Whole-genome sequences of two novel SARS-CoV-related bat coronaviruses, in addition to a live isolate of a bat SARS-like coronavirus, are reported; the live isolate can infect human cells using ACE2, providing the strongest evidence to date that Chinese horseshoe bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-CoV.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (doi:10.1038/nature12711) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Subject terms: SARS virus

A SARS-like virus in bats

Peter Daszak and colleagues identify two novel coronaviruses from Chinese horseshoe bats that are closely related to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), the cause of a pandemic during 2002 and 2003.

They also isolate a live virus from these bats that has high sequence identity to SARS-CoV and that can infect human cells using ACE2, the same receptor that is used by SARS-CoV. The results provide the strongest evidence to date that horseshoe bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-CoV.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (doi:10.1038/nature12711) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Abstract

The 2002–3 pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) was one of the most significant public health events in recent history1. An ongoing outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus2 suggests that this group of viruses remains a key threat and that their distribution is wider than previously recognized. Although bats have been suggested to be the natural reservoirs of both viruses3,4,5, attempts to isolate the progenitor virus of SARS-CoV from bats have been unsuccessful. Diverse SARS-like coronaviruses (SL-CoVs) have now been reported from bats in China, Europe and Africa5,6,7,8, but none is considered a direct progenitor of SARS-CoV because of their phylogenetic disparity from this virus and the inability of their spike proteins to use the SARS-CoV cellular receptor molecule, the human angiotensin converting enzyme II (ACE2)9,10. Here we report whole-genome sequences of two novel bat coronaviruses from Chinese horseshoe bats (family: Rhinolophidae) in Yunnan, China: RsSHC014 and Rs3367. These viruses are far more closely related to SARS-CoV than any previously identified bat coronaviruses, particularly in the receptor binding domain of the spike protein. Most importantly, we report the first recorded isolation of a live SL-CoV (bat SL-CoV-WIV1) from bat faecal samples in Vero E6 cells, which has typical coronavirus morphology, 99.9% sequence identity to Rs3367 and uses ACE2 from humans, civets and Chinese horseshoe bats for cell entry. Preliminary in vitro testing indicates that WIV1 also has a broad species tropism. Our results provide the strongest evidence to date that Chinese horseshoe bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-CoV, and that intermediate hosts may not be necessary for direct human infection by some bat SL-CoVs. They also highlight the importance of pathogen-discovery programs targeting high-risk wildlife groups in emerging disease hotspots as a strategy for pandemic preparedness.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (doi:10.1038/nature12711) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Main

The 2002–3 pandemic of SARS1 and the ongoing emergence of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)2 demonstrate that CoVs are a significant public health threat. SARS-CoV was shown to use the human ACE2 molecule as its entry receptor, and this is considered a hallmark of its cross-species transmissibility11. The receptor binding domain (RBD) located in the amino-terminal region (amino acids 318–510) of the SARS-CoV spike (S) protein is directly involved in binding to ACE2 (ref. 12). However, despite phylogenetic evidence that SARS-CoV evolved from bat SL-CoVs, all previously identified SL-CoVs have major sequence differences from SARS-CoV in the RBD of their S proteins, including one or two deletions6,9. Replacing the RBD of one SL-CoV S protein with SARS-CoV S conferred the ability to use human ACE2 and replicate efficiently in mice9,13. However, to date, no SL-CoVs have been isolated from bats, and no wild-type SL-CoV of bat origin has been shown to use ACE2.

We conducted a 12-month longitudinal survey (April 2011–September 2012) of SL-CoVs in a colony of Rhinolophus sinicus at a single location in Kunming, Yunnan Province, China (Extended Data Table 1). A total of 117 anal swabs or faecal samples were collected from individual bats using a previously published method5,14. A one-step reverse transcription (RT)-nested PCR was conducted to amplify the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) motifs A and C, which are conserved among alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses15.

Extended Data Table 1.

