Abstract

The natural wild-type Bacillus subtilis strain 3610 swarms rapidly on the synthetic B medium in symmetrical concentric waves of branched dendritic patterns. In a comparison of the behavior of the laboratory strain 168 (trp) on different media with that of 3610, strain 168 (trp), which does not produce surfactin, displayed less swarming activity, both qualitatively (pattern formation) and in speed of colonization. On E and B media, 168 failed to swarm; however, with the latter, swarming was arrested at an early stage of development, with filamentous cells and rafts of cells (characteristic of dendrites of 3610) associated with bud-like structures surrounding the central inoculum. In contrast, strain 168 apparently swarmed efficiently on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar, colonizing the entire plate in 24 h. However, analysis of the intermediate stages of development of swarms on LB medium demonstrated that, in comparison with strain 3610, initiation of swarming of 168 (trp) was delayed and the greatly reduced rate of expansion of the swarm was uncoordinated, with some regions advancing faster than others. Moreover, while early stages of swarming in 3610 are accompanied by the formation of large numbers of dendrites whose rapid advance involves packs of cells at the tips, strain 168 advanced more slowly as a continuous front. When sfp+ was inserted into the chromosome of 168 (trp) to reestablish surfactin production, many features observed with 3610 on LB medium were now visible with 168. However, swarming of 168 (sfp+) still showed some reduced speed and a distinctive pattern compared to swarming of 3610. The results are discussed in terms of the possible role of surfactin in the swarming process and the different modes of swarming on LB medium.

We have recently described a wide range of swarming patterns, including successive waves of dendritic branching, followed by consolidation, of the wild-type strain 3610 on the surface of a synthetic agar medium (9). A simpler, apparently nondendritic swarming pattern of Bacillus subtilis on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar has also been described (9, 10), in particular, with the wild-type strain 3610, although the details of the intermediate stages of these swarm communities during development have not so far been reported. In contrast, we showed that the formation of the complex branching communities on the synthetic B medium, as detected by an in situ microscope analysis, is unexpectedly complex, with a precise developmental program accompanied at different stages of the swarming process, for example, by the appearance of long filamentous cells and rafts of tightly aligned cells. There was no evidence, however, that these types of cells were directly involved in swarming per se (9). Moreover, in our previous study we also detected the apparent migration of large numbers of individual cells prior to their aggregation into the tips of nascent dendrites. This suggested that, in at least some stages of the swarming process, migration does indeed proceed independently of the morphologically differentiated cells. This finding is in contrast to the role of elongated “swarmer” cells that have been observed in Proteus mirabilis (18).

Other studies have shown that both surfactin (Srf) and flagella are required for swarming (16, 27) of different B. subtilis strains. A recent study (20) also demonstrated swarming associated with a mutation leading to hyperflagellation, under conditions where the parental laboratory strain normally failed to swarm. However, other studies have described forms of swarming in B. subtilis apparently independent of flagella or surfactin (6, 12), (14).

Nakano et al. (15) first showed that strain 168 failed to produce the antibacterial peptide surfactin due to a frameshift mutation in sfp encoding a 4′ phosphopantetheinyl transferase. Sfp is required to activate (via posttranslational modification) each of the four surfactin synthases Srf A, Srf B, Srf C, and Srf D, necessary for the nonribosomal assembly of the surfactin heptapeptide. Surfactin synthesis, at least in liquid cultures, is regulated by a quorum-sensing mechanism, mediated via production of the pheromone ComX, which is then detected, as it accumulates in the medium, by the two-component signal transduction system ComA and ComP (5, 21, 22). Kearns and Losick (10) demonstrated that a mutant of the natural wild-type strain 3610, defective in the synthesis of surfactin, failed to swarm on a complex medium. Similarly, Kearns and Losick showed that all the laboratory 168 strains examined by them failed to swarm on LB agar, including PY79, which still failed to swarm even when purified surfactin was added to the plates. Moreover, these investigators recently identified three genes of unknown function required for swarming, including swrA, found to be defective in their laboratory strains, indicating that an additional function was required for swarming, although not for swimming, in this strain.

The release of different types of extracellular material to facilitate swarming in some way, presumably through physical changes to the surface terrain, have also been reported: polysaccharide in P. mirabilis (8), lipopolysaccharide in Salmonella enterica (23), rhamnolipids in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (11), and a cyclic lipopeptide in Serratia marcescens (13). In the last case, in particular, the surfactant (serrawettin) was shown also to be required for flagella-independent spreading on a low-agar (0.35%) medium. However, precisely how any of these compounds promotes surface translocation is unclear.

Production of the extracellular protease Epr, dependent upon the transcription factor sigma D, was also shown to be required for swarming in B. subtilis (6). Kearns and Losick (10) demonstrated that mutations in cheA and cheY reduced the swarming speed of strain 3610 on LB agar. All these studies suggest that the precise requirements for swarming (and in some cases the type or pattern of swarming) may be complex, depending upon the composition of the medium and the nature of the particular laboratory, or so-called undomesticated, strain being used. In our view, however, it is important that the commonly employed procedures involving, for example, simple viewing of the mature wild-type or mutant swarm after a 24-h incubation, leaves much informative detail of the different intermediate stages (both macroscopic and microscopic) completely unseen. Thus, potentially important mutant phenotypes, as we now demonstrate, can be masked by later overgrowth of the patterns by multiplication of the cells.

In this study, we have analyzed the swarming capacity of the laboratory strain 168 (trp), which fails to produce surfactin, on different media in comparison with the wild-type 3610 strain. This involved the analysis, both macroscopic and microscopic (in situ), of the intermediate stages of development of the swarm community, the role of flagella, the composition of the medium, and the role of surfactin. In particular, as a basis for a future detailed analysis of the mechanism of the swarming, we considered it important to establish a time course of the process. Flagella were required under all conditions for swarming of strain 168 (trp). The requirement for surfactin in 168 could be bypassed on LB medium. However, this form of swarming showed distinctive features in comparison to swarming of the natural wild-type strain. Restoration of the production of endogenous surfactin in strain 168 resulted in the appearance of many features of the wild-type swarming process, yet the 168 pattern of swarming remained distinctive in comparison with that of strain 3610. Finally, the in situ microscopic analysis demonstrated some novel features of the swarming process in strain 3610, including a pseudopodial-like movement of packs of cells at the tips of dendrites at the swarm front.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. B. subtilis strains were grown in LB medium, TY medium (10 g of tryptose per liter, 5 g of yeast extract per liter, 5 g of NaCl per liter), Columbia medium (Difco), peptone (5g/l), E medium (120 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 70 mM NaCl, 20 mM KCl, 20 mM NH4Cl, 70 mM Na2SO4, 0.1 M MgCl2, 0.5 mM ZnCl2, 0.5% bactopeptone, 0.5% glucose, 0.02% casamino acids) or the synthetic B medium, which contains 15 mM (NH4)2SO4, 8 mM MgSO4 · 7H2O, 27 mM KCl, 7 mM sodium citrate · 2H2O, and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) supplemented with 0.6 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM CaCl2 · 2H2O, 1 mM FeSO4 · 7H2O, 10 mM MnSO4 · 4H2O, 4.5 mM glutamic acid, 780 μM tryptophan, 860 μM lysine, and 0.2% (wt/vol) glucose (2). All plates were prepared by supplementing the medium with 0.7% or the required concentration of agar.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this studya

