Significance

Human skin consists of distinct layers and is designed to prevent water loss and to keep harmful materials out, which makes transcutaneous drug delivery challenging. A model for drug diffusion within skin is introduced that as the only input requires experimental concentration profiles measured at three distinct penetration times. For the specific example of the antiinflammatory drug dexamethasone, the modeling shows that both free-energy and diffusivity profiles are highly inhomogeneous, which reveals the basic mechanism of epidermal barrier function: slow diffusion in the outer stratum corneum hinders fast penetration into the skin, whereas a pronounced free-energy step from the epidermis to the dermis underneath reduces long-time permeation. Targeted drug delivery strategies through skin must reflect these properties.

Keywords: diffusion, data-based modeling, biological barriers, skin, Smoluchowski equation

Abstract

Based on experimental concentration depth profiles of the antiinflammatory drug dexamethasone in human skin, we model the time-dependent drug penetration by the 1D general diffusion equation that accounts for spatial variations in the diffusivity and free energy. For this, we numerically invert the diffusion equation and thereby obtain the diffusivity and the free-energy profiles of the drug as a function of skin depth without further model assumptions. As the only input, drug concentration profiles derived from X-ray microscopy at three consecutive times are used. For dexamethasone, skin barrier function is shown to rely on the combination of a substantially reduced drug diffusivity in the stratum corneum (the outermost epidermal layer), dominant at short times, and a pronounced free-energy barrier at the transition from the epidermis to the dermis underneath, which determines the drug distribution in the long-time limit. Our modeling approach, which is generally applicable to all kinds of barriers and diffusors, allows us to disentangle diffusivity from free-energetic effects. Thereby we can predict short-time drug penetration, where experimental measurements are not feasible, as well as long-time permeation, where ex vivo samples deteriorate, and thus span the entire timescales of biological barrier functioning.

Multicellular organisms exhibit numerous structurally distinct protective barriers, such as the blood–brain barrier; intestinal, mouth, and respiratory mucosa; and the skin, the largest human organ. These barriers are generally designed to keep foreign material out and in some cases to allow the highly regulated transfer of certain desired molecules; consequently, they present a severe challenge for drug delivery (1–3). The in-depth understanding of barrier function is not only required for controlled drug delivery, but also of central interest in medicine, drug development, and biology.

Human skin can be broadly divided into two layers (Fig. 1A): the epidermis with a thickness of about 100 m, which prevents water loss and the entrance of harmful microorganisms or irritants, and the dermis, which is typically 2 mm thick, contains blood vessels, and protects the body from mechanical stress (4). The epidermis is further divided into the stratum corneum (SC), the 10- to 20-m thick outermost layer consisting of dried-out dead skin cells, the corneocytes, and the viable epidermis (VE). In the stratum granulosum (SG), which is part of the VE, skin cells (keratinocytes) are gradually flattened and transformed into corneocytes when migrating toward the SC.

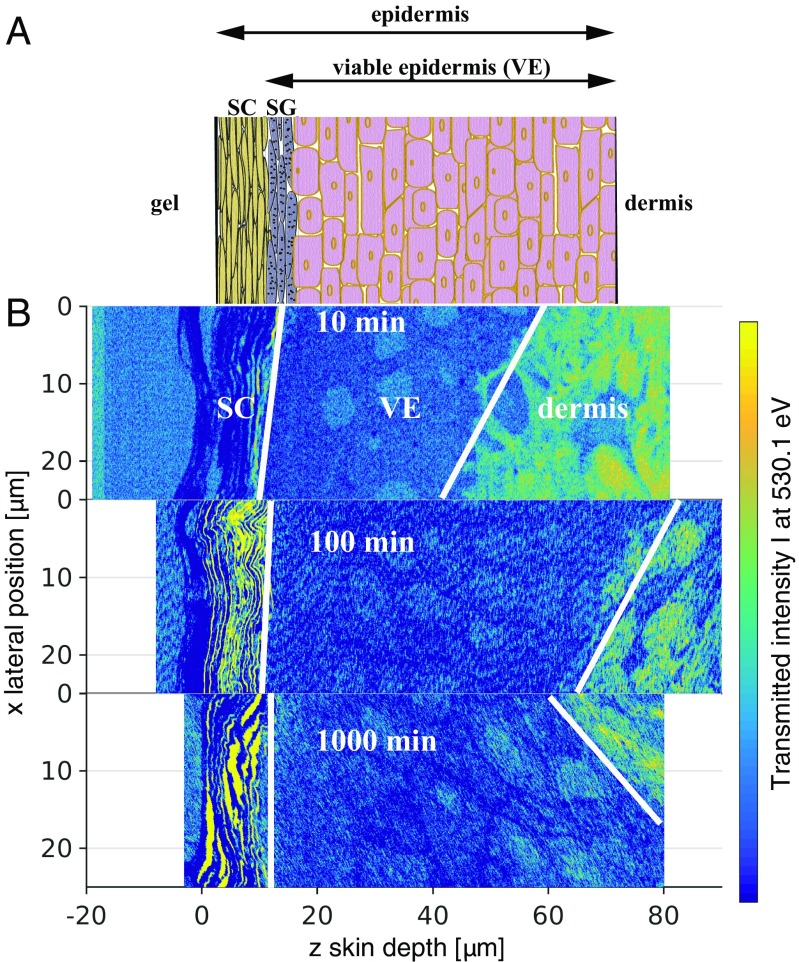

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic of epidermal skin structure. (B) Normalized 2D-transmission intensity profiles from X-ray scanning microscopy at photon energy after 10 min, 100 min, and 1,000 min penetration time. The profiles allow us to distinguish different skin layers, schematically indicated by white dividing lines, and demonstrate the skin sample variation. Whereas the SC has a rather uniform thickness, the VE thickness varies considerably between the three samples.

The SC is structurally similar to a brick wall (5): The bricks are the corneocytes, whereas the mortar is the intercellular matrix, which is composed of stacked lipid bilayers. Several models for the permeation of drugs through skin exist, which incorporate the skin structure on different levels of complexity. In the simplest models the stratified skin structure is reflected by 1D layers with different diffusivities and partition coefficients (6–10), and in more detailed models the 3D SC structure is accounted for (11, 12). In all models a certain skin structure and various transport parameters are assumed, which a posteriori are adjusted, such as to reproduce experimental permeabilities or concentration-depth profiles inferred from tape-stripping studies (11, 12). For a detailed overview of skin-diffusion models and a historical outline see refs. 13 and 14.

