Abstract

Background

Management of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) larger than 5 cm is still debated. The aim of our study was to compare morbidity and mortality after the surgical resection of HCC according to the nodule size.

Methods

Since 2001, 429 liver resections for HCC were performed in our institution. We divided the cohort into two groups, 88 patients in group 1 patients with HCC diameter from 5 to 10 cm and 39 patients in group 2 with HCC diameter ≥10 cm.

Results

In 30.7% of cases in the first group and in 35.9% of cases in the second group the HCC grew into a healthy liver. A major liver resection was performed in 36.3% of cases in group 1 vs. 66.6% in group 2 (P=0.001). In two cases for the first group and in ten cases in the second group a laparoscopic approach was performed. Median operative time was higher in group 2 (P=0.001). The median post-operative hospital stay was similar in the two groups (P=0.897). The post-operative morbidity was not different between the two groups (P=0.595).

Conclusions

The tumour size does not contraindicate a surgical resection of HCC even in patient with HCC ≥10 cm.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), liver surgery, giant, resection, 5 cm, 10 cm

Introduction

The management of giant hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ≥5 cm in diameter is still debated and data on the management are limited (1,2). If HCC lesions larger than 5 cm continues to be debated, few data are available regarding giant HCC (≥10 cm) (3-5), and are in most cases retrospective. An unfavourable prognosis in which morbidity rates range from 25% to 50% and mortality rates from 0% to 8% are described in patients with lesions of ≥10 cm, these patients are often deemed to be non-amenable to surgery (6-8). According with the BCLC staging classification, those patients are classified as intermediate stage BCLC-B and should be treated with locoregional treatment. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) has been reported to be feasible in the treatment of giant HCC but did not improve surgical outcome (9).

On the other hand, several individual centres, suggesting that tumour size is not critical and those physiological parameters and the characteristics of the liver remnant are the main determinants of treatment outcomes (10). Liver resection may be the only chance of cure in these patients; even surgery should probably be considered as first line therapy.

The aim of our study was to compare morbidity and mortality after the surgical resection of HCC according to the nodule size.

Methods

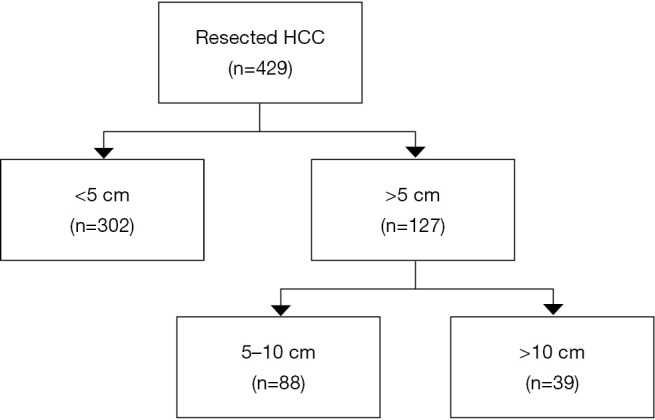

Since 2001 a prospective database was started in our institution, we performed 429 liver resections for HCC. Of them 127 patients with HCC nodule diameter ≥5 cm were enrolled in this study. We divided the cohort into two groups, group 1 patients with HCC diameter from 5 to 10 cm and group 2 patients with HCC diameter ≥10 cm (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) resection according with the nodule size.

Baseline characteristic, intra-operative parameters and post-operative outcomes were compared between the two groups. Outcomes of particular interest were post-operative morbidity and mortality, operation time, blood loss, transfusion rate, post-operative liver function, hospital stay and survival. Surgical complications were classified as described by Dindo and colleagues (11).

Surgical procedures

All surgical procedures were performed by senior surgeon specialized in hepato-biliary surgery. The open approach was routinely performed with a bilateral subcostal or a J-shaped incision. Abdominal cavity was inspected to exclude disease progression. Ultrasonography was routinely performed to verify the morphology and location of tumors and to control both left and right hepatic hemilivers. A parenchymal-sparing policy was adopted when possible. We used the same surgical approach in case of right hepatectomy for HCC (12). Laparoscopic approach was performed as previously described (13).

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed with statistical software (SPSS, version 22.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± interquartile range and compared using Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test as appropriate. Qualitative variables were expressed as number and percentage and compared using Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Statistical significance was defined by P≤0.05.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

In group 1, we had 88 patients with HCC from 5 to 10 cm. In group 2, 39 patients were included with HCC nodule over 10 cm. In group 1 we observed a 84% of male, and 71.8% in group 2. Mean age was 65.8 years in group 1 and 66.6 years in group 2 (P=0.272). Body Mass Index was similar for each group, 26.4 for group 1 and 25 for group 2. In group 1, three patients were classified as Child B (3.4%), in group 2 all patients were Child A. The median MELD score was 7 (IQR 6–7) and 8 (IQR 7–8) respectively for group 1 and 2.

