Abstract

Chagas disease is one of the main parasitic diseases found in Latin America and it is estimated that between six and seven million people are infected worldwide. Its etiologic agent, the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi, is transmitted by triatomines, some of which from the genus Rhodnius. Twenty species are currently recognized in this genus, including some closely related species with low levels of morphological differentiation, such as Rhodnius montenegrensis and Rhodnius robustus. In order to investigate genetic differences between these two species, we generated large-scale RNA-sequencing data (consisting of four RNA-seq libraries) from the heads and salivary glands of males of R. montenegrensis and R. robustus. Transcriptome assemblies produced for each species resulted in 64,952 contigs for R. montenegrensis and 70,894 contigs for R. robustus, with N50 of approximately 2,100 for both species. SNP calling based on the more complete R. robustus assembly revealed 3,055 fixed interspecific differences and 216 transcripts with high levels of divergence which contained only fixed differences between the two species. A gene ontology enrichment analysis revealed that these highly differentiated transcripts were enriched for eight GO terms related to AP-2 adaptor complex, as well as other interesting genes that could be involved in their differentiation. The results show that R. montenegrensis and R. robustus have a substantial quantity of fixed interspecific polymorphisms, which suggests a high degree of genetic divergence between the two species and likely corroborates the species status of R. montenegrensis.

Introduction

Chagas disease is a parasitic infection distributed through the Neotropical region. Its etiologic agent is the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi. The main mode of transmission to humans is vectorial, and it is estimated that between six and seven million people are infected worldwide [1]. Triatomines, the vectors of Chagas disease, are exclusively haematophagous during their five nymphal instars and as adult males and females [2]. These vectors are part of the subfamily Triatominae (Hemiptera:Reduviidae), which comprises of five tribes [2, 3]. The tribe Rhodniini consists of two genera: Psammolestes, which includes three species, and Rhodnius containing 20 species, which are found in the Americas [4–6]. The genus Rhodnius has a wide distribution in most of Latin America, with the exception of Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, and Paraguay [2, 4, 7], consisting of tree-dwelling species that use as their main habitat palm tree canopies that shelter mammals. The genus is therefore considered sylvatic [2, 4, 7], but many Rhodnius species are adapting to peridomiciliary and even intradomiciliary environments as a result of the changes to their natural habitats that have been caused by urbanization [8, 9]. For example, whereas Rhodnius prolixus has been found in rural housing all over Latin America [10] Rhodnius stali has been reported to colonize housing in indigenous communities [11, 12]. Rhodnius neglectus has also been found in urban centers far from endemic areas [13, 14]. Therefore, those reports suggest the possibility of Chagas disease transmission by Rhodnius species in domestic environments, whether directly by the vector or indirectly through food contaminated by infected triatomine feces [15].

The identification of species of the genus Rhodnius has been largely based on the observation of at least 19 morphological traits [2, 5]. Even when these features are used, the morphological distinction between Rhodnius species still presents difficulties [16–18]. Examples of specific similarities in the genus Rhodnius are reflected in the description of R. stali [19], which has been grouped with R. pictipes, as well as the description of R. montenegrensis [17], which was incorrectly identified as R. robustus. For the description of R. montenegrensis [17], the authors evaluated previously used morphological traits, classic and geometric morphometry, and a phylogenetic analysis of a portion of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene [16].

In the search for a way to identify closely related species, many authors have resorted to molecular data such as the use of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA marker analyses [20]. However, new methodologies have provided a wider range of possibilities to address this issue [21, 22]. RNA-seq analysis, for example, allows for the identification of polymorphisms in thousands of different transcripts in a faster and much more cost effective way relative to individual gene analysis or genome studies in non-model organisms [23]. Transcriptomes comprise all transcripts that are expressed in a specific tissue and developmental phase, several of which that may play a functional role in the organism; therefore, they may reflect in part phenotypic variation and population differentiation. One interesting aspect of the analysis of transcriptomes among closely related species is the possibility of identification of expressed genes that may have evolved under positive selection, which could be more differentiated, and even involved in the species divergence [24].

The main goal of this study was to search for fixed differences between R. montenegrensis and R. robustus in thousands of transcripts expressed in the cephalic transcriptome of males of both species. The findings showed a substantial number of fixed differences that support the hypothesis that these are genetically distinct species. Hence, the genetic differentiation found in this study confirms the specific status of R. montenegrensis previously reported by Rosa et al. [16].

Methodology

Sampling, dissection, and RNA extraction

The individuals of the species used in this study have been maintained at the Triatominae Insectarium of the Department of Biological Sciences of the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Unesp, Araraquara, São Paulo, Brazil in individually identified glass crystallizers with internal divisions. The specimens are fed on ducks on a monthly basis. Male specimens were separated as fifth instar nymphs. Once they reached the adult phase, they were blood-fed on ducks twice in the first week and not fed seven days before the dissection. Male heads were carefully removed via cervical detachment in order to keep the salivary glands intact. It is important to note that compound eyes were removed from the specimens prior to RNA extraction due to the large quantity of pigments that the reticular cells of these insects exhibit.

Total RNA was extracted using three sets of heads and their respective salivary gland pairs based on a modified version of the TRIzol/chloroform protocol [25], followed by differential precipitation with lithium chloride [26]. Finally, RNA samples were quantified in Qubit and their purity was measured using the standard ratios 260/230 and 260/280 in NanoDrop and visual inspection of RNA bands after agarose gel electrophoresis.

RNA sample preparation and sequencing

Two pools of RNA samples were equimolarly mixed to build each of the four libraries, two for each species. One library with seven samples and another with six for R. montenegrensis were built, as well as two libraries with six samples each for R. robustus, making these libraries independent biological replicates of each species. These libraries were constructed using the TruSeq® RNA Sample Prep kit v2 (Illumina) following the protocol suggested by the manufacturer. Runs were performed in the Illumina HiSeq2500 platform with 2 x 100 bp paired-end reads in the Laboratory for Functional Genomics Applied to Agriculture and Bioenergy of the Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture (ESALQ) at the University of São Paulo (USP) in Brazil.

De novo transcriptome assembly

All reads were trimmed for quality using Phred quality scores and filtered for length using the SeqyClean program, which is available at https://bitbucket.org/izhbannikov/seqyclean. The quality filters were set to “qual 20 20” and “minimum_read_length 50”. SeqyClean was also used to remove any remaining adapter sequences in the reads.

