Abstract

AMPA receptor (AMPAR) trafficking has emerged as a fundamental concept for understanding mechanisms of learning and memory as well as many neurological disorders. Classical conditioning is a simple and highly conserved form of associative learning. Our studies use an ex vivo brainstem preparation in which to study cellular mechanisms underlying learning during a neural correlate of eyeblink conditioning. Two stages of AMPAR synaptic delivery underlie conditioning utilizing sequential trafficking of GluA1-containing AMPARs early in conditioning followed by replacement with GluA4 subunits later. Subunit-selective trafficking of AMPARs is poorly understood. Here, we focused on identification of auxiliary chaperone proteins that traffic AMPARs. The results show that auxiliary proteins TARPγ8 and GSG1L are colocalized with AMPARs on abducens motor neurons that generate the conditioning. Significantly, TARPγ8 was observed to chaperone GluA1-containing AMPARs during synaptic delivery early in conditioning while GSG1L chaperones GluA4 subunits later in conditioning. Interestingly, TARPγ8 remains at the membrane surface as GluA1 subunits are withdrawn and associates with GluA4 when they are delivered to synapses. These data indicate that GluA1- and GluA4-containing AMPARs are selectively chaperoned by TARPγ8 and GSG1L, respectively. Therefore, sequential subunit-selective trafficking of AMPARs during conditioning is achieved through the timing of their interactions with specific auxiliary proteins.

Keywords: auxiliary subunits, classical conditioning, TARPγ8, GSG1L, AMPAR trafficking

1. Introduction

Postsynaptic regulation of AMPA receptor (AMPAR) trafficking has emerged as a fundamental concept for understanding mechanisms underlying learning and memory and a host of neurological disorders. Evidence indicates that interactions among specific scaffolding proteins and protein kinases with AMPARs determines their mobility, subcellular localization and function [1]. Our previous studies have lead to development of a two-stage model of AMPAR trafficking during a neural correlate of eyeblink classical conditioning in which GluA1-containing AMPARs are delivered to synapses early in conditioning and are later replaced by newly synthesized GluA4 subunits that underlie learned blink responses [2–5]. Evidence using siRNAs targeting GluA1 and GluA4 strongly supports our two-stage model [4]. Recently, we showed that GluA1 and GluA4 AMPAR subunits are sequentially delivered to synapses by selective interactions with the scaffolding proteins A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP) and kinase suppressor of Ras 1 (KSR1) that coordinate trafficking during classical conditioning [5]. We found that a key player in conditioning-dependent AMPAR trafficking is synapse-associated protein 97 (SAP97), a membrane-associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK). Our studies showed that SAP97 interacts with both AKAP and KSR1 protein complexes to coordinate the sequential delivery of GluA1-containing AMPARs followed by GluA4 subunits during acquisition of conditioned responses [5]. These findings suggest that SAP97 forms a molecular backbone that coordinates multiple scaffolding proteins and kinases for appropriately timed delivery of subunit-specific AMPARs. Since SAP97 is a common interacting protein for both GluA1 and GluA4, it is unclear what additional mechanisms guide synaptic delivery of receptors to achieve the subunit specificity that is observed. For this question, we focused on identification of auxiliary chaperone proteins implicated in AMPAR trafficking.

High-resolution proteomics analysis has revealed a diversity of AMPAR-associated proteins [1,6–8]. Consequently, a number of hypotheses for the function of these auxiliary proteins are supported: regulation of AMPAR gating kinetics, assembly/stoichiometry of subunit composition, surface trafficking, and synaptic stabilization [9–13]. While transmembrane AMPAR regulatory proteins (TARPs) and cornichon proteins (CNIHs) are prime candidates to serve as auxiliary chaperones, other proteins are also implicated such as GSG1L and CKAMP44 [1,7,14]. A proteomics analysis of native AMPAR protein complexes in rat brain revealed the intriguing finding that all four AMPAR subunits GluA1-4 share a common compliment of auxiliary proteins including CNIH-2/3 and TARPγ8 [7]. Activity-dependency of these associations was not assessed in that study. However, co-expression studies using HEK cells suggest that TARPγ8 prevents the association of CNIH-2 with non-GluA1 AMPARs thereby conferring subunit-specificity [10].

