Abstract

Yeast Sln1p is an osmotic stress sensor with histidine kinase activity. Modulation of Sln1 kinase activity in response to changes in the osmotic environment regulates the activity of the osmotic response mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and the activity of the Skn7p transcription factor, both important for adaptation to changing osmotic stress conditions. Many aspects of Sln1 function, such as how kinase activity is regulated to allow a rapid response to the continually changing osmotic environment, are not understood. To gain insight into Sln1p function, we conducted a two-hybrid screen to identify interactors. Mog1p, a protein that interacts with the yeast Ran1 homolog, Gsp1p, was identified in this screen. The interaction with Mog1p was characterized in vitro, and its importance was assessed in vivo. mog1 mutants exhibit defects in SLN1-SKN7 signal transduction and mislocalization of the Skn7p transcription factor. The requirement for Mog1p in normal localization of Skn7p to the nucleus does not fully account for the mog1-related defects in SLN1-SKN7 signal transduction, raising the possibility that Mog1p may play a role in Skn7 binding and activation of osmotic response genes.

Recent characterization of the osmotic response pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae has uncovered a complex pathway consisting of two signal transduction modules (48). The activity of the first module, a prototypical mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathway, is regulated by a second module known as a “two-component” phosphorelay that was first characterized in prokaryotes and has since been identified in fungi, slime molds, and plants (35, 58). Interestingly, two-component regulators have not been identified in higher eukaryotes other than plants. In S. cerevisiae, there is a single two-component type phosphorelay pathway in which the sensor-kinase, Sln1p, autophosphorylates a conserved histidine in response to an environmental stimulus. That phosphoryl group is then transferred to a conserved aspartate in the Sln1 receiver domain, and then to a histidine in the phosphorelay molecule, Ypd1p, and finally to an aspartate on the independent receiver domain of the response regulator, Ssk1p (37, 47, 48). The HOG1 MAP kinase pathway is kept in the inactive state under normal osmotic conditions by virtue of normal levels of Sln1p and thus Ssk1p phosphorylation, since activation of the Hog1p MEK kinase requires unphosphorylated Ssk1p (38, 48). Hypertonic conditions reduce Sln1p kinase activity, allowing Ssk1p to accumulate in the unphosphorylated form and triggering the activity of the HOG1 pathway. In contrast, hypotonic conditions stimulate Sln1p kinase and appear to cause hyperphosphorylation of the Ssk1p receiver, as well as of the second response regulator, Skn7p (59). Mutants lacking Sln1p, or the phosphorelay protein, Ypd1p, are inviable or very sick, depending on the strain background, in normal osmotic conditions. This is due to the accumulation of Ssk1p in the unphosphorylated form causing constitutive activation of the Hog1p MAP kinase. Mutations in SSK1 or HOG1 rescue the lethality of sln1Δ and ypd1Δ mutants, as does overexpression of the HOG1 phosphatase, PTP2 (46).

The SKN7 gene was identified in a number of genetic screens, including one for high-copy suppressors of a mutation in KRE9 affecting cell wall β-glucan assembly and another for increased sensitivity to oxidative stress (30). A third screen in which SKN7 was identified was for high-copy suppressors of the lethality associated with loss of the G1 transcription factors SBF and MBF (43). Finally, we identified SKN7 in a screen for high-copy activators of a SLN1-dependent reporter gene (33). The variety of screens in which SKN7 emerges presumably reflects the broad functional spectrum of genes that are regulated by this transcription factor-coupled response regulator. The various phenotypes of skn7 mutants can be divided into two categories based on whether the conserved phosphoaccepting aspartate (D427) in its receiver domain is required for complementation. The oxidative stress phenotype of skn7 mutants does not require D427, for example (33, 42), whereas suppression of a temperature-sensitive pkc1 mutant, a phenotype that probes the cell wall-related function of Skn7p, does require the presence of D427, as does the cell cycle-related function (43) and activation of SLN1-dependent reporters (2, 14).

Skn7p has an HSF-like helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domain and has been reported to bind to the upstream regulatory region of TRX2 (42), SSA1 (50), and OCH1 (34). Just distal to the DNA-binding domain of Skn7p is a coiled-coil (cc) domain involved in protein interactions. Skn7p has been shown to self-associate, as well as to interact with a number of proteins, including the stress transcription factors, Hsf1p (50) and Yap1p (42); the cell cycle transcription factor, Mbp1p (11, 43); and the calcium responsive transcription factor, Crz1p (64). An interaction with the Rho1 GTPase has also been reported (1). The coiled-coil region of Skn7p is presumed to be required for each of these interactions as its deletion eliminates complementation of nearly all tested phenotypes (1).

An important regulatory mechanism in many signal transduction pathways is the subcellular localization or compartmentalization of signaling molecules. For example, in the osmotic stress MAP kinase pathway, the MAP kinase, Hog1p, which is predominantly cytoplasmic in unstressed cells, rapidly accumulates in the nucleus in response to increased osmolarity (53). MAP kinases, including Hog1p, lack classical import signals, and nuclear accumulation of Hog1p depends on its phosphorylation by the cytoplasmic MEK, Pbs2 (21, 53), and the Ptp2 protein, which may serve as a nuclear anchor (41). Like Hog1p, the Msn2p and Msn4p transcription factors that are involved in HOG1-dependent and HOG1-independent stress responses become nuclear after exposure of cells to stress (23). Although Hog1p specifically localizes in response to osmotic stress, the Msn2 and Msn4 proteins become nuclear after a variety of stress treatments (23). Like Hog1p, Msn2p, and Msn4p possess no apparent nuclear localization signal (NLS). Rather, the presence of a 300-amino-acid (aa) domain was found to be crucial for cytoplasmic localization under nonstress conditions (23), suggesting a localization mechanism based on shuttling and cytoplasmic anchoring. The oxidative stress transcription factor Yap1p also moves to the nucleus in response to stress (31, 65). Cysteine residues in the C-terminal tail are required for the cytoplasmic localization of Yap1p in unstressed cells, and removal of the tail results in constitutive nuclear localization.

The subcellular localization of the yeast two-component proteins involved in osmotic stress has recently been investigated. Sln1p was found on the plasma membrane both before and after osmotic shock (36, 52). Ssk1p is cytoplasmic (36), and the Skn7p transcription factor is nuclear (12, 50). No changes in Skn7p localization have been observed in response to either oxidative or osmotic stress. Instead, the phosphorelay molecule Ypd1p shuttles in and out of the nucleus to phosphorylate the cytoplasmic response regulator, Ssk1p, and the nuclear response regulator, Skn7p, as needed (36).

Further insight into the localization and compartmentalization of two-component signal transduction molecules has emerged with our recent observation that the Mog1 protein, known to be involved in nucleocytoplasmic macromolecule transport in S. cerevisiae, interacts with molecules of the SLN1-SKN7 signal transduction pathway. In strains lacking MOG1 both NLS-dependent and NLS-independent protein import pathways are abolished at high temperature, although mRNA export is normal (45). MOG1 was initially identified in a screen for suppressors of a temperature-sensitive mutations in GSP1, which encodes a homolog of mammalian Ran (45), a Ras-like GTP-binding protein that, together with its nucleotide exchanger, RCC1, has been implicated in the control of protein movement into the nucleus and cytoplasmic accumulation of mRNA. Like its mammalian counterpart, Gsp1p cycles between the GTP and GDP bound forms as it shuttles between cytoplasm and nucleus. Hydrolysis of GTP is necessary for proper import of proteins into the nucleus and appearance of poly(A)+ RNA in the cytoplasm. Although the precise function of Mog1p in the Ran cycle is not yet known, it has been proposed that Mog1p is needed for maintaining the nuclear biased gradient of Gsp1p (57).

We show here that Mog1p physically interacts with Ypd1p and Skn7p, as well as Sln1p. In addition, strains lacking Mog1p have phenotypes that suggest defects in SLN1-SKN7 signal transduction. Based on the known function of Mog1p in nucleocytoplasmic transport, we propose a model in which Mog1p plays one role in moving Skn7p to the nucleus and a second role in ensuring Skn7p activation in response to stimulation of the SLN1 pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

Strains were isogenic derivatives of S288C or derivatives of Stratagene strain YPH499, which is derived from YNN216 and congenic with S288C. Complete genotypes are listed in Table 1. MOG1 and DJP1 open reading frames (ORFs) were disrupted by transformation of yeast with PCR products containing the HIS3 selectable marker flanked by homology to the gene to be disrupted. The mog1Δ::HIS3 fragment was amplified by using pRS313 as a template and forward primer MOG1-9F::pRS (5′-GGTTTGCATATGAAGATTGAAAAGGCTTCTCATATTTCACAActgtgcggtatttcacaccg; lowercase letters are pRS vector sequences) and reverse primer MOG1+607R::pRS (5′-GCAACAATTGGTAAACAGCATGACATCTTGCAGGCAACTCTTTagattgtactgagagtgcac). The djp1Δ::HIS3 fragment was amplified by using the forward primer DJP1−16F::pRS (5′-GCATTATACAAAAGATATGGTTGTTGATACTGAGTATTACGActgtgcggtatttcacaccg) and the reverse primer DJP1+1274R::pRS (5′-GCTTCTGCTACAAGTTCTTCAAAGATCTGTGCCTCTTCTTagattgtactgagagtgcac). The replacement was confirmed by genomic PCR and subsequent restriction analyses of the amplified fragments. Deletion of the MOG1 ORF in the S288C strain background did not have the previously reported temperature-sensitive phenotype (45). Since earlier studies showed that the temperature-sensitive phenotype of mog1 mutants is tightly associated with its nucleocytoplasmic transport defect (45), the MOG1 disruption was recreated in strain YPH499 (Stratagene) as previously reported (45). As expected, the MOG1 disruption in the YPH499 background was temperature sensitive for viability (Fig. 2).

