Abstract

Gross chromosomal rearrangements (GCRs) are frequently observed in cancer cells. Abnormalities in different DNA metabolism including DNA replication, cell cycle checkpoints, chromatin remodeling, telomere maintenance, and DNA recombination and repair cause GCRs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Recently, we used genome-wide screening to identify several genes the deletion of which increases GCRs in S. cerevisiae. Elg1, which was discovered during this screening, functions in DNA replication by participating in an alternative replication factor complex. Here we further characterize the GCR suppression mechanisms observed in the elg1Δ mutant strain in conjunction with the telomere maintenance role of Elg1. The elg1Δ mutation enhanced spontaneous DNA damage and resulted in GCR formation. However, DNA damage due to inactivation of Elg1 activates the intra-S checkpoints, which suppress further GCR formation. The intra-S checkpoints activated by the elg1Δ mutation also suppress GCR formation in strains defective in the DNA replication checkpoint. Lastly, the elg1Δ mutation increases telomere size independently of other previously known telomere maintenance proteins such as the telomerase inhibitor Pif1 or the telomere size regulator Rif1. The increase in telomere length caused by the elg1Δ mutation was suppressed by a defect in the DNA replication checkpoint, which suggests that DNA replication surveillance by Dpb11-Mec1/Tel1-Dun1 also has an important role in telomere length regulation.

Different types of genomic instabilities have been observed in many cancers (16, 20, 44). High levels of chromosome rearrangements known as gross chromosomal rearrangements (GCRs), such as translocations, deletion of a chromosome arm, interstitial deletions, inversions, and gene amplification, have been reported in many different cancers (25, 34). Such a high level of GCRs, which is one of the mutator phenotypes, leads to further accumulation of genetic changes in carcinogenesis (22).

A number of cancer susceptibility syndromes are due to inherited mutations in genes for DNA damage responses and DNA recombination-repair, and genetic defects resulting in higher frequencies of spontaneous and/or DNA damage-induced chromosome aberrations have been documented (1, 6, 9, 15, 36, 41, 43, 48). Some examples include ATM/ATR in ataxia-telangiectasia; Mre11 in the ataxia-telangiectasia-like disorder; Nbs1 in the Nijmegen breakage syndrome; hChk2 in the Li-Fraumeni syndrome; and Blm, Wrn, and Rts in the Bloom, Werner, and Rothmund-Thomson syndromes, respectively.

A number of studies have suggested that spontaneous GCRs result from errors during DNA replication that possibly lead to stalled or broken replication forks (21, 24, 28, 30, 35, 38, 46, 50). Besides errors during DNA replication, degradation of telomeres caused by abnormal regulation of telomere maintenance can produce alternative sources of DNA damage that can be converted to GCRs (4, 16, 26). Although normal levels of DNA damage activate cell cycle checkpoints and consequently DNA repair pathways (23), high levels of DNA damage or defects in cell cycle checkpoints and/or DNA repair induce GCR formation (16).

In order to understand the mechanisms of GCR suppression, quantitative assays that can measure different GCR events were developed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (8, 11, 28). At least six different pathways have been identified for the suppression of GCRs by using these assays: (i) at least three different cell cycle checkpoints during DNA replication, including the DNA replication checkpoint and two intra-S checkpoints (11, 21, 28, 30, 42); (ii) a recombination pathway known as break-induced replication (26); (iii) pathways that suppress de novo telomere addition (26); (iv) at least two pathways for proper chromatin assembly (31); (v) pathways that prevent chromosome ends from being joined to each other and to broken DNAs (7, 26, 33); and (vi) a mismatch repair pathway that prevents recombination between divergent DNA sequences (27).

Recently, we developed a new genome-wide screening method to identify more GCR suppressor genes and found 10 new genes (39). One of the new GCR suppressor genes, ELG1, encodes a protein that is a component of an alternative replication factor complex (RFC) (2, 3, 12, 14, 39). Elg1 was first identified as a suppressor of Ty1 transposon mobility in the yeast genome (37). Recent extensive genome-wide screens also identified ELG1 as an important gene for different DNA metabolism (2, 3, 12, 14, 39). In addition, the importance of Elg1 in DNA replication is strongly suggested by physical interactions between Elg1 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen, an accessory clamp protein for DNA polymerase, or Rad27, a flap endonuclease that removes the RNA primer from the lagging strand during DNA replication (14). The elg1Δ mutation has been shown to cause a cell cycle delay, presumably because of a high level of DNA damage during replication and increased sister chromatid exchange (14). This is similar to the sgs1Δ mutant strain, which has a mutation in the yeast Bloom-Werner gene homolog. Furthermore, Elg1 may have some interaction with cell cycle checkpoints on the basis of observations such as the abnormal activation of yeast Chk2 kinase Rad53 in the elg1 mutant strain upon methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) treatment and the slow S-phase progression of the elg1 mutant strain (2, 14). Mutation of the ELG1 gene also increases telomere length (14, 40). These studies suggest that a defect in the ELG1 gene causes more spontaneous DNA damage, presumably because of a partial deficiency in DNA replication and/or defects in other types of DNA metabolism.

In this report, we further characterize how the elg1Δ mutation increases GCRs and subsequent suppression pathways that repair spontaneous DNA damage generated by Elg1 deficiency. We demonstrate that the elg1Δ mutation enhances DNA damage, which activates the intra-S checkpoint for suppression of further GCR formation. In addition, we show that the telomere length increase caused by the elg1Δ mutation can be suppressed by the DNA replication checkpoint deficiency, suggesting a new role for the DNA replication checkpoint in telomere maintenance. It also has close links with mechanisms of GCR suppression by different cell cycle checkpoints.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General genetic methods.

Media used for propagation of strains were as previously described (28, 39). All of the S. cerevisiae strains used were propagated at 30°C, except for strains containing the dpb11-1 mutation, which were propagated at 25°C. Yeast transformation, isolation of yeast chromosomal DNAs for use as templates in PCRs, and PCRs were performed as previously described (28, 39).

Strains.

