Abstract

Aging is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, which leads to a decline in cellular function and the development of age-related diseases. Reduced skeletal muscle mass with aging appears to promote a decrease in mitochondrial quality and quantity. Moreover, mitochondrial dysfunction adversely affects the quality and quantity of skeletal muscle. During aging, physical exercise can cause beneficial adaptations to cellular energy metabolism in skeletal muscle, including alterations to mitochondrial content, protein, and biogenesis. Here, we briefly summarize current findings on the association between the aging process and impairment of mitochondrial function, including mitochondrial biogenesis and reactive oxygen species in skeletal muscle. We also discuss the potential role of exercise in the improvement of aging-driven mitochondrial dysfunctions.

Keywords: aging, exercise, mitochondria, skeletal muscle

1. Introduction

Aging is associated with decreased skeletal muscle function and mitochondrial function, leading to a 25–30% reduction in functional capacity between ages 30 years and 70.1 This phenomenon can lead to decreased physical activity and can increase the risk of falls in aged individuals.2 Therefore, it is important to understand the mechanisms underlying aging-induced skeletal muscle atrophy in order to develop suitable therapeutic targets to promote health and mobility in the elderly.3 While many possible strategies have been suggested, the best target for the maintenance and improvement of cellular functions in aging is the mitochondria.4

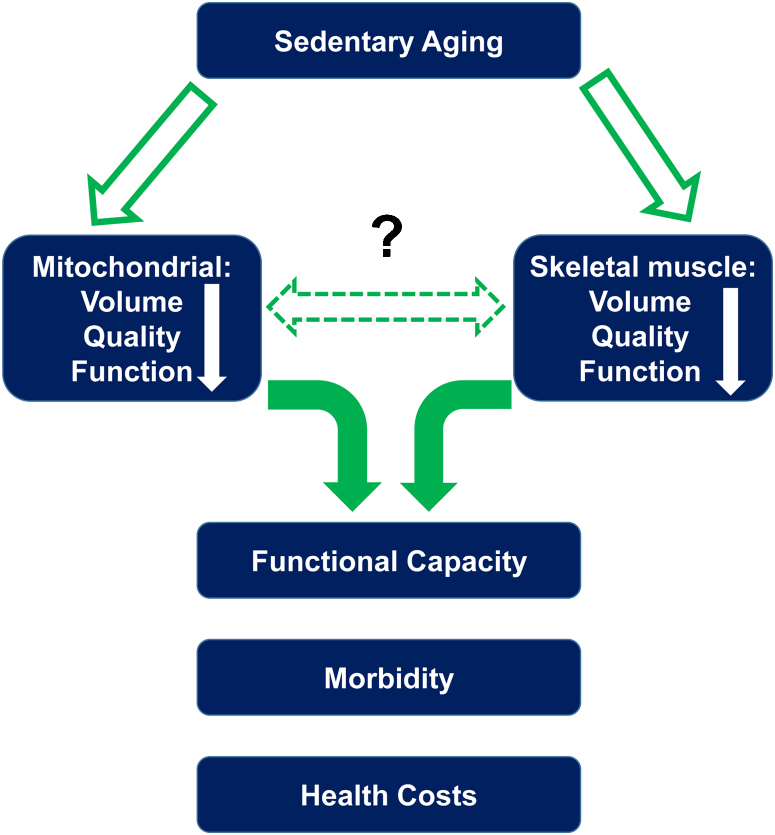

Mitochondria function as powerhouses of biological tissues to generate energy.5, 6 Mitochondrial dysfunction in response to deterioration of skeletal muscle with aging alters the structure and function of organelles (Fig. 1).7 Although studies have described age-related mitochondrial dysfunction in skeletal muscle, the relationships among aging, exercise type, and healthy mitochondria have not been clearly elucidated. Furthermore, alleviation of mitochondrial dysfunction in skeletal muscle following physical activity is an important aspect affecting the contributions of mitochondria to the aging processes in skeletal muscle.

Fig. 1.

The effects of sedentary aging.

Note. From “Mitochondrial and skeletal muscle health with advancing age” by Adam R. Konopka, K. Sreekumaran Nair, 2013, Mol Cell Endocrinol, 379, p. 19–29. Copyright 2016, https://s100.copyright.com/CustomerAdmin/PLF.jsp?ref=a1ee97ca-af28-4e18-867c-413e399da8a7. Reprinted with permission.