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Straina | Relevant genotype | Derivation and/or source |

|---|---|---|

| PJ69-4A | MATatrp1-901 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3-200 gal4Δ gal80ΔLYS2::GAL1-HIS3 GAL2-ADE2 met2::GAL7-lacZ | 29 |

| YPH499 | MATaura3-52 lys2-801amber ade2-101ochre trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 | Stratagene |

| FY834 | MATα his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 ura3-52 trp1Δ63 lys2Δ201 | |

| JF2177 | MATα sln1Δ::KAN skn7Δ ypd1Δ ssk1Δ::LEU2 his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 ura3-52 trp1Δ63 lys2Δ201 canRcyhR | Sequential one-step replacements in FY834: (i) ssk1Δ::LEU2, (ii) ypd1Δ::KAN, (iii) skn7Δ::KAN, and (iv) sln1Δ::TRP1; the KAN markers were removed by galactose-induced cre-lox recombination; the TRP1 marker at SLN1 was replaced by using a trp1Δ::KAN cassette |

| JF2215 | MATamog1Δ::HIS3 ura3-52 lys2-801amber ade2-101ochre trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 | mog1Δ::HIS3 derivative of YPH499; one-step replacement |

| JF2216 | MATaskn7Δ::TRP1 ura3-52 lys2-801amber ade2-101ochre trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 | skn7Δ::TRP1 derivative of YPH499; one-step replacement |

| JF2224 | MATasln1-22 ura3-52 lys2-801amber ade2-101ochre trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 | sln1-22 derivative of YPH499; two-step replacement |

| JF2226 | MATamog1Δ::HIS3 skn7Δ::TRP1 ura3-52 lys2-801amber ade2-101ochre trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 | mog1Δ::HIS3 derivative of JF2216; one-step replacement |

| JF2227 | MATamog1Δ::HIS3 sln1-22 ura3-52 lys2-801amber ade2-101ochre trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 | mog1Δ::HIS3 derivative of JF2224; one-step replacement |

| JF2228 | MATaskn7Δ::KAN sln1-22 ura3-52 lys2-801amber ade2-101ochre trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 | skn7Δ::KAN derivative of JF2224; one-step replacement |

| JF2230 | MATamog1Δ::HIS3 skn7Δ::KAN sln1-22 ura3-52 lys2-801amber ade2-101ochre trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 | mog1Δ::HIS3 derivative of JF2228; one-step replacement |

| JF2297 | MATaMOG1::mycx2::KAN skn7Δ::TRP1 ura3-52 lys2-801amber ade2-101ochre trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 | MOG1::mycx2::KAN derivative of JF2216; one-step replacement |

All YPH499 derived strains used in this study are derived from YNN216, which is congenic with S288C.

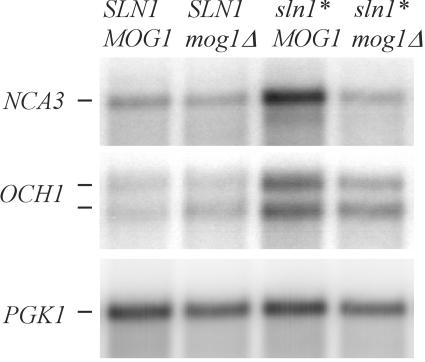

FIG. 2.

Northern hybridization analysis showing the effect of mog1Δ on sln1* activation of the SLN1-SKN7 target genes, NCA3 and OCH1. mRNA was prepared from log-phase cultures of SLN1+ MOG1+ (YPH499), SLN1+ mog1Δ (JF2215), sln1* MOG1+ (JF2224), and sln1* mog1 Δ (JF2227) strains. The PGK1 hybridization was performed as a loading control. The experiment was repeated four times. A representative blot is shown.

Integrative epitope tagging of MOG1 at the C terminus was achieved as described previously (18). The MOG1-6His-2myc-loxP-kanMX-loxP fragment was created by PCR with pU6H2MYC (generously provided by A. De Antoni) (18) as a template and the primers MOG1 (+610F) (5′-GAAATGGTACGGAAGTTTCACGTTGTGGACACGTCGCTGTTTGCTtcccaccaccatcatcatcac-3′) and MOG1 (+703R) (5′-GTAGAAATAAAAAGGTAATATAAACATAAGGTTAAAATTTGAAAGactatagggagaccggcagatc-3′) and used to transform yeast. Transformants representing the desired homologous recombination at the 3′ end of MOG1 were determined by genomic PCR and sequencing. The expression and size of the Mog1-mycx2 (2myc) protein was confirmed by anti-myc Western analysis. The C-terminally myc-tagged Mog1p was shown to be functional.

Media.

All media were prepared as described by Sherman et al. (54) and included synthetic complete medium (SC) lacking one or more specific amino acids (e.g., SC−histidine) and rich medium (yeast extract-peptone-dextrose [YPD]). The growth temperature for yeast culture was 28°C unless otherwise indicated. Yeast transformation was performed by a modified lithium acetate method (22, 28). Plasmids were recovered from yeast by using a Zymoprep Miniprep kit (Zymo Research).

Plating assays.

Log-phase cells were spotted onto various media after serial 10-fold dilutions. Osmotic stress sensitivity was tested on YPD plates containing 0.9 M NaCl or 1.5 M sorbitol. Responsiveness to oxidative stress was examined by growing yeast for 2 to 3 days on YPD medium containing 0.5 mM t-butyl-hydroperoxide (Sigma). Resistance to hygromycin B (Boehringer Mannheim) was tested at concentrations of 50 to 80 μg/ml in YPD medium. All drug sensitivity assays were carried out at 28°C.

Plasmids.

Plasmids used in the present study are summarized in Table 2. Their construction is summarized below.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Comments and source and/or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pJL1241 | Yeast two-hybrid candidate clone pFL64-411; Gal4 AD-MOG1 fusion | 29; this study |

| pJL1244 | Yeast two-hybrid candidate clone pFL99-12; Gal4 AD-DJP1 fusion | 29; this study |

| pAS1-CYH2 | Gal4 DBD-HA plasmid; 2μm TRP1 | 19 |

| pACTII | Gal4 AD-HA; 2μm LEU2 | 19 |

| pJL1243 | GST-MOG1 (aa 78 to 218) in pGEX-4T | pGEX-4T (Amersham-Pharmacia); this study |

| pJL1246 | GST-DJP1 (aa 65 to 432) in pGEX-4T | pGEX-4T (Amersham-Pharmacia); this study |

| pWT1111 | SLN1 (aa 356 to 1220) in pAS1-CYH2 | pAS1-CYH2 (19) |

| pWT1117 | SLN1 (aa 356 to 1220) in pACTII | pACTII (19) |

| pB931 | UASGAL1-SLN1 (aa 356 to 1220)-mycx6 in pRS314 | Cytoplasmic portion of Sln1p (60) |

| pB959 | UASGAL1-SLN1 (aa 537 to 1220)-mycx6 in pRS314 | Kinase and receiver domain of Sln1p (60) |

| pWT1224 | UASGAL1-SLN1(aa 356 to 1077)-mycx6 in pRS314 | Sln1p kinase lacking receiver domain (60) |

| pJL1286 | SLN1-receiver (aa 1068 to 1220) in pAS1-CYH2 | pAS1-CYH2 (19; this study) |

| pJL1298 | YPD1 ORF in pAS1-CYH2 | pAS1-CYH2 (19; this study) |

| pJL1306 | SSK1 receiver domain (aa 425 to 712) in pAS1-CYH2 | pAS1-CYH2 (19; this study) |

| pJL1290 | SKN7 (wild-type) ORF in pAS1-CYH2 | pAS1-CYH2 (19; this study) |

| pJL1292 | skn7 (D427E) ORF in pAS1-CYH2 | pAS1-CYH2 (19; this study) |

| pJL1294 | skn7 (D427N) ORF in pAS1-CYH2 | pAS1-CYH2 (19; this study) |

| pJL1296 | skn7 (ΔDBD aa 27 to 232) ORF in pAS1-CYH2 | pAS1-CYH2 (19; this study) |

| pJL1318 | MOG1 (−881 to +1086) in pRS315 | pRS315 (55; this study) |

| pJL1338 | MOG1 (−881 to +1086) in pRS425 | pRS425 (16; this study) |

| pJL1256 | MOG1 (−708 to +1086) in pRS423 | pRS425 (16; this study) |

| pSL232 | SKN7 in pRS315 | 33 |

| pCLM699 | skn7 D427N in pRS315 | 33 |

| pCLM700 | skn7 D427E in pRS315 | 33 |

| pSL236 | SKN7-HAx6 in pRS315 | pRS315 (55; this study) |

| pJL1363 | UASSKN7-GFP (S65T, F64L) in pRS425 | pRS425 (16; this study) |

| pJL1380 | GFP-SKN7 fusion in pRS425 | pRS425 (16; this study) |

| pJL1364 | GFP-SKN7 (aa 1 to 307) fusion in pRS425 | pRS425 (16; this study) |

| pJL1365 | GFP-SKN7 (aa 217 to 499) fusion in pRS425 | pRS425 (16; this study) |

| pJL1366 | GFP-SKN7 (aa 370 to 622) fusion in pRS425 | pRS425 (16; this study) |

| pJL1414 | UASYPD1-GFPx2-YPD1 fusion in pRS316 | 36 |

| pB701 | UASGPD1-GFP-RAS2 fusion in YEplac95 | 8 |

| pADA842 | pGEX-KG-SSK1 | 24, 33 |

| pADA841 | pGEX-KG-SKN7 | 24, 33 |

| pFJS42 | pET16b-Hisx10-SKN7 | Ann West, University of Oklahoma; pET16b (Novagen) |

| pHL581 | pGEX-KG-Sln1 kinase (aa 537 to 947) | 25, 60 |

| pADA689 | pGEX-KG-Sln1 receiver (R1) (aa 1068 to 1220) | 24, 33 |

| pCLM655 | pGEX-KG-YPD1 | 24, 33 |

| pJL1492 | pGEX-4T-MOG1 (full length) | pGEX-4T (Amersham-Pharmacia); this study |

| pU6H2MYC | C-terminal epitope-tagging plasmid with 6His-2MYC-loxP-kanMX-loxP module | 18 |

MOG1 plasmids.

pJL1318 (pRS315-MOG1) and pJL1338 (pRS425-MOG1) were constructed by PCR amplification of the MOG1 gene from genomic DNA with primer MOG1−881F (5′-GCTCTCTAGACTCATTCTTGCTGTGTCGT-3′) and MOG1+1086R (5′-CGAAGGATCCGAACTCTGAATATTGT-3′). The 1.9-kb PCR product was digested with XbaI and BamHI and inserted into the SpeI and BamHI sites in the polylinkers of pRS315 and pRS425, respectively. pJF1256 (pRS423-MOG1) was constructed by cloning a BamHI-XbaI-digested PCR fragment of MOG1 (positions −708 to +1086) into pRS423 between the BamHI and SpeI sites.

