Abstract

Objective

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is associated with heightened psychopathology symptoms and risky behaviors. However, extant investigations are limited by their focus on IPV victimization, despite evidence to suggest that victimization and aggression frequently co-occur. Further, research on these correlates often has not accounted for the heterogeneity of women who experience victimization.

Method

The present study utilized latent profile analysis to identify patterns of physical, psychological, and sexual victimization and aggression in a convenience sample of 212 community women experiencing victimization (M age=36.63, 70.8% African American), as well as examined differences in psychopathology symptoms (i.e., posttraumatic stress symptoms and depressive symptoms) and risky behaviors (i.e., drug problems, alcohol problems, deliberate self-harm, HIV-risk behaviors) across these classes.

Results

Four classes of women differentiated by severities of victimization and aggression were identified. Greater psychopathology symptoms were found among classes defined by greater victimization and aggression, regardless of IPV type. Risky behaviors were more prevalent among classes defined by greater sexual victimization and aggression in particular.

Conclusions

Findings highlight the importance of developing interventions that target the particular needs of subgroups of women who experience victimization.

Keywords: intimate partner, victimization, aggression, psychopathology symptoms, risky behaviors, latent profile analysis

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a highly prevalent public health concern. The World Health Organization found that, across countries, 15% to 71% of women report physical and/or sexual victimization by an intimate partner, with estimates in most countries ranging from 30% to 60% (Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2006). Among women, such victimization has been found to be a robust predictor of psychopathology, including posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) and depression (Trevillion, Oram, Feder, & Howard, 2012). Further, literature provides support for a positive relation between IPV victimization and risky behaviors, including alcohol problems (Martino, Collins, & Ellickson, 2005), drug problems (Sullivan, Cavanaugh, Buckner, & Edmondson, 2009), deliberate self-harm (DSH; Weiss, Dixon-Gordon, Duke, & Sullivan, 2015), and HIV-risk behavior (Cavanaugh, Hansen, & Sullivan, 2010). Yet, existing research is limited by its focus on victimization, despite evidence to suggest that victimization and aggression frequently co-occur (Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Selwyn, & Rohling, 2012). Moreover, few investigations have accounted for the heterogeneity of women's IPV experiences. This is a critical limitation given that IPV-victimized women are not a homogeneous group – there is variation in the severity and types of IPV they experience (i.e., physical, psychological, sexual; Johnson, 2006; Swan & Snow, 2002) that call for different assessment and intervention strategies. Thus, the goals of the present study were twofold: (1) to identify classes of women who are similar in terms of physical, psychological, and sexual victimization and aggression, and (2) to examine differences in psychopathology symptoms and risky behaviors across these classes.

IPV victimization and aggression co-occur at high rates. Using data from the National Comorbidity Survey, Williams and Frieze (2005) found that “mutual and mild violence” and “mutual and severe violence” were the most common patterns of IPV. Further, literature and meta-analytic reviews underscore the co-occurrence of victimization and aggression – women are more likely to report using aggression in their intimate relationships if they experience victimization (Langhinrichsen-Rohling et al., 2012). Evidence suggests that victimization (Smith, Thornton, DeVellis, Earp, & Coker, 2002) and aggression (Zacarias, Macassa, & Soares, 2012) types (e.g., physical, sexual, psychological) also co-occur at high rates among women. For instance, in one population-based sample, only 1.9% of IPV-victimized women reported physical victimization in the absence of sexual or psychological victimization, and only 1.1% reported sexual victimization in the absence of physical or psychological victimization (Smith et al., 2002). Yet, despite these findings, a dearth of research has examined the co-occurrence of victimization and aggression types to psychopathology and risky behaviors.

Emerging evidence points to different patterns of victimization and aggression that are related to distinct correlates. For instance, there is some theoretical and empirical support for typologies of victimization and aggression (Johnson, 2006; Swan & Snow, 2002), and past studies suggest greater psychopathology symptoms and substance use among classes defined by greater victimization (Dutton, Kaltman, Goodman, Weinfurt, & Vankos, 2005; Golder, Connell, & Sullivan, 2012). However, existing research is limited by its focus on methodological approaches that do not account for the heterogeneity of IPV among women. Indeed, we were not able to identify any investigations that examined these correlates among classes characterized by both victimization and aggression. This is a critical limitation given evidence that the precursors, correlates, and consequences of IPV vary as a function of IPV type, frequency, duration, and intensity (Coker, McKeown, & King, 2000; Coker, Smith, Bethea, King, & McKeown, 2000). Further, existing research has yet to examine the relation of IPV classes to risky behaviors prevalent among IPV-victimized women beyond substance use (e.g., HIV-risk behavior, DSH).

Therefore, it is essential that research utilize a person-centered approach to identify patterns that may exist across both victimization and aggression types, and examine whether these patterns relate to differences in psychopathology symptoms and risky behaviors. Person-centered approaches categorize individuals on the basis of patterns of characteristics that distinguish members of subgroups. Thus, these approaches can identify subtypes of women who experience victimization at greatest risk for psychopathology symptoms and risky behaviors. Understanding the heterogeneity of victimization and aggression types and their relation to psychopathology symptoms and risky behaviors could inform the development and refinement of tailored intervention efforts for this population (Bogat, Levendosky, & Von Eye, 2005).

