Abstract

Purpose

To demonstrate the versatility and performance of a compact Bayer filter snapshot hyperspectral fundus camera for in-vivo clinical applications including retinal oximetry and macular pigment optical density measurements.

Methods

12 healthy volunteers were recruited under an Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved protocol. Fundus images were taken with a custom hyperspectral camera with a spectral range of 460–630 nm. We determined retinal vascular oxygen saturation (sO2) for the healthy population using the captured spectra by least squares curve fitting. Additionally, macular pigment optical density was localized and visualized using multispectral reflectometry from selected wavelengths.

Results

We successfully determined the mean sO2 of arteries and veins of each subject (ages 21–80) with excellent intrasubject repeatability (1.4% standard deviation). The mean arterial sO2 for all subjects was 90.9% ± 2.5%, whereas the mean venous sO2 for all subjects was 64.5% ± 3.5%. The mean artery–vein (A–V) difference in sO2 varied between 20.5% and 31.9%. In addition, we were able to reveal and quantify macular pigment optical density.

Conclusions

We demonstrated a single imaging tool capable of oxygen saturation and macular pigment density measurements in vivo. The unique combination of broad spectral range, high spectral–spatial resolution, rapid and robust imaging capability, and compact design make this system a valuable tool for multifunction spectral imaging that can be easily performed in a clinic setting.

Keywords: Hyperspectral fundus imaging, oximetry, macular pigment, spectroscopy

Introduction

Hyperspectral retinal imaging is a novel technique that can capture spatially resolved spectral information from the retina noninvasively. Conventional fundus imaging detects either monochromatic light or red, green, and blue (RGB) color channels that are reflected by retinal structures, providing great spatial details, but limited spectral information, of the retina.1,2 Hyperspectral imaging adds the ability to quantify the spectral composition of the light reflected by the retina. As different structures and chemicals have unique spectral reflectance properties, hyperspectral imaging provides another dimension of information for researchers studying metabolism and chemical structure in human tissue.3

Spectral measurements of retinal vessel oxygenation allow for the study of tissue perfusion and metabolic demands of healthy retina, as well as changes that occur in diabetes and diabetic retinopathy.4–8 Several popular commercial oximetry devices such as Oxymap and Imedos are based on a two-wavelength method for computing retinal vessel oxygenation.9,10 Newer hyperspectral systems have the ability to use the entire absorbance spectra of hemoglobin in determining the oxygen saturation,11,12 a method which reduces the influence of vessel thickness and backscatter from whole blood cells.13–15

Similarly, retinal reflectance spectra can be used to study molecules (hemoglobin, macular pigment, melanin) and cell types within the retina.16–18 These analyses have clinical utility in studying diseases of the retina such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD),19 where loss of macular pigment and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells are characteristic features. For example, the study of macular pigment optical density (MPOD) has helped researchers understand the protective role of macular pigment in AMD.20,21 Hyperspectral retinal reflectometry has greatly simplified the study of MPOD compared to prior methods.22

Hyperspectral imaging in ophthalmology has evolved from coarsely adapted industrial prototypes with lengthy imaging time to specially designed snapshot systems that have improved potential for clinical applications. Early hyperspectral systems collected spectral information in an image by scanning either the wavelength (λ) or spatial dimension (x,y) in the image plane.11,23 These scanning-type systems required seconds to minutes to acquire a complete dataset and relied on complicated image rectification when imaging a rapidly moving object, like the eye.12 More modern hyperspectral systems have combined high-resolution detectors with sophisticated optics to allow for simultaneous imaging at multiple wavelengths. Without lag or scanning time, snapshot systems collect an information-dense hyperspectral data cube in a single image.24 Unfortunately, these existing systems are often bulky, require precision alignment, and/or specialty optics, such as prisms,24 multiple aperatures,25 or gratings,17 which make them difficult to install, align, and operate in a clinic setting.

Herein we describe a snapshot hyperspectral imaging system that is compact and versatile and allows for quick, noninvasive spectral study of the retina without moving parts for spectral or spatial scanning, imaging lag, or complicated optical components. We realized 16 wavelength channels from 460 to 630 nm and 256 × 512 pixels of resolution using a mosaic layout of mono-lithographically fabricated Fabry–Perot filters atop a complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) detector array (CMV2000, CMOSIS, Imec, Belgium). This novel design does not require any additional optical image splitting or complicated filters.17,24,26 It can capture hyperspectral images with the ease and flexibility of a normal CMOS camera, allowing for simple integration to standard fundus cameras such as those commonly found in ophthalmology clinics.27

In this work, we demonstrate the versatile and robust data collection capabilities of this compact snapshot hyperspectral camera in clinical ophthalmology applications including spectra-based retinal oximetry measurements and MPOD measurements. These analyses provide the proof-of-principle of the performance of the system and allow us to study the strengths and limitations of this tool.

