Abstract

Objective

To compare and contrast the efficacy and safety of patiromer and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS-9) in the treatment of hyperkalemia.

Design

A systematic review and meta-analysis of phase II and III clinical trial data was completed.

Patients or Participants

Eight studies (2 phase II and 4 phase III trials with 2 subgroup analyses) were included in the qualitative analysis whereas six studies (2 phase II and 4 phase III trials) were included in the meta-analysis.

Measurements and Results

There was significant heterogeneity in the meta-analysis with an I2 value ranging from 80.6–99.6%. A random-effects meta-analysis was applied for all endpoints. Each clinical trial stratified results by hyperkalemia severity and dosing; therefore, these were considered separate treatment groups in the meta-analysis. For patiromer, there was a significant −0.70mEq/L (95% confidence interval [CI] −0.48 to −0.91mEq/L) change in potassium at 4 weeks. At day 3 of patiromer treatment, potassium change was −0.36mEq/L (range of standard deviation: 0.07 to 0.30). The primary endpoint for ZS-9-- change in potassium at 48 hours-- was −0.67mEq/L (95% CI −0.45 to −0.89mEq/L). By 1 hour after ZS-9 administration, change in potassium was −0.17mEq/L (95% CI −0.05 to −0.30). Analysis of pooled adverse effects from these trials indicates that patiromer was associated with more gastrointestinal upset (7.6% constipation, 4.5% diarrhea) and electrolyte depletion (7.1% hypomagnesemia), whereas ZS-9 was associated with adverse effects of urinary tract infections (1.1%) and edema (0.9%).

Conclusion

Patiromer and ZS-9 represent significant pharmacologic advancements in the treatment of hyperkalemia. Both agents exhibited statistically and clinically significant reductions in potassium for the primary endpoint of this meta-analysis. Given the adverse effect profile and the observed time dependent effects, ZS-9 may play more of a role in treating acute hyperkalemia.

Keywords: hyperkalemia, patiromer, sodium zirconium cyclosilicate, ZS-9, sodium polystyrene sulfonate

Introduction

Treatment of hyperkalemia is complex and limited to a small number of available therapies. While the initial goal of therapy is to stabilize cardiac membranes to prevent arrhythmias and shift potassium to the intracellular space, the ultimate goal is to remove excess potassium from the body. Potassium removal therapies, sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS; Kayexalate) and loop diuretics are wrought with untoward adverse effects and ambiguous efficacy.1–7 To date, the single randomized clinical trial that has evaluated SPS for hyperkalemia demonstrated a limited evidence base for the safety and efficacy of currently available therapies.8 Additionally, patients at high risk for hyperkalemia are often those with disease states such as heart failure and chronic kidney disease that derive great benefit from renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi). This drug class is a major source of drug-induced hyperkalemia.9–13 Management of hyperkalemia in these patient populations often includes reduction or discontinuation of RAASi, which may have a negative impact on outcomes. Thus, there is a significant gap in the current treatment armamentarium for hyperkalemia.

Patiromer calcium sorbitex (patiromer) and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS-9) seek to fill the hyperkalemia treatment gap and overcome limitations to available therapies. These new oral agents are non-absorbed polymers that bind potassium in the gastrointestinal tract and facilitate fecal potassium removal from the body. Patiromer is marketed under the brand name Veltassa and was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in October 2015.14 Given its onset of 7–48 hours, patiromer was approved for chronic management of hyperkalemia and carries a warning that the drug is not be administered for emergency management of severe hyperkalemia. Alternatively, ZS-9 has a more rapid onset of 1–6 hours and is not currently FDA approved. In May 2016, the manufacturer announced that the FDA had issued a Complete Response Letter (CRL) regarding the New Drug Application because of initial FDA concerns about pre-approval manufacturing inspections.

Clinical trials for both patiromer and ZS-9 appear to provide evidence for efficacy in lowering potassium. Despite enrollment of several hundred patients per trial, the individual treatment groups had small numbers of patients because of stratification by hyperkalemia severity and dose administered. These small groups included varying patient populations and different underlying comorbidities across studies. The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to therefore determine treatment effect estimates for patiromer and ZS-9 at critical times post-dose from all available phase II and phase III clinical trials. This goal of this approach is to allow for a more robust comparison between these new agents.

Methods

Study Design

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to a standardized, pre-specified protocol and reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.15

All phase II and III clinical trials of patiromer or ZS-9 that were published in English were considered for inclusion in the systematic review. The minimum follow-up period was 4 weeks for patiromer and 48 hours for ZS-9 based on the pharmacology of each drug and the design of major clinical trials. Placebo-control was not an eligibility criterion, given the open-label nature of the initial phase of a majority of the clinical trials (most trials deemed an initial placebo-control to be unethical among patients with known hyperkalemia).

Literature Search and Selection

Pubmed, Embase, and Web of Science databases were queried for literature that included the terms “patiromer” or “Veltassa” or “sodium zirconium cyclosilicate” or “ZS-9” or “ZS9” or “SZC” from inception to 7/1/2016. References of selected studies were reviewed for additional literature.

Titles and abstracts of literature search results were independently screened by two authors and filtered for Phase II and III clinical trials. Studies were selected based on eligibility criteria defined above.

Data Extraction

Two endpoints were selected for each drug based on their pharmacologic characteristics and the available clinical trial endpoints. The endpoints were: patiromer (1) change in potassium at 4 weeks of treatment and (2) change in potassium at study day 3; ZS-9 (1) change in potassium at 48 hours of treatment and (2) change in potassium at 1 hour. Data were also collected regarding the frequency of patients maintained in the normal potassium range (defined by each study: 3.5–5.0mEq/L16, 17, 3.5–4.9mEq/L18, 19, 4.3–5.0mEq/L20, and 3.8mEq/L to <5.1mEq/L21) throughout the follow-up period and the frequency of patients able to maintain, initiate, or titrate RAASi. Safety data were also collected for each drug. Data were extracted from each study by reviewing the published study, appendices, and supplemental data. Data collection was done using a standardized database and independently completed by two authors.