Thus, the goal of the present study was to examine psychopathology symptoms and risky behaviors among classes characterized by different patterns of physical, psychological, and sexual victimization and aggression. Based on past research on the co-occurrence of IPV victimization and aggression (Langhinrichsen-Rohling et al., 2012) and their types (Smith et al., 2002; Zacarias et al., 2012), we expected to find at least two classes, one characterized by high levels of physical, psychological, and sexual victimization and aggression and the other characterized by low levels of these experiences. Also consistent with past research (Dutton et al., 2005; Golder et al., 2012), we expected that women in the class characterized by high (vs. low) levels of these experiences would report greater psychopathology symptoms and risky behaviors. Given the absence of research simultaneously examining physical, psychological, and sexual victimization and aggression using a person-centered approach, no other a priori hypotheses were made regarding the nature of the IPV classes or their relations to psychopathology symptoms and risky behaviors.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Data were collected as part of a larger study examining the relations among IPV, PTSS, substance use, and HIV-risk behaviors among IPV-victimized community women. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the home authors’ Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited from an urban community in the Northeast United States. Flyers advertised the opportunity to participate in the “Women’s Relationship Study” and were posted in hair and nail salons, community health centers, grocery stores, and laundromats. Women who responded to the flyers were screened for eligibility over the phone. Eligibility criteria included a) English speaking; b) aged 18 years or older; c) being in a heterosexual relationship for at least 6 months and reporting physical victimization by that partner during that time; d) face-to-face contact with partner at least twice per week; e) less than two weeks apart from partner in the last month; and f) a household income of less than or equal to $4,200 per month. The last inclusion criterion was used to control for the relation between socioeconomic status and access to/utilization of treatment and services.

The eligibility rate for those screened (n=887) was 32.9% (n=292). Women who met eligibility criteria were invited to participate in the larger study. The participation rate among those screened as eligible was 73.0% (n=212). After providing written informed consent, women completed an in-person, semi-structured, computer-assisted interview administered by trained master- or doctoral-level female research associates or postdoctoral fellows in private offices to protect participants’ safety and confidentiality. Women were subsequently debriefed, remunerated $50, and provided with a list of community resources.

The final sample was comprised of 212 women ranging in age from 18 to 58 (M=36.63, SD=10.45). In terms of racial/ethnic background, 70.8% of women self-identified as African American, 24.5% as White, 8.5% as Latina, 3.3% as Native American, and 7.5% as another or multiple racial backgrounds. Approximately, 65% were unemployed for at least one month prior to the study, whereas 26.4% and 8.5% reported working part- or full-time, respectively. The mean annual household income was $13,304.82 (SD=$10,389.85) and the mean years of education was 12.09 (SD=1.56). Most of the women (82.6%) reported that they were not married, 14.2% were married, and 3.3% were separated or divorced. Over half (56.6%) were living with their partner. Women reporting seeing their partner an average of 6.23 days a week (SD=1.40). Mean years in the current relationship was 6.48 years (ranging from 6 months to 33 years; SD=6.37 years).

Measures

Intimate partner victimization and aggression

A referent time period of six months was used to assess IPV in a current intimate relationship. Physical and psychological IPV were measured separately by the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-2; Straus, Hamby, & Warren, 2003). Consistent with scoring procedures outlined in Straus et al. (2003), responses were recoded to the midpoint of the range of scores (0=never, 25=more than 20 times). The 12 physical victimization (e.g., “My partner pushed or shoved me;” α=.89), 12 physical aggression (e.g., “I pushed or shoved my partner;” α=.88), 8 psychological victimization (e.g., “My partner insulted or swore at me;” α=.83), and 8 psychological aggression (e.g., “I insulted or swore at my partner;” α=.84) items were summed to create four severity scores, respectively. Sexual IPV was measured with the Sexual Experiences Survey (SES; Koss & Oros, 1982), which assesses sexual violence more comprehensively than the CTS-2 (e.g., the CTS-2 does not measure sexual coercion using drugs or alcohol). Because the SES was originally designed to measure women’s experiences of sexual victimization by any man, items were modified in order to collect information specifically regarding IPV. Further, each of the 10 sexual victimization items (e.g., “Has your partner tried to make you have sex by using force or by threatening to use force;” α=.89) were modified to assess sexual aggression (e.g., “Have you tried to make your partner have sex by using force or by threatening to use force;” α=.68). Finally, the SES was modified to match the CTS-2 response options and scoring system. Scores > 1 on the CTS-2 and SES indicated the presence of IPV.

Posttraumatic stress symptoms

The Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS; Foa, Cashman, Jaycox, & Perry, 1997) assesses the presence of PTSS during the past six months. PTSS were assessed in relation to women’s victimization by the current male partner. PTSS were rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale (0=not at all, or only one time; 3=5 or more times a week, or almost always) and summed. Cronbach’s α was .90.

Depressive symptoms

The Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) assesses depressive symptoms over the past six months. Depressive symptoms were rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale (0=rarely or none of the time, less than 1 day a week; 3 =most or all of the time, in the last week, 5 – 7 days a week) and summed. Cronbach’s α was .90.

