Abstract

Although quinolone resistance results mostly from chromosomal mutations, it may also be mediated by a plasmid-encoded qnr gene in members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Thus, 297 nalidixic-acid resistant strains of 2,700 Escherichia coli strains that had been isolated at the Bicêtre Hospital (Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France) in 2003 were screened for qnr by PCR. A single E. coli isolate that carried a ca. 180-kb conjugative plasmid encoding a qnr determinant was identified. It conferred low-level resistance to quinolones and was associated with a chromosomal mutation in subunit A of the topoisomerase II gene. The qnr gene was located on a sul1-type class 1 integron just downstream of a conserved region (CR) element (CR1) comprising the Orf513 recombinase. Promoter sequences for qnr expression overlapped the extremity of CR1, indicating the role of CR1 in the expression of antibiotic resistance genes. This integron was different from other qnr-positive sul1-type integrons identified in American and Chinese enterobacterial isolates. In addition, plasmid pQR1 carried another class 1 integron that was identical to In53 from E. coli. The latter integron possessed a series of gene cassettes, including those coding for the extended-spectrum β-lactamase VEB-1, the rifampin ADP ribosyltransferase ARR-2, and several aminoglycoside resistance markers. This is the first report of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in Europe associated with an unknown level of plasmid-mediated multidrug resistance in Enterobacteriaceae.

Plasmid-mediated resistance to quinolones was first reported in 1998 in a Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical strain isolated in 1994 in Birmingham, Ala. (10). Plasmid pMG252 of that isolate codes for a 218-amino-acid protein of the pentapeptide repeat family (11) that protects DNA from quinolone binding (21). This Qnr determinant confers resistance to nalidixic acid and increases the MICs of fluoroquinolones by four- to eightfold (10, 21, 23).

Then, qnr-like genes were identified in conjugative plasmids that varied in size from 54 to >180 kb in Escherichia coli and K. pneumoniae isolates in Shanghai, China, and the United States, respectively (19, 21-24). No qnr-like genes have been identified from other parts of the world, including Europe (5, 19). The qnr gene has been identified in complex In4 family class 1 integrons (21, 24), known as complex sul1-type integrons. Sul1-type integrons possess duplicated qacEΔ1 and sul1 genes that surround a sequence (usually orf513) that may act as a recombinase for mobilization of the antibiotic resistance genes located nearby (e.g., qnr, blaCTX-M, and ampC). The qnr gene is not associated with the 59-bp element, although common integron-associated resistance genes are (15). The definition of the conserved region (CR) established recently indicates that it consists of an orf513 gene that encodes a recombinase and a right-hand boundary that may act as a recombination crossover site (15).

Several β-lactamase genes are associated with qnr-positive plasmids, such as those coding for the plasmid-mediated cephalosporinase FOX-5, the clavulanic acid-inhibited extended-spectrum class A β-lactamases SHV-7 and CTX-M-9, and the narrow-spectrum penicillinase PSE-1 (1, 10, 21-24).

In the study described here, we have investigated the frequency of the qnr gene in nalidixic-acid resistant clinical isolates of E. coli, since this species (i) is the most frequent enterobacterial species identified from human specimens and (ii) is involved in nosocomial and community-acquired infections. The transferability of quinolone resistance, the associated chromosomally encoded mechanisms of resistance to quinolones, antimicrobial coresistance, β-lactamase genes, plasmids, integrons, and the promoter sequences for qnr expression were determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Of 2,700 clinical isolates of E. coli collected at Bicêtre Hospital in 2003, 297 nalidixic-acid resistant strains (MICs, greater than or equal to 32 μg/ml) were retained for this study. Each strain was from a unique patient. Identification of the E. coli clinical isolates was performed with the API 20E system (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France).

Additional strains tested were E. coli J53/pMG252, which was used as a positive control for the qnr gene (10); E. coli MG-1, which was used as a positive control for blaVEB-1 (12); E. coli NCTC 50192, which contained 154-, 66-, 48-, and 7-kb reference plasmids (2); E. coli J53 Azr (resistant to azide), which was used as the recipient for conjugation (10); and E. coli reference strains, which were used for outer membrane protein (OMP) analysis (17).

