Abstract

Traumatic optic neuropathy (TON) is an acute injury of the optic nerve secondary to trauma. Loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) is a key pathological process in TON, yet mechanisms responsible for RGC death remain unclear. In a mouse model of TON, real-time noninvasive imaging revealed a dramatic increase in leukocyte rolling and adhesion in veins near the optic nerve (ON) head at 9 hours after ON injury. Although RGC dysfunction and loss were not detected at 24 hours after injury, massive leukocyte infiltration was observed in the superficial retina. These cells were identified as T cells, microglia/monocytes, and neutrophils but not B cells. CXCL10 is a chemokine that recruits leukocytes after binding to its receptor C-X-C chemokine receptor (CXCR) 3. The levels of CXCL10 and CXCR3 were markedly elevated in TON, and up-regulation of CXCL10 was mediated by STAT1/3. Deleting CXCR3 in leukocytes significantly reduced leukocyte recruitment, and prevented RGC death at 7 days after ON injury. Treatment with CXCR3 antagonist attenuated TON-induced RGC dysfunction and cell loss. In vitro co-culture of primary RGCs with leukocytes resulted in increased RGC apoptosis, which was exaggerated in the presence of CXCL10. These results indicate that leukocyte recruitment in retinal vessels near the ON head is an early event in TON and the CXCL10/CXCR3 axis has a critical role in recruiting leukocytes and inducing RGC death.

Traumatic optic neuropathy (TON) is an acute injury of the optic nerve secondary to trauma. It is usually caused by motor vehicle and bicycle accidents, falls, assaults, war, and natural disaster.1 Directly or indirectly injured optic nerve causes immediate shearing and secondary swelling in a proportion of retinal ganglion cell (RGC) axons, followed by cell death, which results in irreversible visual loss.2, 3, 4 To date, there is no proven effective therapy to treat TON, and mechanisms of RGC death after acute optic nerve injury remain largely unclear.4

Inflammation is the body's defense system against infection, injury, and stress and is a critical component of wound healing.5 Circulating blood leukocytes that migrate to sites of tissue injury and infection are the key players in inflammation by eliminating the primary inflammatory trigger and contributing to tissue repair.6 Nevertheless, it has been well established that excessive or uncontrolled inflammation can cause enhanced tissue injury and diseases by the following mechanisms: receptor-induced activation of programed cell death processes, the clogging and rupture of blood and lymphatic vessels, and/or production of toxic molecules, such as reactive oxygen species.7 Inflammation is implicated in TON given that the levels of inflammatory molecules, including tumor necrosis factor-α and inducible nitric oxide synthase, are increased, inflammatory signaling pathways are activated, inflammatory cells (microglia/macrophage) are recruited to the site of axonal injury, and blocking tumor necrosis factor-α signaling substantially reduces RGC death in a mouse model of TON.8, 9, 10 However, the temporal and spatial dynamics of leukocyte recruitment in the retina, the key mediators that control leukocyte recruitment, and the contribution of leukocytes to RGC injury are yet to be defined.

Chemokines are a family of 8- to 15-kD proinflammatory peptides that are produced locally in tissues and guide leukocyte recruitment during inflammation.11 C-X-C chemokine receptor (CXCR) 3, on binding to its specific ligands CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, plays a critical role in inflammatory reactions by mediating the recruitment of activated T cells, monocytes, and macrophages.12, 13, 14, 15, 16 This pathway has been shown to be involved in many neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer disease, multiple sclerosis, and high intraocular pressure–induced retinal neuronal injury.17, 18, 19, 20, 21 Specific roles of the CXCR3 pathway in TON are yet unknown. In this study, we investigated leukocyte trafficking in the retina using noninvasive imaging and histological and flow cytometric analyses, and determined the role of the CXCL10/CXCR3 axis in TON using a mouse model of optic nerve crush (ONC).

Materials and Methods

Animals

The experimental procedures and use of animals were performed in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, and all protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Medical Branch. Male wild-type (WT), CXCR3-deficient mice (CXCR3−/−), and green fluorescence protein (GFP) transgenic mice (WT-GFP+) on the background of C57BL/6J were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). CXCR3−/−-GFP+ mice were generated by crossing CXCR3−/− and WT-GFP+ mice. Genotyping of CXCR3−/− mice was performed using DNA from tails, according to the protocol provided by the Jackson Laboratory. The following primers were used: moIMR0003, 5′-GGGCCAGCTCATTCCTCCCACTCAT-3′ (forward); oIMR4281, 5′-CCACAGGATTTCAGCCTGAACTTTG-3′ (forward); and oIMR4282, 5′-CGTGCACTATGCTCAGATATCTGTC-3′ (reverse). PCR products were 337 bp (WT) and 488 bp (CXCR3−/−) (Supplemental Figure S1A). The presence of GFP in mice was confirmed by illuminating the mouse tails with a Z-Bolt LED laser pointer (450 nm) from Beam of Light Technologies, Inc. (Happy Valley, OR). Tails from WT mice only showed dim blue light, whereas tails from GFP+ mice showed strong green fluorescence (Supplemental Figure S1B). All animals were maintained on a 12:12 light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum.

Induction of TON

ONC is an established method for generating the model of TON. Mice (between 8 and 12 weeks old) were anesthetized by i.p. injection of a mixture of ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg) and xylazine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg). For local anesthesia, 0.5% proparacaine was applied to the eye before the procedure. After a small incision was made by cutting conjunctiva around the eye globe, the right optic nerve close to its origin in the optic disk was crushed for 10 seconds using forceps (Dumont RS5005; Roboz, Gaithersburg, MD) and the left one without crushing served as control.22 Eyes and retinas were collected from 1 hour to 7 days after ONC procedure for further analysis.

Generation of Chimeric Mice

Bone marrow chimeric mice were generated as described previously.23 In brief, 6-week-old WT recipient mice received a single whole body dose of 950 cGy of cesium-137 γ-rays. A lead shield was used to protect the head and eyes from radiation. Next day, donor mice, including WT, CXCR3−/−, WT-GFP+, and CXCR3−/−-GFP+ were euthanized, and bone marrow cells were harvested from femur and tibia and suspended in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline without Ca2+/Mg2+ to a final concentration of 12 × 107 cells/mL. Recipient mice were restrained using an animal holder, and 0.2 mL of bone marrow cell suspension was injected through the tail vein using a 26-gauge needle. At 4 weeks after bone marrow cell transfer, mice were subjected to ONC injury.

Retinal Imaging Using Confocal SLO

After ONC injury, mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection of a mixture of ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg) and xylazine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg) at the indicated time points, and their pupils were dilated with tropicamide (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX) and phenylephrine (Alcon). Mice were properly located on the platform, and all images were acquired in the high-resolution mode (512 × 512 pixels) over a 30 × 30-degree field of view with the Heidelberg Spectralis HRA system (Heidelberg Engineering, Franklin, MA). The 488-nm laser was used for the excitation of green fluorescence, and a barrier filter at 500 nm was used to remove the reflected light with unchanged wavelength while allowing the collection of only the light emitted.24 The leukocyte area of each scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (SLO) image was measured by ImageJ software version 1.48 (NIH, Bethesda, MD; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij) using Analyze Particles after setting a color threshold that marks leukocytes clearly and excluding any artifacts. Then, leukocyte area was normalized to total image area.

AMG487 Treatment

AMG487 (TOCRIS, Minneapolis, MN) was dissolved in ethanol at 20 mg/mL and further diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10% Tween-80 to 4 mg/mL. Mice were injected with AMG487 (i.p., 20 mg/kg) or vehicle solutions at 1 and 12 hours before ONC procedure and continuously injected twice a day for 7 days after ONC procedure.25, 26, 27

Inhibitor Treatment

Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in PBS and diluted in PBS containing 10% Tween-80. Mice were injected with PDTC (i.p., 120 mg/kg) or vehicle solutions at 1 hour before ONC procedure. Stattic (10 mmol/L; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), an inhibitor for STAT1 and STAT3, was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide. ONC was performed on both eyes of mouse, and 1 μL Stattic or dimethyl sulfoxide was subjected to left or right eyes, respectively, by intravitreal injection at 1 hour after ONC procedure.

Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis

Retinas were collected at 3, 6, 12, and 24 hours after TON induction. Total RNA was isolated using RNA-4PCR kit (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD), quantified, and reverse transcribed using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies).28 cDNAs were amplified for 40 cycles using Power SYBR Green (Applied Biophysics, Inc., Troy, NY) and gene-specific primers in a StepOnePlus PCR system (Applied BioSciences, Foster, CA). Primer sequences for mouse transcripts were as follows: Hprt, 5′-GAAAGACTTGCTCGAGATGTCATG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CACACAGAGGGCCACAATGT-3′ (reverse); CXCL10, 5′-CATCCCTGCGAGCCTATCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CATCTCTGCTCATCATTCTTTTTCA-3′ (reverse); CXCR3, 5′-TTGCCCTCCCAGATTTCATC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGGCATTGAGGCGCTGAT-3′ (reverse); intercellular adhesion molecule 1, 5′-CAGTCCGCTGTGCTTTGAGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGGAAACGAATACACGGTGAT-3′ (reverse); and inducible nitric oxide synthase, 5′-GGCAGCCTGTGAGACCTTTG-3′ (forward) and 5′- TGCATTGGAAGTGAAGCGTTT-3′ (reverse). Gene expression levels were calculated by comparison of Ct values (ΔΔCt) using Hprt as the internal control.25

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

To determine CXCL10 level in the mouse retina, retina was homogenized with a pestle in 100 μL radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.25% deoxycholic acid, 1% NP-40, and 1 mmol/L EDTA) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN). The lysate was kept on ice for 15 minutes, and tissue debris was removed by centrifugation at 20,227 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant (5 μL) was used for protein quantitation by a BCA assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). The supernatant (80 μL) was used for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with Quantikine Mouse CXCL10 Immunoassay Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), following the manufacturer's instructions.21 The optical density was measured using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT). CXCL10 concentration was normalized to total protein in the lysate.

Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization

Retinal frozen sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, incubated with mouse CXCL10 probe (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Hayward, CA), and sequentially hybridized to a cascade of signal amplification reagents from RNAscope Fluorescent Multiplex detection kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sections were counterstained with DAPI to label nuclei and viewed by epifluorescence microscope to detect CXCL10 mRNA-positive cells.