Drug problems

The Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST; Skinner, 1982) assesses problems related to drug use over the past six months, such as occupational or relational problems, illegal activities, or regret. Drug problems were rated on a binary scale (1=yes, 0=no) and summed. Cronbach’s α was .90.

Alcohol problems

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993) assesses drinking behavior, adverse reactions, and problems during the past six months. Alcohol problems were rated on 5-point Likert-type scale (0=never; 4=daily or almost daily) and responses were summed. Cronbach’s α was .90.

Deliberate self-harm

The Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (DSHI; Gratz, 2001) assesses frequency and type of DSH. To reduce participant burden, we dropped questions with a low frequency of responses in Gratz’s (2001) study. Women were asked whether they had engaged in (1) cutting, (2) burning, (3) carving, (4) scratching, (5) sticking sharp objects into their skin, (6) preventing their wounds from healing, or (7) anything else to hurt themselves. A DSH frequency variable was computed by summing the total number of DSH episodes reported. A DSH versatility variable was computed by summing the number of unique types of DSH behaviors.

HIV-risk behavior

HIV-risk behaviors were assessed over the prior six months by an adapted measure regarding sexual behavior (Sikkema et al., 2008). Questions assessing HIV-risk were utilized in the current study and included: (1) unprotected anal/vaginal sex with their primary partner who was HIV-positive; (2) unprotected anal/vaginal sex with their primary partner who used intravenous drugs (or needles); (3) unprotected anal/vaginal sex with their primary partner who had multiple sexual partners; (4) unprotected anal/vaginal sex with a non-primary partner who was HIV-positive; and (5) trading sex for money, drugs, or shelter. HIV-risk behaviors were rated on a binary scale (1=yes, 0=no) and summed. Cronbach’s α was .90.

Data Analysis

Latent profile analysis (LPA), a type of person-centered mixture modeling, was used to identify classes of women based on severity of IPV types. LPA is a statistical approach to identify the number of homogeneous groups (i.e., classes) based on continuous latent variables. Mixture models, such as LPA, are superior to the more traditional cluster analytic methods in terms of enhanced reliability and ability to examine fit indices (DiStefano & Kamphaus, 2006). In the current study, a number of LPA models were estimated using Latent GOLD 4.0 (Vermunt & Magidson, 2005). The CTS-2 physical and psychological victimization and aggression scales and SES sexual victimization and aggression scales served as indicator variables. We examined the assumption of local independence (i.e., observed items are independent of each other given an individual’s score on the latent variable or class) by examining the bivariate residuals. High bivariate residuals suggest that the latent class may not fully account for associations between items. This assumption can be relaxed by including effects of high residuals in models (Vermunt & Magidson, 2005). Established recommendations guided model selection (see Berlin, Parra, & Williams, 2014). Unlike most statistical techniques, there is no single criterion for deciding on the number of LPA classes. Final model selection is based not only on the fit indices, but also model class sizes, parsimony, and theory. First, a variety of fit indices were compared, including the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC; Schwartz, 1978), Akaike Information Criteria (AIC; Akaike, 1987), and entropy (Ramaswamy, DeSarbo, Reibstein, & Robinson, 1993). Lower values on the BIC and AIC indicate better model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999), whereas entropy scores closer to 1 (range 0–1) indicate greater classification accuracy (Ramaswamy et al., 1993). Second, the Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT; McLachlan & Peel, 2000) was calculated to compare improvement between neighboring class models. Finally, given evidence to suggest that classes with fewer than 25 participants may restrict power and precision (Lubke & Neale, 2006), the size of the smallest class was examined. ANOVAs were utilized to examine between-group differences in victimization and aggression across the identified classes. Consistent with recommendations (Armstrong, 2014), post-hoc Bonferroni pairwise comparisons were conducted to correct for the problem of multiple comparisons and thus decrease the likelihood of making a Type I error.

Our second aim was to examine between-group differences in levels of psychopathology symptoms and risky behaviors across the IPV classes. We first exported the latent classes to SPSS version 21. We then examined the impact of demographic and relationship variables on psychopathology symptoms and risky behaviors (to identify potential covariates). The initial classes were compared to class membership when including direct effects of (a) demographic/relationship covariates or (b) bivariate residuals using chi-square tests and Cramer’s V (a measure of effect size) to examine if there is a robust association between classes with and without these covariates or residuals in the model. We then ran a series of ANOVAs/ANCOVAs to examine the effect of class membership on psychopathology symptoms and risky behaviors. Post-hoc Bonferroni pairwise comparisons were conducted.

Results

As might be expected from the victimization inclusion criteria in this sample, nearly all women reported physical and psychological victimization (100% and 100%, respectively) and aggression (92% and 98%, respectively), and approximately half reported sexual victimization and aggression (56% and 44%, respectively).

