Abstract

Mrp catalyzes secondary Na+/H+ antiport and was hypothesized to have an additional primary energization mode. Mrp-dependent complementation of nonfermentative growth of an Escherichia coli respiratory mutant supported this hypothesis but is shown here to be related to increased expression of host malate:quinone oxidoreductase, not to catalytic activity of Mrp.

The bacterial Mrp antiporter is widely distributed and has important roles in Na+ and alkali resistance as well as specialized functions in some settings (5, 8). Mrp catalyzes secondary Na+/H+ exchange energized by the proton motive force (Δp) (3, 5, 7, 19). The possibility of an additional, primary mode of energization using redox energy was raised (http://saier-144-164.ucsd.edu/tcdb/index.php?tc = 2.A.63) because of the striking sequence similarity between several of the 6-7 hydrophobic proteins encoded by mrp operons to membrane-embedded subunits of proton-translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductases (complex I) of bacteria and mitochondria (3, 13, 14, 20). All mrp gene products are required for wild-type antiport levels (5, 8, 10), suggesting unusual complexity for a secondary antiporter. Primary energy coupling would facilitate cytoplasmic pH homeostasis at alkaline pH and low Δp (21). An exergonic reaction could energize Na+/H+ antiport with Na+ effluxed > H+ taken up, resulting in concurrent ΔΨ generation and cytoplasmic H+ accumulation. Supporting this scenario (7), we found that expression of the mrp operon from alkaliphilic Bacillus pseudofirmus OF4 caused a four- to fivefold increase in the otherwise poor nonfermentative growth of an NADH dehydrogenase mutant of Escherichia coli strain ANN0222 (Δnuo Δndh) (25). Comparable expression of NhaA, a secondary Na+/H+ antiporter of E. coli, did not similarly enhance nonfermentative growth of the respiratory mutant (8). We attempted to determine whether the growth complementation by Mrp had a redox basis and, if so, whether this activity was associated with Mrp itself or with a host enzyme.

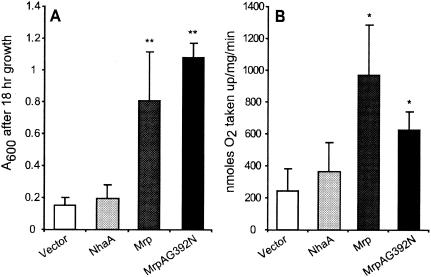

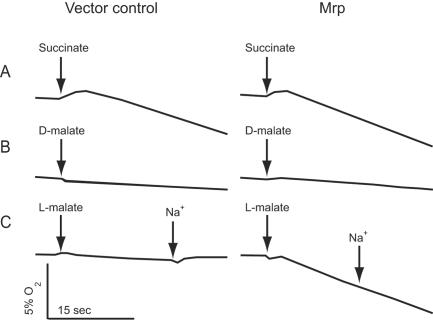

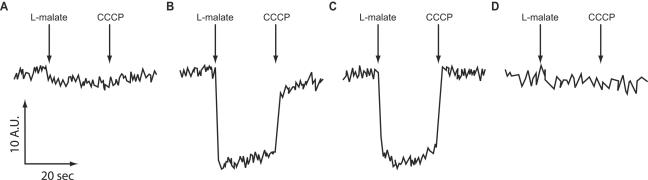

Mrp-dependent stimulation of oxygen uptake paralleled that of E. coli ANN0222 growth on l-lactate (Fig. 1), consistent with a redox basis for the enhanced growth. Previous work showed that Mrp does not confer either NADH dehydrogenase or terminal oxidase activity (3, 7, 8), and spectral studies revealed no difference in the cytochrome contents of membranes from mrp and control transformants of E. coli ANN0222 (data not shown). Therefore, if complementation is a direct effect of Mrp, then Mrp is likely to possess an activity that increases electron flow via quinone to the host terminal oxidases. The complementation could also arise from an indirect effect caused by enhanced activity of a host respiratory enzyme that increases electron flow to the terminal oxidases. Potential electron donors were screened for their effect on oxygen uptake by everted membrane vesicles of E. coli ANN0222 transformed with the control vector pMW118 or the recombinant vector expressing the B. pseudofirmus OF4 mrp operon (7). A positive control, succinate, supplies electrons to the terminal oxidases via the host succinate dehydrogenase. Succinate supported O2 uptake similarly in the two vesicle preparations (Fig. 2A), while among the many test compounds, including d-malate (Fig. 2B), only l-malate significantly increased oxygen uptake in an Mrp-specific manner (Fig. 2C). Although the absolute values varied among independent experiments, the ratio of Mrp vesicles to control vesicles with succinate was 1.5/1, while the ratio with l-malate was reproducibly 4/1. Importantly, this increase was not dependent upon added Na+ (Fig. 2C), as would be expected if it depended upon a primary Na+ extrusion mechanism (1). Similarly, Mrp- and l-malate-dependent ΔΨ generation was observed in a fluorescence assay of the everted vesicles (Fig. 3A and B), but Na+ had no stimulatory effect (Fig. 3C). Na2SO4 was routinely used instead of NaCl since chloride ions reduce the ΔΨ of energized E. coli vesicles (17). However, other sodium salts, including NaCl and NaHCO3, also failed to stimulate. Moreover, no ΔΨ generation was observed in the presence of cyanide and added quinone (Fig. 3D), as would be expected if Mrp itself is an l-malate:quinone oxidoreductase (MQO).

