Abstract

Dieback and wilting symptoms caused by complex soilborne fungi are nowadays the most serious threatening disease affecting olive trees (Olea europaea) in Tunisia and presumably in many Mediterranean basin countries. Fusarium is one of the important phytopathogenic genera associated with dieback symptoms of olive trees. The objective of the present study was to confirm the pathogenicity of Fusarium spp. isolated from several olive-growing areas in Tunisia. According to the pathogenic test done on young olive trees (cv. Chemlali), 23 out of 104 isolates of Fusarium spp. were found to be pathogenic and the others were weakly or not pathogenic. The pathogenic Fusarium spp. isolates were characterized using molecular methods based on ITS PCR. Isolation results revealed the predominance of Fusarium solani (56.5%) and F. oxysporum species (21.7%) compared to F. chalmydosporum (8.7%), F. brachygibbosum (8.7%) and F. acuminatum (4.34%). Based on pathogenicity test, disease severity was highly variable among the 23 pathogenic isolates tested (P < 0.05) where F. solani was the most aggressive dieback agent. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work that shows that Fusarium spp. might be a major agent causing dieback disease of olive trees in Tunisia.

Keywords: Disease symptoms, Fusarium spp., Molecular identification, Olive tree (Olea europaea), Pathogenicity

Introduction

Olive tree (Olea europaea) is the most widely cultivated tree species in Tunisia. With a total cultivated area of about 1.7 million ha and more than 70 million olive trees (anonymous), Tunisia is ranked as the fourth producer of olive oil worldwide. However, many insect pests and plant pathogens constantly threaten olive cultivation. The dieback and wilting symptoms induced by complex soilborne fungi has caused considerable economic losses in olive orchards in Tunisia (Boulila and Mahjoub 1994; Triki et al. 2006, 2009, 2011; Gharbi et al. 2014, 2015). Among these fungi, Fusarium species may cause disease in olive trees. Diagnosis of dieback and decline of young olive trees revealed the presence of a broad range of fungi isolated from the affected plant tissues (Triki et al. 2009). Some species are known as common pathogens on olive trees, such as Verticillium dahliae (V. dahliae), but also an increased frequency of isolates belonging to the genus Fusarium was noted. These observations together with the increase of inquiries received by the Olive Tree Institute of Tunisia, led us to investigate the etiology of this disease, to perform pathogenicity tests of the different Fusarium species recovered from olive orchards and their identification based on morphological and molecular features. Disease incidence has increased over years and seems to be linked to changes in farming systems and the subsequencalculated using the following formulat decline in soil fertility. Regarding olive production, some fluctuations have been recorded which were probably linked to climatic conditions and to the presence of some fungi especially in soils previously cultivated with some susceptible vegetable crops (potato, tomato, pepper, eggplant, etc.). Consequently, with the establishment of new plantations, incidence of wilting, dieback and death of young trees has also increased (Triki et al. 2006, 2009, 2011). Disease impact was serious in nurseries and orchards during the first years after establishment, especially during spring and summer, causing important damage to new plantations. However, root rot of young olive trees was reported to be an emerging problem in nurseries and some important olive grove areas worldwide (Al-Ahmed and Hamidi 1984; Boulila et al. 1992; Sanchez-Hernandez et al. 1998; Lucero et al. 2006). Fusarium species have been recorded from several parts of the world and they are known to be pathogenic to many plants (Boughalleb et al. 2005; Mehl and Epstein 2007). In Tunisia, Ayed (2005) demonstrated the pathogenicity of Fusarium spp. on potato plants. Despite the importance of the olive-growing sector in Tunisia, this area is threatened by different species of soilborne pathogenic fungi, such as Fusarium. All these observations have raised the attention of researcher about the possible involvement of new pathogenic forms that may have evolved from other species infecting Solanaceous crops. Such question could be answered by investigating the prevalence and pathogenicity of each isolated fungal species. This will provide useful information towards a better understanding of the current phytosanitary status of olive trees, thus contributing to the design of better disease management programs in these infected areas. Therefore, the present study aims to (1) characterize morphologically and molecularly by polymerase chain reaction-internal transcribed spacer (ITS) Fusarium spp. isolates recovered from infected olives plants; (2) assess their pathogenicity and report the role of some abiotic factors in the increase of root rot disease.