| Strain | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| 168 | trpC2 | 1 |

| 168 hag mutant | trpC2, hag::pMutin4 | This work |

| 168 sfp+ | trpC2, amyE::sfp | This work |

| 3610 | Natural isolate | Bacillus Genetic Stock Center Collection |

| OKB 105 | pheA1, sfp | Bacillus Genetic Stock Center Collection |

| OKB 120 | pheA1, sfp, srfA::Tn917 isogenic with OKB 105 | Bacillus Genetic Stock Center Collection |

| BD 79 | leuB1, pheA1 | 19 |

| PDG1662 | pDG268 Spcr | 7 |

| pMutin 4 | pBR322 lacZ lacI Ermr pspac | 25 |

| pMutin 4 hag mutant | pMutin4-hag (aa 23-870) | This work |

| pSV-sfp | pBD64-pUC8 Neor Cmr | 15 |

aa, amino acids.

Construction of the hag mutant of strain 168 and the sfp+ 168 strain.

The hag inactivation mutant was constructed by PCR amplification of the hag region by using wild-type 168 genomic DNA as a template with Hag1 (GGCCAAGCTTGCAGCTTAACACACTG) and Hag 2 (CCGGGGATCCCAAGTTCTTTTGATTTGCAGG) primers. The amplified fragment was cloned into pMutin4 (26) at the BamHI and Hind III restriction sites. The resulting plasmid pMutin4 hag-inac was used to transform strain 168. Selection was carried out on LB agar plates containing 5 μg of erythromycin per ml and 12.5 μg of lincomycin per ml. The integration of the plasmid into the chromosome was verified by PCR and sequencing. The sfp+ 168 strain was constructed by PCR amplification of the sfp gene region by using pSV-sfp plasmid DNA as a template and with the sfp 1 CTATGGATCCCTTGTGGAAGTATGATAGG and sfp 2 (GGGTGAATTCTGAGGCGATAGACCGTCTA) primers. The amplified fragment was cloned into pDG1662 (amyE locus integrative vector [7]) at the BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites. The resulting plasmid pDG1662-sfp was used to transform strain 168. Selection was carried out on LB agar plates containing 5 μg of chloramphenicol per ml.

Transformation.

A total of 10 ml of minimal salts medium (MSM) [0.2% (NH4)2SO4, 1.4% K2HPO4, 0.6% KH2PO4, 0.1% sodium citrate, 0.02% MgSO4, 0.5% glucose, 4% tryptophane, 0.02% casamino acids, 2 mg of ferric ammonium citrate per liter] was inoculated with a single colony and shaken overnight at 37°C. The culture was diluted 10 times in fresh MSM and grown for 3 h at 37°C. After this time, the culture was diluted 1:1 in warm (37°C) starvation medium [0.2% (NH4)2SO4, 1.4% K2HPO4, 0.6% KH2PO4, 0.1% sodium citrate, 0.02% MgSO4, 0.5% glucose] and the growth was continued for 2 h. To 100 μl of the culture, 0.2 μg of plasmid (pSV-sfp) (15) DNA was added, and tubes were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. A total of 300 μl of LB medium was added to the tubes, and incubation was continued for another 1 h to allow the expression of antibiotic resistance genes. The tubes were centrifuged for 3 min at 13,000 × g, and the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of LB medium and plated out on LB plates with appropriate antibiotics.

Swarming experiments.

For B medium experiments, 10 ml was inoculated with a single colony and shaken overnight at 37°C. The culture was diluted to an optical density at 570 nm (OD570) of ≅0.1 and grown until an OD570 of ≅0.2 was reached. This procedure was repeated twice, and finally the culture was grown to time T4 (4 h after exit from exponential phase); the OD570 was measured and the culture was diluted to an OD570 of ≅0.01. A total of 2 μl (≈104 CFU) of the diluted culture was placed at the center of an agar plate and incubated at 30°C (relative humidity, 40% saturation) or other temperatures as indicated in the text, for the requisite time. The inoculum formed a spot, with a diameter of 4 mm. Plates (10 cm) containing 25 ml of agar medium were prepared 1 h before final inoculation and dried, open, for 15 min in a laminar flow chamber. For measuring swarming rates, the diameter of the swarm on duplicate plates was measured each hour after swarming commenced. Measurements from replicate plates were essentially identical. For LB experiments we followed the procedure of Kearns and Losick (10), which requires an inoculum of 107 bacteria (CFU) and incubation at 37°C.

Microscope observations.

The photographs of the developing swarm were taken in situ with a phase-contrast Axioplan (Zeiss) microscope equipped with a camera (Princeton Instruments). Bacteria were observed on the plates by using Neofluar Zeiss objectives of 1.25×, 5×, 20×, and 40×. Images were captured by using the IP Lab Spectrum (Princeton Instruments) software version 4.2, exported as TIFF files, and adjusted with Adobe Photoshop software (Mountain View, Calif.). Plates were removed from the incubator at intervals and examined for a minimal time to avoid any delay in further swarming, or several replicate plates inoculated at the same time were employed, discarding the plate after microscope examination. Replicate swarm plates were highly reproducible in both the timing and pattern of the swarming colony.

RESULTS

The laboratory strain 168 (trp) fails to produce surfactin, but swarming ability depends upon the composition of the medium.

First, we confirmed, by using a blood hemolysis test, that strains 168 (trp), OKB 120, and BD79 (19) all failed to produce any detectable hemolytic activity, compared with the natural wild-type strain 3610. These strains, as reported previously for other 168 derivatives, therefore fail to produce surfactin and are presumably mutant sfp strains, as originally described by Nakano et al. (15) Sfp 4′ phosphopantetheinyl transferase is required to activate posttranslationally the four peptide synthetases, Srf A, Srf B, Srf C, and Srf D.