The strains used in this study for the general GCR assay were all isogenic to RDKY3615 (MATa ura3-52 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 lys2-Bgl hom3-10 ade2Δ1 ade8 hxt13::URA3), and those used for the HO-inducible GCR assay were all isogenic to RDKY4624 (MATa ura3::KAN HO::hisG leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 lys2-Bgl hom3-10 ade2Δ1 ade8 sit1::HO-URA3). All strains were generated by standard PCR-based gene disruption methods, and correct gene disruptions were verified by PCR assay as described previously (28, 45). The sequences of the primers used to generate disruption cassettes and to confirm the disruption of indicated genes are available upon request. The elg1Δ sgs1Δ and elg1Δ mre11Δ mutant strains showed a severe growth defect as previously described (14). The detailed genotypes of the strains used are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

S. cerevisiae strains used in this studya

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Plasmid | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKY3615 | Wild type | 8 | |

| RDKY3617 | rfa1-t33 | 8 | |

| RDKY3630 | rad27::KAN | 8 | |

| RDKY3633 | mre11::HIS3 | 8 | |

| RDKY3723 | rad24::HIS3 | 28 | |

| RDKY3731 | tel::HIS3 | 28 | |

| RDKY3735 | sml1::KAN mec1::HIS3 | 28 | |

| RDKY3739 | dun1::HIS3 | 28 | |

| RDKY3745 | chk1::HIS3 | 28 | |

| RDKY3749 | sml1::KAN rad53::HIS3 | 28 | |

| RDKY3813 | sgs1::HIS3 | 27 | |

| RDKY4348 | est2::TRP1 | 26 | |

| RDKY4361 | rif1::HIS3 | 26 | |

| RDKY4538 | dpb11-1 | 28 | |

| RDKY4753 | cac1::TRP1 | 31 | |

| RDKY4756 | asf1::HIS3 | 31 | |

| YKJM21 | srs2::KAN | This study | |

| YKJM245 | yku70::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM1405 | elg1::HIS3 | 39 | |

| YKJM1590 | sml1::KAN mec1::HIS3 elg1::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM1592 | elg1::HIS3 cac1::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM1594 | elg1::HIS3 est2::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM1596 | elg1::HIS3 mre11::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM1607 | tel1::HIS3 elg1::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM1667 | elg1::HIS3 srs2::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM1673 | elg1::HIS3 yku70::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM1675 | rfa1-t33 elg1::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM1677 | rad27::KAN elg1::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM1811 | sgs1::HIS3 elg1::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM1869 | chk1::HIS3 elg1::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM1868 | rad24::HIS3 elg1::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM1872 | elg1::HIS3 dun1::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM1874 | sml1::KAN rad53::HIS3 elg1::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM1889 | rif1::HIS3 elg1::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM1892 | dpb11-1 elg1::HIS3 | This study | |

| YKJM2197 | asf1::HIS3 elg1::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM2529 | dpb11-1 rad24::HYG elg1::TRP1 | This study | |

| YKJM2527 | elg1::HIS3 dun1::TRP1 rad24::HYG | This study | |

| HO assay | |||

| YKJM1659 | Wild type | pRS315 | This study |

| YKJM1661 | Wild type | pRDK899 | This study |

| YKJM1656 | elg1::HIS3 | pRS315 | This study |

| YKJM1657 | elg1::HIS3 | pRDK899 | This study |

All strains are isogenic to RDKY3615 (ura3-52 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 lys2ΔBgl hom3-10 ade2Δ1 ade8 hxt13::URA3) or YKJM1659 (ura3::KAN leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 lys2ΔBgl hom3-10 ade2Δ1 ade8 HO::hisG sit1::URA- HO) for a general GCR assay or an HO-inducible GCR assay respectively except for the mutations and plasmids described. pRDK899 encodes an HO endonuclease under the control of a galactose-inducible promoter.

Characterization of GCR rates and breakpoints.

All GCR rates were determined independently by fluctuation analysis by the method of the median with at least two independent clones by two or more times with either 5 or 11 cultures for each clone, and the average value is reported as previously described (17, 28). The breakpoint spectra from mutants carrying independent rearrangements were determined and classified as previously described (28, 39). The significance of differences between GCR rates was tested with the Mann-Whitney test by using programs available at http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/vshome.html.

Induction of GCRs by generation of a single DSB or MMS treatment.

GCR assays after the induction of a single double-strand break (DSB) by HO endonuclease or after treatment with MMS were performed as previously described (29, 30). Briefly, for the HO-inducible GCR assay, S. cerevisiae cells were cultured in synthetic dropout medium lacking amino acids required for selection of the plasmids that contain a galactose-inducible HO endonuclease gene until a cell density of 1 × 107 to 2 × 107/ml was obtained. Cells were then washed twice with distilled water and incubated further for 5 h in an equal volume of yeast extract-peptone (YP) medium containing 2% (wt/vol) glycerol and 1% succinic acid. Freshly made 50% galactose was then added to a final concentration of 2% to induce HO endonuclease expression, and cells were incubated for 2 h. Cells were washed twice with distilled water and suspended in 10 volumes of YP medium containing 2% glucose (YPD) and incubated overnight until the culture reached saturation. The cells were then plated onto YPD plates and FC plates containing both 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA; U.S. Biological) and canavanine (Sigma). The frequency of cells resistant to both drugs was determined. Three to five independent cultures of each strain were used in each experiment, and each experiment was performed at least twice. The average increase in the frequency of GCRs relative to the frequency of wild-type cells carrying control plasmids is reported. For the GCR assay after MMS treatment, log-phase cells were washed twice with distilled water and suspended in a volume of 0.1% MMS (Sigma) equal to the starting culture volume. After 2 h of incubation, the treated cells were washed with distilled water two times and suspended in 10 times the original volume of YPD. After overnight culture at 30°C until saturation, the cells were plated onto YPD plates and FC plates to determine the frequency of GCRs in the same way as in the HO-inducible GCR assay. The average increase in the frequency of GCRs relative to the GCR frequency of untreated cells was reported.

Telomere size determination.

Telomere size was determined by a conventional XhoI digestion and Southern hybridization method using a telomeric TG repeat as a probe to detect the Y′ class of telomeres. Chromosomal DNA from each strain was digested with XhoI (New England Biolabs) and separated by 0.7% agarose gel electrophoresis. Fragmented and denatured chromosomal DNAs were then transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane by a capillary transfer method and UV cross-linked with the Strata-linker. The 32P-labeled telomeric TG repeat obtained from pBC6 by a random priming method was used for hybridization with chromosomal DNAs on nitrocellulose as previously described (18). After 2 h of hybridization in ExpressHyb hybridization solution (BD Bioscience), the nitrocellulose filter was washed stringently and signals were detected with X-ray film (Kodak).

RESULTS

Previously, we identified 10 new GCR suppressor genes by a genome-wide screen in S. cerevisiae (39). ELG1, which encodes a protein participating in an alternative RFC with Rfc2-5 during DNA replication, was identified as a GCR suppressor during this and other screens (12, 39). Recent studies have suggested that mutations in ELG1 increase spontaneous DNA damage during DNA replication (2, 3, 14). In order to understand what causes GCR formation in the elg1Δ strain and what suppression mechanisms inhibit further GCR formation in the absence of Elg1, we investigated the GCR formation responses of the elg1Δ strain upon exogenous DNA damage and genetic interactions between the elg1Δ mutation and mutations in other GCR suppressor genes.

Extra DNA damage in the elg1Δ strain significantly increased GCRs.

Recent observations suggest enhanced unrepaired DNA damage in the elg1Δ mutation, including a high frequency of crossing over, chromosome loss, sister chromatid recombination, and enhanced recombination at direct DNA repeats (3, 14). However, the elg1Δ mutation increased the GCR rate 49-fold compared to that of the wild type (Table 2). It is slightly lower compared to that of strains carrying other GCR mutator genes that function in DNA replication or checkpoints (29, 30).

