Abstract

Programmed -1 ribosomal frameshifting (-1PRF) is tightly regulated by messenger RNA (mRNA) sequences and structures in expressing two or more proteins with precise ratios from a single mRNA. Using single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (smFRET) between (Cy5)EF-G and (Cy3)tRNALys, we studied the translational elongation dynamics of -1PRF in the Escherichia coli dnaX gene, which contains three frameshifting signals: a slippery sequence (A AAA AAG), a Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence and a downstream hairpin. The frameshift promoting signals mostly impair the EF-G-catalyzed translocation step of the two tRNALys and the slippery codons from the A- and P- sites. The hairpin acts as a road block slowing the translocation rate. The upstream SD sequence together with the hairpin promotes dissociation of futile EF-G and thus causes multiple EF-G driven translocation attempts. A slippery sequence also helps dissociation of the EF-G by providing alternative base-pairing options. These results indicate that frameshifting takes place during the repetitive ribosomal conformational changes associated with EF-G dissociation upon unsuccessful translocation attempts of the second slippage codon from the A- to the P- sites.

INTRODUCTION

Ribosomal frameshifting is programed in some messenger RNAs such that a ribosome can slip on a messenger RNA (mRNA) and start translating a new sequence of amino acids (1–4). Programmed -1 ribosomal frameshifting (-1PRF) is utilized in many RNA viral systems, including HIV-1, to express two or more proteins from a single mRNA (5,6). The Escherichia coli (E. coli) dnaX gene is a well-known -1PRF model system with high efficiencies in the range of ∼50 to ∼80% (7,8). Two DNA polymerase subunits (τ, γ) are programed in the 0 and -1 reading frames (7). Many biochemical studies showed that such efficient -1PRF is promoted by three mRNA signals in the dnaX gene; a hexanucleotide slippery sequence (A AAA AAG) coding two lysine codons, a stimulatory hairpin structure, and a Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence (8–10). The distances between the signals are crucial for the frameshifting efficiency. For the most efficient frameshifting, the signals are positioned in a way that the slippery sequence is placed on the ribosomal peptidyl (P)- and aminoacyl (A)- sites while the downstream hairpin is at the ribosomal mRNA entrance channel. At the same time, the upstream SD sequence base pairs with 16S ribosomal RNA near the ribosomal exit (E) site.

Slow translational elongation rates in the presence of -1PRF signals are well known and widely accepted as an effect of the downstream hairpin structure (1–3), as the ribosome needs to unwind the hairpin structure to translocate (3,11). A translational elongation cycle includes a peptidyl transfer reaction upon delivery of a selected aminoacyl-tRNA by elongation factor-Tu (EF-Tu) as a ternary complex (TC) (EF-Tu(GTP)-aminoacyl-tRNA) (12). In the next step, deacylated- and peptidyl-tRNAs translocate from the ribosomal P- and A- sites to the E- and P-sites and the ribosomal complex advances by three nucleotides toward the 3΄-end of the mRNA. Translocation is accomplished via multistep large-scale conformational changes catalyzed by elongation factor-G (EF-G) (13–16). Spontaneous ribosomal conformational changes include rotation of the ribosomal subunits (50S, 30S) relative to each other, L1 stalk closure and formation of hybrid tRNAs (15–20). In the hybrid state, the anticodon stem loops of the two tRNAs are located at the P- and A-sites in the 30S small subunit while their acceptor arms are located at the E-and P-sites in the 50S large subunit (P/E, A/P). Further structural studies showed that translocation of the codon:anticodon base-pairs through the 30S subunit involves many more intermediates along with EF-G binding and GTP hydrolysis (21–28). EF-G-bound intermediates include swiveling of the head of the 30S subunit and chimeric hybrid tRNAs (pe/E, ap/P or ap/ap), where the two tRNAs are in transit toward translocation direction keeping partial contacts with both P- and E-, and A- and P-sites in each subunits. (21,25–28). Along with the swiveling of the 30S head domain and chimeric hybrid tRNAs, the mRNA is also pulled by 2–3 nucleotides toward the translocation direction (27). Complete translocation is achieved with back rotation of the 30S head domain to the un-swivelled position along with dissociation of EF-G, forming a POST complex, where the two subunits are in a non-rotated state and the tRNAs are in E/E and P/P states (21–23). A recent smFRET study suggested that a rapid reversible head domain movement is involved in the final stage of the translocation as a rate-determining step (29).

Our previous single molecule FRET study on -1PRF of the dnaX gene (30) and a bulk FRET study by Caliskan et al. on -1PRF of a IBV 1a/1b gene (31) showed significantly slower EF-G catalyzed translocation of the second codon of the slippery sequence in the presence of stimulatory secondary structures. Multiple EF-G binding and dissociation events on the ribosomal hybrid state were implied before a successful translocation in the context of -1PRF signals (30,31). Both studies suggested that frameshifting takes place during the translocation process of the second codon of the slippery sequence. Another single molecule study on the -1PRF of the dnaX gene by Chen et al., where they simultaneously probed ribosomal inter-subunit rotation and the events of EF-G or tRNA accommodations, showed that a downstream hairpin structure can induce a non-canonical rotated state during or after translocation of the first codon of the slippery sequence to the P-site (32). Multiple EF-G bindings were observed and proposed to be wasted for back-rotation of the ribosomal complex to relieve the non-canonical state. Frameshifting was proposed to take place during the back-rotation attempts by EF-G binding; accommodation of the next amino acyl-tRNA on the second codon of the slippery sequence takes place on the already frameshifted frame. The proposed timing of the frameshifting by Chen et al. is after accommodation of the first codon, but before accommodation of the second codon of the slippery sequence.

These different results leave open questions on the timing of -1 frameshifting of the dnaX gene and the roles of multiple EF-G bindings during translation of the A AAA AAG frameshifting sequence. Furthermore, the effects of the SD and slippery sequences on frameshifting efficiency has been extensively studied by biochemical analysis (8,33), but their effects on the translation dynamics especially in relation to the EF-G driven translocation has not been studied in detail at a single-molecule level.