Latent Profile Analysis of IPV Classes

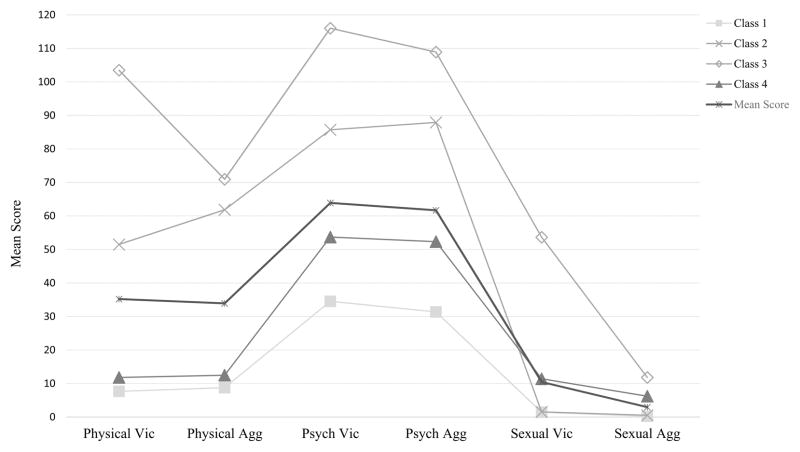

Model selection was determined following established guidelines (e.g., Berlin et al., 2014). The entropy value for the four-class solution indicates that a higher proportion of participants are correctly classified compared with the solutions with five or more classes. Further, the size of the smallest class for the four-class solution (but not solutions with five or more classes) fell within the acceptable range, suggesting that the four-class solution is superior with regards to power and precision. Indeed, the AIC and BIC demonstrated a large decrease from the one- to two-, two- to three-, and three- to four-class solutions; however, subsequent decreases through to the ten-class solution are much smaller. Importantly, as more classes are added to a model fit indices naturally tend to improve (DiStefano & Kamphaus, 2006). Thus, while the BLRT was significant for all the solutions, on the basis of parsimony, the four-class solution is preferred. As such, the four-class solution was considered optimal (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Fit Statistics for the Latent Profile Analysis

| Model | Fit Statistics | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Log Likelihood | AIC | BIC | Entropy | BLRT | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| 1 | −6,124.41 | 12,272.81 | 12,312.98 | 1.00 | 210 | ||||||||||

| 2 | −5,411.57 | 10,873.15 | 10,956.83 | 0.95 | < .001 | 130 | 80 | ||||||||

| 3 | −5,218.68 | 10,513.35 | 10,640.54 | 0.93 | < .001 | 103 | 63 | 44 | |||||||

| 4 | −5,088.33 | 10,278.65 | 10,449.36 | 0.93 | < .001 | 91 | 61 | 31 | 27 | ||||||

| 5 | −5,038.00 | 10,204.00 | 10,418.21 | 0.91 | < .001 | 84 | 55 | 28 | 25 | 18 | |||||

| 6 | −4,989.72 | 10,133.43 | 10,391.16 | 0.90 | < .001 | 59 | 57 | 27 | 25 | 25 | 17 | ||||

| 7 | −4946.38 | 10072.76 | 10374.00 | 0.91 | < .001 | 57 | 41 | 39 | 27 | 22 | 17 | 7 | |||

| 8 | −4930.62 | 10067.25 | 10412.00 | 0.92 | .002 | 62 | 47 | 29 | 24 | 16 | 15 | 12 | 5 | ||

| 9 | −4893.12 | 10018.25 | 10406.51 | 0.92 | < .001 | 57 | 48 | 23 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 5 | |

| 10 | −4893.03 | 10044.04 | 10475.81 | 0.92 | < .001 | 63 | 45 | 30 | 25 | 18 | 15 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 0 |

Note. AIC = Akaike Information Criteria. BIC = Bayesian Information Criteria. BLRT = Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test.

Figure 1. Latent Profile Solution for Physical, Psychological, and Sexual Intimate Partner Victimization and Aggression Indices.

Note. Vic = victimization; Agg = aggression; Psych = psychological. The x-axis denotes each of the physical, psychological, and sexual victimization and aggression scales. The y-axis denotes the mean score for each of the victimization and aggression scales. Latent classes are denoted via plotlines.

The mean frequencies of physical, psychological, and sexual victimization and aggression for each identified class were compared with the sample mean scores for these variables to determine relative severity (i.e., high>sample mean, low<sample mean; see overall mean column in Table 2). As indicated in Table 2, Class 1 (43%) was characterized by low physical, psychological, and sexual victimization and aggression. Class 2 (29%) was characterized by high physical and psychological victimization and aggression and low sexual victimization and aggression. Class 3 (15%) was characterized by high physical, psychological, and sexual victimization and aggression. Class 4 (13%) was characterized by low physical and psychological victimization and aggression and high sexual victimization and aggression. Probability of assignment to latent classes (ranging from .96 to .98) was well above the threshold of acceptable assignment probability (Nagin, 2006). We examined whether mean frequencies of victimization and aggression varied within each of the classes. Mean frequencies of physical and psychological victimization were not significantly different from mean frequencies of physical and psychological aggression for any of the classes (ps>.05); however, mean frequencies of sexual victimization were greater than mean frequencies of sexual aggression for each class (ps<.03).

Table 2.

