Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to analyze the clinicopathologic characteristics and prognosis of signet ring cell carcinoma (SRC) according to disease status (early vs advanced gastric cancer) in gastric cancer patients.

Background:

The prognostic implication of gastric SRC remains a subject of debate.

Methods:

A retrospective analysis was performed using the clinical records of 7667 patients including 1646 SRC patients who underwent radical gastrectomy between 2001 and 2010. A further analysis was also performed after dividing patients into three groups according to histologic subtype: SRC, well-to-moderately differentiated (WMD), and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma.

Results:

SRC patients have younger age distribution and female predominance compared with other histologic subtypes. Notably, the distribution of T stage of SRC patients was distinct, located in extremes (T1: 66.2% and T4: 20%). Moreover, the prognosis of SRC in early gastric cancer and advanced gastric cancer was contrasting. In early gastric cancer, SRC demonstrated more favorable prognosis than WMD after adjusting for age, sex, and stage. In contrast, SRC in advanced gastric cancer displayed worse prognosis than WMD. As stage increased, survival outcomes of SRC continued to worsen compared with WMD.

Conclusions:

Although conferring favorable prognosis in early stage, SRC has worse prognostic impact as disease progresses. The longstanding controversy of SRC on prognosis may result from disease status at presentation, which leads to differing prognosis compared with tubular adenocarinoma.

Keywords: gastric cancer, prognostic factor, signet ring cell carcinoma

Histologically, gastric carcinoma demonstrates marked heterogeneity at both the architectural and cytologic levels, often with the coexistence of several histologic elements. Signet ring cell carcinoma (SRC) is a form of adenocarcinoma (AC) whose histologic diagnosis is based on microscopic characteristics defined by the World Health Organization (WHO).1 The predominant component is scattered malignant cells containing intracytoplasmic mucin, which occupies more than 50% of tumors. SRC and non-SRC are thought to be distinct biologic entities originating from different sources of carcinogenesis. Based on histologic findings that SRC is poorly cohesive and has a propensity to invade via submucosal and subserosal routes, worse prognosis of SRC or diffuse-type gastric cancer has been suggested by early Western studies.2–4 However, several noncomparative Asian studies have begun to question this idea,5,6 and only recently, a large-volume study from the United States demonstrated that after adjusting for age, SRC does not necessarily portend a worse prognosis.7 Moreover, several comparative studies have suggested that the prognostic impact of SRC may be dependent on disease stage, although this remains controversial.8 These discrepancies can be explained—at least partly—by the methodology and design variations of each study, the interpersonal discrepancies regarding pathologic definitions, the heterogeneity of non-SRC groups according to tumor grade, and the insufficiency of stage-stratified analyses for comparison. Therefore, for better understanding of the prognostic impact of SRC, a larger volume of patients exhibiting consistency in the surgical technique applied and pathological diagnosis are necessary, and a comparative analysis with non-SRC patients according to tumor grade. Asian gastric cancers are characterized by (i) earlier tumor stage at diagnosis based on nationwide mass screening; (ii) a more consistent surgical approach including extended lymph node dissection (D2); and (iii) consensual adjuvant chemotherapy. Herein, we compared SRC with well-to-moderately differentiated (WMD) and poorly differentiated (PD) tubular AC in patients who underwent radical gastrectomy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Selection

