Abstract

The series of events underlying the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease (AD) in unknown. The most widely-accepted hypothesis is called the amyloid cascade, based on the observation that the brains of AD patients contain high levels of extracellular plaques, composed mainly of β-amyloid (Aβ), and intracellular tangles, composed of hyperphosphorylated forms of the microtubule-associated protein tau. However, AD is also characterized by other features, including aberrant cholesterol, phospholipid, and calcium metabolism, and mitochondrial dysfunction, all ostensibly unrelated to plaque and tangle formation. Notably, these “other” aspects of AD pathology are functions related to mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAM), a subdomain of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that is apposed to, and communicates with, mitochondria. Given the potential relationship between MAM and AD, we explored the possibility that perturbed MAM function might play a role in AD pathogenesis. We found that γ-secretase activity, which processes the amyloid precursor protein to generate Aβ, is located predominantly in the MAM, and that ER-mitochondrial apposition and MAM function are increased significantly in cells from AD patients. These observations may help explain not only the aberrant Aβ production, but also many of the “other” biochemical and morphological features of the disease. Based on these, and other, data we propose that AD is fundamentally a disorder of ER-mitochondrial hyperconnectivity.

Alzheimer disease

Alzheimer disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative dementia of aging [1]. It is defined operationally as a disorder in which there is an accumulation of extracellular neuritic plaques and intracellular tangles in the brain [1]. The plaques are composed of numerous proteins [2,3], but foremost among them is β-amyloid (Aβ). The tangles are more homogeneous and consist mainly of aggregates of hyperphosphorylated forms of the microtubule-associated protein tau [1,4].

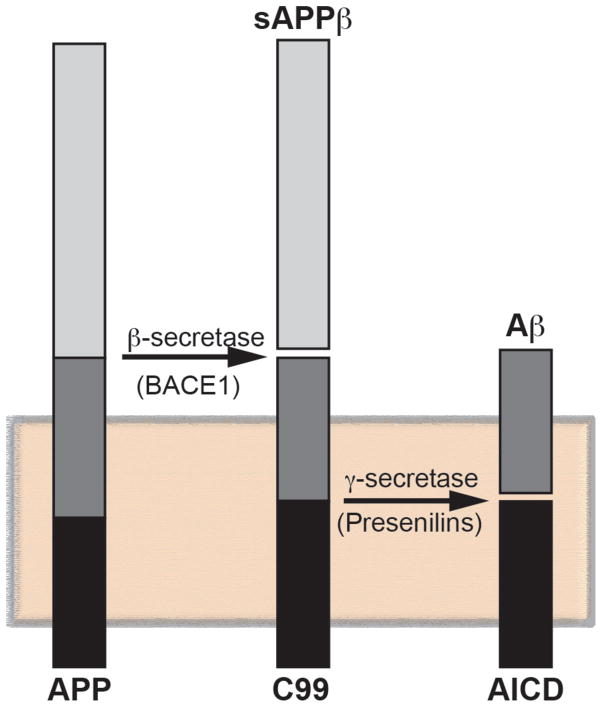

The familial form of AD (FAD), which affects ~1% of all patients, is inherited as an autosomal-dominant trait, and is caused by mutations in one of three genes: presenilin-1 (PS1), presenilin-2 (PS2), and the amyloid precursor protein (APP). PS1 and PS2 are aspartyl proteases that are the enzymatically active components of the γ-secretase complex that, together with β-secretase (BACE1), processes APP to produce Aβ, thereby likely explaining the deposition of amyloid in these patients (Fig. 1). In sporadic AD (SAD), which comprises the vast majority of cases, the mechanistic connection to amyloid deposition is far less clear. However, individuals harboring the ε4 allele of apolipoprotein E (hereinafter ApoE4), which is a component of lipoproteins that are involved in intercellular cholesterol trafficking, are at significantly higher risk for developing AD than those harboring the more common ε3 allele [5,6]; the reason for this elevated risk is unknown.

Figure 1. Amyloidogenic processing of APP.

Consecutive cleavages of APP, a membrane-tethered protein (shaded box), by BACE1 (to produce C99 and soluble APPβ) and γ-secretase (containing PS1 or PS2) generate Aβ and the APP intracellular domain (AICD).

