Abstract

Oct4A is a master regulator of self-renewal and pluripotency in embryonic stem cells. It is a well-established marker for cancer stem cell (CSC) in malignancies. Recently, using a loss of function studies, we have demonstrated key roles for Oct4A in tumor cell survival, metastasis and chemoresistance in in vitro and in vivo models of ovarian cancer. In an effort to understand the regulatory role of Oct4A in tumor biology, we employed the use of an ovarian cancer shRNA Oct4A knockdown cell line (HEY Oct4A KD) and a global mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomic analysis to investigate novel biological targets of Oct4A in HEY samples (cell lysates, secretomes and mouse tumor xenografts). Based on significant differential expression, pathway and protein network analyses, and comprehensive literature search we identified key proteins involved with biologically relevant functions of Oct4A in tumor biology. Across all preparations of HEY Oct4A KD samples significant alterations in protein networks associated with cytoskeleton, extracellular matrix (ECM), proliferation, adhesion, metabolism, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), cancer stem cells (CSCs) and drug resistance was observed. This comprehensive proteomics study for the first time presents the Oct4A associated proteome and expands our understanding on the biological role of this stem cell regulator in carcinomas.

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the most lethal of all the gynaecological malignancies with a five-year mortality rate of >70%1. This poor outcome is due to the fact that the majority of OC cases are diagnosed at an advanced metastatic stage when the disease is no longer confined to the ovaries and is typically characterised by a widespread peritoneal dissemination and ascites1. While cytoreductive surgery and chemotherapy are initially effective in treating the disease in the short-term, relapse in advanced-stage patients is inevitable and almost all patients develop highly aggressive recurrent disease within few months which is intrinsically resistant to chemotherapy. Recent observations suggest OC recurrence may be driven by a sub-population of tumor cells which exhibit stem cell-like traits2,3. These cells, termed cancer stem cells (CSCs) not only display increased self-renewal characteristics as seen in embryonic stem cells (ESCs), but also exhibit tumorigenic survival properties and have been implicated in chemoresistance4,5. The molecular mechanisms which drive CSC-mediated OC progression, chemoresistance and recurrence have not yet been fully elucidated.

The presence and importance of CSCs in different cancer scenarios including OC has been accumulating for the last ten years. However, the origin and the biological identity of CSCs associated proteome still remains unclear. Several potential indirect mechanisms of CSC regulation have been proposed; of particular interest are the Notch, Hedgehog, Janus activated kinase/Signal transduction and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT), anti-apoptotic and drug-resistant pathways5,6,7. Others mechanisms include; malignant transformation of (i) adult stem cells into CSCs8,9; or (ii) multipotent progenitor or transit amplifying cells into CSCs9,10; or (iii) differentiated cells into CSCs which acquire stem cell characteristics after loss of differentiation ability8. A recent study has demonstrated the existence of equilibrium between CSCs and non-CSCs in a tumor with the balance being tipped towards CSCs in response to microenvironmental stimuli11,12. These candidate-based approaches though interesting does not elucidate the exact mechanism of CSC regulation which is absolutely essential to design CSC-based therapeutics required to abrogate clinically the residual tumor source which initiates recurrence.

Oct4 (Oct3/4, POU5F1) is a transcription factor which maintains self-renewal and pluripotency in embryonic stem cells and primordial germ cells13,14,15. The POU5F1 gene encodes two transcript variants, POU5F1A (Oct4A) and POU5F1B (Oct4B) which consist of 360 and 255 amino acids respectively, but share a common carboxyl-terminus of 225 amino acids13,16. Oct4B is generally localised in the cytoplasm, while Oct4A is localized mainly in the nucleus and has been associated with the maintenance of an undifferentiated state and stem cell properties of embryonic stem cells as well as primordial germ cells15,16. In addition, Oct4A expression has been shown as a diagnostic marker in germ cell tumors17. Recent studies have demonstrated elevated expression of Oct4 in several somatic tumors including breast, bladder, prostate, lung as well as of ovarian origin13. However, most studies have investigated Oct4 as a tumor marker; and only a handful of studies have reported expression analyses discriminating the Oct4A and Oct4B isoforms13,18. Hence, it remains undetermined whether Oct4 expression in most tumor groups is specific for stemness and/or CSCs, or it is just another tumorigenic marker used for expression analysis. Recently, transcriptomic, genomic and systems biology methods have identified Oct4 to be associated in an intricate regulatory network with Sox-2 and Nanog which results in the activation of transcription of genes required for pluripotency19,20. It is well established that the mRNA levels in a cellular system do not necessarily reflect protein abundance, and post-translational modification of proteins rapidly modulate protein activity and transduce signals crucial in maintaining stemness, differentiation, metastasis and drug resistance. However, the post-translational event of a cellular network which is important to map the regulatory mechanism of pluripotency or stemness cannot be identified by genomic and epigenomic studies and still remains obscured21. Hence elucidating the proteome of CSCs represents a rich informative repertoire of understanding cancer metastasis and recurrence.

MS-based proteomics has essentially changed the way by which malignant initiation and progression is investigated by its ability to identify and monitor thousands of proteins and post-translational modifications22. In OC, biomarker research for early-stage screening has become one of the most exciting uses for MS-based proteomics analysis23,24. Clinical specimens including tumors, ascites and serum samples have been assessed for distinct protein/peptide signatures to identify novel proteins which may assist in disease detection25. Recently, the methodology has also been used to identify novel therapeutic targets for recurrent diseases based on protein signatures of chemotherapy treated patients26. MS-based proteomics of CSCs therefore offers an advantage to study post-transcriptional regulation and signalling network of CSCs associated with self-renewal, differentiation, tumor progression as well as recurrence due to drug resistance. At the same time it provides a platform to study the proteome of a specific CSC marker in a targeted and high-throughput manner that allows dissection of crucial CSC-specific biology. It also provides avenues in dissecting fundamental differences between CSCs and adult stem cells, CSCs and embryonic stem cells and CSCs and pluripotent stem cells.

Using a large-scale, label-free quantitative MS-based proteomic profiling approach, this study for the first time identified novel proteins and/or peptides which are associated specifically with Oct4A in the HEY ovarian cancer cell line and an associated mouse xenograft model. By identifying specific protein targets and select protein networks associated with differential expression of Oct4A, this study aimed to contribute to our knowledge of the biological traits driven specifically by Oct4A in OC and potentially other tumor models.

Methods and Materials

Cell lines

The development of the HEY vector control and HEY Oct4A KD cell lines has been described previously27. SKOV3 and OVCAR5 cell lines have also been described previously27. Cells were grown in RPMI-1640 growth media supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat inactivated FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen, Australia) and an antibiotic combination of 1% (v/v) streptomycin and penicillin (Invitrogen, Australia). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2 and routinely checked for mycoplasma infection.

Treatment of ovarian cancer cell lines with paclitaxel and cisplatin

Ovarian cancer cell lines were treated with paclitaxel and cisplatin at GI50 concentrations (50% growth inhibitory concentrations) for 72 hrs at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2 as described previously27. For paclitaxel treatment, HEY cells were treated with 1 ng/ml while SKOV3 and OVCAR5 cell lines were treated with 0.5 ng/ml. For cisplatin treatment of OVCAR5 cells a GI50 concentration of 3 μg/ml of cisplatin was used.

Animal studies

Animal studies were carried out as described previously27.

Whole cell lysates and tumor xenograft sample preparation

HEY vector control and HEY Oct4A KD cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 growth media as described previously27. After reaching >70% confluence, cells were washed three times in ice-cold PBS. Protein lysis buffer4% (w/v) SDS, 20% (v/v) glycerol and 0.01% (v/v) bromophenol blue, 0.125 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8 containing complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 1 mM Dithiothreitol was added directly to confluent cells and cells were then sonicated for 180 sec. Collected samples were incubated at 95 °C for 20 min and 60 °C for 2 hrs before being centrifuged at 25,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was stored at -80 °C until required.

For tumor xenograft samples, tumors were produced by intraperitoneal (i.p) injection of HEY Oct4A KD and HEY vector control cells into Balbc/c nude mice as previously described27. Sections of tumor xenografts were homogenised in lysis buffer and sonicated for 180 sec. Homogenates were then incubated at 95 °C for 20 min and 60 °C for 2 hrs before being centrifuged at 25,000 g for 30 min. Each supernatant sample was stored at -80 °C until required.

Secretome Sample Preparation

Conditioned media (CM) collected from sub-confluent (80%) HEY vector control and HEY Oct4A KD cells grown in RPMI-1640 (serum-free) were centrifuged (500 × g for 5 min, 2000 × g for 10 min) CM concentrated by centrifugal ultrafiltration as described previously28. Each concentrated fraction was stored at -80 °C until required.

Protein Quantification

The protein content of whole cell lysate and secreted cellular preparations was estimated by one-way dimensional SDS-PAGE/SYPRO Ruby protein staining densitometry as previously described26,28,29.

Proteomic Analysis

Proteomic analyses were performed as previously described29 in biological replicates (n = 4) and technical duplicates (n = 2). Cell/tumor lysates and secreted sample preparations (10 μg protein) were lysed in SDS sample buffer(2% (w/v), 125 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 12.5% (v/v) glycerol, 0.02% (w/v) bromphenol blue), electrophoresed by short-range SDS-PAGE (10 × 6 mm), and visualized by Imperial Protein Stain (Invitrogen). Individual samples were excised, destained, reduced, alkylated, and trypsinized as described26. A nanoflow Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) instrument (Ultimate 3000 RSLCnano, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was coupled on-line to a Linear Trap Quadropole (LTQ) Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with a nanoelectrospray ion source (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were loaded (Acclaim PepMap100, 5 mm × 300 μm i.d., μ-Precolumn packed with 5 μm C18 beads, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and separated (Acquity UPLC M-Class Peptide BEH130, C18, 1.7 μm, 75 μm × 250 mm, Waters). Data was acquired using Xcalibur software v2.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Database searching and protein identification

Raw data were processed as described previously29 using Proteome Discoverer (v2.1, Thermo Fisher Scientific). MS2 spectra were searched with Mascot (v2.4, Matrix Science), and Sequest HT (v2.1, Thermo Fisher Scientific) against a database of 133,798 ORFs (UniProtHuman, Apr 2016). Peptide lists were generated from a tryptic digestion with up to two missed cleavages, carbamidomethylation of cysteines as fixed modifications, and oxidation of methionines and protein N-terminal acetylation as variable modifications. Precursor mass tolerance was 10 ppm, product ions were searched at 0.06 Da tolerances, minimum peptide length defined at 6, maximum peptide length 144, and max delta CN 0.05. Peptide spectral matches (PSM) were validated using Percolator based on q-values at a 1% false discovery rate (FDR). With Proteome Discoverer, peptide identifications were grouped into proteins according to the law of parsimony and filtered to 1% FDR. Scaffold Q + S (v4.5.3, Proteome Software Inc) was employed to validate MS/MS-based peptide and protein identifications from database searching. Initial peptide identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 95% probability as specified by the Peptide Prophet algorithm. Protein probabilities were assigned by the Protein Prophet algorithm. Protein identifications were accepted, if they reached greater than 99% probability and contained at least 2 identified unique peptides. These identification criteria typically established <1% false discovery rate based on a decoy database search strategy at the protein level. Proteins that contained similar peptides and could not be differentiated based on MS/MS analysis alone, were grouped to satisfy the principles of parsimony. Contaminants and reverse identification were excluded from further data analysis. UniProt was used for protein annotation.

