Abstract

Infection of neutrophil precursors with Anaplasma phagocytophilum, the causative agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, results in downregulation of the gp91phox gene, a key component of NADPH oxidase. We now show that repression of gp91phox gene transcription is associated with reduced expression of interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1) and PU.1 in nuclear extracts of A. phagocytophilum-infected cells. Loss of PU.1 and IRF-1 correlated with increased binding of the repressor, CCAAT displacement protein (CDP), to the promoter of the gp91phox gene. Reduced protein expression of IRF-1 was observed with or without gamma interferon (IFN-γ) stimulation, and the defect in IFN-γ signaling was associated with diminished binding of phosphorylated Stat1 to the Stat1 binding element of the IRF-1 promoter. The diminished levels of activator proteins and enhanced binding of CDP account for the transcriptional inhibition of the gp91phox gene during A. phagocytophilum infection, providing evidence of the first molecular mechanism that a pathogen uses to alter the regulation of genes that contribute to an effective respiratory burst.

The agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, recently renamed Anaplasma phagocytophilum (3), is a vector-borne pathogen that is primarily transmitted by Ixodes scapularis ticks (45). A. phagocytophilum is an obligate intracellular bacterium with a tropism for neutrophils and has developed multiple strategies to survive within polymorphonuclear leukocytes. A. phagocytophilum infects both neutrophils and neutrophil precursors, and HL-60 cells have been used as an in vitro model to study this pathogen (4, 28, 29) One report suggested that neutrophils infected with A. phagocytophilum have delayed apoptosis (54) that may facilitate bacterial propagation in this short-lived cell. Other studies state that A. phagocytophilum infection may actually enhance apoptosis (12, 20). A. phagocytophilum-containing vacuoles also fail to mature into phagolysosomes (53), a mechanism that may protect the bacteria from harmful lytic enzymes. Finally, infection with A. phagocytophilum inhibits expression of the gp91phox gene, one of the key components of the respiratory burst (4, 43).

The respiratory burst is catalyzed by the enzyme NADPH oxidase and consists of membrane-associated components p22phox, gp91phox and Rap1A and several cytoplasmic components, including p40phox, p47phox, p67phox, and Rac2 (2, 19, 23). Dysfunction in the respiratory burst is associated with a deficiency of gp91phox, p22phox, p47phox, or p67phox (9, 41). A reduction in gp91phox gene levels following infection with A. phagocytophilum may also lead to a deficiency in the respiratory burst. Modulation of rac2 expression (5) may provide another strategy to alter superoxide production. One study suggested that the level of p22phox protein was also influenced by A. phagocytophilum infection (44). Alterations in p22phox gene expression have not been noted.

The gp91phox gene is a tightly regulated gene whose expression occurs through the competition of activator proteins with the repressor CCAAT displacement protein (CDP) (34, 38, 48). The minimal gp91phox gene promoter required for monocyte/macrophage expression has been localized to a region 450 bp from the start of transcription (47). The binding sites for several activator proteins, including interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1) and IRF-2 (15, 39), interferon consensus sequence binding protein (ICSBP) (15), the Ets family members Elf-1 and PU.1, CREB binding protein (CBP) (16, 52), CCAAT binding protein (CP1), and the binding increases during differentiation (BID)/YY1 factor (22) have all been localized to this region. Transcriptional activation of the gp91phox gene requires the formation of a complex between PU.1, IRF-1, ICSBP, and CBP (16). PU.1 binds to the gp91phox gene promoter in the absence of the other factors, followed by the recruitment of either ICSBP or IRF-1, resulting in the hematopoiesis-associated factor 1 (HAF1) complex (16). Complex formation between PU.1/Elf-1, IRF-1, and ICSBP further recruits CBP to the promoter, resulting in HAF1a (16).

These activators are not unique to the promoter of the gp91phox gene but are also shared by the p67phox and p47phox gene promoters (24). Lack of any of these proteins could adversely affect the transcription of all three genes. However, this is not always the case. For example, neutrophils from PU.1-deficient mice fail to produce gp91phox but are still able to express p47phox and p67phox (33), demonstrating the critical requirement of this activator protein for transcription of the gp91phox gene. Posttranslational modification of these proteins is also essential for DNA interaction (35, 46). Recently, Kautz and colleagues demonstrated that increased phosphatase activity can inhibit the interaction of ICSBP, IRF-1, and CBP with the gp91phox gene promoter and hence adversely affect transcription (24).

gp91phox is unique among the oxidase genes in that a specific repressor, CCAAT displacement protein (CDP), is involved in the regulation of its expression (34, 38). Several studies have identified six CDP binding sites within the 450-bp promoter region of the gp91phox gene (6). A site for another repressor, HoxA10, was also identified in the promoter region of the gp91phox and p67phox genes (14). Binding sites for specific AT-rich binding protein 1 (SATB1) have also been identified within the promoter of the gp91phox gene (18). Since the gp91phox gene is a major NADPH oxidase component whose transcription is adversely affected by A. phagocytophilum, we believe that this pathogen may alter the balance of proteins that may be essential for gp91phox gene transcription. To understand how A. phagocytophilum may be distinctly affecting the regulation of this gene, we investigated the gene expression and DNA interaction of several factors known to participate in regulation of the gp91phox gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell line.

The promyelocytic cell line HL-60 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Uninfected and A. phagocytophilum-infected cells were maintained as described (4).

RNA preparation and PCR.

mRNA was prepared from A. phagocytophilum-infected and uninfected HL-60 cells with an RNA isolation kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and analyzed by PCR. cDNA was prepared with the reverse transcription-PCR kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The gp91phox gene was detected as described (4). Primers specific to the hge-44 gene, 395-419 (5′-TCAAGACCAAGGGGTATTAGAGATAG-3′) and 920-898 (5′-GCCATCATGGAATTTCTTCGGG-3′) were based on the sequence of hge-44, a member of an A. phagocytophilum gene family that encodes immunodominant antigens (21, 55). A 584-bp fragment from the IRF-1 gene (GenBank accession number 002198) was amplified with primers IRF1a (5′-CAGCTCAGCTGTGCGAGTGTA-3′) and IRF-1b (5′-GTGAAGACACGCTGTAGACTCAGC-3′). A 494-bp fragment of PU.1 (GenBank accession number 006167) was amplified with primers PU.1f (5′-AGACTTCGCCGAGAACAACTTCA-3′) and PU.1r (5′-CTTCTGGTAGGTCATCTTCTTGCG-3′). β-Actin primers (5′-AGCGGGAAATCGTGCGTG-3′) and (5′-CAGGGTACATGGTGGTGCC-3′) were prepared and used in PCR amplification. β-Actin primers were used in a control PCR amplification to normalize the samples for equal cDNA concentrations.

Western blot.

Nuclear extracts were prepared from uninfected and 95% A. phagocytophilum-infected cells by the method of Dignam et al. (11) in the presence of protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Cooperation, Indianapolis, Ind.) and 1 mM each of the phosphatase inhibitors NaF and Na3VO4. From 5 to 10 μg of the nuclear extracts were run on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gel. Following transfer to nitrocellulose, the membrane was blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin in 0.1% Tween-20-containing Tris-buffered saline (T-TBS) for 2 h. The membranes were probed with antibodies to IRF-2, ICSBP, PU.1, Elf-1, IRF-1, and CDP (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, Calif.) for 1 h, followed by a 15-min wash and two 5-min washes. The blots were probed with a 1:2,000 dilution of a secondary goat antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase for 1 h. Following washing, the blots were developed with ECL substrate and exposed to X-ray film.