Methods

System

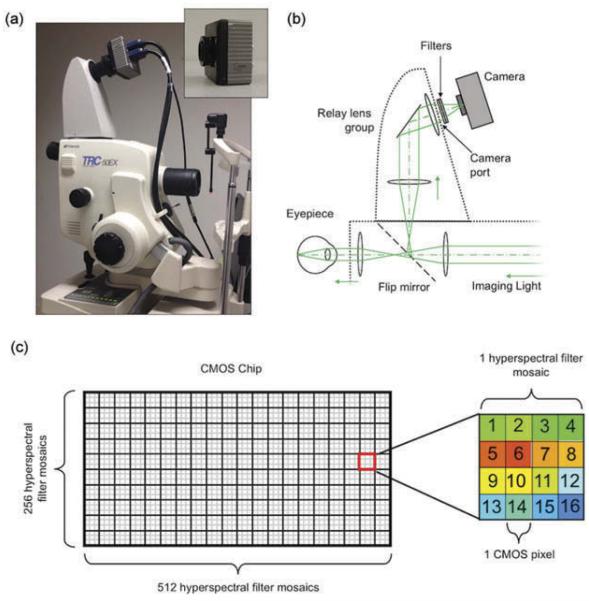

The hyperspectral fundus camera system is shown in Figure 1. We installed the hyperspectral detector onto the camera port of a commercial fundus camera (Topcon TRC-50EX). The hyperspectral imaging detector (inset in Figure 1a) is a prototype. It consists of a Bayer filter mosaic pattern of 16 different Fabry–Perot narrow-band spectral filters, with transmission bandwidths of 10–15 nm, ranging from 460 to 630 nm, manufactured mono-lithographically onto a CMOS imaging sensor (1024 × 2048 CMOS pixels, CMOSIS CMV2000, Imec, Belgium). The filters are arranged in a 4 × 4 mosaic pattern, with each filter covering a single CMOS pixel. The mosaic pattern of filters is repeated across the CMOS sensor, resulting in an effective spatial resolution of 256 × 512 hyperspectral pixels consisting of 16 wavelength bands as shown in Figure 1c. The detector chip is housed in an Adimec quartz series camera body (Q-2A340, Adimec, The Netherlands) measuring 80 mm2 and weighing 400 g. The optical schematic is shown in Figure 1b. For clarity, we only show the path of light reflected from retina. The detector was installed on a commercial fundus camera via an off-the-shelf relay lens system (C-mount, TL-209 relay lens, Topcon, Japan). To prevent second-order transmission of Fabry–Perot filters outside the spectral range of the detector, a band-pass filter set (long-pass filter: OD4-450 nm, EdmundOptics, band-pass filter BG-38 VIS, EdmundOptics) was installed in the lens mount of the camera to pass light between 460 and 630 nm. The spectral response of each channel can be found in our previous report.27 More detailed information regarding this hyperspectral imaging detector can be found at Imec’s website.28

Figure 1.

Clinical imaging system. (a) The compact Imec snapshot hyperspectral detector (inset) is integrated with a commercial fundus camera. (b) Optical schematic of detector and relay lens system. (c) Diagram of the detector with the filter mosaics. Each filter mosaic is a 4 × 4 array of filters printed on a 4 × 4 area of pixels.

The camera was connected to a computer via the Camera Link data port. The electronic shutter was controlled by software provided by Imec, and the raw data was processed off-line with Matlab software (The Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA, USA).

Subjects

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects. Each participant signed an informed consent form prior to inclusion.

We recruited 12 volunteers without known ocular disease for fundus imaging with the snapshot hypersectional system. Volunteers were included regardless of refractive errors. The mean age of the group was 44.9 ± 20.7, range 21–80 with 7 males and 5 females. Volunteers underwent pupil dilation with a combination of tropicamide 1% and phenylephrine hydrochloride 2.5% eye drops. For each subject, images were taken of the optic disc at 20° field of view (FOV) for oxygen saturation measurements and of the macula at 35° FOV for MPOD mapping.