We describe here a data-based modeling approach, i.e., which does not make any model assumptions and as the only input requires drug concentration-depth profiles in the skin at three consecutive times. Our approach, which we test for the lipophilic antiinflammatory glucocorticoid dexamethasone (DXM) in ex vivo human skin, is very general and can be used for all kinds of permeation barriers. This drug is chosen because soft X-ray absorption spectromicroscopy allows us to generate 2D absolute concentration profiles of unlabeled DXM in thin skin slabs with a resolution below 100 nm (15, 16).

We start with the general 1D diffusion equation, which describes the evolution of a 1D concentration profile in space and time and depends on the position-dependent free-energy profile and the diffusivity profile ,

| [1] |

where is the inverse thermal energy. The free-energy profile reflects the local affinity and determines how the substance, in our specific case DXM, partitions in equilibrium, namely . The diffusivity profile is a local measure of the velocity at which the substance diffuses in the absence of external forces. The diffusion equation not only describes passive and active particle transport in structured media, it has in the past also been used for modeling marketing strategies (17), decision making (18), and epigenetic phenotype fluctuations (19). The importance of a spatially varying diffusivity profile has been recognized for the relative diffusion of two particles (20), transmembrane transport (21), particle diffusion at interfaces (22, 23), protein folding (24–27), and multidimensional diffusion (28). The 1D diffusion equation can be solved analytically only in simple limits; for general and profiles the solution must be numerically calculated.

The inverse problem, i.e., extracting and from simulation or experimental data, is much more demanding and has recently attracted ample theoretical attention. With one notable exception (29), most inverse approaches need single-particle stochastic trajectories and are not suitable to extract information from concentration profiles (20–22, 30–32). For the typical experimental scenario, where a few concentration profiles at different times are available, we here present a robust method that yields the and profiles with minimal numerical effort and for general open boundary conditions (Materials and Methods). We demonstrate our method using experimental 1D concentration-depth profiles of DXM, a medium-size drug molecule that in water is only poorly soluble (33). Starting the drug penetration by placing a DXM formulation in a hydroxethyl cellulose (HEC) gel on top of excised human skin at time 0, 2D concentration profiles of DXM in the epidermal skin layer are obtained after penetration times of 10 min, 100 min, and 1,000 min, using soft X-ray absorption spectromicroscopy (15, 16) (Materials and Methods).

To determine both the free-energy profile and the diffusivity profile in the epidermal skin layer as well as the diffusive DXM properties in the drug-containing HEC gel and in the dermis, we need three experimental concentration profiles recorded at different times as input. We demonstrate that both the diffusivity profile , which dominates drug penetration for short times, and the free-energy profile , which dominates long-time drug concentration profiles, are needed to describe drug penetration quantitatively.

Our analysis reveals that skin barrier function results from an intricate interplay of different skin layer properties: Whereas the entrance of lipophilic DXM into the SC is free-energetically favored, the drug diffusivity in the SC is about 1,000 times lower than in the VE and thus slows down the passage of DXM through the SC. In addition, a pronounced free-energy barrier from the epidermis to the dermis prevents DXM from penetrating into the lower dermal layers. In essence, the epidermis has a high affinity for the lipophilic drug DXM, which together with the low diffusivity in the SC efficiently prevents DXM penetration into the dermis.

Results and Discussion

Experimental Concentration Profiles.

Fig. 1B shows 2D absorption profiles recorded at photon energy eV for penetration times of 10 min, 100 min, and 1,000 min. This photon energy selectively excites DXM (15). The skin-depth coordinate is shifted such that the outer skin surface is aligned to . The color codes the transmitted intensity, with blue indicating low and yellow high transmission, and allows insights into the skin structure. Note that the three profiles originate from different skin samples from the same donor, because the analysis of the identical skin sample for different penetration times is not possible (16). Accordingly, these three samples have been chosen for maximal similarity of the SC and VE thicknesses.

The region below m is the Epon resin used for skin embedding. For all three samples, the layered structure from m to m is the SC, whereas the VE extends from a depth of about m to a variable depth ranging from m to m. Within the VE oval-shaped keratinocyte nuclei are discerned, which move gradually toward the SC where they differentiate and flatten into corneocytes. The dermis, separated from the VE by the basal layer and the basal membrane, is clearly distinguished from the VE by the different transmission intensity. Note that the variation of the VE thickness across different samples is an inherent property of skin and must be kept in mind in the analysis. From the ratio of the 2D transmission profiles at photon energies of eV and eV the 2D concentration profiles of DXM are determined (15, 16) (see Materials and Methods, DXM Concentration Profiles from X-Ray Microscopy, and Figs. S1 and S2 for details).

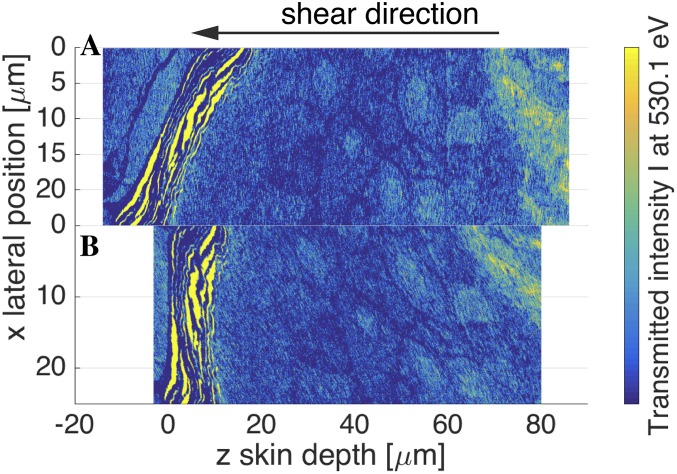

Fig. S1.

(A) Two-dimensional transmission intensity profile at photon energy eV after 1,000-min penetration time taken directly from X-ray microscopy. The SC is not aligned perpendicularly to the z axis. (B) Aligned 2D intensity profile after shearing along the z axis.