Label-free spectral counting, differentially expression and functional analysis

Significant spectral count (SpC) and Ratio of spectral count (Rsc) were determined as previously described29,30,31. The relative abundance of a protein within a sample was estimated using normalized SpC, where for each individual protein, significant peptide MS/MS spectra (i.e., ion score greater than identity score) were summated, and normalized by the total number of significant MS/MS spectra identified in the sample. The number of significant assigned spectra for each protein was used to determine protein differences between HEY Oct4A KD and the HEY vector control. For each protein the Fisher’s exact test was applied to significant assigned spectra. The resulting p-values were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure32 and statistics performed as previously described26. Differentially expressed proteins were identified using the criteria: Rsc >±1.8 and p < 0.05.

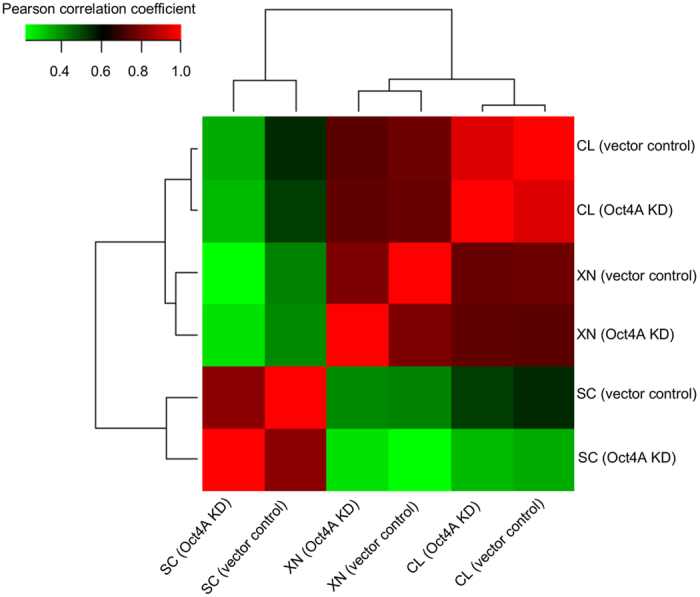

Protein-protein interaction analyses by STRING 10.0

Identification of entriched protein networks in cell lysates, secretomes and xenografts of Oct4AKD vs vector control was performed by STRING 10.0 software33. Clustering of proteins between samples was performed by Pearson correlation between samples using the protein profiles and visualized using gplots (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gplots/index.html) package in R software. Raw data set of proteins identified in vector control and HEY KD samples (cell lysates, secretomes and xenografts) is described in Supplementary Table 1.

RNA extraction and Real-Time (RT) PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed as described previously27. Relative quantification of gene expression was normalized to 18S and calibrated to the appropriate control sample using the SYBR Green-based comparative CT method (2-ΔΔCt). The primer set of Oct4A, vimentin (VIM), plectin (PLEC), TUBB2A and the house keeping gene 18S are described in Table 1.

Table 1. Human oligonucleotide primer sequences for quantitative real-time PCR.

| Gene Symbol | Accession no. | Primer sequences from 5′-3′ | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rn18S | NR_003286.1 | Forward GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATTReverse CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG | 153 |

| Oct4A | NM_002701.4 | Forward CTCCTGGAGGGCCAGGAATCReverse CCACATCGGCCTGTGTATAT | 381 |

| VIM | NM_003380 | Forward CCTACAGGAAGCTGCTGGAAReverse GGTCATCGTGATGCTGAGAA | 198 |

| PLEC | NM_201384 | Forward TACTACCGCGAGAGTGCAGAReverse TCCTTGATGGCGTTGATGTA | 212 |

| TUBB2A | NM_001069.2 | Forward CTTCGGCCAGATCTTCAGACReverse GAGAGTGGGTCAGCTGGAAG | 176 |

Immunohistochemistry of mouse tumors

Immunohistochemistry analysis of mouse tumors was performed as described previously4,5,27. Briefly, formalin fixed, paraffin embedded 4 μm sections of the xenografts were dewaxed with Ventana EZ Prep and endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using the Ventana’s Universal DAB inhibitor. Primary antibodies against Oct4, PLEC, VIM and TUBB2A were diluted according to the instruction provided by the manufacturer and sections were stained using a Ventana Benchmark Immunostainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc, Arizona, USA). Detection was performed using Ventana’s Ultra View DAB detection kit (Roche/Ventana, Arizona, USA) using the method described previously4. Tumor sections were counter stained with Ventana Haematoxylin and Blueing Solution. Immunohistochemistry images were captured and analysed by using Aperio ImageScope v12.1.0.5029 as described previously27.

Results

Proteome analysis of HEY vector control and Oct4A KD samples

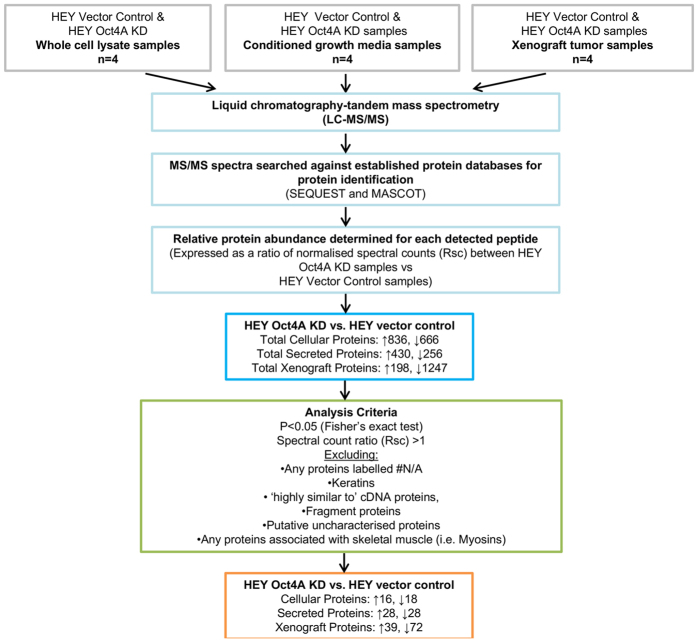

We have recently shown knockdown of Oct4A in a HEY cell line by small hairpin (sh)RNA technology27,34. Knockdown of Oct4A in the HEY cell line (Oct4AKD) was confirmed at the protein level by Western blot and immunofluorescence and at the mRNA level by Quantitative Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)27,34. MS-based proteomics analysis on vector control and Oct4A KD cells showed a total of 836 proteins to be up regulated in HEY Oct4A KD cellular samples compared to HEY vector control samples, while 666 cellular proteins were down regulated in HEY Oct4A KD samples (biological n = 4, technical duplicate) (Fig. 1). For secreted proteins, a total of 430 proteins were up-regulated in HEY Oct4A KD samples compared to HEY vector control, while 256 proteins were down regulated. In mouse xenograft tumors, 198 proteins were up regulated in HEY Oct4A KD samples compared to HEY vector control samples, while 1247 proteins were down-regulated (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the methodology used to obtain protein lists from HEY Oct4A KD samples.

HEY vector control and HEY Oct4A KD cells were prepared as whole cell lysate (n = 4), secretome (n = 4) and xenograft tumor samples (n = 4). Samples were solubilised, separated by short-range SDS-PAGE and subjected to in-gel reduction, alkylation, and tryptic digestion. Extracted peptides were fractionated and identified using mass spectrometry analysis, data processing database searching, informatics and protein annotation. Relative protein abundance was determined by estimating the ratio of normalised spectral counts (Rsc) between HEY Oct4A KD samples and HEY vector control samples for each protein. To determine the classification of proteins in response to Oct4A we applied a stringent analysis filtering criteria. The number of proteins which met the selection criteria for each HEY Oct4A KD sample group is listed.

Protein selection criteria

Following data collection and bioinformatics analyses, proteins which were not differentially expressed (p < 0.05) in HEY Oct4A KD samples when compared to HEY vector control samples were eliminated. Proteins identified as keratins were also removed from analysis based on known contaminants involved in proteomics analysis35. Proteins which had no known protein accession number were also excluded based on the fact that they could not be identified. Other exclusion criteria included any protein identified as a peptide fragment, a putative uncharacterised protein or those which are cDNA-like in nature. This was based on the fact that an accurate protein function may not be identified for these specific peptides. Proteins detected in tumor xenograft samples which were related to skeletal muscle were also excluded from the study based on likelihood of skeletal muscle contamination during tumor xenograft excision. An outline of the protein selection process is described in Fig. 1.

A correlation plot between the samples is presented in Fig. 2. This cluster and normalised heat map analysis revealed that there was a high correlation between different samples (i.e., cell lysates, xenograft lysates and secreted). HEY vector control and Oct4A KD cell samples were most similar in expression profiles, while similarities were identified in cell and xenograft lysates and secreted samples. These protein expression cluster analyses highlight key differences in protein expression between HEY vector control and Oct4A KD sample subsets.

Figure 2. Characterisation of HEY Oct4A subsets reveal correlation between sample subsets in response to Oct4A expression.