While signaling mechanisms that coordinate synaptic delivery of AMPARs during classical conditioning are compartmentalized by SAP97, the specific auxiliary protein chaperones that control subunit-selective trafficking of AMPARs have yet to be identified. For these studies, we used a neural analog of eyeblink classical conditioning generated from an isolated preparation of the pons from the turtle [2,4]. Brain tissue from turtles allows preservation of extensive neural networks in a dish for long periods required for cellular and molecular studies of learning. Instead of using a tone or airpuff as for behaving animals, stimulation of the auditory nerve (the “tone” conditioned stimulus, CS) is paired with the trigeminal nerve (the “airpuff” unconditioned stimulus, US) that results in the acquisition of neuronal discharge in the abducens nerve that represents a neural correlate or “fictive” blink conditioned response. Acquisition of conditioned responses occurs rapidly in about one hour. Synaptic delivery of GluA1- and GluA4-containing AMPARs has been extensively characterized and previously shown to underlie conditioned responses [2–5]. The findings from this study indicate that auxiliary protein TARPγ8 chaperones GluA1-containing AMPARs during synaptic delivery early in conditioning while GSG1L chaperones GluA4 subunits later in conditioning. These data suggest that sequential subunit-selective trafficking of AMPARs during classical conditioning is achieved through the timing of their interactions with specific auxiliary proteins.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and conditioning procedures

Freshwater pond turtles, Trachemys scripta elegans, of either sex were purchased from commercial suppliers and anesthetized by hypothermia until torpid and decapitated. All experiments involving the use of animals were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Brainstem preparations were transected at the levels of the trochlear and glossopharyngeal nerves and the cerebellum was removed as described previously leaving an isolated preparation of the pons [4]. The preparation was continuously bathed (2–4 ml/min) in physiological saline containing (in mM): 100 NaCl, 6 KCl, 40 NaHCO3, 2.6 CaCl2, 1.6 MgCl2, and 20 glucose, which was oxygenated with 95% O2/5% CO2 and maintained at room temperature (22–24°C) at pH 7.6. Suction electrodes were used for stimulation and recording of cranial nerves. The US was a twofold threshold single shock applied to the trigeminal nerve and the CS was a 100 Hz, 1 s train stimulus applied to the ipsilateral auditory nerve that was below threshold to evoke activity in the abducens nerve. Neural responses were recorded from the ipsilateral abducens nerve that innervates the extraocular muscles. The CS–US interval, the time between the CS offset and the onset of the US, was 20 ms. The intertrial interval between the paired stimuli was 30 s. One complete training session (C1) was composed of 50 CS–US presentations that lasted 25 min in duration, however, shorter periods of training were also used including 5 min (10 paired stimuli) and 15 min (30 stimuli). When two pairing sessions (C2) were applied, they were separated by a 30 min rest period in which there was no stimulation. Conditioned responses were defined as abducens nerve activity occurring during the CS that exceeded an amplitude of twofold above the baseline recording level. Naïve preparations were presented with no stimuli and remained in the bath for the same time period as experimental preparations. Tissue samples for analysis were comprised of the pons cut in half to retain the stimulated side and contains the pontine portion of the eyeblink cranial nerve circuitry.

2.2. Western blot and co-immunoprecipitation

Samples of the pons ipsilateral to the side of conditioning were homogenized in lysis buffer with a protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Protein samples were precleared with protein A/G-agarose beads and supernatants were incubated in the primary antibodies or nonspecific rabbit or mouse IgG as a control at 4°C for 2 h. Protein A/G-agarose beads were added to the protein samples and incubated at 4°C overnight. Immunoprecipitated samples or IgG control samples were washed with ice-cold lysis buffer and dissociated by heating for 5 min in loading buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE. The following primary antibodies were used for co-IPs and western blotting: TARPγ8 (Santa Cruz, 168395), GSG1L (Santa Cruz, 240539), GluA1 (Millipore, 1504), GluA4 (Santa Cruz, 7614) and β-actin for loading controls (Millipore, 1501R). Proteins were detected by the ECL Plus chemiluminescence system (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) and quantified by computer-assisted densitometry.

2.3. Biotinylation assay

To verify that surface delivery of TARPγ8 occurs with GluA1 and GluA4 shown previously [5], preparations were incubated in physiological saline containing 1 mg/ml EZ-link sulfo-NHS-LC biotin while in the naïve state or undergoing the conditioning procedure for the selected time period. The total elapsed time of incubation in the biotin did not exceed 2 h. At the end of the conditioning procedure, preparations were washed in ice-cold physiological saline and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissue samples were homogenized in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP40, 0.15 M NaCl, 10 mM Na4P2O7, 5% glycine) with a protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail, rotated at 4°C for 2 h, centrifuged at 14,000 g for 20 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were stored at −80°C. Biotinylated proteins were incubated with UltraLink Immobilized Streptavidin (Pierce) at 4°C overnight. Streptavidin–protein complexes were washed with ice-cold buffer and pellets were resuspended in 2× SDS/β-mercaptoethanol and boiled for 5 min before separation by 10% SDS–PAGE followed by western blotting.

