Abstract

The 2 hemiketal (HK) eicosanoids HKD2 and HKE2 are the major products of the biosynthetic crossover of the 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) pathways. HKs result from the rearrangement of a di-endoperoxide intermediate formed in the COX-2-dependent oxygenation of 5S-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (5S-HETE). We analyzed HK biosynthesis in human leukocytes stimulated ex vivo and defined the biosynthetic roles of 5-LOX and COX-2, using inhibitors and incubations with exogenous substrates. Activation of leukocytes with LPS followed by treatment with the calcium ionophore A23187 resulted in the formation of PGE2, 5-HETE, and LTB4 as the principal metabolites of COX-2 and 5-LOX, respectively. The formation of HKD2 and HKE2 was highest after 15 min LPS treatment, and at that time, levels were similar to PGE2, but less than 5-HETE and LTB4. The time course of HK formation paralleled that of 5-HETE and LTB4, implying the availability of the 5S-HETE substrate as a limiting factor in biosynthesis rather than expression levels of COX-2. Specific inhibitors of COX-2 and 5-LOX decreased formation of HKD2 and HKE2. Platelets did not form HKs from exogenous 5S-HETE, implying that COX-1 is not involved. HKs are early products during an inflammatory event and require cells that express 5-LOX and COX-2 for their biosynthesis.—Giménez-Bastida, J. A., Shibata, T., Uchida, K., Schneider, C. Roles of 5-lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase-2 in the biosynthesis of hemiketals E2 and D2 by activated human leukocytes.

Keywords: arachidonic acid, prostaglandin, leukotriene

5-Lipoxygenase (5-LOX) and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 are key enzymes in the biosynthesis of arachidonic acid–derived eicosanoids (1). COX oxygenation of arachidonic acid gives the prostaglandin (PG) endoperoxide PGH2 that is further transformed by specialized isomerases to the 5 chief prostanoids PGE2, PGD2, PGF2α, PGI2 (prostacyclin), and TxA2 (thromboxane A2) (2, 3). PGs regulate a myriad of physiologic and pathophysiological responses at the sites of their formation (4). Inhibition of PG biosynthesis by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs has anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, and analgesic effects through inhibition of the inducible COX-2 isoform, whereas inhibition of the COX-1 isoform is responsible for gastrointestinal side effects (5). Cardiovascular side effects related to specific inhibition of COX-2 by the coxib class of drugs are linked to the loss of PGI2 in the vascular endothelium (6).

5-LOX oxygenation of arachidonic acid gives rise to 5S-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid (5S-HPETE), which can undergo reduction to 5S-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (5S-HETE) or oxidation to 5-oxoeicosatetraenoic acid, a potent eosinophil chemoattractant and stimulant (7, 8). The major fate of 5S-HPETE, however, is dehydration to the leukotriene (LT) epoxide LTA4 in a second reaction catalyzed by 5-LOX (9, 10). Enzymatic hydrolysis of LTA4 yields LTB4, a proinflammatory neutrophil chemoattractant (11, 12). Conjugation of LTA4 with glutathione yields the cysteinyl-LT (LTC4) that increases vascular permeability at sites of inflammation (13, 14). The signaling pathways mediated by LTB4 and Cys-LTs are well defined, whereas much less is known about specific biologic activities of 5S-HETE (15).

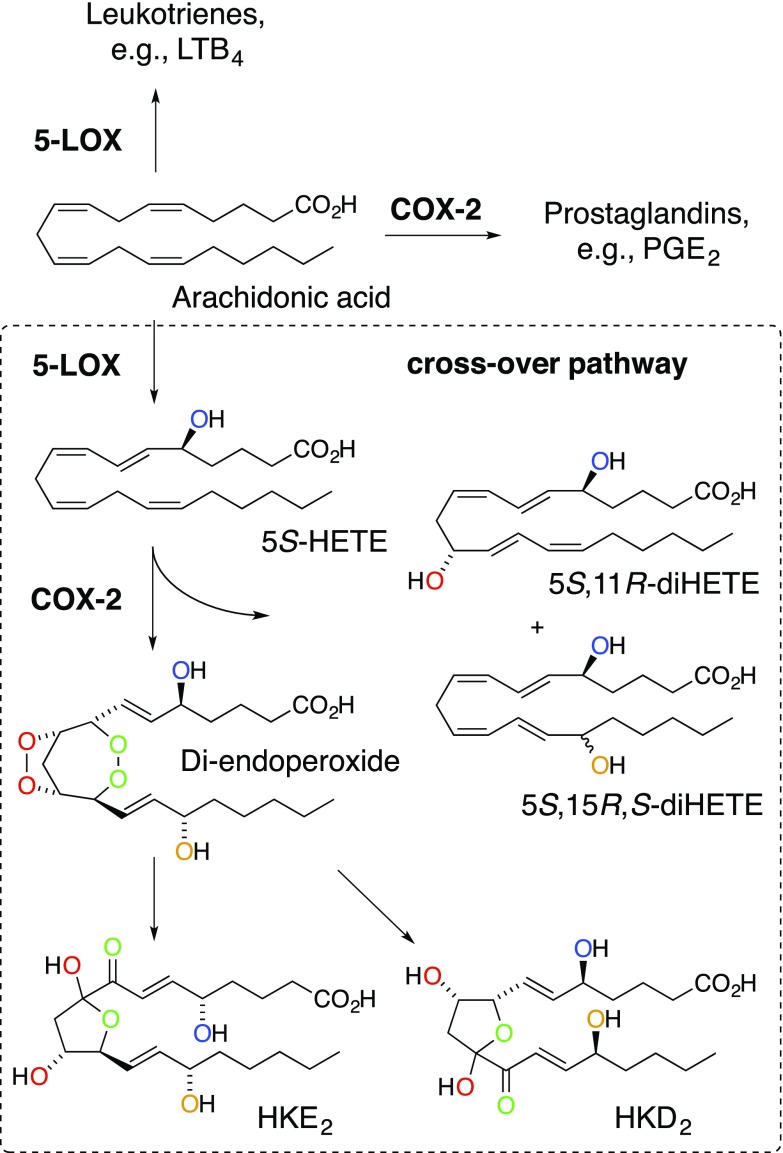

5S-HETE can serve as an alternative substrate for COX-2, thereby providing a biosynthetic link between the 5-LOX and COX-2 pathways (Fig. 1). A diendoperoxide has been identified as the major enzymatic product, with 5S,11R- and 5S,15R,S-diHETE as minor products (16–18). The diendoperoxide is functionally equivalent to PGH2 and undergoes similar transformations (19, 20). Nonenzymatic rearrangement of the two endoperoxide moieties results in two hemiketal (HK) eicosanoids, HKE2 and HKD2, the latter of which may also be formed by reaction with the hematopoietic type of PGD synthase (20). The two 5S,11R- and 5S,15R,S-diHETEs are the 5-hydroxy analogs of the 11R-HETE and 15R,S-HETE by-products of the COX reaction with arachidonic acid (21). Biosynthesis of 5,11- and 5,15-diHETEs occurs in human leukocytes stimulated ex vivo, and their formation is dependent on the activities of 5-LOX and COX-2 (22).

Figure 1.

The 5-LOX/COX-2 crossover pathway. Consecutive transformation of arachidonic acid by 5-LOX and COX-2 yielded the hemiketal (HK) eicosanoids HKD2 and HKE2 as well as the by-products 5,11- and 5,15-diHETE. The oxygen atoms introduced in the enzymatic reactions are color-coded to illustrate their origin and fate during the transformations.

