Abstract

We report two cases of bacteremia due to Clostridium difficile from two French hospitals. The first patient with previously diagnosed rectal carcinoma underwent courses of chemotherapy, and antimicrobial treatment, and survived the C. difficile bacteremia. The second patient with colon perforation and newly diagnosed lung cancer underwent antimicrobial treatment in an ICU but died shortly after the episode of C. difficile bacteremia. A review of the literature allowed the identification of 137 cases of bacteremia between July 1962 and November 2016. Advanced age, gastro-intestinal disruption, severe underlying diseases and antimicrobial exposure were the major risk factors for C. difficile bacteremia. Antimicrobial therapy was primarily based on metronidazole and/or vancomycin. The crude mortality rate was 35% (21/60).

Keywords: Clostridium difficile bacteremia, Toxin, Treatment, Outcome

Introduction

Clostridium difficile is an anaerobic gram-positive bacterium responsible for diarrhea. Spectrum of disease ranges from mild diarrhea to severe and complicated colitis, including pseudomembranous colitis, toxic megacolon and death [1], [2], [3]. C. difficile has been identified as the leading cause of healthcare-associated diarrhea among adults in industrialized countries. Increasing incidence of C. difficile infection (CDI) and large hospital outbreaks have been described worldwide [4], [5], [6], [7]. This trend is assumed to be due in part to the emergence and rapid spread of a highly virulent strain known as BI/NAP1/027 strain [8], [9], [10].

The main risk factors for CDI are antimicrobial exposure, prolonged hospitalization and age over 65 years. Severe underlying diseases are also commonly mentioned as predisposing situations to CDI developing. Any factors that disturb the host-microbiota homeostasis can promote C. difficile colonization and infection [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. The most commonly incriminated antimicrobials are cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones but all antimicrobial classes are associated with a risk of CDI and the antimicrobial stewardship programmes may play a key role in CDI prevention [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]. Metronidazole (MTZ), vancomycin (VA) and fidaxomicin (FDX) are the drugs of choice to treat CDI [24], [25].

Although C. difficile-associated diarrhea incidence is increasing worldwide, extracolonic infections with C. difficile, including bacteremia (CDB), remain uncommon. The most commonly reported extraintestinal infections include abdominopelvic abscesses, peritoneal and pleural infections, visceral abscess, as well as bacteremia [26], [27], [28]. Here we report two cases of CDB in two French hospitals and give a review of the literature to comprehensively present the clinical features of CDB.

Case report 1

A 54-year-old man was admitted with severe sepsis to the hepato-gastro-enterology unit at Tenon University Hospital, Paris, France, on 10 July 2012. He was febrile and blood cultures were taken during the fever. His blood pressure was 87/55 mm Hg and his pulse rate 83 beats per min; the white blood cell count was 15,200/mm3 with 12,050/mm3 neutrophils; the hemoglobin level was 10.3 g/L and that of C-reactive protein was 276 mg/L; urinalysis was unremarkable. His medical history included a rectal adenocarcinoma diagnosed in June 2010. At that time, he underwent surgical resection of the rectosigmoid colon and of hepatic metastases followed by multiple courses of chemotherapy. Postoperatively, a colostomy bag was required. He also underwent radiation therapy. During that period, he had recurrent episodes of urinary tract infections treated with multiple courses of antimicrobials including cefixime, nitrofurantoin and amoxicillin-clavulanate. Five months prior to his admission in July 2012, he developed an abdominal abscess with iliac vein thrombosis that was treated with ceftazidime and MTZ and then with piperacillin-tazobactam and amikacin. In the month preceding his admission, he had sepsis due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli that was treated with imipenem.

Blood cultures taken at admission grew an anaerobic gram-positive bacillus identified as C. difficile by mass spectrometry (Maldi-Tof, Bruker). A stool sample from the colostomy bag was examined for C. difficile a few days after the blood culture and was found to be positive. It also tested positive for glutamate dehydrogenase antigen (C DIFF Quick Chek® Alere™). A cytotoxicity assay using MRC-5 cells in order to detect free toxins was negative but culture of on selective TCCA (taurocholate, cycloserine, cefoxitin agar) was positive for toxigenic C. difficile. The bacteremia was treated with 500 mg intravenous MTZ every eight hours for three days. Repeated blood and stool cultures were negative and the treatment was switched to 500 mg oral MTZ every twelve hours for seventeen days. The patient recovered and was discharged to a palliative-care unit. C. difficile isolates from stool and blood cultures were sent to the National Reference Laboratory for C. difficile (Saint Antoine Hospital, Paris, France). Both isolates were toxigenic but did not produce the binary toxin. Their PCR ribotypes were identical, did not belong to the 25 most commonly identified PCR ribotypes (i.e., 070, 078/126, 002, 012, 029, 053, 075, 005, 018, 106, 131, 117, 003, 019, 046, 050, 014/020/077, 001, 015, 017, 023, 027, 056, 081 and 087) and were both susceptible to erythromycin, moxifloxacin, VA and MTZ.

Case report 2

A 62-year-old woman was admitted to Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital, Paris, France, on 26 June 2013 for fatigue, weight loss and arthralgia. On 27 June, computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen and pelvis revealed a malignant lung lesion associated with pleural effusion and putative secondary cancerous lesions of liver, vertebrae and pelvis. Two days later, the patient was transferred to an intensive care unit because of acute respiratory distress syndrome due to massive pleural effusion and acute pneumonia. Antimicrobial treatment associating cefotaxime (1 g three times a day) and spiramycin (3 MIU twice a day) was initiated. On 5 July, the patient developed a distended abdomen and guarding of the left upper and lower quadrants, associated with tachypnea and mottled skin. Abdominal CT showed a pneumoperitoneum. During tomography, a perforation (1 cm) of the sigmoid colon was found and a left hemicolectomy and terminal colostomy were performed. No evidence of peritoneal carcinomatosis was found. Following the operation, the patient became hypotensive and required fluid resuscitation and vasopressor therapy and she was transferred to an intensive care unit.