Independent de novo assemblies were performed for each species with reads from their two replicas. To optimize contig assembly, the filtered reads were normalized using the insilico_read_normalization.pl tool, which is included in the Trinity package [27]. In order to avoid redundancy, the maximum read coverage was set to 60. The filtered and normalized reads were assembled using the Trinity software [27]. The quality and completeness of the assemblies were evaluated using BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs) [28]. For this analysis, all transcripts of each assembly were compared with a set of single copy orthologs of Arthropoda.

Coding region (CDS) prediction and functional annotation

The TransDecoder tool included in the Trinity package was used to predict the coding regions based on open reading frames (ORFs) for each species’ assembly, retaining coding regions that were over 100 amino acid residues. We compared the predicted coding regions against the non-redundant (NR) protein GenBank database and the R. prolixus genome [29], available at VectorBase (https://www.vectorbase.org/) based on similarity using Blast program with an E-value threshold of 10−6. The functional annotation was carried out using Blast2GO program [30]. This analysis allows us to associate the CDS with the Gene Ontology (GO) terms that describe gene product attributes considering three different ontologies, Biological Process, Molecular Function and Cellular Component. The annotations were analyzed in the WEGO software (http://wego.genomics.org.cn/cgi-bin/wego/index.pl) to produce the distribution of GO terms at level 2 for each species’ transcriptome. An enrichment analysis of the highly differentiated contigs on the GO terms was performed using the TopGO program [31], retaining the significantly enriched contrasts at the 0.05 significance level after FDR correction using the method of Benjamini and Hochberg [32].

Sequence alignment and Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNP) calling

To avoid redundancy in the mapping of the R. robustus assembly, only the largest isoforms from each unigene detected during the assembly process were kept. This way, a single transcript was selected for each set of isoforms (unigene). The filtered reads from each species were mapped against the R. robustus assembly, which was taken as a reference transcriptome using the default settings of the Bowtie2 program [33]. The files containing the mapped reads were converted into the pileup format using the mpileup tool of the Samtools program, version 0.18 (http://samtools.sourceforge.net). The software VarScan 2 was then used to call the intra and interspecific SNPs [34] by means of the mpileup2snp command. The analyses relied on a minimum coverage of 42, a minimum mapping quality score of 30, and a Phred quality score greater than or equal to 30. (commands used in each step are available in the S1 Table).

In order to select a group of candidate transcripts that showed the greatest level of divergence between the two species, the index of interspecific differentiation (D) [35] was estimated based on the allele frequencies estimated by VarScan 2. The D variable, which is defined as the absolute value of the difference between the allele frequencies of an SNP from R. montenegrensis and R. robustus (D = │FRm—FRr│), was calculated. Furthermore, the average D value was estimated including the SNPs from a particular transcript () [35]. In the search for possible candidate genes involved in the process of speciation, transcripts including only fixed variants ( = 1) were used.

Test of selection

The ratio of non-synonymous and synonymous rates (Ka/Ks) was used to identify potential transcripts evolving under positive selection. Ka/Ks > 1 indicates signal of natural selection, Ka/Ks < 1 purifying selection and Ka/Ks = 0 neutrality [36]. This analysis was carried out through a search for ortholog CDSs using best hit reciprocal Blast strategy and an e-value threshold of 10−12. The pairs of ortholog CDSs were translated into protein, and aligned using muscle algorithm [37] and then back translated to DNA using software TranslatorX [38]. The Ka/Ks values were estimated using the model selection criterion implemented in the software Kaks_Calculator [39]. Pair of CDSs with Ks ≥ 1 may be paralogs, so they were removed from the analysis.

Results and discussion

De novo transcriptome assembly

The four RNA libraries (two replicas per species) generated 131,250,862 paired-end 100 base pairs (bp) reads, an average of 32.8 million reads per library. The produced reads were filtered by quality, resulting in 124,601,286 paired-end reads and an average of more than 31 million reads per replica in the two species studied (Table 1). RNA-Seq data were de novo assembled per species using Trinity leading to the production of 53,042 and 56,756 contigs for R. montenegrensis and R. robustus assemblies, respectively, with similar N50 of about 2,100. However, N50 is not an appropriate measure of quality for transcriptome assemblies because it is dependent on the transcript lengths that vary between species and even between tissues. We therefore used the BUSCO program to evaluate the completeness of the assemblies from its gene content [28]. BUSCO showed that these assemblies had more than 80% (1,320 complete single-copy orthologs of 2,675 total BUSCO groups searched in R. montenegrensis and 1,281 of 2,675 in R. robustus) of complete Arthropods single copy orthologs, which is consistent with what was expected for transcriptomes (S1 Fig).

Table 1. Summary of sequencing and assembly statistics based on cephalic tissue from males of R. montenegrensis (Rm) and R. robustus (Rr).

| Rm | Rr | |

|---|---|---|

| Total reads | 32,502,355 | 33,123,076 |

| Reads filtered by quality | 30,772,029 | 31,528,614 |

| Reads after normalization x 2 reads | 6,543,879 | 7,296,681 |

| Total trinity unigenes | 53,042 | 56,756 |

| Total trinity transcripts | 64,952 | 70,894 |

| Percent GC | 34.66 | 34.68 |

| N50 | 2,083 | 2,134 |

| N50 unigenes | 1,572 | 1,585 |

| Contigs larger than 1000 bp | 19,838 | 21,652 |

| Contigs larger than 2000 bp | 9,903 | 10,918 |

| Mean (bp) | 477 | 480 |

| Median (bp) | 1,046 | 1,057 |

| Total assembled bases | 67,920,294 | 74,955,989 |

| Largest contig (bp) | 32,076 | 30,264 |

Coding Sequence (CDS) prediction and functional annotation

TransDecoder identified 27,150 CDSs in the R. montenegrensis assembly and 28,965 in the R. robustus assembly. Out of those, 17,207 and 18,806 complete coding regions of R. montenegrensis and R. robustus were predicted, respectively.