The HCC nodule was associated with an underlying liver disease with similar rates in the two groups. In 17% and 17.9% for HBV infection for group 1 and 2 respectively; in 43.2% and 30.8% for HCV infection; in 4.5% and 7.7% for alcohol. In 30.7% of cases in the first group and in 35,9% of cases in the second group the HCC grew into a healthy liver. The was no difference between the two groups (P=0.546).

The median baseline alpha fetoprotein trend was higher in the group 2, 21 UI (IQR 2.5–281) in group 1 versus 182 UI (IQR 12.5–1,710) in group 2 (P=0.071). All patients’ characteristics are resumed in Table 1.

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics.

| Characteristics | Group 1: ≥5 and <10 cm [88] | Group 2: ≥ 10 cm [39] | Total [127] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years mean (range) | 65.8 (35.0–86.0) | 66.6 (38.0–89.0) | 65.5 (35.0–89.0) | 0.272 |

| BMI, mean (range) | 26.4 (15.7–36.3) | 25 (20.2–36.1) | 25.9 (15.7–36.3) | 0.336 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.146 | |||

| Male | 74 (84.0) | 28 (71.8) | 102 (80.3) | |

| Female | 14 (16.0) | 11 (28.2) | 25 (19.7) | |

| Child-Pugh class, n (%) | 0.552 | |||

| A | 85 (96.6) | 39 (100.0) | 124 (97.6) | |

| B | 3 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.4) | |

| MELD score, median (IQR) | 7 (6.0–7.0) | 8 (7.0–8.0) | 8 (7.0–8.0) | 0.449 |

| Underlying aetiology, n (%) | 0.546 | |||

| HBV | 15 (17.0) | 7 (17.9) | 22 (17.3) | |

| HCV | 38 (43.2) | 12 (30.8) | 50 (39.4) | |

| Alcoholic | 4 (4.5) | 3 (7.7) | 7 (5.5) | |

| Cryptogenic | 2 (2.3) | 3 (7.7) | 5 (3.9) | |

| Toxic | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.6) | |

| Healthy liver | 27 (30.7) | 14 (35.9) | 41 (32.3) | |

| Alpha fetoprotein (U/L), median (IQR) | 21 (2.5–281.0) | 182 (12.5–1,710.0) | 31 (6.0–798.0) | 0.071 |

Surgical finding

A major liver resection was performed in 36.3% of cases in group 1 vs. 66.6% in group 2 (P=0,001). In two cases for the first group and in ten cases in the second group a laparoscopic approach was performed. We used in a same rate the pedicle clamping, 21.5% in group 1 and 17.9% in group 2. In group 2 the median estimated blood loss was higher 275 mL (IQR 200–650) vs. 200 mL (IQR 100–300) in group 1 (P=0.001). According to this results the blood transfusion was higher in group 2: 20.5% vs. 6,8% (P=0.029). Median operative time was higher in group 2 with 254 min (IQR 233.5–320) vs. 217.5 min (IQR 160–270) in group 1 (P=0.001). The surgical findings are resumed in Table 2.

Table 2. Surgical procedures.

| Surgery | Group 1 ≥5 and <10 cm [88] | Group 2 ≥10 cm [39] | Total [127] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major hepatectomy, n (%) | 32 (36.3) | 26 (66.6) | 58 (45.6) | 0.001 |

| Laparoscopic (VLS) | 2 | 10 | 12 | 0.341 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL), median (IQR) | 200 (100.0–300.0) | 275 (200.0–650.0) | 200 (100.0–300.0) | 0.001 |

| Transfusion, n (%) | 6 (6.8) | 8 (20.5) | 14 (11.0) | 0.029 |

| Operative time (min), median (IQR) | 217.5 (160.0–270.0) | 254 (233.5–320.0) | 237 (180.0–285.0) | 0.001 |

| Pedicle clamping, n (%) | 19 (21.5) | 7 (17.9) | 26 (20.4) | 0.812 |

Pathological findings

In the majority of cases one nodule was resected in group 1 (81.8%) and in group 2 (87.1%). We didn’t observed difference between the two group for the number of resected nodule (P=0.129). There was a trend for more high Edmondson-Steiner grade in group 2 (P=0.067). According with the TNM classification in group 1 we observed 27 (30.7%) cases of T1, 35 (39.8%) cases of T2, 24 (27.3%) cases of T3 and 2 (2.2%) cases of T4. In group 2, T1 was observed in 4 (10.2%) cases, T2 in 23 (59%) cases and T3 in 12 (30.8%) cases. Pathological findings are resumed in Table 3.