Screening for qnr gene and conjugation.

The strains were screened for the presence of the qnr gene by PCR with primers QnrA and QnrB (Table 1). Qnr-positive strains produced a 661-bp amplification product when they were resuspended, and boiled colonies of clinical strains and standard PCR techniques were used (20).

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| ORF513D3 | 5′-CTCACGCCCTGGCAAGGTTT-3′ | This study |

| ORF513D5 | 5′-CTTTTGCCCTAGCTGCGGT-3′ | This study |

| CMLA-B | 5′-TGGGATTTGATGTACTTTCCG-3′ | 13 |

| CMLA-F | 5′-CAAAAACTTTAGTTGGCGGTAC-3′ | 13 |

| aadB-B | 5′-CGCATATCGCGACCTGAAAGC-3′ | 13 |

| aadB-F | 5′-GATACACAAAATTCTAGCTGCG-3′ | 13 |

| arr-2F | 5′-AATTACAAGCAGGTGCAAGGA-3′ | 13 |

| arr-2B | 5′-TTCAATGACGTGTAAACCACG-3′ | 13 |

| 5′CS | 5′-GGCATCCAAGCAGCAAG-3′ | 13 |

| 3′CS | 5′-AAGCAGACTTGACCTGA-3′ | 13 |

| VEB-1A | 5′-CGACTTCCATTTCCCGAT GC-3′ | 13 |

| VEB-1B | 5′-GGACTCTGCAACAAATACGC-3′ | 13 |

| VEB-INV3 | 5′-GAACAGAATCAGTTCCTCCG-3′ | This study |

| VEB-INV4 | 5′-ACGAAGAACAAATGCACAAGG-3′ | This study |

| OXA-10CASB | 5′-CTTTGTTTT AGCCACCAATGATG-3′ | 13 |

| OXA-10CASF | 5′-TTAGGCCTCGCCGAAGCG-3′ | 13 |

| OrfG-B | 5′-GTCATTTTGAACTGCATTACC-3′ | This study |

| IS26A | 5′-CTTACCAGGCGCATTTCGCC-3′ | This study |

| AAC1-F | 5′-GTGAATTATTGCGGAATGCAGC | 12 |

| Sul1A | 5′-CTT CGATGAGAGCCGGCGGC-3′ | This study |

| Sul1B | 5′-GCAAGGCGGAAACCCGCGCC-3′ | This study |

| QnrA | 5′-GGGTATGGATATTATTGATAAAG-3′ | 24 |

| QnrB | 5′-CTAATCCGGCAGCACTATTA-3′ | 24 |

| GyrA6 | 5′-CGACCTTGCGAGAGAAAT-3′ | 8 |

| gyrA631R | 5′-GTTCCATCAGCCCTTCAA-3′ | 8 |

| ParCF43 | 5′-AGCGCCTTGCGTACATGAAT-3′ | 7 |

| ParCF981 | 5′-GTGGTAGCGAAGAGGTGGTT-3′ | 7 |

| PreTEM-1 | 5′-GTATCCGCTCATGAGACAATA-3′ | 7 |

| PreTEM-2 | 5′-TCTAAAGTATATATGAGTAAACTTGGT | 7 |

| SHV-F | 5′-ATGCGTTATWTTCGCCTGTGT-3′ | 4 |

| SHV-B | 5′-TTAGCGTTGCCAGTGCTCG-3′ | 4 |

| GES1A | 5′-ATGCGCTTCATTCACGCAC-3′ | 4 |

| GES1B | 5′-CTATTTGTCCGTGCTCAGG-3′ | 4 |

| PER-A | 5′-ATGAATGTCATTATAAAAGC-3′ | 4 |

| PER-D | 5′-AATTTGGGCTTAGGGCAGAA-3′ | 4 |

| GSP1 | 5′-AAGTACATCTTATGGCTGACT-3′ | This study |

| GSP2 | 5′-ATGAAACTGCAATCCTCGAAACTG-3′ | This study |

| GSP3 | 5′-TGGCTGAAGTCACACTGATAAAAG-3′ | This study |

Conjugation experiments were carried out by a filter mating technique with E. coli J53 Azr as the recipient, as described previously (13, 17). Transconjugants were selected on Trypticase soy agar plates containing sodium azide (100 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint-Quentin-Fallavier, France) for counterselection and ampicillin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml), tobramycin (8 μg/ml), or ceftazidime (2 μg/ml) for selection of plasmid-encoded determinants. Selected colonies were replica plated onto Trypticase soy agar plates with and without nalidixic acid (16 μg/ml). Transconjugation frequencies were determined by dividing the number of transconjugants by the number of donor cells.

Plasmid analysis and hybridization experiments.

