Abstract

Objective

Hippocampal sclerosis of aging (HS-Aging) is a common cause of dementia in older adults. We tested the variability in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) proteins associated with previously identified HS-Aging risk single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

Methods

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative cohort (ADNI; n=237) data, combining both multiplexed proteomics CSF and genotype data, were used to assess the association between CSF analytes and risk SNPs in four genes (SNPs): GRN (rs5848), TMEM106B (rs1990622), ABCC9 (rs704180), and KCNMB2 (rs9637454). For controls, non-HS-Aging SNPs in APOE (rs429358/rs7412) and MAPT (rs8070723) were also analyzed against Aβ1-42 and total tau CSF analytes.

Results

The GRN risk SNP (rs5848) status correlated with variation in CSF proteins, with the risk allele (T) associated with increased levels of AXL Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (AXL), TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand Receptor 3 (TRAIL-R3), Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and clusterin (CLU) (all p<0.05 after Bonferroni correction). The TRAIL-R3 correlation was significant in meta-analysis with an additional dataset (p=5.05×10−5). Further, the rs5848 SNP status was associated with increased CSF tau protein – a marker of neurodegeneration (p=0.015). These data are remarkable since this GRN SNP has been found to be a risk factor for multiple types of dementia-related brain pathologies.

Keywords: proteomics, granulin, progranulin, Clusterin, neuroinflammation, biomarkers

INTRODUCTION

Studies of CSF analytes may provide biomarkers for dementia subtyping and also may provide clues about brain disease pathogenesis. These biomarker studies are all the more important as there are clearly many diseases in addition to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) that underlie the clinical syndrome of dementia. Presently, individual AD “mimics” are challenging in any given patient to rule in or out. Clinical studies using neuroimaging and CSF analyses have identified a subset of individuals with evidence of neurodegeneration but lacking features of AD-type amyloidogenesis according to neuroimaging or biofluid studies. These cases have been termed “SNAP” (suspected non-amyloid pathology) and this biomarker profile has been observed in approximately 1/4th of cognitively impaired individuals (Jack et al., 2016)

Hippocampal sclerosis of aging (HS-Aging) is among the most common of the AD mimics (Nelson et al., 2013, Zarow et al., 2012), and prior studies emphasize the public health impact of this high-morbidity SNAP-type brain condition. HS-Aging is diagnosed at autopsy when neuron loss and astrocytosis are observed in the hippocampal formation, out of proportion to AD-type plaques and tangles (Amador-Ortiz et al., 2007a, Montine et al., 2012, Nelson et al., 2013). Unlike other diseases that share the diagnostic label of “hippocampal sclerosis”, HS-Aging is distinguished clinically by the advanced age of the individuals afflicted, and by the usual lack of either seizure disorder or frontotemporal dementia symptoms clinically (Amador-Ortiz et al., 2007b, Lee et al., 2008, Nelson et al., 2011, Neumann et al., 2006, Wilson et al., 2013). Further, HS-Aging has a pathological biomarker: TDP-43 pathology (Amador-Ortiz et al., 2007b). HS-Aging affects up to 25% of the “oldest-old” (Leverenz et al., 2002, Nelson et al., 2011, Nelson et al., 2013, Zarow et al., 2012) and is associated with substantial disease-specific cognitive impairment (Brenowitz W. D. et al., 2014, Nelson et al., 2010). Even at state-of-the-art research institutions, HS-Aging tends to be misdiagnosed as AD clinically because of overlapping symptoms (Brenowitz et al., 2014, Nelson et al., 2011, Pao et al., 2011).

Genetic risk factors for HS-Aging have recently been characterized, comprising four specific gene variants that are the focus of the present study. The genes that harbor these risk-associated variants are: GRN, TMEM106B, ABCC9, and KCNMB2. The goal of the present study was to test the hypothesis that the specific gene variants associated with HS-Aging pathology also are associated with variation in the biochemical composition of CSF.

In terms of the specific risk alleles, gene-focused studies found that SNPs were associated with HS-Aging that previously had been linked to frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP-43 inclusions (FTLD-TDP), namely rs5848 (GRN) and rs1990622 (near TMEM106B) (Dickson D. W. et al., 2010, Murray et al., 2014, Rutherford et al., 2012, Van Langenhove et al., 2012). The GRN SNP was subsequently linked to other dementia-inducing disorders (Chang et al., 2013, Galimberti et al., 2012, Kamalainen et al., 2013, Pickering-Brown et al., 2008, Rademakers et al., 2008). Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) using large datasets have implicated two genes that encode potassium channel regulators — ABCC9 (rs704180) and KCNMB2 (rs9637454) – in HS-Aging pathology (Beecham et al., 2014, Nelson et al., 2014). Collectively these prior studies indicate that non-AD genes may have a strong impact on elderly individuals’ brain structure and function, but much remains to be learned about these genes’ roles in health and disease states. In contrast to AD, APOE gene variants are not associated with altered risk for HS-Aging (Brenowitz et al., 2014, Leverenz et al., 2002, Nelson et al., 2011, Pao et al., 2011, Troncoso et al., 1996), indicating that HS-Aging is a separate disease entity from AD.