Table 3. Pathological findings.

| Histological examination | Group 1: ≥5 and <10 cm [88] | Group 2: ≥10 cm [39] | Total [127] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nodule (No.) | 0.129 | |||

| 1 | 72 (81.8) | 34 (87.1) | 106 (83.5) | |

| 2 | 10 (11.4) | 1 (2.6) | 11 (8.7) | |

| 3 | 3 (3.4) | 3 (7.7) | 6 (4.7) | |

| 4 | 0 | 1 (2.6) | 1 (0.8) | |

| 5 | 3 (3.4) | 0 | 3 (2.3) | |

| Tumor size (mm), median (IQR) | 60 (50.0–75.0) | 115.5 (100.0–150.0) | 80 (55.0–100.0) | 0.000 |

| Edmondson-Steiner grade, n (%) | 0.067 | |||

| 1 | 5 (5.7) | 2 (5.1) | 7 (5.5) | |

| 2 | 31 (35.2) | 6 (15.4) | 37 (29.1) | |

| 3 | 38 (43.2) | 19 (48.7) | 57 (44.9) | |

| 4 | 14 (15.9) | 12 (30.8) | 26 (20.5) | |

| TNM, n (%) | 0.101 | |||

| T1 | 27 (30.7) | 4 (10.2) | 31 (24.4) | |

| T2 | 35 (39.8) | 23 (59.0) | 58 (45.7) | |

| T3 | 24 (27.3) | 12 (30.8) | 36 (28.3) | |

| T4 | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.6) | |

| Steatosis (%) | 39 (44.3) | 19 (48.7) | 58 (45.6) | 0.241 |

| Microvascular invasion (%) | 46 (52.2) | 26 (66.6) | 72 (56.6) | 0.119 |

Post-operative results

In 29.5% of cases in group 1 the patient went in intensive care unit for a median time of 1 day. In group 2, 23% of patients needed an intensive care stay, in these cases median stay was 2 days (IQR 1–2). The median post-operative hospital stay was similar in the two groups (P=0.897), 9 days (IQR 6.5–14) in group 1, and 9 days (IQR 6–10.5) in group 2.

The post-operative morbidity was not different between the two groups (P=0.595). Two deaths were observed in the first group and none in the second group. The overall morbidity rate for Dindo-Calvien ≥ III was 4.6% and the overall mortality was 1.5%. All the post-operative results are resumed in Table 4.

Table 4. Post-operative morbidity and mortality.

| Morbidity/mortality | Group 1: ≥5 and <10 cm [88] | Group 2: ≥10 cm [39] | Total [127] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital stay, days, median (IQR) | 9 (6.5–14.0) | 9 (6.0–10.5) | 9 (6.0–13.0) | 0.897 |

| Patients went in intensive care unit, n (%) | 26 (29.5) | 9 (23.0) | 35 (27.5) | 0.230 |

| Intensive care unit stay (days), median (IQR) | 1 | 2 (1–2) | 1 | – |

| Clavien-Dindo, n (%) | 0.595 | |||

| 0 | 33 (37.6) | 12 (30.8) | 45 (35.5) | |

| I | 29 (33) | 15 (38.5) | 44 (34.7) | |

| II | 22 (25) | 8 (20.5) | 30 (23.7) | |

| III | 1 (1.1) | 3 (7.7) | 4 (3.1) | |

| IV | 1 (1.1) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (1.5) | |

| Mortality, n (%) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.5) | – |

Discussion

Our study suggests that liver resection for HCC nodule diameter ≥5 cm even in cases of diameter ≥10 cm is feasible and morbidity and mortality are acceptable. In our cohort 32.3% of giant HCC were seen without underlying liver disease which is comparable with the literature rate of 20% (14). Patients were mostly Child A with a good liver function (MELD <8). Serum alpha fetoprotein was historically used as HCC biomarker; however, not all HCCs secrete AFP. A higher level of alpha fetoprotein was observed in the group 2 without a significant difference. Regarding the type of surgery, for group 1 a major resection was necessary in 36.3% of cases. Despite more major hepatectomies were performed in the group 2 (66.6%) with our study we demonstrated that the morbidity was comparable (P=0.595). In addition, similarly to previous study the current study showed a lower mortality rates of 1.5% (2,15,16).

