Abstract

Since the discovery of oxidative demethylation of methylcytosine (mC) by Tet enzymes, an analytical method has been urgently needed that would enable the identification of mC and hydroxymethylcytosine (hmC) at the single base resolution level, because their roles in gene regulation are quite different from each other. However, the bisulfite sequencing method, the gold standard for DNA methylation analysis at present, does not distinguish them. Recently reported alternative methods, such as oxBS-seq and TAB-seq, are not even capable of determining mC and hmC simultaneously. Here, we report a novel method for the direct identification of mC, hmC and unmodified cytosine (C) at a single base resolution. We named this method the Enzyme-assisted Identification of Genome Modification Assay (EnIGMA), and it was demonstrated to indeed have a highly efficient and reliable analytic capacity for distinguishing them. We also successfully applied this novel method to the analysis of the maintenance of the DNA methylation status of imprinted H19-DMR. Importantly, hydroxymethylation plays an ambivalent role in the maintenance of the genome imprinting memory in parental genomes essential for normal development, shedding new light on the epigenetic regulation in ES cells.

INTRODUCTION

Cytosine methylation of genomic DNA plays an essential role in many important biological processes, such as genomic imprinting (1), tumorigenesis (2), gene regulation and retrotransposon silencing (3). Aberration of DNA methylation has detrimental effects on development, including embryonic lethality, cancer and genome instability. It is of critical importance that DNA methylation patterns be stably inherited over many cell divisions. Conservative transmission of cytosine methylation information relies on the specificity of DNMT1, which preferentially methylates the unmethylated C of hemi-methyl CpG (3). However, in contrast to genetic information, epigenetic information is reversible and at times unstable. Mono-allelic expression of an imprinted gene is one of the typical biological events established in the germ cell line in the life cycle and is stably maintained by allelic differences in DNA methylation in somatic cells. On the other hand, epigenetic memories in some of the differentially methylated regions (DMRs) of imprinted gene clusters, such as H19-DMR, are relatively unstable, both at the time of establishment and during the culture of embryonic stem (ES) cells (4). This is a problem, since the integrity of epigenetic memory is an essential factor for stem cell quality control in regenerative medicine.

The mechanism of the demethylation of mC remained unclear for a long time. Then the discovery of the oxidation process by which mC is changed to hmC by the Tet enzymes (5,6) opened the door to the understanding of the DNA demethylation pathway. In this process, mC is oxidized to hmC by the Tet enzymes and subsequently further oxidized to formylcytosine (fC) and carboxylcytosine (caC) by the same enzymes. fC and caC are good substrates for thymine-DNA glycosylase and are excised (7). Then, the resulting AP site is repaired by the base excision repair (BER) process. Therefore, hmC is considered the key intermediate in the DNA demethylation process.

Although hmC discovered as an intermediate of mC demethylation, hmC receive attention as a new modified nucleotide with distinct role in transcriptional regulation. It has been reported that the genome-wide level of hmC is frequently reduced in acute myeloblastic leukemia and glioma because of Tet enzyme inhibition due to a mutation in the IDH1 or IDH2 gene (8). It has also been reported that there are certain hmC-specific binding proteins in the cell that may play a role in transcriptional regulation (9,10).

Therefore, single base resolution level analysis for hmC is one of the indispensable tools needed in epigenomic studies. There are many identification methods for mC in the genome, among which bisulfite sequencing is the gold standard because of its analytic power at a single base resolution. In bisulfite conversion, unmodified C is converted to U, while mC remains unchanged. In the case of hmC, it is changed into cytosine 5-methylenesulfonate and this modified cytosine behaves the same as C in a PCR template (11). Thus, the bisulfite-sequencing method is unable to distinguish mC from hmC.

Several alternative methods for hmC identification have been reported. An hmC specific antibody or a specifically modified hmC and the antibody against the modified residue are used for DNA immuno-precipitation (DIP) to detect hmC (12–14), as in the case with MeDIP (15), and this method is frequently applied for a genome-wide analysis of hmC. However, the resolution level of this method is several hundred bases and it is extremely difficult to compare the magnitude of hmC modification with mC in the genome. oxBS-seq (16) and TAB-seq (17), on the other hand, are methods for detecting hmC at a single base resolution. KRuO4 oxidizes hmC to fC or caC but mC is unchanged by this chemical. This reaction is used in the oxBS-seq method. However, the result of bisulfite sequencing is also needed to identify the hmC when using this method, because the amount of hmC is estimated by the substitution of Cs in the oxBS sequence (mC) compared with the Cs of bisulfite sequence (mC + hmC). Hence, the amount of hmC is indirectly assessed, and the simultaneous detection of mC and hmC on the same molecule is impossible. TAB-seq is based on the activity of the T4 Phage β-glucosyltransferase (T4-BGT) enzyme, which protects hmC from oxidization to caC by Tet1. This method enables a direct detection of hmC at a single base resolution, but once again it is impossible to detect mC on the same DNA molecule simultaneously (as summarized in Table 1). It is also impossible to distinguish between modified patterns, such as ‘salt-and-pepper’ and ‘a mixture of a complete mC, hmC and C molecule’. It is reported that the single molecule sequencer produced by Pacific Biosciences is able to distinguish between mC and C (18). Recently, it was also reported that this sequencer discriminates between hmC and C (19). However, to the best of our knowledge, to date there is no actual report of a simultaneous determination of mC, hmC and C.

Table 1. Comparison of sequence output of previously reported method and EnIGMA.

| Base | Bisulfite-seq | TAB-seq | oxBS-seq | EnIGMA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mC | C | T | C | C+C |

| hmC | C | C | T | C+T |

| C | T | T | T | T+T |

DNMT1 is an enzyme responsible for ‘maintenance methylation’ and methylates the cytosine of hemi-methylated CpG. It is also reported that the DNMT1 enzyme doesn't methylate the cytosine of ‘hemi-hydroxymethylated’ CpG (20,21). Recently, Suetake and Tajima's group have shown that DNMT1 enzyme specificity for hemi-mC can be applied to the identification of hmC (22). However, this method also detected only mC in the same manner as oxBS-seq and determination of hmC in this method was indirect.

