Abstract

The genome of RNA viruses folds into 3D structures that include long-range RNA–RNA interactions relevant to control critical steps of the viral cycle. In particular, initiation of translation driven by the IRES element of foot-and-mouth disease virus is stimulated by the 3΄UTR. Here we sought to investigate the RNA local flexibility of the IRES element and the 3΄UTR in living cells. The SHAPE reactivity observed in vivo showed statistically significant differences compared to the free RNA, revealing protected or exposed positions within the IRES and the 3΄UTR. Importantly, the IRES local flexibility was modified in the presence of the 3΄UTR, showing significant protections at residues upstream from the functional start codon. Conversely, presence of the IRES element in cis altered the 3΄UTR local flexibility leading to an overall enhanced reactivity. Unlike the reactivity changes observed in the IRES element, the SHAPE differences of the 3΄UTR were large but not statistically significant, suggesting multiple dynamic RNA interactions. These results were supported by covariation analysis, which predicted IRES-3΄UTR conserved helices in agreement with the protections observed by SHAPE probing. Mutational analysis suggested that disruption of one of these interactions could be compensated by alternative base pairings, providing direct evidences for dynamic long-range interactions between these distant elements of the viral genome.

INTRODUCTION

The genomes of RNA viruses fold into complex structures stabilized by base pairing between nucleotides sometimes located hundreds or even thousands bases apart. These RNA structures, that often involve dynamic RNA–RNA interactions, control key steps of the viral multiplication cycle, including translation, replication, or packaging (1–7), reviewed in (8,9).

RNA molecules encode a layer of information in the form of RNA structure that modulates the gene expression program. Nonetheless, the nature of most RNA structures and the effects of sequence variation on structure are poorly understood. The development of potent methodologies for in vitro and in vivo RNA structure mapping (10–13) aided by in silico prediction algorithms and functional analysis allowed identifying long-range interactions that play key roles in the multiplication cycle of RNA viruses (14–17).

A diverse group of positive-strand RNA viruses have evolved dedicated functional RNA elements able to highjack the translation machinery to selectively direct translation of the viral RNA. In addition, soon after infection these viruses trigger the shutdown of the cellular mRNA translation by modifying the activity of key initiation factors (18), hence impairing translation of the naturally abundant competitor cellular mRNAs. These elements, designated internal ribosome entry sites (IRES), were initially discovered in the genomic RNA of picornaviruses (19,20), but soon later were reported in other viral RNAs including hepatitis C virus (HCV), reviewed in (21). Viral IRES elements are diverse in primary sequence, structural organization, and also differ in the factors required to direct initiation of protein synthesis (22,23). Hence, viral IRES elements can be grouped into different categories, depending on the RNA structure organization and the factors required to promote 48S complex assembly.

Picornavirus IRES elements are grouped into five different types (24). Each type harbors a common RNA structure maintained by evolutionarily conserved nucleotide substitutions. In addition, each type has distinctive requirement of factors. The activity of IRES classified as type I (exemplified by enterovirus) and type II (exemplified by cardiovirus and aphthovirus) depends on the assembly of translation initiation factors (eIFs) and RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) on the IRES modular structure (25), such that each domain consists of one or more stem-loops with conserved motifs that provide the binding site for RBPs and various eIFs, with the exception of eIF4E (26). The RNA structure model of the aphthovirus IRES element, which was generated combining dimethyl sulfate (DMS) and Selective 2΄-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension (SHAPE) reactivity data, accessibility to RNases T1 and T2, and sequence covariation, illustrates the modular organization of this RNA (25).

Beyond eIFs and IRES-transacting factors, the activity of picornavirus and HCV IRES elements is stimulated by their corresponding 3΄UTR sequences (27–29). The HCV genome contains multiple structural domains that mediate long-distance RNA–RNA contacts important for the progress of viral infection. Both, the cis-acting replicating element (CRE) placed within the polymerase NS5B coding region and the 3΄ X-tail region within the 3΄UTR adopt different RNA conformations in the presence of the IRES element. Preservation of these interactions was suggested to play a crucial role in the switch between different steps of the HCV replication cycle (30). The stem-loop 5BSL3.2 within the CRE region forms a high-order structure involved in viral RNA translation and replication (31). Six nucleotides form base pairs between the bulge of the 5BSL3.2 stem-loop and the IIId loop of the IRES, inhibiting translation initiation (32). Conversely, mutations in 5BSL3.2 increased IRES activity supporting the existence of a functional high-order structure in the HCV genome that involves two conserved RNA motifs, one within the IRES and another in the CRE region.

The 3΄UTR sequence of picornavirus genomes consists of 75–100 nt followed by a poly(A) tail. In spite of having a similar nucleotide length, the picornavirus 3΄UTRs lack overall sequence conservation (33). The 3΄UTR is essential for aphthovirus replication (34) although there are controversial results in other picornaviruses (35,36). In the case of the foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) IRES, internal initiation of translation was stimulated by the 3΄UTR (27,37), regardless of the coexpression of the L protease. Therefore, IRES activity was stimulated both in the presence or absence of proteolyzed eIF4G and PABP. Furthermore, a direct dose-dependent RNA–RNA interaction was observed in vitro between transcripts harboring the 3΄UTR (or its predicted stem-loops) and the IRES element (1). However, the nucleotides involved in this long-range interaction remain elusive.

In this work, we sought to investigate the RNA conformation of the IRES element and the 3΄UTR of FMDV in living cells in the context of monocistronic functional transcripts using a strategy that integrates comparative genomic analysis and RNA structure flexibility. To gain information on the residues involved in potential long-range interactions we first mapped the RNA structure of both regions in vivo and in vitro using 2-methylnicotinic acid imidazolide (NAI) (11) to perform SHAPE probing. Second, we determined the modification of the IRES structure induced by the presence of the 3΄UTR in cis, and conversely, the structure of the 3΄UTR in the presence of the IRES region. Finally, we used in silico approaches to analyze sequence conservation, covariation, and base pair formation in both regions, either alone or in a chimeric RNA. Comparison of the in vivo and in vitro SHAPE reactivity data readily showed differences in the protection pattern of both, the IRES element and the 3΄UTR. Furthermore, the presence of the 3΄UTR in cis induced changes in the local flexibility of the IRES structure, and viceversa, the presence of IRES element in cis altered the 3΄UTR reactivity, suggesting long-range interactions between these distant regions of the viral genome. These results were supported by in silico analysis, which predicted conserved helices and covariation between the 3΄UTR and the IRES element specifically including the positions that were protected in the experimental probing data. Subsequent mutational analysis of the predicted IRES-3΄ UTR interactions sustained the dynamic nature of these long-range interactions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Constructs and transcripts

The constructs pIC and pIC-3΄UTR expressing the monocistronic RNAs IRES-luciferase (IL) and IRES-luciferase-3΄UTR (IL3) (Figure 1A) consisting of the FMDV IRES followed by the luciferase coding sequence were described (27). The construct pLuc-3΄UTR, expressing the transcript luciferase-3΄UTR (L3), was generated by deletion of the IRES element in pIC-3΄UTR using SacI. The FMDV 3΄UTR also includes a poly(A58) tract (34).

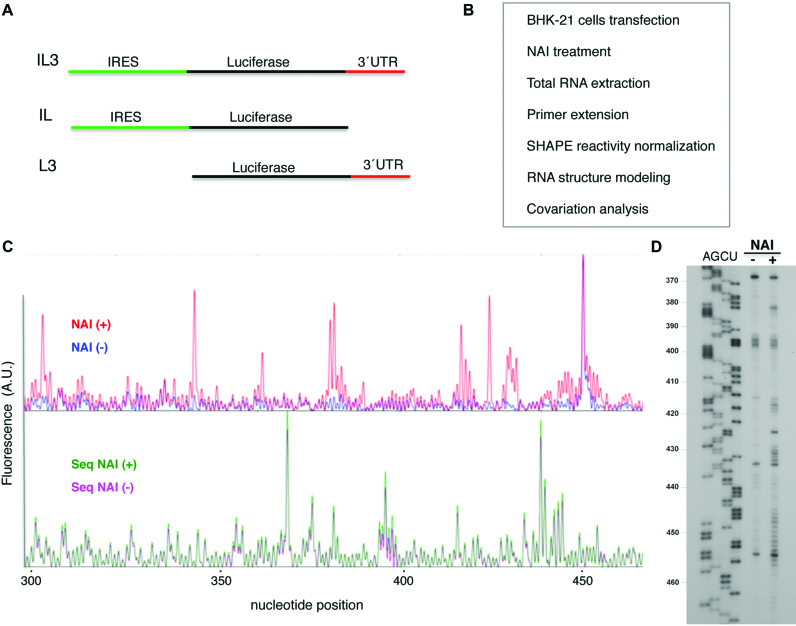

Figure 1.

In-cell mapping of FMDV IRES and 3΄UTR structure. (A) Schematic of the transcripts used to determine RNA structure. (B) Experimental overview. BHK-21 cells were transfected with vectors expressing the transcripts depicted in (A); 20 h post-transfection cells were modified with NAI. Mock-transfected cells were treated as negative control. Following total RNA extraction, reverse transcription (RT) of modified and unmodified RNA generated cDNA products that provided a SHAPE reactivity map. Normalized NAI reactivity was used to generate models of RNA secondary structure. Covariation analysis was performed to identify conserved structural motifs. (C) Representative example of the fluorescence (arbitrary units) obtained using total RNA prepared from treated NAI (+) and untreated NAI (−) cells, fluorescent primers and capillary electrophoresis. For consistency, nucleotide positions are numbered as in previous studies (25). (D) Autoradiogram of a representative example of the RT stops observed using total RNA prepared from cells treated with NAI (+) and untreated (−), determined using radiolabeled primers and denaturing acrylamide-urea gel electrophoresis. AGCU denotes the sequence ladder obtained with same labeled primer. The IRES nucleotide positions are indicated on the left.