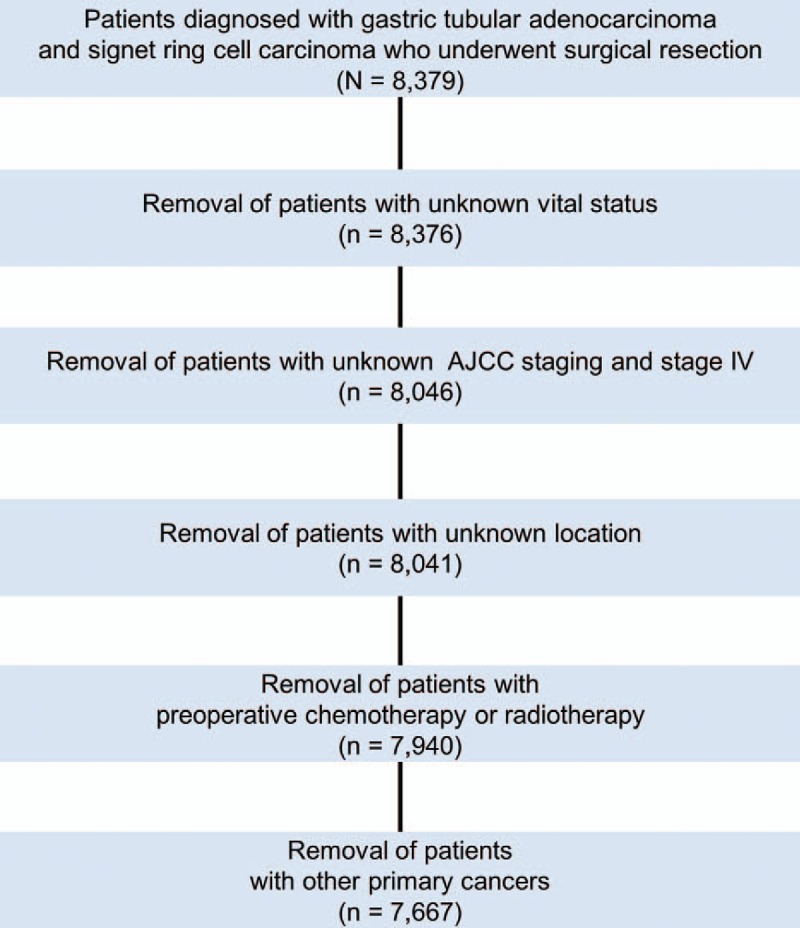

This study included patients who underwent curative (R0) resection of gastric cancer at Severance Hospital, Seoul, Korea, from January 2001 to December 2010. The main selection criteria were as follows: (i) pathologically confirmed tubular AC or SRC and (ii) available documented information regarding the primary tumor site, postoperative pathological stage, surgery, and survival. The main exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) patients who received neoadjuvant chemo(radio)therapy, (ii) metastatic disease, and (iii) concurrent double primary cancer. Thus, 712 of 8379 selected patients were excluded (Fig. 1). A predesigned data collection format was used to extract the data from a prospectively maintained database. The pathologic stage was classified according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging manual (7th edition). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital.

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT diagram. AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer, 7th edition.

All specimens, including the resected stomach and regional lymph nodes, were histologically examined by independent pathologists. Based on the WHO definition, SRC was defined as the predominance (>50%) of isolated carcinoma cells containing intracytoplasmic mucin that pushes the nucleus to the cell periphery. Tubular AC was also classified as well (well-formed glands, often resembling metaplastic intestinal epithelium), moderately, or poorly differentiated (highly irregular glands that are recognized with difficulty) according to the WHO classification.1 We divided the patients into three groups: SRC, WMD, and PD for further evalution.

Statistical Analysis

The cutoff date was August 31, 2014 with a maximum follow-up period of 10 years. The basic demographic and clinical characteristics among groups were compared using independent t tests and χ2 tests. For pair-wise comparison of each level of categorical variables, statistical significance was adjusted for inflated Type I error from multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method.

Relapse-free survival (RFS) was measured from the time of surgery to initial tumor relapse (local recurrence or distant), and overall survival (OS) was calculated as the time from surgery to death of any cause or the last follow-up date. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier (KM) method and then compared with the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard model was used for multivariable analysis of prognostic factors, including age at diagnosis, sex, stage, and histologic type. Statistical significance was set as P < 0.05 for all analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

A total of 7667 patients who underwent curative resection of tubular AC or SRC were analyzed. As depicted in Table 1, 1646 patients (21.5%) had SRC, and 6021 patients (78.5%) were recorded as having tubular AC. Of these tubular AC patients, 1136 (14.8%) were well differentiated, 2267 (29.6%) were moderately differentiated, and the remaining 2618 (34.1%) were PD.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Subjects

| Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma (A) (N = 1646) | Well and Moderately Differentiated AC (B) (N = 3403) | Poorly Differentiated AC (C) (N = 2618) | ||||||

| Variable | N | % | N | % | P (A vs B) | N | % | P (A vs C) |

| Female sex | 833 | 50.6 | 775 | 22.8 | <0.001 | 1000 | 38.2 | <0.001 |

| Age, yrs | ||||||||

| Mean | 51.8 | 60.7 | <0.001 | 55.6 | <0.001 | |||

| SD | 12.0 | 10.2 | 12.3 | |||||

| Distribution (yrs) | ||||||||

| 15–30 | 49 | 3.0 | 18 | 0.5 | <0.001 | 43 | 1.6 | 0.007 |

| 31–40 | 276 | 16.8 | 106 | 3.1 | <0.001 | 287 | 11.0 | <0.001 |

| 41–50 | 459 | 27.9 | 423 | 12.4 | <0.001 | 581 | 22.2 | <0.001 |

| 51–60 | 431 | 26.2 | 975 | 28.7 | 0.134 | 684 | 26.1 | 0.999 |

| 61–70 | 341 | 20.7 | 1366 | 40.1 | <0.001 | 733 | 28.0 | <0.001 |

| 71–80 | 83 | 5.0 | 473 | 13.9 | <0.001 | 260 | 9.9 | <0.001 |

| 81–95 | 7 | 0.4 | 42 | 1.2 | 0.012 | 30 | 1.1 | 0.027 |

AC indicates adenocarcinoma; SD, standard deviation.