DNA pulldown assay.

The DNA pulldown assay was performed according to the protocol of Ting et al. (50). Briefly, 200 μg of nuclear extracts was cleared with 10 μl of streptavidin-agarose beads, followed by overnight incubation with 100 ng of an annealed biotinylated HAF site containing the −72 to −43 (5′-AGGGCTGCTGTTTTCATTTCCTCATTGGAA-3′) fragment of the gp91phox gene promoter at 4°C. Fresh streptavidin beads were added for an additional hour and then collected and washed. Bound proteins were eluted by boiling in Laemmli buffer, followed by loading onto a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel. Western blots for precipitated proteins were performed.

EMSA.

The gel shift assay was performed with the Lightshift chemiluminescent electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). Complementary biotinylated oligonucleotides consisting of the gp91phox gene HAF site fragment, −32 to −69 (5′-CTGCTGTTTTCATTTCCTCATTGGAAGAAGAAGCATAG-3′) and the CDP binding sites, CDPα (5′-GCTTTTCAGTTGACCAATATTAGCCAATTTC-3′), CDPβ (5′-TTTGTAGTTGTTGAGGTTTAAAGATTTAAGTTTGTTATGGATGCAA-3′), CDPδ (5′-TTTAATGTGTTTTACCCAGCACGAAGTCATGTCTAGTTGAGTGGCTTAAA-3′), CDPγ (5′-AGAAATTGGTTTCATTTTCCACTATGTTTAATTGTGACTGGATCATTATA-3′), and CDPɛ (5′-TGATAAAAGAAAAGGAAACCGATTGCCCCAGGGCTGCTGTTTCATTTC-3′) as described by Catt et al. (6), Stat1 binding element from the IRF-1 promoter (SBE-IRF-1) (5′-GATCGATTTCCCCGAAATGA-3′) as described by Coccia et al. (48), were annealed and then loaded onto a 2% agarose gel. The DNA was extracted with the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). The isolated fragment was added to a 20-μl reaction mix consisting of 5 μg of nuclear extract, DNA binding buffer, glycerol, MgCl2, NP-40, and poly(dI · dC) in concentrations based on manufacturer's recommendations. The reaction was incubated for 20 min at room temperature, followed by loading onto a 5% native polyacrylamide gel. The gel was run with 0.5% Tris-Borate-EDTA (TBE) and processed according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

For antibody blocking, 5 to 10 μg of anti-PU.1 (T-21) (Santa Cruz Biotech.) was either incubated with the extract DNA/complex or incubated with extracts for 1 h on ice followed by addition of the labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide for an additional 15 min. Competition with unlabeled double-stranded CDP oligonucleotide (5′-ACCCAATGATTATTAGCCAATTTCTGA-3′) mutant (Δ) CDP oligonucleotide (5′-ACCCAATGGCCGTTAGCCAATTTCTGA-3′), ets (5′-GGGCTGCTTGAGGAAGTATAAGAAT-3′), IRF-1 (5′-GGAAGCGAAAATGAAATTGACT-3′) (Santa Cruz Biotech.), a high-affinity binding site from the promoter of neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) (5′-CTTTGAAAATCGAACCGAATCTAAAAT-3′) (26, 51), was performed as stated above with the use of excess unlabeled fragments instead of antibodies.

Stable transfection of the gp91phox gene reporter construct.

The bp −209 to +12 promoter fragment of the gp91phox gene was amplified with gp91D (5′-GTGACTGGATCATTATAGACC-3′) and gp91B (5′-CATGGTGGCAGAGGTTGAATGT-3′). The isolated fragment was cloned into the pBlue-TOPO reporter plasmid containing the promoterless lacZ gene (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). HL-60 cells were transfected with the DMRIE-C reagent (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) based on the manufacturer's recommendations. Stable transfectants were obtained following two rounds of selection and maintained in 1.5 mg of G418 per ml. Resistant cells were infected with A. phagocytophilum for 48 to 96 h, and β-galactosidase activity was determined with the β-galactosidase reporter assay kit (Roche Cooperation, Indianapolis, Ind.). As a control for β-galactosidase activity, transfection was also performed with the pSV-βgal (Promega, Madison, Wis.) containing the lacZ gene under the control of the simian virus 40 early promoter and enhancer.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation.

The chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed by the method of Li et al. (32) with some modifications; 107 HL-60 cells or A. phagocytophilum-infected HL-60 cells stimulated with either 100 U of human IFN-γ (BD Bioscience, San Jose, Calif.) per ml or 10 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) were collected in 10 ml of medium and placed in 100-mm tissue culture plates. The cells were fixed with a final concentration of 2% formaldehyde for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were collected and washed several times in cold 1x phosphate-buffered saline, followed by sonication in chromatin immunoprecipitation buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 140 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 0.1% deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with protease inhibitors.

Following centrifugation, the supernatant was collected and stored until immunoprecipitation. The protein concentration was determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent. Equal protein concentrations of the supernatants were incubated overnight with an antibody to CDP (Santa Cruz Biotech.). The antibody/protein-DNA complexes were incubated with protein A/G agarose beads for an additional 1 h, followed by centrifugation and collection of the bound protein-DNA complexes. The beads were washed several times with chromatin immunoprecipitation buffer followed by incubation with elution buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3 and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) and heated for 4 h at 65°C. Supernatants were then collected and subjected to DNA purification with the Qiagen PCR purification kit. The DNA was eluted in 30 to 50 μl and used in PCR amplification with primer gp91B, −7 to +15 (5′-CATGGTGGCAGAGGTTGAATGT-3′) and gp91D, −209 to −189 (5′-GTGACTGGATCATTATAGACC-3′) specific to the gp91phox gene promoter.

RESULTS

Infection with A. phagocytophilum alters gp91phox gene promoter activity.

Infection of HL-60 cells with A. phagocytophilum results in reduced transcription and expression of the gp91phox gene (4). The expression of the other major subunits of NADPH oxidase, p47phox, p67phox, and p22phox, remains unaffected (4), suggesting that A. phagocytophilum infection specifically influences transcription of the gp91phox gene. The −450 to +12 region of the gp91phox gene promoter has been shown to be sufficient for induction of the gp91phox gene in monocytes (47). The interacting proteins have been characterized, and several of their binding sites are contained within the proximal 100 bp of the promoter (15). We therefore investigated the effect of A. phagocytophilum infection on the proximal gp91phox gene promoter region.

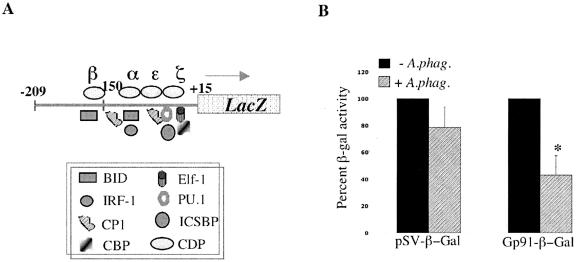

HL-60 cells expressing a promoter fusion consisting of a 225-bp gp91phox gene-proximal promoter fused to the promoterless lacZ gene (Fig. 1A) were infected with A. phagocytophilum, and cell extracts were analyzed for β-galactosidase activity. The results show that A. phagocytophilum infection had little effect on the β-galactosidase activity of the control pSV-β-gal vector while significantly (P < 0.01) reducing the promoter activity of the gp91phox gene-proximal promoter by 50% compared to the activity in uninfected HL-60 cells (Fig. 1B). This finding led us to investigate the effects of A. phagocytophilum infection on the proteins that interact with the proximal promoter of the gp91phox gene.