Retinal oximetry

From the collected hyperspectral fundus images, the vessels were manually segmented, and the vessel oxygen saturation (sO2) was measured using a multi-wavelength curve fitting analysis. The method was described in our previous reports.27 We first calculated the optical density (OD) spectra of blood vessels by

| (1) |

where Iin is the spectrum of a vessel extracted from the hyperspectral cube and Iout is the spectrum from the area adjacent to the vessel. We then used least squares method to fit the OD to the equation,

| (2) |

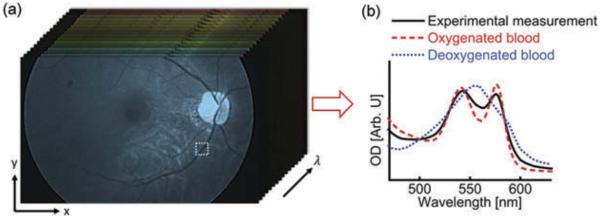

where B and N represent wavelength-independent and wavelength-dependent optical scattering, respectively; λ is the optical wavelength; A is the coefficient related to the experimental geometry and vessel diameter; μHbR(λ) and μHbO2(λ) are the effective attenuation coefficients of the fully deoxygenated and oxygenated blood, respectively. To increase the accuracy of the calculation, we convolved the oxygenated/deoxygenated whole blood spectra with the spectral response of the camera in the fitting. This method is visually represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Example vessel selection and analysis. Vessels near the optic disc are selected, and their spectra are analyzed to determine the content of oxygenation and deoxygenated blood, after convolving the measured spectra with the spectral response of the camera.

The retinal oximetry measurements were validated experimentally with bovine blood specimens. The specimens were exposed to either room air, or 100% nitrogen to simulate oxygenated and deoxygenated blood. The specimens were then placed in 150 μm deep chambers made of glass slides and coverslips and imaged with the hyperspectral camera. For validation, the same slides were imaged with a well-calibrated spectrometer (Shamrock 303i, Andor. 150 line grating, 0.88 nm spectral resolution). Using Equation 2 we determined the sO2 of the blood specimens. The sO2 of oxygenated and deoxygenated specimens were 0.97 and 0.68, respectively, as measured with the spectrometer. The measurements made with the hyperspectral camera varied by less than 3% (0.99 and 0.68 for oxygenated and deoxygenated blood, respectively).

Macular pigment optic density

We calculated MPOD as

| (3) |

where DMP(465) is the macular pigment OD with 465 nm wavelength; KMP(465) and KMP(547) are optical extinction coefficients with 465 and 547 nm, respectively; RF and RP are light reflectance at fovea and perifovea, respectively.16

Retinal reflectance maps were extracted from the corresponding channels in the hyperspectral image datacube. We chose the 95 percentile of MPOD as the maximum value, and normalized the MPOD to that maximum value. The purpose of this normalization is to provide a fair comparison between each subject and minimize the estimation bias from the calculation method.

In order to better visualize the location of macular pigment, we overlaid MPOD maps with vessel maps extracted from hyperspectral image datacube. The vessel maps were generated by comparing the optical densities between 562 and 509 nm:

| (4) |

where DV is the relative OD difference between 562 and 509 nm; R(509) and R(562) are the reflectance extracted from the corresponding channels in the hyperspectral image datacube. These channels were specifically chosen because they highlight blood, which shows a large difference in OD at these wavelengths, while the retinal tissue does not. The vessel contrast was further enhanced using Hessian-based Frangi filter for better visualization.29

Results

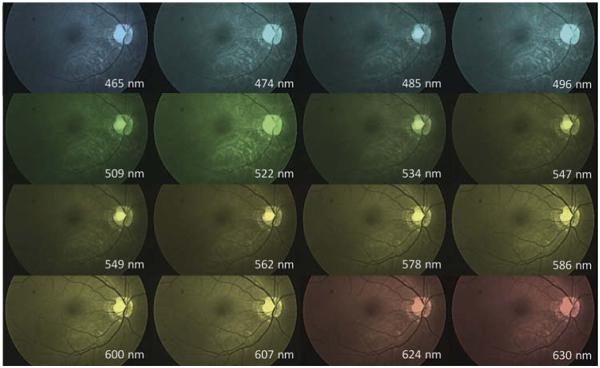

An example of visualization of the hyperspectral datacube output is shown in Figure 3. Spectral analysis of the fundus images enhances visualization of distinct features in the retina. For example, vessel detail is best seen in wavelengths greater than 550 nm where hemoglobin strongly absorbs light causing the vessels to appear dark.