Risk of bias was assessed according to the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials.22

Statistical Analysis

Treatment effects were defined as a change in serum potassium concentration from baseline. Summary measures for these continuous endpoints were mean differences and their associated 95% confidence intervals (CI). Based on available data, an estimate of the mean difference and range of standard deviation were assessed for the secondary endpoint of patiromer. The summary measures were compared between study groups as defined by the (1) severity of hyperkalemia (e.g. mild versus moderate) and (2) the dose of medication in that study arm. This stratification provided important differentiation between severity of hyperkalemia that is clinically relevant and provides interpretation of the dose-response for each drug. Frequency and percentage of maintenance of normokalemia, use of RAASi, and adverse effects were collated from each study and pooled into an aggregate occurrence rate.

Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic.23 Given high heterogeneity (I2>75%), a random-effects meta-analysis was applied to all endpoints because the random-effects method assumes heterogeneity exists across all studies.24 A sensitivity analysis was conducted using a fixed-effects model.

All tests were 2-tailed with a nominal level of significance set at <0.05. R statistical software was used for analysis (Vienna, Austria; https://www.R-project.org).

Results

Study Characteristics

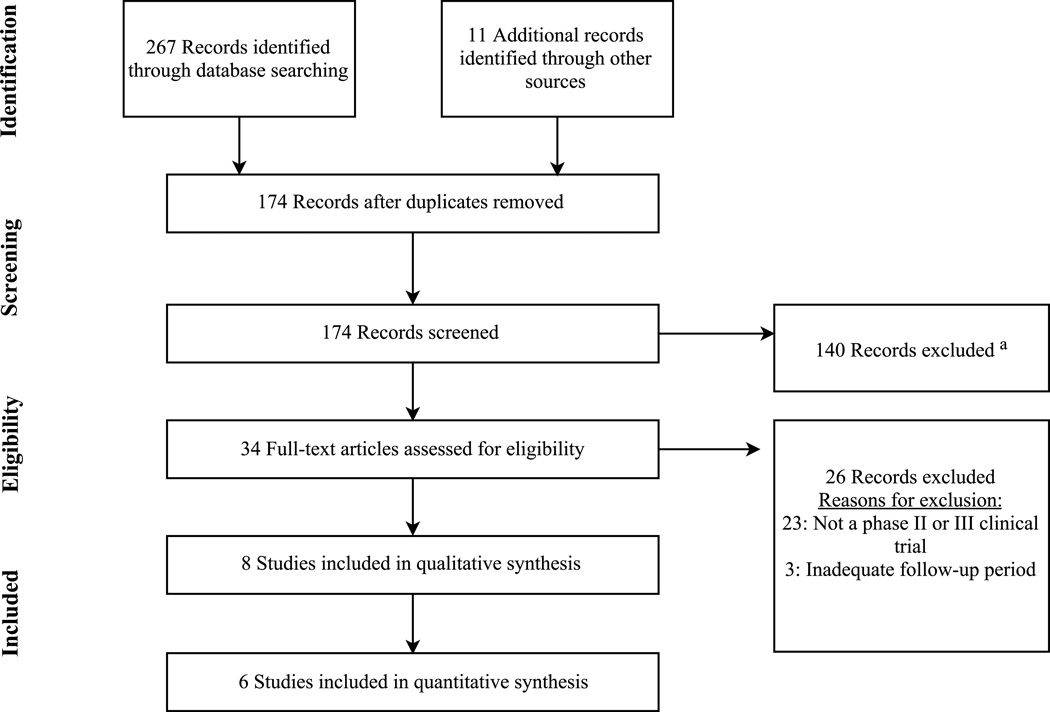

Figure 1 displays the study selection process. There were 3 clinical trials each included in the meta-analysis for patiromer (n=654)20, 21, 25 and ZS-9 (n=1,102)17–19. Two additional studies were included in the qualitative analysis for ZS-9 because the results were sub-group analyses or analyses of data combined from the other clinical trials.26, 27

Figure 1. Flow Diagram for Study Selection Process.

This flow diagram shows the results of the literature search, screening, and selection process according to the PRISMA statement. Other sources used to identify literature included review of the citation lists of applicable studies.

a At the screening phase, records were excluded because they were not evaluative studies of patiromer or ZS-9 (e.g. editorial, review, commentary, etc.), not conducted in humans, or not published in English.

Baseline characteristics for patients in the patiromer trials were a mean age of 65.8 years, mean serum potassium of 5.31mEq/L, and a mean estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 45.1ml/min/1.73m2. Among the patiromer patients, 93% had chronic kidney disease, 73% had type 2 diabetes mellitus, 48% had heart failure, and 86% were receiving concomitant RAASi therapy. The ZS-9 trials had similar baseline characteristics: the mean age was 65.7 years, mean serum potassium was 5.35mEq/L, and mean eGFR was 45.8ml/min/1.73m2. However, compared to the patiromer trials there was a lower prevalence of chronic kidney disease (66%), type 2 diabetes mellitus (61%), heart failure (39%), and concomitant use of a RAASi (67%) in the ZS-9 trials.

Risk of Bias and Study Heterogeneity

Three studies18, 19, 25 had 86% low risk of bias (14% unclear risk), two studies17, 20 had 57% high risk of bias (29% low risk, 14% unclear risk), and one study21 had 43% high risk of bias (29% low risk, 29% unclear risk). A majority of the high risk of bias was derived from the open-label nature of the initial phase of these studies. There was a low risk of outcome-level bias in all studies.

All six of the studies in the meta-analysis showed significant heterogeneity, with an I2 estimate ranging from 80.6–99.6%. This level of heterogeneity could be explained by differences in patient populations, underlying comorbidities, study design, and effect estimates.