Therefore, we designed a novel identification method for the simultaneous identification of mC and hmC using DNMT1 enzyme specificity and further improved the experimental procedure, eventually establishing a simple, quantitative and robust method of identifying hmC, mC and unmodified C on the same DNA molecule at a single base resolution level.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of model DNA

The sequence of the hairpin shaped model DNA was designed corresponding to the H19-DMR region of the mouse genome sequence (chr7:142580029-142580514/GRCm38). A schematic of the model DNA production is presented in Supplementary Data. 8.3 mM each of four synthetic DNA fragments (fragment A, B, C, D) were heat denatured at 98°C for 15 s, then annealed by cooling to 25°C (lamping 0.1°C/s). Then the DNA fragments were ligated by T4 DNA ligase (Takara) at 16°C 12 h. The ligated DNA was purified with 1x AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter). Then, the opposite strand of the ligated DNA was synthesized by ExTaq HS (Takara) under the following conditions: 98°C/10 s, 95°C/30 s, 72°C/1 min and 68°C/1 min. The resulting DNA was purified with 1x AMPure XP and the concentration of the DNA was determined using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent). The sequence of the four fragments were as follows. Fragment A: CGACTCTGTCTCAGGGGATCTGCATATGTTTGCAGCATACTTTAGGTGGGCCTTGGCTTC. Fragment B: p-AGAATX1GGTTATAGGX2GGGAGACATAGAAACTGCX3GX4GTGX5GTGX6GTCCACX7GAAAC. Fragment C: p- CCCATAGCCATAAAAGCAGAGATGCGATGCGTTCGAGCATCGCA. Fragment D: CTCTGCTTTTATGGCTATGGGGTTTCGGTGGACGCACGCACGCGGCAGTTTCTATGTCTCCCGCCTATAACCGATTCTGAAGCCAAGGCCCACCTAAAGT. The Xn in fragment B designates mC, hmC or un-modified C. For the ‘low-methyl’-model DNA, X1 and X4 were mC. X2, X3, X5, X6 and X7 were unmodified C, while for the ‘high-methyl’-model DNA, X1 X3, X4, X5, X6 and X7 were mC. Only X2 was un-modified C. For the ‘mosaic’-model DNA, X1 and X4 were mC, while X2 and X7 were un-modified C, and X3, X5 and X6 were hmC.

We also made a hairpin-shaped model DNA with an Arhgap27 sequence. Fragment B2: TGX1GX2GCTGGCTCAACTGTGTGAGX3GX4GAGAGGAGCCCTGTGCCAX5GCTTX6GTGCAGCAATGCATCX7GCACX8GT. X1 X2, X4, X5, X6, X7 and X8 were mC. Only X2 was unmodified C. Fragment D2: TTATGGCTATGGGACGGTGCGGATGCATTGCTGCACGAAGCGTGGCACAGGGCTCCTCTCGCGCTCACACAGTTGAGCCAGCGCGCAGAAGCCAAGGCCC.

The DNMT1 reaction

Recombinant human DNMT1 was prepared as previously described (23). The DNMT1 enzymatic reaction was conducted as follows. A total of 200 ng of genomic DNA were treated with 1 μg of DNMT1 in 50 μl of reaction buffer consisting of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 50 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM DTT, 0.2 mM S-adenosylmethionine, 0.01% BSA (Takara), 5% glycerol and maintained at 37°C for 15 min. In the case of DNMT1 reaction condition optimization, mixture of 8 fmole model DNA and 200 ng salmon sperm DNA (Invitrogen) were used as the substrate.

Bisulfite sequencing

DNMT1-treated DNA was applied to the bisulfite reaction using the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymoresearch) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Bisulfite-treated DNA was amplified by PCR using EpiTaq HS (Takara) or KOD -Multi & Epi- (Toyobo) using specific primers with an Illumina sequence adaptor for 35 cycles. Then the PCR products were cleaned up with AMPure XP and the adaptor for sequencing was applied using the Nextera XT index kit to the resulting PCR products using five cycles of PCR. PCR products were purified by 1x AMPure XP and sequenced with an Illumina MiSeq system using MiSeq Reagent Micro Kit v2 (Illumina). For the analysis of H19 DMR in mouse tissues and ES cells, resulting PCR products were cloned into pGEM-T easy vector (Promega) and transformed into E. coli. The resulting colonies were randomly picked up and sequences were determined by Sanger sequence.

Preparation of genomic DNA for EnIGMA method

Genomic DNA was purified using AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN) from mouse tissue or cultured cells. A total of 200 ng of genomic DNA was digested with appropriate restriction endonuclease (i.e. Bfa I (New England Biolabs) for top strand of Arhgap27, Bst NI (New England Biolabs) for bottom strand of Arhgap27, Taq I (Takara) for top strand of Nhlrc1, Cvi QI (New England Biolabs) for bottom strand of Nhlrc1and Bst EII (New England Biolabs) for H19 DMR. For Arhgap27 and Nhlrc1, the digested genomic DNA was end-repaired and a dA overhang was added at the 3΄ end using the NEBNext Ultra End Repair/dA-Tailing Module (New England Biolabs). Then, the DNA was ligated with hairpin-shaped adaptor DNA using the NEBNext Ultra Ligation Module (New England Biolabs). This DNA was treated with the USER enzyme (Uracil DNA glycosylase and Endonuclease VIII) (New England Biolabs), ethanol precipitated and synthesized the opposite strand just as for hairpin shaped model DNA, i.e. treated by ExTaq HS (Takara) at 98°C 10 s, 95°C 30 s, 72°C 1 min, 68°C 1 min. Then the DNA was purified by 1.8x AMPure XP. For the H19 DMR, genomic DNA was digested with Bst EII (New England Biolabs) and treated with Shrimp acid phosphatase (Takara) at 37°C for 1 h followed by the heat inactivation of the enzyme at 65°C for 15 min and recovered by ethanol precipitation. Then the DNA was ligated with a hairpin-shaped adaptor DNA for the H19 DMR denatured then opposite strand was synthesized with ExTaq HS (Takara) at 98°C for 10 s, 95°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min 68°C for 1 min.

Primers and adapters

The hairpin adaptor for Arhgap27 and Nhlrc1; p- ATGCGATGCGTTCGAGCATCGCAUT PCR primers with the Illumina sequence adaptor for hairpin shaped model DNA after bisulfite treatment: forward;TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGTAGTATATTTTAGGTGGGTTTTGGTTTT. reverse; GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGACAACATACTTTAAATAAACCTTAACTTC. PCR primers with the Illumina sequence adaptor for the top strand of Arhgap27 after bisulfite treatment: forward; TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGTTTTAGATTAGGTGTTTGGATG. reverse; GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCCCAAACCAAATATTTAAATAC. PCR primers with the Illumina sequence adaptor for the bottom strand of Arhgap27 after bisulfite treatment: forward; TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGGGGGGGGGGGTTTTTATTTTTAGTTTTTTAAAAG. reverse; GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGAAAAAAAAATCTCCACCCTTAACTCCCTAAAAACC PCR primers with the Illumina sequence adaptor for the top strand of Nhlrc1 after bisulfite treatment: forward; TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGTTTTTTTTTAAATTGGTGTGT. reverse; GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGTCCCCCTTTTCTCCAAACTAATATAC. PCR primers with the Illumina sequence adaptor for the bottom strand of Nhlrc1 after bisulfite treatment: forward; TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGTAGTGAATTTTATAGGGTTTGTATTGTGTTTTAAG. reverse; GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGTAAACCCCACAAAACTTACACTATACCCCAAAACC. The hairpin adaptor for H19: p-GTAACATGCGATGCGTTCGAGCATCGCA. PCR primers for H19 after bisulfite treatment: forward; GTTAGTTAGATTTGTTTAATTTAAATTTAATATAGA. reverse; TAACCAAATCTATTCAATCCAAACTCAATACAAAAT.