Here, by adopting a FRET pair of (Cy3)tRNALys and a (Cy5)EF-G (34), we studied the EF-G binding and dissociation dynamics and their relation with translocation rates in the presence of E. coli dnaX frameshifting signals using single-molecule FRET. We examined the effects of each stimulatory signal on the translation rates and EF-G binding dynamics by mutating the frameshifting signals one by one.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Escherichia coli 70S (35) and initiation factor proteins (36) purified as per protocols described in the literature were kindly provided by Harry F. Noller and Laura Lancaster (University of California, Santa Cruz). EF-Tu was purified with a His-tag as described in the published protocol (37). tRNAs (ChemBlock; Sigma; MP Biomedicals) were aminoacylated with S-100 enzymes and purified by acid-saturated phenol–chloroform extractions (35). (Cy3)tRNALys was prepared by labeling at the natural modification of the 3-(3-amino-3-carboxypropyl) uridine at position 47 (acp3U47) with Cy3 NHS ester and purified with hydrophobic interaction chromatography on FPLC (19). Purified EF-G was labeled with a Cy5 dye at the C-terminus via the Sfp phosphopantetheinyl transferase reaction according to the published protocols (34). The pET-SUMO-EFG-peptide plasmid, encoding the peptide-tagged EF-G for the labeling, was kindly provided by S. Blanchard (Cornell University). mRNAs were prepared by in vitro run off transcriptions on synthetic DNA sequences using T7 promoter.

Tris·polymix buffer (50 mM Tris·OAc, pH7.5, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM NH4OAc, 0.5 mM Ca(OAc)2, 0.1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 6 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 5 mM putrescine and 1 mM spermidine) at 5 mM Mg(OAc)2 was used for the preparations of the ribosomal complexes. Initiation complexes (IC) were enzymatically formed by incubating 1.2 μM 70S with 2.5 μM initiation factors, 2.4 μM mRNA, 2.5 μM fMet-tRNAfMet and 1 mM GTP in the Tris·polymix buffer. Post-translocation complexes with fMet-Val-tRNAVal in the P-site (POST-V) were formed by carrying out one round of translational elongation cycle by incubating the 120 nM IC with preformed 1 μM TC of EF-Tu(GTP)·Val-tRNAVal [TC(V)] and 2 μM GTP-bound EF-G [EF-G(GTP)] at 37°C.

Single molecule FRET experiments

Fluorescence imaging was carried out using a laboratory-built objective-type, wide-field total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscope system (30,38). It is equipped with a double channel imaging system with a diode-pumped 532 nm laser as an excitation source. An oxygen-scavenging system (300 μg/ml glucose oxidase, 40 μg/ml catalase and 1% β-D-glucose; Sigma) and 250 nM GTP were supplemented to the Tris·polymix buffer along with a triplet-state quenching mixture (1 mM 1,3,5,7-cyclooctatetraene (Aldrich), 1 mM p-nitrobenzyl alcohol (Fluka), 1.5 mM Trolox (Sigma)). All the experiments were carried out with time resolution of 35 ms/frame except that the (Cy5)EF-G concentration dependent experiments were carried out with 100 ms/frame. Excitation powers were adjusted to be 4 mW for 100 ms/frame and 6.5 mW for 35 ms/frame to maintain relatively high signal-to-noise ratios. Half-lives of Cy3 until photo-bleached were measured to be ∼90s and ∼60s for 100 ms/frame, and 35 ms/frame, respectively.

POST-V complexes were immobilized on the PEG passivated flow cell surface for the smFRET experiments via annealing the 5΄-end of the mRNAs to a biotinylated DNA primer (5΄-AAG TTA AAC AAA ATT ATT TCT AGA ATTTG-biotin-3΄, underlined nucleotides base-paired with mRNA) (30). Surface immobilized POST-V complexes were subjected to a peptidyl-transfer reaction by delivery of Lys-(Cy3)tRNALys in a TC form (EF-Tu(GTP)·Lys-(Cy3)tRNALys) to form PRE-VK1* complexes. In between the delivery of new reagents, flow cells were washed with corresponding buffers to ensure stalling the ribosomes at a certain step. PRE-VK1* contained tRNAVal and peptidyl-(Cy3)tRNALys in the ribosomal P- and A-sites, respectively. PRE-VK1* complexes were localized by Cy3 fluorescence signals. Real-time (RT) delivery experiments while taking fluorescence imaging were carried out by flowing 25 μl of (Cy5)EF-G and TC(K) at around 10 s after starting imaging. Arrival of (Cy5)EF-G to each molecule was monitored by increased background in the Cy5 channel. Co-localization of the Cy3 and Cy5 signals on single molecules and their time traces were obtained by IDL (ITT) scripts (https://cplc.illinois.edu/software, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign).

Data analysis

The FRET efficiency is calculated as IA/(IA+ID), where IA and ID are the Cy5 acceptor and Cy3 donor fluorescence intensity, respectively. IA and ID are subjected to background subtractions and a cross-talk correction for the donor bleed-through to the acceptor channel (0.14). Time traces of the Cy3 fluorescence and FRET efficiency were truncated into two blocks; (i) from real time (RT) delivery of (Cy5)EF-G to Tl1 event, and (ii) from Tl1 to Tl2. They are separately subjected to idealization by using a hidden Markov modeling-based software (vbFRET) (39). Further data analysis was carried out using Matlab scripts (MathWorks) and Microcal Origin (OriginLab).

RESULTS

mRNA constructs and frameshifting efficiency

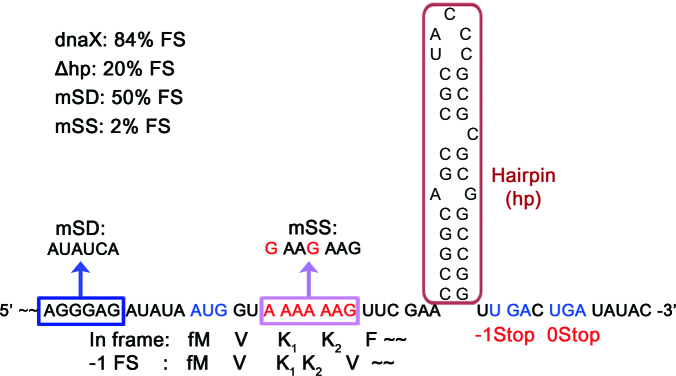

We have designed a dnaX frameshifting mRNA adopting the three frameshifting promoting signals in the E. coli dnaX gene (Figure 1). In the mRNA construct, the SD sequence plays a role as an initiating signal as well as -1PRF signal. The first five codons encode an amino acid sequence of MVKKF, where the tandem lysines are coded in the slippery sequence. Frameshifting by -1 on the slippery sequence results in translating different amino acid sequence (MVKKV∼) and termination at -1 stop codon. In order to examine the effect of each signal on the frameshifting efficiency and the ribosomal dynamics, we constructed mutated mRNAs by deleting the hairpin (Δhp), mutating the SD sequence (mSD: AGGGAG →AUAUCA) and mutating the slippery sequence (mSS: A AAA AAG → G AAG AAG). As both AAA and AAG are read by tRNALys, the mSS still encodes for two consecutive lysines, but is not slippery any more. Mass spectrometry analysis of the in vitro translated products from each mRNA construct showed that FS efficiency drops to 50% by mutating SD, 20% by deleting hairpin, and to 2% by mutating the slippery sequence to be non-slippery (Supplementary Figure S1). These changes are consistent with reported bulk biochemical studies (7,10). The results confirm again that the slippery sequence is essential to the frameshifting and that the hairpin is a critical promoting signal. Also, our data show that the SD sequence clearly plays an important role on frameshifting, although it is not as critical as the hairpin.