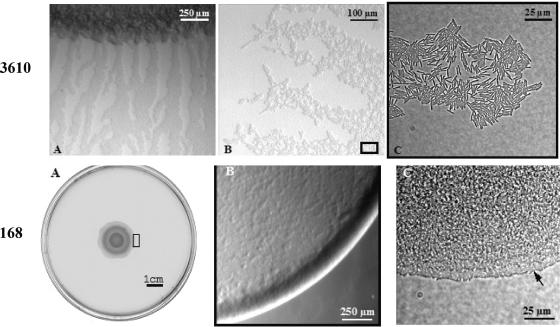

In order to assess the role of surfactin further, we examined the swarming behavior of our laboratory strain 168 (trp) at 30°C on a range of media (0.7 to 2% agar) previously described as supporting swarming in B. subtilis. Figure 1 shows that, as reported previously under identical conditions (9), swarming of B. subtilis on peptone (2% agar) and particularly on Columbia medium is extremely slow, requiring up to 10 days to develop. It should be emphasized that when grown in liquid medium, the two strains displayed identical growth rates. Considering the patterns on Columbia, TY, or peptone medium shown in Fig. 1, it might be debatable whether this represents true swarming. Nevertheless, as shown in Fig. 1, the natural wild-type 3610 strain gives similar, slow-swarming patterns on these media. Moreover, the swarming behavior of strain 168 on TY or peptone medium is in contrast to the complete absence of swarming of the same strain on the synthetic B medium or E medium, even after 10 days of incubation (data not shown).

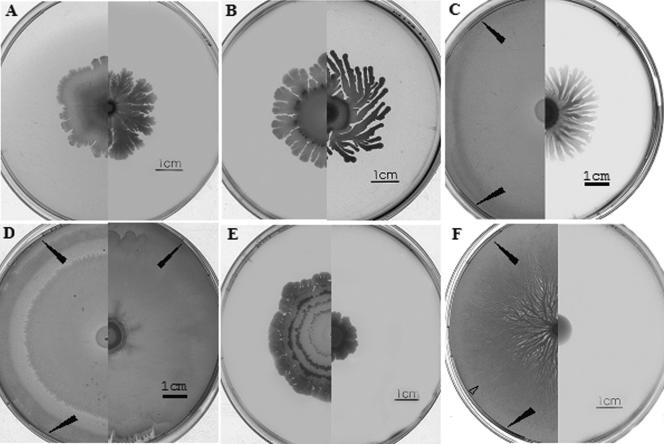

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the swarming patterns for 3610 (left sides of plates) and 168 (trp) (right sides of plates). Plates were prepared and inoculated for swarming experiments as described in Materials and Methods. Panel A, peptone 2% agar (3) after 10-day incubation; panel B, TY-1% agar-medium after 6-day incubation; panel C, LB medium with no added NaCl after 24-h incubation; panel D, LB medium after 24-h incubation; panel E, Columbia medium-1% agar after 10-day incubation; panel F, B medium after 24-h incubation. Agar concentrations are 0.7% unless otherwise indicated. Plates C and D were incubated at 37°C; all others were incubated at 30°C. A composite of two photographs is presented for direct comparisons. Black arrows indicate where the swarms have reached the edges of the plates; the open arrow in panel F indicates the transition point between swarm 1 and swarm 2.

A previous study (19) demonstrated that swarming by some 168 strains can be contaminated by type 1 bacilli, which characteristically, unlike B. subtilis, are lac+ and antibiotic resistant. Importantly, in the present study, when the experiments shown in Fig. 1 were repeated on X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) plates, all swarm communities remained white; i.e., like 168 they were lac negative. Moreover, all cells removed from the extremities of these swarms carried a trp mutation and were antibiotic sensitive, as expected for strain 168. Therefore, the observed swarming behavior on peptone and TY media in Fig. 1 was due to strain 168 (trp) alone.

As we showed previously (Fig. 1F), strain 3610 grown on B medium swarms rapidly to produce complex dendritic patterns after 24 h, whereas 168 (trp) fails to swarm on this synthetic medium. Similarly, on the synthetic medium E, although fortified with casamino acids and Bacto Peptone, strain 168 (trp) failed to swarm. In contrast, and despite the absence of surfactin production by strain 168 (trp), this strain unexpectedly appeared to swarm on LB -agar; it produced a dense multilayered swarm after 20 to 24 h that was similar in extent to that of strain 3610 (Fig. 1D), although, as shown below, the rate of swarming was substantially reduced. As also shown in Fig. 1C, LB medium lacking NaCl (normally 18 mM) still permits swarming of strain 168, but now swarming is slower and the pattern is dendritic although with less branching. These results further underline the complex interaction between cells and the composition of the medium, which chemically or physically, in some still unknown way, probably influences the importance of surfactin. The requirements for the swarming behavior of strain 168 (trp) under different conditions in comparison to the swarming strain 3610 was, therefore, examined in more detail.

Flagella are required for swarming by 168 (trp) under all conditions.

It was important to test the requirement for flagella in the swarming of strain 168 (trp) on different media. Therefore, a strain was inactivated for hag, the structural gene for flagellin, as described in Materials and Methods. This strain completely lacked flagella when examined by electron microscopy (data not shown). In comparison to the parental strain, the 168 (trp, hag) strain completely failed to swarm on all media tested, including on B medium as shown in Fig. 2. Importantly, Fig. 2 also shows that the swarming of 168 (trp) on B medium and E medium, facilitated by the addition of purified surfactin, was also hag dependent.

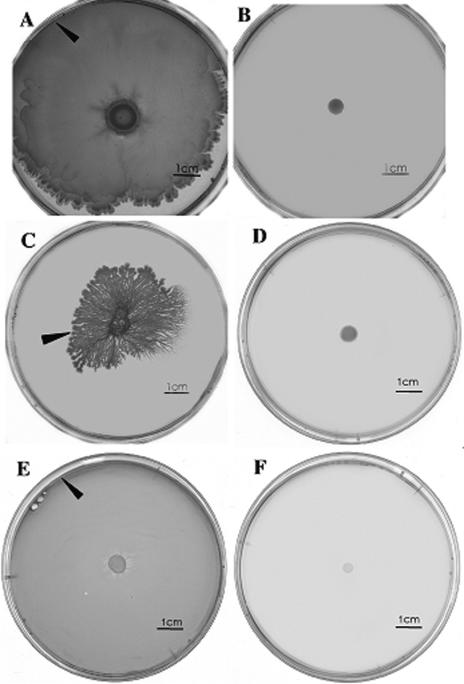

FIG. 2.