Figure 3.

Visualization of hyperspectral datacube with false coloring applied to emphasize the different channels (50° field of view).

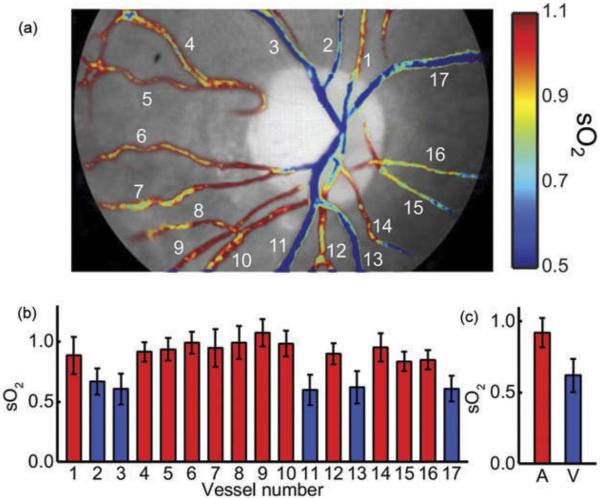

An example of the generated sO2 map is shown in Figure 4. The colored maps help highlight variation between arteries and veins, as well as sO2 variation within the same vessel. The mean sO2 variation within arteries ranged from 3.2% to 14.3% across subjects. In veins, the mean sO2 variation was between 3.2% and 14.9%. In both cases, variability was greatest inside the optic disc.

Figure 4.

Example vessel oxygen saturation (sO2) map. (a) Vessels near the optic disc are manually segmented and then the OD is computed per Equation 2. (b) sO2 for each vessel is shown, and then (c) averages are computed for the image. Arteries are labeled in red and veins are labeled in blue.

The results of the vessel oxygenation analysis are shown in Table 1. The arterial sO2 value reported for each subject represents the mean sO2 across all arteries, where the sO2 of each artery is computed by averaging the sO2 of all pixels in that vessel. Likewise, the reported standard deviation (std) represents the mean, across all arteries, of the standard deviation of sO2 within each artery. The venous measurements were computed in the same fashion. The mean arterial sO2 for all subjects was 90.9% ± 2.5%, whereas the mean venous sO2 for all subjects was 64.5% ± 3.5%. The mean A–V difference varied between 20.5% and 31.9% among the group.

Table 1.

Oximetry results for healthy controls.

| Arteries sO2 (%) |

Veins sO2 (%) |

A–V difference sO2 (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Subject ID | Sex | Age | Mean | std | Mean | std | Mean | std |

| p019 | M | 28 | 92.1 | 5.0 | 62.0 | 3.2 | 30.1 | 6.0 |

| p020 | M | 29 | 93.0 | 3.2 | 61.1 | 2.2 | 31.9 | 3.9 |

| p021 | M | 24 | 89.3 | 8.0 | 64.4 | 7.5 | 25.0 | 10.9 |

| p022 | F | 31 | 89.9 | 13.2 | 58.8 | 14.3 | 31.1 | 19.5 |

| p069 | F | 21 | 92.0 | 12.9 | 64.9 | 14.9 | 27.1 | 19.7 |

| p070 | M | 59 | 85.2 | 6.6 | 61.2 | 5.0 | 24.0 | 8.3 |

| p076 | F | 55 | 92.6 | 14.3 | 62.9 | 11.0 | 29.8 | 18.0 |

| p077 | F | 80 | 89.1 | 7.1 | 66.7 | 5.3 | 22.4 | 8.8 |

| p080 | M | 27 | 91.3 | 6.0 | 70.8 | 5.9 | 20.5 | 8.4 |

| p081 | F | 74 | 95.4 | 9.7 | 70.0 | 7.7 | 25.4 | 12.4 |

| p083 | M | 61 | 91.4 | 8.0 | 64.7 | 8.2 | 26.7 | 11.4 |

| p084 | M | 50 | 91.2 | 8.2 | 67.5 | 6.0 | 23.6 | 10.2 |

Note: sO2: oxygen saturation; std: standard deviation.