Exercise training modulates skeletal muscle metabolism by controlling intracellular signaling pathways that mediate mitochondrial homeostasis.8, 9 In order to reduce or prevent skeletal muscle weakness that occurs with aging, it is necessary to understand exercise-mediated mitochondrial adaptations, in skeletal muscle in particular. These regulate mitochondrial activities and coordinate mitochondrial signaling pathways. Moreover, the potential therapeutic benefits of exercise training are likely to be associated with the suppression of aging-related mitochondrial dysfunction.

In this review, we briefly introduce the role of exercise on the modulation of aging-driven mitochondrial dysfunction in skeletal muscle.

2. Mitochondrial metabolism

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is an important promoter of cell differentiation, growth, and reproduction, supplying energy for the contraction of muscles for physical activity.10, 11 Mitochondria are master sensors of metabolic and cellular processes and function to regulate energy (ATP) production through several enzymatic pathways, including the tricarboxylic acid cycle, oxidative phosphorylation, and fatty acid β-oxidation. The tricarboxylic acid cycle oxidizes acetyl-CoA to produce nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and flavin adenine dinucleotide, which can be used by the oxidative phosphorylation system to generate ATP.12

3. Age-related changes in the mitochondria in skeletal muscle

During aging, there are significant changes in mitochondrial ultrastructure and subcellular localization in skeletal muscle. The mitochondria of aged skeletal muscle appear enlarged and more rounded in shape, with matrix vacuolization and shorter cristae when compared with mitochondria from young skeletal muscle. Moreover, mitochondrial dysfunction is thought to be closely related to the loss of skeletal muscle mass during aging.13 Many studies have reported that a decline in organelle numbers such as loss of mitochondria content may induce loss of skeletal muscle. For example, reduced enzymatic activities (e.g., citrate synthase and cytochrome oxidase activities),14 protein markers, and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) content combined with electron micrographic evidence of decreased intermyofibrillar mitochondrial size and reduced thickness of the subsarcolemmar mitochondrial layer are easily observed in mitochondria from aged muscle. This results in impairment of mitochondrial metabolism, including the maximal ATP production rate, mitochondrial protein synthesis, and respiration, partly as a result of increased uncoupling of oxygen consumption and ATP synthesis.4 However, increased physical activity has been shown to be associated with a decrease in age-related deficits in mitochondrial function.15 Therefore, increased physical activity is important to maintain mitochondrial function in aging skeletal muscle.