2.4. Immunocytochemistry and confocal imaging

After the physiological experiments, preparations were immersion fixed in 0.5% paraformaldehyde. Tissue sections were cut at 30 μm and preincubated in 10% normal donkey serum. Alternate sections were either single or double labeled with primary antibodies to GluA1 and TARPγ8, or GluA4 and GSG1L overnight at 4°C with gentle shaking. The primary antibodies were the same as those used for western blots and co-IPs except for GluA4 (Millipore, 1508). After the primary antibodies, sections were rinsed and incubated with secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. The secondary antibodies were a Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000; Jackson ImmunoResearch) for GluA1 and GluA4, and a Cy2-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (1:100; Invitrogen) for TARPγ8 and GSG1L. Secondary antibodies were tested for lack of nonspecific binding by incubating sections in secondary alone. The sections were rinsed, mounted on slides and coverslipped. Images of labeled neurons in the principal and accessory abducens motor nuclei were obtained using an Olympus Fluoview 1000 laser scanning confocal microscope. Tissue samples containing abducens motor neurons were scanned using a 60× 1.4 NA oil-immersion objective with double excitation using a 543-nm HeNe laser and 635-nm diode laser.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with StatView software using a one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc analysis using a Fisher’s test. Values are presented as means ± SEM. Sample sizes (N) are represented by the number of brainstem preparations used in the experiments. P values are determined relative to the naïve group.

3. Results

3.1. Conditioning-dependent regulation of TARPγ8 and GSG1L protein expression

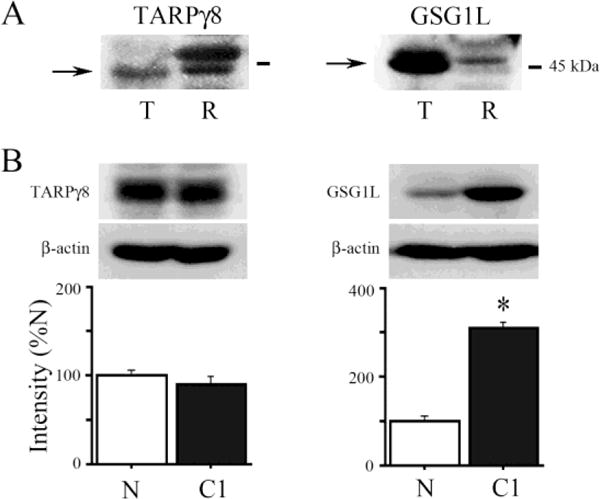

The TARPs are a family of highly conserved AMPAR auxiliary proteins having four membrane-spanning regions with a cytosolic N-terminus and cytosolic C-terminus that contains PDZ binding motifs [15]. Stargazin (γ2) is the best studied of the TARPs. The TARPγ 8 is a 43 kDa protein in which amino acid sequence alignment (Clustal W/X v. 2.0) shows an 86% similarity of turtle TARPγ8 compared to human. Antibodies to TARPγ8 identified a band at the appropriate molecular weight in turtle brain tissue while two bands are apparent in the rat (Fig. 1A). The recently identified AMPAR auxiliary protein GSG1L [7,14] also has four transmembrane segments with cytoplasmic N- and C-termini. Transcripts of GSG1L have two isoforms, long and short, with protein molecular weights of 43 and 37 kDa, respectively. Amino acid sequence alignment shows 78% similarity of GSG1L between the turtle and human. With the antibody used here, neither turtle nor rat brain tissue show a band at 37 kDa, however, both species show a prominent band near 43 kDa in western blots (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Regulation of auxiliary subunit protein expression in conditioning. (A) Western blots showing TARPγ8 and GSG1L bands from samples of turtle (T) and rat (R) brain tissue. (B) Analysis of auxiliary subunit protein expression in turtle tissue samples from naïve preparations (N) and those conditioned for one complete pairing session (C1; N = 5/group, *P < 0.0001).

Whether the expression of TARPγ8 and GSG1L auxiliary proteins are regulated during conditioning was examined by western blot analysis. Expression of TARPγ8 protein was not significantly affected by one session of conditioning (C1; 25 min duration) and was observed to be on average 86% of levels obtained in naïve unstimulated preparations (Fig. 1B; P = 0.18). On the other hand, expression of GSG1L was significantly increased to 304% above naïve values after conditioning (Fig. 1B; P < 0.0001). Therefore, both TARPγ8 and GSG1L auxiliary proteins are highly conserved and present in mature turtle brain, but only protein expression levels of GSG1L are regulated in a conditioning-dependent manner.