Correlation matrix of cell lysates (CL), tumor xenografts (XN), and secretomes (SC) samples representing differential abundance based on normalised spectral count (SpC) values between HEY Oct4A KD and HEY vector control samples. Correlation expression profile reveals that each individual sample represents clear distribution and similarity with other sample subsets.

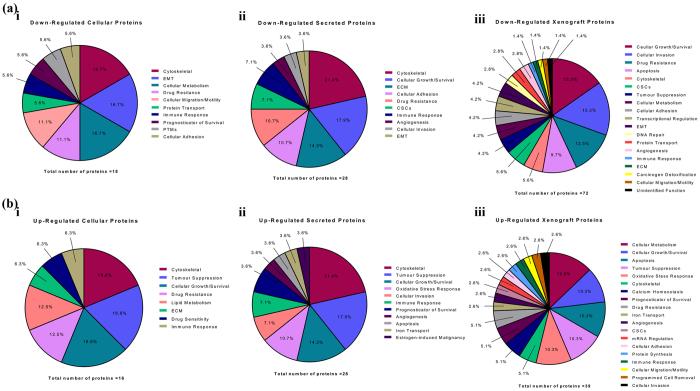

Proposed protein functions of differentially expressed HEY Oct4A KD cellular proteins

Down regulated cellular proteins in HEY Oct4A KD cells compared to Oct4A vector control cells

From the selection criteria stipulated in Fig. 1, a total of 18 cellular proteins were identified to be differentially down regulated in HEY Oct4A KD samples when compared HEY vector control samples (Fig. 1). When classified according to their cellular function, proteins which fit into the categories of cytoskeletal regulation, EMT and cellular metabolism constituted 16.7% and were identified as the most frequently down-regulated proteins in HEY Oct4A KD cellular samples (Table 2, Fig. 3a). This was followed by proteins which were related to drug resistance and cellular migration/motility which constituted 11.1% of each category, followed by protein transport, immune response, prognosticator of survival, post-translational modifications, and cellular adhesion which constituted 5.6% of each category of down regulated proteins (Table 2, Fig. 3a). Of all the identified down regulated cellular proteins, the cytoskeleton-related Tubulin beta-2A chain protein (TUBB2A) was the most abundantly down regulated (Rsc -42.9), followed by the EMT-related protein 14-3-3ε (YWHAE) (Rsc −10.0). Other down regulated cellular proteins which were identified to be of interest included the cellular migration and invasion related actin-binding protein Swiprosin-1 (EFHD2) (Rsc −4.1), the drug resistance-related proteins Glyoxalase 1 (GLO1) (Rsc −3.1) and actin-binding protein Trangelin-2 (TAGLN2) (Rsc −3.0) cellular metabolism-related protein Enoyl-CoA Hydratase 1 (ECHS1) (Rsc −3.7) and cytosketelal as well as extracellular remodelling proteins PLEC (Rsc −1.1) and VIM (Rsc −1.2). A full list of down-regulated cellular proteins and their proposed cancer-related classifications are listed in Table 2 and summarised in Fig. 3a.

Table 2. Down regulated cellular proteins in HEY Oct4A KD cells according to cellular function.

| Category | Gene Name | Protein Description | Rsc | *Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoskeletal | TUBB2A | Tubulin beta-2A chain | -42.9 | (McCarroll and Kavallaris, 2012) |

| ACTC1 | Alpha-cardiac actin | -1.7 | (Tondeleir et al., 2011) | |

| ACTB | Beta-actin | -1.5 | (Guo et al., 2013) | |

| PLEC | Plectin | -1.2 | (Katada, K., et al., 2012) | |

| Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition | YWHAE | 14-3-3ε | -10.0 | (Liu et al., 2013a) |

| PPP2CA | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A catlytic subunit alpha isolform | -3.3 | (Bhardwaj et al., 2014) | |

| VIM | Vimentin | -1.2 | (Mendez et al., 2010) | |

| Cellular metabolism | ECHS1 | Enoyl-CoA Hydratase 1 | -3.7 | (Carracedo et al., 2013) |

| SLC25A3 | Solute carrier damily 25 member 3 | -2.4 | (Palmieri, 2013) | |

| CS | Citrate synthase | -2.4 | (Gaude and Frezza, 2014) | |

| Cellular migration/motility | EFHD2 | Swiprosin-1 | -4.1 | (Huh et al., 2015) |

| PFN1 | Profilin-1 | -1.8 | (Ding et al., 2012) | |

| Drug resistance | GLO1 | Glyoxalase 1 | -3.1 | (Sakamoto et al., 2000) |

| TAGLN2 | Transgelin-2 | -3.0 | (Chen et al., 2014) | |

| Protein transport | SEC63 | Translocation protein SEC63 homolog | -3.4 | (Zimmermann et al., 2006) |

| Cell adhesion | RSU1 | Ras suppressor protein 1 | -2.8 | (Kim et al., 2015b) |

| Immune response | WARS | Tryptophan-tRNA ligase, | -2.8 | (Mellor and Munn, 1999) |

| Prognosticator of survival | ALB | Serum albumin | -1.8 | (Gupta and Lis, 2010) |

| Post-translational modifications | HIST1H4B | Histone H4 | -1.6 | (van der Meijden et al., 1998) |

Rsc: Protein abundance ratio (HEY Oct4A KD/HEY vector control).

Figure 3. Distribution of the potential biological functions of Oct4A protein targets in HEY Oct4A KD cells.

The functions of the Oct4A protein targets obtained from the HEY Oct4A KD cells were searched in the literature and categorised according to their potential cancer-related biological functions. (a) Differentially expressed down regulated proteins are summarised as: (i) down regulated cellular proteins, (ii) down regulated secreted proteins, (iii) downregulated tumor xenograft proteins; (b) Differentially expressed up-regulated proteins are summarised as: (i) up-regulated cellular proteins, (ii) up-regulated secreted proteins, (iii) up-regulated tumor xenograft proteins.

Up regulated cellular proteins in HEY Oct4A KD samples

Compared to HEY vector control samples, a total of 16 differentially up regulated cellular proteins were identified in HEY Oct4A KD samples (Fig. 1). Proteins which are categorised to be associated with cytoskeleton, tumor suppression, cellular growth, as well as those involved in lipid metabolism and drug resistance were identified as the most frequently up regulated in HEY Oct4A KD cellular samples (Fig. 3b, Table 3). The most significantly differential expressed cellular protein identified in HEY Oct4A KD samples was the cytoskeleton-related actin binding protein Plastin-1 (PLS1) (Rsc 7.1). Other up regulated cellular proteins which were identified included the cytoskeletal-related actin binding protein Twinfilin-1 (TWF1) (Rsc 5.1), and the tumor suppression-related proteins Apolipoprotein A-1 (APOA1) (Rsc 5.1) and Eukaryotic release factor 1 (ETF1) (Rsc 2.3). A list of up regulated cellular proteins and their proposed cancer-related classifications are described in Table 3 and summarised in Fig. 3b.

Table 3. Up regulated cellular proteins in HEY Oct4A KD cells.

| Category | Gene Name | Protein Description | Rsc | *Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoskeletal | PLS1 | Plastin-1 | 7.1 | (Delanote et al., 2005) |

| TWF1 | Twinfilin-1 | 5.1 | (Moseley et al., 2006) | |

| EPB41L2 | Erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.1-like 2 | 4.5 | (Lu et al., 2004) | |

| Tumour suppression | APOA1 | Apolipoprotein A-1 | 5.1 | (Zamanian-Daryoush et al., 2013) |

| ETF1 | Eukaryotic release factor 1 | 2.3 | (Dubourg et al., 2002) | |

| AHNAK | Desmoyokin | 1.8 | (Lee et al., 2014) | |

| Cellular growth/survival | TFRC | Transferrin receptor protein 1 (CD71) | 2.9 | (Habashy et al., 2010) |

| DDX3X | ATP-dependant RNA helicase DDX3X | 2.6 | (Lai et al., 2010) | |

| EIF4A2 | Eukaryotic initiation factor 4A2 | 1.8 | (Modelska et al., 2015) | |

| Drug resistance | TYMS | Thymidylate synthase (EC 2.1.1.45) | 5.1 | (Wang et al., 2007) |

| ATP1A1 | Sodium pump subunit alpha-1 | 1.8 | (Stordal et al., 2012) | |

| Lipid metabolism | NCEH1 | Neutral cholestrol ester hydrolase 1 | 3.8 | (Chiang et al., 2006) |

| PRIC295 | Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor interacting complex protein | 2.6 | (Pyper et al., 2010) | |

| Extracellular matrix | PLOD2 | Procollagen-lysine, 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 2 | 2.1 | (Gilkes et al., 2013) |

| Drug sensitivity | PEBP1 (RKIP) | Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein 1 | 1.9 | (Li et al., 2014a) |

| Immune response | FLNC | Filamin-C | 1.4 | (Marti et al., 1997) |

Rsc: Protein abundance ratio (HEY Oct4A KD2/HEY vector control).

Proposed protein functions of differentially expressed HEY Oct4A KD secreted proteins

Down regulated secreted proteins in HEY Oct4A KD samples

Analysis of the secretome revealed a total of 28 proteins were differentially suppressed in HEY Oct4A KD samples compared to HEY vector control samples (Fig. 1). When classified according to their function, a large number of proteins were found to be involved in cytoskeletal functions and cellular growth (Table 4). This was followed by proteins known to be involved with the ECM, CSCs, cellular adhesion and drug resistance. Of the identified down regulated secreted proteins, the ECM-related protein Fibronectin 1 (FN1) was the most significantly differentially expressed protein in HEY Oct4A KD samples (Rsc −15.3). This was closely followed by the ECM-related protein Laminin subunit gamma-2 (LAMC2) (Rsc −10.2). Other down regulated secreted proteins which were identified to be of interest included the ECM-related protein Laminin subunit beta-3 (LAMB3) (Rsc −7.8), the cytoskeleton cellular invasion-associated protein PLEC (Rsc −6.7), the CSC-associated protein CD109 antigen (CD109) (Rsc −5.0) and the drug resistance-related protein and protein identified as concurrently down-regulated in HEY Oct4A KD cellular samples Transgelin-2 (TAGLN2) (Rsc −4.7). Secreted proteins suppressed in HEY Oct4A KD samples and their proposed cancer-related functions are listed in Table 4 and summarised in Fig. 3a.