The age at initial diagnosis was younger in SRC patients than in WMD or PD patients (SRC: 52 yrs; WMD: 61 yrs; PD: 56 yrs; SRC vs WMD and PD: t test P < 0.001). The peak age range of SRC patients was 41 to 50 years, whereas it was 61 to 70 years for both the WMD and PD groups, reaffirming that the SRC group had a different age distribution. In addition, SRC had a higher percentage of females (SRC: 50.6%; WMD: 22.8%; PD: 38.2%; SRC vs WMD and PD: χ2P < 0.001).

Tumor Presentation

At initial diagnosis, 61.9% of SRC patients were at stage IA, whereas 58.2% of WMD patients and only 29.7% of PD patients were diagnosed as stage IA (SRC vs WMD: χ2P= 0.024; SRC vs PD: χ2P < 0.001) (Table 2). Meanwhile, SRC was less likely to be presented at intermediate stages extending from stages IB to IIIA. In terms of tumor (T) and nodal (N) stages, a higher proportion of patients with SRC presented with T1a in which the tumor was contained only in the mucosal layer (SRC: 46.5%; WMD: 31.8%; PD: 14.7%; SRC vs WMD and PD: χ2P < 0.001) and N0 (SRC: 74.2%; WMD: 71.6%; PD: 47.7%; SRC vs WMD: χ2P= 0.105; SRC vs PD: χ2P < 0.001). Similar to the stage distribution, patients with SRC were less likely to present at intermediate tumor (T2 and T3) and nodal stages (N1 and N2). The anatomic locations of tumors and Lauren's classification of each subtype are shown in Table 3.

TABLE 2.

Tumor Characteristics at Presentation

| Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma (A) | Well and Moderately Differentiated AC (B) | Poorly Differentiated AC (C) | ||||||

| Variable | N | % | N | % | P (A vs B) | N | % | P (A vs C) |

| AJCC stage | ||||||||

| 1A | 1019 | 61.9 | 1,981 | 58.2 | 0.024 | 778 | 29.7 | <0.001 |

| 1B | 124 | 7.5 | 395 | 11.6 | < 0.001 | 274 | 10.5 | 0.003 |

| 2A | 90 | 5.5 | 263 | 7.7 | 0.006 | 224 | 8.6 | <0.001 |

| 2B | 101 | 6.1 | 215 | 6.3 | 0.999 | 335 | 12.8 | <0.001 |

| 3A | 74 | 4.5 | 194 | 5.7 | 0.147 | 243 | 9.3 | <0.001 |

| 3B | 85 | 5.2 | 177 | 5.2 | 0.999 | 305 | 11.7 | <0.001 |

| 3C | 153 | 9.3 | 178 | 5.2 | <0.001 | 459 | 17.5 | <0.001 |

| Tumor stage | ||||||||

| T1a | 766 | 46.5 | 1,081 | 31.8 | <0.001 | 384 | 14.7 | <0.001 |

| T1b | 325 | 19.7 | 1,100 | 32.3 | <0.001 | 529 | 20.2 | 0.999 |

| T2 | 119 | 7.2 | 408 | 12.0 | <0.001 | 363 | 13.9 | <0.001 |

| T3 | 107 | 6.5 | 376 | 11.0 | <0.001 | 380 | 14.5 | <0.001 |

| T4a | 318 | 19.3 | 431 | 12.7 | <0.001 | 935 | 35.7 | <0.001 |

| T4b | 11 | 0.7 | 7 | 0.2 | 0.019 | 27 | 1.0 | 0.439 |

| Node stage | ||||||||

| N0 | 1222 | 74.2 | 2438 | 71.6 | 0.105 | 1248 | 47.7 | <0.001 |

| N1 | 118 | 7.2 | 406 | 11.9 | <0.001 | 384 | 14.7 | <0.001 |

| N2 | 112 | 6.8 | 266 | 7.8 | 0.400 | 389 | 14.9 | <0.001 |

| N3a | 105 | 6.4 | 207 | 6.1 | 0.999 | 356 | 13.6 | <0.001 |

| N3b | 89 | 5.4 | 86 | 2.5 | <0.001 | 241 | 9.2 | <0.001 |

AJCC indicates American Joint Committee on cancer, 7th edition

TABLE 3.