On admission to the ICU, she had sepsis-induced tissue hypoperfusion with hypothermia (33.6 °C), tachycardia (heart rate, 110 beats per min), leucocytosis (19,000/mm3), hyperlactatemia (5.6 mmol/L), mottled skin of the lower limbs and cyanosis of the soles of the feet. She was initially given intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam (4 g three times a day); 24 h later, intravenous ciprofloxacin was added (400 mg twice a day). Peritoneal fluid cultures were positive with polymorphic flora and ESBL-producing E. coli. Blood cultures performed between 5 and 7 July were positive with Bacteroides fragilis and C. difficile. The C. difficile toxins A and B were detected with the enzyme immunoassay ImmunoCard® Toxins A&B test (Meridian Bioscience, Cincinnati, OH, USA) directly from colonies. The C. difficile isolate was resistant to moxifloxacin and erythromycin and was sent to the National Reference Laboratory for further investigations. Antimicrobial therapy was changed to imipenem (500 mg four times a day) and VA with a loading dose (1 g) followed by continuous infusion (1 g per day). On 10 July, a ventilator-associated pneumonia due to Stenotrophomonas maltophilia was diagnosed and treated with intravenous trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (400 mg twice a day) and ciprofloxacin (400 mg twice a day). Following five days of treatment with intravenous VA, the treatment was switched to oral MTZ (500 mg three times a day) for 5 additional days. On 21 July, the patient developed rectal ischemia, her general condition worsened and she died on 25 July. Stools collected 48 h before her death were positive for the toxigenic C. difficile strain of PCR ribotype 078/126. The strain was resistant to moxifloxacin and erythromycin but susceptible to VA and MTZ.

Systematic review

Search strategy and selection criteria

The PubMed database was searched using the keywords “Clostridium difficile infection”; “extraintestinal C. difficile infection” (ECD); “Clostridium difficile bacteremia” (CDB); and C. difficile pathogenesis. Pertinent references included in some of the search results were also reviewed. Relevant articles and abstracts published in English; French and Japanese between 1962 (the first published CDB case) and November 2016 were selected. Among these articles; about 28 with descriptive cases of CDB and 10 other reports including other CDB cases were retrieved. The published reports were heterogeneous. The majority were published as case reports and the others were epidemiological or retrospective studies. The other main publications were related to CDB subject or to the particular features of Clostridium difficile pathogenesis. A single author (MD) reviewed the relevant articles and abstracts. A description of the patients’ clinical features; treatment and/or outcome was often lacking. The reported cases with missing clinical data about the analyzed parameter were not included in the statistical analysis.

Descriptive statistics were used to determine the mean age and to summarize the distribution of CDB among the cohort of report cases in literature. Statistical analysis was performed using StatView software, version 5.0.0.0 (SAS Institute Inc). Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or two-tailed Fisher’s exact test where applicable. For all statistical comparisons, results were considered significant when the p value was <0.05.

Frequency of CDB

To date, 137 CDB cases have been reported in the literature comprising 60 cases (including the 2 cases presented in this report) with detailed clinical patient characteristics. Most commonly reported information included age, sex, underlying diseases, toxinogenicity of the strain, antimicrobial therapy and clinical outcome. Apart from the 60 cases, 77 have been identified in epidemiological reports aiming at determining the incidence of CDB (Table 1, Table 2). The first case of CDB was described in 1962 in a 5-month-old male infant with a 3-week history of coryza, cough, and anorexia [29]. In 1975, Gorbach et al. reported one C. difficile isolate found among 2168 positive blood cultures (0.05%) in one general hospital over a 14-month period [30]. During a 10-year period (1985–1995), Wolf et al. identified three patients with CDB among 14 patients with ECD in a tertiary-care hospital [31]. Rechner et al. identified one isolate of C. difficile when retrospectively reviewing the blood cultures positive for Clostridium species in two teaching hospitals of ca. 300 and 200 beds, respectively, representing a total of 164,304 hospitalizations [32]. Garcia-Lechuz et al. reported two episodes of CDB during a 10-year period (1990–2000) in a large tertiary-care teaching hospital serving a population of approximately 650,000 with an average of 50,000 admissions per year [33]. This corresponds to an incidence of 0.4 cases per 100,000 admissions. Among 25 extraintestinal C. difficile infections recorded between 1988 and 2003, Zheng et al. found out two isolates from blood cultures but did not report clinical features [34]. Another epidemiological study covering a large Canadian health region (population 1.2 million) conducted over a six-year period (2000–2006) reported a CDB incidence of 0.08 per 100,000 residents per year [35]. This study reported a CDB prevalence of 5% among clostridial bacteremias, which is in line with that of 7% (3/42) reported by McGill et al. in England. In this latter study, the rate of CDB between 2004 and 2008 was estimated to be about 0.01% to 0.02% among a total of 320,371 bacteremias [36]. Thus, the National Health Protection Agency in the UK registered 62 CDB cases during 2003–2008 (range: 9–17 per annum) with a tendency for decreasing incidence (no CDB case was reported in the period 2008–2012 and 2010–2014) in England, Wales and Northern Ireland [37], [38], [39]. A recent retrospective medical record review conducted from January 1, 2004 through December 31, 2013 as a single-center experience exposed 40 ECD with 11C. difficile bloodstream infections identified among 6525 CDI cases [28]. Other cases have been reported as individual cases and are summarized in the present review (Table 2).

Table 1.

Epidemiology of C. difficile bacteremias reported in the literature.

| Period | Country | Number of CDB casesa | Incidence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1962–1969 | USA | 3 Isolates/86 nonhistotoxic clostridial bacteremias (laboratory isolates)* | 0.4 | [42], [52] |

| 15 months | USA | 1 Blood culture isolate (Anaerobe study)* | 0.8 | [53] |

| 14 months | USA | 1 CDB/2168 bacteremias* | 0.9 | [30] |

| 1985–1995 | USA | 3 CDB/14 ECD2 | 0.3 | [31] |

| 1990–1997 | USA | 1/164 304 hospitalizations* | 0.13 | [32] |

| 1990–2000 | Spain | 2 CDB/21 ECD (50 000 admissions/year)b | 0.2 | [33] |

| 1988–2003 | USA | 2 Blood culture isolates/25 ECD* | 0.2 | [34] |

| 2000–2006 | Canada | 7 CDB/1.2 million residents* | 1 | [35] |

| 2004–2008 | UK | 62 CDB/320 371 bacteremias* | 9 to 17 | [36], [37] |

| 2008–2012 | UK | 0 | 0 | [38] |

| 2010–2014 | UK | 0 | 0 | [39] |

| 1989–2009 | Taiwan | 12 CDB/2 medical centersb,c | 0.6 | [43] |

| 2002–2012 | Finland | 2 CDB/31 ECDb | 0.2 | [54] |

| 2004–2013 | USA | 11 CDB/40 ECD/6525 CDIb | 1.1 | [28] |

| 1962–2016 | All countries | Total: 137 (the 58 published casesb, the two present casesb and 77* cases in other reports) | Present review |

CDB cases of each study or literature review when clearly mentioned in articles or reports.

