Abstract

The type II secretion system is a macromolecular assembly that facilitates the extracellular translocation of folded proteins in gram-negative bacteria. EpsE, a member of this secretion system in Vibrio cholerae, contains a nucleotide-binding motif composed of Walker A and B boxes that are thought to participate in binding and hydrolysis of ATP and displays structural homology to other transport ATPases. Here we demonstrate that purified EpsE is an Mg2+-dependent ATPase and define optimal conditions for the hydrolysis reaction. EpsE displays concentration-dependent activity, which may suggest that the active form is oligomeric. Size exclusion chromatography showed that the majority of purified EpsE is monomeric; however, detailed analyses of specific activities obtained following gel filtration revealed the presence of a small population of active oligomers. We further report that EpsE binds zinc through a tetracysteine motif near its carboxyl terminus, yet metal displacement assays suggest that zinc is not required for catalysis. Previous studies describing interactions between EpsE and other components of the type II secretion pathway together with these data further support the hypothesis that EpsE functions to couple energy to the type II apparatus, thus enabling secretion.

Vibrio cholerae infection of the small intestine results in severe diarrheal disease, with the main virulence factor, cholera toxin, causing many of the disease symptoms. Extracellular secretion of cholera toxin occurs via two distinct steps: inner membrane translocation of the individual toxin subunits via a Sec-dependent mechanism and outer membrane translocation of the assembled toxin complex by the type II secretion pathway. The type II pathway is conserved among gram-negative bacteria, including many pathogens, and secretes a variety of virulence factors and degradative enzymes. The type II pathway components in V. cholerae are encoded by 12 eps (extracellular protein secretion) genes, organized in a single operon, and the vcpD/pilD gene (7, 17, 29).

The components of the Eps transport system are found in association with both inner and outer membranes and assemble into a multiprotein apparatus that most likely spans the entire cell envelope (for a review, see reference 27). A fully functional transport system requires the presence of EpsE, which is a cytoplasmic protein when it is expressed in the absence of other Eps proteins but is associated with the cytoplasmic membrane in the presence of the inner membrane proteins EpsL and EpsM (28).

EpsE is a member of a larger family of secretion nucleoside triphosphatases (NTPases; the type II/type IV secretion family), which are thought to couple nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) hydrolysis to bacterial protein secretion (19). Members of this secretion NTPase family contain the following conserved motifs; Walker A and B boxes, a histidine box, and an aspartate box (20, 24, 25, 35). Several members of the type IV secretion ATPase family, such as HP0525 from Helicobacter pylori, TrbB from the conjugative transfer apparatus of plasmid RP4 (13, 14, 31), DotB from the Dot/Icm apparatus in Legionella pneumophila (32), and the type IV pilus retraction ATPase PilT (6, 9, 18), have been characterized as hexameric ATPases. The structure of a truncated form of EpsE [Δ90EpsE(His)6] was recently solved (25). The closest structural homolog for this two-domain protein was the type IV secretion ATPase HP0525, despite the relatively low sequence homology (30% identity over 100 amino acid residues). The truncated EpsE variant crystallized as a helical filament; however, a hexameric ring model for EpsE was proposed by modeling it onto the HP0525 hexamer, since 8 of the 10 closest structural homologues assemble into multisubunit rings. Nevertheless, the oligomeric state of EpsE within the intact Eps secretion apparatus is unknown. The structural analysis of EpsE also verified the presence of a metal-binding domain that uses a tetracysteine motif to coordinate a divalent metal (25). The tetracysteine motif in EpsE is composed of two Cys-X-X-Cys boxes separated by 29 residues and is for the most part conserved among members of the type II family of putative NTPases but absent in the type IV ATPases. Replacement of the cysteines in the EpsE homolog PulE abolishes secretion of pullulanase (21), suggesting that they play an important role in the secretion process.

Although EpsE is structurally homologous to HP0525 and other ATPases, no ATPase activity has thus far been demonstrated for EpsE; however, the Walker A ATP-binding motif is essential for function, as a lysine-to-alanine substitution in this motif results in a mutant form of EpsE that is unable to support secretion in V. cholerae (28). Furthermore, structural information about this motif revealed that residues within the Walker A box form an extensive network of hydrogen bonds with the phosphate tail of the ATP analog AMPPNP (25). To continue the molecular analysis of this important type II secretion component, we have expressed and purified EpsE as a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein. We have demonstrated that EpsE is an Mg2+-dependent ATPase and have characterized its activity by identifying optimal conditions for hydrolysis. We also report that EpsE can form oligomers that are more active than the monomer. Additionally, metal analysis of EpsE indicated the presence of a zinc cation that is coordinated by a conserved tetracysteine motif.

(This work was performed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Ph.D. degree in biochemistry for J.L.C. from the George Washington University Institute for Biomedical Sciences, George Washington University, Washington, D.C.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning.

V. cholerae epsE was amplified from plasmid pMMB349 (30) by PCR and cloned as a BamHI/SmaI fragment into the multiple cloning site of plasmid pGEX-4T-2 (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.), which contained the coding sequences for GST and a thrombin cleavage site. The resulting plasmid, pGST-EpsE, was transformed into Escherichia coli TG1 cells. To create pGST-EpsE(K270A), the internal MfeI/XbaI fragment of epsE in pGST-EpsE was replaced with that of pMS26, which carried the mutation.

Expression and Purification of EpsE.