Dark-Adapted ERG Analysis

TON was induced 24 hours or 7 days before electroretinographic (ERG) analysis. Mice were dark-adapted overnight, anesthetized by i.p. injection of a mixture of ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg) and xylazine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg), and their pupils were dilated with a mixture of atropine and phenylephrine. Mice were placed on a heating pad for maintaining body temperature, and gold ring electrodes were placed on the center of the cornea. ERG recordings were performed using the Espion ERG Diagnosys system (Diagnosys, Lowell, MA). Brief white flashes were presented from dim to bright, with the interstimulus interval increasing with brightness. The scotopic threshold responses (STRs), including positive STR (pSTR) and negative STR, were recorded in response to briefly flashed stimuli of −5.8 to −3.2 log cd-second/m2. pSTRs were measured at 110 milliseconds and negative STR were measured at 200 milliseconds from the flash onset.29, 30, 31 Dark-adapted flash ERG (a- and b-wave) was recorded using brief flashes of stimulus strengths from 0.4 to 2.5 log cd-second/m2. The amplitudes of a-wave were measured from the baseline to the lowest negative-going voltage, whereas the amplitudes of b-wave were measured from the trough of the a-wave to the peak of the positive b-wave. Each record was an average of 50 responses.

Immunostaining of Retinal Whole Mounts

Eyes were collected at 1 or 7 days after TON induction. After fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde, retinas were dissected from the choroid and sclera, blocked, and permeabilized in PBS containing 10% normal goat serum and 1% Triton X-100 for 30 minutes, and then incubated with antibodies against Tuj1 (1:400; BioLegend, San Diego, CA), CD45 (1:400; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), CD3 (1:10; BD Biosciences), Iba1 (1:400; Wako, Osaka, Japan), and Ly6G/Ly6C (1:400; BD Biosciences) overnight at 4°C. Retinas were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated donkey anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:400; Life Technologies). Finally, retinas were washed with PBS, mounted onto slides using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and examined with a fluorescence microscope.

Co-Culture of Primary RGCs and Leukocytes

Primary RGCs were isolated from WT mouse pups at postnatal day 3, as described in our previous study.21 The purity of the RGCs was determined by staining with mouse Tuj1 antibody, a specific RGC marker.32, 33 For bone marrow–derived leukocyte isolation, femurs were removed and bone marrow was harvested with minimum essential medium containing 1% fetal bovine serum. A single-cell suspension was collected by passing through an 80-μm cell strainer. To isolate blood leukocytes, WT mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and a syringe with a 26-gauge needle was inserted into the heart to draw blood. Blood (2 mL) was collected from WT mice, mixed with 8 mL of 30% Percoll/PBS (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL), overlaid on 4 mL of 70% Percoll/PBS in a 50-mL tube, and centrifuged at 400 × g for 30 minutes. Then, leukocytes, sitting in the middle layer of the solution, were carefully collected without disturbing other layers. After being washed once with Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), isolated bone marrow–derived or blood leukocytes (0.6 × 105 cells/well) were co-cultured with primary RGCs (1.3 × 105 cells/well), and cells were exposed to mouse CXCL10 (10 and 100 ng/mL) for 24 hours. Cells were then subjected to the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) for apoptosis detection, and double stained with anti-Tuj1 to distinguish RGCs from leukocytes. The total TUNEL/Tuj1 double-positive cells and Tuj1-positive cells in each field were counted under an Olympus 1 × 71 microscope (Olympus, Waltham, MA). The percentage of apoptotic RGCs was calculated as the ratio of total TUNEL/Tuj1 double-positive cells to total Tuj1-positive cells.

Flow Cytometry

Bone marrow–derived and blood leukocytes were isolated as described above, rinsed with Neurobasal media, and centrifuged at 287 × g for 5 minutes. Cell pellets were resuspended in Neurobasal media. To dissociate retinal cells, retinas of control and TON were collected, pooled, and minced in Dulbecco’s PBS and then centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 minutes at room temperature. Pellets were resuspended in a total of 1 mL of Dulbecco’s PBS with 0.5 mg/mL of Liberase enzyme mix (TM research grade; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) and 0.1 mg/mL DNase (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes with occasional agitation. After incubation, 10 mL of Neurobasal medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum was added to dissociate retinal cells, which were strained through a 40-μm nylon mesh strainer. The strained cell suspension was centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 minutes at room temperature, and pellets were resuspended in Neurobasal media. For flow cytometric analysis, 1 × 106 cells isolated from the bone marrow, blood, and retina were stained with fixable viability dye, blocked with FcγR blocker (CD16/32), and stained for specific surface molecules (namely, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD11b, CD11c, CD19, NK1.1, Ly6G, Ly6C, and γδ T-cell receptor). Data were collected on an LSRII FACSFortessa (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and analyzed with FlowJo software version 7.6 (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

Western Blot

Proteins were extracted from the retinas, and 10 μg of proteins was subjected to SDS-PAGE, as described previously.28 The primary antibodies included the following: p-STAT 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 and STAT1 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) and STAT3 (BD Biosciences). Mouse monoclonal anti–α-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as loading control. Proteins were detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as means ± SEM and analyzed by t-test and one-way analysis of variance, followed by post hoc t-test using the Student-Newman-Keuls method. Statistical analysis was conducted using the GraphPad Prism analytical program version 5.01 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Leukocytes Are Recruited to the Retina after Optic Nerve Injury

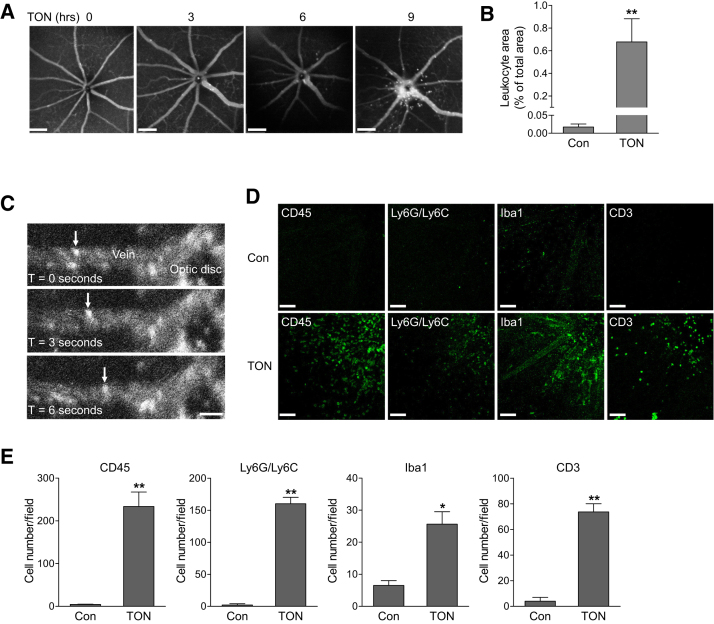

Studies were performed in a mouse model of ONC in which optic nerve is injured by a transient crush.34 The injured axon of RGC triggers a degenerative response that spreads retrogradely to the soma. The death of RGCs is progressive because the primary damage is followed by a wave of secondary degeneration.35, 36, 37 This model has been widely used to study the mechanism and strategies for neuroprotection in TON.34 To determine whether retinal vascular inflammation occurs after optic nerve injury, we transplanted bone marrow (BM) cells from green fluorescence protein (GFP) transgenic mice (WT-GFP+) into irradiated WT mice to produce chimeric mice (WT-GFP+→WT). These mice only expressed GFP in blood leukocytes, making it possible to specifically track leukocyte trafficking in retinal vessels in real time with an SLO. At 4 weeks after BM transplantation, analysis of blood leukocytes from WT-GFP+→WT chimeric mice revealed that the percentage of GFP-positive leukocytes (CD45+ cells) was approximately 78% (Supplemental Figure S2). Because a lead shield was used to protect the head and eyes during irradiation, a full chimerism could not be achieved, which is consistent with the finding of O’Koren et al.38 However, the dominant presence of leukocytes from GFP donor mice had made it possible to track the actions of leukocytes in TON by in vivo SLO imaging. We observed there was minimal leukocyte attachment to retinal vessels before ONC (Figure 1A and Supplemental Video S1), indicating there is no retinal inflammation in the recipient mice. This result is consistent with previous studies that, although whole body irradiation results in retinal damages and significant recruitment of bone marrow–derived cells,38, 39 such changes are prevented when a lead shield is used to cover the head and eyes.38, 40 At 3 to 6 hours after ONC, scattered leukocyte rolling and attachment was noticed. At 9 hours after injury, there were dramatic increases in leukocyte rolling, attachment, and infiltration in veins around the optic nerve head (Figure 1, A–C, and Supplemental Video S2), which resembles a typical vascular inflammatory reaction after tissue injury or infection.6 At 24 hours after crush, we analyzed infiltrated leukocytes in retinal flat-mount preparations from WT-GFP+→WT chimeric mice. Similar to SLO imaging, GFP-positive cells were localized in retinal vessels from noninjured control eye, whereas massive BM-derived leukocytes infiltrated into the superficial retina from TON-performed eye (Supplemental Figure S3).

Figure 1.

Leukocyte recruitment is increased after traumatic optic neuropathy (TON). A–C: Wild-type (WT) mice received bone marrow transplants from green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgenic mice and 4 weeks later they were subjected to TON. A: Images of leukocyte distribution in the central retina were taken at 0, 3, 6, and 9 hours after TON using real-time scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (SLO) imaging. B: Bar graph represents the quantification of percentage leukocyte area relative to total image area at 0 hour [control (Con)] and 9 hours after TON. C: Representative SLO image sequences at 9 hours after TON. Arrows indicate an example of GFP-positive leukocyte rolling along the major retinal vein. D and E: Eight-week-old WT mice were subjected to TON, and 24 hours later, noninjured control or TON-performed eyes were collected. D: Immunofluorescence staining for leukocyte subtype markers CD45, Ly6G/Ly6C, Iba1, and CD3 (green) in retinal flat-mounts. E: Bar graphs represent the quantification of recruited cells that were specifically labeled with antibodies against CD45, Ly6G/Ly6C, Iba1, and CD3. n = 5 mice (B and C); n = 3 mice (D and E). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus control. Scale bars: 200 μm (A); 50 μm (C and D). T, time elapsed after initiation of imaging.