FIG. 1.

A. phagocytophilum infection alters the activity of the the gp91phox promoter. A) Schematic diagram of the proximal promoter fragment from the gp91phox gene promoter fused to the promoterless lacZ gene. The CDP repressor (δ, γ, β, α, ɛ, and ζ) and activator (BID/YY1, IRF-1, CP1, CBP, Elf, PU.1, and ICSBP) protein binding regions are depicted. B) Promoter activity was measured by β-galactosidase activity in the presence and absence of A. phagocytophilum. β-Galactosidase activity is presented as a percentage of the activity in uninfected cells. As a control, the β-galactosidase activity of the control plasmid pSV-βgal was determined in the presence and absence of infection. The asterisk denotes statistical significance (P < 0.01) of triplicate readings as determined by Student's t test.

Infection with A. phagocytophilum alters the binding of proteins to the promoter of the gp91phox gene.

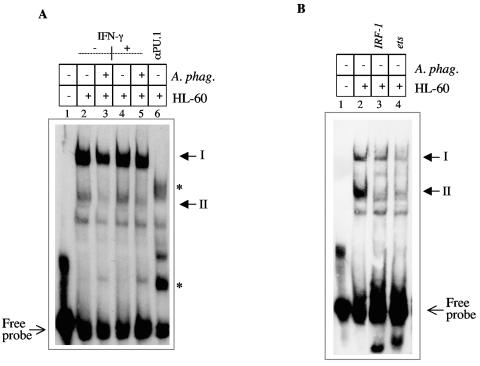

Since the proteins that interact with the gp91phox gene promoter have, for the most part, been identified, we assessed the effect of A. phagocytophilum infection on the interaction of these molecules. We focused on a fragment of the proximal promoter called the hematopoiesis-associated factor 1 (HAF1) (16, 17) site, which contains binding sites for IRF-1, PU.1, Elf-1, ICSBP, and CBP (15, 16, 52). Using nuclear extracts from uninfected and A. phagocytophilum-infected cells, we observed differential binding of proteins to the gp91phox gene promoter HAF1 site (Fig. 2A). We observed several complexes similar to what Kautz and colleagues described (24). The profile of the band shifts resulting from A. phagocytophilum-infected extracts was similar to that observed with extracts from uninfected HL-60 cells, but the intensity of complex II differed between the extracts (Fig. 2A). A. phagocytophilum-infected and uninfected HL-60 cells had similar intensities at complex I, while complex II was reduced in the infected extracts (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 3). Incubation of extracts with an antibody to PU.1 resulted in disruption of both complexes (Fig. 2A, lane 6), suggesting that PU.1 is a component of both complexes. In addition, two new complexes were observed upon treatment with this antibody. The slower-migrating complex may contain CP1, while the faster-migrating complex consists of monomeric PU.1, as previously described (15). Treatment of extracts with excess unlabeled IRF-1 or ets oligonucleotide (Fig. 2B, lanes 4 and 3, respectively) resulted in loss of both complexes. This result is consistent with the participation of IRF-1 and PU.1 in the formation of complexes I and II.

FIG. 2.

A) A. phagocytophilum infection alters protein binding to the gp91phox gene HAF site. Nuclear extracts from uninfected and A. phagocytophilum-infected HL-60 cells were incubated with the HAF site fragment (bp −32 to −69) from the gp91phox gene promoter. Lane 1 contains no extract, lanes 2, 4, and 6 contain extracts from uninfected HL-60 cells, lanes 3 and 5 contain extracts from A. phagocytophilum-infected cells. Lanes 4 and 5 contain extracts stimulated with IFN-γ for 48 h. In lane 6, extracts were incubated with an antibody to PU.1 for 1 h following addition of the labeled fragment. Asterisks denote complexes resulting from PU.1 treatment. B) Extracts from uninfected HL-60 cells (lanes 2, 3, and 4) were incubated with the HAF site fragment. Excess unlabeled oligonucleotide containing either the IRF-1 (lane 3) or ets (lane 4) binding site was incubated with the extracts for 1 h prior to addition of the labeled HAF site oligonucleotide.

Gamma interferon (IFN-γ) can stimulate cell differentiation and generation of the respiratory burst from phagocytes (13, 27) and can specifically regulate the expression of the gp91phox gene by increasing the rate of transcription (8). Banerjee showed that treatment of A. phagocytophilum-infected cells with IFN-γ was able to partially restore gp91phox gene expression (4). As expected, A. phagocytophilum-infected cells stimulated with IFN-γ have reduced complex II compared with uninfected cells that were stimulated with IFN-γ (Fig. 2A, lanes 4 and 5). IFN-γ stimulation did not alter the band intensity of complex I (HAF1a) and complex II (HAF1) when uninfected unstimulated cells were compared to uninfected cells (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 4). This result is consistent with the results of Eklund et al., who demonstrated that despite the apparent effect of IFN-γ on transcription of the gp91phox gene, any effect on protein binding could not be detected in EMSA (15). Altered formation of complex II during infection suggests an adverse effect on the proteins that participate in the formation of this complex.

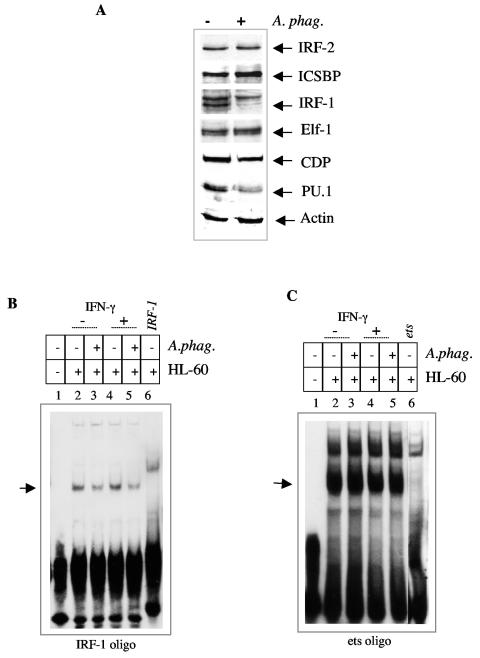

A. phagocytophilum alters the protein concentration of IRF-1 and PU.1.

We next examined the effect of A. phagocytophilum infection on the levels of activator and repressor proteins that interact with the gp91phox gene promoter. In order for the gp91phox gene to be expressed, the repressor-promoter interaction must be inhibited by activator proteins (38, 48). Western blotting demonstrated that ICSBP, Elf-1, and IRF-2 levels were not adversely affected by A. phagocytophilum infection (Fig. 3A). Compared to nuclear extracts from uninfected cells, A. phagocytophilum-infected HL-60 cells did not show elevation of the repressor CDP (Fig. 3A). Among the activators, IRF-1 and PU.1 protein levels were reduced and scarcely detectable in nuclear extracts from A. phagocytophilum-infected HL-60 cells (Fig. 3A). A decrease in the IRF-1 level during infection with A. phagocytophilum is consistent with altered binding to the IRF-1 consensus binding site (Fig. 3B). However, altered binding to the consensus ets oligonucleotide during infection is not apparent (Fig. 3C). This result implies that despite the reduction in PU.1 protein levels, there is a sufficient amount of protein to bind the promoter. These data are consistent with the resistance of complex I to alteration by A. phagocytophilum infection.