HKs are recently discovered eicosanoids, and information is sparse about their biosynthesis in vivo and their biologic role. Stemming from 5-LOX and COX-2 as their key biosynthetic enzymes, a role in regulating the inflammatory process and possibly in tumorigenesis can be predicted. Preliminary studies have shown that HKs stimulate tube formation of primary pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells, implying a role in angiogenesis and wound repair (20).

Understanding the biologic significance of the crossover of the 5-LOX and COX-2 pathways and its HK products requires information about the sites, amount, and temporal regulation of their biosynthesis. We describe an approach for the quantitative analysis of HK biosynthesis, using charge reversal derivatization and liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS) detection in positive ion mode (23). The method was used to quantify levels of HKs in human leukocytes stimulated ex vivo in comparison to the 5-LOX and COX-2 metabolites, 5-HETE, LTB4, and PGE2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

5S-HETE was synthesized as described, with minor modifications (19, 24). Curcumin was synthesized as described (25). Recombinant human COX-2 was expressed in Sf9 insect cells (26). MK886, NS398, PGE2, d4-PGE2, d4-LTB4, and N-(4-aminomethylphenyl)pyridinium (AMPP) were from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Dimethylformamide, AA861, 1-ethyl-3-(ε-dimethylamino-propyl)carbodiimide, and N-hydroxybenzotriazole were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Lumiracoxib was from ApexBio (Houston, TX, USA).

Synthesis of HKE2 and HKD2

5S-HETE (15 μg) was added to 1 ml 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8) containing COX-2 (25 nM), hematin (1 μM), and phenol (0.5 mM), and the reaction was incubated at 37°C for the first 5 min and then held at room temperature for 45 min (27). The sample was acidified to pH 3 with 1 N HCl, spiked with 50 μl methanol, and loaded on a 30-mg HLB cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The cartridge was washed with water, and products were eluted using 1 ml methanol and evaporated under a stream of N2.

Leukocyte isolation and treatment

Leukocytes were isolated from peripheral blood from healthy human volunteers. The study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (Approval 091243), and written informed consent was obtained from the donors before blood samples were obtained. Venous blood (45 ml) was collected into a syringe containing 4.5 ml sodium citrate and 10 ml of 6% (w/v) dextran (250 kDa, average molecular mass). Red blood cells were allowed to settle for 1 h, and the top leukocyte-rich layer was collected and centrifuged. The pelleted cells were washed with PBS, and the remaining red cells were lysed by treatment with a 10-fold excess of deionized water for 30 s followed by addition of 10× PBS to restore tonicity. The leukocytes were centrifuged, washed, and diluted in PBS containing 5 mM glucose. Cells (5.0 × 106) were diluted to 1 ml in PBS containing Ca2+ and Mg2+, LPS (10 μg/ml) was added, and the cells were incubated at 37°C for various times (15 min to 48 h). Calcium ionophore A23187 (5 μM) was added 15 min before the end of LPS treatment. For termination, the samples were centrifuged at 1200 g for 5 min, and the supernatant was transferred to a glass vial containing 1 ml of 0.1% acetic acid (pH 3). Deuterated standards, d4-LTB4 and d4-PGE2, 10 ng each, were added, and the samples were loaded onto 30 mg HLB cartridges (Waters). Cartridges were activated with 2 × 1 ml of methanol and washed with 2 × 1 ml water before use. After sample loading, the cartridges were washed with 2 × 1 ml water, and products were eluted from the cartridge using 1 ml of methanol. To some of the leukocyte samples, one of the following inhibitors was added 15 min before treatment with A23187: NS398 (1 μM), AA861 (10 μM), MK886 (5 μM), SC560 (1 μM), or lumiracoxib (0.1–1 μM). COX-2 expression was analyzed by Western blot analysis after separation on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (20 μg of protein) and transfer to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were washed and incubated with monoclonal primary antibody against COX-2 (72 kDa) (Cayman Chemical) at 1:1000, followed by incubation with anti-mouse IgG (GE Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA ) horseradish peroxidase–linked secondary antibody at 1:1000. Membranes were developed with ECL Prime Western Blot detection reagent (GE Life Sciences) and exposed to X-ray film. Monoclonal antibody anti-GAPDH (36 kDa) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) at 1:1000 was used as the control for protein loading.

Standard curves, limits of detection, and quantification

Eicosanoids were quantified by preparing standard curves using the pure compounds. The first point of the standard curve was a stock solution containing 1 ng of PGE2 and 10 ng each of 5S-HETE, LTB4, and HKE2. This solution was serially diluted. d4-LTB4 and d4-PGE2 (10 ng of each) were added to each dilution. The samples were evaporated under a stream of nitrogen and derivatized with AMPP, as described below. The samples were then diluted with water:acetonitrile (1:1, v/v) to 80 μl. The calibration curves were calculated by plotting the ratio between the peak area of each compound vs. the peak area of the internal standard. Each point was the average of 3 independent injections. Retention time, calibration range, linear range, limit of detection (LOD), and limit of quantification (LOQ) are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Calibration curves and LOD and LOQ for 5S-HETE, LTB4, HKE2, and PGE2

| Compound | Retention time (min) | Calibration curve (ng) | R2 | Linear range (ng) | LOD (pg) | LOQ (pg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5S-HETE | 4.88 | y = 24.24x | 0.996 | LOQ–0.156 | 0.360 | 1.220 |

| LTB4 | 3.91 | y = 30.07x | 0.983 | LOQ–0.311 | 0.090 | 0.300 |

| HKE2 | 2.31 | y = 3.27x | 0.994 | LOQ–1.250 | 0.370 | 1.220 |

| PGE2 | 3.01 | y = 69.79x | 0.982 | LOQ–0.125 | 0.005 | 0.015 |

Derivatization with AMPP

The methanol eluates from the extraction cartridges were evaporated under a stream of nitrogen, and the following reagents were added: 10 μl of ice-cold acetonitrile/dimethylformamide (4:1, v/v), 10 μl of ice-cold 1-ethyl-3-(ε-dimethylamino-propyl)carbodiimide (640 mM in water), and 20 μl of a solution containing 5 mM N-hydroxylbenzotriazole and 15 mM AMPP (in acetonitrile) (23). The sample tubes were briefly vortex mixed and incubated at 60°C for 30 min. The samples were diluted with 40 μl of acetonitrile/water (1:1, v/v) and analyzed the same day while maintained at 4°C in the autosampler during analysis.

Leukocyte isolation in the presence of curcumin

Venous blood (7.5 ml) was drawn into a syringe containing 750 μl of sodium citrate and 1.67 ml of 6% (w/v) dextran (250 kDa, average molecular mass). The solution was treated with 80 μl of a 5 mM curcumin stock solution to a final concentration of 40 μM. The isolation of the leukocytes was followed as described above. PBS, deionized water, and 10× PBS used in the different steps contained 40 μM curcumin. The cells were treated with LPS (10 μg/ml) for 5 h at 37°C. A23187 (5 μM) was added 15 min before the end of the incubation with LPS. Extraction, derivatization, and analysis of eicosanoids were performed as previously described.

