Abstract

Despite the causal relationship established between malignant mesothelioma (MM) and asbestos exposure, the exact mechanism by which asbestos induces this neoplasm and other asbestos-related diseases is still not well understood. MM is characterized by chronic inflammation, which is believed to play an intrinsic role in the origin of this disease. We recently found that asbestos activates the nod-like receptor family member containing a pyrin domain 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome in a protracted manner, leading to an up-regulation of IL-1β and IL-18 production in human mesothelial cells. Combined with biopersistence of asbestos fibers, we hypothesize that this creates an environment of chronic IL-1β signaling in human mesothelial cells, which may promote mesothelial to fibroblastic transition (MFT) in an NLRP3-dependent manner. Using a series of experiments, we found that asbestos induces a fibroblastic transition of mesothelial cells with a gain of mesenchymal markers (vimentin and N-cadherin), whereas epithelial markers, such as E-cadherin, are down-regulated. Use of siRNA against NLRP3, recombinant IL-1β, and IL-1 receptor antagonist confirmed the role of NLRP3 inflammasome–dependent IL-1β in the process. In vivo studies using wild-type and various inflammasome component knockout mice also revealed the process of asbestos-induced mesothelial to fibroblastic transition and its amelioration in caspase-1 knockout mice. Taken together, our data are the first to suggest that asbestos induces mesothelial to fibroblastic transition in an inflammasome-dependent manner.

Malignant mesothelioma (MM) is a fatal cancer of the pleural or peritoneal mesothelium. MM has been causally related to asbestos exposure for >50 years,1 yet the mechanisms involved in the development of the disease are still poorly understood. With a latency period of 10 to 40 years and a propensity toward resistance and recurrence, MM is in dire need of new drug targets for combination therapy and biomarkers for early detection. Chronic inflammation has been implicated in the development and progression of MM,2 and prevalently high circulating cytokines, which are incidentally associated with fibrosis (IL-6, platelet-derived growth factor, and IL-8), have been used as prognosticators of survival for patients with MM.3, 4 A recent massive parallel sequencing study of immortalized and primary mesothelial cells after asbestos exposure found that the most highly up-regulated genes after asbestos exposure belong to inflammatory networks,5 further implicating inflammation as an important factor in the development of asbestos-related diseases.

We previously reported that asbestos activates the nod-like receptor containing a pyrin domain 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, leading to the secretion of mature IL-1β and IL-18 in human mesothelial cells (HMCs).6 In these cells, however, the activation of the inflammasome is protracted, leading to the accumulation of IL-1β and IL-18.6 IL-1β signaling up-regulates the secretion of the cytokines IL-6 and IL-8, which play a major role in lung fibrosis.7 In addition to promoting fibrosis, IL-1β induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) in corneal endothelial cells and induces stemness in colon cancer cells through the activation of transcription factors that regulate the mesenchymal phenotype.8, 9 On the other hand, NLRP3 and apoptosis speck-like protein containing a CARD domain (ASC) (an adaptor protein for the assembly of the inflammasome) both play a role in transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling independent of their inflammasome activity in tubular epithelial cells.10 We therefore hypothesized that the NLRP3 inflammasome and its products facilitate mesothelial to fibroblastic transition (MFT) of HMCs in response to asbestos exposure. As such, asbestos-induced MFT may serve as the initial step in MM tumorigenesis. In this study, we investigate the process of MFT in response to asbestos exposure at the transcriptional and translational levels and the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome components in the process, using in vitro and in vivo models. We found for the first time that asbestos-induced inflammasome activation results in IL-1β secretion, which promotes MFT through the signaling cascades elicited by IL-8 and IL-6, which may involve tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 (TFPI2) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2).

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Immortalized human peritoneal [LP9/hTERT (LP9)], primary human pleural (HPM-3), and peritoneal (HM3) mesothelial cells were purchased from Brigham and Women's Hospital (Boston, MA) and cultured as previously described.6 All cells were grown to 90% to 95% confluency. All experiments were repeated at least twice or more.

Asbestos Fiber Preparation for Exposure

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences reference samples of crocidolite asbestos have been previously characterized.11 Fibers were sterilized and suspended as previously described.6

Cell Treatments with Asbestos, IL-1β, or the IL-1 Receptor Antagonist

To assess the response of HMCs to long-term asbestos exposure, cells were exposed to two pulses of 1 μg/cm2 (surface area equivalent of 15 × 10−6 μm2/cm2) (LP9 and HM3) or 5 μg/cm2 (surface area equivalent of 75 × 10−6 μm2/cm2) (HPM3 because these cells were less sensitive to asbestos) of crocidolite asbestos 48 hours apart. Medium was refreshed every 48 hours (until cells were harvested) to ensure that cells were not nutrient starved; thus, it was imperative to replace any asbestos fibers lost in the process of switching out media. LP9 and HM3 cells had a permanently altered cell shape 10 to 14 days after the initial asbestos exposure. For HPM3 cells, duration to transition was much shorter (1 week after the addition of the first asbestos pulse). Thus, cells were maintained in fresh medium for the last 72 hours with no ill effects before termination of the experiment. A schematic representation of asbestos pulses and medium changes is depicted in Figure 1A. In experiments where the effect of asbestos-induced IL-1β signaling on MFT was being assessed, recombinant IL-1β (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) or its receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) (Insight Genomics, Sterling VA) were also replaced during the first 48 hours of medium change. HPM3 or LP9 cells were pretreated with two pulses of either 1 ng/mL of IL-1β or 150 ng/mL of IL-1Ra 1 hour before asbestos exposure. Both agents were stored in 0.1% bovine serum albumin solutions, and as such, control cells received equal amounts of 0.1% bovine serum albumin for the same duration as a vehicle control. Cells receiving both IL-1Ra and IL-1β were pretreated with the antagonist 1 hour before treatment with IL-1β. Effect of asbestos exposure on viability of different HMCs revealed that peritoneal cells are more sensitive to asbestos exposure than pleural mesothelial cells.5, 12 Precisely, we observed 35% to 40% cell death in peritoneal mesothelial cells (LP9 and HM3) in response to asbestos exposure compared with 15% to 20% cell death in pleural mesothelial cells (HPM3 and HPM4).5 Glass beads were used as negative control at equal particle surface area concentration and revealed no significant effect on viability and other parameters.6, 12

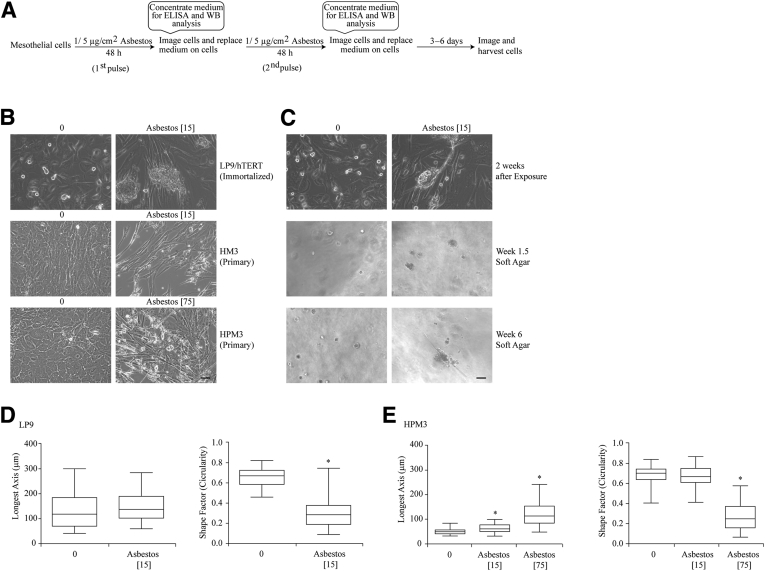

Figure 1.

Asbestos (Asb) exposure induces a morphologic change in human mesothelial cells. A: Schematic representation of Asb exposure schedule for induction mesothelial to fibroblastic transition. B: Exposure of LP9, HM3 (peritoneal), and HPM3 (pleural) cells to Asb (1 [peritoneal cells] [15 × 10−6 μm2/cm2 (Asb 15)] and 5 μg/cm2 [75 × 10−6 μm2/cm2 (Asb 75)] [pleural cells]) for 2 weeks and 1 week, respectively, resulted in morphologic changes to the cells during exposure. C: Fibroblastic-looking LP9 cells from B were grown on soft agar to determine whether the cells were transformed and capable of forming colonies. All micrographs were imaged on Olympus IX70 inverted microscope. D and E: Quantitative depiction of morphologic changes of LP9 (D) and HPM3 (E) cells as determined using the MetaMorph image analysis software version 7.8.9.0. The integrated morphologic and regional measurement tools were used to determine the shape factor (circularity) and longest axis (length) of cells, respectively. Numbers in brackets denote surface area concentrations of asbestos. ∗P < 0.05 versus control. Scale bars = 50 μm (B and C). ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; WB, western blot.

Assessment of Cell Morphologic Findings

Cells were inspected visually for changes in morphologic findings (acquisition of a spindle-like shape and reorientation or alignment of cells into a whorl) and imaged 48 hours after each pulse and at time of harvest using an Olympus IX70 inverted light microscope (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA) in phase contrast with a 20× objective. Cells were also followed visually with each media change to ascertain whether transition in cell morphologic findings remained stable and to determine when transition in shape became more uniform.