To further identify leukocyte subtypes, we performed ONC in WT mice and at 24 hours after crush stained retinal flat-mount preparations with specific antibodies against the markers of leukocyte subtypes (Figure 1, D and E). In noninjured control retinas, no detectable leukocyte infiltration was noticed and microglia existed in the ramified and inactive state. After TON, a significant increase in leukocytes (CD45 positive) was observed in the superficial retina. Infiltrated cells were further identified as neutrophils (Ly6G/Ly6C positive), monocytes/microglia (Iba1 positive), and T lymphocytes (CD3 positive). B lymphocytes (CD19 positive) were not found in the retina (data not shown), although the antibody against CD19 did identify B lymphocytes in the spleen (Supplemental Figure S4). Because Iba1 staining could not differentiate monocytes and microglia, taking the advantage of WT-GFP+→WT chimeric mice that allows us to differentiate bone marrow–derived cells from other tissue, we further analyzed Iba1-positive cells in WT-GFP+→WT chimeric mice after TON (Supplemental Figure S3). Our results showed that some of Iba1-positive cells were infiltrated monocytes from blood (GFP positive) and some of Iba1-positive cells were residential microglia (GFP negative). Moreover, residential microglia appeared as phagocytic (ameboid) morphology, indicating an activated phenotype.

In addition to histological analysis, flow cytometry was used to characterize the populations and proportions of each leukocyte subtype. Similarly, CD45+ cells (total leukocytes), CD3+ cells (mostly T lymphocytes), CD11b+Ly6Ghigh (neutrophils), and CD11b+Ly6G− (nonneutrophil myeloid cells) were increased after TON (Supplemental Figure S5), whereas B cells were not detected in the retina (data not shown). Among cell types that were increased after crush, the increase in neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6Ghigh) is most dramatic (from 0.01% to 0.29%). In addition, in nonneutrophil myeloid cells, the percentage of CD11b+Ly6G−Ly6C−F4/80+ cells (macrophages and/or microglia) was decreased (from 87.5% to 68.9%), whereas the percentage of CD11b+Ly6G−Ly6C+ cells (monocytes or dendritic cells) was increased, suggesting influx of monocytes or dendritic cells into the retina after TON. A few natural killer cells (NK1.1+) were present in the retina, but their percentage was only marginally increased after TON. Because of the low amount of CD3+ cells, identification of CD3 subtypes failed. Altogether, these results demonstrate that leukocyte recruitment occurs in the neural retina after axonal injury.

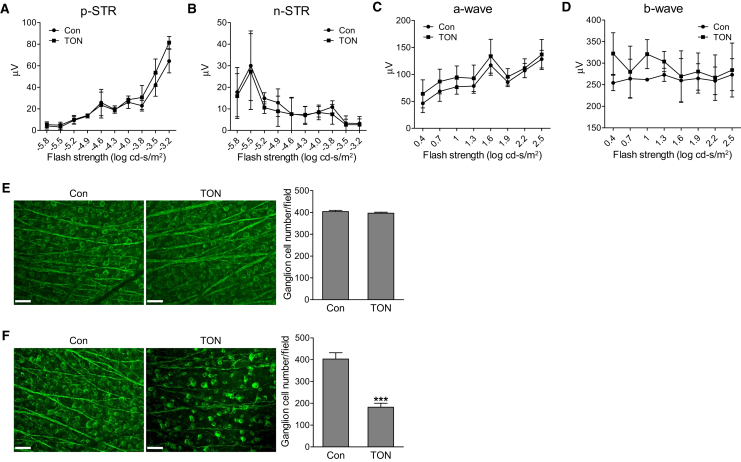

Leukocyte Recruitment Occurs before Neuronal Cell Dysfunction and Death

To determine the temporal relationship between leukocyte recruitment and retinal neuronal injury, we characterized retinal neuronal function with ERG and examined the number of RGCs in WT mice at 24 hours after axonal injury. The STRs, the most sensitive responses in the dark-adapted ERG,30 are generated in large part, especially for the pSTR, by RGCs in the mouse retina and serve as a useful measurement of RGC electrical function.41, 42 Flash ERGs are characterized by a series of waves of alternating polarity, including a- and b-waves, which are responses of photoreceptors and mainly optic nerve bipolar cells, respectively. As shown in Figure 2, A–D, we did not observe significant alterations for all the stimulus strengths analyzed in pSTR (which would include the slightly less sensitive positive scotopic response at stimulus strength30), negative STR, and flash ERG at 24 hours after axonal injury. In addition, loss of RGCs was not observed (Figure 2E) at this time point. However, RGC loss is remarkable at 7 days after injury (Figure 2F), consistent with Galindo-Romero's finding that RGC loss is not significant until 5 days after injury.43 These studies demonstrate that leukocyte recruitment is a much earlier event than detectable RGC loss and functional changes in TON.

Figure 2.

Analysis of retinal neuronal function and retinal ganglion cell loss. A–D: Wild-type mice were subjected to traumatic optic neuropathy (TON). Electroretinographic analysis for retinal neuronal function under scotopic conditions at 24 hours after TON. Graphs represent average amplitudes of positive scotopic threshold response (pSTR), negative STR (nSTR), and a- and b-waves over a range of stimulus strengths. E and F: Representative images of control (Con) and TON retinas labeled with Tuj1 antibody (green) at 24 hours (E) or 7 days (F) after TON. Graphs represent the number of Tuj1-positive cells per field. n = 3 mice (A–D); n = 4 mice (E and F). ∗∗∗P < 0.001 versus control. Scale bars = 50 μm (E and F).

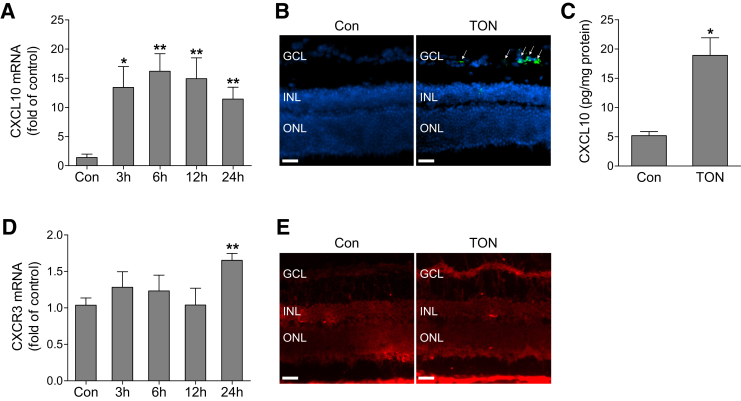

CXCL10/CXCR3 Pathway Is Up-Regulated in TON

The CXCR3 pathway plays an important role in inflammatory cell recruitment and neurodegenerative diseases.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 To investigate the potential mechanisms of leukocyte recruitment and neuronal damage in TON, we examined the expression of receptor CXCR3 and its ligands CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 in the ONC model. We found that axonal injury led to a sustained increase in CXCL10 mRNA levels (Figure 3A). However, the expression of CXCL9 and CXCL11 was undetectable. To determine the intraretinal distribution of CXCL10 mRNA expression, we performed fluorescence in situ hybridization on retinal cryosection, which revealed that CXCL10-expressing cells were mainly localized in the ganglion cell layer (Figure 3B). Correlated with the increase in mRNA, CXCL10 protein was significantly increased by approximately threefold, as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Figure 3C). Although CXCR3 mRNA was slightly elevated at 24 hours after ONC (Figure 3D), its immunoreactivity was predominantly increased in the ganglion cell layer after axonal injury (Figure 3E). These data suggest that the CXCL10/CXCR3 pathway may contribute to the pathological changes in TON.

Figure 3.

CXCL10/CXCR3 pathway is activated in TON. Wild-type mice were subjected to traumatic optic neuropathy (TON). A: Quantitative PCR analysis of CXCL10 mRNA expression in noninjured retinas [control (Con)] or injured retinas at 3, 6, 12, and 24 hours after TON. B: Normal and TON-performed eyes were collected at 6 hours after TON. CXCL10 mRNA localization was assessed in retinal frozen sections by fluorescence in situ hybridization with RNAscope Fluorescent Multiplex Kit. Green fluorescent signal reflects CXCL10 mRNA expression, and DAPI (blue) stains nuclei. Arrows indicate CXCL10-expressing retinal cells in the ganglion cell layer (GCL). C: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay analysis of CXCL10 protein in control or TON-performed retinas at 6 hours after TON. D: Quantitative PCR analysis of CXCR3 mRNA expression in control or injured retinas at 3, 6, 12, and 24 hours after TON. E: Representative images of CXCR3 immunostaining in retinal frozen sections from control and TON-performed eyes at 24 hours after TON. Fluorescent signal (red) reflects CXCR3 staining. n = 4 to 5 mice (E). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus control. Scale bars = 50 μm (B and E). INL, inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer.