TABLE 2.

Effect of elg1Δ on the rate of accumulating GCRs in different cell cycle checkpoint-defective strainsa

| Relevant genotype | Wild type

|

elg1Δ

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | GCR rate 1010 (Canr 5-FOAr) | Strain | GCR rate 1010 (Canr 5-FOAr) | |

| Wild type | RDKY3615 | 3.5 (1) | YKJM1405 | 173 (49) |

| dpb11-1 | RDKY4538 | 450 (128) | YKJM1892 | 260 (74) |

| rad24Δ | RDKY3760 | 40 (11) | YKJM1868 | 733 (209) |

| sgs1Δ | RDKY3813 | 77 (22) | YKJM1811 | 434 (124) |

| mre11Δ | RDKY3633 | 2,200 (629) | YKJM1596 | 6,579 (1879) |

| mec1 Δ sml1Δ | RDKY3735 | 680 (194) | YKJM1590 | 1,960 (560) |

| tel1Δ | RDKY3731 | 2.0 (0.6) | YKJM1607 | 154 (44) |

| rad53Δ | RDKY3749 | 95 (27) | YKJM1874 | 1,830 (522) |

| chk1Δ | RDKY3745 | 130 (37) | YKJM1855 | 513 (147) |

| dun1Δ | RDKY3739 | 420 (120) | YKJM1872 | 141 (40) |

All strains are isogenic with wild-type strain RDKY3615 (ura3-52 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 lys2ΔBgl hom3-10 ade2Δ1 ade8 hxt13::URA3) with the exception of the indicated mutations. The values in parentheses are GCR induction relative to the wild-type GCR rate.

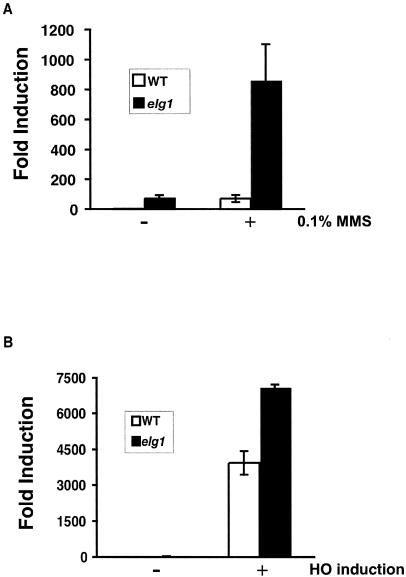

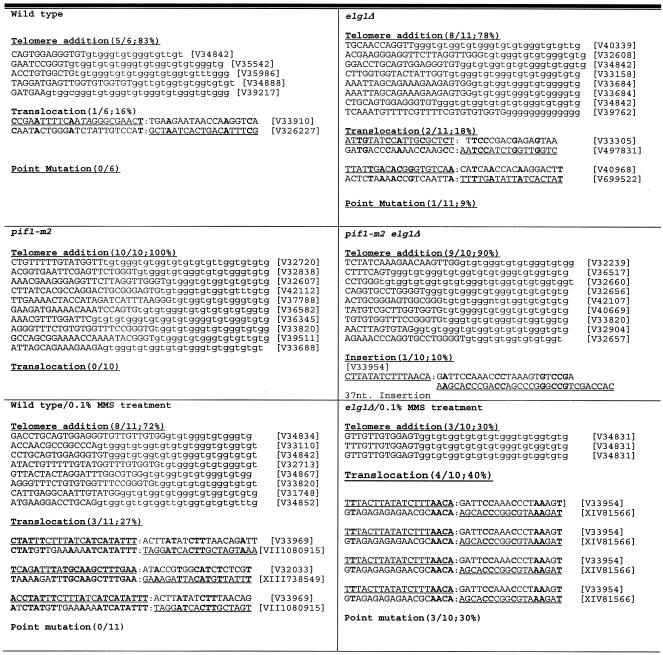

If this increase in the GCR rate caused by the elg1Δ mutation were due to suppression by DNA damage checkpoints, further DNA damage caused by treatment with DNA-damaging agents could potentially saturate DNA damage checkpoints and increase GCR formation synergistically. To test this hypothesis, the elg1Δ mutant strain was treated with 0.1% MMS and its induction of an increase in the GCR frequency was determined (Fig. 1A). The DNA damage caused by MMS treatment in the elg1Δ mutant strain increased the GCR frequency strikingly more than in the wild type. A similar increase in the GCR frequency upon MMS treatment was also observed when a single DSB was introduced in chromosome V as further DNA damage in the middle of two negative selection markers in the GCR assay (Fig. 1B). MMS treatment did not change breakpoint spectra compared to spontaneously generated GCRs. However, a single DSB introduction by a HO endonuclease increased the interstitial deletion class of GCR formation (Fig. 2). Such breakpoint spectra after MMS treatment or introduction of a single DSB were not different between the wild-type and elg1Δ mutant strains (Fig. 2). When an additional elg1Δ mutation was incorporated into the pif1-m2 mutant strain, which is defective in Pif1's telomerase inhibition function, no breakpoint spectrum change was observed (Fig. 2). However, the GCR rate in the pif1-m2 elg1Δ mutant strain is much higher than that of a strain carrying either single mutation (Table 3) (39).

FIG. 1.

DNA damage caused by MMS treatment or a single DSB caused by HO endonuclease induced the GCR formation in the elg1Δ mutant strain. (A) the wild-type (WT) strain or the elg1Δ mutant strain was treated with 0.1% MMS, and the induction of GCR formation was determined as described in Materials and Methods. (B) The GCR frequency in the presence or absence of HO endonuclease was determined as described in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 2.

Sequences at the junction of GCRs in strains carrying the elg1Δ mutation with or without DNA damage. Sequences physically present on the chromosome(s) are underlined. Telomeric sequences added by de novo telomere addition are in lowercase. ▿, deletion of sequences indicated below. The proportion and percentage of each class of GCR are in parentheses. The nucleotide positions of breakpoints coordinated on the basis of the Stanford Saccharomyces Genome Database system are in brackets. One case showed sequences unidentified in the SGD after the breakpoint from the pif1-m2 elg1Δ mutant strain. Two cases showed an insertion of unknown sequences in the wild type, and one case showed an insertion of chromosome III sequences in the elg1Δ mutant strain from HO-induced GCRs.

TABLE 3.