Plasmid analyses of the clinical isolates, transconjugants, and reference strains were performed by the technique of Kieser (6), followed by agarose gel electrophoresis analysis (20). Then, reference qnr-positive plasmid pMG252, the transconjugant plasmid, and the plasmid of E. coli MG-1 were transferred onto a Hybond N+ nylon membrane by using a vacuum blotting system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Orsay, France) and were subsequently cross-linked with a UV Stratalinker cross-linker (Stratagene). Hybridizations were performed with an enhanced chemiluminescence nonradioactive labeling and detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), as described by the manufacturer. The probes consisted of the 661-bp fragment for qnr and a 627-bp fragment for blaVEB-1, and gene-specific primers were used (Table 1).

Susceptibility testing.

Disk diffusion susceptibility testing was performed as described previously (18; http://www.sfm.asso.fr). MICs were determined by an agar dilution technique, as reported previously (14).

PCR and sequencing.

Laboratory-designed primers (Table 1) were used for the detection of class A β-lactamase genes blaTEM, blaSHV, blaPER-1, blaVEB-1, and blaGES-1; and whole-cell DNA of E. coli Lo was used as the template. A search for additional chromosome-encoded quinolone resistance determinants was performed with primers gyrA6 and gyrA631R for subunit gyrA of the topoisomerase II gene and primers ParCF43 and ParCR981 for subunit parC of the topoisomerase IV gene (Table 1). The gyrA gene-specific primers flanked a 626-bp fragment (base pairs 6 to 631), whereas the parC gene-specific primers flanked an 849-bp fragment (base pairs 43 to 890) of the corresponding genes. For PCR mapping of the integrons that contained the blaVEB-1 and the qnr genes, 500 ng each of whole-cell DNA of E. coli Lo, E. coli MG-1, and E. coli J53/pMG252 was used in standard PCR experiments with a series of PCR primers used in combination, as follows: VEB-1B and aadB-F, 5′CS and aadB-B, OXA-10CASB and aadB-F, 3′CS and OXA-10CASF, VEB-1A and arr-2B, orfG-B and AAC1-F, IS26A and aadB-B, VEB-1A and CMLA-B, ORF513D5 and QnrB, Sul1A and QnrB, 3′CS and QnrA, QnrA and ORF513D3, and 5′CS and 3′CS (Table 1).

After PCR amplification, the DNA was purified with a Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). Both strands of the amplification products obtained were sequenced with an Applied Biosystems sequencer (ABI 377). The nucleotide and deduced protein sequences were analyzed with software available over the Internet at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The ClustalW program (www.infobiogen.fr) was used to align multiple protein sequences.

IEF and OMP analyses.

The β-lactamase extracts from cultures of E. coli Lo and the transconjugants were subjected to analytical isoelectric focusing (IEF), as described previously (18). The OMP profile of E. coli Lo was determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (17, 20) and was compared to the profiles of the E. coli reference strains expressing either OmpC or OmpF, as described previously (17).

Mapping of the qnr transcription start site.