Materials and methods

Fusarium isolates and culture conditions

One hundred and four isolates of Fusarium were obtained in 2011 from 65 roots and 114 stems belonging to diseased samples of olive trees showing typical wilt symptoms removed from many important olive-growing regions in Tunisia, including governorates of Monastir (Sahline, Boumerdes, Zarmedine), Kasserine, Sousse (Chott-Mariem), Sfax (Sidi-Bouakkazine), Mahdia, Sidi-Bouzid (Souk-jdid), Zaghouan (Nadhour) and Kairouan (Chbika) (Table 1). Samples were collected from more than 100 orchards and carried separately to the laboratory for isolation. Infected plant tissues were rinsed twice in water and then disinfected with 5% sodium hypochlorite for 5 min, washed with sterilized distilled water, prior to be cut aseptically into 0.5–2 cm pieces. Four to five pieces from each sample were placed onto each potato dextrose agar (PDA; Difco) plate. After 1 week of incubation at 25 °C, isolates were identified on the basis of their cultural characteristics and the morphology of their vegetative and reproductive structures produced on different culture media according to different keys of identifications (Booth 1966; Dhingra and Sinclair 1978; Nelson et al. 1983; Agrios 2004; Nasraoui 2006). Fungal isolates derived from single-spore cultures were obtained using the serial spore dilution method (Choi et al. 1999). Briefly, 1 ml of each serial dilution was mixed with melted nutrient agar and transferred to sterile plates. The plates were incubated at 25 °C in the dark and then visualized under the microscope to observe the germinating spores. These were later cut from the medium and transferred to new PDA plates for development of colonies. The pure cultures were maintained on PDA slants at 4 °C. The isolates were cultured in potato dextrose broth (PDB; Difco) on a rotary shaker (150 rpm) at 25 °C. The fungal mycelium was recovered by filtration, lyophilized, and stored at −20 °C until use.

Table 1.

List of Fusarium species isolated from olive plants collected from different sampling sites in Tunisia; (−) absent in the Solanaceous crops

| Isolates code | Molecular identification | Sampling site | Diseased organ | Solanaceous crops | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fso1 | F. solani | Sfax | Collar and Stem | Potato | KU528848 |

| Fso2 | F. solani | Sfax (Sidi Bou Akkazine) | Root | Pepper | KU528850 |

| Fso3 | F. solani | Monastir | Collar | Tomato | KU528851 |

| Fso4 | F. solani | Sfax (Mahres) | Root and Collar | Potato | KU528852 |

| Fso5 | F. solani | Kasserine | Collar | Potato | KU528854 |

| Fso6 | F. solani | Kasserine | Collar | Potato | KU528855 |

| Fso7 | F. solani | Monastir | Collar | Tomato | KU528857 |

| Fso8 | F. solani | Sousse | Collar and Stem | – | KU528858 |

| Fso9 | F. solani | Sfax (Mahres) | Collar | Piment | KU528859 |

| Fso10 | F. solani | Sfax (Mahres) | Collar | Potato | KU528860 |

| Fso11 | F. solani | Sousse (Sidi Bou Ali) | Collar | Potato | KU528861 |

| Fso12 | F. solani | Sfax (Sidi Bou Akkazine) | Collar | Potato | KU528862 |

| Fso13 | F. solani | Sousse | Root | Potato | KU528863 |

| Fox1 | F. oxysporum | Kairouan | Collar | – | KU528844 |

| Fox2 | F. oxysporum | Monastir | Collar | Pepper | KU528846 |

| Fox3 | F. oxysporum | Monastir | Collar | – | KU528847 |

| Fox4 | F. oxysporum | Sfax | Collar | – | KU528853 |

| Fox5 | F. oxysporum | Kasserine | Root and Collar | – | KU528856 |

| Fch1 | F. chlamydosporum | Sfax | Root and Collar | Potato | KU528845 |

| Fch2 | F. chlamydosporum | Sfax | Collar | – | KU528865 |

| Fbr1 | F. brachygibbosum | Sfax | Root | – | KU528849 |

| Fbr2 | F. brachygibbosum | Kairouan | Collar | – | KU528864 |

| Fac | F. acuminatum | Monastir | Collar and stem | Tomato | KU528866 |

Pathogenicity assay

Pathogenicity of the collected Fusarium spp. isolates was performed on 2-year-old olive plants (cv. Chemlali) (Rodriguez-Jurado et al. 1993; Triki et al. 2011; Gharbi et al. 2014). Fungal inoculum was prepared from 10-day-old cultures grown in PDA medium. Mycelium was recovered by aseptically scraping the surface of the medium and transferred into flasks containing sterilized distilled water. The conidial suspension was adjusted to 106 conidia/ml. Plants roots were washed, dried and dipped for 1 h in the prepared conidial suspension. After inoculation, olive plants were transplanted into new polyethylene pots containing a sterile substrate (peat:sand, 1:1 v/v). The experiment was conducted in a growth chamber in the Olive Tree Institute of Tunisia. Temperature during the trial was 23 ± 2 °C and plants were maintained under high relative humidity about 96% and a 16-h photoperiod. The experiment was conducted according to a randomized complete block with six replicates per isolate and six control plants dipped in sterilized distilled water.

Evaluation of pathogenicity

Disease severity was assessed visually and weekly, starting at 15 days post-inoculation. A scale from 0 to 4 was used based on the percentage of affected plant tissues (0 = healthy plant; 1 = ≤33% affected tissues; 2 = 34–66% affected tissues; 3 = 67–99%; 4 = dead plant). Estimation of the area under disease progress curve (AUDPC) was calculated as described previously (Campbell and Madden 1990). AUDPC values were used to classify isolates of the different Fusarium species. Analysis of variance was performed with a least significant difference with SPSS software (IBM Software) to determine the variability among isolates.