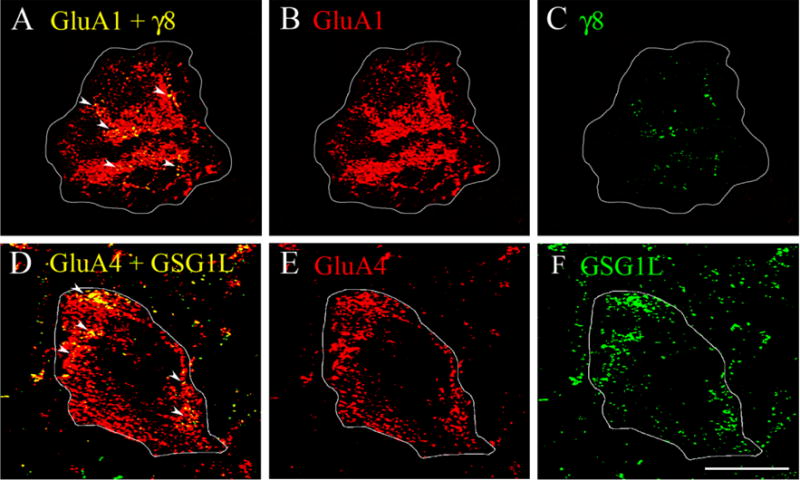

3.2. Colocalization of TARPγ8 and GSG1L with AMPARs in abducens motor neurons

Eyeblink responses in turtle are mediated by the abducens motor neurons that innervate the extraocular muscles controlling movements of the eye, nictitating membrane, and eyelid [16]. The abducens motor neurons receive direct monosynaptic inputs from both the trigeminal and auditory nerves that generate the unconditioned and learned eyeblink responses [17]. Here, we used immunocytochemistry and confocal imaging to determine whether TARPγ8 and GSG1L were localized to abducens motor neurons. Immunostaining showed extensive punctate labeling of abducens neurons for TARPγ8 and GSG1L. Moreover, double-labeling experiments revealed colocalization of these auxiliary proteins with AMPARs. Staining for GluA1-containing AMPARs (red) and TARPγ8 (green) in conditioned preparations showed individual puncta localized to abducens motor neurons and substantial colocalization of the two markers (yellow puncta; Fig. 2A–C). Similarly, staining for GluA4 AMPAR subunits (red) and GSG1L (green) in conditioned preparations showed the presence of individual puncta and clusters of colocalized labeling (Fig. 2D–F). These data indicate that not only are these specific auxiliary proteins localized to abducens motor neurons, but that they are colocalized with AMPARs after conditioning.

Fig. 2.

Confocal images of abducens motor neurons showing TARPγ8 colocalization with GluA1-containing AMPARs and GSG1L colocalization with GluA4-containing AMPARs. (A–C) Images from a preparation conditioned for one pairing session (C1) shows punctate staining for GluA1 (red), TARPγ8 (green) and colocalized staining in the merged image (yellow puncta). (D–F) Images from a preparation conditioned for two pairing sessions (C2) shows punctate staining for GluA4 (red), GSG1L (green), and colocalized staining (yellow puncta). Arrowheads indicate clusters of colocalized punctate staining. Scale bar = 10 μm.