Reverse transcription and rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) were performed with the 5′RACE system (version 2.0), according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Cergy-Pontoise, France) (3). Briefly, 5 μg of total RNA extracted from an ampicillin-containing culture of E. coli Lo with an RNeasy Maxi kit (Qiagen) was used to determine the transcription initiation site of the qnr gene. After a reverse transcription step with gene-specific primer GSP1 (Table 1) and reverse transcriptase, the cDNA was tailed with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase and was subsequently amplified with another gene-specific primer, GSP2 (Table 1) combined with an oligo(dT) adapter primer provided with the kit. This PCR product was used as a template for a nested PCR with another adapter primer and primer GSP3 (Table 1). The PCR product obtained was cloned into pCR-BluntII-Topo (Invitrogen), and the corresponding clones possessing the larger insert were sequenced. Analysis of the cloned sequence allowed determination of the transcription initiation site, defined as the first nucleotide following the sequence of the adapter primer.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the qnr-positive integrons of pQR-1 and pMG252 have been submitted to the GenBank nucleotide sequence database and have been assigned accession numbers AY655485 and AY655486, respectively.

RESULTS

Screening for the qnr gene and clinical cases.

The qnr gene was detected in 1 of 297 nalidixic-acid resistant E. coli strains (0.3%). This qnr-positive strain, E. coli Lo, was isolated from a 39-year-old man in December 2003. This human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient had been hospitalized in intensive care units of several Paris hospitals for pneumonia. One month after the case of pneumonia, the patient had a cholecystitis episode caused by an antibiotic-susceptible E. coli isolate that was treated by endoscopic sphincterotomy and with ciprofloxacin. Then, E. coli Lo was isolated from stool and urine samples and was considered a colonizing agent. Preliminary antibiotic susceptibility testing by disk diffusion revealed that E. coli Lo was resistant to most β-lactams, including cefotaxime, ceftazidime, and aztreonam. Synergies between extended-spectrum cephalosporins and clavulanate were detected, consistent with the presence of extended-spectrum class A β-lactamases. E. coli Lo was also resistant to chloramphenicol, nalidixic acid, rifampin, sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, trimethoprim, and a series of aminoglycosides and had reduced susceptibilities to fluoroquinolones (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

MICs of antibiotics for E. coli Lo, transconjugant E. coli J53/pQR1, and E. coli J53 Az

| Antibiotic(s) | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli Loa | E. coli J53/pQR1 | E. coli J53 | |

| Nalidixic acid | >256 | 32 | 4 |

| Ofloxacin | 4 | 1 | 0.12 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 | 0.25 | 0.01 |

| Moxifloxacin | 2 | 0.5 | 0.03 |

| Sparfloxacin | 4 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Rifampin | >256 | 32 | 8 |

| Chloramphenicol | 32 | 32 | 4 |

| Gentamicin | 16 | 8 | 0.12 |

| Tobramycin | 128 | 64 | 0.12 |

| Streptomycin | >256 | >256 | 2 |

| Amikacin | 16 | 8 | 0.25 |

| Sulfamethoxazole | >512 | >512 | 0.12 |

| Trimethoprim | >512 | >512 | 0.12 |

| Tetracycline | >64 | 1 | 1 |

| Amoxicillin | >512 | >512 | 4 |

| Amoxicillin-CLAb | 128 | 32 | 4 |

| Ticarcillin | >512 | >512 | 4 |

| Ticarcillin-CLA | 256 | 4 | 4 |

| Piperacillin | 128 | 16 | 2 |

| Piperacillin-TZBc | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Cephalothin | 128 | 128 | 8 |

| Cefoxitin | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Cefotaxime | 4 | 4 | 0.06 |

| Ceftazidime | 256 | 256 | 0.06 |

| Ceftazidime + CLA | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.06 |

| Aztreonam | 32 | 32 | 0.06 |

| Cefepime | 1 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Imipenem | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.06 |

E. coli Lo and E. coli J53/pQR1 contained the qnr-positive plasmid that also harbored the blaVEB-1 gene.

CLA, clavulanic acid at 2 μg/ml.

TZB, tazobactam at 4 μg/ml.

Transfer of quinolone resistance and plasmid characterization.