Summary of sampling detail and CoV prevalence

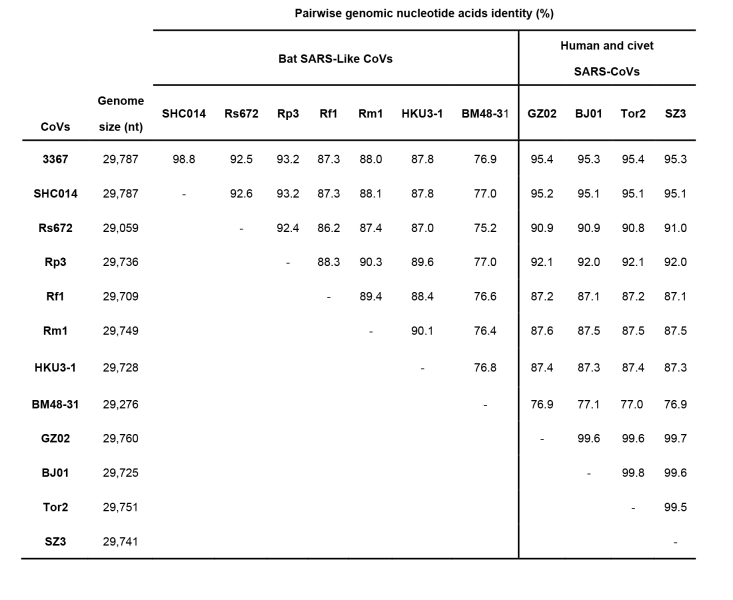

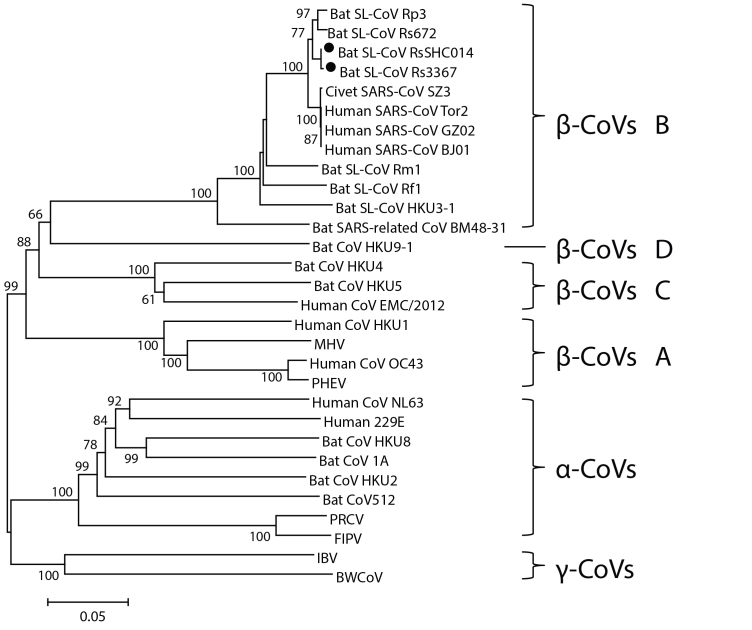

Twenty-seven of the 117 samples (23%) were classed as positive by PCR and subsequently confirmed by sequencing. The species origin of all positive samples was confirmed to be R. sinicus by cytochrome b sequence analysis, as described previously16. A higher prevalence was observed in samples collected in October (30% in 2011 and 48.7% in 2012) than those in April (7.1% in 2011) or May (7.4% in 2012) (Extended Data Table 1). Analysis of the S protein RBD sequences indicated the presence of seven different strains of SL-CoVs (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Figs 1 and 2). In addition to RBD sequences, which closely matched previously described SL-CoVs (Rs672, Rf1 and HKU3)5,8,17,18, two novel strains (designated SL-CoV RsSHC014 and Rs3367) were discovered. Their full-length genome sequences were determined, and both were found to be 29,787 base pairs in size (excluding the poly(A) tail). The overall nucleotide sequence identity of these two genomes with human SARS-CoV (Tor2 strain) is 95%, higher than that observed previously for bat SL-CoVs in China (88–92%)5,8,17,18 or Europe (76%)6 (Extended Data Table 2 and Extended Data Figs 3 and 4). Higher sequence identities were observed at the protein level between these new SL-CoVs and SARS-CoVs (Extended Data Tables 3 and 4). To understand the evolutionary origin of these two novel SL-CoV strains, we conducted recombination analysis with the Recombination Detection Program 4.0 package19 using available genome sequences of bat SL-CoV strains (Rf1, Rp3, Rs672, Rm1, HKU3 and BM48-31) and human and civet representative SARS-CoV strains (BJ01, SZ3, Tor2 and GZ02). Three breakpoints were detected with strong P values (<10−20) and supported by similarity plot and bootscan analysis (Extended Data Fig. 5a, b). Breakpoints were located at nucleotides 20,827, 26,553 and 28,685 in the Rs3367 (and RsSHC014) genome, and generated recombination fragments covering nucleotides 20,827–26,533 (5,727 nucleotides) (including partial open reading frame (ORF) 1b, full-length S, ORF3, E and partial M gene) and nucleotides 26,534–28,685 (2,133 nucleotides) (including partial ORF M, full-length ORF6, ORF7, ORF8 and partial N gene). Phylogenetic analysis using the major and minor parental regions suggested that Rs3367, or RsSHC014, is the descendent of a recombination of lineages that ultimately lead to SARS-CoV and SL-CoV Rs672 (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree based on amino acid sequences of the S RBD region and the two parental regions of bat SL-CoV Rs3367 or RsSHC014.

a, SARS-CoV S protein amino acid residues 310–520 were aligned with homologous regions of bat SL-CoVs using the ClustalW software. A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed using a Poisson model with bootstrap values determined by 1,000 replicates in the MEGA5 software package. The RBD sequences identified in this study are in bold and named by the sample numbers. The key amino acid residues involved in interacting with the human ACE2 molecule are indicated on the right of the tree. SARS-CoV GZ02, BJ01 and Tor2 were isolated from patients in the early, middle and late phase, respectively, of the SARS outbreak in 2003. SARS-CoV SZ3 was identified from Paguma larvata in 2003 collected in Guangdong, China. SL-CoV Rp3, Rs672 and HKU3-1 were identified from R. sinicus collected in China (respectively: Guangxi, 2004; Guizhou, 2006; Hong Kong, 2005). Rf1 and Rm1 were identified from R. ferrumequinum and R. macrotis, respectively, collected in Hubei, China, in 2004. Bat SARS-related CoV BM48-31 was identified from R. blasii collected in Bulgaria in 2008. Bat CoV HKU9-1 was identified from Rousettus leschenaultii collected in Guangdong, China in 2005/2006 and used as an outgroup. All sequences in bold and italics were identified in the current study. Filled triangles, circles and diamonds indicate samples with co-infection by two different SL-CoVs. ‘–’ indicates the amino acid deletion. b, Phylogenetic origins of the two parental regions of Rs3367 or RsSHC014. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees were constructed from alignments of two fragments covering nucleotides 20,827–26,533 (5,727 nucleotides) and 26,534 –28,685 (2,133 nucleotides) of the Rs3367 genome, respectively. For display purposes, the trees were midpoint rooted. The taxa were annotated according to strain names: SARS-CoV, SARS coronavirus; SARS-like CoV, bat SARS-like coronavirus. The two novel SL-CoVs, Rs3367 and RsSHC014, are in bold and italics.