Cases with clinical data reported in Table 2.

1100-bed and 2800-bed tertiary-care hospitals in Taiwan.

Cases not available with clinical data but exposed in other reports in the reviewed literature.

Table 2.

Summary of the 58 well-documented C. difficile bacteremia cases (1962–2016) reviewed in this study and the present two cases.

| Age/sex. | Underlying conditions | Clinical presentation | Antimicrobial exposure1 | Strain toxicity from blood/stool | Other organisms in blood culture | Clinical management | Outcome | Year Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 months/M | None | Cough, coryza, anorexia | NR | NR/NR | None | NR | NR | 1962 [29] |

| 19 months/M | Pseudomembranous NEC, systemic carnitine deficiency (recurrent hypoglycemia and cirrhosis) | Frequent sepsis, diarrhea, vomiting, peritonitis | ampicillin + gentamicin | Yes/NR | None | NR | Died | 1982 [40] |

| 68/M | Cirrhosis, chronic pancreatitis | Jaundice, ascites, encephalopathy, splenic abscess | None | NR/NR2 | None | Penicillin G, DAT | Died | 1983 [55] |

| Neonate/M | Prematurity, neonatal NEC | Fever, respiratory distress, abdominal distension, necrotic bowel, peritonitis | Ampicillin + kanamycin | Yes3/NR | S. epidermidis3 (contaminant) | Ampicillin + kanamycin Surgery, DAT | Died | 1984 [56] |

| 65/M | Arteritis of legs and gangrene | Diarrhea and colitis 6th day, septicemia 10th day postoperative | Cefuroxime, vancomycin | Yes/No | B. fragilis | Cefuroxime,MTZ | Recovered | 1984 [57] |

| 35/F | AML, neutropenia | Fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea | Cefotaxime + gentamicin | Yes/Yes | Bacteroides sp., Gr. D streptococci | iv MTZ + oral VA | Died | 1985 [58] |

| 69/F | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chemotherapy corticosteroids | Abdominal distension, peritonitis, toxic megacolon, bilateral psoas abscesses | Yes | Yes/Yes | Bacteroides sp., E.coli | Cloxacillin, Co, iv MTZ, ampicillin, gentamicin | Died | 1985 [58] |

| 62/M | Hypertension, coronary surgery, appendectomy, cholecystectomy, aortofemoral bypass, C. difficile septicemia 5 months before | Fever, nausea, vomiting, left pleural effusion, splenic abscess | Piperacillin, netilmicin | NR/NR | None | Splenectomy MTZ, cefoxitin | Recovered | 1987 [59] |

| 39/M | Oropharynx cancer | Left mandible radionecrosis, hypotension, fever, acute diverticulitis | NR | Yes/Yes | E. coli, E. faecalis, B. vulgatus | iv MTZ, iv and oral VA, pefloxacin | Recovered | 1989 [47] |

| 85/F | Chronic pulmonary disease, heart failure, dementia, sinus bradycardia, ischemic attack, pneumonia | Recurrent diarrhea, fever hypotension | VA | NR/Yes | E. faecalis | iv VA, gentamicin | Recovered | 1995 [26] |

| 18/M | None | Treated for exudative sore throat, fever, chills, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea | Erythromycin, lincomycin | NR/Yes | None | Oral VA | Recovered | 1996 [60] |

| 78/M | None | Trauma; pneumonia, fever, watery diarrhea | Ofloxacin, clindamycin, cefuroxime, amikacin | NR/No | None | Oral and iv VA | Recovered (died from nosocomial pneumonia) | 1996 [60] |

| 3/M | Thalassemia minor, 5 episodes of tonsillitis | Fever, odynophagia, acute pericarditis, pericardial effusion, mild GI signs | Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cefixime, cefotaxime | Yes/NT | None | iv VA | Discharged | 1998 [61] |

| 17/M | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | Ileus with small‐bowel obstruction | Yes | NT/NT | Candida parapsilosis | NR | Recovered | 1998 [31] |

| 33/F | Metastatic cervical cancer | Pelvic abscesses, recto-vaginal fistula after radiotherapy | Yes | NT/NT | C. cadaveris, B. melaninogenicus, Fusobacterium species | NR | Died | 1998 [31] |

| 77/M | Severe emphysema, corticosteroid therapy | Perforated sigmoid diverticulum | Yes | NT/NT | Eubacterium lentum | NR | Died | 1998 [31] |

| 66/M | Infiltrating bladder cancer | Intestinal invasion of the advanced bladder cancer, pyelonephritis | NR | NR/NT | E. faecium, B.fragilis | Imipenem | Died | 2001 [33] |

| 65/M | Obesity | Ischemic colitis after cardiac surgery, bacteremic peritonitis | NR | NR/NT | E. faecium, B. ovatus | Ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin | Died | 2001 [33] |

| 66/M | AML, immunodepression, chemotherapy | Fever, pancytopenia, anal margin abscess and diarrhea | C3G+ FQ | NR/NR | None | Ofloxacin, MTZ, abscess drainage | Recovered | 2001 [62] |

| 69/F | 3rd degree burn injuries | Skin operation, fever, abdominal pain and severe diarrhea | Cefazolin, flomoxef | Yes/Yes | E. faecalis, E.casseliflavus | oral and iv VA | Recovered | 2004 [63] |

| 50/M | Crohn's disease with chemotherapy | Nausea, abdominal abscess, small-bowel obstruction, bowel surgery, jejunum adenocarcinoma | Ampicillin/sulbactam + gentamicin | NR/No | None | Pip-Taz | Recovered | 2009 [45] |

| 40/F | AML, Dermatomyositis, corticosteroid treatment | Fatigue, weight loss, fever, tachycardia | Yes, unknown antimicrobials | NR/NT | None | Cefepime, MTZ, iv VA | Died | 2009 [27] |

| 40/M | Alcoholism, liver failure, bone marrow suppression, pancreatitis, and recurrent pneumonia. | Vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever | Cephalexin | No4/NR | Staphylococcus epidermidis (contaminant) | Ceftriaxone | Discharged5 | 2009 [46] |

| 1989–2009 | Taiwan, 12 patients [43]: | |||||||

| 69/F | Liver cirrhosis | NR (Dead on arrival) | NR | Yes/NR | None | None | Died | 2010 |

| 38/M | Wilson’s disease | Abdominal pain | NR | No/NR | None | Cefmetazole | Died | 2010 |

| 65/F | Perforated peptic ulcer | Fever, abdominal pain | NR | NR/NR | None | MTZ | Died | 2010 |

