Abstract

Photosynthetic microbes are of emerging interest as production organisms in biotechnology because they can grow autotrophically using sunlight, an abundant energy source, and CO2, a greenhouse gas. Important traits for such microbes are fast growth and amenability to genetic manipulation. Here we describe Synechococcus elongatus UTEX 2973, a unicellular cyanobacterium capable of rapid autotrophic growth, comparable to heterotrophic industrial hosts such as yeast. Synechococcus UTEX 2973 can be readily transformed for facile generation of desired knockout and knock-in mutations. Genome sequencing coupled with global proteomics studies revealed that Synechococcus UTEX 2973 is a close relative of the widely studied cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942, an organism that grows more than two times slower. A small number of nucleotide changes are the only significant differences between the genomes of these two cyanobacterial strains. Thus, our study has unraveled genetic determinants necessary for rapid growth of cyanobacterial strains of significant industrial potential.

Among the photosynthetic organisms, cyanobacteria offer attractive systems for biotechnological applications due to their increased growth rate compared to plants and their relative ease of genetic manipulation compared to eukaryotic algae1,2,3. Unlike heterotrophic microbes such as the bacterium Escherichia coli and the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae that are of common industrial use, cyanobacteria can grow photoautotrophically by harvesting light energy. The ability to use solar energy to fix carbon dioxide and generate oxygen has made cyanobacteria one of the primary producers on our planet4. There is considerable current interest in using cyanobacteria to mitigate the effects of increasing amounts of atmospheric carbon dioxide5. Some strains of cyanobacteria can accumulate large amounts of lipids and are excellent candidates for biofuel production3. Also, cyanobacterial biomass is becoming a compelling alternative to biomass from food crops in the bioenergy arena6. Cyanobacteria can grow in fresh or seawater, or even wastewater, thus avoiding the potential conflict between food and fuel production. Furthermore, cyanobacteria have a broad spectrum of secondary metabolites, including amino acids, fatty acids, macrolides, lipopeptides, amides7, some of which are potential pharmaceutical agents. Recently, three cyanobacterial model strains, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, Synechococcus elongatus sp. PCC 7942 and Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002, have been used in synthetic biology studies for biosynthesis of multiple products including free fatty acids8, isoprene9, 2,3-butanediol10, 1-butanol11, squalene12, n-alkanes13 and hydrogen14.

Despite these advantages of using cyanobacteria in biotechnological settings, some limitations have kept these organisms from becoming the preferred microbial platforms in such applications. So far, the genetic and metabolic networks in cyanobacteria are not as well understood as in microbes such as E. coli and S. cerevisiae, and the biological “parts list” in cyanobacterial cells are not standardized and well-characterized2. In contrast, the E. coli system has been extensively studied, so that metabolic networks are known in detail and a wide array of synthetic biology tools are available. However, phototrophic cyanobacterial cells are functionally quite distinct from heterotrophic E. coli cells15, resulting in the limited application of current biotechnological tools, which cannot be directly applied to cyanobacteria without modification. Efforts focusing on understanding cyanobacterial systems are underway; however, one drawback compared to E. coli or yeast is that the growth rates of commonly used cyanobacterial model strains are significantly slower, requiring extended timeframes (weeks to months) to accomplish synthetic biology experiments that can be performed in E. coli or yeast in days. Also, many cyanobacteria contain multiple copies of chromosomes (~12 copies/cell in Synechocystis PCC 680316 and ~ 5–7 copies/cell in Synechococcus PCC 794217). Therefore, eliminating a gene from all copies of the chromosome may take several rounds of segregation.

A cyanobacterial strain that can grow rapidly and is amenable to facile, targeted genetic manipulation would expedite the process of standardizing and characterizing biological parts of cyanobacterial systems. We therefore sought to identify and characterize such a strain in order to build a superior cyanobacterial chassis for synthetic biology and metabolic engineering applications. In this communication, we describe the identification of a unicellular cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus UTEX 2973 (hereafter Synechococcus UTEX 2973), a relative of Synechococcus elongatus PCC 6301 and PCC 7942, that displays a substantially faster growth rate than any other commonly used cyanobacterium. We determined the genome sequence of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 and analyzed its global proteome. Furthermore, we determined that targeted genetic modifications can be rapidly engineered in this organism. Our data demonstrate the excellent potential of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 as a cyanobacterial chassis for broad biotechnological applications.