The amyloid cascade hypothesis

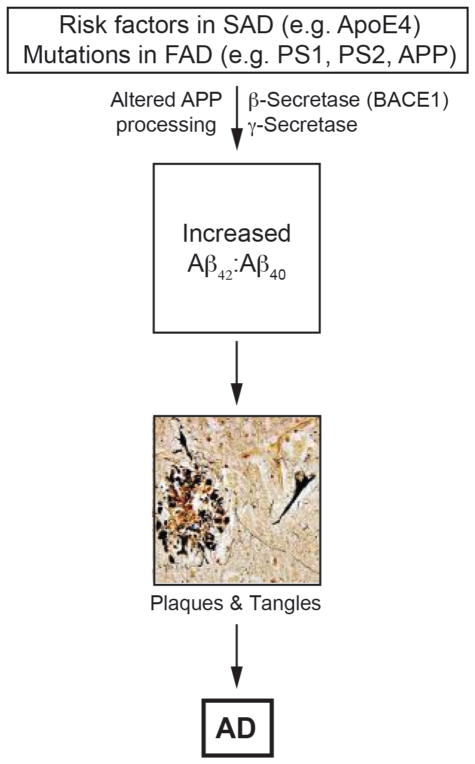

The pathogenetic mechanism that causes AD is unknown, but the discovery that mutations in presenilins (which cleave APP) and in APP itself (which is a substrate of the presenilin-containing γ-secretase complex) in FAD patients gave rise to the most dominant, and commonly-accepted, hypothesis to explain pathogenicity in both FAD and SAD, namely the “amyloid cascade” [7]. The hypothesis proposes that the disease arises when APP is cleaved by BACE1 to produce a 99-aa C-terminal fragment (C99), which is then cleaved by γ-secretase to produce a ~50-aa APP intracellular domain (AICD) and a range of Aβ fragments that average ~40-aa in length in normal individuals but ~42-aa in AD (Fig. 1), with a concomitant increase in the ratio of Aβ42:Aβ40. As opposed to Aβ40, Aβ42 is fibrillogenic and accumulates in the plaques. This amyloid is toxic to cells, and the resulting stress promotes tau hyperphosphorylation, leading to the tangles, with both the extraneuritic plaques and the intraneuronal tangles conspiring to cause the disease by promoting cell death [4,7] (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. The amyloid cascade hypothesis.

Aberrant APP processing gives rise to plaques and then tangles (reproduced from [71], with permission). See text for details.

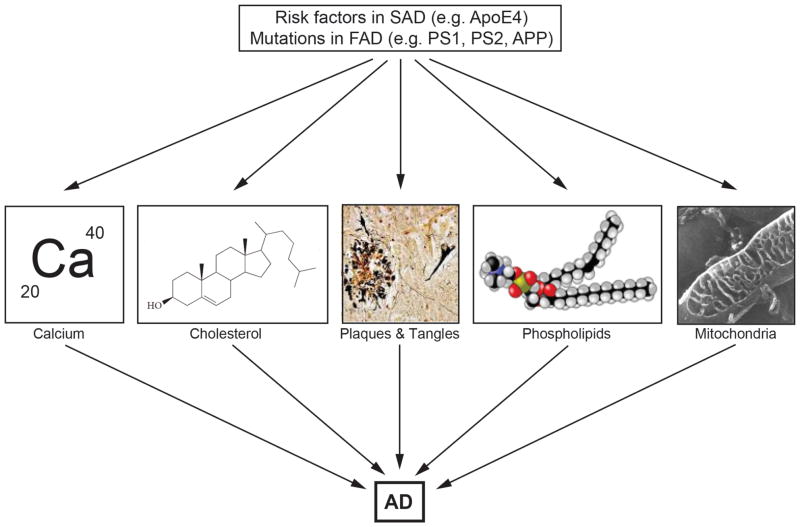

The amyloid cascade hypothesis is compelling, not only because it unites findings from many different approaches to the disease, but also because it explains why mutations in both the γ-secretase enzyme (i.e. PS1, PS2) and its substrate (i.e. APP) cause FAD. However, besides the obvious problem of the lack of mutations in these three proteins in SAD, a nagging concern has been that the amyloid cascade does not address a number of issues that are central to both understanding and explaining AD pathogenesis. In particular, AD is associated with other features that have received less attention in the field, because there is no unifying conceptual framework within the amyloid cascade that would explain their occurrence [8,9]. These include altered cholesterol [10], fatty acid [11], glucose [12,13], and phospholipid [14] metabolism, aberrant calcium homeostasis [15], and mitochondrial dysfunction [16] (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Other features of Alzheimer disease.