| 58/M | Liver cirrhosis | Fever, abdominal pain | NR | No/NR | None | MTZ | Recovered | 2010 |

| 12/M | Biliary atresia, liver transplantation | Fever, dyspnea | NR | No/NR | None | Pip-Taz, VA | Recovered | 2010 |

| 41/F | Pulmonary fibrosis | Fever, dyspnea | NR | No/NR | None | Ceftazidime, gentamicin, VA | Recovered | 2010 |

| 45/M | Liver cirrhosis | Abdominal pain | NR | Yes/NR | CNS spp. | Ceftriaxone | Died | 2010 |

| 83/M | None | GI bleeding, hypovolemic shock, fever, bloody stool |

NR | No/NR | E. coli | Imipenem | Died | 2010 |

| 87/F | Congestive heart failure, end-stage renal disease, pseudomembranous colitis | Bloody stool | NR | Yes/NR | P. aeruginosa, E.faecium, E. coli, ESBL-K. oxytoca | VA, meropenem | Recovered | 2010 |

| 80/F | Liver cirrhosis, pseudomembranous colitis | Bloody stool | NR | Yes/NR | CNS spp. | MTZ | Recovered | 2010 |

| 66/F | Femoral neck fracture (hip replacement with prosthetic infections), chronic kidney disease | Fever, lower GI bleeding, abdominal pain | NR | No/NR | E. cloacae | Debridement cefepime, MTZ | Recovered | 2010 |

| 75/F | Lymphoma, biliary tract infection | Fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain | NR | NR/NR | K. pneumoniae, C.perfringens | Cefepime, MTZ | Recovered | 2010 |

| 39/M | Alcohol dependency | Jaundice, vomiting, fecal incontinence | None | NR/NR | None | Cefuroxime, MTZ | Discharged | 2011 [36] |

| 20/M | Juvenile polyposis syndrome, elective subtotal colectomy | UTI, small-bowel resection and end-ileostomy, CD ileitis | Cephradine, Pip-Taz | NR/Yes | None | Oral VA, meropenem, iv MTZ | Discharged | 2011 [36] |

| 67/M | Ulcerative colitis | GI bleed | None | NR/Yes | None | None | Discharged | 2011 [36] |

| 39/F | Chronic hepatitis, chronic alcoholic liver disease | Menorrhagia, spontaneous bruising, jaundice. 3rd week: fever, rectal bleed, varices, gastritis, breast abscess | Cefotaxime | NR/NR | None | MTZ + amoxicillin/clavulanic | Recovered | 2011 [48] |

| 83/M | CAD, chronic hemodialysis, diverticulitis and peptic ulcer disease | Fever, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, bleeding post gastrostomy tube placement | Amikacin, VA, Pip-Taz | Yes/No | None | MTZ | Recovered | 2011 [49] |

| 39/M | Gastric adenocarcinoma, chemotherapy and chemoradiation | Abdominal pain, vomiting and obstipation | None | Yes/NT | Candida glabrata | NR | Recovered then discharged | 2011 [49] |

| 60/M | Metastatic prostate cancer | Fever, abdominal pain, hematochezia, hydronephrosis, rectal stricture, loop ileostomy | VA + meropenem, ticarcillin, piperacillin + MTZ | NR/No | None | NR | Discharged | 2013 [64] |

| 72/F | Colon cancer with peritoneal carcinosis | Tumor resection, colon fistula to skin and bladder, diarrhea | NR | NR/NR | B. fragilis | NR | Died | 2013 [54] |

| 69/M | Paraparesis, recurrent UTI | Ischemic colitis, diarrhea, operation for abdominal aneurysm | Yes for UTI | NR/NR | None | Surgery (Aneurysm prosthesis) | Recovered | 2013 [54] |

| 57/M | Mantle cell lymphoma | Abdominal pain, intra-abdominal tumor and cecum perforation | None | NR/NR | None | iv VA + MTZ | Recovered then discharged | 2013 [65] |

| 2004–2013 | USA, 11 patients: | 10/11 had diarrhea | All of them | 11NT/5Yes (10 stools tested) | 3 Monomicrobial | 1 ATB/10 surgery + ATB | 3 Died/8 Recovered | 2014 [28] |

| 88/F | Peptic ulcer disease after partial gastrectomy | C. difficile colitis, lower gastro-intestinal bleed | Yes | B. fragilis, E. coli, P. aeruginosa | oral MTZ, iv cefepime, iv ciprofloxacin | Recovered | 2014 | |

| 75/F | Squamous cell carcinoma of mouth after resection | Cecal impaction and rupture after laparotomy | Yes | Candida tropicalis | Abdominal washouts, meropenem | Died 17 days later | 2014 | |

| 46/F | Hepatic adenoma after resection | Alcoholic hepatitis and ascites | Yes | Enterococcus species, Candida species, Klebsiella species | Paracentesis, MTZ, cefepime | Recovered | 2014 | |

| 41/F | Alcohol abuse after inguinal hemia repair | Recurrent groin cellulitis | Yes | Clostridium orbiscindens | Debridement of groin infection, meropenem, linezolid | Recovered | 2014 | |

| 47/F | Crohn disease, multiple suicide attempts after self-stab to abdomen leading to liver laceration | Self-inflicted abdominal wounds, suspicion for factitious contamination | Yes | Enterococcus species, Clostridium ramosum, Bacteroides species | Wound debridement Pip-Taz | Recovered | 2014 | |

| 79/F | Colorectal cancer after resection, C. difficile colitis | Ovarian cyst after oophorectomy, postoperative confusion, ascites | Yes | None | Paracentesis, VA, Pip-Taz | Died 7 days later | 2014 | |

| 80/F | Diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, COPD, stroke | Diverticulitis after laparotomy | Yes | E. coli | Abdominal washout, cefepime | Died 6 days later | 2014 | |

| 51/F | Ileal neuroendocrine tumor, Crohn disease after ileal and sigmoid resection, C. difficile colitis | Anastomotic breakdown and postoperative fever | Yes | None | Anastomotic takedown, colostomy, washout, levofloxacin, MTZ | Recovered | 2014 | |

| 35/M | Congenital pancreatic duct abnormality after pancreatectomy, splenectomy, C. difficile colitis | Recurrent polymicrobial bacteremia and skin abscesses | Yes | Blautia coccoides, K. pneumoniae, E. coli | Skin debridement meropenem, linezolid | Recovered | 2014 | |