Figure 1.

The dnaX messenger RNA (mRNA) construct. The dnaX mRNA contains Escherichia coli dnaX frameshifting signals; an SD sequence, a slippery sequence and a downstream hairpin structure. An initiation codon (AUG) and two stop codons (UGA) for in-frame and -1-frame are encoded. The single SD sequence plays two roles as an initiation and a frameshifting promoting signals. The slippery sequence codes for two consecutive lysines. After the slippery sequence, -1 frame codes for different codons. in vitro translated products from the dnaX mRNA showed 84% frameshifting efficiency. Deleting the hairpin in the box reduces the frameshifting efficiency to 20% and mutating the SD sequence to AUAUCA (mSD) to 50%. Mutating the slippery sequence to a non-slippery G AAG AAG sequence, which is still coding for two lysines, reduced the frameshifting efficiency to 2%.

EF-G binding and dissociation dynamics during two rounds of translocation of the slippery sequence

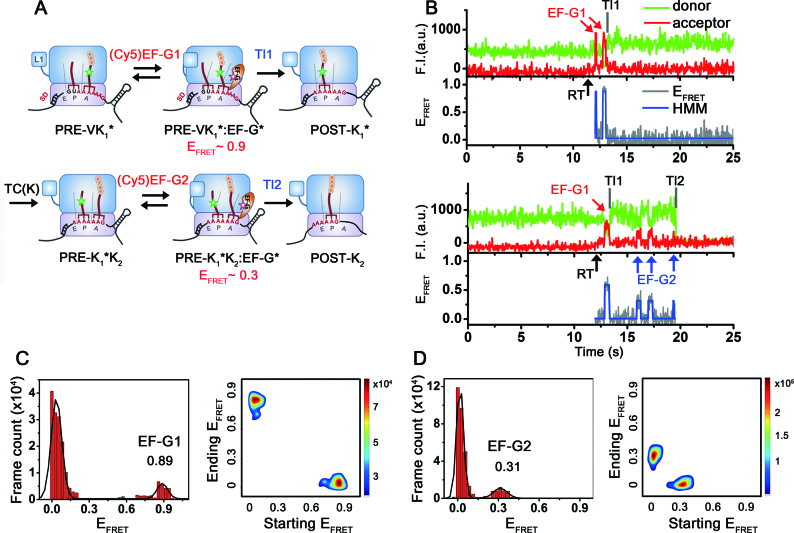

We started the experiments with enzymatically formed PRE-VK1* ribosomal complexes immobilized on the surface as described in the ‘Materials and Methods’ section. PRE-VK1* contains tRNAVal and peptidyl-(Cy3)tRNALys at the ribosomal P- and A-sites, respectively (Figure 2A). The first Lys codon in the slippery sequence is placed at the A-site. The PRE-VK1* complexes were identified by Cy3 fluorescence signals on the surface. Evolution of FRET states were monitored upon real time (RT) delivery of 100–200 nM GTP-bound (Cy5)EF-G alone or with TC of 50–250 nM EF-Tu(GTP)-Lys-tRNALys (TC(K)) while recording fluorescence images.

Figure 2.

Schematic drawings of ribosomal complexes translating through the mRNA, and representative fluorescence time traces and corresponding EFRET states. (A) Schematic drawings of ribosomal complexes during two rounds of translational elongation cycles on the dnaX mRNA monitored by single-molecule FRET experiments. A post-translocation ribosomal complex (POST-V) was enzymatically formed in bulk and contained peptidyl-tRNAVal on the P-site. The complex was immobilized on the surface via hybridization at the 5΄-end with a surface-immobilized DNA strand. A pre-translocation complex (PRE-VK1*), which contains tRNAVal in the P-site and peptidyl-(Cy3)tRNALys in the A-site, was formed on the surface by delivering a ternary complex of EF-Tu(GTP)-Lys(Cy3)tRNALys in the absence of EF-G. PRE-VK1* and PRE-K1*K2 complexes are likely in conformational fluctuations between classical and hybrid states. (B) Representative time traces of fluorescence signals of the dnaX-ribosomal complexes upon real-time (RT, black arrow) delivery of 100 nM (Cy5)EF-G to the PRE-VK1*. The PRE-VK1* complexes were identified by Cy3 signals at the beginning of imaging. Delivery of (Cy5)EF-G triggered excursions of high FRET states (red arrow), indicating accommodation of (Cy5)EF-G near the (Cy3)tRNALys. Later on, Cy5 signals disappeared, while Cy3 intensity slightly increased. The observation is consistent with the published results that a slight increase of the Cy3 signal on the tRNA was assigned to the translocation of the tRNA from the A-site to the P-site (34). Slight increase of the Cy5 background signal is due to the floating (Cy5)EF-G. Bottom trace is a representative time trace of fluorescence signals of dnaX-ribosomal complexes upon co-delivery of (Cy5)EF-G and non-fluorescently labeled TC(K) to the PRE-VK1*. First round of translocation (Tl1) by binding of (Cy5)EF-G1 (red arrow) and the second translocation (Tl2) process with (Cy5)EF-G2 bindings (blue arrows) and changes on the fluorescent signals are observed. Time traces were manually divided into two blocks for further analysis; block 1: from RT to Tl1, block 2: Tl1 to Tl2. (C) FRET histogram and transition density plot of block 1: from RT to Tl1. FRET state of ∼0.9 corresponds to EF-G bound state to PRE-VK1*. (D) FRET histogram and transition density plot of block 2. FRET state of ∼0.3 corresponds to EF-G bound state to PRE-K1*K2. Transitions from 0 to 0.9 or 0.3 FRET correspond to binding of (Cy5)EF-G1 and (Cy5)EF-G2, while transitions from 0.9 or 0.3 to 0 correspond to dissociation of them, respectively.

Delivery of 100 nM of (Cy5)EF-G alone to the dnaX mRNA programmed PRE-VK1* initiated excursions of a high FRET (∼0.9) state followed by increase in Cy3 signals (Figure 2B and C, and Supplementary Figure S2). The observations are consistent with previous smFRET study by Munro et al. showing that the high FRET excursion corresponds to the EF-G binding event, and that the Cy3 fluorescence increases upon translocation of the (Cy3)tRNALys from the A-site to the P-site (34). Once the translocation of the first lysine codon of the slippery sequence (Tl1) took place, the signal of the Cy3 from the (Cy3)tRNALys at the P-site displayed stable constant values until Cy3 photo-bleached (Figure 2B, upper trace). The observations indicate that (Cy5)EF-G binding is specific to the pre-translocation complexes. EF-G1 denotes the EF-G binding events during the translocation of the first lysine codon (Tl1) of the slippery sequence from the A- to the P-site.