Results

Rapid growth of Synechococcus elongatus UTEX 2973

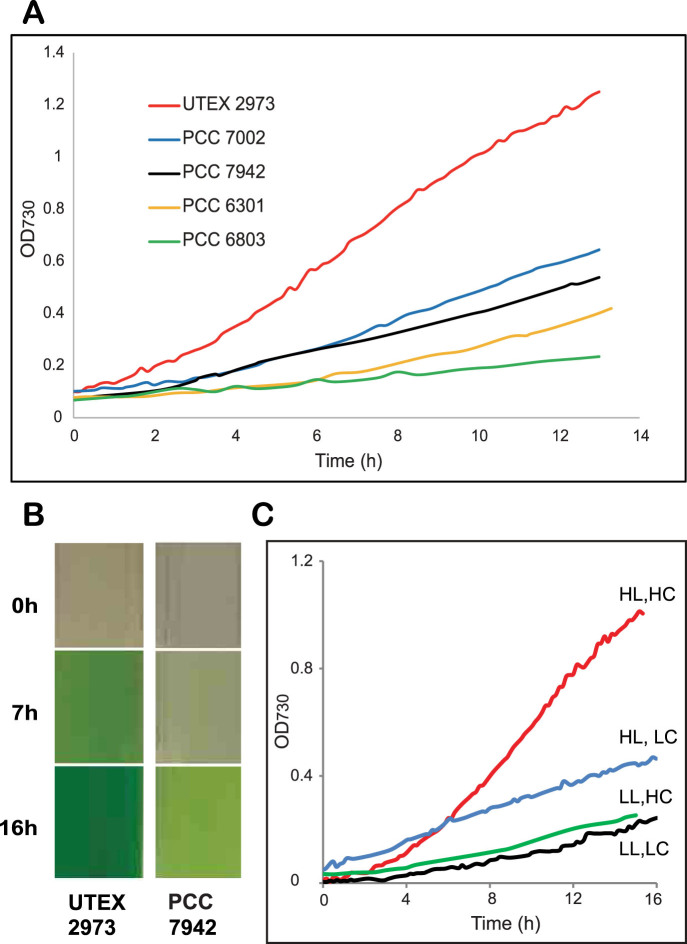

In 1955, Kratz and Myers18 described a fast growing cyanobacterial strain, Anacystis nidulans. This strain was subsequently deposited in the University of Texas algae culture collection as Synechococcus leopoliensis UTEX 625. However, during recent years, this strain lost its rapid growth property (see Methods section) and was also unable to grow at a temperature as high as 38°C, unlike the original strain described by Kratz and Myers18. We selected a single cyanobacterial colony from a mixed culture of Synechococcus UTEX 625 that was able to grow at 38°C, and deposited the resulting strain to the UTEX algae culture collection as Synechococcus elongatus UTEX 2973. Growth of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 was assessed under different conditions and the shortest doubling time was 1.9 hrs in BG11 medium19 at 41°C under continuous 500 μmoles photons·m−2·s−1 white light with 3% CO2. This is a remarkably high growth rate under autotrophic condition, the highest rate reported to date for a cyanobacterial strain, and comparable to heterotrophic growth rates of the yeast S. cerevisiae. The doubling time of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 increased to 2.3 hrs at 38°C (Table 1). However, this rate is still nearly twice as fast as that for Synechococcus PCC 7942 (~4.1 hrs) under similar conditions (Fig. 1A). Growth rates of three other commonly used cyanobacterial strains, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 and Synechococcus PCC 6301, were also significantly slower than that of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 (Fig. 1A and Table 1). A direct result of such a rapid growth property is that a dilute culture of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 accumulated substantial amounts of biomass within a 16 h time period. In contrast, a Synechococcus PCC 7942 culture was still dilute when both cultures were grown under their respective optimal conditions (Fig. 1B). Similar results were obtained for biomass accumulation of these two strains. The dry weight of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 increased from 0.13 ± 0.01 mg/ml at the beginning of the experiments to 0.87 ± 0.03 mg/ml after 16 hours, while the dry weight of Synechococcus PCC 7942 changed from 0.12 ± 0.02 mg/ml to 0.33 ± 0.03 mg/ml during the same period of time. As shown in Fig. 1C, a high level of illumination as well as CO2 are important factors to support rapid growth of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 (Fig. 1C).

Table 1. Doubling times of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 and other model cyanobacterial strains under different conditions. The colors of highlighted values correspond to the colors of the growth curves shown in Fig 1.

| Temp (°C) | 41 | 38 | 30 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 (v/v) | 3% | 3% | Air (0.04%) | 3% | |||||

| Light intensity* | 500 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 500 | 100 | 500 | 300 | |

| UTEX 2973 | Doubling time (hrs) | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 5.0 ± 0.4 | - | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 6.3 ± 1.7 | 5.4 ± 0.9 | - |

| PCC 7942 | - | 6.1 ± 0.3 | - | 4.9 ± 0.7 | 8.5 ± 0.3 | 8.7 ± 0.7 | - | - | |

| PCC 7002 | - | - | 9.3 ± 0.3 | - | 4.1 ± 0.4 | - | - | - | |

| PCC 6301 | - | - | - | - | 5.4 ± 0.3 | - | - | - | |

| PCC 6803 | NG | NG | NG | NG | NG | NG | NG | 6.6 | |

Means +/− standard deviation of 5 replicates, except for Synechocystis PCC 6803, for which the mean doubling time of two replicates is shown.

*, in µmole photons·m−2·s−1.

-, not determined.

NG, no growth.

Figure 1. Comparison of growth rates of different cyanobacterial strains.

(A) Growth curves of strains under individual optimal conditions. Synechococcus UTEX 2973: 41°C, 500 µmole photons·m−2·s−1; Synechococcus PCC 7002: 38°C, 500 µmole photons·m−2·s−1; Synechococcus PCC 7942: 38°C, 300 µmole photons·m−2·s−1; Synechococcus PCC 6301: 38°C, 500 µmole photons·m−2·s−1; Synechocystis PCC 6803: 30°C, 300 µmole photons·m−2·s−1. All cultures were grown with 3% (v/v) CO2 bubbling. (B) Visual comparison of culture densities of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 and Synechococcus PCC 7942 during a 16 h growth period. (C) Growth curves of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 at 38°C under different conditions. HL (high light): 500 µmole photons·m−2·s−1; LL (low light): 100 µmole photons·m−2·s−1; HC (high CO2, 3%); LC (low CO2, 0.04%). Measurements were made every 10 min. Five replicate growth curves were generated for each strain under indicated conditions, except for Synechocystis PCC 6803, which had two replicates. The representative curves are shown in the figure.

Genomic and Proteomic analysis of Synechococcus UTEX 2973

The original Anacystis nidulans strain18 was also deposited to the Pasteur Culture Collection as Synechococcus sp. PCC 6301. Whole genome sequencing of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 indicated that this strain is similar to Synechococcus PCC 6301 in terms of the general features of their genomes (Table 2). Unexpectedly, the genome sequence of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 exhibited remarkable similarity to that of the widely studied model cyanobacterium Synechococcus PCC 7942, an organism that has apparently been isolated from a distant geographical location. In fact, there were a total of 55 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertion-deletions (indels) between the two genomes. Among these 55 differences, 39 were in chromosomes and 16 were in plasmids. Among the 39 differences in chromosomes, 28 were in protein coding regions, with 26 of these shown in Table 3, plus a large deletion shown in Table S1 and a 188.6 kb inversion shown in Fig 2 and Table S2. Among the 16 differences in plasmids, 7 were in protein coding regions (Table 4). We examined these differences and identified the affected genes, some of which are important components of known biochemical processes (Tables 3 and 4). For instance, the gene encoding the ATP synthase F1 subunit α in Synechococcus UTEX 2973 contains an SNP compared to the corresponding gene in Synechococcus PCC 7942. This SNP causes an amino acid substitution (Tyr in UTEX 2973 changed to Cys in PCC 7942) at the 252th position in this protein (Table 3). Importantly, detected peptides in our global proteomics study (see below) confirmed the Y to C replacement at that position in the two strains.

Table 2. General features of the genome of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 compared to genomes of other related cyanobacteria.

| Synechococcus UTEX 2973* | Synechococcus PCC 7942* | Synechococcus PCC 6301* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 2,690,418 | 2,695,903 | 2,696,255 |

| GC content | 55.4% | 55.4% | 55.5% |

| Protein coding genes | 2,645 | 2,661 | 2,525 |

| rRNA operons | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| tRNA genes | 44 | 44 | 45 |

*, data from NCBI Genbank and JGI database.

