Abstract

Early detection and proper management of kidney rejection are crucial for the long-term health of a transplant recipient. Recipients are normally monitored by serum creatinine measurement and sometimes with graft biopsies. Donor-derived cell-free deoxyribonucleic acid (cfDNA) in the recipient's plasma and/or urine may be a better indicator of acute rejection. We evaluated digital PCR (dPCR) as a system for monitoring graft status using single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based detection of donor DNA in plasma or urine. We compared the detection abilities of the QX200, RainDrop, and QuantStudio 3D dPCR systems. The QX200 was the most accurate and sensitive. Plasma and/or urine samples were isolated from 34 kidney recipients at multiple time points after transplantation, and analyzed by dPCR using the QX200. We found that donor DNA was almost undetectable in plasma DNA samples, whereas a high percentage of donor DNA was measured in urine DNA samples, indicating that urine is a good source of cfDNA for patient monitoring. We found that at least 24% of the highly polymorphic SNPs used to identify individuals could also identify donor cfDNA in transplant patient samples. Our results further showed that autosomal, sex-specific, and mitochondrial SNPs were suitable markers for identifying donor cfDNA. Finally, we found that donor-derived cfDNA measurement by dPCR was not sufficient to predict a patient's clinical condition. Our results indicate that donor-derived cfDNA is not an accurate predictor of kidney status in kidney transplant patients.

Keywords: acute rejection, cell-free DNA, digital PCR, kidney transplantation

Introduction

Kidney transplantation is a necessity for patients who have non-recovery of kidney function. Transplant patients usually have a high risk of complications in the early post-operative period (3–6 months) [1]. Diagnoses of kidney dysfunction include acute rejection, acute tubular necrosis, glomerulonephritis, calcineurin inhibitor toxicity, and non-specific injury. Early diagnosis and treatment are very important for a patient's long-term health. Biopsy and measurement of creatinine levels are standard ways to monitor patients [2]. The disadvantage of using biopsies is that they cause injury to the kidney, and can cause secondary complications. The disadvantage of measuring creatinine levels is that this is a low specificity assay. For these reasons, noninvasive diagnostic tools that can outperform the current standard transplantation monitoring system are needed. It has been reported that total cell-free deoxyribonucleic acid (cfDNA) or donor-derived cfDNA in plasma or urine can be used as a potential biomarker for the early detection of kidney dysfunction after transplantation [3,4,5,6,7]. Several different cfDNA quantification techniques have been investigated for use in examining cfDNA as biomarker of acute rejection. These techniques include quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using Y-chromosome genes [1], digital PCR (dPCR) using Y-chromosome genes [8,9] or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [10], and massive parallel shotgun sequencing using SNPs [8,11]. Several studies reported that dPCR was especially cost-effective, rapid, and sensitive for quantifying circulating donor DNA in plasma or urine samples from transplant patients [9,10,12]. However, it is still not clear whether dPCR can be used in a clinic to accurately monitor the conditions of transplanted organs. In this study, we evaluated dPCR-based kidney transplant recipient monitoring by measuring the levels of circulating donor-derived cfDNA in patient plasma and/or urine.

Methods

Patients

As a pilot test, genomic DNA and cfDNA were isolated from three different pairs of donor and recipient samples (blood, plasma, and urine) collected at Asan Medical Center. For clinical sample screening using SNP-based dPCR, the blood (n = 72), plasma (n = 72), and urine (n = 69) samples were collected from a total of 34 kidney transplant recipients with different clinical conditions at Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong. Patient were stable, or experiencing acute rejection, acute tubular necrosis, glomerulonephritis, calcineurin-inhibitor toxicity, or suffering from non-specific injury. The study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Asan Medical Center and Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Preparation of genomic DNA and cfDNA for dPCR

Blood was centrifuged at 1,800 ×g for 10 minutes to separate the buffy coat from the plasma. The buffy coat was used to isolate genomic DNA using a Qiagen DNA blood mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). According to standard protocols, genomic DNA was eluted using 200 µL of elution buffer. Plasma (1 mL) and urine (3 mL) were centrifuged at 11,000 ×g for 3 min, and 1,800 ×g for 10 min, respectively, to remove cells. cfDNA was isolated from plasma and urine using a Qiagen Circulating Nucleic Acid kit and eluted using 50 µL of elution buffer. DNA was stored at −20℃.