A similarity search with BLASTx, identified 16,057 coding regions in R. montenegrensis and 16,781 coding regions in R. robustus with a significant hit against the NR database. Out of these hits, 12% had the best hit associated to Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera) sequences for both species (S2 Fig). Of the total sequences with significant hits against the NR, 10,442 R. montenegrensis sequences and 10,828 R. robustus sequences had functional annotation associated with Gene Ontology terms. In addition, 2,412 coding regions of R. montenegrensis and 2,447 coding regions of R. robustus were found to be related to enzyme codes in the KEGG database. The annotation against the genome of R. prolixus revealed that 22,871 CDSs of head transcriptomes of R. montenegrensis and 24,246 of R. robustus had significant hits with CDSs predicted from this genome.

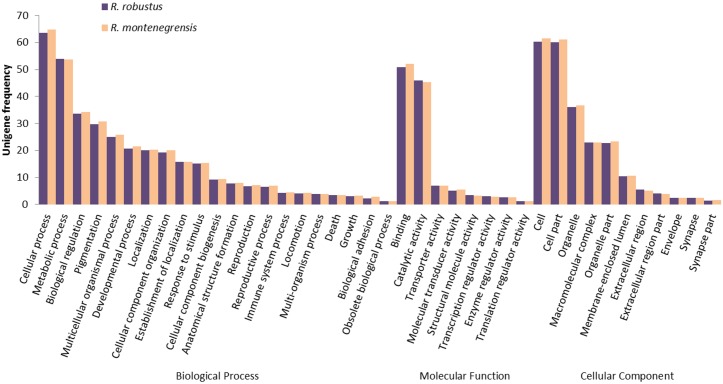

Using the WEGO software, the annotated coding regions were distributed into 55 different level-2 GO categories, related to three main classes: Biological Processes (18), Molecular Function (24), and Cellular Component (13). Cellular Process was the most represented category in Biological Process, being associated with 64.9% of the coding regions of R. montenegrensis and 63.5% of the coding regions of R. robustus. Most of the annotated transcripts were found to be associated with the Binding category in Molecular Function, with 52% of the transcripts in R. montenegrensis and 50.9% in R. robustus, whereas the Cell Part category was associated with 61.5% of the transcripts in R. montenegrensis and 61.2% in R. robustus, being the most represented in the Cellular Component class (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Gene Ontology level 2 terms with frequencies greater than 1% found for coding regions of unigenes derived from the head transcriptomes of males of R. montenegrensis and R. robustus.

An enrichment analysis in GO terms revealed eight terms that were significantly enriched in the transcriptome which were found to be associated with the clathrin-coated endocytic vesicle membrane (Table 2). Proteins associated with this GO term have also been found in Drosophila [40] and in the transcriptome of the digestive tract of R. prolixus [41]. It is a multimeric coat protein with intracellular sorting roles and influences on mitosis, which is linked to a variety of functions in human health such as infection disease and metabolism [42].

Table 2. Enrichment analysis of the GO terms of the most divergent unigenes ( = 1).

P-values were corrected using the method proposed by Benjamini and Hochberg [32].

| GO Term | Category Name | Main Category | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0030128 | clathrin coat of endocytic vesicle | Cellular Component | 0.01278887 |

| GO:0030122 | AP2 adaptor complex | Cellular Component | 0.01278887 |

| GO:0045334 | clathrin-coated endocytic vesicle | Cellular Component | 0.02489061 |

| GO:0030669 | clathrin-coated endocytic vesicle membrane | Cellular Component | 0.02489061 |

| GO:0030132 | clathrin coat of coated pit | Cellular Component | 0.02489061 |

| GO:0030666 | endocytic vesicle membrane | Cellular Component | 0.0423901 |

| GO:0030125 | clathrin vesicle coat | Cellular Component | 0.0423901 |

| GO:0005905 | coated pit | Cellular Component | 0.0423901 |

Test of selection

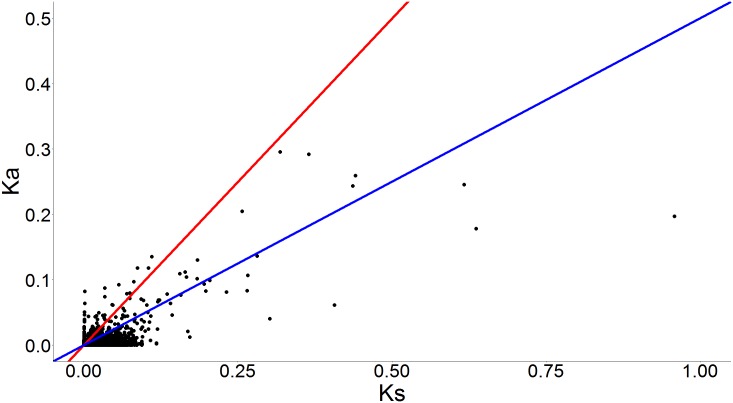

Out of the 6,951 pairs of ortholog CDSs, we identified 549 pairs with a Ka/Ks > 1 (Fig 2), which suggests that they have potentially evolved under positive selection. Several of these genes with signs of positive selection are related to proteins involved in host haemostatic defences, which comprise antihaemostatic, haemolytic, vasodilator and anticoagulant properties [43–45] (Table 3). Thus, they are most likely to be involved in rapid adaptation to host responses and may be potentially relevant in the search for genes that separate different Rhodnius species. We chose to highlight some relevant protein classes, even though they were not significantly enriched in the tests performed, because the majority of genes potentially under positive selection lack association with Gene Ontology terms, limiting any enrichment tests.

Fig 2. Scatter plot of non-synonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) rates among ortholog CDSs expressed in head transcriptomes of males of R. montenegrensis and R. robustus.

Ka/Ks = 1 and and Ka/Ks = 0.5 are shown in red and blue lines, respectively.

Table 3. Summary of functional annotation and inferred evolutionary rates (Ka, Ks and Ka/Ks) of unigenes in head transcriptomes of R. montenegrensis and R. robustus.

| Annotation | Function | Ka | Ks | Ka/Ks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salivary kazal-type proteinase inhibitor | Anticoagulant, vasodilator and anti-microbial activities [60]. | 0.00539 | 1.08 x 10−4 | 50 |

| Salivary lipocalin | Transportation of hydrophobic compounds in aqueous biological fluids, and as a binding protein sex pheromone [57]. | 0.07865 | 6.9827 x 10−2 | 1.12635 |

| Odorant-binding protein rproobp4 precursor | Precursor odor binding protein and / or pheromones [59]. | 0.002812 | 5.62 x 10−5 | 50 |

| Hemolysin-like secreted salivary protein 2 | Poration toxin and is often described in the microorganism [53]. | 0.011252 | 2.25 x 10−4 | 50 |

| Heme-binding protein | Prevents heme-induced oxidative damage to lipophorin [56]. | 0.028048 | 5.61 x 10−4 | 50 |

| Diptericin | Antibacterial peptide [61]. | 0.046749 | 9.35 x 10−4 | 50 |

| Nitrophorin 3b | Antihaemostatic [58]. | 0.117836 | 1.12417 | 0.719394 |

Ka: non-synonymous; Ks: synonymous; Ka/Ks. ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous rates.

