Abstract

Tumor tissues from biopsies or surgery are major sources for the next generation sequencing (NGS) study, but these procedures are invasive and have limitation to overcome intratumor heterogeneity. Recent studies have shown that driver alterations in tumor tissues can be detected by liquid biopsy which is a less invasive technique capable of both capturing the tumor heterogeneity and overcoming the difficulty in tissue sampling. However, it is still unclear whether the driver alterations in liquid biopsy can be detected by targeted NGS and how those related to the tissue biopsy. In this study, we performed whole-exome sequencing for a breast cancer tissue and identified PTEN p.H259fs*7 frameshift mutation. In the plasma DNA (liquid biopsy) analysis by targeted NGS, the same variant initially identified in the tumor tissue was also detected with low variant allele frequency. This mutation was subsequently validated by digital polymerase chain reaction in liquid biopsy. Our result confirm that driver alterations identified in the tumor tissue were detected in liquid biopsy by targeted NGS as well, and suggest that a higher depth of sequencing coverage is needed for detection of genomic alterations in a liquid biopsy.

Keywords: breast neoplasms, CDK4 amplification, circulating tumor DNA, liquid biopsy, next generation sequencing, PTEN mutation

Next generation sequencing (NGS) technology has not only revolutionized cancer research but also is currently being used to guide clinicians' decision-making for cancer treatments. Although tumor tissues from biopsies or surgery are major sources for the NGS study of primary, metastatic and resistant tumors, these serial tumor biopsies are often invasive procedures limited to certain locations and not easily acceptable in the clinic. More importantly, tissue biopsy has a severe limitation in view of the pronounced genomic and phenotypic heterogeneity of the tumor tissues [1]. To overcome the limitations of tissue biopsies or surgery, a less invasive technique capable of both capturing the tumor heterogeneity and overcoming the difficulty in tissue sampling during the course of therapy is needed. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is comprised of small fragments of DNA released from cells undergoing apoptosis or necrosis in tumor tissues [2]. Recent studies have shown that driver alterations in tumor tissues can be detected by liquid biopsy for ctDNA [3]. However, it is still uncertain whether the driver alterations in ctDNA can be detected by targeted NGS and how those related to the tissue biopsy.

A 56-year old woman was referred to the oncology department for evaluation of her right shoulder pain. She was previously diagnosed as a breast cancer 6 years ago. The patient was treated with quadrantectomy along with axillary node dissection (invasive ductal carcinoma, pT2N0M0, estrogen receptor [ER] positive, progesterone receptor positive and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 [HER2] negative), adjuvant radiation of the left breast, and adjuvant toremifen (an oral selective ER modulator) for 5 years. Seven months after the termination of adjuvant toremifen, the patient a pathologic fracture of right distal clavicle, multiple bone, lung and liver metastases (Supplementary Fig. 1). During 3 years of the systemic treatment, the patient had progression of chest, liver and bone metastases (Supplementary Fig. 2).

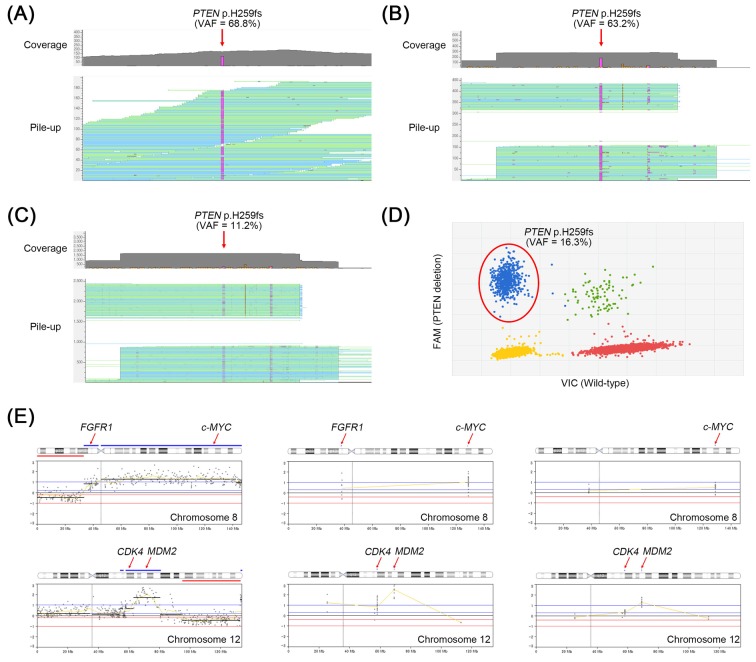

To identify the genetic alterations in the tumor tissue, we performed whole-exome sequencing (WES) for the cancer tissue metastasized to femur along with her matched normal DNA form peripheral blood. Generation and processing of the sequencing data were performed as previously described [4]. In the WES, a total of 53 nonsilent somatic mutations and 23 copy number alterations (CNAs) were detected (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Among them, PTEN p.H259fs*7 frameshift mutation (Fig. 1A) as well as FGFR1, c-MYC, CDK4, and MDM2 amplifications (Fig. 1E) were identified as driver alterations in this tumor.