To assess the repeatability of the system, we compared the vessel sO2 from six consecutive images of the same eye within 5 minutes. We first spatially registered the six image datasets to ensure that each pixel in different datasets represents the same location in the retina. We then calculated sO2 from the six datasets separately. Finally, we calculated the sO2 standard deviation of each pixel from the six sO2 maps. The standard deviations of sO2 of single pixels within the vessel area are all less than 5%, with an average value of 1.4%, indicating excellent sO2 measurement repeatability.

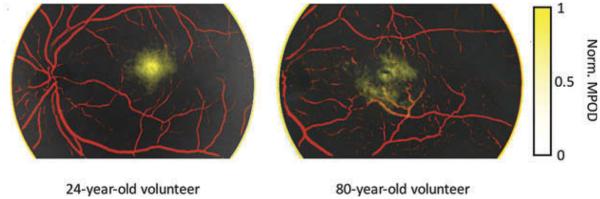

MPOD was calculated (per Equation 3) and mapped in combined with vessel identification (per Equation 4). In the image overlay (Figure 5), we pseudocolored the vessel maps in red and MPODs in yellow. Here we see a uniform distribution of macular pigment in the macula of the 24-year-old subject. In comparison, the macular pigment distribution of the 80-year-old subject is less focal and more variable in density.

Figure 5.

Normalized macular pigment optical densities (yellow) overlaid with contrast-enhanced retinal vessel maps (red) from (a) a 24-year-old volunteer and (b) an 80-year-old volunteer. Field of view, 35°.

Discussion

In this report we demonstrate a snapshot hyperspectral system capable of acquiring high-quality spectral images in vivo. To our knowledge, this is the first Bayer filter mosaic type snapshot hyperspectral detector demonstrated in ophthalmology. This system is compact, easily integrated, and straightforward to operate. The mosaic filter design provides good spectral and spatial resolution without the need for complicated post-processing or image reconstruction.

We have also demonstrated the clinical utility of the system by performing retinal oximetry measurements on a series of healthy subjects. The data from our small cohort is in accordance with previously published retinal oximetry data showing arterial sO2 of healthy subjects between 93–98% ± 7–10% and venous sO2 of 65% ± 5–12%.5,7 The variation in the measurement between subjects could be due to physiologic difference in retinal O2 consumption, subclinical pathology (small vessel disease) or differences in media opacity or fundus pigmentation.30,31 In addition, the data from short-period consecutive images on one subject reveals excellent repeatability (average standard deviation 1.4%) in vessel sO2 measurements compared with a previous study (2.5–3.3%).5 These results provide evidence that the system is capable of reliable performance suitable for in-vivo studies.

A limitation of this oximetry method is that it is not valid for vessels overlying the optic nerve head (ONH). As seen in Figure 4, the oximetry maps overlying the ONH were highly variable. From Equation 1, Iout and Iin represent the light reflected in a single pass from the area in and around the vessel. For normal retina, this is a reasonable assumption. However, the turbidity of light reflected from the ONH makes the single pass assumption invalid for vessels overlaying that area.32 For this reason, these vessel segments were exclude from the analysis.

As demonstrated in Figure 5, spectral decomposition of retinal reflectance helps to highlight specific structures in the retina. Using multiple channels of the hyperspectral datacube we have demonstrated the ability to identify, localize, and quantify vessels and macular pigment. Our analysis of MPOD reveals a distribution of macular pigment that is in agreement with previous publications.17,33,34 In the example shown in Figure 5, we see evidence of macular pigment disturbances in the macula of an 80-year-old subject. This likely represents normal physiologic changes in the setting of aging,35–37 although decreased MPOD has also been implicated in pathologic conditions.20 The inherent variation in MPOD measurements, combined with our small sample size would make quantitative comparisons difficult.16,33,35,38,39 Instead, we chose the MPOD maps as a preliminary demonstration, while ultimately a larger cohort is needed to assess the performance of this analysis. We feel that the high resolution spectral–spatial data provided by this system can be harnessed with improved software tools to improve the detection, localization, and even identification of retina components and pathological elements.

One limitation of the system is the presence of significant second-order effects in several channels. In many cases, the second-order contributions of the filters were up to 50% of the intensity of the primary response, making spectral decomposition a challenge. In the current analysis, we corrected for these effects by convoluting the measured spectra with the response of the filters. We are currently exploring options to improve the performance of the system by using different optical filters.