A class of proteins well represented in the list of rapidly evolving genes are: proteinases and Kazal-type inhibitor of proteinases which have been found to evolve rapidly in some species [46] and are common in salivary transcriptomes of various insects, including Aedes aegypti, R. prolixus, T. infestans, T. matogrosensis e P. megistus [41, 47–50]. Proteinase inhibitors have a role in controlling host proteinases in plant feeding insects [51], as well as anticoagulant, vasodilator and anti-microbial activities in salivary glands of bloodsucking insects [48, 49]. Proteinases in general, on the other hand, had an important role into the transformation of Triatominae from sap eating bugs to blood sucking insects, which is rich in proteins [52].

There are other proteins with high evolutionary rates in the head transcriptome of Rhodnius which have been associated with processing and digesting of blood proteins, such as heme oxigenase, heme binding proteins and Hemolysin-like secreted salivary protein, which is described in microorganisms as a pore-forming toxin [53]. Though the function of this latter protein in triatomine is not well known, some authors believe it may be involved in the lysis of red blood cells [54], having been also found in P. megistus, T. matogrosensis e R. prolixus [49, 50]. Heme-binding proteins on the other hand can bind to nitric oxide to prevent platelet aggregation and vasodilation promoting vertebrate host [55]. These proteins inhibit the peroxidation of heme-dependent primary lipoprotein hemolymph in R. prolixus and that prevents oxidative damage induced by heme throughout the blood suction period [56].

We also identified salivary lipocalins which belong to a family of prokaryote and eukaryote proteins characterized by having a highly conserved structure that allows their proteins to carry hydrophobic compounds, such as lipids, in aqueous biological fluids. Several antihemostatic proteins common to triatomine were found to belong to this family, such as nitric oxide lipocalins found In R. prolixus, which has been connected with the vasodilator and platelet aggregation inhibitory function in vertebrate hosts [49]. Because of their hydrophobic affinity, some lipocalins were also described as binding protein sex pheromone [57]. Other lipocalins, such as Nitrophorin 3b, has also commonly been found in the hematophagous arthropods and their transcriptomes, such as in T. rubida, P. megistus, and R. prolixus [41, 49, 50, 58]. This protein is a type of lipocalin that binds nitric oxide and has antihemostatic action.

Another set of relevant proteins we identified are related to chemosensory perception. We have identified several Odorant Binding Proteins, as well as Chemosensory Binding Proteins, which have been associated to odor identification such as host or pheromone sensing, such as the precursor of Odorant-binding protein (OBP) RproOBP4 [59]. We should point out that the transcriptomes here produced contain not only antennal tissues, but also salivary tissues, so it is possible that these OBPs may have a different role as well, since in the gut of R. prolixus some OBPs are related to the transport of nutrients or other molecules involved in coordinating the intestinal physiological function [41].

SNP calling

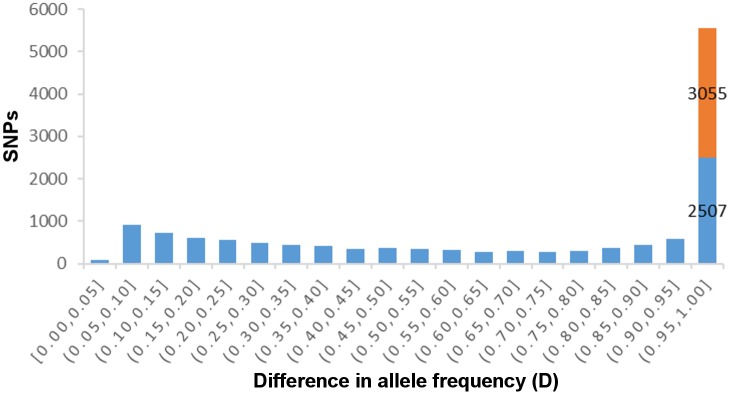

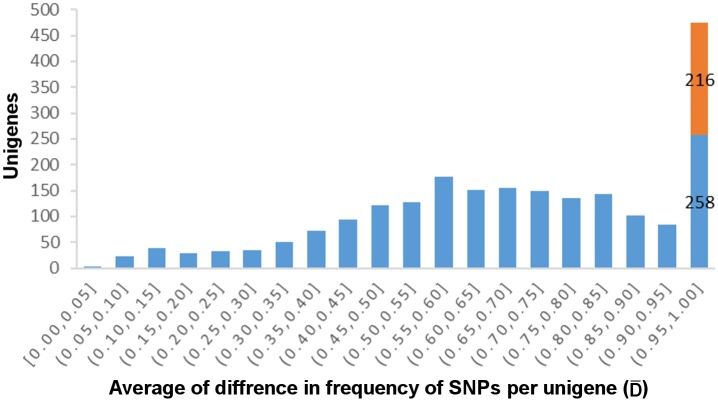

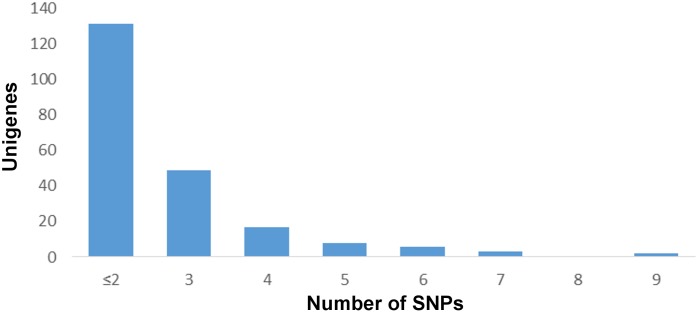

A comparison of the assemblies of both species identified 13,695 SNPs in 2,196 different contigs. Out of these SNPs, 8,350 are fixed in R. montenegrensis and 7,888 in R. robustus. Using the frequency of each SNP, a distribution of the differentiation index (D) reveals that the SNPs are in general homogeneously distributed across almost all D classes, with the exception of the most differentiated class. This class alone harbors 5,552 SNPs, i.e, over 40% of the total number of SNPs found in the analysis of R. montenegrensis and R. robustus. That indicates a great number of SNPs that were fixed, or nearly fixed, for different nucleotides between the species. Furthermore, 3,055 of these had a D of 100%; in other words, the different species were fixed for different nucleotides (Fig 3). Considering the average index () by contig, which averages the D values of all of the SNPs in each contig, 558 contigs, out of a total of 2,196, had a value above 90%, and 216 showed a of 100% (Fig 4), 85 of them with three or more SNPs (Fig 5), again indicating that all SNPs in these contigs are fixed for different nucleotides between the species studied (Figs 4 and 5).