The second Lys-tRNALys incorporation and translocation was attempted by co-delivery of 100 nM of (Cy5)EF-G and 200 nM of TC(K). The same high FRET (∼0.9) excursion followed by Cy3 intensity increase was observed as described above, indicating the first translocation (Tl1) took place via binding of the (Cy5)EF-G (EF-G1) as in the experiments delivering (Cy5)EF-G alone. The Tl1 event was followed by another FRET excursions with much less intense Cy5 signals (denoted as EF-G2 by the blue arrows in Figure 2B, bottom trace) resulting in ∼0.3 FRET values (Figure 2D). In contrast to the EF-G1 binding that mostly occurred only once for the Tl1 event, multiple EF-G2 binding events were observed before Cy3 signal disappeared. It is likely that the ∼0.3 FRET state occurs between the (Cy3)tRNALys at the P-site and (Cy5)EF-G accommodated near the A-site. The second round translocation attempts were ongoing by accommodation of the (Cy5)EF-G (EF-G2 for Tl2) after peptidyl transfer from the first (Cy3)tRNALys in the P-site to the second tRNALys in the A-site (Figure 2A). The translocation of the (Cy3)tRNALys to the E-site will be followed by release of the (Cy3)tRNALys from the ribosomal complex, which can be monitored by the disappearance of Cy3 signals (Tl2, Figure 2B, bottom trace).

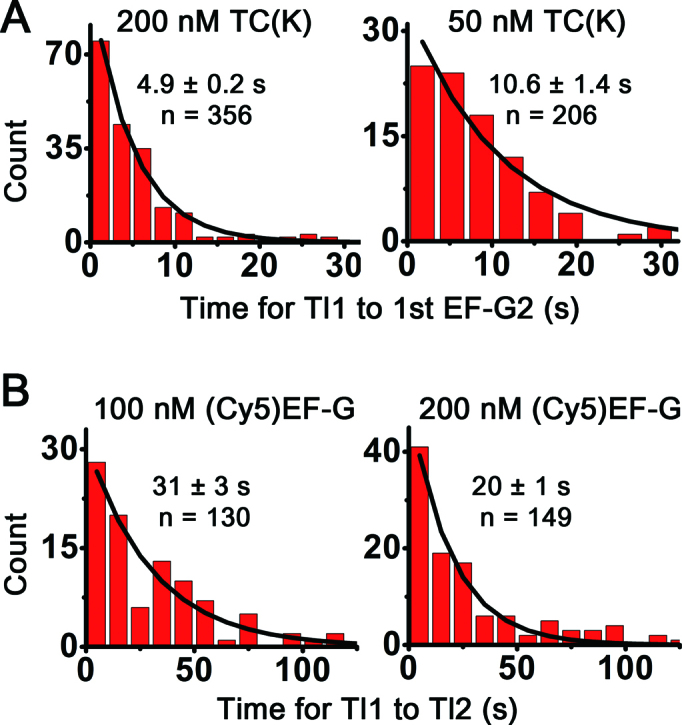

In order to confirm the assignment of the ∼0.3 FRET state, we varied the concentrations of TC(K) and (Cy5)EF-G, one at a time. Upon decreasing TC(K) concentration from 200 to 50 nM, the reaction time from the first translocation (Tl1) to the first binding of the EF-G2 (first EF-G2) increased almost twice (4.9 ± 0.2 versus 10.6 ± 1.4 s, Figure 3A), while there were no considerable changes in other reaction times including the times taken from RT to Tl1, EF-G2 dwell times, and intervals of the EF-G2 binding events (Supplementary Figure S4). The total reaction time from the Tl1 to the Tl2 was slightly increased (29 ± 4 versus 25 ± 2 s, Supplementary Figure S4), just as much as the increase in the duration from Tl1 to the first EF-G2 (Figure 3A). The results suggest that accommodation of TC(K) for the second codon of the slippery sequence and peptidyl transfer take place after Tl1 event but before the first EF-G2 binding event. In other words, EF-G2 binding events are specific to the translocation of the second slippery codon from the A- to the P-sites.

Figure 3.

TC(K) and (Cy5)EF-G concentrations-dependent reaction time changes. (A) TC(K) concentration dependent reaction times from Tl1 to the first binding of (Cy5)EF-G2. As decreased in TC(K) concentration from 200 M to 50 nM at constant 100 nM (Cy5)EF-G, the binding of the EF-G2 took longer by almost twice as much. Excitation laser power was 6.5 mW with time resolution of 35 ms/frame and photo-bleaching half lifetimes was measured to be ∼60 s. (B) (Cy5)EF-G concentration dependent reaction time from Tl1 to Tl2. Fast Tl2 was observed as increase in the (Cy5)EF-G concentration from 100 to 200 nM while keeping [TC(K)] at 250 nM. Excitation power was 4 mW with time resolution of 100 ms/frame and photo-bleaching half lifetimes was measured to be ∼90 s. n is the number of traces. Mean reaction times were obtained by fitting the histograms to single exponential decay curves and errors are propagated standard errors.

Next, (Cy5)EF-G concentrations were increased from 100 to 200 nM while maintaining TC(K) concentration at 250 nM. In order to minimize photo-bleaching effect on the measurements of the translocation times, low excitation energy (4 mW) was used with longer averaging time (100 ms/frame). Considerably decreased reaction times were observed between Tl1 and Tl2 (31 ± 3 versus 20 ± 1 s, Figure 3B), while slight changes were observed in the reaction time for Tl1 to first EF-G2 (4.7 ± 0.2 versus 5.2 ± 0.7 s) and the EF-G2 dwell times (0.44 ± 0.01 versus 0.51 ± 0.01 s) (Supplementary Figure S5). The results suggest that the duration between the Tl1 and Tl2 mostly corresponds to the reaction time for the second round of translocation (Tl2), by which the first and second codon of the slippery sequence, base-pairing with (Cy3)tRNALys and peptidyl-tRNALys, translocate from the P- and A-sites to the E- and P-sites, respectively. Release of the (Cy3)tRNALys from the E-site afterward would result in abolishing the fluorescence signal. Indeed, the whole durations of the Cy3 fluorescence signals were shorter in the case of delivering (Cy5)EF-G and TC(K) together than the photo-bleaching time (τpb) in each experimental condition (τpb = ∼90 s for 100 ms/frame, ∼60 s for 35 ms/frame,).