Anatomic Location of Tumor in the Stomach and Lauren's Classification

| Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma (A) | Well and Moderately Differentiated AC (B) | Poorly Differentiated AC (C) | ||||||

| Variable | N | % | N | % | P (A vs B) | N | % | P (A vs C) |

| Location | ||||||||

| Upper | 173 | 10.5 | 374 | 11.0 | 0.999 | 417 | 15.9 | <0.001 |

| Middle | 648 | 39.4 | 850 | 25.0 | <0.001 | 916 | 35.0 | 0.008 |

| Lower | 819 | 49.8 | 2175 | 63.9 | <0.001 | 1276 | 48.7 | 0.999 |

| Whole | 6 | 0.4 | 4 | 0.1 | 0.064 | 9 | 0.3 | 0.999 |

| Lauren's classification* | ||||||||

| Intestinal | 14 | 1.2 | 2273 | 94.8 | <0.001 | 514 | 27.8 | <0.001 |

| Diffuse | 1160 | 96.4 | 41 | 1.7 | <0.001 | 1131 | 61.1 | <0.001 |

| Mixed | 29 | 2.4 | 84 | 3.5 | 0.152 | 207 | 11.2 | <0.001 |

*5453 of 7667 patients with available data were categorized according to Lauren's classification.

Similar to other subtypes, SRC was found mostly in the lower third of the stomach. In terms of Lauren's classification, most SRC (96.4%) were classified as diffuse-type, and most cases of WMD (94.8%) were classified as intestinal-type. In cases of PD, 61.1% were classified as diffuse-type, whereas 27.8% were intestinal-type.

Survival

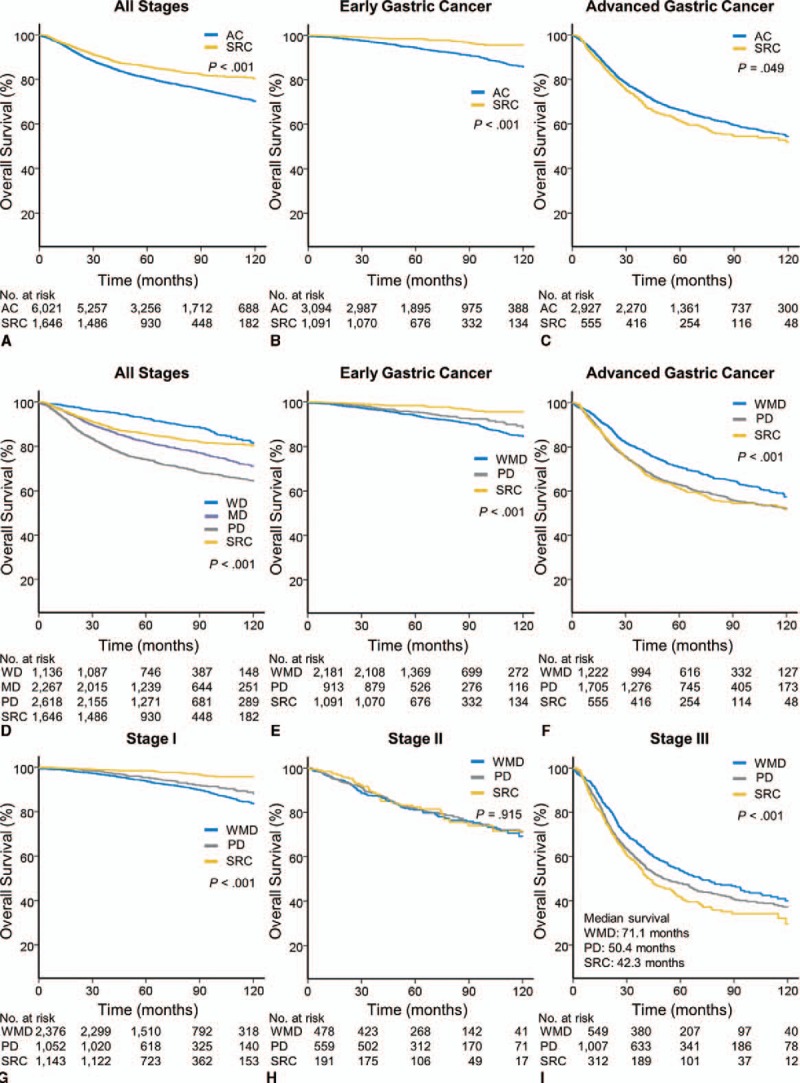

The median length of follow up was 63.9 months. KM curves according to pathologic classification are shown in Figure 2. SRC had significantly better OS than non-SRC (10 year OS: 80% vs 70%; P < 0.001; Fig. 2A). Intriguingly, when all patients were divided into early gastric cancer (EGC) and advanced gastric cancer (AGC) groups, SRC displayed significantly better survival than non-SRC in EGC (10 yr OS: 95% vs 85%; P < 0.001; Fig. 2B); however, the survival was overturned in AGC (10 yr OS: 53% vs 54%; P = 0.049; Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

(A–C) Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival curves of tubular adenocarcinoma (AC) and signet ring cell carcinoma (SRC) are shown for (A) overall survival (OS) of all stages, (B) OS of early gastric cancer (EGC), and (C) OS of advanced gastric cancer (AGC). (D) KM curves comparing the OS of patients with well differentiated (WD), moderately differentiated (MD), and poorly differentiated (PD) tubular AC and SRC at all stages. (E–I) KM curves comparing the OS of patients with well-to-moderately differentiated (WMD) and poorly differentiated (PD) tubular AC and SRC at: (E) EGC, (F) AGC, (G) American Joint Committee on Cancer, 7thh edition (AJCC) stage I, (H) AJCC stage II, and (I) AJCC stage III.