3.1. Mitochondrial biogenesis

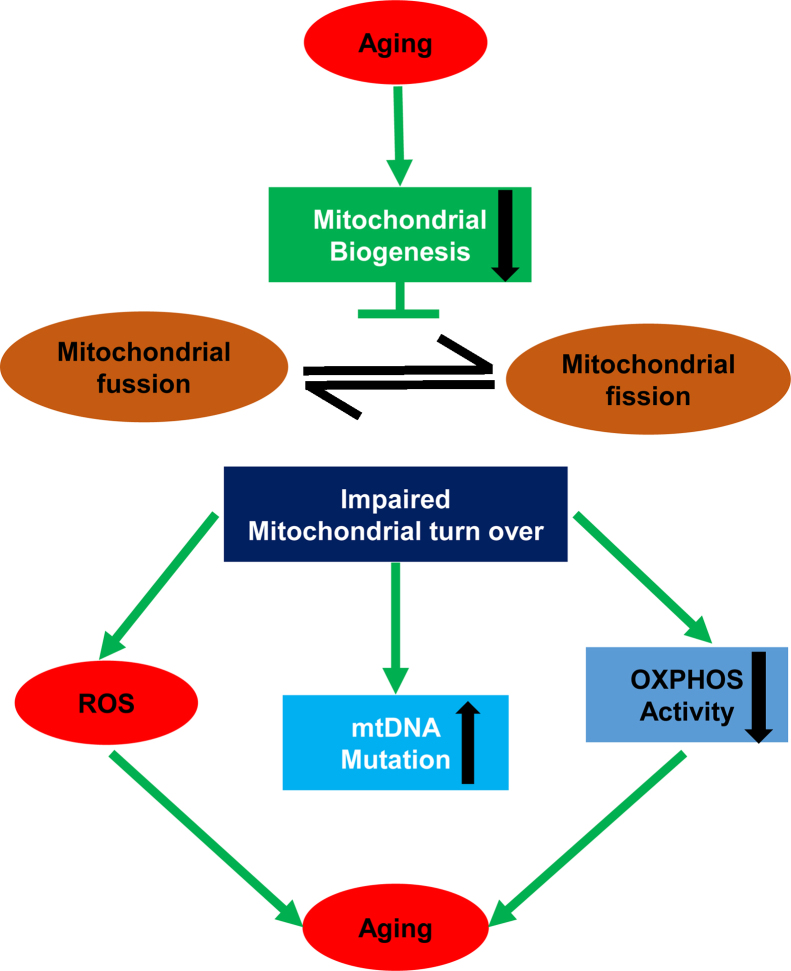

Cellular senescence contributes to aging-related disorders and reduces mitochondrial biogenesis, which drives homeostasis.16 Dysregulation of mitochondrial biogenesis has been shown to reduce the risk of decreased organ function associated with aging.17 Mitochondrial biogenesis plays a role in transcriptional regulation by mediating regulatory factors such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-g coactivator 1α, and downstream transcription factors such as nuclear respiratory factors 1 and 2 and mitochondrial transcription factor A.18, 19 Enhancement of mitochondrial biogenesis can be achieved not only through pharmacological intervention,20 but also through exercise; therefore, exercise may inhibit mitochondrial dysfunction and thereby ameliorate age-related complications. In 1967, John Holloszy21 first reported that exercise training improves mitochondrial biogenesis in aging skeletal muscle. Indeed, endurance treadmill exercise enhances mitochondrial protein and enzymes in skeletal muscle. Thus, from a practical standpoint, modulation of mitochondrial biogenesis capacity during aging may be applicable as an alternative method for lessening age-related complications (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mitochondria biogenesis in aging.

Note. From “Regulation of SIRT1 in aging: Roles in mitochondrial function and biogenesis” by Yujia Yuan, Vinicius Fernandes Cruzat, Philip Newsholme, Jingqiu Cheng, Younan Chen, Yanrong Lu, 2016, Mech Ageing Dev, 155, p. 10–21. Copyright 2016, https://s100.copyright.com/CustomerAdmin/PLF.jsp?ref=49996877-41b8-4243-b610-53e2aa846bff. Reprinted with permission.

OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

3.2. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation

In skeletal muscle, increased exposure or modulation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) with aging reflects fundamental changes in redox signaling.22 Skeletal muscle shows a significant age-related increase in oxidative damage. Thus, aged skeletal muscle is vulnerable to oxidative damage to DNA, lipids, and proteins.23 Recently, some scientists have emphasized the importance of mitochondrial ROS in skeletal muscle, demonstrating that excessive production of mitochondrial ROS is strongly associated with sarcopenia and the impairment of mitochondrial energy metabolism.24 Accumulation of ROS derived from the electron transport chain in aging results in mutations in mitochondrial DNA.25 To prevent age-related decline in skeletal muscle, some studies have focused on targeting the mitochondria. It is widely suggested that exercise training may reduce mitochondrial ROS because exercise can increase the antioxidant capacity in muscles.26, 27