The goal of the present study was to test the hypothesis that variability in CSF analytes is associated with HS-Aging risk alleles in a population of older adults, many of whom are cognitively impaired. This study analyzed data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) cohort and the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) at Washington University Cohort. The CSF came from lumbar punctures in patients spanning the clinical spectrum from normal to demented subjects (see (Ayton et al., 2015, Kang et al., 2015)), and the average age of the research subjects when the samples were obtained was approximately 75 years. Our data provides support for the hypothesis that the GRN gene variant rs5848 is associated with neuroinflammatory brain changes in older adults.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the ADNI database (adni.loni.ucla.edu). The ADNI was launched in 2003 as a public-private partnership (Principal Investigator Michael W. Weiner). The original ADNI study aimed to recruit 800 adults, ages 55 to 90, to participate in the research to test whether serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early AD. Participants at each site provided informed written consent, and protocols were approved by the respective Institutional Review Boards (Petersen et al., 2010). We retrieved data from the ADNI database in September 2015. CSF data for the present study resulted from the ADNI Biomarkers Consortium Project “Use of Targeted Multiplex Proteomic Strategies to Identify Novel CSF Biomarkers in AD” which includes quantitative data on 83 separate CSF analytes from 310 individuals after quality control (QC) as detailed in the ADNI CSF protocol (the pre-QC data included 159 analytes from a MyriadRBM multiplex assay as discussed later). We also downloaded biomarker, genetic, demographic and diagnosis data and required that each participant have at most one genotype missing, resulting in a total of 237 participants’ data being analyzed in the present study. (Petersen et al., 2010) This is detailed in the Genotypes and Imputation section and Supplemental Figure 1.

CSF Measurements

Collection and processing of ADNI CSF samples was described in detail elsewhere (Jagust et al., 2009, Shaw et al., 2011)(adni.loni.ucla.edu). The Myriad RBM (Mattsson et al., 2014) panel of 159 CSF analytes was processed on 337 samples, including 1 from a participant without diagnosis and 16 replicated samples used for test/retest QC. Analytes were filtered for sufficient dose, precision and reproducibility and were then log-transformed to better approximate a normal distribution. This resulted in a total of 83 post-QC CSF analytes from the MyriadRBM assay. Total tau and Aβ1-42 were assayed separately (Jagust et al., 2009). In cases where repeated lumbar punctures were performed, only the first measurement was used in the present study. Descriptive measures of these analytes across the 237 individuals with sufficient genotype data are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Genotyping and Imputation

The most recently generated GWAS genotyping data was acquired from the ADNI database September 2015. These data underwent extensive QC as part of the AD Big Data DREAM Challenge (Allen et al., 2016) (https://www.synapse.org/#!Synapse:syn2290704/wiki/60828). Briefly, samples from Illumina Human610-Quad BeadChip and Illumina HumanOmniExpress BeadChip arrays were mapped to hg19, converted to the positive strand and filtered for minor allele frequency (removed MAF<0.05), SNP call rate (<0.98), sample call rate (<0.98), Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p<0.001) and relatedness. SNPs and samples passing QC were then pre-phased using SHAPEITv2(O’Connell et al., 2014) and imputed to 1000 Genomes Phase 1 reference panel using default QC parameters (IMPUTE2 (Howie et al., 2012)).

To screen for potential ethnic outliers and protect against any potential subsequent spurious association, we LD pruned the GWAS data and examined principal component (PC) plots with 1000 Genomes data from the 5 “super populations” (African-AFR, Admixed American-AMR, East Asian-EAS, European-EUR and South Asian-SAS; Supplemental Figure 4). No outliers were discovered, and PCs were retained for adjustment in regression models.

Statistical Analysis

In order to discern correlations between HS-Aging genetic variants and the quantitative levels of CSF measurements, we performed linear regression analysis of each of the 83 post-QC log-transformed CSF analytes separately on each of the four HS-Aging SNPs. This was conducted both without adjustment (i.e., marginally) and also correcting for gender, diagnosis, age at lumbar puncture, years of education and the first three PCs. The analysis was done with and without covariate adjustment as sensitivity analysis for potential confounding. In additional to these primary analyses, the positive controls of APOE-ε4 with Aβ1-42 and MAPT haplotypes with total tau were also analyzed similarly. Although a log transformation had already been made in the primary CSF data, any remaining violations of the normal distributional assumption (per a Shapiro-Wilks test for non-normality) were adjusted with a Box-Cox transformation.

Since 83 individual CSF analytes were tested for association with each of the four HS-Aging risk SNPs, we used a Bonferroni correction and considered any result significant when p < 1.5×10−4 (=0.05/(83*4)). We underscore that this is a conservative approach, especially since the Bonferroni correction explicitly assumes uncorrelated tests, although many of the analytes are fairly highly correlated (Supplemental Figure 2).