Equally to the higher number of major resection, in group 2 we observed a higher operative time, blood loss and number of transfusion. On the other hand, in the second group we used a laparoscopic approach more often than in the first group. We explain this little difference with the nodule location, in patients with HCC ≥10 cm and exophytic was more often observed. Although the international recommendation for laparoscopic liver resection is nodule <5 cm (17), in these cases the parenchymal transection need was minor justifying this approach. In our opinion, the laparoscopic approach for HCC may be proposed more often nowadays. This is a retrospective study; in our practice since 2004 we had performed more than 100 cases of laparoscopic resection for HCC (13). According to the high progress of minimally invasive surgery both minor and major liver resection are currently reported (18).

Nonetheless, this study was limited by the small sample size and the retrospective design. Furthermore, the preventive diagnosis in patients with underlying liver disease decreases the number of giant HCC. To further improve the management of giant HCC, more information about tumor biology and high risk population should be obtained.

In conclusion, this study shows that tumour size may not contraindicate a surgical resection of HCC even in patient with HCC ≥10 cm.

Acknowledgements

None.

Ethical Statement: The study is approved by the institutional ethical committee (2016/58) and obtained the informed consent from every patient.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Allemann P, Demartines N, Bouzourene H, et al. Long-term outcome after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma larger than 10 cm. World J Surg 2013;37:452-8. 10.1007/s00268-012-1840-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thng Y, Tan JK, Shridhar IG, et al. Outcomes of resection of giant hepatocellular carcinoma in a tertiary institution: does size matter? HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:988-93. 10.1111/hpb.12479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng KK, Vauthey JN, Pawlik TM, et al. Is hepatic resection for large or multinodular hepatocellular carcinoma justified? Results from a multi-institutional database. Ann Surg Oncol 2005;12:364-73. 10.1245/ASO.2005.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamashita Y, Taketomi A, Shirabe K, et al. Outcomes of hepatic resection for huge hepatocellular carcinoma (≥ 10 cm in diameter). J Surg Oncol 2011;104:292-8. 10.1002/jso.21931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi GH, Han DH, Kim DH, et al. Outcome after curative resection for a huge (>or=10 cm) hepatocellular carcinoma and prognostic significance of gross tumor classification. Am J Surg 2009;198:693-701. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruix J, Llovet JM. Prognostic prediction and treatment strategy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2002;35:519-24. 10.1053/jhep.2002.32089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Befeler AS, Di Bisceglie AM. Hepatocellular carcinoma: diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1609-19. 10.1053/gast.2002.33411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hassoun Z, Gores GJ. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;1:10-8. 10.1053/jcgh.2003.50003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou WP, Lai EC, Li AJ, et al. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of preoperative transarterial chemoembolization for resectable large hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg 2009;249:195-202. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181961c16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uchiyama K, Mori K, Tabuse K, et al. Assessment of liver function for successful hepatectomy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma with impaired hepatic function. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2008;15:596-602. 10.1007/s00534-007-1326-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205-13. 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levi Sandri GB, Colasanti M, Vennarecci G, et al. A 15-year experience of two hundred and twenty five consecutive right hepatectomies. Dig Liver Dis 2017;49:50-56. 10.1016/j.dld.2016.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ettorre GM, Levi Sandri GB, Santoro R, et al. Laparoscopic liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients: single center experience of 90 cases. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2015;4:320-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bralet MP, Régimbeau JM, Pineau P, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma occurring in nonfibrotic liver: epidemiologic and histopathologic analysis of 80 French cases. Hepatology 2000;32:200-4. 10.1053/jhep.2000.9033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liau KH, Ruo L, Shia J, et al. Outcome of partial hepatectomy for large (> 10 cm) hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2005;104:1948-55. 10.1002/cncr.21415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang CC, Jawade K, Yap AQ, et al. Resection of large hepatocellular carcinoma using the combination of liver hanging maneuver and anterior approach. World J Surg 2010;34:1874-8. 10.1007/s00268-010-0546-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wakabayashi G, Cherqui D, Geller DA, et al. Recommendations for laparoscopic liver resection: a report from the second international consensus conference held in Morioka. Ann Surg 2015;261:619-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levi Sandri GB, de Werra E, Mascianà G, et al. Liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma, are we going to dismiss the traditional approach? Ann Laparosc Endosc Surg 2017;2:34 10.21037/ales.2017.02.15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]