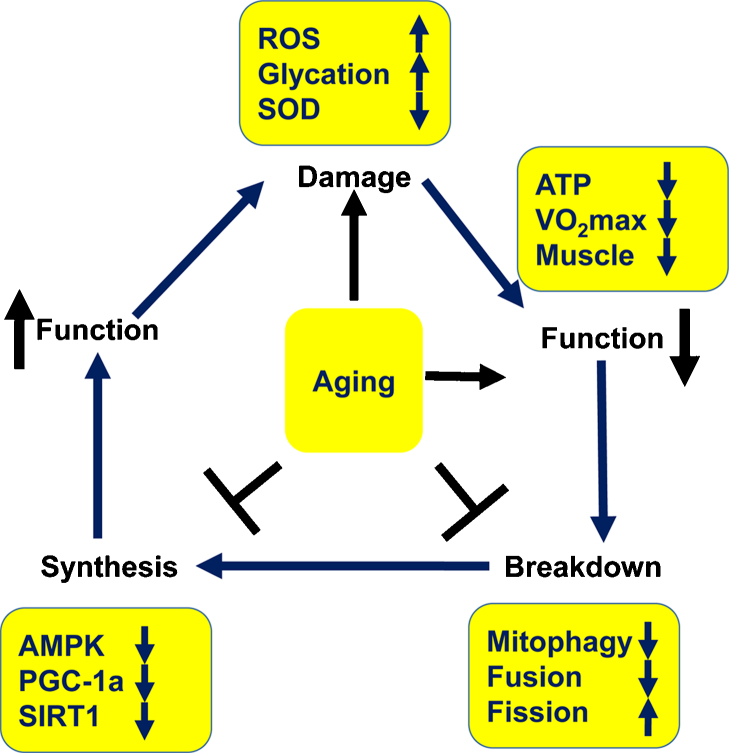

3.3. Mitochondrial protein degradation

Imbalanced redox status, cell death, and reduced mtDNA integrity have been shown to lead to mitochondrial degradation during muscle aging.28 Damaged mitochondria can be removed by the autophagy-lysosome and ubiquitin-proteasome pathways (Fig. 3).29 The accumulation of ROS in mitochondria can trigger mitophagy through the autophagy-lysosome pathway, resulting in removal of damaged mitochondria.30 The overexpression of mitophagy-related proteins including ATG5, ATG7, and LC3B, which are major components of the autophagy system, can facilitate the reduction of ROS-induced damage in cell culture.31 However, it is unclear whether exercise training can influence the autophagic and mitophagic systems. Further studies are needed to elucidate the beneficial effects of exercise on mitochondrial degradation in aged skeletal muscle.

Fig. 3.

Mitochondrial changes in aging.

Note. From “Skeletal muscle aging and the mitochondrion” by Matthew L. Johnson, Matthew M. Robinson, K. Sreekumaran Nair, 2013, Trends Endocrinol Metab, 24. Copyright 2016, https://s100.copyright.com/CustomerAdmin/PLF.jsp?ref=5ee2ebdc-2005-4f44-9706-d53fb96db265. Reprinted with permission.

AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-g coactivator 1α; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SIRT1, sirtuin 1; SOD, superoxide dismutase, VO2 max, the maximum rate of oxygen consumption.

4. Exercise-mediated changes in mitochondria metabolism during aging

Exercise can stimulate the restoration of mitochondrial metabolism during aging and is recommended as an alternative approach to maintain mitochondrial content and capacity.4 Indeed, many scientists have suggested that exercise may prevent mitochondrial dysfunction in aging skeletal muscle.32, 33

Since the pioneering work by Holloszy21 many studies have demonstrated that exercise can improve mitochondrial biogenesis and increase the energy demands of active cells. Aerobic training, a representative strategy for stimulating oxidative capacity,34 has resulted in increased mitochondrial enzyme activity in human and animal models.35 Twelve weeks of treadmill training (speed 17.5 m/min, 10% grade, 45 min/d, 5 d/wk) augmented the synthesis of mitochondrial protein, including mitochondrial transcription factor A, cytochrome c, and mtDNA contents.36 Whole body exercise, with running at 60% of the maximal O2 uptake, improved mitochondrial protein quality control and biogenesis.37 Another study demonstrated that training at 80% peak O2 uptake effectively stimulated mitochondrial function, as evident by the increased mitochondrial enzyme activities and ATP production.38 These results suggest that enhancement of mitochondrial function is accompanied by mitochondrial biogenesis, including an increase in transcript levels of nuclear and mitochondrial genes, mitochondrial abundance, and mitochondrial transcription factor A. Moreover, the increased mitochondrial mass,39 protein synthesis,40 mitochondrial gene transcripts,41 and mitochondrial DNA copy number,42 are also suggestive of a link between mitochondrial function and exercise training.

It has been suggested that mtDNA mutations and their accumulation act as causative factors in the aging process.43, 44 It was recently found that endurance exercise could induce the translocation of tumor suppressor protein p53 to the mitochondria, stimulating the repair of mtDNA mutations, independent of mitochondrial polymerase gamma (a major mtDNA repair enzyme), and allow for mitochondrial biogenesis.45

Although it is generally accepted that exercise helps increase life expectancy and reduce the risk of chronic diseases, few studies have directly investigated whether exercise-induced mitochondrial adaptations can be reproduced using the same exercise training program in aged individuals. Based on several published studies, mitochondrial metabolism appears to be enhanced after 12–16 weeks of exercise training, independent of age, suggesting that older individuals (< 80 years of age) may adapt favorably to exercise training.4, 33 However, the precise exposure of exercise programs (i.e., aerobic vs. resistance vs. concurrent training) on mitochondrial and skeletal muscle function (ex vivo or in vivo) has yet to be determined and further studies are required to investigate these topics in aged individuals.