Selection of donor-specific SNP markers

In order to differentiate donor DNA from recipient DNA, SNP markers were selected from a panel of SNPs used for sex determination or identification of individuals [13]. A total of seven highly polymorphic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) SNPs were also selected from mtDB (http://www.mtdb.igp.uu.se/) and in-house Korean mtDNA variant data, and were used to detect donor-specific mtDNA in patient samples. We designed several TaqMan probe sets to detect each of two alleles in our dPCR screen using the fluorescent dyes FAM and VIC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

dPCR experiments

Initially, three different dPCR systems (QX200, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA; RainDrop, RainDance Technologies, Billrica, MA, USA; QuantStudio 3D, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were tested to compare their sensitivity and accuracy using SNP rs543840 (A/G) with 10 ng of control genomic DNA having one of three known genotypes (AA, AG, or GG). For the quantification of cfDNA in transplant patient plasma and urine, the Bio-Rad QX200 dPCR system was used with 3.5 µL of isolated sample cfDNA. All reactions were prepared using the manufacturer's standard protocol (Bio-Rad). Each reaction contained 10 µL of 2× ddPCR Supermix for Probes (Bio-Rad), 1 µL of 40× TaqMan Probe (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 3.5 or 5 µL of cfDNA (1:20 diluted cfDNA in the case of mtDNA detection) as template, and the distilled water necessary to reach a total reaction volume of 20 µL. Droplets were generated using the QX200 droplet generator (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's protocols. The PCR cycling conditions were 95℃ for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94℃ for 30 s and 60℃ for 60 s, with a final 10-min incubation at 98℃. Droplets were read in the QX200 droplet reader, and analyzed using the QuantaSoft software, version 1.6.6 (Bio-Rad). We measured the positive counts of each allele directly, or the calculated counts of each allele based on a Poisson distribution. These values were then used to express the minor allele (donor DNA) counts as a percentage of the total DNA counts. In case of homozygous donors (two A alleles) and recipients (two B alleles), the donor DNA counts and percentages were easy to calculate because the donor DNA counts were simply the positive counts of the A allele. However, in case of heterozygous donors (A and B alleles) and homozygous recipients (two B alleles), the corrected donor DNA counts were calculated by doubling the total positive counts of the A allele, whereas the corrected recipient DNA counts were calculated by subtracting the total positive counts of the A allele from the total positive counts of the B allele. Finally, the donor DNA percentage was calculated as the corrected donor DNA counts divided by the total positive DNA counts, multiplied by 100.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The level of statistical significance (p) was calculated with a student's t test or ANOVA test to compare clinical subgroups of transplant patients, such as stable and acute rejection. Pearson's correlation coefficients (r) were also calculated to compare SNP marker types to detect donor cfDNA. Linkage between highly polymorphic mitochondrial SNP markers were examined with the square of correlation coefficients (r2) using HapAnalyzer program [14].

Results

Evaluation of SNP detection in genomic DNA by three dPCR instruments

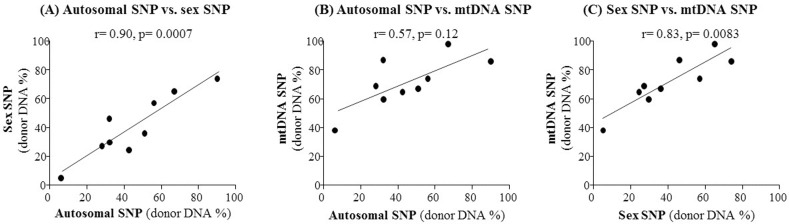

Prior to using dPCR to detect donor DNA in transplant patient cfDNA samples, we tested the performance of three different dPCR instruments (Bio-Rad QX200, RainDance RainDrop, and Life Technologies QuantStudio 3D) using control genomic DNA samples with three different genotypes of a SNP (rs543840) (sample 1, AA; sample 2, AG; sample 3, GG) (Fig. 1). The Bio-Rad QX200 system had the highest counts and best genotype clustering in all samples. The RainDrop system had a high false-positive rate in the homozygous samples (sample 1, 1.19%; sample 3, 17.75%), and an unequal allelic ratio (A:G = 1:3) in the heterozygous sample (sample 2). The QuantStudio 3D system gave clear clustering in the heterozygous sample (sample 2) but gave weak clustering (sample 1) and high false positive counts (sample 3) in the homozygous samples. Therefore, among the three dPCR systems tested in this study, the Bio-Rad QX200 system had the best performance in detecting SNPs in control genomic DNA samples. The Bio-Rad QX200 dPCR system was thus chosen for dPCR screening of transplant patient cfDNA samples.

Fig. 1. Comparison of the sensitivity and accuracy of three different digital polymerase chain reaction systems (Bio-Rad QX200, RainDance RainDrop, and Life Technologies QuantStudio 3D) in single nucleotide polymorphism rs543840 (A/G) detection in control genomic DNA samples. The numbers of positive counts for each allele are shown in the genotyping image plots.