Another interesting feature of the fluorescence time traces was Cy3 fluorescence intensity transitions to lower values prior to the excursions of Cy5 signals and often independent of the Cy5 signals (dnaX and mSS, Figure 4A). During the low Cy3 intensity periods, multiple Cy5 signal excursions were repeatedly observed with ∼0.3 FRET efficiency (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure S3). Considering that there was no such fluctuations in the Cy3 intensity for the reactions with EF-G only in the absence of TC(K) (POST-K1*, Figure 2A, upper trace), the fluctuations of the Cy3 intensity likely correspond to a spontaneous conformational change of the ribosomal complex (PRE-K1*K2) at an early stage of translocation process such as formation of the hybrid state (16,18–20), by which the Cy3 labeled acceptor end of the deacylated (Cy3)tRNALys at the P-site in the 50S large subunit experiences another environmental changes. Further study is required to confirm the assignment.

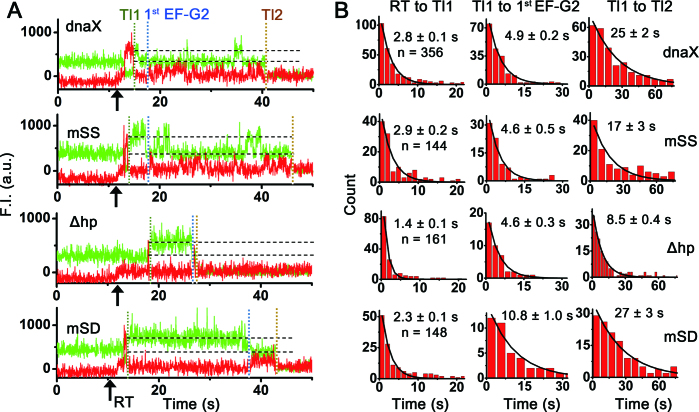

Figure 4.

Comparisons of characteristic fluorescence time traces and reaction times between mRNAs upon delivery of 100 nM (Cy5)EF-G and 200 nM TC(K). (A) Representative time traces of fluorescence signals of each mRNA construct upon co-delivery of (Cy5)EF-G and non-fluorescently labeled TC(K) to the PRE-VK1*. (B) Comparisons of reaction times between the different mRNA constructs. Translocation rate of the first Lys slippery codon (Tl1, left), reaction times from the Tl1 event to the first EF-G2 binding (first EF-G2, middle) and from Tl1 to the second Lys slippery codon translocation event (Tl2) (right) (from top to bottom, dnaX, mSS, Δhp and mSD). n is the number of traces. Mean reaction times were obtained by fitting to single exponential decay curves and errors are propagated standard errors. In both reaction times, Δhp showed faster reaction than the other three constructs that contained the hairpin structure. Reaction times for the Tl2 are much slower than Tl1 for all the mRNA constructs.

Based on these results, we propose that (i) the excursions of the ∼0.3 FRET correspond to the (Cy5)EF-G binding and dissociation events in attempts to promote translocation of the second codon of the slippery sequence from the A- to the P-site, and (ii) the disappearing Cy3 signals corresponds to the release of (Cy3)tRNALys from the E-site upon completed translocation forming POST-K2 (Figure 2A).

Frameshifting signals severely hinder translocation of the second codon of the slippery sequence

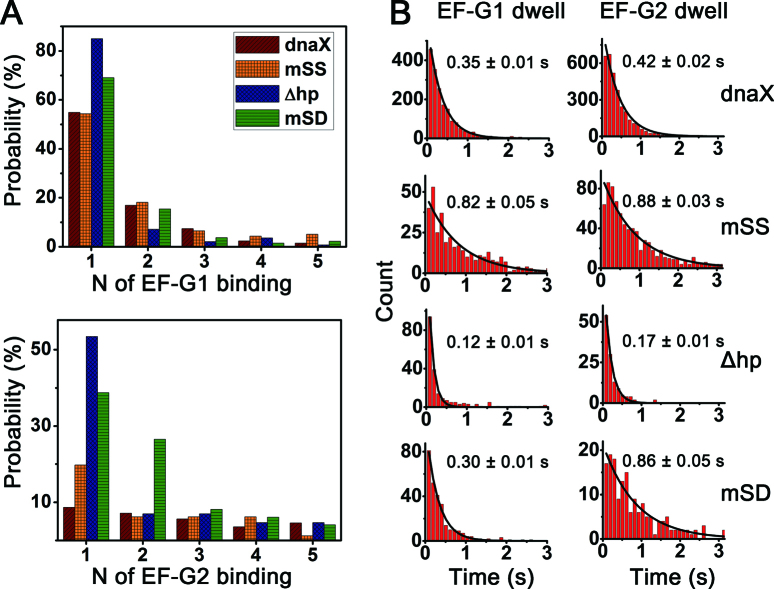

In the dnaX frameshifting mRNA, translocation of the first Lys slippery codon from the A- to the P-site took place in 2.8 ± 0.1 s upon delivery of 100 nM (Cy5)EF-G and 200 nM TC(K) (Figure 4B). Mostly, a single EF-G binding was enough to complete the translocation with an average dwell time of 0.35 ± 0.01 s (Figure 5). After the first slippery codon translocation event (Tl1), binding of another EF-G for the second slippery codon translocation attempts (EF-G2 for Tl2) started being observed in 4.9 ± 0.2 s (Figure 4B, Tl1 to first EF-G2), and release of (Cy3)tRNALys from the E-site upon complete translocation took place in 25 ± 2 s (Figure 4B, Tl1 to Tl2). The long reaction time for the Tl2 is composed of fluctuations of Cy3 fluorescence intensity and multiple EF-G binding and dissociation events during the low Cy3 intensity periods (Figures 2B and 4A). The average dwell time of the bound EF-G2 for the second slippery codon translocation (EF-G2 dwell) was almost the same as that of the EF-G1 for the first slippery codon translocation (EF-G1 dwell) (Figure 5B). These observations imply that frameshifting promoting signals are more severely affecting the translocation of the second Lys codon of the slippery sequence, in a way to hinder the translocation process rather than peptidyl transfer step.

Figure 5.

Comparisons of the number of EF-G bindings required per a translocation and of the bound EF-G dwell times upon delivery of 100 nM (Cy5)EF-G and 200 nM TC(K). (A) Percentage of traces translocated by consuming corresponding number of EF-G bindings for each mRNA; EF-G1 for the Tl1 (upper) and EF-G2 for the Tl2 (bottom). In counting the number of EF-G2 binding events for the Tl2, only the traces showing clear EF-G2 binding events were considered (dnaX: 62%, mSS: 58%, Δhp: 27%, mSD: 34%, Supplementary Table S1). The counted numbers must be biased toward lower numbers, since the EF-G2 binding states probed by low FRET state (∼0.3) were often missed during idealization process. (B) Dwell times of EF-G1 and EF-G2 for each mRNA construct.

