Abstract

Zika virus is increasingly recognized as a fetal pathogen worldwide. We describe the first case of neonatal demise with travel-associated Zika virus infection in the United States of America, including a novel prenatal ultrasound finding. A young Latina presented to our health care system in Southeast Texas for prenatal care at 23 weeks of gestation. Fetal Dandy–Walker malformation, asymmetric cerebral ventriculomegaly, single umbilical artery, hypoechoic fetal knee, dorsal foot edema, and mild polyhydramnios were noted upon initial screening prenatal sonography at 26 weeks. A growth-restricted, microcephalic, and arthrogrypotic infant was delivered alive at 36 weeks but died within an hour despite resuscitation. The neonatal karyotype was normal. Flavivirus IgM antibodies were identified in the serum of the puerpera, once she disclosed that she had traveled from El Salvador to Texas in the early second trimester. Zika virus was identified in the umbilical cord and neonatal brain. Fetal arthritis may precede congenital arthrogryposis in cases of Zika virus infection and may be detectable by prenatal sonography. Physician and health care system vigilance is required to optimally address the significant and enduring Zika virus global health threat.

Keywords: Zika virus, prenatal ultrasound, fetal arthritis, Dandy–Walker malformation, single umbilical artery, congenital Zika virus syndrome, neonatal demise, prolonged maternal Zika virus seropositivity, perinatal universal precautions

Zika virus (ZIKV) presents an unprecedented public health challenge as the first mosquito-borne and sexually transmitted virus that has been associated with human birth defects and fetal losses.1 The first cases of this public health emergency of international concern were reported from South America in 2015, although retrospective studies have since confirmed that ZIKV was responsible for the outbreak in Micronesia in 2007 and epidemics in various Pacific islands in 2013 and 2014. Brazil has been most affected thus far with over 2,100 cases of ZIKV-attributed neonatal microcephaly, but severe birth defects linked to ZIKV infection have been reported in almost 30 countries. As of February 15, 2017, ZIKV has been linked to 5,040 reported cases of travel-associated infections, including 1,455 pregnant women, in the United States; Puerto Rico is experiencing explosive spread of this epidemic with approximately 37,000 locally acquired cases, while Florida has 214 cases of locally acquired mosquito-borne ZIKV infections in Miami, and Texas 6 cases in Brownsville.2 3 Forty-three liveborn infants with birth defects and five pregnancy losses with birth defects have been documented in the United States thus far. Sexual transmission of ZIKV can occur from both male and female partners; the virus may be able to persist in vaginal secretions for 2 weeks after infection, and in semen for up to 6 months.

ZIKV has clinical manifestations in adults that overlap with chikungunya and dengue viruses—namely, fever, malaise, rash, arthralgia, and conjunctivitis—but is self-limited in the vast majority of adult cases, causing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to call this a silent epidemic.1 It has been associated with the rare Guillain–Barre syndrome in affected adults, but its most worrisome effects are on the human fetus when the pregnant woman is infected, particularly in the first half of gestation. Prior studies have confirmed the association between ZIKV infection during pregnancy and serious birth defects, including microcephaly. The risk of microcephaly after ZIKV infection early in pregnancy may be between 1 and 13%.4 Ongoing studies are exploring the full spectrum of the congenital ZIKV syndrome. We present the first case of neonatal demise with travel-associated ZIKV infection in the United States, including a novel fetal ultrasound finding and pathological analyses.