Measure of radial growth rate

The fungal radial growth rate (RGR) was determined according to Lamrani (2009). Pure culture of each Fusarium species was placed at the center of PDA and SNA (Synthetisher Nahrst off Agar) plates (Nirenberg 1976) and incubated separately at 11, 19, 27, 40 or 45 ± 2 °C. The diameter (D) of fungal colony formed at each temperature tested was measured daily using a digital caliper. Radial growth rate was calculated using the following formula (Lamrani2009) where:radial growth rate (mm/day) = RGR max (D max/2)/number of days.

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted only from 23 pathogenic Fusarium spp. isolates. The mycelium of each isolate was collected by scraping the surface of growing colonies on PDA medium (previously incubated for 1 week at 25 °C). After grinding 100 mg of fungal mycelia from each isolate in liquid nitrogen, the genomic DNA was extracted using the ZR Fungal/Bacterial DNA mini prep D6005 Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) as recommended by the manufacturer. The DNA purity and concentration were determined using a NanoDrop ND1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies Inc). Aliquots of samples were also analyzed on a 1% agarose gel to check DNA quality.

PCR amplification

All the isolates were characterized by amplification and sequencing of the ITS region. Amplification of ITS region was carried out using ITS1 and ITS4 primers (ITS1: 5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG/ITS4: 5′ TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC (White et al. 1990). PCR reactions were performed in 25 μl final volume containing 0.2 mM dNTPs mix, 1 μM of each primer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 U Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, France) and 50 ng of fungal DNA. Optimal PCR efficacy was obtained with an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min followed by 35 amplification cycles (denaturation, 95 °C for 35 s, annealing, 55 °C for 1 min, and extension, 72 °C for 2 min), and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were visualized on 1.5% agarose gel along a 1-kb DNA ladder (Promega, France).The fragments were excised and further purified for sequencing. Briefly, DNA extracted using the QIAquick Gel extraction Kit (Qiagen, USA) was then subjected to cycle sequencing using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, France) and processed by the ABI 3100 Genetic Analyzer. The obtained sequences were compared with the sequences available in GenBank by using the BLAST server from the NCBI website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST).

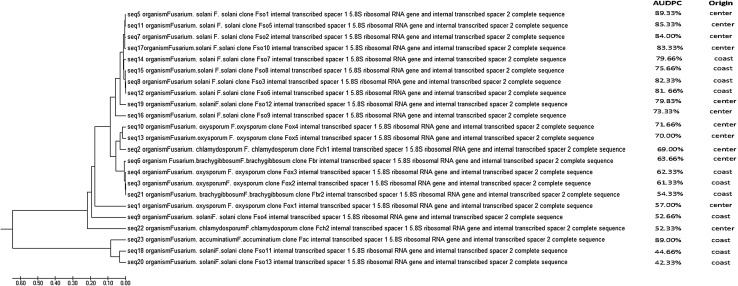

Sequencing alignment and phylogenetic analysis

The program Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis software, ver. 7.0 (MEGA7.0; http://www.megasoftware.net) was used to edit and align the ITS sequences. In order to assess the relationships between the genetic traits of the identified Fusarium species and their pathogenicity data, the ITS sequences were used to generate phylogenetic tree grouping the isolates in major clusters. The aligned sequences were deposited in the GenBank database. In this study, phylogenetic tree was generated using maximum parsimony (MP) in MEGA5.0. Bootstrap values for the maximum parsimony tree (MPT) were calculated for 1000 replicates. The edited ITS sequences were compared with other available Fusarium species sequences available in the GenBank.

Statistical analysis

All the optimization studies were conducted in triplicate and the data were analyzed using single factor analysis of variance (ANOVA). All the data were summarized as mean ± SD (standard deviation) of triplicates (n = 3). ANOVA was performed using Graph Pad Prism version 5.0b for Mac (Graph Pad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Significant differences between isolates were assessed at each time point by multiple comparisons of means using the Tukey test at P < 0.05.

Results

Isolation of Fusarium spp.

In this study, we were only interested in isolation of Fusarium spp. but other soilborne pathogens may also act as fungal complex in the dieback syndrome. Isolations performed from roots, stems and collar of wilted olive plants collected from several olive-growing areas during a survey of olive diseases conducted in 2011, allowed the recovery a high frequency of Fusarium spp. where 104 isolates were recovered compared to the other species.

Morphological identification and pathogenicity test of Fusarium spp.

