The refugee crisis was a controversial topic during the 2016 US presidential election and continues to generate political discussion. As health care providers, our responsibility is to set politics aside and provide high-quality medical care to these individuals. To do this, we must first understand the process by which they get to the United States and the obstacles they face. Current obstacles include language barriers, unsure access to medical insurance, navigation of a complex and confusing health care system, and misalignment of medical treatments with cultural or religious beliefs.

RESETTLEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES

Refugees are a specific category of immigrants that flee their home country because of persecution.1 The vast majority of refugees will settle into the country to which they flee, with a smaller portion moving on to a third country. The United States has a long history of accepting refugees into its borders by a process called resettlement.2 In 2016, the United States resettled 84 995 refugees from all parts of the world.3

The resettlement process is complex and lengthy. Refugees are referred to the United States by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and are handled by the US Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration. This bureau operates nine Resettlement Support Centers, whose role is to process and prepare a refugee for entry into the United States.1 This process includes biographical collection, medical screening, an in-person interview, and enhanced security screening. The Department of State, the Department of Homeland Security, the National Counterterrorism Center, and the Department of Defense all participate in the enhanced security screening. After these requirements are met, the Resettlement Support Center requests sponsorship assistance in the United States by a resettlement agency. These resettlement agencies are usually state specific and rely on voluntary agencies to aid in the transition of refugees. Finally, the refugee is given a brief cultural orientation and flown to the United States. On average, this process takes 18 to 24 months.1

THE TALE OF A SOMALI REFUGEE

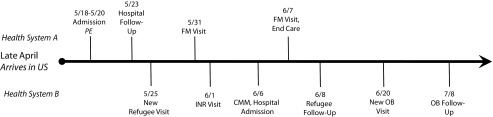

In spring 2016, we encountered a young female Somali refugee who simultaneously accessed two health care systems (Figure 1) and encountered several barriers to optimal health care (Appendix A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, has a full report of the case). Our case highlights this complexity, including her use of two health care systems, the delay in obtaining health insurance, and the disconnect that medical treatments can have with a patient’s religious beliefs.

FIGURE 1—

2016 Timeline of Female Somali Refugee’s Use of the Health Care System, St. Paul, Minnesota

Note. CMM = comprehensive medication management; FM = family medicine; INR = international normalized ratio; OB = obstetric; PE = pulmonary embolism.

Ideally, her voluntary agency should have been available to help her navigate the medical system for both her acute needs and her required health screening. However, voluntary agencies are given very limited government financial assistance to aid the refugee in obtaining food, housing (including furnishings), clothing, English language education, employment counseling, education, and medical care.4 The list of other requirements for voluntary agencies is quite lengthy. These organizations rely on volunteers and often face numerous obstacles to coordinate care effectively, including inadequate funding, lack of familiarity with the health care system, language barriers, and patients asking family or friends to help navigate the system.

MEDICAID BENEFITS

Another barrier in the current system is the delay in obtaining Medicaid benefits. Refugees are covered under federally funded Medicaid for at least the first three months of their arrival, but they often receive longer assistance from state programs. Unfortunately, there is almost always a delay between arrival and activation of their insurance, resulting in a medical coverage gap during a critical time.

Our family medicine clinic is fortunate to have a partnership with an independent outpatient pharmacy that provides prescription needs to refugees “on account” in anticipation of the patient receiving active coverage. This can be a risky practice because even though Medicaid coverage is guaranteed, the patient could leave the state before coverage activation, resulting in loss of revenue. Many pharmacies are unwilling to provide medication without a guaranteed payment at the time of service.

CULTURE AND RELIGION

A further difficulty refugees may encounter is health care practices that do not align with their cultural or religious beliefs. Our patient did not want to take a medication because of its pork content. The Qur’an (5:3; 6:145) forbids Muslims to consume swine because it is considered unclean. This applies to all ingested products, including food and potentially medications. In a survey of religious leaders, leaders for both Sunni and Shiite Muslims did not approve of medical porcine products including drugs, dressings, or implants; however, they did say these products would be allowed if the treatment would be considered life-prolonging with no alternative available.5 Furthermore, a letter written in 2001 by the World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean summarized the decision of a meeting of Islamic legal scholars that allowed the use of pork products in medication, stating that the conversion into a medical product made the substance pure and acceptable to ingest.6 Still, in our experience, when presented with this information, many Muslim patients continue to refuse pork-based therapy.

When presenting treatment options, it is important for health care providers to offer informed consent to patients, which includes religious and cultural considerations. Failure to do so could result in a violation of the patient’s beliefs and a breakdown in the provider-patient relationship, which may potentially lead to nonadherence. Sattar et al.7 outlined four cases in which patients discontinued therapy because of inert porcine or bovine content of medications. In the case presented in the Appendix, the patient was originally prescribed a pork-containing product, enoxaparin, at a different health care system. We do not believe that the initial health system intentionally misinformed the patient but rather was unaware of the porcine content of enoxaparin. This medication was continued within our health care system until a clinical pharmacist, knowledgeable about the content of the product, identified the potential religious objection.

MAKE REFUGEE HEALTH CARE GREAT

The United States is a land of opportunity for refugees fleeing persecution and war. Here they have a chance to restart their lives in a safer environment with greater access to educational and economic well-being. We all have work to do to improve the quality of care for our new arrivals. Team-based care in a primary care clinic can serve as the foundation to provide culturally sensitive quality care to assist refugees. Improvements need to be made in cultural awareness and sensitivity for providers and health administrators. We need to identify common misalignments of health care with cultural beliefs. Furthermore, voluntary agencies need enhanced support to aid refugees in navigating the health care system. Additional expenditures for care management or cultural brokers would likely result in overall cost savings. Finally, it is also necessary to repair the flaws in the current health insurance coverage of new refugees to ensure more timely access to health care.

As the US health care system continues to evolve, we should prioritize the development of systems to assist disadvantaged groups, including refugees, to obtain access to timely and appropriate health care.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of State. U.S. Refugee Admissions Program. Available at: https://www.state.gov/j/prm/ra/admissions/index.htm. Accessed February 14, 2017.

- 2.McNeely CA, Morland L. The health of the newest Americans: how US public health systems can support Syrian refugees. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):13–15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. US Department of State, Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, Office of Admissions - Refugee Processing Center. Summary of Refugee Admissions as of 31-December-2016. Available at: http://www.wrapsnet.org/s/Refugee-Admissions-Report-2016_12_31.xls. Accessed January 17, 2017.

- 4.US Department of State. FY 2011 Reception and Placement Basic Terms of the Cooperative Agreement Between the Government of the United States of America and the (Name of Organization). Available at: https://www.state.gov/j/prm/releases/sample/181172.htm. Accessed February 16, 2017.

- 5.Eriksson A, Burcharth J, Rosenberg J. Animal derived products may conflict with religious patients’ beliefs. BMC Med Ethics. 2013;14:48. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-14-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gezairy HA. Dear Dr [letter]. July 17, 2001. World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Available at: http://www.immunize.org/concerns/porcine.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2017.

- 7.Sattar SP, Ahmed MS, Majeed F, Petty F. Inert medication ingredients causing nonadherence due to religious beliefs. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:621–624. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]