Besides plaques and tangles [71], AD is also characterized by perturbations in calcium homeostasis, cholesterol metabolism, phospholipid metabolism, and dynamics and function of mitochondria [72].

Mitochondria-associated ER membranes

As a group focused predominantly on human mitochondrial biology, function, and disease [17], we noticed that there was a common theme that had the potential to unite these disparate features of AD under a single rubric, namely mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAM). MAM is a subdomain of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that communicates with mitochondria, both physically and biochemically [18–21]. Among the proteins enriched in or localized to the MAM are those involved in lipid metabolism (e.g. phosphatidylserine synthase [22,23]), in cholesterol metabolism (e.g. acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase 1 [ACAT1] [21] and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein [24]), in calcium homeostasis (e.g. IP3 receptors [25,26]), in lipid transfer between the ER and mitochondria (e.g. fatty acid transfer protein 4 [27]), and in the maintenance of mitochondrial function (e.g. voltage-dependent anion channel 2 [24]) and morphology (e.g dynamin-related protein 1 [28]); notably, these MAM-related functions are the very ones that are perturbed in AD. In addition, other proteins stabilize and regulate the interaction of ER and mitochondria, including mitofusin 2 [29] and phosphofurin acidic cluster sorting protein 2 [30], but the exact “tethering” mechanism is unknown.

Based on the supposition that MAM might play a role in AD pathogenesis, we and others found that PS1 and PS2 [31,32], and γ-secretase activity itself [31,33], are localized predominantly at the MAM. This localization could account for the reported localizations of Aβ [34] and PS1 [35] to mitochondria. In addition, the finding that MAM is an intracellular lipid raft [36,37] supports the view that the lipid rafts in which PS1 and γ-secretase activity are known to reside [38] are located not only at the plasma membrane [31,39] but also intracellularly, at the MAM [36,37].

MAM function is perturbed in AD

Given the enrichment of the presenilins and of γ-secretase activity in the MAM, we explored the possibility that MAM function might be altered in AD, minimally in presenilin-mutant cells and in cells from FAD patients harboring mutations in presenilin (FADPS). Some AD-relevant aspects of MAM behavior, such as calcium metabolism and mitochondrial function, have been studied in great detail by others, albeit not in the context of MAM. For example, there is a rather large literature showing that calcium trafficking, which is fundamentally a MAM-mediated process [19,40,41], is altered in AD patients [42–44], in patient fibroblasts [45–47], and in PS1-mutant mice [48]. Similarly, mitochondrial function, including bioenergetics and mitochondrial dynamics, have also been shown to be altered significantly in AD [46,49–55]. Thus, the changes found in calcium and mitochondrial function in AD are almost certainly due to perturbed ER-mitochondrial communication at the MAM. We therefore decided to study other aspects of MAM function that are relevant to AD but that have received less attention, focusing on phospholipid [14] and cholesterol [10] homeostasis in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) lacking presenilins, in PS1-knockdown MEFs, and in fibroblasts from FADPS patients.

In broad view, phospholipid synthesis takes place in two compartments: the cytoplasm (via the “Kennedy” pathway) and the MAM [56]. In the MAM, phosphatidylserine (PtdSer) translocates from the ER to mitochondria, where it is converted to phosphatidylethanolamine (PtdEtn); PtdEtn then travels back to the ER to be converted into phosphatidylcholine [57]. We found that PtdSer and PtdEtn synthesis and transport were increased significantly in PS-mutant cells and FADPS fibroblasts [36], indicating upregulated ER-mitochondrial cross-talk in those cells. These results are consistent with, and may help explain, the altered phospholipid profiles seen in FAD patients [14].

In addition to phospholipid synthesis and transport, we measured another MAM-localized activity [21,36], namely, the intracellular conversion by ACAT1 (gene SOAT1) of free cholesterol to cholesteryl esters (CE) that are then stored in cytoplasmic lipid droplets [58]. We found significantly more CE in the PS-mutant and FADPS fibroblasts than in the corresponding control cells [36]. Notably, the increase in CE in these cells was parallelled by a concomitant increase in cytoplasmic neutral lipid droplets (containing CE) [36], indicating that these cells were trying to maintain cholesterol homeostasis [58] by reducing excess free cholesterol that would otherwise be toxic to the cells [59]. We note that patients with AD have elevated circulating cholesterol [10] and increased lipid droplet formation [60,61], and that ACAT1 activity appears to be required for the production of Aβ [58,62], but the reasons for these observations are currently unknown.