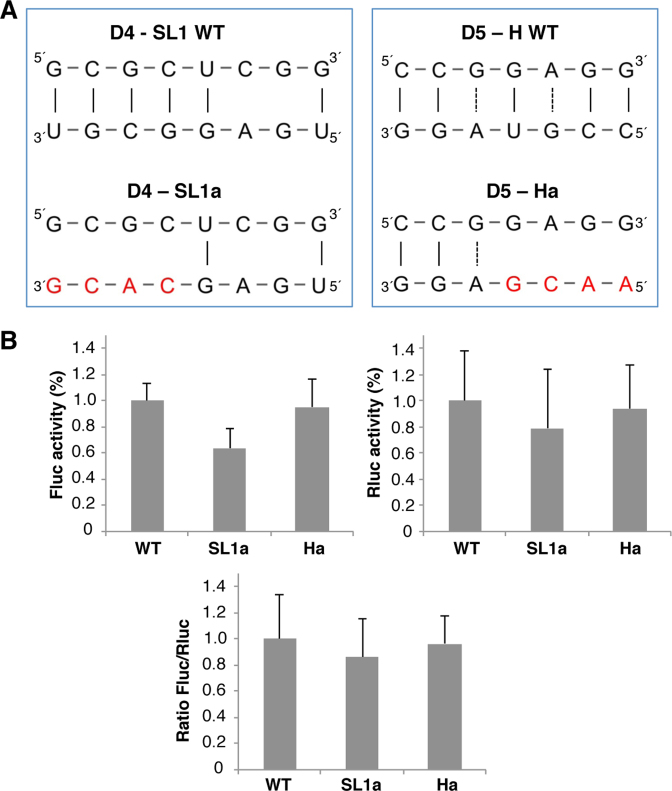

The constructs SL1a and Ha, harboring mutations on the 3΄UTR, were generated using the QuikChange (Agilent) mutagenesis procedure with the pair of primers 5΄-GACAGCCGGGCTCTGAGCACGGCGACACCGTAGGAGTG-3΄, 5΄-CACTCCTACGGTGTCGCCGTGCTCAGAGCCCGGCTGTC-3΄ for SL1a, and 5΄-CCGGGCTCTGAGGCGTGCGACAAACGAGGAGTGAAAATCTC-3΄, 5΄-GAGATTTTCACTCCTCGTTTGTCGCACGCCTCAGAGCCCGG-3΄, for Ha. All plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Macrogen Europe).

Prior to in vitro transcription, plasmid pIC was linearized using SphI while pIC-3΄UTR and pLuc-3΄UTR were linearized by HpaI. RNA synthesis was performed for 2 h at 37°C using T7 RNA polymerase and the linearized DNA template in 40 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM DTT, 0.5 mM rNTPs as described previously (38). DNA template was eliminated by RQ1 DNase treatment (Promega), followed by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation. Synthesis of full-length products and absence of contaminating DNA template was verified by gel electrophoresis.

IRES activity assays

Plasmids pIC-3΄UTR wild type or the mutants SL1a and Ha, expressing a monocistronic RNA carrying the wild type or the mutant 3΄UTR sequences downstream of the luciferase reporter gene were assayed in BHK-21 cells. In all cases, a plasmid encoding Renilla luciferase (39) was added to the DNA transfection mix as a control of the transfection efficiency. Transfection of 90% confluent monolayers was carried out using cationic liposomes 1 h after infection with the Vaccinia virus VT7F-3 expressing T7 RNA polymerase (40). This assay excludes the presence of cryptic promoters since the transfected plasmid is transcribed in the cell cytoplasm by the T7 RNA polymerase. Extracts from 105 cells were prepared 20 h after transfection in 100 μl of 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.8, 120 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activity were measured using the dual luciferase reporter assay (Promega). IRES activity was quantified as the expression of Firefly luciferase normalized to the amount of protein in the lysate, determined using the Bradford assay. Each experiment was carried out in triplicate wells and repeated independently at least three times. Values represent the mean ± SD. The ratio of Firefly luciferase activity (IRES-dependent translation) normalized to Renilla luciferase (cap-dependent translation) induced by the presence of mutations on the 3΄-UTR was analyzed by the unpaired two-sided Student's t-test; differences were considered significant when P < 0.01.

Synthesis of NAI

NAI (2-methylnicotinic acid imidazolide) was produced as 1:1 mixture with imidazole in DMSO stock solution as described (11). Briefly, 137 mg (1 mmol) of 2-methylnicotinic acid was dissolved in 0.5 ml anhydrous DMSO. Then, a solution of 162 mg (1 mmol) 1,1΄-carbonyldiimidazole in 0.5 ml anhydrous DMSO, was added drop wise over 5 min. The resulting solution was stirred at room temperature until gas evolution was complete and then stirred at room temperature for 1h. The stock solution (1 M) is stable for 10–12 months stored at −80°C.

NAI treatment of transfected cells

BHK-21 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 7.5% fetal calf serum in 100 mm dishes. Confluent monolayers (∼10 × 106 cells) were infected with VTF-3 virus that expresses the T7 RNA polymerase. After 1 h of virus adsorption, cells were transfected using cationic lipids and 8 μg per dish of the appropriate plasmid DNA (41). Fetal calf serum was added to the monolayer 4 h later (7.5% final concentration).

For RNA structure probing, cell monolayers were washed twice with cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) 20 h post-transfection, scraped into PBS, pelleted and resuspended in 100 μl of PBS, prior to addition of NAI (20 mM) (+) or DMSO (2%) (−). The optimal conditions (concentration and time) for NAI treatment was determined by titration, as described (11). Samples were placed at 37°C for 10 min, then 1 ml of cold PBS was added and the cells were pelleted again. For RNA purification, 1 ml of TRIZOL (Ambion) was added to the pellet, and vortexed prior to add 200 μl of chloroform. Total RNA was precipitated following the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA was resuspended in RNase-free water to a concentration of ∼2.5–3 μg/μl in 30 μl final volume.

NAI treatment of RNA in vitro

Prior to NAI treatment, in vitro synthesized RNA (2 pmol) was folded by heating at 95°C for 2 min, snap cooling on ice for 2 min and subsequently incubated for 20 min at 37°C in SHAPE buffer (100 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 6 mM MgCl2 and 100 mM NaCl). Following addition of NAI (20 mM) (treated RNA) or DMSO (untreated RNA), the samples (20 μl final volume) were incubated 2 min at 37°C. RNA was then precipitated and resuspended in 50 μl of TE 0.5×.

Primer Extension of in vivo modified RNA

For primer extension, total RNA (20 μg) was heated at 95°C for 2 min, snap cooling on ice for 2 min, prior to add the fluorescent primer 5΄-Alexa Fluor 488-TAGCCTTATGCAGTTGCTCTCC (0.1 μM). Primer extension reactions were conducted in a final volume of 20 μl containing reverse transcriptase (RT) buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.3, 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 7.5 mM DTT), 10 U RNase OUT (Invitrogen), 1 mM each dNTP, and 60 U of Superscript III RT (Invitrogen). Reverse transcriptions were performed during 1 h at 52°C. After alkaline hydrolysis of the RNA template (0.1 M NaOH at 70°C for 15 min) and precipitation (42), primer extension products were resolved by capillary electrophoresis (Figure 1B). The 5΄-NED-TAGCCTTATGCAGTTGCTCTCC primer was used for the sequencing ladder, using 2.5 pmol of untreated RNA in the presence of 0.1 mM ddCTP, 30 min at 52°C RT reaction. The primer extension products, NAI(+) or NAI(−), were resolved with a sequence ladder in two capillaries (Figure 1C).

5΄-end 32P-labeled primers were annealed to 20 μg of total RNA prepared from transfected cells, by incubation at 95°C for 3 min followed by a snap cooling on ice for 2 min. To cover the entire FMDV IRES sequence 4 primers were used: 5΄-GGCCTTTCTTTATGTTTTTGGCG, 5΄-GGAATGGGATCCTCGAGCTCAGGGTC, 5΄-CATCCTTAGCCTGTCACC, 5΄-CCGTCATGCTCCGCTAC. The primer 5΄-CTAAGAATTTTGTCATTGCTGG was used for 3΄UTR-poly(A58) RNA reactions. cDNAs products were precipitated and the dry pellets were resuspended in 10 μl of H2O with 4 μl of 90% formamide, 1 mM EDTA pH 8, 0.1% xilencianol, 0.1% bromophenol loading buffer. Denatured cDNA products were fractionated in 6% acrylamide 7 M urea gels (Figure 1D), in parallel to a sequence ladder obtained with the same radiolabelled primer using Thermo Sequenase™ Cycle Sequencing Kit (USB).

Primer extension of in vitro modified RNA

For primer extension, equal amounts of NAI-treated and untreated RNAs (10 μl, about 0.4 pmol) were incubated with 0.5 μl of the appropriate antisense 5΄-end 32P-labeled primer at 65°C for 5 min, 35°C for 5 min and then chilled at 4°C for 2 min. Primer extension reactions were conducted as described (43).

SHAPE reactivity data analysis

SHAPE electropherograms were analyzed using QuSHAPE software (44). The reactivity values obtained for each untreated RNA (DMSO) were subtracted from the corresponding treated RNA to obtain the net reactivity for each nucleotide. Quantitative SHAPE reactivity for individual datasets were normalized to a scale spanning 0 to 2.5 in which 0 indicates an unreactive nucleotide and the average intensity at highly reactive nucleotides is set to 1.5. Data from at least 3 independent assays were used to calculate the mean (±SD) SHAPE reactivity.

For SHAPE data processing obtained with P32-labeled primers, the intensity of RT-stops was quantified as described (45). The reactivity values observed in the untreated RNA were subtracted from all the NAI-treated RNAs. The normalization factor for each dataset was determined by excluding the most-reactive 2% of peak intensities, followed by calculating the average for the next 8% of peak intensities. All reactivity values were normalized to this average value to generate the SHAPE reactivity profiles. Quantitative SHAPE reactivity for individual data sets was normalized to a scale spanning 0 to 2.5. Data are available upon request. Treatment of the L3 transcript with NAI or NMIA yielded a similar SHAPE reactivity pattern (Supplementary Figure S1). The secondary structure models obtained imposing the reactivity values of NMIA and NAI in RNAstructure software (44) resulted in similar models (Supplementary Figure S1).

The statistical significance of the SHAPE reactivity data obtained for the indicated constructs under different conditions was determined by the unpaired two-tail Student's t-test. Only nucleotide positions with absolute difference ≥0.2 arbitrary units and P-value <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The secondary RNA structure models were generated using RNAstructure software (46) imposing SHAPE reactivity values as pseudofree energy change constraints along with nearest neighbor thermodynamic parameters. The predicted structure corresponding to the lowest minimal free energy (MFE) energy was used to depict the RNA structure model. RNA structures were visualized with VARNA (47).