Fifteen milliliters of an overnight culture of E. coli TG1 cells containing pGST-EpsE was used to inoculate 0.75 liter of Luria-Bertani medium containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and grown at 37°C. When an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 was reached, 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added, the temperature was reduced to 28°C, and the cells were grown for an additional 3 h, harvested by centrifugation, and stored at −80°C. A 10× cell extract was made by French press lysis in buffer A [100 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 0.5 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine hydrochloride] containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (1 tablet/100 ml of lysate; Roche, Mannheim, Germany), and DNase I (5 U/ml of lysate) (M. Robien and W. Hol, personal communication). Lysate supernatants, obtained by centrifugation at 27,000×g for 30 min at 4°C, were bound to glutathione Sepharose (1.33 ml of resin/100 ml of lysate; Amersham Pharmacia) by the batch method at 4°C for 2 h and washed with 85 bed volumes of buffer A. EpsE was eluted by 16 h of incubation (22°C, rotating) with bovine thrombin (100 U/ml of resin; Amersham Pharmacia) in buffer A (2 bed volumes). Eluted EpsE was applied to a benzamidine Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia) column to remove thrombin, and eluent was collected. Fractions were monitored by reducing sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE; final sample concentration, 50 mM dithiothreitol) on a 4 to 12% Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gel in morpholineethanesulfonic acid (MES) running buffer with the NuPAGE system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). Gels were stained with GelCode Blue (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, Ill.). Protein concentration was determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay dye-binding reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). The final concentrations ranged from 0.8 to 1.5 mg/ml, depending on the preparation. This procedure was also used for the purification of EpsE(K270A).

ATPase activity assays.

ATPase activity was determined with a procedure modified from the malachite green assay (8) to monitor the release of inorganic phosphate (Pi). For time course analyses, reaction mixtures containing EpsE or EpsE(K270A) (1 μM), 4 mM ATP, and 4 mM MgCl2 were incubated at 37°C in 100 mM Tris (pH 8.5). Every 45 min, 30 μl from each reaction mixture was assayed for Pi in duplicate. Bovine serum albumin (1 μM) served as a negative control. Color reagent (200 μl containing 0.034% malachite green hydrochloride, 1 N hydrochloric acid, 1.05% ammonium molybdate, and 0.1% Triton X-100) was added to an assay volume of 30 μl. After 2 min, 25 μl of 34% sodium citrate was added and the reaction mixtures were incubated for 25 min. Absorbance was measured at 650 nm. The total Pi for each reaction was compared with a Pi standard curve. For endpoint assays, 130 μl of each ATPase reaction mixture containing 0.625 μM EpsE was subjected to similar conditions and assayed at 0 and 210 min in duplicate.

For enzymatic characterization studies, the following conditions were modified: ATP concentration, NaCl concentration, temperature, pH by buffer composition (100 mM MES [pH 6.5], HEPES [pH 7.0 to 7.5], Tris [pH 8.0 to 9.0], and 3-cyclohexylamino-1-propanesulfonic acid [CAPS, pH 9.5]), NTP (GTP, UTP, CTP, TTP, and dATP), divalent metal cation (4 mM CaCl2, 4 mM MnCl2, and 4 mM EDTA), and EpsE concentration. All errors are reported as standard errors.

Analytical gel filtration.

Purified EpsE (700 μg) was concentrated to 2 mg/ml in 100 mM Tris (pH 8.5)-65 mM NaCl-0.5% glycerol-1 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine hydrochloride by centrifugation with a Microcon filter (30-kDa cutoff; Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). The sample was then run on a Superose 6 HR 10/30 column (Amersham Pharmacia) equilibrated with 100 mM Tris (pH 8.5)-65 mM NaCl-0.5% glycerol at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Fractions (0.5 ml) were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining (Invitrogen). Each fraction was examined for ATP hydrolysis by a malachite green endpoint assay; Pi was measured after incubation at 37°C for 1,000 min of a reaction mixture containing 130 μl of the fraction, 4 mM MgCl2, and 4 mM ATP. Assay points were measured in duplicate. The protein concentration of each fraction was determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent in duplicate reaction mixtures with a minimum detection limit of 1.25 μg/ml. Specific activity was calculated for fractions demonstrating peak Pi generation. In the case of the monomer, EpsE was pooled and assayed for concentration and activity independently.

For analysis on the Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (Amersham Pharmacia), 700 μg of EpsE at 3 mg/ml was applied to the column and run at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Fractions (0.5 ml) were collected and analyzed as already described. For removal of residual GST-tagged material, EpsE in buffer A was incubated with glutathione Sepharose (200 μl of Sepharose per mg of protein) for 2 h at 4°C. The resulting eluent containing EpsE (640 μg) was concentrated to 2 mg/ml and applied to a Superose 6 column. Fractions were collected and examined as already described. Differences in the total amount of protein concentrated and applied to each column varied by ≤10%. Markers used for gel filtration analyses included blue dextran (2 MDa), thyroglobulin (669 kDa), ferritin (440 kDa), catalase (240 kDa), bovine serum albumin (67 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), and cytochrome C (13.6 kDa).

Detection and identification of EpsE metal coordination.

Removal of the divalent heavy metal from EpsE was performed by titration with p-hydroxymercuriphenylsulfonic acid (PMPS; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and detection with 4-(2-pyridylazo)resorcinol (PAR; Sigma) as previously described (10). Briefly, increasing quantities of PMPS (0 to 75 μM) were added to 10 μM EpsE in 100 mM Tris-65 mM NaCl-0.5% glycerol (pH 8.5), in the presence of 200 μM PAR. The absorbance of PAR was monitored at 500 nm after 3 min and compared to a standard curve prepared with ZnCl2. For enzymatic activity analysis, metal-free EpsE was produced by metal displacement with PMPS with the same molar ratio and procedure as already described. Metal-free EpsE (1 μM) was analyzed for the liberation of Pi after 3 h in an endpoint assay. A reaction mixture containing PMPS alone was used as a control to ensure that PMPS did not affect the Pi measurement. These data were compared with the rate of ATP hydrolysis by metal-containing EpsE.