Flagella are required for swarming under all conditions. A hag mutant of strain 168 lacking flagellin production was constructed as described in Materials and Methods, and swarming was compared with the hag+ strain on different media. Swarming of the hag+ strain on LB medium (A), B medium (C), and E medium (E) contrasts with the absence of swarming in of the hag mutant strain in panels B, D, F. Strain 168 fails to swarm on either B or E medium, but swarms when surfactin is added to the plate at the time of inoculation (C and E). The hag mutant strain fails to swarm even in the presence of surfactin (D and F). All incubations 24 h at 30°C. Arrows mark the edges of the swarms.

An expanding ring of surfactin, detectable prior to the initiation of swarming and always preceding the swarm front of strain 3610, is visible by reflected light.

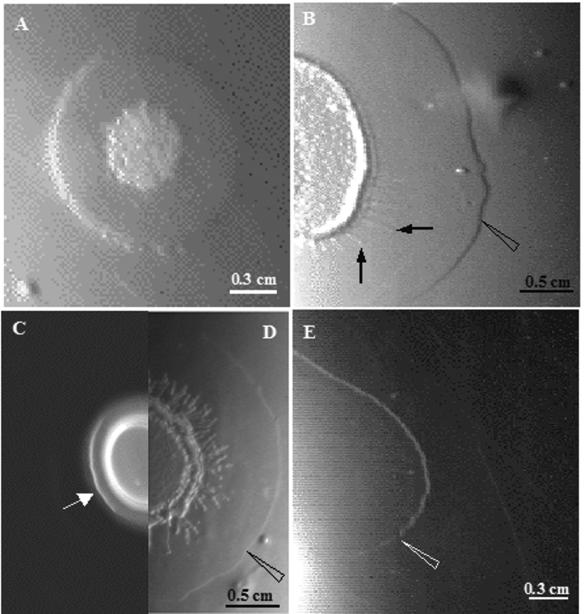

We observed previously that an expanding zone, delimited by a narrow (1-mm) ring, preceded the swarm front of the natural wild-type 3610 strain on synthetic B medium throughout the entire swarming process (9). Such a ring, visible when observed or photographed by reflected light, is first observed on B medium after approximately 10 h of incubation (Fig. 3A) before swarming at the macroscopic level (panel B) can be detected. Examination at high magnification directly under the microscope confirmed that the zone ahead of the swarm front, delimited by the ring, is completely devoid of bacteria. The ring can also be detected preceding the swarm front of strain 3610 on LB medium (Fig. 3B). In contrast, this ring is not detectable on LB agar ahead of the expanding swarm of the surfactin-defective strain 168 (trp) (Fig. 3C). However, in strain 168 carrying the sfp gene on plasmid pSV-sfp (see Materials and Methods for construction), the ring is detectable (data not shown). In fact, as also shown in Fig. 3E, surfactin itself spotted onto a 0.7% agar plate in the absence of bacteria spreads rapidly (within a few minutes) to form a wide, irregular zone delimited by an apparently identical narrow ring. Therefore, we conclude that the observed phenomenon represents an expanding zone of surfactin itself, produced and secreted by the cells in a highly coordinated fashion throughout the swarming process.

FIG. 3.

The transparent zone and delimiting ring preceding the swarm front is only observed in the presence of surfactin. (A) Strain 3610 on B medium after 10 h; the ring is detected before dendrites emerge. (B) Strain 3610 on B -medium. The ring at 12 h is 5 to 6 mm ahead of the first waves of dendrites. (C) Strain 168 (trp) on LB medium at 300 min, showing the swarming front advancing (indicated by arrow) but no surfactin ring. (D) Strain 3610 on LB medium after 30 min, showing the surfactin ring detected ahead of dendrites. Panels C and D are shown in a composite photograph for comparison. (E) Plate with 10 μl (1 mg/ml) of purified surfactin spotted on the plate and allowed to spread for 5 min. All plates contained 0.7% agar and were photographed by reflected light. Filled arrows indicate the edges of the swarm zones; open arrows indicate the surfactin outer borders. The background difference in illumination of panel C in contrast to panel D is due to the necessity of using reflected light to photograph the ring.

Swarming of strain 168 (trp) on B and on E media can be partially restored and swarming on LB can be accelerated by the addition of exogenous surfactin.

The results described above with respect to the swarming of 168 (trp) on LB medium are in contrast to those obtained with the 168 strains analyzed by Kearns and Losick (10), all of which failed to swarm on the identical LB medium. This indicates that the laboratory strain 168 (trp) used here, although unable to produce surfactin, may lack no other major swarming function and in some way is still able to swarm on LB agar, perhaps through an alternative mechanism (see Discussion). We have tested versions of the 168 strains obtained from other laboratories, for example, OKB120 and BD79, and these do indeed fail to swarm on LB agar (19). This result prompted further detailed analysis of the nature of swarming of 168 (trp) and the role of surfactin. First, it is important to note here that for swarming on B medium or LB agar, two different protocols were employed. For B medium (and most other media) we used the protocol developed previously for maximum reproducibility of the branched swarming patterns for strain 3610 that is accompanied by multiple waves of migration (Fig. 1F) (9). This involves incubations at 30°C with a standardized inoculum of 104 CFU (see Material and Methods). In contrast, for swarming on LB agar, we adopted the procedure described by Kearns and Losick (10), namely incubation at 37°C with an inoculum of 107 CFU (see Materials and Methods). In consequence of the higher temperature and larger inoculum, swarming of the natural wild-type strain 3610 on LB agar commences after 30 min and is largely completed in 3 h. In contrast, with the protocol used for B medium, swarming commences after approximately 11 h and requires at least 24 h to be completed.

In order to test the requirement for surfactin on swarming of strain 168 (trp), surfactin (1 μg/ml) was added to the center of the plates at the time of inoculation, and the effect on subsequent swarming was analyzed on LB agar and on E and B media, where swarming of strain 168 (trp) is normally not seen. The results (Fig. 2E) demonstrated that essentially normal patterns of swarming were obtained on E medium after 24 h. On the synthetic B medium (Fig. 2C), although the dendritic pattern characteristic of strain 3610 on this medium was obtained, the extent of swarming of 168 (trp) was still reduced compared to that of 3610 (Fig. 1F). Notably, in the presence of added surfactin, strain 168 swarming appeared to be relatively uncoordinated, that is, with an asymmetric expansion of the swarm front. The results on B medium may indicate that strain 168 lacks an additional factor for swarming on this medium or that the simple addition of surfactin, without coordination of synthesis, secretion, and concomitant movement of cells, is insufficient on this medium to permit normal development of the swarm.