RESULTS

Establishment of the hmC identification method

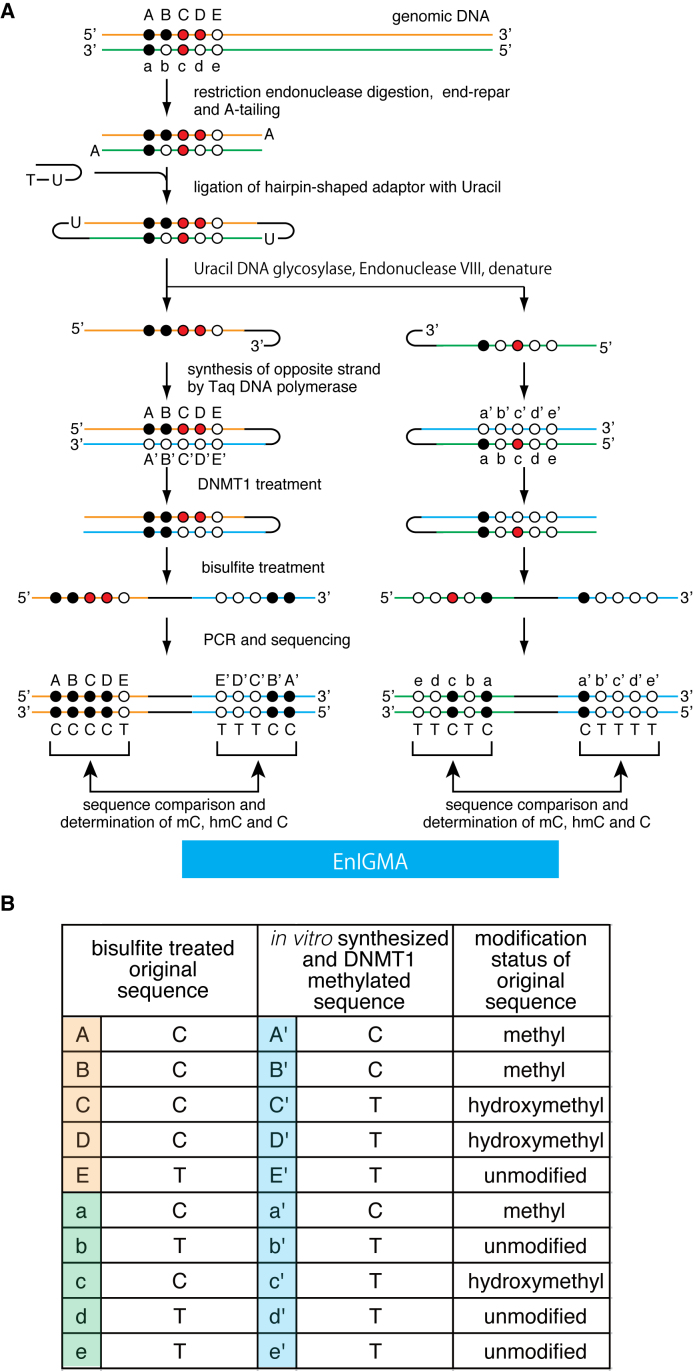

To identify the hmC along with mC, we designed the experimental procedure shown in Figure 1. This method is based on the DNMT1 enzyme specificity, i.e. the enzyme methylates the cytosine of the hemi-methylated CpGs (maintenance methylase activity) but does not methylate hemi-hydroxymethylated CpGs and non-methylated CpGs. First, genomic DNA is digested with the appropriate restriction enzyme. Then the digested DNA is end-repaired, dA tailing and ligated with hairpin-shaped adaptor DNA with dU followed by ‘USER’ enzyme digestion. Alternatively, the digested DNA is dephosphorylated and directly ligated with hairpin-shaped adaptor DNA using cohesive end of the restriction enzyme cutting site. Next, the resulting DNA is treated with DNA polymerase to synthesize the opposite strand. Subsequently, DNA is treated with the DNMT1 enzyme followed by bisulfite treatment and PCR. Finally, the resulting PCR product is sequenced and the corresponding CpGs compared to determine whether the cytosines in the original DNA were mC, hmC or unmodified C (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

(A) A schematic of the EnIGMA method is shown. The black circles designate methylated cytosine, the red circles hydroxylmethylated cytosine and the white circles unmodified cytosine. The EnIGMA method analyzes the CpGs on one strand (orange line for top strand and green line for bottom strand in this figure). The DNA is digested by appropriate restriction endonuclease, and the hairpin DNA is ligated. Next the opposite strand DNA is synthesized in vitro (blue line). Resulted DNA is methylated by DNMT1 enzyme followed by bisulfite conversion and PCR by specific primers. (B) The decoding table for cytosine modification status of the CpGs shown in (A).

First, to test whether the experimental schema presented in Figure 1 worked correctly, we synthesized three hairpin-shaped model substrate DNA in which all the cytosines in the CpGs were mC, hmC or C (Supplementary Data). This 200 bp sequence containing seven CpGs was designed to be the same as the H19-DMR region of mouse genome. The stem and loop sequence of the hairpin substrate was designed based on the hairpin-bisulfite experiment, as previously reported (24).