Identification of the divalent metal was performed by inductively coupled argon plasma 20-element trace metal analysis. Briefly, 1 mg of EpsE was treated with Chelex-100 (Sigma) and analyzed for metal content. As a control, Chelex-treated EpsE was removed from buffer via centrifugation in a Microcon filter (10-kDa cutoff), and the eluent was analyzed for metal content.

RESULTS

EpsE has ATPase activity.

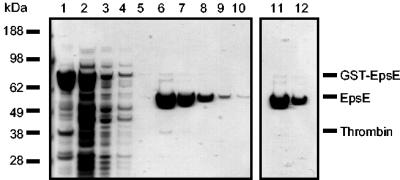

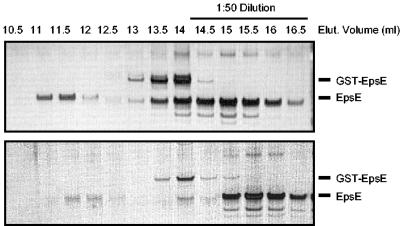

EpsE was expressed in E. coli as a GST fusion protein with a thrombin cleavage site and purified on a glutathione Sepharose column from the soluble cell extract. EpsE was eluted from the column by addition of thrombin. N-terminal sequence analysis of the eluted EpsE confirmed the replacement of the wild-type initiator methionine with glycine-serine, a product of thrombin cleavage. Purity of the final product after thrombin removal was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Purification of EpsE. GST-EpsE was affinity purified from soluble E. coli extract with glutathione Sepharose. EpsE was cleaved from GST by the addition of thrombin (100 U/ml). Purified material was passed over benzamidine Sepharose for removal of thrombin. Fractions were analyzed by reducing SDS-PAGE and stained with GelCode blue. Lanes: 1, insoluble pellet obtained after French press and centrifugation; 2, soluble extract used for purification; 3, column flowthrough; 4 and 5, buffer washes; 6 to 10, fractions obtained by elution with thrombin; 11 and 12, fractions recovered after thrombin removal.

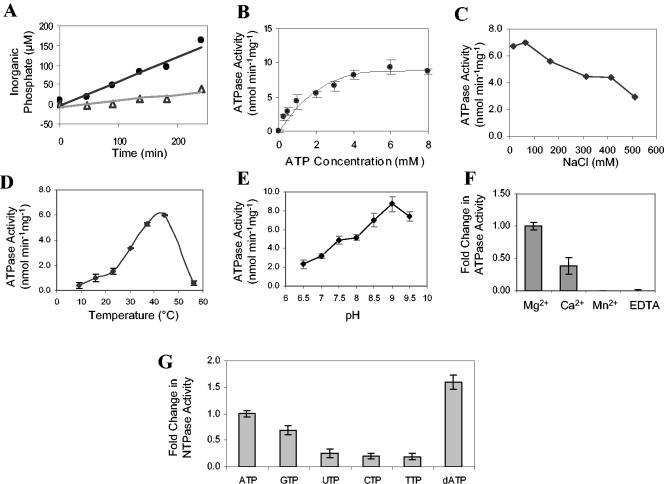

EpsE was tested for the ability to hydrolyze ATP by the malachite green assay. Analysis of a mutant form of EpsE that has the conserved lysine replaced with alanine in the Walker A motif, EpsE(K270A), expressed and purified in parallel with native EpsE, revealed that modification of the ATP-binding site lowered the specific activity of EpsE approximately threefold (Fig. 2A). Rates of ATP hydrolysis were calculated to be 5.6 and 1.5 nmol min−1 mg−1 for EpsE and EpsE(K270A), respectively. The rate of ATP hydrolysis observed for EpsE is similar to rates observed for other type II/type IV secretion family members, including PilQ, PilT, DotB, and TrwD (9, 24, 26, 32).

FIG. 2.

ATPase activity of EpsE under various conditions. (A) Time course analysis of ATP hydrolysis. EpsE and EpsE(K270A) were purified in parallel and tested for ATPase activity by incubation with 4 mM ATP and 4 mM MgCl2 at 37°C (1 μM final protein concentration). Total Pi was measured at intervals by the malachite green assay. EpsE, closed symbols; EpsE(K270A), open symbols. (B) Concentration of substrate required for enzyme saturation. We tested 0.625 μM EpsE in 100 mM Tris (pH 8.5) for ATPase activity by the addition of increasing amounts of substrate (0 to 8 mM ATP) with an endpoint assay (n = 3 for each substrate concentration). Error is reported as the standard error. (C) ATPase activity for EpsE tested at various NaCl concentrations with an endpoint assay. (D) ATPase activity determination at different temperatures (n = 3). (E) Influence of pH on EpsE ATPase activity (n = 7). (F) Optimal divalent metal to support ATPase activity. The final concentration of divalent metal was 4 mM. Mg2+, n = 14; Ca2+, Mn2+, and EDTA, n = 8. (G) Optimal substrate for hydrolysis. NTPs were added to a final concentration of 4 mM. ATP, GTP, TTP, and dATP, n = 12; CTP, n = 11; UTP, n = 8.