Treatment Outcomes

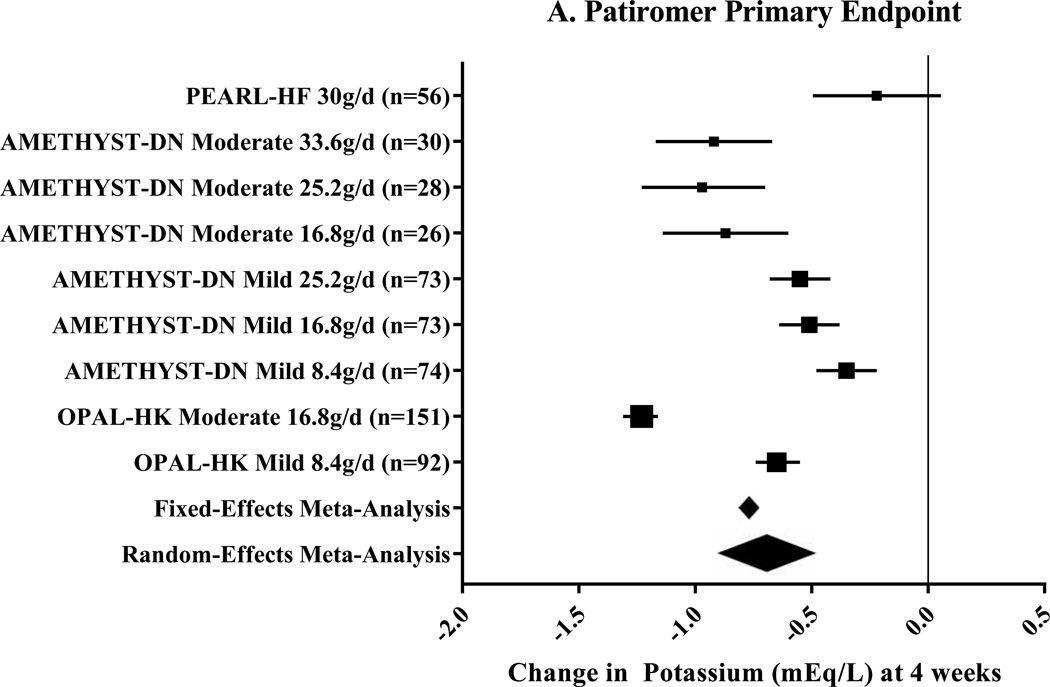

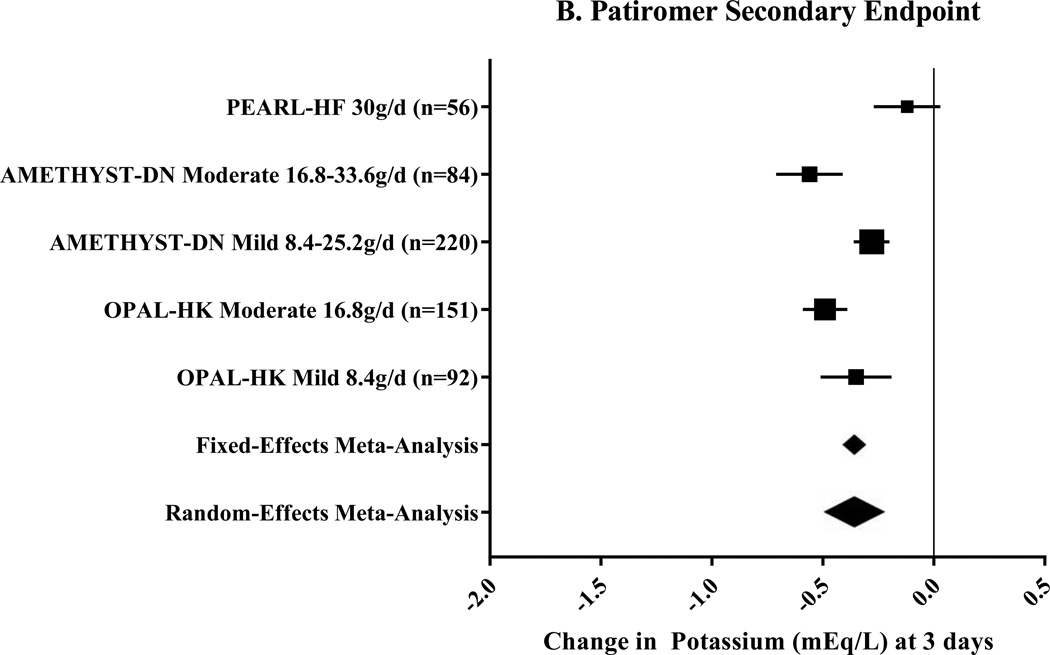

Three clinical trials, including nine pre-specified subgroups, were included for patiromer (Table 1).20, 21, 25 The primary endpoint of this meta-analysis, change in potassium at 4 weeks, was −0.70mEq/L (95% CI: −0.48 to −0.91mEq/L; n=603) using a random-effects meta-analysis (Figure 2A). The secondary endpoint, change in potassium at 3 days, was −0.36mEq/L (range of standard deviation: 0.07 to 30mEq/L; Figure 2B) using random-effects meta-analysis. Among 110 patients, 93% were able to maintain, initiate, or titrate RAASi during maintenance phases of the studies.21, 25 Additionally, during the maintenance phases, 74–95% of patients were maintained in the normal potassium range.20, 21, 25

Table 1.

Summary of Phase II and Phase III Clinical Trials Included in the Systematic Review for Patiromer and Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate (ZS-9)

| Study Design | Number of Patients | Study Treatment | Duration | Primary Endpoint Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEARL-HF25 Phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial |

n=105 | Patiromer 15g twice daily or placebo |

4 weeks | Mean difference in change in potassium at 4 weeks: −0.45mEq/L, P<0.001. |

| AMETHYST-DN20 Phase II, randomized, open-label, dose-ranging clinical trial |

n=306 | Patiromer 8.4–25.2g/day for mild hyperkalemia (K 5.1–5.5mEq/L) Patiromer 16.8–33.6g/day for moderate hyperkalemia (K 5.6–5.9mEq/L) |

52 weeks | Change in potassium at week 4: Ranged from −0.35mEq/L to −0.97mEq/L depending on dose and treatment group (P<0.001 for all) |

| OPAL-HK21 Phase III clinical trial with a single- group, single-blind initial treatment phase and a randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal phase |

n=243 initial phase n=107 maintenance phase |

Patiromer 8.4g/day for mild hyperkalemia (K 5.1–5.4mEq/L) Patiromer 16.8g/day for moderate hyperkalemia (K 5.5–6.4mEq/L) |