Nucleotide sequence analysis

The alignment of sixty-six unique 3΄ UTR sequences of FMDV field isolates deposited in GenBank, representative of all serotypes, was performed using CLUSTALX software with default parameters (http://www.clustal.org). Sequence logos (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu) were generated from the multiple-sequence alignment of the RNA sequences. The overall height of each stack indicates the sequence conservation at that position (measured in bits), and the height of symbols within the stack reflects the relative frequency of the corresponding nucleic acid at that position. Base pair conservation and covariation range were estimated using R-CHIE (48) imposing the consensus secondary structure predicted by RNAaliFold (49) from the sequence alignment. Covariation values were estimated by computing canonical base pairs and compensatory mutations as positive values, and incompatible base pairs as negative values.

TRANSAT method (50) was used to detect evolutionary conserved helices and to estimate their statistical significance from the sequence alignments of the sixty six unique sequences of the FMDV 3΄ UTR, their corresponding IRES regions, and the chimeric sequences resulting after fusing the individual IRES domains to the 3΄ UTR sequence.

RESULTS

In-cell RNA structure probing of the FMDV IRES reveals significant differences with in vitro data

Previous work analyzed the secondary RNA structure of the FMDV IRES using SHAPE reagents in vitro, either with free RNA or RNA incubated with IRES-binding factors (43,51). However, the RNA conformation of this element in living cells remained elusive. Thus, to gain information about the IRES organization in vivo we made use of the NAI reagent (11) to treat cells that were previously transfected with a functional construct expressing the IRES-luciferase (IL) transcript. In this RNA, the FMDV IRES promotes internal initiation of translation of the luciferase reporter (Figure 1A). Mock-transfected cells were treated in parallel, as a negative control. Optimal conditions for in vivo RNA probing were obtained by treating the cells with NAI (20 mM) for 10 minutes, 24 hours post-transfection. Following total RNA purification, primer extension was conducted with specific 5΄-labeled primers (either Alexa Fluor-488 or 32P), using in parallel RNA purified from treated and untreated cells (Figure 1B). Representative examples of the SHAPE probing results obtained in vivo using either fluorescent primers and capillary electrophoresis or 32P-labeled primers and urea-acrylamide sequencing gels, respectively, are shown in Figure 1C, D.

The normalized in-cell NAI reactivity data obtained for the IL construct is shown in Figure 2A (top panel). The same reagent was used to treat in vitro naked IL RNA (Figure 2A, bottom panel). Comparison of the SHAPE reactivity obtained in living cells with free RNA treated in vitro revealed protections at specific positions within domains 3 and 4. Conversely, enhanced reactivity was observed on several positions within domains 4 and 5. Specifically, the differences between the SHAPE reactivity data observed in living cells and that observed using free RNA in vitro showed significant protections (absolute SHAPE difference > 0.2; P < 0.05) at positions 144, 167–169, 233–238, 361, 380–382 and 419 (Figure 2B, blue bars). In contrast, significant increased reactivity was observed at positions 303, 305, 343 and 415–450 (Figure 2B, red bars).

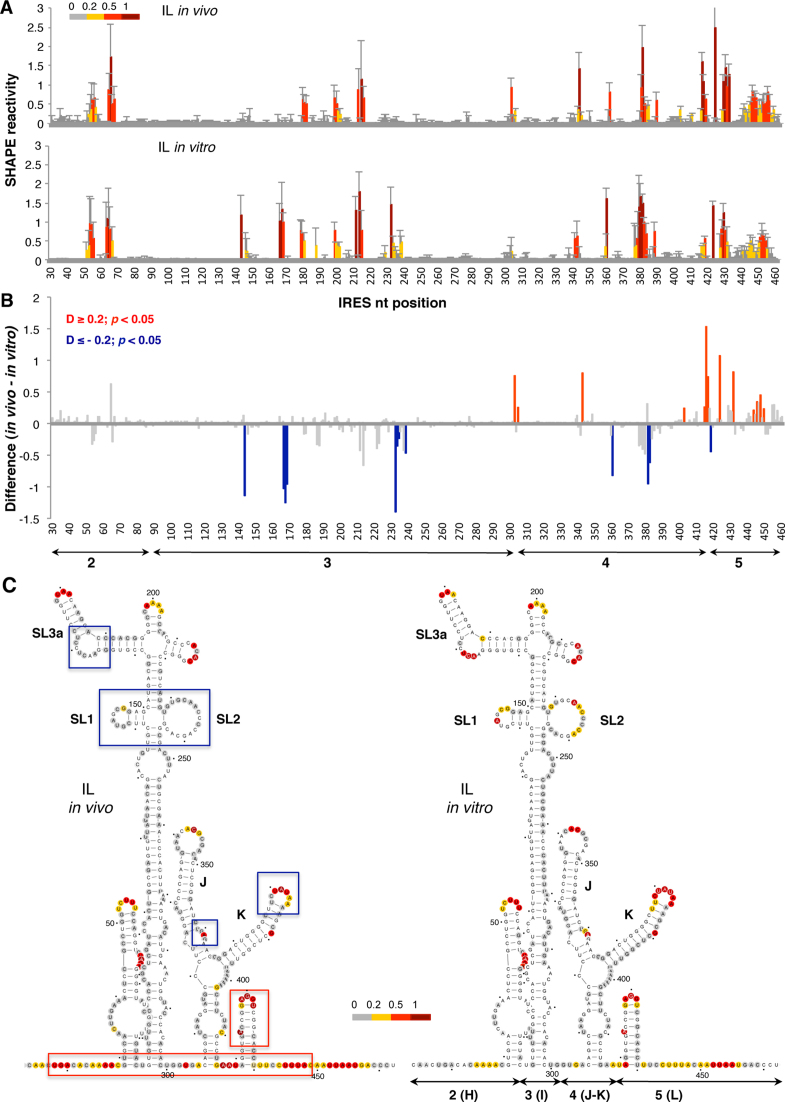

Figure 2.

Comparison of the local flexibility of the IRES region in transfected cells with free RNA. (A) SHAPE IRES reactivity towards NAI in cells expressing a functional monocistronic IRES-luciferase (IL) transcript. Normalized IRES reactivity determined in vivo and in vitro as a function of the nucleotide position. RNA reactivity is colored according to the scale shown on the left. Values correspond to the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. (B) Significant SHAPE differences between in vivo and in vitro IRES reactivity. Red or blue bars depict nucleotides with P-values <0.05 and absolute SHAPE reactivity differences (D) higher or lower than 0.2, respectively. Gray bars depict differences with P-values >0.05 and/or absolute differences <0.2. Arrows denote the location of the IRES structural domains 2, 3, 4 and 5, also designated H, I, J–K or L. (C) RNA secondary structure models showing NAI reactive positions determined in vivo or in vitro. Red and blue boxes depict enhanced or protected, respectively, regions observed in living cells relative to free RNA. Nucleotides are numbered every 50 nts; a dot marks every 10 nts. SL1, SL2 and SL3a denotes subdomains of domain 3; J and K are subdomains of domain 4 (25). For completeness, domains 2(H), 3(I) 4(J–K) and 5(L) are also marked below the secondary structure (right panel).

The RNA secondary structure models depicting NAI reactivity in vivo and in vitro are shown in Figure 2C. The reactivity observed for the IRES element in living cells compared to the reactivity of the free RNA in vitro revealed protection of nucleotides residing in domain 3, namely SL1, SL2 (bearing the C-rich loop), and the hexaloop of stem-loop 3A, and in domain 4, specifically the internal bulge 360 and the loop 380 within stem–loops J–K (blue boxes in Figure 2C). In contrast, the spacer regions between domains 2, 3, 4 and 5, and the hairpin of domain 5 showed enhanced reactivity (red boxes in Figure 2C). The observed protections in domain 3 are coincident with the binding-site of the protein PCBP2, as well as with local flexibility areas observed in vitro within this domain (52–55). The enhanced reactivity noticed at positions 410–450 could be interpreted as a higher flexibility of the initiation zone. Interestingly, the flexibility of this zone has been reported as a general feature of cellular RNAs in vivo (56). The accessibility of several positions near the initiation codon suggests that a higher flexibility of this IRES region accompanies internal initiation of translation in the cell cytoplasm.

RNA structural organization of the 3΄UTR in living cells

The FMDV 3΄UTR sequence consists of about 90 nts followed by a poly(A) tail (34). Previous data reported that the 3΄UTR stimulates IRES activity both in the viral RNA (37) or when placed at the 3΄ position of a reporter gene (27). In addition, direct RNA–RNA interactions between these distant regions of the viral genome have been shown in vitro (1). Notably, while the 3΄UTR transcript showed an intense binding to the IRES element irrespectively of the presence of the poly(A) tail, subdivision of the IRES element in domains severely decreased the interaction with the 3΄UTR. Nonetheless, a weak but positive interaction was detected between the 3΄UTR and the IRES transcript harboring domains 4–5 (1). These results suggested that the entire IRES would offer the overall 3D conformation capable of interacting with the 3΄UTR. Yet, the precise location of these sites remained to be elucidated.

To tackle this question, we first probed the RNA structure of the 3΄UTR in living cells using the NAI reagent. The data obtained revealed high reactivity at positions 62–70, with weak attacks to residues 9–12 and 80–89 (Figure 3A, top panel). Nucleotide positions within the 3΄UTR are numbered taking as 1 the first nt after the stop codon of the coding sequence. Analysis of the reactivity of the free RNA in vitro showed a different pattern, with high reactivity at positions 6–19 and 81–89, while nts 62–70 were moderately reactive (Figure 3A, bottom panel). These results revealed important differences between the accessibility of this RNA to NAI in vivo and in vitro. Statistical analysis of the differences (absolute SHAPE difference > 0.2, P < 0.05) between the RNA probed under different conditions indicated significant protections at residues 8–16 and 86–87 in vivo, whereas residues 67–68 displayed increased reactivity (Figure 3B).