Between-group Differences in Victimization and Aggression Types for the 4-class Model and Overall Sample

| Latent Profile Analysis Classes

|

Overall Sample (n = 210) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 (n = 91) | Class 2 (n = 61) | Class 3 (n = 31) | Class 4 (n = 27) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | F | np2 | |

| Physical Victimization | 7.65 (6.27)a | 51.49 (35.44)b | 103.48 (67.90)c | 11.81 (9.30)ad | 35.20 (47.05) | 76.52* | .53 |

| Psychological Victimization | 34.53 (23.77)a | 85.72 (38.56)b | 116.00 (44.18)c | 53.70 (29.78)ad | 63.89 (44.78) | 60.25* | .47 |

| Sexual Victimization | 1.45 (2.37)a | 1.54 (2.16)ab | 53.65 (51.94)c | 11.41 (10.25)abd | 10.45 (27.08) | 56.99* | .45 |

| Physical Aggression | 8.76 (8.63)a | 61.84 (51.51)b | 70.94 (59.95)bc | 12.48 (12.05)ad | 33.91 (45.70) | 39.60* | .37 |

| Psychological Aggression | 31.37 (23.59)a | 87.90 (38.54)b | 108.90 (45.66)c | 52.33 (29.32)d | 61.68 (44.93) | 60.37* | .47 |

| Sexual Aggression | 0.22 (0.55)a | 0.52 (1.01)b | 11.81 (16.97)c | 6.22 (6.19)d | 2.96 (8.45) | 26.49* | .28 |

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence. Means that do not share subscripts differ by p < .05 based on post-hoc Bonferroni pairwise comparisons.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

We examined whether demographic and relationship variables were associated with class indicators and class membership. Significant correlations emerged between psychological victimization and relationship status (p<.01), physical and psychological victimization and employment (ps<.05), and physical victimization and aggression and psychological aggression and income (ps<.05). When including these as active variables in a four-class LPA, comparable classifications emerged, χ2(9)=568.10, Cramer’s V=.95, p<.001, indicating that class membership did not vary as a function of these covariates. Thus, we chose to retained our initial model.

Consistent with recommendations for using Latent Gold (Vermunt & Magidson, 2005), we examined the bivariate residuals (0.34 to 12.35), and relaxed assumptions of local independence by including the direct effect residuals for high bivariate residuals (psychological victimization and aggression [17.20], physical and psychological aggression [12.35], physical and psychological victimization [6.99], physical victimization and aggression [6.03]). There were not substantial differences in model fit or participant classification (all participants were correctly classified in Classes 1 and 4, 54 of 61 [89%] were correctly classified in Class 2, 28 of 31 [90%] were correctly classified in Class 3), χ2(9)=555.50, Cramer’s V=.94, p<.001, thus we retained our initial model.

Associations between IPV Classes and Psychopathology Symptoms and Risky Behaviors

A series of ANOVAs, correlational, and chi-square analyses were conducted to examine the impact of demographic (i.e., age, race/ethnicity, income, education) and relationship (i.e., status, length of relationship, partner contact, living arrangement) variables on the independent and dependent variables. Class membership was only associated with partner contact (p<.05), although post-hoc Tukey’s tests were nonsignificant. For psychopathology symptoms, employment was related to greater PTSS and depressive symptoms (ps<.01); race/ethnicity to depressive symptoms (p<.05); relationship status to PTSS (p<.05); and partner contact to PTSS (p<.05). Regarding risky behaviors, race/ethnicity was related to DSH versatility (p<.05) and relationship status to HIV-risk behaviors (p<.001). Subsequent analyses included demographic and relationship variables related to the dependent variables. Given latent class differences in partner contact, this variable was not included (Miller & Chapman, 2001).

PTSS

Results revealed a main effect of class membership on PTSS controlling for employment and relationship status (Table 3). Greater PTSS were found for Class 3 (i.e., high physical, psychological, and sexual victimization and aggression) compared with Classes 1 (i.e., low physical, psychological, and sexual victimization and aggression) and 2 (i.e., high physical and psychological victimization and aggression and low sexual victimization and aggression; ps<.05). Classes 2 and 4 (i.e., low physical and psychological victimization and aggression and high sexual victimization and aggression) reported greater PTSS than Class 1 (ps<.05).

Table 3.

Between-group Differences in Psychopathology Symptoms and Risky Behaviors for the 4-classes and Overall Sample

| Class 1 (n = 91) | Class 2 (n = 61) | Class 3 (n = 31) | Class 4 (n = 27) | Overall Sample (n = 210) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | F | np2 | |

| PTSS | 12.22 (8.30)a | 21.47 (9.69)b | 27.74 (12.30)c | 21.22 (7.73)cbd | 18.24 (10.93) | 27.02*** | .29 |

| Depression Symptoms | 19.59 (10.05)a | 26.48 (10.73)b | 35.61 (13.47)c | 27.63 (8.88)bd | 24.90 (12.02) | 19.28*** | .22 |

| Drug Problemsa | 1.19 (1.85)a | 1.21 (2.38)ab | 2.59 (2.61)c | 2.52 (2.89)cd | 1.57 (2.34) | 5.93** | .09 |

| Alcohol Problems | 3.52 (5.30)a | 4.51 (5.52)ab | 8.00 (10.22)bc | 5.86 (8.04)abcd | 4.91 (6.92) | 2.88* | .05 |

| DSH Frequencyb | 7.32 (40.12)a | 6.93 (23.56)ab | 35.20 (94.02)bc | 12.39 (36.50)cd | 11.86 (48.61) | 10.43* | -- |

| DSH Versatility | 0.44 (0.93)a | 0.52 (1.03)ab | 1.06 (1.59)abc | 1.11 (1.58)bcd | 0.64 (1.19) | 4.19** | .06 |

| HIV-risk Severitya+ | 0.07 (0.26)a | 0.19 (0.40)ab | 0.35 (0.49)bc | 0.31 (0.47)abcd | 0.22 (0.53) | 4.23** | .06 |

Note. PTSS = posttraumatic stress symptoms. DSH = deliberate self-harm.