One hundred and four fungal colonies formed on PDA medium were identified as Fusarium spp. based on the morphology of their colonies using the Fusarium synoptic keys for species identification of Leslie and Summerell (2006) and Nelson et al. (1983). These isolates were identified as F. solani, F. oxysporum, F. chlamydosporum, F. acuminatum and F. brachygibbosum and other Fusarium spp. Colonies of F. solani formed on PDA (Fisher et al. 1982) showed typical curved macroconidia widest in the middle of their length. The microconidia are oval, reniform, elongated oval to sometimes obovoid with a truncate base, and septated into 3–7. The size of conidia measures as: 44–78 × 3.3–5.6 μm. Chlamydospores formed were relatively abundant in mycelium, mostly globose, subglobose, intercalary and rough walled. The species are distinguished also by its white-to-cream mycelium and the production of green pigments on PDA medium. F. oxysporum colonies were characterized by an abundant white cottony mycelium and a dark-purple undersurface on PDA. Its microconidia are oval to ellipsoid or kidney shaped. Macroconidia were oval tapering and septated in 3 cells, their measurement indicated a size of 32–56 × 3.1–5.7 μm. Chlamydospores formed in chains. F. brachygibbosum showed microconidia are oval and the macroconidia are tapered and pointed, the size of conidia measures as follows: 25–68 × 3.6–6.0 μm. For F. acuminatum, microconidia are not a reliable taxonomic indicator, but this fungus was characterized by the long tapering curved macroconidia, with measured size of 35–58 × 3.0–5.0 μm, with the red pigmentation of the culture medium. Colonies of F. chlamydosporum were characterized by their white mycelial growth and abundant gamma-shaped microconidia and their curved-pointed macroconidia, measuring 37–58 × 3.0–5.0 μm. The other colonies were identified at the genus level only as Fusarium.

In the present study, the results of the pathogenicity test revealed that only 23 isolates among a total of 104 isolates of Fusarium spp. were found to be pathogenic and the others were weakly or not pathogenic. The symptoms induced by pathogenic Fusarium isolates developed within 20–25 days after inoculation. Leaves became brown and rolled gradually inwards. Necrosis and brown discoloration were observed on roots, crown and stem as well as a browning of the vascular tissues (Fig. 1). However, no symptoms were observed on the artificially inoculated trees by some isolates of Fusarium spp. which were classified as not pathogenic. The inoculated fungi were consistently isolated from the diseased plants, but not from negative control plants and non-virulent isolates. Thus, the Koch’s postulates were fulfilled.

Fig. 1.

Different symptoms of inoculated olive tree by Fusarium isolates. a Brown discoloration of the root, crown and stem; b browning of the vascular tissues c–d winding and drying of leaves (c: initial stage; d: final stage)

Characterization of pathogenic Fusarium species

Besides the morphological identification, the identity of the 23 pathogenic Fusarium isolates out of the 104 collected was confirmed by sequencing the amplified fragment of internal transcribed spacer region using the ITS universal primers ITS1 and ITS4 (Table 1). The analysis of ITS sequences of these 23 isolates by BLAST have shown that 13 of them (56.5%) were affiliated to the species F. solani with 99% homology. The accession numbers of each ITS sequence of these 13 isolates assigned to GenBank were KU528848, KU528850, KU528851, KU528852, KU528854, KU528855, KU528857, KU528858, KU528859, KU528860, KU528861, KU528862, and KU528863 (Table 1). Five isolates (21.7%) were identified as F. oxysporum and represented by the following accession numbers KU528844, KU528846, KU528847, KU528853, and KU528856. Two isolates (8.7%) were assigned to F. chlamydosporum species and were deposited in GenBank with the accession numbers KU528845 and KU528865. Two isolates (8.7%) were affiliated to F. brachygibbosum and their representative sequences were deposited in GenBank and assigned KU528849 and KU528864 as accession numbers. Finally, one isolate (4.34%) showed 99% homology with previously published sequences of F. acuminatum (GenBank accession No: KU528866). The result of these alignments was in agreement with those of morphological and species-specific PCR studies showed for the 23 sequences 99% homology with previously published sequences of the identified species.