Table 3. SNPs and indels in coding regions of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 chromosome (accession number in NCBI: CP_006471) compared to the reference genome of Synechococcus PCC 7942 (CP_000100). Corresponding differences in amino acids in the encoded proteins in Synechococcus UTEX 2973 are shown. RFC, Reading Frame Change.

| Nucleotide position in UTEX 2973 genome | Locus tag (M744) | Protein | Amino acid change | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 126938 | 00705 | Hypothetical protein | STOP 146 L | 159 aa in PCC 7942 |

| 236706 | 01335 | ATP synthase F0F1 subunit alpha | Y 252 C | Confirmed by proteomics data |

| 475352 | 02605 | Chemotaxis protein CheY | R 121 Q | |

| 475390 | 02605 | Chemotaxis protein CheY | K 134 E | |

| 518500 | 02855 | Pili assembly chaperone | A 52 D | |

| 606448 | 03320 | 23S ribosomal RNA | ||

| 608335 | 03320 | 23S ribosomal RNA | ||

| 610804 | 03335 | Manganese ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | D 225 H | |

| 709129 | 03855 | Guanylate cyclase | C 35 R | Annotated as serine phosphatase in PCC 7942 |

| 731334-731576 | 03965 | ABC-transporter substrate-binding protein | Deletion of 243 bp | Annotated as adenine phosphoribosytransferase in PCC 7942 |

| 733938 | 03975 | Hypothetical protein | STOP 113 Q | 238 aa PilN-like protein in PCC 7942, confirmed by proteomics data |

| 891346 | 04780 | PpnK, inorganic polyphosphate/ATP-NAD kinase | D 260 E | |

| 1080351 | 05865 | Hypothetical protein | L 133 R (RFC) | 135 aa in UTEX 2973134 aa in PCC 7942 |

| 1113358 | 06025 | Molecular chaperone DnaK | G 196 S | |

| 1222741 | 06570 | Hydrolase | F 165 V | Annotated as peptidase M20D, amidohydrolase in PCC 7942 |

| 1222972 | 06570 | Hydrolase | R 247 G (RFC) | 395 aa in UTEX 2973252 aa in PCC 7942 |

| 1237531 | 06650 | CTP synthetase | A 294 V | |

| 1238113 | 06650 | CTP synthetase | R 488 H | |

| 1273424 | 06850 | Chorismate mutase | G 122 V (RFC) | 139 aa in UTEX 2973130 aa in 7942 |

| 1619501 | 08615 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase β subunit | P 378 Q | Confirmed by proteomics data |

| 1718274 | 09095 | Porin; major outer membrane protein | Silent | |

| 2249045 | 11685 | Anthranilate synthase, component I | V 329 G | |

| 2339739 | 12130 | Long-chain-fatty-acid CoA ligase | R 216 P | Confirmed by proteomics data |

| 2339502 | 12130 | Long-chain-fatty-acid CoA ligase | P 295 L | |

| 2364720 | 12285 | Glutamate synthase | L 1018 S | Confirmed by proteomics data |

| 2608863 | 13540 | Photosystem I assembly protein Ycf4 | F 39 L |

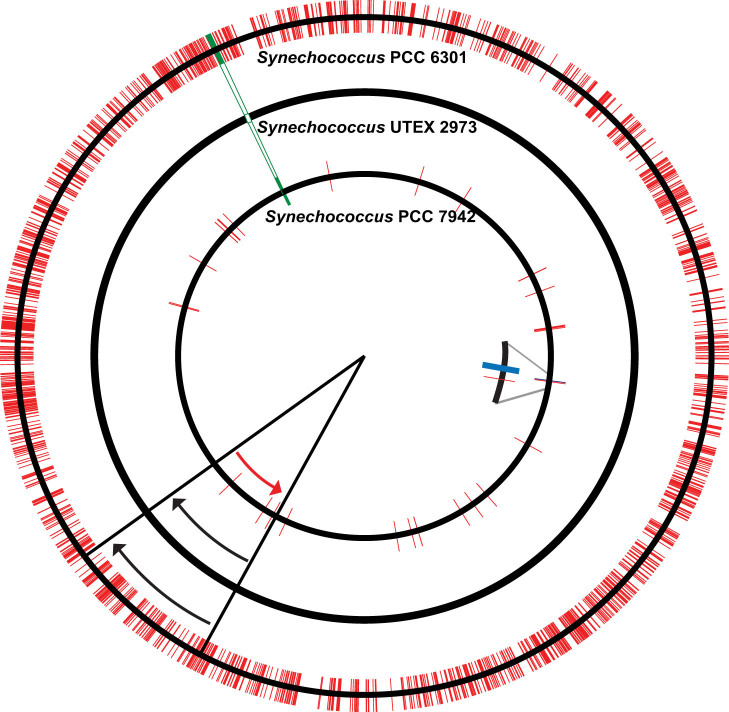

Figure 2. Circular maps comparing related cyanobacterial genomes.

Middle circle, Synechococcus UTEX 2973; outer circle, Synechococcus PCC 6301; inner circle, Synechococcus PCC 7942. (red bar), single nucleotide substitutions and indels compared to Synechococcus UTEX 2973; (green box), deletion; (blue box), insertion. Red and black arrows indicate the opposing orientations of the inverted region.

Table 4. SNPs and indels in the coding regions in the small plasmid of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 (CP_006473) compared to those in the small plasmid pUH24 in Synechococcus PCC 7942 (NC_004990). Corresponding amino acid changes in the encoded proteins are shown. RFC, Reading Frame Change.

| Nucleotide position in UTEX 2973 small plasmid | Locus tag (M744) | Protein | Amino acid changes | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 108 | Not an ORF | Hypothetical protein in PCC 7942 | ||

| 1038 | 14245 | Hypothetical protein | E 158 D | |

| 1039 | 14245 | Hypothetical protein | L 159 V | |

| 2460 | 14250 | Hypothetical protein | A 841 V (RFC) | 1019 aa in UTEX 2973876 aa in PCC 7942 |

| 4039 | 14250 | Hypothetical protein | K 314 N | |

| 4040 | 14250 | Hypothetical protein | Q 315 E | |

| 6809 | 14260 | Hypothetical protein | A 175 V (RFC) | 177 aa in UTEX 2973187 aa in PCC 7942 |

Surprisingly, the number of detected nucleotide differences between Synechococcus UTEX 2973 and PCC 7942 was orders of magnitude less than those between Synechococcus UTEX 2973 and Synechococcus PCC 6301 (~1600 SNPs and indels), the closest relative based upon strain history. Despite the fact that Synechococcus UTEX 2973 and PCC 7942 are 99.8% identical in their genome sequences, Synechococcus UTEX 2973 can grow more than twice as fast as Synechococcus PCC 7942. It is reasonable to hypothesize that one or more of the relatively small number of genes with the observed SNPs and indels determines how cells utilize available resources and thus controls the growth rate of these cyanobacterial cells.

In order to further compare these two strains at their proteome level, global proteomics analysis was performed for both cyanobacterial strains. In-depth LC-MS/MS proteomic analysis of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 identified peptides belonging to 1754 unique proteins (66% coverage), 1180 of which could be categorized into different functional groups (Fig. S1). As described above, Synechococcus UTEX 2973 and PCC 7942 are 99.8% identical in their genome sequences, so that most detected peptide sequences are indistinguishable between these two strains. However, due to the overall deep coverage, our MS data detected many of the amino acid changes that are predicted as a consequence of the SNPs between the two strains (Table 3 and 4).

A 5,764 bp sequence that contains six open reading frames in Synechococcus PCC 7942 was missing in Synechococcus UTEX 2973 (Fig. 2, Table S1). Although most of these genes do not have any annotated function, transcriptomics analysis (data not shown) indicated that these six genes are constitutively transcribed in Synechococcus PCC 7942, providing an intriguing avenue for further study. In addition, our proteomics study confirmed the presence of the protein products of five of these six genes in Synechococcus PCC 7942 (Table S1).