Fig 3. Distribution of absolute allele frequency differences (D) of the 13,696 shared SNPs between R. montenegrensis and R. robustus.

We highlight in red the class of SNPs with D = 1.

Fig 4. Absolute allele frequency difference averages of shared SNPs of R. montenegrensis and R. robustus per transcript ().

We highlight in red the class of SNPs with = 1.

Fig 5. Distribution of number of SNPs per contig that are 100% fixed for different alleles between R.montenegrensis and R. robustus.

Speciation and fixed SNPs

There are morphological and genetic differences among the two species here studied which led to their recognition as separate species [62]; nevertheless, these differences were previously considered not to warrant them separation at the species level by Abad-Fanch [18]. The few morphological differences identified may be a consequence of recent divergence, however, the current SNP analysis shows that 5,562 (40.6%) of the SNPs identified were fixed between the species (Fig 2). It has been suggested that only a few genes in general are involved in the beginning of the speciation process. As time goes by, drift and linkage disequilibrium increase the number of genes with fixed differences, which may extend to whole chromosomes and even the whole genome [63, 64]. Thus, recently diverged species would show only a few fixed SNPs and, with new barriers to reproduction, more differences would be fixed in these genomes. We would expect that if R. montenegrensis and R. robustus belonged to the same species, we would see a distribution of D close to normal, but with values closer to zero, since they would share many polymorphisms. However, the results show that more than 30% of the SNPs were fixed for different nucleotides in these two species, a finding which reflects more than 7,000 SNPs with an average of D > 95% (Fig 3). The fact that there are multiple SNPs fixed in the same contig is particularly interesting, since it might reflect the occurrence of strong selection favoring the fixation of variants in different species, or simply a consequence of the long time that has passed since these populations diverge. This substantial number of fixed polymorphisms suggests a clear separation of lineages and reinforces the validity of R. montenegrensis, contrary to what was suggested by Abad- Franch et al. [4, 18] that the latter species would be a variety of R. robustus. Furthermore, these data provide a long list of potential markers that may be used to differentiate R. montenegrensis from R. robustus that need to be corroborated in more populations across the species’ distribution.

Candidate markers for identifying species of Rhodnius

Some species in the genus Rhodnius are difficult to identify using morphological characters [65, 66], especially when the samples are not analyzed by expert taxonomists [66, 67]. To solve this problem, some authors have suggested the use of molecular markers, such as sequences from the mitochondrial gene cytochrome b, which was claimed to be effective at separating several species in the genus [16, 68, 69]. However, even though this marker differentiated R. montenegrensis and R.robustus [17], the genetic distance between these two species was considered to be too low to warrant them separate species status [18]. Several authors have already questioned the efficacy of a “one gene solves all taxonomic problems” [70, 71], so, even though mitochondrial genes have had tremendous success to help with taxonomic hurdles in some taxa, even Hymenoptera [72, 73], its efficacy is not universal [71, 74, 75], particularly when you have recent divergence of large populations sizes with continuous gene flow. In that case, we may need to retort to several nuclear genes, particularly those with faster evolutionary rate that may have a better chance of tracking the species differences. Considering the method used to produce these assemblies, we found a number of contigs with high level of differentiation between R. montenegrensis and R. robustus, among which, 11 that were fixed between these species and potentially evolved under positive selection (Ka/Ks > 1). Interestingly, in these contigs we found genes coding for proteins involved in cell metabolism as well as other related to host interaction response (Table 4), which makes them potentially useful for identifying R. montenegrensis from R. robustus and perhaps might prove to be useful for speciation studies [76] of other species in the genus, as well.

Table 4. Unigenes highly differentiated and potentially evolved under positive selection (Ka/Ks > 1) in head transcriptomes of R. montenegrensis and R. robustus.

| Contig RR | Annotation | Function | SNP | Ka | Ks | Ka/Ks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c10228_g1_i1 | PREDICTED: zinc finger CCHC-type and RNA-binding motif-containing protein 1-like | Binds to RNA, being involved in many stages of its metabolism [77] | 4 | 1 | 3.94 x 10−3 | 7.90 x 10−5 | 50 |

| c10808_g1_i1 | 6 | 1 | 1.86 x 10−2 | 3.7 x 10−4 | 50 | ||

| c11678_g1_fi1 | phosphopentothenoylcysteine decarboxylase | Acts in biosynthesis of coenzyme A [78, 79]. | 4 | 1 | 6.33 x 10−3 | 1.3 x 10−4 | 50 |

| c13526_g1_i2 | 4 | 1 | 8.62 x 10−3 | 5.28 x 10−3 | 1.63269 | ||

| c13603_g1_i1 | nucleolar phosphoprotein-like | Ribosomal protein encoding and transport, control of centrosome duplication [80]. | 6 | 0.9993 | 1.59 x 10−2 | 1.09 x 10−2 | 1.45733 |

| c41453_g1_i1 | PREDICTED: uncharacterized protein LOC101741012 isoform X1 | 2 | 0.9969 | 8.44 x 10−3 | 1.7 x 10−4 | 50 | |

| c13063_g1_i1 | hypothetical protein TcasGA2_TC012103 | 7 | 0.9959 | 3.63 x 10−3 | 7.30 x 10−5 | 50 | |

| c10204_g1_i1 | PREDICTED: heme oxygenase 1-like | Catalyzes the degradation of heme. Important for digestion of the blood meal [49, 50]. | 10 | 0.9949 | 6.67 x 10−3 | 1.3 x 10−4 | 50 |

RR: Rhodnius robustus; SNP: Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms;

: Average of SNP allele frequency differences between species per contig; Ka: rate of non-synonymous substitutions; Ks: rate of synonymous substitutions; Ka/Ks. ratio of non-synonymous and synonymous rates.