Case Presentation

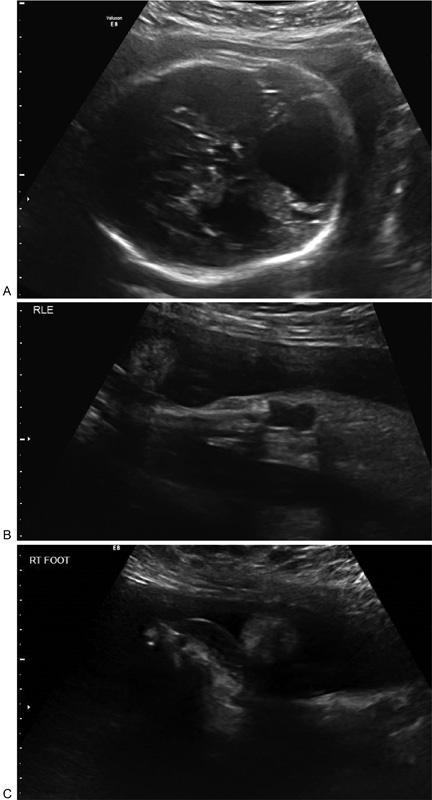

In March 2016, a young Latina primigravida presented to our health care system in Southeast Texas to initiate prenatal care at 23 weeks of gestation. The routine evaluation was only remarkable for body mass index of 35 kg/m2. She had an initial screening prenatal ultrasound examination at 26 weeks, which was remarkable for (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Prenatal ultrasound findings at 26 weeks: (A) Dandy–Walker malformation, ventriculomegaly, (B) hypoechoic right knee, and (C) dorsal right foot edema.

Fetal Dandy–Walker malformation

Asymmetrical fetal cerebral ventriculomegaly without microcephaly

Hypoechoic right fetal knee

Dorsal right fetal foot edema

Single umbilical artery

Mild polyhydramnios (amniotic fluid index: 24.3 cm)

Syndromic etiology was suspected, and genetic counseling recommended amniocentesis, referral to the Fetal Center for multidisciplinary evaluation and fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—which were all declined. Cell-free placental DNA in the maternal circulation was negative for major aneuploidies. The pregnancy continued with sporadic care (gravida missed several appointments, but desired full resuscitation of the infant at birth).

In June 2016, the parturient presented to our institution at 36 weeks with an 11-hour history of vaginal leaking of amniotic fluid and painful contractions. Nonreassuring fetal heart tones, rupture of membranes with thick meconium and frank breech presentation were noted upon emergency obstetrical evaluation, and an urgent cesarean delivery was performed. A growth-restricted, microcephalic, and arthrogrypotic female infant was delivered alive and immediately resuscitated by neonatologists. Despite advanced resuscitation, adequate ventilation could not be obtained. The Apgar score was 2/10 at 1 minute, 1/10 at 5 minutes, 1/10 at 10 minutes, 1/10 at 15 minutes, and 0/10 at 20 minutes; the neonate was pronounced dead 31 minutes after delivery.

The placenta had no gross abnormality; the umbilical cord had a single umbilical artery. The umbilical arterial blood gas had a pH of 7.25 and base deficit of 2 mmol/L. The birth weight was 1,885 g (1st percentile), the crown to heel length was 46.5 cm (50th percentile), and the fronto-occipital circumference was 28.5 cm (< 1st percentile).5 6 7

Breaking fetal imaging data from Brazil8 were combined with the prenatal sonographic and neonatal findings triggering clinical suspicion. Therefore the puerpera was approached on the first postoperative day with direct questions regarding possible ZIKV exposure. Upon revisiting her travel history, she disclosed for the first time that she had reached Texas via bus from El Salvador in January 2016, during the first half of pregnancy; her husband remained in El Salvador, and she denied physical contact with him or other sexual activity since her arrival in Texas. She denied ZIKV infection symptoms but consented to serologic screening and the infant's autopsy with appropriate genetic and virologic testing. The puerpera grieved her loss, but recovered well physically from her abdominal delivery and was discharged from the hospital on the third postoperative day. She provided written consent for the publication of this report.