Incubations with platelet-rich plasma

Blood (10 ml) was drawn from 2 volunteers (IRB 091243). Platelet-rich plasma was obtained by centrifugation (28). Platelet-rich plasma (995 μl; 2.5 × 108 platelets/ml) were treated with 5 μl of 1 mM 5S-HETE or arachidonic acid to a final concentration of 5 μM. The samples were incubated at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by addition of 3 volumes of ethanol and centrifuged at 4700 g for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new vial and spiked with deuterated standards (d4-LTB4 and d4-PGE2). The samples were evaporated under nitrogen to remove ethanol and extracted using 30-mg Waters HLB cartridges as previously described. The samples were derivatized with AMPP and analyzed by LC-MS.

LC-MS analyses

Samples were analyzed with a Thermo TSQ Vantage triple quadrupole MS instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a heated electrospray interface operated in negative or positive ion mode. A Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 1.8-μm column (2.1 × 50 mm; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used for the separation of eicosanoids. Water:acetonitrile (95:5, v/v) and acetonitrile:water (95:5, v/v) containing 0.1% formic acid were the mobile phases (A and B, respectively) used at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Underivatized samples were analyzed in negative ion mode, and a linear gradient was used starting with 100% of solvent A, reaching 100% of solvent B at 5 min, and held for 1 min. The initial conditions were reestablished at 6.01 min and held until 7 min. AMPP-derivatized samples were analyzed in positive ion mode. The initial solvent was 100% of A, reaching 50% of B at 4.5 min, 100% of B at 5 min, and held for 1 min. At 6.01 min, solvent A was 100% and held up to 7 min. The instrument parameters were optimized by infusion of a solution of PGD2 in acetonitrile/water 1:1 (by vol.). The electrospray needle was maintained at 4.0 kV. The ion transfer tube was operated at 300°C.

The following transitions were recorded in the selected reaction monitoring (SRM)–positive mode for AMPP-derivatized compounds: LTB4, m/z 503→323 (+30 eV); d4-LTB4, m/z 507→325 (+35 eV); 5-HETE, m/z 487→283 (+37 eV); PGE2, m/z 519→239 (+40 eV); d4-PGE2, m/z 523→241 (+40 eV); HKE2, m/z 567→381 (+35 eV); HKD2, m/z 567→369 (+35 eV); and TxB2, m/z 567→337 (+35 eV). The ion transitions recorded for SRM in negative ion mode were: LTB4, m/z 335→195 (+20 eV); d4-LTB4, m/z 339→197 (+20 eV); 5-HETE, m/z 319→115 (+20 eV); PGE2, m/z 351→271 (+15 eV); d4-PGE2, m/z 355→275 (+15 eV); HKE2, m/z 399→151 (+15 eV); and HKD2, m/z 399→183 (+15 eV).

Statistical analysis

Results are means ± sd. Significant differences were analyzed using Prism 5 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). For normally distributed data, 1-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test was used. A value of P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

RESULTS

LC-ESI-MS quantification method

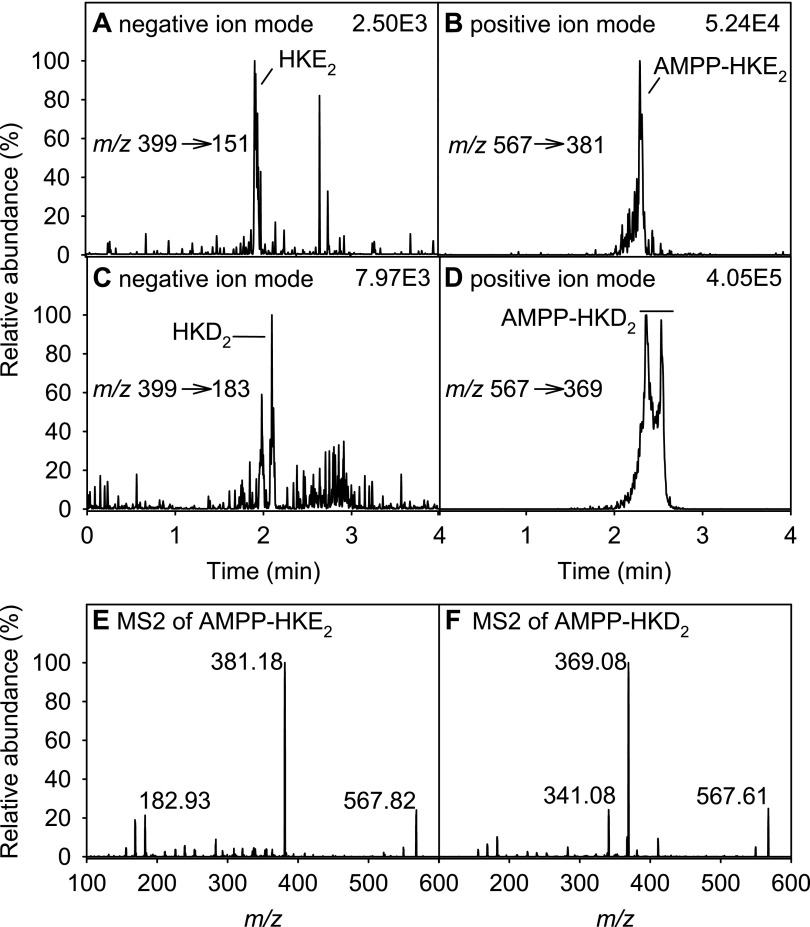

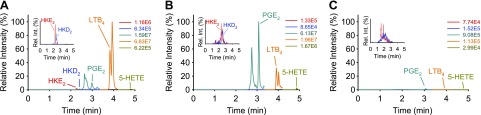

We compared detection of the fatty acid carboxylate anion in negative ion mode LC-MS with charge-reversal derivatization to a positively charged amide according to the method developed by Bollinger and coworkers (23). Authentic standards of HKD2, HKE2, and 5,15- and 5,11-diHETE were prepared by reacting 5S-HETE with recombinant human COX-2 (20). Derivatization with AMPP and positive ion detection resulted in an increase in the signal-to-noise ratio for HKs by about 20–50-fold compared to the underivatized eicosanoids analyzed in negative ion mode (Fig. 2A–D). In contrast with HKE2, we consistently found that HKD2 eluted as a poorly defined peak in RP-HPLC analyses, regardless of whether it was derivatized, and also when different HPLC columns were used. Positive ion detection of AMPP-derivatized PGE2, LTB4, and 5-HETE was also significantly increased compared to negative ion detection of underivatized samples.

Figure 2.

LC-SRM-MS analysis of underivatized and AMPP-derivatized HK eicosanoids formed in the reaction of 5S-HETE with COX-2 in vitro. A, B) HKE2 was analyzed directly in negative ion mode (A) or after derivatization with AMPP in positive ion mode (B). C, D) The same analyses were performed with HKD2 (C) and AMPP-HKD2 (D). E, F) LC-ESI-MS2 spectra of AMPP-derivatized HKE2 (E) and HKD2 (F).

MS2 fragmentation of AMPP-derivatized HKD2 and HKE2 was used to identify characteristic fragment ions for SRM analyses (Fig. 2E, F). A major fragment of HKE2 was at m/z 381.2, equivalent to an AMPP derivative of the C-terminal fragment m/z 213 formed in the negative ion MS2, which results from cleavage of the C-10/C-11 bond and of the hemiketal moiety (20). For HKD2 an equivalent fragment was observed at m/z 369.1 which is the AMPP-derivatized C-terminal fragment of cleavage at C9/C10 (20). The 2 fragments enabled distinguishing the HKs by using different mass filters. The SRM transitions for AMPP-derivatized PGE2, LTB4, and 5-HETE were taken from the original method by Bollinger and coworkers (23).