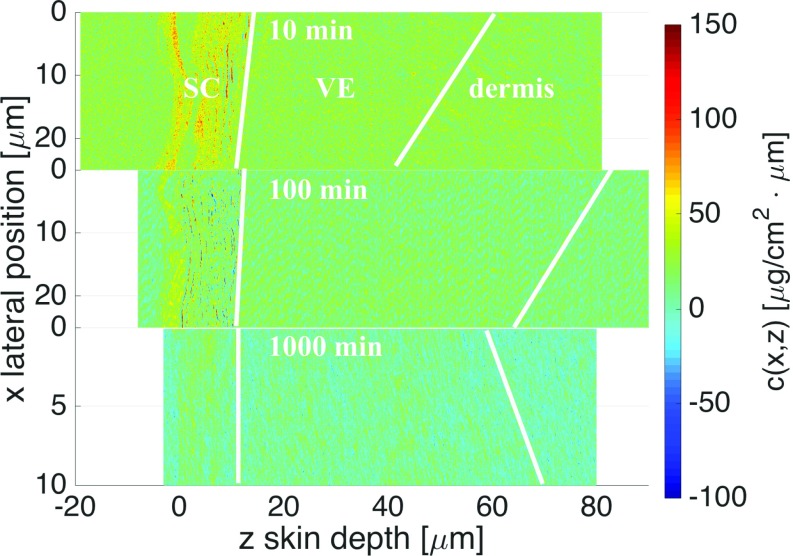

Fig. S2.

Experimental 2D concentration profiles obtained after 10-min, 100-min, and 1,000-min penetration times. The 1,000-min profile has been sheared to achieve perpendicular orientation of the SC with respect to the z axis. In the 10-min and 100-min profiles the inhomogeneous distribution of DXM within the SC is well observed.

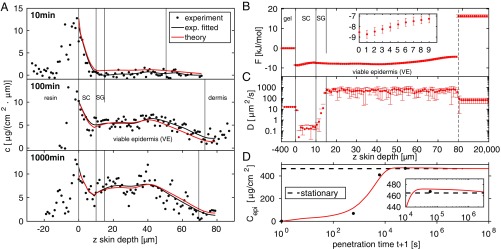

Our aim is not to describe DXM diffusion at the cellular level, for which 3D concentration profiles at different penetration times of the same sample would be needed; our goal rather is to model the 1D diffusion of DXM from the HEC gel on the skin surface through the epidermis into the deeper skin layers. For this, we laterally average the experimental 2D concentration profiles; the resulting 1D concentration data are shown in Fig. 2A (black solid circles). We base our modeling on cubic smoothing spline fits (black lines) in the range m, disregarding residual DXM in the Epon resin for m as well as the range m where only a single concentration profile is available. It is seen that already after 10 min penetration DXM has entered the SC. After 100 min penetration DXM is found in the VE, whereas the concentration in the SC has not changed much. The difference between the 100-min and the 1,000-min profiles is seen to be rather small.

Fig. 2.

(A) One-dimensional experimental DXM concentration profiles at three different penetration times (black solid circles) and cubic smoothing splines (black lines) are compared with theoretical predictions based on the diffusion equation (red lines). Vertical dividing lines indicate skin layers and are based on the 2D transmission intensity profiles in Fig. 1B. (B and C) Free-energy profile (B) and diffusivity profile (C) derived from the experimental concentration profiles. is low in the entire epidermis (SC and VE) compared to the HEC gel and to the dermis and exhibits a small but significant gradual increase in the SC (B, Inset), and the epidermis thus exhibits lipophilic affinity. is low in the SC and increases by a factor of 1,000 in the VE, where it is close to the free-solution value. The low diffusivity in the SG in the depth range 10 m m could indicate the presence of tight junctions. In the gel and beyond m (indicated by a vertical dashed line) the and profiles are approximated as constant. (D) Integrated amount of DXM in the epidermis from experiments (black solid circles) and theory (red line), showing a maximum at penetration time min (Inset) before it relaxes to the predicted stationary value indicated by a horizontal dashed line.

Extracting Free-Energy and Diffusivity Profiles.

Feeding the three experimental DXM concentration profiles in the depth range m after 10 min, 100 min, and 1,000 min penetration time into our inverse solver for the diffusion equation, we derive the best estimates for the and profiles shown in Fig. 2 B and C; in the gel and in the dermis, due to the absence of experimental data, we approximate and to be constant. The error bars reflect the SD of the estimates that pass the error threshold g/(cmm) (see Materials and Methods for more details).

The free energy in Fig. 2B, approximated to be constant in the gel and set to , exhibits a jump down by kJ/mol at the boundary between gel and SC. This is in line with the lipophilic character of DXM, which prefers to be in the lipid-rich SC compared with the HEC gel formulation. In the SC, the free energy increases rather smoothly by kJ/mol over a range of m (Fig. 2B, Inset), reflecting a significant structural change across the SC that sustains the steep water chemical potential gradient across the SC (34). In the depth range m m, which corresponds to the VE, the free energy is rather constant. In the range m m the free energy slightly increases again, which reflects the decreasing DXM concentration in the experimental profiles in Fig. 2A for 100 min and 1,000 min. Comparison with the transmission intensity profiles in Fig. 1B reveals that this free-energy increase is caused by the transition from the epidermis to the dermis, which due to skin sample variations is smeared out over a broad depth range of m m. The free-energy jump of kJ/mol at m reflects a pronounced barrier for DXM penetration into the dermis related to the different DXM affinity to the dermis compared with the VE. Due to data scattering this value constitutes a lower bound, as is explained in Estimate of Free-Energy Barrier Height Between Epidermis and Dermis and Fig. S3. In fact, the free-energy difference between the HEC gel and the dermis, kJ/mol = 6.4 , is quite close to the free-energy difference derived from the maximal DXM solubility in water, mg/L at 25°C (35), and the DXM solubility in the HEC gel g/L, via the partition coefficient according to . The free-energy profile thus identifies the dermis as essentially water-like, whereas the epidermis is a sink with high lipophilic affinity, in line with previous conclusions (36).