The presence of pSV-sfp in strain 168 (trp) restores some important features of the swarming process.

As indicated in Fig. 4B, strain 168 (trp), unlike 3610 (panel E), fails to swarm on the synthetic B medium. However, when the culture is examined at higher magnification (Fig. 4A), distinctive bud-like structures formed by the association of many cells are visible along the rim of the central inoculum. Notably, the center of the inoculum point and an area extending into the base of the bud are multilayered, containing many long filamentous cells, while the leading edge of the bud (Fig. 4A, arrows) is formed by a narrow monolayer of bacteria, including rafts of 4 to 6 aligned cells observable at higher magnification (data not shown). Such filamentous cells and rafts are characteristic features of fully formed dendrites of strain 3610 grown on this medium (9). In strain 168 (trp) these bud-like structures never develop into dendrites.

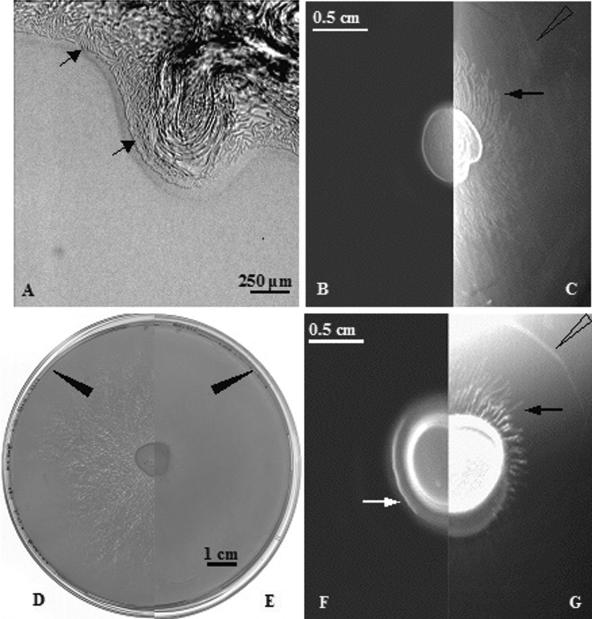

FIG. 4.

The effect of pSV-sfp, which directs the synthesis of surfactin, on early swarm development.(A) Growth on B medium, showing the rim of the inoculation spot (magnification, ×62.5) after incubation of strain 168 (trp) for 15 h. The aborted bud, containing multilayers of filamentous cells and a leading monolayer that includes rafts of cells (indicated by arrows), fails to develop into dendrites (see text for other details). (B) Growth on B medium, showing no swarming and the stalled inoculation center for strain 168 (trp). (C) Strain 168 (trp, pSV-sfp) on B medium. Early-stage dendrite formation (edge marked by the black arrow) is evident. (D) Strain 168 (trp, pSV-sfp) on B medium after 24 h.(E) B medium with a 3610 swarm after 24 h. Arrows indicate edges of the swarm in both panels. (F and G) Swarming of strains 168(trp) and 168(trp, pSV-sfp) on LB medium after 4 h, with, respectively, nondendritic and dendritic swarm fronts indicated by filled arrows. Large open arrows in panels C and G mark the outer surfactin borders. Reflected light was required to photograph the rings in panels C and G, which is the reason for the difference in background illumination.

In order to confirm the importance of the sfp gene and, therefore, of surfactin production for the swarming of strain 168 (trp), we took advantage of the plasmid constructed by Nakano et al. (15). This multicopy plasmid carries the wild-type sfp gene and a short upstream region including the promoter (15). This plasmid was transformed into strain 168 (trp) (see Materials and Methods), and the ability of this strain to swarm was tested on different media. The results obtained indicated that important features of swarming displayed by strain 3610 are now also manifest by the 168 (pSV-sfp) strain. Thus, as shown in Fig. 4, when 168 (pSV-sfp) expresses surfactin on B medium (Fig. 4, compare B and C), development progresses beyond the bud stage and dendrites now develop. Moreover, the swarm (168-pSV-sfp) finally extends to the edge of the plate after 24 h (Fig. 4D). Comparison of panels F and G in Fig. 4 also shows that the formation of dendrites, characteristic of strain 3610 on LB agar early in the swarm process, are produced in 168 (trp) where pSV-sfp is present (see Fig. 6 for views at higher magnification). These results further confirm the importance of surfactin in affecting the pattern of development of the swarm community.

FIG. 6.

Differences in the organization of the swarm front in strains 3610 and 168 on LB agar at 37°C. (Top row, A) Plate photographed (magnification, ×15.6) in situ at 30 min after inoculation, with the 3610 swarm proceeding from the top. (Top row, B) Higher magnification (×62.5) shows loose packing of cells, irregular edges, and, in particular, the multiplicity (fragmentation) of the leading tips of these nascent dendrites. (Top row, C) Higher magnification (×250) of the boxed region in panel B shows the increased packing of cells at the leading edges. (Bottom row, A) The early stage of initial swarming of strain 168 (4 h). (Bottom row, B) The boxed region of panel A examined in situ and at higher magnification (×15.6), with the center of the swarm beyond the top left corner. Cells appear to be multilayered at the swarm front (Bottom row, C) At higher magnification (×250), a section of the front with a multilayered interior and a narrow monolayer of cells (arrow) at the leading (advancing) edge.

Analysis of intermediate stages of development of swarms of an sfp mutant of B. Subtilis and of B. Subtilis sfp+ on LB agar.

The results described above indicated that surfactin production by the natural wild-type 3610 strain is a very early event that precedes any detectable swarming from the central inoculation site. The results also indicated that the surfactin-negative strain 168 (trp, sfp) was unable to swarm on B or E medium unless surfactin was present or added to the plates or when it was encoded by plasmid pSV-sfp. On the other hand, apparently efficient swarming of strain 168 nevertheless still occurred on LB agar in the absence of surfactin, at least when cultures were viewed after 24 h at 37°C. In order to compare more carefully the swarming behavior of the 3610 and 168 strains and, therefore, to clarify further the role of surfactin on growth on LB agar, it was necessary to examine some of the intermediate stages in the development of the swarm community for strains 3610, 168(trp), and derivatives of 168 expressing the wild-type sfp. For the last, we employed the strain (carrying the pSV-sfp plasmid) as well as a construct 168 amyE::sfp carrying a single copy of sfp inserted into the amyE locus in the chromosome and under the control of its own promoter (see Materials and Methods). These strains now release surfactin, and the ring preceding the swarm is clearly visible (data not shown).