Deuterated analogs of the HKs were not available as internal standards, and therefore, HKs were quantified using calibration curves (Table 1). Calibration curves were constructed to determine relative detection efficiencies for HKE2 vs. d4-PGE2. HKD2 was quantified by using the same calibration curve. 5-HETE and LTB4 were quantified using d4-LTB4 as the internal standard. The LOD and LOQ were determined to be 0.4 and 1.2 pg, respectively, of AMPP-derivatized HKE2 injected into the column.

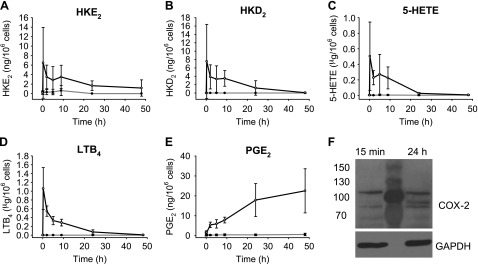

Time course of HK biosynthesis in stimulated leukocytes

Biosynthesis of HKs in vitro requires consecutive transformation of arachidonic acid by 5-LOX and COX-2 (20). 5-LOX activity in peripheral blood leukocytes can be stimulated using the calcium ionophore A23187 (29, 30), whereas COX-2 expression is induced in response to treatment with LPS (31). We first analyzed the formation of HKs as a function of the length of incubation time with LPS, using time points at 15 min and 2, 5, 9, 24, and 48 h. Leukocytes were stimulated with the calcium ionophore A23187 for 15 min before the end of the LPS incubation, followed by acidification, C18 cartridge extraction, AMPP-derivatization, and LC-MS analysis. In this pilot experiment, leukocytes from 3 volunteers were analyzed. The highest amounts of HKE2 and HKD2 were present at 15 min incubation time with LPS, followed by a decline over the next 8 h, with little to no formation from 9 to 48 h (Fig. 3A, B). The time course of HK formation was parallel to the 5-LOX products 5-HETE and LTB4 (Fig. 3C, D). In contrast, formation of PGE2 steadily increased over the incubation time with LPS and was highest at 48 h (Fig. 3E). The increase of PGE2 was compatible with induction of the expression of COX-2 by LPS which was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3F). COX-2 was detected in the leukocytes at the earliest time point (15 min), coinciding with the formation of HKE2 and HKD2. Eicosanoids were not increased without LPS and A23187 stimulation.

Figure 3.

Time course of eicosanoid biosynthesis in human leukocytes. A–E) HKE2 (A) and HKD2 (B), as well as 5-HETE (C), LTB4 (D), and PGE2 (E) were quantified using LC-SRM-MS analyses after derivatization with AMPP. F) Western blot analysis of COX-2 expression in leukocytes at 15 min and after 24 h stimulation with LPS. The central lane was loaded with protein molecular mass markers. Leukocytes were isolated from peripheral blood and stimulated with LPS (10 μg/ml) at 37°C for the time indicated (15 min, 2, 5, 9, 24, and 48 h) including treatment with A23187 (5 μM) during the final 15 min. Open circles: LPS-treated samples; closed circles: vehicle treated (unstimulated) controls. Error bars: SD of leukocyte samples obtained from 3 volunteers.

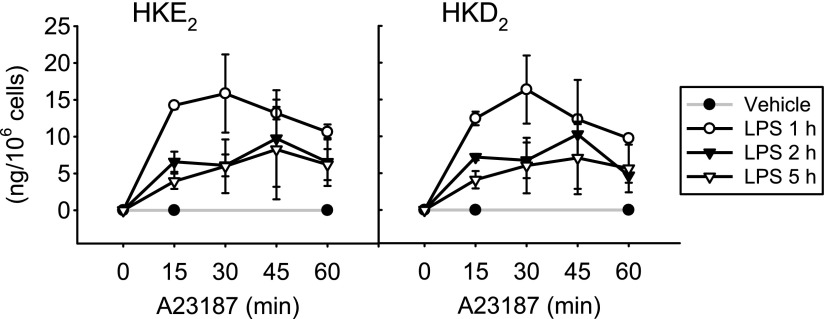

Time course of A23187 treatment

We next determined the levels of HKs as a function of the incubation time with A23187. In vitro experiments have shown that nonenzymatic rearrangement of the di-endoperoxide to the HKs in vitro takes about 30–45 min (20). On the other hand, because the HKs contain an electrophilic enone moiety, extensive incubation times in the presence of activated cells could result in loss caused by binding to protein or glutathione or by other metabolic transformation (20). We found that the levels of HKE2 and HKD2 were similar in leukocytes treated with A23187 for 5, 15, 30, and 60 min (Fig. 4). There was either little loss and gain of HKs during the 1 h treatment with A23187 or a possible loss through metabolism or adduction by cellular nucleophiles was compensated by increased formation of HKs.

Figure 4.

Effect of incubation time with A23187 on HK biosynthesis. Human leukocyte samples were treated with LPS for 1, 2, or 5 h, and A23187 (5 μM) was added for the final 15, 30, 45, or 60 min. The error bars indicate the sd of the mean of 3 replicates using leukocytes from 1 volunteer.

Quantification of HKs in leukocytes

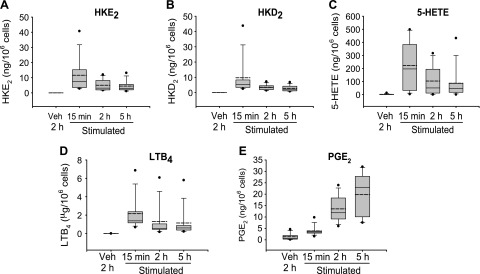

Peripheral venous blood samples were obtained from 10 normal healthy volunteers. Based on the initial time course analysis, leukocytes were incubated with LPS for 15 min and 2 and 5 h or with vehicle for 2 h. Biosynthesis of HKs as well as PGE2, 5-HETE, and LTB4 was quantified by LC-MS analysis of AMPP-derivatized samples. Formation of HKE2 and HKD2 was readily detected in the stimulated samples, with levels of ∼10 ng/106 cells at 15 min (Fig. 5A, B), which was 10- to 100-fold lower than 5-HETE and LTB4 (Fig. 5C, D). After a 15-min incubation with LPS, the HKs were more abundant than PGE2 which showed the expected increase at 2- and 5-h incubation with LPS (Fig. 5E). Formation of HKs was parallel to 5-HETE and LTB4, confirming the initial LPS time course that was obtained using fewer samples (Fig. 3).

Figure 5.

Quantification of eicosanoid formation in human leukocytes. Leukocytes were isolated from peripheral blood and stimulated with LPS (10 μg/ml) at 37°C for the time points indicated followed by treatment with A23187 (5 μM) for 15 min before extraction, derivatization (AMPP), and LC-SRM-MS quantification. Vehicle control samples (no LPS and A23187 stimulation) were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. HKE2 (A) HKD2 (B), 5-HETE (C), LTB4 (D), and PGE2 (E). The box plots indicate the spread of the values between the 25th and 75th percentiles. Solid horizontal line: median; dashed horizontal line: the mean; filled circles: the highest and lowest data points. Values were derived from 10 volunteers. Veh, vehicle.