Remarkably, these findings on altered MAM-mediated phospholipid and cholesterol homeostasis and on increased ER-mitochondrial apposition were not limited to presenilin-mutant cells. We obtained essentially identical results in fibroblasts from FAD patients with mutations in APP, and even more notably, in fibroblasts from patients with SAD [36]. The fact that lipid dyshomeostasis and altered MAM morphology could be observed in AD cells in which the presenilin and/or APP genes are normal implies that upregulated ER-mitochondrial communication and dysregulated MAM function are likely to be a general property of cells from essentially all AD patients, and that altered MAM behavior is a pathogenetic event upstream of plaque and tangle formation.

The idea that perturbed MAM behavior is a precipitating event in AD was reinforced by recent work on the differential effects of ApoE4 vs ApoE3 on MAM function [63]. Specifically, human fibroblasts and neuronal-like SH-SY5Y cells treated with astrocyte-conditioned media (ACM) from knock-in mice expressing human ApoE4 upregulated MAM function to a significantly greater extent than did ACM from ApoE3 knock-in mice [63]. Moreover, the effects of ApoE4 were apparently due to its role as a component of lipoproteins, not as the free, unlipidated protein [63], implying that its effects on MAM were related to its function in lipoprotein-mediated cholesterol trafficking and metabolism. We note that ApoE4 is recycled less efficiently than is ApoE3 [64,65], thereby causing cholesterol to accumulate in endosomes and lysosomes, which can then traffic to the ER [66]. Thus, the increase in CE and lipid droplets seen in ApoE4-ACM-treated cells may well have reflected a concomitant increase in cholesterol metabolism at the MAM. Thus, ApoE4 in SAD cells appears to mimic the effects of upregulated cholesterol metabolism in FAD cells, and may help explain, in part, the contribution of ApoE4 as a risk factor in the disease. This supposition is also consistent with the identification of allelic variants in other cholesterol metabolism-related genes as risk factors in AD [67], including ABCA7 [68], which promotes the cellular efflux of both phospholipids and cholesterol [69].