Deleting the downstream hairpin (Δhp) expedites the translocation via a short single EF-G binding

Our mass spectrometry analysis on the in vitro translated products confirmed that the hairpin is a strong stimulatory signal for efficient frameshifting; deleting the hairpin reduced the frameshifting efficiency from 84 to 20% (Supplementary Figure S1). In accordance with such a big change of the frameshifting efficiency, there were several significant changes of the ribosomal dynamics upon deleting the hairpin. First of all, the translocation of the Δhp mRNA took place at significantly faster rates for the both first and second slippery Lys codons as compared to those of the dnaX mRNA (RT to Tl1: 1.4 ± 0.1 versus 2.8 ± 0.1 s, Tl1 to Tl2: 8.5 ± 0.4 versus 25 ± 2 s, Figure 4B). In consideration of almost no change on the first EF-G2 binding time after Tl1 event (Tl1 to first EF-G2: 4.6 ± 0.3 versus 4.9 ± 0.2 s, Figure 4B), the difference on the second translocation times becomes more severe. Second, the complete translocation took place with mostly a single EF-G binding event for both rounds of translocation (Figure 5A). Finally, the dwell times of the bound EF-G were more than twice as short (e.g. EF-G2: 0.17 ± 0.01 versus 0.42 ± 0.02 s, Figure 5B). All the results strongly suggest that the hairpin itself indeed hinders the translocation and causes consumptions of multiple number of EF-Gs, in agreement with a previous smFRET study using a FRET pair between the L1 stalk and P-site tRNA (30).

Non-slippery sequence translocation via multiple prolonged EF-G bindings

Mutating the slippery sequence to a non-slippery sequence (mSS) reduced the frameshifting efficiency to 2% (Supplementary Figure S1), confirming that the slippery sequence is essential for frameshifting. The mSS mRNA construct showed almost identical reaction rates as the dnaX on the Tl1 and first EF-G2 binding (Figure 4B). Also a successful translocation of the second Lys codon (Tl2) took place via fluctuations of the Cy3 intensity and multiple EF-G bindings as observed in the dnaX frameshifting mRNA (Figure 4A). However, faster Tl2 was observed on the mSS mRNA (17 ± 3 versus 25 ± 2 s, Figure 4B). Interestingly, the average dwell times of the bound EF-G were prolonged more than twice on both codons compared to those of the dnaX (EF-G1 dwells: 0.82 ± 0.05 versus 0.35 ± 0.01 s and EF-G2 dwells: 0.88 ± 0.03 versus 0.42 ± 0.02 s, Figure 5B). Also a smaller number of EF-G2 bindings were observed for the Tl2 (Figure 5A, bottom). These observations suggest that SS helps dissociation of the bound EF-G to reset the ribosomal complex for another translocation attempt by allowing the ribosomal complex to explore other base-pair interactions. Adopting alternative base-paring might provide more flexibility to the ribosomal complexes in relieving the tension caused by the upstream SD and the downstream secondary structure.

Mutating the SD (mSD) reduces the number of EF-G binding events

Translocation of the second Lys codon (Tl2) on the mSD construct took place via mostly a single EF-G binding as in the case of Δhp (Figures 4A and 5A). It is a distinct difference from the Tl2 process on the dnaX and mSS constructs, which showed multiple EF-G binding and dissociation events until the successful translocation. The dnaX and mSS constructs contain both the upstream SD sequence and the downstream hairpin, while the mSD and Δhp lacks either the hairpin or the SD sequence (Figure 1). However, other than the single EF-G2 bindings for the Tl2, there was no similarity between the results on the mSD and Δhp. Translocation rates on the mSD were as slow as those on the dnaX (Figure 4B). But, EF-G2 dwell time of the mSD was more than twice as long as that of the dnaX (0.86 ± 0.05 versus 0.42 ± 0.02 s), while EF-G1 dwell times are almost the same (0.30 ± 0.01 versus 0.35 ± 0.01 s) (Figure 5B). The results imply that SD sequences promote dissociation of the bound, futile EF-G, especially during the second Lys codon translocation process. These observations suggest that the SD sequence actually aids resetting the ribosomal complex from a non-canonical conformation formed upon encountering a downstream secondary structure. Other noteworthy changes upon mutating the SD are a slower peptidyl transfer rate (Tl1 to first EF-G2: 10.8 ± 1.0 versus 4.9 ± 0.2 s, Figure 4) and a lower success rate of the complete translocation (Supplementary Table S1). These observation indicate that SD has more diverse effects on an overall elongation cycle of the second Lys codon rather than only on the translocation step.

DISCUSSION

In a previous smFRET study using the (Cy3)L1 stalk and a P-site (Cy5)tRNALys, we reported significantly slower EF-G catalyzed translocation of the second Lys codon of the slippery sequence of the dnaX frameshifting mRNA in comparison to the mRNA lacking the hairpin (Δhp) (30). Furthermore, the dnaX-programmed PRE ribosomal complexes experienced multiple conformational fluctuations between the hybrid and classical states with possible multiple EF-G binding-dissociation events prior to translocation. In contrast, Δhp-programmed PRE complexes sampled the hybrid state approximately once with one EF-G binding event before undergoing translocation. Here, we directly visualized EF-G binding and dissociation events along with two rounds of translocation events using a FRET pair of (Cy3)tRNALys and (Cy5)EF-G. The results in this study show that the dnaX-programmed PRE complexes translocate the second Lys codon of the slippery sequence via multiple EF-G binding and dissociation events and Δhp-programmed PRE complexes translocate fast with a single EF-G binding. Our study shows that frameshifting signals mostly impair the translocation step of the slippery codons from A- and P- to P- and E-sites after peptidyl transfer to the second Lys codon.

Consistent with our results, several other studies suggest that frameshifting takes place most likely during the translocation process of the two slippage Lys codons from the A- and P- to the P- and E-sites (1,31,40). Especially, a bulk FRET study between the ribosome and EF-G by Caliskan et al. suggested that frameshifting promoting secondary structure in the mRNA hinders translocation step of the two slippage codons by impairing the back-rotation of the 30S head domain and dissociation of EF-G (31). Their observation of the prolonged EF-G dwells by bulk study can be explained by our results showing multiple EF-G binding events for the slow translocation of the second Lys codon, since greater number of EF-G binding events results in longer dwells on average. In another single molecule fluorescence study, Chen et al. employed a zero-mode waveguide to directly observe binding events of (Cy5)EF-G or (Cy3)/(Cy5)tRNA while monitoring the inter-subunit rotation with a FRET pair of (Cy3B)30S and (BHQ)50S ribosomal subunits (32). They also observed that multiple EF-G bindings were required during or after translocation of the first Lys codon to resolve a long lived inter-subunit rotated state. Thus, the proposed timing of the frameshifting in their study is prior to the peptidyl transfer to the second Lys codon of the slippery sequence, unlike our results. The different results might be due to different experimental conditions including different labeling schemes. Further study will be required for more systematic comparisions between the experimental conditions that regulating the ribosomal dynamics and thus the frameshifting pathways.