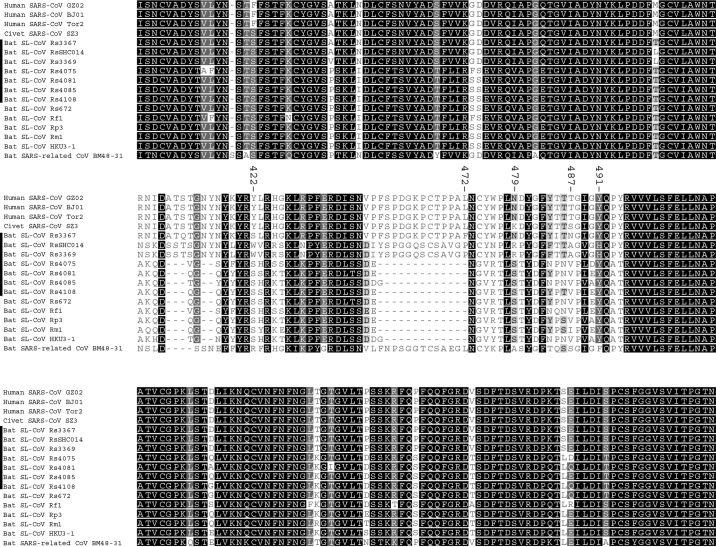

Extended Data Figure 1. Sequence alignment of CoV S protein RBD.

SARS-CoV S protein (amino acids 310–520) is aligned with homologous regions of bat SL-CoVs using ClustalW. The newly discovered bat SL-CoVs are indicated with a bold vertical line on the left. The key amino acid residues involved in the interaction with human ACE2 are numbered on the top of the aligned sequences.

Extended Data Figure 2. Alignment of CoV S protein S1 sequences.

Alignment of S1 sequences (amino acids 1–660) of the two novel bat SL-CoV S proteins with those of previously reported bat SL-CoVs and human and civet SARS-CoVs. The newly discovered bat SL-CoVs are boxed in red. SARS-CoV GZ02, BJ01 and Tor2 were isolated from patients in the early, middle and late phase, respectively, of the SARS outbreak in 2003. SARS-CoV SZ3 was identified from P. larvata in 2003 collected in Guangdong, China. SL-CoV Rp3, Rs 672 and HKU3-1 were identified from R. sinicus collected in Guangxi, Guizhou and Hong Kong, China, respectively. Rf1 and Rm1 were identified from R. ferrumequinum and R. macrotis, respectively, collected in Hubei Province, China. Bat SARS-related CoV BM48-31 was identified from R. blasii collected in Bulgaria.

Extended Data Table 2.

Genomic sequence identities of bat SL-CoVs with SARS-CoVs

Extended Data Figure 3. Complete RdRP sequence phylogeny.

Phylogenetic tree of bat SL-CoVs and SARS-CoVs on the basis of complete RdRP sequences (2,796 nucleotides). Bat SL-CoVs RsSHC014 and Rs3367 are highlighted by filled circles. Three established coronaivirus genera, Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus and Gammacoronavirus are marked as α, β and γ, respectively. Four CoV groups in the genus Betacoronavirus are indicated as A, B, C and D, respectively. MHV, murine hepatitis virus; PHEV, porcine haemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus; PRCV, porcine respiratory coronavirus; FIPV, feline infectious peritonitis virus; IBV, infectious bronchitis coronavirus; BW, beluga whale coronavirus.

Extended Data Figure 4. Sequence phylogeny of the complete S protein of SL-CoVs and SARS-CoV.

Phylogenetic tree of bat SL-CoVs and SARS-CoVs on the basis of complete S protein sequences (1,256 amino acids). Bat SL-CoVs RsSHC014 and Rs3367 are highlighted by filled circles. Bat CoV HKU9 was used as an outgroup.

Extended Data Table 3.

Genomic annotation and comparison of bat SL-CoV Rs3367 with human/civet SARS-CoVs and other bat SL-CoVs

*S1, the N-terminal domain of the coronavirus S protein responsible for receptor binding. S2, the S protein C-terminal domain responsible for menbrane fusion.The ORFs in the genome were predicted and potential protein sequences were translated. The pairwise comparisons were conducted for all ORFs at nucleotide acids (nt) and amino acid (aa) levels. The s2m were compared at nt level. TRS: Transcription regulating-sequences; N/D, not done; N/A, not available.

Extended Data Table 4.

Genomic annotation and comparison of bat SL-CoV RsSHC014 with human/civet SARS-CoVs and other bat SL-CoVs

*S1, the N-terminal domain of the coronavirus S protein responsible for receptor binding. S2, the S protein C-terminal domain responsible for menbrane fusion.The ORFs in the genome were predicted and potential protein sequences were translated. The pairwise comparisons were conducted for all ORFs at nucleotide acids (nt) and amino acid (aa) levels. The s2m were compared at nt level. TRS: Transcription regulating-sequences; N/D, not done; N/A, not available.

Extended Data Figure 5. Detection of potential recombination events.

a, b, Similarity plot (a) and bootscan analysis (b) detected three recombination breakpoints in the bat SL-CoV Rs3367 or SHC014 genome. The three breakpoints were located at the ORF1b (nt 20,827), M (nucleotides 26,553) and N (nucleotides 28,685) genes, respectively. Both analyses were performed with an F84 distance model, a window size of 1,500 base pairs and a step size of 300 base pairs.

The most notable sequence differences between these two new SL-CoVs and previously identified SL-CoVs is in the RBD regions of their S proteins. First, they have higher amino acid sequence identity to SARS-CoV (85% and 96% for RsSHC014 and Rs3367, respectively). Second, there are no deletions and they have perfect sequence alignment with the SARS-CoV RBD region (Extended Data Figs 1 and 2). Structural and mutagenesis studies have previously identified five key residues (amino acids 442, 472, 479, 487 and 491) in the RBD of the SARS-CoV S protein that have a pivotal role in receptor binding20,21. Although all five residues in the RsSHC014 S protein were found to be different from those of SARS-CoV, two of the five residues in the Rs3367 RBD were conserved (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1).