| 56/F | COPD, concurrent C. difficile colitis, small intestinal bowel obstruction after adhesiolysis | Abdominal compartment syndrome, surgical wound infection | Yes | None | Wound debride, MTZ, VA | Recovered | 2014 | |

| 27/F | Crohn disease, recurrent C. difficile colitis | Previous right hemicolectomy and ileostomy | Yes | Citrobacter species, Streptococcus anginosus | Anastomotic takedown, washout, MTZ, VA, ertapenem | Recovered | 2014 | |

| 40/M | Alcohol liver disease | Abdominal pain, vomiting, cirrhosis, gastrohepatic varices, colitis | None | NR/Yes | None | iv VA + Pip-Taz | Died | 2015 [51] |

| Neonate/NR | NEC | Large bowel wall pneumatosis with out perforation | None | NT/NT | None | VA+ MTZ +gentamicin, Pip-Taz + MTZ | Recovered | 2016 [66] |

| 54/M | Rectal adeno-carcinoma, colostomy, chemotherapy | Severe sepsis | Imipenem | Yes/Yes | None | iv and oral MTZ | Recovered | Present Case 1 |

| 62/F | Lung cancer with cancerous lesions of liver, vertebrae and pelvis | Colon perforation, hemicolectomy and end colostomy | Cefotaxime + spiramycin, Pip-Taz, ciprofloxacin | Yes/Yes | B. fragilis | iv VA, oral MTZ, other antimicrobials | Died | Present Case 2 |

NR (Not reported), NT (Not tested).

CNS: Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp., DAT: diagnosis at autopsy, UTI: urinary tract infection, iv: intravenous, GI: gastrointestinal, NEC: Necrotizing enterocolitis, AML: Acute myeloid leukemia, CAD: Coronary artery disease, COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, VA: Vancomycin, MTZ: Metronidazole, Co: Cotrimoxazole, Pip-Taz: Piperacillin − Tazobactam, C3G: Third cephalosporin generation, FQ: Fluoroquinolone, ATB: antibacterial.

Antimicrobial exposure in the 3 months preceding CDB.

Abscess toxin+.

Heart Blood (Autopsy).

A-B- Binary toxin+.

Discharged: Home or hospice care.

Patient characteristics

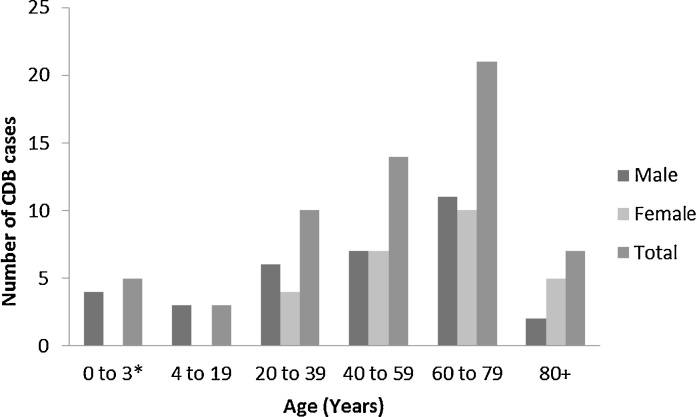

Analysis of the 58 cases described in the literature and of the two cases presented here showed that CDB affected male as well as female (33/59, [56%] and 26/59, [44%] respectively). Excluding two neonates, two infants (5 months and 19 months), and one 3-year-old child, the mean age (±standard deviation) was 56.1 ± 19.7 years (range, 12–88 years). Concerning infants or neonates, they may have inflammatory intestinal conditions favoring CDI [40], [41]. About 47% (28/60) of the described patients are over sixty and among them 35% (21/60) are between 60 and 79 years old. The data suggest that advanced age may be a risk factor for CDB (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the 60 recorded CDB cases according to age and sex. (*: 1 neonate with not reported sex by Bergamo et al.).

Analysis of the data from the combined 60 cases showed that 93% (56/60) of patients had severe underlying diseases (e.g. colon carcinoma, liver cirrhosis, leukemia, cardiovascular disease), 85% (41/48) had abdominal setting (e.g. abdominal pain, diarrhea, bowel surgery, colitis), and 84% (36/43) had previous antibacterial treatment. Interestingly, only three patients (6%) presented diarrhea as the single abdominal symptom, 17% (8/48) developed this symptom with other abdominal disturbances, 62% (30/48) had abdominal signs without diarrhea and the others (7/48, [15%]) presented other clinical features (Table 3). The cases described in the recent experience of Gupta et al., not included in analysing proportions of CDB associated symptoms, were globally reported to have diarrhea for 10 patients of 11 and 3 of 11 with inflammatory bowel disease without specifying if the concerned patients presented other abdominal symptoms. Concerning diarrhea, there was a significant difference between Gupta et al. patients and the other literature cases (10/11, [91%] vs. 11/48, [23%]; p < 0.0001). However, there was no difference between Lee et al. series and the other literature cases with or without Gupta et al. cases (4/12 [33%] vs. 7/36 [19%]; p = 0.43, and 4/12 [33%] vs. 17/47 [36%] respectively; p = 1.0). These data show that CDB is not systematically associated with documented diarrhea while the presence of other abdominal symptoms was associated with bacteremia. Usually CDB was often preceded by gastrointestinal disorders (e.g. abdominal pain, enterocolitis or surgical and spontaneous disruption of the colon), or by previous exposure to cytotoxic drugs or antimicrobials.

Table 3.

Overview of the C. difficile toxinogenic status both in blood and in stools and its relationship with the clinical setting.

| Toxin status in Blood/Stools | Diarrhea | Diarrhea and abdominal signs | Abdominal features | Other symptoms | NRa | Gupta et al. cases | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes/Yes | – | 2 | 3 | 1 | – | – | 6 |

| Yes/No | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | 2 |

| Yes/NR | – | 1 | 6 | – | 1 | – | 8 |

| No/NR | – | 1 | 4 | 2 | – | – | 7 |

| NT/Yes | 1 | 1 | 3 | – | – | 5 | 10 |

| NT/No | 1 | – | 2 | – | – | 5 | 8 |

| NR, NT/NR, NT | 1 | 2 | 11 | 4 | – | 1 | 19 |

| Total | 3 | 8 | 30 | 7 | 1 | 11 | 60 |

NR (Not reported), NT (Not tested).

One of Lee et al. cases: dead on arrival.