4 weeks initial phase 8 weeks maintenance phase |

Change in potassium at 4 weeks: − 1.01mEq/L (95% CI −0.95 to −1.07mEq/L, P<0.001) Between groups difference at 12 weeks: − 0.72mEq/L (95% CI −0.46 to −0.99mEq/L, P<0.001) |

| Phase II, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalating clinical trial18 |

n=90 | ZS-9 0.3g, 3g, or 10g three times daily with meals or placebo |

48 hours | Change in potassium at 48 hours: −0.92±0.52mEq/L with ZS-9 10g compared to −0.26±0.4mEq/L with placebo (P<0.001) |

| Phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, two-stage, dose- ranging clinical trial19 |

n=754 initial phase n=543 maintenance phase |

Initial phase: ZS-9 1.25–10g three times daily or placebo |

48 hours initial phase 14 days maintenance phase |

Change in potassium at 48 hours: Ranged from −0.16% to −0.30% for ZS-9 groups compared to −0.09% for placebo (P<0.001 for each comparison). |

| HARMONIZE17 Phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial |

n=258 initial phase n=237 maintenance phase |

ZS-9 10g three times daily initial phase ZS-9 5–15g/day or placebo maintenance phase |

48 hours initial phase 28 days maintenance phase |

Change in potassium at 48 hours: −1.1mEq/L (P<0.001). |

|

a Combined sub-group analysis of patients with severe hyperkalemia (K ≥6.0mEq/L) from the ZS-9 the phase III trials27 |

n=45 | ZS-9 10g once | 4 hours | Change in potassium at 1 hour: −0.4mEq/L (95% CI: −0.2 to 0.5mEq/L, P<0.001). 52% of patients achieved potassium < 5.5mEq/L by 4 hours. |

|

a Sub-group analysis of patients with heart failure from HARMONIZE trial26 |

n=97 | ZS-9 10g three times daily initial phase ZS-9 5–15g/day or placebo maintenance phase |

48 hours initial phase 28 days maintenance phase |

Change in potassium at 48 hours: −1.2mEq/L (P<0.001). |

These two studies were not included in the quantitative analysis given that their data is derived from the phase III trials of ZS-9 that are already included in the meta-analysis.

Abbreviations: AMETHYST-DN = Patiromer in the Treatment of Hyperkalemia in Patients With Hypertension and Diabetic Nephropathy; CI = confidence interval; g = gram; HARMONIZE = The Hyperkalemia Randomized Intervention Multidose ZS-9 Maintenance study; K = potassium; mEq/L = milliequivalents per liter; n = number of patients; OPAL-HK = Two-Part, Single-Blind, Phase 3 Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Patiromer for the Treatment of Hyperkalemia; P = p-value; PEARL-HF = Evaluation of Patiromer in Heart Failure Patients; ZS-9 = sodium zirconium cyclosilicate

Figure 2. Meta-Analysis Results for Patiromer Clinical Trials.

These Forest plots indicate the mean difference (black box) with 95% confidence interval (horizontal bars) for the meta-analysis effect estimates. The primary endpoint, change in potassium at 4 weeks, is displayed in Panel A. Heterogeneity was I2=97.3%. Change in potassium at study day 3 was the secondary endpoint as shown in Panel B. Heterogeneity for this endpoint was I2=99.6%. The range for the meta-analytic effect estimates (for both fixed- and random-effects) in Panel B represent the range of standard deviation.

g/d=grams per day; Mild=Mild hyperkalemia (potassium 5.1–5.5mEq/L20 or 5.1–5.4mEq/L21); Moderate=Moderate hyperkalemia (potassium 5.6–5.9mEq/L20 or 5.5–6.4mEq/L21).