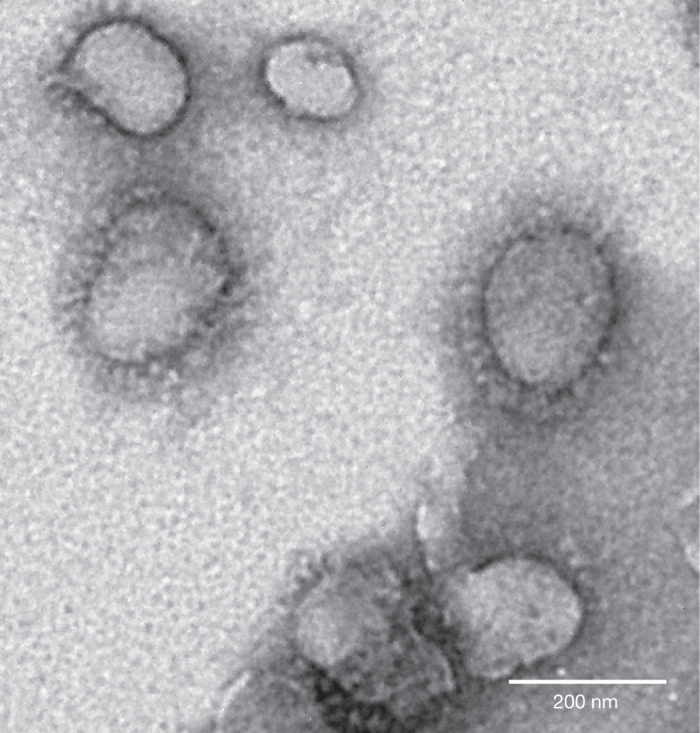

Despite the rapid accumulation of bat CoV sequences in the last decade, there has been no report of successful virus isolation6,22,23. We attempted isolation from SL-CoV PCR-positive samples. Using an optimized protocol and Vero E6 cells, we obtained one isolate which caused cytopathic effect during the second blind passage. Purified virions displayed typical coronavirus morphology under electron microscopy (Fig. 2). Sequence analysis using a sequence-independent amplification method14 to avoid PCR-introduced contamination indicated that the isolate was almost identical to Rs3367, with 99.9% nucleotide genome sequence identity and 100% amino acid sequence identity for the S1 region. The new isolate was named SL-CoV-WIV1.

Figure 2. Electron micrograph of purified virions.

Virions from a 10-ml culture were collected, fixed and concentrated/purified by sucrose gradient centrifugation. The pelleted viral particles were suspended in 100 μl PBS, stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid (pH 7.0) and examined directly using a Tecnai transmission electron microscope (FEI) at 200 kV.

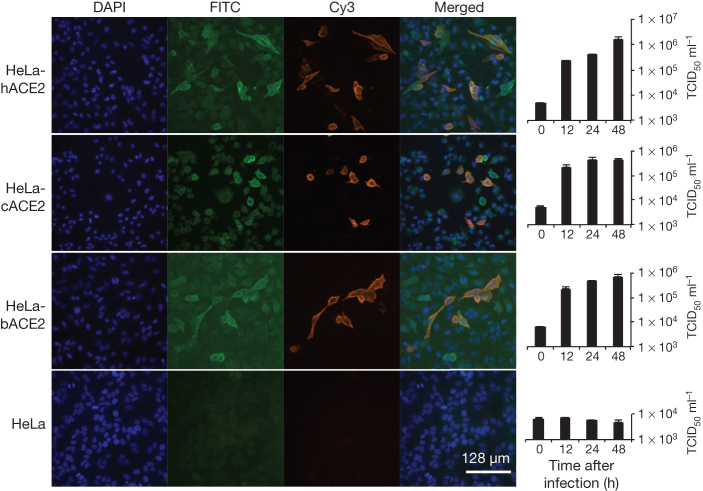

To determine whether WIV1 can use ACE2 as a cellular entry receptor, we conducted virus infectivity studies using HeLa cells expressing or not expressing ACE2 from humans, civets or Chinese horseshoe bats. We found that WIV1 is able to use ACE2 of different origins as an entry receptor and replicated efficiently in the ACE2-expressing cells (Fig. 3). This is, to our knowledge, the first identification of a wild-type bat SL-CoV capable of using ACE2 as an entry receptor.

Figure 3. Analysis of receptor usage of SL-CoV-WIV1 determined by immunofluorescence assay and real-time PCR.

Determination of virus infectivity in HeLa cells with and without the expression of ACE2. b, bat; c, civet; h, human. ACE2 expression was detected with goat anti-humanACE2 antibody followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG. Virus replication was detected with rabbit antibody against the SL-CoV Rp3 nucleocapsid protein followed by cyanine 3 (Cy3)-conjugated mouse anti-rabbit IgG. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). The columns (from left to right) show staining of nuclei (blue), ACE2 expression (green), virus replication (red), merged triple-stained images and real-time PCR results, respectively. (n = 3); error bars represent standard deviation.