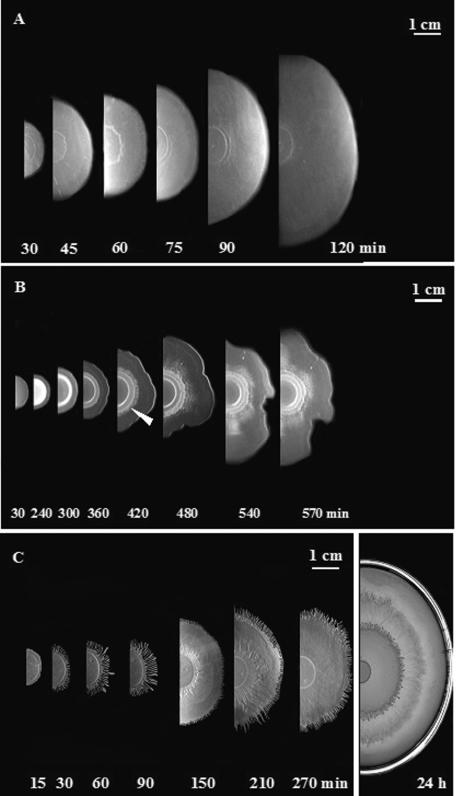

To compare swarming of the four strains, LB plates were inoculated and incubated at 37°C, and the development of the swarms was observed and photographed at intervals. Importantly, during the very rapid first phase of swarming, particularly of strain 3610 on LB agar, we observed that the swarm front reaches the edge of the plate while still essentially forming a monolayer of cells. In consequence, these critical early stages, preceding any multiplication or consolidation phase are extremely difficult to see and can only be observed and photographed by reflected light. A series of results of such a macroscopic study are shown in Fig. 5. With 3610 (Fig. 5A), swarming is already detectable at 30 min, and the swarm expands rapidly, apparently with the front advancing symmetrically in a seemingly coordinated fashion. At the very early stages, up to approximately 75 min, although not visible in these photographs (see Fig. 6 for views at higher magnification), the swarm front is seen to be composed of many closely packed dendrites with early branching already detectable. However, these dendritic structures are no longer visible by about 75 min, presumably due to lateral fusion and the dense packing of many new dendrites, so that individual dendrites can no longer be detected.

FIG. 5.

Intermediate stages in the development of swarms by strains 3610 (A) and 168 (B) and 168 (sfp+) (C) reveal important differences associated with the presence or absence of surfactin. Swarms were inoculated in the center of the LB plates (at left), incubated at 37°C, and photographed by reflected light at intervals. Swarming of 168 is slower than 3610 and progressively less symmetrical, and at least one additional wave of swarming (indicated by an arrow) is detected. The presence of sfp+ in 168 accelerates swarming and allows dendrite formation, but the overall pattern of swarming shows important differences compared to 3610.

As shown in Fig. 5B, in contrast, the onset of swarming of strain 168 is delayed 4 to 5 h and then expands at an average rate that is at least fivefold less than that of strain 3610. Moreover, the expansion of the 168 swarm becomes progressively less coordinated. In addition, at least one additional swarm front (Fig. 5B, arrow) appears to develop at about 420 min, showing even less symmetry. The results showed, therefore, that although strain 168 (lacking surfactin) is able to swarm on LB medium, the analysis of the intermediate stages revealed a number of important differences compared to the growth of strain 3610. In contrast, as shown in Fig. 5C, the 168 strain carrying sfp+ in the amyE locus, like 3610, initiated swarming after 30 min, and the swarm front contained many dendrites. Nevertheless, the speed of swarming is still slower than that of strain 3610 (0.5 cm/h compared with 1.3 cm/h), and well-separated dendrites persist with apparently distinct waves of swarming. Virtually identical results were obtained with the strain carrying the pSV-sfp plasmid.

These results confirm that the expression of surfactin production in strain 168 clearly results in many features of the swarm process characteristic of strain 3610. Nevertheless, the 168 sfp+ strain still shows significant differences, and this indicates that the laboratory strain 168 still differs from the natural wild type with respect to a factor not essential for swarming but capable of modulating the swarming pattern.

The nature of the swarm fronts of 3610 and 168 on LB medium shows marked differences.

Some of the early stages of the swarming process on LB agar plates inoculated with either the surfactin-negative strain 168 (trp) or the natural wild-type 3610 were also examined microscopically in situ, without disturbing the growing cells. A typical selection of the results obtained is shown in Fig. 6. First, although the natural wild-type 3610, (Fig. 1D, left) when viewed after incubation for 24 h on LB agar, shows no obvious dendritic pattern, the initial stages of swarming (commencing around 30 min) are, in fact, accompanied by the formation of large numbers of dendrites emanating from the central point of inoculation, as shown at higher magnification (Fig. 6A and B, top row). These early dendrites are characterized by extremely irregular edges and, in most regions, loose packing of individual cells (Fig. 6B and C). In contrast, at the extreme tips of the dendrites, a small region is very tightly packed with cells (Fig. 6C), perhaps with a tendency for some cells to align. However, this latter organization is quite different from the tightly packed rafts (composed of 4 to 6 aligned cells) that eventually produce an almost crystalline-like formation, associated with the edges and undersurface of dendrites on the synthetic B medium (9). The swarm front at the early stages of swarming of strain 168 on LB medium is also shown in Fig. 6 (bottom row). In contrast to 3610, strain 168 formed no distinctive dendritic structures, and the swarm front in fact is composed of a monolayer of cells, forming a long continuous region extending several millimeters around the rim of the central inoculum. Magnified views of this front are shown in Fig. 6B and C (bottom row).

These results showed that the movement and perhaps the assembly of dendrites that accompany expansion of the community of 3610 are relatively symmetrical about the central point of inoculation. This suggests some mechanism that coordinates the movement of the entire swarm front. On the other hand, the initial and subsequent expansion of the swarm with strain 168, which lacks surfactin, does not involve dendrites, and the movement is significantly less coordinated, with segments of the community advancing at different speeds. In addition, as shown below the movement of the swarm front itself proceeds in a different manner in strain 168. These results confirmed that the superficially similar swarm patterns of strains 168 and 3610, as observed after a 24-h incubation (Fig. 1D) mask major differences in the detailed development of these swarms.