In addition to the primary analyses, additional analyses were performed after noting that the GRN SNP was significantly associated with several CSF analytes from the Myriad RBM panel: we investigated the relationship of this SNP with Aβ1-42 and total tau in the same regression framework.

Replication Analysis

A post-hoc analysis was performed that included analogous CSF and genotype data from 286 subjects in the Knight ADRC at Washington University. All study-wide significant CSF/SNP relationships were meta-analyzed with Knight-ADRC data using the same statistical model and a inverse-variance weighted estimator to combine results.

RESULTS

Subject demographics by diagnosis for the final data set are presented in Table 1. Age of individuals at the time of CSF draw was approximately the same, 75 years, whether the patients were cognitive normal, MCI, or demented (p=0.44). Genotype SNP counts are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Sample demographics by diagnosis. Categorical outcomes were tested using a chi-square test. Continuous outcomes were tested with one-way ANOVA. An asterisk (*) denotes significance at α=0.05. Double asterisks (**) denote significance at α=5 × 10−8. NL = normal controls; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; AD = Alzheimer’s disease; LP = lumbar puncture; Aβ1-42 is the 42-residue peptide of Aβ (Naslund et al., 1994).

| NL | MCI | AD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 63 | 119 | 55 |

| Female (%)* | 46% | 29% | 45% |

| Age at LP | 75.8 (4.8) | 74.9 (7.1) | 74.2 (7.6) |

| Years of Education | 15.9 (2.7) | 16.0 (3.0) | 15.0 (3.1) |

| APOE-ε4 carrier (%)** | 22% | 55% | 75% |

| Aβ1-42 (pg/mL)** | 206.09 (56.89) | 156.68 (48.94) | 140.98 (34.40) |

| Total tau (pg/mL)** | 69.5 (24.79) | 104.37 (47.63) | 125.25 (62.47) |

Table 2.

Genotype/diplotype counts by SNP. APOE = Apolipoprotein E; ABCC9 = ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily C Member 9; TMEM106B = Transmembrane Protein 106B; GRN = Granulin; KCNMB2 = Potassium Calcium-Activated Channel Subfamily M Regulatory Beta Subunit 2; MAPT = Microtubule Associated Protein Tau. APOE genotypes are comprised of ε2, ε3, and ε4 alleles; for example, the first row (22) gives the count (0) of individuals with two ε2 alleles (ε2/ε2). MAPT diplotypes are defined by extended haplotypes, H1 and H2, using the SNP rs8070723.

| SNP | Chromosome | Position (bp) | Gene | Genotype/Diplotype | Count | Minor allele frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs7412/ rs429358 |