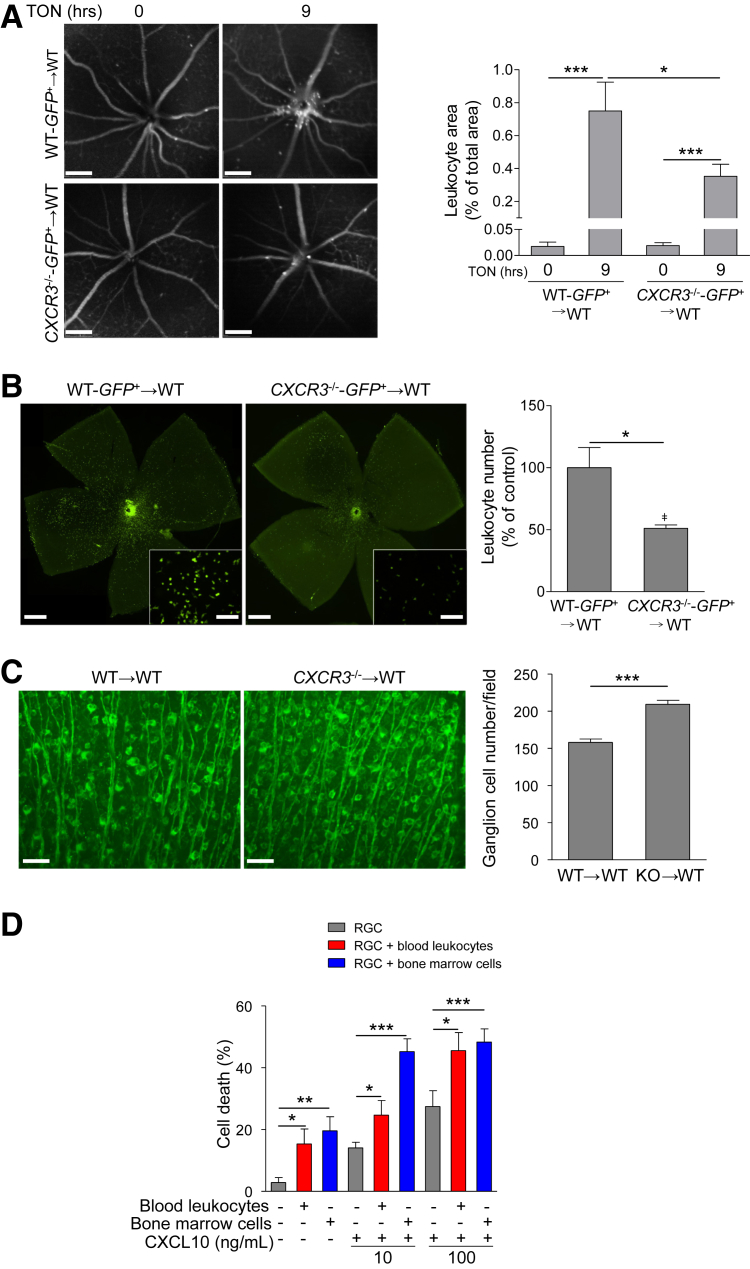

CXCL10/CXCR3 Pathway Is Involved in Leukocyte Recruitment and RGC Injury in TON

To determine whether up-regulation of CXCL10 in neural retina is responsible for leukocyte recruitment by binding to CXCR3 expressed on leukocytes, we transplanted bone marrow from donor mice WT-GFP+ or CXCR3−/−-GFP+ into WT mice (defined hereafter as WT-GFP+→WT or CXCR3−/−-GFP+→WT). SLO analysis revealed that fewer GFP-positive leukocytes infiltrated into the superficial retina near the ONH in WT mice receiving BM from CXCR3−/−-GFP+ mice than those receiving BM from WT-GFP+ mice at 9 hours after ONC (Figure 4A). Similarly, at 5 days after ONC, analysis of leukocyte distribution in retinal flat-mount preparations showed more GFP-positive leukocytes were present in the retina of WT mice receiving BM from WT-GFP+ than those receiving BM from CXCR3−/−-GFP+ mice (Figure 4B). These results indicate that the CXCL10/CXCR3 pathway is involved in leukocyte recruitment. To evaluate RGC loss, chimeric mice WT→WT or CXCR3−/−→WT were subjected to ONC, and RGCs within the ganglion cell layer were counted in flat-mounted retinas at 7 days after ONC. We found that associated with reduced leukocyte recruitment, RGCs, as determined by anti-Tuj1 staining, were significantly preserved in retinas of WT mice receiving BM from CXCR3−/− mice (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

CXCL10/CXCR3 pathway is involved in leukocyte recruitment and RGC death in the retina. A and B: Wild-type (WT) mice received bone marrow transplants from WT-GFP+ or CXCR3−/−-GFP+ mice (defined as WT-GFP+→WT or CXCR3−/−-GFP+→WT) and 4 weeks later they were subjected to traumatic optic neuropathy (TON). A: Images of leukocyte distribution in the central retina were taken before or 9 hours after TON using real-time scanning laser ophthalmoscopy imaging. Bar graph represents the quantification of leukocyte area at 0 and 9 hours after TON. B: Representative images of leukocyte distribution in retinal flat mounts from WT mice receiving bone marrow (BM) from WT-GFP+ or CXCR3−/−-GFP+ mice at 5 days after TON. High-magnification images are shown in insets. Bar graph represents the quantification of leukocyte number in the retina, which was normalized to WT-GFP+→WT mice after TON (control). C: WT mice received BM from WT or CXCR3−/− (knockout) (defined as WT→WT or CXCR3−/−→WT) and 4 weeks later they were subjected to TON. At 7 days after TON, retinas were collected and stained with Tuj1 antibody (green). Bar graph represents the number of Tuj1-positive cells per field. D: Primary RGCs were isolated, cultured alone, or co-cultured with bone marrow–derived or blood leukocytes, and treated with 10 or 100 ng/mL of CXCL10. At 24 hours after treatment, cells were subjected to terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay. The total TUNEL/Tuj1 double-positive cells and Tuj1-positive cells in each field were counted under a microscope. Bar graph represents the percentage of apoptotic RGCs, calculated as the ratio of total TUNEL/Tuj1 double-positive cells to total Tuj1-positive cells. Twenty fields were counted in each group. n = 6 mice (A); n = 3 (B, mice, and D, independent experiments). n = 5 to 7 mice (C). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. Scale bars: 200 μm (A); 500 μm (B); 100 μm (B, insets); 50 μm (C). Original magnification, ×200 (B).

To investigate the cause-and-effect relationship between reduction of leukocyte recruitment and increase in RGC survival, we asked the question whether leukocytes impair RGC viability. Primary mouse RGCs were isolated and co-cultured with leukocytes from blood or BM in the presence or absence of CXCL10. The morphology and purity of primary RGCs was determined by staining them with Tuj1 antibody (Supplemental Figure S6). The proportions of individual leukocyte subtypes after bone marrow and blood leukocyte preparation were determined by flow cytometry (Supplemental Figure S7). Our data showed that RGC apoptosis was significantly induced when RGCs were co-cultured with leukocytes (Figure 4D). Given that CXCL10, similar to other chemokines,44 not only participates in leukocyte recruitment but also induces leukocyte activation, such as proliferation and production of nitric oxide,45, 46 we reasoned that leukocytes would be continuously exposed to CXCL10 after recruited to the retina, which may affect their activity toward retinal injury. Therefore, we added CXCL10 into the co-culture of RGC and leukocyte and found addition of CXCL10 augmented leukocyte-induced cell death (Figure 4D).

Taking the above in vivo and in vitro data together, our findings suggest that injured neuronal retina releases CXCL10 to recruit and activate leukocytes in a CXCR3-dependent manner. Recruited leukocytes then play a key role in inducing RGC death in TON by directly damaging RGCs. As an experimental control, RGCs were treated with CXCL10 in the absence of leukocytes. We found RGC apoptosis was increased by CXCL10 treatment (Figure 4D), suggesting a direct effect of CXCL10 on RGC survival during injury.

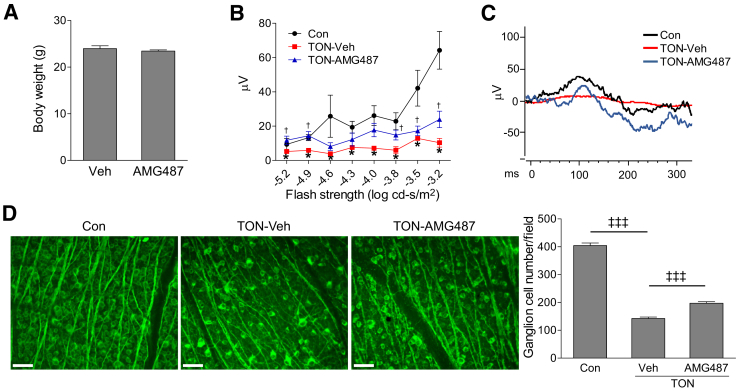

Pharmacological Blockade of CXCR3 Partially Prevents RGC Dysfunction and Cell Loss after TON

The above results from genetic approaches suggest that blocking CXCR3 may be beneficial for the neuroprotection after TON. Therefore, we tested whether blockade of CXCR3 by AMG487, a potent and orally bioavailable CXCR3 antagonist,47, 48 is neuroprotective after TON. WT mice were injected with AMG487 (i.p., 20 mg/kg) or vehicle solution (i.p., PBS containing 10% Tween-80 and 20% ethanol) at 1 and 12 hours before TON and continuously injected twice a day for 7 days. Compared with mice without any treatment (naive), vehicle injection (i.p.) did not affect body weight, RGC numbers and ERG responses (Supplemental Figure S8), food/water consumption and feces, breathing/behavior, and hunching, indicating that vehicle treatment is neither toxic to mice nor to the retina. Similarly, AMG487 treatment did not show adverse effects, such as change in body weight (Figure 5A), food/water consumption and feces, breathing/behavior, and hunching. To assess the functional consequence of CXCR3 inhibition, we performed ERG analysis. Consistent with reports from other groups,42, 49, 50 ONC resulted in a significant reduction of pSTR amplitudes in vehicle-treated mice at 7 days after axonal injury. However, this reduction was significantly attenuated by AMG487 treatment (Figure 5, B and C). Associated with the preservation of ERG responses, AMG487 treatment partially prevented RGC loss at 7 days after TON (Figure 5D). These data suggest that pharmacological blockade of CXCR3 is a promising approach for neuroprotection after TON.

Figure 5.

AMG487, antagonist of CXCR3, preserves retinal function and prevents retinal ganglion cell loss after traumatic optic neuropathy (TON). Wild-type mice were i.p. injected with vehicle (Veh) or AMG487 (20 mg/kg) at 1 and 12 hours before TON procedure and continuously injected twice a day for 7 days after TON. A: Body weights of vehicle- and AMG487-treated TON mice. B: Graph represents average amplitudes of positive scotopic threshold response (pSTR) over a range of stimulus strengths. C: Representative pSTR patterns for stimuli of −4.0 log cd-second/m2. D: Retinas were collected from noninjured mice [control (Con)] and TON mice treated with vehicle or AMG487. Representative images of retinal flat mounts labeled with Tuj1 antibody (green) were shown. Bar graph represents the number of Tuj1-positive cells per field. n = 5 to 7 mice (B); n = 8 to 9 mice (D). ∗P < 0.05 versus noninjured control mice (Con); †P < 0.05 versus vehicle-treated TON mice; ‡‡‡P < 0.001. Scale bars = 50 μm.