Quantitation of Cell Morphologic Features

The effects of asbestos exposure on the morphologic features of cells were assessed using the integrated morphologic analysis module in the MetaMorph Image Analysis software version 7.8.9.0 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). A total of 30 cells per dish were outlined in MetaMorph to obtain a measure of their perimeters and total area, which was then used to determine the shape factor for each cell (A indicating area and P indicating perimeter):

| (1) |

The shape factor is a value that ranges from 0 to 1 as a measure of how circular an object is (0 represents a flattened noncircular object, whereas 1 represents a perfect circle). The change in length of the cells was also determined using the region measurements tool to measure the longest axis (longest chord through the cell) of each of the cells as well. Data obtained from a total of 60 cells per group were then pasted into GraphPad Prism version 6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA) to yield a minimum to maximum plot for each condition and for statistical analysis of the resulting distribution.

Cell Transformation Assay

To determine whether LP9 cells that had undergone MFT were capable of anchorage-independent growth, cells were trypsinized at the end of the MFT experiment and used for a CytoSelect 96-well cell transformation assay (Cell Biolabs Inc., San Diego, CA) per the manufacturer's protocol. Wells were monitored for colony formation after 1 week in culture and imaged in phase contrast on the Olympus IX70 microscope each week.

PCR Array

To determine whether the transcripts of genes involved in the EMT pathway were altered in response to asbestos exposure, LP9 and HPM3 cells were exposed to asbestos (5 μg/cm2) for 48 hours or 1 week (HPM3 only). As a positive control, LP9 cells were treated with 10 ng/mL of TGF-β for 48 hours to induce MFT. Cells were then lysed for total RNA extraction using the Qiagen RNeasy Plus Mini kit as per the manufacturer's directions (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). After ensuring the integrity of the RNA samples, 500 ng of RNA was used for cDNA synthesis to be used in the Human EMT pathway RT2 Profiler PCR Array as described previously.13 Data obtained were then analyzed using the online SA Biosciences data analysis template.

Transfection Experiments

The role of the inflammasome in asbestos-induced MFT was examined in mesothelial cells using siRNA approaches. Ninety percent confluent LP9 cells were transiently transfected with On-Target Smart Pool siNLRP3 [ThermoScientific (Life Technologies), Grand Island, NY] or nontargeted control (siControl) constructs 32 hours before asbestos exposure to study the effects of reduced NLRP3 protein levels on MFT as previously described.13 Additional experiments were performed with 4 single small interfering NLRP3 (siNLRP3) and nontarget controls [ThermoScientific (Life Technologies), Grand Island, NY] as described above.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were lysed in 4× sample buffer and boiled at 95°C for 15 minutes as previously described.14 For analysis of EMT parameters, 40 μg of protein was loaded on 15%, 10%, or 7.5% SDS-PAGE gels to resolve proteins. Immunoblotting for EMT markers was performed on transferred proteins using E-cadherin, snail, slug, N-cadherin, vimentin, and zonula occludens protein 1 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Western blot analysis was performed on media supernatants or peritoneal lavage fluid (PLF) after concentration. Equal volumes of media supernatants or PLF were concentrated using StrataClean resin beads (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) as previously reported.15 An equal volume of 4× sample buffer was added to beads after media had been aspirated and boiled for 5 minutes at 95°C. Thereafter 10 to 15 μL of each sample was resolved on a 15% SDS-PAGE for subsequent immunoblotting for the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8, FGF2, TFPI2, and the danger-associated molecule HMGB1 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA).

ELISA for IL-18 and IL-1β

Media supernatants from in vitro experiments or PLF from in vivo experiments were concentrated in Amicon centrifugal filtration units with a molecular weight limit of 10 kDa (Millipore, Billerica MA) as described previously.6 The levels of IL-1β and IL-18 secreted in response to asbestos exposure were then measured using the Human Quantikine IL-1β/IL-1f2 Immunoassay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and Human IL-18 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (MBL, Woburn, MA), respectively, following the manufacturer's directions. Values are expressed as picograms of IL-1β or IL-18 per milliliter of total culture supernatant initially collected.

Mouse Models of Asbestos Exposure

To study in vivo effect of asbestos on mesothelial cell transition, we selected i.p. injection model of asbestos exposure developed by Goodlick et al16 and recently used by various groups.17, 18 All these studies revealed the development of early inflammation,17 peritoneal fibrosis, and eventually MM in mice16, 18 in response to asbestos. Inhalation or aspiration models were not considered for this study because asbestos exposure by either model did not cause peritoneal fibrosis or MM in mice. Age- (8 to 10 weeks) and sex-matched NLRP3−/−19 and Cas-1−/− mice20 (C57/BL/6 background, obtained from Dr. Matthew Poynter, University of Vermont, and bred at the University of Vermont College of Medicine) and their wild-type C57BL/6 (Charles River Laboratory, Wilmington, MA) counterparts were housed in isolators with ad libitum access to food and water according to the University of Vermont Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. Mice (6 to 8 mice per group) received either 500 μL of 0.9% sterile saline or 500 μL of 200 μg/mL of crocidolite asbestos i.p. once a week for 8 weeks as previously described.16 As a negative control, mice were injected with glass beads (Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA) at an equal surface area concentration (500 μL of 1076 mg/mL). Mice were euthanized with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital after which the peritoneal walls and diaphragms were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde with a specific orientation of mesothelial lining facing outward. Cross sections of paraffin-embedded peritoneal walls were made, hematoxylin and eosin stained, and examined histologically as previously described by Donaldson et al.21 Images were obtained using an Olympus BX50 with the Retiga Magnafire 2000R camera (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA) (20× objective). Peritoneal wall sections were also stained for collagen (Col 1α1) (PhophoSolutions, Aurora, CO), pan-cytokeratin (antibodies-online.com, Atlanta, GA), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and vimentin (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA). Immunofluorescently stained sections were imaged on the Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss, Peabody, MA). All mice were confirmed for their genotype at the beginning and end of the experiment.

MetaMorph Analysis for Quantitation of Thickening of Peritoneum

Thickening of the parietal submesothelium after asbestos exposure was determined as follows. Images of peritoneal wall sections obtained on the Olympus BX50 and imported into the offline version of the MetaMorph imaging analysis software and calibrated for measurements. With the line tool, the distance from the edge of the mesothelium to the border between the muscle cells underneath was measured and exported into Excel. Five measurements were taken for each of the 5 images taken per sample and the means ± SEM of the 25 measurements were used to plot a graph of the increase in thickness of the parietal mesothelium in response to asbestos exposure.

PLF Collection and Analysis for Total Cell Counts, Differentials, and Cytokines

At the time of harvest, PLF was collected from each animal as previously described.22 The resultant lavage fluid was drawn out for the measurement of cytokines [by ELISA (IL-1β and IL-18) and Western blot analysis (FGF2, IL-6 and TFPI2)] and identification of inflammatory cell infiltrating the peritoneum after asbestos exposure. Cells collected from PLF were used for cytospin preparation for differential cell counts after determination of total cell numbers as previously described.22

Immunohistochemistry and Immunocytochemistry

To assess EMT marker expression in response to asbestos exposure, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of peritoneal walls were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated in decreasing concentrations of ethanol. Thereafter, samples were immunofluorescently stained as previously described.23 Peritoneal wall sections were stained for pan-cytokeratin (AE1+AE3) (antobodies-online.com), vimentin, α-SMA, and Col1α1. Primary antibodies were used at a ratio of 1:100 or the recommended dilution from the manufacturer. The appropriate secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 (goat anti-rabbit) or Alexa Fluor 588 (goat anti-mouse) were used at a dilution of 1:400.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in duplicate or triplicate and repeated at least twice. A one-way analysis of variance followed by a Newman-Keuls procedure for adjustment of multiple pairwise comparisons or the t-test was applied to all data points to establish the significance of observed differences between the various experimental groups. P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad software program version 6.0 (GraphPad Sofware Inc.).

Results

Asbestos Exposure Induces MFT in Mesothelial Cells as Depicted by Changes in Gene Profile

To determine whether asbestos was capable of inducing a MFT, LP9 and HPM3 were exposed to asbestos for 48 hours or 1 week with TGF-β as a positive control, and an EMT PCR array was performed. Expression levels of genes related to an epithelial phenotype, such as CDH1, KRT19, KRT7, MST1R, which is usually expressed on ciliated epithelial cells, and F11R, a regulator of tight junction assembly, were reduced after asbestos exposure in both cell lines. Changes in the transcript levels of genes related to fibroblastic phenotype were different in magnitude between the two cell types in response to asbestos. For instance, although SNAI1 was down-regulated at 24 and 48 hours in LP9 cells after asbestos exposure, there was a twofold increase seen in HPM3 cells after 1 week of asbestos exposure (Table 1). TIMP1 was up-regulated by as much as 36-fold in the LP9s (after 24 hours) but did not make the twofold cutoff in HPM3 cells after asbestos exposure (Supplemental Tables S1 and S2). TFPI2 levels, however, increased in both cell types (Table 1) but to a greater magnitude in LP9 cells (52-fold in LP9s and 13-fold in HPM3). The TGF family member BMP2 was up-regulated to the same extent in both cell lines in response to asbestos (Table 1).