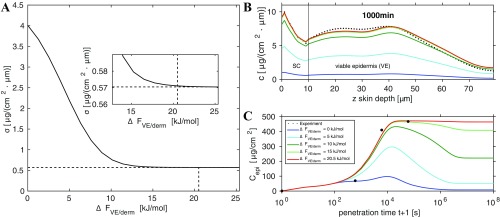

Fig. S3.

Effect of varying free-energy barrier height between VE and dermis. (A) Residual error as a function of . The minimal error g/(cmm) is indicated by a dashed horizontal line, which is reached for a free-energy barrier of kJ/mol, which is indicated by a vertical dashed line. (B) The 1,000-min concentration profiles calculated for different barrier heights . (C) Integrated amount of DXM in epidermis for different barrier heights .

The constant diffusivity in the HEC gel turns out to be m and drops in the SC by a factor of roughly 80 to m (Fig. 2C). The diffusivity maintains such a low value up to a depth of m, where it abruptly increases. For m exhibits a rather constant value of m, which is significantly larger than the value in the HEC gel and somewhat smaller than the estimated diffusion constant of dexamethasone in pure water, m (33). We tentatively associate the layer m m, where the diffusivity is as low as in the SC but structurally is distinct from the SC and belongs to the VE, with the SG. Note that the SG, which is known to be located right below the SC, is not visible in the transmission profiles in Fig. 1. The SG barrier function has been shown to be due to tight junctions (37–40), in line with the low local diffusivity in this region displayed in Fig. 2C.

Summarizing, four distinct features are revealed by our analysis: (i) a low diffusivity in the SC, (ii) a low diffusivity in a thin layer just below the SC that we associate with the SG, (iii) a sudden drop in free energy from the gel to the SC and a slight but significant free-energy increase in the SC, and (iv) a pronounced free energy barrier from the epidermis to the dermis. We stress that these features in the free-energy and diffusivity profiles are not put in by way of our analysis method, but rather directly follow from the experimental concentration profiles. We note in passing that the steep increase of the diffusivity at the boundary from the putative SG (with m) to the VE (with m) is nothing one could directly identify from the experimental concentration profiles shown in Fig. 2A.

Predicting Concentration Profiles.

In Fig. 2A we demonstrate that the numerical solutions of the diffusion equation (red lines), based on the free-energy and diffusivity profiles and in Fig. 2 B and C, reproduce the experimental concentration profiles very well (black lines). Small deviations are observed for the drug-concentration profile after 10 min penetration time, and the agreement is almost perfect for the 100-min and 1,000-min profiles. This not only means that our method for extracting and from concentration profiles works; we also conclude that the diffusion equation Eq. 1 describes the concentration time evolution in skin very well.

We define the time-dependent integral DXM amount that has penetrated into the epidermis over the distance range m as

| [2] |

In Fig. 2D we compare the experimental data for (solid black circles), which are directly obtained by integrating over the experimental concentration profiles in Fig. 2A, with the theoretical prediction based on the diffusion equation and the determined and profiles (red line). Note the logarithmic timescale that extends from s to s 3 y. According to the experimental protocol, at time the entire amount of DXM, corresponding to a surface concentration of g/cm2, is located in the gel and thus is zero. With increasing time, the theoretically predicted increases gradually and reaches a maximum of g/cm2 at s min, at which time only g/cm2 DXM has penetrated into the dermis [Calculating the DXM Penetration Amount from Estimated F(z) and D(z) Profiles]. In the long-time limit, which is reached above s115 d, as seen in Fig. 2D, Inset, theory predicts the equilibrium value g/cm2, denoted by a horizontal dashed line. In this hypothetical limit, longer than the exfoliation time of skin, which is 30–40 d, theory predicts that g/cm2 DXM has penetrated into the dermis, whereas g/cm2 DXM still resides in the gel [see Calculating the DXM Penetration Amount from Estimated F(z) and D(z) Profiles for the full calculation]. Note that in vivo, dermal blood perfusion is crucial and could be easily taken into account in a generalized diffusion model by an additional reaction term.

The theoretically predicted curve for in Fig. 2D agrees well with the experimental data, which is not surprising in light of the good agreement of the concentration profiles in Fig. 2A. This indicates that also the short- and long-time DXM penetration amounts, which are difficult to extract experimentally, are straightforwardly obtained from our model.

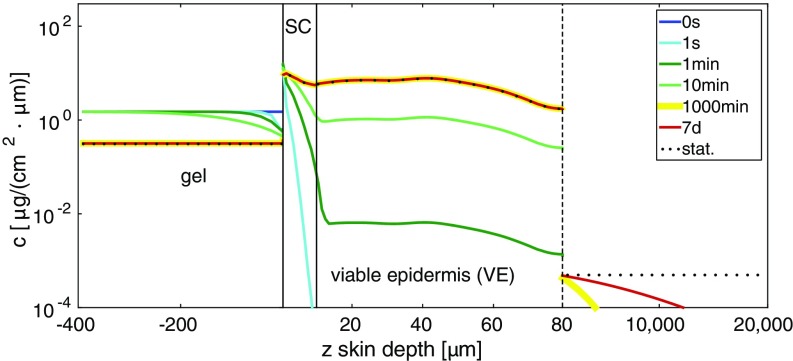

In Fig. 3 we show calculated DXM concentration depth profiles for a wide range of times. We here also plot the predicted concentration profiles in the gel and below the epidermis, for which no experimental data are available. We see that for short penetration times the concentration profile in the HEC gel is inhomogeneous, so the simplifying assumption of a constant concentration in the gel becomes invalid. Interestingly, already at s DXM enters the SC. The 1,000-min profile is indistinguishable from the stationary profile in the HEC gel and the epidermis, whereas below the epidermis, extending from m to cm, even after 7 d the stationary (flat) concentration profile has not yet been reached (note the inhomogeneous depth scale and the logarithmic concentration scale). Not surprisingly, molecular diffusion over a macroscopic length scale of 2 cm takes a long time.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of theoretical DXM concentration profiles for a wide range of different penetration times. At time 0 the drug is entirely in the gel. Already at t = 1 s DXM penetrates into the SC. At intermediate times t = 1 min and t = 10 min the VE is gradually filled, whereas at longer times t = 1,000 min and t = 7 d the profile below the epidermis approaches the stationary profile (indicated by a dotted curve).