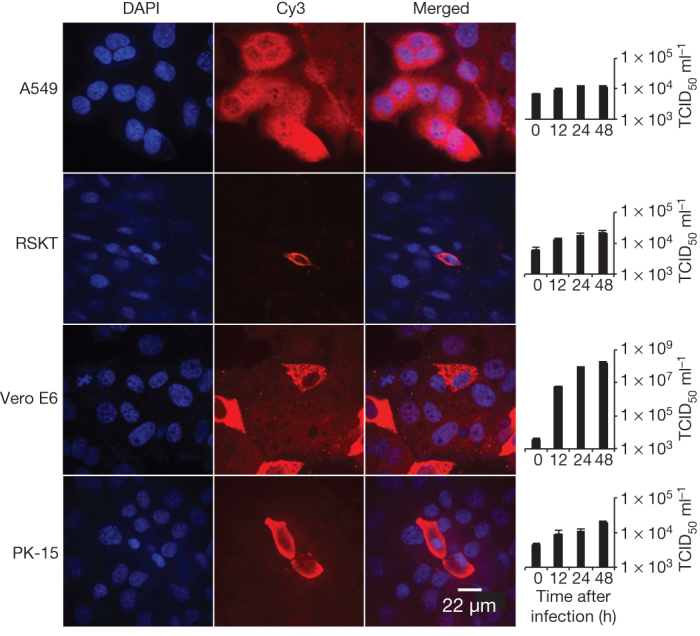

To assess its cross-species transmission potential, we conducted infectivity assays in cell lines from a range of species. Our results (Fig. 4 and Extended Data Table 5) indicate that bat SL-CoV-WIV1 can grow in human alveolar basal epithelial (A549), pig kidney 15 (PK-15) and Rhinolophus sinicus kidney (RSKT) cell lines, but not in human cervix (HeLa), Syrian golden hamster kidney (BHK21), Myotis davidii kidney (BK), Myotis chinensis kidney (MCKT), Rousettus leschenaulti kidney (RLK) or Pteropus alecto kidney (PaKi) cell lines. Real-time RT–PCR indicated that WIV1 replicated much less efficiently in A549, PK-15 and RSKT cells than in Vero E6 cells (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Analysis of host range of SL-CoV-WIV1 determined by immunofluorescence assay and real-time PCR.

Virus infection in A549, RSKT, Vero E6 and PK-15 cells. Virus replication was detected as described for Fig. 3. The columns (from left to right) show staining of nuclei (blue), virus replication (red), merged double-stained images and real-time PCR results, respectively. n = 3; error bars represent s.d.

Extended Data Table 5.

Cell lines used for virus isolation and susceptibility tests

*Infectivity was determined by the presence of viral antigen detected by immunofluorescence assay.

To assess the cross-neutralization activity of human SARS-CoV sera against WIV1, we conducted serum-neutralization assays using nine convalescent sera from SARS patients collected in 2003. The results showed that seven of these were able to completely neutralize 100 tissue culture infectious dose 50 (TCID50) WIV1 at dilutions of 1:10 to 1:40, further confirming the close relationship between WIV1 and SARS-CoV.

Our findings have important implications for public health. First, they provide the clearest evidence yet that SARS-CoV originated in bats. Our previous work provided phylogenetic evidence of this5, but the lack of an isolate or evidence that bat SL-CoVs can naturally infect human cells, until now, had cast doubt on this hypothesis. Second, the lack of capacity of SL-CoVs to use of ACE2 receptors has previously been considered as the key barrier for their direct spillover into humans, supporting the suggestion that civets were intermediate hosts for SARS-CoV adaptation to human transmission during the SARS outbreak24. However, the ability of SL-CoV-WIV1 to use human ACE2 argues against the necessity of this step for SL-CoV-WIV1 and suggests that direct bat-to-human infection is a plausible scenario for some bat SL-CoVs. This has implications for public health control measures in the face of potential spillover of a diverse and growing pool of recently discovered SARS-like CoVs with a wide geographic distribution.

Our findings suggest that the diversity of bat CoVs is substantially higher than that previously reported. In this study we were able to demonstrate the circulation of at least seven different strains of SL-CoVs within a single colony of R. sinicus during a 12-month period. The high genetic diversity of SL-CoVs within this colony was mirrored by high phenotypic diversity in the differential use of ACE2 by different strains. It would therefore not be surprising if further surveillance reveals a broad diversity of bat SL-CoVs that are able to use ACE2, some of which may have even closer homology to SARS-CoV than SL-CoV-WIV1. Our results—in addition to the recent demonstration of MERS-CoV in a Saudi Arabian bat25, and of bat CoVs closely related to MERS-CoV in China, Africa, Europe and North America3,26,27—suggest that bat coronaviruses remain a substantial global threat to public health.

Finally, this study demonstrates the public health importance of pathogen discovery programs targeting wildlife that aim to identify the ‘known unknowns’—previously unknown viral strains closely related to known pathogens. These programs, focused on specific high-risk wildlife groups and hotspots of disease emergence, may be a critical part of future global strategies to predict, prepare for, and prevent pandemic emergence28.

Methods Summary

Throat and faecal swabs or fresh faecal samples were collected in viral transport medium as described previously14. All PCR was conducted with the One-Step RT–PCR kit (Invitrogen). Primers targeting the highly conserved regions of the RdRP gene were used for detection of all alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses as described previously15. Degenerate primers were designed on the basis of all available genomic sequences of SARS-CoVs and SL-CoVs and used for amplification of the RBD sequences of S genes or full-length genomic sequences. Degenerate primers were used for amplification of the bat ACE2 gene as described previously29. PCR products were gel purified and cloned into pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega). At least four independent clones were sequenced to obtain a consensus sequence. PCR-positive faecal samples (in 200 μl buffer) were gradient centrifuged at 3,000–12,000g and supernatant diluted at 1:10 in DMEM before being added to Vero E6 cells. After incubation at 37 °C for 1 h, inocula were removed and replaced with fresh DMEM with 2% FCS. Cells were incubated at 37 °C and checked daily for cytopathic effect. Cell lines from different origins were grown on coverslips in 24-well plates and inoculated with the novel SL-CoV at a multiplicity of infection of 10. Virus replication was detected at 24 h after infection using rabbit antibodies against the SL-CoV Rp3 nucleocapsid protein followed by Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG.

Online Methods

Sampling

Bats were trapped in their natural habitat as described previously5. Throat and faecal swab samples were collected in viral transport medium (VTM) composed of Hank’s balanced salt solution, pH 7.4, containing BSA (1%), amphotericin (15 μg ml−1), penicillin G (100 U ml−1) and streptomycin (50 μg ml−1). To collect fresh faecal samples, clean plastic sheets measuring 2.0 by 2.0 m were placed under known bat roosting sites at about 18:00 h each evening. Relatively fresh faecal samples were collected from sheets at approximately 05:30–06:00 the next morning and placed in VTM. Samples were transported to the laboratory and stored at −80 °C until use. All animals trapped for this study were released back to their habitat after sample collection. All sampling processes were performed by veterinarians with approval from Animal Ethics Committee of the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIVH05210201) and EcoHealth Alliance under an inter-institutional agreement with University of California, Davis (UC Davis protocol no. 16048).