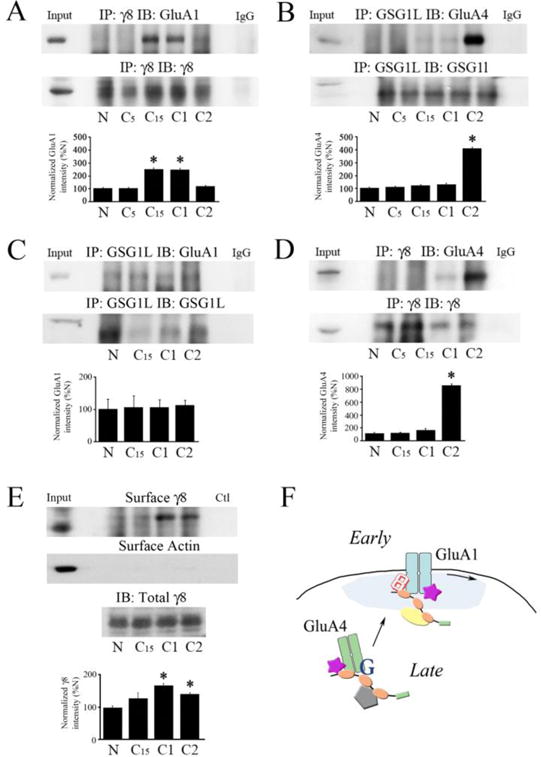

3.3. Differential trafficking of AMPAR subunits by auxiliary proteins during conditioning

Previous proteomics data suggested that TARPγ8 associated with GluA1 AMPAR subunits while GSG1L partnered with GluA4 subunits [7]. Given that AMPARs containing either of these two subunits are selectively trafficked during classical conditioning in our model system, we performed co-IP experiments to determine whether there was a conditioning-related association between these protein pairs. The results show that there was minimal association of GluA1-TARPγ8 or GluA4-GSG1L in naïve preparations or those conditioned for only 5 min (Fig. 3A–B). Significantly, however, after conditioning for 15 and 25 min (C15 and C1), the association of GluA1 and TARPγ8 was dramatically increased 250% above naïve values, as indicated in the co-IP and the quantitative data (Fig. 3A; P < 0.05, N vs. C15 and C1). This increase was not observed for co-IPs involving GluA4 and GSG1L at C15 and C1 (Fig. 3B). An association of GluA1 AMPAR subunits with TARPγ8 was confirmed by the immunocytochemistry of abducens motor neurons in which colocalization of GluA1-TARPγ8 was observed after one session of conditioning (Fig. 2A; yellow puncta indicated by the arrowheads). In contrast, after 80 min of conditioning or two pairing sessions (C2), a significant increase in GluA4-GSG1L immunoprecipitates over 400% above naïve values was observed (Fig. 3B; P < 0.0001, N vs. C2) while values for GluA1-TARPγ8 fell to undetectable levels (Fig. 3A). Correspondingly, colocalization of GluA4-GSG1L was observed in the immunostaining of abducens motor neurons (Fig. 2D). The converse co-IPs to those above were also run to investigate these potential interactions. Data for GSG1L-GluA1 showed only a weak interaction that was not conditioning-dependent (Fig. 3C; F(3,8) = 0.02, P = 0.99). Interestingly, co-IP of TARPγ8 with GluA4 showed no signal until two sessions of conditioning when this association became evident in the co-IPs (Fig. 3D; P < 0.001, N vs. C2). This corresponds with the time when GluA4-containing AMPARs are delivered to the synaptic surface during conditioning after GluA1 subunits have already been delivered by TARPγ8 [5] suggesting that TARPγ8 remains at the cell surface while GluA1-containing AMPARs are withdrawn. This interpretation is corroborated by biotinylation assays of surface TARPγ8. Detection of TARPγ8 at the membrane surface is first observed after 15 min of conditioning (Fig. 3E; P = 0.12) but is not significantly increased until one and two sessions of conditioning (Fig. 3E; P < 0.01, N vs. C1 and C2). These data indicate that GluA1- and GluA4-containing AMPARs are selectively chaperoned by TARPγ8 and GSG1L, respectively, during sequential synaptic delivery in abducens motor neurons during classical conditioning.

Fig. 3.

Conditioning-dependent trafficking of AMPARs by TARPγ8 and GSG1L. (A) Co-immunoprecipitation of TARPγ8 with GluA1 AMPAR subunits is detected after conditioning for 15 min (C15) and one complete pairing session (25 min, C1) but not in naïve preparations (N) or after conditioning for 5 min (C5). The signal declines later in conditioning after two pairing sessions (C2; N = 5/group, *P < 0.05 vs. N). Input (whole cell lysates from naïve) and control IgG lanes are also shown. (B) Co-immunoprecipitation of GSG1L with GluA4 subunits is strongly detected only in later stages of conditioning after two pairing sessions (C2; N = 5/group, *P < 0.0001 vs. N). (C) The interaction of GluA1 with GSG1L was weak and failed to show any changes with conditioning (N = 3/group, P = 0.99). (D) The interaction of GluA4 with TARPγ8 was strong after two pairing sessions when GluA4 is inserted into synapses (N = 3/group, *P < 0.001, N vs. C2). (E) Biotinylation experiments show that TARPγ8 is present at the membrane surface later in conditioning at C1 and C2 when AMPARs are delivered to synaptic sites (N = 3/group, *P < 0.01 vs. N). Surface actin from the same samples is also shown. Western blot of total TARPγ8 is from samples untreated with biotin. (F) Model of auxiliary protein-assisted two-stage trafficking of GluA1- and GluA4-containing AMPARs during conditioning. Existing GluA1 subunits are delivered to synaptic sites early in conditioning by a protein complex containing SAP97, AKAP, TARPγ2 (stargazin), and TARPγ8. Withdrawal of GluA1-containing AMPARs later in conditioning is followed by replacement by newly synthesized GluA4 subunits delivered by a complex containing SAP97, KSR1, stargazin, and GSG1L. Newly delivered GluA4-containing AMPARs associate with TARPγ8 that stays on the membrane surface. SAP97, symbol with orange ovals; AKAP, yellow oval; stargazin, purple star; TARPγ8, letter 8; KSR1, grey pentagon; GSG1L, letter G.