The MAM hypothesis

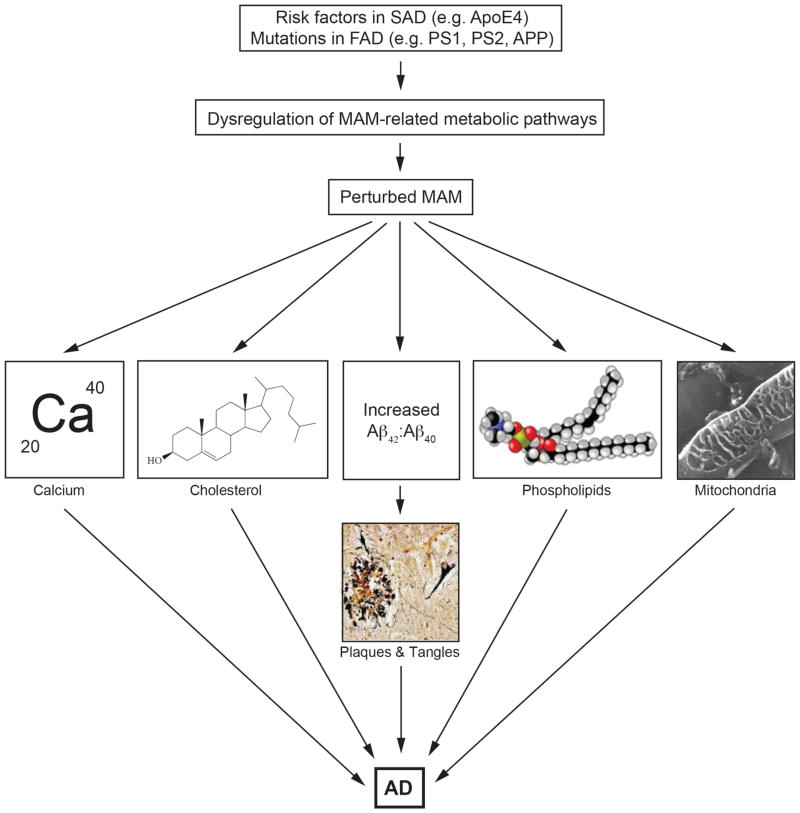

Based on the findings summarized above, we propose that the pathogenesis of AD is mediated by increased ER-mitochondrial communication, which in turn alters the function of proteins that reside at the interface of these two organelles, both in degree and in kind (Fig. 4). The increase in ER-mitochondrial apposition would be consistent with, and perhaps explain, the increased calcium trafficking between the two organelles [15,42–44], the aberrant phospholipid profiles [14], the perturbed cholesterol homeostasis [10], the changes in mitochondrial function, morphology, and distribution [16,46,49–55], and the increased Aβ42:Aβ40 ratio seen in AD (Fig. 4). On this last point, we believe that the altered ER membrane topology at the MAM in AD [70] could explain the shift in the location of the γ-secretase cleavage site on APP-C99 away from Aβ40 and towards Aβ42 [9].

Figure 4. The MAM hypothesis.

The hypothesis proposes that the functional cause of AD is upregulated ER-mitochondria communication at the MAM. This results in alterations in the indicated functions, as well as an increase in the Aβ42:Aβ40 ratio; the plaques and tangles arise as a downstream result of that perturbation. The increased ER-mitochondrial connectivity is the result of a derangement in specific biochemical pathways brought on by mutations in PS’s and APP (in the case of FAD) or by other causes (in the case of SAD).

Taken together, our findings support the view that the functional cause of AD is increased ER-mitochondrial communication and upregulated MAM function. However, the biochemical cause of ER-mitochondrial hyperconnectivity, and its relationship to aberrant APP processing, are currently unclear. Work to elucidate these upstream causes of perturbed MAM structure and function is currently under way.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (K01 AG045335 to EA-G), the U.S. Department of Defense (W911F-15-1-0169 to EAS), and the J. Willard and Alice S. Marriott Foundation (to EAS).