Table 4. Down regulated secreted proteins in HEY Oct4A KD cells.

| Category | Gene Name | Protein Description | Rsc | *Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoskeletal | TUBB2A | Tubulin beta-2A chain (Tubulin beta class IIa) | -8.0 | (McCarroll and Kavallaris, 2012) |

| APLP2 | Amyloid-like protein 2 | -5.8 | (Pandey et al., 2015) | |

| RDX | Radixin | -5.6 | (Hoeflich and Ikura, 2004) | |

| FLNB | Filamin-B | -5.0 | (Popowicz et al., 2006) | |

| FLNA | Filamin-A | -4.5 | (Popowicz et al., 2006) | |

| ACTN2 | Alpha-actinin-2 | -4.5 | (Djinovic-Carugo et al., 2002) | |

| Cellular growth/survival | UBA1 | Ubiquitin-like modifier-activating enzyme 1 | -5.6 | (Moudry et al., 2012) |

| EIF4A2 | Eukaryotic initiation factor 4A-II | -4.7 | (Modelska et al., 2015) | |

| XPO1 | Exportin-1 | -3.6 | (van der Watt et al., 2009) | |

| CTSD | Cathepsin D (EC 3.4.23.5) | -3.4 | (Langhoff et al.) | |

| CLTC | Clathrin heavy chain 1 | -2.2 | (McMahon and Boucrot, 2011) | |

| Extracellular matrix | FN1 | FN1 protein (Fibronectin 1) | -15.3 | (Singh et al., 2010) |

| LAMC2 | Laminin subunit gamma-2 | -10.2 | (Garg et al., 2014) | |

| LAMB3 | Laminin subunit beta-3 | -7.8 | (Aumailley, 2013) | |

| APP A4 | Amyloid beta A4 protein | -3.2 | (Klier et al., 1990) | |

| Drug resistance | FASN | Fatty acid synthase (EC 2.3.1.85) | -5.3 | (Wu et al., 2014) |

| TAGLN2 | Transgelin-2 | -4.7 | (Chen et al., 2014) | |

| PSAT | Phosphoserine aminotransferase (EC 2.6.1.52) | -3.4 | (Vie et al., 2008) | |

| Cellular adhesion | PPIB | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase B (cyclophilin B) | -4.5 | (Melchior et al., 2008) |

| FN1 FN | Fibronectin (Cleaved into: Anastellin) | -2.9 | (Mercurius and Morla, 2001) | |

| VCL | Vinculin (Metavinculin) | -2.8 | (Demali, 2004) | |

| Cancer stem cells | CD109 | CD109 antigen | -5.0 | (Emori et al., 2013) |

| ANPEP | Aminopeptidase N | -2.8 | (Kim et al., 2012a) | |

| Immune response | LTA4H | Leukotriene A-4 hydrolase | -4.7 | (Chen et al., 2004) |

| AEBP1 | Adipocyte enhancer-binding protein 1 | -3.2 | (Holloway et al., 2012) | |

| Cellular invasion | PLEC | Plectin | -6.7 | (Katada et al., 2012) |

| Angiogenesis | TIE1 | Tyrosine-protein kinase receptor Tie-1 (EC 2.7.10.1) | -3.4 | (Jones et al., 2001) |

| Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition | DRIP4 | Dopamine receptor interacting protein 4 | -2.8 | (Ji et al., 2015) |

Rsc: Protein abundance ratio (HEY Oct4A KD2/HEY vector control).

Up regulated secreted proteins in HEY Oct4A KD samples

Twenty-eight secreted proteins were differentially over-expressed in HEY Oct4A KD conditioned media samples when compared to HEY vector control samples (Fig. 1). Secreted proteins which were identified to have functional roles in cytoskeletal regulation, tumor suppression and cellular growth were found to be the most significantly up regulated in HEY Oct4A KD samples (Table 5). This was followed by proteins involved in oxidative stress response, inflammation and proteins used as prognosticators of survival. The most abundantly up regulated protein was the tumor suppressor-related protein HBB (Rsc 5.0). This was closely followed by the estrogen induced malignancy-associated protein Thyroxine-binding globulin (SERPINA7) (Rsc 4.7). Other up-regulated secreted proteins of interest included the immune response-associated protein Pentraxin-related protein 3 (PTX3) (Rsc 4.1), the oxidative stress response-related protein Glutathione S-transferase phosphate 1 (GSTP1) (Rsc 3.3) and the apoptosis-related protein POTE ankyrin domain family member F (POTEF) (Rsc 2.6). Similar to that identified in HEY Oct4A KD cellular samples, the tumor suppression-associated protein Apolipoprotein A1 (APOA1) was also up regulated in conditioned media preparations of HEY Oct4A KD samples compared to HEY vector control samples (Rsc 4.3). Up regulated secreted proteins and their proposed cancer-related classifications are listed in Table 5 and summarised in Fig. 3b.

Table 5. Up regulated secreted proteins in HEY Oct4A KD cells.

| Category | Gene Name | Protein Description | Rsc | *Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoskeletal | TUBB2C | Tubulin beta-2C | 2.3 | (McCarroll and Kavallaris, 2012) |

| TUBB4A | Tubulin beta-4 chain | 2.5 | (McCarroll and Kavallaris, 2012) | |

| TUBB5 | Tubulin beta-5 chain | 1.7 | (McCarroll and Kavallaris, 2012) | |

| TUBB6 | Tubulin beta-6 chain | 2.1 | (McCarroll and Kavallaris, 2012) | |

| ACTC1 | Actin, alpha cardiac muscle 1 | 2.3 | (Tondeleir et al., 2011) | |

| ACTB | Beta Actin | 2.3 | (Guo et al., 2013) | |

| Tumour suppression | HBB | Mutant beta-globin | 5.0 | (Onda et al., 2005) |

| APOA1 | Apolipoprotein A1 | 4.3 | (Zamanian-Daryoush et al., 2013) | |

| ITIH3 | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H3 | 3.3 | (Paris et al., 2002) | |

| ITIH2 | Inter-alpha (Globulin) inhibitor H2 | 3.1 | (Hamm et al., 2008) | |

| A2M | Alpha-2-macroglobulin | 3.3 | (Lindner et al., 2010) | |

| Cellular growth/survival | HSP90AA1 | Heat shock protein HSP 90-alpha | 2.0 | (Chu et al., 2013) |

| SERPINE1 | Plasminogen activator inhibitor | 1.8 | (Gomes-Giacoia et al., 2013) | |

| HSPA8 | Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein | 1.6 | (Rohde et al., 2005) | |

| HSP90AB1 | Heat shock protein HSP 90-beta | 1.5 | (Haase and Fitze, 2015) | |

| Oxidative stress response | GSTP1 | Glutathione S-transferase P | 3.3 | (Kanwal et al., 2014) |

| HPX | Hemopexin | 2.9 | (Tolosano and Altruda, 2002) | |

| HBA1 | Hemoglobin subunit alpha | 2.7 | (Li et al., 2013c) | |

| Prognosticator of survival | ALB | Serum albumin | 4.3 | (Gupta and Lis, 2010) |

| AFP | Alpha-fetoprotein | 3.1 | (Li et al., 2013a)* | |

| Immune response | PTX3 | Pentraxin-related protein PTX3 | 4.1 | (Bonavita et al., 2015) |

| C4A | Complement C4-A | 2.7 | (Pio et al., 2013) | |

| Cellular invasion | ANXA1 | Annexin A1 | 4.7 | (Cheng et al., 2012) |

| ANXA2 | Annexin A2 | 3.3 | (Lokman et al., 2013) | |

| Estrogen-induced malignancy | SERPINA7 | Thyroxine-binding globulin | 4.7 | (Doe et al., 1967) |

| Angiogenesis | APOB | Apolipoprotein B-100 | 3.9 | (Avraham-Davidi et al., 2012)* |

| Apoptosis | POTEF | POTE ankyrin domain family member F | 2.6 | (Liu et al., 2009) |

| Iron transport | TF | Transferrin | 2.5 | (Kovac et al., 2011) |

Rsc: Protein abundance ratio (HEY Oct4A KD2/HEY vector control).

Proposed protein functions of differentially expressed HEY Oct4A KD xenograft tumor proteins

Down regulated xenograft tumor proteins in HEY Oct4A KD samples

A total of 72 proteins were differentially suppressed in xenograft tumors derived from HEY Oct4A KD cells when compared to xenograft tumour samples derived from HEY vector control cells (Fig. 1). The increased number of proteins identified to be decreased in tumor xenograft samples resulted in an extensive list of protein function categories. Proteins which fit into the categories of cellular growth, cellular invasion, drug resistance, apoptosis, cytoskeletal and CSCs were identified as the most frequently down regulated proteins in HEY Oct4A KD tumor xenograft samples. This was followed by proteins which were involved in cellular adhesion, EMT, cellular metabolism and tumor suppression. The most down regulated protein identified in HEY Oct4A KD xenograft tumor samples was the cytoskeleton-associated protein TUBB2A (Rsc −78.1). This was followed by the cellular adhesion-associated proteins FN1 (Rsc −57.2) and FN cleaved into Anastellin (Rsc −55.4). Other down regulated proteins of interest in tumor xenografts derived from HEY Oct4A KD cells included the CSC-associated proteins CD109 antigen (CD109) (Rsc −12.8) and Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit beta (PDHB) (Rsc −11.9), the EMT-related proteins Transforming growth factor-beta-induced protein (TGFβ1) (Rsc −12.8) and Plastin-3 (PLS3) (Rsc −4.7), the cellular adhesion-associated proteins integrin-linked protein kinase (ILK) (Rsc −5.6) and intergin alpha-2 (ITGA2) (Rsc −2.9), the cellular migration and invasion-associated proteins PLEC (Rsc −3.2), (VIM) (Rsc −2.3) and Annexin 6 (ANXA6) (Rsc −2.9) and the angiogenesis-related protein Thioredoxin Reductase 1 (TXNRD1) (Rsc −4.7). Down regulated xenograft related proteins and their proposed cancer-related classifications are listed in Table 6 and summarised in Fig. 3b.