It may be assumed that the bowel is the primary site of clostridial colonization which may predispose C. difficile to spread by translocation or intestinal perforation [17], [42]. Indeed, monomicrobial CDB was present as frequently as CDB associated with additional pathogens to C. difficile (30/60, [50%]), which is similar to the 50% (6/12) of Lee et al. series, even if it has been reported that CDB were rather polymicrobial infections probably because of the small number of cases recorded at that time [27], [43], [44], [45]. In CDB, isolates other than C. difficile are often also from the gut flora. This indicates the ability of intestinal bacteria to translocate in patients with bowel damage. However, it is still unclear whether intestinal infection with C. difficile is the primary infection that promotes bacterial translocation or whether an underlying disease (e.g. colonic ischemia, intestinal tract disorders or disruption of mucosal barriers) is the initial step that facilitates bacteria dissemination. The use of proton pump inhibitor (PPIs) was not mentioned in the majority of published reports except in one recent study where 9 of 11 patients with CDB (82%) had received PPI for various indications [28].

Strain toxin production

The potential of C. difficile isolates from blood to produce toxins A and B in vitro has been rarely investigated. Among the 23 CDB cases where the toxigenic status of blood strains was mentioned, 16 stains were toxigenic (70%) and 7 (30%) were non-toxigenic (Table 3). The direct detection of toxins in blood has never been reported. One bacteremia due to binary-toxin producing strain was reported by Elliott et al. [46].

In 26 of the 60 cases, the stools of patients with CDB were tested for C. difficile. In ten cases (38%) the isolate was non-toxigenic while in 16 cases (62%) it was toxigenic. Among the 16 patients with CDB due to a toxigenic strain isolated in blood, six had a toxigenic and two a non-toxigenic strain in their stools, the latter suggesting the presence of two different strains in the gut. It is still unknown whether toxigenic strains may translocate more easily into the blood than non-toxigenic strains. In addition, the rare patients who had only diarrhea, toxin is positive in stools as well as negative but the presence of abdominal symptoms with or without diarrhea appear more common with the presence of toxigenic strain. This data need to be further investigated.

About a third of the reviewed cases have non documented toxin status for both blood and stool (19/60, 32%). In blood, most toxigenic status of isolated strains (37/60, 62%) was lacking, possibly due to the non-systematic toxin search in extra-intestinal samples. Indeed, stools were not tested in more than half of cases (34/60, 57%), which is perhaps likely due to the absence of diarrhea.

Typing of strains isolated from blood culture has been rarely reported, probably because molecular typing was uncommon when CDB cases were described in the early 1990s. Gérard et al. characterized a serogroup C strain and McGill et al. reported two ribotype 106 strains and one ribotype 001 [36], [47]. Another case report detected a ribotype 106 from bacteremia and breast abscess [48]. One of two bacteremia cases recently reported by Hemminger et al. was due to the epidemic and hypervirulent NAP1 strain (027/BI, toxinotype III, binary toxin-positive), and the other was due to NAP-4 [49]. In the present series, Case 2 was due to a strain of ribotype 078/126 which is one of the ribotypes most frequently found in France [50]. So far, there is no evidence indicating that one specific ribotype may be more often responsible for CDB than another.

Mortality

CDB-associated mortality rates vary among studies. The present comprehensive review indicates a crude mortality rate of 35% (n = 21/60) which is in line with the early reviews of Jacobs et al. and Libby et al. (20% [2/10], p = 0.48; 53% [8/15], p = 0.19 respectively), with that reported by Lee et al. (41.7%, 5/12, p = 0.75) and also similar to the recent study of Gupta et al. (27% [3/11], p = 0.74) [27], [28], [43], [44]. The latest review of Kazanji et al. concluded to the same rate (39%, p = 0.68) [51]. However, the mortality attributable to CDB remains difficult to assess because many patients with CDB have severe co-morbidities and underlying conditions.

Treatment

Antimicrobial therapy for CDB was highly variable and most of the time adapted to cover polymicrobial bacteremia. As CDB is a rare infection, there are no studies or specific guidelines for the appropriate therapy, but metronidazole (MTZ) and vancomycin (VA) are the commonly treatment options used to deal with CDB [27], [28], [43]. In CDB Case 1 we reported here, the patient was treated first with intravenous (IV) and then oral MTZ, and the septicemia rapidly resolved. Most commonly used treatments include VA or MTZ alone or in combination and in this review about 67% (35/52) had one of these two antimicrobials or both and eight patients had their therapeutic coverage not specified (Table 4). Treatment was usually started intravenously and continued orally. Sixteen patients were treated with MTZ (one IV and orally, one orally, not specified in the remaining cases), ten with VA (three IV, two orally and IV, one orally, four not specified) and nine with VA or MTZ sequentially or simultaneously (usually IV initially, then orally). These specific treatments against C. difficile were used alone or associated with other antimicrobials and surgery. MTZ and VA are usually associated with other antimicrobials with extended spectrum and against anaerobes according to the clinical setting. Of note, patients with MTZ, VA or both had a reduced rate of mortality than those with other antimicrobials (22% [6/27], 75% [6/8]; p = 0.011). The crude mortality rate in patients managed with associated medical and surgical therapy was 20% (7/35) compared to 59% (10/15) in those who did not receive antimicrobial therapy including MTZ or VA or both (p = 0.005). Therefore, management with medical therapy involving drugs against C. difficile appears to prevent death during CDB episode. Hence, the choice of treatment, the way the drugs are administered and the treatment duration may change but early patient management and antibacterial coverage may critically influence outcome.

Table 4.

Clinical management of the 60 patients with CDB and the crude rate of mortality.

| Medical Management | MTZ or/and VA |

Other ATB | Other ATB and Surgery | Surgery alone | No therapy | NRa | Totala | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | CD therapy | CD therapy and surgery | |||||||

| No. of patients (No. of death) | MTZ | 5 (1) | 0 | 8 (6) | 5 (2) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 8 (4) | 60 (21)* |

| MTZ + ATB | 6 (1) | 5 (0) | |||||||

| VA | 4 (0) | 0 | |||||||

| VA + ATB | 5 (1) | 1 (1) | |||||||

| MTZ + VA | 2 (1) | 1 (0) | |||||||

| MTZ + VA + ATB | 5 (2) | 1 (0) | |||||||

| Rate of mortality, p value | 22% (6/27) | 13% (1/8) | 75% | 40% | 50% | 50% | 50% | 35%* | |

| 20% (7/35) vs. 62% (8/13), p = 0.012 | |||||||||

| 20% (7/35) vs. 60% (9/15), p = 0.009 | |||||||||

| 20% (7/35) vs. 59% (10/17), p = 0.005 | |||||||||

MTZ: Metronidazole, VA: Vancomycin, ATB: other antibacterial, CD therapy: C. difficile therapy (MTZ or/and VA), NR (Not reported).