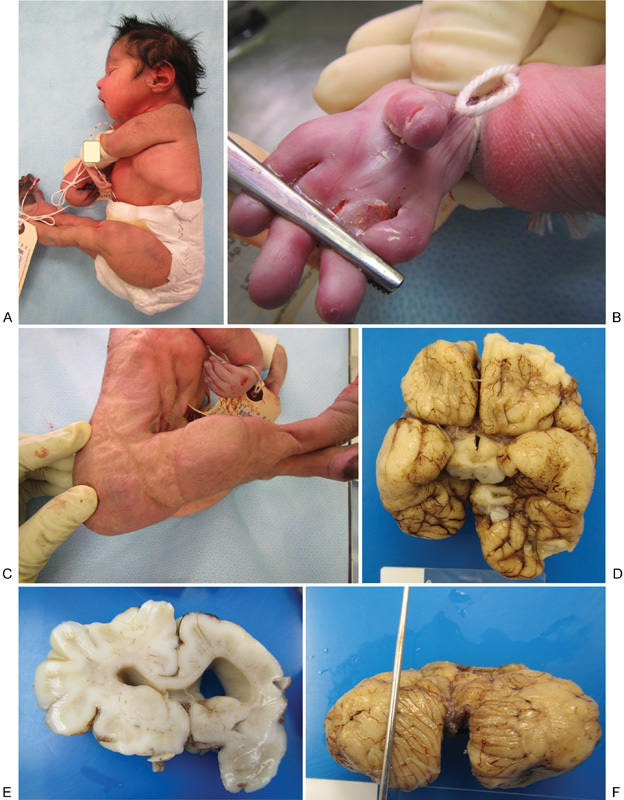

Cytogenetic analysis of cultured fibroblasts obtained from the left neonatal patellar tendon demonstrated normal female karyotype, 46XX Table 1, Fig. 2.

Table 1. Pathology findings.

| Autopsy | |

| External findings | Microcephaly, arthrogryposis |

| Misshapen/collapsed auricular tragi bilaterally (Fig. 2A) | |

| Hyperflexed wrists, extended arms; decreased musculature | |

| Shortened forearms and forelegs | |

| Fingers elongated bilaterally; shortened thumbs | |

| Bilateral hands without identifiable palmar creases (Fig. 2C) | |

| Legs extended at knees, flexed at hips; decreased musculature | |

| Bilateral foot edema (Fig. 2B) | |

| Hypertrichosis of fine downy hair on extremities and back | |

| Internal findings | Heart, outlet ventricular septal defect (5 × 5 mm) |

| Pulmonary hypoplasia; the lung-to-body weight ratio was low: 0.012 | |

| Well-formed kidneys; duplicate right renal artery | |

| Bicornuate uterus | |

| Neuropathology | Immature brain, 175 g with microcephaly |

| Asymmetry, with smaller right cerebrum, malformation of cerebral cortical development with agyria/pachygyria of bilateral temporal and right frontoparietal lobe (Fig. 2D), and subarachnoid glioneuronal heterotopia | |

| Asymmetric ventriculomegaly (Fig. 2E) | |

| Dandy–Walker malformation with large posterior fossa fourth ventricular cyst, and near-complete agenesis of the cerebellar vermis (Fig. 2F) | |

| Bilateral cerebellar cortical dysplasia, extensive, lateral parts of the hemispheres; focal cerebellar cortical heterotopia in the white matter | |

| Dystrophic calcification, multifocal: cerebral periventricular, thalamus, and midbrain | |

| Diffuse reactive astrocytosis, cerebral/cerebellar white matter | |

| Placental pathology | Placenta weight: 306 g, 16 × 16 × 3 cm |

| Membranes: Meconium-laden macrophages, minimal acute inflammation | |

| Umbilical cord: single vessel vasculitis, focal acute funisitis, moderately coiled, 22 cm long | |

| Villi: Accelerated maturation, increased karyorrhexis | |

Fig. 2.