An additional downside of this system is the limited spectral range of the detector. While the 460 nm to 630 nm spectral range is well suited for oximetry and MPOD measurements, it is limited near the UV and IR boundaries of the visible spectra. The mosaic design of the detector creates a tradeoff between spatial and spectral resolution as shown in Figure 1. The mosaic uses 4 × 4 pixels (each pixel is 5.5 μm on a side), making the spatial resolution 22 μm at the detector and roughly 15 μm at the retina. A larger mosaic with more spectral channels will result in a decrease in spatial resolution. Fortunately, a reduction in pixel size can improve the resolution. Future detectors with an expanded spectral range will allow for better color approximation of the data and may help to visualize additional spectral components of the retina that lie outside the current spectral range of this detector.

Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated a Bayer filter snapshot hyperspectral camera capable of instantaneous spatial–spectral datacube acquisition from the fundus of healthy subjects. The size and optical design of the camera make it simple to integrate and operate. We demonstrated robust vessel oximetry and measurement of the MPOD with good repeatability. The versatility and simplicity of this tool make it well suited for further research and clinical applications.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the National Institute of Health (1R01EY021470 (A.A. Fawzi), 1R01EY019951(A.A. Fawzi and H.F. Zhang)), the National Science Foundation (CBET-1055379), and the Illinois Society for Prevention of Blindness (J. Kaluzny).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