Plasmids for protein association analysis.

Hemagglutinin (HA) fusion constructs were created by using the UASADH1-Gal4 DBD-HA yeast two-hybrid vector, pAS1-CYH2 (19).

To construct the HA-YPD1 fusion the BamHI-SalI fragment of YPD1 was subcloned from the GST-YPD1 fusion construct pCLM655 (33) into pAS1-CYH2 to create pJL1298.

The HA-SKN7 fusions were constructed by cloning the BamHI-SalI double-digested PCR product amplified with the primers SKN7-1F (5′-GGGATCCCATATGAGCTTTTCCACCATAAA-3′) and SKN7+1882R (5′-GGGTTGTCGACGCAAGGCTATTTGTAAA-3′) and the plasmids pSL232, pCLM699, pCLM700 (33), and pSL1129 as templates into pAS1-CYH2 to create pJL1290 (wild-type D427), pJL1294 (D427N), and pJL1292 (D427E), and pJL1296 (ΔDBD; lacking aa 27 to 237), respectively. pJL1306 is a pAS1-CYH2 plasmid carrying a BamHI-HincII fragment (aa 425 to 712) from pSSK1223 (a gift of H. Saito) that includes the receiver domain of Ssk1p.

pJL1286 carries a fragment of SLN1 receiver domain (aa 1068 to 1220) inserted into EcoRI-BamHI-digested pAS1-CYH2.

Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusions of MOG1 and DJP1 were constructed by subcloning the EcoRI-SalI fragment of two-hybrid library clones containing MOG1 or DJP1 into pGEX-4T (Pharmacia). pJL1243 has a MOG1 insert (aa 78 to 218) derived from the library clone, pFL64-411, and pJL1244 has a DJP1 insert (aa 65 to 432) derived from the library clone, pFL99-12. For expressing full-length Mog1p in bacteria, MOG1 (+3 to +758) was PCR amplified, digested with BamHI and NotI, and cloned into pGEX-4T.

GFP fusion plasmids.

A 2μm green fluorescent protein (GFP)-SKN7 plasmid was constructed in three steps. Plasmid pSL268 (pRS425-SKN7) was modified to eliminate the polylinker between SpeI and HindIII, generating pJL1362. BamHI and HindIII sites were then engineered in pJL1362 just beyond the translation initiation site of SKN7, and SpeI and HindIII sites were engineered at the stop codon of the SKN7 ORF. Outward PCR with the primers SKN7+1870F (5′-GCGAAGCTTAGATCTTAATACTAGTAATTTTACAAATAGCCTTGC-3′)and SKN7+1R.HindIII-BamHI (5′-GCTAAGCTTGGATCCCATAGTGGATATCAAAAGTA-3′) generated a 9.2-kb PCR product that was then digested with HindIII and self-ligated to create the 2μm plasmid, pJL1361, in which the SKN7 ORF was replaced by a BamHI-SpeI-HindIII polylinker. A UASSKN7-GFP control plasmid, pJL1363, was obtained by cloning a 0.72-kb PCR-derived GFP (S65T, F64L) fragment into pJL1361 via HindIII and BglII sites.

The high-copy (2μm) GFP-SKN7 fusion construct, pJL1380, was generated by cloning a 1.9-kb PCR fragment containing the SKN7 ORF amplified with the primers SKN7-1F.BamHI-NdeI (5′-GGGATCCCATATGAGCTTTTCCACCATAAA-3′) and SKN7+1866R.HindIII-SpeI (5′-CGGAACTAGTGAAGCTTTGATAGCTGGTTTTCTTG-3′) into the BamHI and SpeI sites in pJL1363. Plasmids encoding GFP fusion with truncated Skn7 protein were constructed by fusing BamHI-SalI-digested PCR fragments of SKN7, including aa 1 to 307, aa 217 to 499, or aa 370 to 622 behind GFP in pJL1363 to create pJL1364, pJL1365, and pJL1366, respectively.

Two-hybrid screen and assay.

Two-hybrid analysis was performed in the yeast strain PJ69-4A according to the method of James et al. (29). pWT1111 contains the cytoplasmic portion of SLN1 (aa 356 to 1220) fused to the HA-tagged DNA-binding domain of pAS1-CYH2 (19, 60) and was used as the bait to screen an activation domain pGAD-C1 library (generously provided by Philip James) by cotransformation of PJ69-4A with pWT1111 and the pGAD library. His+ colonies were patched and replica plated onto medium containing 1 mM 3-aminotriazole (3-AT) and separately onto SC−Ade medium and medium containing 150 μg of X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside)/ml. Strong interactors were further tested on SC−His plates containing 3-AT at concentrations up to 25 mM. Plasmids rescued from Ade+, 3-ATR, X-Gal+ candidates were subjected to DNA sequencing to identify the insert.

Northern hybridization analysis.

Log-phase cultures grown at 27°C were harvested and stored at −80°C. RNA samples were extracted by using the hot acidic phenol method (4). mRNA was isolated by using the poly(A)+ RNA purification kit (Promega). One-tenth of each mRNA sample was loaded onto denaturing agarose gel (1.2%). Hybridization with [α-32P]dATP-labeled probes (Prime-It II Kit; Stratagene) was carried out in PerfectHyb solution (Sigma) at 68°C overnight. Quantitation was performed by phosphorimaging analysis. All bands were normalized to levels of PGK1.

Fluorescence microscopy.

Log-phase cultures expressing GFP fusions were fixed in 70% ethanol, washed and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and stained with 0.1 μg of DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Sigma)/ml to visualize nuclei. Cells were observed with a Leica DM RBE microscope and a Leica ×100 PL Fluotar 1.3 NA objective lens. Fluorescence images were captured by using a Photonic Science digital charge-coupled device camera system. Images were processed by using IP-LAB Spectrum software and edited in Adobe Photoshop.

Protein extraction and Western analysis.

Strains were grown in selective medium with 2% glucose or in 2% raffinose. For galactose induction, 4% galactose was added to log-phase cultures for 3 h. Cell pellets were washed in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)-50 mM EDTA and then in coimmunoprecipitation buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 10 mM MgCl2, 140 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, plus protease inhibitors) prior to storage at −80οC. Cells were disrupted by vortexing in the presence of 425- to 600-μm glass beads (Sigma). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation and stored at −20°C. Protein concentrations were determined by Bio-Rad Microassay. Expression of the test proteins were examined by immunoblot analysis with specific primary antibodies, followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-immunoglobulin G secondary antibody. Immune complexes were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Corp.).

Expression and purification of GST-tagged MOG1 and DJP1 fusion proteins.

Cultures (0.6 liter) of Escherichia coli BL21-DE3-STAR (Invitrogen) containing GST fusion plasmids were induced with 0.2 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 3 h. Cell pellets were store at −80°C and subsequently resuspended in 30 ml of buffer B (33, 48) containing 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors. After sonication and centrifugation, lysates were incubated with 3 to 4 ml of washed 50% glutathione-Sepharose slurry (Amersham) at 4°C for 5 to 12 h. Beads were removed by centrifugation, washed three times in 20 ml of buffer B, washed twice in 10 ml of buffer C (33, 48), resuspended in 5 ml of buffer C, and stored at −20°C. Purified proteins were visualized by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on gels stained with Coomassie blue.

In vitro protein coprecipitation assay.

A total of 0.2 to 0.5 mg of total yeast protein was added to 0.5 ml of ice-cold protein-binding buffer (coimmunoprecipitation buffer with 1% bovine serum albumin), and aggregates were removed by centrifugation. Bead-bound GST fusion proteins were added, and the binding reactions were rocked on ice for 4 to 12 h. Beads were washed twice in ice-cold PBS, twice in coimmunoprecipitation buffer, three times in PBS-0.1% Tween 20, and three times in PBS-0.2% Tween 20, with 5-min room temperature incubations between each wash. Samples were then resuspended in loading sample buffer (32), boiled, and separated on SDS-12% PAGE gels. Prior to immunoblot analysis, proteins were visualized by Ponceau S (Sigma) staining to ensure the presence of similar amounts of GST fusions.

Phosphotransfer assays.