RNA extraction, PCR and sequencing

RNA was extracted from 140 μl of swab or faecal samples with a Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was eluted in 60 μl RNAse-free buffer (buffer AVE, Qiagen), then aliquoted and stored at −80 °C. One-step RT–PCR (Invitrogen) was used to detect coronavirus sequences as described previously15. First round PCR was conducted in a 25-μl reaction mix containing 12.5 μl PCR 2× reaction mix buffer, 10 pmol of each primer, 2.5 mM MgSO4, 20 U RNase inhibitor, 1 μl SuperScript III/ Platinum Taq Enzyme Mix and 5 μl RNA. Amplification of the RdRP-gene fragment was performed as follows: 50 °C for 30 min, 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles consisting of 94 °C for 15 s, 62 °C for 15 s, 68 °C for 40 s, and a final extension of 68 °C for 5 min. Second round PCR was conducted in a 25-μl reaction mix containing 2.5 μl PCR reaction buffer, 5 pmol of each primer, 50 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dNTP, 0.1 μl Platinum Taq Enzyme (Invitrogen) and 1 μl first round PCR product. The amplification of RdRP-gene fragment was performed as follows: 94 °C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles consisting of 94 °C for 30 s, 52 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 40 s, and a final extension of 72 °C for 5 min.

To amplify the RBD region, one-step RT–PCR was performed with primers designed based on available SARS-CoV or bat SL-CoVs (first round PCR primers; F, forward; R, reverse: CoVS931F-5′-VWGADGTTGTKAGRTTYCCT-3′ and CoVS1909R-5′-TAARACAVCCWGCYTGWGT-3′; second PCR primers: CoVS951F-5′-TGTKAGRTTYCCTAAYATTAC-3′ and CoVS1805R-5′-ACATCYTGATANARAACAGC-3′). First-round PCR was conducted in a 25-μl reaction mix as described above except primers specific for the S gene were used. The amplification of the RBD region of the S gene was performed as follows: 50 °C for 30 min, 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles consisting of 94 °C for 15 s, 43 °C for 15 s, 68 °C for 90 s, and a final extension of 68 °C for 5 min. Second-round PCR was conducted in a 25-μl reaction mix containing 2.5 μl PCR reaction buffer, 5 pmol of each primer, 50 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dNTP, 0.1 μl Platinum Taq Enzyme (Invitrogen) and 1 μl first round PCR product. Amplification was performed as follows: 94 °C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles consisting of 94 °C for 30 s, 41 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 60 s, and a final extension of 72 °C for 5 min.

PCR products were gel purified and cloned into pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega). At least four independent clones were sequenced to obtain a consensus sequence for each of the amplified regions.

Sequencing full-length genomes

Degenerate coronavirus primers were designed based on all available SARS-CoV and bat SL-CoV sequences in GenBank and specific primers were designed from genome sequences generated from previous rounds of sequencing in this study (primer sequences will be provided upon request). All PCRs were conducted using the One-Step RT–PCR kit (Invitrogen). The 5′ and 3′ genomic ends were determined using the 5′ or 3′ RACE kit (Roche), respectively. PCR products were gel purified and sequenced directly or following cloning into pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega). At least four independent clones were sequenced to obtain a consensus sequence for each of the amplified regions and each region was sequenced at least twice.

Sequence analysis and databank accession numbers

Routine sequence management and analysis was carried out using DNAStar or Geneious. Sequence alignment and editing was conducted using ClustalW, BioEdit or GeneDoc. Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic trees based on the protein sequences were constructed using a Poisson model with bootstrap values determined by 1,000 replicates in the MEGA5 software package.

Sequences obtained in this study have been deposited in GenBank as follows (accession numbers given in parenthesis): full-length genome sequence of SL-CoV RsSHC014 and Rs3367 (KC881005, KC881006); full-length sequence of WIV1 S (KC881007); RBD (KC880984-KC881003); ACE2 (KC8810040). SARS-CoV sequences used in this study: human SARS-CoV strains Tor2 (AY274119), BJ01 (AY278488), GZ02 (AY390556) and civet SARS-CoV strain SZ3 (AY304486). Bat coronavirus sequences used in this study: Rs672 (FJ588686), Rp3 (DQ071615), Rf1 (DQ412042), Rm1 (DQ412043), HKU3-1 (DQ022305), BM48-31 (NC_014470), HKU9-1 (NC_009021), HKU4 (NC_009019), HKU5 (NC_009020), HKU8 (DQ249228), HKU2 (EF203067), BtCoV512 (NC_009657), 1A (NC_010437). Other coronavirus sequences used in this study: HCoV-229E (AF304460), HCoV-OC43 (AY391777), HCoV-NL63 (AY567487), HKU1 (NC_006577), EMC (JX869059), FIPV (NC_002306), PRCV (DQ811787), BWCoV (NC_010646), MHV (AY700211), IBV (AY851295).

Amplification, cloning and expression of the bat ACE2 gene

Construction of expression clones for human and civet ACE2 in pcDNA3.1 has been described previously29. Bat ACE2 was amplified from a R. sinicus (sample no. 3357). In brief, total RNA was extracted from bat rectal tissue using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). First-strand complementary DNA was synthesized from total RNA by reverse transcription with random hexamers. Full-length bat ACE2 fragments were amplified using forward primer bAF2 and reverse primer bAR2 (ref. 29). The ACE2 gene was cloned into pCDNA3.1 with KpnI and XhoI, and verified by sequencing. Purified ACE2 plasmids were transfected to HeLa cells. After 24 h, lysates of HeLa cells expressing human, civet, or bat ACE2 were confirmed by western blot or immunofluorescence assay.