The case reported by Smith et al. with NR therapy and NR outcome status, accounted in mortality rate, did not change the conclusion. Surgery included all operations and other procedures used to resolve CDB and the implicated source of bacteria dissemination (e.g. abdominal washout, debridement).

In conclusion, CDB remains uncommon. It occurs mostly in patients with risk factors such as chronic underlying diseases, advanced age, coexisting gastrointestinal pathologic conditions and antimicrobial exposure. Outcome depends on various factors including early diagnosis, severity of the underlying conditions and antimicrobial therapy. MTZ and VA are the two drugs currently used to cover CDB. However, it is difficult to assess the most effective treatment since data on outcome are not systematically reported.

Contributors

M. DOUFAIR, reviewed the literature, wrote the text and set figure and tables. F. BARBUT and C. ECKERT provided help and advices for writing. C. AMANI-MOIBENI and J-D. GRANGE wrote the case 1 whereas L. DRIEUX and L. BODIN wrote the second case. M. DENIS gave advices concerning clinical management.

Declaration of interests

We declare that we have no competing interests

Acknowledgment

We thank Ekkehard COLLATZ for his help to manuscript correction.

References

- 1.Kuipers E.J., Surawicz C.M. Clostridium difficile infection. Lancet. 2008;371:1486–1488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60635-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goudarzi M., Seyedjavadi S.S., Goudarzi H., Mehdizadeh Aghdam E., Nazeri S. Clostridium difficile infection: epidemiology, pathogenesis, risk factors, and therapeutic options. Scientifica. 2014;2014:916826. doi: 10.1155/2014/916826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eckert C., Lalande V., Barbut F. Clostridium difficile colitis. Rev Prat. 2015;65:21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckert C., Barbut F. Clostridium-difficile-associated infections. Méd Sci MS. 2010;26:153–158. doi: 10.1051/medsci/2010262153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magill S.S., Edwards J.R., Bamberg W. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1198–1208. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamagishi Y., Mikamo H. [Recent epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infection in Japan] Jpn J Antibiot. 2015;68:345–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zacharioudakis I.M., Zervou F.N., Pliakos E.E., Ziakas P.D., Mylonakis E. Colonization with toxinogenic C. difficile upon hospital admission, and risk of infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:381–390. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.22. quiz 391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartlett J.G. Narrative review: the new epidemic of Clostridium difficile-associated enteric disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:758–764. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbut F., Monnier A.L., Eckert C. Infections à Clostridium difficile: aspects cliniques épidémiologiques et thérapeutiques. Réanimation. 2011;21:373–383. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lessa F.C., Gould C.V., McDonald L.C. Current status of Clostridium difficile infection epidemiology. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(Suppl. 2):S65–70. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho S.M., Lee J.J., Yoon H.J. Clinical risk factors for Clostridium difficile-associated diseases. Braz J Infect Dis. 2012;16:256–261. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702012000300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olson D.C., Scobey M.W. The challenge of clostridium difficile infection. N C Med J. 2016;77:206–210. doi: 10.18043/ncm.77.3.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vincent C., Miller M.A., Edens T.J., Mehrotra S., Dewar K., Manges A.R. Bloom and bust: intestinal microbiota dynamics in response to hospital exposures and Clostridium difficile colonization or infection. Microbiome. 2016;4:12. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0156-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milani C., Ticinesi A., Gerritsen J. Gut microbiota composition and Clostridium difficile infection in hospitalized elderly individuals: a metagenomic study. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25945. doi: 10.1038/srep25945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khanna S., Pardi D.S. Clinical implications of antibiotic impact on gastrointestinal microbiota and Clostridium difficile infection. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016:1–8. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2016.1158097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shin J.H., High K.P., Warren C.A. Older is not wiser, immunologically speaking: effect of aging on host response to clostridium difficile infections. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71(7):916–922. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv229. published online Jan 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanchi J., Goret J., Mégraud F. Clostridium difficile infection: a model for disruption of the gut microbiota equilibrium. Dig Dis Basel Switz. 2016;34:217–220. doi: 10.1159/000443355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pépin J., Saheb N., Coulombe M.-A. Emergence of fluoroquinolones as the predominant risk factor for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a cohort study during an epidemic in Quebec. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1254–1260. doi: 10.1086/496986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vincent C., Stephens D.A., Loo V.G. Reductions in intestinal Clostridiales precede the development of nosocomial Clostridium difficile infection. Microbiome. 2013;1:18. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tartof S.Y., Rieg G.K., Wei R., Tseng H.F., Jacobsen S.J., Yu K.C. A comprehensive assessment across the healthcare continuum: risk of hospital-associated clostridium difficile infection due to outpatient and inpatient antibiotic exposure. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36:1409–1416. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feazel L.M., Malhotra A., Perencevich E.N., Kaboli P., Diekema D.J., Schweizer M.L. Effect of antibiotic stewardship programmes on Clostridium difficile incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:1748–1754. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarma J.B., Marshall B., Cleeve V., Tate D., Oswald T., Woolfrey S. Effects of fluoroquinolone restriction (from 2007 to 2012) on Clostridium difficile infections: interrupted time-series analysis. J Hosp Infect. 2015;91:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilcox M.H., Chalmers J.D., Nord C.E., Freeman J., Bouza E. Role of cephalosporins in the era of Clostridium difficile infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;72(1):1–18. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw385. published online Sept 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Debast S.B., Bauer M.P., Kuijper E.J. Committee OB of T. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: update of the treatment guidance document for Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:1–26. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ofosu A. Clostridium difficile infection: a review of current and emerging therapies. Ann Gastroenterol. 2016;29:147–154. doi: 10.20524/aog.2016.0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feldman R.J., Kallich M., Weinstein M.P. Bacteremia due to Clostridium difficile: case report and review of extraintestinal C difficile infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1560–1562. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.6.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Libby D.B., Bearman G. Bacteremia due to Clostridium difficile—review of the literature. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:e305–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta A., Patel R., Baddour L.M., Pardi D.S., Khanna S. Extraintestinal Clostridium difficile infections: a single-center experience. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:1525–1536. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith L.D., King E.O. Occurrence of Clostridium difficile in infections of man. J Bacteriol. 1962;84:65–67. doi: 10.1128/jb.84.1.65-67.