We then compared the OS of SRC with that of non-SRC after dividing the latter into WMD and PD groups (Figs. 2E–I). By peforming a pair-wise comparison, we found that SRC showed a significantly better OS than both WMD and PD in EGC (10 yr OS: SRC: 95%; WMD: 84%; PD 89%; SRC vs WMD and PD: P < 0.001; Fig. 2E). Interestingly, the OS of PD was significantly longer than WMD (KM P < 0.001). On the other hand, SRC and PD demonstrated significantly worse OS than WMD in AGC (10 yr OS: SRC: 53%; WMD: 58%; PD: 52%; WMD vs SRC and PD: P < 0.001; Fig. 2F). However, the OS of SRC and PD were not significantly different on pair-wise comparison analysis.

Regarding to individual stages, SRC showed the best survival outcome, followed by PD and WMD in stage I (10 yr OS: SRC: 96%; PD: 89%; WMD 83%; SRC vs WMD and PD: P < 0.001; Fig. 2G). Meanwhile, in stage II, no statistically significant differences were observed among the three groups. In stage III, the worst survival was observed for SRC, followed by PD and WMD (10 yr OS: SRC: 32%; PD: 37%; WMD 40%; SRC vs WMD: P < 0.001; SRC vs PD: P = 0.086; Fig. 2G). These survival trends were also applied to the RFS of respective groups, as shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Predictors of Recurrence and Mortality

The unadjusted bivariate analysis results of the RFS and OS of all patients are shown in Supplementary Table 1. In all patients, SRC (vs non-SRC) was the factor associated with reduced recurrence and mortality. However, when compared with WMD, SRC was not associated with recurrence and mortality.

Thereafter, we performed an unadjusted analysis for RFS and OS divided by EGC and AGC (Table 4). In EGC, SRC was associated with reduced recurrence and mortality, comparing both with non-SRC and WMD. Meanwhile, in AGC, SRC (vs WMD) was associated with increased recurrence and mortality, and SRC (vs non-SRC) displayed a borderline significance in increased recurrence and mortality in AGC (RFS: Cox hazard ratio, (HR) 1.15; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.99 to 1.34; P= 0.066; OS: Cox HR 1.15; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.33; P= 0.050).

TABLE 4.

Unadjusted Factors Associated with Overall Survival in EGC and AGC

| RFS | OS | |||||

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P |

| EGC | ||||||

| WHO histology and grade | ||||||

| PD (vs WMD) | 0.82 | 0.53 to 1.26 | 0.357 | 0.73 | 0.54 to 0.98 | 0.036 |

| SRC (vs WMD) | 0.26 | 0.14 to 0.49 | <0.001 | 0.30 | 0.20 to 0.45 | <0.001 |

| SRC (vs non-SRC) | 0.28 | 0.15 to 0.52 | <0.001 | 0.33 | 0.22 to 0.48 | <0.001 |

| Age at diagnosis | 1.03 | 1.01 to 1.04 | 0.002 | 1.09 | 1.07 to 1.10 | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 0.55 | 0.36 to 0.84 | 0.005 | 0.45 | 0.34 to 0.61 | <0.001 |

| AJCC stage II (vs stage I) | 7.22 | 4.59 to 11.37 | <0.001 | 3.08 | 2.03 to 4.69 | <0.001 |

| Submucosal invasion | 2.02 | 1.40 to 2.92 | <0.001 | 1.65 | 1.30 to 2.09 | <0.001 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 6.15 | 4.27 to 8.88 | <0.001 | 2.43 | 1.80 to 3.28 | <0.001 |

| Location* | ||||||

| Middle (vs upper) | 1.60 | 0.67 to 3.80 | 0.289 | 0.99 | 0.64 to 1.53 | 0.952 |

| Lower (vs upper) | 2.10 | 0.92 to 4.81 | 0.080 | 0.93 | 0.61 to 1.42 | 0.735 |

| AGC | ||||||

| WHO histology and grade | ||||||

| PD (vs WMD) | 1.40 | 1.23 to 1.60 | <0.001 | 1.31 | 1.16 to 1.49 | <0.001 |

| SRC (vs WMD) | 1.42 | 1.19 to 1.69 | <0.001 | 1.36 | 1.15 to 1.60 | <0.001 |

| SRC (vs non-SRC) | 1.15 | 0.99 to 1.34 | 0.066 | 1.15 | 1.00 to 1.33 | 0.050 |

| Age at diagnosis | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.01 | 0.650 | 1.02 | 1.02 to 1.03 | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 1.13 | 1.00 to 1.27 | 0.051 | 1.05 | 0.93 to 1.17 | 0.452 |