Checking Model Validity.

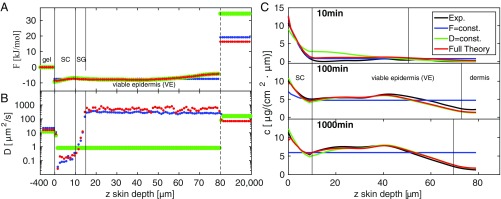

We check the robustness of our diffusion model by comparison with two simplified models. In the constant-F model we restrict the free energy in the epidermis to be constant (with the diffusivity still being a variable function), whereas in the constant-D model we restrict the diffusivity in the epidermis to be constant (with the free energy being a variable function). This means that the number of adjustable model parameters drops from 162 in the full model down to 83; otherwise we use the same methods for finding inverse solutions of the diffusion equation as before (Materials and Methods).

The free-energy profiles of the constant-F (blue) and the constant-D (green) models in Fig. 4A are rather similar and do not differ much from the full model result (red); in particular, the free-energy jumps from the HEC gel to the SC and from the VE to the dermis come out roughly the same. The diffusivity profile of the constant-F model in Fig. 4B is again similar to the full model, whereas the constant-D model obviously misses the diffusivity jump from the SC to the VE region.

Fig. 4.

(A–C) Comparison of the restricted constant-F (blue lines) and the constant-D (green lines) models to the full model (red lines) and experimental concentration profiles (black lines) in terms of the (A) free-energy, (B) diffusivity, and (C) concentration profiles. The constant-F model fails to predict the experimental long-time concentration profiles for penetration times 100 min and 1,000 min, and the constant-D model fails to predict the short-time concentration profile 10 min.

When we look at the predicted DXM concentration profiles in Fig. 4C, we clearly see the shortcomings of the restricted models: The constant-F model (blue lines) correctly predicts the short-time behavior including the 10-min profile, but fails severely for the long penetration time of 1,000 min, which is close to the stationary equilibrium limit. In contrast, the constant-D model (green line) produces a concentration profile for 1,000 min that is indistinguishable from the full model and thus describes the experimental profile very nicely, whereas it fails at the short penetration time of 10 min. The comparison of the full model to the restricted models demonstrates that both the free-energy and the diffusivity profiles are needed to correctly describe the experimental concentration profiles over the entire penetration time range from 10 min to 1,000 min. We also understand from this comparison that the diffusivity profile is important at penetration times up to 10 min, whereas the free-energy profile is required to describe the long-time and the equilibrium behavior accurately.

A robustness check by comparison with results obtained from a reduced dataset is shown in Bootstrapping Analysis and Fig. S4, from which we conclude that the model is able to correctly predict concentration profiles even for times at which limited data are provided.

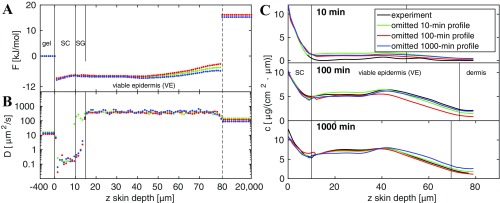

Fig. S4.

Bootstrapping. Reducing the input datasets at 10-min, 100-min, or 1,000-min penetration time produces a higher error in the prediction of the concentration profiles but does not drastically change the predicted free-energy profile in A. The diffusivity profile in B is more susceptible to data reduction. (C) Resulting concentration profiles compared with experimental data.

DXM Concentration Profiles from X-Ray Microscopy

The DXM concentration profiles are generated by soft X-ray absorption spectromicroscopy, which is a label-free technique that yields 2D absolute concentration profiles in thin skin slabs with a lateral resolution below 100 nm (15).

In the sample after 1,000-min penetration time the SC is not aligned perpendicularly with respect to the z axis, as seen in Fig. S1A. Therefore, we first apply an affine transformation and shear the 2D profile until the SC is perpendicular to the z axis; the resulting aligned 2D transmission intensity profile is shown in Fig. S1B.

Absolute DXM concentration profiles are derived from the transmission intensity profiles at two different photon energies as described before (15). The resulting 2D DXM concentration profiles at three different penetration times are shown in Fig. S2. For the theoretical analysis we average the 2D concentration profiles along the lateral position . The resulting 1D concentration profiles are shown in the main text.

To import the experimental data into the inverse diffusion-equation modeling, we apply cubic smoothing splines. This is accomplished by minimizing the sum

| [S1] |

for the 10-min, 100-min, and 1,000-min profiles, where is the number of data points in the th dataset, is the experimental 1D-concentration profile, and is a cubic spline function that serves as an estimator for . The smoothing parameter is set to , which leads to a sufficient smoothing of the cubic splines, as seen in the main text. We used the cubic smoothing spline function implemented in Matlab.

Estimate of Free-Energy Barrier Height Between Epidermis and Dermis

In Fig. S3A the error of the residual is plotted as a function of the free-energy barrier height between viable epidermis and dermis. The error decreases with increasing barrier height and reaches a minimum value of g/(cmm), indicated by a horizontal dashed line, for a barrier height of kJ/mol. For larger barrier height the error stays roughly constant, and we conclude that the value kJ/mol constitutes a lower bound for the free-energy barrier between the viable epidermis and the dermis.

The influence of varying values of on the DXM concentration profile in the epidermis for 1,000-min penetration time is shown in Fig. S3B. For small values of the predicted concentration profile is much lower than the experimental profile, which is shown by a dotted line. Only the profiles for kJ/mol (green line) and kJ/mol (red line) get close to the experimental profile.

The same conclusion can be drawn from the integrated DXM amount in the epidermis, which is shown in Fig. S3C. For low free-energy barrier the integrated DXM amount is much lower than the experimental one because DXM easily penetrates into the dermis. This can in particular be seen for kJ/mol, for which most of the DXM will have penetrated into the dermis and below. We conclude that a sufficient barrier height is crucial to hinder DXM penetration into the dermis.

