrA is the unique surface housekeeping protease in Lactococcus lactis and is required for natural protein processing. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1042-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramasamy, R., S. Yasawardena, R. Kanagaratnam, E. Buratti, F. E. Baralle, and M. S. Ramasamy. 1999. Antibodies to a merozoite surface protein promote multiple invasion of red blood cells by malaria parasites. Parasite Immunol. 21:397-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raychaudhuri, D., and A. N. Chatterjee. 1985. Use of resistant mutants to study the interaction of Triton X-100 with Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 164:1337-1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 48.Seegers, J. F., S. Bron, C. M. Franke, G. Venema, and R. Kiewiet. 1994. The majority of lactococcal plasmids carry a highly related replicon. Microbiology 140:1291-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steen, A., G. Buist, K. J. Leenhouts, M. E. Khattabi, F. Grijpstra, A. L. Zomer, G. Venema, O. P. Kuipers, and J. Kok. 2003. Cell wall attachment of a widely distributed peptidoglycan binding domain is hindered by cell wall constituents. J. Biol. Chem. 278:23874-23881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thwaite, J. E., L. W. Baillie, N. M. Carter, K. Stephenson, M. Rees, C. R. Harwood, and P. T. Emmerson. 2002. Optimization of the cell wall microenvironment allows increased production of recombinant Bacillus anthracis protective antigen from B. subtilis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:227-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wecke, J., M. Perego, and W. Fischer. 1996. d-Alanine deprivation of Bacillus subtilis teichoic acids is without effect on cell growth and morphology but affects the autolytic activity. Microb. Drug Resist. 2:123-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wood, W. A., and I. C. Gunsalus. 1951. d-Alanine formation: a racemase in Streptococcus faecalis. J. Biol. Chem. 190:403-416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zabarovsky, E. R., and G. Winberg. 1990. High efficiency electroporation of ligated DNA into bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:5912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]