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM. Alzheimer’s disease. New Eng J Med. 2010;362:329–344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong RA, Lantos PL, Cairns NJ. What determines the molecular composition of abnormal protein aggregates in neurodegenerative disease? Neuropathology. 2008;28:351–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2008.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atwood CS, Martins RN, Smith MA, Perry G. Senile plaque composition and posttranslational modification of amyloid-β peptide and associated proteins. Peptides. 2002;23:1343–1350. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(02)00070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s disease. Cold Spr Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a004457. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holtzman DM, Herz J, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and apolipoprotein E receptors: normal biology and roles in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spr Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006312. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang Y. Aβ-independent roles of apolipoprotein E4 in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schon EA, Area-Gomez E. Is Alzheimer’s disease a disorder of mitochondria-associated membranes? J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20:S281–S292. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schon EA, Area-Gomez E. Mitochondria-associated ER membranes in Alzheimer disease. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2013;55:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stefani M, Liguri G. Cholesterol in Alzheimer’s disease: unresolved questions. Curr Alz Res. 2009;6:15–29. doi: 10.2174/156720509787313899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraser T, Tayler H, Love S. Fatty acid composition of frontal, temporal and parietal neocortex in the normal human brain and in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Res. 2010;35:503–513. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-0087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoyer S, Oesterreich K, Wagner O. Glucose metabolism as the site of the primary abnormality in early-onset dementia of Alzheimer type? J Neurol. 1988;235:143–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00314304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu F, Shi J, Tanimukai H, Gu J, Gu J, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Gong CX. Reduced O-GlcNAcylation links lower brain glucose metabolism and tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2009;132:1820–1832. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pettegrew JW, Panchalingam K, Hamilton RL, McClure RJ. Brain membrane phospholipid alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Res. 2001;26:771–782. doi: 10.1023/a:1011603916962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bezprozvanny I, Mattson MP. Neuronal calcium mishandling and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Su B, Zheng L, Perry G, Smith MA, Zhu X. The role of abnormal mitochondrial dynamics in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2009;109:153–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05867.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Area-Gomez E, Schon EA. Mitochondrial genetics and disease. J Child Neurol. 2014;29:1208–1215. doi: 10.1177/0883073814539561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18••.Csordas G, Renken C, Varnai P, Walter L, Weaver D, Buttle KF, Balla T, Mannella CA, Hajnoczky G. Structural and functional features and significance of the physical linkage between ER and mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:915–921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604016. This paper, along with a follow-on paper in 2010 (Ref. 40), provided some of the key structural, morphological, and biochemical data supporting the physical and biochemical connectivity between ER and mitochondria at the MAM, focusing on the transfer of calcium between the two organelles. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19•.Hayashi T, Rizzuto R, Hajnoczky G, Su TP. MAM: more than just a housekeeper. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.12.002. An excellent review on MAM structure and function. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raturi A, Simmen T. Where the endoplasmic reticulum and the mitochondrion tie the knot: the mitochondria-associated membrane (MAM) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:213–224. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rusinol AE, Cui Z, Chen MH, Vance JE. A unique mitochondria-associated membrane fraction from rat liver has a high capacity for lipid synthesis and contains pre-Golgi secretory proteins including nascent lipoproteins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27494–27502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vance DE, Walkey CJ, Cui Z. Phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase from liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1348:142–150. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(97)00108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stone SJ, Vance JE. Phosphatidylserine synthase-1 and −2 are localized to mitochondria-associated membranes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34534–34540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prasad M, Kaur J, Pawlak KJ, Bose M, Whittal RM, Bose HS. Mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane (MAM) regulates steroidogenic activity via steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR)-voltage-dependent anion channel 2 (VDAC2) interaction. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:2604–2616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.605808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendes CC, Gomes DA, Thompson M, Souto NC, Goes TS, Goes AM, Rodrigues MA, Gomez MV, Nathanson MH, Leite MF. The type III inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor preferentially transmits apoptotic Ca2+ signals into mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40892–40900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szabadkai G, Bianchi K, Varnai P, De Stefani D, Wieckowski MR, Cavagna D, Nagy AI, Balla T, Rizzuto R. Chaperone-mediated coupling of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial Ca2+ channels. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:901–911. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jia W, Moulson CL, Pei Z, Miner JH, Watkins PA. Fatty acid transport protein 4 is the principal very long chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetase in skin fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20573–20583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedman JR, Lackner LL, West M, DiBenedetto JR, Nunnari J, Voeltz GK. ER tubules mark sites of mitochondrial division. Science. 2011;334:358–362. doi: 10.1126/science.1207385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Brito OM, Scorrano L. Mitofusin 2 tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature. 