Effect of elg1Δ on the rate of accumulating GCRs in different GCRa mutator strains

| Relevant genotype | Wild type

|

elg1Δ

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | GCR rate, 1010 (Canr 5-FOAr) | Strain | GCR rate, 1010 (Canr 5-FOAr) | |

| Wild type | RDKY3615 | 3.5 (1) | YKJM1405 | 173 (49) |

| rad27Δ | RDKY3630 | 4,400 (1,257) | YKJM1677 | 5,795 (1,655) |

| rfa1-t33 | RDKY3617 | 4,700 (1,342) | YKJM1675 | 5,420 (1,540) |

| srs2Δ | RDKY3749 | >3.2 (1) | YKJM1667 | 112 (32) |

| yku70Δ | RDKY3731 | 4.1 (1.1) | YKJM1673 | >4.0 (1) |

| cac1Δ | RDKY4753 | 1,200 (343) | YKJM1592 | 5,880 (1,680) |

| asf1Δ | RDKY4756 | 250 (71) | YKJM2197 | 4,650 (1,328) |

| pif1-m2 | RDKY4343 | 630 (180) | YKJM1403 | 3,000 (857) |

| est2Δ | RDKY3745 | >2.2 (1) | YKJM1594 | 68 (19) |

| rif1Δ | RDKY4361 | 9.9 (3) | YKJM1889 | 210 (60) |

All strains are isogenic with wild-type strain RDKY3615 (ura3-52 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 lys2ΔBgl hom3-10 ade2Δ1 ade8 hxt13::URA3) with the exception of the indicated mutations. The values in parentheses are GCR induction relative to the wild-type GCR rate.

Such strong induction of GCR formation by treatment with further DNA-damaging agents was observed in strains defective in different S-phase checkpoints presumably because of their lack of sensing of unrepaired DNA damage in the cell that causes GCR formation (29, 30). In the elg1Δ mutant strain, extra DNA damage caused by MMS treatment or a single DSB caused by an HO endonuclease generates an excess amount of DNA damage that might eventually saturate the DNA damage checkpoint capacity. This could be why there was a strong induction of an increase in the GCR frequency upon treatment of the elg1Δ mutant strain with a DNA-damaging agent.

Mutation in the ELG1 gene showed different genetic interactions with strains defective in various cell cycle checkpoints.

In order to investigate whether the activation of DNA damage checkpoints, especially the intra-S checkpoint during S phase, is really needed to suppress GCR formation in the absence of Elg1, GCR rates in strains defective in different cell cycle checkpoint genes with the elg1Δ mutation were measured. Recently, we reported that there are at least three different S-phase checkpoints functioning for suppression of GCRs (30). Loss of the DNA replication checkpoint, which is presumably activated because of stalled replication forks, increased the GCR rate significantly. The other two intra-S checkpoint branches that are controlled redundantly by the Rad24-Rad17-Ddc1-Mec3 complex and Sgs1 also suppress GCRs (10, 30). The elg1Δ mutation increased the GCR rate up to 49-fold compared to that of the wild type (Table 2). The dpb11-1 mutation, which creates a defect in the DNA replication checkpoint, did not produce any significant differences in the GCR rate compared to that observed in the elg1Δ mutant strain (Table 2). However, this GCR rate of dpb11-1 elg1Δ was lower than that of dpb11-1 itself. When the mutations of the intra-S checkpoint sensors rad24Δ and sgs1Δ were combined with the elg1Δ mutation, the GCR rates were synergistically increased (Table 2). The mutation in the MRE11 gene that knocks down both intra-S checkpoints also synergistically increased the GCR rate observed in the elg1Δ mutant strain.

In S. cerevisiae, the Mec1 and Tel1 kinases transduce the S-phase checkpoint signal to downstream target proteins by phosphorylation (23). Three different kinases, Rad53, Chk1, and Dun1, function as downstream transducers of Mec1 and Tel1 at S-phase checkpoints. Strains carrying mutations in MEC1 and ELG1 increased the GCR rate synergistically (Table 2). However, the tel1Δ elg1Δ mutant strain did not show any significant difference in the GCR rate compared to that of the elg1Δ mutant strain. The mutations in genes encoding two downstream kinases, RAD53 and CHK1, also synergistically increased the GCR rate in the elg1Δ mutant strain. However, the large increase in the strain carrying the dun1Δ mutation, which inactivates the Dpb11-mediated DNA replication checkpoint for suppression of GCRs, was reduced by the elg1Δ mutation similarly to that of the dpb11-1 elg1Δ mutant strain. Therefore, both Rad24- and Sgs1-dependent intra-S checkpoints that transmit signals to Mec1-Rad53/Chk1 are important for the suppression of further GCR formation in the elg1Δ mutant strain.

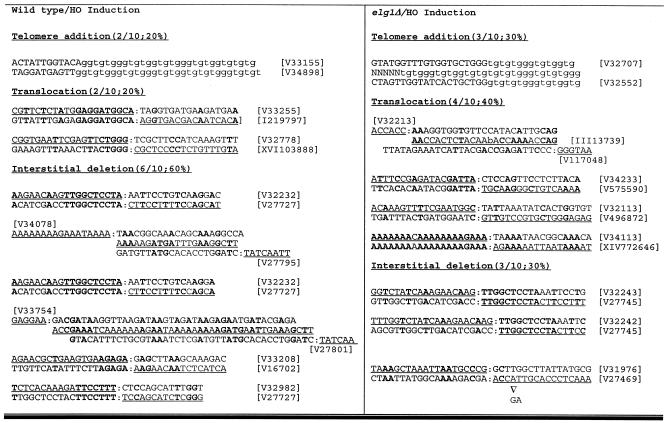

The additional elg1Δ mutation in the dpb11-1 and dun1Δ mutant strains, which are defective in the DNA replication checkpoint, reduced GCR rates compared to those of the dpb11-1 and dun1Δ single-mutant strains (Table 2). This could be due to the activated intra-S checkpoint caused by the elg1Δ mutation. The rad24Δ mutation that inactivates the intra-S checkpoint in the dpb11-1 elg1Δ or dun1Δ elg1Δ mutant strain increased GCR rates more than did the dpb11-1 or dun1Δ mutation (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

The reduction of the GCR formation rate by the elg1Δ mutation in strains defective in the DNA replication checkpoint is due to the elevated intra-S checkpoint activities. (A) An additional rad24Δ mutation increased the GCR rate of the dpb11-1 elg1Δ mutant strain. (B) An additional rad24Δ mutation increased the GCR rate of the dun1Δ elg1Δ mutant strain.

GCRs caused by loss of Elg1 synergistically increase with mutations in different GCR mutator genes.

Mutations in genes encoding other DNA metabolism proteins increased GCR rates. Mutations in the RAD27 gene, which encodes a flap endonuclease for RNA primer removal from lagging-strand DNA replication, increased GCR rates significantly (Table 3) (8). However, the mutation in the ELG1 gene, together with the rad27Δ mutation, increased the GCR rate slightly more than did the rad27Δ mutation alone. Similarly, the elg1Δ mutation combined with the rfa1-t33 mutation, which produces a deficiency in the single-stranded DNA binding activity of the RPA protein, increased the GCR rate slightly more than did the rfa1-t33 mutation alone.