Table 6. Down regulated proteins in HEY Oct4A KD tumor xenografts.

| Category | Gene Name | Protein Description | Rsc | *Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular growth | BCAT1 | Branched chain amino acid aminotransferase | -10.1 | (Wang et al., 2015b) |

| PPP1CB | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP1-beta subunit | -7.4 | (Velusamy et al., 2013) | |

| MTHFD1L | Monofunctional C1-tetrahydrofolate synthase | -5.6 | (Tedeschi et al., 2013) | |

| RPL13 | 60S ribosomal protein L13 | -4.7 | (Kobayashi et al., 2006) | |

| CAP1 hCG_2033246 | Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein | -4.6 | (Hua et al., 2015) | |

| TMPO (LAP2) | Lamina-associated polypeptide 2, isoform alpha Thymopoietin isoform alpha | -3.2 | (Brachner and Foisner, 2014) | |

| CLTC | Calathrin heavy chain 2 | -2.7 | (McMahon and Boucrot, 2011) | |

| HSPA1A | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 1A/1B | -1.3 | (Wu et al., 2012) | |

| HSP90AB1 | Heat shock protein HSP 90-beta | -1.3 | (Haase and Fitze, 2015) | |

| PABPC4 | Poly(A) binding protein 4 | -1.3 | (Katzenellenbogen et al., 2010) | |

| HIST1H2BD | Histone H2B type 1-D | -1.3 | (Maruyama et al., 2014) | |

| Cellular invasion | PDLIM1 | LIM domain protein 1 | -10.1 | (Liu et al., 2015c) |

| FAM49B | Protein FAM49B | -7.6 | (Sung et al., 2014) | |

| DPYSL3 | Dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 3 | -6.5 | (Hiroshima et al., 2013) | |

| GNAI3 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G subunit alpha 3 | -4.7 | (Zhang et al., 2015)* | |

| PLEC | Plectin | -3.2 | (Katada et al., 2012) | |

| ANXA6 | Annexin A6 | -2.9 | (Sakwe et al., 2011)* | |

| CA3 | Carbonic anhydrase 3 (EC 4.2.1.1) (Carbonic anhydrase III) (CA-III) | -1.7 | (Dai et al., 2008a) | |

| ANXA2 | Annexin A2 | -1.6 | (Lokman et al., 2013) | |

| ALDOA | Fructose-bisphosphate aldotase A | -1.4 | (Sun et al., 2014) | |

| ANXA1 | Annexin A1 | -1.4 | (Cheng et al., 2012) | |

| FKBP1A | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | -1.1 | (Fong et al., 2003) | |

| Drug resistance | CAPN2 | Calpain-2 | -9.1 | (Storr et al., 2012) |

| DYNC1H1 | Cytoplasmic dynein 1 heavy chain 1 | -8.5 | (Huang et al., 2014) | |

| PSMD1 | 26S proteasome regulatory subunit RPN2 | -7.4 | (Honma et al., 2008) | |

| PRKDC | DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit | -3.9 | (Helleday et al., 2008) | |

| TGM2 | Protein -glutamine gamma-glutamyltransferase 2 | -2.7 | (Cao et al., 2008) | |

| HMGB1 | High mobility group protein B1 | -1.7 | (Huang et al., 2012a) | |

| PEBP1(RKIP) | Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein 1 | -1.7 | (Liu et al., 2015a) | |

| MDH2 | Malate dehydrogenase | -1.5 | (Lo et al., 2015) | |

| HSP90AA1 | Heat shock protein HSP 90-alpha | -1.3 | (Chu et al., 2013) | |

| Apoptosis | RLI | RNase L inhibitor | -8.1 | (Li et al., 2014b) |

| SLC25A6 | ADP/ATP translocase 3 (ANT3) | -7.4 | (Yang et al., 2007) | |

| LRPPRC | Leucine-rich PPR motig containing protein | -5.1 | (Zhou et al., 2014)* | |

| SMC3 | Structural maintenance of chromosome 3 | -4.7 | (Ghiselli, 2006)* | |

| COPA | Coatomer subunit alpha | -4.6 | (Sudo et al., 2010)* | |

| MAGED2 | Melanoma-associated antigen D2 | -3.8 | (Tseng et al., 2012)* | |

| NT5E (CD73) | 5′-nucleotidase | -1.3 | (Zhi et al., 2010)* | |

| Cancer stem cells | CD109 | Cluster of differentiation 109 | -12.8 | (Emori et al., 2013) |

| PDHB | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit beta | -11.9 | (Anderson et al., 2014) | |

| ALDH18A1 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase family 18 member A1 | -3.8 | (Buijs et al., 2012) | |

| NES hCG_1999207 | Nestin isoform CRA | -1.1 | (Neradil and Veselska, 2015) | |

| Cytoskeletal | TUBB2A | Tubulin beta-2A chain | -78.1 | (McCarroll and Kavallaris, 2012) |

| CD2AP | Adaptor protein CMS | -6.5 | (Lynch et al., 2003) | |

| TUBB4A | Tubulin beta 4 A chain | -1.9 | (McCarroll and Kavallaris, 2012) | |

| TUBB5 | Tubulin beta 5 chain | -1.7 | (McCarroll and Kavallaris, 2012) | |

| Cellular adhesion | FN1 FN | Fibronectin (Cleaved into: Anastellin) | -55.4 | (Mercurius and Morla, 2001) |

| ILK | Integrin-linked protein kinase | -5.6 | (Wang and Basson, 2009) | |

| ITGA2 | Integrin alpha-2 | -2.9 | (Van Slambrouck et al., 2009) | |

| Cellular metabolism | HIST2H2BE | Histone H2B type 2-E | -46.3 | (Dai et al., 2008b) |

| PFKP | Phosphofructo-1-kinase isozyme C | -10.1 | (Moon et al., 2011) | |

| YARS2 | Tyrosyl tRNA synthetase | -3.8 | (Riley et al., 2010) | |

| Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition | TGFB1 | Transforming growth factor-beta-induced protein | -12.8 | (Xu et al., 2009a) |

| HNRNPM | Heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein M | -5.8 | (Xu et al., 2014) | |

| PLS3 | Plastin-3 | -4.7 | (Sugimachi et al., 2014) | |

| Transcriptional regulation | RUVBL2 | RuvB-like 2 (EC 3.6.4.12) (48 kDa TATA box-binding protein-interacting protein) | -7.4 | (Flavin et al., 2011) |

| COPS7A | Signalosome subunit 7a | -5.6 | (Singer et al., 2014) | |

| HNRNPD | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D0 (hnRNP D0) (AU-rich element RNA-binding protein 1) | -1.5 | (Moore et al., 2014) | |

| DNA repair | RECQL | ATP-dependant DNA helicase Q1 | -11.0 | (Kawabe et al., 2000) |

| UBA1 | Ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 | -1.1 | (Moudry et al., 2012) | |

| Tumour suppression | MAP1B | Microtubule-associated protein 1B | -5.6 | (Lee et al., 2008)* |

| AHNAK | Desamoyokin | -3.5 | (Lee et al., 2014)* | |

| OGDH | 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase | -1.1 | (Tennant and Gottlieb, 2010) | |

| Angiogenesis | TXNRD1 | Thioredoxin reductase 1 | -4.7 | (Welsh et al., 2002) |

| AARS | Alanine tRNA ligase | -4.7 | (Mirando et al., 2015) | |

| Protein transport | VPS35 | Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 35 | -3.0 | (Seaman et al., 1997) |

| EEA1 | Early endosome antigen 1 | -2.2 | (Christoforidis et al., 1999) | |

| Extracellular matrix | FN1 | Fibronectin 1 Protein | -57.2 | (Singh et al., 2010) |

| Carcinogen detoxification | CYB5R3 | NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase 3 (Diaphorase-1) | -14.6 | (Kurian et al., 2006) |

| Immune Response | LTA4H | Leukotriene A-4 hydrolase | -10.6 | (Chen et al., 2004) |

| Cellular migration/motility | KTN1 | KTN1 protein (highly similar to Kinectin) | -5.6 | (Zhang et al., 2010b) |

| Unknown function | TMPO hCG_2015322 | Thymopentin isoform CRA_d | -2.7 | Peer reviewed information could not be found |

Rsc: Protein abundance ratio (HEY Oct4A KD2/HEY vector control).

Up regulated xenograft tumor proteins in HEY Oct4A KD samples

Thirty-nine proteins were identified to be differentially elevated in tumor xenografts derived from HEY Oct4A KD cells compared to tumors derived from HEY vector control cells. Xenograft proteins which were identified to have functional roles in cellular growth, cellular metabolism, apoptosis, tumor suppression and oxidative stress response were the most frequently up regulated in HEY Oct4A KD tumor xenografts. This was followed by proteins involved with the cytoskeleton, calcium homeostasis and drug resistance. The most up regulated protein identified in HEY Oct4A KD xenograft tumor samples was the apoptosis-associated protein POTEF (Rsc 23.0). Other up regulated tumor xenograft proteins identified to be of interest included the tumor suppression-related protein Alpha amylase (AMY2A) (Rsc 7.3), the cellular growth-associated protein Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A2 (EIF42A) (Rsc 5.9), the drug resistance-associated protein Collagen alpha 3 (VI) chain (COLGA3) (Rsc 3.7) and the cellular metabolism-related protein Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH2) (Rsc 2.5). Up regulated xenograft tumor proteins and their proposed cancer-related classifications are listed in Table 7 and summarised in Fig. 3b.