Next, the conditions for optimal ATPase activity were determined. By varying the ATP concentration, we determined that maximal hydrolysis occurred at 4 mM ATP (Fig. 2B). Reducing the NaCl concentration in the ATPase assay from the 500 mM used throughout purification to 65 mM had a significant effect of the rate of hydrolysis (Fig. 2C), with optimal activity occurring under low-salt conditions. EpsE was most active in the range of 37 to 44°C (Fig. 2D) and at a pH between 8.5 and 9.5 (Fig. 2E). Although manganese can often substitute for magnesium in Mg2+-dependent ATPases, as in PilT, for example (9), at 4 mM neither Mn2+ nor Ca2+ was able to significantly contribute to the enzymatic activity (Fig. 2F). To test whether EpsE is strictly able to hydrolyze ATP, we measured the generation of Pi in the presence of different NTPs (Fig. 2G). At 4 mM NTP, EpsE was able to efficiently hydrolyze ATP and dATP, while hydrolysis of other NTPs was reduced.

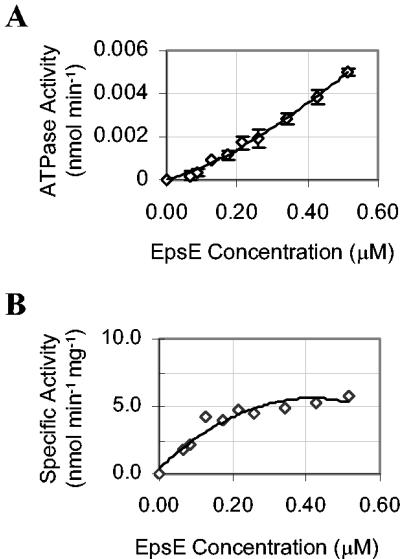

EpsE displays cooperative activity.

To establish whether the concentration of EpsE influences its specific activity, we examined ATP hydrolysis at different enzyme concentrations under saturating substrate conditions (5 mM ATP). If enzyme concentration does not affect activity, then a plot of ATP hydrolysis versus enzyme concentration should demonstrate a linear relationship; however, the plot of ATP hydrolysis versus enzyme concentration (Fig. 3A) for EpsE revealed a concave mode of behavior, indicating that the activity is concentration dependent. At low enzyme concentrations, the specific activity of EpsE was not maximal under saturating substrate conditions (illustrated in Fig. 3B). As the enzyme concentration increased, so did the specific activity until the maximal enzyme activation was reached near 6 nmol min−1 mg−1. The enzyme concentration at half-maximal activation, was found to be 110 nM EpsE. Concentration-dependent activity may indicate cooperative association of EpsE subunits. This behavior has been identified for a number of NTPases that have subsequently been functionally characterized as oligomers (2, 12, 22, 33).

FIG. 3.

Concentration-dependent activity of EpsE. (A) ATP hydrolysis was monitored with an endpoint assay at various EpsE concentrations (0.06 to 0.5 μM) with 5 mM MgCl2 and 5 mM ATP at 37°C. Total Pi was measured after 16 h (n = 3 for each enzyme concentration). (B) Concentration-dependent ATP hydrolysis was analyzed on a plot of specific activity (nmol min−1 mg−1) versus EpsE concentration (micromolar).

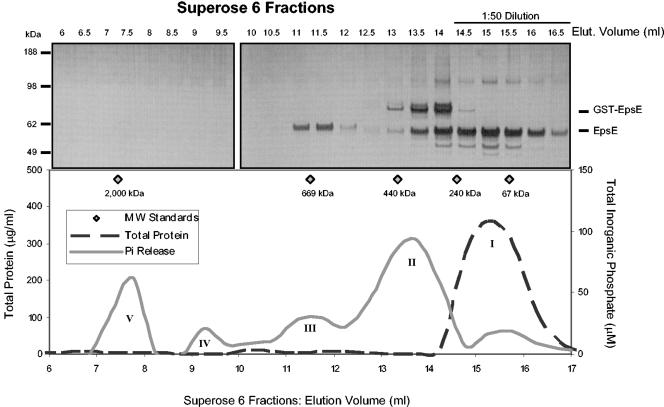

Purified EpsE contains oligomers with increased specific activity.

The concentration-dependent behavior demonstrated by EpsE suggested that it may function as an oligomer. To test this possibility and to identify the oligomerization state of EpsE, gel filtration analysis was performed. Purified EpsE was fractionated on a Superose 6 column, and the fractions were examined for total protein content and enzymatic activity (Fig. 4). Total protein determination of the gel filtration fractions revealed that the predominant form was monomeric (peak I, >93%), as has previously been described for EpsE(His)6 (28). By monitoring the production of Pi from ATP, however, we identified four additional peaks of activity along the gradient. These peaks, II through V, were broad and may correspond to hexameric assemblies. The protein content in peak fractions contained within peaks II through V fractionated according to the following molecular masses: 360 kDa (13.5 ml), 640 kDa (11.5 ml), 1,200 kDa (9.25 ml), and 1,850 kDa (7.75 ml), respectively. On the basis of the migration of protein size markers, we would expect an EpsE hexamer with a predicted molecular mass of 338 kDa to peak around 13.7 ml, which corresponds closely to our observed peak II. Elution of the peak II as a hexamer was also supported by analysis of a Superdex 200 column, which showed a Pi generation peak corresponding to 307 kDa, or 5.5 EpsE subunits. The position of peak III along the elution is consistent with an EpsE dodecamer. The protein contained within peaks IV and V was not apparent by SDS-PAGE, but the peaks were associated with activity. Peaks IV and V appeared to contain larger disulfide-bonded oligomers or aggregates of EpsE, since EpsE was visualized when samples from these peaks were reduced with dithiothreitol prior to SDS-PAGE (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Size exclusion chromatography reveals oligomeric forms of EpsE. EpsE was fractionated on a Superose 6 column. Fractions of 0.5 ml were collected and assayed for total protein and ATP hydrolysis. The upper panel shows SDS-PAGE analysis and silver staining of individual fractions. The lower panel shows protein concentration (dashed line) and Pi production (solid line) per fraction elucidating five distinct peaks (I to V). MW, molecular mass; Elut., elution.