Selection of highly polymorphic autosomal and mitochondrial SNPs as donor-specific DNA markers

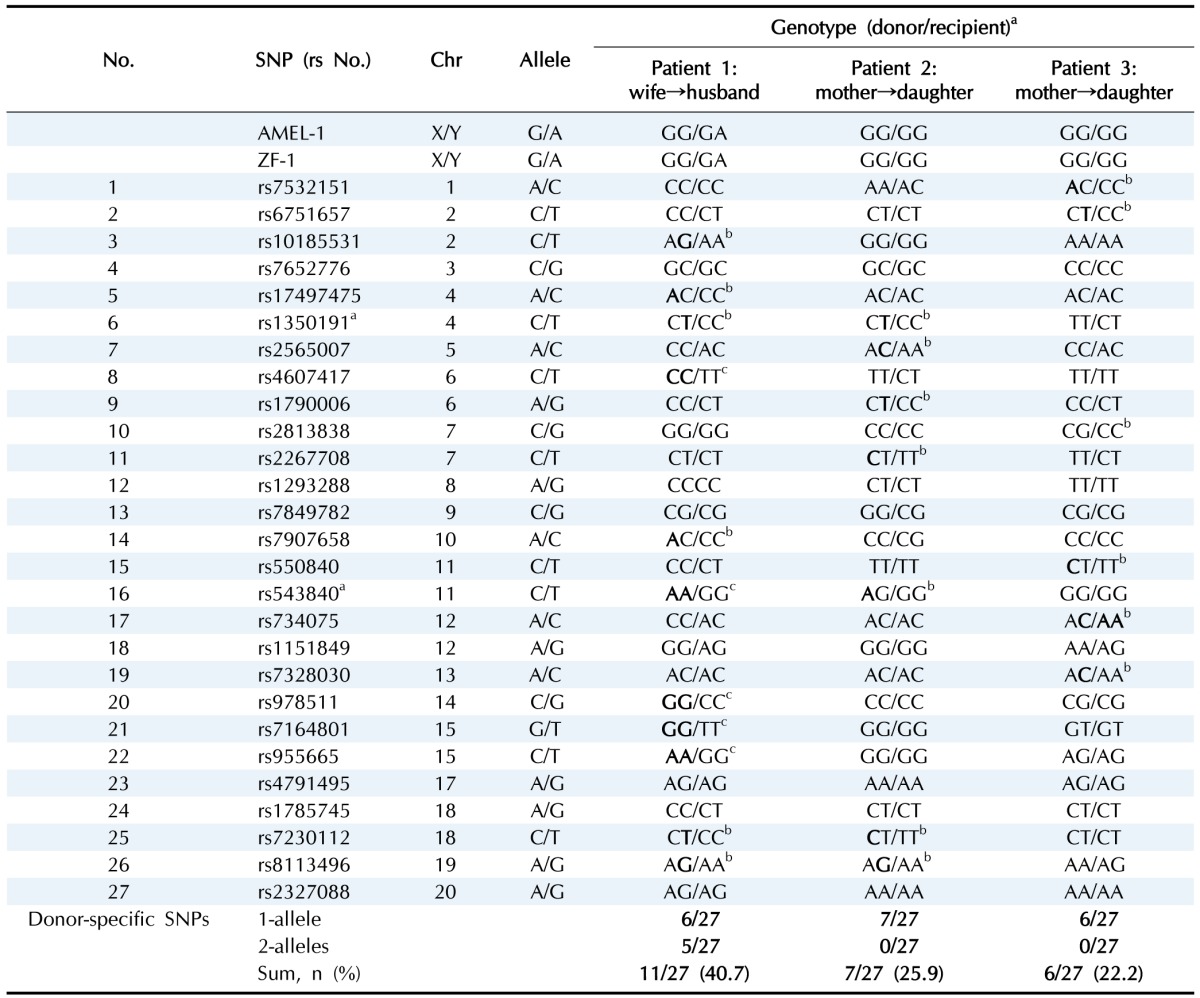

Several studies have used genetic signature detection of transplanted organs based on SNPs [8,10,15,16]. However, it is still not clear how many SNPs should be genotyped for accurate detection of donor-specific DNA in transplant patients. In this study, we tested the ability of 27 highly polymorphic SNPs used for human identification to distinguish donor-specific DNA from paired transplant patient DNA. To determine the appropriate number of SNPs for donor-specific DNA detection, we screened the genotypes of the 27 SNPs, and the genotypes of two additional sex-specific SNPs used for sex determination (AMEL-1 & ZF-1). The genomic DNA of three kidney donor and recipient pairs was analyzed by capillary sequencing (Table 1). In the case of a transplant between unrelated individuals (patient 1, wife to husband), among 27 markers, 11 donor-specific SNPs (five homozygous and six heterozygous alleles; 40.7%) were identified. However, in case of transplants between related individuals (patient 2 and patient 3, both cases are transplants from mother to daughter), seven and six heterozygous SNPs (25.9% and 22.2% of alleles tested) were detected as donor-specific markers, respectively (Table 1). These data indicate that using approximately 24% of the highly polymorphic SNPs used to identify individuals would be sufficient to detect donor-specific DNA in transplant monitoring, even in transplants between related individuals.

Table 1. Summary of data from genotyping three transplant patients, with donor-recipient paired DNA samples, using two sex-specific SNPs and 27 autosomal SNPs.