FIG. 1.

Nonfermentative growth and O2 uptake of E. coli ANN0222 transformants. Cells were grown on a semi-defined medium (9) containing 0.025% yeast extract, 0.1% trace salts, and 20 mM Tris-l-lactate (7). Transformants of E. coli ANN0222 with empty vector were compared to transformants expressing NhaA, the B. pseudofirmus OF4 Mrp, and a mutant of the B. pseudofirmus Mrp, MrpAG392N, that is deficient in Na+ efflux. (A) A600 of cultures after 18 h of growth. (B) O2 consumption by mid-log-phase cells that were transferred to a 37°C chamber, agitated, and assayed for O2 consumption with a Clarke-type electrode. The rate of O2 uptake is expressed in nanomoles of O2 per milligram per minute. The results here are averages of at least four independent experiments, with error bars indicating the standard deviations from the mean. * and **, P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, by two-sample unpooled variance t test (StatPlot).

FIG. 2.

Screening of electron donors for Mrp for their effect on O2 consumption by everted E. coli ANN0222 vesicles. Everted membrane vesicles from control and mrp-expressing E. coli ANN0222 were assayed for O2 consumption in response to numerous candidate electron donors, monitored with a Clark-type oxygen electrode as described elsewhere (24). The assay mix contained 300 μg of everted vesicles in 10 mM Tris-MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid)-25 mM MgSO4-10% glycerol, pH 7.5. Results are shown for control and Mrp vesicles with succinate-dependent O2 consumption as a positive control (A), d-malate-dependent O2 consumption as a negative control (B), and l-malate-dependent O2 consumption with the addition of 100 mM NaCl at the arrow (C).

FIG. 3.

Assessment of Mrp- and l-malate-dependent ΔΨ generation in everted E. coli ANN0222 vesicles. Everted membrane vesicles from control and mrp-expressing E. coli ANN0222 were assayed for ΔΨ generation in response to l-malate, monitored by quenching of oxonol VI as described elsewhere (24). The assay mix contained 200 μg of everted vesicles in 10 mM Tris-HEPES, pH 7.5. Results are shown for ANN0222/pMW118 control vesicles (A), ANN0222/Mrp vesicles (B), and ANN0222/Mrp vesicles with 10 mM Na2SO4 (C). For panel D, 10 mM KCN and 10 μM menadione were added 1 min before energization of the ANN0222/Mrp vesicles; the results were identical with and without 10 mM Na2SO4. Each trace is representative of at least three independent experiments. In each experiment, the traces were repeated two to three times. A.U., arbitrary units.

Mrp-dependent MQO activity of the vesicles was assayed by phenazine methosulfate-mediated bleaching of the electron acceptor 2,6-dichlorophenolinophenol (DCPIP) (4, 16). Protein was measured by the Lowry method (12). The MQO activities were 0.7 and 0.1 μmol/min/mg of protein in the mrp-expressing and control vesicles, respectively; the activity of succinate dehydrogenase, a positive control, was 2 μmol/min/mg of protein in both types of vesicles. The Mrp-dependent MQO activity in the E. coli ANN0222 vesicles was unaffected by added Na+, and no Mrp- and l-malate-dependent 22Na+ accumulation was observed in everted membrane vesicles of transformants of antiporter-deficient E. coli KNabc (ΔnhaA ΔnhaB ΔchaA) (18; data not shown). Although E. coli MQO is the product of a single gene and is a peripheral enzyme that only adheres modestly to membranes (11, 15, 16, 23), we investigated the possibility that mrp expression caused a large secondary increase in E. coli mqo expression and a corresponding increase in membrane-associated MQO. We also sought to determine whether such an increase occurred specifically in the respiration-deficient E. coli strain ANN0222, which has diminished capacity for respiration-dependent proton pumping and ΔΨ generation. MQO activity was assayed in the membrane and cytosolic fractions of three E. coli transformants: E. coli ANN0222 grown on l-lactate (8) and E. coli KNabc and the wild-type E. coli strain DH5α (Gibco-BRL) grown in LBK (3). Na+ (200 mM) was added to the growth medium of the mrp transformant of E. coli KNabc; this concentration is inhibitory for the control transformant and ensured that the mrp transformant was expressing an active antiporter. There were strain-specific variations in total MQO activity, but only E. coli ANN0222 exhibited a Mrp-dependent increase in overall MQO activity. The MQO activity of mrp transformant membranes was about four times higher than that of the control preparation (Table 1). The membrane fractions from the different strains contained 10 to 20% of the total MQO activity, consistent with the literature values (23).