A previous study had indicated that there is a 188.6 kb inversion between the Synechococcus PCC 6301 and Synechococcus PCC 7942 genomes20. We determined that Synechococcus UTEX 2973 has the same genome arrangement in this inversion region as Synechococcus PCC 6301 (Fig. 2, Table S2). This inversion includes the coding region for a porin-like protein, and was proposed to be related to the natural competency (for DNA uptake) of these cyanobacterial cells20 (see below).

Ultrastructural analysis of Synechococcus UTEX 2973

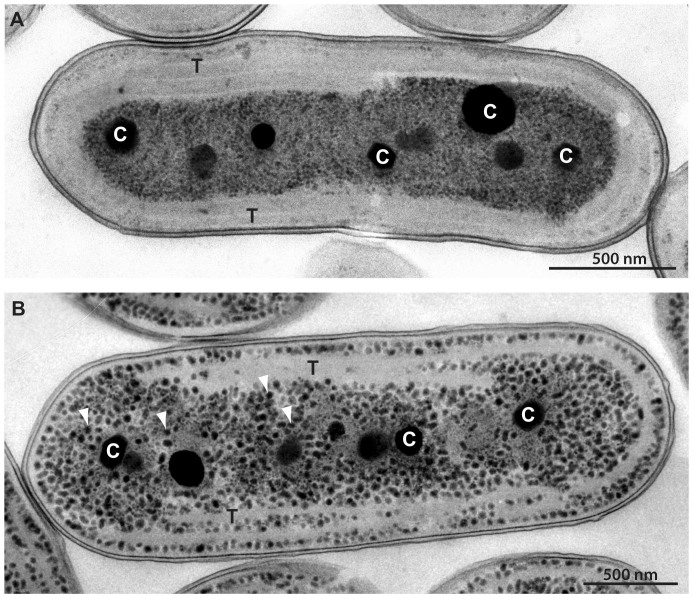

Cells of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 and Synechococcus PCC 7942 were examined by electron microscopy to identify structural differences between these strains at the subcellular level (Fig. 3). Both strains are rod-shaped cells typically > 2 µm in length. The size of the cells was similar between the two strains and did not appear to vary between growth in air and growth in 3% CO2. Intracellular organization was also similar between the strains when grown in air, with 2–3 thylakoid membrane layers forming evenly spaced concentric rings that followed the shape of the cell envelope. Carboxysomes and polyphosphate bodies were located in the central cytoplasmic region, and the number of these bodies was similar in the two strains. When grown in 3% CO2, the most striking difference between the two strains was the appearance of numerous electron-dense bodies in Synechococcus PCC 7942 (Fig. 3B). These bodies were found throughout the entire cell, including between and surrounding the thylakoid membrane layers, and coincided with a disorganized appearance of the thylakoid membranes and a decrease in the number of thylakoid layers to 1–2 in most cells. These electron-dense bodies were nearly completely absent in Synechococcus UTEX 2973 (Fig. 3A) when grown in 3% CO2. These bodies in Synechococcus 7942 are spherical or slightly elongated and approximately 30 nm in size. To our knowledge, the occurrence of such inclusions under high CO2 conditions has not been previously observed in Synechococcus strains.

Figure 3. Ultrastructural comparison of Synechococcus strains.

Electron micrographs of (A) Synechococcus UTEX 2973 and (B) Synechococcus PCC 7942 grown in 3% CO2. Labeled are carboxysomes (C) and thylakoid membranes (T). White arrowheads point to the numerous electron-dense bodies. Bar = 500 nm.