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

aAll 27 SNPs for human identification were genotyped by capillary sequencing and donor-specific SNPs are marked by bold and symbols; bHeterozygote for one allele having donor-specific SNPs in a diploid genome; cHomozygote for two alleles having donor-specific SNPs in a diploid genome. Sex-specific SNPs (AMEL-1 & ZF-1) were also selected from our previous study 13.

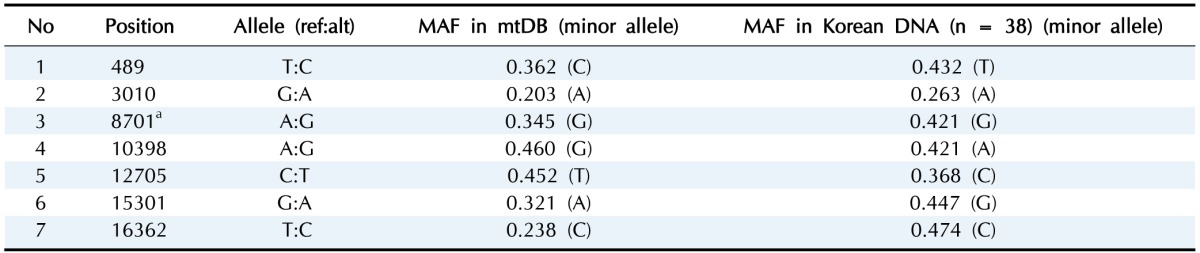

The detection of nuclear DNA is not easy due to limited amounts of donor DNA in plasma or urine cfDNA samples. However, high copy numbers of the mitochondrial genome are usually present in cfDNA samples. In order to identify candidate mtDNA variants as donor-specific DNA markers, we selected 19 highly polymorphic mitochondrial SNPs with high minor allele frequency (MAF > 0.20) at mtDB (http://www.mtdb.igp.uu.se/) and one in-house mtDNA variant data with MAF > 0.30 (n = 24 Korean DNA samples). For the detection of donor-specific DNA in plasma or urine cfDNA samples after transplantation, a total of seven highly polymorphic mitochondrial SNPs were finally selected based on having high MAFs (> 0.2) in additional Korean DNA samples (n = 38), and following exclusion of three tightly linked variants (linkage with r2 = 1) (Table 2).

Table 2. Selection of seven highly polymorphic mitochondrial SNPs for human identification.

We selected mitochondrial polymorphic variants with minor allele frequency (MAF > 0.20) from the mtDB (http://www.mtdb.igp.uu.se/) and MAF > 0.3 in Korean DNA samples (n = 24).

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA.

aWe found that mtDNA-8701 was in complete linkage (r2 = 1) with mtDNA-9540, mtDNA-10873, and mtDNA-14783 in Korean population samples (n = 38).

Detection of donor-specific DNA in kidney recipients' plasma and urine cfDNA samples using dPCR