Protein expression and glutathione affinity purification for Sln1-HK, Sln1-R1, Ypd1p, and Skn7p were performed as described previously (3, 33). When necessary, GST fusion proteins were solubilized by elution with glutathione or by thrombin cleavage and then dialyzed in storage buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 30% glycerol). Full-length His10-Skn7 protein was purified by using a His-Bind purification kit (Novagen). Phosphotransfer assays were performed as described previously (33, 48) by filtration-based separation of bead-bound phosphorylated phospho-donor from soluble phosphorylated phospho-acceptor. The purified, soluble, phosphorylated phospho-acceptor was then used as the donor in examining downstream phosphorelay reactions. To examine the effect of Mog1p on phosphotransfer steps, Mog1p was purified from bead-bound GST-Mog1p by thrombin cleavage. In each transfer step Mog1p was mixed with radiolabeled phospho-donor prior to the addition of unphosphorylated acceptor. In reactions lacking Mog1p, storage buffer was added to the same volume. Aliquots were removed from the phosphotransfer reactions at indicated time points. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and radiolabeled protein species were visualized by phosphorimaging analysis.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

Preparation of yeast protein extracts and the mobility shift assay were carried out as described previously (34) with minor modifications. Binding reactions consisted of 5 μg of yeast protein extract, 1 μg of poly(dI-dC) (Boehringer Mannheim), and 0.5 to 1 ng (5 to 20 counts per minute) of probe in electrophoretic mobility shift assay buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 50 mM NaCl, 7 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mg of CHAPS {3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate}/ml). Reactions were incubated at 25°C for 20 min before electrophoresis in 4% polyacrylamide gel in cool 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (45 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 44.5 mM boric acid) at 200 V for 2 to 3 h. In supershift assays, binding reactions were subsequently incubated with antibody for 30 min and complexes were resolved by electrophoresis. Electrophoretic mobility shift experiments were routinely repeated four to six times with extract sets prepared on different days. Representative gels are shown.

RESULTS

Identification of MOG1 and DJP1 in a two-hybrid screen for Sln1p-interacting proteins.

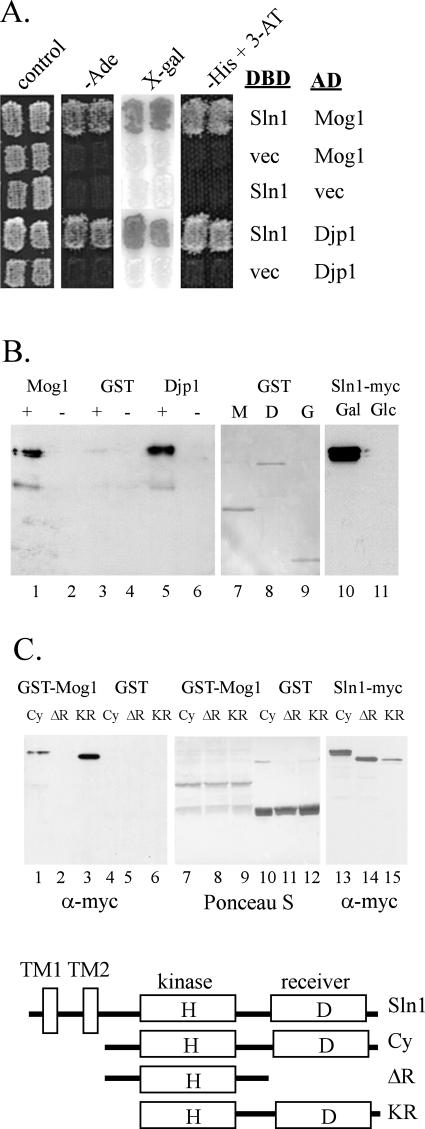

In an effort to identify proteins that regulate Sln1p activity, a yeast two-hybrid screen was conducted by using the cytoplasmic portion of SLN1 as bait. SLN1 (aa 356 to 1220) was cloned behind the Gal4 DBD-HA cassette in the pAS1-CYH2 bait vector (29) and introduced into yeast strain PJ69-4A, together with a pGAD-C1 prey plasmid library (19). Interactors were selected on the basis of GAL4-dependent reporter gene expression. Three clones showed a strong interaction based on survival under stringent selection for expression of the GAL4-dependent HIS3 reporter on plates containing 25 mM 3-AT. Each clone was also positive for interaction with the GAL4-dependent ADE2 and lacZ-based reporters (Fig. 1A). Sequence analyses showed that one clone (pFL64-411) contained a 1.8-kb insert, including the MOG1 ORF (aa 78 to 217) and downstream 3′-untranslated region, and two clones (pFL99-12 and pFL107-21) contained a region of the DJP1 ORF (aa 65 to 431) but included different lengths of downstream sequence. Mog1p is involved in nuclear protein import (45), and Djp1p is a cytoplasmic protein involved in protein import into peroxisomes (26). To confirm the interactions, MOG1 and DJP1 were subcloned into GST vectors and the resulting GST-fusions expressed and purified from bacteria by using glutathione beads. Bead-bound Mog1p or Djp1p was incubated with yeast extracts prepared from cultures expressing myc-tagged cytoplasmic Sln1p under the control of the GAL1 promoter (Fig. 1B, lanes 10 and 11). The presence or absence of Sln1p among the proteins associated with the beads was detected by using anti-myc antibody. Sln1p association with Mog1p and Djp1p was detected in reactions involving extracts prepared from galactose-grown cells and therefore expressing Sln1p (Fig. 1B, lanes 1 and 5). The interaction with Mog1p required the receiver domain (aa 1077 to 1220) of Sln1p (Fig. 1C, lanes 1 to 3). GST-Mog1 interacted with a cytoplasmic Sln1p derivative lacking the two N-terminal transmembrane domains [Sln1(Cy): aa 356 to 1220] and with the kinase-plus-receiver domains of Sln1p [Sln1(KR): aa 537 to 1220] but not with a derivative containing the kinase domain but lacking the receiver domain of Sln1p [Sln1(ΔR): aa 356 to 1077].

FIG. 1.

Interaction between Sln1p and Mog1p or Djp1p. (A) Yeast two-hybrid assay in which strain PJ69-4A carrying ADE2, HIS3, and lacZ reporters were cotransformed with DNA-binding domain (DBD) and activation domain (AD) plasmids as indicated. Two independent transformants are shown on an SC control plate and on three different test plates: −Ade, SC−adenine; X-gal, SC + 75 μg of X-Gal/ml; −His + 3-AT, SC−histidine with 10 mM 3-AT added. (B) In vitro association assay in which bacterially expressed GST-Mog1p and GST-Djp1p proteins were incubated with yeast extracts prepared from cells expressing a GAL-driven myc-tagged Sln1p. Lanes: +, galactose grown; −, glucose grown. Lanes 1 to 6; bead-bound complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE, and Sln1 protein was detected by using a α-myc antibody. In lanes7 to 9, Ponceau S staining shows the levels of GST-Mog1p (M), GST-Djp1p (D), and GST (G) in each reaction. Lanes 10 to 11 show the galactose-inducible expression of Sln1p. (C) Localization of the Mog1p-interacting domain of Sln1p. Lanes: Cy, cytoplasmic Sln1p (pB931, aa 356 to 1220); ΔR, cytoplasmic Sln1p lacking the receiver domain (pWT1224, aa 356 to 1077); KR, kinase plus receiver domain (pB959, aa 537 to 1220). In vitro association assays were carried out as in panel B. Lanes 7 to 12 show Ponceau S staining of the blot, showing the bead-bound GST-Mog1 and GST proteins in each of the pull-down reactions in lanes 1 to 6. Lanes 13 to 15 show the level of each myc-tagged SLN1 construct in the extracts. A schematic of the SLN1 constructs used is shown at the bottom. TM, transmembrane domains; H, kinase domain histidine 576; D, receiver domain aspartate 1144.

Deletion of MOG1 diminishes SLN1-SKN7 pathway activity.

The SLN1-SKN7 pathway regulates the expression of target genes including OCH1, a gene encoding an α-1,6-mannosyl-transferase involved in N glycosylation (34), and NCA3, a member of the “SUN” family of proteins whose products appear to have dual cell wall and mitochondrial functions and localization (62). Levels of OCH1 and NCA3 expression are increased by the sln1* mutation that activates the SLN1-SKN7 pathway (Fig. 2), and the increase is dependent on the phospho-accepting aspartate, D427 of SKN7 (34). To determine whether MOG1 or DJP1 play a role in modulating SLN1-SKN7 pathway signaling, sln1* activation of NCA3 and OCH1 was examined in mog1Δ and djp1Δ strains. As expected, NCA3 and OCH1 levels were increased three- to fivefold by the sln1* activating mutation in MOG1+ strains (Fig. 2). In the absence of MOG1, however, activation of NCA3 by sln1* was eliminated. The sln1*/SLN1+ ratio was 4.97 in a MOG1+ strain and 1.38 in the mog1Δ strain. Activation of OCH1 by sln1* was also reduced, with the sln1*/SLN1+ ratio going from 3.46 in the MOG1+ strain to 2.45 in the mog1Δ strain. Although less dramatic a change than for NCA3, this difference in OCH1 levels due to the absence of MOG1 is reproducible and statistically significant (Student t test; P = 0.004; t = 4.4). The difference in magnitude of the effect on NCA3 versus OCH1 may reflect differences in the Skn7p binding site in the two genes. The effects of mog1 deletion on NCA3 and OCH1 expression in a sln1* strain (but not in the SLN1+ strain, Fig. 2) suggest that SLN1-SKN7 pathway activation depends on MOG1. In contrast to the effect of a mog1 deletion, deletion of DJP1 had no effect on sln1* activation (data not shown). The absence of an effect of the djp1 deletion on SLN1-SKN7-dependent pathway activity was taken to indicate that the Djp1p interaction with Sln1p was unlikely to be physiologically meaningful and DJP1 was not pursued further.