It is obvious from Fig. 4 that much higher specific activity is associated with the oligomeric peaks (II through V) than with monomeric peak I. This is based on the fact that there is very little protein in the oligomeric fractions, yielding the majority of Pi; the opposite is true for the monomer. The protein concentrations obtained from the oligomeric fractions were near the limits of detection, making a precise estimate of specific activity difficult. Nevertheless, the specific activities of individual peak fractions were calculated and are listed in Table 1 along with molecular sizes and protein concentration. Peak II displayed the highest specific activity (61.0 nmol min−1 mg−1), 100-fold more active than the monomer.

TABLE 1.

Size and specific activity of EpsE oligomers

| Peak | Molecular mass (kDa) | Form | Concentration (μg/ml) | ATPase activity (nmol/min/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 60 | 1.0 subunits (monomer) | 33.3 | 0.60 |

| II | 360 | 6.4 subunits (hexamer) | 1.6 | 61.0 |

| III | 640 | 11.5 subunits (dodecamer) | 7.7 | 3.8 |

SDS-PAGE analysis of the Superose 6 fractions corresponding to peak II showed the presence of both GST-EpsE and EpsE. Although the total proportion of GST-EpsE in our original preparation was very low (as demonstrated by SDS-PAGE in Fig. 1), GST-EpsE appeared to be enriched in fractions between 13 and 15 ml. The mixed population of EpsE and residual GST-EpsE could be a consequence of inefficient cleavage by thrombin and the subsequent elution of hetero-oligomers from glutathione Sepharose. Additionally, the presence of several populations of hetero-oligomers each with different numbers of GST moieties still attached may explain why peaks II and III were broad (Fig. 4). To test if the oligomers were heterogeneous and contained both EpsE and GST-EpsE, we treated our purified EpsE protein with glutathione Sepharose to remove residual GST-tagged material and observed the Superose 6 elution profile by SDS-PAGE. If the oligomers were heterogeneous, we would expect to see that removal of GST-EpsE by treatment with glutathione Sepharose would result in reduction of native EpsE in the oligomeric fractions as well. Figure 5 illustrates that treatment with glutathione Sepharose resulted in an overall loss of protein in both peaks II (13.0 to 14.0 ml) and III (11.0 to 12.0 ml). Not only was the elution profile of GST-EpsE altered, but the elution profile of EpsE was changed as well. These data suggest that the two forms participate in mixed oligomers. Analysis of peak III prior to treatment with glutathione Sepharose had suggested that the predominant constituent was EpsE; removal of GST-tagged material also resulted in the loss of EpsE in peak III. According to SDS-PAGE, it appears that the ratio of GST-EpsE to EpsE is lower in peak III than in peak II. When we compared the elution profiles according to the generation of Pi for both conditions, we observed no loss in the generation of Pi attributable to peak I upon treatment with glutathione Sepharose but 60 to 70% loss in the generation of Pi that corresponds to both peak II and peak III regions, thus indicating that these hetero-oligomers contribute to the overall activity in the preparation. In a separate experiment to disrupt GST-EpsE, we incubated our purified protein with thrombin and then subjected the material to size exclusion chromatography. Similar to treatment with glutathione Sepharose, thrombin treatment also resulted in a loss of protein and Pi generation in the regions of both peaks II and III (data not shown). It is possible that GST stabilizes the EpsE oligomer and that the EpsE oligomer dissociates or aggregates upon removal of the GST tag.

FIG. 5.

Removal of GST-containing oligomers. EpsE was treated with glutathione Sepharose and applied to a Superose 6 column. Fractions of 0.5 ml were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining (lower panel). These fractions were compared with the elution profile of untreated EpsE (upper panel). Elut., elution.

As previously mentioned, the EpsE preparation was predominantly monomeric but very little activity was associated with these fractions in comparison with the oligomeric forms (Fig. 4). Monomer fractions were pooled and assayed for protein concentration and activity and found to have a specific activity of only 0.60 ± 0.04 nmol/min/mg (n = 3). Attempts to generate active oligomers by concentration of the monomer to 2 mg/ml were unsuccessful, resulting in aggregation of EpsE and no increase in overall specific activity (data not shown).

The mutant EpsE(K270A) fractionated predominantly as a monomer (not shown), just as native EpsE did. The EpsE(K270A) monomer displayed a specific activity of 0.20 ± 0.08 nmol/min/mg (n = 3), threefold less than the native EpsE monomer and consistent with our initial finding that revealed a threefold difference in activity between the unfractionated preparations of wild-type and mutant EpsE variants (Fig. 2A). In a separate experiment in which GST-EpsE and GST-EpsE(K270A) were purified as intact GST fusion proteins, a similar twofold difference in activity was observed (data not shown). In this case the GST fusions were purified as dimers, since GST is capable of dimerization. Taken together, replacement of lysine in the Walker A box results in a two- to threefold reduction in the specific ATPase activity of EpsE.

EpsE is a zinc metalloprotein.