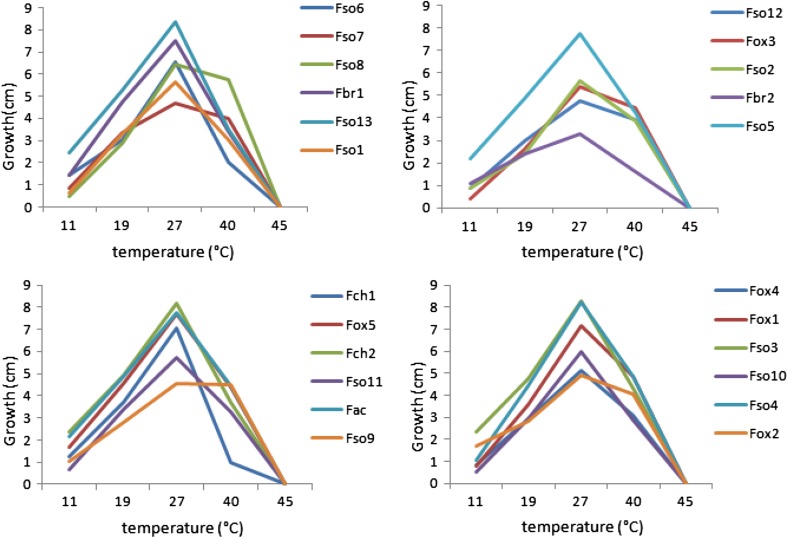

The study of the rate of radial growth of the 23 pathogenic Fusarium isolates was carried out on two different media SNA and PDA at 27 °C (Table 2). According to data, the radial growth of Fusarium spp. was higher on PDA than on SNA medium reaching about 8 mm/day for isolates: Fso3, Fso4, Fso13 and Fch2. Using analysis of variance (ANOVA), no significant difference was found between these four isolates (P > 0.05). Data of thermal effect showed a clear variation in the radial growth rate between Fusarium species (Fig. 2). For the majority of the isolates tested such as Fso13, Fso4, Fch2, Fac, Fbr1, and Fox1, radial growth reached its maximum at 27 °C. Although, Fusarium isolates maintained their level of growth at a temperature of 40 °C. These results confirmed that temperature factor influenced the radial growth of Fusarium spp. associated with olive trees. Thus, this parameter depended on the composition of the culture medium and the temperature of incubation.

Table 2.

Radial growth rate (RGR) on potato dextrose agar (PDA) and Synthetisher Nahrstoff agar (SNA)

| Isolates | Means AGR (mm/day) (SNA) ± SD | Means AGR (mm/day) (PDA) ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Fso4 | 5.507 ± 0.153a | 8.290 ± 0.338a |

| Fac | 5.586 ± 0.240a | 7.786 ± 0.228bc |

| Fox2 | 5.364 ± 0.260a | 7.797 ± 0.242bc |

| Fso3 | 5.306 ± 0.205ab | 8.083 ± 0.370ab |

| Fso7 | 5.065 ± 0.585ab | 4.550 ± 0.180h |

| Fso2 | 4.663 ± 0.197bc | 5.878 ± 0.196f |

| Fso1 | 4.720 ± 0.251c | 5.735 ± 0.236f |

| Fch1 | 4.692 ± 0.570c | 7.106 ± 0.133d |

| Fso10 | 4.258 ± 0.351c | 6.006 ± 0.117f |

| Fox5 | 4.283 ± 0.123d | 5.159 ± 0.213g |

| Fox4 | 3.445 ± 0.146e | 5.089 ± 0.181g |

| Fso13 | 3.607 ± 0.208a | 8.107 ± 0.198ab |

| Fso6 | 3.484 ± 0.015ef | 6.440 ± 0.120e |

| Fso11 | 3.310 ± 0.146ef | 5.769 ± 0.214f |

| Fox1 | 3.327 ± 0.208f | 7.309 ± 0.221d |

| Fbr1 | 2.631 ± 0.298g | 7.481 ± 0.154cd |

| Fso12 | 2.366 ± 0.283h | 4.926 ± 0.137gh |

| Fso9 | 2.244 ± 0.220h | 4.856 ± 0.108gh |

| Fso5 | 2.012 ± 0.116i | 5.152 ± 0.251g |

| Fbr2 | 1.652 ± 0.088ij | 3.278 ± 0.263i |

| Fch2 | 1.386 ± 0.226j | 8.191 ± 0.332ab |

| Fso8 | 1.174 ± 0.010k | 7.797 ± 0.242bc |

| Fox3 | 0.670 ± 0.020l | 7.468 ± 0.311cd |

Data represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3); (P < 0.05)

Fso6, F. solani 6; Fso7, F. solani 7; Fch1, F. chlamydosporum 1; Fox3, F. oxysporum 3; Fch2, F. chlamydosporum 2; Fso11, F. solani 11; Fac, F. acuminatum; Fso9, F. solani 9; Fso12, F. solani 12; Fox5, F. oxysporum 5; Fso2, F. solani 2; Fbr2, F. brachygibbosum 2; Fox2, F. oxysporum 2; Fso8, F. solani 8; Fbr1, F. brachygibbosum 1; Fso13, F. solani 13; Fso1, F. solani 1; Fox4, F. oxysporum 4; Fox1, F. oxysporum 1; Fso3, F. solani 3; Fso10, F. solani 10; Fso4, F. solani 4; Fso5, F. solani 5

Fig. 2.

Effect of incubation temperatures on mycelial growth (11, 19, 27, 40 and 45 °C) of the isolates of Fusarium spp.; a Fso6, Fso8, Fb1, Fso13, Fso1; b Fso12, Fox3, Fso2, Fbr2, Fso5; c Fch1, Fox5, Fch2, Fso11, Fac, Fso9; d Fox4, Fox1, Fso3, Fso10, Fso4, Fox2