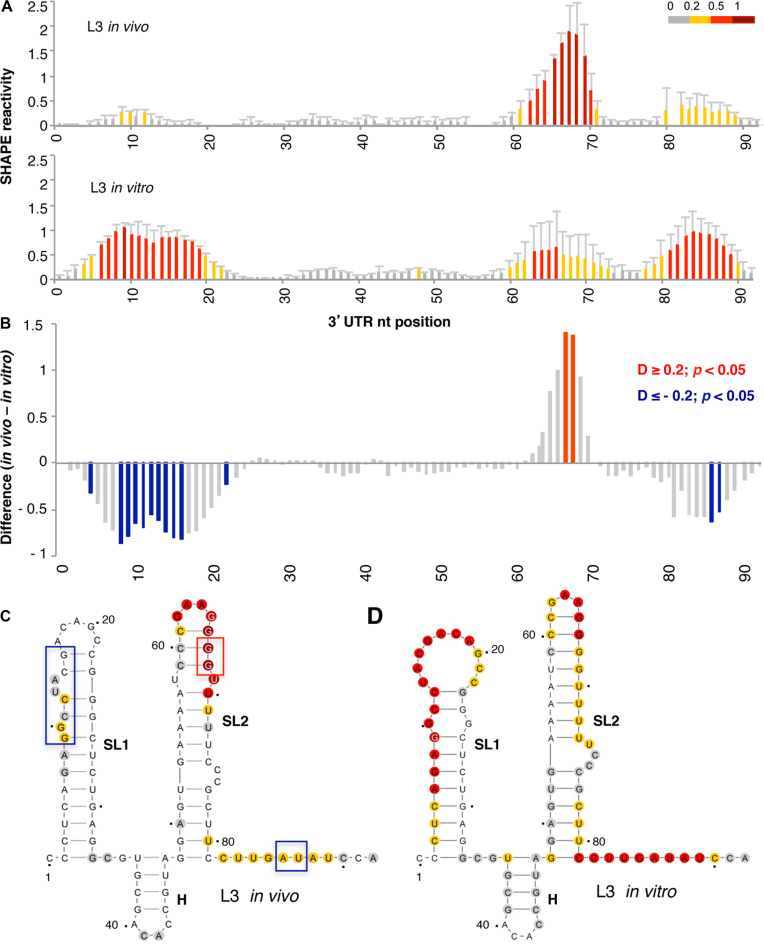

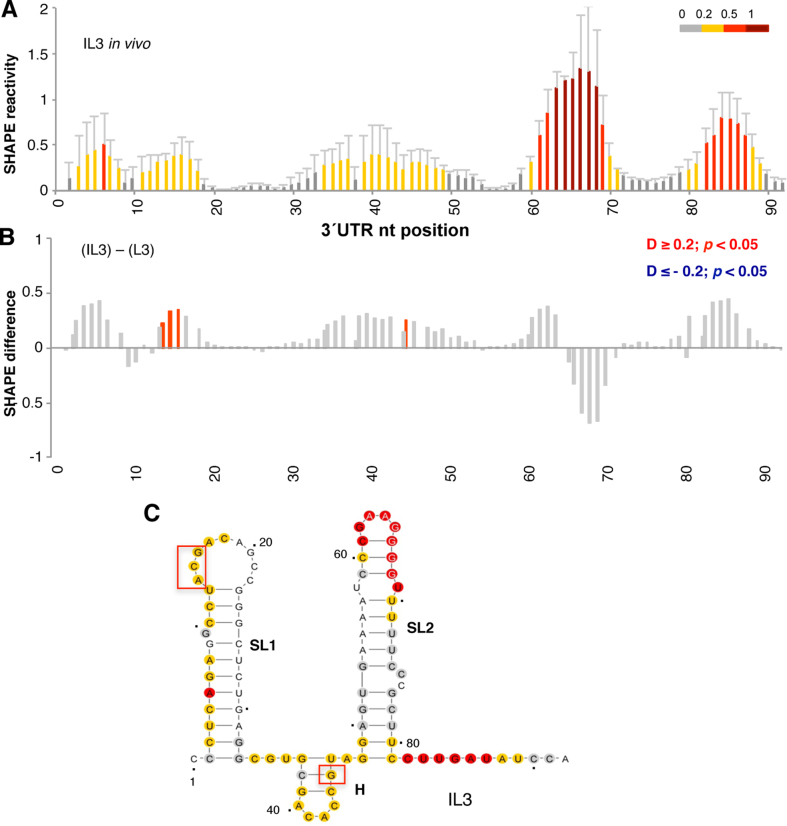

Figure 3.

Analysis of the 3΄UTR SHAPE reactivity in transfected cells expressing a functional monocistronic transcript. (A) Normalized 3΄UTR reactivity determined in vivo and in vitro as a function of the nucleotide position. RNA reactivity toward NAI is colored according to the scale shown on the right. Values correspond to the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. (B) Significant differences between in vivo and in vitro SHAPE reactivity. Red or blue bars depict nucleotides with P < 0.05 and absolute SHAPE reactivity differences (D) higher or lower than 0.2, respectively. Gray bars depict non-statistically significant differences. RNA secondary structure of the 3΄UTR generated imposing the reactivity towards NAI in vivo (C) and in vitro (D). Red and blue boxes depict enhanced or protected regions, respectively, observed in living cells relative to free RNA. Nucleotide numbers are marked every 20 nts; a dot marks every 10 nts, taking as 1 the first nt after the stop codon of the FMDV coding sequence. The location of stem-loops SL1, SL2 and H generated imposing SHAPE reactivity on RNAstructure software is indicated. The minimal free energy predicted structure is depicted in each case.

Next, modeling of the 3΄UTR secondary structure imposing SHAPE reactivity yielded a three stem-loop structure, designated SL1, SL2, and H in the current study (Figure 3C). Note that the short hairpin (H) was predicted as a bulge in earlier studies (1,57). The secondary structure of this region differed depending on whether the RNA was treated in living cells (hence, in the presence of cytoplasmic RNA ligands) or in vitro (free RNA in solution) (Figure 3D). Main differences were observed in the reactivity of nts located in SL1 and SL2, suggesting that factors present in the cell cytoplasm greatly influence the RNA conformation of this region. In particular, we noticed that SL1 was protected when the transcript was treated in the cell cytoplasm (Figure 3C), while the free RNA displayed higher reactivity. On the other hand, the apical stem of SL2 exhibited higher reactivity in vivo than in vitro. Finally, the most 3΄end nts of the 3΄UTR were moderately reactive in vivo, in contrast to results observed in the free RNA.

The RNA structure software penalizes base pairs with high reactivity located in stems (46). Yet, in spite of imposing SHAPE reactivity values to model the RNA structure, we noticed that the reactivity of nucleotides located in the apical loop of SL2 was lower than others located in the apical stem (see Figure 3C). This observation has been reported before for RNA transcriptional regulators (58). Nevertheless, it was surprising for us since it does not occur in the IRES element under any of the conditions analyzed here or in previous works (43). Although this feature may be related to the conformational plasticity of SL2 (discussed below), presumably related to the role of the 3΄UTR in translational control, further work is needed to understand the functional significance of this structural observation.

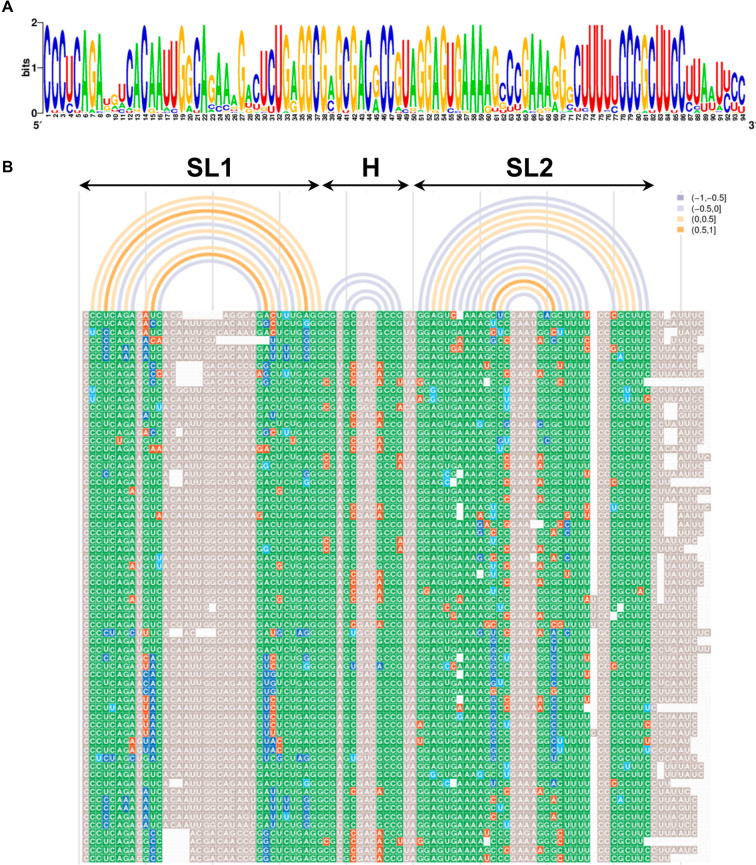

Covariation analysis supports the organization of the 3΄UTR into three stem-loops

The differences of NAI reactivity obtained in-cell and in vitro prompted us to test whether any of these structural features were supported by sequence covariation, a powerful method to identify functionally relevant structural elements in RNAs (38,59,60). Analysis of the sequence variability of the 3΄UTR among 66 unique sequences of FMDV field isolates indicated a high degree of sequence conservation (Figure 4A). However, certain positions tolerated substitutions. Next, the conservation of the consensus RNA structure predicted without probing or folding constraints by RNAaliFold (49) from the 3΄UTR sequence alignment (Figure 4B, arcs plotted above the sequence alignment) revealed similarities with the RNA structure model generated for the 3΄UTR imposing SHAPE reactivity values obtained in vitro (Figure 3D). Furthermore, base pair formation visualized using R-CHIE (48) unveiled covariant nucleotides (ranging between 0.5–1) in SL1 and SL2. Note that although three stem-loops were predicted in both cases, there are slight differences in the number of base pairs of the helices or the location of internal bulges in SL1 and SL2. Base pairs involved in SL1 and SL2 helices included a high degree of invariant plus covariant base pairs (green and blue nts in Figure 4B). In addition, most of the non-canonical base pairs (orange nts in Figure 4B) were located at the edge of helices, reinforcing the evolutionary conservation of these stem-loops. These data suggest that the structural organization of the 3΄UTR is phylogeneticaly conserved, further evidencing the functional relevance of this region.

Figure 4.