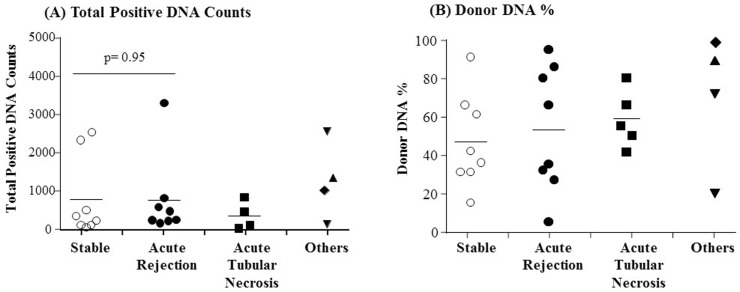

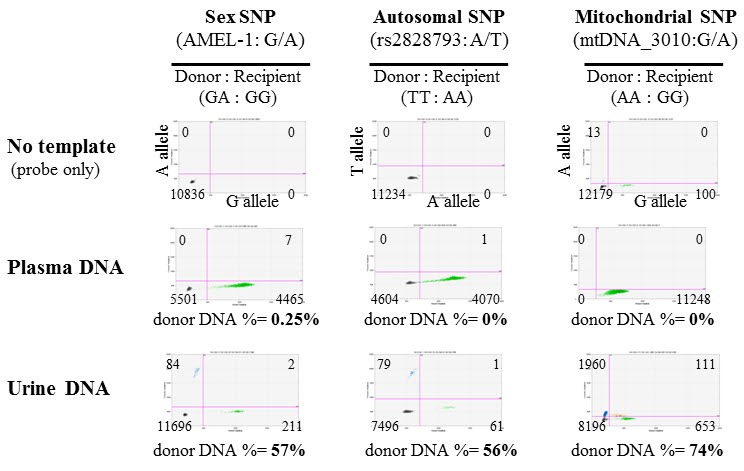

For the detection of donor-specific DNA variants in cfDNA samples from transplant patients, we finally selected 36 candidate SNPs from three different DNA sources: two SNPs commonly used for sex-determination, 27 autosomal SNPs commonly used for human identification, and seven highly polymorphic mitochondrial SNPs. As a pilot test, we performed dPCR screening with one SNP from each category, and examined plasma and urine cfDNA samples from a kidney transplant recipient with acute tubular necrosis at day 18 after transplantation. Using any of the three SNPs, we were able to detect circulating donor DNA in urine cfDNA samples, but not in plasma cfDNA samples (Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 2, limited amounts of donor-specific DNA (0%–0.25% of total DNA) were detected in plasma cfDNA samples, whereas high amounts of donor-specific DNA (56%–74% of total DNA) were detected in urine cfDNA samples using all three SNP markers. Thus, our results indicate that plasma cfDNA is not appropriate for kidney transplant monitoring, but urine is a very good source of cfDNA for monitoring kidney transplant patients. Furthermore, using the sex-specific and autosomal SNPs led to identification of a very similar percentage of donor-specific DNA (57% vs. 56%). On the other hand, a higher percentage of donor-specific DNA (74%) was detected using the mtDNA SNP as a marker (Fig. 2). We also observed a strong correlation between the mtDNA and nuclear DNA SNPs (Pearson's correlation coefficient r = 0.57–0.83) as well as between sex-specific and autosomal SNPs (r = 0.90, p = 0.0007) in a comparison of multiple sample tests (Fig. 3). These results indicate that dPCR can be useful for SNP-based detection of donor DNA in the urine of kidney recipients following transplantation.

Fig. 2. Detection of a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) used for determining sex (AMEL-1), an autosomal SNP for human identification (rs28-28793), and a mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) SNP (mtDNA_3010) using digital polymerase chain reaction in plasma and urine cell-free deoxyribonucleic acid samples. Samples were isolated from a patient with acute tubular necrosis 18 days after receiving a kidney transplant. In this patient (patient 24), an unrelated male donor's organ was transplanted into a female recipient.

Fig. 3. Comparison of three different types of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (autosomal, mitochondrial, or sex-specific) as markers for quantification of donor DNA in kidney transplant recipients' urine. The correlation coefficient (r) was calculated for pairwise comparisons of the donor DNA percentages estimated using the three markers, with the autosomal versus the sex-specific SNP shown (A), the autosomal versus the mitochondrial SNP shown (B), and the sex-specific versus the mitochondrial SNP shown (C).

Evaluation of dPCR screening of clinical samples from kidney transplant recipients