The study of the pathogenicity degree of the 23 Fusarium isolates showed significant difference (P < 0.05) in their pathogenicity resulting in variable degrees of dieback of the infected plants. 2 months after inoculation, disease incidence reached 42% for the pathogenic isolates causing wilt symptoms compared to control plants. ANOVA results of disease severity were highly variable depending on tested isolates where AUDPC values ranged between 42.72 and 91.84% for pathogenic Fusarium isolates. This data indicates an important pathogenicity with varying degrees of aggressiveness (Table 3) . In fact, the isolates Fso1 and Fso2, recovered from Sfax region, and Fso5 from Kasserine site showed the highest virulence level (P < 0.05). These isolates were able to kill the plant within 2 months post-infection. Cross sections from plants inoculated by these isolates showed an intense browning of the vascular tissues. However, Fso11 and Fso13 isolates collected from Sousse region were the weakly aggressive isolates causing browning at the basal plant parts only (Fig. 1). The relationship among all isolates of Fusarium species, which showed that F. solani isolates (Fso1) from central and (Fso13) from coastal regions of Tunisia were placed in separated lineage with varied pathogenicity (Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Results of pathogenicity test of Fusarium spp. isolates, data represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3); (P < 0.05)

| Isolates | Means AUDPC ± SD | LSDa |

|---|---|---|

| Fso1 | 89.33 ± 2.082 | a |

| Fac | 89 ± 1 | a |

| Fso5 | 85.33 ± 2.082 | b |

| Fso2 | 84 ± 2 | bc |

| Fso3 | 82.33 ± 2.517 | cd |

| Fso6 | 81.667 ± 1.528 | cd |

| Fso7 | 79.667 ± 0.577 | d |

| Fso8 | 75.667 ± 1.528 | e |

| Fso9 | 73.333 ± 0.577 | ef |

| Fox4 | 71.667 ± 1.528 | fg |

| Fox5 | 70 ± 1 | gh |

| Fch1 | 69 ± 1 | h |

| Fbr1 | 63.66 ± 1.528 | i |

| Fox3 | 62.667 ± 1.528 | i |

| Fox2 | 61.333 ± 1.155 | ij |

| Fso12 | 60 ± 1 | j |

| Fox1 | 57 ± 1.732 | k |

| Fbr2 | 54.333 ± 1.528 | kl |

| Fso4 | 52.667 ± 3.055 | l |

| Fch2 | 52.33 ± 2.082 | l |

| Fso10 | 47 ± 2.646 | m |

| Fso11 | 44.667 ± 2.309 | m |

| Fso13 | 42.333 ± 0.5777 | n |

Fac, F. acuminatum; Fbr 1, F. brachygibbosum 1; Fch1, F. chlamydosporum 1; Fso1, F. solani 1; Fso2, F. solani 2; Fso3, F. solani 3; Fso4, F. solani 4; Fso5, F. solani 5; Fox1, F. oxysporum 1; Fox2, F. oxysporum 2; Fox3, F. oxysporum 3; Fso6, F. solani 6; Fso7, F. solani 7; Fox4, F. oxysporum 4; Fox5, F. oxysporum 5; Fso8, F. solani 8; Fso9, F. solani 9; Fso10, F. solani 10; Fso11, F. solani 11; Fso12, F. solani 12; Fso13, F. solani 13; Fbr2, F. brachygibbosum 2; Fch2, F. chlamydosporum 2

a P < 0.05

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic Tree of pathogenic Fusarium isolates

It should be indicated that 10–20% of sampling fields showing wilting disease were previously cropped with Solanaceous species. About 84.61% of F. solani isolates were recovered from samples collected from orchards already cropped with pepper, potato and tomato (Table 1).

Discussion

Fusarium is one of the important phytopathogenic genera associated with dieback symptoms of olive trees. Our survey clearly demonstrated that 104 of isolates recovered from 150 samples collected from olive trees showing dieback and wilting symptoms in various olive-growing regions in Tunisia were identified as Fusarium spp. Khosrow et al. (2015) have also reported similar results in Malaysia.

Few studies have investigated the pathogenicity of Fusarium spp. of the olive. Many Fusarium isolates were considered as weak or opportunistic as they are able to attack only the plants already weakened by other abiotic stress such as drought, wind, and insect pests (Palmer and Kommedahl 1960). In the present study, the pathogenicity test performed on young olive trees (cv. Chemlali), demonstrate that only 23 out of 104 Fusarium spp. isolates collected were pathogenic. The species of F. brachygibbosum and F. chlamydosporum have not yet been published in Tunisia as pathogens of olive trees. Cross sections from plants inoculated by these isolates showed an intense browning of the vascular tissues. The other isolates were weakly or not pathogenic as they caused browning at the basal plant parts only. According to Van Alfen (1989), browning of the vascular tissues is a result of physical blockage due to the rotted roots and root rotting which is also a disease symptom.

Our observations in different Tunisian olive groves have shown that disease severity can be increased under certain environmental conditions especially in spring with average temperatures varying between 25 and 30 °C, in flooding and in irregular irrigation furrow. The majority of Fusarium isolates grown on PDA medium reached their maximum radial growth rates at 27 °C. The activity of soilborne fungi is generally controlled by temperature among other biotic and abiotic factors (Theron and Holz 1990; Brock et al. 1994; Dix and Webster 1995).