Table 1.

Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition Related Gene Expression Changes in Mesothelial Cells in Response to Asbestos Exposure

| Gene | LP9 (24 hours) | LP9 (48 hours) | HPM3 (48 hours) | HPM3 (1 week) | TGF-β |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMP2 | 3.765 | 3.6387 | 3.7264 | 4.3582 | −1.3692 |

| CDH1 | −6.6193 | −5.5775 | −12.3847 | 1.5624 | −2.3526 |

| COL1A2 | −4.3086 | −4.8255 | −6.3425 | −2.7621 | 6.0221 |

| COL3A1 | −2.2648 | −3.5446 | −7.5456 | −1.415 | 1.1224 |

| F11R | −2.3134 | −3.9013 | −1.9703 | −2.1186 | −1.1799 |

| GNG11 | 3.842 | 4.4137 | 2.6357 | 3.1512 | 1.9597 |

| KRT19 | −7.8025 | −7.2188 | −11.0012 | −1.7105 | −13.8892 |

| KRT7 | −3.121 | −5.5928 | −2.9612 | −1.7818 | −3.3246 |

| MST1R | −2.6243 | −4.0842 | −4.2371 | −2.7908 | −8.288 |

| NODAL | 2.916 | −1.4034 | 3.2188 | 6.2224 | 1.6575 |

| PDGFRB | −6.3478 | −5.982 | −2.6859 | −1.8618 | 1.4718 |

| SNAI1 | −4.2379 | −12.1875 | −1.3492 | 2.147 | 3.1556 |

| SPARC | −2.888 | −4.2795 | −6.402 | −3.1342 | 1.8388 |

| STEAP1 | 1.6883 | 2.4375 | 2.3314 | 3.5186 | −1.3104 |

| TFPI2 | 52.4955 | 51.2382 | 13.0143 | 10.8795 | 4.1882 |

| TGFB2 | −2.1052 | −2.2664 | 3.1156 | 1.5631 | 1.6297 |

LP9 and HPM3 cells were exposed to asbestos (5 μg/cm2) for the indicated times, and whole RNA extracted from these cells was analyzed for gene expression levels of the epithelial to mesenchymal transition pathway proteins in an epithelial to mesenchymal transition PCR array. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (10 ng/mL) was used as a positive control.

Asbestos Exposure Causes Morphologic Changes in Mesothelial Cells

Exposure of LP9 and HM3 cells to asbestos for 2 weeks with fresh medium every 48 hours resulted in morphologic changes of the cells to a fibroblastic cell type (Figure 1B). Although exposure to 1 μg/cm2 of asbestos had no effect on HPM3 cells (data not shown), exposure to 5 μg/cm2 of asbestos resulted in morphologic changes in 1 week (Figure 1B). In a colony-forming transformation assay, only asbestos-exposed LP9 cells, which appeared as fibroblastic formed colonies after 2 to 6 weeks on soft agar, and some colonies were still associated with asbestos fibers (Figure 1C). Morphometric analysis of LP9 and HPM3 cells in Figure 1B revealed that the length of LP9 cells did not change significantly with exposure to asbestos (Figure 1D). However, there was a significant decrease in the circularity of these cells on exposure to asbestos (Figure 1D) (P < 0.05 compared with control). For HPM3 cells, the length of the cells increased with exposure to asbestos in a dose-dependent manner, and the circularity (shape factor) of the cells decreased with exposure to the higher dose of asbestos alone (Figure 1E) (P < 0.05 compared with control).

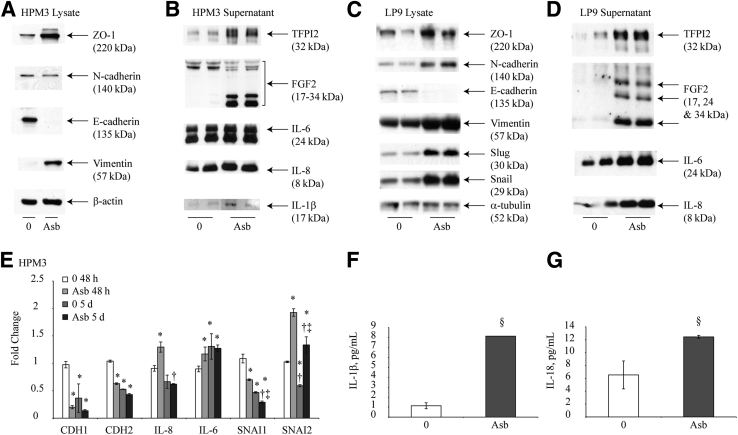

Asbestos Exposure Causes Changes in Epithelial and Mesenchymal Markers in Human Mesothelial Cells

Assessment of the expression levels of epithelial and mesenchymal markers after asbestos exposure revealed a marked reduction in the expression levels of E-cadherin in both LP9 and HPM3 cells (Figure 2, A and C). The transcription factors snail and slug, both down-regulators of E-cadherin expression, were up-regulated in response to asbestos exposure in LP9 cells (Figure 2A). The mesenchymal markers vimentin and N-cadherin were up-regulated in LP9 cells (Figure 2C), whereas HPM3 only exhibited an increase in vimentin protein levels (Figure 2A). No significant changes in snail or slug protein levels were observed in HPM3 cells. IL-6, IL-8, FGF2, and TFPI2 levels were also markedly elevated in media after 96 hours of asbestos exposure as determined by Western blot analysis of media supernatants pooled from both pulses of asbestos exposure (Figure 2, B and D). Increases in IL-8 and IL-6 levels in HPM3 cells were, however, not significant after 96 hours (Figure 2B). β-actin (Figure 2A) or α-tubulin (Figure 2D) was used as a loading control for lysate samples. For medium samples, Ponceau stain was used to confirm equal loading attributable to unavailability of an appropriate loading control (data not shown). Assessment of mRNA levels for CDH1, CDH2, IL-8, IL-6, SNAI1, and SNAI2 by real-time quantitative PCR at 48 hours and 5 days revealed that asbestos exposure decreases the transcript levels of E-cadherin as early as 48 hours after exposure (Figure 2E). N-cadherin (which is constitutively expressed by mesothelial cells) levels were surprisingly decreased after 48 hours as well and exhibited a decrease in transcript levels over time in moderate but significant amounts, which were not affected by asbestos exposure after 5 days (Figure 2E). Transcript levels of IL-8 increase initially after 48 hours of exposure but decrease over time with or without asbestos exposure (Figure 2E). IL-6 transcript levels also increase significantly with asbestos exposure but only after the first 48 hours (Figure 2E). Although SNAI1 levels decrease with asbestos exposure and with time, asbestos exposure significantly increased SNAI2 transcript levels at both time points (Figure 2E). Levels of IL-1β and IL-18 were also found to be increased in supernatant of HPM3 cells when measured by ELISA (Figure 2, F and G). Similar results were obtained from LP9 cells published previously.6

Figure 2.

Asbestos alters markers of a mesothelial to fibroblastic transition in human mesothelial cells. A: Western blot analysis performed on cell lysates from HPM3 exposed to asbestos 1 week after the first dose [Asb 75 (5 μg/cm2 asbestos)]. B: Western blot analysis of pooled culture supernatants from HPM3 cells in A 96 hours after the first asbestos pulse (48 hours after second pulse). C: Western blot of LP9 cell lysates 2 weeks after the first asbestos pulse [Asb 15 (1 μg/cm2)]. D: Western blot analysis of pooled culture supernatants from LP9 cells in C 96 hours after the first asbestos pulse. E: Fold change of CDH1, CDH2, IL-8, IL-6, SNAI1, and SNAI2 transcripts in HPM3 cells exposed to asbestos (5 μg/cm2) for 48 hours or 5 days as determined by quantitative RT-PCR. F and G: IL-1β (F) and IL-18 (G) cytokine levels in pooled culture supernatants from A 48 hours after first asbestos pulse. ∗P < 0.05 versus 48-hour control; †P < 0.05 versus 48-hours asbestos exposure; ‡P < 0.05 versus 5-days control (E); §P < 0.05 versus control (0) (F).