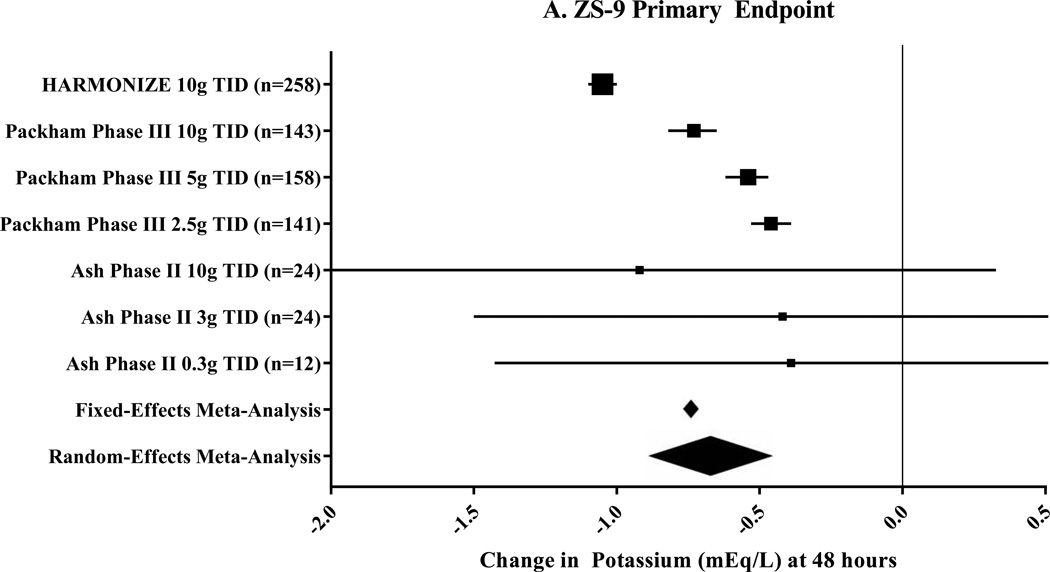

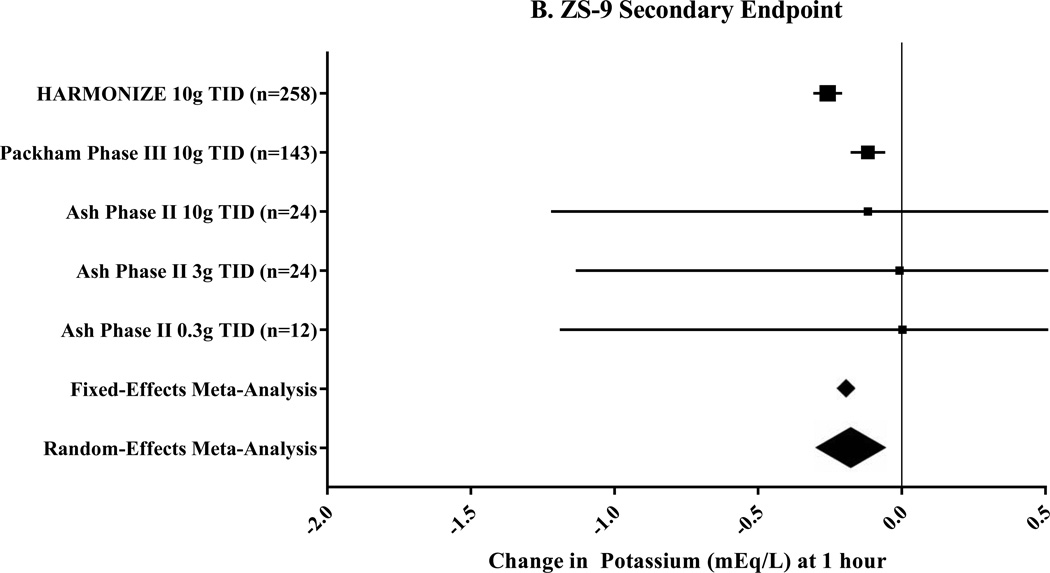

Three clinical trials that included seven pre-specified subgroups were included for ZS-9 (Table 1).17–19 The primary endpoint, change in potassium at 48 hours, was −0.67mEq/L (95% CI: −0.45 to −0.89mEq/L; n=760) by random-effects meta-analysis (Figure 3A). In a sub-group analysis of patients with heart failure, the mean change in potassium at 48 hours was −1.2mEq/L following ZS-9 dosed at 10g thrice daily.26 The secondary endpoint, change in potassium at 1 hour, was −0.17mEq/L (95% CI: −0.05 to −0.30mEq/L; Figure 3B) by random-effects meta-analysis. A sub-analysis of 45 patients with severe hyperkalemia (baseline serum potassium 6.1–7.2mEq/L) showed a reduction in potassium of −0.4mEq/L (95% CI: −0.2 to −0.5mEq/L) at 1 hour following a 10g dose of ZS-9.27 In the one trial, 71–85% of patients were maintained in the normal potassium range by the end of the 4-week randomized phase.17 No trial reported the number of patients able to maintain, titrate, or initiate RAASi therapy.

Figure 3. Meta-Analysis Results for Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate (ZS-9) Clinical Trials.

These Forest plots indicate the mean difference (black box) with 95% confidence interval (horizontal bars) for the meta-analysis effect estimates. Change in potassium at 48 hours was the primary endpoint shown in Panel A and had a heterogeneity of I2=98.3%. The secondary endpoint was change in potassium at 1 hour with a heterogeneity of I2=80.6%.

g=gram; TID=three times per day; ZS-9=sodium zirconium cyclosilicate.

Adverse Effects

Table 2 displays the pooled clinical trial results of the most common adverse effects.17–21, 25 Gastrointestinal adverse effects and electrolyte abnormalities were most common in patiromer-treated patients.. No serious gastrointestinal effects occurred in any patient on patiromer or ZS-9. Discontinuation of therapy due to an adverse effect occurred in 8% (43/538) of patients on patiromer and 1% (5/479) of patient on ZS-9 during maintenance phases of the trials.

Table 2.

Pooled Adverse Events for Patiromer and Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate (ZS-9) Reported from Phase II and III Clinical Trials

| Adverse Effects | Patiromer (n=660)20, 21, 25 |

ZS-9 (n=1393)17–19 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | Constipation | 50 (7.6%) | 16 (1.1%) |

| Diarrhea | 30 (4.5%) | 22 (1.6%) | |

| Nausea | 10 (1.5%)a | 12 (0.9%)b | |

| Vomiting | 2 (0.3%)c | 10 (0.7%)b | |

| Electrolyte Abnormalities |

Hypokalemiad | 30 (4.5%) | 13 (0.9%) |

| Hypomagnesemiae | 47 (7.1%)f | Not reported | |

| Miscellaneous | Urinary tract infection |

Not reported | 16 (1.1%) [not reported in HARMONIZE17] |

| Edema | Not reported | 12 (0.9%) | |

Data displayed as n (%)

Trials with multiple phases were considered separate for purposes of pooling adverse event data.17, 19, 21 For example, in OPAL-HK, 243 patients were in the initial phase and 107 (55 on patiromer) were in the randomized phase. Therefore, this trial contributed 298 patients to analysis of pooled adverse events for patiromer.

Reported in n=29821

Reported in n=5625

P<0.05 for comparison with placebo

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, patiromer and ZS-9 exhibited consistent and clinically relevant reductions in serum potassium among at-risk patient populations. Each agent appears to have a favorable short-term safety profile from available data. The diversity among the study quality was predominantly the result of an open-label initial treatment phase.

In this study, patiromer demonstrated a significant reduction in potassium at 3 days and 4 weeks of treatment by random-effects meta-analysis. These results were confirmed by a sensitivity analysis with a fixed-effects model (Figure 2). This is consistent with current product labeling for the use of patiromer in the maintenance of normokalemia. The degree of potassium reduction may be dependent on the severity of baseline hyperkalemia. The AMETHYST-DN trial showed a greater reduction in potassium in patients with moderate hyperkalemia (−0.97mEq/L) compared to mild hyperkalemia (−0.55mEq/L; Figure 2A) despite receiving the same daily dose of patiromer (12.6g).20The patiromer clinical trials demonstrated consistent efficacy through 12 and 52 week follow-up periods, although the 52-week period was open-label and not placebo controlled.20, 21 Normokalemia was maintained in 77%–95% of follow-up visits over 52 weeks20 and RAASi therapy was able to be continued in 94% of patiromer-treated patients after 12 weeks.21 The major caveat to these data is that twice daily patiromer dosing was utilized in these trials, whereas the FDA- approved dose is once daily. This change stemmed from concern over the drug interaction potential of patiromer. Additionally, a phase I trial showed that fecal potassium excretion was similar between patiromer regimens dosed at 8.4g thrice daily (1550±519mg), 12.6g twice daily (1419±550mg), and 25.2g once daily (1283±530mg; P=0.37).28 Confirmatory post-marketing studies are warranted. There is a concern regarding drug-drug interactions, as patiromer has the potential to bind other medication in the gastrointestinal tract based on in vitro binding studies.14, 29 Although not an exhaustive list, medications that have shown a reduction in bioavailability when co-administered with patiromer include trimethoprim, clopidogrel, amlodipine, cinacalcet, metoprolol, furosemide, levothyroxine, metformin, and ciprofloxacin.30 Other medications must be separated from patiromer administration by at least 3 hours according to updated recommendations from November 2016. This unwieldly administration schedule may have an impact on adherence in a patient population likely to be on multiple medications. Patiromer was also studied for the treatment of acute hyperkalemia with a mean potassium reduction of −0.21mEq/L and a 7 hour onset of action.16 These results demonstrated that it is not advisable to use patiromer for acute management of hyperkalemia.14