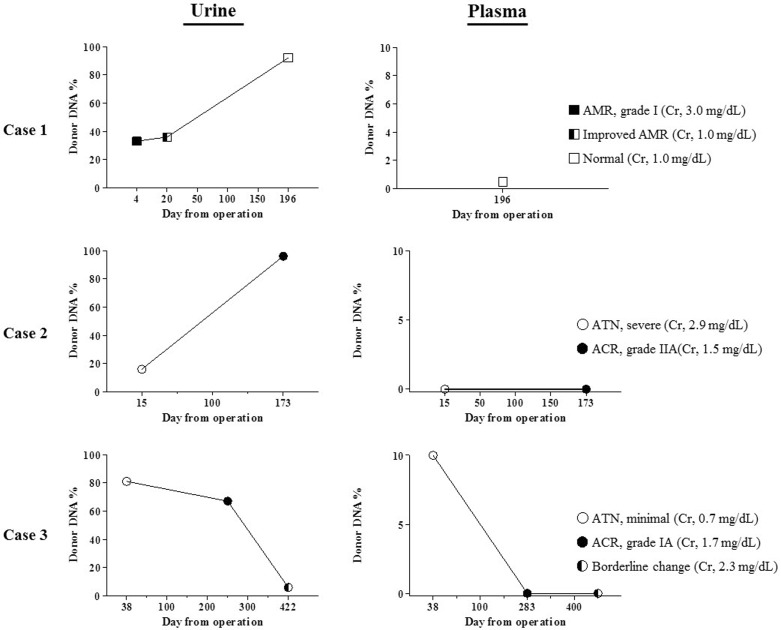

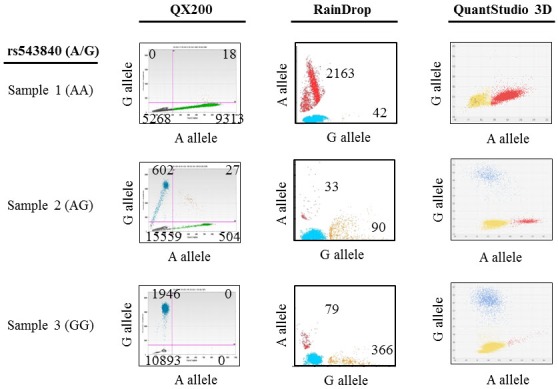

To investigate the clinical validity of dPCR for kidney transplantation monitoring, we screened a total of 34 kidney transplant patients' urine cfDNA samples collected at multiple time points after transplantation. Among the 34 patients, we selected 11 patients based on TaqMan probe (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) availability to detect SNPs for donor-specific DNA (plasma samples n = 28, urine samples n = 25). We measured the total positive DNA counts, and the percentage of the total positive DNA counts that were from donor DNA (Fig. 4). In a pilot test, limited amounts of donor-specific DNA were detected in plasma cfDNA samples (mean, 1%; range, 0% to 10%). Conversely, in urine cfDNA samples, a large percentage of the total positive DNA counts were from donor DNA (mean, 55%; range, 6% to 100%). However, the differences in both total positive DNA counts, and donor DNA percentages, were not significant between clinical groups (Fig. 4). We next tested whether circulating mtDNA could be used to monitor graft status in transplant patients. We measured the circulating mtDNA levels in plasma and urine cfDNA samples from kidney transplant patients, using the mitochondrial variant marker mtDNA_12705. We found that the circulating mtDNA levels of transplant patients likewise could not be used to distinguish the clinical conditions of the patients (data not shown). The donor-specific cfDNA in urine samples was not consistent with the graft pathology, or the results of serum creatinine analysis (Fig. 5). Plasma donor-specific DNA was not detected in most cases, but when detected it was also inconsistent with graft function and patient status. These results indicate that SNP-based dPCR detection of donor DNA is not a useful diagnostic for determining the clinical conditions of kidney transplant patients.

Fig. 4. Detection of total positive DNA counts (A) and donor DNA % (B) in urine cell-free deoxyribonucleic acid samples using digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR) based single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-identification. Patients are grouped based on clinical condition as indicated along the x-axis. The “Others” group includes two injured patients (▼), one patient with calcineurin inhibitor toxicity (▲) and one patient with glomerulonephritis (◆). The donor DNA counts were detected by SNP-based dPCR using an autosomal SNP or a sex-specific SNP as described in the Methods. Mean values are indicated with horizontal bar in each group. No significance of the difference between the mean total positive DNA counts for the stable group and acute rejection group was observed by a student's t test (A).

Fig. 5. Change in donor DNA percentage over time after transplantation is presented for three representative patients. Urine (left) and plasma (right) donor-specific cell-free deoxyribonucleic acid (cfDNA) were expressed as percentage of the total cfDNA. The legends show details about the conditions of the patient, such as acute tubular necrosis (ATN), acute cellular rejection (ACR), antibody-mediated rejection (AMR), or borderline. The grades of rejection (IA, IIA) and creatinine levels (Cr) were also presented in the Figure.

Discussion

Acute and chronic rejection play critical roles in graft function, and patient survival, following kidney transplantation [17]. Therefore, monitoring for kidney rejection is very important. The standard for monitoring kidney transplant patients is to regularly check serum creatinine levels [2]. Assessment of graft function can be supplemented with a surveillance graft biopsy, but the role of this invasive procedure in monitoring stable, un-sensitized patients is debatable. These methods have drawbacks including low specificity and injury, respectively. Many researchers have tried to develop alternative or supplementary methods for monitoring transplant recipients. One of the promising methods of monitoring for graft rejection is dPCR [9,10,12]. However, it is still not clear whether dPCR is accurate enough to use for the monitoring of the clinical conditions of transplant patients. Thus, in this study, we evaluated noninvasive dPCR based measurement of donor DNA levels in patient plasma and urine as a technique for determining the clinical conditions of kidney transplant patients.

dPCR is a sensitive and cost-effective method to quantify circulating nucleic acids in samples with a high background of homologous sequences [18]. We initially compared three dPCR instruments (QX200, RainDrop, and QuantStudio 3D) using control genomic DNA samples with known genotypes. The Bio-Rad QX200 dPCR system had the best performance coupled with accurate DNA quantification (Fig. 1). The Bio-Rad QX200 droplet digital PCR uses emulsion chemistry to partition 20 µL nucleic acid samples into approximately 20,000 oil-encapsulated nanodroplets to produce data with high sensitivity [19]. On the other hand, the RainDrop and QuantStudio 3D dPCR systems had high false positive rates and inaccurate genotype clustering (Fig. 1). The QX200 dPCR system robustly detected high copy numbers of donor-specific cfDNA within kidney transplant patient urine cfDNA samples, but not plasma cfDNA samples. These results indicate that urine is a reliable source of cfDNA that can be analyzed by dPCR to determine the levels of donor-specific cfDNA following kidney transplantation. The weak detection of donor-derived cfDNA in plasma samples was likely due to the high background of recipient DNA from hematopoietic cells [16,20]. Next-generation sequencing methods can be used with plasma DNA samples for transplant monitoring with good performance [8] because next-generation sequencing has better detection power than dPCR [21]. However, next-generation sequencing is difficult and expensive to use in a clinical setting. Preamplification of cfDNA by PCR is another option to enrich the cfDNA isolated from plasma prior to dPCR screening, and this approach has been used in a previous study [10].