Inhibition studies

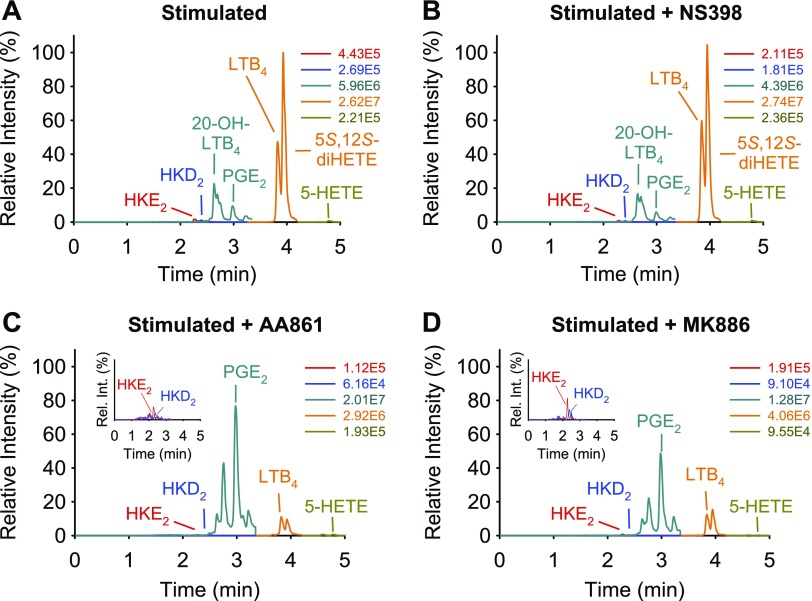

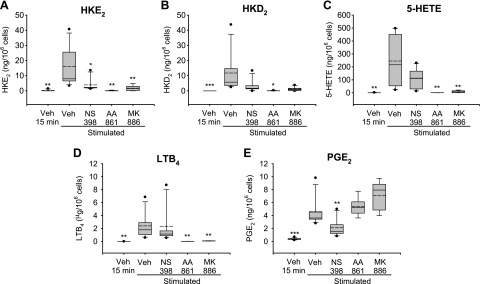

Aliquots of the leukocyte samples were treated with inhibitors for COX-2 (NS398, 1 μM), 5-LOX (AA861, 10 μM), and FLAP (MK886, 5 μM), to determine the contribution of these enzymes to the biosynthesis of HKs. Leukocytes were treated with LPS for 15 min or 5 h. In the case of 5 h LPS stimulation, inhibitors and A23187 were added 30 and 15 min, respectively, before the end of stimulation. For the 15-min LPS incubation time, cells were first treated with inhibitors for 15 min and then stimulated with LPS and A23187 for an additional 15 min. LC-MS analyses showed a decrease of HKE2 and HKD2 in response to all 3 inhibitors (Fig. 6). As expected, the peaks for 5-HETE and LTB4 were reduced by AA861 and MK886. In addition, 20-hydroxy-LTB4, as a metabolite of LTA4, and 5S,12S-diHETE, the platelet 12-LOX metabolite of 5S-HETE, were also decreased by AA861 and MK886. The effect of the 3 inhibitors was quantified in leukocyte samples from 7 volunteers (Fig. 7). NS398 at 1 μM reduced HK levels in most but not all of the samples, but it had little effect on the other 5-LOX products. NS398 reduced the levels of PGE2 by about half, indicating that COX-2 is incompletely inhibited or that COX-1 may contribute to the formation of PGE2. The 5-LOX inhibitor AA861 and the FLAP inhibitor MK886 were highly effective in reducing formation of HKs, their precursor 5-HETE, and LTB4. Similar results were obtained by inhibitor treatment of cells stimulated with LPS for 5 h (data not shown).

Figure 6.

LC-MS analysis of eicosanoids formed by stimulated human leukocytes and their inhibition. Human leukocytes were stimulated with LPS (10 μg/ml for 5 h) and A23187 (5 μM; 15 min), and treated with vehicle (A) or 1 μM NS398 (B), 10 μM AA861 (C), or 5 μM MK886 (D). AMPP-derivatized samples were analyzed, using LC-SRM-MS in the positive ion mode. The signal intensities for all ion chromatograms are shown relative to the highest peak in A, set at 100%. The peak eluting in front of PGE2 was identified as 20-hydroxy-LTB4 by coelution with an authentic standard. The peak eluting after LTB4 is 5S,12S-diHETE, formed by 12-LOX reaction with 5S-HETE. The absolute intensities for each ion chromatogram are given, and the insets show the elution of HKE2 and HKD2 in an expanded view.

Figure 7.

Effect of 5-LOX and COX-2 inhibitors on eicosanoid formation in human leukocytes. HKE2 (A) and HKD2 (B) as well as 5-HETE (C), LTB4 (D), and PGE2 (E) were quantified by using LC-SRM-MS analyses after derivatization with AMPP. Inhibitors were added 15 min before stimulation with LPS (10 μg/ml) and A23187 (5 μM) at 37°C for 15 min. The inhibitors used were NS398 (1 μM), AA861 (10 μM), or MK886 (5 μM). The box plots indicate the spread of the values between the 25th and 75th percentiles. Solid horizontal line: median; dashed horizontal line: the mean; filled circles: the highest and lowest data points. Leukocytes from 7 volunteers were used. Veh, vehicle. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 in comparison to stimulated and vehicle-treated sample.

Because NS398 did not completely inhibit HK biosynthesis in some of the leukocyte samples, we tested the more specific COX-2 inhibitor lumiracoxib (32). With lumiracoxib, HKE2 was reduced by 37% at 15 min LPS stimulation and 90% at 5 h stimulation, whereas inhibition of PGE2 was reduced less (35% inhibition at 15 min and 70% at 5 h). Incomplete inhibition was similar to the effects seen with NS398 and may be attributable to the fact that lumiracoxib inhibits COX-2 activity to only approximately half at elevated substrate concentrations (32), as would be the case with 5S-HETE at the early time points (Figs. 3 and 5). Again, however, a role of COX-1 in formation of HKs could not be excluded entirely, based on these results.

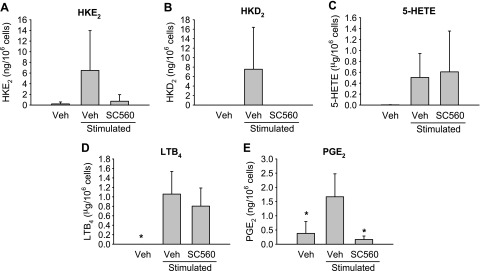

As an alternative to inhibition of COX-2, we attempted to test the role of COX-1, using the COX-1-specific inhibitor SC560 (33). SC560 unexpectedly reduced the formation of HKE2, HKD2, and PGE2 to baseline levels (Fig. 8). Whether this inhibitory effect of SC560 truly indicates a contribution of COX-1 to HK biosynthesis was considered doubtful. It has been reported that SC560 loses selectivity for COX-1 when the inhibitor is used in intact cells (34). For example, in a whole-blood assay, the IC50 for inhibition of LPS-induced PGE2 synthesis was reported to be 128 nM for SC560, compared with 120 nM for rofecoxib (34) (i.e., SC560 was as potent in inhibiting COX-2, as the COX-2 selective inhibitor rofecoxib).

Figure 8.

Effect of SC560 on eicosanoid formation in human leukocytes. HKE2 (A) and HKD2 (B), as well as 5-HETE (C), LTB4 (D), and PGE2 (E), were quantified using LC-SRM-MS analyses after derivatization with AMPP. SC560 (1 μM) was added 15 min before the stimulation with LPS (10 μg/ml) and A23187 (5 μM) for additional 15 min. Veh, vehicle. *P < 0.05 in comparison to stimulated and vehicle-treated sample.