4. Discussion

The data shown here confirm in brain tissue from a non-mammalian vertebrate that TARPγ8 and GSG1L are highly conserved AMPAR auxiliary subunits. Moreover, this model system offers the unique opportunity to study subunit-specific trafficking of AMPARs by auxiliary subunits during associative learning. Significantly, we show that the association of these auxiliary proteins with AMPARs during trafficking is selective and activity-dependent. During a neural correlate of classical conditioning, TARPγ8 is part of the protein complex involved in synaptic delivery of GluA1 AMPAR subunits in early stages of conditioning while GSG1L forms a complex with GluA4 subunits in later stages of conditioning. Therefore, we show for the first time that specific auxiliary proteins are selectively associated with AMPARs during different stages of trafficking during classical conditioning. These data suggest that the subunit-specific trafficking of AMPARs observed in conditioning is achieved by the timing of their interactions with specific auxiliary chaperones.

4.1. Protein expression and localization of TARPγ8 and GSG1L in conditioning

Similar to rat, TARPγ8 was identified in turtle brain samples at ~43 kDa. Transcripts for GSG1L show two isoforms in which the shorter variant lacks the first 102 amino acids present in the long transcript. The molecular weight of the long protein isoform is ~43 kDa and was previously identified in rat brain [14] and in this study for rat and turtle. In rat, TARPγ8 protein levels were found to gradually increase throughout postnatal development whereas values for GSG1L were unchanged [8]. However, a genome-wide analysis in chick ciliary ganglion showed that GSG1L transcript levels increased during the period of embryonic synapse formation [18]. Here, GSG1L protein expression is activity-dependent and highly regulated during conditioning whereas TARPγ8 expression is unchanged by conditioning. These findings for GSG1L and TARPγ8 correspond with the increase in protein levels of newly synthesized GluA4 AMPAR subunits and the stable expression pattern of GluA1 subunits, respectively, during conditioning [3,19]. Importantly, immunostaining for both TARPγ8 and GSG1L is localized to abducens motor neurons in turtle that are the output of the pontine eyeblink reflex circuitry. These proteins are also present in brainstem samples obtained from adult rat brain [8].

4.2. TARPγ8 and GSG1L-mediated AMPAR trafficking in LTP

The TARPs and GSG1L are widely distributed in the mammalian brain and are localized at glutamatergic synapses in mammals [7–8,14,20]. In the mouse hippocampus, TARPγ8 and GSG1L are colocalized with the synaptic marker PSD-95 or to the PSD membrane [14,20]. Proteomic analysis indicates that TARPγ8 and GSG1L interact with AMPARs. Specifically, TARPγ8 associates with GluA1 AMPAR subunits while GSG1L partners with GluA4 [7]. Evidence indicates they each have a significant role in AMPAR synaptic trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Long-term potentiation in the hippocampal CA1 region was significantly impaired in TARPγ8-null mice [21–22]. Moreover, there was a substantial reduction in GluA1 and GluA2/3 protein expression as well as synaptically localized GluA1 in hippocampal spines [21]. A requirement for TARPγ8 in expression of hippocampal LTP in dentate gyrus granule cells was also confirmed by Khodosevich et al. [23]. These studies and others [24] suggested a preferential interaction between GluA1 AMPAR subunits and TARPγ8. It was further shown that CNIH-2/3 selectively regulates trafficking of GluA1-containing AMPARs in hippocampal synapses but that the presence of TARPγ8 regulates the activity of CNIH proteins on surface expression of AMPAR heteromers [10]. Questions remain, however, as to the effect of TARPγ8 knockout on protein expression levels of GluA1 and the effect of this loss on interpretations of mechanisms underlying GluA1 trafficking in LTP. More recently, GSG1L was validated as an AMPAR auxiliary subunit. Using transfected kidney cell lines (HEK cells), Shanks et al. [14] demonstrated co-IP of GSG1L with GluA1 and GluA2 AMPAR subunits, although GluA3–4 were not examined. Association with GSG1L increased surface expression of GluA2 in cotransfected HEK cells as well as slow GluA2 gating kinetics. In contrast to these findings, a recent study reported that GSG1L overexpression has a negative effect on AMPAR-mediated currents as well as surface expression of GluA1 in cultured hippocampal neurons [25]. Moreover, LTP in CA1 neurons was enhanced in GSG1L-null rats. Since these knockouts demonstrated no effect on AMPAR or TARPγ8 protein expression these data raise the question as to whether GSG1L traffics GluA1-containing AMPARs in hippocampal neurons. It is also unclear if there were any compensatory actions by other auxiliary trafficking proteins, particularly CNIH2, in the GSG1L knockouts. These studies and our own findings here raise further questions as to the function of GSG1L in AMPAR trafficking, particularly for GluA1.