Neonatal phenotype and pathology. (A) Lateral view of newborn demise, showing microcephaly, arthrogryposis, and collapsed auricular tragus. (B) Close-up view of the right hand showing elongated fingers, shortened thumb, and absent palmar creases. (C) The lateral view is showing arthrogryposis, decreased musculature, shortened forelegs, and redundant dorsal foot skin. (D) Basilar view of the neonatal brain at autopsy showing asymmetry, with smaller right cerebrum and disruption of cerebral cortical development with agyria/pachygyria of bilateral temporal and right frontoparietal lobes. (E) Coronal section of the neonatal brain showing asymmetric ventriculomegaly. (F) Dorsal view of the neonatal cerebellum showing Dandy–Walker malformation with near-complete agenesis of the vermis.

The Texas Department of State Health Services was alerted to the maternal travel history. Maternal blood was collected for flavivirus IgM antibody testing with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Umbilical and neonatal brain tissue specimens were also collected and formalin-fixed. Maternal serology was positive for flavivirus IgM. The CDC was contacted to process the specimens from the neonatal autopsy by real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR). The ZIKV NS-5 gene was identified by rRT-PCR in the umbilical cord, near its placental origin, and in the neonatal brain9 in August 2016. The young Latina could no longer be reached for viremic testing at that point.

Discussion

We report the first case of neonatal demise related to travel-associated ZIKV infection in United States.10 This case is remarkable for atypical fetal/neonatal neuropathology, growth restriction, late-onset microcephaly, funisitis of a two-vessel umbilical cord, and arthrogryposis with pulmonary hypoplasia—as well as the previously unseen prenatal sonographic finding of the hypoechoic fetal knee. We speculate that this case resulted from asymptomatic maternal ZIKV infection in El Salvador, during the first half of gestation (late 2015).

The timing of this woman's presentation (soon after the first reported clinical description of ZIKV embryopathy, before the implementation of systematic screening for travel history in our health care system), her decision to forego fetal MRI and amniocentesis despite counseling, her sporadic prenatal care and the atypical prenatal sonographic findings all contributed to the absence of clinical suspicion for ZIKV infection until postnatally. In fact, if it were not for the serendipitous review by one of the authors (N.Z.) of the May 2016 webinar8 wherein Dr. Pedro Piris' breaking fetal imaging data from Recife, Brazil, were presented regarding the association of ZIKV with Dandy–Walker malformation and ventriculomegaly without microcephaly, this case may well have gone undiagnosed. Two seminal articles published since this case, provide an atlas of neuroimaging findings in ZIKV embryopathy—including a single case with comparable presentation10—and a more crystallized delineation of the congenital ZIKV syndrome.11

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of hypoechoic fetal knee, thought to represent inflamed epiphyseal cartilage and/or synovium with joint effusion, in general—and in association with ZIKV embryopathy, in particular. One may speculate as to the association of this novel prenatal sonographic finding with this fetal viral pathogen—however, the unprecedented nature of both conditions makes random coincidence extremely unlikely. ZIKV shares clinical characteristics and tropisms with other flaviviruses, such as chikungunya, and is known to cause arthralgia in adults, therefore, at least transient fetal arthritis/effusion is not only biologically plausible, but also likely in the pathogenesis of ZIKV embryopathy and (along with neuromuscular pathology) may contribute to the end-result of fetal arthrogryposis—increasingly recognized as a hallmark of the congenital ZIKV syndrome. The pathogenesis of arthrogryposis associated with ZIKV embryopathy is thought to be due to a neurogenic or vascular insult. Tropism of ZIKV for fetal mesenchymal cells with an affinity for perichondrium has recently been reported12; we speculate that this viral affinity may underlie the collapsed auricular cartilage and the novel sonographic marker of hypoechoic fetal knee noted in this case.

The edema of the fetal dorsal foot (“Oedipus sign”—Greek for swollen foot) has been previously described in association with fetal Turner, Neu–Laxova, and Pena–Shokeir syndromes. Neonatal karyotype and physical examination excluded these fetal syndromes; arthrogryposis was confirmed at delivery, likely resulting in pulmonary hypoplasia in this perinatally lethal case of congenital ZIKV syndrome.