FIG. 3.

A. phagocytophilum infection reduces the protein levels of IRF-1 and PU.1. A) Western blot of nuclear extracts from A. phagocytophilum-infected and uninfected HL-60 cells probed with antibodies to IRF-2, ICSBP, Elf-1, IRF-1, PU.1, CDP, and actin. B) A. phagocytophilum infection alters binding to the IRF-1 binding site. Extracts from uninfected (lanes 2, 4, and 6) and A. phagocytophilum-infected (lanes 3 and 5) HL-60 cells were incubated with a labeled IRF-1 oligonucleotide. The extracts in lanes 4 and 5 were obtained from cells stimulated with IFN-γ for 48 h. Excess unlabeled oligonucleotide was added to the extracts in lane 6. C) A. phagocytophilum infection does not alter binding to the ets binding site. Extracts from uninfected (lanes 2, 4, and 6) and A. phagocytophilum-infected (lanes 3 and 5) HL-60 cells were incubated with the ets binding site oligonucleotide. The extracts in lanes 4 and 5 were obtained from cells stimulated with IFN-γ for 48 h. Excess unlabeled oligonucleotide was added to lane 6.

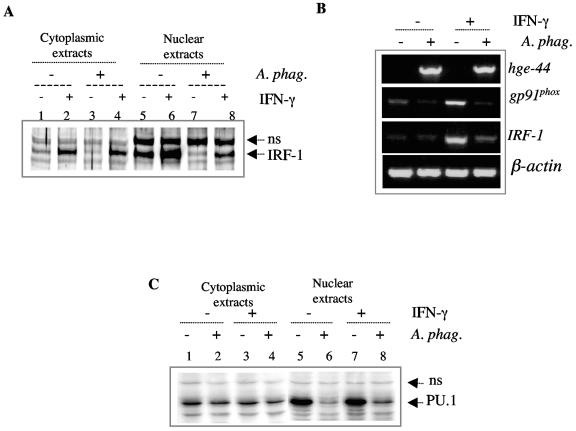

The reduction in IRF-1 protein level is more apparent in the nuclear fraction than the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 4A). Cytoplasmic extracts from uninfected and infected cells contained similar levels of IRF-1 (compare lanes 1 and 3 of Fig. 4A), while the nuclear fraction of the infected cells had lower concentrations of IRF-1 (compare lanes 5 and 7 of Fig. 4A). Stimulation with IFN-γ, which can upregulate expression of IRF-1 (42), resulted in elevated levels of IRF-1 in both uninfected and A. phagocytophilum-infected cell extracts (Fig. 4, compare lanes 5 and 6 and lanes 7 and 8). A. phagocytophilum infection demonstrated an ability to inhibit IRF-1 expression even in the presence of IFN-γ stimulation (Fig. 4A, lanes 6 and 8).

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of IRF-1 and PU.1 by A. phagocytophilum. (A) Western blot of cytoplasmic (lanes 1 through 4) and nuclear (lanes 5 through 8) extracts from IFN-γ-stimulated (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) and unstimulated (1, 3, 5, and 7) A. phagocytophilum-infected (lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8) and uninfected (lanes 1, 2, 5, and 6) HL-60 cells probed with an antibody to IRF-1. (B) Reverse transcription-PCR of mRNA from uninfected and A. phagocytophilum-infected HL-60 cells to assess expression of the IRF-1 and gp91phox genes. PCR for hge-44 was performed to verify infection with A. phagocytophilum. β-Actin PCR was also performed as a control to verify that similar concentrations of mRNA were used. NS, nonspecific antibody staining. (C) Western blot of cytoplasmic (lanes 1 through 4) and nuclear (lanes 5 through 8) extracts from IFN-γ-stimulated (lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8) and unstimulated (lanes 1, 2, 5, and 6) A. phagocytophilum-infected (2, 4, 6, and 8) and uninfected (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) HL-60 cells probed with antibodies to PU.1. NS, nonspecific antibody staining.

We then assessed the effect of A. phagocytophilum infection on the transcription of IRF-1. RNA from A. phagocytophilum-infected cells demonstrated reduced expression of IRF-1 (Fig. 4B). Similar to the protein level, stimulation with IFN-γ upregulated expression of IRF-1 in both uninfected and infected cells, but expression levels in the infected samples were still reduced. The transcriptional inhibition observed with IRF-1 correlated with transcriptional inhibition of the gp91phox gene (Fig. 4B).

We also investigated the effect of infection on the expression of PU.1. Similar to IRF-1, the protein concentration of PU.1 was decreased in nuclear extracts from A. phagocytophilum-infected cells (Fig. 4C, compare lanes 5 and 6 and lanes 7 and 8). This effect was evident whether or not the cells had been stimulated with IFN-γ. The cytoplasmic extracts from both the infected and uninfected cells contained comparable levels of PU.1 (Fig. 4C, compare lanes 1 and 2 and lanes 3 and 4), demonstrating that the effect was specific for the nuclear fraction. PU.1 message was not altered by infection.

A. phagocytophilum infection does not alter Stat1 phosphorylation.

Previous work by Lee and colleagues showed that Ehrlichia chaffeensis, which infects macrophages, inhibits Jak/Stat activation (31). IFN-γ stimulation utilizes the Jak/Stat1 signaling pathway and therefore may be defective in A. phagocytophilum-infected cells. We investigated the effect of infection on Stat1 phosphorylation as a possible mechanism for reduced expression of IRF-1 and the gp91phox gene. Analysis of Stat1 phosphorylation revealed that infection with A. phagocytophilum did not inhibit IFN-γ-induced phosphorylation of Stat1 (Fig. 5A). The cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts appear to have similar levels of phosphorylated Stat1 in the presence and absence of A. phagocytophilum infection (Fig. 5A). Therefore, we conclude that the IFN-γ-induced signaling cascade leading to Stat1 phosphorylation was not adversely affected by A. phagocytophilum infection.

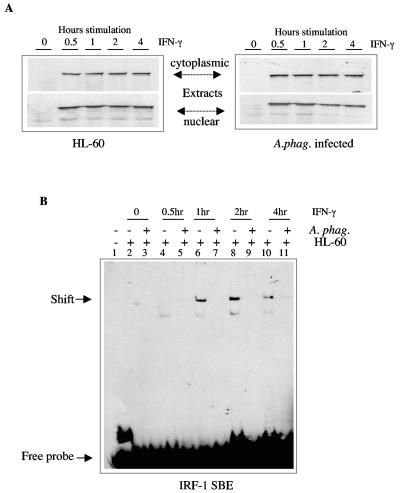

FIG. 5.

A. phagocytophilum infection does not alter phosphorylation of Stat1 but reduces Stat1 binding to the Stat1-binding element of IRF-1. A) Cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts from uninfected and A. phagocytophilum-infected cells stimulated with 500 U of IFN-γ per ml for 0.5, 1, 2, or 4 h were probed with an antibody to phosphorylated Stat1 (pStat1). B) Nuclear extracts from uninfected and A. phagocytophilum-infected, unstimulated and IFN-γ-stimulated cells were analyzed by EMSA. Lane 1 has no protein. Lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 contain extracts from HL-60 cells. Lanes 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 contain extracts from A. phagocytophilum-infected cells.