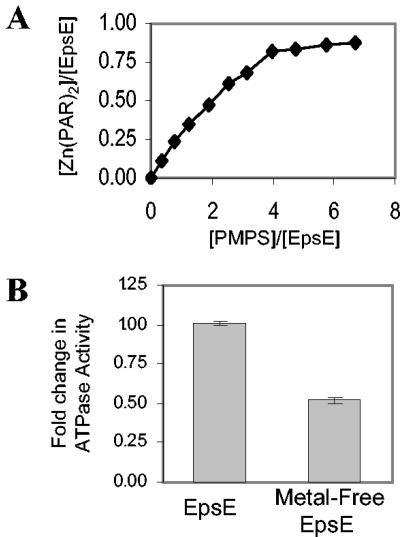

Near its carboxyl terminus, EpsE contains a tetracysteine motif composed of two Cys-X-X-Cys boxes separated by 29 residues (30). These motifs are often present in proteins to tetrahedrally coordinate a divalent heavy metal via cysteine residues (15). For example, studies of a similar motif in thioredoxin has demonstrated that the 4Cys center has a very high affinity for zinc (Ka, >1018 M−1) (3). Crystal structure analysis of truncated histidine-tagged EpsE demonstrated the presence of a tetrahedrally coordinated divalent metal (25), but the site was not fully occupied and the identity of the metal was not resolved. To test whether our active full-length EpsE protein also coordinates a divalent heavy metal, such as zinc, we displaced the metal by addition of PMPS, which binds the sulfhydryl groups of cysteine residues. Free metal was then detected in solution by monitoring the absorption of PAR, a spectrophotometric reagent that binds free divalent heavy metals, shifting its absorption maxima (10). As shown in Fig. 6A, addition of 4 molar equivalents of PMPS resulted in the liberation of 0.81 mol of divalent metal for every 1.0 mol of EpsE. These data suggest that EpsE incorporates a divalent metal through interactions with its four cysteine residues, that the metal is present at an approximate molar ratio of 1:1 with EpsE, and that our purified material is 80% occupied by divalent metal.

FIG. 6.

Depletion of divalent metal from EpsE and enzymatic analysis. (A) Increasing concentrations of PMPS were added to a 10 μM solution of EpsE containing 200 μM PAR. Absorbance of PAR was monitored at 500 nm and compared to a ZnCl2 standard curve to measure the amount of divalent metal complexed with PAR upon PMPS addition. (B) ATPase activity of metal-free EpsE was measured with an endpoint assay and compared with that of untreated EpsE. (n = 3).

Trace metal analysis of Chelex-treated EpsE revealed that 56.4% of purified EpsE was occupied by zinc, 3.1% was occupied by iron, and 1.1% was occupied by copper. The amounts of other metals were too near the limits of detection to be quantified.

Role of tetracysteine-coordinated Zn2+ in ATPase activity.

To determine whether the tetracysteine-coordinated Zn2+ within EpsE participates in ATP hydrolysis, metal-free EpsE was examined in an ATP hydrolysis reaction. To remove zinc, EpsE was incubated with a fourfold molar excess of PMPS and tested for ATP hydrolysis in an endpoint assay. Figure 6B compares the enzymatic activity determined for metal-free EpsE with that of metal-containing EpsE. The addition of PMPS and subsequent removal of zinc reduced the specific activity of EpsE by only 48%. If the zinc were directly involved in enzymatic activity, we would expect that removal would abolish activity. Instead, we observed only a partial reduction, suggesting that the zinc per se is not required for direct catalysis; however, the zinc motif may play an important role in the overall function of this enzyme.

DISCUSSION

This study represents the first report of ATPase activity for EpsE, the cytoplasmic component of the type II secretion system in V. cholerae. We show that EpsE can function as an Mg2+-dependent ATPase with optimal activity occurring under low salt conditions, at pH 8.5 to 9.5, and at 37 to 44°C. Although a high NaCl concentration was used for the purification of soluble EpsE, lower-salt conditions appeared to favor an active state of EpsE. This has also been documented for the protein-activated chaperone ATPase ClpB (11). ClpB forms a heptameric ring whose oligomerization is dependent upon the NaCl concentration and ATP. Increasing salt concentrations (>100 mM) reduce the ATPase activity of ClpB.

Further modification of the ATPase assay is likely to identify conditions that enhance the activity of EpsE. That EpsE-K270A is nonfunctional in vivo while its specific ATPase activity in vitro is only reduced by two- to threefold is consistent with the suggestion that the conditions for optimal ATPase activity have yet to be identified. The addition of other Eps proteins such as EpsL and/or phospholipids may stimulate the low ATPase activity of wild-type EpsE, while the activity of the mutant EpsE protein may remain unaltered, as was demonstrated for the corresponding K120Q mutant form of the partition ATPase SopA (16).

We also demonstrate that EpsE displays concentration-dependent ATPase activity. Taken together with earlier findings from genetic lambda repressor and yeast-two hybrid analyses of the EpsE homologues XcpR and OutE, respectively, our size exclusion chromatography results indicate that the type II secretion ATPases can assemble into oligomers (23, 34). That the functional form of these ATPases is oligomeric in nature is supported by our discovery of a small population of oligomers that displayed much higher specific activity than the monomer. Unfortunately, most of the purified EpsE was monomeric. It is possible that EpsE requires the presence of other Eps components such as EpsL for efficient oligomerization. Our EpsE oligomers appeared to be of a mixed nature, containing both EpsE and GST-EpsE. GST is dimeric and has not been reported to induce hexamerization. The information required for higher-order oligomerization must therefore be contained within EpsE; however, it is possible that GST stabilizes a conformation of EpsE that favors its oligomerization and the oligomerization results in increased activity. That GST stabilizes EpsE in a conformation that is compatible with ATP hydrolysis was further supported by the purification and analysis of the intact GST-EpsE fusion protein. The specific activity of GST-EpsE was found to be higher than that of thrombin-cleaved EpsE (data not shown). The increased ATPase activity was not contributed by GST itself, since GST is incapable of ATP hydrolysis (24).