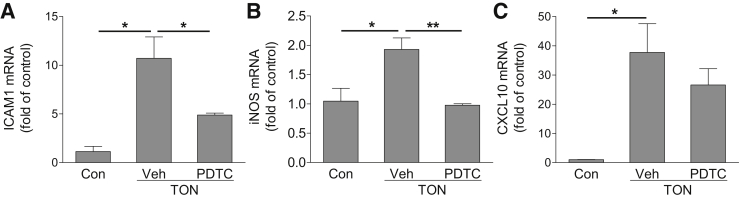

Up-Regulation of CXCL10 in TON Is Mediated by STAT

Given that the CXCL10/CXCR3 axis is involved in leukocyte recruitment and RGC damage, it would be important to understand the potential mechanisms by which CXCL10 is up-regulated after axonal injury. Sequence analysis revealed that the CXCL10 promoter region contains transcription factor binding sites for AP-1, NF-κB, interferon regulatory factor, and STAT.51, 52 Because activation of NF-κB has an essential role in inflammatory reactions and has been shown to induce CXCL10 expression during virus infection,51, 52 we reasoned that CXCL10 up-regulation in TON might be mediated by NF-κB. We pretreated mice with PDTC at a concentration (i.p., 120 mg/kg) shown to effectively inhibit NF-κB–mediated gene expression and inflammation in vivo,53, 54 induced TON, and examined CXCL10 expression. PDTC treatment significantly reduced the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and inducible nitric oxide synthase, which are two NF-κB–driven inflammatory molecules (Figure 6, A and B). However, CXCL10 expression was not changed after PDTC treatment (Figure 6C), suggesting that NF-κB did not mediate TON-induced CXCL10 expression.

Figure 6.

NF-κB signaling is not involved in traumatic optic neuropathy (TON)-induced CXCL10 expression. NF-κB inhibitor pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC; i.p., 120 mg/kg) or vehicle (Veh) was injected into wild-type mice at 1 hour before TON. Retinas were collected at 6 hours after TON. The mRNA expressions of intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM) 1 (A), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS; B), and CXCL10 (C) were analyzed by quantitative PCR. n = 4 to 5 mice (A–C). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

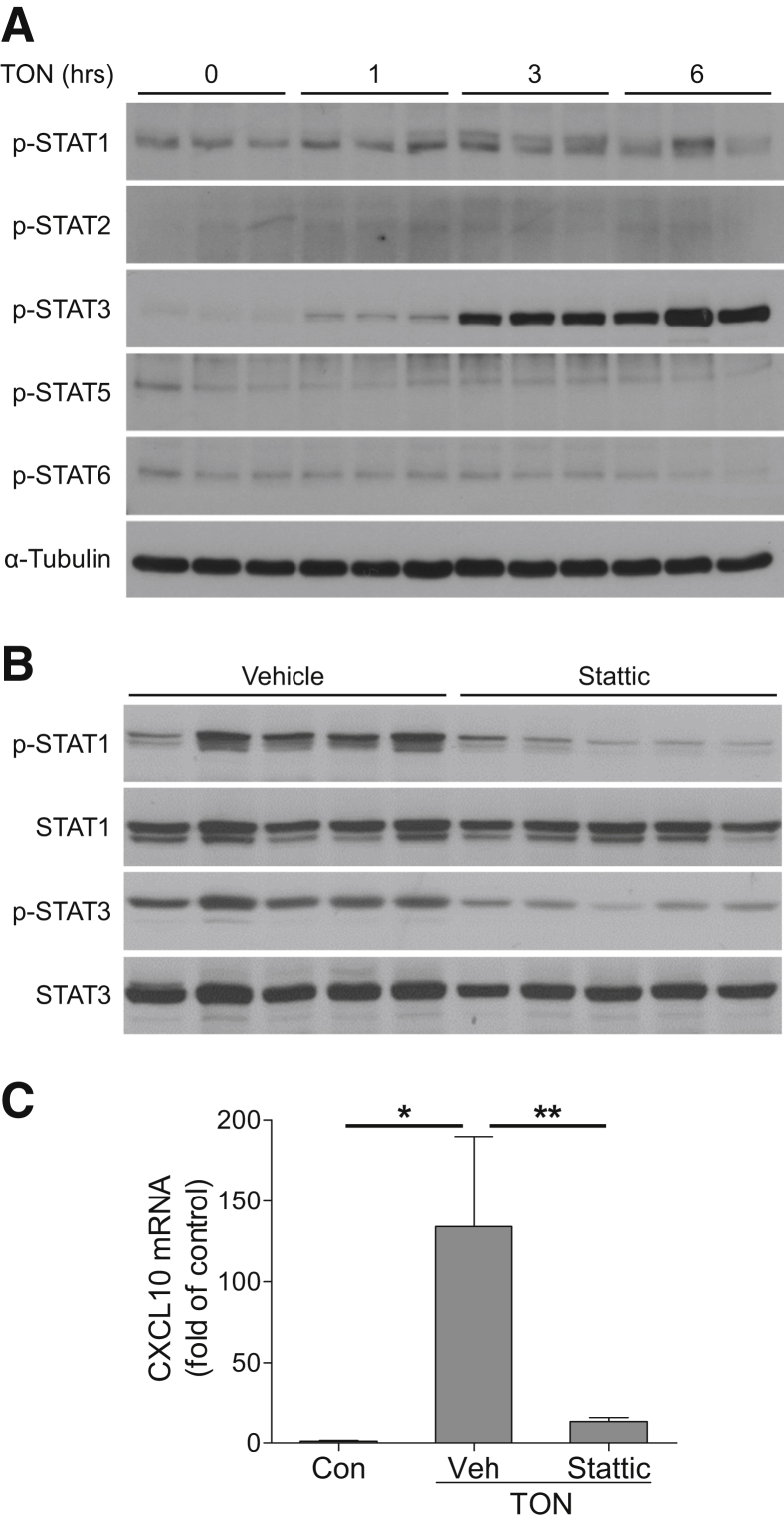

The STAT proteins are a family of transcription factors that regulate the expression of genes related with development and immune system in two ways: directly binding to STAT binding sites in the promoter of genes or indirectly binding to other transcription factors, such as interferon regulatory factor.55 To investigate the potential involvement of STATs in TON-induced CXCL10 production, we measured STAT phosphorylation after axonal injury. Our data showed marked increases in STAT1 and STAT3 phosphorylation at 1, 3, and 6 hours after axonal injury, whereas the phosphorylation of STAT 2, 5, and 6 was not changed (Figure 7A), suggesting both STAT1 and STAT3 were activated after injury. Furthermore, we intravitreally injected Stattic, which inhibits both STAT1 and STAT3 activation56 at 1 hour after the induction of TON. At 4 hours after TON, Stattic blocks both STAT1 and STAT3 phosphorylation (Figure 7B), and significantly blocked TON-induced CXCL10 expression (Figure 7C). These results indicate that activation of STAT1/3 is involved in up-regulation of CXCL10 after axonal injury.

Figure 7.

Traumatic optic neuropathy (TON)-induced CXCL10 up-regulation is modulated by STAT signaling. A: Wild-type (WT) mice were subjected to TON, and proteins were isolated from retinas at indicated time points after TON. The phosphorylation levels of STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT5, and STAT6 were evaluated by Western blotting. α-Tubulin was used as loading control. B and C: STAT1/STAT3 inhibitor Stattic or vehicle (Veh) was injected intravitreally into WT mice at 1 hour after the induction of TON. Retinas were collected at 4 hours after TON. B: Phosphorylated and total STAT1 and STAT3 were assessed by Western blotting. C: The expression of CXCL10 mRNA was analyzed by quantitative PCR. n = 5 mice (A–C). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

Discussion

Mechanisms of RGC death after axonal injury in TON remain to be defined. In the present study, our data clearly show that expressions of CXCL10 and CXCR3 are increased after axonal injury and specifically deleting CXCR3 in leukocytes significantly reduces leukocyte recruitment into retinal tissue while enhancing RGC survival in TON. In addition, blockade of CXCR3 with a pharmacological antagonist AMG487 not only prevents RGC loss but also preserves RGC function in TON. Given that TON is critically involved in vision loss after accidents or assaults, but there is no proven therapy yet, pharmacological interventions that can save and reverse the function of retina are highly wanted. Our study suggests that blocking CXCR3 is beneficial and warrants further investigation of this pathway in TON as well as evaluation of the effects of a number of CXCR3 antagonists, which are in clinical development for treating inflammatory diseases in human subjects. This study, together with previous findings that deleting CXCR3 prevents retinal neuronal cell death after an acute increase in intraocular pressure,21 prolongs survival times after prion infection,57 reduces NMDA-induced neuronal cell death in brain,58 and attenuates plaque formation and behavioral deficits in Alzheimer disease,59 highlights a role of CXCR3 in neurodegenerative diseases.