The funisitis with ZIKV-positive focus near the placental origin of the umbilical cord is noteworthy and indicates ongoing Zika viremia in the fetoplacental circulation at delivery. This is in accord with recent evidence that the fetus may act as a reservoir of ZIKV causing repetitive maternal reinfection throughout gestation13—and could explain the persistent maternal flavivirus IgM seropositivity, in this case, over 5 months after the estimated time of maternal ZIKV infection.

In summary, this first perinatally lethal case of congenital ZIKV syndrome in United States presented with atypical and novel prenatal sonographic findings, which may prove useful in tracking and diagnosing new cases of this global epidemic—and could have remained undiagnosed, if travel history and correlation with emerging data from Brazil had not been clinically combined to trigger pathological examination of the placenta and neonatal tissues. As a result of this case, our hospital has instituted a policy of storing all placentas for 72 hours, to allow for their pathological examination should any indications arise. Our perinatal staff (mostly women of reproductive age) have been alerted to this case, and urged to meticulously observe universal precautions around pregnant women under our care (most are Latinas, many with unclear ZIKV exposure status due to personal and/or partner travel history), to minimize the risk of viral transmission by body fluids. Physician and health care system vigilance are required to address this significant and enduring global health threat optimally.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to recognize the Harris County Public Health staff (Ana Zangeneh, MPH, Diana Martinez, MPH, PhD, Umair Shah, MD) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Infectious Disease Pathology Branch staff (Joy M. Gary, DVM, PhD, Gillian Hale, MD, MPH, M. Kelly Keating, DVM, Roosecellis Brasil Martines, MD, PhD, Atis Muehlenbachs, MD, PhD, Jana M. Ritter, DVM, Wun-Ju Shieh, MD, PhD, MPH, Julu Bhatnagar, PhD, Sherif Zaki, MD, PhD), who contributed to the epidemiologic and laboratory evaluation of this case.

References

- 1.Frieden T R, Schuchat A, Petersen L R. Zika virus 6 months later. JAMA. 2016;316(14):1443–1444. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection in the United States and territories (2016) Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/pregwomen-uscases.html. Accessed February 16, 2017

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus case counts in the US. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/united-states.html. Accessed February 16, 2017

- 4.Johansson M A, Mier-y-Teran-Romero L, Reefhuis J, Gilboa S M, Hills S L. Zika and the risk of microcephaly. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(01):1–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1605367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenton T R, Kim J H. A systematic review and meta-analysis to revise the Fenton growth chart for preterm infants. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.et al. Ultrasound screening for fetal microcephaly following Zika virus exposure. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(06):B2–B4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gelber S E, Grünebaum A, Chervenak F A. Prenatal screening for microcephaly: an update after three decades. J Perinat Med. 2017;45(02):167–170. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2016-0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Platt L, Malinger G.International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology (ISUOG) outreach webinar: Congenital Zika virus syndrome—how to improve your diagnostic capabilities [video webinar] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N1wsPypw6ho&feature=youtu.be. Accessed May 20, 2016

- 9.Texas Department of State Health Services. Infant death in Texas linked to Zika, news release, August 9, 2016. Available at: http://www.dshs.texas.gov/news/releases/2016/20160809.aspx. Accessed February 16, 2017

- 10.Soares de Oliveira-Szejnfeld P, Levine D, Melo A S et al. Congenital brain abnormalities and Zika virus: what the radiologist can expect to see prenatally and postnatally. Radiology. 2016;281(01):203–218. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore C A, Staples J E, Dobyns W B et al. Characterizing the pattern of anomalies in congenital Zika syndrome for pediatric clinicians. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(03):288–295. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Eijk A A, van Genderen P J, Verdijk R M et al. Miscarriage associated with Zika virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):1002–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1605898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Driggers R W, Ho C Y, Korhonen E M et al. Zika virus infection with prolonged maternal viremia and fetal brain abnormalities. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(22):2142–2151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]