4.3. Timing-dependent subunit-selective trafficking of AMPARs in classical conditioning

During a neural correlate of eyeblink classical conditioning, TARPγ8 traffics GluA1-containing AMPARs while GSG1L traffics GluA4 subunits to synapses. Significantly, we show that the timing of these interactions is dependent on the early or late stages of conditioning. That is, TARPγ8 strongly co-IPs with GluA1 after 15 and 25 (C1) min of conditioning and this interaction sharply declines later in conditioning after 80 min (C2). On the other hand, GSG1L interacts with GluA4 subunits in later stages of conditioning after 80 min. As described by Zheng and Keifer [5], the timing of these interactions corresponds to SAP97 complex formation with other scaffolding proteins and the surface expression of GluA1-containing AMPARs in early conditioning and surface GluA4 in later stages. As illustrated in Fig. 3F, during early conditioning a SAP97/AKAP/PKA complex forms and interacts with existing GluA1-containing AMPARs for delivery to the PSD. This complex also includes the AMPAR chaperone stargazin (TARPγ2) and, as shown here, TARPγ8. Later in conditioning, a SAP97/KSR1/PKC complex forms for synaptic delivery of newly synthesized GluA4 subunits. This complex also includes stargazin and GSG1L. Our previous work [5] showed that the interaction of stargazin with either GluA1 or GluA4 subunits was present in naïve preparations and remained stable throughout the conditioning procedure. Therefore, stargazin is unlikely to signal subunit specificity by itself. This study demonstrates that the interaction of TARPγ8 and GSG1L are unique to the GluA1 and GluA4 trafficking complexes, respectively, and may underlie the subunit-selective synaptic delivery of these AMPARs during conditioning. Further data are needed to determine if these auxiliary subunits are required for synaptic delivery or if other chaperone proteins are involved. Previously, we showed that GluA1 AMPAR subunits are withdrawn in later stages of conditioning and replaced by GluA4 subunits [3–5]. However, TARPγ8 remains at the membrane surface later in conditioning where it interacts with the newly delivered GluA4 subunits. It is unknown if TARPγ8 has a role in synaptic stabilization of GluA4-containing AMPARs during further conditioning. Our findings are consistent with previous studies showing that TARPγ8 traffics GluA1 during hippocampal LTP [21–24]. However, they are at odds with the report by Gu et al. [25] that suggest GSG1L acts as an inhibitory auxiliary subunit for AMPAR trafficking in LTP. One possibility in our system is that GSG1L induces GluA1 subunit withdrawal when it delivers GluA4 to synapses. Whether GSG1L negatively impacts AMPAR trafficking or is involved in forward trafficking as suggested here requires further study in a variety of learning systems and species to make general conclusions about GSG1L function.

Highlights.

Mechanisms for subunit-selective AMPAR trafficking in learning is poorly understood