A. phagocytophilum infection alters the binding of phosphorylated Stat1 to the Stat1 binding element of IRF-1.

We analyzed the effect of A. phagocytophilum infection on the interaction of phosphorylated Stat1 with the promoter of IRF-1. Following IFN-γ stimulation, phosphorylated Stat1 forms a homodimer and interacts with the IFN-γ-activated site element (10). Recently, Stat1 and IRF-1 were demonstrated to cooperate in the IFN-γ-activated transcription of the gp91phox gene (30). Since phosphorylation of Stat1 was not affected by infection and phosphorylated Stat1 is important in the regulation of IRF-1 and the gp91phox gene (30), infection could affect phosphorylated Stat1 at the level of binding, resulting in the defect observed with expression of both genes. Following IFN-γ stimulation, phosphorylated Stat1 homodimers can interact with the Stat1 binding element in the IRF-1 promoter, resulting in elevated expression (50).

Using the extracts from A. phagocytophilum-infected and uninfected cells stimulated with IFN-γ for various times, we observed differential binding to the Stat1-binding element of IRF-1 (Fig. 5B). From the earliest to the latest time point observed, A. phagocytophilum infection inhibited binding of phosphorylated Stat1 to the Stat1-binding element of IRF-1 (Fig. 5B). The nuclear extracts are the same as those shown in Fig. 5A, which clearly shows similar levels of phosphorylated Stat1 in the extracts. This result indicates that even in the presence of IFN-γ stimulation and phosphorylation of Stat1, binding to the Stat1-binding element of IRF-1 is severely affected by A. phagocytophilum infection.

A. phagocytophilum infection reduces transcription complex formation at the promoter of the gp91phox gene.

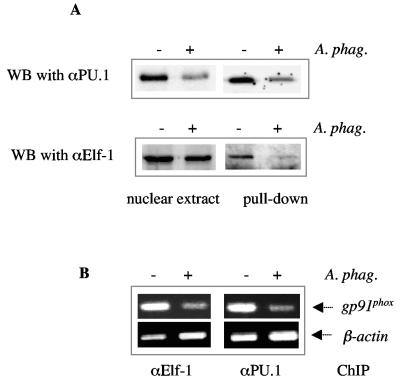

We also investigated the effect of infection on the formation of the HAF complex. PU.1 is thought to bind to the proximal promoter and recruit other activators to the region (16). Reduced levels of PU.1 and IRF-1 suggest that activator complex formation may be modulated during A. phagocytophilum infection. Immunoprecipitation with a DNA pulldown assay showed that binding of PU.1 to the HAF site fragment was reduced following exposure to A. phagocytophilum (Fig. 6A), consistent with the reduced levels of PU.1 detected in the nuclear extract by Western blot. In contrast, similar levels of Elf-1 were detected by immunoblot in nuclear extracts from both uninfected and infected cells, but the level of Elf-1 bound to the HAF site was reduced (Fig. 6A). This suggests that Elf-1 does not interact efficiently with the gp91phox gene promoter HAF site during A. phagocytophilum infection. This hypothesis is supported by the chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. The Elf-1 antibody immunoprecipitated less gp91phox gene promoter fragment containing the HAF site from lysates of A. phagocytophilum-infected cells than from uninfected cells (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Inefficient binding of Elf-1 occurs in the presence of A. phagocytophilum infection. A) DNA pulldown assay. Nuclear extracts from infected and uninfected cells were reacted with a biotinylated fragment containing the HAF site, followed by analysis of bound proteins by Western blot (WB). Nuclear extracts were run as a control for the level of total protein in the extracts. The blot was probed with an antibody to either PU.1 or Elf-1. B) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. DNA-protein complexes from uninfected and A. phagocytophilum-infected cells were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an antibody to either PU.1 or Elf-1. The bound DNA was amplified with primers specific to the gp91phox gene promoter. β-Actin was also assessed as a measure of nonspecific binding DNA.

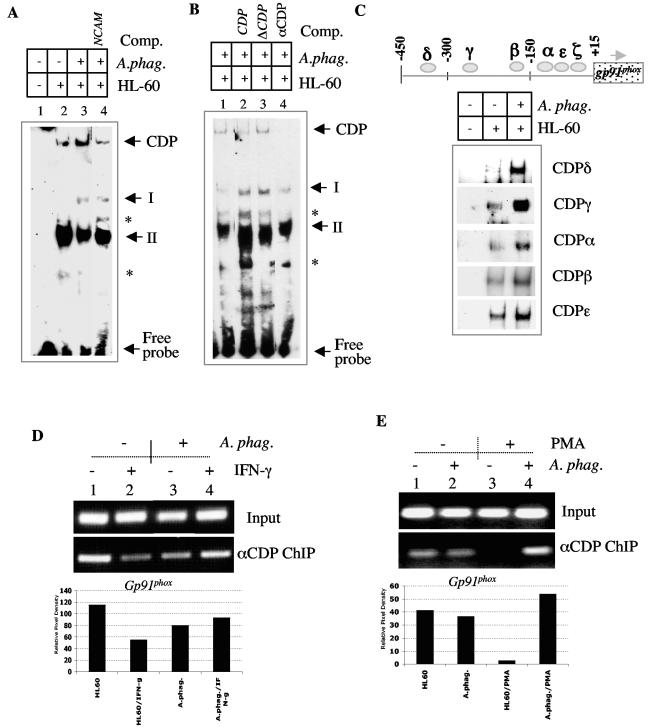

Enhanced interaction of CCAAT displacement protein (CDP) during A. phagocytophilum infection.

We next analyzed the binding of the CDP repressor to the promoter of the gp91phox gene. Lower levels of PU.1 and IRF-1 along with reduced formation of complex II imply that there may be reduced competition of CDP for the promoter of the gp91phox gene, resulting in elevated CDP binding. To investigate this hypothesis, we examined the interaction of CDP with the gp91phox gene promoter in the presence of A. phagocytophilum infection (Fig. 7). We observed a slower-migrating complex which was not as apparent in the extracts from the uninfected cells. This slow-migrating band was reduced with the unlabeled NCAM oligonucleotide containing a high-affinity CDP binding site (51) (Fig. 7A, lane 4) as well as an oligonucleotide containing a consensus CDP binding site but not a mutated form of this site (Fig. 7B, lanes 2 and 3). In the presence of the CDP oligonucleotide, complexes I and II were more apparent, suggesting elevated binding of activators to the HAF site when CDP is inhibited by a specific oligonucleotide. Treatment of infected extracts with an antibody to CDP prevented the formation of the slower-migrating complex, further implicating the presence of CDP in this complex.

FIG. 7.

A. phagocytophilum enhances the interaction of CDP with the gp91phox gene promoter. A) Extracts from uninfected and A. phagocytophilum-infected cells were incubated with a HAF site fragment of the gp91phox gene promoter. The gel was run for a longer period in order to visualize a slow-migrating CDP-containing complex. Lanes: 1, no extract; 2, lysate from uninfected HL-60 cells; 3 and 4, lysates from A. phagocytophilum-infected HL-60 cells. Unlabeled NCAM oligonucleotide was added to lane 4. B) Extracts from A. phagocytophilum-infected cells were incubated with either excess cold CDP binding site oligonucleotide (lane 2), a mutated CDP binding site oligonucleotide (lane 3), or an antibody to CDP (lane 4). The CDP complex is denoted along with complexes upregulated by treatment with competitors (asterisks). C) EMSA was performed with nuclear extracts from A. phagocytophilum-infected and uninfected HL-60 cells reacted with labeled complementary oligonucleotides containing five CDP binding sites within the gp91phox gene promoter. D) The chromatin immunoprecipitation assay was performed with uninfected (lanes 1 and 3) and A. phagocytophilum-infected (lanes 2 and 4) HL-60 cells unstimulated (lanes 1 and 3) or stimulated (lanes 2 and 4) with IFN-γ. The bar graph represents the relative CDP-bound gp91phox gene promoter compared to the levels in the input sample. E) The chromatin immunoprecipitation assay was performed with uninfected (lanes 1 and 3) and A. phagocytophilum-infected (lanes 2 and 4) HL-60 cells untreated (lanes 1 and 2) or treated (lanes 3 and 4) with PMA. The bar graph represents the relative CDP-bound gp91phox gene promoter compared to the levels in the input sample.