Calculating the DXM Penetration Amount from Estimated F(z) and D(z) Profiles

The penetrated amount in the epidermis at time is calculated by

| [S16] |

where is approximated by . This yields at time min an epidermal DXM amount of g/cm2. The amount in the dermis at the same time follows as

| [S17] |

In the stationary long-time limit the distribution of DXM can be calculated from the free energy alone. The integrated amount of DXM in the dermis in the long-time limit is determined by

| [S18] |

where the normalization factor is given by

| [S19] |

Analogously, the stationary amount in the epidermis follows as g/cm2 and in the gel as g/cm2.

Bootstrapping Analysis

In the following we do not use the full experimental dataset to derive the underlying free-energy and diffusivity profiles. Instead, we reduce the input dataset for one penetration time. As described in the main text, there are 164 free-energy and diffusivity parameters we need to estimate. The total number of experimental concentration input data points is . For a least-squares algorithm it is important that the number of input data points is equal to or larger than the number of unknown parameters; otherwise the matrix is not invertible and the Gauss–Newton step cannot be performed. If we omit the entire 10-min profile, which consists of 73 data points, we would end up with 160 input data points and thus an underdetermined system. The same holds true for omitting the 100-min and 1,000-min samples. Therefore, we do not omit an entire profile, but rather omit every data point of that profile except the data in the SC, which contributes with 12 data points.

The minimization protocol is the same as used in the main text: 1,000 runs with 250 iterations, a constant free-energy landscape, and arbitrarily chosen diffusivity values in the interval m are used as an initial guess. Only the best of solutions with the smallest error are considered. In Fig. S4 the estimated free-energy and diffusivity profiles and the predicted concentration profiles are shown. When reducing the 10-min input dataset, we still get accurate results for the concentration profile in the SC, but a higher concentration in the viable epidermis is predicted at 10-min penetration time. For 100-min and 1,000-min penetration times the prediction is very accurate compared with the experimental data. The error is calculated to be g/(cmm) and thus is only slightly higher than for the case with complete input data, leading to an error of g/(cmm).

When reducing the 100-min input dataset, there is good agreement for the profiles at 10-min and 1,000-min penetration times, but the 100-min profile understandably shows larger deviations. The error is g/(cmm).

When reducing the 1,000-min input dataset in the minimization procedure, the agreement for the 10-min profile and the 100-min profile is good with an error of g/(cmm), but as one would expect, the deviations at a penetration time of 1,000 min are larger.

The free energy profiles for all three reduced-input datasets are quite similar to each other.

All diffusivity profiles for the reduced 10-min, 100-min, and 1,000-min input data sets show very similar profiles, especially in the SC region. Only the profile for the reduced 10-min dataset shows deviations in the SG, where the diffusivity is predicted to be of the same magnitude as in the VE, which explains why more substance has penetrated through the SC into the VE. We conclude that even with reduced-input data, the estimated free-energy and diffusivity profiles reproduce the experimental concentration profiles at different times in a satisfactory manner.

Conclusions

A method for deriving free-energy and diffusivity profiles from experimental concentration profiles at three different penetration times of drugs in human skin is presented. The approach is generally applicable to all kinds of barrier situations and different diffusors whenever spatially resolved concentration profiles at different times are available and can also be generalized to higher dimensions. For the specific example of DXM penetrating into human skin, our results demonstrate that both diffusivity and free-energy profiles are important to describe the skin barrier: The inhomogeneous free-energy profile is essential to correctly describe the long-time concentration profiles, whereas the diffusivity profile is needed for reproducing the short-time drug penetration. Epidermal skin barrier function against the permeation of DXM is shown to rely on the combination of two key properties, namely a low diffusivity in the SC and a low free energy (i.e., high solubility) in the entire epidermis. Each of these properties by itself severely reduces the DXM permeation through the epidermis, but it is the combination that leads to the exceptionally low and slow DXM transport into the dermis.

The design of efficient drug delivery methods through the epidermis thus meets two challenges: First, the low diffusivity in the SC needs to be overcome. And second, the free-energy barrier from the epidermis, which we show to have pronounced lipophilic affinity, to the hydrophilic dermis severely slows down the permeation of lipophilic drugs. The remedy could consist of modified drugs with balanced lipophilic–hydrophilic character such that the epidermis–dermis affinity barrier is small or even absent.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Concentration Profiles.

Our studies were detailed previously (15, 16) and use ex vivo human 2-cm-thick abdominal skin samples. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Charité Clinic Berlin (approval EA/1/135/06, updated July 2015). It was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and the samples were obtained after the signed consent of the patients. The skin surface was exposed to a 0.4-mm-thick layer of a % ethanol HEC gel formulation containing DXM with a concentration of mg/(cmmm) for penetration times of 10 min, 100 min, and 1,000 min at a temperature of 305 K in a humidified chamber at the saturation point. After gently removing the HEC gel, samples were subsequently treated in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M Na-cacodylate buffer and with K4[(Fe(CN)6] and OsO4 for lipid and DXM fixation, dehydrated, embedded in epoxy resin, sliced into sections of 350-nm thickness, and placed on silicon nitride membranes of 100-nm thickness. X-ray microscopy studies were performed at the synchrotron radiation facility BESSY II (Berlin, Germany) in a scan depth range of 100 m with a step width of 200 nm. The photon energy was tuned to probe exclusively DXM at 530.1 eV via the O transition (16). This allows us to derive the absolute local DXM concentration by using Beer–Lambert’s law; see refs. 15 and 16 for details.

Numerical Solution and Inversion of Diffusion Equation.