Table 7. Up regulated proteins in HEY Oct4A KD tumor xenografts.

| Category | Gene Name | Protein Description | Rsc | *Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular metabolism | GOT1 | Aspartate aminotransferase | 2.0 | (Lyssiotis et al., 2013) |

| PYGB | Phosphorylase (EC 2.4.1.1) | 1.5 | (Willmann et al., 2015) | |

| GOT2 | Glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase 2 | 1.1 | (Lyssiotis et al., 2014) | |

| IDH2 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase | 2.5 | (Borodovsky et al., 2012) | |

| ATP5O | ATP synthase subunit O | 1.3 | (Antoniel et al., 2014) | |

| Cellular growth | EIF42A | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A2 | 5.9 | (Modelska et al., 2015) |

| CKB | Creatine kinase B-type | 3.7 | (Li et al., 2013b) | |

| PCBP2 hCG_2017557 | Poly(RC) binding protein 2 | 1.3 | (Hu et al., 2014a) | |

| TOMM34 | Mitochondrial import receptor subunit TOM34 | 1.3 | (Shimokawa et al., 2006) | |

| Apoptosis | POTEF | POTE ankyrin domain family member F | 23.0 | (Liu et al., 2009 |

| HSPH1 | Heat shock protein 105 kDa | 1.5 | (Kennedy et al., 2014) | |

| HNRNPH3 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H3 | 1.4 | (Garneau et al., 2005) | |

| COMT | Catechol-O-methyltransferase | 1.1 | (Wu et al., 2015b) | |

| Tumour suppression | AMY2A | Alpha amylase | 7.3 | (Kang et al., 2010) |

| HBB | Mutant beta-globin | 1.9 | (Onda et al., 2005) | |

| KRBA2 | KRAB-A domain-containing protein | 1.7 | (Li et al., 2003) | |

| TPM1 | Tropomyosin-1 | 1.2 | (Bharadwaj and Prasad, 2002) | |

| Oxidative stress response | NUDT5 | ADP-sugar pyrophosphatase | 3.1 | (McLennan, 2006) |

| DNAJB11 | DnaJ homolog subfamily B member 11 | 1.3 | (Nakanishi et al., 2004) | |

| HBA1 | Alpha-globin | 1.2 | (Li et al., 2013c) | |

| KPNA3 | Karyopherin subunit alpha-3 | 1.0 | (Young et al., 2013) | |

| Cytoskeletal | NEB | Nebulin | 1.9 | (Pappas et al., 2011) |

| TPM2 | Tropomyosin-2 | 1.1 | (Assinder et al., 2010) | |

| Calcium homeostasis | ATP2A1 | Sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 1 | 5.6 | (Arbabian et al., 2011) |

| ATP2A2 | Sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2 | 4.1 | (Arbabian et al., 2011) | |

| Prognosticator of survival | ALB | Serum albumin | 3.7 | (Gupta and Lis, 2010) |

| HP | Haptoglobin (Zonulin) | 3.0 | (Zhao et al., 2007)* | |

| Drug resistance | COL6A3 | Collagen alpha-3(VI) chain | 3.7 | (Chen et al., 2013b) |

| TPI1 | Triosephosphate isomerase 1 | 1.0 | (Wang et al., 2008)* | |

| Iron transport | TF | Transferrin | 3.7 | (Kovac et al., 2011) |

| Angiogenesis | FMOD | Fibromodulin | 3.7 | (Jian et al., 2013) |

| Cancer stem cells | ANPEP | Aminopeptidase N | 1.1 | (Kim et al., 2012a) |

| mRNA regulation | NHP2L1 | NHP2-like protein 1 | 2.1 | (Esteller, 2011) |

| Cellular adhesion | PRELP | Prolargin | 2.0 | (Bengtsson et al., 2002) |

| Protein synthesis | RPS17L | 40S ribosomal protein S17 | 1.7 | (Chen and Roufa, 1988) |

| Immune response | FLNC | Filamin-C | 1.3 | (Marti et al., 1997) |

| Cellular migration/motility | BGN | Biglycan | 1.2 | (Hu et al., 2014b) |

Rsc: Protein abundance ratio (HEY Oct4A KD2/HEY vector control).

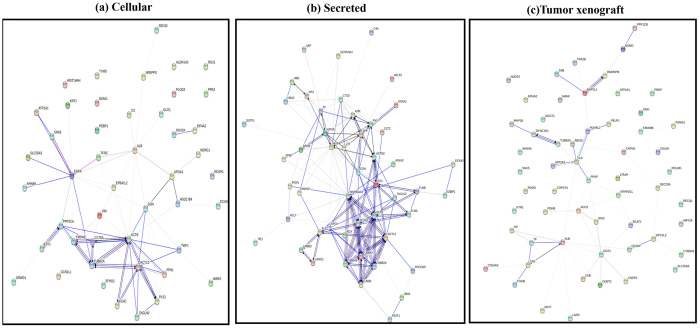

Proteome data network and pathway analysis

To identify protein networks and clusters associated with differentially expressed proteome profiles from HEY vector control and Oct4A KD cellular (41 significantly differentially expressed proteins), secretome (59 significantly differentially expressed proteins) and xenograft (57 significantly differentially expressed proteins), we performed protein-protein interaction analyses by STRING 10.033 (Fig. 4a–c). Several clusters of interacting proteins in vector control compared to Oct4A KD cells were observed, including focal adhesion, adheren junctions, cytoskeleton, extracellular region, and cell junction protein networks (Fig. 4a), while for the secretome several clusters of interacting proteins in vector control compared to Oct4A KD cells included regulation of actin cytoskeleton, focal adhesion, and tubulin protein networks (Fig. 4b). On the other hand, tumor xenograft samples included clusters of interacting proteins regulating metabolic processes (carboxylic acid, oxoacid, and carbohydrate), extracellular region, and cytoskeleton protein networks (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4. Protein interaction network analysis of secreted differentially expressed proteins.

Protein interaction network generated with STRING 10.0 for, (a) cellular, (b) secretome and (c) tumor xenograft and samples. Based on molecular high-confidence action and functional enrichments analysis, major clusters of interacting proteins include those involved in regulation of actin cytoskeleton, focal adhesion, and tubulin (secretome), focal adhesion, adherenes junctions, cytoskeleton, extracellular region, and cell junction protein networks (cellular), and metabolic processes (carboxylic acid, oxoacid, carbohydrate), extracellular region, and cytoskeleton (tumor xenograft).

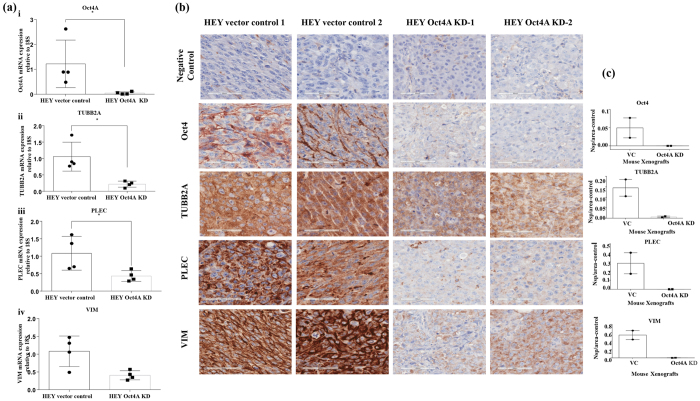

Validation of candidate proteins by RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry

To validate the expression of selected proteins from proteomic profiling between the HEY Oct4A vector control and HEY Oct4A KD populations, RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry were carried out on a subset of proteins (TUBB2A, PLEC, VIM) in Oct4A vector control and Oct4A KD cells and associated xenografts (Fig. 5a and b). The three proteins selected for validation were significantly down regulated in HEY Oct4A KD cells and KD-derived xenografts compared to vector control cells and associated xenografts (Suppl Table 1). These proteins were chosen as they have known significant role in cytoskeletal and ECM reprogramming of cancer cells (Suppl File 1).

Figure 5.

(a) Expression of Oct4A, TUBB2A, PLEC and VIM in HEY vector control and Oct4A KD cells. RNA from HEY vector control and HEY Oct4A KD cells was extracted, cDNA was prepared and RT-PCR was performed as described in the Materials and Methods. The resultant mRNA levels were normalized to 18S mRNA. Results are representation of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Significant variations between vector control and Oct4A KD cells was analysed by unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction using GraphPad Prism 7.02 and are indicated by *P < 0.05. (b) Expression of Oct4, TUBB2A, PLEC and VIM in mouse tumor xenografts generated by HEY vector control and Oct4A KD cells. Representative immunohistochemistry images of mouse xenografts for the expression of Oct4A, TUBB2A, PLEC and VIM. Images are set at 400x magnification and scale bar represents 60 μM (c) Variations in staining were determined by subtracting the negative control DAB readings number of strong positivity (Nsp)/area from the DAB readings of protein of interest for each xenograft. Data is presented as the mean ± SEM.

For RT-PCR analysis, the expression of Oct4A was significantly greater in HEY vector control compared to HEY KD cells (Fig. 5a). This elevated expression of Oct4A was consistent with the immunohistochemistry staining of det4in HEY Oct4A vector control compared to HEY Oct4A KD cell-derived xenografts (Fig. 5b). Consistent with that, RT-PCR analysis also showed consistent down regulation of TUBB2A, PLEC and VIM in HEY Oct4A KD compared to Oct4A vector control cell lysates (Fig. 5a). The down regulation of TUBB2A, PLEC and VIM in KD cell lysates was coherently observed in Oct4A KD cells-derived xenografts compared to vector control cell-derived xenografts. These validations of the differential expression of Oct4A, TUBB2A, PLEC and VIM at the mRNA and protein levels in cell lysates and the xenografts is in harmony with the comprehensive proteomics data demonstrated in this study.

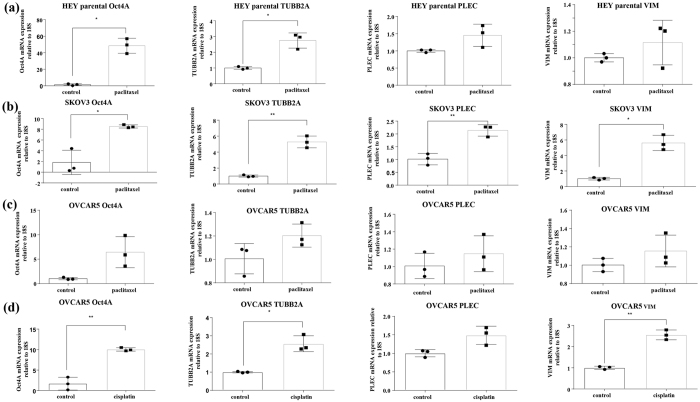

Functional association of Oct4A with TUBB2A, PLEC and VIM in drug resistance models

We have previously shown that the expression of Oct4/Oct4A is significantly enhanced in ovarian cancer cells in response to paclitaxel and cisplatin treatments3,4,27. In this study we demonstrate that the elevation of Oct4A at the mRNA level correlates with the enhancement in TUBB2A, PLEC and VIM expression in parental HEY, SKOV3 and OVCAR5 ovarian cancer cell lines in response to paclitaxel or cisplatin treatments (Fig. 6). This proof of concept observation consistently supports the functional association of Oct4A expression with key cytoskeletal/ECM associated proteins in ovarian cancer cell lines other than HEY cell line and suggests potential validity of this association in other tumor models.