We previously found that resistance to hygromycin B depends on SLN1-SKN7 pathway activity (34) (Fig. 3). Hygromycin B is an aminoglycoside antibiotic that inhibits the growth of many yeast mutants with defects in N glycosylation (17) and has been used to probe cell wall integrity in cell wall mutants (7, 10, 63). As a test of the relevance of MOG1 to the SLN1-SKN7 pathway, we examined the effect of mog1Δ on hygromycin resistance. As shown in Fig. 3, deletion of MOG1 caused sensitivity to hygromycin B at 28°C. These results are consistent with an involvement of Mog1p in SLN1-SKN7 signal transduction. Another skn7 mutant phenotype, sensitivity to oxidative stress (30), is not mimicked in the mog1 mutant. Growth of the mog1Δ strain on 0.5 mM t-butyl-hydroperoxide was comparable to the growth of an isogenic wild-type strain on the same medium (Fig. 3). Since the oxidative stress phenotype of skn7 mutants reflects the role of Skn7p in a SLN1-independent pathway, these results suggest that Mog1p specifically affects the SLN1-SKN7 pathway and not Skn7p function in general.

FIG. 3.

Phenotypic analysis of the mog1 mutant. Log-phase cultures were serially diluted and spotted onto various media. YPD, YPD plates; t-BOOH, YPD with 0.5 mM t-butyl-hydroperoxide added; Hyg-B, YPD with 50 μg of hygromycin B added/ml. Plates were incubated up to 36 h at the indicated temperatures.

Mog1p associates with Skn7p and Ypd1p in vitro.

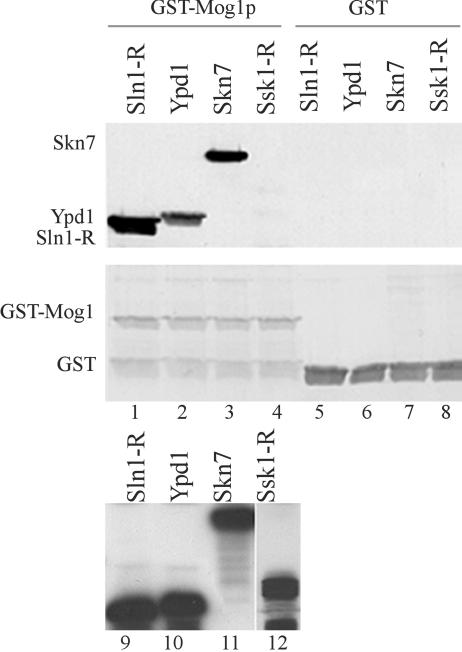

Given the nuclear localization of Mog1p (57), and the similarity between the receiver domains of Sln1p and Skn7p, we sought to determine whether Mog1p might also interact with Skn7p. Yeast protein extracts prepared from cultures expressing an HA-tagged Skn7p or HA-tagged Ypd1 fusion protein were separately incubated with bacterially expressed GST-Mog1 (aa 78 to 217) fusion protein in the presence of glutathione-Sepharose beads. The bead-bound protein complex was fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and anti-HA antibody was used to detect the presence or absence of Skn7p and Ypd1p in the complexes. Figure 4 (lanes 3 and 7) shows that Skn7 protein was associated with the bead-bound GST-Mog1 protein but not with the GST protein. In contrast, an interaction between GST-Mog1p and Ssk1p, another response regulator with a receiver domain could not be detected after normal exposure times (Fig. 4, lanes 4 and 8). Hence, the interactions between Mog1p and the components of the SLN1-SKN7 pathway reflect a specific role of Mog1p in SLN1-SKN7 signal transduction rather than a nonspecific association of Mog1p with two-component type proteins.

FIG. 4.

In vitro association assay of Mog1p with Skn7p, Ypd1p, and Ssk1p. (Upper panel) Bead-bound GST-Mog1p fusion protein (left) or GST alone (right) was incubated with yeast extracts prepared from the quadruple deletion sln1Δ ypd1Δ skn7Δ ssk1Δ strain, JF2177, containing HA-tagged Sln1R (receiver domain) (pJL1286), Skn7p (pJL1290), Ypdp (pFJ1298), or Ssk1R (receiver domain) (pJF1306). Complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the association of HA-tagged Sln1p, Ypd1p, and Skn7p with bead-bound GST-Mog1p or with GST was detected by α-HA antibody probing. The positions of HA-tagged Skn7p, Ypd1p, and Sln1R are shown to the left. (Middle panel) Ponceau S staining of the blot shown above. The positions of GST-Mog1p and GST are indicated. (Lower panel) Detection of the HA-tagged proteins in the extracts by α-HA Western analysis.

An interaction with the phospohrelay molecule Ypd1p, which does not have a receiver domain, was also detected (Fig. 4, lanes 2 and 6). The interaction between Mog1p and Ypd1p does not require other components of the pathway. In Fig. 4, extracts used to test the Mog1p-Ypd1p interaction were prepared from strains lacking Skn7p, Sln1p, and Ssk1p. In these and other tests we found no dependence of the Mog1p interactions on other components of the SLN1 pathway. These data suggest that Mog1p is capable of separate interactions with each protein of the SLN1-SKN7 pathway.

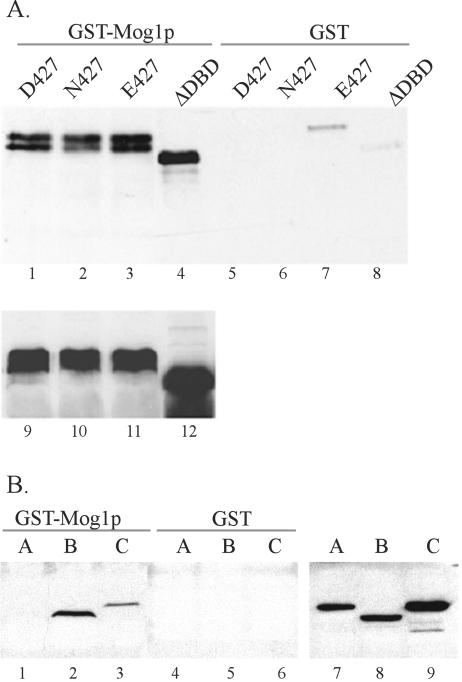

To gain further insight into the basis of the Mog1p interaction with Skn7p, we examined the features of Skn7p required for the interaction. Western analysis confirmed that each Skn7p derivative was expressed at equivalent levels (Fig. 5A, lanes 9 to 12, and B, lanes 7 to 9). The interaction between Mog1p and Skn7p does not require the DNA-binding domain of Skn7p (Fig. 5A, lane 4). The Mog1p-Skn7p interaction also showed no detectable dependence on Skn7 aspartyl phosphorylation. A Skn7p derivative in which aspartate D427 was mutated to asparagine (D427N), thus rendering the Skn7 receiver domain unable to accept a phosphoryl group from upstream SLN1 pathway components, interacted as well with Mog1p as did wild-type Skn7p (Fig. 5A, lanes 1 and 2). Likewise, the D427E derivative of SKN7, which results in constitutive activation of SLN1-SKN7 targets, did not alter the interaction with Mog1p (Fig. 5A, lanes 1 and 3). To localize the domain of Skn7p required for the interaction, derivatives of Skn7, expressing the N terminus, the middle, or the C terminus of the protein and fused to GFP, were used in coprecipitation assays with GST-Mog1p. The construct consisting of the “middle” of Skn7p (including the CC and receiver domains) interacted most strongly with Mog1p (Fig. 5B), whereas the N-terminal construct (including the DBD and CC domains) did not interact at all. A weak interaction was detected with the C-terminal construct (including the receiver and glutamine-rich domains). These data indicate that the Mog1p interaction with Skn7p requires the receiver domain and may be enhanced by the presence of the coiled-coil domain.

FIG. 5.

Mog1p interaction with Skn7p is D427 independent and localizes to the receiver domain. Coprecipitations were performed with extracts prepared from a skn7Δ strain (JF2216) carrying plasmids with HA-tagged alleles of SKN7 (D427, pJL1290; D427N, pJL1294; D427E, pJL1292; and ΔDBD, pJL1296) (panel A) or carrying plasmids encoding N-terminal GFP fusions to portions of SKN7 (panel B). In panel B, extracts in lane A contain a GFP fusion to the SKN7 DNA binding and cc domains (aa 1 to 307), pJL1364; extracts in lane B contain a GFP fusion to SKN7 cc and receiver domains (aa 217 to 499), pJL1365; and extracts in lane C contain a GFP fusion to SKN7 receiver and glutamine-rich domains (aa 370 to 622), pJL1366. Extracts were combined with recombinant GST-Mog1p (pJL1492) (lanes 1 to 4 in panel A and lanes 1 to 3 in panel B), GST alone (lanes 5 to 8 in panel A and lanes 4 to 6 in panel B), or nothing (lanes 9 to 12 in panel A and lanes 7 to 9 in panel B). The abundance of Skn7 protein in each extract was examined by Western blotting analysis with α-HA (panel A) or α-GFP (panel B) antibody.

Mog1p is required for localization of Skn7p to the nucleus.