The CXCL10/CXCR3 axis plays a critical role in inflammation by recruiting activated T lymphocytes, monocytes, and macrophages.12, 14, 58, 60 We found that CXCL10 expression is up-regulated in cells, including RGCs, after axonal injury, which is associated with leukocyte recruitment and infiltration in neural retina. To investigate potential mechanisms of CXCR3-mediated RGC death in TON, we deleted CXCR3 in leukocytes and found that leukocyte recruitment is attenuated and RGC survival is increased. When RGCs are co-cultured with leukocytes, RGC viability is significantly reduced in the presence of leukocytes, which is augmented by CXCL10. Our data suggest a model that injured or stressed RGCs and other cells in neural retina release CXCL10 to recruit and activate leukocytes, which further exaggerate RGC death, likely by producing reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide, or toxic cytokines, or activating cell death signals, similar to the way of leukocyte-induced cell death in other pathological conditions.61, 62, 63 Certainly, the marked reduction of leukocyte recruitment after deleting CXCR3 in leukocytes does not mean that all of those leukocytes that failed to be recruited into the retina express CXCR3. It is possible that CXCR3-expressing leukocytes play an important role in the initiation of inflammatory response by secreting cytokines that amplify inflammatory reactions in the retina, resulting in recruitment of non–CXCR3-expressing cells. Consequently, deleting CXCR3 in leukocytes not only blocks the recruitment of CXCR3-expressing cells but also attenuates the recruitment of non–CXCR3-expressing leukocytes. Interestingly, our in vitro experiments also found that CXCL10 has a direct effect on RGC survival. Although underlying mechanisms are unclear, similar effects of CXCL10 are observed in brain neuronal culture and endothelial cells in a mechanism involving CXCR3-mediated caspase 3 activation.64, 65

Leukocyte recruitment is a response to tissue injury and infection and contributes to the development and resolution of many infectious diseases. Leukocyte imaging has been used for three decades as the gold standard for the imaging and diagnosis of most infections in the immunocompetent population.66 The value of leukocyte imaging in retinal diseases has not been established, although leukostasis is a key feature of diabetic retinopathy.67 By combination of leukocytes labeling with GFP and noninvasive SLO imaging, we demonstrated that leukocyte rolling, adhesion, and infiltration in retinal vessels occur much earlier than other pathological changes after axonal injury, including RGC loss and reduction of retinal ERG response. Because leukocyte recruitment occurs not only as an early response to RGC injury but also contributes to RGC death, our data suggest that leukocyte recruitment has the features of a biomarker and warrants further investigation to determine whether leukocyte imaging in the retina could be used to foresee the severity of neuronal injury in TON and predict the outcome of emerging therapeutic interventions.

Interestingly, although our studies support the notion that leukocytes contribute to RGC death after axonal injury, other roles of leukocytes in retinal neuronal degeneration and regeneration are also reported. Lens injury or intravitreal injection of zymosan (a yeast cell wall preparation) causes massive infiltration of neutrophils and monocytes into the vitreous, which promotes the axonal regeneration of RGCs by producing oncomodulin.68, 69 However, intravitreal injection of lipopolysaccharide (a cell wall component of Gram-negative bacteria) fails to stimulate axonal regeneration despite inducing tremendous leukocyte infiltration similar to zymosan.70 Meanwhile, lipopolysaccharide injection causes retinal neuronal damage and dysfunction.71, 72 These contradictory observations suggest that leukocytes play complicated roles in RGC injury and axonal regeneration. It is possible that distinct subsets of leukocytes differentially regulate these processes. Neutrophils may contribute to tissue-specific injury by blocking blood flow, generating reactive oxygen species, and producing proteases.73 However, protective and regenerative roles of neutrophils are also reported in certain conditions.73, 74 Myeloid cells also differentially affect tissue injury, depending on their phenotypes. Macrophages are proinflammatory and cause tissue injury when they are polarized into the M1 phenotype, whereas they are anti-inflammatory and promote tissue repair and regeneration in the M2 phenotype.70 T cells can induce tissue injury by recruiting macrophages and dendritic cells, and producing cytokines.75 In this study, we found that neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages, and T cells are all recruited into the superficial retina after axonal injury. With flow cytometric analysis, our data show that myeloid cells are the major leukocyte subtype that infiltrate into the retina after axonal injury. Future studies to specifically delete leukocyte subtypes, such as neutrophils and monocytes, or modulate their activation are needed to address their specific contributions to RGC injury in TON.

CXCL10 is normally expressed at a low level under physiological conditions but is up-regulated during infection to attract immune cells to clear pathogens. In our studies of TON, sterile inflammation occurs in the absence of live pathogens, and we found that CXCL10 up-regulation is associated with STAT1 and STAT3 activation and its production is significantly attenuated by blocking STAT1 and STAT3 activation with Stattic. In contrast, NF-κB, a proinflammatory transcription factor regulating CXCL10 expression after viral infection,51, 52 does not participate in axonal injury-induced CXCL10 expression. To our knowledge, this is the first report that provides evidence suggesting that STAT1 and STAT3 appear to regulate CXCL10 level during sterile inflammation. Our data suggest that STAT1 and STAT3 inhibitors, which are being developed to treat cancers and inflammatory diseases,76, 77 may be potentially suitable to block CXCL10-mediated retinal inflammation and save retinal neurons in TON.

In summary, herein, we found that leukocyte recruitment is an early event in TON and identified a novel mechanism that the CXCL10/CXCR3 pathway has an important role in leukocyte recruitment and RGC injury in TON and that up-regulation of CXCL10 is mediated by STAT1 and STAT3. Because inflammation is involved in many diseases, such as stroke, diabetic retinopathy and glaucoma, further studies to explore CXCR3-mediated leukocyte recruitment and tissue injury, specify the contribution of leukocyte subtypes in neuronal degeneration and regeneration, and evaluate the therapeutic potential of inhibitors for STAT1, STAT3, and CXCR3, may facilitate the development of novel interventions for these diseases associated with neuronal injury.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grant EY022694, American Heart Association grant 11SDG4960005, the John Sealy Memorial Endowment Fund for Biomedical Research, Retina Research Foundation (W.Z.), the University of Texas System Neuroscience and Neurotechnology Research Institute (R.K. and W.Z.), BrightFocus Foundation grant G2015044 (Y.H.), and American Heart Association grant 15POST22450025 (H.L.).

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.10.009.

Supplemental Data

Leukocyte trafficking before TON. Noninvasive scanning laser ophthalmoscopy imaging shows there was minimal leukocyte attachment to retinal vessels before optic nerve crush.

Leukocyte trafficking at 9 hours after TON. Noninvasive scanning laser ophthalmoscopy imaging shows there were dramatic increases in leukocyte rolling, attachment, and infiltration in veins around the optic nerve head at 9 hours after optic nerve crush.

Genotype and phenotype analysis of representative offspring mice. A: Representative genotyping results of PCR analysis for wild type (WT; 1, only with 337-bp WT allele) and CXCR3 knockout (KO; 2, only with 485-bp KO allele) mice. B: Representative phenotyping results of GFP+ transgenic mice using blue light-emitting diode laser point.

Analysis of green fluorescent protein (GFP)–positive leukocytes in the blood of GFP bone marrow transplanted (BMT) mice. C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) mice were transplanted with bone marrow from GFP transgenic mice and 4 weeks later, blood was collected for flow cytometry. Representative histogram shows the percentage of GFP+ leukocytes in the blood of WT and BMT mice. n = 3 mice. Max, maximum.

Distribution of leukocytes and microglia in retinas after axonal injury. Wild-type mice received bone marrow transplant from green fluorescent protein (GFP) mice and 4 weeks later they were subjected to TON. At 24 hours after TON, retinas were fixed and labeled with Iba1 antibody (red) to identify microglia/monocytes. Green dots indicate GFP-positive cells. n = 3 mice. Scale bars = 50 μm. CON, control.

CD19 staining in the spleen. Spleen frozen section was used as a positive control for antibody against CD19 (red). DAPI (blue) stains nuclei. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Characterization of leukocytes in the TON retinas. Retinas were collected at 24 hours after TON and enzymatically dissociated to produce single cells for flow cytometric analysis. Cells were stained with antibodies against markers for leukocyte subtypes: CD45, CD3, CD11b, Ly6G, Ly6C, F4/80, and NK1.1. Plots of flow cytometric analyses are shown. Percentage indicates the proportion of CD45+ leukocytes, CD3+ T cells, CD11b+Ly6Ghigh neutrophils, CD11b+Ly6G− nonneutrophil myeloid cells, and NK1.1+ natural killer cells in total retinal cells from Control (Ctrl) and TON retinas. n = 14 mice.

Confirmation of purity of isolated primary RGCs. RGCs were isolated from wild-type pups at postnatal day 3 and stained with retinal ganglion cell marker Tuj1 antibody (green). DAPI (blue) stains nuclei. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Characterization of leukocytes isolated from bone marrow and blood. Leukocytes were isolated from bone marrow (A) and blood (B), and the populations and proportions of individual leukocyte subtypes were analyzed by flow cytometry. Plots for the percentage of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, γδ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, NK T cells (CD3+NK1.1+), B cells (CD19+), neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6Ghigh), and nonneutrophil myeloid cells [CD11b+Ly6G− (eg, monocytes and dendritic cells)] are shown. n = 8 mice. SSC, side scatter.

Confirmation of nontoxicity of vehicle used for AMG487 treatment. Wild-type mice were injected with vehicle (Veh, i.p.) twice a day for 7 days. A: Body weight of naive and vehicle-treated mice. B: Representative images of retinas labeled with Tuj1 antibody (green) at 7 days after vehicle injection. Graph represents the number of Tuj1-positive cells per field. C: Electroretinographic analysis for retinal neuronal function under scotopic conditions between naive and vehicle-treated groups after 7 days of treatment. Graphs represent average amplitudes of a- and b-waves and positive scotopic threshold response over a range of stimulus strengths. n = 4 mice (B and C). Scale bars = 50 μm.