Translocation of the PRE on the non-slippery sequence (mSS) proceeded via multiple EF-G binding events similar to that of the dnaX–PRE complexes, but the dwell times of the EF-G bound states were more than twice as long. Our results indicate that the slippery sequence not only provides alternative base-pairing options, which is a prerequisite for the frameshifting, but also helps the ribosomal complexes under strain to be relaxed faster. Among the large-scale conformational changes involved in the translocation process, back-rotation of the 30S head was proposed as the rate-determining step and takes place along with EF-G dissociation (22–24,28,29). EF-G-bound intermediate hybrid states were observed with swiveling of the head of the 30S subunit, on which tRNAs are in chimeric hybrid state (pe/E, ap/P or ap/ap) and mRNA codon:anticodon are pulled by 2–3 nucleotides in the translocation direction (21,25–28). The faster dissociation of futile EF-G in the presence of the slippery sequence suggests that codon:anticodon base pair interactions are partially disrupted on an EF-G trapped intermediate hybrid state and need to be reformed before EF-G dissociation. A slippery sequence can help fast reformation of the codon:anticodon base pairings by providing alternative base pair options. Recently Yan et al. in our research group showed that a ribosome can be very flexible in adopting frameshifting steps such that not only -1, but also -2 and even +2 slips occur in the presence of the same stimulatory structure (41). Thermodynamic stability of the codon-anticodon base-pairing interactions was suggested as the major determinants in the final frameshifting steps. Their results also imply that codon:anticodon base-pairings are easily reformed for more stable interactions.

Translocation of the PRE programmed with mutated SD (mSD) took place slowly as in the dnaX–PRE complexes, indicating that a hairpin itself can be a strong road block without the SD sequence. However, multiple EF-G binding events were not observed for the mSD-PRE complexes during the long period of translocation process. Interestingly, multiple EF-G bindings were only observed for the PRE-ribosomal complexes with mRNAs containing both a SD and a hairpin (dnaX, mSS). Multiple shorter EF-G binding events in the presence of SD shows that the SD sequence works with the hairpin to promote EF-G dissociation. Unresolved SD-rRNA base pairings may push the ribosomal complexes backward such as back-swiveling of the 30S head domain along with the mRNA, during which trapped futile EF-G dissociation is also facilitated. Once reset, the ribosomal complexes are now open for another translocation attempt. A single-molecule force study by our research group inferred that a trapped ribosome on the slippery sequence between the upstream SD-sequence and the downstream hairpin may be able to move back and forth by one or two nucleotides (41). These observations also support our proposal, as such ribosomal movement can correspond to the reversible swiveling of the 30S head domain accompanying 2–3 nucleotide movements of mRNA (27) The low success rate on translocation of the mSD may also mean that the resetting of the ribosomal complex with EF-G dissociation is a more active way to promote translocation on the slippery sequence surrounded by the SD and hairpin. Without the active conformational resetting processes, the ribosomal complex might be stalled in an inactive form such as a non-canonical rotated state (32,42). Therefore, SD sequence actively stimulate frameshifting by promoting such dynamic ribosomal conformational changes. Our proposal explains why there were no correlations between frameshifting efficiency and the pausing extent (43,44) or the thermodynamic or mechanical stabilities of the downstream secondary structures (5,45), but the conformational plasticity of the structure was related to the frameshifting efficiency (5,45).

Our results show that a downstream hairpin traps PRE ribosomal complexes by hindering the translocation of the slippery sequence and corresponding two tRNAs from the A- and P-sites to the P- and E-sites. An upstream SD sequence promotes dissociation of futile EF-G bindings and thus enables multiple attempts of EF-G catalyzed translocations. A slippery sequence provides base-pairing options in out-of-frame as well as in-frame sequences, which also helps expediting EF-G dissociation. Our results indicate that frameshifting takes place during the translocation process of the two slippage codons from the A- and P- to the P- and E-sites. More specifically, frameshifting takes place along with dissociation of futile EF-G, which facilitates ribosomal conformational resetting process involving back-swiveling of the 30S head domain. More chances of frameshifting can be produced upon repetitive ribosomal conformational changes associated with each EF-G dissociation. We find that most efficient frameshifting can be achieved by dynamic conformational changes during the translocation process.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Laura Lancaster and Harry F. Noller (University of California, Santa Cruz) for providing wild-type 70S ribosome and initiation factor proteins, Scott Blanchard (Cornell University, New York) for providing pET-SUMO-EFG-peptide plasmid and Filipp Frank (University of California, Berkeley) for offering Sfp phosphopantetheinyl transferase. We thank Ruben Gonzalez for advices and helps on smFRET experiments on ribosomal translations in general.