19 19 |

44908822/ 44908684 |

APOE | 22 | 0 | 0.044 |

| 23 | 18 | |||||

| 24 | 3 | |||||

| 33 | 98 | |||||

| 34 | 89 | |||||

| 44 | 29 | |||||

| rs704180 | 12 | 21994111 | ABCC9 | 0.485 | ||

| AA | 57 | |||||

| AG | 114 | |||||

| GG | 64 | |||||

| rs1990622 | 7 | 12283787 | TMEM106B | 0.416 | ||

| CC | 83 | |||||

| CG | 111 | |||||

| GG | 43 | |||||

| rs5848 | 17 | 42430244 | GRN | 0.327 | ||

| CC | 99 | |||||

| CT | 98 | |||||

| TT | 23 | |||||

| rs9637454 | 3 | 178257562 | KCNMB2 | 0.278 | ||

| GG | 118 | |||||

| AG | 96 | |||||

| AA | 16 | |||||

| rs8070723 | 17 | 44081064 | MAPT | 0.192 | ||

| H1/H1 | 150 | |||||

| H1/H2 | 79 | |||||

| H2/H2 | 8 |

= APOE

Significant Associations between CSF Analytes and HS-Aging SNPs

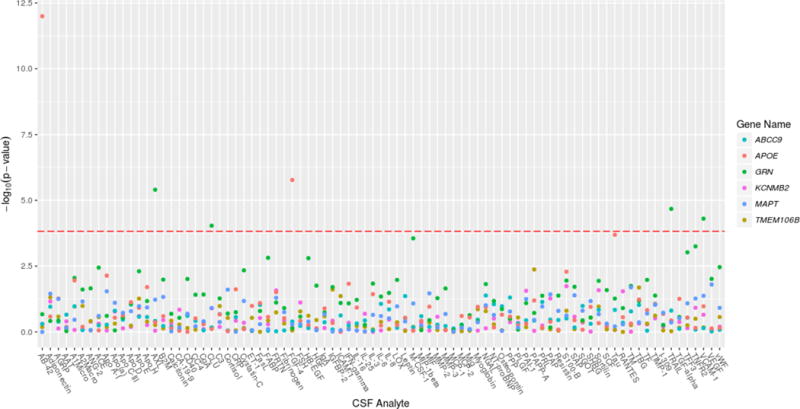

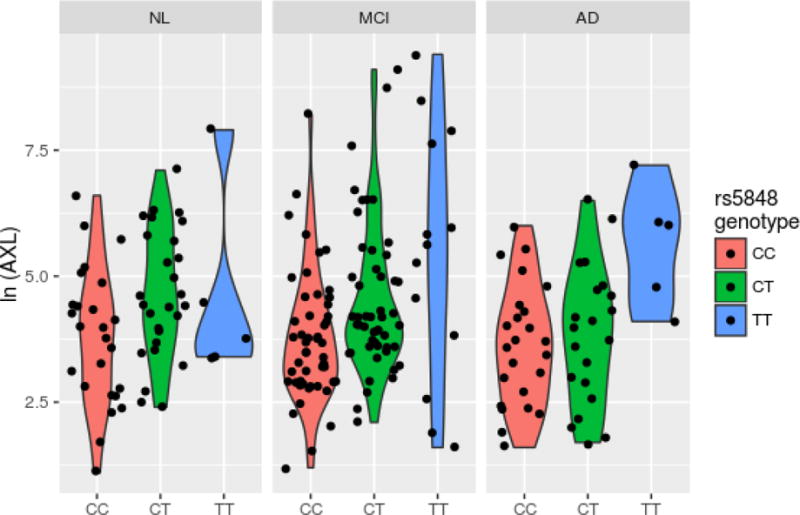

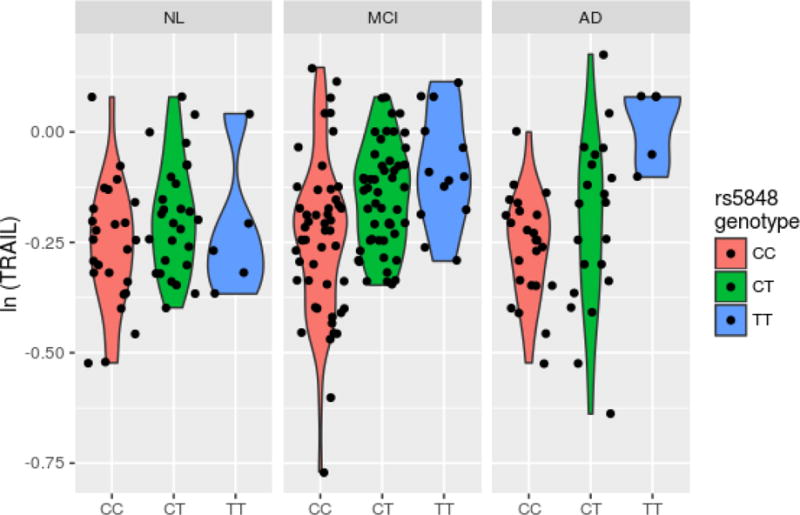

The Manhattan-type plot (Figure 1) displays log-transformed p-values for each CSF/SNP combination from regressing CSF on the SNPs’ status with adjustment for other covariates (gender, diagnosis, age at lumbar puncture, years of education, and the first 3 principal components). Marginal results, i.e., without covariate adjustment, were similar and are not shown. The most significant association observed was for the positive control APOE-ε4 with Aβ1-42 (p = 3.5×10−12). The only HS-Aging gene to reach statistical significance with any CSF analyte after multiple testing adjustment was GRN (rs5848_T), which revealed four study-wide significant correlations. Table 3 shows these results along with the corresponding parameter estimates from the adjusted model. For example, an additional copy of the rs5848 T allele confers an estimated >2-fold increase (2.02 = e0.704) of AXL after adjustment for gender, diagnosis, age at lumbar puncture and the first three principal components. The distributions of AXL measures by rs5848 genotype and diagnosis are shown in Figure 2A, displaying the pattern of increased protein for each T allele. This is also shown for TRAIL-R3 (Figure 2B), which is the only analyte that was study-wide significant after meta-analysis with the Knight ADRC data (p=5.05×10−5). No HS-Aging gene other than GRN reached study-wide statistical significance with the conservative Bonferroni adjustment (incorporating the study design of 83 analytes × 4 SNPs assessed = 332 hypothesis tests). Supplementary Table 2 displays regression results for the top 4 associations for each of the other HS-Aging genes using nominal (uncorrected) p values.

Figure 1.

Manhattan plot of all CSF analytes for each SNP. Linear regression results from each pair of log-transformed CSF analyte and SNP adjusted for gender, diagnosis, years of education, age at lumbar puncture and the first 3 principal components. Positive control variables are included with those from the primary analysis. These genes (SNPs) were tested: ABCC9 (rs704180), APOE (rs429358/rs7412), GRN (rs5848), KCNMB2 (rs9637454), MAPT (rs8070723), and TMEM106B (rs1990622).

Table 3.