TABLE 1.

MQO activity of the membrane and supernatant fractions of control and mrp-expressing transformants of three E. coli strains

| Fraction | MQO activity (100 μmol/min)a

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANN0222

|

KNabc

|

DH5α

|

||||

| Vector | Mrp | Vector | Mrp | Vector | Mrp | |

| Membranes | 0.10 (12) | 0.51 (15) | 0.59 (18) | 0.57 (17) | 0.16 (6) | 0.070 (6) |

| Cytoplasm | 0.73 (88) | 2.98 (85) | 2.66 (82) | 2.77 (83) | 2.52 (94) | 1.15 (94) |

| Membranes + cytoplasm | 0.83 | 3.49 | 3.25 | 3.34 | 2.68 | 1.22 |

Control (Vector) or mrp (Mrp) transformants of the indicated E. coli strains were fractionated after French pressure cell treatment for vesicle preparation, and both the membrane and supernatant fractions were assayed for MQO activity and protein. DCPIP bleaching was monitored via A600 in assay mixtures of 1 ml containing 100 to 200 μg of vesicles suspended in 10 mM bis-Trispropane-sulfate-5 mM MgSO4, pH 7.5, and assayed as described previously (4, 16). Protein was measured by the Lowry method (12). The values in the table are total units of MQO in the indicated fraction(s). The values were highly reproducible among duplicate determinations in independent experiments. The values in parentheses are the percentage of each fraction of the total units for that strain.

The inference from the data in Table 1 is that the Mrp-dependent stimulation of E. coli ANN0222 growth on l-lactate results from an indirect effect of expression of the mrp operon that is not related to the Na+/H+ antiport capacity of Mrp. We tested the capacity of a mutant mrp that lacks Na+/H+ activity to enhance nonfermentative growth of the respiratory chain mutant. An MrpA-G392N mutation was introduced into the wild-type mrp operon cloned in pMW118 by the method of Horton (6). Consistent with loss of Na+/H+ antiport activity by a mutation in the same position of another alkaliphile, mrpA (3), this mutant mrp did not confer Na+ resistance in Na+-sensitive E. coli KNabc but the same mutant plasmid still complemented the growth and oxygen uptake phenotypes of E. coli ANN0222 (Fig. 1). The data negate the hypothesis that Mrp-dependent stimulation of nonfermentative growth and oxygen uptake of E. coli ANN0222 indicates a primary energization mode for Mrp. Rather, endogenous MQO can partially complement the E. coli ANN0222 phenotype when its expression increases as a secondary result of some effect of mrp. We do not know precisely how expression of either a functional or nonfunctional mrp operon leads to increased MQO only in the respiration-deficient strain. Perhaps expression of these heterologous Mrp membrane proteins from a multicopy plasmid creates a minor ion leak in the membrane. Whereas strains with a normal respiratory chain might easily compensate via respiration-dependent proton extrusion, the resulting depolarization or altered cytoplasmic ion complement of E. coli ANN0222 may lead to mqo induction.