Conserved RNA structural features of the 3΄UTR. (A). The pattern of nucleotide conservation (measured in bits) of the FMDV 3΄UTR is represented by a sequence logo obtained from the alignment of 66 unique sequences of FMDV field isolates deposited in GenBank. (B). Covariation analysis of the 3΄UTR RNA structure. The consensus minimum free energy (MFE) secondary structure predicted by RNAalifold (49) from the multiple sequence alignment was used to visualize the covariant positions within the 3΄UTR by R-CHIE (48). Nucleotides are colored by the degree of conservation, green indicates the most frequent canonical base pair; dark blue is used for double sided-mutations and light blue for single-sided mutations); red depicts non-canonical base pairs; grey indicates unpaired nts, and white is used for gaps. Each arc depicts a base pair of the RNA structure. Covariation range is indicated by the color of the arc.

The 3΄UTR induces specific protections on the IRES element immediately upstream of the start codon in living cells

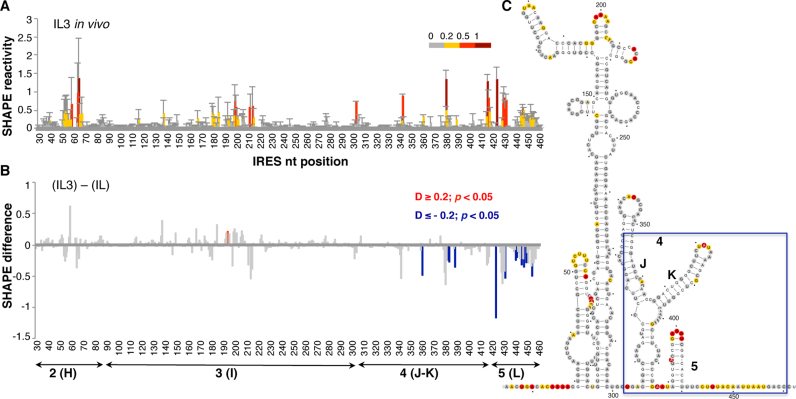

The RNA structure changes observed in vivo on the IRES and 3΄UTR regions individually prompted us to analyze the organization of both RNA regions expressed in cis, using a monocistronic IRES-luciferase-3΄UTR (IL3) transcript in which translation of luciferase is directed by the FMDV IRES. To this end, BHK-21 cells were transfected following the same procedure used for the IL construct. Comparison of the IRES NAI-reactive positions in the IL3 transcript (Figure 5A) to the reactivity of the IL transcript (lacking the 3΄UTR sequence) (see Figure 2A) indicated that differences leading to statistically significant protections accumulated on nts 361, 382, 383, 389 (domain 4) and 424, 431, 441–454 (domain 5) (Figure 5B and C). A modest increase of reactivity was observed in domains 2 and 3, although the differences were not statistically significant. The protections observed in the region immediately upstream of the initiator AUG in living cells, also tended to accumulate over the 3΄ end of the IRES element in vitro (Supplementary Figure S2). Thus, the presence of the 3΄UTR in the IL3 transcript induced changes in the 3D structure of the IRES element, coincident with a stimulation of internal initiation of translation (27).

Figure 5.

Conformational changes in the IRES element in the presence of 3΄UTR. (A) SHAPE reactivity towards NAI in cells expressing the monocistronic IL3 transcript (top). Normalized IRES reactivity determined in vivo as a function of the nucleotide position. RNA reactivity is colored according to the scale shown on the right. Values correspond to the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. (B) Significant SHAPE differences within the IRES region in vivo between the transcript IL3 and IL (bottom). Red or blue bars depict nucleotides with P-values <0.05 and absolute SHAPE reactivity differences (D) higher or lower than 0.2, respectively. Grey bars depict non-statistically significant differences. (C) IRES secondary structure showing NAI reactivity, a blue box denotes protected positions on domains 4 and 5 on IL3 relative to the IL RNA.

Next, in the inverse experiment, we investigated the consequence on the 3΄UTR structure of harboring the IRES element on the same transcript. We found that the presence of the IRES element in the monocistronic RNA affects the local flexibility of the 3΄UTR (Figure 6A and B). The nucleotides that showed enhanced reactivity in the presence of the IRES are widespread all along the 3΄UTR (Figure 6C). Notably, strong protections were noticed at positions 65–70 within SL2, but in contrast to the IRES region, the reactivity changes leading to these protections were not statistically significant (Figure 6B). This result suggested the possibility that multiple dynamic interactions could be established between the 3΄UTR and the IRES element.

Figure 6.

Conformational changes in the 3΄UTR in the presence of the IRES element. (A) SHAPE reactivity towards NAI in cells expressing the monocistronic IL3 transcript. Normalized 3΄UTR reactivity determined in vivo as a function of the nucleotide position. RNA reactivity is colored according to the scale shown on the right. Values correspond to the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. (B) Significant SHAPE differences within the 3΄UTR in vivo between the transcript IL3 and L3. Red bars depict nucleotides with P-values < 0.05 and absolute SHAPE reactivity differences (D) higher or lower than 0.2, respectively. Grey bars depict non-statistically significant differences. (C) 3΄UTR RNA secondary structure showing NAI reactivity, red boxes denote statistically significant exposed nts on IL3 relative to the L3 RNA.

In silico studies support dynamic interactions between the 3΄UTR and the IRES element

To gain information about base pairs formation between the IRES element and the 3΄UTR we used TRANSAT software to predict statistically significant conserved helices involving at least four consecutive residues (50). Remarkably, the predicted conserved helices (Figure 7A) faithfully reproduce the RNA secondary structure model of the IRES element modeled according to SHAPE probing (see Figure 2C). In particular, the apical stem-loop of domain 2 (nts 41–72), most of the stem-loops of domain 3 including the basal helix (nts 86–299) and the stem-loop 3A (nts 159–194), the stem-loop K of domain 4 (nts 367–397) and the hairpin of domain 5 (nts 419–440) were accurately predicted (P < 6.17 × 10−5). The stem–loop corresponding to subdomain J of domain 4 was predicted with a P-value = 1.23 × 10−3, but it does not appear in Figure 7A since this is above the threshold of the conserved helices drawn for the entire IRES element.

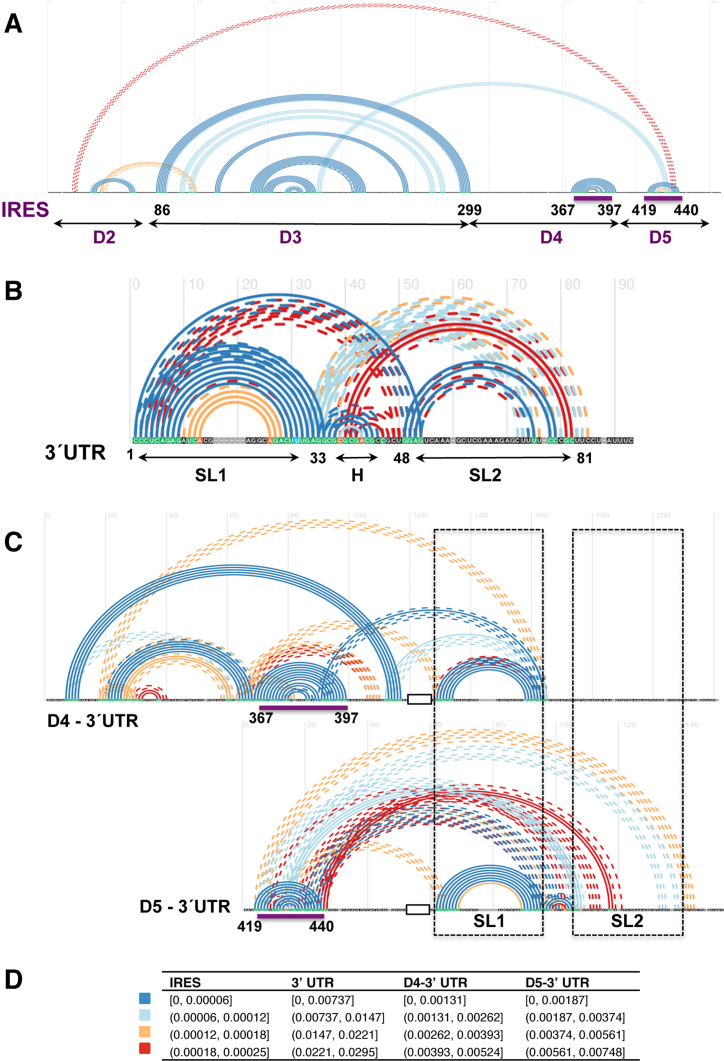

Figure 7.

In silico analysis of conserved helices between the IRES element and the 3΄UTR. Conserved helices predicted by TRANSAT for the sequence alignment of the IRES region alone (A), the 3΄UTR alone (B) and the chimeras D4-3΄UTR and D5-3΄UTR (C) for the P-value thresholds indicated in the legend (D). Arcs connect base pairs, colored according to their P-value range estimated by TRANSAT. Filled line arcs depict helices predicted with high reliability, broken line arcs depict mutually exclusive helices. The structural domains of the IRES and the stem–loops of the 3΄UTR are indicated on the x-axis, together with the nt position flanking each domain. Purple lines denote the positions of the IRES predicted to base pair with SL2; dashed black boxes depict the position of 3΄UTR SL1 and SL2 on the RNA chimeras. A black empty box depicts the A10 tract fusing the IRES domains with the 3΄UTR sequence.

TRANSAT also predicted three additional interdomain statistically significant conserved helices that may contribute to the IRES 3D structure, in accordance to previously reported RNA–RNA interactions (61). The helix predicted with higher significance (P = 6.6 × 10−5) includes bases belonging to domain 5 and SL3b of domain 3, while helices predicted between domains 2 and 3, and domain 5 and beginning of domain 2, could represent alternative base pairing within the IRES region.

A similar analysis of the 3΄UTR revealed that base pairs leading to three stem-loops (SL1, SL2 and H) were also predicted with high confidence (Figure 7B). In particular, SL1 was predicted with a significant P-value (8.0 × 10−5). In contrast, SL2 showed a greater capacity to establish mutually exclusive base pairs (dashed lines in Figure 7B) than SL1, leading to a larger conformational plasticity.