Square-root transformed.

Kruskal-Wallis H test.

HIV-risk severity was assessed among the subsample of HIV-negative women (n = 193). Means that do not share subscripts differ by p < .05 based on post-hoc Bonferroni pairwise comparisons.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Depressive symptoms

Results revealed a main effect of class membership on depressive symptoms controlling for employment and race/ethnicity (Table 3). Greater depressive symptoms were found for Class 3 compared with Classes 1, 2, and 4 (ps<.05). Classes 2 and 4 reported greater depressive symptoms than the Class 1 (ps<.001).

Drug problems

A square-root transformation was applied to correct skew and kurtosis. Results revealed a main effect of class membership on drug problems (Table 3). Greater drug problems were found for Classes 3 and 4 compared with Classes 1 and 2 (ps<.05).

Alcohol problems

Results revealed a main effect of class membership on alcohol problems (Table 3). Alcohol problems were higher for Class 3 compared with Class 1 (p<.05).

DSH frequency and versatility

Results revealed a main effect of class membership on DSH versatility controlling for race/ethnicity and DSH frequency (Table 3). Classes 3 and 4 endorsed greater DSH versatility than Class 1 (ps<.05). The DSH frequency variable was skewed and kurtotic, which could not be corrected via transformation. As such, we used a nonparametric analysis (Kruskal-Wallis H test). Class 3 exhibited greater DSH frequency than Class 1 (p<.05), whereas the difference between Classes 3 and 2 was marginal (p<.06). Class 4 demonstrated greater DSH frequency than Classes 1 and 2 (ps<.05).

HIV-risk behaviors

A square-root transformation was applied to correct skew and kurtosis. Results revealed a main effect of class membership on HIV-risk behaviors controlling for relationship status and excluding 19 HIV-positive women (see Table 3). Greater HIV-risk behaviors were found for Class 3 compared with Class 1 (p<.05).

Discussion

There are several noteworthy findings regarding the patterns of IPV across the identified classes. The four classes that emerged from the LPA were characterized by (1) low victimization/aggression across types, (2) high physical and psychological and low sexual victimization/aggression, (3) high victimization/aggression across types, and (4) low physical and psychological and high sexual victimization/aggression. Consistent with past research on the co-occurrence of physical and psychological victimization types (Coker et al., 2000; Sullivan et al., 2012), similar levels of physical and psychological victimization and aggression were detected within each of the classes. Conversely, sexual victimization and aggression varied both in relation to the other IPV types (i.e., sexual IPV was related to high physical and psychological IPV in some classes and low physical and psychological IPV in others) and in relation to each other (i.e., women reported greater sexual victimization than aggression in all classes). Regarding the relation between sexual IPV and other IPV types, Sullivan et al. (2012) found greater daily co-occurrence of physical and psychological victimization than physical and sexual victimization in a sample of IPV-victimized women. This, in combination with our findings, suggests that physical IPV may be more likely to occur in the context of psychological IPV, but less likely to co-occur with sexual IPV. Regarding the finding of greater sexual victimization than aggression within each of the IPV classes, research has consistently found that women are more likely to experience sexual victimization and less likely to use sexual aggression than their male counterparts (Hines & Saudino, 2003; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). Replication of these findings in larger, more diverse, representative samples is needed, as it is unclear whether these classes would emerge in other IPV populations (e.g., women recruited from shelters, in homo- or bi-sexual relationships, or with higher incomes).

Notably, levels of psychopathology symptoms and risky behaviors were found to differ across the four IPV classes. Women in classes defined by greater IPV generally exhibited higher PTSS and depressive symptoms. These findings are consistent with research that has found trauma severity to be uniquely associated with psychological correlates above and beyond trauma type (Clemmons, Walsh, DiLillo, & Messman-Moore, 2007), and suggest that severity of IPV, not IPV type, may be more relavent to the development, maintenance, and/or exacerbation of psychopathology symptoms in this population. Conversely, results indicate an overall trend toward greater risky behaviors among women in classes defined by higher sexual IPV. These findings are consistent with past research on the role of sexual victimization in risky behaviors (Stockman, Lucea, & Campbell, 2013), and underscore the need for research that examines why sexual IPV in particular is associated with risky behaviors. One possible explanation is that sexual IPV results in greater emotion dysregulation than physical or psychological IPV. Indeed, emotion dysregulation has been linked to sexual victimization (Messman-Moore, Ward, Zerubavel, Chandley, & Barton, 2015) and risky behaviors (Weiss, Sullivan, & Tull, 2015). Research examining emotion dysregulation and other potential mechanisms underlying the sexual IPV-risky behavior relation may inform interventions for this population.