Highly polymorphic SNPs can be used to detect donor-specific DNA in transplant recipients. Some researchers have used Y-chromosome markers to identify and measure donor DNA in gender-mismatched transplantations [9,21,22]. Also, many studies have used SNPs to determine the percentage of donor-derived cfDNA with dPCR [10] or next-generation sequencing [8]. In this study, we used highly polymorphic nuclear SNPs that had been used for identifying individuals [13] to detect and measure donor DNA. We evaluated multiple SNPs, including autosomal, sex-specific, and mitochondrial SNPs. Highly polymorphic autosomal SNPs were excellent for identifying donor-specific DNA variants. As shown in Table 1, as few as 24% of the autosomal SNPs used for human identification are needed for donor DNA identification, even in transplants between related individuals. In addition, we confirmed that mtDNA markers are ideal for donor-specific DNA detection in circulating cfDNA, although they cannot be used when transplants occur between family members of the same mitochondrial lineage. Another issue when using mtDNA SNPs as markers in transplantation monitoring is the limited availability of highly polymorphic mitochondrial SNPs, and the high linkage between these SNPs (Table 2). Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 2, the percentage of mtDNA that was donor-derived in urine did not match the percentage of nuclear DNA that was donor-derived. It has been reported that mtDNA concentration is highly affected by the blood-processing protocol [23], and no correlation was also observed between the levels of circulating mtDNA and genomic DNA in previous studies [24,25]. Therefore, mtDNA markers may not be better than autosomal SNPs for transplantation monitoring because the donor-derived mtDNA levels in plasma and urine may vary widely between transplant patients, depending on the cell types involved in different pathological conditions. We also found that sex-specific SNPs were as useful as autosomal SNPs to monitor transplanted organ status in cases of gender-mismatched transplantation, particularly when the donors are male (Fig. 2).

In kidney transplantation patients, very limited numbers of donor DNA were detected in plasma, whereas sufficient numbers of donor DNA were detected in urine samples. Therefore, for the detection of donor DNA in kidney transplantation, we think that minimum number of DNA copies is 10 copies and 100 copies for plasma and urine samples, respectively. In this study, we found that urine was a much better source of cfDNA than plasma, because it contained higher copy numbers of DNA. This observation is consistent with previously published findings [9,22,26]. Plasma donor-derived cfDNA levels might also be correlated with the size of grafted organ. Even when stable, liver transplant patients showed higher levels of donor-derived cfDNA than kidney or heart transplantation patients [10]. Because of the limited amount of donor-specific cfDNA in blood, a plasma sample might not be suitable for detecting subtle injuries to the grafted kidney. In contrast, urine contains sufficient amounts of donor-specific cfDNA, even in patients with no abnormal pathology. Perhaps not surprisingly, given the massive tubular network, 2,000–7,000 cells are detached from this system daily and can be collected in urine [27]. Degradation of detached tubular cells could be a source of urinary cfDNA. Our results show that the mean percentage of cfDNA that was donor-specific cfDNA was 53.3% (range, 21% to 92%) in patients with stable graft function and no pathological abnormalities. We can assume that half of the urinary cfDNA originated from the kidney, whereas the other half might be derived from the urinary tract. Our hypothesis was that a damaged or rejected graft would have shown increased excretion of donor-specific cfDNA, and this would be detected in the urine. However, in clinical sample screening, although dPCR accurately detected donor-specific DNA in urine cfDNA samples, we could not find any statistically significant difference between patients with different clinical conditions. The amount of urinary cfDNA was highly variable, even in stable patients, and was not correlated with graft pathology or function. We think that multiple factors, such as patient age, body weight, time after operation, clinical complications, and variability in sample preparation could contribute to the high inter-patient differences in cfDNA levels. Consistent with our results, high inter-patient variation in cfDNA has been also demonstrated in a previous kidney transplantation study [9].

In conclusion, noninvasive monitoring of the levels of donor-specific cfDNA is possible, and is a promising approach to tracking graft status and detecting clinical conditions such as acute rejection. However, due to high inter-patient variation, and the complexity of patient cfDNA samples, accurate prediction of a patient's clinical condition is currently not possible. Therefore, further optimization of donor-derived cfDNA measurement by dPCR is necessary before this technique can be implemented clinically for noninvasive monitoring of kidney transplant recipients.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of our patients for participating in this study. We also thank the Bio-Rad, RainDance, and Life Technologies for technical support during dPCR tests. This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (NRF-2015R1D1A1A01057371), and a grant from the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI13C1232).