References

- 1.Ahmad S., Fatteh N., El-Sherbiny N.M., Naime M., Ibrahim A.S., El-Sherbini A.M., El-Shafey S.A., Khan S., Fulzele S., Gonzales J., Liou G.I. Potential role of A2A adenosine receptor in traumatic optic neuropathy. J Neuroimmunol. 2013;264:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furtado J.M., Lansingh V.C., Carter M.J., Milanese M.F., Pena B.N., Ghersi H.A., Bote P.L., Nano M.E., Silva J.C. Causes of blindness and visual impairment in Latin America. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57:149–177. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarkies N. Traumatic optic neuropathy. Eye (Lond) 2004;18:1122–1125. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu N., Yin Z.Q., Wang Y. Traumatic optic neuropathy therapy: an update of clinical and experimental studies. J Int Med Res. 2008;36:883–889. doi: 10.1177/147323000803600503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang W., Liu H., Al-Shabrawey M., Caldwell R.W., Caldwell R.B. Inflammation and diabetic retinal microvascular complications. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2011;2:96–103. doi: 10.4103/0975-3583.83035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nourshargh S., Alon R. Leukocyte migration into inflamed tissues. Immunity. 2014;41:694–707. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallach D., Kang T.B., Kovalenko A. Concepts of tissue injury and cell death in inflammation: a historical perspective. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:51–59. doi: 10.1038/nri3561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tezel G., Yang X., Yang J., Wax M.B. Role of tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 in the death of retinal ganglion cells following optic nerve crush injury in mice. Brain Res. 2004;996:202–212. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tonari M., Kurimoto T., Horie T., Sugiyama T., Ikeda T., Oku H. Blocking endothelin-B receptors rescues retinal ganglion cells from optic nerve injury through suppression of neuroinflammation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:3490–3500. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng Z., Yuan R., Song M., Huo Y., Liu W., Cai X., Zou H., Chen C., Ye J. The toll-like receptor 4-mediated signaling pathway is activated following optic nerve injury in mice. Brain Res. 2012;1489:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen L., Pei G., Zhang W. An overall picture of chemokine receptors: basic research and drug development. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:1045–1055. doi: 10.2174/1381612043452749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacotte S., Brun S., Muller S., Dumortier H. CXCR3, inflammation, and autoimmune diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173:310–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Jong E.K., de Haas A.H., Brouwer N., van Weering H.R., Hensens M., Bechmann I., Pratley P., Wesseling E., Boddeke H.W., Biber K. Expression of CXCL4 in microglia in vitro and in vivo and its possible signaling through CXCR3. J Neurochem. 2008;105:1726–1736. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taub D.D., Lloyd A.R., Conlon K., Wang J.M., Ortaldo J.R., Harada A., Matsushima K., Kelvin D.J., Oppenheim J.J. Recombinant human interferon-inducible protein 10 is a chemoattractant for human monocytes and T lymphocytes and promotes T cell adhesion to endothelial cells. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1809–1814. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torraca V., Cui C., Boland R., Bebelman J.P., van der Sar A.M., Smit M.J., Siderius M., Spaink H.P., Meijer A.H. The CXCR3-CXCL11 signaling axis mediates macrophage recruitment and dissemination of mycobacterial infection. Dis Model Mech. 2015;8:253–269. doi: 10.1242/dmm.017756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y., Gehringer R., Mousa S.A., Hackel D., Brack A., Rittner H.L. CXCL10 controls inflammatory pain via opioid peptide-containing macrophages in electroacupuncture. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X., Ellison J.A., Siren A.L., Lysko P.G., Yue T.L., Barone F.C., Shatzman A., Feuerstein G.Z. Prolonged expression of interferon-inducible protein-10 in ischemic cortex after permanent occlusion of the middle cerebral artery in rat. J Neurochem. 1998;71:1194–1204. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71031194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galimberti D., Schoonenboom N., Scheltens P., Fenoglio C., Bouwman F., Venturelli E., Guidi I., Blankenstein M.A., Bresolin N., Scarpini E. Intrathecal chemokine synthesis in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:538–543. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.4.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balashov K.E., Rottman J.B., Weiner H.L., Hancock W.W. CCR5(+) and CXCR3(+) T cells are increased in multiple sclerosis and their ligands MIP-1alpha and IP-10 are expressed in demyelinating brain lesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:6873–6878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jo N., Wu G.S., Rao N.A. Upregulation of chemokine expression in the retinal vasculature in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:4054–4060. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ha Y., Liu H., Xu Z., Yokota H., Narayanan S.P., Lemtalsi T., Smith S.B., Caldwell R.W., Caldwell R.B., Zhang W. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-regulated CXCR3 pathway mediates inflammation and neuronal injury in acute glaucoma. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1900. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Templeton J.P., Geisert E.E. A practical approach to optic nerve crush in the mouse. Mol Vis. 2012;18:2147–2152. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rojas M., Zhang W., Xu Z., Lemtalsi T., Chandler P., Toque H.A., Caldwell R.W., Caldwell R.B. Requirement of NOX2 expression in both retina and bone marrow for diabetes-induced retinal vascular injury. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seeliger M.W., Beck S.C., Pereyra-Munoz N., Dangel S., Tsai J.Y., Luhmann U.F., van de Pavert S.A., Wijnholds J., Samardzija M., Wenzel A., Zrenner E., Narfstrom K., Fahl E., Tanimoto N., Acar N., Tonagel F. In vivo confocal imaging of the retina in animal models using scanning laser ophthalmoscopy. Vision Res. 2005;45:3512–3519. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmittgen T.D., Lee E.J., Jiang J., Sarkar A., Yang L., Elton T.S., Chen C. Real-time PCR quantification of precursor and mature microRNA. Methods. 2008;44:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cambien B., Karimdjee B.F., Richard-Fiardo P., Bziouech H., Barthel R., Millet M.A., Martini V., Birnbaum D., Scoazec J.Y., Abello J., Al Saati T., Johnson M.G., Sullivan T.J., Medina J.C., Collins T.L., Schmid-Alliana A., Schmid-Antomarchi H. Organ-specific inhibition of metastatic colon carcinoma by CXCR3 antagonism. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1755–1764. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walser T.C., Rifat S., Ma X., Kundu N., Ward C., Goloubeva O., Johnson M.G., Medina J.C., Collins T.L., Fulton A.M. Antagonism of CXCR3 inhibits lung metastasis in a murine model of metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7701–7707. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ameri H., Liu H., Liu R., Ha Y., Paulucci-Holthauzen A.A., Hu S., Motamedi M., Godley B.F., Tilton R.G., Zhang W. TWEAK/Fn14 pathway is a novel mediator of retinal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:801–813. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ha Y., Saul A., Tawfik A., Williams C., Bollinger K., Smith R., Tachikawa M., Zorrilla E., Ganapathy V., Smith S.B. Late-onset inner retinal dysfunction in mice lacking sigma receptor 1 (sigmaR1) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:7749–7760. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saszik S.M., Robson J.G., Frishman L.J. The scotopic threshold response of the dark-adapted electroretinogram of the mouse. J Physiol. 2002;543:899–916. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.019703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ha Y., Saul A., Tawfik A., Zorrilla E.P., Ganapathy V., Smith S.B. Diabetes accelerates retinal ganglion cell dysfunction in mice lacking sigma receptor 1. Mol Vis. 2012;18:2860–2870. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCabe K.L., Gunther E.C., Reh T.A. The development of the pattern of retinal ganglion cells in the chick retina: mechanisms that control differentiation. Development. 1999;126:5713–5724. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.24.5713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang L., Hu F., Xie X., Harder J., Fernandes K., Zeng X.Y., Libby R., Gan L. Pou4f1 and pou4f2 are dispensable for the long-term survival of adult retinal ganglion cells in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levkovitch-Verbin H. Animal models of optic nerve diseases. Eye (Lond) 2004;18:1066–1074. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levkovitch-Verbin H., Quigley H.A., Kerrigan-Baumrind L.A., D'Anna S.A., Kerrigan D., Pease M.E. Optic nerve transection in monkeys may result in secondary degeneration of retinal ganglion cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:975–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoles E., Schwartz M. Degeneration of spared axons following partial white matter lesion: implications for optic nerve neuropathies. Exp Neurol. 1998;153:1–7. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levkovitch-Verbin H., Quigley H.A., Martin K.R., Zack D.J., Pease M.E., Valenta D.F. A model to study differences between primary and secondary degeneration of retinal ganglion cells in rats by partial optic nerve transection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3388–3393. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Koren E.G., Mathew R., Saban D.R. Fate mapping reveals that microglia and recruited monocyte-derived macrophages are definitively distinguishable by phenotype in the retina. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20636. doi: 10.1038/srep20636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen M., Zhao J., Luo C., Pandi S.P., Penalva R.G., Fitzgerald D.C., Xu H. Para-inflammation-mediated retinal recruitment of bone marrow-derived myeloid cells following whole-body irradiation is CCL2 dependent. Glia. 2012;60:833–842. doi: 10.1002/glia.22315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaneko H., Nishiguchi K.M., Nakamura M., Kachi S., Terasaki H. Characteristics of bone marrow-derived microglia in the normal and injured retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:4162–4168. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moshiri A., Gonzalez E., Tagawa K., Maeda H., Wang M., Frishman L.J., Wang S.W. Near complete loss of retinal ganglion cells in the math5/brn3b double knockout elicits severe reductions of other cell types during retinal development. Dev Biol. 2008;316:214–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y., McDowell C.M., Zhang Z., Tebow H.E., Wordinger R.J., Clark A.F. Monitoring retinal morphologic and functional changes in mice following optic nerve crush. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:3766–3774. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-13895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galindo-Romero C., Aviles-Trigueros M., Jimenez-Lopez M., Valiente-Soriano F.J., Salinas-Navarro M., Nadal-Nicolas F., Villegas-Perez M.P., Vidal-Sanz M., Agudo-Barriuso M. Axotomy-induced retinal ganglion cell death in adult mice: quantitative and topographic time course analyses. Exp Eye Res. 2011;92:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adams D.H., Lloyd A.R. Chemokines: leucocyte recruitment and activation cytokines. Lancet. 1997;349:490–495. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07524-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogasawara K., Hida S., Weng Y., Saiura A., Sato K., Takayanagi H., Sakaguchi S., Yokochi T., Kodama T., Naitoh M., De Martino J.A., Taniguchi T. Requirement of the IFN-alpha/beta-induced CXCR3 chemokine signalling for CD8+ T cell activation. Genes Cells. 2002;7:309–320. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vasquez R.E., Soong L. CXCL10/gamma interferon-inducible protein 10-mediated protection against Leishmania amazonensis infection in mice. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6769–6777. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01073-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wijtmans M., Verzijl D., Leurs R., de Esch I.J., Smit M.J. Towards small-molecule CXCR3 ligands with clinical potential. ChemMedChem. 2008;3:861–872. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200700365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson M., Li A.R., Liu J., Fu Z., Zhu L., Miao S., Wang X., Xu Q., Huang A., Marcus A., Xu F., Ebsworth K., Sablan E., Danao J., Kumer J., Dairaghi D., Lawrence C., Sullivan T., Tonn G., Schall T., Collins T., Medina J. Discovery and optimization of a series of quinazolinone-derived antagonists of CXCR3. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:3339–3343. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.03.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alarcon-Martinez L., Aviles-Trigueros M., Galindo-Romero C., Valiente-Soriano J., Agudo-Barriuso M., Villa Pde L., Villegas-Perez M.P., Vidal-Sanz M. ERG changes in albino and pigmented mice after optic nerve transection. Vision Res. 2010;50:2176–2187. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yukita M., Machida S., Nishiguchi K.M., Tsuda S., Yokoyama Y., Yasuda M., Maruyama K., Nakazawa T. Molecular, anatomical and functional changes in the retinal ganglion cells after optic nerve crush in mice. Doc Ophthalmol. 2015;130:149–156. doi: 10.1007/s10633-014-9478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brownell J., Bruckner J., Wagoner J., Thomas E., Loo Y.M., Gale M., Jr., Liang T.J., Polyak S.J. Direct, interferon-independent activation of the CXCL10 promoter by NF-kappaB and interferon regulatory factor 3 during hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2014;88:1582–1590. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02007-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spurrell J.C., Wiehler S., Zaheer R.S., Sanders S.P., Proud D. Human airway epithelial cells produce IP-10 (CXCL10) in vitro and in vivo upon rhinovirus infection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L85–L95. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00397.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang X., Shao C., Wu Q., Wu Q., Huang M., Zhou Z. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate attenuates paraquat-induced lung injury in rats. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2009;2009:619487. doi: 10.1155/2009/619487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao J., Shao Z., Zhang X., Ding R., Xu J., Ruan J., Zhang X., Wang H., Sun X., Huang C. Suppression of perfluoroisobutylene induced acute lung injury by pretreatment with pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate. J Occup Health. 2007;49:95–103. doi: 10.1539/joh.49.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gough D.J., Levy D.E., Johnstone R.W., Clarke C.J. IFNgamma signaling: does it mean JAK-STAT? Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008;19:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Samsonov A., Zenser N., Zhang F., Zhang H., Fetter J., Malkov D. Tagging of genomic STAT3 and STAT1 with fluorescent proteins and insertion of a luciferase reporter in the cyclin D1 gene provides a modified A549 cell line to screen for selective STAT3 inhibitors. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Riemer C., Schultz J., Burwinkel M., Schwarz A., Mok S.W., Gultner S., Bamme T., Norley S., van Landeghem F., Lu B., Gerard C., Baier M. Accelerated prion replication in, but prolonged survival times of, prion-infected CXCR3-/- mice. J Virol. 2008;82:12464–12471. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01371-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Weering H.R., Boddeke H.W., Vinet J., Brouwer N., de Haas A.H., van Rooijen N., Thomsen A.R., Biber K.P. CXCL10/CXCR3 signaling in glia cells differentially affects NMDA-induced cell death in CA and DG neurons of the mouse hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2011;21:220–232. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krauthausen M., Kummer M.P., Zimmermann J., Reyes-Irisarri E., Terwel D., Bulic B., Heneka M.T., Muller M. CXCR3 promotes plaque formation and behavioral deficits in an Alzheimer's disease model. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:365–378. doi: 10.1172/JCI66771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Flynn G., Maru S., Loughlin J., Romero I.A., Male D. Regulation of chemokine receptor expression in human microglia and astrocytes. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;136:84–93. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li G., Veenstra A.A., Talahalli R.R., Wang X., Gubitosi-Klug R.A., Sheibani N., Kern T.S. Marrow-derived cells regulate the development of early diabetic retinopathy and tactile allodynia in mice. Diabetes. 2012;61:3294–3303. doi: 10.2337/db11-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakazawa T., Hisatomi T., Nakazawa C., Noda K., Maruyama K., She H., Matsubara A., Miyahara S., Nakao S., Yin Y., Benowitz L., Hafezi-Moghadam A., Miller J.W. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 mediates retinal detachment-induced photoreceptor apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2425–2430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608167104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Joussen A.M., Poulaki V., Mitsiades N., Cai W.Y., Suzuma I., Pak J., Ju S.T., Rook S.L., Esser P., Mitsiades C.S., Kirchhof B., Adamis A.P., Aiello L.P. Suppression of Fas-FasL-induced endothelial cell apoptosis prevents diabetic blood-retinal barrier breakdown in a model of streptozotocin-induced diabetes. FASEB J. 2003;17:76–78. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0157fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sui Y., Stehno-Bittel L., Li S., Loganathan R., Dhillon N.K., Pinson D., Nath A., Kolson D., Narayan O., Buch S. CXCL10-induced cell death in neurons: role of calcium dysregulation. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:957–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bodnar R.J., Yates C.C., Rodgers M.E., Du X., Wells A. IP-10 induces dissociation of newly formed blood vessels. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2064–2077. doi: 10.1242/jcs.048793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Palestro C.J. In vivo leukocyte labeling: the quest continues. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:332–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang W., Liu H., Rojas M., Caldwell R.W., Caldwell R.B. Anti-inflammatory therapy for diabetic retinopathy. Immunotherapy. 2011;3:609–628. doi: 10.2217/imt.11.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leon S., Yin Y., Nguyen J., Irwin N., Benowitz L.I. Lens injury stimulates axon regeneration in the mature rat optic nerve. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4615–4626. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04615.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yin Y., Henzl M.T., Lorber B., Nakazawa T., Thomas T.T., Jiang F., Langer R., Benowitz L.I. Oncomodulin is a macrophage-derived signal for axon regeneration in retinal ganglion cells. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:843–852. doi: 10.1038/nn1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baldwin K.T., Carbajal K.S., Segal B.M., Giger R.J. Neuroinflammation triggered by beta-glucan/dectin-1 signaling enables CNS axon regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:2581–2586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423221112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Aranda M.L., Dorfman D., Sande P.H., Rosenstein R.E. Experimental optic neuritis induced by the microinjection of lipopolysaccharide into the optic nerve. Exp Neurol. 2015;266:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Del Sole M.J., Sande P.H., Fernandez D.C., Sarmiento M.I., Aba M.A., Rosenstein R.E. Therapeutic benefit of melatonin in experimental feline uveitis. J Pineal Res. 2012;52:29–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Segel G.B., Halterman M.W., Lichtman M.A. The paradox of the neutrophil's role in tissue injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89:359–372. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0910538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kurimoto T., Yin Y., Habboub G., Gilbert H.Y., Li Y., Nakao S., Hafezi-Moghadam A., Benowitz L.I. Neutrophils express oncomodulin and promote optic nerve regeneration. J Neurosci. 2013;33:14816–14824. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5511-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nowling T.K., Gilkeson G.S. Mechanisms of tissue injury in lupus nephritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:250. doi: 10.1186/ar3528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ebner F.H., Mariotto S., Darra E., Suzuki H., Cavalieri E. Use of STAT1 inhibitors in the treatment of brain I/R injury and neurodegenerative diseases. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem. 2011;11:2–7. doi: 10.2174/187152411794961077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lavecchia A., Di Giovanni C., Novellino E. STAT-3 inhibitors: state of the art and new horizons for cancer treatment. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18:2359–2375. doi: 10.2174/092986711795843218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Leukocyte trafficking before TON. Noninvasive scanning laser ophthalmoscopy imaging shows there was minimal leukocyte attachment to retinal vessels before optic nerve crush.