Quinolone resistance was transferred by conjugation after selection with a series of antibiotic resistance markers but not with quinolones to avoid the selection of spontaneous gyrase mutations in the recipient E. coli strain. The conjugation frequencies (the number of transconjugants divided by the number of donor cells) ranged from 1 × 10−5 to 2 × 10−6. The frequencies of coresistance (the percentage of selected colonies that were resistant to the antibiotic used as the selector and to nalidixic acid) were 40 and 70% for amoxicillin and tobramycin, respectively, whereas the qnr gene was identified in 24 of 25 nalidixic acid-susceptible transconjugants tested. In most of the transconjugants, the antibiotic resistance markers cotransferred were those for resistance to ampicillin, ceftazidime, chloramphenicol, rifampin, sulfamethoxazole, tobramycin, and trimethoprim but not tetracycline.

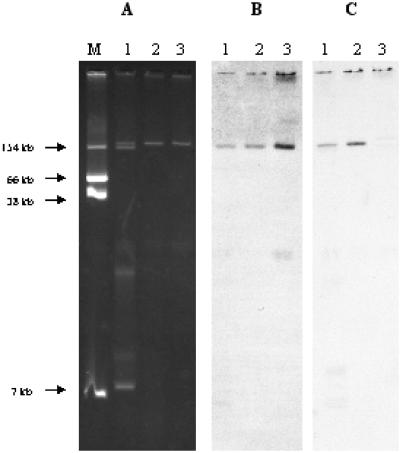

E. coli Lo contained three plasmids with estimated sizes of ca. 180, 150, and 10 kb, respectively, whereas transconjugants contained a single ca. 180-kb plasmid that hybridized with the qnr-specific probe (Fig. 1). The qnr-positive plasmid was designated pQR1. Plasmid pQR1 also hybridized with the veb-1-specific probe (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Plasmid DNAs from clinical isolate E. coli Lo and E. coli transconjugant strains (A) and Southern hybridization of plasmid DNAs with the qnr-specific probe (B) and the blaVEB-1-specific probe (C). Lanes: 1, E. coli Lo; 2, E. coli J53/pQR1; 3, E. coli J53/pMG252 (used as a positive control); M, E. coli NCTC50192 (used as a negative control and a reference for plasmid sizes).

Antibiotic susceptibility testing.

Plasmid pQR1 conferred increased quinolone MICs (from 8- to 100-fold) for the transconjugants (Table 2). The patterns of susceptibility to β-lactams of E. coli Lo and the transconjugants corresponded to the expression of a clavulanic acid-inhibited expanded-spectrum β-lactamase (Table 2). In addition, plasmid pQR1 conferred resistance or decreased susceptibility to amikacin, gentamicin, streptomycin, tobramycin, chloramphenicol, rifampin, sulfamethoxazole, and trimethoprim (Table 2).

Characterization of quinolone resistance determinants.

The clinical strains and transconjugant E. coli J53/pQR1 harbored the same qnr gene that was originally identified from a K. pneumoniae isolate in the United States (10, 21). In addition, a single Ser83Leu substitution was identified in the quinolone resistance-determining motif of subunit A of topoisomerase II, whereas a wild-type topoisomerase IV gene was found. The OMP profile of E. coli Lo was not modified compared to that of an E. coli reference strain (data not shown).

Characterization of β-lactamases.

IEF analysis of culture extracts of E. coli Lo and E. coli J53/pQR1 gave three β-lactamase bands with pIs of 7.4, 6.3, and 5.4, respectively (data not shown). The genes of these β-lactamases were identified as blaVEB-1, blaOXA-10, and blaTEM-1, according to the sequencing results.

PCR mapping and sequencing of the integrons.