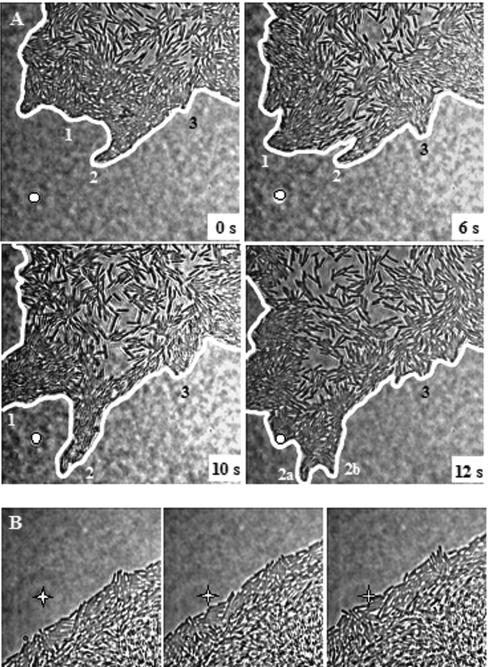

The cooperative activity of cells, associated with rapid pseudopodial-like movement of dendritic tips in strain 3610, is absent in strain 168.

More detailed analysis of the activity of cells at the swarm front of strain 3610, as shown in Fig. 7A, revealed a remarkable, pseudopodial-like movement at the tips of dendrites. Thus, where the population density of the cells is highest, groups or packs of cells advance rapidly in one region and then pause, while a group of cells in another region thrusts forward. Notably, however, behind the tip in the less packed areas, individual cells move forward to occupy spaces ahead as these become vacant (data not shown). In contrast, for 168 (trp), the cells at the forward edge move slowly and along a more uniform front (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Strains 3610 and 168(trp) display a different type of movement of the swarm front. (A) A pseudopodial-like movement of packs of cells at a leading tip of a 3610 dendrite on LB medium at 37°C after a 30-min incubation. Cells were photographed in situ at intervals (magnification, ×250). Two regions, 1 and 2 in particular, in comparison to region 3 (and the fixed spot in the foreground), successively move forward rapidly. Note the high-density packing of cells in the moving regions. Finally, in this series region 2 splits and region 2b advances (data not shown). (B) Strain 168 (surfactin negative) swarming under conditions identical to those of panel B. The swarm front was photographed in situ at 4 h after inoculation (magnification, ×250) at 1-min intervals. The cells advance slowly across a wide front toward the marker indicated by a star.

DISCUSSION

Surprisingly, although lacking surfactin production, strain 168 (trp) still swarmed on the rich LB medium, apparently almost as efficiently as the wild-type strain 3610, based on examination after 24 h. A more detailed analysis, however, revealed a number of important differences in the development of the swarm community when the intermediate stages for 168 (trp, sfp) and 3610 were compared. Thus, the onset of swarming was delayed, and the rate of progression of the swarm was substantially reduced in 168. Moreover, the normal symmetrical expansion of the swarm was quickly lost, and, unlike swarming of 3610, further expansion was relatively uncoordinated, with some regions of the swarm front advancing faster than others. Furthermore, strain 168 largely advances (albeit more slowly) along a single front rather than through the formation of many individual dendrites, as seen in the early stages of strain 3610 swarming on LB medium (compare Fig. 6 and 7). These results suggest to us that the production of surfactin does not only provide a physical path for the rapid surface translocation of cells but also in some way determines the assembly or aggregation of the cells into dendrites and coordinates their advance throughout the swarm front.

The laboratory strain 168 (trp) fails to produce surfactin and in comparison with the natural wild type, swarming patterns differ both qualitatively and quantitatively, including no swarming at all on the synthetic B medium. However, swarming per se could be restored by the addition of purified surfactin to the plates or endogenously by the presence of a plasmid encoding sfp+ or insertion of sfp+ into the chromosome. The latter encodes 4′ phosphopantetheinyl transferase, necessary for the activation of the four surfactin synthetases, and 168 strains were shown previously to be defective in sfp (15). The sfp+ strain initiated swarming on LB medium without a delay, formed dendrites, and swarmed relatively rapidly in a coordinated manner. Nevertheless, the swarming speed was less than half that of strain 3610, and the dendritic pattern was clearly distinct from that of the natural wild type. Thus, in comparison with 3610, the laboratory strain, in addition to the absence of surfactin production, differs with respect to another factor that, although not essential for swarming, modulates the later stages of development of the swarm community.

When surfactin, with its well-characterized ability to reduce surface tension and its antifoaming activity, is released by the bacteria ahead of the swarm, it presumably in some way counteracts the physical properties of the surface agar in order to permit the deployment of flagella. In the case of LB agar, the particular physicochemical composition of the medium may result, for example, in the retention of surface fluid and/or a suitable terrain for swarming, even without surfactin action. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that under these conditions on LB medium, the surfactin-negative strain 168 secretes other biosurfactants that modify the terrain ahead of the swarm front. B. subtilis is reported to produce different lipopeptides (24) which might fulfill such a role. This leads to the conclusion that alternative pathways of swarming might exist in B. subtilis, with different strategies available to counter the inhibitory physical forces to swarming. Interestingly, while this article was in revision, Connelly et al. (4) reported that the presence of extracellular proteases in B. subtilis wild-type strain A 164 could replace surfactin and permit swarming on LB medium (0.7% agar). As suggested by these authors, proteolytic digestion of surface proteins might release peptides and/or simply modify the surface of the cells in order to bypass the requirement for surfactin. It is important to point out that this behavior of B. subtilis, rapid swarming on LB medium without the endogenous surfactin, is still flagella dependent and, therefore, quite distinct from the flagellum-independent process of surface spreading on low agar media as described for some gram-negative bacteria (e.g., see reference 13). We are currently investigating the nature of the agar surface under different conditions in the absence or presence of surfactin by using physical techniques, and these should be revealing about the role of surfactin in the swarming process.