Of note, it is also important to consider whether differences in psychopathology symptoms and risky behaviors across the IPV classes are clinically meaningful. The mean scores on measures of PTSS and depressive symptoms are consistent with mild PTSS and depressive symptoms for Class 1 and moderate to severe PTSS and severe depressive symptoms for Classes 2–4 (Foa et al., 1997; Radloff, 1977). While established cut-off scores do not exist for the DSH and HIV-risk measures, the mean score on the alcohol use measure fell in the problematic range only for Class 3 (Reinert & Allen, 2007), whereas the mean score on the drug use measure fell in the problematic range only for Classes 3 and 4 (Skinner, 1982). These findings further support the role of (a) IPV severity (vs. type) in psychopathology symptoms and (b) sexual IPV in risky behaviors.

While replication in more representative IPV samples is needed, several key implications arise from the current study. Our findings have important theoretical implications, suggesting that investigators should consider person-centered approaches for conceptualizing and testing the associations among IPV and health correlates. Moreover, results of this study may aid researchers and clinicians in identifying women who experience IPV and its negative sequelae. For instance, physical and psychological victimization and aggression were found to co-occur within each of the IPV classes, highlighting the need for assessing both victimization and aggression among populations of women identified by aggression (e.g., court samples) and victimization (e.g., shelter samples), respectively. Further, our results underscore the importance of utilizing comprehensive assessments of IPV. Researchers and clinicians do not always assess sexual IPV, yet women in a class characterized by low physical and psychological IPV reported high sexual IPV. These women reported heightened psychopathology symptoms and risky behaviors, however, they may not have been captured in traditional IPV assessments. Finally, our findings suggest the need for assessments that consider various characteristics of IPV (e.g., frequency and type, as well as others not assessed here, such as duration and use of force).

If confirmed in more representative IPV samples, our findings also highlight important targets for treatment. Community women in relationships characterized by heightened physical, psychological, and/or sexual IPV may benefit from treatments focused on reducing both PTSS and depressive symptoms (for treatments focused on reducing both PTSS and depressive symptoms among women currently experiencing IPV, see Crespo & Arinero, 2010; Johnson et al., 2011), whereas targeting risky behaviors may be warranted for those in relationships characterized by high sexual IPV in particular (for a treatment focused on reducing PTSS, depressive symptoms, substance use, and HIV-risk behaviors among women currently experiencing IPV, see Gilbert et al., 2006). Of note, co-occurring risky behaviors and/or psychopathology symptoms were common among the classes identified here, and the aforementioned treatments address co-occurring conditions simultaneously (consistent with extant research indicating that treatment outcomes are improved when co-occurring conditions are treated at the same time; Barlow, Allen, & Choate, 2004; Brady, Back, & Coffey, 2004). Finally, in combination with the plethora of research linking IPV to negative health outcomes, our findings underscore the need for identifying and evaluating policies that aim to reduce revictimization and related negative correlates among IPV-victimized women, particularly those with high levels of physical, psychological, and/or sexual victimization and aggression, such as the Affordable Care Act, which covers IPV screening and counseling, as well as mental health and substance abuse services.

Findings must be interpreted in light of limitations present. First and foremost, the cross-sectional and correlational nature of the data precludes determination of the precise nature and direction of the relations examined here. Future research should investigate these relations through prospective, longitudinal investigations. Second, this study relied exclusively on women’s self-report of IPV, which may have been influenced by their willingness and/or ability to report accurately (particularly given the potential stigma associated with IPV and the fact that this behavior may have occurred in the context of substance use). Moreover, situational and contextual factors relevant to IPV (e.g., motivations for aggression) were not assessed. Future research may benefit from collecting dyadic data on IPV from couples and considering the role of situational and contextual factors relevant to IPV. Finally, given evidence to suggest that victimization, psychopathology, and risky behaviors co-occur and synergistically impact negative outcomes (e.g., Singer & Clair, 2003), investigations may benefit from examining classes characterized by these factors and their correlates.

Acknowledgments

The research described here was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R03DA017668; K23DA039327; T32DA019426; T32MH020031).