Western blot analysis

Lysates of cells or filtered supernatants containing pseudoviruses were separated by SDS–PAGE, followed by transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore). For detection of S protein, the membrane was incubated with rabbit anti-Rp3 S fragment (amino acids 561–666) polyantibodies (1:200), and the bound antibodies were detected by alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000). For detection of HIV-1 p24 in supernatants, monoclonal antibody against HIV p24 (p24 MAb) was used as the primary antibody at a dilution of 1:1,000, followed by incubation with AP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG at the same dilution. To detect the expression of ACE2 in HeLa cells, goat antibody against the human ACE2 ectodomain (1:500) was used as the first antibody, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (1:1,000).

Virus isolation

Vero E6 cell monolayers were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS. PCR-positive samples (in 200 μl buffer) were gradient centrifuged at 3,000–12,000g, and supernatant were diluted 1:10 in DMEM before being added to Vero E6 cells. After incubation at 37 °C for 1 h, inocula were removed and replaced with fresh DMEM with 2% FCS. Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 3 days and checked daily for cytopathic effect. Double-dose triple antibiotics penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin (Gibco) were included in all tissue culture media (penicillin 200 IU ml−1, streptomycin 0.2 mg ml−1, amphotericin 0.5 μg ml−1). Three blind passages were carried out for each sample. After each passage, both the culture supernatant and cell pellet were examined for presence of virus by RT–PCR using primers targeting the RdRP or S gene. Virions in supernatant (10 ml) were collected and fixed using 0.1% formaldehyde for 4 h, then concentrated by ultracentrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion (5 ml) at 80,000g for 90 min using a Ty90 rotor (Beckman). The pelleted viral particles were suspended in 100 μl PBS, stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid (pH 7.0) and examined using a Tecnai transmission electron microscope (FEI) at 200 kV.

Virus infectivity detected by immunofluorescence assay

Cell lines used for this study and their culture conditions are summarized in Extended Data Table 5. Virus titre was determined in Vero E6 cells by cytopathic effect (CPE) counts. Cell lines from different origins and HeLa cells expressing ACE2 from human, civet or Chinese horseshoe bat were grown on coverslips in 24-well plates (Corning) incubated with bat SL-CoV-WIV1 at a multiplicity of infection = 10 for 1 h. The inoculum was removed and washed twice with PBS and supplemented with medium. HeLa cells without ACE2 expression and Vero E6 cells were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. At 24 h after infection, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 20 min at 4 °C. ACE2 expression was detected using goat anti-human ACE2 immunoglobulin (R&D Systems) followed by FITC-labelled donkey anti-goat immunoglobulin (PTGLab). Virus replication was detected using rabbit antibody against the SL-CoV Rp3 nucleocapsid protein followed by Cy3-conjugated mouse anti-rabbit IgG. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Staining patterns were examined using a FV1200 confocal microscope (Olympus).

Virus infectivity detected by real-time RT–PCR

Vero E6, A549, PK15, RSKT and HeLa cells with or without expression of ACE2 of different origins were inoculated with 0.1 TCID50 WIV-1 and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. After removing the inoculum, the cells were cultured with medium containing 1% FBS. Supernatants were collected at 0, 12, 24 and 48 h. RNA from 140 μl of each supernatant was extracted with the Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) following manufacturer’s instructions and eluted in 60 μl buffer AVE (Qiagen). RNA was quantified on the ABI StepOne system, with the TaqMan AgPath-ID One-Step RT–PCR Kit (Applied Biosystems) in a 25 μl reaction mix containing 4 μl RNA, 1 × RT–PCR enzyme mix, 1 × RT–PCR buffer, 40 pmol forward primer (5′-GTGGTGGTGACGGCAAAATG-3′), 40 pmol reverse primer (5′-AAGTGAAGCTTCTGGGCCAG-3′) and 12 pmol probe (5′-FAM-AAAGAGCTCAGCCCCAGATG-BHQ1-3′). Amplification parameters were 10 min at 50 °C, 10 min at 95 °C and 50 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 20 s at 60 °C. RNA dilutions from purified WIV-1 stock were used as a standard.

Serum neutralization test

SARS patient sera were inactivated at 56 °C for 30 min and then used for virus neutralization testing. Sera were diluted starting with 1:10 and then serially twofold diluted in 96-well cell plates to 1:40. Each 100 μl serum dilution was mixed with 100 μl viral supernatant containing 100 TCID50of WIV1 and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The mixture was added in triplicate wells of 96-well cell plates with plated monolayers of Vero E6 cells and further incubated at 37 °C for 2 days. Serum from a healthy blood donor was used as a negative control in each experiment. CPE was observed using an inverted microscope 2 days after inoculation. The neutralizing antibody titre was read as the highest dilution of serum which completely suppressed CPE in infected wells. The neutralization test was repeated twice.

Recombination analysis

Full-length genomic sequences of SL-CoV Rs3367 or RsSHC014 were aligned with those of selected SARS-CoVs and bat SL-CoVs using Clustal X. The aligned sequences were preliminarily scanned for recombination events using Recombination Detection Program (RDP) 4.0 (ref. 19). The potential recombination events suggested by RDP owing to their strong P values (<10–20) were investigated further by similarity plot and bootscan analyses implemented in Simplot 3.5.1. Phylogenetic origin of the major and minor parental regions of Rs3367 or RsSHC014 were constructed from the concatenated sequences of the essential ORFs of the major and minor parental regions of selected SARS-CoV and SL-CoVs. Two genome regions between three estimated breakpoints (20,827–26,553 and 26,554–28,685) were aligned independently using ClustalX and generated two alignments of 5,727 base pairs and 2,133 base pairs. The two alignments were used to construct maximum likelihood trees to better infer the fragment parents. All nucleotide numberings in this study are based on Rs3367 genome position.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the State Key Program for Basic Research (2011CB504701 and 2010CB530100), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81290341 and 31321001), Scientific and technological basis special project (2013FY113500), CSIRO OCE Science Leaders Award, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) award number R01AI079231, a National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Science Foundation (NSF) ‘Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases’ award from the NIH Fogarty International Center (R01TW005869), an award from the NIH Fogarty International Center supported by International Influenza Funds from the Office of the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (R56TW009502), and United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Emerging Pandemic Threats PREDICT. The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NIAID, NIH, NSF, USAID or the United States Government. We thank X. Che from Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University, for providing human SARS patient sera.