We previously observed the presence of filamentous cells and rafts of cells in swarm communities of the natural isolate, 3610, on the synthetic B medium, forming the multilayered center and the monolayer undersurface of mature dendrites, respectively. These two types of cells were also detected in this study in stunted buds formed by strain 168 in the absence of surfactin on B medium, demonstrating that these morphogenic changes are independent of surfactin secretion. In contrast to B medium, filaments were not observed in swarm communities of strain 3610 or 168 on LB medium, and the alignment of cells into rafts was also largely absent. This finding provides further support for our previous suggestion (9) that these morphogenic changes, unlike those seen in gram-negative bacteria such as P. mirabilis, are not required for the swarming locomotion that we observe. In fact, in this and the previous study, we have observed two distinct types of rapid movement of B. subtilis 3610 cells, detected at distinct stages in development of the community. Thus, mass migration of individual (normal-sized) cells, for example, on B medium precedes aggregation into nascent dendrites, which then assemble backwards toward the center of the plate (9). On the other hand, in this study, we have detected on LB agar the cooperative behavior of up to 50 or more bacteria that form closely associated groups or packs at the leading tip of a dendrite. Such groups push forward rapidly and then halt, followed quickly by the pushing forward of an adjacent pack, giving the overall appearance of a pseudopodial-like movement of the tips of dendrites. Much remains to be discovered about the intercellular signaling mechanisms that control the formation of different structures in the developing swarm community and, in particular, how the overall process is coordinated. Among such overarching controls in response to the physical nature of the terrain, the regulation of surfactin production and the probable maintenance of an optimal level of the biosurfactant ahead of the advancing swarm might also play a major role in the swarming process. This would be consistent with multiple mechanisms known to control the expression of the surfactin peptide synthetases in liquid cultures (17). Future studies will focus on whether surfactin itself plays any signaling role and will address the contribution of the known signaling pathways and quorum-sensing mechanisms involved in surfactin regulation to the coordination of the swarming process.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support for these studies from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the University Paris-Sud (to S.J.S).

We are particularly grateful to Peter Zuber for providing us with the pSV-sfp plasmid. We also thank Edwige Madec and Ania Debicka for help in strain construction and Rivka Rudner for strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anagnostopoulos, C., and J. Spizizen. 1961. Requirements for transformation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 81:741-746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Antelmann, H., S. Engelmann, R. Schmid, A. Sorokin, A. Lapidus, and M. Hecker. 1997. Expression of stress- and starvation-induced dps/pexB homologous gene is controlled by the alternative sigma factor σB in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 179:7251-7256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Jacob, E., O. Schochet, A. Tenenbaum, I. Cohen, A. Czirok, and T. Vicsek. 1994. Generic modelling of cooperative growth patterns in bacterial colonies. Nature 368:46-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connelly, M. B., G. M. Young, and A. Sloma. 2004. Extracellular proteolytic activity plays a central role in swarming motility in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 186:4159-4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cosby, W. M., D. Vollenbroich, O. H. Lee, and P. Zuber. 1998. Altered srf expression in Bacillus subtilis resulting from changes in culture pH is dependent on the Spo0K oligopeptide permease and the ComQX system of extracellular control. J. Bacteriol. 180:1438-1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixit, M., C. S. Murudkar, and K. K. Rao. 2002. epr is transcribed from a final σD promoter and is involved in swarming of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 184:596-599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guerout-Fleury, A. M., N. Frandsen, and P. Stragier. 1996. Plasmids for ectopic integration in Bacillus subtilis. Gene 180:57-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gygi, D., M. M. Rahman, H. C. Lai, R. Carlson, J. Guard-Petter, and C. Hughes. 1995. A cell-surface polysaccharide that facilitates rapid population migration by differentiated swarm cells of Proteus mirabilis. Mol. Microbiol. 17:1167-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Julkowska, D., M. Obuchowski, I. Holland, and S. J. Seror. 2004. Branched swarming patterns on a synthetic medium formed by wild type Bacillus subtilis strain 3610: detection of different cellular morphologies and constellations of cells as the complex architecture develops. Microbiology 150:1839-1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kearns, D. B., and R. Losick. 2003. Swarming motility in undomesticated Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 49:581-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohler, T., L. K. Curty, F. Barja, C. van Delden, and J. C. Pechere. 2000. Swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is dependent on cell-to-cell signaling and requires flagella and pili. J. Bacteriol. 182:5990-5996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsushita, M. 1997. Formation of colony patterns by a bacterial cell population, p. 367-393. In J. S. Shapiro and M. Dworkin (ed.), Bacteria as multicellular organisms. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 13.Matsuyama, T., A. Bhasin, and R. M. Harshey. 1995. Mutational analysis of flagellum-independent surface spreading of Serratia marcescens 274 on a low-agar medium. J. Bacteriol. 177:987-991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendelson, N. H., and B. Salhi. 1996. Patterns of reporter gene expression in the phase diagram of Bacillus subtilis colony forms. J. Bacteriol. 178:1980-1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakano, M. M., N. Corbell, J. Besson, and P. Zuber. 1992. Isolation and characterization of sfp: a gene that functions in the production of the lipopeptide biosurfactant, surfactin, in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 232:313-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohgiwari, M., M. Matsushita, and T. Matsuyama. 1992. Morphological changes in growth phenomena of bacterial colony patterns. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 61:816-822. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quadri, L. E. 2002. Regulation of antimicrobial peptide production by autoinducer-mediated quorum sensing in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 82:133-145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rauprich, P., O. Moller, G. Walter, E. Herting, and B. Robertson. 2000. Influence of modified natural or synthetic surfactant preparations on growth of bacteria causing infections in the neonatal period. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 7:817-822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rudner, R., O. Martsinkevich, W. Leung, and E. D. Jarvis. 1998. Classification and genetic characterization of pattern-forming bacilli. Mol. Microbiol. 27:687-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Senesi, S., E. Ghelardi, F. Celandroni, S. Salvetti, E. Parisio, and A. Galizzi. 2004. Surface-associated flagellum formation and swarming differentiation in Bacillus subtilis are controlled by the ifm locus. J. Bacteriol. 186:1158-1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solomon, J. M., and A. D. Grossman. 1996. Who's competent and when: regulation of natural genetic competence in bacteria. Trends Genet. 12:150-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solomon, J. M., R. Magnuson, A. Srivastava, and A. D. Grossman. 1995. Convergent sensing pathways mediate response to two extracellular competence factors in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 9:547-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toguchi, A., M. Siano, M. Burkart, and R. M. Harshey. 2000. Genetics of swarming motility in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium: critical role for lipopolysaccharide. J. Bacteriol. 182:6308-6321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsuge, K., T. Ano, and M. Shoda. 1996. Isolation of a gene essential for biosynthesis of the lipopeptide antibiotics plipastatin B1 and surfactin in Bacillus subtilis YB8. Arch Microbiol. 165:243-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vagner, V., E. Dervyn, and S. D. Ehrlich. 1998. A vector for systematic gene inactivation in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 144:3097-3104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Velicer, G. J., L. Kroos, and R. E. Lenski. 1998. Loss of social behaviors by Myxococcus xanthus during evolution in an unstructured habitat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:12376-12380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wakita, J., I. Rafols, H. Itoh, T. Matsuyama, and M. Matsushita. 1998. Experimental investigation of the formation of dense-branching morphology-like colonies in bacteria. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 67:3630-3636. [Google Scholar]