Next, in order to predict base pairs between the IRES element and the 3΄UTR, we designed in silico chimeric RNAs taking into account the protections observed in the RNA probing experimental data. Thus, we fused sequences bearing the individual domains 4 and 5 of the IRES element to the 3΄UTR (D4-3΄UTR or D5-3΄UTR) by a tract of 10 adenines (Figure 7C). Comparison of the predictions obtained for the RNA chimeras against the IRES element or the 3΄UTR individually identified statistically significant helices (P < 7.48 × 10−3) between the IRES and nucleotides placed in SL2 or H of the 3΄UTR, while SL1 remained mostly unaffected (Figure 7C). Specifically, analysis of base pair formation between domain 4 and the 3΄UTR chimera (D4-3΄UTR) indicated that SL1 was maintained (P = 8.97 × 10−5), while SL2 and H were predicted with lower probability (hence, they are not shown in Figure 7C). Furthermore, nts 29–35 placed at SL1-H border were predicted to base pair with subdomain K around position 389 (P = 2.87 × 10−4) (Figure 7C). Base pairing leading to subdomain J in the presence of the 3΄UTR was predicted with a P-value = 1.89 × 10−3, similar to the data obtained for the sole IRES element.

Subsequent analysis of the D5-3΄UTR chimera indicated that SL1 and H remained as in the case of the 3΄UTR alone (P-values 1.09 × 10−4 and 1.10 × 10−3, respectively). Importantly, base pairings between SL2 and the loop of domain 5 hairpin (P = 2.64 × 10−3) and the pyrimidine tract (nts 439–441) of domain 5 (P = 5.83 × 10−3) were also predicted with high confidence. Moreover, while the hairpin of domain 5 remained as in the IRES element alone, SL2 was predicted in the chimera D5-3΄UTR with lower probability (P = 5.29 × 10−2) than in the 3΄UTR alone.

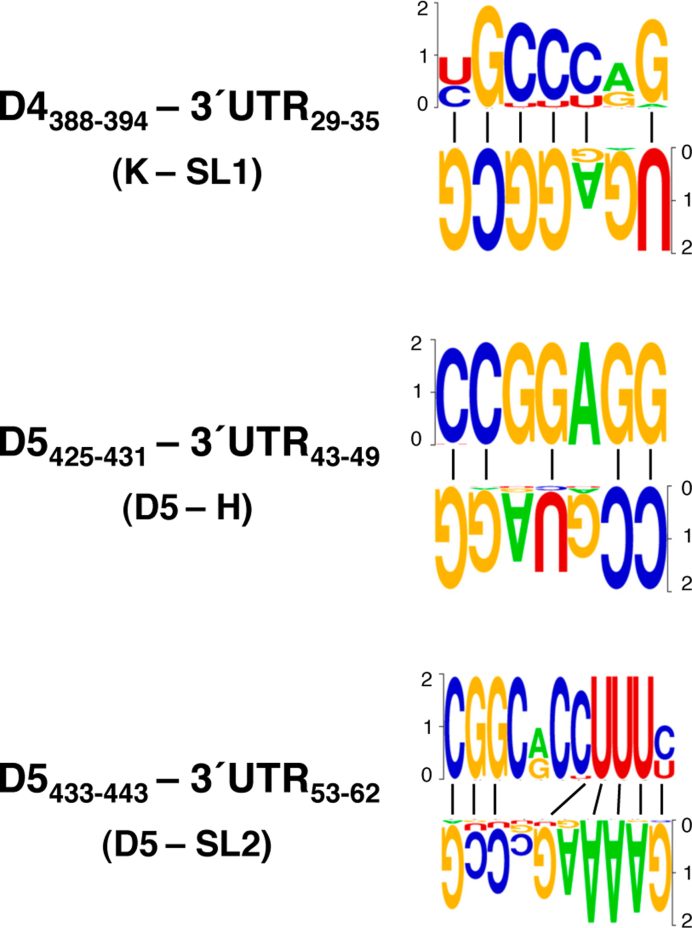

Considering the significant P-values calculated for each of these interactions, we attempted to analyze the covariation between the residues located in the interacting regions mentioned above by R-CHIE. Remarkably, covariation was observed between domain 4 of the IRES and the SL1 hairpin of the 3΄UTR (Supplementary Figure S3), as well as between two different nucleotide stretches of domain 5 of the IRES and H or SL2 of the 3΄UTR (Supplementary Figure S4). The base pairs inferred from the covariation analysis are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Covariant bases involved in long-range interactions between the IRES and the 3΄UTR. The pattern of nucleotide conservation (measured in bits) of the IRES and the 3΄UTR predicted to interact by TRANSAT is represented by a sequence logo obtained from the sequence alignment of FMDV field isolates. The IRES domains (4 or 5) and the 3΄UTR stem-loops (SL1, H and SL2) and the nucleotide positions for each interacting region are indicated. A dash denotes canonical base pairs.

Taken together, our data strongly suggest that the 3΄UTR of the FMDV RNA could establish multiple, yet conformationally dynamic, base pairs with nts placed on distinct domains of the IRES element. These data are in agreement with earlier observations in which the 3΄UTR formed stable RNA–RNA retarded complexes with the IRES element, and although to a lower extent, with a transcript bearing domains 4 and 5 (1). Further supporting the dynamic nature of the distant interactions, the difference in the SHAPE reactivity values obtained for the free RNA (in vitro) containing the IRES element and the 3΄UTR compared to the IRES alone showed statistically significant protections in nts 389, 419, 445 and 451 on the IRES element (Supplementary Figure S2), while SHAPE differences in the 3΄UTR, although higher than 0.2, were statistically significant only in two positions, 84–85 (Supplementary Figure S5A and B).

Functional analysis of the 3΄UTR sequences predicted to base pair with the IRES element

To analyze the influence of the 3΄UTR on IRES-dependent translation, we generated two 3΄ UTR mutants aimed to disrupt the predicted IRES-3΄UTR interactions. The SL1a mutant, in which 3΄ UTR nts G33CGU36, that would base pair with domain 4 (nts 387 to 390), were substituted by C33ACG36; and the Ha mutant, in which nts C43CGU46 were substituted by A43ACG46 to disrupt the interaction with domain 5 (nts 428–431) (Figure 9A). Next, BHK-21 cells were transfected with the monocistronic constructs IRES-FLuc-3΄UTR harboring the wild type (WT), the SL1a or Ha sequence. A plasmid bearing the Renilla luciferase reporter gene (RLuc) was added to control the transfection efficiency. In all cases, the luciferase activity observed in constructs SL1a and Ha was made relative to the wild type construct (pIC-3΄UTR). As shown in Figure 9B, while the Fluc activity was reduced in construct SL1a (0.63, P = 0.00071), there was no reduction in mutant Ha (0.95). No significant difference in the expression of Rluc was noticed in the same lysates. However, the Fluc/Rluc ratio for SL1a and Ha mutants, 0.86 and 0.96, respectively, showed no statistically significant differences relative to the wild type (set to 1). In agreement with the hypothesis of the existence of multiple interactions between the IRES and the 3΄UTR, these results suggest that lack of one of these distant interactions may be compensated by alternative base pairings.

Figure 9.

Functional analysis of the 3΄UTR sequences predicted to base pair with the IRES element. (A) Diagram of the base pairs disrupted between the domain 4 or domain 5 of the IRES and the 3΄UTR in constructs SL1a or Ha. Red letters depict nucleotide substitutions of the 3΄UTR sequence. (B) Translation efficiency of the SL1a and Ha constructs. The Firefly luciferase (Fluc) activity/μg of protein and Renilla luciferase (Rluc) activity/μg of protein was made relative to the values obtained for the wild type construct performed in parallel. Relative IRES activity (mean ± SD) was determined in transfected BHK-21 cells as the Fluc/Rluc ratio expressed from monocistronic constructs, then normalized to the activity observed for the wild type IRES (set to 1). Each experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated three times.

DISCUSSION

Initiation of translation in picornavirus and HCV RNAs relies on IRES elements (31,62). Our study provides new relevant information concerning the local flexibility of the FMDV IRES element adopted within the cell cytoplasm, which differs from that observed in vitro using the same functional transcript and the same SHAPE reagent. Interestingly, we observed that specific residues located on the apical region of domain 3 became protected within the cell, while they were unpaired (flexible) in naked RNA, suggesting RNA–protein or RNA–RNA interactions dependent on the cytoplasmic environment. In contrast, we noticed a higher flexibility of the initiation zone, in accordance with the general feature of mRNAs reported in vivo (56). Earlier studies aimed to decipher the RNA structure of the IRES element by in vivo dimethyl sulfate (DMS) footprint noticed differences in specific positions of domains 3, 4 and 5 of the IRES relative to the DMS probing performed in vitro (41), that are in agreement with those observed in the current study using NAI.

Here, we provide direct evidences for changes in the organization of the IRES region in the presence of the homologous 3΄UTR in a functional monocistronic construct, and conversely, the RNA conformation of the 3΄UTR is reorganized in the presence of the IRES element. The conformational plasticity derived from RNA probing data, which was also supported by covariation analysis and conserved helices prediction, suggest a direct crosstalk between these distant regions of the viral RNA, further supporting the relevance of the 3΄UTR in stimulating IRES-driven translation within cells (27). Earlier studies carried out with viral coding sequences (27,37) also confirmed the stimulatory effect of the 3΄UTR on IRES activity.

Although the IRES elements of picornaviruses and HCV are sufficient to promote protein synthesis, translation directed by these elements is enhanced by the 3΄UTR or a poly(A)-tail (63). This stimulation, which may be reminiscent of the 3΄poly(A) synergistic enhancement of the cap-dependent translation of cellular mRNAs (64), can be explained by the existence of functional bridges facilitated by RNA–protein interactions (65). As discussed by (66), it may also rely on the interaction between the 3΄UTR and proteins of the 40S ribosomal subunit residing in a region near the mRNA entry and exit sites, partially overlapping with the HCV IRES binding site (67). Recent structural analysis provided experimental evidences in support of the local dynamic conformation of IRES elements including those of HCV, HCV-like and FMDV (52,53,68,69). Indeed, the 40S-HCV IRES complex is conformational dynamic and undergoes slow large-scale rearrangements after binding (70).