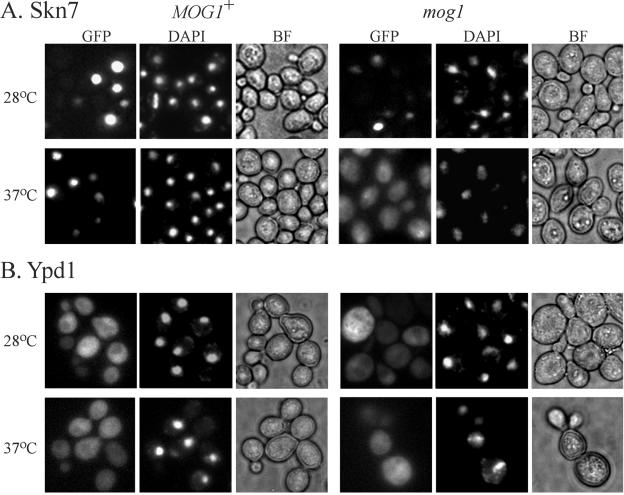

Mog1p is involved in nucleocytoplasmic transport. Strains lacking MOG1 are defective in both NLS-dependent and NLS-independent nuclear import of proteins (45). Interestingly, this defect is manifested exclusively at elevated temperatures (45). We therefore tested whether the nuclear localization of Ypd1p or Skn7p required Mog1p. Functional SKN7-GFP and YPD1-GFP fusion constructs were introduced into MOG1+ and mog1Δ strains. Localization was examined at 28°C and at times after a shift to 37°C. Skn7p-GFP was nuclear at both low and high temperatures in the MOG1+ strain (Fig. 6A). Incubation of the mog1 mutant at the elevated temperature, however, caused a change in the nuclear localization of Skn7p. After 1 h at 37°C, cells could be detected in which Skn7p-GFP was distributed throughout the cytoplasm, as well as the nucleus (Fig. 6A). In contrast, the normal localization of Ypd1p-GFP in both the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments (36) was not detectably altered by the mog1 mutation (Fig. 6B). These results reveal a requirement for functional Mog1 protein in Skn7p nuclear import. Since, as expected (45), there were no detectable localization defects at 28°C, the hygromycin sensitivity and SLN1-SKN7 signaling defects in the mog1 mutant at this temperature must reflect a Mog1p function in SLN1-SKN7 signal transduction that is distinct from its role in protein trafficking.

FIG. 6.

Fluorescence microscopy showing Skn7-GFP in MOG1 and mog1Δ strains at 28 and 37°C. Cultures of MOG1+ (left) and mog1Δ (right) strains expressing GFP-Skn7p (pJL1380) or GFP-Ypd1p (pJF1414) were maintained at 28°C or shifted to 37°C for 3 h prior to examination. Each GFP image is accompanied by corresponding DAPI (center) and bright-field (BF) (right) images.

Ypd1p-Skn7p interaction and the SLN1 phosphorelay are independent of Mog1p.

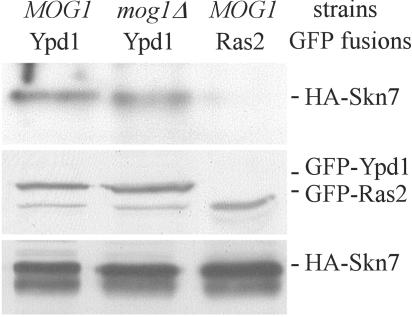

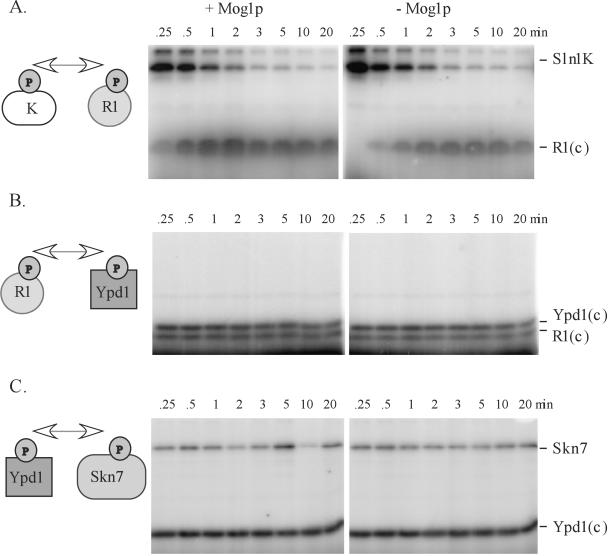

The novel role for Mog1p in SLN1-SKN7 signal transduction suggested by phenotypes in the mog1 mutant such as hygromycin sensitivity and reduced expression of SLN1-SKN7 target genes could take any number of forms. The possibility that Mog1p facilitates the physical association between Ypd1p and Skn7p was tested by using a coimmunoprecipitation assay. GFP-Ypd1p associated proteins were immunoprecipitated from MOG1+ and mog1Δ extracts expressing Skn7-HA. The absence of Mog1p appeared to have no effect on Skn7p association with Ypd1p (Fig. 7). A possible contribution of Mog1p to Sln1p-, Ypd1p-, and Skn7p-dependent phosphotransfer steps was also investigated. The efficiency of each phosphotransfer reaction was evaluated in the presence or absence of bacterially purified Mog1p. The presence of Mog1p in the reaction appeared to have subtle effects on the Sln1 kinase to Sln1 receiver phosphotransfer, slightly increasing the rate of receiver domain phosphorylation (Fig. 8A) . Although reproducible, this and other modest effects seen in vitro may or may not occur in vivo and seem unlikely to account for the mog1Δ phenotypes.

FIG. 7.

Skn7p interaction with Ypd1p is not affected by Mog1p. (Top) Extracts from MOG1+ (JF2216) and mog1Δ strains (JF2226) carrying plasmid pSL236, which expresses HA-tagged SKN7, and pJF1414, which expresses GFP-Ypd1p, or pB701, which expresses GFP-Ras2 (negative control), were subjected to immunoprecipitation with α-GFP antibody. The presence or absence of associated Skn7p was examined by using α-HA-based Western analysis of SDS-polyacrylamide gels. In the panels below, levels of GFP-Ypd1p and Skn7-HA proteins in the MOG1+ and mog1Δ were detected by α-GFP and α-HA Western analysis.

FIG. 8.

Phosphotransfer steps in the SLN1-SKN7 pathway are largely independent of Mog1p. Phosphotransfer reactions were performed in vitro and in the presence or absence of bacterially purified Mog1 protein as described in Materials and Methods. The effect of Mog1p on three steps—phosphotransfer between Sln1 kinase (K) and Sln1 receiver (R1) (A), phosphotransfer between Sln1 receiver (R1) and Ypd1p (B), and phosphotransfer between Ypd1p and Skn7p (C)—was examined. Representative gels are shown. The diagram on the left shows the phosphotransfer step tested in each experiment. Phosphorylated species are labeled at right. The “(c)” indicates that the purification tag was cleaved prior to analysis. Time points were 15 and 30 s and 1, 2, 3, 5, 10, and 20 min after mixing of the labeled component with the unlabeled component.

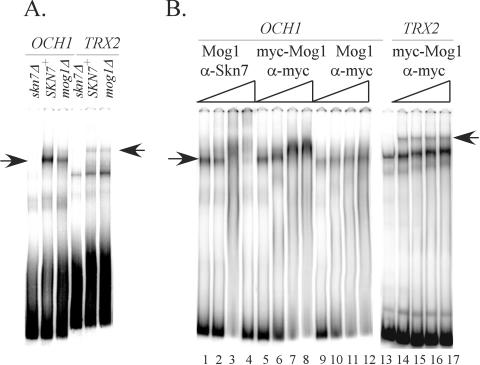

Mog1p facilitates Skn7p association with SLN1-SKN7 pathway target gene promoters.

Finally, we evaluated potential effects of Mog1p on binding of the Skn7p transcription factor to DNA. Skn7p binding to the promoter of the SLN1-SKN7 pathway target, OCH1, and to the promoter of the Skn7p-dependent oxidative stress response gene, TRX2, has been well characterized (33, 34, 42). Gel shift assays were performed with MOG1+ SKN7 and mog1Δ SKN7 extracts and well-characterized fragments containing Skn7p binding sites from the OCH1 or TRX2 promoters. Since oxidative stress resistance (Fig. 3) was unaffected in the mog1Δ mutant, the TRX2 fragment was included as a negative control. The absence of Mog1p caused a reduction in Skn7p binding to the OCH1 promoter (mog1Δ/MOG1 = 0.57, n = 11) but had no effect on binding to the TRX2 promoter (mog1Δ/MOG1 = 1.01, n = 10) (Fig. 9A). Antibody supershift assays were performed to examine the possibility that Mog1p is associated with the Skn7p-DNA complex. Extracts prepared from strains carrying a functional MOG1-myc allele were used in DNA-binding reactions with OCH1 or TRX2 promoter fragments and an increasing concentration of α-myc antibody (Fig. 9B). α-Skn7p antibody was used in parallel as a control. The addition of increasing concentration of Skn7p antibody caused the OCH1 complex to migrate progressively slower (Fig. 9B, lanes 1 to 4) (34). A supershift of the OCH1-Skn7p complex was also observed with α-myc antibody (Fig. 9B, lanes 5 to 8), suggesting that Mog1p is present in the complex. Identical concentrations of α-myc antibody failed to cause such a shift in control reactions involving extracts prepared from untagged Mog1p (Fig. 9B, lanes 9 to 12) and also had no effect on the complex of Skn7p with the TRX2 promoter (Fig. 9B, lanes 13 to 17). These studies suggest that Mog1p is specifically associated with Skn7p on SLN1-regulated, SKN7-dependent promoters and that one role of the Mog1 protein is in facilitating Skn7p association with the promoters of osmotic stress target genes.

FIG. 9.

Effect of Mog1p on Skn7p-DNA interaction. (A) Extracts were prepared from skn7Δ MOG1 (JF2216) carrying a SKN7 plasmid (pSL232) (SKN7+) or the empty vector, pRS315 (skn7Δ), and skn7Δ mog1Δ (JF2226) carrying the SKN7 plasmid, pSL232 (mog1Δ). Binding reactions consisted of 5 μg of extract and labeled DNA from the OCH1 promoter (coordinates −355 to −135) or TRX2 promoter (coordinates −399 to −160). Complexes were separated by gel electrophoresis and visualized by phosphorimaging analysis. Arrows indicate Skn7-dependent complexes. (B) Extracts were prepared from skn7Δ strains in which the genomic MOG1 locus was tagged with mycx2 epitope (myc-Mog1) (JF2297) or was untagged (Mog1) (JF2216) and into which the SKN7 plasmid, pSL232 (lanes 1 to 12 and 14 to 17) or empty vector, pRS315 (lane 13), was introduced. Increasing concentrations (0, 1, 2, and 4 μg) of α-Skn7 (gift of L. Johnston) or α-myc antibody (9E10) were added to the binding reactions. Electrophoretic mobility shift experiments were repeated 10 times with extracts prepared on different days. A representative gel is shown.