Incubation of platelets and leukocytes with 5S-HETE and arachidonic acid

The possibility that COX-1 contributes to HK biosynthesis was not ruled out based on the findings with the inhibitors. Thus, we tested whether platelets as a major cellular source of COX-1 (but not COX-2) were able to form HKs upon incubation with exogenous 5S-HETE. Platelet-rich plasma was prepared from 2 human volunteers. Incubation of the platelets with 5S-HETE resulted in the formation of 5S,12S-diHETE as the abundant product of platelet 12-LOX (22), whereas there was no formation of HKs (Fig. 9A). When platelet-rich plasma was incubated with arachidonic acid, there was increased formation of TxB2 as the major COX-1 metabolite (Fig. 9B). The use of exogenous 5S-HETE and arachidonic acid as substrates by 12-LOX and COX-1, respectively, showed that the platelets were biosynthetically active. The lack of conversion of exogenous 5S-HETE to HKs in platelets indicated that COX-1 is not involved in the biosynthesis of HKs ex vivo.

Figure 9.

Incubation of human platelet-rich plasma and leukocytes with 5S-HETE and arachidonic acid. A, B) Platelet-rich plasma was incubated with 5S-HETE (A) or arachidonic acid (B). C, D) Isolated leukocytes were incubated with 5S-HETE (C) or arachidonic acid (D). Extracted eicosanoids were derivatized and analyzed by LC-SRM-MS. The ion chromatograms are shown relative to the highest peak in each panel, and the absolute intensities are given.

Control reactions with isolated leukocytes showed that 5S-HETE was used as an exogenous substrate for formation of HKE2 (1.0 ng/106 cells) and HKD2 (0.5 ng/106 cells), whereas its transformation to LTA4/LTB4 via 5-LOX is catalytically not possible (Fig. 9C). When leukocytes were incubated with exogenous arachidonic acid and stimulated, all measured eicosanoids were increased, including HKE2, (6.0 ng/106 cells) and HKD2, (7.0 ng/106 cells) (Fig. 9D).

Inhibition of HK formation by curcumin

Curcumin, the main bioactive ingredient in turmeric extract, inhibits the activities of 5-LOX and COX-2 but not COX-1 (35, 36). In addition, it inhibits expression of COX-2 in monocytes by down-regulating NF-κB activity (37, 38). Leukocytes were treated with curcumin to analyze whether reduced expression of COX-2 and inhibition of 5-LOX would result in reduced formation of HKs by stimulated leukocytes (Fig. 10). Leukocyte samples from 5 volunteers were treated with 40 μM curcumin added to the syringe during blood sampling and during all subsequent leukocyte isolation steps including washing and treatment with LPS and A23187. Curcumin inhibited not only the formation of HKs but also formation of 5-HETE and LTB4, as well as PGE2.

Figure 10.

Curcumin inhibits formation of eicosanoids in activated human leukocytes. Leukocytes were isolated and processed in the presence of curcumin (40 μM). LC-SRM-MS chromatograms for the analysis of AMPP derivatized eicosanoids are shown for leukocytes isolated in the absence (A, B) or presence (C) of curcumin (40 μM) and activated with LPS (10 μg/ml) for 15 min (A) or 5 h (B, C). All samples were treated with A23187 (5 μM) for 15 min before the end of incubation. The peak eluting after LTB4 is 5,12-diHETE, the peak eluting before PGE2 is 20-hydroxy-LTB4. The ion chromatograms are shown in relative intensity to the highest peak in A. The absolute intensities for each ion chromatogram are given, and the insets show the elution of HKE2 and HKD2 in an expanded view.

DISCUSSION

We have developed an LC-SRM-MS method for the quantification of HKE2 and HKD2 in biologic samples. Charge-reversal derivatization of extracted cell supernatants according to the method developed by Bollinger and coworkers (23) resulted in a significant increase in the signal-to-noise ratio for detection of HKs and PGE2, 5-HETE, and LTB4. Although a similar increase in signal to noise was obtained with the HK biosynthetic by-products, 5,11- and 5,15-diHETE (17), the actual leukocyte samples contained co- and closely eluting contaminants that interfered with quantification of the diHETEs. Quantification of diHETEs was better achieved with underivatized samples and LC-MS analysis in negative ion mode (22). Before using AMPP-derivatization of the carboxylate, we had tested hydrazone derivatization of the carbonyl groups, using 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine and pentafluorophenylhydrazine to form a negatively polarized derivative independent of the carboxylate and to protect the electrophilic ketoene from further transformation. A major complication with these approaches was the inconsistent formation of a mixture of mono- and diderivatized products, the latter stemming from reaction of the second carbonyl, present as the hemiketal moiety, in HKD2 and HKE2. We did not further pursue carbonyl derivatization strategies because derivatization of the hidden carbonyl appeared to be slow and not quantitative. Beyond increased sensitivity, the AMPP-derivatization approach offered the additional advantage that biosynthetically related eicosanoids of interest are derivatized similarly and detected in the same LC-MS runs. The analytical method will be useful for the detection and quantification of HK biosynthesis in animal and human tissue samples to further explore the pathophysiologic roles of HKs.

Biosynthesis of HKs in vitro requires 5-LOX and COX-2 to act in tandem on arachidonic acid (20). In the leukocyte mixtures stimulated ex vivo, contribution of 5-LOX and COX-2 was analyzed by use of specific inhibitors for both enzymes. 5-LOX inhibition, as expected, completely eliminated HK formation, and we then conducted a series of experiments to determine whether only COX-2 or perhaps also COX-1 is involved in HK biosynthesis ex vivo. We did not want to dismiss a role for COX-1 in leukocytes, based simply on in vitro experiments where COX-1 is clearly unable to react with 5S-HETE (16). For example, the COX-2-specific substrate 2-arachidonyl-glycerol (2-AG) is not oxygenated by COX-1 in vitro but there is evidence from knockout animals that COX-1 may be involved in oxygenation of 2-AG in vivo (39). There was residual biosynthetic activity with the COX-2-specific inhibitor NS398. Incomplete inhibition of HK formation in some of the samples could have been related to the use of a relatively low concentration of NS398 (1 μM). Inhibition of LPS-induced PGE2 formation was also incomplete, indicating that the remaining COX-2 activity is a likely explanation (Fig. 7E), although expression of COX-1 by the leukocytes is an alternative possibility (31). Additional experiments using lumiracoxib did not provide clarification either, because this inhibitor has shown only incomplete, albeit highly selective, inhibition of COX-2 (32). There had been a but weak indication from the results with the COX-1-specific inhibitor SC560 for a role of COX-1 in HK biosynthesis but, again, these findings were not unequivocal, because SC560 loses selectivity and potently inhibits COX-2 in intact cells (34). Thus, the experiments with specific inhibitors confirmed a major role for COX-2, but did not rule out a contribution of COX-1 in HK biosynthesis in or ex vivo.

We attempted transcriptional inhibition of COX-2 expression in the leukocytes by using curcumin, but curcumin not only inhibited formation of HKs and PGE2 but also of 5-HETE and LTB4. Thus, the contribution of COX-1 and -2 to HK biosynthesis could not be differentiated by using this approach.

As a final approach, we incubated platelet-rich plasma and leukocytes from human volunteers with exogenous 5S-HETE. Platelets contain only COX-1 as a source of cyclooxygenase activity. Although leukocytes formed HKs from exogenous 5S-HETE, the platelets did not, thus arguing against a role for COX-1 in the biosynthesis of HKs. Together, these experiments can be interpreted to show that COX-2 is the only cyclooxygenase involved in HK biosynthesis in leukocytes. Ultimately, analysis of COX isoform–specific knockout animals should provide a definitive answer to this question.