Conclusion

The study on head tissues transcriptomes from R. montenegrensis and R. robustus generated thousands of interesting genes that shed some light in the evolution and divergence of these species, as well as helped establish potential targets for Triatominae in general, as these data can be combined with previous transcriptomes available for species in this subfamily. The contig analysis generated thousands of polymorphic SNPs, a great number of them fixed for different nucleotides in R. robustus and R. montenegrensis, which suggests that these two species have a greater level of divergence than previously considered and might corroborate morphological and morphometric studies that differentiate them. Moreover, these results provide a plethora of genes potentially evolving under positive selection that might be relevant in the quest of finding markers that could not only distinguish R. montenegrensis and R robustus but perhaps be very useful for studies among other species in the genus and even across genera in Triatominae.

Supporting information

80% (1,320 complete single-copy orthologs of 2,675 total BUSCO groups searched in R. montenegrensis and 1,281 of 2,675 in R. robustus) of complete arthropods single copy orthologues, 8% fragmented and 12% missing of complete arthropods single copy orthologues in both species.

(TIF)

BLASTx, identified 16,057 coding regions in R. montenegrensis and 16,781 coding regions in R. robustus with a significant hit against the NR database.

(TIF)

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the School of Pharmaceutical Sciences and the Graduate Program in Biosciences and Biotechnology Applied to Pharmacy of the São Paulo State University (Unesp), Araraquara Campus. The authors would also like to thank the Basic Parasitology Laboratory from the same institution. In addition, the authors are grateful to the Laboratory for Functional Genomics Applied to Agriculture and Bioenergy of the Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture (ESALQ) at the University of São Paulo (USP), Brazil.

Data Availability

All files are available from the SRA of Genbank database (accession number SRP08082).

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) (www.capes.gov.br), research project AUXPE N. 23038.005285/2011-12 (JAR) supplying scholarships to DBC and HP; by CAPES\Programa de Excelência Acadêmica (Proex) (http://www.capes.gov.br/bolsas/bolsas-nopais/proex) awarded to Programa de Pós Graduação em Biociências e Biotecnologia Aplicadas a Farmácia da Faculdade de Ciências Farmacêuticas, UNESP Araraquara; by Programa de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Científico da Faculdade de Ciências Farmacêuticas - UNESP Araraquara (PADC); by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (http://cnpq.br/), research grants 150626/2012-6 (SC-E) and 160002/2013-3 (CC). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.WHO. World Health Organization Geneva: WHO; 2015 [cited 2015 16/12/2015]. Fact sheet N°340, Updated March 2015:[World Health Organization].