Our data clearly demonstrated that the radial growth of Fusarium spp. was higher on PDA than on SNA medium. Under natural conditions, fungus growth is very slow. This is due to the low intake of substrates and to the heterogeneity of nutrient distribution in microbial habitats. Growth can also be slowed by other factors such disturbances as antagonistic interactions with other species which compete for the same substrate, animal invasions, the stress caused by nutrient depletion and changes in physical conditions (temperature, pH, etc.) (Brock et al. 1994).

Severity and incidence of diseases caused by each Fusarium species vary according to the geographical location, climatic factors and cultural practices (Daami-Remadi 2006). Different fungal pathogens were isolated with varying frequencies, but the most frequently isolated fungi from rotten roots and crowns were Fusarium spp. These fungi were consistently isolated from contaminated cuttings of olive trees removed from different areas, suggesting their potential involvement in the spread and incidence of root rot disease. In addition, in Tunisia, many farmers produce the olive through vegetative cuttings suggesting that these pathogens have been broadcasted from a producing area to another as reported from other countries (Rodriguez et al. 2008). Our results confirm this observation. In fact, 84.61% of F. solani isolates were recovered from samples collected from orchards already precultivated by pepper, potato and tomato crops. Intercropping of Solanaceous crops within olive groves may be a source of transmission of fungal diseases as these crops are very susceptible to soilborne pathogens including Fusarium spp. and V. dahliae (Serrhini and Zeroual 1995; Gharbi et al. 2015). This is because many of these crops (cotton, potato, tomato, alfalfa, or even olive itself) increase the pathogen population in soil in a very efficient way (Tjamos and Tsougriani 1990; Bejarano-Alcázar et al. 1996). The severity of Fusarium diseases is conditioned by various factors, including the climate conditions and the physiology of the host plant (Tivoli et al. 1986).

In conclusion, the results of present study stated that Fusarium spp. might be a major agent causing wilt and dieback of olive trees in Tunisia. Although further studies on cross pathogenicity by predicting the virulence of isolates collected from other crops towards olive will provide crucial information to be used for rotations of the annual crops that are grown within or adjacent to olive orchards. This information will help the farmers to decide which crops may not be suitable for their fields.

Acknowledgements

This work is part of a doctoral thesis prepared by Rahma Trabelsi. We would like to thank the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, Tunisia, and the Institution of Agricultural Research and Higher Education (IRESA) for their financial support. The authors are grateful to Hanen FARJALLAH, translator and English professor for having proofread the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Agrios GN. Plant pathology. 4. Amsterdam: Elseiver; 2004. p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ahmed M, Hamidi M. Decline of olive trees in southern Syria. Arab J Plant Protection. 1984;2:70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ayed F (2005) La flétrissure fusarienne de la pomme de terre: comportement variétal approches de lute chimique et biologique. Mastère en Protection des Plantes et Environnement de l’Institut Supérieur Agronomique de Chott-Mariem, Tunisie, p 85

- Bejarano-Alcázar J, Blanco-López MA, Melero-Vara JM, Jiménez-Díaz RM. Etiology, importance, and distribution of Verticillium wilt of cotton in southern Spain. Plant Dis. 1996;80:1233–1238. doi: 10.1094/PD-80-1233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Booth C, The Common wealth Mycological Institite The genus Cylindrocarpon. Mycol Papers. 1966;104:34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Boughalleb N, Armengol J, El Mahjoub M. Detection of races 1 and 2 of Fusarium solani f. sp. cucurbitae and their distribution in watermelon fields in Tunisia. J Phytopathol. 2005;153:162–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0434.2005.00947.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boulila M, Mahjoub M. Inventory of olive diseases in Tunisia. EPPO Bull. 1994;24:817–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2338.1994.tb01103.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boulila M, Mahjoub M, Chaieb M. Synthèse de quatre années de recherches sur le dépérissement de l’olivier en Tunisie. Olivae. 1992;23:112. [Google Scholar]

- Brock PM, Inwood JRB, Deverall BJ. Systemic induced resistance to Alternaria macrospora in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) Australas Plant Pathol. 1994;23:81–85. doi: 10.1071/APP9940081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CL, Madden LV. Introduction to plant disease epidemiology. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1990. p. 532. [Google Scholar]

- Choi YW, Hyde KD, Ho WH. Single spore isolation of fungi. Fungal Divers. 1999;3:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Daami-Remadi M (2006) Etude des fusarioses de la pomme de terre. Thèse, Institut Supérieur 424 Agronomique de Chott- Mariem, Tunisie, p 238