Fig. 1. PTEN frameshift mutation identified in a breast tumor tissue and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). H259fs mutation is detected by the whole-exome sequencing (WES) (A) and OncoChase targeted sequencing (B) in the breast tumor. (C) The same mutation is also detected by the OncoChase targeted sequencing in the ctDNA. (D) Validation of the PTEN mutation by a digital polymerase chain reaction in ctDNA. In all experiments, the PTEN mutation was not detected in the matched normal DNA. (E) Copy number alterations identified in breast tumor or ctDNA by next generation sequencing. Amplification of FGFR1, c-MYC, CDK4, and MDM2 are detected in the tumor tissue by WES (left panel). Among them, c-MYC, CDK4, and MDM2 amplifications are consistently detected in the tumor tissue (middle panel) or ctDNA (right panel) by OncoChase targeted panel sequencing. The x-axis represents genomic position and the y-axis represents the relative depth ratio (tumor/matched normal) in log2 scale. VAF, variant allele frequency.

To validate these, the metastatic tumor and matched normal samples of the patient were re-analyzed by a targeted NGS. Targeted NGS was performed using the OncoChase Cancer Panel v0.9 (ConnectaGen, Seoul, Korea) consisting of 78 well-characterized cancer genes (Supplementary Table 3) with Ion PGM Dx system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Coverage of depth was 416× for the metastatic tumor sample and 754× for the normal sample. In the OncoChase analysis, all five driver alterations previously identified in the WES were consistently detected (Fig. 1B and 1E). Of note, variant allele frequency (VAF) of PTEN frameshift mutation detected by WES (68.8%) were almost similar to that detected by OncoChase (63.2%), suggesting the OncoChase Cancer Panel may be reliable for the detection of driver alterations.

Next, we analyzed the plasma DNA (liquid biopsy) of the patient using the same cancer panel (OncoChase Cancer Panel v0.9). Coverage of depth was 1,213× for the liquid biopsy sample. The PTEN frameshift mutation initially identified in the tumor tissue was also detected in her liquid biopsy with a VAF of 11.2% (Fig. 1C). This mutation was subsequently validated by digital polymerase chain reaction (Fig. 1D). The ctDNA also harbored c-MYC, CDK4 and MDM2 amplification but signal intensities of the CNAs were relatively lower than those of the tissue biopsy (Fig. 1E). One CNA (FGFR amplification) identified in the tumor tissue was not detected in the ctDNA.

Comprehensive review of the hormone status (ER positive) and genetic alteration (CDK4 amplification) status strongly suggested the use of CDK4/6 inhibitors such as palbociclib [5] combined with aromatase inhibitor [6]. However, due to her dismal hepatic function, palbociclib was not administered, and she passed away after 52 months of cancer recurrence. In this study, we showed an example that driver alterations identified in the tumor tissue were detected in liquid biopsy by targeted NGS as well. The low VAF of mutation and attenuated CNA signals in the liquid biopsy compared to the tissue biopsy suggest that a higher depth of sequencing coverage is required for detection of genomic alterations in a liquid biopsy than in a tissue biopsy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from National Research Foundation of Korea (2012R1A5A2047939 and NRF-2015R1C1A1A01051525).

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data including three tables and two figures can be found with this article online at http://www.genominfo.org/src/sm/gni-15-48-s001.pdf

A list of non-silent somatic mutations identified in a breast tumor by WES

A list of copy number alterations identified in a breast tumor by WES

Seventy-eight cancer genes for OncoChase cancer panel analysis

Disease status at the time of cancer recurrence. Bone scan shows multiple bone metastases involving spine, sacrum and rib (A). Chest computed tomography (CT) scan shows multiple lung metastases (B), and abdomen CT scan reveals liver metastasis (C).

Disease status at the time of whole exome sequencing for breast cancer. Progression of bone metastases involving whole spine, both femur shaft and pelvic bone was detected by bone scan (A). Chest computed tomography (CT) scan shows progressive lung metastases (B) and abdomen CT scan shows progression of liver metastases (C).

References

- 1.Swanton C. Intratumor heterogeneity: evolution through space and time. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4875–4882. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diaz LA, Jr, Bardelli A. Liquid biopsies: genotyping circulating tumor DNA. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:579–586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwaederle M, Husain H, Fanta PT, Piccioni DE, Kesari S, Schwab RB, et al. Use of liquid biopsies in clinical oncology: pilot experience in 168 patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:5497–5505. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jung SH, Kim MS, Lee SH, Park HC, Choi HJ, Maeng L, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies recurrent AKT1 mutations in sclerosing hemangioma of lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:10672–10677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606946113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Leary B, Finn RS, Turner NC. Treating cancer with selective CDK4/6 inhibitors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13:417–430. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finn RS, Martin M, Rugo HS, Jones S, Im SA, Gelmon K, et al. Palbociclib and letrozole in advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1925–1936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A list of non-silent somatic mutations identified in a breast tumor by WES

A list of copy number alterations identified in a breast tumor by WES

Seventy-eight cancer genes for OncoChase cancer panel analysis

Disease status at the time of cancer recurrence. Bone scan shows multiple bone metastases involving spine, sacrum and rib (A). Chest computed tomography (CT) scan shows multiple lung metastases (B), and abdomen CT scan reveals liver metastasis (C).

Disease status at the time of whole exome sequencing for breast cancer. Progression of bone metastases involving whole spine, both femur shaft and pelvic bone was detected by bone scan (A). Chest computed tomography (CT) scan shows progressive lung metastases (B) and abdomen CT scan shows progression of liver metastases (C).