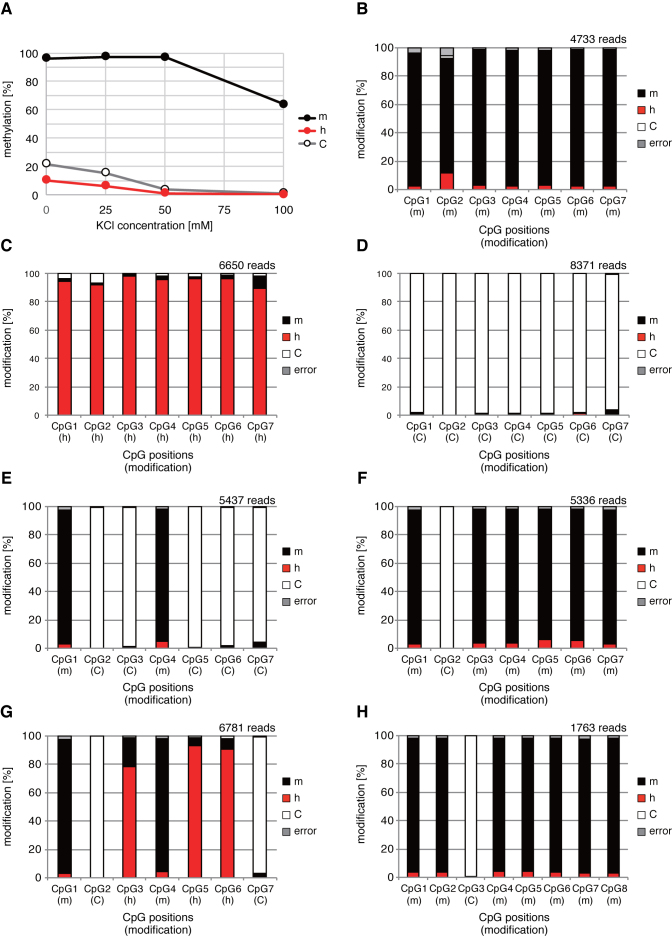

Next, we treated these three substrate DNAs with recombinant human DNMT1 followed by the bisulfite treatment and PCR and tested that this strategy works well to identify mC, hmC and C. We determined the methylation efficiency of DNMT1 by the combined bisulfite restriction analysis (COBRA) method (25) using Taq I restriction enzyme cutting site shown in the Supplementary Data. The substrate specificity of the DNMT1 methylation reaction is critically important for this method, namely the high methylation activity to the opposite strand of mCpG (high maintenance methylation activity) and no methylation activity to the opposite strand of hmCpG and non-modified CpG (suppression of de novo methylation activity). However, it is known that DNMT1 enzyme has significant de novo methylation activity (24) and the salt concentration of reaction buffer was important for the specificity (22). Therefore, we re-examined the KCl concentration of the reaction (Figure 2A). Finally, we determined the optimal reaction condition for the amount of DNA, enzyme, reaction time described in the method section. According to the optimal reaction condition, we treated these three model substrate with DNMT1 and treated by bisulfite solution and the resulting PCR products were sequenced using an Illumina MiSeq sequencer. Then the methylation efficiency of each model substrate DNA was determined (Figure 2B–D). As a result, 93% of the CpGs were methylated in the mC substrate, while only 2.7% and 1.5% were methylated in the hmC and C substrates, respectively. This result meant that mC, hmC and unmodified C could be identified with greater than 93% accuracy utilizing this method. In the bisulfite reaction in this study, the unmodified C that was not converted to U was 0.3%. Thus, the 2.4–1.2% mC observed in the hmC or unmodified C model DNA should be non-specifically de novo methylated by DNMT1. It is well known that DNMT1 enzyme activity is enhanced by the presence of mC in the same DNA molecule (26). Therefore, we made another model DNA with mC and unmodified C in the same molecule in a ‘salt-and-pepper’ manner, i.e. one was ‘low-methyl’-model DNA and the other ‘high-methyl’-model DNA, to determine whether or not the method was in fact thus able to accurately identify the CpG modification status in such a situation. As shown in Figure 2E and F, mC and unmodified C were identified with a greater than 93% accuracy in both models of DNA. Therefore, the de novo methylation activity of DNMT1 is not affected by adjacent mCpGs under this reaction condition. Furthermore, we made model DNA with mC, hmC and unmodified C in the same molecule as a mosaic to determine whether the method was able to accurately identify the CpG modification status. As shown in Figure 2G, mC and unmodified C were identified with a greater than 97% accuracy, while hmC was 9–22% underestimated and misidentified as mC.

Figure 2.

DNMT1 reaction optimization and determination of the analytical power of EnIGMA method using model substrates. (A) KCl concentration of DNMT1 reaction buffer and the methylation activity for model substrate with all CpG with mC, hmC or C are shown in line graph. Reaction buffer with 50 mM KCl concentration, hemi-methylated model DNA was methylated more than 95% while hemi-hydroxymethylated and non-modified model DNA were not methylated. (B–D) The identified modification status under the optimized condition is summarized in a bar graph as the percentage of each status in each of the seven CpGs. (B) Model substrate with all mC. (C) Model substrate with all hmC. (D) Model substrate with all unmodified C. (E) Model substrate with ‘low-methyl’ cytosine modification. (F) Model substrate with ‘high-methyl’ cytosine modification. (G) Model substrate with ‘mosaic’ cytosine modification. (H) Model DNA with Arhgap27 sequece. The position of CpGs and cytosine modification status are presented on the x-axis.