Footnotes

Present address: Hee-Kyung Kim, Nuclear Chemistry Research Division, Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute, Daejeon 34057, South Korea.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health (NIH) [GM10840 to I.T.]. Funding for open access charge: NIH [GM10840 to I.T.].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Farabaugh P.J. Programmed translational frameshifting. Microbiol. Rev. 1996; 60:103–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gesteland R.F., Atkins J.F.. Recoding: dynamic reprogramming of translation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996; 65:741–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tinoco I. Jr, Kim H.K., Yan S.. Frameshifting dynamics. Biopolymers. 2013; 99:1147–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkins J.F., Loughran G., Bhatt P.R., Firth A.E., Baranov P.V.. Ribosomal frameshifting and transcriptional slippage: From genetic steganography and cryptography to adventitious use. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:7007–7078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giedroc D.P., Cornish P.V.. Frameshifting RNA pseudoknots: structure and mechanism. Virus Res. 2009; 139:193–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brierley I., Dos Ramos F.J.. Programmed ribosomal frameshifting in HIV-1 and the SARS-CoV. Virus Res. 2006; 119:29–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsuchihashi Z., Kornberg A.. Translational frameshifting generates the gamma subunit of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990; 87:2516–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsen B., Wills N.M., Gesteland R.F., Atkins J.F.. rRNA-mRNA base pairing stimulates a programmed -1 ribosomal frameshift. J. Bacteriol. 1994; 176:6842–6851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuchihashi Z., Brown P.O.. Sequence requirements for efficient translational frameshifting in the Escherichia coli dnaX gene and the role of an unstable interaction between tRNA(Lys) and an AAG lysine codon. Genes Dev. 1992; 6:511–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsen B., Gesteland R.F., Atkins J.F.. Structural probing and mutagenic analysis of the stem-loop required for Escherichia coli dnaX ribosomal frameshifting: programmed efficiency of 50%. J. Mol. Biol. 1997; 271:47–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qu X., Wen J.D., Lancaster L., Noller H.F., Bustamante C., Tinoco I. Jr. The ribosome uses two active mechanisms to unwind messenger RNA during translation. Nature. 2011; 475:118–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voorhees R.M., Ramakrishnan V.. Structural basis of the translational elongation cycle. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013; 82:203–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodnina M.V., Wintermeyer W.. The ribosome as a molecular machine: the mechanism of tRNA-mRNA movement in translocation. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011; 39:658–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agirrezabala X., Liao H.Y., Schreiner E., Fu J., Ortiz-Meoz R.F., Schulten K., Green R., Frank J.. Structural characterization of mRNA-tRNA translocation intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012; 109:6094–6099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munro J.B., Sanbonmatsu K.Y., Spahn C.M., Blanchard S.C.. Navigating the ribosome's metastable energy landscape. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2009; 34:390–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J., Tsai A., O'Leary S.E., Petrov A., Puglisi J.D.. Unraveling the dynamics of ribosome translocation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2012; 22:804–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valle M., Zavialov A., Sengupta J., Rawat U., Ehrenberg M., Frank J.. Locking and unlocking of ribosomal motions. Cell. 2003; 114:123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cornish P.V., Ermolenko D.N., Noller H.F., Ha T.. Spontaneous intersubunit rotation in single ribosomes. Mol. Cell. 2008; 30:578–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanchard S.C., Kim H.D., Gonzalez R.L. Jr, Puglisi J.D., Chu S.. tRNA dynamics on the ribosome during translation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004; 101:12893–12898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fei J., Kosuri P., MacDougall D.D., Gonzalez R.L. Jr. Coupling of ribosomal L1 stalk and tRNA dynamics during translation elongation. Mol. Cell. 2008; 30:348–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ratje A.H., Loerke J., Mikolajka A., Brunner M., Hildebrand P.W., Starosta A.L., Donhofer A., Connell S.R., Fucini P., Mielke T. et al. Head swivel on the ribosome facilitates translocation by means of intra-subunit tRNA hybrid sites. Nature. 2010; 468:713–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ermolenko D.N., Noller H.F.. mRNA translocation occurs during the second step of ribosomal intersubunit rotation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011; 18:457–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo Z., Noller H.F.. Rotation of the head of the 30S ribosomal subunit during mRNA translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012; 109:20391–20394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramrath D.J., Lancaster L., Sprink T., Mielke T., Loerke J., Noller H.F., Spahn C.M.. Visualization of two transfer RNAs trapped in transit during elongation factor G-mediated translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013; 110:20964–20969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tourigny D.S., Fernandez I.S., Kelley A.C., Ramakrishnan V.. Elongation factor G bound to the ribosome in an intermediate state of translocation. Science. 2013; 340:1235490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pulk A., Cate J.H.. Control of ribosomal subunit rotation by elongation factor G. Science. 2013; 340:1235970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou J., Lancaster L., Donohue J.P., Noller H.F.. Crystal structures of EF-G-ribosome complexes trapped in intermediate states of translocation. Science. 2013; 340:1236086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou J., Lancaster L., Donohue J.P., Noller H.F.. How the ribosome hands the A-site tRNA to the P site during EF-G-catalyzed translocation. Science. 2014; 345:1188–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wasserman M.R., Alejo J.L., Altman R.B., Blanchard S.C.. Multiperspective smFRET reveals rate-determining late intermediates of ribosomal translocation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016; 23:333–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim H.K., Liu F., Fei J., Bustamante C., Gonzalez R.L. Jr, Tinoco I. Jr. A frameshifting stimulatory stem loop destabilizes the hybrid state and impedes ribosomal translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014; 111:5538–5543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caliskan N., Katunin V.I., Belardinelli R., Peske F., Rodnina M.V.. Programmed -1 frameshifting by kinetic partitioning during impeded translocation. Cell. 2014; 157:1619–1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen J., Petrov A., Johansson M., Tsai A., O'Leary S.E., Puglisi J.D.. Dynamic pathways of -1 translational frameshifting. Nature. 2014; 512:328–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atkins J.F., Baranov P.V., Fayet O., Herr A.J., Howard M.T., Ivanov I.P., Matsufuji S., Miller W.A., Moore B., Prere M.F. et al. Overriding standard decoding: implications of recoding for ribosome function and enrichment of gene expression. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2001; 66:217–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munro J.B., Wasserman M.R., Altman R.B., Wang L., Blanchard S.C.. Correlated conformational events in EF-G and the ribosome regulate translocation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010; 17:1470–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moazed D., Noller H.F.. Interaction of tRNA with 23S rRNA in the ribosomal A, P, and E sites. Cell. 1989; 57:585–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lancaster L., Noller H.F.. Involvement of 16S rRNA nucleotides G1338 and A1339 in discrimination of initiator tRNA. Mol. Cell. 2005; 20:623–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boon K., Vijgenboom E., Madsen L.V., Talens A., Kraal B., Bosch L.. Isolation and functional analysis of histidine-tagged elongation factor Tu. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992; 210:177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joo C., Ha T.. Selvinn PR, Ha T. Single-molecule FRET with total internal reflection microscopy. Single Molecule Techniques: a Laboratory Manual. 2007; NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bronson J.E., Fei J., Hofman J.M., Gonzalez R.L. Jr, Wiggins C.H.. Learning rates and states from biophysical time series: a Bayesian approach to model selection and single-molecule FRET data. Biophys. J. 2009; 97:3196–3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Namy O., Moran S.J., Stuart D.I., Gilbert R.J., Brierley I.. A mechanical explanation of RNA pseudoknot function in programmed ribosomal frameshifting. Nature. 2006; 441:244–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yan S., Wen J.D., Bustamante C., Tinoco I. Jr. Ribosome excursions during mRNA translocation mediate broad branching of frameshift pathways. Cell. 2015; 160:870–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qin P., Yu D., Zuo X., Cornish P.V.. Structured mRNA induces the ribosome into a hyper-rotated state. EMBO Rep. 2014; 15:185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tu C., Tzeng T.H., Bruenn J.A.. Ribosomal movement impeded at a pseudoknot required for frameshifting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992; 89:8636–8640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kontos H., Napthine S., Brierley I.. Ribosomal pausing at a frameshifter RNA pseudoknot is sensitive to reading phase but shows little correlation with frameshift efficiency. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001; 21:8657–8670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ritchie D.B., Foster D.A., Woodside M.T.. Programmed -1 frameshifting efficiency correlates with RNA pseudoknot conformational plasticity, not resistance to mechanical unfolding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012; 109:16167–16172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.