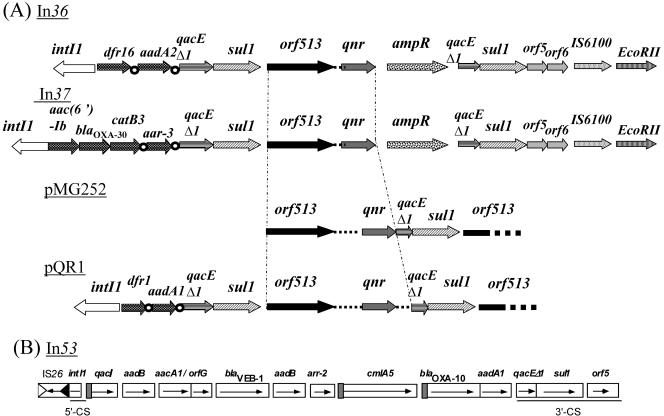

The qnr gene was located on a sul1-type class 1 integron (Fig. 2). It was bracketed by a duplication of the 3′ conserved sequence (3′-CS) region of the class 1 integron and was not associated with a 59-bp element. This sul1-type integron did not contain an ampR sequence coding for a LysR-type regulatory element. Orf513 was found immediately upstream of the qnr gene, and a common structure of a class 1 integron that contained the dfr1 and aadA1 genes was identified further upstream (Fig. 2). The dfr1 and aadA1 genes explained resistance to trimethoprim and to streptomycin and spectinomycin, respectively. A duplication of part of orf513 was identified downstream of the second copy of the 3′-CS element (qacEΔ1-sul1) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of sul1-type integrons that contain a qnr gene (A) and the blaVEB-1-positive class 1 integron In53 (B). Shaded boxes in In53 indicate gene cassettes possessing their own promoter sequences.

This sul1-type class 1 integron was different from the In36 and In37 integrons identified in E. coli isolates from Shanghai, since (i) the gene cassettes upstream of orf513 were different, (ii) the downstream region of orf513 in pQR1 did not contain an ampR-like sequence, and (iii) the DNA sequence between the right-hand boundary of CR1 and the qnr gene was 32 bp longer in the sul1-type integron of pQR1 than in In36 and In37 (Fig. 2 and 3). The sul1-type integron of pQR1 was also different from that of pMG252, since (i) in pQR1 the gene cassettes identified upstream of orf513 were absent from pMG252, and (ii) the downstream region of the qnr gene in the sul1-type integron of pQR1 contained an additional 265-bp sequence compared to the sequence of pMG252. This additional 265-bp fragment contained 25 bp belonging to the qacEΔ1 gene in pQR1 (Fig. 2).

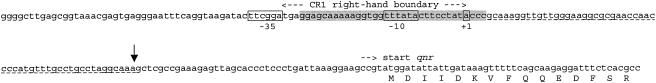

FIG. 3.

Nucleotide sequence of the promoter structure for qnr expression, as determined by the 5′ RACE experiment. The deduced amino acid sequence of Qnr is designated in single-letter code below the nucleotide sequence. The transcription orientation of the qnr gene is indicated by a horizontal arrow. The right-hand boundary of CR1 is shaded in gray. The −35 and −10 promoter sequences are boxed, as is the +1 transcription initiation site; all of these are part of the CR1 element. The vertical arrow indicates the position of the extremity of the CR1 right-hand boundary of In36 (24), in which the 67-bp sequence with a dotted underlined is lacking.

The structure of the class 1 integron that contained the veb-1 cassette was also determined (Fig. 2). It was identical to that reported in In53 (4, 13). The veb-1 cassette in pQR1 was not part of a Tn2000 composite transposon, since the right copy of IS26 of Tn2000 was missing (Fig. 2) (13). A series of PCR-based experiments failed to identify the blaVEB-1-positive integron in the immediate vicinity of the qnr-positive sul1-type integron.

Mapping of qnr transcription site.

By using 5′ RACE PCR experiments, the site of initiation of transcription of the qnr gene was mapped in E. coli Lo to be 104 bp upstream of the start codon of this gene (Fig. 3). Upstream of this transcriptional start site, a −35 promoter sequence (TTCGGA) was found, and this was separated by 18 bp from a −10 promoter sequence (TTTATA) (Fig. 3). These promoter sequences overlapped the CR1 element.