Since the HAF binding site oligonucleotide does not contain an intact CDPζ binding site, we also assessed binding to the other CDP binding sites within the proximal the gp91phox gene promoter. Enhanced binding of CDP could be detected at several of the CDP binding sites depicted in Fig. 7C. The CDP δ, γ, α, β, and ɛ sites all showed elevated binding of CDP in the presence of A. phagocytophilum infection (Fig. 7C). This result implies that during infection, elevated binding of CDP can occur and may be the result of inefficient activator complex formation necessary for competition of the repressor. An enhancement in CDP binding was also observed with the chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 7D and E). In the presence of IFN-γ, less CDP-bound promoter was detected in the uninfected HL-60 cells (Fig. 7D, compare lanes 1 and 2), consistent with the upregulation of gp91phox gene expression by this cytokine. However, in the presence of A. phagocytophilum infection, the binding of CDP was maintained in the presence of IFN-γ stimulation (Fig. 7D, compare lanes 3 and 4).

Differentiation of HL-60 cells with PMA is known to reduce the binding ability of CDP (40). To further confirm the effect of A. phagocytophilum on the interaction of CDP with the promoter of the gp91phox gene, uninfected and A. phagocytophilum-infected cells were treated with PMA for 48 h. We observed that PMA could reduce the interaction of CDP with the promoter of the gp91phox gene (Fig. 7E, compare lanes 1 and 3). However, in the presence of A. phagocytophilum, a reduction in CDP interaction is not detected (Fig. 7E, compare lanes 2 and 4). Taken together, these data suggest that during A. phagocytophilum infection, binding of the repressor CDP is maintained, resulting in repression of the gp91phox gene.

DISCUSSION

A. phagocytophilum infection results in repression of the gp91phox gene.

In this report we demonstrated that the inhibitory effect of A. phagocytophilum was on the promoter of the gp91phox gene and showed a correlation between altered expression of the gp91phox gene and reduced levels of PU.1 and IRF-1 proteins in nuclear extracts of A. phagocytophilum-infected cells. Concomitant with decreased protein levels of IRF-1 and PU.1 was elevated binding of CCAAT displacement protein to the gp91phox gene promoter, suggesting a role for both the activator proteins and the repressor in A. phagocytophilum-mediated repression of the gp91phox gene.

Studies show that regulation of the gp91phox gene is a result of competition between the repressor and activator proteins (38). During differentiation, activator proteins may be expressed or modified, which can lead to DNA interaction and expression of the gp91phox gene (48). For IFN-γ-dependent expression of the gp91phox gene, PU.1 is thought to be the first to bind to the promoter, followed by recruitment of IRF-1 or ICSBP. CBP is then recruited to the ICSBP-PU.1-IRF-1 complex (16). Increased transcription of the gp91phox gene during differentiation is accompanied by reduced binding of the CDP repressor. In gp91phox gene-nonexpressing cells, elevated binding of the repressor is detected (48).

IRF-1 and PU.1 are essential for expression of the gp91phox gene (15, 49). Lack of either of these molecules eliminates expression of the gp91phox gene (1, 15). Eklund and colleagues described the formation of several complexes resulting from interaction of U937 cell extracts with the gp91phox gene promoter (16). Our EMSA results indicate a similar pattern of shifts with extracts from HL-60 cells, but the intensities of the complexes varied between nuclear extracts from uninfected and A. phagocytophilum-infected cells. Extracts from A. phagocytophilum-infected cells resulted in less complex II (HAF1), suggesting deficient complex formation between either PU.1 and IRF-1 or PU.1 and ICSBP. ICSBP levels were not affected by infection, pointing to a defect in either PU.1 or IRF-1. Levels of both of these proteins are reduced during infection, suggesting that lower levels of PU.1 and IRF-1 in the infected cells may account for the reduced complex formation. Moreover, IFN-γ was unable to influence the formation of either complex I or II. Despite an effect on the formation of complex II, the formation of complex I was not adversely affected by infection, even though both complexes contain PU.1 and IRF-1. Treatment with excess unlabeled ets and IRF-1 oligonucleotides showed that PU.1 and IRF-1 participated in the formation of both complexes I and II. Complex II was more sensitive to treatment with the IRF-1 oligonucleotide, suggesting that complex I may contain other proteins, such as ICSBP and CBP, that are not adversely affected by infection, possibly accounting for these differences.

PU.1 and IRF-1 are not unique to the regulation of the gp91phox gene. Both of these molecules participate in the regulation of the p47phox and p67phox genes (16, 33). Expression of these molecules was not affected by infection (4). This is not surprising because PU.1-deficient mice can produce p47phox and p67phox but not gp91phox, indicating a more critical role for PU.1 in regulation of the gp91phox gene (1). In the case of p67phox, complex formation between IRF-1, ICSBP, PU.1, and CBP is critical for expression (16). The formation of the HAF1 complex (II) is also required for expression of the gp91phox gene (16).

DNA pulldown assays revealed that A. phagocytophilum infection could alter the interaction of Elf-1 with the promoter of the gp91phox gene. Therefore, lack of complex formation during A. phagocytophilum infection should affect not only gp91phox but p67phox as well. Our previous data (4) suggest that this is not the case, implying that despite the decrease in PU.1 and IRF-1, there is a sufficient concentration of these proteins for expression of p67phox and p47phox but not gp91phox. Therefore, the unique effect of A. phagocytophilum may reside with the repressor protein, which binds to the promoter of the gp91phox gene and not the promoter of the genes for other oxidase components.

The effect of A. phagocytophilum was not eliminated by stimulation with IFN-γ. Western blotting and RT-PCR showed altered expression of IRF-1 in the presence of A. phagocytophilum infection. IRF-1 was affected even in the presence of IFN-γ stimulation, which is known to induce the expression of both the IRF-1 and gp91phox genes. We observed that stimulation with IFN-γ, while able to increase the expression of IRF-1, was unable to restore the expression of IRF-1 to the level observed in uninfected cells, suggesting that IFN-γ signaling leading to enhanced expression of IRF-1 was being affected by A. phagocytophilum infection. We observed that IFN-γ signaling was intact up to the point of Stat1 phosphorylation but that binding of phosphorylated Stat1 was impaired during infection. This reduced binding may account for decreased expression of IRF-1 mRNA and hence indirectly affect the downstream expression of the gp91phox gene. Based on the data of Kumatori et al. (30), lack of phosphorylated Stat1 binding to the gp91phox promoter during A. phagocytophilum infection could directly affect the IFN-γ-induced expression of the gp91phox gene. This could be the result of binding of an inhibitor, such as protein inhibitor of activated Stats 1 (36), which can alter the binding of phosphorylated Stat1 to the promoter of IRF-1 (7, 25).