Genetic manipulation of Synechococcus UTEX 2973

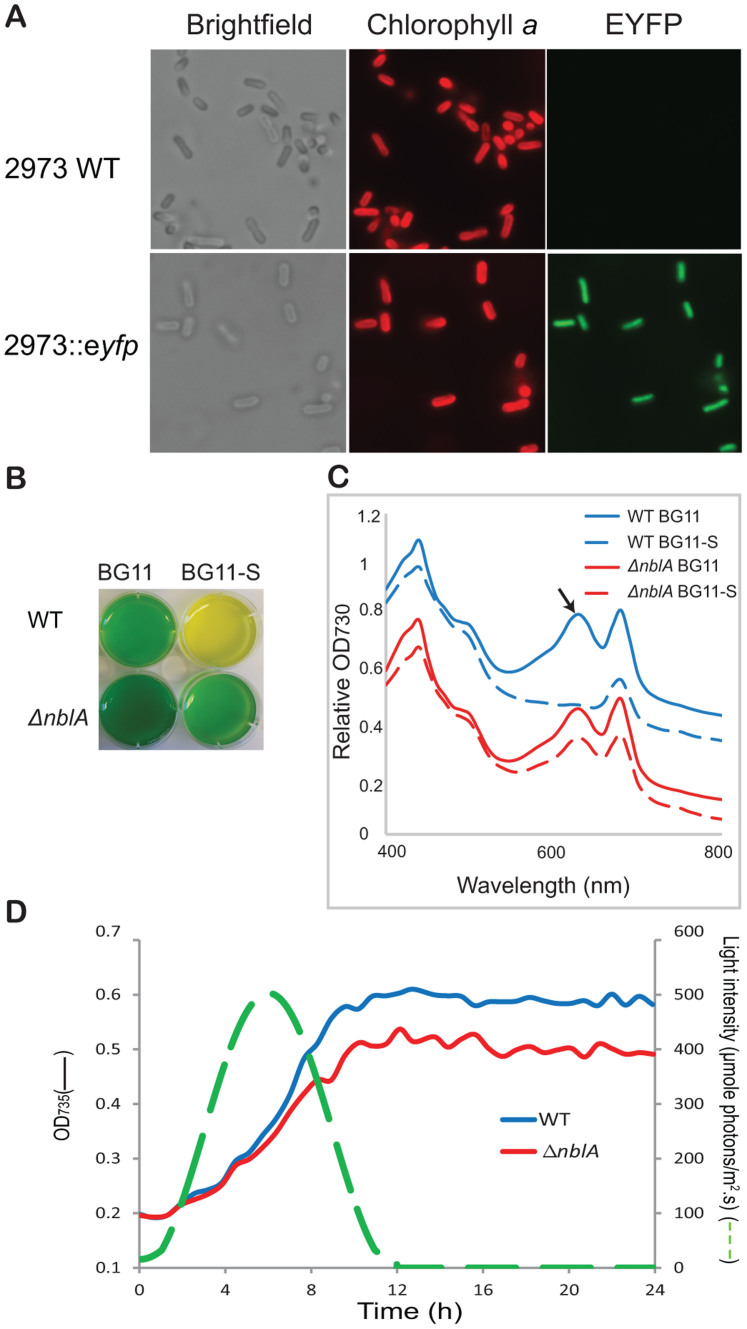

Amenability to facile genetic manipulation is a key requirement for a strain to be used as a chassis in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering applications. Three widely used cyanobacterial strains, Synechocystis 680321, Synechococcus PCC 794222,23 and Synechococcus PCC 700224, are naturally competent, actively taking up exogenous DNA from their surroundings and incorporating it into their genomes. However, this feature is not common among bacterial strains, so that other widely studied cyanobacteria, including some nitrogen fixing strains of Nostoc and Anabaena, are routinely genetically manipulated through conjugative transfer of DNA from E. coli cells25. Previous studies of conjugative DNA transfer to cyanobacterial cells have established a well developed system with several conjugal, helper and suicide or replicable cargo plasmids available for use26. We determined that Synechococcus UTEX 2973 cells were not naturally competent, like its close relative Synechococcus PCC 6301. However, conjugation through tri-parental mating22 (also see Materials and Methods) was successfully applied to Synechococcus UTEX 2973 cells with a stable efficiency of ~1–2 × 10−5 colonies/plated cell. In order to clearly show the occurrence of transgene introduction using a replicable cargo plasmid or homologous recombination using a suicide cargo plasmid, mutants were generated with distinct phenotypes. As a transgene, the gene encoding an enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) gene was introduced into Synechococcus UTEX 2973 cells on the self replicating vector pTrc-EYFP with expression of the transgene controlled by the Trc promoter15. Mutant cells exhibited strong fluorescence from YFP (Fig. 4A), so that the intensity of emitted fluorescence from EYFP-expressing mutant cells was about ~470 times higher than that from wild type (WT) cells.

Figure 4. Directed gene manipulation in Synechococcus UTEX 2973.

(A) Light micrographs of WT cells and EYFP-expressing transformants. Shown are brightfield (left column), chlorophyll a fluorescence (middle column), and EYFP fluorescence (right column) images. (B) Color phenotypes of WT and ΔnblA mutant cells. Under sulfur deprivation (BG11-S), WT cells bleached but ΔnblA cells did not. (C) Absorption spectra of WT (blue) and ΔnblA (red) cells. Solid lines, sulfur replete; dashed lines, sulfur deprived. The phycocyanin peak at 625 nm is designated by the arrow. Curves were vertically offset for clarity. (D) Growth curves of WT (blue) and ΔnblA (red) cultures under varying irradiance (green dashed line) to mimic a natural 12 h light/12 h dark cycle.

To demonstrate targeted gene replacement in Synechococcus UTEX 2973, we inactivated the nblA gene. In other cyanobacteria, the nblA gene has been shown to function in pathways involved in regulation of light harvesting, and is particularly noted for its role in phycobilisome degradation under nutrient starvation conditions27. In Synechococcus PCC 7942, nblA transcripts accumulate to high levels when cells are starved for nitrogen or sulfur, and the resulting loss of phycobilisomes lends cultures a characteristic bleached color28. The ΔnblA mutant was engineered by homologous recombination of a suicide cargo plasmid with the nblA gene in the chromosome of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 (see Materials and Methods and Fig. S2). WT cells of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 turned yellow in BG11-S media within 7 days (Fig. 4B). Cells of the Synechococcus UTEX 2973 ΔnblA mutant, in which the nblA gene was completely deleted, still appeared blue-green in BG11-S after 7 days (Fig. 4B). Whole cell absorbance spectra (see Materials and Methods) showed that Synechococcus UTEX 2973 WT and ΔnblA mutant cells growing in regular BG11 medium had a similar ratio of phycobilin absorbance at 630 nm vs. chlorophyll a absorbance at 680 nm (~0.94) (Fig. 4C). This ratio decreased considerably (to ~ 0.7–0.8) when Synechococcus UTEX 2973 WT cells were grown without combined sulfur. However, this ratio did not significantly change in Synechococcus UTEX 2973 ΔnblA mutant cells grown under the same nutrient starvation conditions (Fig. 4C), confirming that the engineered ΔnblA mutant strain of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 had a similar phenotype as the ΔnblA mutant of Synechococcus PCC 794228. Under nutrient replete condition, the ΔnblA mutant strain of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 showed similar growth rates compared to WT cells under constant light conditions, an observation similar to that of the Synechococcus PCC 7942 ΔnblA mutant strain28. Interestingly, the newly generated ΔnblA mutant strain exhibited slower growth compared to the WT Synechococcus UTEX 2973 strain when cells were grown under an illumination condition that mimicked a natural day-night cycle (see Methods section). This new finding indicates that the presence of the NblA protein provides a growth advantage to cyanobacterial cells under natural conditions.

Discussion

A rapidly growing cyanobacterial strain that can be genetically manipulated would serve as an ideal candidate for broad research purposes, including studies that focus on understanding cyanobacterial systems and those that utilize cyanobacteria to produce valuable products. As mentioned earlier, none of the currently used model cyanobacterial strains can grow under autotrophic conditions as fast as yeast or other microbes used in industrial applications. In order to fill this gap, we looked for “new” cyanobacterial strains, and Synechococcus UTEX 2973 stood out as strain that grew especially rapidly. For example, Synechococcus UTEX 2973 grew faster than Synechococcus PCC 6301, Synechococcus PCC 7942, Synechococcus PCC 7002 and Synechocystis PCC 6803 (Fig. 1A). Surprisingly, Synechococcus PCC 6301 and Synechococcus UTEX 625 have been described as identical according to the Pasteur Culture Collection (PCC). However, our axenic cultures of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 behaved differently than cultures of Synechococcus PCC 6301. Whole genome sequencing confirmed that Synechococcus UTEX 2973 and Synechococcus PCC 6301 are definitely two uniquely different strains. Previously published data on the doubling time of Synechococcus PCC 630129 as well as our current growth data (Table 1) suggest that the growth of Synechococcus PCC 6301 is significantly slower than the Anacystis nidulans strain that was isolated in 1952 and studied in 195518. In contrast, growth of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 (this study) is similar to that of the original Anacystis nidulans strain18. An interesting observation from genome alignments (Fig. 2) is that the Synechococcus UTEX 2973 genome is more similar to the Synechococcus PCC 7942 genome, even though these two strains were isolated from different geographical locations. Raven and coworkers have recently postulated30 that the doubling times of photosynthetic organisms are directly correlated with their genome sizes. Our findings challenge this hypothesis, since the genome sizes of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 and Synechococcus PCC 7942 are nearly identical (Table 2), whereas their doubling times are significantly different. The large deletion region in the Synechococcus UTEX 2973 genome compared to the genomes of Synechococcus PCC 7942 and Synechococcus PCC 6301 presents an intriguing avenue for further study. Six genes present in this region are constitutively transcribed in Synechococcus PCC 7942. Most notably, genes that contained SNPs, indels and that are within the missing region in Synechococcus UTEX 2973 could be determinants of the growth rates of the cells.