5. Concluding remarks

In the present review, we discussed age-related reductions in mitochondrial functions in skeletal muscle. Impairment of mitochondrial function can be ameliorated by exercise. However, additional studies are required to determine the influence of exercise training regimens (e.g., aerobic and resistance training), the effects of different muscle-loading paradigms (e.g., volume, workload, intensity, and duration), and the characteristics of older subjects (e.g., lifestyle factors, comorbidities) that may contribute to the success of a specific training program. Although many studies have suggested that the beneficial effects of exercise may be connected to stimulation of mitochondrial function, even in aging, more convincing findings and elucidation of the underlying mechanisms related to exercise-mediated control of mitochondrial homeostasis are urgently needed to increase the quality of life of elderly individuals and help such individuals to maintain a healthy lifestyle during aging.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea, and the funding was granted by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning of Korea (2015R1A2A1A13001900, 2011-0028925) and by the Ministry of Education of Korea (2010-0020224).

References

- 1.Power G.A., Dalton B.H., Rice C.L. Human neuromuscular structure and function in old age: A brief review. J Sport Health Sci. 2013;2:215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cano A. Physical activity and healthy aging. Menopause. 2016;23:477–478. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Granacher U., Hortobagyi T. Exercise to improve,mobility in healthy aging. Sports Med. 2015;45:1625–1626. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0405-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter H.N., Chen C.C., Hood D.A. Mitochondria, muscle health, and exercise with advancing age. Physiology (Bethesda) 2015;30:208–223. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00039.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McBride H.M., Neuspiel M., Wasiak S. Mitochondria: more than just a powerhouse. Curr Biol. 2006;16:R551–R560. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tryon L.D., Vainshtein A., Memme J.M., Crilly M.J., Hood D.A. Recent advances in mitochondrial turnover during chronic muscle disuse. Integr Med Res. 2014;3:161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konopka A.R., Sreekumaran Nair K. Mitochondrial and skeletal muscle health with advancing age. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;15:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russell A.P., Foletta V.C., Snow R.J., Wadley G.D. Skeletal muscle mitochondria: a major player in exercise, health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840:1276–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ketkar S., Rathore A., Kandhare A., Lohidasan S., Bodhankar S., Paradkar A. Alleviating exercise-induced muscular stress using neat and processed bee pollen: oxidative markers, mitochondrial enzymes, and myostatin expression in rats. Integr Med Res. 2015;4:147–160. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reichert M., Schaller H., Kunz W., Gerber G. The dependence on the extramitochondrial ATP/ADP-ratio of the oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria isolated by a new procedure from rat skeletal muscle. Acta Biol Med Ger. 1978;37:1167–1176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicholls D.G. Mitochondrial function and dysfunction in the cell: its relevance to aging and aging-related disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34:1372–1381. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nsiah-Sefaa A., McKenzie M. Combined defects in oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid beta-oxidation in mitochondrial disease. Biosci Rep. 2016;36:e00313. doi: 10.1042/BSR20150295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peterson C.M., Johannsen D.L., Ravussin E. Skeletal muscle mitochondria and aging: a review. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:194821. doi: 10.1155/2012/194821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ritov V.B., Menshikova E.V., Kelley D.E. High-performance liquid chromatography-based methods of enzymatic analysis: electron transport chain activity in mitochondria from human skeletal muscle. Anal Biochem. 2004;333:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun L.J., Zhang Y., Liu J.K. Exercise and aging: regulation of mitochondrial function and redox system. Sheng Li Ke Xue Jin Zhan. 2014;45:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reznick R.M., Zong H., Li J. Aging-associated reductions in AMP-activated protein kinase activity and mitochondrial biogenesis. Cell Metab. 2007;5:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker B.M., Haynes C.M. Mitochondrial protein quality control during biogenesis and aging. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ventura-Clapier R., Garnier A., Veksler V. Transcriptional control of mitochondrial biogenesis: the central role of PGC-1alpha. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:208–217. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seo D.Y., Lee S.R., Kwak H.B. Voluntary stand-up physical activity enhances endurance exercise capacity in rats. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;20:287–295. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2016.20.3.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thu V.T., Kim H.K., Long le T. NecroX-5 protects mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation capacity and preserves PGC1alpha expression levels during hypoxia/reoxygenation injury. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;20:201–211. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2016.20.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holloszy J.O. Biochemical adaptations in muscle. Effects of exercise on mitochondrial oxygen uptake and respiratory enzyme activity in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:2278–2282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muller F.L., Song W., Jang Y.C. Denervation-induced skeletal muscle atrophy is associated with increased mitochondrial ROS production. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R1159–R1168. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00767.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nabben M., Shabalina I.G., Moonen-Kornips E. Uncoupled respiration, ROS production, acute lipotoxicity and oxidative damage in isolated skeletal muscle mitochondria from UCP3-ablated mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807:1095–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchez-Roman I., Gomez A., Perez I. Effects of aging and methionine restriction applied at old age on ROS generation and oxidative damage in rat liver mitochondria. Biogerontology. 2012;13:399–411. doi: 10.1007/s10522-012-9384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Indo H.P., Davidson M., Yen H.C. Evidence of ROS generation by mitochondria in cells with impaired electron transport chain and mitochondrial DNA damage. Mitochondrion. 2007;7:106–118. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2006.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Figueiredo P.A., Ferreira R.M., Appell H.J., Duarte J.A. Age-induced morphological, biochemical, and functional alterations in isolated mitochondria from murine skeletal muscle. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:350–359. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.4.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erlich A.T., Tryon L.D., Crilly M.J., Memme J.M., Mesbah Moosavi Z.S., Oliveira A.N. Function of specialized regulatory proteins and signaling pathways in exercise-induced muscle mitochondrial biogenesis. Integr Med Res. 2016;5:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barazzoni R. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial protein metabolism and function in ageing and type 2 diabetes. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004;7:97–102. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200401000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson M.L., Robinson M.M., Nair K.S. Skeletal muscle aging and the mitochondrion. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2013;24:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lionaki E., Tavernarakis N. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial protein quality control in aging. J Proteomics. 2013;92:181–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dang J., Li J., Xin Q. Gene-gene interaction of ATG5, ATG7, BLK and BANK1 in systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015 doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broskey N.T., Greggio C., Boss A. Skeletal muscle mitochondria in the elderly: effects of physical fitness and exercise training. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:1852–1861. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Young J.C., Chen M., Holloszy J.O. Maintenance of the adaptation of skeletal muscle mitochondria to exercise in old rats. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1983;15:243–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uribe J.M., Stump C.S., Tipton C.M., Fregosi R.F. Influence of exercise training on the oxidative capacity of rat abdominal muscles. Respir Physiol. 1992;88:171–180. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(92)90038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seo D.Y., McGregor R.A., Noh S.J. Echinochrome A Improves Exercise Capacity during Short-Term Endurance Training in Rats. Mar Drugs. 2015;13:5722–5731. doi: 10.3390/md13095722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang C., Chung E., Diffee G., Ji L.L. Exercise training attenuates aging-associated mitochondrial dysfunction in rat skeletal muscle: role of PGC-1alpha. Exp Gerontol. 2013;48:1343–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koltai E., Hart N., Taylor A.W. Age-associated declines in mitochondrial biogenesis and protein quality control factors are minimized by exercise training. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;303:R127–R134. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00337.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chow L.S., Greenlund L.J., Asmann Y.W. Impact of endurance training on murine spontaneous activity, muscle mitochondrial DNA abundance, gene transcripts, and function. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2007;102:1078–1089. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00791.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Menshikova E.V., Ritov V.B., Fairfull L., Ferrell R.E., Kelley D.E., Goodpaster B.H. Effects of exercise on mitochondrial content and function in aging human skeletal muscle. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:534–540. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.6.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balagopal P., Schimke J.C., Ades P., Adey D., Nair K.S. Age effect on transcript levels and synthesis rate of muscle MHC and response to resistance exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280:E203–E208. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.2.E203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Short K.R., Vittone J.L., Bigelow M.L. Impact of aerobic exercise training on age-related changes in insulin sensitivity and muscle oxidative capacity. Diabetes. 2003;52:1888–1896. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.8.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cao X., Zhao Z.W., Zhou H.Y., Chen G.Q., Yang H.J. Effects of exercise intensity on copy number and mutations of mitochondrial DNA in gastrocnemus muscles in mice. Mol Med Rep. 2012;6:426–428. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei Y.H., Wu S.B., Ma Y.S., Lee H.C. Respiratory function decline and DNA mutation in mitochondria, oxidative stress and altered gene expression during aging. Chang Gung Med J. 2009;32:113–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weber K., Wilson J.N., Taylor L. A new mtDNA mutation showing accumulation with time and restriction to skeletal muscle. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:373–380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Safdar A., Khrapko K., Flynn J.M. Exercise-induced mitochondrial p53 repairs mtDNA mutations in mutator mice. Skelet Muscle. 2016;6:7. doi: 10.1186/s13395-016-0075-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]