| AJCC stage | ||||||

| Stage II (vs stage I) | 3.72 | 2.50 to 5.53 | <0.001 | 2.14 | 1.61 to 2.83 | <0.001 |

| Stage III (vs stage I) | 14.20 | 9.75 to 20.68 | <0.001 | 7.02 | 5.42 to 9.09 | <0.001 |

| Tumor stage | ||||||

| T3 (vs T2) | 2.28 | 1.80 to 2.89 | <0.001 | 1.90 | 1.55 to 2.33 | <0.001 |

| T4 (vs T2) | 5.75 | 4.68 to 7.06 | <0.001 | 4.24 | 3.57 to 5.05 | <0.001 |

| Node stage | ||||||

| N1 (vs N0) | 2.29 | 1.82 to 2.90 | <0.001 | 1.69 | 1.38 to 2.07 | <0.001 |

| N2 (vs N0) | 3.91 | 3.16 to 4.84 | <0.001 | 2.64 | 2.19 to 3.18 | <0.001 |

| N3 (vs N0) | 8.82 | 7.29 to 10.67 | <0.001 | 6.31 | 5.39 to 7.40 | <0.001 |

| Location | ||||||

| Middle (vs upper) | 0.96 | 0.81 to 1.15 | 0.684 | 0.97 | 0.82 to 1.14 | 0.683 |

| Lower (vs upper) | 1.05 | 0.89 to 1.24 | 0.566 | 1.05 | 0.90 to 1.23 | 0.532 |

| Whole (vs upper) | 2.98 | 1.53 to 5.83 | 0.001 | 5.35 | 3.11 to 9.20 | <0.001 |

AGC indicates advanced gastric cancer; CI, confidence interval, EGC, early gastric cancer; HR, hazard ratio; PD, poorly differentiated; SRC, signet ring cell carcinoma; WMD, well-to-moderately differentiated.

*Only two EGC patients had ‘whole stomach’ cancers and were therefore excluded from analysis.

Multivariable analysis results for EGC and AGC using Cox's proportional hazard model after adjustments for age, sex, and stage are listed in Table 5 and Supplementary Table 2. SRC (vs WMD) was an independent favorable predictor of recurrence and mortality in EGC (RFS: Cox HR 0.37; 95% CI 0.19 to 0.71; P = 0.003; OS: Cox HR 0.66; 95% CI 0.44 to 0.98; P= 0.041). On the other hand, in AGC, SRC (vs WMD) was an unfavorable predictor of RFS and OS (RFS: Cox HR 1.22; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.46; P = 0.033; OS: Cox HR 1.45; 95% CI 1.22 to 1.71; P < 0.001). In the case of SRC (vs non-SRC), whereas it was an independent favorable predictor of recurrence and mortality in EGC (RFS: Cox HR 0.40; 95% CI 0.21 to 0.76; P = 0.005; OS: Cox HR 0.66; 95% CI 0.45 to 0.99; P = 0.043), it had no significant value in predicting recurrence in AGC (RFS: Cox HR 1.11; 95% CI 0.96 to 1.30; P = 0.170).

TABLE 5.

Multiple Variable Model Predicting Risk of Recurrence and Mortality

| RFS | OS | |||||

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P |

| EGC | ||||||

| Age | 1.02 | 1.00 to 1.03 | 0.072 | 1.08 | 1.07 to 1.09 | <0.001 |

| Female | 0.65 | 0.42 to 1.00 | 0.050 | 0.53 | 0.40 to 0.72 | <0.001 |

| Submucosal invasion | 1.04 | 0.68 to 1.57 | 0.870 | 1.15 | 0.89 to 1.48 | 0.286 |

| LN metastasis | 6.00 | 3.95 to 9.02 | <0.001 | 2.23 | 1.62 to 3.07 | <0.001 |

| Histology and grade | ||||||

| PD (vs WMD) | 0.77 | 0.50 to 1.20 | 0.255 | 0.96 | 0.71 to 1.29 | 0.772 |

| SRC (vs WMD) | 0.37 | 0.19 to 0.71 | 0.003 | 0.66 | 0.44 to 0.98 | 0.041 |

| AGC | ||||||

| Age | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.01 | 0.138 | 1.02 | 1.02 to 1.03 | <0.001 |

| Female | 1.09 | 0.96 to 1.24 | 0.168 | 1.04 | 0.93 to 1.17 | 0.490 |

| AJCC stage | ||||||

| Stage II (vs stage I) | 3.67 | 2.47 to 5.46 | <0.001 | 2.12 | 1.60 to 2.81 | <0.001 |