- 2.Lent H, Wygodzinsky P. Revision of the Triatominae (Hemiptera, Reduviidae), and their significance as vectors of Chagas disease. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 1979;163 n 3:397. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jurberg J, Rocha DS, Galvão C. Rhodnius zeledoni sp. nov. afim de Rhodnius paraensis Sherlock, Guitton & Miles, (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae). Biota Neotropical. 2009;9(1):5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abad-Franch F, Lima MM, Sarquis O, Gurgel-Gonçalves R, Sánchez-Martín M, Calzada J, et al. On palms, bugs, and Chagas disease in the Americas. Acta Trop. 2015;151:126–41. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galvão C. Vetores da Doença de Chagas no Brasil de CSB, Zoologia, editors. Scielo books 2014. 289 p. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Souza ES, Barbosa NC, Furtado MB, Oliveira Jd, Nascimento JD, Vendrami DP, Gardim S, et al. Description of Rhodnius marabaensis sp. n. (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae) from Pará State, Brazil. ZooKeys 2016;621:45–62. Epub 03 Oct 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galvão C, Carcavallo R, Rocha DS, Jurberg J. A. Checklist of the current valid species of the subfamily Triatominae Jeannel, (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) and their geographical distribution, with nomenclatural and taxonomic notes. Zootaxa. 2003;202:36. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aguilar HM, Abad-Franch F, Dias JC, Junqueira AC, Coura JR. Chagas disease in the Amazon region. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102 Suppl 1:47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coura JR, Viñas PA, Junqueira AC. Ecoepidemiology, short history and control of Chagas disease in the endemic countries and the new challenge for non-endemic countries. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2014;0:0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abad-Franch F, Monteiro FA, Jaramillo ON, Gurgel-Gonçalves R, Dias FB, Diotaiuti L. Ecology, evolution, and the long-term surveillance of vector-borne Chagas disease: a multi-scale appraisal of the tribe Rhodniini (Triatominae). Acta Trop. 2009;110(2–3):159–77. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matias A, de la Riva J, Martinez E, Torrez M, Dujardin JP. Domiciliation process of Rhodnius stali (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in Alto Beni, La Paz, Bolivia. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8(3):264–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galvão C, Justi SA. An overview on the ecology of Triatominae (Hemiptera:Reduviidae). Acta Trop. 2015;151:116–25. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodrigues VL, Pauliquevis C Junior, da Silva RA, Wanderley DM, Guirardo MM, Rodas LA, et al. Colonization of palm trees by Rhodnius neglectus and household and invasion in an urban area, Araçatuba, São Paulo State, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2014;56(3):213–8. 10.1590/S0036-46652014000300006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carvalho DB, Almeida CE, Rocha CS, Gardim S, Mendonça VJ, Ribeiro AR, et al. A novel association between Rhodnius neglectus and the Livistona australis palm tree in an urban center foreshadowing the risk of Chagas disease transmission by vectorial invasions in Monte Alto City, São Paulo, Brazil. Acta Trop. 2013;130C:35–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurgel-Gonçalves R, Abad-Franch F, Ferreira JB, Santana DB, Cuba CA. Is Rhodnius prolixus (Triatominae) invading houses in central Brazil? Acta Trop. 2008;107(2):90–8. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monteiro FA, Barrett TV, Fitzpatrick S, Cordon-Rosales C, Feliciangeli D, Beard CB. Molecular phylogeography of the Amazonian Chagas disease vectors Rhodnius prolixus and R. robustus. Mol Ecol. 2003;12(4):997–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosa JA, Rocha CS, Gardim S, Pinto MC, Mendonça VJ, Ferreira FILHO JCR, et al. Description of Rhodnius montenegrensis n. sp. (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae) from the state of Rondônia, Brazil. ZOOTAXA. 2012;3478(1175–5334):62–76. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abad-Franch F, Pavan MG, Jaramillo-O N, Palomeque FS, Dale C, Chaverra D, et al. Rhodnius barretti, a new species of Triatominae (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) from western Amazonia. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2013;108 Suppl 1:92–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lent H, Jurberg J, Galvão C. Rhodnius stali n. sp., afim de Rhodnius pictipers Stal, 1872 (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae). Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 1993;88 n°4(.):10. Epub 614. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson JJ. DNA barcodes for insects. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;858:17–46. 10.1007/978-1-61779-591-6_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emerson KJ, Merz CR, Catchen JM, Hohenlohe PA, Cresko WA, Bradshaw WE, et al. Resolving postglacial phylogeography using high-throughput sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(37):16196–200. 10.1073/pnas.1006538107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riesgo A, Andrade SC, Sharma PP, Novo M, Pérez-Porro AR, Vahtera V, et al. Comparative description of ten transcriptomes of newly sequenced invertebrates and efficiency estimation of genomic sampling in non-model taxa. Front Zool. 2012;9(1):33 10.1186/1742-9994-9-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metzker ML. Sequencing technologies—the next generation. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(1):31–46. 10.1038/nrg2626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berdan EL, Mazzoni CJ, Waurick I, Roehr JT, Mayer F. A population genomic scan in Chorthippus grasshoppers unveils previously unknown phenotypic divergence. Mol Ecol. 2015;24(15):3918–30. 10.1111/mec.13276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chomczynski P, Mackey K. Short technical reports. Modification of the TRI reagent procedure for isolation of RNA from polysaccharide- and proteoglycan-rich sources. Biotechniques. 1995;19(6):942–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cathala G, Savouret JF, Mendez B, West BL, Karin M, Martial JA, et al. A method for isolation of intact, translationally active ribonucleic acid. DNA. 1983;2(4):329–35. 10.1089/dna.1983.2.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(7):644–52. 10.1038/nbt.1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(19):3210–2. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mesquita RD, Vionette-Amaral RJ, Lowenberger C, Rivera-Pomar R, Monteiro FA, Minx P, et al. Genome of Rhodnius prolixus, an insect vector of Chagas disease, reveals unique adaptations to hematophagy and parasite infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(48):14936–41. 10.1073/pnas.1506226112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conesa A, Götz S, García-Gómez JM, Terol J, Talón M, Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(18):3674–6. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alexa A, Rahnenführer J, Lengauer T. Improved scoring of functional groups from gene expression data by decorrelating GO graph structure. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(13):1600–7. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological). 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–9. 10.1038/nmeth.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, Shen D, McLellan MD, Lin L, et al. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012;22(3):568–76. 10.1101/gr.129684.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrés JA, Larson EL, Bogdanowicz SM, Harrison RG. Patterns of transcriptome divergence in the male accessory gland of two closely related species of field crickets. Genetics. 2013;193(2):501–13. 10.1534/genetics.112.142299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anisimova M, Kosiol C. Investigating protein-coding sequence evolution with probabilistic codon substitution models. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26(2):255–71. 10.1093/molbev/msn232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792–7. 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abascal F, Zardoya R, Telford MJ. TranslatorX: multiple alignment of nucleotide sequences guided by amino acid translations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Web Server issue):W7–13. 10.1093/nar/gkq291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Z, Li J, Zhao XQ, Wang J, Wong GK, Yu J. KaKs_Calculator: calculating Ka and Ks through model selection and model averaging. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2006;4(4):259–63. 10.1016/S1672-0229(07)60007-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang HC, Newmyer SL, Hull MJ, Ebersold M, Schmid SL, Mellman I. Hsc70 is required for endocytosis and clathrin function in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 2002;159(3):477–87. 10.1083/jcb.200205086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ribeiro JM, Genta FA, Sorgine MH, Logullo R, Mesquita RD, Paiva-Silva GO, et al. An insight into the transcriptome of the digestive tract of the bloodsucking bug, Rhodnius prolixus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(1):e2594 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brodsky FM. Diversity of clathrin function: new tricks for an old protein. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2012;28:309–36. Epub 2012/07/23. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fontaine A, Diouf I, Bakkali N, Missé D, Pagès F, Fusai T, et al. Implication of haematophagous arthropod salivary proteins in host-vector interactions. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:187 10.1186/1756-3305-4-187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santiago PB, Assumpção TC, Araújo CN, Bastos IM, Neves D, Silva IG, et al. A Deep Insight into the Sialome of Rhodnius neglectus, a Vector of Chagas Disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(4):e0004581 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwarz A, Medrano-Mercado N, Schaub GA, Struchiner CJ, Bargues MD, Levy MZ, et al. An updated insight into the Sialotranscriptome of Triatoma infestans: developmental stage and geographic variations. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(12):e3372 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Graur D, Li WH. Evolution of protein inhibitors of serine proteinases: positive Darwinian selection or compositional effects? J Mol Evol. 1988;28(1–2):131–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rimphanitchayakit V, Tassanakajon A. Structure and function of invertebrate Kazal-type serine proteinase inhibitors. Dev Comp Immunol. 2010;34(4):377–86. 10.1016/j.dci.2009.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watanabe RM, Soares TS, Morais-Zani K, Tanaka-Azevedo AM, Maciel C, Capurro ML, et al. A novel trypsin Kazal-type inhibitor from Aedes aegypti with thrombin coagulant inhibitory activity. Biochimie. 2010;92(8):933–9. 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ribeiro JM, Assumpção TC, Pham VM, Francischetti IM, Reisenman CE. An insight into the sialotranscriptome of Triatoma rubida (Hemiptera: Heteroptera). J Med Entomol. 2012;49(3):563–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ribeiro JM, Schwarz A, Francischetti IM. A Deep Insight Into the Sialotranscriptome of the Chagas Disease Vector, Panstrongylus megistus (Hemiptera: Heteroptera). J Med Entomol. 2015;52(3):351–8. 10.1093/jme/tjv023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Christeller JT. Evolutionary mechanisms acting on proteinase inhibitor variability. FEBS J. 2005;272(22):5710–22. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04975.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Terra WR. Physiology and biochemistry of insect digestion: an evolutionary perspective. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1988;21(4):675–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gouaux E. alpha-Hemolysin from Staphylococcus aureus: an archetype of beta-barrel, channel-forming toxins. J Struct Biol. 1998;121(2):110–22. 10.1006/jsbi.1998.3959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Assumpção TC, Francischetti IM, Andersen JF, Schwarz A, Santana JM, Ribeiro JM. An insight into the sialome of the blood-sucking bug Triatoma infestans, a vector of Chagas' disease. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;38(2):213–32. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Champagne DE, Nussenzveig RH, Ribeiro JM. Purification, partial characterization, and cloning of nitric oxide-carrying heme proteins (nitrophorins) from salivary glands of the blood-sucking insect Rhodnius prolixus. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(15):8691–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dansa-Petretski M, Ribeiro JM, Atella GC, Masuda H, Oliveira PL. Antioxidant role of Rhodnius prolixus heme-binding protein. Protection against heme-induced lipid peroxidation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(18):10893–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seo H, Kim M, Choi Y, Ka H. Salivary lipocalin is uniquely expressed in the uterine endometrial glands at the time of conceptus implantation and induced by interleukin 1beta in pigs. Biol Reprod. 2011;84(2):279–87. 10.1095/biolreprod.110.086934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Montfort WR, Weichsel A, Andersen JF. Nitrophorins and related antihemostatic lipocalins from Rhodnius prolixus and other blood-sucking arthropods. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1482(1–2):110–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vogt RG, Prestwich GD, Lerner MR. Odorant-binding-protein subfamilies associate with distinct classes of olfactory receptor neurons in insects. J Neurobiol. 1991;22(1):74–84. 10.1002/neu.480220108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Watanabe RM, Tanaka-Azevedo AM, Araujo MS, Juliano MA, Tanaka AS. Characterization of thrombin inhibitory mechanism of rAaTI, a Kazal-type inhibitor from Aedes aegypti with anticoagulant activity. Biochimie. 2011;93(3):618–23. 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee JH, Cho KS, Lee J, Yoo J, Chung J. Diptericin-like protein: an immune response gene regulated by the anti-bacterial gene induction pathway in Drosophila. Gene. 2001;271(2):233–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosa JA, Justino HH, Barata JM. Differences in the size of eggshells among three Pangstrongylus megistus colonies. Rev Saude Publica. 2003;37(4):528–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu C-I. The genic view of the process of speciation. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2001;14(6):851–65. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seehausen O, Butlin RK, Keller I, Wagner CE, Boughman JW, Hohenlohe PA, et al. Genomics and the origin of species. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15(3):176–92. 10.1038/nrg3644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Neiva A, Pinto C. Dos hemípteros hematophagos do Norte do Brasil com descrição de duas novas espécies. Brasil Médicina 1923. p. 73 6.