DISCUSSION

This study reports on the first detection of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in Europe. Twenty-five qnr-positive K. pneumoniae and E. coli isolates have been identified from U.S. and Chinese isolates among a total of 967 gram-negative isolates of worldwide origin tested (5, 19, 21-24). The variability of the criteria for the strains tested makes the precise determination of the prevalence of this plasmid-borne mechanism of resistance impossible. In the present study, the Qnr determinant was very rare, since only a single E. coli isolate with this determinant was identified. The prevalence of this gene in nalidixic-acid resistant E. coli isolates (0.3%) seems to be much lower than that reported in ciprofloxacin-resistant E. coli isolates from Shanghai (7.7%) (24).

However, one cannot rule out the possibility that the failure of detection of qnr-positive strains may have resulted from weak expression of the Qnr determinant. Indeed, we, like others (5, 21-24), have found that several transconjugants could be nalidixic acid susceptible and truly qnr positive, which raises the question of its expression. In addition, nucleotide changes in the extremities of the qnr-like genes corresponding to the location for hybridization of the PCR primers designed for the study may have limited further detection of qnr-positive strains.

As reported previously (9, 10, 21, 23), the Qnr determinant alone did not provide resistance to fluoroquinolone, according to the NCCLS guidelines. In E. coli Lo, it was associated with an Ser83Leu substitution in the chromosomally encoded subunit A of topoisomerase II. Combined mechanisms of resistance to quinolones in E. coli Lo corresponded to what had been predicted in in vitro studies (9), and explained the lower levels of quinolone resistance for the transconjugants than for the clinical strain.

The sequence of the qnr gene was identical to that first reported for a K. pneumoniae strain isolated in Alabama in 1994 (21). The variability of the qnr-like genes identified worldwide seems to be very much limited, with only a single nucleotide change (without an amino acid change) identified among the qnr-like genes from American and Chinese isolates that have been sequenced (19, 21-24), thus suggesting a common source. The qnr gene G+C content of 60% argues for a nonenterobacterial origin.

Structure analysis of the qnr-positive integrons indicated sequence variability, with the integron of pQR1 being more related to that of pMG252 of K. pneumoniae UAB1 from Alabama (21) than to those of E. coli isolates from Shanghai (24). Whereas the qnr gene itself remains quite invariable, it is likely that different recombination events that resulted in the acquisition of the qnr gene in integrons had occurred.

The expression of qnr depended on the −35 and −10 promoter sequences located in the CR1 element. This CR1 element and the Orf513 recombinase have been associated with a series of antibiotic resistance genes, such as those coding for CTX-M-type β-lactamase; plasmid-mediated cephalosporinase; and sulfonamide, chloramphenicol, macrolide, and tetracycline resistance determinants (15). Thus, these structures may be involved not only in mobilization of the antibiotic resistance genes located downstream, as suggested previously (15), but also in their expression.

The qnr determinant was associated with the blaVEB-1 gene, which may further explain a tight association between resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins and resistance to quinolones (16).