Figure 6. Expression of Oct4A, TUBB2A, PLEC and VIM in parental HEY, SKOV3 and OVCAR5 cell lines in response to paclitaxel or cisplatin treatment.

(a) HEY, (b) SKOV3 and (c,d) OVCAR5 cell lines were treated with GI50 concentrations of paclitaxel or cisplatin for 72 hrs. RNA with and without paclitaxel or cisplatin treatments was extracted, cDNA was prepared and RT-PCR was performed as described in the Materials and Methods. The resultant mRNA levels were normalized to 18S mRNA. Results are representation of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Significant variations between treated and untreated cells (control) was analysed by unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction using GraphPad Prism 7.02 and are indicated by *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Discussion

We have previously demonstrated that suppression of Oct4A in the HEY cell line is sufficient to impact on OC tumorigenesis, metastasis and chemoresistance. Characteristics which were notably affected included cellular proliferation, adhesion, migration, invasion, increased sensitivity to chemotherapy treatment and overall decreased tumor initiating ability and metastasis in mouse models27,34. These diverse ranges of cellular traits affected by Oct4A knockdown strongly indicate direct or indirect regulation of Oct4A by signalling pathways and/or molecular mechanisms. In fact, clues as to how Oct4A influences these physiological changes within HEY cell line has come from previous observations that several markers associated with the CSC-like phenotype (Lin28, Sox2, CD44 and EpCAM), cellular adhesion and signalling integrins (α2, α5, α6, β1 and CD44), cellular invasion (Pro-MMP2), proliferation (Ki67), angiogenesis (CD31 and CD34) and survival (Bcl2 and GLUT1) were significantly impacted in HEY cells following knockdown of Oct4A expression27,34. However, these studies did not provide direct evidence of Oct4A specific proteome-mediated molecular mechanisms which influenced such an accumulative variety of biological processes. Therefore, we employed label-free MS-based proteomics to investigate the protein profiles between sample subsets (cell lysates and secretome and tumor xenografts) derived from HEY Oct4A KD and vector control cells to identify protein expression differences as a result of Oct4A regulation.

Overall, the data indicated Oct4A to be a key regulator of cytoskeleton/ECM remodelling besides its tumorigenic role that we have described previously27,34. Considering the extensive association of proteins identified, an effort was made to identify key proteins that regulate tumor-associated Oct4A traits in OC cells. Proteins which were consistently represented in the HEY Oct4A KD trait in each of the sample subsets were cytoskeleton proteins belonging to the tubulin, plakin and actin families. Of these TUBB2A, a member of the tubulin family and a major constituent of the cytoskeleton and critically involved in microtubule structure36 displayed concordant down regulation in the cellular (-42.9), xenograft (-78.1), and secretome (-8.0) subsets when Oct4A was down regulated. Besides TUBB2A, other members of tubulin family affected by Oct4A knockdown were TUBB6, TUBB2C, TUBB4A, TUBB4, TUBB5, which were prominently down regulated in Oct4A KD xenografts compared to xenografts derived from vector control cells.

More recently, TUBB2A has been described as having a role in regulating neuronal proliferation and migration37. Changes in β-tubulin isotype composition have been associated with tumor response to paclitaxel38,39 and increased tumor expression of β-tubulin II has been strongly associated with poor outcome in patients with head and neck carcinoma treated with docetaxel, a paclitaxel analogue40. Furthermore, increased TUBB2A expression has been correlated with decreased drug sensitivity in paclitaxel-resistant breast cancer cells41. This is consistent with our validation data which demonstrates a correlation of enhanced expression of TUBB2A with increased expression of Oct4A expression in paclitaxel or cisplatin treatment surviving resistant ovarian parental HEY, SKOV3 and OVCAR5 cell lines. Such evidence is also in agreement with our previous study, where we have demonstrated significant correlation between high Oct4A gene expression in recurrent OC patient’s ascites-derived tumor cells in response to treatment with a combination of cisplatin and paclitaxel compared to untreated (chemonaive) OC patient’s ascites derived tumor cells27.

Among other cytoskeleton proteins, PLEC a member of plakin family was significantly down regulated in Oct4A knockdown tumor xenograft and secretomes42. PLEC links the intermediate filament VIM with cytoplasmic organelles, and also provides stabilisation and links to nuclear envelope and centrosomes43. Increased PLEC and VIM expression, through PLEC-VIM complex has also been correlated to the migratory and invasive phenotypes in androgen-independent prostate and other cancers44,45,46. Loss of PLEC in HEY Oct4A KD cells coincides with the loss of VIM expression also seen in tumor xenografts. This is consistent with enhanced expression of PLEC and VIM in response to paclitaxel or cisplatin treatments in parental HEY, SKOV3 and OVCAR5 ovarian cell lines which coincided with elevated expression of Oct4A in these cells. This new finding adds novel clinical aspect of Oct4A regulation through key cytoskeletal and ECM proteins in the context of drug resistance, a major clinical hurdle for ovarian cancer patients.

The proteomic profiling of HEY Oct4A KD cells also demonstrated a loss of Mitogen activated protein kinase/Extracellular signal regulated kinase (MAPK/ERK) pathway in Oct4A knocked down tumor xenografts and secretomes. PLEC have been linked with MAPK/ERK pathway with respect to the migratory biology of keratinocytes and head and neck squamous cancer46,47. It was proposed that interaction of PLEC with MAPK/ERK pathway occurs due to interaction of PLEC with hemidesmosomal integrin α6β4, ligation of which by PLEC results in the activation of MAPK/ERK pathway48. Besides tubulin and plakins, actin-binding protein TAGLN2 involved with cancer cell motility and metastatic potential was also significantly decreased in HEY Oct4A KD samples49. These observations are consistent with decreased motility and metastatic potential of Oct4A KD cells that we have previously demonstrated27. On the other hand, actin-binding protein PLS1 and TWF1 involved with cell motility and mitotic division were significantly increased in HEY Oct4A KD samples. This increase in actin-binding PLS1 and TWF150,51 may occur to compensate the decrease in cytoskeleton tubulins, plakins and TAGLN. However, this compensatory increase may not provide requisite level of signals to initiate the migratory and metastatic potentials in the absence of Oct4A signals.

We have recently shown that suppression of Oct4A in HEY cell line resulted in the loss of αv and α2 family of integrins34. This observation is consistent with the proteomics data in the current study which showed a loss of αv and α2 family of integrins and integrin-linked kinase (ILK) in the secretomes and tumor xenografts derived from HEY Oct4A KD cells compared to vector control cells derived secretomes and xenografts. ILK has previously been shown to regulate mitotic cytoskeleton dynamics in retinoblastomas52. Consistent with that we see loss of Fibronectin (FN) and Laminin (LM) in the secretomes, and only loss of FN in the tumor xenografts derived from Oct4A KD cells compared to that derived from vector control cells. As FN and LM form important constituents of ovarian ECM and has significant roles in ovarian tumorigenesis53,54, it is likely that the loss of FN and LM in combination with cytoskeletal PLEC, VIM and integrins contributes to the loss of tumorigenic and invasive potential of Oct4A KD cells in mouse models as reported in our previous studies27.

Protein secretion by ovarian tumor cells has been shown to result in autocrine and paracrine signalling that defines cell growth, migration and the makeup of extracellular environment55. Secretion of PLEC in extracellular cyst fluid has been identified as a biomarker for the detection of early intra-ductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, a group of lesions with varying metastatic potential often detectable by CT scan56. PLEC expression increases during the development of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia, pre-cursor lesions of invasive and metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC)57. In addition, secretory form of PLEC makes an important component of exosomes of pancreatic cancer cells where it couples with α6β4 integrin58. In contrast, pericellular FN has also been shown to promote the metastasis of lung cancer cells by adhering to the cell surface receptor dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP IV)59. Hence, loss of secretory FN and PLEC in response to Oct4A KD may contribute to loss of migration, in vivo invasion and tumor development that we have reported previously34.

Proteins found to be up regulated in HEY Oct4A KD were primarily associated with cellular survival. These categories included cellular proliferation, lipid metabolism, cellular metabolism, cellular growth and oxidative stress. This included cytoskeleton (e.g. TWF1), cellular growth (EIF42A), cellular metabolism (IDH2) and oxidative stress (HBA1). Interestingly, despite the up regulation of these proteins, HEY Oct4A KD cells derived tumors displayed an overall reduced growth and tumorigenic potential in mouse models27,34. This may simply be due to the fact that up regulated proteins were not as strongly represented in HEY Oct4A KD samples compared to down regulated proteins. Logically, down regulated proteins may have a stronger influence on the phenotype of HEY Oct4A KD cells. However, it may also be that proteins which were up regulated are done as a compensatory mechanism for the stressful changes occurring in the overall phenotype of the HEY Oct4A KD cells. For instance, increased oxidative stress is a phenomenon shown to occur as a result to increased cellular metabolism60. Hence, cellular metabolism and oxidative stress proteins are strongly represented as up regulated in HEY Oct4A KD proteins. This may suggest oxidative stress response proteins are being produced to compensate the elevated cellular metabolism occurring in Oct4A KD cells to sustain their survival. An altered cellular metabolism has been shown to occur in CSCs61,62. However, it remains unclear why HEY Oct4A KD cells undergo increased cellular metabolism and requires further analysis. However, proteins which appear to be involved in cellular apoptosis (e.g. POTEF) and tumor suppression (APOA1) were also noted to be up regulated following Oct4A suppression. This indicates that there may be some strong influence of pro-survival mechanisms in HEY cells following suppression of Oct4A expression. However, the up regulated proteins involved with cellular apoptosis and tumor suppression may have positive implications in reducing tumor growth and survival of HEY cells and may support the reduced tumor growth observed previously in HEY Oct4A KD cells both in vitro and in vivo27,34.