- Dhingra OD, Sinclair JB. Biology and Pathology of Macrophomina phaseolina. Minas Gerais: Universidade Federal de Vicosa; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Dix NJ, Webster J. Fungal Ecology. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1995. p. 549. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher NL, Burgess LW, Toussoun TA, Nelson PE. Carnation leaves as a substrate and for preserving Fusarium species. Phytopathology. 1982;72:151–153. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-72-151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gharbi Y, Triki MA, Jolodar A, Trabelsi R, Gdoura R, Daayf F. Genetic diversity of Verticillium dahliae from olive trees in Tunisia based on RAMS and IGS-RFLP analyses. Can J Plant Pathol. 2014;36:491–500. doi: 10.1080/07060661.2014.964776. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gharbi Y, Alkher H, Triki MA, Barkallah M, Bouazizi E, Trabelsi R, Fendri I, Gdoura R, Daayf F. Comparative expression of genes controlling cell wall-degrading enzymes in Verticillium dahliae isolates from olive, potato and sunflower. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2015;91:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2015.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khosrow C, Baharuddin S, Latiffah Z. Morphological and phylogenetic analysis of Fusarium solani species complex in Malaysia. Microb Ecol. 2015;69:457–471. doi: 10.1007/s00248-014-0494-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamrani K (2009) Etude de la biodiversité des moisissures nuisibles et utiles isolées à partir des Maâsra du Maroc. Thèse en Microbiologie, Université Mohamed V-Agdal Faculté des Sciences Rabat. N°d’ordre: 2461

- Leslie JF, Summerell BA. The Fusarium laboratory manual. 1. New York: Blackwell Publishing Professional; 2006. pp. 8–240. [Google Scholar]

- Lucero G, Vettraino AM, Pizzuolo P, Di Stefano C, Vannini A. First report of Phytophthora palmivora on olive trees in Argentina. New Dis Rep. 2006;14:32. [Google Scholar]

- Mehl HL, Epstein L. Identification of Fusarium solani f. sp. cucurbitae race 1 and race 2 with PCR and production of disease-free pumpkin seeds. Plant Dis. 2007;91:1288–1292. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-91-10-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasraoui B (2006) Les champignons parasites des plantes cultivées. Collection M/Science de l’ingénieur. Centre de publication universitaire Tunisie, p 456

- Nelson PE, Toussoun TA, Marasas WFO. Fusarium species: An Illustrated manual for identification. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press; 1983. p. 193. [Google Scholar]

- Nirenberg HL (1976) Untersuchungen uber die morphologische und biologische differenzierung in der Fusarium-section Liseola. Mitteilungen aus der biologischen (Bundesanstalt fur land-und forstwirtschaft, Berlin-Dahlem) 169:1-117

- Palmer LT, Kommedahl T. Root-infecting Fusarium species in relation to rootworm infestations in corn. Phytopathology. 1960;59:1613–1617. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez E, Garcia-Garrido JM, Garcia PA, Campos M. Agricultural factors affecting Verticillium wilt in olive orchards in Spain. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2008;122:287–295. doi: 10.1007/s10658-008-9287-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Jurado D, Blanco-Lopez MA, Rapoport HF, Jimenez-Diaz RM. Present status of Verticillium wilt of olive in Andalusia (southern of Spain) EPPO Bull. 1993;23:513–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2338.1993.tb01362.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Hernandez ME, Ruiz Davila A, Perez Delgaba A, Balanco-Lopez MA, Trapero-Casas A. Occurrence and etiology of death of young olive trees in southern Spain. Eur J Plant Pathol. 1998;104:347–357. doi: 10.1023/A:1008624929989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serrhini MN, Zeroual A. Verticillium wilt in Morocco. Olivae. 1995;58:58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Synonymous (2017) Observation National de l’Agriculture, http://www.onagri.nat.tn/indicateurs. Accessed 31 Mar 2017

- Theron DJ, Holz G. Effect of temperature on dry rot development of potato tubers inoculated with different Fusarium spp. Potato Res. 1990;33:109–117. doi: 10.1007/BF02358135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tivoli B, Deltour A, Molet D, Bedin P, Jouan B. Mise en évidence de souches de Fusarium roseum var. sambucinum résistantes au thiabendazole, isolées à partir de tubercules de pomme de terre. Agronomie. 1986;6:219–224. doi: 10.1051/agro:19860212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tjamos EC, Tsougriani H (1990) Formation of Verticillium dahliae microsclerotia in partially disintegrated leaves of Verticillium affected olive trees. In: 5th Int Verticillium Symposium, Book of Abstracts, Leningrad, Soviet Union, p 20

- Triki MA, Hassaïri A, Mahjoub M. Premières observations de Verticillium dahliae sur l’olivier en Tunisie. EPPO Bull. 2006;36:69–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2338.2006.00941.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Triki MA, Rhouma A, Khabou W, Boulila M, Ioos R (2009) Recrudescence du dépérissement de l’olivier causé par les champignons telluriques en Tunisie. In: Proceeding of Olivebioteq

- Triki MA, Krid S, Hsairi H, Hammemi I, Ioos R, Gdoura R, Rhouma A. Occurrence of Verticillium dahliae defoliating pathotypes on olive trees in Tunisia. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2011;50:267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Van Alfen NK. Reassessment of Plant Wilt Toxins. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1989;27:533–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.27.090189.002533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns TD, Lee S, Taylor JT. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ, editors. PCR protocols. San Diego: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]