The NLRP3 Inflammasome Augments Asbestos-Induced MFT

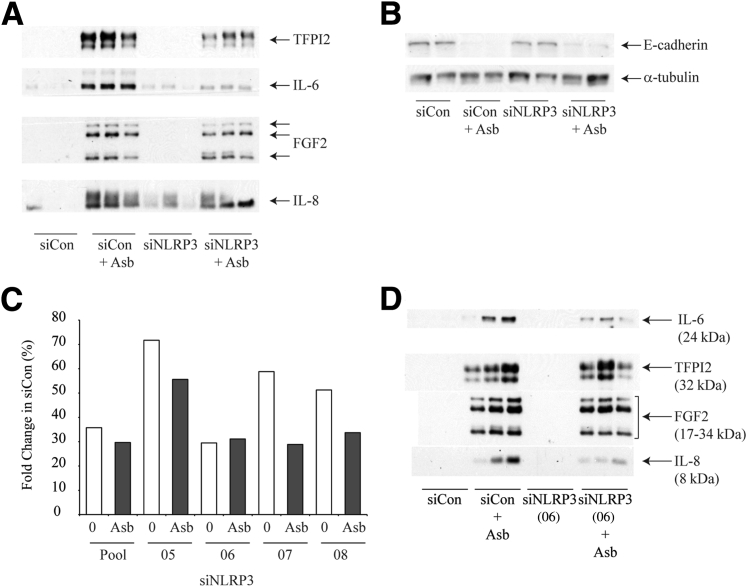

In assessing the role of NLRP3 in the asbestos-induced MFT observed, the levels of FGF2, IL-8, IL-6, and TFPI2 were all found to be decreased in medium in response to asbestos exposure in siNLRP3 transfected cells when compared with control transfected cells (Figure 3A). The loss of E-cadherin in response to asbestos exposure was not reversed significantly by inhibition of NLRP3 expression by siRNA (Figure 3B). Lack of sample material prevented us from measuring IL-1β and IL-18 in this experiment. These results indicate a partial role of NLRP3 in asbestos-induced MFT. No significant effect on morphologic change was found because that is a long-term experiment, whereas transient transfection effects last only for a short duration. The reduction of asbestos-induced NLRP3 activation in LP9 cells after siRNA treatment was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR and revealed a significant decrease in NLRP3 transcript levels (priming) in response to asbestos exposure after knockdown by siRNA 72 hours after transfection (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Asbestos (Asb)–induced mesothelial to fibroblastic transition is partially dependent on nod-like receptor family member containing a pyrin domain 3 (NLRP3). A: Western blot analysis of culture supernatants from pooled small interfering NLRP3 (siNLRP3) (and scrambled controls) transfected LP9 cells 48 hours after Asb exposure (5 μg/cm2). B: Western blot analysis of E-cadherin levels 10 days after Asb exposure. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. C:NLRP3 transcript level expressed as percent expression relative to respective scrambled control (siControl) 72 hours after transfection of LP9 cells. Cells were transfected with siControl, a pool of siNRLP3 constructs or with individual siNLRP3 construct (05-08). Transfected cells were exposed to 5 μg/cm2 of Asb (for 48 hours) before RNA extraction. D: Western blot analysis of culture supernatant from LP9 cells transfected with siNLRP3(06) and scrambled control 48 hours after Asb exposure. FGF2, fibroblast growth factor 2; TFPI2, tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2.

We also used four single siNLRP3 constructs [siNLRP3(05-08)], and siNLRP3(06) produced the most remarkable effect on NLRP3 mRNA levels (Figure 3C). Of the 4 constructs, only siNLRP3(06) had an appreciable effect on attenuation of IL-6 and IL-8 levels. TFPI2 and FGF2 levels were only slightly decreased in response to asbestos exposure in cells transfected with siNLRP3(06) (Figure 3D) compared with controls. The effect with the pool of 4 siNLRP3 was certainly more remarkable than single siNLRP3, suggesting that the use of pool of siRNA may be a more effective approach.

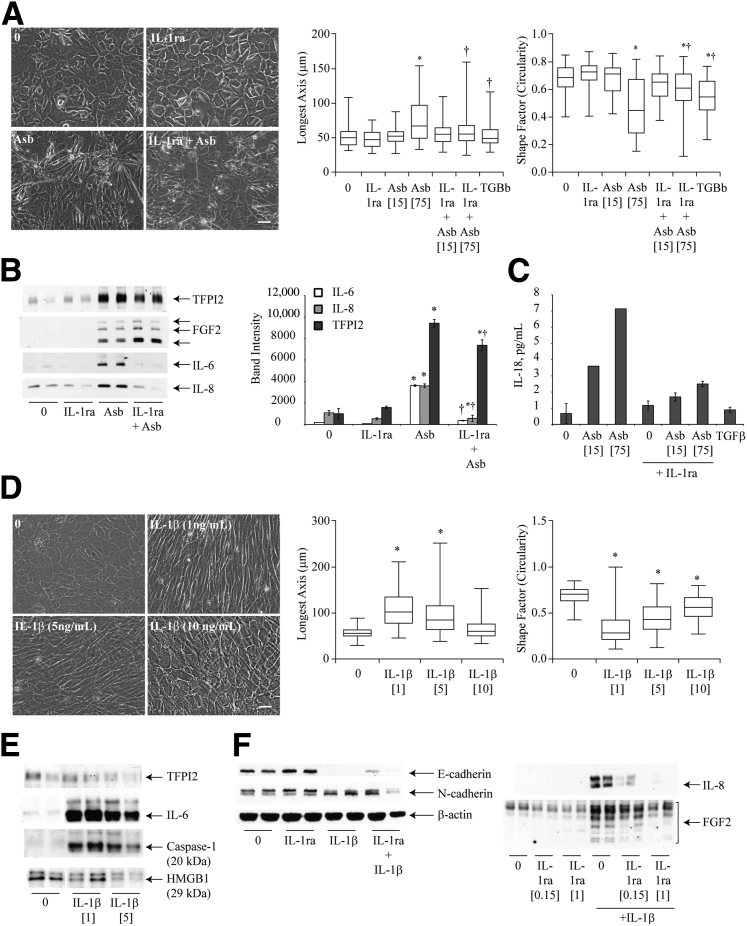

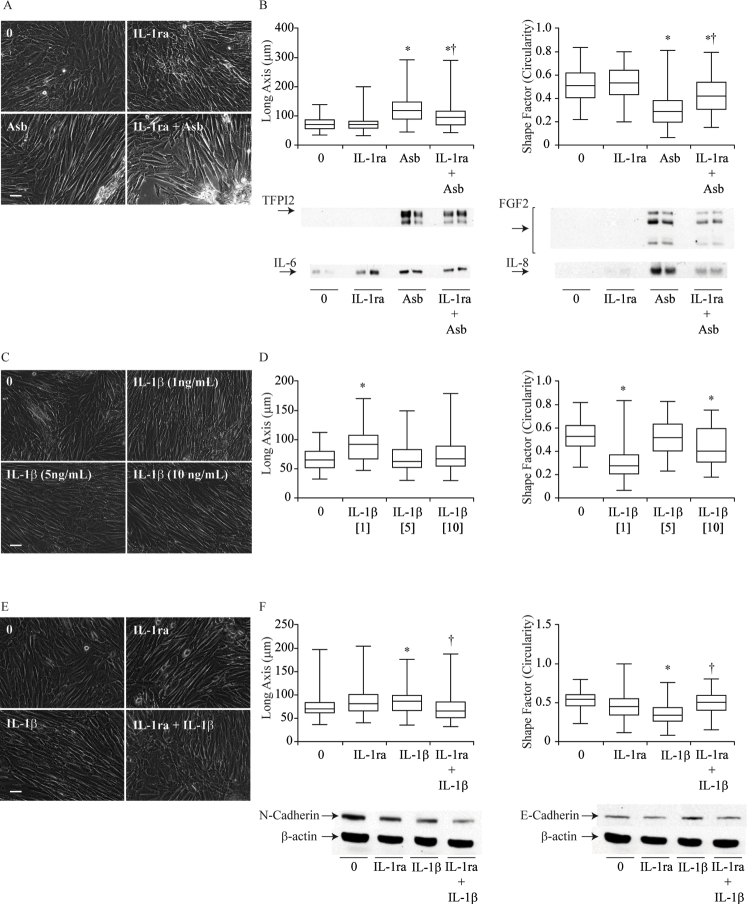

IL-1β Signaling Regulates Asbestos-Induced MFT

Because asbestos activates the NLRP3 inflammasome with a concomitant release of IL-1β in HMCs,6 the next step was to investigate the role of this cytokine in asbestos-induced MFT. Pretreatment of HMCs (HPM3 and LP9) with the IL-1 receptor antagonist, IL-1Ra (150 ng/mL), before asbestos exposure resulted in a delay in the morphologic transition of HPM3 cells to a more fibroblastic appearance (Figure 4A and Supplemental Figure S1A) (LP9 cells). Cells exposed to asbestos were generally more elongated and narrower in width than control cells (mean shape factor of approximately 0.4 and median length of approximately 60 μm), and blocking IL-1R delayed this process at 48 hours because fewer cells were long and narrow as determined using the morphometric analysis (Figure 4A). In addition, blocking of the IL-1 receptor resulted in a significant decrease in the levels of IL-6, IL-8, and TFPI2 while increasing the levels of FGF2 secreted in response to asbestos exposure (Figure 4B). Furthermore, pretreatment of cells with IL-1Ra also reduced levels of IL-18 in response to asbestos exposure (Figure 4C). In LP9 cells, pretreatment with IL-1Ra reduced IL-8 and FGF2 levels noticeably, whereas only slight reductions in IL-6 and TFPI2 were observed (Supplemental Figure S1B). To further confirm the role of IL-1β signaling in asbestos-induced MFT, HPM3 and LP9 cells were treated with two pulses of recombinant IL-1β (0.5, 1, 5, or 10 ng/mL). The greatest morphologic change was observed in the group exposed to 1 ng/mL of IL-1β (Figure 4D and Supplemental Figure S1, C and D); cells in this group were the most elongated and least circular (Figure 4D and Supplemental Figure S1D). The morphologic change observed with 0.5 ng/mL was no different from that observed with 1 ng but was inconsistent (data not shown). Western blot analysis of media supernatants from cells treated with two doses of IL-1β indicated that treatment with the lower dose of IL-1β (1 ng/mL) led to activation of caspase-1 as measured by levels of the p20 subunit of active Cas-1 in the supernatant. In addition, IL-6 levels were increased by treatment with the lower concentration of IL-1β but had a minimal effect on TFPI2 secretion. Unlike asbestos exposure, treatment with either concentration of IL-1β failed to increase levels of the danger-associated molecule HMGB1 (Figure 4E). The increase in IL-6, IL-8, and FGF2 induced by IL-1β was attenuated by pretreatment of HPM3 cells with IL-1Ra (150 ng/mL). However, this concentration of IL-1Ra failed to block the transition of HPM3 cells to a more fibroblastic phenotype in response to IL-1β (data not shown). IL-1β treatment also caused a decrease in E-cadherin, and on pretreatment of cells with a higher dose of IL-1Ra (1 μg/mL), a small increase in E-cadherin was observed (Figure 4F). FGF2 and IL-8 levels were drastically reduced by the 1-μg/mL dose as well (Figure 4F). The expected blockage of IL-1β-induced MFT was also observed morphologically in LP9 cells pretreated with IL-1Ra (Supplemental Figure S1, E and F), suggesting that the previous dose was too low to effectively block all the IL-1 receptors available. Unlike HPM3 cells, however, treatment of LP9 cells with IL-1β caused a slight increase in E-cadherin levels but no change in N-cadherin, whereas pretreatment with IL-1Ra restored E-cadherin levels and decreased N-cadherin levels slightly (Supplemental Figure S1F).