The information regarding the 3D structure of the FMDV 3΄UTR is scarce. Here, we show that the local flexibility of the 3΄ UTR region determined in vitro differed from that mapped in living cells (Figure 3C and D). Structural analysis of the enterovirus 3΄UTR (71) showed the presence of two stem loops (X and Y) connected by a kissing loop (K). In the case of the aphthovirus 3΄UTR, our data show that SL1 was invariably predicted by RNA structure software imposing SHAPE reactivity, irrespectively of having the IRES element in cis (Figures 3 and 5), as well as by the covariation and prediction of conserved helices (Figures 4 and 7). The conformation of the 3΄UTR SL2 is more prone to structural reorganization than SL1, but no direct evidences for kissing loops were detected. The observation that the 3΄UTR became more flexible in the presence of the IRES element, suggested a crosstalk between these distant elements of the IL3 transcript, which concomitantly leads to a dynamic conformation of both RNA regions. Yet, the SL2 protections observed in the presence of the IRES were not statistically significant (Figure 6B). In this regard, it is worth noting that the standard deviation of the SHAPE reactivity reported for the 3΄UTR in living cells is generally higher than that of the coding sequences or the 5΄UTR (13). This variability could be attributed to fluctuations in the complex and dynamic cytoplasmic environment, including ions concentration or pH, weak or transient RNA–RNA and RNA–protein interactions, the flanking sequence context, and/or conformational changes of the RNA structure preferably affecting the 3΄UTR (72). In addition, the use of SHAPE reagents with relative long half-life could reflect RNP assembly and disassembly, cellular turnover, and other events unrelated to steady-state structure of RNA (13).

Given that computational analysis predicted a number of statistically significant base pairs between the 3΄UTR and the IRES, it is tempting to propose the existence of multiple 3΄UTR dynamic states. Thus, while base pair prediction within the sole 3΄UTR transcript accurately defines 3 stem loops, as in the model generated imposing values of SHAPE reactivity probing (Figure 3C, D), in silico analysis of chimeric transcripts fusing domains of the IRES to the 3΄UTR invariably predicts statistically significant base pairing between nts of SL2 with two conserved motifs of domain 5 (Figure 8). On the other hand, nts of SL1-H border could establish base pairs with nts located in domain 4 (Figure 8). Generally, there is a good agreement between the in silico predictions and the protected sites observed by SHAPE probing in the IL3 transcript relative to the IL transcript lacking the 3΄UTR sequence. Indeed, the differences leading to statistically significant protections observed along the region upstream of the initiator AUG in living cells (Figure 5B and C), also tended to accumulate over the same region in vitro (Supplementary Figure S2). Conversely, the presence of the IRES element in the monocistronic RNA affects the local flexibility of the 3΄UTR. This result suggested the possibility that multiple dynamic interactions could be established between the 3΄UTR and the IRES element.

To test this hypothesis, we generated two mutants aimed to disrupt the predicted base pairings between domain 4 (construct SL1a), or domain 5 (construct Ha) and the 3΄UTR. However, although SL1a mutant induced a modest decrease in FLuc, none of these mutants significantly altered the normalized IRES activity relative to the WT construct (Figure 9B). We interpret these data as a result of a flexible conformation, such that alternative distant interactions could compensate for each other. In agreement with the results of the current study, direct RNA–RNA interactions between the IRES and the 3΄UTR of the viral genome have been shown in vitro (1), irrespectively of the presence of the poly(A) tail. Moreover, although the intensity of the retarded complexes was significantly decreased by subdivision of the IRES in its modular domains, a faint but detectable retarded complex was detected with the domain 4–5 transcript, but not with those of domains 2 or 3. Also in support of our hypothesis, this study showed that the full-length 3΄UTR, but not the individual stem-loops SL1 or SL2, yielded a retarded complex with the transcript corresponding to the IRES element (1).

Throughout this work, we have observed that the probability of adopting a stable SL2 is significantly reduced in the RNA chimeras containing IRES domains compared to the 3΄UTR RNA lacking the IRES element. Although TRANSAT predicted conserved helices considering only sequence covariation without environmental factors, the SL2 and H secondary structures show a large conformational plasticity. In addition, SL2 and H helices, and those predicted between SL2 and H with residues located in domains 4 and 5 of the IRES element, would be mutually exclusive and may exist in equilibrium within the cell. Detection of tertiary interactions is a challenging task because they may involve bases that establish non-canonical base pairings; yet we observed sequence conservation in the interacting positions, which additionally were supported by covariation (see Supplementary Figures S3 and S4). Besides canonical interactions, non Watson-Crick base pairs could contribute to stabilize the helices.

Several reasons rule out a potential long-range interaction between the 3΄UTR and the luciferase reporter gene. All the transcripts used to determine differences in NAI reactivity contain the same reporter. Hence, a potential stable base pair between the 3΄UTR and the luciferase gene should be close to background when comparing IL3 versus L3 transcripts. Also support this idea the fact that the RNA structure determined using a transcript corresponding to the IRES alone (73) is similar to the structure found in vitro using the IRES-luciferase transcript (43,52). Additionally, in silico analysis of base pairing between the luciferase gene (1677 nts) and the FMDV 3΄UTR using IntaRNA (74) predicted distant interactions with energies ranging between −6.86 to −1.95 kcal/mol (Supplementary Figure S6). However, these predictions are not supported by differences in SHAPE reactivity.