Gastrointestinal adverse effects were more common with patiromer than ZS-9 (Table 2), likely the result of sorbitol in the patiromer formulation. However, an 8.4g dose of patiromer contains approximately 4g of sorbitol, compared to 20g of sorbitol in a 15g dose of sodium polystyrene sulfonate.31 No severe gastrointestinal adverse effects were observed in the n=660 patients in the safety analysis. Given the rare occurrence of these events with sodium polystyrene sulfonate, a larger sample size is necessary to rule out serious gastrointestinal adverse effects such as intestinal necrosis with patiromer. Hypomagnesemia occurred in 7.1% of patients on patiromer, reflective of its non-selective nature for the potassium ion. More frequent laboratory monitoring of magnesium concentrations and patient education regarding the symptoms of hypomagnesemia (muscle weakness/cramping, nystagmus, and numbness) are warranted. Hypomagnesemia can be managed with oral supplementation, but should not be administered within 3 hours of patiromer. Caution should be used when lowering the potassium concentration in patients with heart failure and/or CKD because values lower than 4.0mEq/L may be associated with increased mortality.32, 33 Hypokalemia occurred in 4.7% of patients receiving patiromer, but these studies defined hypokalemia as a potassium concentration lower than 3.5mEq/L.20, 21, 25

This study demonstrated that ZS-9 exhibits a quick and reliable reduction in potassium. With an onset of 1 hour, ZS-9 may play a more significant role in the treatment of acute hyperkalemia than patiromer. The meta-analysis effect estimate for potassium reduction at 1 hour was −0.17mEq/L but data was only available from 5 of the 7 treatment groups (Figure 3B). The clinical significance of this finding is unknown as a potassium reduction of −0.17mEq/L may not translate to clinically apparent effects. However, in a separate analysis of the phase III trials17, 19, 52% of patients reached a potassium ≤5.5mEq/L within 4 hours and the mean potassium reduction was −0.4mEq/L at 1 hour which is greater than our meta-analysis effect estimate.27 This difference could be because the analysis was of a small subgroup (n=45) that had severe hyperkalemia (potassium 6.1–7.2mEq/L) treated with 10g of ZS-9, whereas our meta-analysis included 0.3g, 3g, and 10g doses with a baseline potassium of 5.35mEq/L. There may also be a potassium concentration dependent efficacy, whereby the higher baseline serum potassium concentration leads to a more pronounced potassium lowering effect. While sodium polystyrene sulfonate has long been the only FDA-approved potassium removal agent available, its use in acute hyperkalemia is complicated by a variable onset of action (2–6 hours), a variable duration of action (6–24 hours), lack of robust efficacy data, and concerns for serious adverse events.1–3 Efficacy data for acute hyperkalemia are elusive and placebo-controlled interventions unlikely given ethical considerations. In comparison to SPS, our results indicate that ZS-9 has potential role in the management of acute hyperkalemia given its 1 hour onset of action, robust efficacy data (Figure 3), and mild adverse effect profile. On the other side of the coin, short trial durations of 2–28 days limit the ability to use ZS-9 in the long-term setting as is the case with patiromer. An 11-month extension to the HARMONIZE trial was recently completed and will provide critical long-term data (NCT02107092, clinicaltrials.gov) as will an additional 12-month trial that is currently underway (NCT02163499, clinicaltrials.gov).

ZS-9 was associated with less frequent GI effects compared to patiromer with rates similar to those observed in placebo groups. This difference may be due to the inorganic lattice structure of ZS-9 that doesn’t swell in gastric juices.34 In addition, there were no reported cases of hypomagnesemia in patients receiving ZS-9, and hypokalemia occurred less often. These differences are likely the result of higher specificity of ZS-9 for the potassium ion compared to patiromer which displays non-specific binding and can also bind magnesium. A few adverse effects, such as urinary tract infections, QTc interval prolongation, and edema, occurred exclusively in patients receiving ZS-9. Although QTc interval prolongation is a concerning adverse event, it is an expected physiologic effect of quickly lowering the extracellular potassium concentration. Additionally, the changes observed were clinically insignificant (0.03–10.3msec increase), and there were no differences in the rate of arrhythmias between ZS-9 and placebo groups.19 There has been some concern surrounding ZS-9 due to the sodium content of a 10g dose (approximately 1000mg) leading to edema and/or hypertension. It’s important to note that sodium polystyrene sulfonate contains 1500mg of sodium per 15g dose and that rates of edema and hypertension were low in ZS-9 trials (<1%).

The clinical trials for ZS-9 and patiromer included many patients with chronic kidney disease, heart failure, and diabetes mellitus. There were no discernable differences in the safety or efficacy of patiromer and ZS-9 for these subgroups. Nonetheless, certain special populations that are at high risk of hyperkalemia or complications from treatment were largely excluded from trials and should be the focus of further research. These include patients on dialysis, renal transplant recipients, patients with gastrointestinal disorders, and post-surgical patients. Practitioners should be highly cautious to use ZS-9 or patiromer in these patients given the lack of safety and efficacy data.