The yku70Δ mutation, which produces defects in nonhomologous end joining and telomere maintenance, or the mutation in SRS2, encoding a suppressor of general recombination, decreased the GCR rate observed in the elg1Δ mutant strain (Table 3). Inactivation of the chromatin assembly factor I or the replication-coupling assembly factor complex, which functions in chromatin assembly during DNA replication and repair, significantly increases GCR formation (31). When the cac1Δ mutation, which inactivates chromatin assembly factor I function, or the asf1Δ mutation, which causes a defect in the replication-coupling assembly factor complex, was combined with the elg1Δ mutation, the GCR rate was synergistically increased (Table 3).

The ELG1 gene was identified as a GCR suppressor gene during the pif1Δ-dependent genome-wide screen (39). PIF1 encodes a telomerase inhibitor, and mutations in the PIF1 gene increased the GCR rate and telomere length (26, 49). The pif1-m2 mutation in the elg1Δ mutant strain increased the GCR rate synergistically (Table 3) (39). The est2Δ mutation, which causes telomerase defects, reduced the GCR rate observed in the elg1Δ mutant strain. However, the rif1Δ mutation, which increases telomere size because of the defect in telomere size detection, which is normally performed through its interaction with Rap1 and Rif2 (47), did not affect the GCR rate in the elg1Δ mutant strain (Table 3).

Telomere length increase in the elg1Δ mutant strain and its interaction with other mutations.

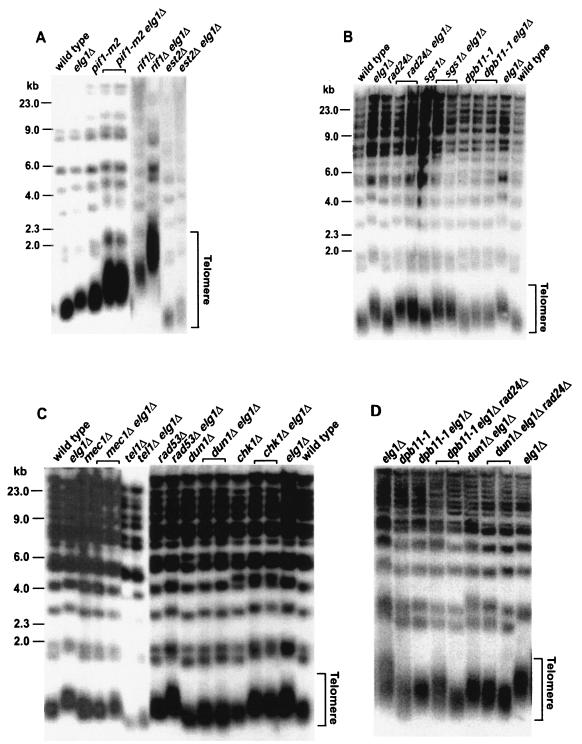

GCRs are caused by defects in at least two different DNA metabolic pathways. One is from replication defects and the other is from telomere maintenance defects (16). Although the GCR increases in the elg1Δ mutant strain seem to be caused mainly by increased DNA damage during DNA replication, it is possible that DNA damage through telomere maintenance defects such as DSBs generated by chromosome fusion and breakage might be a source of GCRs. In order to understand whether Elg1 functions in telomere maintenance, the telomere size of the elg1Δ mutant strain was compared with that of a wild-type control (Fig. 4). The mutation in the ELG1 gene increased the telomere size. In order to understand how the mutation in the ELG1 gene increased telomere size, the telomere lengths of elg1Δ mutant strains with other mutations that have been shown to affect telomere size were determined (Fig. 4A). When the PIF1 gene is mutated, telomere size is increased (49). The increased telomere size observed in the elg1Δ mutation was synergistically increased with an additional pif1-m2 mutation (Fig. 4A). The rif1Δ mutation, which increases telomere size because of the defect in telomere size detection (47), also caused further telomere size lengthening with the elg1Δ mutation. When the EST2 gene, which encodes the telomerase catalytic subunit (19), was mutated in the elg1Δ mutant strain, the telomere size was increased less but the telomere was slightly bigger than that of the est2Δ mutant strain. These observations strongly suggest that the telomere maintenance function of Elg1 is different from Pif1- or Rif1-dependent pathways on the same telomeric substrate.

FIG. 4.

Telomere length was determined in different strains carrying the elg1Δ mutation. Chromosomal DNAs from each strain were digested with XhoI and hybridized with the telomeric repeat probe that can detect the Y′ class of telomeres. (A) Mutations in telomere maintenance genes had synergistic effects on telomere size when combined with the elg1Δ mutation. (B) S-phase checkpoint sensor gene mutations along with the elg1Δ mutation generated different telomere size changes. (C) The elg1Δ mutation in strains defective in S-phase checkpoint transducer genes also changed telomere length differently. (D) An additional mutation in the RAD24 gene in strains carrying elg1Δ and genes functioning in the DNA replication checkpoint slightly decreased telomere size.

It has been shown that the increased level of single-strand overhang in the telomere is one source of DNA damage that induces a cell cycle checkpoint. However, the level of single-strand overhang at the telomere terminus in the elg1Δ mutant strain did not show any difference from that of the wild type (data not shown).

When we compared the telomere length variation and the GCR rates of elg1Δ mutant strains with an additional mutation in telomere maintenance genes, they were well correlated, except for the rif1Δ mutation. For example, the pif1-m2 elg1Δ double mutation, which increased the telomere size synergistically, also increased the GCR rate synergistically (Table 2 and Fig. 4A). Similarly, the elg1Δ est2Δ double mutation, which decreased the telomere size observed in the elg1Δ mutant strain, decreased the GCR rate of that strain. In order to understand whether telomere size affected by the elg1Δ mutation has a close relationship with GCR formation, the telomere length of the elg1Δ mutant strain carrying mutations in checkpoint genes was investigated. Whereas a strain carrying a mutation in an intra-S checkpoint sensor such as rad24Δ or sgs1Δ together with the elg1Δ mutation showed an increase in telomere size up to the level of the elg1Δ mutant strain, the telomere length of the dpb11-1 elg1Δ mutant strain was not increased (Fig. 4B).

Thus, the telomere length and GCR rate increases induced by the elg1Δ mutation in strains defective in different checkpoint sensors are correlated. Next, the telomere lengths of strains carrying mutations in the S-phase downstream kinases with the elg1Δ mutation were determined (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, in cases in which the synergistic GCR rate increases were observed (i.e., rad53Δ and chk1Δ in Table 2), the telomere sizes were increased by the elg1Δ mutation. The dun1Δ elg1Δ and tel1Δ elg1Δ mutations, which did not increase the GCR rates, also did not produce telomere lengthening. The mec1 mutation, however, is an exception since it did not change the telomere length of the strain carrying both the mec1Δ and elg1Δ mutations despite a synergistic increase in the GCR rate. When an additional mutation in the RAD24 gene was added to the dun1Δ elg1Δ mutant strain, the GCR rate was increased even more than that of the dun1Δ strain (Fig. 3). The telomere length of the dun1Δ elg1Δ rad24Δ mutant strain was not changed or was slightly decreased compared to that of the dun1Δ elg1Δ mutant strain (Fig. 4D). Similarly, telomere size was not changed or was slightly decreased by an additional rad24Δ mutation in the dpb11-1 elg1Δ mutant strain although the GCR rate was increased (Fig. 3 and 4D).