Figure 4.

IL-1β signaling regulates asbestos (Abs)–induced mesothelial to fibroblastic transition (MFT). A: Phase contrast micrograph of HPM3 cells pretreated with 150 ng/mL of IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) 1 hour before Asb exposure. Images were obtained at 48 hours after initial Asb pulse; morphologic changes were also quantified using MetaMorph image analysis software as described in Figure 1. B: Western blot analysis of cytokines [fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), IL-6, and IL-8] and tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 (TFPI2) levels in pooled culture supernatants 96 hours after initial Asb pulse and densitometric analysis of blots. C: IL-18 levels measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay 96 hours after first Asb pulse with and without IL-1Ra. D: Phase contrast micrographs of dose-dependent MFT in HPM3 cells exposed to IL-1β at indicated concentrations (imagedon Olympus IX70 inverted microscope) and morphometric analysis using the MetaMorph image analysis software as described in Figure 1. E: Western blot analysis of TFPI2, IL-6, Caspase-1 and HMGB1 levels 96 hours after HPM3 cells were treated with 1 or 5 ng/mL IL-1β. F: Western blot analysis of FGF2 and IL-8 levels in concentrated media supernatant and immunoblots of E-cadherin and N-cadherin expression in cell lysates from HPM3 cells pretreated with 150 ng/mL or 1 μg/mL of IL-1Ra with and without IL-1β (1 ng/mL) treatment (β-actin was used as a loading control for cell lysates). Numbers in brackets denote surface area concentrations of asbestos. ∗P < 0.05 versus control; †P < 0.05 versus asbestos alone. Scale bar = 50 μm. Images were obtained with a 20x objective (A and D).

Asbestos Exposure Causes MFT in Mice That Is Dependent on Inflammasome Activation

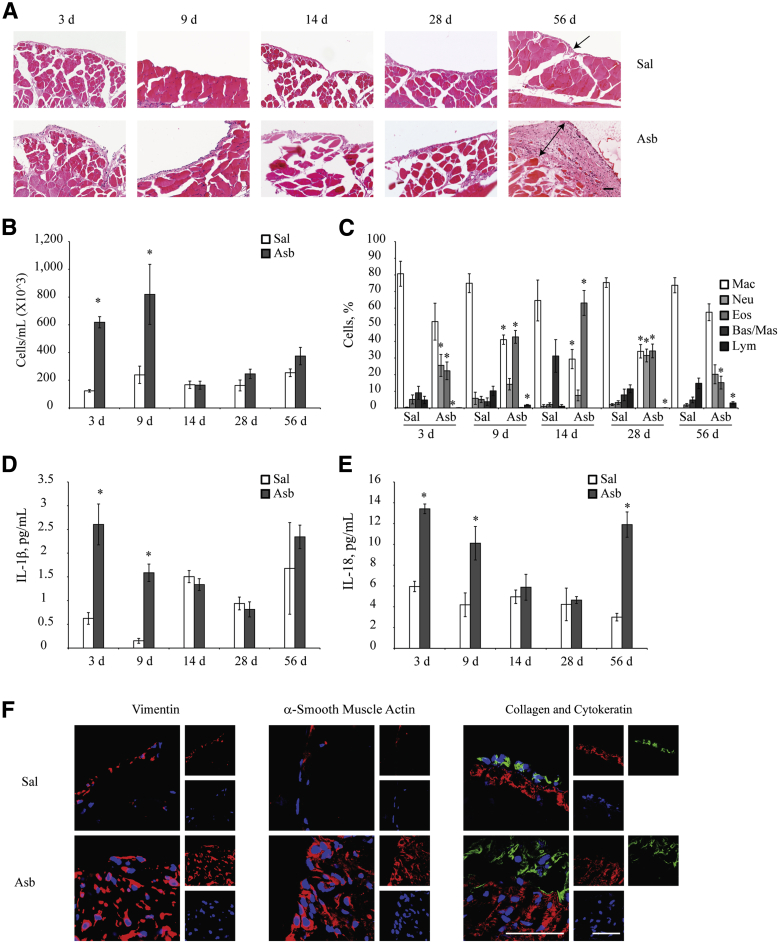

Having made these observations in vitro, in vivo asbestos exposure experiments were conducted to confirm whether asbestos had the same effect in C57BL/6 mice. Asbestos exposure caused a significant increase in the thickness of the peritoneal submesothelium when compared with controls at 8 weeks (Figure 5A). Glass beads (which are nonfibrous silicates) were used as a negative control. For asbestos exposed samples, five random fields spanning the thickened sections of the peritoneal walls were imaged. Five random fields of control samples were also imaged to ensure there was no bias in variation of submesothelium thickness within and between samples. An increase in total number of cells infiltrating the peritoneal cavity was observed at early time points in the PLF with a peak on day 9 (Figure 5B). The neutrophil numbers, however, decreased after day 3 and peaked again on day 28 (Figure 5C). IL-1β and IL-18 levels peaked on day 3 and progressively declined during the experiment but increased again after 8 weeks (Figure 5, D and E). Immunohistochemical analysis of the peritoneal wall cross sections for the expression levels of vimentin, α-SMA, Col1α1, and cytokeratin 18 revealed increases in expression levels of these proteins after asbestos exposure (Figure 5F). Chrysotile asbestos also caused significant thickness of the peritoneal wall, whereas glass beads did not cause thickness, but occasional sites of glass beads surrounded by inflammatory cells were observed.

Figure 5.

Asbestos (Asb) exposure induces mesothelial to fibroblastic transition in the parietal peritoneal mesothelium in vivo. A: Wild-type C57/BL6 mice were exposed to 500 μL of 200 μg/mL of Asb in saline (Sal) or Sal alone for 3, 7, 14, 28, or 56 days (8 weeks). Cross sections of peritoneal walls were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histologic analysis of the submesothelial layer. Peritoneal wall sections were imaged on the Olympus BX50 inverted microscope. Single cell layer of parietal mesothelium (arrow) and thickened peritoneal wall after Asb exposure (double-headed arrow) are shown. B and C: Total (B) and differential (C) cell counts in peritoneal lavage fluid (PLF) showing the relative proportions of immune cells infiltrating the peritoneal cavity in response to Asb exposure at 3, 9, and 14 days and 4 and 8 weeks. D and E: IL-1β (D) and IL-18 (E) levels in the PLF of Asb-exposed mice during the study as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Cytokine levels are reported in picograms per milliliter of PLF collected. F: Peritoneal wall sections from animals exposed to Asb for 8 weeks were immunofluorescently stained to ascertain levels of cytokeratin (green), vimentin, collagen (red), and α-smooth muscle actin after Asb exposure [nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue)]. Smaller panels to the right are individual fluorescent channels. Sections were imaged on the Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal laser scanning microscope. ∗P < 0.05 versus saline controls. Scale bars = 50 μm (A and F). Original magnification: ×20 (A); ×100 (F). Bas, basophils; Eos, eosinophils; Lym, lymphocytes; Mac, macrophages; Mas, mast cells; Neu, neutrophils.