HK biosynthesis unexpectedly tracked in parallel with the availability of the 5S-HETE substrate rather than with the level of COX-2 activity (Figs. 3, 5). It is possible that at the early time points of LPS treatment (less than 2 h) 5S-HETE was more abundant or more readily available than arachidonic acid as a substrate for COX-2. 5-LOX activity does not require de novo protein synthesis; the enzyme is present in neutrophils and other leukocytes without induction (40). 5-LOX is immediately activated upon LPS-dependent Ca2+ influx, whereas COX-2 requires transcriptional activation, for example, by LPS acting as an activator of TLRs (41, 42). COX-2 activity in forming HKs at the early time point was already present in the leukocytes before induction of the PTGS-2 gene by LPS. Induction of COX-2 may have occurred by shear forces during the cell-isolation process, in that leukocytes isolated in the presence of curcumin, which is a transcriptional and enzymatic inhibitor of COX-2 (35, 37, 38), did not form HKs or PGE2.

When the incubation time with LPS was less than 2 h, HK levels were similar to the levels of PGE2, implying that HKs are abundant products of leukocytes in certain conditions. This ratio changed over time with levels of PGE2 steadily increasing, whereas HKs took the opposite turn.

Selective inhibition of COX-2 by the coxib class of analgesic and anti-inflammatory drugs is associated with myocardial infarction and other significant cardiovascular events (43). The side effects have been linked to a reduction in PGI2 derived from endothelial COX-2, which counterbalances the proaggregatory effects of TxA2, a product of platelet COX-1 (6). The discovery of ester and amide derivatives of arachidonic acid (2-AG and related endocannabinoids), as well as 5S-HETE, as selective substrates of COX-2 (16, 44, 45) has opened up the possibility that selective inhibition of their oxygenation by coxibs plays a role in the adverse cardiovascular effects of these drugs. Animal studies of the inhibition of COX-2 dependent oxygenation of 2-AG have been linked to an increase in endocannabinoid signaling that was associated with a decrease in anxiety, whereas it was not related to overt cardiovascular effects (46). It remains to be determined whether the HKs formed by oxygenation of 5S-HETE by COX-2 play a role in vascular homeostasis. If this role were protective, then selective inhibition of HK formation by coxibs may contribute to the adverse cardiovascular effects of this class of drugs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Ginger Milne for providing the AMPP reagent used in the initial phase of the study, and Dr. Noemi Tejera Hernandez (both from Vanderbilt University) for exploratory work on this project. This work was supported by U. S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Grant R01GM076592 and National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Grant R01AT006896 (to C.S); postdoctoral award 16POST30690001 from the American Heart Association (to J.A.G.-B.); Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 26252018 (to K.U.); and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Oxygen Biology: a new criterion for integrated understanding of life” 26111011 of the Ministry of Education, Sciences, Sports, Technology (MEXT), Japan; and a grant from the Japan Science and Technology Agency Precursory Research for Embryonic Science and Technology (PRESTO) program (to T.S.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIGMS or the NIH. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- 2-AG