DISCUSSION

Previously, we identified 10 new GCR mutator genes through genome-wide screening of S. cerevisiae (39). ELG1, one of the GCR mutator genes identified, has been documented as a gene functioning in different DNA metabolisms (2, 3, 12, 14, 37, 40). In the present study, we further characterized how Elg1 is involved in the suppression of GCRs and what other mechanisms are activated in the absence of Elg1 to prevent GCRs. Elg1 functions to suppress spontaneous DNA damage during DNA replication presumably by participating in an alternative RFC. The delayed DNA replication or the increased sister chromatid exchange rates in the elg1Δ mutant strain suggest that there is frequent DNA damage such as the collapsed DNA replication fork or an increased number of gaps in the daughter strand (2, 14). It is also possible that Elg1 itself functions as a cell cycle checkpoint sensor the loss of which could increase the chance that DNA damage will escape proper DNA repair and as a result enhance unrepaired DNA damage to form GCRs.

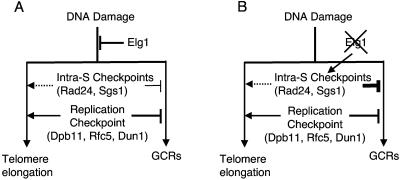

The strong induction of GCR formation by MMS treatment or a single DSB caused by an HO endonuclease in the elg1Δ mutant strain strongly suggests that GCR formation in that strain is due to an increase in DNA damage and further DNA damage saturates the intra-S checkpoints that suppress GCR formation in the elg1Δ mutant strain (Fig. 1 and 5). This conclusion is also supported by the synergistic GCR rate increase in the elg1Δ mutant strain caused by an additional mutation in chromatin assembly factor genes that creates more DNA damage (Table 3). The delayed S-phase progression observed in the elg1Δ mutant strain (2, 14) supports the notion that enhanced DNA damage in the elg1Δ mutant strain activates the intra-S checkpoint. The synergistic increases observed in the strains defective in ELG1 with RAD24, SGS1, MEC1, RAD53, or CHK1 (Table 2) also support the role of an activated intra-S checkpoint in the suppression of GCRs by repairing DNA damage in the elg1Δ mutant strain. Therefore, the spontaneous GCR rate of the elg1Δ mutant strain may be lower than those of other GCR mutators because of the suppression of GCRs by the activated intra-S checkpoints (Fig. 5). However, since the deficiency in the intra-S checkpoint also increased the GCR rate in the presence of Elg1, the mutation in ELG1 could increase spontaneous DNA damage to produce a synergistic GCR rate increase in strains defective in the intra-S checkpoint (28, 30).

FIG. 5.

Hypothetical model how Elg1, the intra-S checkpoints, and the DNA replication checkpoint function together to suppress GCRs and telomere elongation. (A) Elg1, the intra-S checkpoint, and the DNA replication checkpoint all function to suppress GCRs at different levels redundantly. Unlike Elg1, which functions to suppress telomere elongation, the DNA replication checkpoint is required for the telomere elongation in the absence of Elg1. The intra-S checkpoint seems also to be involved in telomere elongation (dashed line). (B) In the absence of Elg1, the intra-S checkpoint is highly activated because of DNA damage. This is why the large increase in GCR formation observed in strains defective in the DNA replication checkpoint is suppressed by the elg1Δ mutation. Telomere size is increased because of the lack of Elg1, but in the absence of the DNA replication checkpoint, telomere size was not increased or was only slightly increased by the elg1Δ mutation since the DNA replication checkpoint is required for telomere elongation by the elg1Δ mutation (solid line arrow). An additional mutation in the intra-S checkpoint in strains carrying elg1Δ and a mutation in genes for the DNA replication checkpoint (dpb11-1 and dun1Δ) further decreased telomere size. This suggests that the intra-S checkpoint also seems to function in telomere elongation in the absence of Elg1 (dashed line arrow).

Inactivation of the DNA replication checkpoint by a mutation such as dpb11-1, rfc5-1, or dun1Δ increased the GCR rate significantly (28, 30). However, such increased GCR rates were reduced by an additional elg1Δ mutation in these strains (Table 2 and Fig. 3). Thus, the activated intra-S checkpoint due to the elg1Δ mutation might function to suppress GCR formation in strains defective in the DNA replication checkpoint (Fig. 5). Supporting this hypothesis is evidence that an additional inactivation of the intra-S checkpoint by the rad24Δ mutation increased the GCR rates to levels even higher than those observed in the dpb11-1 and dun1Δ mutant strains (Fig. 3). This large increase in GCR rates caused by an additional rad24Δ mutation in the dpb11-1 elg1Δ or dun1Δ elg1Δ mutant strain is similar to those observed in strains carrying the rad24Δ dpb11-1 or rad24Δ dun1Δ mutations (28, 30). During DNA replication, a spontaneously stalled replication fork should be sensed by the DNA replication checkpoint and repaired (23). However, if there is no DNA replication checkpoint, a stalled replication fork would be collapsed and produce GCRs. In this step, Elg1, which might be enriched at the stalled replication fork, sometimes opens a channel to GCR formation because of the lack of time for recruiting DNA repair machinery. However, if there is no Elg1 along with the DNA replication checkpoint, other RFCs, such as the Rad24-containing RFC that seems to be activated in the elg1Δ mutant strain, can access DNA damage and proper DNA repair can be performed (Fig. 5).

However, it is also possible that the loss of Elg1 in strains defective in the DNA replication checkpoint simply increases DNA damage, which can cause cells to die even before the generation of GCRs. If this were the case, the dpb11-1 elg1Δ mutant strain would show growth defects or be more sensitive to DNA-damaging agents than the dpb11-1 mutant strain is. However, the dpb11-1 elg1Δ mutant strain did not show any higher sensitivity to many DNA-damaging agents, including UV, ionizing radiation, MMS, and HU (data not shown). Spontaneous DNA damage such as stalled and/or collapsed replication forks is subject to the DNA replication checkpoint to activate DNA repair machinery to suppress GCRs. If the DNA replication checkpoint is not available, cells choose the intra-S checkpoint for repair. Therefore, in the absence of Elg1, cells choose the activated intra-S checkpoint to suppress further GCR formation.