Significant CSF/SNP correlations. All significant results after Bonferroni adjustment were with the GRN SNP (rs5848_T). The parameter estimates (beta and std. err.) reflect the log-transformations of CSF analytes and can be exponentiated for a fold-change interpretation after adjustment for gender, diagnosis, years of education, age at lumbar puncture and the first 3 principal components. AXL = AXL Receptor Tyrosine Kinase; TRAIL-R3 = TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand Receptor 3; VCAM-1 = Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1; CLU = clusterin.

| CSF Analyte | beta est. | std. err. | Nominal p-value | Bonferroni-corrected p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AXL | 0.704 | 0.149 | 3.95E-06 | 0.001 |

| TRAIL-R3 | 0.064 | 0.015 | 2.11E-05 | 0.007 |

| VCAM-1 | 0.052 | 0.013 | 4.96E-05 | 0.016 |

| CLU | 0.062 | 0.016 | 9.19E-05 | 0.031 |

Figure 2A.

Violin plot of top hit CSF/SNP combination stratified by diagnosis as determined by statistical significance.

Figure 2B.

Violin plot of second hit by significance.

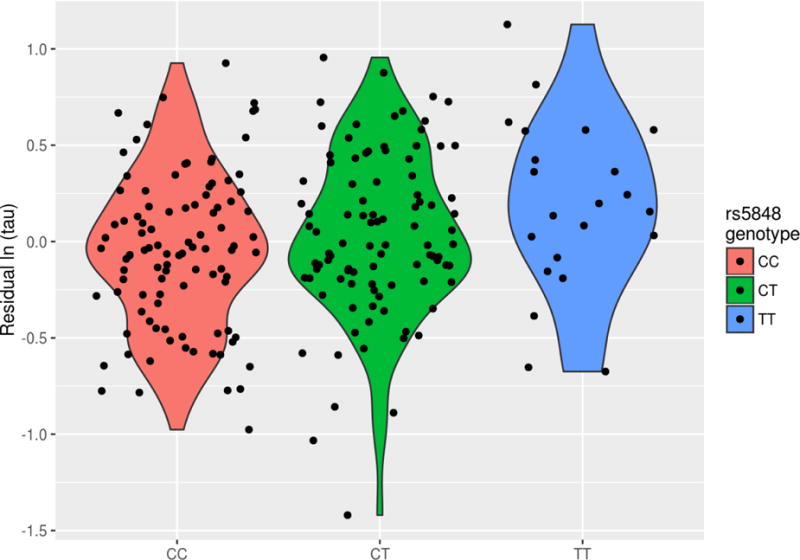

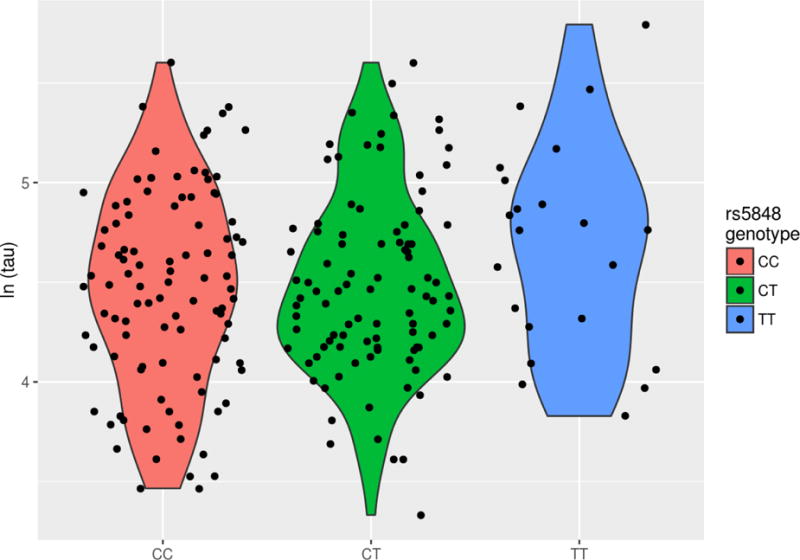

Since the GRN rs5848_T allele was associated with CSF analytes from the RBM panel, we examined it in relation to tau and Aβ1-42, two canonical AD biomarkers, specifically to determine if the allele was associated with tau for a given level of Aβ1-42. In a model regressing tau level on the other covariates including Aβ1-42, the GRN risk allele showed association with tau levels (p=0.015). Both biomarkers were log-transformed in the model due to skewness. Interestingly, without the adjustment for Aβ1-42, the SNP is no longer nominally significantly associated with total tau levels (p=0.054). We show the residuals from a regression of log(tau) on Aβ1-42 and the adjustment covariates (Figure 3A) and the unadjusted log(tau) values (Figure 3B) against GRN genotype.

Figure 3A.

Residuals of log-transformed tau vs. GRN genotype. Residuals from a model regressing log-transformed tau on Aβ1-42, gender, diagnosis, years of education, age at lumbar puncture and the first 3 principal components.

Figure 3B.

Unadjusted log-transformed tau vs. GRN genotype.

DISCUSSION

We here report that the GRN risk SNP (rs5848) was associated with variation in detected levels of CSF proteins previously implicated in CNS inflammation in the ADNI data set (Aktas et al., 2007). The same GRN risk allele was also associated with increased CSF tau which may indicate directly related neurodegenerative changes. We found no direct evidence that other putative HS-Aging risk variants are associated with variation in CSF proteins in these samples.