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS) has been the lone treatment option for hyperkalemia for over 50 years. Use of SPS is wrought with untoward gastrointestinal (GI) effects ranging from nausea and diarrhea to mucosal damage and intestinal necrosis.4–6 SPS can also cause hypernatremia, hypocalcemia, and hypomagnesemia. The initial study of SPS in 1961 included 32 hyperkalemic patients with no control group.35 A recent randomized, placebo-controlled study in 33 CKD patients with mild hyperkalemia demonstrated efficacy of SPS with a mean serum potassium reduction of −1.04mEq/L (95% CI: −0.71 to −1.37mEq/L) after 7 days of treatment compared to placebo.8 However, the small sample size, mild degree of hyperkalemia and short duration leave many unanswered questions. With unknown efficacy and well-known toxicities, clinicians have struggled to manage hyperkalemia with SPS.2, 7 Compared to SPS, patiromer appears to have improved long-term tolerability with no reports of serious gastrointestinal adverse effects, but a longer onset of action and concern for drug-drug interactions. Also compared to SPS, ZS-9 has a more rapid onset of effect and very few adverse effects, but long-term data are limited. Both patiromer and ZS-9 have multiple well designed randomized controlled trials supporting their efficacy for which SPS is lacking.

Our study has several possible limitations. Publication bias is always a consideration in systematic reviews, but that is minimized with this study given our focus on phase II and III clinical trials. An Egger’s test was not performed due to the small number of trials included in the meta-analysis.36 The quality of studies was adequate but a number of them included open-label phases that introduce a high risk of bias. These initial treatment phases are unlikely to be avoided given the ethical concern of giving a patient with hyperkalemia a placebo. Additionally, the outcome of change in potassium concentration is standardized and objective, mitigating the risk of bias in outcome assessment. There was significant heterogeneity (I2>75%) for each endpoint assessed by meta-analysis and therefore a random-effects meta-analysis was applied.24, 37, 38 This heterogeneity is likely derived from the bias as discussed above and the differences in study population that included a variety of disease states, geographic regions, baseline potassium concentrations, and doses of the agents used. Another limitation is the lack of clinical outcomes assessed in the phase II and III clinical trials. Future trials should include outcomes such as hyperkalemia associated arrhythmias, morbidity, and mortality.

Despite these limitations, this study has several implications. This meta-analysis of well conducted phase II and III clinical trials provides a higher level of evidence than individual clinical trials by providing an estimate of the overall pooled effect size with optimal accuracy and precision.37, 39 This meta-analysis delineates ZS-9 as a potential new agent for treatment of acute hyperkalemia when compared to patiromer given its 1-hour onset of effect and data from the subgroup study of severe hyperkalemia.27 However, baseline potassium concentrations were mildly elevated and similar between patiromer (5.31mEq/L) and ZS-9 (5.35mEq/L) trials and do not necessitate acute treatment. A randomized controlled trial directly comparing ZS-9, patiromer, and SPS would be necessary to test this hypothesis. Precise effect estimates are provided for clinically relevant time periods (e.g. 1 hour, 2 days, 3 days, and 4 weeks) and are stratified by varying degrees of hyperkalemia and doses of each agent. These results are corroborated by the fixed-effects sensitivity analysis. The point estimates were similar between the random-effects and fixed-effects models indicating a robust primary analysis. Lastly, this study identifies several areas for further research: post-marketing surveillance for rare but serious gastrointestinal adverse effects, once daily patiromer dose response, long-term efficacy data for ZS-9, and use of these agents in special populations.

Conclusion

This study provides precise effect estimates for the potassium reduction of patiromer sorbitex calcium and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate. These agents are a significant advancement in our armamentarium for the treatment of hyperkalemia. Compared to sodium polystyrene sulfonate, these drugs are more selective for the potassium ion34, exhibit an improved adverse event profile, and result in a more consistent potassium lowering effect. Differences between patiromer and ZS-9 include time to onset of effect, adverse event profiles, and drug interactions. While the clinical niche for these drugs remains to be seen, patiromer appears more likely to play more of a role in the chronic management of hyperkalemia whereas ZS-9 may be better suited for acute therapy.

Table 3.

Classification of Baseline Potassium Concentration for Patients on Patiromer and Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate (ZS-9) in Phase II and III Clinical Trials

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Trial | n (%) | Potassium Range |

n (%) | Potassium Range |

n (%) | Potassium Range |

| AMETHYST-DN (n=306)20 Patiromer |

222 (72.5%) | 5.1–5.5mEq/L | 84 (27.5%) | 5.6–5.9mEq/L | NA | NA |

| OPAL-HK (n=243)21 Patiromer |

92 (37.9%) | 5.1–5.4mEq/L | 151 (62.1%) |

5.5–6.4mEq/L | NA | NA |

| Phase III ZS-9 (n=754)19 ZS-9 |

427 (56.6%) | 5.0–5.3mEq/L | 152 (20.2%) |

5.4–5.5mEq/L | 174 (23.1%) | 5.6–6.5mEq/L |

| HARMONIZE (n=258)17 ZS-9 |

119 (46.1%) | <5.5mEq/L | 100 (38.8%) |

5.5–5.9mEq/L | 39 (15.1%) | ≥6mEq/L |

| PEARL-HF (n=105)25 Patiromer |

No stratification by hyperkalemia severity. Mean baseline potassium concentration was 4.69mEq/L for the patiromer group (n=56) |

|||||

| Phase II ZS-9 (n=90)18 ZS-9 |

No stratification by hyperkalemia severity. Mean ± standard deviation baseline potassium concentration was 5.2±0.3mEq/L, 5.0±0.3mEq/L, and 5.1±0.4mEq/L for the 0.3g, 3g, and 10g dose groups, respectively. |

|||||

Baseline potassium concentration was from the initial phase for trials with multiple phases.

AMETHYST-DN = Patiromer in the Treatment of Hyperkalemia in Patients With Hypertension and Diabetic Nephropathy; g = grams; HARMONIZE = The Hyperkalemia Randomized Intervention Multidose ZS-9 Maintenance study; mEq/L = milliequivalents per liter; n = number of patients; NA = not applicable; OPAL-HK = Two-Part, Single-Blind, Phase 3 Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Patiromer for the Treatment of Hyperkalemia; PEARL-HF = Evaluation of Patiromer in Heart Failure Patients; ZS-9 = sodium zirconium cyclosilicate

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award Number UL1TR001412. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Mario V. Beccari was a Doctor of Pharmacy Student at the University at Buffalo School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences during the completion of this manuscript.