EnIGMA application for hmC rich genomic regions

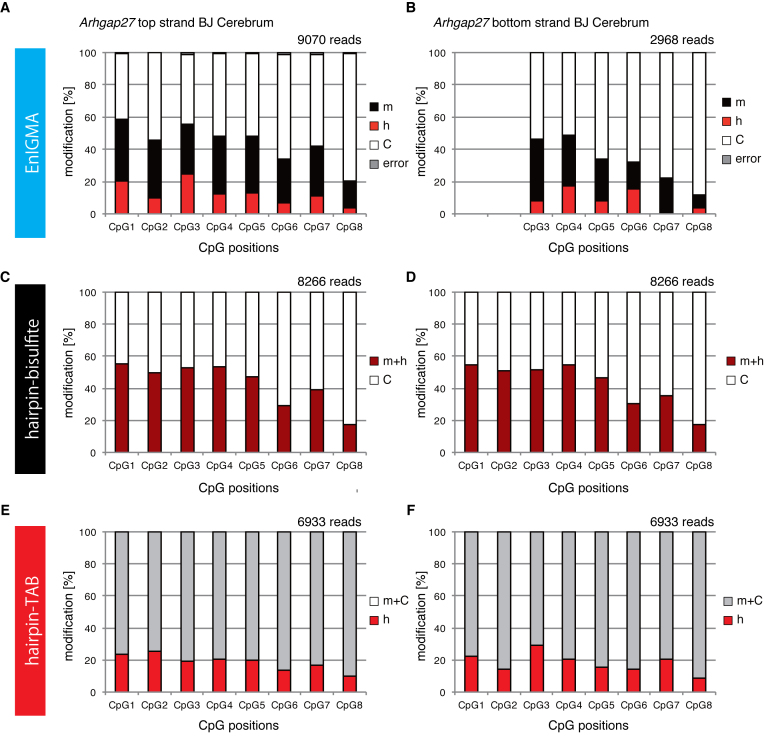

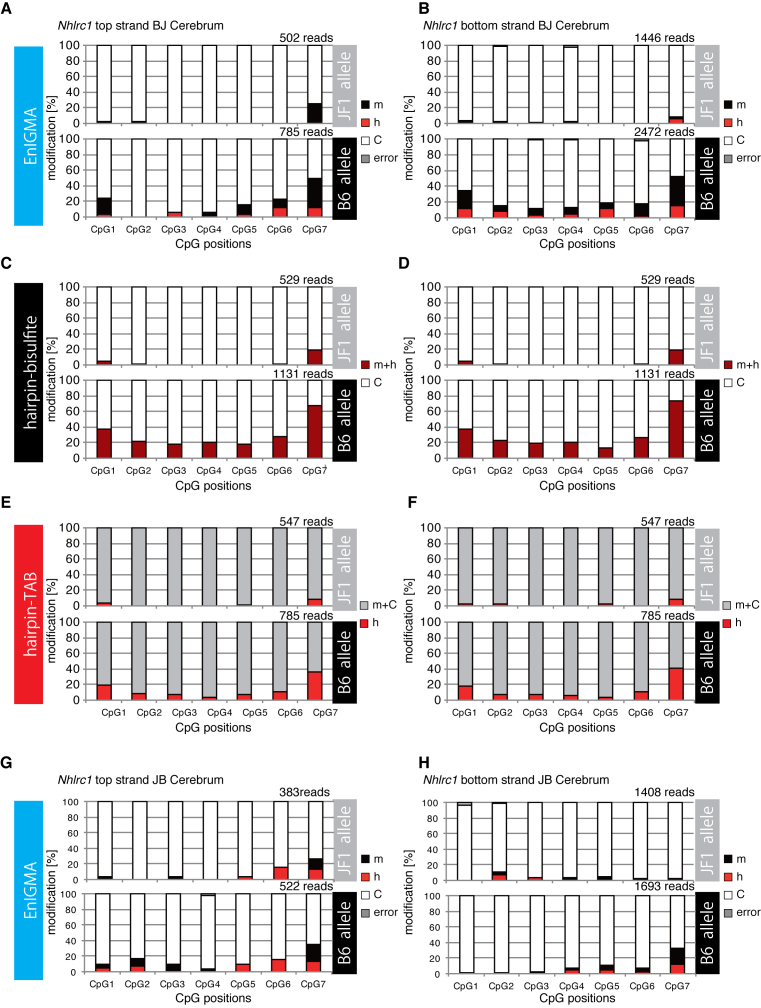

The experiment using model substrate DNA demonstrated that the hemi-methyl CpG specific cytosine methylation activity of hDNMT1 efficiently identified the mC and hmC. First, we analyzed the genomic DNA from several different mouse tissues using glucMS-qPCR assay (27,28) (Supplementary Data) to confirm the accumulation of hmC modification in the genomic regions that were previously reported to be rich in hmC (16). As a result, each CpG in the Arhgap27 (Rho GTPase activating protein 27) and Nhlrc1 (NHL repeat containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1) gene regions had a significant portion of the genome that was suggested to be hydrodxymethylated (Supplementary Data). Therefore, we designed synthetic model DNA for the Arhgap27 locus and confirmed that this locus was also faithfully analyzed by the EnIGMA method. As a result, unmodified CpGs in the densely methylated context in other sequences were also shown to be correctly identified for their modification (Figure 2H). Next, we designed primers and applied the EnIGMA method to these regions in C57BL/6x JF1 F1 (BJF1) mouse cerebrum. As shown in Figure 3A, the Arhgap27 region was substantially methylated (17–38%) and approximately 3.5 to 25% of the CpGs were hydroxymethylated. These results were consistent to the estimation by T4-BGT and GSRE (Supplementary Data). Then cytosine modification of the opposite strand was analyzed by EnIGMA method. Only CpG3–8 were analyzed because we were unable to design a PCR primer for the CpGs 1 and 2. As a result, a similar cytosine modification was observed for the opposite strand (Figure 3B, Supplementary Data). Interestingly, hmC and mC were present on the same molecule in a salt-and-pepper pattern. In the Nhlrc1 region, approximately 0 to 12% hmC was observed in both strands (Figure 4A and B). For Nhlrc1, we were able to distinguish the allele by the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) between C56BL/6 (B6) and JF1. mC and hmC was preferentially observed in the B6 allele in both BJF1 (Figure 4A and B) and JBF1 (Figure 4G and H). Thus, this distortion was a strain-specific epigenetic preferentiality.

Figure 3.

The Arhgap27 of the genome (chr11:103333922-103333851) from the cerebrum of the BJF1 mouse was analyzed using the EnIGMA method, hairpin bisulfite sequence and hairpin TAB sequence. Cytosine modification status of seven CpGs within the region were summarized as % modification in bar graph. (A) EmIGMA result for the Arhgap27 top strand. (B) EmIGMA result for the Arhgap27 bottom strand. (C) Hairpin bisulfite sequence result for the Arhgap27 top strand. (D) Hairpin bisulfite sequence result for the Arhgap27 bottom strand. (E) Hairpin TAB sequence result for the Arhgap27 top strand. (F) Hairpin TAB sequence result for the Arhgap27 bottom strand.

Figure 4.

The Nhlrc1 regions of the genome (chr13:47014397–47014294) from the cerebrum of BJF1 and JBF1 mice were analyzed using the EnIGMA method, hairpin bisulfite sequencing and hairpin TAB sequencing. The cytosine modification status of eight CpGs for each allele (i.e. B6 and JF1) within the region were summarized as the % modification in the bar graph. (A) EmIGMA result of the cerebrum of BJF1 for the Nhlrc1 top strand. (B) EmIGMA result of the cerebrum of BJF1 for the Nhlrc1 bottom strand. (C) Hairpin bisulfite sequence result of the cerebrum of BJF1 for the Nhlrc1 top strand. (D) Hairpin bisulfite sequence result of the cerebrum of BJF1 for the Nhlrc1 bottom strand. (E) Hairpin TAB sequence result of the cerebrum of BJF1 for the Nhlrc1 top strand. (F) Hairpin TAB sequence result of the cerebrum of BJF1 for the Nhlrc1 bottom strand. (G) EmIGMA result of the cerebrum of JBF1 for the Nhlrc1 top strand. (H) EmIGMA result of the cerebrum of JBF1 for the Nhlrc1 bottom strand.