DISCUSSION

The Mog1 protein was found to interact with components of the SLN1-SKN7 signal transduction pathway, including the receiver domains of the two-component histidine kinase, Sln1p, the transcription factor, Skn7p, as well as an undefined domain of the phosphorelay protein, Ypd1p. Evidence for the physiological relevance of these interactions is described. Mog1p was originally identified as a suppressor of certain temperature-sensitive alleles of yeast Ran (Gsp1p) and found to associate with nucleotide-bound, as well as nucleotide-free forms of Gsp1p (5, 45). Analysis of a mog1Δ strain demonstrated that Mog1p is required for nuclear import in vivo (45). Our studies reveal a novel function for Mog1p in regulating the stress activated transcription factor, Skn7p.

That the role of Mog1p in regulating Skn7p activity is separate from its known role in nucleocytoplasmic transport is supported by the observation that the mog1Δ mutant exhibits defects in Skn7p signaling even at temperatures permissive for localization. Strains lacking MOG1 exhibit a temperature-dependent defect in NLS-dependent and NLS-independent protein import pathways (45). The function of Mog1p in protein localization is essential at the elevated temperature since the mog1 deletion mutant is also temperature sensitive for growth. The synthetic lethality of a mog1 prp20-1 double mutant at the permissive temperature (5) suggests that Mog1p may have overlapping functions with the yeast Ran guanine nucleotide exchange factor, Prp20p.

Since both NLS-dependent and NLS-independent nuclear localization are impaired in mog1 deletions at high temperatures, the mislocalization of Skn7p at the elevated temperature was expected. What was surprising was that, despite the absence of detectable localization defects at the permissive temperature, the mog1 deletion strain nonetheless exhibited a reduction in activation of SLN1-SKN7 target genes and a hygromycin-sensitive phenotype similar to that seen in skn7 mutants. These are the first reports of mog1Δ phenotypes at the permissive temperature.

The Mog1p interaction with Gsp1p requires amino acids 30 to 70 on the Mog1p surface. These residues are conserved in all Mog1p homologs, and mutations of Asp62 and Glu65 cause defects in nuclear protein import (6, 56). Since the Mog1p fusion recovered in our two-hybrid screen started at amino acid 78, the interactions between Mog1p and components of the SLN1-SKN7 pathway appear to require a distinct surface of Mog1p. The separate interactions of Mog1p with the nuclear transport machinery and with proteins such as Skn7p that might constitute cargo are consistent with a direct role for Mog1p in nuclear localization.

Since the interaction between Mog1p and each protein that might potentially be in a SLN1-SKN7 signalosome was independent of each of the others, it is clear that Mog1p is capable of separately, if not simultaneously, interacting with each protein. In this respect, Mog1p appears to share some features with scaffold proteins, such as Ste5p and Pbs2p, which associate physically with various components of the pheromone and osmotic response MAP kinase pathways, respectively (15, 39, 49). Like other scaffolds, Mog1p associates with a membrane-associated sensor (Sln1p), as well as with downstream components that regulate the activity of effectors (20). Furthermore, the proposal that the Ste5p scaffold facilitates phosphorylation (20) provides a paradigm for thinking about potential roles for Mog1p in stimulating SLN1-SKN7 pathway activity.

The mog1 defects reported here reflect a specific role of Mog1p in SLN1-SKN7 signal transduction, as opposed to a more general role for Mog1p in all aspects of SLN1 signal transduction. The observation that mog1 mutants are not salt sensitive (J. M.-Y. Lu and J. S. Fassler, unpublished results) indicates that SLN1-HOG1 signaling is intact. Likewise, the absence of an oxidative-stress-sensitive phenotype in the mog1 mutant (Fig. 3) is consistent with the conclusion that Mog1p is not needed for Skn7p activation of oxidative stress response genes. Whether Mog1p has a special relationship with molecules in the SLN1-SKN7 pathway or whether it might function in additional signal transduction pathways whose activities have not been assayed here remains an open question.

In conclusion, Mog1p is required for optimal binding of Skn7p to the promoter of the SLN1-SKN7-dependent target gene OCH1. Moreover, antibody supershift experiments show that Mog1p is part of the Skn7p-OCH1 complex. Interestingly, the mobility of Skn7p complexes was not influenced by the presence or absence of Mog1p, perhaps due to the small size of the Mog1 protein. Examples of DNA-associated proteins whose absence causes no detectable change in the mobility of a complex have been reported (9).

The presence of Mog1p in the Skn7p complex is unlikely to be a reflection of intrinsic DNA-binding activity in Mog1p. The Mog1 protein bears no detectable similarity to known DNA-binding domains, nor have we detected complexes consisting of Mog1p alone in gel shift assays. More likely is that Mog1p association with Skn7p is a reflection of the involvement of Mog1p in a coactivator complex involved in recruitment of RNA polymerase and the general transcriptional machinery. This model is consistent with the growing body of evidence for connections between translocation machinery and regulation of transcription (13, 27).

Our observations of Mog1p function in the SLN1-SKN7 osmotic stress signal transduction pathway in S. cerevisiae provides a new perspective for understanding the global activities of the Mog1 protein in yeast and, given the ubiquitous presence of Mog1p homologs in eukaryotes ranging from yeast to humans (40, 44, 61), in other organisms as well. Prior reports of a specific interaction between the Ran binding protein, RanBPM with the androgen receptor/transcription factor (51) bears some similarity to our findings of a Mog1p-Skn7p interaction. We speculate that Ran binding proteins such as RanBPM and Mog1 may constitute a new class of bifunctional proteins with roles in nucleocytoplasmic transport, as well as in the recruitment of transcription factors to specific promoters.

Acknowledgments

We thank present and former members of our lab for discussions, reagents, and experimental assistance. In particular, we appreciate the technical efforts of Greg Gingerich and Leena Vig. We also thank Fabiola Janiak-Spens and Ann West (University of Oklahoma) for bacterial strains and constructs, as well as valuable advice in protein purification and phosphotransfer assay. We thank Takehara Nishimoto (Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan) for providing a mog1Δ strain, Anna De Antoni (European Institute of Oncology) for providing plasmids for integrative epitope tagging, and Lee Johnston and coworkers (National Institute for Medical Research, London, United Kingdom) for generously providing the α-Skn7 antibody.