Leukocyte trafficking at 9 hours after TON. Noninvasive scanning laser ophthalmoscopy imaging shows there were dramatic increases in leukocyte rolling, attachment, and infiltration in veins around the optic nerve head at 9 hours after optic nerve crush.

Genotype and phenotype analysis of representative offspring mice. A: Representative genotyping results of PCR analysis for wild type (WT; 1, only with 337-bp WT allele) and CXCR3 knockout (KO; 2, only with 485-bp KO allele) mice. B: Representative phenotyping results of GFP+ transgenic mice using blue light-emitting diode laser point.

Analysis of green fluorescent protein (GFP)–positive leukocytes in the blood of GFP bone marrow transplanted (BMT) mice. C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) mice were transplanted with bone marrow from GFP transgenic mice and 4 weeks later, blood was collected for flow cytometry. Representative histogram shows the percentage of GFP+ leukocytes in the blood of WT and BMT mice. n = 3 mice. Max, maximum.

Distribution of leukocytes and microglia in retinas after axonal injury. Wild-type mice received bone marrow transplant from green fluorescent protein (GFP) mice and 4 weeks later they were subjected to TON. At 24 hours after TON, retinas were fixed and labeled with Iba1 antibody (red) to identify microglia/monocytes. Green dots indicate GFP-positive cells. n = 3 mice. Scale bars = 50 μm. CON, control.

CD19 staining in the spleen. Spleen frozen section was used as a positive control for antibody against CD19 (red). DAPI (blue) stains nuclei. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Characterization of leukocytes in the TON retinas. Retinas were collected at 24 hours after TON and enzymatically dissociated to produce single cells for flow cytometric analysis. Cells were stained with antibodies against markers for leukocyte subtypes: CD45, CD3, CD11b, Ly6G, Ly6C, F4/80, and NK1.1. Plots of flow cytometric analyses are shown. Percentage indicates the proportion of CD45+ leukocytes, CD3+ T cells, CD11b+Ly6Ghigh neutrophils, CD11b+Ly6G− nonneutrophil myeloid cells, and NK1.1+ natural killer cells in total retinal cells from Control (Ctrl) and TON retinas. n = 14 mice.

Confirmation of purity of isolated primary RGCs. RGCs were isolated from wild-type pups at postnatal day 3 and stained with retinal ganglion cell marker Tuj1 antibody (green). DAPI (blue) stains nuclei. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Characterization of leukocytes isolated from bone marrow and blood. Leukocytes were isolated from bone marrow (A) and blood (B), and the populations and proportions of individual leukocyte subtypes were analyzed by flow cytometry. Plots for the percentage of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, γδ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, NK T cells (CD3+NK1.1+), B cells (CD19+), neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6Ghigh), and nonneutrophil myeloid cells [CD11b+Ly6G− (eg, monocytes and dendritic cells)] are shown. n = 8 mice. SSC, side scatter.

Confirmation of nontoxicity of vehicle used for AMG487 treatment. Wild-type mice were injected with vehicle (Veh, i.p.) twice a day for 7 days. A: Body weight of naive and vehicle-treated mice. B: Representative images of retinas labeled with Tuj1 antibody (green) at 7 days after vehicle injection. Graph represents the number of Tuj1-positive cells per field. C: Electroretinographic analysis for retinal neuronal function under scotopic conditions between naive and vehicle-treated groups after 7 days of treatment. Graphs represent average amplitudes of a- and b-waves and positive scotopic threshold response over a range of stimulus strengths. n = 4 mice (B and C). Scale bars = 50 μm.