The telomere size of the elg1Δ mutant strain was larger than that of the wild type (Fig. 4), consistent with other results (14, 40). Other known mutations that increased telomere length, including rif1Δ and pif1-m2, synergistically increased telomere size when combined with the elg1Δ mutation (Fig. 4A). Inactivation of the telomerase catalytic subunit Est2 in the elg1Δ mutant strain reduced telomere size almost to the est2Δ mutant strain level. PIF1 encodes a helicase that functions as an inhibitor of telomerase (26, 49). Rif1 senses the size of the telomere to keep telomere repeats at a certain length through interaction with the Rap1 and Rif2 proteins (47). The synergistic increase in telomere size in strains carrying the elg1Δ mutation along with mutations in these genes suggests that Elg1 functions neither as a direct regulator of telomerase nor as a telomere size sensor. The increase in telomere length in the elg1Δ mutant strain depends on active telomerase and replication machinery (40; this study), suggesting that Elg1 might participate in replication of lagging-strand synthesis at the telomere.

Telomere length and GCR rates correlated very well in strains carrying the elg1Δ mutation. One possible explanation for this correlation is the location of the GCR assay in chromosome V. The GCR assay is located near the telomere and is possibly affected by telomere size. However, many GCR mutations that actually decrease telomere size, such as mre11Δ, rad50Δ, and xrs2Δ, also increased the GCR rate (5, 8, 32). Even other mutations, such as rif1Δ and rif2Δ, that increased the telomere size did not increase the GCR rate (26, 47). Therefore, it is very unlikely that a correlation between telomere size and GCR rates such as that observed in strains containing the elg1Δ mutation is due to the location of the GCR assay.

The increased telomere length of the elg1Δ mutant strain was decreased by DNA replication checkpoint defects (Fig. 4C and D and 5). Therefore, the DNA replication checkpoint is required for telomere lengthening by the inactivation of Elg1. The slight decrease in telomere length caused by an additional rad24Δ mutation in the dpb11-1 elg1Δ and dun1Δ elg1Δ mutant strains suggests that the activated intra-S checkpoint is at least partially important to maintain or increase telomere size in strains defective in the DNA replication checkpoint and Elg1 (Fig. 4D and 5). The DNA replication checkpoint signaled through Dpb11/Rfc5, Mec1, Tel1, and Dun1 is activated and transduces a signal to downstream proteins for telomere lengthening or generates time for telomerase or DNA polymerase further to replicate telomere sequences in the elg1Δ mutant strain.