| Stage III (vs stage I) | 13.87 | 9.52 to 20.21 | <0.001 | 6.89 | 5.32 to 8.93 | <0.001 |

| Histology and grade | ||||||

| PD (vs WMD) | 1.14 | 0.99 to 1.31 | 0.063 | 1.23 | 1.09 to 1.40 | 0.001 |

| SRC (vs WMD) | 1.22 | 1.02 to 1.46 | 0.033 | 1.45 | 1.22 to 1.71 | <0.001 |

AGC indicates advanced gastric cancer; CI, confidence interval, EGC, early gastric cancer; HR, hazard ratio; LN, lymph node; PD, poorly differentiated; RFS, Relapse-free survival; SRC, signet ring cell carcinoma; WMD, well-to-moderately differentiated.

DISCUSSION

Traditionally, gastric cancer has been classified by two morphological differences: intestinal type and diffuse type. In males, intestinal type is more common, and the incidence rises faster with age, whereas diffuse type affects younger people—frequently females. The recent decline in the overall incidence of gastric cancer in Asia stems from the decrease in intestinal type and has been correlated with the corresponding decrease in Helicobacter infestation.9 However, diffuse type, which is uniformly distributed worldwide and continues to increase, is worrisome given that it is thought by Western researchers to have a worse prognosis. Asian researchers have asserted that SRC is not necessarily prognostically worse than non-SRC. However, many of the studies have included only small-sized heterogenous patients including unresected or noncuratively resected cases, early-stage disease, and even metastatic disease. In addition, most studies compared SRC with heterogeneous non-SRC tumors after merging them into a single group. Thus, to the best of our knowledge, this study currently has the largest dataset for SRC analysis in Asia in which we enrolled only patients who were guaranteed to have had D2 dissection and R0 disease, believing that a more clarified natural course of SRC can be obtained from a more homogenous dataset. Furthermore, tubular AC, which comprises the largest portion of gastric cancer, was redivided according to the differentiation, which enables the correction of internal heterogeneity within the group.

We reaffirmed that SRC in an Asian population has distinct features from those of tubular AC. First, the stage distribution at diagnosis was skewed to early-stage, and 60% of SRC cases were EGC. This finding did not align with a previous study that reported a more frequent presentation in late-stage.7 This finding may be largely because of the nationally sponsored screening program. The second feature was the transition of prognosis as disease progressed. Although SRC in EGC had better survival than non-SRC, this was reversed in AGC, with SRC showing a worse prognosis than non-SRC and particularly WMD. These results might suggest that driver mutations controlling the metastatic potential of SRC can occur late in the course of disease. The third feature was early-age onset and a higher female ratio, which was in accordance with previous studies. We observed an onset that was about 7 years earlier in SRC patients than in tubular AC patients, and over half of the patients were female, despite the fact that gastric cancer is widely known to be a male-dominant cancer. All of these findings strengthen the idea that SRC is a form of disease distinct from tubular AC.10–12

The characteristics and prognosis of SRC mentioned above are similar to those suggested in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC). HDGC is a disease inherited by autosomal dominant patterns and is characterized by the early-age onset of SRC. SRC in HDGC has the unique characteristic of being indolent in the mucosal layer for a prolonged period at early stages, although eventually displaying aggressive phenotypes, and such traits of HDGC are similar to those shown by SRC in this study. The E-cadherin (CDH1) gene was reported to be relevant to HDGC; however, the germ-line mutation of the CDH1 gene comprised only 1% to 3% of gastric cancer.13,14 However, recently published studies have revealed that somatic mutations of the CDH1 gene are also relevant to diffuse-type gastric cancer.15,16 Therefore, further study is warranted to provide clues regarding the genetic alterations of SRC and its drastic prognosis change.

We believe that stage-adjusted analysis is important in clarifying the prognosis of SRC, which may explain why Western countries that have low EGC prevalence have reported that SRC has a poor prognosis. However, Asian countries that have a widely accepted early detection program, a standardized surgical procedure, and prevailing adjuvant therapy have recently criticized this idea. They have tried to compare the prognosis between SRC and non-SRC; however, the small sample size has been a limitation.6,17,18 A recent American study utilizing Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data adopted stage adjustment to overcome these limitations and demonstrated that SRC is not a negative prognostic indicator.7 However, a large proportion of the patients did not undergo surgical resection, meaning that concerns exist with respect to the reliability of stage and the application of the exact definition of SRC. In addition, it compared SRC with non-SRC after merging non-SRC tumors into a single group for outcome comparison, which is an oversimplification of this heterogeneous disease. This study also demonstrated that SRC confers worse prognosis than WMD in AGC. However, this difference in prognosis was not observed when SRC was compared with non-SRC tumors in terms of recurrence, as PD that has a similar prognosis to that of SRC in AGC was included in the non-SRC group. In this aspect, our study was in line with the report by Bamboat et al,8 which, despite its small sample size, suggested that the prognosis of SRC could be stage-dependent.