2-arachidonyl-glycerol

- AMPP

N-(4-aminomethylphenyl)pyridinium

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- FLAP

5 lipoxygenase-activating protein

- HETE

hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- HK

hemiketal

- HPETE

hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- LC

liquid chromatography

- LOD

limit of detection

- LOQ

limit of quantification

- LOX

lipoxygenase

- MS

mass spectrometry

- LT

leukotriene

- PG

prostaglandin

- PGI2

prostacyclin

- SRM

selected reaction monitoring

- Tx

thromboxane

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J. A. Giménez-Bastida performed all experiments, except for those in Fig. 3, which were performed by T. Shibata and J. A. Giménez-Bastida; C. Schneider designed the study and wrote the paper together with K. Uchida; and all authors analyzed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Funk C. D. (2001) Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science 294, 1871–1875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rouzer C. A., Marnett L. J. (2003) Mechanism of free radical oxygenation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by cyclooxygenases. Chem. Rev. 103, 2239–2304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith W. L., Urade Y., Jakobsson P. J. (2011) Enzymes of the cyclooxygenase pathways of prostanoid biosynthesis. Chem. Rev. 111, 5821–5865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smyth E. M., Grosser T., Wang M., Yu Y., FitzGerald G. A. (2009) Prostanoids in health and disease. J. Lipid Res. 50(Suppl), S423–S428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ricciotti E., FitzGerald G. A. (2011) Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 31, 986–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grosser T., Fries S., FitzGerald G. A. (2006) Biological basis for the cardiovascular consequences of COX-2 inhibition: therapeutic challenges and opportunities. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 4–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell W. S., Gravelle F., Gravel S. (1992) Metabolism of 5(S)-hydroxy-6,8,11,14-eicosatetraenoic acid and other 5(S)-hydroxyeicosanoids by a specific dehydrogenase in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 19233–19241 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Flaherty J. T., Kuroki M., Nixon A. B., Wijkander J., Yee E., Lee S. L., Smitherman P. K., Wykle R. L., Daniel L. W. (1996) 5-Oxo-eicosatetraenoate is a broadly active, eosinophil-selective stimulus for human granulocytes. J. Immunol. 157, 336–342 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rouzer C. A., Matsumoto T., Samuelsson B. (1986) Single protein from human leukocytes possesses 5-lipoxygenase and leukotriene A4 synthase activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83, 857–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin J., Zheng Y., Boeglin W. E., Brash A. R. (2013) Biosynthesis, isolation, and NMR analysis of leukotriene A epoxides: substrate chirality as a determinant of the cis or trans epoxide configuration. J. Lipid Res. 54, 754–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X.-S., Sheller J. R., Johnson E. N., Funk C. D. (1994) Role of leukotrienes revealed by targeted disruption of the 5-lipoxygenase gene. Nature 372, 179–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy R. C., Gijón M. A. (2007) Biosynthesis and metabolism of leukotrienes. Biochem. J. 405, 379–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynch K. R., O’Neill G. P., Liu Q., Im D. S., Sawyer N., Metters K. M., Coulombe N., Abramovitz M., Figueroa D. J., Zeng Z., Connolly B. M., Bai C., Austin C. P., Chateauneuf A., Stocco R., Greig G. M., Kargman S., Hooks S. B., Hosfield E., Williams D. L. Jr., Ford-Hutchinson A. W., Caskey C. T., Evans J. F. (1999) Characterization of the human cysteinyl leukotriene CysLT1 receptor. Nature 399, 789–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy R. C., Hammarström S., Samuelsson B. (1979) Leukotriene C: a slow-reacting substance from murine mastocytoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76, 4275–4279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powell W. S., Rokach J. (2005) Biochemistry, biology and chemistry of the 5-lipoxygenase product 5-oxo-ETE. Prog. Lipid Res. 44, 154–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider C., Boeglin W. E., Yin H., Stec D. F., Voehler M. (2006) Convergent oxygenation of arachidonic acid by 5-lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase-2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 720–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulugeta S., Suzuki T., Hernandez N. T., Griesser M., Boeglin W. E., Schneider C. (2010) Identification and absolute configuration of dihydroxy-arachidonic acids formed by oxygenation of 5S-HETE by native and aspirin-acetylated COX-2. J. Lipid Res. 51, 575–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuwata H., Hara S. (2015) Inhibition of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 4 facilitates production of 5, 11-dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid via the cyclooxygenase-2 pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 465, 528–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griesser M., Boeglin W. E., Suzuki T., Schneider C. (2009) Convergence of the 5-LOX and COX-2 pathways: heme-catalyzed cleavage of the 5S-HETE-derived di-endoperoxide into aldehyde fragments. J. Lipid Res. 50, 2455–2462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griesser M., Suzuki T., Tejera N., Mont S., Boeglin W. E., Pozzi A., Schneider C. (2011) Biosynthesis of hemiketal eicosanoids by cross-over of the 5-lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase-2 pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 6945–6950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider C., Boeglin W. E., Prusakiewicz J. J., Rowlinson S. W., Marnett L. J., Samel N., Brash A. R. (2002) Control of prostaglandin stereochemistry at the 15-carbon by cyclooxygenases-1 and -2: a critical role for serine 530 and valine 349. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 478–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tejera N., Boeglin W. E., Suzuki T., Schneider C. (2012) COX-2-dependent and -independent biosynthesis of dihydroxy-arachidonic acids in activated human leukocytes. J. Lipid Res. 53, 87–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bollinger J. G., Thompson W., Lai Y., Oslund R. C., Hallstrand T. S., Sadilek M., Turecek F., Gelb M. H. (2010) Improved sensitivity mass spectrometric detection of eicosanoids by charge reversal derivatization. Anal. Chem. 82, 6790–6796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corey E. J., Hashimoto S. (1981) A practical process for large-scale synthesis of (S)-5-hydroxy-6-trans-8,11,14,cis-eicosatetraenoic acid (5-HETE). Tetrahedron Lett. 22, 299–302 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gordon O. N., Graham L. A., Schneider C. (2013) Facile synthesis of deuterated and [(14) C]labeled analogs of vanillin and curcumin for use as mechanistic and analytical tools. J. Labelled Comp. Radiopharm. 56, 696–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider C., Boeglin W. E., Brash A. R. (2004) Identification of two cyclooxygenase active site residues, Leucine 384 and Glycine 526, that control carbon ring cyclization in prostaglandin biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 4404–4414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giménez-Bastida J. A., Suzuki T., Sprinkel K. C., Boeglin W. E., Schneider C. (2016) Biomimetic synthesis of hemiketal eicosanoids for biological testing. [E-pub ahead of print] Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith J. P., Haddad E. V., Downey J. D., Breyer R. M., Boutaud O. (2010) PGE2 decreases reactivity of human platelets by activating EP2 and EP4. Thromb. Res. 126, e23–e29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bokoch G. M., Reed P. W. (1981) Evidence for inhibition of leukotriene A4 synthesis by 5,8,11,14-eicosatetraynoic acid in guinea pig polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 4156–4159 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldyne M. E., Burrish G. F., Poubelle P., Borgeat P. (1984) Arachidonic acid metabolism among human mononuclear leukocytes. Lipoxygenase-related pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 8815–8819 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patrignani P., Panara M. R., Greco A., Fusco O., Natoli C., Iacobelli S., Cipollone F., Ganci A., Créminon C., Maclouf J., et al. (1994) Biochemical and pharmacological characterization of the cyclooxygenase activity of human blood prostaglandin endoperoxide synthases. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 271, 1705–1712 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blobaum A. L., Marnett L. J. (2007) Molecular determinants for the selective inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 by lumiracoxib. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 16379–16390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith C. J., Zhang Y., Koboldt C. M., Muhammad J., Zweifel B. S., Shaffer A., Talley J. J., Masferrer J. L., Seibert K., Isakson P. C. (1998) Pharmacological analysis of cyclooxygenase-1 in inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 13313–13318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brenneis C., Maier T. J., Schmidt R., Hofacker A., Zulauf L., Jakobsson P. J., Scholich K., Geisslinger G. (2006) Inhibition of prostaglandin E2 synthesis by SC-560 is independent of cyclooxygenase 1 inhibition. FASEB J. 20, 1352–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong J., Bose M., Ju J., Ryu J. H., Chen X., Sang S., Lee M. J., Yang C. S. (2004) Modulation of arachidonic acid metabolism by curcumin and related beta-diketone derivatives: effects on cytosolic phospholipase A(2), cyclooxygenases and 5-lipoxygenase. Carcinogenesis 25, 1671–1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohd Aluwi M. F., Rullah K., Yamin B. M., Leong S. W., Abdul Bahari M. N., Lim S. J., Mohd Faudzi S. M., Jalil J., Abas F., Mohd Fauzi N., Ismail N. H., Jantan I., Lam K. W. (2016) Synthesis of unsymmetrical monocarbonyl curcumin analogues with potent inhibition on prostaglandin E2 production in LPS-induced murine and human macrophages cell lines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 26, 2531–2538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plummer S. M., Holloway K. A., Manson M. M., Munks R. J., Kaptein A., Farrow S., Howells L. (1999) Inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase 2 expression in colon cells by the chemopreventive agent curcumin involves inhibition of NF-kappaB activation via the NIK/IKK signalling complex. Oncogene 18, 6013–6020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jobin C., Bradham C. A., Russo M. P., Juma B., Narula A. S., Brenner D. A., Sartor R. B. (1999) Curcumin blocks cytokine-mediated NF-kappa B activation and proinflammatory gene expression by inhibiting inhibitory factor I-kappa B kinase activity. J. Immunol. 163, 3474–3483 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rouzer C. A., Tranguch S., Wang H., Zhang H., Dey S. K., Marnett L. J. (2006) Zymosan-induced glycerylprostaglandin and prostaglandin synthesis in resident peritoneal macrophages: roles of cyclo-oxygenase-1 and -2. Biochem. J. 399, 91–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brock T. G., McNish R. W., Bailie M. B., Peters-Golden M. (1997) Rapid import of cytosolic 5-lipoxygenase into the nucleus of neutrophils after in vivo recruitment and in vitro adherence. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 8276–8280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rhee S. H., Hwang D. (2000) Murine TOLL-like receptor 4 confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness as determined by activation of NF kappa B and expression of the inducible cyclooxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 34035–34040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raetz C. R. H., Garrett T. A., Reynolds C. M., Shaw W. A., Moore J. D., Smith D. C. Jr., Ribeiro A. A., Murphy R. C., Ulevitch R. J., Fearns C., Reichart D., Glass C. K., Benner C., Subramaniam S., Harkewicz R., Bowers-Gentry R. C., Buczynski M. W., Cooper J. A., Deems R. A., Dennis E. A. (2006) Kdo2-Lipid A of Escherichia coli, a defined endotoxin that activates macrophages via TLR-4. J. Lipid Res. 47, 1097–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.FitzGerald G. A. (2004) Coxibs and cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 1709–1711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu M., Ives D., Ramesha C. S. (1997) Synthesis of prostaglandin E2 ethanolamide from anandamide by cyclooxygenase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 21181–21186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kozak K. R., Crews B. C., Morrow J. D., Wang L. H., Ma Y. H., Weinander R., Jakobsson P. J., Marnett L. J. (2002) Metabolism of the endocannabinoids, 2-arachidonylglycerol and anandamide, into prostaglandin, thromboxane, and prostacyclin glycerol esters and ethanolamides. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 44877–44885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hermanson D. J., Gamble-George J. C., Marnett L. J., Patel S. (2014) Substrate-selective COX-2 inhibition as a novel strategy for therapeutic endocannabinoid augmentation. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 35, 358–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]