In this study, we have generated global proteomics data for both Synechococcus UTEX 2973 and PCC 7942. These data support the genome sequencing data by showing corresponding amino acid differences between the two strains that were predicted by nucleotide sequence comparison (Table 3). Moreover, Synechococcus PCC 7942 is a widely used model cyanobacterial strain; however, its global proteome has not been analyzed thus far. Previous proteomic analysis based on 2D-PAGE identified a small fraction (~2%) of the total predicted proteome of Synechococcus PCC 794231. Our global proteomic data with a coverage of 68% would be a valuable resource for the research community.

We have reported the occurrence of many electron-dense bodies in Synechococcus PCC 7942 under 3% CO2 conditions, and the absence of these bodies under the same conditions in Synechococcus UTEX 2973. Although the exact nature of these bodies is uncertain, their shape, size and number are similar to the glycogen granules that have previously been identified in Synechococcus PCC 794232. However, in the previous study, glycogen granules were only visualized as electron-dense particles after treatment with a polysaccharide stain, whereas under our conditions these granules appear electron dense with standard treatment. If these are glycogen stores, the lack of these bodies in Synechococcus UTEX 2973 under high CO2 conditions might suggest fundamental differences in carbon utilization in these two strains. We hypothesize that Synechococcus UTEX 2973 may channel fixed carbon into biomass for rapid growth, while Synechococcus PCC 7942 stores carbon as glycogen.

Culture conditions that are optimal for the rapid growth of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 (38–41°C, 3% CO2 and 500 µmole photons·m−2·s−1 using BG11 media) are utilized in many laboratories, and no special nutrients, such as vitamins, are required for the growth of this cyanobacterial strain. This strain grows so rapidly, in culture volumes ranging from 50 ml to 100 L, such as in a photobioreactor, that contamination was not apparent even when growth media were not sterilized and the systems were semi-open to the outside. On solid BG11 plates, at 38°C and under 200 μmoles photons·m−2·s−1 light and in ambient air, single colonies of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 were visible within 2 days after plating from a very dilute liquid culture, and these colonies were large enough for passage by the third day. Such reduced colony formation time is immensely beneficial for genetic manipulation studies. Furthermore, in the nblA deletion experiment, transformed cells from a single colony were completely segregated in the first round after patching. The same result was observed in a subsequent experiment, where a foreign gene was inserted into the chromosome of Synechococcus UTEX 2973. Therefore, the elapsed time from conjugation to segregated mutant was approximately 8 days for this strain. In our experience, the same process in Synechocystis 6803 (~8 days or more for colonies of mutants to show16, plus several rounds of segregation) usually takes nearly one month. Expression of EYFP and inactivation of the nblA gene were two of many genetic manipulations (data not shown) that we have performed with Synechococcus UTEX 2973. In addition, we have determined that antibiotic resistance genes, including those conferring kanamycin resistance (Tn903), chloramphenicol resistance (cat), gentamicin resistance (accC1) and spectinomycin/streptomycin resistance (omega cassette), that have been used in other model cyanobacteria, also function in Synechococcus UTEX 2973.

According to our observations, Synechococcus UTEX 2973, like Synechococcus PCC 6301, is not naturally competent for transformation. This is unlike the naturally competent Synechococcus PCC 7942. Porin-like sequences near the edges of the large genomic inversion region (Fig. 2) have been hypothesized to be responsible for such natural transformability20. Synechococcus UTEX 2973 has the same genome structure as Synechococcus PCC 6301 on that inversion. According to this hypothesis, it would be possible to make Synechococcus UTEX 2973 naturally competent by flipping the inverted region on the genome. However, that is not necessary since conjugation requires limited extra time, and in some instances, conjugation may be the preferred route of DNA transfer, particularly when a large segment of foreign DNA is to be transferred or if merodiploids (single recombination events) are desired26. With attributes including rapid growth, amenability to genetic manipulation, and fast segregation, Synechococcus UTEX 2973 is expected to serve as an ideal cyanobacterial system for a wide range of applications.

Methods

Cyanobacterial strains and growth conditions

The Pakrasi lab procured the Synechococcus elongatus UTEX 625 strain from the UTEX algae culture collection (www.utex.org). Synechococcus 625 was not axenic when it was frozen and stored at −80°C in 2008. In addition, it could not grow at 38°C (see Results section). The frozen sample of Synechococcus UTEX 625 was thawed in 2011 and a single colony from the recovered culture, grown at 38°C, was picked and propagated. Cultures from this single colony were unialgal and no bacterial contamination was found when tested on LB medium. In addition, this strain could grow fast under photoautotrophic condition (see Results section). This clean strain was deposited to the UTEX algae culture collection, and a new number, UTEX 2973, was assigned to it. Synechococcus elongatus PCC 6301 and PCC 7942 were procured from the Pasteur Culture Collection of Cyanobacteria (PCC). Except when otherwise indicated, these strains were maintained in liquid BG11 or on solid BG11 plates19 at 38°C under continuous white light (70 µmole photons·m−2·s−1). Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 was obtained from Prof. Toivo Kallas (University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh) and was grown at 38°C. Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 was from the Pakrasi lab and was grown at 30°C. Growth under continuous light was measured as OD730nm on a Multi-cultivator MC 1000-OD (Photon Systems Instruments, Drasov, Czech Republic), and growth under sine wave illumination, modulated to simulate natural sunlight, was measured on an FMT-150 photobioreactor as OD73533 (Photon Systems Instruments, Drasov, Czech Republic). CO2 gas flow rate at 1 ml/min and 3% (v/v) to every ml of culture was precisely controlled by a custom mixing system (Qubit Systems Inc, Kingston, Ontario). For doubling time measurements, five sets of measurements were made for each strain. Points were plotted as semi-log graphs and the specific growth rate K’ during the early exponential phase for each measurement was determined. The doubling time was then calculated as Ln2/K’. For sine wave illumination growth experiments, the mean value of OD735 at each time point was plotted. Blue and red light intensities were both set to change from 0 µmole photons·m−2·s−1 at 0 h to 250 µmole photons·m−2·s−1 at 6 h, and then decrease to 0 at 12 h. Red light increased more steeply during morning and evening hours than blue light. This setting of the photobioreactors is based on the description in ref. 33. For large scale (100 L culture volumes) growth, algal photobioreactors (Photon Systems Instruments, Drasov, CZ) in the Advanced Coal & Energy Research Facility at Washington University in St. Louis (http://cccu.wustl.edu/research-facil.php) were used. Biomass of cyanobacterial cultures was determined using a method slightly modified from that described previously34.

Whole genome sequencing

Illumina genome sequencing was performed at the Genome Technology Access Center (GTAC) at Washington University. Genomic DNA was isolated and sonicated to an average size of 175 bp. The DNA fragments were repaired to produce blunt ends, modified with a 3’ ‘A’ base overhang, and ligated to Illumina's standard sequencing adapters. The ligated fragments were amplified for 10 cycles incorporating a unique indexing sequence tag. The resulting libraries were sequenced as 101 nucleotide paired end reads using the Illumina HiSeq-2000. Sequence reads were mapped to Synechococcus PCC 6301 and Synechococcus PCC 7942 genome data obtained from GenBank (NC_006576 and NC_007604, respectively) using Novoalign. SAMtools was used to identify SNPs between the two strains. Dindel was used to identify indels. Pindel and custom analyses were used to identify structural rearrangements. 454 genome sequencing was also performed in parallel (MOgene LC, St. Louis, MO) and the genome was assembled de novo using Newbler 2.8.