Maintaining genome stability is essential for cell growth and survival. However, because of mutations in mutator genes or genotoxic stresses, different types of genome instability are generated (16, 20, 44). Such genome instability in mammalian cells further leads to the activation of protooncogenes or inactivation of tumor suppressor genes. As a result, cells are transformed and develop cancer phenotypes. Thus, a clear understanding at the molecular level of how genome stability is maintained is crucial for future therapeutic applications against cancer. The present study of the yeast ELG1 gene as a new GCR suppressor gene and its interactions with other GCR suppression mechanisms can shed light on how spontaneous DNA damage that might lead to GCRs is suppressed during DNA replication. We recently cloned the mammalian homolog of the ELG1 gene, and its role in suppression of GCRs is under investigation. One intriguing observation is the deletion of human chromosome 17q11.2 (where human ELG1 is located) in neurofibromatosis (13), which suggests a putative role for human ELG1 as a tumor suppressor gene to suppress GCRs.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Kolodner (University of California San Diego) for helpful discussions. We greatly appreciate a scientific editor at the National Human Genome Research Institute, J. Swyers (National Institutes of Health), and members of the K. Myung laboratory for comments on the manuscript. K. Myung especially thanks E. Cho.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bell, D. W., J. M. Varley, T. E. Szydlo, D. H. Kang, D. C. Wahrer, K. E. Shannon, M. Lubratovich, S. J. Verselis, K. J. Isselbacher, J. F. Fraumeni, J. M. Birch, F. P. Li, J. E. Garber, and D. A. Haber. 1999. Heterozygous germ line hCHK2 mutations in Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Science 286:2528-2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellaoui, M., M. Chang, J. Ou, H. Xu, C. Boone, and G. W. Brown. 2003. Elg1 forms an alternative RFC complex important for DNA replication and genome integrity. EMBO J. 22:4304-4313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Aroya, S., A. Koren, B. Liefshitz, R. Steinlauf, and M. Kupiec. 2003. ELG1, a yeast gene required for genome stability, forms a complex related to replication factor C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:9906-9911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackburn, E. H., S. Chan, J. Chang, T. B. Fulton, A. Krauskopf, M. McEachern, J. Prescott, J. Roy, C. Smith, and H. Wang. 2000. Molecular manifestations and molecular determinants of telomere capping. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 65:253-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulton, S. J., and S. P. Jackson. 1998. Components of the Ku-dependent non-homologous end-joining pathway are involved in telomeric length maintenance and telomeric silencing. EMBO J. 17:1819-1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carney, J. P., R. S. Maser, H. Olivares, E. M. Davis, M. Le Beau, J. R. Yates III, L. Hays, W. F. Morgan, and J. H. Petrini. 1998. The hMre11/hRad50 protein complex and Nijmegen breakage syndrome: linkage of double-strand break repair to the cellular DNA damage response. Cell 93:477-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan, S. W., and E. H. Blackburn. 2003. Telomerase and ATM/Tel1p protect telomeres from nonhomologous end joining. Mol. Cell 11:1379-1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, C., and R. D. Kolodner. 1999. Gross chromosomal rearrangements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae replication and recombination defective mutants. Nat. Genet. 23:81-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis, N. A., J. Groden, T. Z. Ye, J. Straughen, D. J. Lennon, S. Ciocci, M. Proytcheva, and J. German. 1995. The Bloom's syndrome gene product is homologous to RecQ helicases. Cell 83:655-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frei, C., and S. M. Gasser. 2000. The yeast Sgs1p helicase acts upstream of Rad53p in the DNA replication checkpoint and colocalizes with Rad53p in S-phase-specific foci. Genes Dev. 14:81-96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang, D., and D. Koshland. 2003. Chromosome integrity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the interplay of DNA replication initiation factors, elongation factors, and origins. Genes Dev. 17:1741-1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang, M. E., A. G. Rio, A. Nicolas, and R. D. Kolodner. 2003. A genomewide screen in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for genes that suppress the accumulation of mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:11529-11534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenne, D. E., S. Tinschert, E. Stegmann, H. Reimann, P. Nurnberg, D. Horn, I. Naumann, A. Buske, and G. Thiel. 2000. A common set of at least 11 functional genes is lost in the majority of NF1 patients with gross deletions. Genomics 66:93-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanellis, P., R. Agyei, and D. Durocher. 2003. Elg1 forms an alternative PCNA-interacting RFC complex required to maintain genome stability. Curr. Biol. 13:1583-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitao, S., A. Shimamoto, M. Goto, R. W. Miller, W. A. Smithson, N. M. Lindor, and Y. Furuichi. 1999. Mutations in RECQL4 cause a subset of cases of Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Nat. Genet. 22:82-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolodner, R. D., C. D. Putnam, and K. Myung. 2002. Maintenance of genome stability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 297:552-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lea, D. E., and C. A. Coulson. 1948. The distribution of the numbers of mutants in bacterial populations. J. Genet. 49:264-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee, S. E., D. A. Bressan, J. H. Petrini, and J. E. Haber. 2002. Complementation between N-terminal Saccharomyces cerevisiae mre11 alleles in DNA repair and telomere length maintenance. DNA Repair 1:27-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lendvay, T. S., D. K. Morris, J. Sah, B. Balasubramanian, and V. Lundblad. 1996. Senescence mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with a defect in telomere replication identify three additional EST genes. Genetics 144:1399-1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lengauer, C., K. W. Kinzler, and B. Vogelstein. 1998. Genetic instabilities in human cancers. Nature 396:643-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lengronne, A., and E. Schwob. 2002. The yeast CDK inhibitor Sic1 prevents genomic instability by promoting replication origin licensing in late G1. Mol. Cell 9:1067-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loeb, L. A., K. R. Loeb, and J. P. Anderson. 2003. Multiple mutations and cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:776-781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Longhese, M. P., M. Clerici, and G. Lucchini. 2003. The S-phase checkpoint and its regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res. 532:41-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopes, M., C. Cotta-Ramusino, A. Pellicioli, G. Liberi, P. Plevani, M. Muzi-Falconi, C. S. Newlon, and M. Foiani. 2001. The DNA replication checkpoint response stabilizes stalled replication forks. Nature 412:557-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matzke, M. A., M. F. Mette, T. Kanno, and A. J. Matzke. 2003. Does the intrinsic instability of aneuploid genomes have a causal role in cancer? Trends Genet. 19:253-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myung, K., C. Chen, and R. D. Kolodner. 2001. Multiple pathways cooperate in the suppression of genome instability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 411:1073-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myung, K., A. Datta, C. Chen, and R. D. Kolodner. 2001. SGS1, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologue of BLM and WRN, suppresses genome instability and homologous recombination. Nat. Genet. 27:113-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myung, K., A. Datta, and R. D. Kolodner. 2001. Suppression of spontaneous chromosomal rearrangements by S phase checkpoint functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell 104:397-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myung, K., and R. D. Kolodner. 2003. Induction of genome instability by DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair 2:243-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myung, K., and R. D. Kolodner. 2002. Suppression of genome instability by redundant S-phase checkpoint pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:4500-4507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myung, K., V. Pennaneach, E. S. Kats, and R. D. Kolodner. 2003. Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromatin-assembly factors that act during DNA replication function in the maintenance of genome stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nugent, C. I., G. Bosco, L. O. Ross, S. K. Evans, A. P. Salinger, J. K. Moore, J. E. Haber, and V. Lundblad. 1998. Telomere maintenance is dependent on activities required for end repair of double-strand breaks. Curr. Biol. 8:657-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pennaneach, V., and R. D. Kolodner. 2004. Recombination and the Tel1 and Mec1 checkpoints differentially effect genome rearrangements driven by telomere dysfunction in yeast. Nat. Genet. 36:612-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rennstam, K., B. Baldetorp, S. Kytola, M. Tanner, and J. Isola. 2001. Chromosomal rearrangements and oncogene amplification precede aneuploidization in the genetic evolution of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 61:1214-1219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santocanale, C., and J. F. Diffley. 1998. A Mec1- and Rad53-dependent checkpoint controls late-firing origins of DNA replication. Nature 395:615-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savitsky, K., A. Bar-Shira, S. Gilad, G. Rotman, Y. Ziv, L. Vanagaite, D. A. Tagle, S. Smith, T. Uziel, S. Sfez, et al. 1995. A single ataxia telangiectasia gene with a product similar to PI-3 kinase. Science 268:1749-1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scholes, D. T., M. Banerjee, B. Bowen, and M. J. Curcio. 2001. Multiple regulators of Ty1 transposition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have conserved roles in genome maintenance. Genetics 159:1449-1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shirahige, K., Y. Hori, K. Shiraishi, M. Yamashita, K. Takahashi, C. Obuse, T. Tsurimoto, and H. Yoshikawa. 1998. Regulation of DNA-replication origins during cell-cycle progression. Nature 395:618-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith, S., J. Y. Hwang, S. Banerjee, A. Majeed, A. Gupta, and K. Myung. 2004. Mutator genes for suppression of gross chromosomal rearrangements identified by a genome-wide screening in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:9039-9044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smolikov, S., Y. Mazor, and A. Krauskopf. 2004. ELG1, a regulator of genome stability, has a role in telomere length regulation and in silencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:1656-1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stewart, G. S., R. S. Maser, T. Stankovic, D. A. Bressan, M. I. Kaplan, N. G. Jaspers, A. Raams, P. J. Byrd, J. H. Petrini, and A. M. Taylor. 1999. The DNA double-strand break repair gene hMRE11 is mutated in individuals with an ataxia-telangiectasia-like disorder. Cell 99:577-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanaka, S., and J. F. Diffley. 2002. Deregulated G1-cyclin expression induces genomic instability by preventing efficient pre-RC formation. Genes Dev. 16:2639-2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Varon, R., C. Vissinga, M. Platzer, K. M. Cerosaletti, K. H. Chrzanowska, K. Saar, G. Beckmann, E. Seemanova, P. R. Cooper, N. J. Nowak, M. Stumm, C. M. Weemaes, R. A. Gatti, R. K. Wilson, M. Digweed, A. Rosenthal, K. Sperling, P. Concannon, and A. Reis. 1998. Nibrin, a novel DNA double-strand break repair protein, is mutated in Nijmegen breakage syndrome. Cell 93:467-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vessey, C. J., C. J. Norbury, and I. D. Hickson. 1999. Genetic disorders associated with cancer predisposition and genomic instability. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 63:189-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wach, A., A. Brachat, R. Pohlmann, and P. Philippsen. 1994. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 10:1793-1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watanabe, K., J. Morishita, K. Umezu, K. Shirahige, and H. Maki. 2002. Involvement of RAD9-dependent damage checkpoint control in arrest of cell cycle, induction of cell death, and chromosome instability caused by defects in origin recognition complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 1:200-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wotton, D., and D. Shore. 1997. A novel Rap1p-interacting factor, Rif2p, cooperates with Rif1p to regulate telomere length in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 11:748-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu, C. E., J. Oshima, Y. H. Fu, E. M. Wijsman, F. Hisama, R. Alisch, S. Matthews, J. Nakura, T. Miki, S. Ouais, G. M. Martin, J. Mulligan, and G. D. Schellenberg. 1996. Positional cloning of the Werner's syndrome gene. Science 272:258-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou, J., E. K. Monson, S. Teng, V. P. Schulz, and V. A. Zakian. 2000. Pif1p helicase, a catalytic inhibitor of telomerase in yeast. Science 289:771-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zou, H., and R. Rothstein. 1997. Holliday junctions accumulate in replication mutants via a RecA homolog-independent mechanism. Cell 90:87-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]