References

- Akaike H. Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika. 1987;52:317–332. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong RA. When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2014;34:502–508. doi: 10.1111/opo.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Allen LB, Choate ML. Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:205–230. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin KS, Parra GR, Williams NA. An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 2): Longitudinal latent class growth analysis and growth mixture models. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2014;39:188–203. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogat GA, Levendosky AA, Von Eye A. The future of research on intimate partner violence: Person-oriented and variable-oriented perspectives. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;36:49–70. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-6232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle A, Jones P, Lloyd S. The association between domestic violence and self harm in emergency medicine patients. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2006;23:604–607. doi: 10.1136/emj.2005.031260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Back SE, Coffey SF. Substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13:206–209. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh CE, Hansen NB, Sullivan TP. HIV sexual risk behavior among low-income women experiencing intimate partner violence: The role of posttraumatic stress disorder. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:318–327. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9623-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmons JC, Walsh K, DiLillo D, Messman-Moore TL. Unique and combined contributions of multiple child abuse types and abuse severity to adult trauma symptomatology. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:172–181. doi: 10.1177/1077559506298248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, Bethea L, King MR, McKeown RE. Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000;9:451–457. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.5.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, McKeown RE, King MJ. Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: Physical, sexual, and psychological battering. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:553–457. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo M, Arinero M. Assessment of the efficacy of a psychological treatment for women victims of violence by their intimate male partner. The Spanish Journal of Psychology. 2010;13:849–863. doi: 10.1017/s113874160000250x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiStefano C, Kamphaus RW. Investigating subtypes of child development: A comparison of cluster analysis and latent class cluster analysis in typology creation. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2006;66:778–794. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA, Kaltman S, Goodman LA, Weinfurt K, Vankos N. Patterns of intimate partner violence: Correlates and outcomes. Violence and Victims. 2005;20:483–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:445–451. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HAFM, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. The Lancet. 2006;368:1260–1269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert L, El-Bassel N, Manuel J, Wu E, Go H, Golder S, … Sanders G. An integrated relapse prevention and relationship safety intervention for women on methadone: Testing short-term effects on intimate partner violence and substance use. Violence and Victims. 2006;21:657–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder S, Connell CM, Sullivan TP. Psychological distress and substance use among community-recruited women currently victimized by intimate partners: A latent class analysis and examination of between-class differences. Violence Against Women. 2012;18:934–957. doi: 10.1177/1077801212456991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL. Measurement of deliberate self-harm: Preliminary data on the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2001;23:253–263. [Google Scholar]

- Hines DA, Saudino KJ. Gender differences in psychological, physical, and sexual aggression among college students using the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales. Violence and Victims. 2003;18:197–217. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP. Conflict and control gender symmetry and asymmetry in domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:1003–1018. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Zlotnick C, Perez S. Cognitive behavioral treatment of PTSD in residents of battered women's shelters: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:542–551. doi: 10.1037/a0023822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Oros CJ. Sexual Experiences Survey: A research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:455–457. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Selwyn C, Rohling ML. Rates of bidirectional versus unidirectional intimate partner violence across samples, sexual orientations, and race/ethnicities: A comprehensive review. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:199–230. [Google Scholar]

- Lubke G, Neale MC. Distinguishing between latent classes and continuous factors: Resolution by maximum likelihood? Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2006;41:499–532. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4104_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino SC, Collins RL, Ellickson PL. Cross-lagged relationships between substance use and intimate partner violence among a sample of young adult women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2005;66:139–148. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan G, Peel D. Mixtures of factor analyzers. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore T, Ward RM, Zerubavel N, Chandley RB, Barton SN. Emotion dysregulation and drinking to cope as predictors and consequences of alcohol-involved sexual assault: Examination of short-term and long-term risk. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2014;30:601–621. doi: 10.1177/0886260514535259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA, Chapman JP. Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:40–48. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy V, DeSarbo WS, Reibstein DJ, Robinson WT. An empirical pooling approach for estimating marketing mix elasticities with PIMS data. Marketing Science. 1993;12:103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Reinert DF, Allen JP. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: An update of research findings. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:185–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz G. Estimating the dimension of a mode. The Annals of Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema KJ, Wilson PA, Hansen NB, Kochman A, Neufeld S, Ghebremichael MS, Kershaw T. Effects of a coping intervention on transmission risk behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS and a history of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;47:506–513. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318160d727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA. The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addictive Behaviors. 1982;7:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Thornton GE, DeVellis R, Earp J, Coker AL. A population-based study of the prevalence and distinctiveness of battering, physical assault, and sexual assault in intimate relationships. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:1208–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Stockman JK, Lucea MB, Campbell JC. Forced sexual initiation, sexual intimate partner violence and HIV risk in women: A global review of the literature. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17:832–847. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0361-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS-2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Warren WL. The Conflict Tactics Scales Handbook: Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2) and CTS: Parent-Child Version (CTSPC) Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, Cavanaugh CE, Buckner JD, Edmondson D. Testing posttraumatic stress as a mediator of physical, sexual, and psychological intimate partner violence and substance problems among women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22:575–584. doi: 10.1002/jts.20474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, McPartland TS, Armeli S, Jaquier V, Tennen H. Is it the exception or the rule? Daily co-occurrence of physical, sexual, and psychological partner violence in a 90-day study of substance-using, community women. Psychology of Violence. 2012;2:154. doi: 10.1037/a0027106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan SC, Snow DL. A typology of women's use of violence in intimate relationships. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:286–319. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevillion K, Oram S, Feder G, Howard LM. Experiences of domestic violence and mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2012;7:e51740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK, Magidson J. Latent GOLD 4.0 User’s Guide 1. Belmont, MA: Statistical Innovations Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Dixon-Gordon KL, Duke AA, Sullivan TP. The underlying role of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in the association between intimate partner violence and deliberate self-harm among African American women. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2015;59:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Sullivan TP, Tull MT. Explicating the role of emotion dysregulation in risky behaviors: A review and synthesis of the literature with directions for future research and clinical practice. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2015;3:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SL, Frieze IH. Patterns of violent relationships, psychological distress, and marital satisfaction in a national sample of men and women. Sex Roles. 2005;52:771–784. [Google Scholar]

- Zacarias AE, Macassa G, Soares JJF. Women as perpetrators of IPV: The experience of Mozambique. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research. 2012;4:5–27. [Google Scholar]