An important caveat in interpreting our results is the limited sample size (n=237 patients included) given the number of variables (83 analytes) being assessed. This sample size confers 80% power to detect an additive CSF analyte effect of 1.21 standard deviations with a nominal 5% level of significance, when adjusting for the 4*83=332 hypothesis tests. Among the additional sources of variability is the fact that the research subjects span a broad spectrum of clinical states from “normal” to “dementia”, which in itself probably introduces substantial variability related to patient activity, medication, diet, and other factors. There may be additional sources of variation due to possible preanalytical variables since the samples were collected from dozens of different clinical locations (see Methods). Moreover, the non-Aβ (i.e., non-AD) pathogenetic elements in large autopsy series include α-synucleinopathy and primary age-related tauopathy (PART) which add to the phenotypic complexity (see for example Neltner et al. (2016)). These factors argue for caution in interpreting our data and heighten the likelihood of false-negative results; the study design is best tailored for high effect-size phenomena. Further, the CSF samples were obtained from relatively young individuals considering the age range of vulnerability to HS-Aging(Nelson et al., 2013). Another caveat relates to the basic characteristic of the ADNI cohort which is enriched for persons with AD risk per se. Multiple studies have found that HS-Aging tends to misdiagnosed as AD in the clinical setting (Brenowitz Willa D. et al., 2014, Pao et al., 2011). However, we also note that the ADNI data set has been used productively by many other researchers to test hypotheses related to potential dementia biomarkers.

As far as we know this is the first study of CSF analytes in relation to HS-Aging genetic risk factors. The first gene variant to be linked to HS-Aging pathology, rs5848 (Rademakers et al., 2008) is physically located in the 3′ untranslated region of the GRN mRNA. The risk allele is associated with decreased plasma expression of GRN/PGRN (Dickson Dennis W. et al., 2010, Fenoglio et al., 2009).

Our results can be interpreted from different perspectives, reflecting how much is currently unknown. Whereas multiple GRN mutations cause FTLD-TDP (184–188), rs5848 is apparently a disease-modifying allele that alters the manifestation of multiple different diseases rather than affecting FTLD or HS-Aging specifically. For example, rs5848 has been linked to AD, Parkinson’s disease, C9ORF72 neurodegeneration, and bipolar disorder (Chang et al., 2013, Galimberti et al., 2012, Kamalainen et al., 2013, Pickering-Brown et al., 2008, Rademakers et al., 2008, van Blitterswijk et al., 2014). Moreover, the SNAP profile – biomarker indication of a neurodegenerative process despite lack of Aβ-type amyloidogenesis – is linked to multiple different brain conditions. Hypothetically, one could have “neurodegeneration” in the CNS without tau protein in the CSF, especially in a disease like HS-Aging where the cell loss may occur without substantial tauopathy. The present study for the first time ties rs5848 related brain changes with increased CSF analytes in addition to CSF tau, indicating that neurodegeneration linked to TDP-43 pathology (the most specific pathological marker of HS-Aging) leads to increased CSF tau that can be detected in a complex background. A prior study reported that rs5848 status and PGRN levels in CSF were linked to CSF tau variance (Morenas-Rodriguez et al., 2015), whereas another study found that GRN mutant FTLD cases lacked increased tau in CSF (Carecchio et al., 2011).

Also interesting is the subset of CSF analytes that were found to be altered in association with rs5848 genotypes; these include AXL, TRAIL-R3, VCAM-1 and CLU. Each of these gene products has been the subject of extensive research, and collectively the prior studies appear to point towards a common theme that also is relevant to GRN itself. GRN has been implicated in microglial function and neuroinflammation (Cenik et al., 2012, Jian et al., 2013), and each of the above mentioned protein products also can be linked to neuroinflammatory pathways. For example, CLU (clusterin, also known as apolipoprotein J) has been described to play a role in microglial activation and Aβ uptake (Mulder et al., 2014, Xie et al., 2005). Since GRN is a risk factor for FTLD-TDP, with extensive TDP-43 pathology, as well as HS-Aging, which seems to be a different disease, it is possible that the GRN/PGRN protein and neuroinflammation play a contributory role in TDP-43 pathology per se. However, more work is required to test this hypothesis. Whether the analytes themselves are pathogenetic agents is another important question that remains to be answered.