Extended data figures and tables

PowerPoint slides

Author Contributions

Z.-L.S. and P.D. designed and coordinated the study. X.-Y.G., J.-L. L. and X.-L.Y. conducted majority of experiments and contributed equally to the study. A.A.C., B.H., W.Z., C.P., Y.-J.Z., C.-M.L., B.T., N.W. and Y.Z. conducted parts of the experiments and analyses. J.H.E., J.K.M. and S.-Y.Z. coordinated the field study. X.-Y.G., J.-L.L., X.-L.Y., B.T. and G.-J.Z. collected the samples. G.C. and L.-F.W. designed and supervised part of the experiments. All authors contributed to the interpretations and conclusions presented. Z.-L.S. and X-Y.G. wrote the manuscript with significant contributions from P.D. and L-F.W. and input from all authors.

Accession codes

Accessions

GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ

Data deposits

Sequences of three bat SL-CoV genomes, bat SL-CoV RBD and R. sinicus ACE2 genes have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KC881005–KC881007 (genomes from SL-CoV RsSHC014, Rs3367 and W1V1, respectively), KC880984–KC881003 (bat SL-CoV RBD genes) and KC881004 (R. sinicus ACE2), respectively.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Xing-Yi Ge, Jia-Lu Li and Xing-Lou Yang: These authors contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Peter Daszak, Email: daszak@ecohealthalliance.org.

Zheng-Li Shi, Email: zlshi@wh.iov.cn.

References

- 1.Ksiazek TG, et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anthony SJ, et al. Coronaviruses in bats from Mexico. J. Gen. Virol. 2013;94:1028–1038. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.049759-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raj VS, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature. 2013;495:251–254. doi: 10.1038/nature12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li W, et al. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science. 2005;310:676–679. doi: 10.1126/science.1118391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drexler JF, et al. Genomic characterization of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus in European bats and classification of coronaviruses based on partial RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene sequences. J. Virol. 2010;84:11336–11349. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00650-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tong S, et al. Detection of novel SARS-like and other coronaviruses in bats from Kenya. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009;15:482–485. doi: 10.3201/eid1503.081013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau SKP, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:14040–14045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506735102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ren W, et al. Difference in receptor usage between severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus and SARS-like coronavirus of bat origin. J. Virol. 2008;82:1899–1907. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01085-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hon CC, et al. Evidence of the recombinant origin of a bat severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-like coronavirus and its implications on the direct ancestor of SARS coronavirus. J. Virol. 2008;82:1819–1826. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01926-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li W, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong SK, Li W, Moore MJ, Choe H, Farzan M. A 193-amino acid fragment of the SARS coronavirus S protein efficiently binds angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:3197–3201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300520200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker MM, et al. Synthetic recombinant bat SARS-like coronavirus is infectious in cultured cells and in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:19944–19949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808116105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, et al. Host range, prevalence, and genetic diversity of adenoviruses in bats. J. Virol. 2010;84:3889–3897. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02497-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Souza Luna LK, et al. Generic detection of coronaviruses and differentiation at the prototype strain level by reverse transcription-PCR and nonfluorescent low-density microarray. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:1049–1052. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02426-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui J, et al. Evolutionary relationships between bat coronaviruses and their hosts. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007;13:1526–1532. doi: 10.3201/eid1310.070448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan J, et al. Intraspecies diversity of SARS-like coronaviruses in Rhinolophus sinicus and its implications for the origin of SARS coronaviruses in humans. J. Gen. Virol. 2010;91:1058–1062. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.016378-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ren W, et al. Full-length genome sequences of two SARS-like coronaviruses in horseshoe bats and genetic variation analysis. J. Gen. Virol. 2006;87:3355–3359. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin DP, et al. RDP3: a flexible and fast computer program for analyzing recombination. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2462–2463. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu K, Peng G, Wilken M, Geraghty RJ, Li F. Mechanisms of host receptor adaptation by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:8904–8911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.325803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li W, et al. Receptor and viral determinants of SARS-coronavirus adaptation to human ACE2. EMBO J. 2005;24:1634–1643. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lau SK, et al. Ecoepidemiology and complete genome comparison of different strains of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related Rhinolophus bat coronavirus in China reveal bats as a reservoir for acute, self-limiting infection that allows recombination events. J. Virol. 2010;84:2808–2819. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02219-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lau SK, et al. Coexistence of different genotypes in the same bat and serological characterization of Rousettus bat coronavirus HKU9 belonging to a novel Betacoronavirus subgroup. J. Virol. 2010;84:11385–11394. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01121-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 24.Song HD, et al. Cross-host evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in palm civet and human. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:2430–2435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409608102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Memish ZA, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in bats, Saudi Arabia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:11. doi: 10.3201/eid1911.131172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan JF, et al. Is the discovery of the novel human betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012 (HCoV-EMC) the beginning of another SARS-like pandemic? J. Infect. 2012;65:477–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ithete NL, et al. Close relative of human Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in bat, South Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:1697–1699. doi: 10.3201/eid1910.130946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morse SS, et al. Prediction and prevention of the next pandemic zoonosis. Lancet. 2012;380:1956–1965. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61684-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hou Y, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) proteins of different bat species confer variable susceptibility to SARS-CoV entry. Arch. Virol. 2010;155:1563–1569. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0729-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Accessions

GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ

Data deposits

Sequences of three bat SL-CoV genomes, bat SL-CoV RBD and R. sinicus ACE2 genes have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KC881005–KC881007 (genomes from SL-CoV RsSHC014, Rs3367 and W1V1, respectively), KC880984–KC881003 (bat SL-CoV RBD genes) and KC881004 (R. sinicus ACE2), respectively.