ORCID

Amani Fawzi http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9568-3558

References

- 1.Delori FC, Gragoudas ES, Francisco R, Pruett RC. Monochromatic ophthalmoscopy and fundus photography. The normal fundus. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95(5):861–868. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450050139018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernardes R, Serranho P, Lobo C. Digital ocular fundus imaging: a review. Ophthalmologica. 2011;226(4):161–181. doi: 10.1159/000329597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu G, Fei B. Medical hyperspectral imaging: a review. J Biomed Optics. 2014;19(1):10901. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.19.1.010901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geirsdottir A, Palsson O, Hardarson SH, Olafsdottir OB, Kristjansdottir JV, Stefansson E. Retinal vessel oxygen saturation in healthy individuals. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(9):5433–5442. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammer M, Vilser W, Riemer T, Schweitzer D. Retinal vessel oximetry-calibration, compensation for vessel diameter and fundus pigmentation, and reproducibility. J Biomed Optics. 2008;13(5):054015. doi: 10.1117/1.2976032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardarson SH, Stefansson E. Retinal oxygen saturation is altered in diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(4):560–563. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kashani AH, Lopez Jaime GR, Saati S, Martin G, Varma R, Humayun MS. Noninvasive assessment of retinal vascular oxygen content among normal and diabetic human subjects: a study using hyperspectral computed tomographic imaging spectroscopy. Retina. 2014;34(9):1854–1860. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Man RE, Sasongko MB, Xie J, et al. Associations of retinal oximetry in persons with diabetes. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015;43(2):124–131. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hickam JB, Frayser R, Ross JC. A study of retinal venous blood oxygen saturation in human subjects by photographic means. Circulation. 1963;27:375–385. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.27.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beach JM, Schwenzer KJ, Srinivas S, Kim D, Tiedeman JS. Oximetry of retinal vessels by dual-wavelength imaging: calibration and influence of pigmentation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1999;86(2):748–758. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.2.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khoobehi B, Beach JM, Kawano H. Hyperspectral imaging for measurement of oxygen saturation in the optic nerve head. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(5):1464–1472. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mordant DJ, Al-Abboud I, Muyo G, et al. Spectral imaging of the retina. Eye. 2011;25(3):309–320. doi: 10.1038/eye.2010.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schweitzer D, Hammer M, Kraft J, Thamm E, Konigsdorffer E, Strobel J. In vivo measurement of the oxygen saturation of retinal vessels in healthy volunteers. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1999;46(12):1454–1465. doi: 10.1109/10.804573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schweitzer D, Thamm E, Hammer M, Kraft J. A new method for the measurement of oxygen saturation at the human ocular fundus. Int Ophthalmol. 2001;23(4–6):347–353. doi: 10.1023/a:1014458815482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito M, Murayama K, Deguchi T, et al. Oxygen saturation levels in the juxta-papillary retina in eyes with glaucoma. Exp Eye Res. 2008;86(3):512–518. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delori FC, Goger DG, Hammond BR, Snodderly DM, Burns SA. Macular pigment density measured by autofluorescence spectrometry: comparison with reflectometry and heterochromatic flicker photometry. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 2001;18(6):1212–1230. doi: 10.1364/josaa.18.001212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fawzi AA, Lee N, Acton JH, Laine AF, Smith RT. Recovery of macular pigment spectrum in vivo using hyperspectral image analysis. J Biomed Optics. 2011;16(10):106008. doi: 10.1117/1.3640813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van de Kraats J, Kanis MJ, Genders SW, van Norren D. Lutein and zeaxanthin measured separately in the living human retina with fundus reflectometry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(12):5568–5573. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaya S, Weigert G, Pemp B, et al. Comparison of macular pigment in patients with age-related macular degeneration and healthy control subjects - a study using spectral fundus reflectance. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90(5):e399–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2012.02423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nolan JM, Stack J, Loane E, Beatty S. Risk factors for age-related maculopathy are associated with a relative lack of macular pigment. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84(1):61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.08.016. O OD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beatty S, Boulton M, Henson D, Koh HH, Murray IJ. Macular pigment and age related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83(7):867–877. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.7.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Veen RL, Berendschot TT, Makridaki M, Hendrikse F, Carden D, Murray IJ. Correspondence between retinal reflectometry and a flicker-based technique in the measurement of macular pigment spatial profiles. J Biomed Optics. 2009;14(6):064046. doi: 10.1117/1.3275481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nourrit V, Denniss J, Muqit MM, et al. High-resolution hyper-spectral imaging of the retina with a modified fundus camera. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2010;33(10):686–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao L, Smith RT, Tkaczyk TS. Snapshot hyperspectral retinal camera with the Image Mapping Spectrometer (IMS) Biomed Opt Express. 2012;3(1):48–54. doi: 10.1364/BOE.3.000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramella-Roman JC, Mathews SA, Kandimalla H, et al. Measurement of oxygen saturation in the retina with a spectroscopic sensitive multi aperture camera. Opt Express. 2008;16(9):6170–6182. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.006170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson WR, Wilson DW, Fink W, Humayun M, Bearman G. Snapshot hyperspectral imaging in ophthalmology. J Biomed Optics. 2007;12(1):014036. doi: 10.1117/1.2434950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li H, Liu W, Dong B, Kaluzny JV, Fawzi AA, Zhang HF. Snapshot hyperspectral retinal imaging using compact spectral resolving detecter array. J Biophotonics In Press. doi: 10.1002/jbio.201600053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.IMEC Hyperspectral imaging. http://www2.imec.be/be_en/research/image-sensors-and-vision-systems/hyperspectral-imaging.html. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frangi AF, Niessen WJ, Vincken KL, Viergever MA. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Interventation—MICCAI’98. Springer; 1998. Multiscale vessel enhancement filtering; pp. 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris A, Dinn RB, Kagemann L, Rechtman E. A review of methods for human retinal oximetry. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2003;34(2):152–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu W, Jiao S, Zhang HF. Accuracy of retinal oximetry: a Monte Carlo investigation. J Biomed Optics. 2013;18(6):066003. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.18.6.066003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delori FC. Noninvasive technique for oximetry of blood in retinal-vessels. Appl Optics. 1988;27(6):1113–1125. doi: 10.1364/AO.27.001113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berendschot TT, van Norren D. Objective determination of the macular pigment optical density using fundus reflectance spectroscopy. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;430(2):149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snodderly DM, Auran JD, Delori FC. The macular pigment. II. Spatial distribution in primate retinas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1984;25(6):674–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Obana A, Gohto Y, Tanito M, et al. Effect of age and other factors on macular pigment optical density measured with resonance Raman spectroscopy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;252(8):1221–1228. doi: 10.1007/s00417-014-2574-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baptista AM, Nascimento SM. Changes in spatial extent and peak double optical density of human macular pigment with age. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 2014;31(4):A87–92. doi: 10.1364/JOSAA.31.000A87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berendschot TTJM, van Norren D. On the age dependency of the macular pigment optical density. Exp Eye Res. 2005;81(5):602–609. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nolan JM, Stack J, O’Connell E, Beatty S. The relationships between macular pigment optical density and its constituent carotenoids in diet and serum. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(2):571–582. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dragostinoff N, Werkmeister RM, Kaya S, et al. Short- and mid-term repeatability of macular pigment optical density measurements using spectral fundus reflectance. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;250(9):1261–1266. doi: 10.1007/s00417-012-1946-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]