Assembled chromosome and two plasmid sequences of Synechococcus UTEX 2973 were deposited to Genbank (Accession number: CP006471 to CP006473).

Sample preparation for Proteomics and LC-MS/MS analysis

Cell suspensions of both Synechococcus UTEX 2973 and Synechococcus PCC 7942 were disrupted and digested into tryptic peptide form as previously described35,36. The resulting isolated peptide samples were separated via a high pH HPLC approach (Agilent 1200 HPLC System) as previously described37, resulting in the automated collection of 96 fractions, which were lyophilized and reconstituted into 24 fractions prior to LC-MS/MS analysis. Fractionated samples were subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis using a Thermo Scientific LTQ mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA) coupled with an in-house electrospray ionization interface as previously described38,39,40. LC–MS/MS raw data were converted into data files using Bioworks Cluster 3.2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cambridge, MA, USA), and the MSGF+ algorithm was used to search MS/MS spectra against Synechococcus UTEX 2973 and Synechococcus PCC 7942 databases (NCBI). Key search parameters included 20 ppm tolerance for precursor ion masses, partial tryptic search, with decoy database searching methodology41 used to control the false discovery rate at the unique peptide level to ~0.1%42. Global proteomics data for both Synechococcus UTEX 2973 and Synechococcus PCC 7942 have been uploaded to PeptideAtlas with the dataset identifier number of PASS00399.

Electron microscopy

Cells were prepared for electron microscopy as described previously43. Culture aliquots (approximately 20 ml) were centrifuged, and the pellet was resuspended in a small volume, transferred to planchettes with 100–200 µm-deep wells, and frozen in a Baltec High Pressure Freezer (Bal-Tec). Samples were freeze-substituted in 2% osmium/acetone (3 d at −80°C, 15 h at −60°C, slow thaw to room temperature) and embedded in Spurr's resin. Thin sections (approximately 80 nm) were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Digital images were viewed and collected using a LEO 912 transmission electron microscope operating at 120 kV and a ProScan digital camera.

Genetic modification of Synechococcus UTEX 2973

Tri-parental conjugation was used to generate mutants of Synechococcus UTEX 297322, with pRL443 as the conjugal plasmid and pRL623 as the helper plasmid44. Shuttle or suicide vectors carrying the gene of interest were first transformed into competent HB101 E. coli cells that already contained the pRL623 helper plasmid to form cargo strains. 100 μl overnight cultures of the conjugal strain (RL443) and 100 μl overnight cultures of the cargo strain were washed with distilled water and mixed with pre-washed Synechococcus UTEX 2973 cells (200 μl at OD730 ~0.4-0.6). Mixed cells were plated onto BG11+5% LB (v/v) agar plates containing selective antibiotics. Plates were placed under bright continuous illumination (200 μmole photons·m−2·s−1). Mutant colonies were usually apparent within 3–4 days. The shuttle vector pTrc-EYFP for eYFP expression is a derivative of pPMQAK1-BBa_P101015. The suicide plasmid pSL2231 used to delete the nblA gene in Synechococcus UTEX 2973 was a derivative of pBR322. The coding region of the nblA gene was targeted for deletion from the chromosome after homologous recombination. 581 bp upstream and 558 bp downstream of nblA coding region were amplified using primers N1: ATATAAGCTTGATGCGCAGATAGCCTGACTGTTCC/N2: CCAGGATTGGGAGGCTCCGGCACTGCAGATGAAC; and P1: TCGACTCTACCGTGTGCAAGACTTGCCCGCGAAG/P2: ATATGGATCCATGCTGCTGGAGTTCTACGCCGAC, respectively. The upstream and downstream sequences were fused with a chloramphenicol resistance gene (CmR, cat, amplified using primers O1: AGCCTCCCAATCCTGGTGTCCCTGTTGATACC/O2: CACACGGTAGAGTCGACGAATTTCTGCCATTCATCC) by fusion PCR to form an upstream- CmR -downstream fragment. This fragment was inserted into the pBR322 vector between HindIII and BamHI sites to form the plasmid pSL2231 (Figure S2).

Fluorescence microscopy

Concentrated cells of WT and EYFP mutant strains from 2-day old cultures were deposited onto glass slides that were previously coated with 2% polyethyleneimine. Cells were imaged using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope equipped with a Photometrics Cool Snap ES CCD camera (Roper Scientific). Illumination was provided by a metal halide light source (X-Cite). Filter sets (Chroma) were as follows: YFP was detected using a 480/30 nm excitation filter, a 505 nm dichroic beam splitter, and a 535/40 nm emission filter. Chlorophyll fluorescence was detected using a 560/40 nm excitation filter, a 595 nm dichroic beam splitter, and a 630/60 nm emission filter. A 300 ms exposure time was used for imaging.

Whole cell absorbance spectra

These spectra were obtained using a μQuant plate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT). 150 μl culture volumes in 96-well plates were measured from 400 nm to 800 nm. Absorption curves were vertically offset (indicated by “relative OD”) for comparison purposes.

Supplementary Material

Dataset 1

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Pakrasi lab for helpful discussions, and Howard Berg at the Integrated Microscopy Facility of Donald Danforth Plant Science Center for TEM assistance. Work at Washington University was primarily supported by U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research. The electron microscopy study was supported as part of the Photosynthetic Antenna Research Center (PARC), an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Award Number DE-SC 0001035. LC-MS/MS proteomics work was performed in the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a U. S. Department of Energy Office of Biological and Environmental Research national scientific user facility located at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland, Washington. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory is operated by Battelle for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC05-76RLO 1830. Work at University of Texas at Austin was supported by the National Science Foundation under Award number DBI-1201881.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions J.Y., R.D.H., R.D.S., D.W.K., J.J.B. and H.B.P. designed research; J.Y., M.L., P.F.C., J.M.J. performed research; J.Y., M.L., J.M.J. analyzed the data; J.Y., M.L. and H.B.P. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Lu X. A perspective: photosynthetic production of fatty acid-based biofuels in genetically engineered cyanobacteria. Biotechnol Adv 28, 742–746 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidorn T. et al. Synthetic biology in cyanobacteria engineering and analyzing novel functions. Methods Enzymol 497, 539–579 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana N., Van der Kooy F., Van de Rhee M. D., Voshol G. P. & Verpoorte R. Renewable energy from cyanobacteria: energy production optimization by metabolic pathway engineering. Appl Microbiol Biot 91, 471–490 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll A. H. in The Cyanobacteria: Molecular biology, Genomics and Evolution (eds Herrero, A. & Flores, E.) Ch. 1, 1–20 (Caister Academic Press, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Ono E. & Cuello J. L. Carbon dioxide mitigation using thermophilic cyanobacteria. Biosyst Eng 96, 129–134 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Peralta-Yahya P. P., Zhang F., del Cardayre S. B. & Keasling J. D. Microbial engineering for the production of advanced biofuels. Nature 488, 320–328 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burja A. M., Banaigs B., Abou-Mansour E., Burgess J. G. & Wright P. C. Marine cyanobacteria - a prolific source of natural products. Tetrahedron 57, 9347–9377 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Sheng J. & Curtiss R. 3rd Fatty acid production in genetically modified cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 6899–6904 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg P., Park S. & Melis A. Engineering a platform for photosynthetic isoprene production in cyanobacteria, using Synechocystis as the model organism. Metab Eng 12, 70–79 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver J. W., Machado I. M., Yoneda H. & Atsumi S. Cyanobacterial conversion of carbon dioxide to 2,3-butanediol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 1249–1254 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan E. I. & Liao J. C. Metabolic engineering of cyanobacteria for 1-butanol production from carbon dioxide. Metab Eng 13, 353–363 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund E. et al. Production of squalene in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. PloS one 9, e90270 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reppas N. B. & Ridley C. P. inventors; Joule Unlimited, Inc, assignee. Methods and compositions for the recombinant biosynthesis of n-alkanes. United States patent US 7,794,969 B1. 2010 Sep 14.