The functional form of EpsE in vivo is most likely hexameric. This is supported by our identification of an EpsE hexamer with highly elevated ATPase activity and by the previous discovery that Δ90EpsE crystallizes as a helical filament with sixfold symmetry (25). In addition, the closest structural homolog, the type IV secretion ATPase HP0525, assembles into a hexameric ring, as visualized by electron microscopy (31). The presence of dodecamers and possibly even higher multiples of EpsE could be attributed to hexamer stacking or dimerization between GST tags among different hexamers.

Additional biochemical analyses revealed that EpsE incorporates 1 mol of zinc per mol of EpsE via coordination by its four conserved Cys residues. Zinc does not appear to be directly involved in catalysis, since complete removal of zinc reduced the specific activity by less than 50%. That zinc coordination per se is not required for ATP hydrolysis is consistent with the absence of the tetracysteine motif in the two EpsE homologs in Xylella fastidiosa and Xanthomonas campestris. Then again, mutational analysis of the tetracysteine motif in the EpsE homolog PulE of Klebsiella oxytoca indicated that substitution of one or two of the cysteines reduced type II-mediated secretion by 80% while substitutions of three cysteine residues abolished secretion (21). It is possible that zinc coordination is important for folding and/or oligomerization of EpsE and of the other type II secretion ATPases. Alternatively, zinc coordination could allow the region between the two Cys-X-X-Cys motifs to adopt a particular fold to which other Eps proteins bind. One example of a similar motif that facilitates protein-protein interactions occurs in SecA, the cytoplasmic ATPase required for signal peptide-mediated translocation across the cytoplasmic membrane. SecA coordinates zinc via Cys-X-Cys-X9-Cys-His, which appears to participate in SecB binding (5, 36). SecB binding stimulates SecA ATP hydrolysis, and replacement of basic residues within the zinc loop of SecA disrupts its interaction with SecB but not zinc coordination (36). ClpX, of the ATP-dependent protease complex ClpP/ClpX, is another example of an ATPase that contains a zinc-binding tetracysteine motif. In this protein, the zinc loop is suggested to serve a role in mediating ClpX subunit interaction to enable hexamer formation and thus stimulate ATP hydrolysis (1). More specifically, the ClpX hexamer has been described as a trimer of dimers in which the dimers are formed by two interacting zinc-binding domains (4). Examination of the hexameric ring model of EpsE does not appear to indicate a direct role for the region between the cysteine residues in EpsE oligomerization; however, this region does form an elbow on the periphery of the hexamer perpendicular to the central pore (25), a location amenable to participation in interactions with other proteins.

Considering that the EpsE hexamer displays high ATPase activity and that modeling of EpsE as a hexamer generates an internal pore of approximately 14Å (Mark Robien and Wim Hol, personal communication), EpsE may participate, with the inner membrane proteins EpsL and EpsM, in the transport of other Eps components across the cytoplasmic membrane. EpsG and the other pilin-like subunits are possible substrates that could use the EpsE pore for transport and subsequent assembly. Their assembly may lead to the formation of a periplasm-spanning pilus-like structure that supports secretion of cholera toxin through the outer membrane (27). This could occur via a ratchet mechanism driven by repetitive ATP binding and hydrolysis by EpsE, thus supporting the growth of the pilus-like structure in a direction towards the EpsD secretion pore.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI49294, and J.L.C. was supported by National Institutes of Health training grant HL007698.