For the numerical solution the diffusion Eq. 1 is discretized in space and time and takes the form of a Master equation (41)

| [3] |

where is the time discretization step. We match different spatial discretization schemes: Because experimental concentration data are available at micrometer resolution in the epidermis up to a skin depth of 80 m, we use an equidistant discretization with m in the range m. For the transition rates we use (41)

| [4] |

and , which satisfies concentration conservation and detailed balance. We thus have parameters from the discretized and profiles in the epidermal layer. In the HEC gel, which serves as the DXM source during the penetration, no experimental concentration data are available. We discretize the HEC gel with seven sites and a total thickness of mm, as in the experiment. We discretize the dermis and the subcutaneous layer, for which also no experimental concentration data are available, with 15 sites and a total thickness of 2 cm, as in the experiment. The total number of discretization sites is . The free energies and and the diffusivities and in the HEC gel and the subepidermal layer are assumed to be constant and are treated as free-fitting parameters. Reflective boundary conditions are used at the upper gel surface and at the lower subdermal boundary, as appropriate for the experimental conditions. The total number of parameters is reduced from 164 to 162 due to the fact that only free-energy differences and diffusivity sums of neighboring sites enter Eq. 4. For more details see Variable Discretization of the 1D Diffusion Equation. The concentration profile at time follows from Eq. 3 as

| [5] |

where is the rate matrix defined in Eq. 4 and the continuous limit has been taken to express the th power by the matrix exponential. Eq. 5 can be used to numerically solve the diffusion equation for any initial distribution and diffusivity and free-energy profiles and . To determine and based on experimental concentration profiles at different times, we minimize the squared sum of deviations

| [6] |

where is the number of experimental concentration data per profile and is the number of experimental concentration profiles. We use data points for the 10-min profile and data points for the 100-min and 1,000-min profiles, taken from the smoothed splines (black lines) in Fig. 2A. The total number of 233 = 73 + 80 + 80 input data points is necessarily higher than the number of 162 free-energy and diffusivity parameters we need to determine. The profile corresponds to the initial condition where DXM is homogeneously distributed in the gel only. For minimization of the error function Eq. 6 we use the trust-region iteration approach (42, 43); see Trust-Region Optimization for Constrained Nonlinear Problems for details. As an initial guess for the minimization we use a flat free-energy profile and choose random values for in the range m. We perform 1,000 runs with different initial values for with a maximal number of 250 iterations per run. For our results, we use only the best of solutions with a residual error g/(cmm). A perfect solution with an error of is never observed, which reflects that our equation system is overdetermined and at the same time input concentration profiles come from different skin samples. In the constant-F and constant-D models we obtains errors g/(cmm) and g/(cmm) for the best of the solutions, significantly larger than for the full model.

Variable Discretization of the 1D Diffusion Equation

For modeling of the diffusion, we separate the total system into three layers, the HEC gel, the epidermis, and the layer underneath that includes the dermis and parts of the subcutaneous fat layer. Experimental measurements are available within the epidermis only over a thickness of m. The HEC gel layer and the subepidermal layer (which is called dermis in the remainder of this article for brevity) have thicknesses of 0.4 mm and 2 cm, respectively. We use a constant discretization width of 1 m for the epidermis and variable discretization width in the HEC gel and the dermis. Note that the free energy and the diffusivity are assumed to be constant in the HEC gel and in the dermis. For constant free energy and diffusivity the diffusion equation reduces to

| [S2] |

We derive a discretized version of Eq. S2 for a nonuniform discretization of the spatial coordinate . Let be the distance between two discretization points. Performing a Taylor expansion up to second order yields

| [S3] |

| [S4] |

Multiplying the first equation with and the second equation with and adding both equations gives for the second derivative

| [S5] |

| [S6] |

from which we can read off the rates

| [S7] |

| [S8] |

| [S9] |

Using Eq. S6 we numerically solve the diffusion equation for variable discretization widths in areas of constant free energy and diffusivity. In areas of nonconstant free energy and diffusivity but equidistant discretization width, we use the discretization given in the main text.

Trust-Region Optimization for Constrained Nonlinear Problems

To obtain the profiles for the free energy and diffusivity from the given experimental concentration profiles, we introduce the sum of the squared residuals

| [S10] |

| [S11] |

where is the residual vector containing the errors of the predicted and observed concentrations as a function of . The vector has and the residual vector has components.

To minimize Eq. S11 we approximate by a first-order Taylor expansion

| [S12] |

with , where describes the Jacobian of at and gives for

| [S13] |

with denoting the gradient of and approximating the Hessian of . To obtain a new approximation in the next iteration step , we trust the approximation only within a trust-region radius depending on the current iteration step . We state the following trust-region problem,

| [S14] |

where is a scaling matrix that transforms constraints we assume on the solution space of or into an unconstrained problem . Note that two kinds of constraints are introduced: (i) One comes from restricting the parameter space to a subspace of and (ii) the other constraint comes from minimizing the function only within a trust-region . How accurately is approximated by can be estimated by the reduction value

| [S15] |

where the numerator describes the actual reduction and the denominator the predicted reduction. If is close to , the approximation is good and the step is accepted with an increase of the trust-region . If the approximation is bad, then and the trust region will be decreased.