A portion of the NIH 1UL1TR001412-01 Buffalo Clinical and Translational Research Center Grant Award was used to complete this study.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no actual or potential conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Emmett M, Hootkins RE, Fine KD, Santa Ana CA, Porter JL, Fordtran JS. Effect of three laxatives and a cation exchange resin on fecal sodium and potassium excretion. Gastroenterology. 1995;3:752–760. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90448-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sterns RH, Rojas M, Bernstein P, Chennupati S. Ion-exchange resins for the treatment of hyperkalemia: are they safe and effective? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:733–735. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010010079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gruy-Kapral C, Emmett M, Santa Ana CA, Porter JL, Fordtran JS, Fine KD. Effect of single dose resin-cathartic therapy on serum potassium concentration in patients with end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;10:1924–1930. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9101924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng ES, Stringer KM, Pegg SP. Colonic necrosis and perforation following oral sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Resonium A/Kayexalate in a burn patient. Burns. 2002;2:189–190. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(01)00099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerstman BB, Kirkman R, Platt R. Intestinal necrosis associated with postoperative orally administered sodium polystyrene sulfonate in sorbitol. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992;2:159–161. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harel Z, Harel S, Shah PS, Wald R, Perl J, Bell CM. Gastrointestinal adverse events with sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) use: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2013;3:264 e9–264.e24. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watson M, Abbott KC, Yuan CM. Damned if you do, damned if you don't: potassium binding resins in hyperkalemia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;10:1723–1726. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03700410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lepage L, Dufour AC, Doiron J, et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate for the Treatment of Mild Hyperkalemia in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;12:2136–2142. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03640415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ben Salem C, Badreddine A, Fathallah N, Slim R, Hmouda H. Drug-induced hyperkalemia. Drug Saf. 2014;9:677–692. doi: 10.1007/s40264-014-0196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmer BF. Managing hyperkalemia caused by inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. The New England journal of medicine. 2004;6:585–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perazella MA. Drug-induced hyperkalemia: old culprits and new offenders. Am J Med. 2000;4:307–314. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00496-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney international. 2013:1–150. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;16:e240–e327. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh S, Lata S, Tiwari KN. Antioxidant potential of Phyllanthus fraternus Webster on cyclophosphamide induced changes in sperm characteristics and testicular oxidative damage in mice. Indian J Exp Biol. 2015;10:647–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;4:264–269. W64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bushinsky DA, Williams GH, Pitt B, et al. Patiromer induces rapid and sustained potassium lowering in patients with chronic kidney disease and hyperkalemia. Kidney international. 2015;6:1427–1433. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kosiborod M, Rasmussen HS, Lavin P, et al. Effect of sodium zirconium cyclosilicate on potassium lowering for 28 days among outpatients with hyperkalemia: the HARMONIZE randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2014;21:2223–2233. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ash SR, Singh B, Lavin PT, Stavros F, Rasmussen HS. A phase 2 study on the treatment of hyperkalemia in patients with chronic kidney disease suggests that the selective potassium trap, ZS-9, is safe and efficient. Kidney international. 2015;2:404–411. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Packham DK, Rasmussen HS, Lavin PT, et al. Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate in hyperkalemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;3:222–231. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakris GL, Pitt B, Weir MR, et al. Effect of Patiromer on Serum Potassium Level in Patients With Hyperkalemia and Diabetic Kidney Disease: The AMETHYST-DN Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama. 2015;2:151–161. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weir MR, Bakris GL, Bushinsky DA, et al. Patiromer in Patients with Kidney Disease and Hyperkalemia Receiving RAAS Inhibitors. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;3:211–221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;7414:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;3:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pitt B, Anker SD, Bushinsky DA, Kitzman DW, Zannad F, Huang IZ. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of RLY5016, a polymeric potassium binder, in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with chronic heart failure (the PEARL-HF) trial. European heart journal. 2011;7:820–828. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anker SD, Kosiborod M, Zannad F, et al. Maintenance of serum potassium with sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS-9) in heart failure patients: results from a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. European journal of heart failure. 2015;10:1050–1056. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kosiborod M, Peacock WF, Packham DK. Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate for Urgent Therapy of Severe Hyperkalemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;16:1577–1578. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1500353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Epstein M, Palmer B, Mayo M, et al. Mechanism of action of patiromer for oral suspension: Increases fecal K+ excretion in healthy subjects independent of race (Abstract) World Congress of Nephrology. 2015 Available at http://wcn15mtapcr/sessions/view/112297. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Dycke KC, Nijman RM, Wackers PF, et al. A day and night difference in the response of the hepatic transcriptome to cyclophosphamide treatment. Arch Toxicol. 2015;2:221–231. doi: 10.1007/s00204-014-1257-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Veltassa (Patiromer) for Oral Suspension: Drug-Drug Interactions [Written Communication] 2016 "Personal Communication". [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montaperto AG, Gandhi MA, Gashlin LZ, Symoniak MR. Patiromer: a clinical review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;1:155–164. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1106935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kjeldsen K. Hypokalemia and sudden cardiac death. Experimental and clinical cardiology. 2010;4:e96–e99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowling CB, Pitt B, Ahmed MI, et al. Hypokalemia and outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure and chronic kidney disease: findings from propensity-matched studies. Circulation Heart failure. 2010;2:253–260. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.899526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stavros F, Yang A, Leon A, Nuttall M, Rasmussen HS. Characterization of structure and function of ZS-9, a K+ selective ion trap. PLoS One. 2014;12:e114686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scherr L, Ogden DA, Mead AW, Spritz N, Rubin AL. Management of hyperkalemia with a cation-exchange resin. The New England journal of medicine. 1961:115–119. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196101192640303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;7109:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;Pt A:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;11:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burns PB, Rohrich RJ, Chung KC. The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;1:305–310. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318219c171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]