This study was supported by grant GM56719 from the National Institutes of Health and an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship to J.M.-Y.L.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alberts, A. S., N. Bouquin, L. H. Johnston, and R. Treisman. 1998. Analysis of RhoA-binding proteins reveals an interaction domain conserved in heterotrimeric G protein beta subunits and the yeast response regulator protein Skn7. J. Biol. Chem. 273:8616-8622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alex, L. A., C. Korch, C. P. Selitrennikoff, and M. I. Simon. 1998. COS1, a two-component histidine kinase that is involved in hyphal development in the opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7069-7073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ault, A. D., J. S. Fassler, and R. J. Deschenes. 2002. Altered phosphotransfer in an activated mutant of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae two-component osmosensor Sln1p. Eukaryot. Cell 1:174-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. E. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1989. Current protocols in molecular biology, vol. 1. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 5.Baker, R. P., M. T. Harreman, J. F. Eccleston, A. H. Corbett, and M. Stewart. 2001. Interaction between Ran and Mog1 is required for efficient nuclear protein import. J. Biol. Chem. 276:41255-41262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker, R. P., and M. Stewart. 2000. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ran-binding protein Mog1p. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 56(Pt. 2):229-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ballou, L., R. A. Hitzeman, M. S. Lewis, and C. E. Ballou. 1991. Vanadate-resistant yeast mutants are defective in protein glycosylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:3209-3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartels, D. J., D. A. Mitchell, X. Dong, and R. J. Deschenes. 1999. Erf2, a novel gene product that affects the localization and palmitoylation of Ras2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:6775-6787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bender, A., and G. F. Sprague. 1987. MATα1 protein, a yeast transcription activator, binds synergistically with a second protein to a set of cell type-specific genes. Cell 50:681-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benghezal, M., P. N. Lipke, and A. Conzelmann. 1995. Identification of six complementation classes involved in the biosynthesis of glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 130:1333-1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouquin, N., A. L. Johnson, B. A. Morgan, and L. H. Johnston. 1999. Association of the cell cycle transcription factor Mbp1 with the Skn7 response regulator in budding yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 10:3389-3400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown, J. L., H. Bussey, and R. C. Stewart. 1994. Yeast Skn7p functions in a eukaryotic two-component regulatory pathway. EMBO J. 13:5186-5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casolari, J. M., C. R. Brown, S. Komili, J. West, H. Hieronymus, and P. A. Silver. 2004. Genome-wide localization of the nuclear transport machinery couples transcriptional status and nuclear organization. Cell 117:427-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang, C., and E. M. Meyerowitz. 1994. Eukaryotes have “two-component” signal transducers. Res. Microbiol. 145:481-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi, K. Y., B. Satterberg, D. M. Lyons, and E. A. Elion. 1994. Ste5 tethers multiple protein kinases in the MAP kinase cascade required for mating in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell 78:499-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christianson, T. W., R. S. Sikorski, M. Dante, J. H. Shero, and P. Hieter. 1992. Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene 110:119-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dean, N. 1995. Yeast glycosylation mutants are sensitive to aminoglycosides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1287-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Antoni, A., and D. Gallwitz. 2000. A novel multi-purpose cassette for repeated integrative epitope tagging of genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 246:179-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durfee, T., K. Becherer, P.-L. Chen, S.-H. Yeh, Y. Yang, A. E. Kilburn, W. H. Lee, and S. J. Elledge. 1993. The retinoblastoma protein associates with the protein phosphatase type 1 catalytic subunit. Genes Dev. 7:555-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elion, E. A. 2001. The Ste5p scaffold. J. Cell Sci. 114:3967-3978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrigno, P., F. Posas, D. Koepp, H. Saito, and P. A. Silver. 1998. Regulated nucleo/cytoplasmic exchange of HOG1 MAPK requires the importin beta homologs NMD5 and XPO1. EMBO J. 17:5606-5614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gietz, R. D., and R. A. Woods. 2002. Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol. 350:87-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorner, W., E. Durchschlag, M. T. Martinez-Pastor, F. Estruch, G. Ammerer, B. Hamilton, H. Ruis, and C. Schuller. 1998. Nuclear localization of the C2H2 zinc finger protein Msn2p is regulated by stress and protein kinase A activity. Genes Dev. 12:586-597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guan, K., R. J. Deschenes, H. Qiu, and J. E. Dixon. 1991. Cloning and expression of a yeast protein tyrosine phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 266:12964-12970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guan, K., and J. E. Dixon. 1991. Eukaryotic proteins expressed in Escherichia coli: an improved thrombin cleavage and purification procedure of fusion proteins with glutathione S-transferase. Anal. Biochem. 192:262-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hettema, E. H., C. C. Ruigrok, M. G. Koerkamp, M. van den Berg, H. F. Tabak, B. Distel, and I. Braakman. 1998. The cytosolic DnaJ-like protein Djp1p is involved specifically in peroxisomal protein import. J. Cell Biol. 142:421-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hieronymus, H., and P. A. Silver. 2003. Genome-wide analysis of RNA-protein interactions illustrates specificity of the mRNA export machinery. Nat. Genet. 33:155-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ito, H., Y. Fukuda, K. Murata, and A. Kimura. 1983. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J. Bacteriol. 153:163-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.James, P., J. Halladay, and E. A. Craig. 1996. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics 144:1425-1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krems, B., C. Charizanis, and K.-D. Entian. 1996. The response regulator-like protein Pos9/Skn7 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is involved in oxidative stress resistance. Curr. Genet. 29:327-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuge, S., N. Jones, and A. Nomoto. 1997. Regulation of yAP-1 nuclear localization in response to oxidative stress. EMBO J. 16:1710-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, S., A. Ault, C. L. Malone, D. Raitt, S. Dean, L. H. Johnston, R. J. Deschenes, and J. S. Fassler. 1998. The yeast histidine protein kinase, Sln1p, mediates phosphotransfer to two response regulators, Ssk1p and Skn7p. EMBO J. 17:6952-6962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li, S., S. Dean, Z. Li, J. Horecka, R. J. Deschenes, and J. S. Fassler. 2002. The eukaryotic two-component histidine kinase Sln1p regulates OCH1 via the transcription factor, Skn7p. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:412-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loomis, W. F., G. Shaulsky, and N. Wang. 1997. Histidine kinases in signal transduction pathways of eukaryotes. J. Cell Sci. 110:1141-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu, J. M., R. J. Deschenes, and J. S. Fassler. 2003. Saccharomyces cerevisiae histidine phosphotransferase Ypd1p shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm for SLN1-dependent phosphorylation of Ssk1p and Skn7p. Eukaryot. Cell 2:1304-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maeda, T., M. Takekawa, and H. Saito. 1995. Activation of Yeast PBS2 MAPKK by MAPKKKs or by binding of an SH3-containing osmosensor. Science 269:554-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maeda, T., S. Wurgler-Murphy, and H. Saito. 1994. A two-component system that regulates an osmosensing MAP kinase cascade in yeast. Nature 369:242-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marcus, S., A. Polverino, M. Barr, and M. Wigler. 1994. Complexes between STE5 and components of the pheromone-responsive mitogen-activated protein kinase module. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:7762-7766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marfatia, K. A., M. T. Harreman, P. Fanara, P. M. Vertino, and A. H. Corbett. 2001. Identification and characterization of the human MOG1 gene. Gene 266:45-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mattison, C. P., and I. M. Ota. 2000. Two protein tyrosine phosphatases, Ptp2 and Ptp3, modulate the subcellular localization of the Hog1 MAP kinase in yeast. Genes Dev. 14:1229-1235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morgan, B. A., G. R. Banks, W. M. Toone, D. Raitt, S. Kuge, and L. H. Johnston. 1997. The Skn7 response regulator controls gene expression in the oxidative stress response of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 16:1035-1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morgan, B. A., N. Bouquin, G. F. Merrill, and L. H. Johnston. 1995. A yeast transcription factor bypassing the requirement for SBF and DSC1/MBF in budding yeast has homology to bacterial signal transduction proteins. EMBO J. 14:5679-5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nicolas, F. J., W. J. Moore, C. Zhang, and P. R. Clarke. 2001. XMog1, a nuclear Ran-binding protein in Xenopus, is a functional homologue of Schizosaccharomyces pombe Mog1p that co-operates with RanBP1 to control generation of Ran-GTP. J. Cell Sci. 114:3013-3023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oki, M., and T. Nishimoto. 1998. A protein required for nuclear-protein import, Mog1p, directly interacts with GTP-Gsp1p, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ran homologue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:15388-15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ota, I. M., and A. Varshavsky. 1992. A gene encoding a putative tyrosine phosphatase suppresses lethality of an N-end rule dependent mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:2355-2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Posas, F., and H. Saito. 1998. Activation of the yeast SSK2 MAP kinase kinase kinase by the SSK1 two-component response regulator. EMBO J. 17:1385-1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Posas, F., S. M. Wurgler-Murphy, T. Maeda, E. A. Witten, T. C. Thai, and H. Saito. 1996. Yeast Hog1 MAP kinase cascade is regulated by a multistep phosphorelay mechanism in the Sln1-Ypd1-Ssk1 “two component” osmosensor. Cell 86:865-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Printen, J. A., and G. F. Sprague, Jr. 1994. Protein-protein interactions in the yeast pheromone response pathway: Ste5p interacts with all members of the MAP kinase cascade. Genetics 138:609-619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raitt, D. C., A. L. Johnson, A. M. Erkine, K. Makino, B. Morgan, D. S. Gross, and L. H. Johnston. 2000. The Skn7 response regulator of Saccharomyces cerevisiae interacts with Hsf1 in vivo and is required for the induction of heat shock genes by oxidative stress. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:2335-2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rao, M. A., H. Cheng, A. N. Quayle, H. Nishitani, C. C. Nelson, and P. S. Rennie. 2002. RanBPM, a nuclear protein that interacts with and regulates transcriptional activity of androgen receptor and glucocorticoid receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 277:48020-48027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reiser, V., D. C. Raitt, and H. Saito. 2003. Yeast osmosensor Sln1 and plant cytokinin receptor Cre1 respond to changes in turgor pressure. J. Cell Biol. 161:1035-1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reiser, V., H. Ruis, and G. Ammerer. 1999. Kinase activity-dependent nuclear export opposes stress-induced nuclear accumulation and retention of Hog1 mitogen-activated protein kinase in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 10:1147-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sherman, F., G. R. Fink, and J. B. Hicks. 1986. Methods in yeast genetics, p. 163-167. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 55.Sikorski, R. S., and P. Hieter. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122:19-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stewart, M., and R. P. Baker. 2000. 1.9 Å resolution crystal structure of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ran-binding protein Mog1p. J. Mol. Biol. 299:213-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stochaj, U., R. Rassadi, and J. Chiu. 2000. Stress-mediated inhibition of the classical nuclear protein import pathway and nuclear accumulation of the small GTPase Gsp1p. FASEB J. 14:2130-2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swanson, R. V., L. A. Alex, and M. I. Simon. 1994. Histidine and aspartate phosphorylation: two-component systems and the limits of homology. Trends Biochem. Sci. 19:485-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tao, W., R. J. Deschenes, and J. S. Fassler. 1999. Intracellular glycerol levels modulate the activity of Sln1, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae two-component regulator. J. Biol. Chem. 274:360-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tao, W., C. L. Malone, A. D. Ault, R. J. Deschenes, and J. S. Fassler. 2002. A cytoplasmic coiled-coil domain is required for histidine kinase activity of the yeast osmosensor, SLN1. Mol. Microbiol. 43:459-473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tatebayashi, K., T. Tani, and H. Ikeda. 2001. Fission yeast Mog1p homologue, which interacts with the small GTPase Ran, is required for mitosis-to-interphase transition and poly(A)+ RNA metabolism. Genetics 157:1513-1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Velours, G., C. Boucheron, S. Manon, and N. Camougrand. 2002. Dual cell wall/mitochondria localization of the ‘SUN’ family proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 207:165-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Warit, S., N. Zhang, A. Short, R. M. Walmsley, S. G. Oliver, and L. I. Stateva. 2000. Glycosylation deficiency phenotypes resulting from depletion of GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase in two yeast species. Mol. Microbiol. 36:1156-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Williams, K. E., and M. S. Cyert. 2001. The eukaryotic response regulator Skn7p regulates calcineurin signaling through stabilization of Crz1p. EMBO J. 20:3473-3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yan, C., L. H. Lee, and L. I. Davis. 1998. Crm1p mediates regulated nuclear export of a yeast AP-1-like transcription factor. EMBO J. 17:7416-7429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]