In conjunction with reduced PU.1 and IRF-1, we observed elevated binding of CDP. During A. phagocytophilum infection, the concentration of CDP was not elevated. However, increased binding to several CDP binding sites was detected. This suggests increased binding of the repressor to the promoter of the gp91phox gene during A. phagocytophilum infection. Chromatin immunoprecipitation demonstrated that with either IFN-γ stimulation or differentiation with PMA, binding of CDP was reduced by approximately 40 and 50%, respectively, in the uninfected cells compared with the A. phagocytophilum-infected cells. This finding suggests that CDP may not face competition for the promoter during infection with A. phagocytophilum. Since CDP actively represses the gp91phox gene promoter, lack of competition by activator proteins may contribute to the enhanced binding, resulting in the gene repression observed with A. phagocytophilum infection.

A second homeoprotein, SATB1, was shown to interact with the promoter of the gp91phox gene (18). Expression of SATB1 is downregulated during differentiation, which correlates with elevated expression of gp91phox. The binding activity of CDP is downregulated during differentiation, while the protein levels are not altered. Therefore, the regulation of CDP differs from the regulation of SATB1. Modulation of SATB1 binding could account of inhibition of the the gp91phox as well as the inhibition of the promoter fusion presented in Fig. 1. Our results support a role for CDP in the A. phagocytophilum-mediated repression of gp91phox. EMSA and chromatin immunoprecipitation assays show elevated binding of CDP to the promoter of gp91phox. SATB1 interacts with the CDPα site within the proximal 450 bp of the gp91phox gene promoter. Elevated binding of CDP is observed with all the CDP sites within the 450-bp proximal promoter, including the CDPα. SATB1 and CDP can interact with each other at their DNA binding domains, resulting in the inability of either protein to efficiently bind DNA (37). Persistent binding of CDP to the promoter of the gp91phox gene during infection supports a role of CDP in infection-induced repression.

In conclusion, A. phagocytophilum infection of neutrophils and neutrophil precursors results in decreased expression of the gp91phox gene (4). A similar finding was reported for rac2, another protein important to the respiratory burst (5). Using the HL-60 promyelocyte cell line, we now show a mechanism of A. phagocytophilum-mediated inhibition of the gp91phox gene. Based on the findings of our present study, we hypothesize that in the presence of A. phagocytophilum infection, nuclear protein levels of PU.1 and IRF-1 are severely reduced, resulting in less competition with the repressor CDP for binding to the gp91phox gene promoter. In addition, we show that A. phagocytophilum may influence IFN-γ-stimulated IRF-1 expression by altering the binding of phosphorylated Stat1 to the Stat1-binding element of IRF-1. Enhanced repression leads to a diminished level of gp91phox gene transcription, which may lead to a deficiency in NADPH oxidase activity. These studies are the first to demonstrate the ability of a pathogen to manipulate the promoter activity of the gp91phox gene, thereby potentially influencing the respiratory burst to facilitate microbial survival.

Acknowledgments

We thank Juan Anguita and Jason Carlyon for critical review of the manuscript and Arati Khanna-Gupta for helpful discussion.

This work is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. E.F. received a Clinician-Scientist Award in Translational Research from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Editor: D. L. Burns