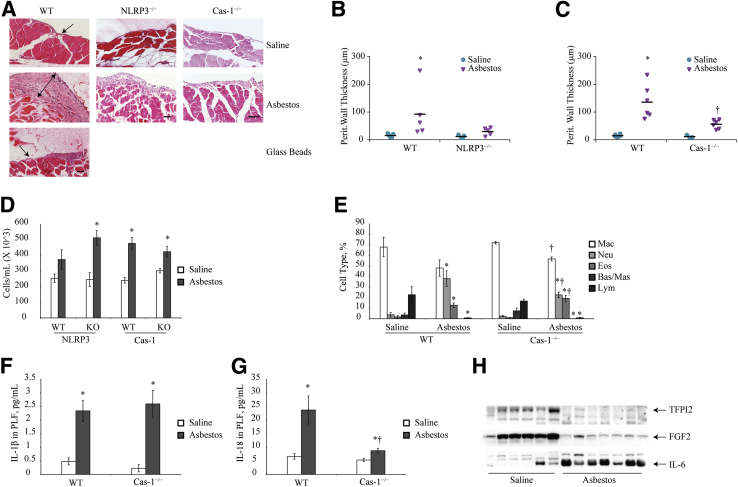

Asbestos-Induced Thickening of the Peritoneal Wall Is Caspase-1 Dependent

The peritoneal walls of inflammasome component knockout mice (NLRP3−/−, ASC−/−, and Cas-1−/−) were assessed for asbestos-induced thickening of the submesothelium after hematoxylin and eosin staining as described above. NLRP3−/− mice had decreased thickening of their peritoneal walls when compared with their wild-type counterparts; however, this finding was not significant. On the other hand, Cas-1−/− mice exposed to asbestos had significantly less thickening in the submesothelium (Figure 6, A–C). Glass beads, which were used as a particulate negative control, did not cause thickening of the submesothelium (Figure 6A). No significant difference in thickening was observed with ASC−/− mice (data not shown). No significant changes were observed in total cell counts (Figure 6D), but infiltrating neutrophil levels (Figure 6E) were lower in Cas-1−/− mice when compared with wild-type mice exposed to asbestos. Although IL-1β levels in the PLF of Cas-1−/− mice were not significantly different from that in wild-type mice (Figure 6F), a significant reduction in IL-18 levels was observed in Cas-1−/− after asbestos exposure (Figure 6G). In addition, the assessment of FGF2 and TFPI2 by Western blot analysis revealed a drastic reduction in the levels of these two proteins in response to asbestos exposure in the Cas-1−/− mice (Figure 6H). However, IL-6 levels were higher in exposed mice compared with their saline controls but were inconclusive (Figure 6H).

Figure 6.

Caspase-1 (Cas-1) is important for asbestos-induced mesothelium thickening in mice. A: Micrographs of peritoneal wall sections from C57/BL6 wild-type (WT) and nod-like receptor family member containing a pyrin domain 3 (NLRP3)−/− and Cas-1−/− mice after 8 weeks of asbestos exposure (100 μg weekly) stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histologic analysis. Glass beads at an equal surface area (538 μg weekly) were used as a negative control for particulate exposure. Single cell layer of parietal mesothelium (arrows) and thickened peritoneal wall after asbestos exposure (double-headed arrow) are shown. Images were obtained on Olympus BX50 microscope as described in Figure 5. B: and C: Graphic representation of peritoneal wall thickness in asbestos-exposed versus saline controls for WT and knockout (NLRP3−/− and Cas-1−/−) mice. D: Total cell counts per mL of peritoneal lavage fluid (PLF) retrieved from WT, NLRP3−/−, and Cas-1−/− saline- and asbestos-exposed mice. E: Differential cell counts of cells in PLF of Cas-1−/− and WT mice after 8 weeks of asbestos exposure. F and G: IL-1β (F) and IL-18 (G) levels in the PLF of WT and Cas-1−/− mice as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. H: Western blot analysis of tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 (TFPI2), fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), and IL-6 in saline and asbestos exposed Cas-1−/−-mice. ∗P ≤ 0.05 versus saline controls; †P ≤ 0.05 versus WT asbestos. Scale bars = 50 μm. Bas, basophils; Eos, eosinophils; Lym, lymphocytes; Mac, macrophages; Mas, mast cells; Neu, neutrophils.

Discussion

The mechanisms involved in asbestos-induced MM are less understood. Chronic inflammation is believed to play an important role in the etiology of this deadly disease.4, 22 Recently, we found that asbestos can prime and activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in mesothelial cells,6 resulting in the release of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18. IL-1β promotes EMT and cancer cell stemness in a number of cell types.8, 9 Cell type–specific studies on the importance of the inflammasome for cancers with an inflammatory signature have indicated that the inflammasome is a key player in the etiology of these cancers.24, 25, 26, 27 These studies, combined with our own observations, suggest that the inflammasome may be a key potentiator of asbestos-induced MFT and MM. We therefore hypothesized that activation of the inflammasome in response to asbestos exposure facilitates MFT, which may be the earliest event in the process of MM development. Transcript levels of the EMT-related genes from the PCR array revealed changes in expression in mesothelial cells that did not exactly mimic changes produced by TGF-β, the positive control (Table 1). These results suggested that asbestos-induced MFT occurred through pathways that may not be directly downstream of TGF-β (like BMP2) signaling but involved some of the same players. Although asbestos exposure led to a 12-fold decrease in snai1 mRNA levels during a 48-hour period in LP9/hTERT cells, increased protein levels of snai1 were observed at later time point in HPM3. These gene changes were accompanied by morphologic changes of mesothelial cells to a more fibroblastic type. The differences observed in the gene expression between the 2 cell types may be attributable to the differential susceptibility of the peritoneal and pleural mesothelial cells to asbestos-induced regulation of genes as observed in a recent next-generation sequencing study by our group.5 For in vivo studies, we selected a mouse model of asbestos exposure in which inflammation, fibrosis, and MM development has been found. In vivo studies of asbestos exposure also found that asbestos causes a significant increase in the thickness of the parietal peritoneal submesotheilium, which is accompanied by increased collagen deposition and increased vimentin and α-SMA expression in the same region. In addition, cytokeratin expression is maintained in the mesothelium with and without asbestos exposure, which suggests that the cells in the submesothelium are mesothelial in origin. A study of the changes observed in the peritoneal wall of patients with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis also revealed changes in the submesothelium28 that were similar to those observed in the peritoneal walls of mice exposed to asbestos.

We are the first to report that asbestos exposure up-regulates FGF2 and TFPI2 secretion both in vitro and in vivo and may play an important role in the transition from mesothelial to fibroblastic or myofibroblastic phenotype. Support of our findings is derived from other reports that FGF2 in concert with IL-1β promotes EMT in corneal endothelial cells,9 whereas FGF2 alone is capable of inducing EMT in Hertwig epithelial root sheath cells during cementum formation in tooth development.29 Another report found that MCF-7 cells undergoing EMT up-regulate TFPI2 gene expression in excess of 300-fold,30 which corroborates our findings. TFPI2 inhibits fibrinolysis, an important function of the mesothelium that prevents adhesion of organs.31 Fibrin promotes EMT in a study in which mesothelial cells in culture were overlaid with fibrin, resulting in a fibroblastic transition of the mesothelial cells.32 Consequently, overexpression of this protein in response to asbestos exposure could lead to fibrin deposition, thereby facilitating the MFT observed in our study. Further studies are under way to determine the exact role these proteins play and the mechanisms they use in asbestos-induced MFT. Because asbestos exposure also induces the secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 under both in vitro and in vivo conditions by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome6 or by other mechanisms, it is likely that the phenomenon of MFT observed in response to extended asbestos exposure is due to IL-1β signaling. This was confirmed by using IL-1Ra before asbestos exposure, which delayed the onset of MFT compared with cells exposed to asbestos alone. However, there was a greater loss of cells after transitioning into a fibroblastic phenotype in IL-1Ra pretreated cells, suggesting that IL-1β acts as a prosurvival signal caused by asbestos exposure and may be considered as an early asbestos-exposure biomarker for asbestos-related diseases. Secretion of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-8 and IL-6 (both implicated in fibrogenesis) in response to asbestos was significantly reduced by the blockade of the IL-1 receptor, suggesting that they are directly or indirectly regulated by IL-1β signaling. Secretion of TFPI2 was also decreased by blockade of IL-1R, which may be an indirect response caused by the reduction in IL-6 signaling. IL-6 signaling regulates the expression of TFPI233; thus, a decrease in IL-6 levels would explain the decrease in TFPI2 levels in the presence of IL-1Ra after asbestos exposure. Unlike the other cytokines, FGF2, which is secreted in a nonclassic secretion pathway dependent on caspase-1, was up-regulated in response to asbestos after pretreatment with IL-1Ra. Because FGF2 can initiate EMT in corneal endothelial cells and Hertwig epithelial root sheath cells cells,9, 29 it may explain why the mesothelial cells eventually undergo MFT after the delay imposed by the antagonist. It is a possibility that FGF2 and IL-1β play pivotal roles in asbestos-induced MFT. In fact, IL-1β induces FGF2 secretion in HMCs and corneal endothelial cells.34, 35 The dose of IL-Ra used in these experiments can be said to be the limiting factor because the use of an approximately sevenfold higher concentration (1 μg/mL) led to a complete blockage of MFT with a slight reduction in FGF2 secretion (greatest reduction was observed in the lower-molecular-weight isoforms). Because cells were only exposed to IL-1Ra at this dose for 72 hours with and without asbestos exposure, further studies are needed to ascertain the exact mechanism by which IL-1β initiates or induces MFT in mesothelial cells. The role of IL-1β in asbestos-induced MFT was further confirmed by recombinant IL-1β. A low concentration of IL-1β (1 ng/mL) caused MFT, whereas high concentrations were ineffective. This observation and other published reports36 support our finding that low concentrations of IL-1β secreted in response to asbestos exposure is enough to cause MFT, maybe in association with other molecules.