Finally, we showed that a single conjugative plasmid may carry two types of class 1 integrons that may confer resistance to quinolones, most β-lactams except carbapenems, most aminoglycosides, sulfonamides, rifampin, trimethoprim, and chloramphenicol. This is the outmost evolution of coresistance to broad-spectrum antibiotics located on a single genetic vehicle.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the Ministère de l'Education Nationale et de la Recherche (UPRES-EA3539), Université Paris XI, Paris, France, and by the European Community (6th PCRD, LSHM-CT-2003-503-335).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambler, R. P., A. F. W. Coulson, J.-M. Frère, J. M. Ghuysen, B. Joris, M. Forsman, R. C. Lévesque, G. Tiraby, and S. G. Waley. 1991. A standard numbering scheme for the class A β-lactamases. Biochem. J. 276:269-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danel, F., H. C. Hall, D. Gür, and D. Livermore. 1995. OXA-14, another extended-spectrum variant of OXA-10 (PSE-2) β-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1881-1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frohman, M. A. 1993. Rapid amplification of complementary DNA ends for generation of full-length complementary DNA: thermal RACE. Methods Enzymol. 218:340-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Girlich, D., L. Poirel, A. Leelaporn, A. Karim, C. Tribuddharat, M. Fennewald, and P. Nordmann. 2001. Molecular epidemiology of the integron-located VEB-1 extended-spectrum β-lactamase in nosocomial enterobacterial isolates in Bangkok, Thailand. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:175-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacoby, G. A., N. Chow, and K. B. Waites. 2003. Prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:559-562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kieser, T. 1984. Factors affecting the isolation of CCC DNA from Streptomyces lividans and Escherichia coli. Plasmid 12:19-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindgren, P. K., A. Karlsson, and D. Hughes. 2003. Mutation rate and evolution of fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli isolates from patients with urinary tract infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3222-3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDonald, L. C., F.-J. Chen, H.-J. Lo, H.-C. Yin, P.-L. Lu, C.-H. Huang, P. Chen, T.-L. Lauderdale, and M. Ho. 2001. Emergence of reduced susceptibility and resistance to fluoroquinolones in Escherichia coli in Taiwan and contributions of distinct selective pressures. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3084-3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martínez-Martínez, L., A. Pascual, I. García, J. Tran, and G. A. Jacoby. 2003. Interaction of plasmid and host quinolone resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:1037-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martínez-Martínez, L., A. Pascual, and G. A. Jacoby. 1998. Quinolone resistance from a transferable plasmid. Lancet 351:797-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montero, C., G. Mateu, R. Rodriguez, and H. Takiff. 2001. Intrinsic resistance of Mycobacterium smegmatis to fluoroquinolones may be influenced by new pentapeptide protein MfpA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3387-3392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naas, T., F. Benaoudia, F. Massuard, and P. Nordmann. 2000. Integron-located VEB-1 extended-spectrum β-lactamase gene in a Proteus mirabilis clinical isolate from Vietnam. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:703-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naas, T., T. Mikami, T. Imai, L. Poirel, and P. Nordmann. 2001. Characterization of In53, a class 1 plasmid- and composite transposon-located integron of Escherichia coli which carries an unusual array of gene cassettes. J. Bacteriol. 183:235-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, p. 1. Approved standard M7-A6. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 15.Partridge, S. R., and R. M. Hall. 2003. In34, a complex In5 family class 1 integron containing orf513 and dfrA10. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:342-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paterson, D. L., L. Mulazimoglu, J. M. Casellas, W. C. Ko, H. Goossens, A. Von Gottberg, S. Mohapatra, G. M. Trenholme, K. P. Klugman, J. G. McCormack, and V. L. Yu. 2000. Epidemiology of ciprofloxacin resistance and its relationship to extended-spectrum β-lactamase production in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates causing bacteremia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:473-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poirel, L., C. Héritier, C. Spicq, and P. Nordmann. 2004. In vivo acquisition of high-level resistance to imipenem in Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3831-3833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poirel, L., T. Naas, M. Guibert, E. B. Chaibi, R. Labia, and P. Nordmann. 1999. Molecular and biochemical characterization of VEB-1, a novel class A extended-spectrum β-lactamase encoded by an Escherichia coli integron gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:573-581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodríguez-Martínez, J. M., A. Pascual, I. García, and L. Martínez-Martínez. 2003. Detection of the plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinant qnr among clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing AmpC-type β-lactamase. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:703-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 21.Tran, J. H., and G. A. Jacoby. 2002. Mechanism of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:5638-5642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, M., D. F. Sahm, G. A. Jacoby, and D. C. Hooper. 2004. Emerging plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance associated with the qnr gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1295-1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, M., D. F. Sahm, G. A. Jacoby, Y. Zhang, and D. C. Hooper. 2004. Activities of newer quinolones against Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae containing the plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinant Qnr. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1400-1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang, M., J. H. Tran, G. A. Jacoby, Y. Zhang, F. Wang, and D. C. Hooper. 2003. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli from Shanghai, China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2242-2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]