Sequential delivery of GluA1 and GluA4 AMPARs underlies classical conditioning

TARPγ8 chaperones GluA1-containing AMPARs while GSG1L chaperones GluA4 subunits

Auxiliary proteins regulate sequential AMPAR synaptic delivery in conditioning

Acknowledgments

Funding

Supported by the National Institutes of Health grant NS 051187 to J.K. and a Medical Student Summer Research Program grant from the Sanford School of Medicine to L.B.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jackson AC, Nicoll RA. The expanding social network of ionotropic glutamate receptors: TARPs and other transmembrane auxiliary subunits. Neuron. 2011;70:178–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keifer J, Zheng Z. AMPA receptor trafficking and learning. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;32:269–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mokin M, Zheng Z, Keifer J. Conversion of silent synapses into the active pool by selective GluR1-3 and GluR4 AMPAR trafficking during in vitro classical conditioning. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:1278–1286. doi: 10.1152/jn.00212.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng Z, Sabirzhanov B, Keifer J. Two-stage AMPA receptor trafficking in classical conditioning and selective role for glutamate receptor subunit 4 (tGluA4) flop splice variant. J Neurophysiol. 2012;108:101–111. doi: 10.1152/jn.01097.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng Z, Keifer J. Sequential delivery of synaptic GluA1 and GluA4-containing AMPARs by SAP97 anchored protein complexes in classical conditioning. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:10540–10550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.535179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang MG, Nuriya M, Guo Y, Martindale KD, Lee DZ, Huganir RL. Proteomic analysis of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate receptor complexes. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:28632–28645. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.336644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwenk J, Harmel N, Brechet A, Zolles G, Berkefeld H, Muller CS, Bildl W, Baehrens D, Huber B, Kulik A, Klocker N, Schulte U, Fakler B. High-resolution proteomics unravel architecture and molecular diversity of native AMPA receptor complexes. Neuron. 2012;74:621–633. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwenk J, Baehrens D, Haupt A, Bildl W, Boudkkazi S, Roeper J, Fakler B, Schulte U. Regional diversity and developmental dynamics of the AMPA-receptor proteome in the mammalian brain. Neuron. 2014;84:41–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill MB, Kato AS, Roberts MF, Yu H, Wang H, Tomita S, Bredt DS. Cornichon-2 modulates AMPA receptor regulatory protein assembly to dictate gating and pharmacology. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6928–6938. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6271-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herring BE, Shi Y, Suh YH, Zheng CY, Blankenship SM, Roche KW, Nicoll RA. Cornichon proteins determine the subunit composition of synaptic AMPA receptors. Neuron. 2013;77:1083–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessels HW, Kopec CD, Klein ME, Malinow R. Roles of stargazin and phosphorylation in the control of AMPA receptor subcellular distribution. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:888–896. doi: 10.1038/nn.2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Opazo P, Labrecque S, Tigaret CM, Frouin A, Wiserman PW, De Koninck P, Choquet D. CaMKII triggers the diffusional trapping of surface AMPARs through phosphorylation of stargazin. Neuron. 2010;67:239–252. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Straub C, Tomita S. The regulation of glutamate receptor trafficking and function by TARPs and other transmembrane auxiliary subunits. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;22:488–495. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shanks NF, Savas JN, Maruo T, Cais O, Hirao A, Oe S, Ghosh A, Noda Y, Greger IH, Yates JR, Nakagawa T. Differences in AMPA and kainate receptor interactomes facilitate identification of AMPA receptor auxiliary subunit GSG1L. Cell Rep. 2012;1:590–598. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ziff EB. TARPs and the AMPA receptor trafficking paradox. Neuron. 2007;53:627–633. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keifer J. In vitro eye-blink reflex model: Role of excitatory amino acids and labeling of network activity with sulforhodamine. Exp Brain Res. 1993;97:239–253. doi: 10.1007/BF00228693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keifer J, Mokin M. Distribution of anterogradely labeled trigeminal and auditory nerve boutons on abducens motor neurons in turtles: Implications for in vitro classical conditioning. J Comp Neurol. 2004;471:144–152. doi: 10.1002/cne.20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruses JL. Identification of gene transcripts expressed by postsynaptic neurons during synapse formation encoding cell surface proteins with presumptive synaptogenic activity. Synapse. 2010;64:47–60. doi: 10.1002/syn.20702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keifer J, Zheng Z, Mokin M. Synaptic localization of GluR-containing AMPARs and Arc during acquisition, extinction, and reacquisition of in vitro classical conditioning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;90:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamasaki M, Fukaya M, Yamazaki M, Azechi H, Natsume R, Abe M, Sakimura K, Watanabe M. TARP γ-2 and γ-8 differentially control AMPAR density across Schaffer collateral/commissural synapses in the hippocampal CA1 area. J Neurosci. 2016;36:4296–4312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rouach N, Byrd K, Petralia RS, Elias GM, Adesnik H, Tomita S, Karimzadegan S, Kealey C, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. TARP γ-8 controls hippocampal AMPA receptor number, distribution and synaptic plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1525–1533. doi: 10.1038/nn1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sumioka A, Brown TE, Kato AS, Bredt DS, Kauer JA, Tomita S. PDZ binding of TARPγ-8 controls synaptic transmission but not synaptic plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1410–1412. doi: 10.1038/nn.2952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khodosevich K, Jacobi E, Farrow P, Schulmann A, Rusu A, Zhang L, Sprengel R, Monyer H, von Engelhardt J. Coexpressed auxiliary subunits exhibit distinct modulatory profiles on AMPA receptor function. Neuron. 2014;83:601–615. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi Y, Suh YH, Milstein AD, Isozaki K, Schmid SM, Roche KW, Nicoll RA. Functional comparison of the effects of TARPs and cornichons on AMPA receptor trafficking and gating. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:16315–16319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011706107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu X, Mao X, Lussier MP, Hutchison MA, Zhou L, Hamra K, Roche KW, Lu W. GSG1L suppresses AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission and uniquely modulates AMPA receptor kinetics in hippocampal neurons. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10873. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]