Because IL-1β can be secreted in response to noncanonical inflammasome activation and other sources, including caspase-8 activation,37 there was a need to confirm that the asbestos-induced MFT observed was indeed dependent on regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. To investigate this, NLRP3 was knocked down in LP9/hTERT cells by siNLRP3. Exposure of these NLRP3 inhibited cells to asbestos resulted in a reduction in TFPI2, IL-6, and FGF2 secretion in the culture supernatant and a partial rescue of the loss of E-cadherin expression compared with control cells exposed to asbestos. NLRP3 and ASC have been reported to promote EMT independently of their inflammasome functions10; thus, ASC may play a similar role in our system, accounting for the incomplete rescue of E-cadherin expression in response to asbestos after NLRP3 knockdown. Because these experiments reveal a partial role of NLRP3 in asbestos-induced MFT, a stably NLRP3 inhibited cell line or recently discovered inhibitors38, 39 are required to confirm these effects.

To confirm the role of inflammasomes in MFT in an in vivo model, we used inflammasome component knockout mice. Although ASC and NLRP3 knockout mice did not have any significant difference in asbestos-induced peritoneal wall thickening compared with their wild-type counterparts, caspase-1 knockout mice had significantly attenuated submesothelial thickening after 8 weeks of asbestos exposure when compared with their saline counterparts and wild-type controls. This finding implies that caspase-1 is required for asbestos-induced thickening of the parietal mesothelium. Caspases, including caspase-1, are involved in injury, remodeling, and fibrosis in various models40, 41, 42, 43, 44; however, we are the first to report the involvement of caspase-1 in asbestos-induced MFT. Caspase-1 deficiency caused diminished levels of asbestos-induced IL-18 in the PLF; however, IL-1β levels were not affected. Because IL-1β can be derived from sources45 other than inflammasome, it is not a surprising observation. In addition, IL-1β regulates its own function by regulating IL-1Ra levels. Our microarray data indicate that asbestos inhalation results in fourfold increased IL-1Ra mRNA levels in lungs at 9 days (A.S., unpublished data). The initial increase, followed by the decline and then recovery of IL-1β levels, in our in vivo model could be explained by the regulation of IL-1β by IL-1Ra. To understand the role of IL-1β in MFT, currently we are using Anakinra and a specific NLRP3 inhibitor and plan to use IL-1R knockout mice in future. Furthermore, assessment of IL-1Ra and IL-1R expression is also under way because these IL receptors can play important roles in IL-1β biology. NLRP3 inflammasome is also involved in the process of fibrosis in various models.46, 47, 48, 49 In support of our observations, a Finnish study has recently identified a polymorphism in NLRP3 with increased risk of asbestos-related interstitial lung fibrosis and a CARD8 polymorphism associated with development or calcification of pleural thickening.50 These single-nucleotide polymorphisms have been linked to enhanced IL-1β production and severe inflammation. No significant effect seen in our NLRP3 knockout model could be attributed to global knockdown of the NLRP3 gene. As has been reported earlier,51, 52 NLRP3/ASC deletion from different cell types could have different consequence. To pinpoint the role of mesothelial cell NLRP3/ASC in asbestos-induced MFT, mesothelial cell specific targeted knockdown is required.

Taken together, our data suggest that asbestos-induced MFT in mesothelial cells is regulated in part by the inflammasome via IL-1β/IL-18 in conjunction with TFPI2 and FGF2. Further studies are needed to dissect the roles played by the different proteins involved, which will help provide a basis for determining the mechanism and identifying biomarkers by which asbestos promotes cell survival that can lead to the development of malignant neoplasms, such as MM.

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of Vermont Cancer Center Advanced Genome Technologies Core and Microscopy and Imaging Core for assistance in processing and analyzing samples.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grant R01 ES021110 (A.S.) and Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Student Fellowship (J.K.T.).

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.11.008.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure S1.

Regulation of asbestos-induced mesothelial to fibroblastic transition (MFT) by IL-1β signaling in LP9 cells. A: Phase contrast micrograph of LP9 cells pretreated with 1 μg/mL of IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) 1 hour before asbestos exposure (1 μg/cm2). Images were obtained at 9 days after initial asbestos pulse. B: Morphologic changes were also quantified using MetaMorph image analysis software version 7.8.9.0 as described in Figure 1 and Western blot analysis of tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 (TFPI2), IL-6, fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), and IL-8 in concentrated culture supernatant 96 hours after asbestos exposure (48 hours after second pulse). C: Phase contrast micrographs of dose-dependent MFT in LP9 cells exposed to IL-1β at indicated concentrations (imaged on Olympus IX70 inverted microscope. D: Morphometric analysis using the MetaMorph image analysis software as described in Figure 1. E: Phase contrast micrographs of LP9 cells on day 7 pretreated with two pulses of 1 μg/mL of IL-1Ra 1 hour before each treatment with IL-1β (1 ng/mL). F: Morphometric analysis using the MetaMorph image analysis software as described in Figure 1 and immunoblots of E-cadherin and N-cadherin expression in cell lysates from LP9 cells pretreated with 1 μg/mL of IL-1Ra with and without IL-1β (1 ng/mL) treatment (β-actin was used as a loading control for cell lysates). ∗P < 0.05 versus control; †P < 0.05 versus asbestos alone or IL-1β. Scale bars = 50 μm (A, B, and E). Images obtained with a 20x objective (A, C, and E).