Comparison of EnIGMA and TAB-seq

Next we compared TAB-seq and EnIGMA. We planned to apply hairpin bisulfite sequencing and hairpin TAB-seq (see the schematics in Supplementary Data) because we already had primers and hairpin adaptor DNA for the Arhgap27 and Nhlrc1 loci. As mentioned previously, the bisulfite sequence does not distinguish mC and hmC. Thus, the results of the bisulfite sequence represent mC + hmC versus C. For example, the Arhgap27 locus in the cerebrum displayed good consistency with that obtained by the EnIGMA method because mC + hmC was shown to be 17–55% by bisulfite sequencing (Figure 3C and D) and 20–59% by the EnIGMA method (Figure 3B and C). Next, we applied hairpin TAB sequencing (Figure 3E and F), and the results of the two experiments were similar, except that hmC was estimated to be slightly higher by TAB sequencing (10–26%) than the EnIGMA method (3–25%). In detail, there were some discrepancy between EnIGMA method and TAB sequencing. For example, the CpG7 of the Arhgap27 bottom strand showed 0.2% of hmC by EnIGMA method while TAB sequencing showed 20% of hmC.

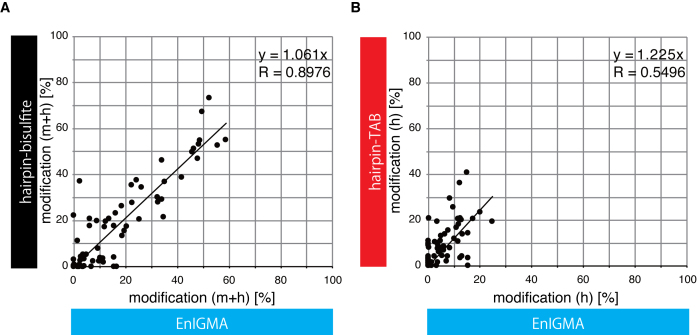

We also compared the estimation of the cytosine modifications in each CpG in these three methods and analyzed them with scatter plots (Figure 5A and B). The correlation coefficient between EnIGMA and bisulfite sequencing was very high (R = 0.8976) and the slope of the regression line through the origin was 1.061. The correlation coefficient between EnIGMA and TAB sequencing was lower (R = 0.5496) than that of EnIGMA and bisulfite sequencing, and the slope of the regression line through the origin was 1.225. Thus, hmC was estimated to be 23% higher by TAB sequencing than the EnIGMA method.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the EnIGMA method, bisulfite sequencing and TAB sequencing. The calculated % cytosine modification of each CpG in both strands of the Arhgap27 and Nhlrc1 regions were plotted. (A) % methyl cytosine + hydroxymethyl cytosine of the EnIGMA method versus hairpin bisulfite sequencing. (B) The % hydroxymethyl cytosine of the EnIGMA method versus TAB sequence sequencing.

EnIGMA application for the imprinted gene H19 DMR

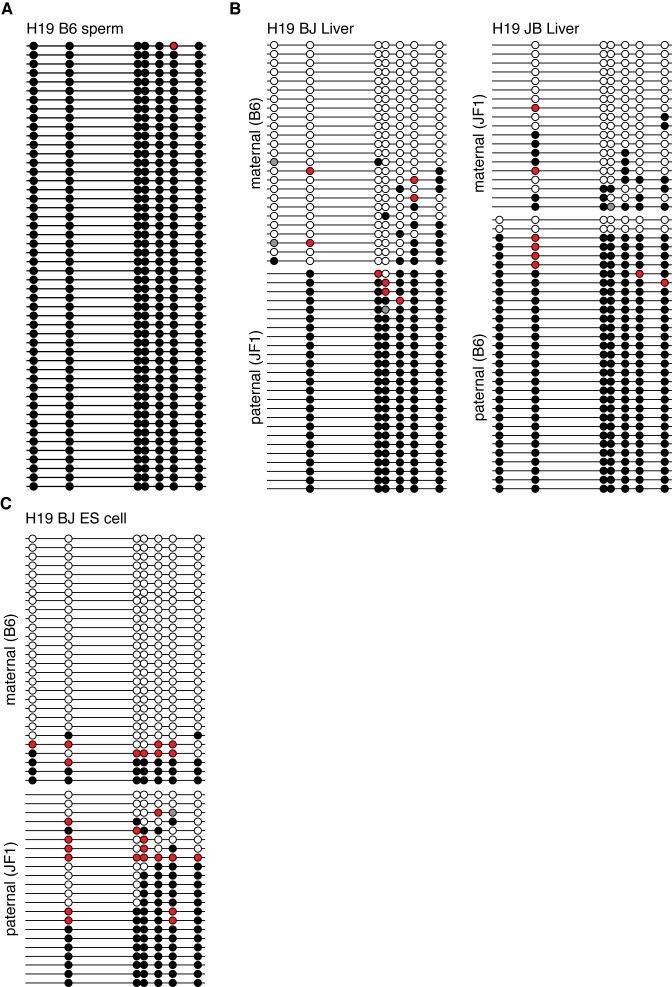

Finally, an effort was made to analyze the CpG modification of the mouse H19-DMR region of mouse genomic DNA from mouse tissues and cultured cells (Figure 6). This region is known to be a part of the ‘primary DMR’, and fully methylated in the sperm genome but unmethylated in the oocyte genome. This methylation difference is maintained after fertilization. As a result, the H19 gene is maternally expressed and the CpGs in this region are known to be methylated in the paternal but not maternal allele. First, we analyzed the modification status of the H19-DMR in sperm (Figure 6A). As expected, almost complete methylation of the CpGs was observed. This region has seven CpGs in C57BL/6, while the JF1 genome has only six CpGs, with one changed to CpT. As shown in Figure 6B, the CpGs in the paternal allele were generally methylated and those in the maternal allele were not, as expected. CpG (2.4–2.5%) was hydroxymethylated in the liver in both the paternal and maternal alleles.

Figure 6.

The mouse H19 DMR region of the genome (chr7:142580029-142580514) from the tissues of the BJF1 and JBF1 was analyzed by the EnIGMA method and is shown as Figure 3. The C57BL/6 genome in this region has seven CpGs, while JF1 has six CpGs because of the C to T single nucleotide polymorphism in the first CpG. A total of 50 sequences were picked up and summarized. (A) Sperm of the C57BL/6. (B) BJF1 liver and JBF1 liver. (C) ES cells derived from a BJF1 embryo.