2008;456:605–610. doi: 10.1038/nature07534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30•.Simmen T, Aslan JE, Blagoveshchenskaya AD, Thomas L, Wan L, Xiang Y, Feliciangeli SF, Hung CH, Crump CM, Thomas G. PACS-2 controls endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria communication and Bid-mediated apoptosis. EMBO J. 2005;24:717–729. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600559. This study was among the first to identify a specific protein - PACS2 - that regulates ER-mitochondral apposition in mammalian cells, including an unexpected relationship of this apposition to apoptosis, via tBID. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31••.Area-Gomez E, de Groof AJ, Boldogh I, Bird TD, Gibson GE, Koehler CM, Yu WH, Duff KE, Yaffe MP, Pon LA, et al. Presenilins are enriched in endoplasmic reticulum membranes associated with mitochondria. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:1810–1816. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090219. This was the first paper to report the enrichment of presenilins and γ-secretase activity in the MAM subdomain of the ER. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newman M, Wilson L, Verdile G, Lim A, Khan I, Moussavi Nik SH, Pursglove S, Chapman G, Martins RN, Lardelli M. Differential, dominant activation and inhibition of Notch signalling and APP cleavage by truncations of PSEN1 in human disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:602–617. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schreiner B, Hedskog L, Wiehager B, Ankarcrona M. Amyloid-β peptides are generated in mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43:369–374. doi: 10.3233/JAD-132543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Du H, Guo L, Fang F, Chen D, Sosunov AA, McKhann GM, Yan Y, Wang C, Zhang H, Molkentin JD, et al. Cyclophilin D deficiency attenuates mitochondrial and neuronal perturbation and ameliorates learning and memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2008;14:1097–1105. doi: 10.1038/nm.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansson CA, Frykman S, Farmery MR, Tjernberg LO, Nilsberth C, Pursglove SE, Ito A, Winblad B, Cowburn RF, Thyberg J, et al. Nicastrin, presenilin, APH-1, and PEN-2 form active γ-secretase complexes in mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51654–51660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404500200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36••.Area-Gomez E, Del Carmen Lara Castillo M, Tambini MD, Guardia-Laguarta C, de Groof AJC, Madra M, Ikenouchi J, Umeda M, Bird TD, Sturley SL, et al. Upregulated function of mitochondria-associated ER membranes in Alzheimer disease. EMBO J. 2012;31:4106–4123. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.202. This paper analyzed the role of MAM in the pathogenesis of AD. It showed that ER-mitochondrial apposition is increased massively in presenilin-mutant and AD cells, and that MAM function (e.g. cholesteryl ester synthesis; phospholipid transfer) is increased as well. It proposed that many of the phenotypes of AD could be explained by perturbed MAM structure and function. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37•.Hayashi T, Fujimoto M. Detergent-resistant microdomains determine the localization of sigma-1 receptors to the endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria junction. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77:517–528. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.062539. One of the first papers to identify MAM as an intracellular lipid raft-like domain. This finding helped resolve the paradox of the intracellular localization of presenilins and γ-secretase activity to rafts, which had been thought by many to be present only at the plasma membrane. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vetrivel KS, Cheng H, Lin W, Sakurai T, Li T, Nukina N, Wong PC, Xu H, Thinakaran G. Association of γ-secretase with lipid rafts in post-Golgi and endosome membranes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44945–44954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407986200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marambaud P, Shioi J, Serban G, Georgakopoulos A, Sarner S, Nagy V, Baki L, Wen P, Efthimiopoulos S, Shao Z, et al. A presenilin-1/γ-secretase cleavage releases the E-cadherin intracellular domain and regulates disassembly of adherens junctions. EMBO J. 2002;21:1948–1956. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.8.1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Csordas G, Varnai P, Golenar T, Roy S, Purkins G, Schneider TG, Balla T, Hajnoczky G. Imaging interorganelle contacts and local calcium dynamics at the ER-mitochondrial interface. Mol Cell. 2010;39:121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patergnani S, Suski JM, Agnoletto C, Bononi A, Bonora M, De Marchi E, Giorgi C, Marchi S, Missiroli S, Poletti F, et al. Calcium signaling around mitochondria associated membranes (MAMs) Cell Commun Signal. 2011;9:19. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-9-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liang J, Kulasiri D, Samarasinghe S. Ca2+ dysregulation in the endoplasmic reticulum related to Alzheimer’s disease: a review on experimental progress and computational modeling. BioSystems. 2015;134:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mattson MP. ER calcium and Alzheimer’s disease: in a state of flux. Science Signal. 2010;3:pe10. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3114pe10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Supnet C, Bezprozvanny I. Neuronal calcium signaling, mitochondrial dysfunction, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 2):S487–S498. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gibson GE, Vestling M, Zhang H, Szolosi S, Alkon D, Lannfelt L, Gandy S, Cowburn RF. Abnormalities in Alzheimer’s disease fibroblasts bearing the APP670/671 mutation. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:573–580. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00149-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peterson C, Goldman JE. Alterations in calcium content and biochemical processes in cultured skin fibroblasts from aged and Alzheimer donors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:2758–2762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.8.2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sims NR, Finegan JM, Blass JP. Altered metabolic properties of cultured skin fibroblasts in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1987;21:451–457. doi: 10.1002/ana.410210507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun S, Zhang H, Liu J, Popugaeva E, Xu N-J, Feske S, White CL, 3rd, Bezprozvanny I. Reduced synaptic STIM2 expression and impaired store-operated calcium entry cause destabilization of mature spines in mutant presenilin mice. Neuron. 2014;82:79–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cho D-H, Nakamura T, Fang J, Cieplak P, Godzik A, Gu Z, Lipton SA. S-nitrosylation of Drp1 mediates β-amyloid-related mitochondrial fission and neuronal injury. Science. 