References

- 1.Wagner J.C., Sleggs C.A., Marchand P. Diffuse pleural mesothelioma and asbestos exposure in the North Western Cape Province. Br J Ind Med. 1960;17:260–271. doi: 10.1136/oem.17.4.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson J.K., Westbom C.M., Shukla A. Malignant mesothelioma: development to therapy. J Cell Biochem. 2014;115:1–7. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinato D.J., Mauri F.A., Ramakrishnan R., Wahab L., Lloyd T., Sharma R. Inflammation-based prognostic indices in malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:587–594. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31823f45c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsuzaki H., Maeda M., Lee S., Nishimura Y., Kumagai-Takei N., Hayashi H., Yamamoto S., Hatayama T., Kojima Y., Tabata R., Kishimoto T., Hiratsuka J., Otsuki T. Asbestos-induced cellular and molecular alteration of immunocompetent cells and their relationship with chronic inflammation and carcinogenesis. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:492608. doi: 10.1155/2012/492608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dragon J., Thompson J., MacPherson M., Shukla A. Differential susceptibility of human pleural and peritoneal mesothelial cells to asbestos exposure. J Cell Biochem. 2015;116:1540–1552. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hillegass J.M., Miller J.M., MacPherson M.B., Westbom C.M., Sayan M., Thompson J.K., Macura S.L., Perkins T.N., Beuschel S.L., Alexeeva V., Pass H.I., Steele C., Mossman B.T., Shukla A. Asbestos and erionite prime and activate the NLRP3 inflammasome that stimulates autocrine cytokine release in human mesothelial cells. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2013;10:39. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-10-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolb M., Margetts P.J., Anthony D.C., Pitossi F., Gauldie J. Transient expression of IL-1beta induces acute lung injury and chronic repair leading to pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1529–1536. doi: 10.1172/JCI12568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y., Wang L., Pappan L., Galliher-Beckley A., Shi J. IL-1beta promotes stemness and invasiveness of colon cancer cells through Zeb1 activation. Mol Cancer. 2012;11:87. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-11-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J.G., Ko M.K., Kay E.P. Endothelial mesenchymal transformation mediated by IL-1beta-induced FGF-2 in corneal endothelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2012;95:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang W., Wang X., Chun J., Vilaysane A., Clark S., French G., Bracey N.A., Trpkov K., Bonni S., Duff H.J., Beck P.L., Muruve D.A. Inflammasome-independent NLRP3 augments TGF-beta signaling in kidney epithelium. J Immunol. 2013;190:1239–1249. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.BeruBe K.A., Quinlan T.R., Fung H., Magae J., Vacek P., Taatjes D.J., Mossman B.T. Apoptosis is observed in mesothelial cells after exposure to crocidolite asbestos. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;15:141–147. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.1.8679218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shukla A., MacPherson M.B., Hillegass J., Ramos-Nino M.E., Alexeeva V., Vacek P.M., Bond J.P., Pass H.I., Steele C., Mossman B.T. Alterations in gene expression in human mesothelial cells correlate with mineral pathogenicity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:114–123. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0146OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller J.M., Thompson J.K., MacPherson M.B., Beuschel S.L., Westbom C.M., Sayan M., Shukla A. Curcumin: a double hit on malignant mesothelioma. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2014;7:330–340. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson J.K., Westbom C.M., MacPherson M.B., Mossman B.T., Heintz N.H., Spiess P., Shukla A. Asbestos modulates thioredoxin-thioredoxin interacting protein interaction to regulate inflammasome activation. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2014;11:24. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-11-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Westbom C., Thompson J.K., Leggett A., MacPherson M., Beuschel S., Pass H., Vacek P., Shukla A. Inflammasome modulation by chemotherapeutics in malignant mesothelioma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodglick L.A., Vaslet C.A., Messier N.J., Kane A.B. Growth factor responses and protooncogene expression of murine mesothelial cell lines derived from asbestos-induced mesotheliomas. Toxicol Pathol. 1997;25:565–573. doi: 10.1177/019262339702500605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrick S.E., Mutsaers S.E. The potential of mesothelial cells in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications. Int J Artif Organs. 2007;30:527–540. doi: 10.1177/039139880703000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu J., Kadariya Y., Cheung M., Pei J., Talarchek J., Sementino E., Tan Y., Menges C.W., Cai K.Q., Litwin S., Peng H., Karar J., Rauscher F.J., Testa J.R. Germline mutation of Bap1 accelerates development of asbestos-induced malignant mesothelioma. Cancer Res. 2014;74:4388–4397. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owens S., Jeffers A., Boren J., Tsukasaki Y., Koenig K., Ikebe M., Idell S., Tucker T.A. Mesomesenchymal transition of pleural mesothelial cells is PI3K and NF-kappaB dependent. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;308:L1265–L1273. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00396.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuida K., Lippke J.A., Ku G., Harding M.W., Livingston D.J., Su M.S., Flavell R.A. Altered cytokine export and apoptosis in mice deficient in interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Science. 1995;267:2000–2003. doi: 10.1126/science.7535475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donaldson K., Murphy F.A., Duffin R., Poland C.A. Asbestos, carbon nanotubes and the pleural mesothelium: a review of the hypothesis regarding the role of long fibre retention in the parietal pleura, inflammation and mesothelioma. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2010;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hillegass J.M., Shukla A., Lathrop S.A., MacPherson M.B., Beuschel S.L., Butnor K.J., Testa J.R., Pass H.I., Carbone M., Steele C., Mossman B.T. Inflammation precedes the development of human malignant mesotheliomas in a SCID mouse xenograft model. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1203:7–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buder-Hoffmann S.A., Shukla A., Barrett T.F., MacPherson M.B., Lounsbury K.M., Mossman B.T. A protein kinase Cdelta-dependent protein kinase D pathway modulates ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 phosphorylation and Bim-associated apoptosis by asbestos. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:449–459. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaki M.H., Lamkanfi M., Kanneganti T.D. The Nlrp3 inflammasome: contributions to intestinal homeostasis. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chow M.T., Tschopp J., Moller A., Smyth M.J. NLRP3 promotes inflammation-induced skin cancer but is dispensable for asbestos-induced mesothelioma. Immunol Cell Biol. 2012;90:983–986. doi: 10.1038/icb.2012.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drexler S.K., Bonsignore L., Masin M., Tardivel A., Jackstadt R., Hermeking H., Schneider P., Gross O., Tschopp J., Yazdi A.S. Tissue-specific opposing functions of the inflammasome adaptor ASC in the regulation of epithelial skin carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18384–18389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209171109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams T.M., Leeth R.A., Rothschild D.E., Coutermarsh-Ott S.L., McDaniel D.K., Simmons A.E., Heid B., Cecere T.E., Allen I.C. The NLRP1 inflammasome attenuates colitis and colitis-associated tumorigenesis. J Immunol. 2015;194:3369–3380. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yanez-Mo M., Lara-Pezzi E., Selgas R., Ramirez-Huesca M., Dominguez-Jimenez C., Jimenez-Heffernan J.A., Aguilera A., Sanchez-Tomero J.A., Bajo M.A., Alvarez V., Castro M.A., del Peso G., Cirujeda A., Gamallo C., Sanchez-Madrid F., Lopez-Cabrera M. Peritoneal dialysis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of mesothelial cells. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:403–413. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J., Chen G., Yan Z., Guo Y., Yu M., Feng L., Jiang Z., Guo W., Tian W. TGF-beta1 and FGF2 stimulate the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of HERS cells through a MEK-dependent mechanism. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229:1647–1659. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foroni L., Vasuri F., Valente S., Gualandi C., Focarete M.L., Caprara G., Scandola M., D'Errico-Grigioni A., Pasquinelli G. The role of 3D microenvironmental organization in MCF-7 epithelial-mesenchymal transition after 7 culture days. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:1515–1522. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mutsaers S.E. Mesothelial cells: their structure, function and role in serosal repair. Respirology. 2002;7:171–191. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2002.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang C.C., Huang J.W., Shyu R.S., Yen C.J., Shiao C.H., Chiang C.K., Hu R.H., Tsai T.J. Fibrin-Induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of peritoneal mesothelial cells as a mechanism of peritoneal fibrosis: effects of pentoxifylline. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khouri C., Dittrich A., Sackett S.D., Denecke B., Trautwein C., Schaper F. Glucagon counteracts interleukin-6-dependent gene expression by redundant action of Epac and PKA. Biol Chem. 2011;392:1123–1134. doi: 10.1515/BC.2011.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee J.G., Heur M. Interleukin-1beta enhances cell migration through AP-1 and NF-kappaB pathway-dependent FGF2 expression in human corneal endothelial cells. Biol Cell. 2013;105:175–189. doi: 10.1111/boc.201200077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cronauer M.V., Stadlmann S., Klocker H., Abendstein B., Eder I.E., Rogatsch H., Zeimet A.G., Marth C., Offner F.A. Basic fibroblast growth factor synthesis by human peritoneal mesothelial cells: induction by interleukin-1. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1977–1984. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65516-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee J.K., Kim S.H., Lewis E.C., Azam T., Reznikov L.L., Dinarello C.A. Differences in signaling pathways by IL-1beta and IL-18. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8815–8820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402800101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monie T.P., Bryant C.E. Caspase-8 functions as a key mediator of inflammation and pro-IL-1beta processing via both canonical and non-canonical pathways. Immunol Rev. 2015;265:181–193. doi: 10.1111/imr.12284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coll R.C., Robertson A.A., Chae J.J., Higgins S.C., Munoz-Planillo R., Inserra M.C., Vetter I., Dungan L.S., Monks B.G., Stutz A., Croker D.E., Butler M.S., Haneklaus M., Sutton C.E., Nunez G., Latz E., Kastner D.L., Mills K.H., Masters S.L., Schroder K., Cooper M.A., O'Neill L.A. A small-molecule inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Nat Med. 2015;21:248–255. doi: 10.1038/nm.3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Youm Y.H., Nguyen K.Y., Grant R.W., Goldberg E.L., Bodogai M., Kim D., D'Agostino D., Planavsky N., Lupfer C., Kanneganti T.D., Kang S., Horvath T.L., Fahmy T.M., Crawford P.A., Biragyn A., Alnemri E., Dixit V.D. The ketone metabolite beta-hydroxybutyrate blocks NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammatory disease. Nat Med. 2015;21:263–269. doi: 10.1038/nm.3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inoue T., Kusano T., Tomori K., Nakamoto H., Suzuki H., Okada H. Effects of cell-type-specific expression of a pan-caspase inhibitor on renal fibrogenesis. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2015;19:350–358. doi: 10.1007/s10157-014-1011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Artlett C.M. The role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in fibrosis. Open Rheumatol J. 2012;6:80–86. doi: 10.2174/1874312901206010080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuwano K., Kunitake R., Maeyama T., Hagimoto N., Kawasaki M., Matsuba T., Yoshimi M., Inoshima I., Yoshida K., Hara N. Attenuation of bleomycin-induced pneumopathy in mice by a caspase inhibitor. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L316–L325. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.2.L316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang X.H., Zhu R.M., Xu W.A., Wan H.J., Lu H. Therapeutic effects of caspase-1 inhibitors on acute lung injury in experimental severe acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:623–627. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i4.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winkler S., Rosen-Wolff A. Caspase-1: an integral regulator of innate immunity. Semin Immunopathol. 2015;37:419–427. doi: 10.1007/s00281-015-0494-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Antonopoulos C., Russo H.M., El Sanadi C., Martin B.N., Li X., Kaiser W.J., Mocarski E.S., Dubyak G.R. Caspase-8 as an Effector and Regulator of NLRP3 Inflammasome Signaling. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:20167–20184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.652321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lorenz G., Darisipudi M.N., Anders H.J. Canonical and non-canonical effects of the NLRP3 inflammasome in kidney inflammation and fibrosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29:41–48. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun B., Wang X., Ji Z., Wang M., Liao Y.P., Chang C.H., Li R., Zhang H., Nel A.E., Xia T. NADPH oxidase-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation and its important role in lung fibrosis by multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Small. 2015;11:2087–2097. doi: 10.1002/smll.201402859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ouyang X., Ghani A., Mehal W.Z. Inflammasome biology in fibrogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:979–988. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rastrick J., Birrell M. The role of the inflammasome in fibrotic respiratory diseases. Minerva Med. 2014;105:9–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kukkonen M.K., Vehmas T., Piirila P., Hirvonen A. Genes involved in innate immunity associated with asbestos-related fibrotic changes. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71:48–54. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2013-101555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allen I.C., TeKippe E.M., Woodford R.M., Uronis J.M., Holl E.K., Rogers A.B., Herfarth H.H., Jobin C., Ting J.P. The NLRP3 inflammasome functions as a negative regulator of tumorigenesis during colitis-associated cancer. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1045–1056. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zaki M.H., Vogel P., Malireddi R.K., Body-Malapel M., Anand P.K., Bertin J., Green D.R., Lamkanfi M., Kanneganti T.D. The NOD-like receptor NLRP12 attenuates colon inflammation and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:649–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.