- 66.Dujardin JP, Garcia-Zapata MT, Jurberg J, Roelants P, Cardozo L, Panzera F, et al. Which species of Rhodnius is invading houses in Brazil? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991;85(5):679–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Almeida CE, Faucher L, Lavina M, Costa J, Harry M. Molecular Individual-Based Approach on Triatoma brasiliensis: Inferences on Triatomine Foci, Trypanosoma cruzi Natural Infection Prevalence, Parasite Diversity and Feeding Sources. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(2):e0004447 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lyman DF, Monteiro FA, Escalante AA, Cordon-Rosales C, Wesson DM, Dujardin JP, et al. Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation among triatomine vectors of Chagas' disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60(3):377–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Monteiro FA, Wesson DM, Dotson EM, Schofield CJ, Beard CB. Phylogeny and molecular taxonomy of the Rhodniini derived from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62(4):460–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nosil P, Feder JL. Genomic divergence during speciation: causes and consequences. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367(1587):332–42. 10.1098/rstb.2011.0263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moritz C, Cicero C. DNA barcoding: promise and pitfalls. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(10):e354 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tavares ES, Baker AJ. Single mitochondrial gene barcodes reliably identify sister-species in diverse clades of birds. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:81 10.1186/1471-2148-8-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Virgilio M, Backeljau T, Nevado B, De Meyer M. Comparative performances of DNA barcoding across insect orders. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:206 10.1186/1471-2105-11-206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brower AVZ. Problems with DNA barcodes for species delimitation:‘ten species’ of Astraptes fulgerator reassessed (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae). Systematics and Biodiversity. 2006;4(2):127–32 1477–2000. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Justi SA, Russo CA, Mallet JR, Obara MT, Galvão C. Molecular phylogeny of Triatomini (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae). Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:149 10.1186/1756-3305-7-149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fu B, He S. Transcriptome analysis of silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) by paired-end RNA sequencing. DNA Res. 2012;19(2):131–42. 10.1093/dnares/dsr046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hurt JA, Obar RA, Zhai B, Farny NG, Gygi SP, Silver PA. A conserved CCCH-type zinc finger protein regulates mRNA nuclear adenylation and export. J Cell Biol. 2009;185(2):265–77. 10.1083/jcb.200811072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kupke T. Molecular characterization of the 4'-phosphopantothenoylcysteine decarboxylase domain of bacterial Dfp flavoproteins. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(29):27597–604. 10.1074/jbc.M103342200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Strauss E, Zhai H, Brand LA, McLafferty FW, Begley TP. Mechanistic studies on phosphopantothenoylcysteine decarboxylase: trapping of an enethiolate intermediate with a mechanism-based inactivating agent. Biochemistry. 2004;43(49):15520–33. 10.1021/bi048340a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Briggs MW, Burkard KT, Butler JS. Rrp6p, the yeast homologue of the human PM-Scl 100-kDa autoantigen, is essential for efficient 5.8 S rRNA 3' end formation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(21):13255–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

80% (1,320 complete single-copy orthologs of 2,675 total BUSCO groups searched in R. montenegrensis and 1,281 of 2,675 in R. robustus) of complete arthropods single copy orthologues, 8% fragmented and 12% missing of complete arthropods single copy orthologues in both species.

(TIF)

BLASTx, identified 16,057 coding regions in R. montenegrensis and 16,781 coding regions in R. robustus with a significant hit against the NR database.

(TIF)

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All files are available from the SRA of Genbank database (accession number SRP08082).