Finding the minimum of within the trust-region radius could be done by applying the Gauss–Newton or steepest-descent algorithm to , which would involve solving a linear system. We use a so-called dogleg strategy for trust-region problems that is a hybrid of Gauss–Newton and steepest descent. First, we calculate the steepest-descent direction and find the steepest point—the Cauchy point—along that direction within the trust-region radius. From the Cauchy point we calculate the vector pointing to the Gauss–Newton point. The intersection between that vector and the trust-region boundary is the new point . We assume no constraints for but constrain to m, where the upper bound is four times larger than the diffusion constant of DXM in water. A total of 1,000 runs with 250 iterations per run are performed where only the best of solutions are kept for further analysis. We use the trust-region reflective routine implemented in Matlab.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Weigand, I. Bykova, and M. Bechtel from the Max-Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems for experimental data acquisition. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft within grants from Sonderforschungsbereich (SFB) 1112 and SFB 1114.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1620636114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cevc G, Vierl U. Nanotechnology and the transdermal route: A state of the art review and critical appraisal. J Control Release. 2010;141(3):277–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieleg O, Ribbeck K. Biological hydrogels as selective diffusion barriers. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21(9):543–551. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanco E, Shen H, Ferrari M. Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(9):941–951. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaefer H, Zesch A, Stüttgen G. Skin Permeability. Springer; Berlin: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elias P. Epidermal barrier function - intercellular lamellar lipid structures, origin, composition and metabolism. J Control Release. 1991;15(3):199–208. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatt PP, Hanna MS, Szeptycki P, Takeru H. Finite dose transport of drugs in liquid formulations through stratum corneum: Analytical solution to a diffusion model. Int J Pharm. 1989;50(3):197–203. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kubota K. Finite dose percutaneous drug absorption: A basic program for the solution of the diffusion equation. Comput Biomed Res. 1991;24(2):196–207. doi: 10.1016/0010-4809(91)90030-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anissimov YG, Roberts MS. Diffusion modeling of percutaneous absorption kinetics. 1. Effects of flow rate, receptor sampling rate, and viable epidermal resistance for a constant donor concentration. J Pharm Sci. 2000;89(1):144–144. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6017(200001)89:1<144::AID-JPS14>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasting GB. Kinetics of finite dose absorption through skin 1. Vanillylnonanamide. J Pharm Sci. 2001;90(2):202–212. doi: 10.1002/1520-6017(200102)90:2<202::aid-jps11>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasting GB, Miller MA. Kinetics of finite dose absorption through skin 2: Volatile compounds. J Pharm Sci. 2006;95(2):268–280. doi: 10.1002/jps.20497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rim JE, Pinsky PM, van Osdol WW. Using the method of homogenization to calculate the effective diffusivity of the stratum corneum with permeable corneocytes. J Biomech. 2008;41(4):788–796. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naegel A, et al. Finite dose skin penetration: A comparison of concentration-depth profiles from experiment and simulation. Comput Vis Sci. 2011;14(7):327–339. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naegel A, Heisig M, Wittum G. Detailed modeling of skin penetration - an overview. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(2):191–207. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitragotri S, et al. Mathematical models of skin permeability: An overview. Int J Pharm. 2011;418(1):115–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamamoto K, et al. Selective probing of the penetration of dexamethasone into human skin by soft x-ray spectromicroscopy. Anal Chem. 2015;87(12):6173–6179. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto K, et al. Core-multishell nanocarriers: Transport and release of dexamethasone probed by soft x-ray spectromicroscopy. J Control Release. 2016;242:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bass FM. A new product growth for model consumer durables. Manag Sci. 1969;15(5):215–227. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ratcliff R, McKoon G. The diffusion decision model: Theory and data for two-choice decision tasks. Neural Comput. 2008;20(4):873–922. doi: 10.1162/neco.2008.12-06-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sisan D, Halter M, Hubbard J, Plant A. Predicting rates of cell state change caused by stochastic fluctuations using a data-driven landscape model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(47):19262–19267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207544109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Straub J, Berne B, Roux B. Spatial dependence of time-dependent friction for pair diffusion in a simple fluid. J Chem Phys. 1990;93(9):6804–6812. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marrink SJ, Berendsen H. Simulation of water transport through a lipid membrane. J Phys Chem. 1994;98(15):4155–4168. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu P, Harder E, Berne B. On the calculation of diffusion coefficients in confined fluids and interfaces with an application to the liquid-vapor interface of water. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108(21):6595–6602. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bollinger J, Jain A, Truskett T. Structure, thermodynamics, and position-dependent diffusivity in fluids with sinusoidal density variations. Langmuir. 2014;30(28):8247–8252. doi: 10.1021/la5017005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bryngelson J, Wolynes P. Intermediates and barrier crossing in a random energy model (with applications to protein folding) J Phys Chem. 1989;93(19):6902–6915. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krivov S, Karplus M. Diffusive reaction dynamics on invariant free energy profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(37):13841–13846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800228105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Best R, Hummer G. Coordinate-dependent diffusion in protein folding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(3):1088–1093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910390107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung H, Piana-Agostinetti S, Shaw D, Eaton W. Structural origin of slow diffusion in protein folding. Science. 2015;349(6255):1504–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.aab1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berezhkovskii A, Szabo A. Time scale separation leads to position-dependent diffusion along a slow coordinate. J Chem Phys. 2011;135(7):074108–074112. doi: 10.1063/1.3626215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lund SP, Hubbard JB, Halter M. Nonparametric estimates of drift and diffusion profiles via Fokker-Planck algebra. J Phys Chem B. 2014;118(44):12743–12749. doi: 10.1021/jp5084357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hummer G. Position-dependent diffusion coefficients and free energies from Bayesian analysis of equilibrium and replica molecular dynamics simulations. New J Phys. 2005;7:516–523. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hinczewski M, von Hansen Y, Dzubiella J, Netz RR. How the diffusivity profile reduces the arbitrariness of protein folding free energies. J Chem Phys. 2010;132(24):245103–245112. doi: 10.1063/1.3442716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carmer J, van Swol F, Truskett T. Note: Position-dependent and pair diffusivity profiles from steady-state solutions of color reaction-counterdiffusion problems. J Chem Phys. 2014;141(4):046101–046102. doi: 10.1063/1.4890969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moussy Y, Hersh L, Dungel P. Distribution of [3H]dexamethasone in rat subcutaneous tissue after delivery from osmotic pumps. Biotechnol Prog. 2006;22(3):819–824. doi: 10.1021/bp060031j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sparr E, Wennerström H. Responding phospholipid membranes–interplay between hydration and permeability. Biophys J. 2001;81(2):1014–1028. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75759-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. ChemIDplus (2015) Dexamethasone in ChemIDplus database of United States National Library of Medicine (NLM). Available at chem.sis.nlm.nih.gov/chemidplus/rn/50-02-2. Accessed December 15, 2016.

- 36.Jepps OG, Dancik Y, Anissimov YG, Roberts MS. Modeling the human skin barrier - towards a better understanding of dermal absorption. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(2):152–168. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hashimoto K. Intercellular space of the human epidermis as demonstrated with lanthanum. J Invest Dermatol. 1971;57(1):17–31. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12292052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Furuse M, et al. Claudin-based tight junctions are crucial for the mammalian epidermal barrier: A lesson from claudin-1-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2002;156(6):1099–1111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kubo A, Nagao K, Yokouchi M, Sasaki H, Amagai M. External antigen uptake by Langerhans cells with reorganization of epidermal tight junction barriers. J Exp Med. 2009;206(13):2937–2946. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirschner N, Brandner JM. Barriers and more: Functions of tight junction proteins in the skin. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1257(1):158–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bicout DJ, Szabo A. Electron transfer reaction dynamics in non-Debye solvents. J Chem Phys. 1998;109(6):2325–2338. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nocedal J, Wright S. Numerical Optimization. Springer; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conn AR, Gould NIM, Toint PL. 2000. Trust Region Methods [Soc Industrial Appl Math (SIAM), Philadelphia]