We conclude that among subjects with CSF analyte and genotype data available in the ADNI cohort, the HS-Aging risk gene variants are mostly not found to be associated with CSF protein changes. However, the GRN risk SNP rs5848 shows some analyte variation that indicate high effect sizes, perhaps linked to neuroinflammatory phenotype. We now know that dementia has many causes and multiple pathologic comorbodities often are simultaneously expressed in elderly individuals. Future studies may elucidate other links between non-AD risk alleles and biomarkers to enable better diagnoses and to thus strengthen our ability to develop and test future therapeutic strategies.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

GRN SNP (rs5848) genotypes correlate with variation in several CSF proteins GRN genotype associated with altered CSF tau protein after controlling for Aβ1-42 Related gene products have been linked with neuroinflammatory pathways Genetically-driven non-Alzheimer’s conditions have impact on aged persons’ brains

Acknowledgments

We are profoundly grateful to the research volunteers and clinicians that enabled us to perform these studies. This work was supported by the following National Institute of Health [grant numbers K25 AG043546, P30 AG028383, R01-AG044546, P01-AG003991, RF1AG053303, R01-AG035083, and R21 AG050146]. Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California. This research was also supported by NIH grants P30 AG010129, K01 AG030514, and the Dana Foundation. Samples from the National Cell Repository for AD (NCRAD), which receives government support under a cooperative agreement grant (U24 AG21886) awarded by the National Institute on Aging (AIG), were used in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aktas O, Schulze-Topphoff U, Zipp F. The role of TRAIL/TRAIL receptors in central nervous system pathology. Front Biosci. 2007;12:2912–21. doi: 10.2741/2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GI, Amoroso N, Anghel C, Balagurusamy V, Bare CJ, Beaton D, et al. Crowdsourced estimation of cognitive decline and resilience in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amador-Ortiz C, Ahmed Z, Zehr C, Dickson DW. Hippocampal sclerosis dementia differs from hippocampal sclerosis in frontal lobe degeneration. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2007a;113(3):245–52. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0183-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amador-Ortiz C, Lin WL, Ahmed Z, Personett D, Davies P, Duara R, et al. TDP-43 immunoreactivity in hippocampal sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2007b;61(5):435–45. doi: 10.1002/ana.21154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayton S, Faux NG, Bush AI, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. Ferritin levels in the cerebrospinal fluid predict Alzheimer’s disease outcomes and are regulated by APOE. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6760. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beecham GW, Hamilton K, Naj AC, Martin ER, Huentelman M, Myers AJ, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis of neuropathologic features of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(9):e1004606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenowitz WD, Monsell SE, Schmitt FA, Kukull WA, Nelson PT. Hippocampal sclerosis of aging is a key Alzheimer’s disease mimic: clinical-pathologic correlations and comparisons with both alzheimer’s disease and non-tauopathic frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;39(3):691–702. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenowitz WD, Monsell SE, Schmitt Fa, Kukull Wa, Nelson PT. Hippocampal sclerosis of aging is a key Alzheimer’s disease mimic: clinical-pathologic correlations and comparisons with both alzheimer’s disease and non-tauopathic frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD. 2014;39(3):691–702. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carecchio M, Fenoglio C, Cortini F, Comi C, Benussi L, Ghidoni R, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in Progranulin mutations carriers. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;27(4):781–90. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-111046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenik B, Sephton CF, Kutluk Cenik B, Herz J, Yu G. Progranulin: a proteolytically processed protein at the crossroads of inflammation and neurodegeneration. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(39):32298–306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.399170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang KH, Chen CM, Chen YC, Hsiao YC, Huang CC, Kuo HC, et al. Association between GRN rs5848 polymorphism and Parkinson’s disease in Taiwanese population. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson DW, Baker M, Rademakers R. Common variant in GRN is a genetic risk factor for hippocampal sclerosis in the elderly. Neurodegener Dis. 2010;7(1–3):170–4. doi: 10.1159/000289231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson DW, Baker M, Rademakers R. Common variant in GRN is a genetic risk factor for hippocampal sclerosis in the elderly. Neuro-degenerative diseases. 2010;7(1–3):170–4. doi: 10.1159/000289231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenoglio C, Galimberti D, Cortini F, Kauwe JS, Cruchaga C, Venturelli E, et al. Rs5848 variant influences GRN mRNA levels in brain and peripheral mononuclear cells in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18(3):603–12. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galimberti D, Dell’Osso B, Fenoglio C, Villa C, Cortini F, Serpente M, et al. Progranulin gene variability and plasma levels in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e32164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, Abecasis GR. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nat Genet. 2012;44(8):955–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Chetelat G, Dickson D, Fagan AM, Frisoni GB, et al. Suspected non-Alzheimer disease pathophysiology - concept and controversy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagust WJ, Landau SM, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Koeppe Ra, Reiman EM, et al. Relationships between biomarkers in aging and dementia. Neurology. 2009;73(15):1193–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bc010c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jian J, Konopka J, Liu C. Insights into the role of progranulin in immunity, infection, and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;93(2):199–208. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0812429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamalainen A, Viswanathan J, Natunen T, Helisalmi S, Kauppinen T, Pikkarainen M, et al. GRN variant rs5848 reduces plasma and brain levels of granulin in Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(1):23–7. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JH, Korecka M, Figurski MJ, Toledo JB, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative 2 Biomarker Core: A review of progress and plans. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(7):772–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EB, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Neumann M. TDP-43 immunoreactivity in anoxic, ischemic and neoplastic lesions of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115(3):305–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0331-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverenz JB, Agustin CM, Tsuang D, Peskind ER, Edland SD, Nochlin D, et al. Clinical and neuropathological characteristics of hippocampal sclerosis: a community-based study. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(7):1099–106. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.7.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson N, Insel P, Nosheny R, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Jack CR, Jr, et al. Effects of cerebrospinal fluid proteins on brain atrophy rates in cognitively healthy older adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(3):614–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morenas-Rodriguez E, Cervera-Carles L, Vilaplana E, Alcolea D, Carmona-Iragui M, Dols-Icardo O, et al. Progranulin Protein Levels in Cerebrospinal Fluid in Primary Neurodegenerative Dementias. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;50(2):539–46. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder SD, Nielsen HM, Blankenstein MA, Eikelenboom P, Veerhuis R. Apolipoproteins E and J interfere with amyloid-beta uptake by primary human astrocytes and microglia in vitro. Glia. 2014;62(4):493–503. doi: 10.1002/glia.22619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray ME, Cannon A, Graff-Radford NR, Liesinger AM, Rutherford NJ, Ross OA, et al. Differential clinicopathologic and genetic features of late-onset amnestic dementias. Acta Neuropathol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1302-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslund J, Schierhorn A, Hellman U, Lannfelt L, Roses AD, Tjernberg LO, et al. Relative abundance of Alzheimer A beta amyloid peptide variants in Alzheimer disease and normal aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(18):8378–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PT, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Kryscio RJ, Jicha GA, Smith CD, et al. Modeling the association between 43 different clinical and pathological variables and the severity of cognitive impairment in a large autopsy cohort of elderly persons. Brain Pathol. 2010;20(1):66–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PT, Estus S, Abner EL, Parikh I, Malik M, Neltner JH, et al. ABCC9 gene polymorphism is associated with hippocampal sclerosis of aging pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(6):825–43. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1282-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PT, Schmitt FA, Lin Y, Abner EL, Jicha GA, Patel E, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis in advanced age: clinical and pathological features. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 5):1506–18. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PT, Smith CD, Abner EL, Wilfred BJ, Wang WX, Neltner JH, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis of aging, a prevalent and high-morbidity brain disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(2):161–77. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1154-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neltner JH, Abner EL, Jicha GA, Schmitt FA, Patel E, Poon LW, et al. Brain pathologies in extreme old age. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;37:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi MC, Chou TT, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314(5796):130–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell J, Gurdasani D, Delaneau O, Pirastu N, Ulivi S, Cocca M, et al. A general approach for haplotype phasing across the full spectrum of relatedness. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(4):e1004234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pao WC, Dickson DW, Crook JE, Finch NA, Rademakers R, Graff-Radford NR. Hippocampal sclerosis in the elderly: genetic and pathologic findings, some mimicking Alzheimer disease clinically. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25(4):364–8. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31820f8f50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Donohue MC, Gamst AC, Harvey DJ, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology. 2010;74(3):201–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cb3e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering-Brown SM, Rollinson S, Du Plessis D, Morrison KE, Varma A, Richardson AM, et al. Frequency and clinical characteristics of progranulin mutation carriers in the Manchester frontotemporal lobar degeneration cohort: comparison with patients with MAPT and no known mutations. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 3):721–31. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rademakers R, Eriksen JL, Baker M, Robinson T, Ahmed Z, Lincoln SJ, et al. Common variation in the miR-659 binding-site of GRN is a major risk factor for TDP43-positive frontotemporal dementia. Human molecular genetics. 2008;17(23):3631–42. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford NJ, Carrasquillo MM, Li M, Bisceglio G, Menke J, Josephs KA, et al. TMEM106B risk variant is implicated in the pathologic presentation of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2012;79(7):717–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318264e3ac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, Figurski M, Coart E, Blennow K, et al. Qualification of the analytical and clinical performance of CSF biomarker analyses in ADNI. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121(5):597–609. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0808-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troncoso JC, Kawas CH, Chang CK, Folstein MF, Hedreen JC. Lack of association of the apoE4 allele with hippocampal sclerosis dementia. Neurosci Lett. 1996;204(1–2):138–40. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12331-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Blitterswijk M, Mullen B, Wojtas A, Heckman MG, Diehl NN, Baker MC, et al. Genetic modifiers in carriers of repeat expansions in the C9ORF72 gene. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:38. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Langenhove T, van der Zee J, Van Broeckhoven C. The molecular basis of the frontotemporal lobar degeneration-amyotrophic lateral sclerosis spectrum. Ann Med. 2012;44(8):817–28. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2012.665471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Yu L, Trojanowski JQ, Chen EY, Boyle PA, Bennett DA, et al. TDP-43 pathology, cognitive decline, and dementia in old age. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(11):1418–24. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.3961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Harris-White ME, Wals PA, Frautschy SA, Finch CE, Morgan TE. Apolipoprotein J (clusterin) activates rodent microglia in vivo and in vitro. J Neurochem. 2005;93(4):1038–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarow C, Weiner MW, Ellis WG, Chui HC. Prevalence, laterality, and comorbidity of hippocampal sclerosis in an autopsy sample. Brain Behav. 2012;2(4):435–42. doi: 10.1002/brb3.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.