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, K., K. Smith, F. Pio, B. Torbett, and R. Maki. 1998. Neutrophils deficient in PU.1 do not terminally differentiate or become functionally competent. Blood 92:1576-1585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babior, B. M. 1999. NADPH oxidase: an update. Blood 93:1464-1476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakken, J. S., and J. S. Dumler. 2001. Proper nomenclature for the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee, R., J. Anguita, D. Roos, and E. Fikrig. 2000. Infection by the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis prevents the respiratory burst by down-regulating gp91phox. J. Immunol. 164:3946-3949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlyon, J., W. Chan, J. Galan, D. Roos, and E. Fikrig. 2002. Repression of rac2 mRNA expression by Anaplasma phagocytophila is essential to the inhibition of superoxide production and bacterial proliferation. J. Immunol. 169:7009-7018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catt, D., S. Hawkins, A. Roman, W. Luo, and D. G. Skalnik. 1999. Overexpression of CCAAT displacement protein represses the promiscuously active proximal gp91(phox) promoter. Blood 94:3151-3160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coccia, E. M., E. Stellacci, R. Orsatti, E. Benedetti, E. Giacomini, G. Marziali, B. C. Valdez, and A. Battistini. 2002. Protein inhibitor of activated signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-1 (PIAS-1) regulates the IFN-gamma response in macrophage cell lines. Cell Signal. 14:537-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Condino-Neto, A., and P. E. Newburger. 2000. Interferon-gamma improves splicing efficiency of CYBB gene transcripts in an interferon-responsive variant of chronic granulomatous disease due to a splice site consensus region mutation. Blood 95:3548-3554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curnutte, J. T. 1993. Chronic granulomatous disease: the solving of a clinical riddle at the molecular level. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 67:S2-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Decker, T., P. Kovarik, and A. Meinke. 1997. GAS elements: a few nucleotides with a major impact on cytokine-induced gene expression. J. Interferon. Cytokine Res. 17:121-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dignam, J. D., R. M. Lebovitz, and R. G. Roeder. 1983. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 11:1475-1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiPietrtantonio, A., T. Hsieh, and J. Wu. 2000. Specific processing of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase, accompanied by activation of caspase-3 and elevation/reduction of ceramide/hydrogen peroxide levels, during induction of apoptosis in host HL-60 cells infected with the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) agent. IUBMB Life 49:49-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dusi, S., M. Donini, D. Lissandrini, P. Mazzi, V. D. Bianca, and F. Rossi. 2001. Mechanisms of expression of NADPH oxidase components in human cultured monocytes: role of cytokines and transcriptional regulators involved. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:929-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eklund, E., A. Javala, and R. Kakar. 2000. Tyrosine phosphorylation of HoxA10 decreases DNA binding and transcriptional repression during interferon gamma-induced differentiation of myeloid cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 275:20117-20126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eklund, E. A., A. Jalava, and R. Kakar. 1998. PU. 1, interferon regulatory factor 1, and interferon consensus sequence-binding protein cooperate to increase gp91(phox) expression. J. Biol. Chem. 273:13957-13965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eklund, E. A., and R. Kakar. 1999. Recruitment of CREB-binding protein by PU. 1, IFN-regulatory factor-1, and the IFN consensus sequence-binding protein is necessary for IFN-gamma-induced p67phox and gp91phox expression. J. Immunol. 163:6095-6105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eklund, E. A., and D. G. Skalnik. 1995. Characterization of a gp91-phox promoter element that is required for interferon gamma-induced transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 270:8267-8273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawkins, S. M., T. Kohwi-Shigematsu, and D. G. Skalnik. 2001. The matrix attachment region-binding protein SATB1 interacts with multiple elements within the gp91phox promoter and is down-regulated during myeloid differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 276:44472-44480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heyworth, P. G., B. P. Bohl, G. M. Bokoch, and J. T. Curnutte. 1994. Rac translocates independently of the neutrophil NADPH oxidase components p47phox and p67phox. Evidence for its interaction with flavocytochrome b558. J. Biol. Chem. 269:30749-30752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh, T., M. Aguero-Rosenfeld, J. Wu, C. Ng, N. Papanikolaou, S. Verde, I. Schwartz, J. Pizzolo, M. Melamed, H. Horowitz, R. Nadelman, and G. Wormser. 1997. Cellular changes and induction of apoptosis in human promyelocytic HL-60 cells infected with the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 232:298-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ijdo, J. W., W. Sun, Y. Zhang, L. A. Magnarelli, and E. Fikrig. 1998. Cloning of the gene encoding the 44-kilodalton antigen of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis and characterization of the humoral response. Infect. Immun. 66:3264-3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobsen, B., and D. Skalnik. 1999. YY1 binds five cis-elements and trans-activates the myeloid cell-restricted gp91phox promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 274:29984-29999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones, O. T. 1994. The regulation of superoxide production by the NADPH oxidase of neutrophils and other mammalian cells. Bioessays 16:919-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kautz, B., R. Kakar, E. David, and E. A. Eklund. 2001. SHP1 protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibits gp91 phox and p67 phox expression by inhibiting interaction of PU. 1, IRF1, ICSBP and CBP with homologous cis elements in the CYBB and NCF2 genes. J. Biol. Chem. 276:37868-37878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelley, T. J., and H. L. Elmer. 2000. In vivo alterations of IFN regulatory factor-1 and PIAS1 protein levels in cystic fibrosis epithelium. J. Clin. Investig. 106:403-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khanna-Gupta, A., T. Zibello, S. Kolla, E. J. Neufeld, and N. Berliner. 1997. CCAAT displacement protein (CDP/cut) recognizes a silencer element within the lactoferrin gene promoter. Blood 90:2784-2795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein, J. B., J. A. Scherzer, and K. R. McLeish. 1991. Interferon-gamma enhances superoxide production by HL-60 cells stimulated with multiple agonists. J. Interferon Res. 11:69-74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein, M. B., J. S. Miller, C. M. Nelson, and J. L. Goodman. 1997. Primary bone marrow progenitors of both granulocytic and monocytic lineages are susceptible to infection with the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J. Infect. Dis. 176:1405-1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein, M. B., C. M. Nelson, and J. L. Goodman. 1997. Antibiotic susceptibility of the newly cultivated agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis: promising activity of quinolones and rifamycins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:76-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumatori, A., D. Yang, S. Suzuki, and M. Nakamura. 2002. Cooperation of STAT-1 and IRF-1 in interferon-gamma-induced transcription of the gp91(phox) gene. J. Biol. Chem. 277:9103-9111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee, E., and Y. Rikihisa. 1998. Protein kinase A-mediated inhibition of gamma interferon-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Janus kinase and latent cytoplasmic transcription factors in human monocytes by Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Infect. Immun. 66:2514-2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, S. L., A. J. Valente, M. Qiang, W. Schlegel, M. Gamez, and R. A. Clark. 2002. Multiple PU. 1 sites cooperate in the regulation of p40(phox) transcription during granulocytic differentiation of myeloid cells. Blood 99:4578-4587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, S. L., A. J. Valente, S. J. Zhao, and R. A. Clark. 1997. PU. 1 is essential for p47(phox) promoter activity in myeloid cells. J. Biol. Chem. 272:17802-17809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lievens, P. M., J. J. Donady, C. Tufarelli, and E. J. Neufeld. 1995. Repressor activity of CCAAT displacement protein in HL-60 myeloid leukemia cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270:12745-12750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin, R., and J. Hiscott. 1999. A role for casein kinase II phosphorylation in the regulation of IRF-1 transcriptional activity. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 191:169-180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu, B., J. Liao, X. Rao, S. A. Kushner, C. D. Chung, D. D. Chang, and K. Shuai. 1998. Inhibition of Stat1-mediated gene activation by PIAS1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:10626-10631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu, J., A. Barnett, E. J. Neufeld, and J. P. Dudley. 1999. Homeoproteins CDP and SATB1 interact: potential for tissue-specific regulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:4918-4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo, W., and D. G. Skalnik. 1996. CCAAT displacement protein competes with multiple transcriptional activators for binding to four sites in the proximal gp91phox promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 271:18203-18210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo, W., and D. G. Skalnik. 1996. Interferon regulatory factor-2 directs transcription from the gp91phox promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 271:23445-23451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin-Soudant, N., J. G. Drachman, K. Kaushansky, and A. Nepveu. 2000. CDP/Cut DNA binding activity is down-modulated in granulocytes, macrophages and erythrocytes but remains elevated in differentiating megakaryocytes. Leukemia 14:863-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meischl, C., and D. Roos. 1998. The molecular basis of chronic granulomatous disease. Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 19:417-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mori, K., S. Stone, L. Khaodhiar, L. E. Braverman, and W. J. DeVito. 1999. Induction of transcription factor interferon regulatory factor-1 by interferon-gamma (IFN gamma) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF alpha) in FRTL-5 cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 74:211-219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mott, J., and Y. Rikihisa. 2000. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent inhibits superoxide anion generation by human neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 68:6697-6703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mott, J., Y. Rikihisa, and S. Tsunawaki. 2002. Effects of Anaplasma phagocytophila on NADPH oxidase components in human neutrophils and HL-60 cells. Infect. Immun. 70:1359-1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogden, N. H., Z. Woldehiwet, and C. A. Hart. 1998. Granulocytic ehrlichiosis: an emerging or rediscovered tick-borne disease? J. Med. Microbiol. 47:475-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharf, R., D. Meraro, A. Azriel, A. M. Thornton, K. Ozato, E. F. Petricoin, A. C. Larner, F. Schaper, H. Hauser, and B. Z. Levi. 1997. Phosphorylation events modulate the ability of interferon consensus sequence binding protein to interact with interferon regulatory factors and to bind DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 272:9785-9792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Skalnik, D. G., D. M. Dorfman, A. S. Perkins, N. A. Jenkins, N. G. Copeland, and S. H. Orkin. 1991. Targeting of transgene expression to monocyte/macrophages by the gp91-phox promoter and consequent histiocytic malignancies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:8505-8509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Skalnik, D. G., E. C. Strauss, and S. H. Orkin. 1991. CCAAT displacement protein as a repressor of the myelomonocytic-specific gp91-phox gene promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 266:16736-16744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suzuki, S., A. Kumatori, I. A. Haagen, Y. Fujii, M. A. Sadat, H. L. Jun, Y. Tsuji, D. Roos, and M. Nakamura. 1998. PU. 1 as an essential activator for the expression of gp91(phox) gene in human peripheral neutrophils, monocytes, and B lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:6085-6090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ting, L. M., A. C. Kim, A. Cattamanchi, and J. D. Ernst. 1999. Mycobacterium tuberculosis inhibits IFN-gamma transcriptional responses without inhibiting activation of STAT1. J. Immunol. 163:3898-3906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valarche, I., J. P. Tissier-Seta, M. R. Hirsch, S. Martinez, C. Goridis, and J. F. Brunet. 1993. The mouse homeodomain protein Phox2 regulates Ncam promoter activity in concert with Cux/CDP and is a putative determinant of neurotransmitter phenotype. Development 119:881-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Voo, K. S., and D. G. Skalnik. 1999. Elf-1 and PU. 1 induce expression of gp91(phox) via a promoter element mutated in a subset of chronic granulomatous disease patients. Blood 93:3512-3520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Webster, P., IJdo, J. W., L. M. Chicoine, and E. Fikrig. 1998. The agent of Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis resides in an endosomal compartment. J. Clin. Investig. 101:1932-1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoshiie, K., H. Y. Kim, J. Mott, and Y. Rikihisa. 2000. Intracellular infection by the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent inhibits human neutrophil apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 68:1125-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhi, N., N. Ohashi, Y. Rikihisa, H. W. Horowitz, G. P. Wormser, and K. Hechemy. 1998. Cloning and expression of the 44-kilodalton major outer membrane protein gene of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent and application of the recombinant protein to serodiagnosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1666-1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]