Conclusion

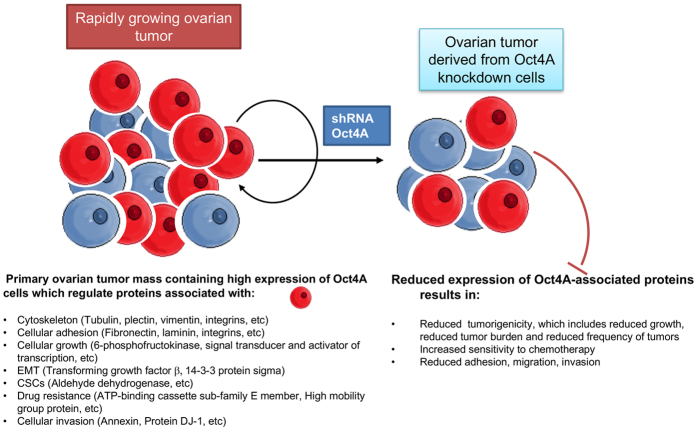

This study has for the first time identified the global proteome profile associated with Oct4A in ovarian cancer, targeting cellular, secretome and tumor xenograft subsets. These findings along with the validation of key cytoskeletal and ECM proteins (TUBB2A, PLEC, VIM) support the diminutive changes of proteins associated with cytoskeleton and ECM as major targets of Oct4A knockdown. In addition, gene/protein data using ICGC (International Cancer Genome Consortium, http://icgc.org), EBI Expression Atlas (http://www.ebi.ac.uk) and The Cancer Genome Atlas (https://gdc-portal.nci.nih.gov) which focused on ovarian tumors/tissues, suggest over expression of Oct4 in ovarian tumors. Furthermore, Oncomine (A Cancer Microarray Database and Integrated Data, https://www.oncomine.com/) indicates increased Oct4 gene expression (fold change 6.313) in ovarian tumors in comparison to normal ovarian tissues. Even though VIM/PLEC/TUBB2A demonstrated high expression in ovarian tumors (top 1%), no comparison with normal ovarian tissue exists in these databases so no enrichment/fold change can be indicated in tumors. These data support an association of Oct4A with cytoskeletal-ECM network, the key findings of this large-scale proteomics study. The attenuation of tumorigenic phenotype of HEY cells resulting from the knock down of Oct4A shown in our previous study further support these findings27,34.

These observations are sustained in drug resistant models where up regulation of Oct4A in paclitaxel or cisplatin treatment surviving residual parental HEY, SKOV3 and OVCAR5 cell lines correlated with the up regulation of TUBB2A, PLEC and VIM expression. This is consistent with the network pathway analyses which identified cytoskeleton and ECM proteins to be significantly diminished in the target subsets. However, network pathway analyses also identified clusters of proteins regulating glycolysis(Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), Lactate dehydrogenase live type A (LDHA), Phospho fructo-kinase (PFK), Pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH)) and (fatty acid synthesisFatty acid synthase (FASN)) to diminish in response to Oct4A knockdown. Overall, the protein changes observed are highly complex but the networks and results of this current proteomic analysis support the findings of our previous studies performed in vitro and in vivo13,27,34. The identified proteins described in this study have a strong implication in understanding Oct4A related functions in ovarian tumors in general and may apply in understanding Oct4A related functions in tumor models of other cancers. Based on this proteomic analysis a model of Oct4A regulation in ovarian carcinomas has been proposed in Fig. 7.

Figure 7. Proposed model of Oct4A regulation in ovarian carcinomas.

Ovarian tumors contain high expression of Oct4A which promotes ovarian tumorigenesis27. Knockdown of Oct4A in ovarian cancer cells results in the down regulation of major regulatory network of proteins including those involved with cytoskeleton-ECM remodelling, proliferation and cellular growth, EMT, CSCs, cellular adhesion, drug resistance and cellular invasion. This promotes the diminution of tumorigenic phenotypes which we have shown in our previous studies13,27,34.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

Animal ethics statement

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of the Laboratory Animals of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. The experimental protocol was approved by the Ludwig Institute/Department of Surgery, Royal Melbourne Hospital and University of Melbourne’s Animal Ethics Committee (Project-006/11), and was endorsed by the Research and Ethics Committee of Royal Women’s Hospital Melbourne, Australia.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Samardzija, C. et al. Knockdown of stem cell regulator Oct4A in ovarian cancer reveals cellular reprogramming associated with key regulators of cytoskeleton-extracellular matrix remodelling. Sci. Rep. 7, 46312; doi: 10.1038/srep46312 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

C.S. and R.E. are recipients of the Australian Postgraduate Award. N.A. is supported by June Wilson Will Trust, BJT Legal, Fiona Elsey Cancer Research Institute, Ballarat, Australia. D.G. is supported by the LIMS Molecular Biology Stone Fellowship, La Trobe University Research Focus Area Leadership Grant, and La Trobe University Start-up Fund. MC is supported by a La Trobe University Postgraduate Scholarship. This work was made possible through the Victorian State Government Operational Infrastructure Support to the Hudson Institute of Medical Research. We acknowledge the La Trobe University-Comprehensive Proteomics Platform for providing infrastructure and expertise for Protein Identification & Quantification. This work was supported by the funds received from Ovarian Cancer Research Foundation, Australia to N.A.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions C.S. designed and did the experiments, analysed the data and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. D.G. helped with the design of the experiments, analysed the data and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. R.L., R.E., M.B. and M.C. contributed to the experiments. J.K.F helped with the analyses of the data and edited the manuscript. G.K. edited the manuscript. N.A. conceived the idea, designed the study and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

References

- Prat J. Staging classification for cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 124, 1–5 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bapat S. A., Mali A. M., Koppikar C. B. & Kurrey N. K. Stem and progenitor-like cells contribute to the aggressive behavior of human epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 65, 3025–3029 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed N., Abubaker K. & Findlay J. K. Ovarian cancer stem cells: Molecular concepts and relevance as therapeutic targets. Mol Aspects Med. 39, 110–125 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abubaker K. et al. Short-term single treatment of chemotherapy results in the enrichment of ovarian cancer stem cell-like cells leading to an increased tumor burden. Mol Cancer 12, 24 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abubaker K. et al. Inhibition of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway in ovarian cancer results in the loss of cancer stem cell-like characteristics and a reduced tumor burden. BMC Cancer 14, 317 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster R., Buckanovich R. J. & Rueda B. R.: Ovarian cancer stem cells: working towards the root of stemness. Cancer Lett. 338, 147–157 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steg A. D. et al. Smoothened antagonists reverse taxane resistance in ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 11, 1587–1597 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulawka L., Donizy P. & Halon A. Cancer stem cells–the current status of an old concept: literature review and clinical approaches. Biol Res. 47, 66 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhartiya D. Stem cells, progenitors & regenerative medicine: A retrospection. Indian J Med Res. 141, 154–161 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang D. G. et al. Prostate cancer stem/progenitor cells: identification, characterization, and implications. Molecular Carcinogenesis 46, 1–14 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. Y. et al. Role of the IL-6-JAK1-STAT3-Oct-4 pathway in the conversion of non-stem cancer cells into cancer stem-like cells. Cell Signal. 25, 961–969 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H. et al. Role of the Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha induced autophagy in the conversion of non-stem pancreatic cancer cells into CD133 + pancreatic cancer stem-like cells. Cancer Cell Int. 13, 119 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samardzija C., Quinn M., Findlay J. K. & Ahmed N. Attributes of Oct4 in stem cell biology: perspectives on cancer stem cells of the ovary. J Ovarian Res. 5, 37 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. & Dai J. Concise review: isoforms of OCT4 contribute to the confusing diversity in stem cell biology. Stem Cells 28, 885–893 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeineddine D., Hammoud A. A., Mortada M. & Boeuf H. The Oct4 protein: more than a magic stemness marker. Am J Stem Cells 3, 74–82 (2014). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesce M. & Scholer H. R. Oct-4: gatekeeper in the beginnings of mammalian development. Stem Cells 19, 271–278 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santagata S., Ligon K. L. & Hornick J. L. Embryonic stem cell transcription factor signatures in the diagnosis of primary and metastatic germ cell tumors. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology 31, 836–845 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke S., Stephan M. & Kogler G. Oct4 expression revisited: potential pitfalls for data misinterpretation in stem cell research. Biol Chem. 389, 845–850 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer L. A. et al. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell 122, 947–956 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R. et al. Systems-level dynamic analyses of fate change in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature 462, 358–362 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck A. J. et al. Proteome Biology of Stem Cells. Stem cell research 1, 7–8 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larance M. & Lamond A. I. Multidimensional proteomics for cell biology. Nature reviews Molecular Cell Biology 16, 269–280 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poersch A. et al. A proteomic signature of ovarian cancer tumor fluid identified by highthroughput and verified by targeted proteomics. J Proteomics 145, 226–236 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama T. et al. Identification of IGFBP2 and IGFBP3 As Compensatory Biomarkers for CA19-9 in Early-Stage Pancreatic Cancer Using a Combination of Antibody-Based and LC-MS/MS-Based Proteomics. PLoS One 11, e0161009 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhaak L. R., van der Burgt Y. E. & Cobbaert C. M. Prospective applications of ultrahigh resolution proteomics in clinical mass spectrometry. Expert Rev Proteomics (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed N. et al. Unique proteome signature of post-chemotherapy ovarian cancer ascites-derived tumor cells. Sci Rep. 6, 30061 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samardzija C. et al. A critical role of Oct4A in mediating metastasis and disease-free survival in a mouse model of ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer 14, 152 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji H. et al. Proteome profiling of exosomes derived from human primary and metastatic colorectal cancer cells reveal differential expression of key metastatic factors and signal transduction components. Proteomics 13, 1672–1686 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greening D. W. et al. Secreted primary human malignant mesothelioma exosome signature reflects oncogenic cargo. Sci Rep. 6, 32643 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauro B. J. et al. Comparison of ultracentrifugation, density gradient separation, and immunoaffinity capture methods for isolating human colon cancer cell line LIM1863-derived exosomes. Methods 56, 293–304 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauro B. J. et al. Two distinct populations of exosomes are released from LIM1863 colon carcinoma cell-derived organoids. Mol Cell Proteomics 12, 587–598 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini YaH Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B-Stat Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Jensen L. J. et al. STRING 8–a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Research 37, D412–416 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samardzija C. et al. Coalition of Oct4A and beta1 integrins in facilitating metastasis in ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer 16, 432 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge K., Have S. T., Hutton L. & Lamond A. I. Cleaning up the masses: exclusion lists to reduce contamination with HPLC-MS/MS. J Proteomics 88, 92–103 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]