As mentioned earlier, it has been reported that the allelic methylation of the H19-DMR is unstable in ES cell culture. Therefore, we analyzed the cytosine modification status of this region in ES cells derived from a BJF1 embryo. As shown in Figure 6C, the maternal allele of ES cells is generally unmethylated, while a small numbers of DNA display methylation. Importantly, 11.3% of the CpGs of the maternal allele were methylated and 29.5% of that of paternal allele were unmodified Cs, at the same time, 4.4% of maternal allele CpGs and 12.9% of paternal allele CpGs were hydroxylmethylated.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated the utility of a novel hmC analysis method named EnIGMA. We applied this method to the Arhgap27 and Nhlrc1 genes in the brain of mice and observed a significant number of hmCs, as previously reported. In the case of the analysis of imprinted gene locus, it is important to assess the allelic cytosine modification status. Using EnIGMA method, it is enabled to identify the cytosine modification linked with allelic polymorphism. The results on the H19-DMR in sperm and the liver were also consistent with the previous reports. Unexpectedly, we observed significant amount of hmC modification in both the paternal and maternal alleles of the H19-DMR in the brain and ES cells. Once mCs are oxidized to hmCs, the CpGs on the opposite strand cannot be methylated by DNMT1 enzyme in vivo, then, so these hmCs are believed to be readily demethylated in a passive as well as active manner by the base-excision repair pathway. Quiescent/post-mitotic cells with high TET enzyme activity may accumulate hmC, as observed in the brain. However, a higher maternal hmC level suggests DNA methylation also occurs in the maternal alleles, but is constantly being removed by DNA demethylation via hmC so as to maintain the paternal-specific DNA methylation status. The case of ES cells is rather more problematic because a linkage between higher hmC and the loss of paternally imprinted memory (the DNA demethylation of the paternal alleles) is suggested, while in the maternal allele a gain of irregularly imprinted memory also takes place, with an increase in both mCs and hmCs. This is a clear and non-negligible difference between somatic cells and ES cells. These changes may be associated with developmental abnormality of clone mice using long-cultured ES cells as the donor cell that exhibit high neonatal lethality and a large offspring syndrome (4). In rapidly growing cells, CpGs with a high level of hmC modification would be expected to be continuously under the pressure of passive demethylation. Therefore, paternal DNA methylation of the H19-DMR needs to be constantly subjected to de novo DNA methylation by DNMT enzymes to resist high oxidation by Tet enzymes in order to maintain its methylated status. However, this would result in aberrant DNA methylation on the maternal alleles. The Tet enzyme guards the H19-DMR in the maternal allele from hypermethylation, while accelerating the demethylation of undesirable DNA in the H19-DMR in the paternal allele. Thus, it turns out that it is in fact quite difficult to maintain the differential DNA methylation status of the H19-DMR, because both the paternal and maternal alleles are subjected to DNA methylation and oxidative passive demethylation at the same time in each DNA replication cycle. Maintenance of the integrity of epigenetic memory is essential for stem cell application in regenerative medicine. We used ES cells cultured in conventional KSR+2i medium. It is known that this condition is conducive for the maintenance of pluripotent status of ES cells, but our result with the EnIGMA method indicates that significant improvement is required for the maintenance of imprinted memory of ES cells during this culture. An accurate assessment of the cytosine modification status of the important epigenetic elements in the genome is indispensable for epigenetic quality control of the stem cell culture. In this respect, the EnIGMA method is clearly of great value.

Our observations of frequent hmC modification in a specific genomic region suggest that the methylome, which consists of mC and its oxidative derivatives, is not a static but a dynamic system. Therefore, it is essential to determine mC, hmC and C simultaneously to actually determine the entire landscape of the methylome.

The proposed method for hmC identification named EnIGMA is based on a simple principle, achieving a satisfactory level of identification of cytosine modifications.

From the analysis using the model substrates with each single modified cytosine it was shown that the EnIGMA method was able to identify each modification with an accuracy of more than 95%. A pilot experiment employed a model substrate having mC, hmC and C, and this method resulted in a 9–22% underestimation of hmC. This identification efficiency for hmC was comparable to that of TAB-seq (80–90% accuracy for hmC) (17,29).

We applied the EnIGMA method and hairpin TAB sequencing to the Arhgap27 and Nhlr1 loci in the mouse brain genome and compared the analytical performance of the two methods. These two methods were shown to produce consistent results. In addition, we have successfully applied hairpin bisulfite and hairpin TAB sequencing. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to apply hairpin TAB sequencing. Interestingly, in the Arhgap27 locus, the percentage of hmC in mC plus hmC (estimated from hairpin bisulfite sequencing) for each DNA strand was 29–61% by TAB sequencing, while the fully hmC CpG (h/h) was ∼19–32% (Supplementary Data). This may mean that the oxidation of mC to hmC by the TET enzyme is independently catalyzed to the modification status of the opposite strand cytosine.

We are convinced that the EnIGMA method able to apply the whole genome analysis using massive parallel sequencers because this method is based on simple principle and procedure. The EnIGMA method is based on the hairpin-bisulfite sequencing. Therefore, it is possible to deduce the pre-bisulfite conversion sequence from the resulted sequence (30). This will be not only improves the mapping efficiency for genome-wide bisulfite sequencing (31), but also solves another problem of the cytosine modification analysis carried out using the bisulfite method. The human genome is highly polymorphic and contains a large number of SNPs. Even if the reference sequence is C and the bisulfite-converted sequence is T, it is impossible to determine whether this base was originally an unmodified C or T in individuals checked for C to T conversion at this position. Therefore, resequencing the sample genome is thus necessary. In contrast to this, in the EnIGMA method, if the original strand is an unmodified C, then the opposite strand will be a G. If the original strand is T (C to T SNP) then the opposite strand will be A. Thus, the EnIGMA method enables not only a determination of mC, hmC and C, but also the C to T conversion type SNP without any need of resequencing.

This is of the primary advantages of the hairpin-bisulfite method, because the complementary part of the hairpin sequence preserves the information of the pre-bisulfite conversion. Thus, in the EnIGMA method, it is possible not only to determine the cytosine modification but also to decode the bisulfite-converted sequence back to the original sequence simultaneously. This advantage will enable this method to perform efficient mapping of the sequence reads when it is applied to whole genome analysis.

The EnIGMA method does not have the capacity to analyze non-CpG modifications of cytosine because it depends on the substrate specificity of the DNMT1 enzyme. It is known that the early embryo and ES cells have a significant amount of CpN methylation. Thus, this point is a basic limitation of this method.