In support of the biological relevance of the dynamic long-range interactions dependent upon SL2, a previous study showed that a RNA replicon harboring a deletion of the SL2 sequence was not viable, whereas deletion of SL1 yielded an attenuated virus (57). As shown for Dengue virus, RNA sequences involved in alternative long-range structures could constitute a mechanism to modulate the viral RNA 3D structure for efficient replication (75). In summary, our strategy comparing in-cell to in vitro SHAPE probing of functional monocistronic transcripts and in silico prediction of conserved helices revealed the conformational plasticity of the FMDV 3΄UTR region, and provided direct evidences for dynamic long-range interactions between this region and the IRES element. Evolutionary conserved competing structures in the genomic RNA that may be modulated by RNA-binding proteins could provide a mechanism for fine-tuning the conformations involved in distinct processes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by MINECO. We thank J Ramajo, J Fernandez-Chamorro and AM Embarek for help with the mutational analysis of the 3΄UTR, and R Francisco-Velilla, M Saiz and C Gutierrez for valuable comments on the manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad (MINECO) [BFU2014-54564]; Institutional grant from Fundación Ramón Areces. Funding for open access charge: MINECO [BFU2014-54564].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Serrano P., Pulido M.R., Saiz M., Martinez-Salas E.. The 3΄ end of the foot-and-mouth disease virus genome establishes two distinct long-range RNA-RNA interactions with the 5΄ end region. J. Gen. Virol. 2006; 87:3013–3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez D.E., Lodeiro M.F., Luduena S.J., Pietrasanta L.I., Gamarnik A.V.. Long-range RNA-RNA interactions circularize the dengue virus genome. J. Virol. 2005; 79:6631–6643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cimino P.A., Nicholson B.L., Wu B., Xu W., White K.A.. Multifaceted regulation of translational readthrough by RNA replication elements in a tombusvirus. PLoS Pathog. 2011; 7:e1002423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diviney S., Tuplin A., Struthers M., Armstrong V., Elliott R.M., Simmonds P., Evans D.J.. A hepatitis C virus cis-acting replication element forms a long-range RNA-RNA interaction with upstream RNA sequences in NS5B. J. Virol. 2008; 82:9008–9022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aktar S.J., Vivet-Boudou V., Ali L.M., Jabeen A., Kalloush R.M., Richer D., Mustafa F., Marquet R., Rizvi T.A.. Structural basis of genomic RNA (gRNA) dimerization and packaging determinants of mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV). Retrovirology. 2014; 11:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fajardo T. Jr, Sung P.Y., Roy P.. Disruption of specific RNA-RNA interactions in a double-stranded RNA virus inhibits genome packaging and virus infectivity. PLoS Pathog. 2015; 11:e1005321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller W.A., Jackson J., Feng Y.. Cis- and trans-regulation of luteovirus gene expression by the 3΄ end of the viral genome. Virus Res. 2015; 206:37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicholson B.L., White K.A.. Functional long-range RNA-RNA interactions in positive-strand RNA viruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014; 12:493–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon A.E., Miller W.A.. 3΄ cap-independent translation enhancers of plant viruses. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2013; 67:21–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilkinson K.A., Gorelick R.J., Vasa S.M., Guex N., Rein A., Mathews D.H., Giddings M.C., Weeks K.M.. High-throughput SHAPE analysis reveals structures in HIV-1 genomic RNA strongly conserved across distinct biological states. PLoS Biol. 2008; 6:e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spitale R.C., Crisalli P., Flynn R.A., Torre E.A., Kool E.T., Chang H.Y.. RNA SHAPE analysis in living cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013; 9:18–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubota M., Tran C., Spitale R.C.. Progress and challenges for chemical probing of RNA structure inside living cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015; 11:933–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smola M.J., Calabrese J.M., Weeks K.M.. Detection of RNA-protein interactions in living cells with SHAPE. Biochemistry. 2015; 54:6867–6875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romero-Lopez C., Berzal-Herranz A.. A long-range RNA-RNA interaction between the 5΄ and 3΄ ends of the HCV genome. RNA. 2009; 15:1740–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuplin A., Struthers M., Simmonds P., Evans D.J.. A twist in the tail: SHAPE mapping of long-range interactions and structural rearrangements of RNA elements involved in HCV replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 40:6908–6921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fricke M., Dunnes N., Zayas M., Bartenschlager R., Niepmann M., Marz M.. Conserved RNA secondary structures and long-range interactions in hepatitis C viruses. RNA. 2015; 21:1219–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mauger D.M., Golden M., Yamane D., Williford S., Lemon S.M., Martin D.P., Weeks K.M.. Functionally conserved architecture of hepatitis C virus RNA genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015; 112:3692–3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh D., Mohr I.. Viral subversion of the host protein synthesis machinery. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011; 9:860–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang S.K., Krausslich H.G., Nicklin M.J., Duke G.M., Palmenberg A.C., Wimmer E.. A segment of the 5΄ nontranslated region of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA directs internal entry of ribosomes during in vitro translation. J. Virol. 1988; 62:2636–2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pelletier J., Sonenberg N.. Internal initiation of translation of eukaryotic mRNA directed by a sequence derived from poliovirus RNA. Nature. 1988; 334:320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopez-Lastra M., Ramdohr P., Letelier A., Vallejos M., Vera-Otarola J., Valiente-Echeverria F.. Translation initiation of viral mRNAs. Rev. Med. Virol. 2010; 20:177–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez-Salas E., Francisco-Velilla R., Fernandez-Chamorro J., Lozano G., Diaz-Toledano R.. Picornavirus IRES elements: RNA structure and host protein interactions. Virus Res. 2015; 206:62–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Filbin M.E., Kieft J.S.. Toward a structural understanding of IRES RNA function. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2009; 19:267–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asnani M., Kumar P., Hellen C.U.. Widespread distribution and structural diversity of Type IV IRESs in members of Picornaviridae. Virology. 2015; 478:61–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lozano G., Martinez-Salas E.. Structural insights into viral IRES-dependent translation mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2015; 12:113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez-Salas E. The impact of RNA structure on picornavirus IRES activity. Trends Microbiol. 2008; 16:230–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopez de Quinto S., Saiz M., de la Morena D., Sobrino F., Martinez-Salas E.. IRES-driven translation is stimulated separately by the FMDV 3΄-NCR and poly(A) sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002; 30:4398–4405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradrick S.S., Walters R.W., Gromeier M.. The hepatitis C virus 3΄-untranslated region or a poly(A) tract promote efficient translation subsequent to the initiation phase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006; 34:1293–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song Y., Friebe P., Tzima E., Junemann C., Bartenschlager R., Niepmann M.. The hepatitis C virus RNA 3΄-untranslated region strongly enhances translation directed by the internal ribosome entry site. J. Virol. 2006; 80:11579–11588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romero-Lopez C., Barroso-Deljesus A., Garcia-Sacristan A., Briones C., Berzal-Herranz A.. End-to-end crosstalk within the hepatitis C virus genome mediates the conformational switch of the 3΄X-tail region. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:567–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niepmann M. Hepatitis C virus RNA translation. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2013; 369:143–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romero-Lopez C., Berzal-Herranz A.. The functional RNA domain 5BSL3.2 within the NS5B coding sequence influences hepatitis C virus IRES-mediated translation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2012; 69:103–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Witwer C., Rauscher S., Hofacker I.L., Stadler P.F.. Conserved RNA secondary structures in Picornaviridae genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001; 29:5079–5089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saiz M., Gomez S., Martinez-Salas E., Sobrino F.. Deletion or substitution of the aphthovirus 3΄ NCR abrogates infectivity and virus replication. J. Gen. Virol. 2001; 82:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Todd S., Towner J.S., Semler B.L.. Translation and replication properties of the human rhinovirus genome in vivo and in vitro. Virology. 1997; 229:90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Ooij M.J., Polacek C., Glaudemans D.H., Kuijpers J., van Kuppeveld F.J., Andino R., Agol V.I., Melchers W.J.. Polyadenylation of genomic RNA and initiation of antigenomic RNA in a positive-strand RNA virus are controlled by the same cis-element. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006; 34:2953–2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia-Nunez S., Gismondi M.I., Konig G., Berinstein A., Taboga O., Rieder E., Martinez-Salas E., Carrillo E.. Enhanced IRES activity by the 3΄UTR element determines the virulence of FMDV isolates. Virology. 2014; 448:303–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernandez N., Fernandez-Miragall O., Ramajo J., Garcia-Sacristan A., Bellora N., Eyras E., Briones C., Martinez-Salas E.. Structural basis for the biological relevance of the invariant apical stem in IRES-mediated translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:8572–8585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernandez-Chamorro J., Lozano G., Garcia-Martin J.A., Ramajo J., Dotu I., Clote P., Martinez-Salas E.. Designing synthetic RNAs to determine the relevance of structural motifs in picornavirus IRES elements. Sci. Rep. 2016; 6:24243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fuerst T.R., Niles E.G., Studier F.W., Moss B.. Eukaryotic transient-expression system based on recombinant vaccinia virus that synthesizes bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1986; 83:8122–8126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernandez-Miragall O., Martinez-Salas E.. In vivo footprint of a picornavirus internal ribosome entry site reveals differences in accessibility to specific RNA structural elements. J. Gen. Virol. 2007; 88:3053–3062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fernandez-Miragall O., Martinez-Salas E.. Structural organization of a viral IRES depends on the integrity of the GNRA motif. RNA. 2003; 9:1333–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lozano G., Fernandez N., Martinez-Salas E.. Magnesium-dependent folding of a picornavirus IRES element modulates RNA conformation and eIF4G interaction. FEBS J. 2014; 281:3685–3700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karabiber F., McGinnis J.L., Favorov O.V., Weeks K.M.. QuShape: rapid, accurate, and best-practices quantification of nucleic acid probing information, resolved by capillary electrophoresis. RNA. 2013; 19:63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Francisco-Velilla R., Fernandez-Chamorro J., Lozano G., Diaz-Toledano R., Martinez-Salas E.. RNA-protein interaction methods to study viral IRES elements. Methods. 2015; 91:3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reuter J.S., Mathews D.H.. RNAstructure: software for RNA secondary structure prediction and analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010; 11:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Darty K., Denise A., Ponty Y.. VARNA: Interactive drawing and editing of the RNA secondary structure. Bioinformatics. 2009; 25:1974–1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lai D., Proctor J.R., Zhu J.Y., Meyer I.M.. R-CHIE: a web server and R package for visualizing RNA secondary structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 40:e95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bernhart S.H., Hofacker I.L., Will S., Gruber A.R., Stadler P.F.. RNAalifold: improved consensus structure prediction for RNA alignments. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008; 9:474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wiebe N.J., Meyer I.M.. TRANSAT– method for detecting the conserved helices of functional RNA structures, including transient, pseudo-knotted and alternative structures. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010; 6:e1000823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pineiro D., Fernandez N., Ramajo J., Martinez-Salas E.. Gemin5 promotes IRES interaction and translation control through its C-terminal region. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:1017–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lozano G., Jimenez-Aparicio R., Herrero S., Martinez-Salas E.. Fingerprinting the junctions of RNA structure by an open-paddlewheel diruthenium compound. RNA. 2016; 22:330–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lozano G., Trapote A., Ramajo J., Elduque X., Grandas A., Robles J., Pedroso E., Martinez-Salas E.. Local RNA flexibility perturbation of the IRES element induced by a novel ligand inhibits viral RNA translation. RNA Biol. 2015; 12:555–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stassinopoulos I.A., Belsham G.J.. A novel protein-RNA binding assay: functional interactions of the foot-and-mouth disease virus internal ribosome entry site with cellular proteins. RNA. 2001; 7:114–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walter B.L., Nguyen J.H., Ehrenfeld E., Semler B.L.. Differential utilization of poly(rC) binding protein 2 in translation directed by picornavirus IRES elements. RNA. 1999; 5:1570–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ding Y., Tang Y., Kwok C.K., Zhang Y., Bevilacqua P.C., Assmann S.M.. In vivo genome-wide profiling of RNA secondary structure reveals novel regulatory features. Nature. 2014; 505:696–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rodriguez Pulido M., Sobrino F., Borrego B., Saiz M.. Attenuated foot-and-mouth disease virus RNA carrying a deletion in the 3΄ noncoding region can elicit immunity in swine. J. Virol. 2009; 83:3475–3485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takahashi M.K., Watters K.E., Gasper P.M., Abbott T.R., Carlson P.D., Chen A.A., Lucks J.B.. Using in-cell SHAPE-Seq and simulations to probe structure-function design principles of RNA transcriptional regulators. RNA. 2016; 22:920–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gutell R.R., Larsen N., Woese C.R.. Lessons from an evolving rRNA: 16S and 23S rRNA structures from a comparative perspective. Microbiol. Rev. 1994; 58:10–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shang L., Xu W., Ozer S., Gutell R.R.. Structural constraints identified with covariation analysis in ribosomal RNA. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e39383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramos R., Martinez-Salas E.. Long-range RNA interactions between structural domains of the aphthovirus internal ribosome entry site (IRES). RNA. 1999; 5:1374–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hellen C.U. IRES-induced conformational changes in the ribosome and the mechanism of translation initiation by internal ribosomal entry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009; 1789:558–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bung C., Bochkaeva Z., Terenin I., Zinovkin R., Shatsky I.N., Niepmann M.. Influence of the hepatitis C virus 3΄-untranslated region on IRES-dependent and cap-dependent translation initiation. FEBS Lett. 2010; 584:837–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sonenberg N., Hinnebusch A.G.. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell. 2009; 136:731–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weinlich S., Huttelmaier S., Schierhorn A., Behrens S.E., Ostareck-Lederer A., Ostareck D.H.. IGF2BP1 enhances HCV IRES-mediated translation initiation via the 3΄UTR. RNA. 2009; 15:1528–1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bai Y., Zhou K., Doudna J.A.. Hepatitis C virus 3΄UTR regulates viral translation through direct interactions with the host translation machinery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:7861–7874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamamoto H., Collier M., Loerke J., Ismer J., Schmidt A., Hilal T., Sprink T., Yamamoto K., Mielke T., Burger J. et al. . Molecular architecture of the ribosome-bound Hepatitis C Virus internal ribosomal entry site RNA. EMBO J. 2015; 34:3042–3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boerneke M.A., Dibrov S.M., Gu J., Wyles D.L., Hermann T.. Functional conservation despite structural divergence in ligand-responsive RNA switches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014; 111:15952–15957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Perard J., Leyrat C., Baudin F., Drouet E., Jamin M.. Structure of the full-length HCV IRES in solution. Nat. Commun. 2013; 4:1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fuchs G., Petrov A.N., Marceau C.D., Popov L.M., Chen J., O'Leary S.E., Wang R., Carette J.E., Sarnow P., Puglisi J.D.. Kinetic pathway of 40S ribosomal subunit recruitment to hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015; 112:319–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zoll J., Tessari M., Van Kuppeveld F.J., Melchers W.J., Heus H.A.. Breaking pseudo-twofold symmetry in the poliovirus 3΄-UTR Y-stem by restoring Watson-Crick base pairs. RNA. 2007; 13:781–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Spitale R.C., Flynn R.A., Zhang Q.C., Crisalli P., Lee B., Jung J.W., Kuchelmeister H.Y., Batista P.J., Torre E.A., Kool E.T. et al. . Structural imprints in vivo decode RNA regulatory mechanisms. Nature. 2015; 519:486–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fernandez-Miragall O., Lopez de Quinto S., Martinez-Salas E.. Relevance of RNA structure for the activity of picornavirus IRES elements. Virus Res. 2009; 139:172–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Busch A., Richter A.S., Backofen R.. IntaRNA: efficient prediction of bacterial sRNA targets incorporating target site accessibility and seed regions. Bioinformatics. 2008; 24:2849–2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.de Borba L., Villordo S.M., Iglesias N.G., Filomatori C.V., Gebhard L.G., Gamarnik A.V.. Overlapping local and long-range RNA-RNA interactions modulate dengue virus genome cyclization and replication. J. Virol. 2015; 89:3430–3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.