2009;324:102–105. doi: 10.1126/science.1171091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferrer I. Altered mitochondria, energy metabolism, voltage-dependent anion channel, and lipid rafts converge to exhaust neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. J Bioenerget Biomembr. 2009;41:425–431. doi: 10.1007/s10863-009-9243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gibson GE, Huang H-M. Mitochondrial enzymes and endoplasmic reticulum calcium stores as targets of oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. J Bioenerget Biomembr. 2004;36:335–340. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBB.0000041764.45552.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Riemer J, Kins S. Axonal transport and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegener Dis. 2013;12:111–124. doi: 10.1159/000342020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stokin GB, Lillo C, Falzone TL, Brusch RG, Rockenstein E, Mount SL, Raman R, Davies P, Masliah E, Williams DS, et al. Axonopathy and transport deficits early in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2005;307:1282–1288. doi: 10.1126/science.1105681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang X, Su B, Siedlak SL, Moreira PI, Fujioka H, Wang Y, Casadesus G, Zhu X. Amyloid-β overproduction causes abnormal mitochondrial dynamics via differential modulation of mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19318–19323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804871105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Young-Collier KJ, McArdle M, Bennett JP. The dying of the light: mitochondrial failure in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;28:771–781. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-111487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Flis VV, Daum G. Lipid transport between the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a013235. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a013235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voelker DR. Bridging gaps in phospholipid transport. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Puglielli L, Konopka G, Pack-Chung E, Ingano LA, Berezovska O, Hyman BT, Chang TY, Tanzi RE, Kovacs DM. Acyl-coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase modulates the generation of the amyloid β-peptide. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:905–912. doi: 10.1038/ncb1001-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feng B, Yao PM, Li Y, Devlin CM, Zhang D, Harding HP, Sweeney M, Rong JX, Kuriakose G, Fisher EA, et al. The endoplasmic reticulum is the site of cholesterol-induced cytotoxicity in macrophages. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:781–792. doi: 10.1038/ncb1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gómez-Ramos P, Asunción Morán M. Ultrastructural localization of intraneuronal Aβ-peptide in Alzheimer disease brains. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;11:53–59. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-11109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pani A, Dessì S, Diaz G, La Colla P, Abete C, Mulas C, Angius F, Cannas MD, Orru CD, Cocco PL, et al. Altered cholesterol ester cycle in skin fibroblasts from patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18:829–841. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62••.Puglielli L, Ellis BC, Ingano LA, Kovacs DM. Role of acyl-coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase activity in the processing of the amyloid precursor protein. J Mol Neurosci. 2004;24:93–96. doi: 10.1385/JMN:24:1:093. Together with a previous report in 2001 (Ref. 58), this paper made the remarkable observation that ablation of ACAT1, an enzyme required for the intra-cellular esterification of cholesterol (and which is enriched in the MAM), is required for the production of Aβ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63•.Tambini MD, Pera M, Kanter E, Yang H, Guardia-Laguarta C, Holtzman D, Sulzer D, Area-Gomez E, Schon EA. ApoE4 upregulates the activity of mitochondria-associated ER membranes. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:27–36. doi: 10.15252/embr.201540614. This paper showed that the ε4 allele of APOE, the greatest biochemical risk factor for developing sporadic AD, affects MAM function preferentially to the ε3 allele. As such, it provides support for the MAM hypothesis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heeren J, Grewal T, Laatsch A, Rottke D, Rinninger F, Enrich C, Beisiegel U. Recycling of apoprotein E is associated with cholesterol efflux and high density lipoprotein internalization. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14370–14378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heeren J, Grewal T, Laatsch A, Becker N, Rinninger F, Rye K-A, Beisiegel U. Impaired recycling of apolipoprotein E4 is associated with intracellular cholesterol accumulation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55483–55492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ikonen E. Cellular cholesterol trafficking and compartmentalization. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:125–138. doi: 10.1038/nrm2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wollmer MA. Cholesterol-related genes in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:762–773. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Steinberg S, Stefansson H, Jonsson T, Johannsdottir H, Ingason A, Helgason H, Sulem P, Magnusson OT, Gudjonsson SA, Unnsteinsdottir U, et al. Loss-of-function variants in ABCA7 confer risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2015;47:445–447. doi: 10.1038/ng.3246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Abe-Dohmae S, Ikeda Y, Matsuo M, Hayashi M, Okuhira K-i, Ueda K, Yokoyama S. Human ABCA7 supports apolipoprotein-mediated release of cellular cholesterol and phospholipid to generate high density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:604–611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309888200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70•.Winkler E, Kamp F, Scheuring J, Ebke A, Fukumori A, Steiner H. Generation of Alzheimer disease-associated amyloid β42/43 peptide by γ-secretase can be inhibited directly by modulation of membrane thickness. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:21326–21334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.356659. This paper describes a mechanism for increasing the Aβ42:Aβ40 ratio, based more on the biophysical properties of the membrane in which γ-secretase resides than on any particular defect in the enzyme or its substrate. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Perl DP. Neuropathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Mt Sinai J Med. 2010;77:32–42. doi: 10.1002/msj.20157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yoshikane H, Nihei T, Moriyama K. Three-dimensional observation of intracellular membranous structures in dog heart muscle cells by scanning electron microscopy. J Submicrosc Cytol. 1986;18:629–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]