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorbach S.L., Thadepalli H. Isolation of Clostridium in human infections: evaluation of 114 cases. J Infect Dis. 1975;131(Suppl):S81–85. doi: 10.1093/infdis/131.supplement.s81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolf L.E., Gorbach S.L., Granowitz E.V. Extraintestinal Clostridium difficile: 10 years’ experience at a tertiary-care hospital. Mayo Clin Proc Mayo Clin. 1998;73:943–947. doi: 10.4065/73.10.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rechner P.M., Agger W.A., Mruz K., Cogbill T.H. Clinical features of clostridial bacteremia: a review from a rural area. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:349–353. doi: 10.1086/321883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.García-Lechuz J.M., Hernangómez S., Juan R.S., Peláez T., Alcalá L., Bouza E. Extra-intestinal infections caused by Clostridium difficile. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001;7:453–457. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2001.00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng L., Citron D.M., Genheimer C.W. Molecular characterization and antimicrobial susceptibilities of extra-intestinal Clostridium difficile isolates. Anaerobe. 2007;13:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leal J., Gregson D.B., Ross T., Church D.L., Laupland K.B. Epidemiology of clostridium species bacteremia in calgary, Canada, 2000–2006. J Infect. 2008;57:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McGill F., Fawley W.N., Wilcox M.H. Monomicrobial Clostridium difficile bacteraemias and relationship to gut infection. J Hosp Infect. 2011;77:170–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Health Protection agency . 2009. Uncommon pathogens associated with bacteraemia in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. 2003–2008 report. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Health Protection agency . 2013. Uncommon pathogens associated with bacteraemia in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. 2008–2012 report. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Health Protection agency . 2015. Uncommon pathogens involved in bacteraemia in England, Wales and Northern Ireland; pp. 2010–2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brook I., Avery G., Glasgow A. Clostridium difficile in paediatric infections. J Infect. 1982;4:253–257. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(82)92584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bouza E., Del Vecchio M.G., Reigadas E. Spectrum of Clostridium difficile infections: particular clinical situations. Anaerobe. 2016;37:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levett P.N. Clostridium difficile in habitats other than the human gastro-intestinal tract. J Infect. 1986;12:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(86)94294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee N.-Y., Huang Y.-T., Hsueh P.-R., Ko W.-C. Clostridium difficile bacteremia, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1204–1210. doi: 10.3201/eid1608.100064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jacobs A., Barnard K., Fishel R., Gradon J.D. Extracolonic manifestations of Clostridium difficile infections: presentation of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2001;80:88–101. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200103000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daruwala C., Mercogliano G., Newman G., Ingerman M.J. Bacteremia due to clostridium difficile: case report and review of the literature. Clin Med Case Rep. 2009;2:5–9. doi: 10.4137/ccrep.s2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elliott B., Reed R., Chang B.J., Riley T.V. Bacteremia with a large clostridial toxin-negative, binary toxin-positive strain of Clostridium difficile. Anaerobe. 2009;15:249–251. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gérard M., Defresne N., Van der Auwera P., Meunier F. Polymicrobial septicemia with Clostridium difficile in acute diverticulitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989;8:300–302. doi: 10.1007/BF01963455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Durojaiye O., Gaur S., Alsaffar L. Bacteraemia and breast abscess: unusual extra-intestinal manifestations of Clostridium difficile infection. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60:378–380. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.027409-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hemminger J., Balada-Llasat J.-M., Raczkowski M., Buckosh M., Pancholi P. Two case reports of Clostridium difficile bacteremia, one with the epidemic NAP-1 strain. Infection. 2011;39:371–373. doi: 10.1007/s15010-011-0115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eckert C., Coignard B., Hebert M. Clinical and microbiological features of Clostridium difficile infections in France: the ICD-RAISIN 2009 national survey. Méd Mal Infect. 2013;43:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kazanji N., Gjeorgjievski M., Yadav S., Mertens A.N., Lauter C. Monomicrobial vs polymicrobial clostridium difficile bacteremia: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Med. 2015;128:e19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alpern R.J., Dowell V.R. Nonhistotoxic clostridial bacteremia. Am J Clin Pathol. 1971;55:717–722. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/55.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ellner P.D., Granato P.A., May C.B. Recovery and identification of anaerobes: a system suitable for the routine clinical laboratory. Appl Microbiol. 1973;26:904–913. doi: 10.1128/am.26.6.904-913.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mattila E., Arkkila P., Mattila P.S., Tarkka E., Tissari P., Anttila V.-J. Extraintestinal clostridium difficile infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:e148–153. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saginur R., Fogel R., Begin L., Cohen B., Mendelson J. Splenic abscess due to Clostridium difficile. J Infect Dis. 1983;147:1105. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.6.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Genta V.M., Gilligan P.H., McCarthy L.R. Clostridium difficile peritonitis in a neonate. A case report. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1984;108:82–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spencer R.C., Courtney S.P., Nicol C.D. Polymicrobial septicaemia due to Clostridium difficile and Bacteroides fragilis. Br Med J Clin Res Ed. 1984;289:531–532. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6444.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rampling A., Warren R.E., Bevan P.C., Hoggarth C.E., Swirsky D., Hayhoe F.G. Clostridium difficile in haematological malignancy. J Clin Pathol. 1985;38:445–451. doi: 10.1136/jcp.38.4.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Studemeister A.E., Beilke M.A., Kirmani N. Splenic abscess due to Clostridium difficile and Pseudomonas paucimobilis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:389–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Byl B., Jacobs F., Struelens M.J., Thys J.P. Extraintestinal clostridium difficile infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:712. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.4.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cid A., Juncal A.R., Aguilera A., Regueiro B.J., González V. Clostridium difficile bacteremia in an immunocompetent child. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1167–1168. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.1167-1168.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Duthilly A., Blanckaert K., Thielemans B., Simon M., Cattoen C. [Clostridium difficile bacteremia] Presse Médicale Paris Fr 1983. 2001;30:1825–1826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakamur I., Kunihiro M., Kato H. Bacteremia due to Clostridium difficile. Kansenshōgaku Zasshi J Jpn Assoc Infect Dis. 2004;78:1026–1030. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.78.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Choi J.-L., Kim B.-R., Kim J.-E. A case of Clostridium difficile bacteremia in a patient with loop ileostomy. Ann Lab Med. 2013;33:200–202. doi: 10.3343/alm.2013.33.3.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kaufman E., Liska D., Rubinshteyn V., Nandakumar G. Clostridium difficile bacteremia. Surg Infect. 2013;14(6):559–560. doi: 10.1089/sur.2013.055. published online Oct 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bergamo D. Clostridium difficile bacteremia in a neonate. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2016 doi: 10.1177/0009922816664068. published online Aug 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]