As discussed above, the EnIGMA method has significant advantages over the previously reported hmC identification methods with a single base resolution. This method does not need any special equipment and is applicable to many types of epigenetic analyses and important milestone to comprehensive genome-wide analysis of hmC using massive parallel sequencers, because the procedure of this method is both simple and reliable.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr Kousuke Tanimoto and the genome laboratory of Medical Research Institute, Tokyo Medical and Dental University for excellent technical assistance for sequence analysis.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences (JSPS) [Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research 24651210, 26670715, 16K14667 and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas 25112009 to T.K.]; Mitsubishi Foundation [24112 to T.K.]; Integrated Research Projects on Intractable Diseases of the Medical Research Institute, Tokyo Medical and Dental University [to T.K. and Y.Ka.]; Cooperative Research Program of Institute for Protein Research, Osaka University [to T.K. and S.T.]; Inter-University Research Network for Trans-omics [to F.I. and T.K.]. Funding for open access charge: Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences (JSPS) [Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas No. 25112009].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Li E., Beard C., Jaenisch R.. Role for DNA methylation in genomic imprinting. Nature. 1993; 366:362–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Feinberg A.P., Vogelstein B.. Hypomethylation distinguishes genes of some human cancers from their normal counterparts. Nature. 1983; 301:89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li E., Bestor T.H., Jaenisch R.. Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell. 1992; 69:915–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Humpherys D., Eggan K., Akutsu H., Hochedlinger K., Rideout W.M., Biniszkiewicz D., Yanagimachi R., Jaenisch R.. Epigenetic instability in ES cells and cloned mice. Science. 2001; 293:95–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tahiliani M., Koh K.P., Shen Y., Pastor W.A., Bandukwala H., Brudno Y., Agarwal S., Iyer L.M., Liu D.R., Aravind L. et al. . Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009; 324:930–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ito S., D'Alessio A.C., Taranova O. V, Hong K., Sowers L.C., Zhang Y.. Role of Tet proteins in 5mC to 5hmC conversion, ES-cell self-renewal and inner cell mass specification. Nature. 2010; 466:1129–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. He Y.-F., Li B.-Z., Li Z., Liu P., Wang Y., Tang Q., Ding J., Jia Y., Chen Z., Li L. et al. . Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by TDG in mammalian DNA. Science. 2011; 333:1303–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shih A.H., Abdel-Wahab O., Patel J.P., Levine R.L.. The role of mutations in epigenetic regulators in myeloid malignancies. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012; 12:599–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spruijt C.G., Gnerlich F., Smits A.H., Pfaffeneder T., Jansen P.W.T.C., Bauer C., Münzel M., Wagner M., Müller M., Khan F. et al. . Dynamic readers for 5-(Hydroxy)methylcytosine and its oxidized derivatives. Cell. 2013; 152:1146–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iurlaro M., Ficz G., Oxley D., Raiber E.-A., Bachman M., Booth M.J., Andrews S., Balasubramanian S., Reik W.. A screen for hydroxymethylcytosine and formylcytosine binding proteins suggests functions in transcription and chromatin regulation. Genome Biol. 2013; 14:R119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huang Y., Pastor W.A., Shen Y., Tahiliani M., Liu D.R., Rao A.. The behaviour of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in bisulfite sequencing. PLoS One. 2010; 5:e8888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Song C.-X., Szulwach K.E., Fu Y., Dai Q., Yi C., Li X., Li Y., Chen C.-H., Zhang W., Jian X. et al. . Selective chemical labeling reveals the genome-wide distribution of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011; 29:68–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pastor W.A., Pape U.J., Huang Y., Henderson H.R., Lister R., Ko M., McLoughlin E.M., Brudno Y., Mahapatra S., Kapranov P. et al. . Genome-wide mapping of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2011; 473:394–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pastor W.A., Huang Y., Henderson H.R., Agarwal S., Rao A.. The GLIB technique for genome-wide mapping of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nat. Protoc. 2012; 7:1909–1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weber M., Davies J.J., Wittig D., Oakeley E.J., Haase M., Lam W.L., Schübeler D.. Chromosome-wide and promoter-specific analyses identify sites of differential DNA methylation in normal and transformed human cells. Nat. Genet. 2005; 37:853–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Booth M.J., Branco M.R., Ficz G., Oxley D., Krueger F., Reik W., Balasubramanian S.. Quantitative sequencing of 5-Methylcytosine and 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine at Single-Base resolution. Science. 2012; 336:934–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yu M., Hon G.C., Szulwach K.E., Song C.X., Zhang L., Kim A., Li X., Dai Q., Shen Y., Park B. et al. . Base-resolution analysis of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the mammalian genome. Cell. 2012; 149:1368–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Flusberg B.A., Webster D.R., Lee J.H., Travers K.J., Olivares E.C., Clark T.A., Korlach J., Turner S.W.. Direct detection of DNA methylation during single-molecule, real-time sequencing. Nat. Methods. 2010; 7:461–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Song C.-X., Clark T.A., Lu X.-Y., Kislyuk A., Dai Q., Turner S.W., He C., Korlach J.. Sensitive and specific single-molecule sequencing of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nat. Methods. 2011; 9:75–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hashimoto H., Liu Y., Upadhyay A.K., Chang Y., Howerton S.B., Vertino P.M., Zhang X., Cheng X.. Recognition and potential mechanisms for replication and erasure of cytosine hydroxymethylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 40:4841–4849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Otani J., Kimura H., Sharif J., Endo T.A., Mishima Y., Kawakami T., Koseki H., Shirakawa M., Suetake I., Tajima S.. Cell cycle-dependent turnover of 5-hydroxymethyl cytosine in mouse embryonic stem cells. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e82961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Takahashi S., Suetake I., Engelhardt J., Tajima S.. A novel method to analyze 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in CpG sequences using maintenance DNA methyltransferase, DNMT1. FEBS Open Bio. 2015; 5:741–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Takeshita K., Suetake I., Yamashita E., Suga M., Narita H., Nakagawa A., Tajima S.. Structural insight into maintenance methylation by mouse DNA methyltransferase 1 (Dnmt1). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011; 108:9055–9059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vilkaitis G., Suetake I., Klimasauskas S., Tajima S.. Processive methylation of hemimethylated CpG sites by mouse Dnmt1 DNA methyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005; 280:64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xiong Z., Laird P.W.. COBRA: a sensitive and quantitative DNA methylation assay. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997; 25:2532–2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fatemi M., Hermann A., Gowher H., Jeltsch A.. Dnmt3a and Dnmt1 functionally cooperate during de novo methylation of DNA. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002; 269:4981–4984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Davis T., Vaisvila R.. High sensitivity 5-hydroxymethylcytosine detection in Balb/C brain tissue. J. Vis. Exp. 2011; 48:e2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ficz G., Branco M.R., Seisenberger S., Santos F., Krueger F., Hore T. A., Marques C.J., Andrews S., Reik W.. Dynamic regulation of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mouse ES cells and during differentiation. Nature. 2011; 473:398–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yu M., Hon G.C., Szulwach K.E., Song C.-X., Jin P., Ren B., He C.. Tet-assisted bisulfite sequencing of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nat. Protoc. 2012; 7:2159–2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Laird C.D., Pleasant N.D., Clark A.D., Sneeden J.L., Hassan K.M.A., Manley N.C., Vary J.C., Morgan T., Hansen R.S., Stöger R.. Hairpin-bisulfite PCR: assessing epigenetic methylation patterns on complementary strands of individual DNA molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004; 101:204–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Porter J., Sun M.-A., Xie H., Zhang L.. Investigating bisulfite short-read mapping failure with hairpin bisulfite sequencing data. BMC Genomics. 2015; 16(Suppl. 1): S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.