References

- 1.García Moreira V, Prieto García B, Baltar Martín JM, Ortega Suárez F, Alvarez FV. Cell-free DNA as a noninvasive acute rejection marker in renal transplantation. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1958–1966. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.129072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Josephson MA. Monitoring and managing graft health in the kidney transplant recipient. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1774–1780. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01230211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lichtenstein AV, Melkonyan HS, Tomei LD, Umansky SR. Circulating nucleic acids and apoptosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;945:239–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gahan PB, Swaminathan R. Circulating nucleic acids in plasma and serum: recent developments. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1137:1–6. doi: 10.1196/annals.1448.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swarup V, Rajeswari MR. Circulating (cell-free) nucleic acids: a promising, non-invasive tool for early detection of several human diseases. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:795–799. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tong YK, Lo YM. Diagnostic developments involving cell-free (circulating) nucleic acids. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;363:187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2005.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gielis EM, Ledeganck KJ, De Winter BY, Del Favero J, Bosmans JL, Claas FH, et al. Cell-free DNA: an upcoming biomarker in transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:2541–2551. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snyder TM, Khush KK, Valantine HA, Quake SR. Universal noninvasive detection of solid organ transplant rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:6229–6234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013924108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sigdel TK, Vitalone MJ, Tran TQ, Dai H, Hsieh SC, Salvatierra O, et al. A rapid noninvasive assay for the detection of renal transplant injury. Transplantation. 2013;96:97–101. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318295ee5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beck J, Bierau S, Balzer S, Andag R, Kanzow P, Schmitz J, et al. Digital droplet PCR for rapid quantification of donor DNA in the circulation of transplant recipients as a potential universal biomarker of graft injury. Clin Chem. 2013;59:1732–1741. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.210328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Vlaminck I, Valantine HA, Snyder TM, Strehl C, Cohen G, Luikart H, et al. Circulating cell-free DNA enables noninvasive diagnosis of heart transplant rejection. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:241ra77. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmermann BG, Grill S, Holzgreve W, Zhong XY, Jackson LG, Hahn S. Digital PCR: a powerful new tool for noninvasive prenatal diagnosis? Prenat Diagn. 2008;28:1087–1093. doi: 10.1002/pd.2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JJ, Han BG, Lee HI, Yoo HW, Lee JK. Development of SNP-based human identification system. Int J Legal Med. 2010;124:125–131. doi: 10.1007/s00414-009-0389-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung HY, Park JS, Park YJ, Kim YJ, Kimm K, Koh IS. Hap-Analyzer: minimum haplotype analysis system for association studies. Genomics Inform. 2004;2:107–109. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo YM, Tein MS, Pang CC, Yeung CK, Tong KL, Hjelm NM. Presence of donor-specific DNA in plasma of kidney and liver-transplant recipients. Lancet. 1998;351:1329–1330. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)79055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lui YY, Woo KS, Wang AY, Yeung CK, Li PK, Chau E, et al. Origin of plasma cell-free DNA after solid organ transplantation. Clin Chem. 2003;49:495–496. doi: 10.1373/49.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nankivell BJ, Alexander SI. Rejection of the kidney allograft. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1451–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0902927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hudecova I. Digital PCR analysis of circulating nucleic acids. Clin Biochem. 2015;48:948–956. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hindson BJ, Ness KD, Masquelier DA, Belgrader P, Heredia NJ, Makarewicz AJ, et al. High-throughput droplet digital PCR system for absolute quantitation of DNA copy number. Anal Chem. 2011;83:8604–8610. doi: 10.1021/ac202028g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lui YY, Chik KW, Chiu RW, Ho CY, Lam CW, Lo YM. Predominant hematopoietic origin of cell-free DNA in plasma and serum after sex-mismatched bone marrow transplantation. Clin Chem. 2002;48:421–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hahn S, Hösli I, Lapaire O. Non-invasive prenatal diagnostics using next generation sequencing: technical, legal and social challenges. Expert Opin Med Diagn. 2012;6:517–528. doi: 10.1517/17530059.2012.703650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Tong KL, Li PK, Chan AY, Yeung CK, Pang CC, et al. Presence of donor- and recipient-derived DNA in cell-free urine samples of renal transplantation recipients: urinary DNA chimerism. Clin Chem. 1999;45:1741–1746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiu RW, Chan LY, Lam NY, Tsui NB, Ng EK, Rainer TH, et al. Quantitative analysis of circulating mitochondrial DNA in plasma. Clin Chem. 2003;49:719–726. doi: 10.1373/49.5.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehra N, Penning M, Maas J, van Daal N, Giles RH, Voest EE. Circulating mitochondrial nucleic acids have prognostic value for survival in patients with advanced prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(2 Pt 1):421–426. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zachariah RR, Schmid S, Buerki N, Radpour R, Holzgreve W, Zhong X. Levels of circulating cell-free nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in benign and malignant ovarian tumors. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:843–850. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181867bc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhong XY, Hahn D, Troeger C, Klemm A, Stein G, Thomson P, et al. Cell-free DNA in urine: a marker for kidney graft rejection, but not for prenatal diagnosis? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;945:250–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rahmoune H, Thompson PW, Ward JM, Smith CD, Hong G, Brown J. Glucose transporters in human renal proximal tubular cells isolated from the urine of patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:3427–3434. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.12.3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]