Another point of this study was the fact that long-term survival data was used, including recurrence status (collected from a close follow-up program); however, this data also limited our study because of the retrospective nature of its collection. In addition, this study only included patients with surgically resected cancer and did not involve patients with metastatic disease, limiting our knowledge of the full spectrum of SRC. However, as patients with stage IV disease are treated with palliation-aimed chemotherapy, they may show different prognoses; thus, another study that analyzes this particular cohort of patients is needed. Another limitation of the current study was the differences in gastric cancer biology between Eastern and Western countries. Because this study was performed only with Asians, the presented data cannot represent the characteristics of western gastric cancer, where cancers of esophagogastric junction and upper stomach were predominant. Therefore, further stage-adjusted studies for western SRC gastric cancer are required to confirm the findings of the current study.

CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests that early-stage SRC could be indolent, demonstrating that more than half of SRC cases are presented as EGC. In addition, SRC in EGC confers a more favorable prognosis after curative resection than WMD. On the other hand, SRC in AGC bestows a worse prognosis than WMD. Therefore, the context-dependent nature of SRC must be considered when predicting its prognostic impact.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors deeply appreciate the great help provided by the Gastric Cancer Center Team, the clinical research coordinator, and the pathology team in Yonsei Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Disclosure: This study was supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (1420060), the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI13C2096), and the Research Driven Hospital R&D project, funded by the CHA Bundang Medical Center (grant number: BDCHA R&D 2015-38).

Authors’ contributions: H.C.J., H.J.C., and W.J.H. contributed in the study concept, design, and supervision. H.C.J., H.J.C., W.J.H., S.H.N. contributed in the acquisition of data. H.C.J., H.J.C., W.J.H., S.P., H.K., C.K., C.H.P., J.H.K., J.B.A., H.C.C., S.Y.R., and S.H.N. contributed in the analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript. H.C.J., H.J.C., W.J.H., S.P., C.K., C.H.P., J.H.K., J.B.A., H.C.C., S.Y.R., and S.H.N. contributed in the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. H.C.J., H.J.C., W.J.H., S.P., and C.K. contributed in the statistical analysis of the study. H.C.J. obtained funding, technical, and material support.

H.J.C and W.J.H. contributed equally to this work as co-first authors

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization, Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, et al. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma, an attempt at a histoclinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 1965; 64:31–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ribeiro MM, Sarmento JA, Simoes M, et al. Prognostic significance of Lauren and Ming classifications and other pathologic parameters in gastric carcinoma. Cancer 1981; 47:780–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piessen G, Messager M, Leteurtre E, et al. Signet ring cell histology is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma regardless of tumoral clinical presentation. Ann Surg 2009; 250:878–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyung WJ, Noh SH, Lee JH, et al. Early gastric carcinoma with signet ring cell histology. Cancer 2002; 94:78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kunisaki C, Shimada H, Nomura M, et al. Therapeutic strategy for signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach. Brit J Surg 2004; 91:1319–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taghavi S, Jayarajan SN, Davey A, et al. Prognostic significance of signet ring gastric cancer. J Clinic Oncol 2012; 30:3493–3498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bamboat ZM, Tang LH, Vinuela E, et al. Stage-stratified prognosis of signet ring cell histology in patients undergoing curative resection for gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2014; 21:1678–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi Y, Gwack J, Kim Y, et al. Long term trends and the future gastric cancer mortality in Korea: 1983– 2013. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2006; 38:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah MA, Khanin R, Tang L, et al. Molecular classification of gastric cancer: a new paradigm. Clinical Cancer Res 2011; 17:2693–2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lei Z, Tan IB, Das K, et al. Identification of molecular subtypes of gastric cancer with different responses to PI3-kinase inhibitors and 5-fluorouracil. Gastroenterology 2013; 145:554–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chon HJ, Kim HR, Shin E, et al. The clinicopathologic features and prognostic impact of ALK positivity in patients with resected gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22:3938–3945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Humar B, Guilford P. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: a manifestation of lost cell polarity. Cancer Sci 2009; 100:1151–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blair V, Martin I, Shaw D, et al. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: diagnosis and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4:262–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee Y-S, Cho YS, Lee GK, et al. Genomic profile analysis of diffuse-type gastric cancers. Genome Biol 2014; 15:R55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang K, Yuen ST, Xu J, et al. Whole-genome sequencing and comprehensive molecular profiling identify new driver mutations in gastric cancer. Nature Genet 2014; 46:573–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim DY, Park YK, Joo JK, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach. ANZ J Surg 2004; 74:1060–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon K-J, Shim K-N, Song E-M, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach. Gastric Cancer 2014; 17:43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.