The similarity between several Mrp proteins and membrane-embedded subunits of ion-coupled NADH dehydrogenases probably reflects common functions in the cation conducting pathway in the these respiratory chain complexes and in a secondary Mrp antiporter system (2, 14, 22). The basis for the requirement for an unusual number of gene products for this antiporter system is yet to be resolved. Given the efficacy of Mrp in pH homeostasis in alkaliphiles, it will be of interest to explore whether multiple Mrp proteins confer added stability or kinetic competence on this secondary Na+/H+ antiporter.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Area ‘Genomic Biology’ and the 21rst Century Center of Excellence of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Sciences and Technology (to M.I.) and by research grant GM28454 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (to T.A.K.). T.H.S is supported by a predoctoral Cell and Molecular Biology training grant (GM08553) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dimroth, P. 1997. Primary sodium ion translocating enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1318:11-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedrich, T., and D. Scheide. 2000. The respiratory complex I of bacteria, archaea and eukarya and its module common with membrane-bound multisubunit hydrogenases. FEBS Lett. 479:1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamamoto, T., M. Hashimoto, M. Hino, M. Kitada, Y. Seto, T. Kudo, and K. Horikoshi. 1994. Characterization of a gene responsible for the Na+/H+ antiporter system of alkalophilic Bacillus species strain C-125. Mol. Microbiol. 14:939-946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatefi, Y., and D. L. Stiggall. 1978. Preparation and properties of succinate:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex II). Methods Enzymol. 53:21-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiramatsu, T., K. Kodama, T. Kuroda, T. Mizushima, and T. Tsuchiya. 1998. A putative multisubunit Na+/H+ antiporter from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 180:6642-6648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horton, R. M. 1997. In vitro recombination and mutagenesis of DNA. SOEing together tailor-made genes. Methods Mol. Biol. 67:141-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito, M., A. A. Guffanti, and T. A. Krulwich. 2001. Mrp-dependent Na+/H+ antiporters of Bacillus exhibit characteristics that are unanticipated for completely secondary active transporters. FEBS Lett. 496:117-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito, M., A. A. Guffanti, B. Oudega, and T. A. Krulwich. 1999. mrp, a multigene, multifunctional locus in Bacillus subtilis with roles in resistance to cholate and to Na+ and in pH homeostasis. J. Bacteriol. 181:2394-2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaworowski, A., H. D. Campbell, M. I. Poulis, and I. G. Young. 1981. Genetic identification and purification of the respiratory NADH dehydrogenase of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 20:2041-2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosono, S., Y. Ohashi, F. Kawamura, M. Kitada, and T. Kudo. 2000. Function of a principal Na+/H+ antiporter, ShaA, is required for initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 182:898-904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kretzschmar, U., A. Ruckert, J. H. Jeoung, and H. Gorisch. 2002. Malate:quinone oxidoreductase is essential for growth on ethanol or acetate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 148:3839-3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowry, O. H., N. J. Rosebrough, A. L. Farr, and R. J. Randall. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathiesen, C., and C. Hägerhäll. 2003. The ‘antiporter module’ of respiratory chain complex I includes the MrpC/NuoK subunit—a revision of the modular evolution scheme. FEBS Lett. 5459:7-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathiesen, C., and C. Hägerhäll. 2002. Transmembrane topology of the NuoL, M and N subunits of NADH:quinone oxidoreductase and their homologues among membrane-bound hydrogenases and bona fide antiporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1556:121-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Molenaar, D., M. E. van der Rest, A. Drysch, and R. Yücel. 2000. Functions of the membrane-associated and cytoplasmic malate dehydrogenases in the citric acid cycle of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 182:6884-6891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molenaar, D., M. E. van der Rest, and S. Petrovic. 1998. Biochemical and genetic characterization of the membrane-associated malate dehydrogenase (acceptor) from Corynebacterium glutamicum. Eur. J. Biochem. 254:395-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura, T., C. Hsu, and B. P. Rosen. 1986. Cation/proton antiport systems in Escherichia coli. Solubilization and reconstitution of delta pH-driven sodium/proton and calcium/proton antiporters. J. Biol. Chem. 261:678-683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nozaki, K., K. Inaba, T. Kuroda, M. Tsuda, and T. Tsuchiya. 1996. Cloning and sequencing of the gene for Na+/H+ antiporter of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 222:774-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Putnoky, P., A. Kereszt, T. Nakamura, G. Endre, E. Grosskopf, P. Kiss, and A. Kondorosi. 1998. The pha gene cluster of Rhizobium meliloti involved in pH adaptation and symbiosis encodes a novel type of K+ efflux system. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1091-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saier, M. H., Jr., B. H. Eng, S. Fard, J. Garg, D. A. Haggerty, W. J. Hutchinson, D. L. Jack, E. C. Lai, H. J. Liu, D. P. Nusinew, A. M. Omar, S. S. Pao, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Quan, M. Sliwinski, T. T. Tseng, S. Wachi, and G. B. Young. 1999. Phylogenetic characterization of novel transport protein families revealed by genome analyses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1422:1-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skulachev, V. P. 1999. Bacterial energetics at high pH: what happens to the H+ cycle when the extracellular H+ concentration decreases? Novartis Found. Symp. 221:200-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stolpe, S., and T. Friedrich. 2004. The Escherichia coli NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) is a primary proton pump but may be capable of secondary sodium antiport. J. Biol. Chem. 279:18377-18383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Rest, M. E., C. Frank, and D. Molenaar. 2000. Functions of the membrane-associated and cytoplasmic malate dehydrogenases in the citric acid cycle of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182:6892-6899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waggoner, A. S. 1979. Dye indicators of membrane potential. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng. 8:47-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallace, B. J., and I. G. Young. 1977. Aerobic respiration in mutants of Escherichia coli accumulating quinone analogues of ubiquinone. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 461:75-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]