We thank Kenneth Ingham, Michael Bagdasarian, Jan Abendroth, and the members of the Sandkvist laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banecki, B., A. Wawrzynow, J. Puzewicz, C. Georgopoulos, and M. Zylicz. 2001. Structure-function analysis of the zinc-binding region of the Clpx molecular chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 276:18843-18848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Claret, L., S. R. Calder, M. Higgins, and C. Hughes. 2003. Oligomerization and activation of the FliI ATPase central to bacterial flagellum assembly. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1349-1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collet, J. F., J. C. D'Souza, U. Jakob, and J. C. Bardwell. 2003. Thioredoxin 2, an oxidative stress-induced protein, contains a high affinity zinc binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 278:45325-45332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donaldson, L. W., U. Wojtyra, and W. A. Houry. 2003. Solution structure of the dimeric zinc binding domain of the chaperone ClpX. J. Biol. Chem. 278:48991-48996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fekkes, P., J. G. de Wit, A. Boorsma, R. H. Friesen, and A. J. Driessen. 1999. Zinc stabilizes the SecB binding site of SecA. Biochemistry 38:5111-5116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forest, K. T., K. A. Satyshur, G. A. Worzalla, J. K. Hansen, and T. J. Herdendorf. 2004. The pilus-retraction protein PilT: ultrastructure of the biological assembly. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60:978-982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fullner, K. J., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1999. Genetic characterization of a new type IV-A pilus gene cluster found in both classical and El Tor biotypes of Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 67:1393-1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henkel, R. D., J. L. VandeBerg, and R. A. Walsh. 1988. A microassay for ATPase. Anal. Biochem. 169:312-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herdendorf, T. J., D. R. McCaslin, and K. T. Forest. 2002. Aquifex aeolicus PilT, homologue of a surface motility protein, is a thermostable oligomeric NTPase. J. Bacteriol. 184:6465-6471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt, J. B., S. H. Neece, H. K. Schachman, and A. Ginsburg. 1984. Mercurial-promoted Zn2+ release from Escherichia coli aspartate transcarbamoylase. J. Biol. Chem. 259:14793-14803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim, K. I., G. W. Cheong, S. C. Park, J. S. Ha, K. M. Woo, S. J. Choi, and C. H. Chung. 2000. Heptameric ring structure of the heat-shock protein ClpB, a protein-activated ATPase in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 303:655-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kosk-Kosicka, D., T. Bzdega, and A. Wawrzynow. 1989. Fluorescence energy transfer studies of purified erythrocyte Ca2+-ATPase. Ca 2+-regulated activation by oligomerization. J. Biol. Chem. 264:19495-19499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krause, S., M. Barcena, W. Pansegrau, R. Lurz, J. M. Carazo, and E. Lanka. 2000. Sequence-related protein export NTPases encoded by the conjugative transfer region of RP4 and by the cag pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori share similar hexameric ring structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:3067-3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krause, S., W. Pansegrau, R. Lurz, F. de la Cruz, and E. Lanka. 2000. Enzymology of type IV macromolecule secretion systems: the conjugative transfer regions of plasmids RP4 and R388 and the cag pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori encode structurally and functionally related nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases. J. Bacteriol. 182:2761-2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krishna, S. S., I. Majumdar, and N. V. Grishin. 2003. Structural classification of zinc fingers: survey and summary. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:532-550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Libante, V., L. Thion, and D. Lane. 2001. Role of the ATP-binding site of SopA protein in partition of the F plasmid. J. Mol. Biol. 314:387-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsh, J. W., and R. K. Taylor. 1998. Identification of the Vibrio cholerae type 4 prepilin peptidase required for cholera toxin secretion and pilus formation. Mol. Microbiol. 29:1481-1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okamoto, S., and M. Ohmori. 2002. The cyanobacterial PilT protein responsible for cell motility and transformation hydrolyzes ATP. Plant Cell Physiol. 43:1127-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Planet, P. J., S. C. Kachlany, R. DeSalle, and D. H. Figurski. 2001. Phylogeny of genes for secretion NTPases: identification of the widespread tadA subfamily and development of a diagnostic key for gene classification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:2503-2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Possot, O., and A. P. Pugsley. 1994. Molecular characterization of PulE, a protein required for pullulanase secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 12:287-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Possot, O. M., and A. P. Pugsley. 1997. The conserved tetracysteine motif in the general secretory pathway component PulE is required for efficient pullulanase secretion. Gene 192:45-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pozidis, C., A. Chalkiadaki, A. Gomez-Serrano, H. Stahlberg, I. Brown, A. P. Tampakaki, A. Lustig, G. Sianidis, A. S. Politou, A. Engel, N. J. Panopoulos, J. Mansfield, A. P. Pugsley, S. Karamanou, and A. Economou. 2003. Type III protein translocase: HrcN is a peripheral ATPase that is activated by oligomerization. J. Biol. Chem. 278:25816-25824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Py, B., L. Loiseau, and F. Barras. 1999. Assembly of the type II secretion machinery of Erwinia chrysanthemi: direct interaction and associated conformational change between OutE, the putative ATP-binding component and the membrane protein OutL. J. Mol. Biol. 289:659-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rivas, S., S. Bolland, E. Cabezon, F. M. Goni, and F. de la Cruz. 1997. TrwD, a protein encoded by the IncW plasmid R388, displays an ATP hydrolase activity essential for bacterial conjugation. J. Biol. Chem. 272:25583-25590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robien, M. A., B. E. Krumm, M. Sandkvist, and W. G. Hol. 2003. Crystal structure of the extracellular protein secretion NTPase EpsE of Vibrio cholerae. J. Mol. Biol. 333:657-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakai, D., T. Horiuchi, and T. Komano. 2001. ATPase activity and multimer formation of Pilq protein are required for thin pilus biogenesis in plasmid R64. J. Biol. Chem. 276:17968-17975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandkvist, M. 2001. Biology of type II secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 40:271-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandkvist, M., M. Bagdasarian, S. P. Howard, and V. J. DiRita. 1995. Interaction between the autokinase EpsE and EpsL in the cytoplasmic membrane is required for extracellular secretion in Vibrio cholerae. EMBO J. 14:1664-1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandkvist, M., L. O. Michel, L. P. Hough, V. M. Morales, M. Bagdasarian, M. Koomey, V. J. DiRita, and M. Bagdasarian. 1997. General secretion pathway (eps) genes required for toxin secretion and outer membrane biogenesis in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 179:6994-7003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandkvist, M., V. Morales, and M. Bagdasarian. 1993. A protein required for secretion of cholera toxin through the outer membrane of Vibrio cholerae. Gene 123:81-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Savvides, S. N., H. J. Yeo, M. R. Beck, F. Blaesing, R. Lurz, E. Lanka, R. Buhrdorf, W. Fischer, R. Haas, and G. Waksman. 2003. VirB11 ATPases are dynamic hexameric assemblies: new insights into bacterial type IV secretion. EMBO J. 22:1969-1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sexton, J. A., J. S. Pinkner, R. Roth, J. E. Heuser, S. J. Hultgren, and J. P. Vogel. 2004. The Legionella pneumophila PilT homologue DotB exhibits ATPase activity that is critical for intracellular growth. J. Bacteriol. 186:1658-1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sossong, T. M., Jr., M. R. Brigham-Burke, P. Hensley, and K. H. Pearce, Jr. 1999. Self-activation of guanosine triphosphatase activity by oligomerization of the bacterial cell division protein FtsZ. Biochemistry 38:14843-14850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turner, L. R., J. W. Olson, and S. Lory. 1997. The XcpR protein of Pseudomonas aeruginosa dimerizes via its N-terminus. Mol. Microbiol. 26:877-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whitchurch, C. B., M. Hobbs, S. P. Livingston, V. Krishnapillai, and J. S. Mattick. 1991. Characterisation of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa twitching motility gene and evidence for a specialised protein export system widespread in eubacteria. Gene 101:33-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou, J., and Z. Xu. 2003. Structural determinants of SecB recognition by SecA in bacterial protein translocation. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10:942-947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]