- McNeely K., Xu Y., Bennette N., Bryant D. A. & Dismukes G. C. Redirecting reductant flux into hydrogen production via metabolic engineering of fermentative carbon metabolism in a cyanobacterium. Applied and Environmental Microbiol. 76, 5032–5038 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H. H., Camsund D., Lindblad P. & Heidorn T. Design and characterization of molecular tools for a synthetic Biology approach towards developing cyanobacterial biotechnology. Nucleic Acids Res 38, 2577–2593 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labarre J., Chauvat F. & Thuriaux P. Insertional mutagenesis by random cloning of antibiotic resistance genes into the genome of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis strain PCC 6803. J Bacteriol 171, 3449–3457 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird A. J., Turner-Cavet J. S., Lakey J. H. & Robinson N. J. A carboxyl-terminal Cys2/His2-type zinc-finger motif in DNA primase influences DNA content in Synechococcus PCC 7942. J Biol Chem 273, 21246–21252 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratz W. A. & Myers J. Nutrition and growth of several blue-green algae. Am J Bot 42, 282–287 (1955). [Google Scholar]

- Allen M. M. Simple conditions for the growth of unicellular blue-green algae on plates. J Phycol 4, 1–4 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita C. et al. Complete nucleotide sequence of the freshwater unicellular cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 6301 chromosome: gene content and organization. Photosynth Res 93, 55–67 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barten R. & Lill H. DNA-Uptake in the Naturally Competent Cyanobacterium, Synechocystis Sp PCC-6803. FEMS Microbiol Lett 129, 83–88 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Tsinoremas N. F., Kutach A. K., Strayer C. A. & Golden S. S. Efficient gene transfer in Synechococcus sp. strains PCC 7942 and PCC 6301 by interspecies conjugation and chromosomal recombination. J Bacteriol 176, 6764–6768 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsborg O., Eldholm V. & Havarstein L. S. Natural genetic transformation: prevalence, mechanisms and function. Res Microbiol 158, 767–778 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y. et al. Expression of genes in cyanobacteria: adaptation of endogenous plasmids as platforms for high-level gene expression in Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Methods in Molecular Biol. 684, 273–293 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffing A. M. Engineered cyanobacteria teaching an old bug new tricks. Bioengineered Bugs 2, 136–149 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai J. & Wolk C. P. Conjugal transfer of DNA to cyanobacteria. Methods Enzymol 167, 747–754 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman A. R., Bhaya D. & He Q. Tracking the light environment by cyanobacteria and the dynamic nature of light harvesting. J Biol Chem 276, 11449–11452 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier J. L. & Grossman A. R. A small polypeptide triggers complete degradation of light-harvesting phycobiliproteins in nutrient-deprived cyanobacteria. EMBO J 13, 1039–1047 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto T. & Bryant D. A. Nitrate transport and not photoinhibition limits growth of the freshwater cyanobacterium Synechococcus species PCC 6301 at low temperature. Plant Physiol. 119, 785–794 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven J. A., Beardall J., Larkum A. W. & Sanchez-Baracaldo P. Interactions of photosynthesis with genome size and function. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences 368, 20120264 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koksharova O. A., Klint J. & Rasmussen U. Comparative proteomics of cell division mutants and wild-type of Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. Microbiology 153, 2505–2517 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman D. M. & Sherman L. A. Effect of iron deficiency and iron restoration on ultrastructure of Anacystis nidulans. J Bacteriol 156, 393–401 (1983). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerveny J., Setlik I., Trtilek M. & Nedbal L. Photobioreactor for cultivation and real-time, in-situ measurement of O2 and CO2 exchange rates, growth dynamics, and of chlorophyll fluorescence emission of photoautotrophic microorganisms. Eng Life Sci 9, 247–253 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Page L. E., Liberton M. & Pakrasi H. B. Reduction of photoautotrophic productivity in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 by phycobilisome antenna truncation. Applied and Environmental Microbiol. 78, 6349–6351 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aryal U. K. et al. Dynamic proteome analysis of Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142 under constant light. Journal of Proteome Research 11, 609–619 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel T. E. et al. Proteome analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi response to environmental change. PloS one 5, e13800 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Reversed-phase chromatography with multiple fraction concatenation strategy for proteome profiling of human MCF10A cells. Proteomics 11, 2019–2026 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesay E. A. et al. Fully automated four-column capillary LC-MS system for maximizing throughput in proteomic analyses. Analytical Chem. 80, 294–302 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie F., Liu T., Qian W. J., Petyuk V. A. & Smith R. D. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-based quantitative proteomics. J Biol Chem 286, 25443–25449 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly R. T. et al. Chemically etched open tubular and monolithic emitters for nanoelectrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Analytical chemistry 78, 7796–7801 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian W. J. et al. Probability-based evaluation of peptide and protein identifications from tandem mass spectrometry and SEQUEST analysis: the human proteome. Journal of Proteome Research 4, 53–62 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Gupta N. & Pevzner P. A. Spectral probabilities and generating functions of tandem mass spectra: a strike against decoy databases. Journal of Proteome Research 7, 3354–3363 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberton M., Austin J. R. 2nd, Berg R. H. & Pakrasi H. B. Unique thylakoid membrane architecture of a unicellular N2-fixing cyanobacterium revealed by electron tomography. Plant Physiol. 155, 1656–1666 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai J., Vepritskiy A., Muro-Pastor A. M., Flores E. & Wolk C. P. Reduction of conjugal transfer efficiency by three restriction activities of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol 179, 1998–2005 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Dataset 1