Abstract

Previous research suggests that green environments positively influence health. Several underlying mechanisms have been discussed; one of them is facilitation of social interaction. Further, greener neighborhoods may appear more aesthetic, contributing to satisfaction and well-being. Aim of this study was to analyze the association of residential surrounding greenness with self-rated health, using data from 4480 women and men aged 45–75 years that participated in the German population-based Heinz Nixdorf Recall study. We further aimed to explore the relationships of greenness and self-rated health with the neighborhood environment and social relations. Surrounding greenness was measured using the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) within 100 m around participants’ residence. As a result, we found that with higher greenness, poor self-rated health decreased (adjusted OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.82–0.98; per 0.1 increase in NDVI), while neighborhood satisfaction (1.41, 1.23–1.61) and neighborhood social capital (1.22, 1.12–1.32) increased. Further, we observed inverse associations of neighborhood satisfaction (0.70, 0.52–0.94), perceived safety (0.36, 0.22–0.60), social satisfaction (0.43, 0.31–0.58), and neighborhood social capital (0.53, 0.44–0.64) with poor self-rated health. These results underline the importance of incorporating green elements into neighborhoods for health-promoting urban development strategies.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11524-016-0112-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Surrounding greenness, Self-rated health, Neighborhood satisfaction, Social capital, NDVI

Introduction

The built environment has been broadly recognized as a determinant of human health [1]. Differences in health status within cities partially stem from differences in environmental conditions [2]. Greenness is an environmental feature which is increasingly studied in the context of health, and green environments have been linked to better population health [3–8] and reduced mortality [9] in previous research. Unfortunately, access to green space is often not equitably distributed with regard to socioeconomic background of city residents [10].

Next to the physical environment, the neighborhood comprises a social environment characterized, e.g., by good neighborly relationships. Both physical and social aspects of the neighborhood environment and how they are perceived may influence residents’ health [11]. A recent study found positive associations between trust of neighbors, exchange of help with neighbors, participation in social activities or organizations, and satisfaction with physical environments and self-rated health [12]. Considering the social environment, social relationships and networks are a valuable health resource [13–15] and represent a core aspect of the so-called social capital [16].

Attributes of neighborhoods may contribute to the health effects of social aspects [17], and it has been suggested that social cohesion may explain parts of the association of green space and health because green spaces offer opportunities to meet and connect [18]. The role of social contacts in the association between greenness and health has been investigated in a previous study [19] which found that loneliness and perceived shortage of social support partially mediated the relation between green space and health. Another study came up with the same result [20] and Sugiyama et al. similarly concluded that social coherence may contribute to the relationship between greenness and mental health, but found no empirical evidence for such an association for physical health [21].

In order to gain deeper insight into the complex relationships between the social and physical environment—and particularly surrounding greenness—and health, the aim of our study was to investigate the following:

The association between residential surrounding greenness and self-rated health,

The association between residential surrounding greenness and neighborhood environment (neighborhood satisfaction, perceived safety) and social relations (social satisfaction, neighborhood social capital), and

The associations of neighborhood environment (neighborhood satisfaction, perceived safety) and social relations (social satisfaction, neighborhood social capital) with self-rated health.

So far, the relationships between greenness in immediate residential surroundings and the mentioned neighborhood environment and social factors have been rarely studied, particularly in combination with self-rated health. Early observations [22] and more recent studies suggest that green and natural views (e.g., from a window) can have a positive impact on health by alleviating stress and facilitating mental restoration [22–25]. Therefore, we think it is important to study greenness in immediate residential surroundings in addition to, e.g., distance to parks and public green spaces, as the relationship with health, well-being, and satisfaction as well as with social ties may differ for different aspects of greenness.

Methods

Study Population

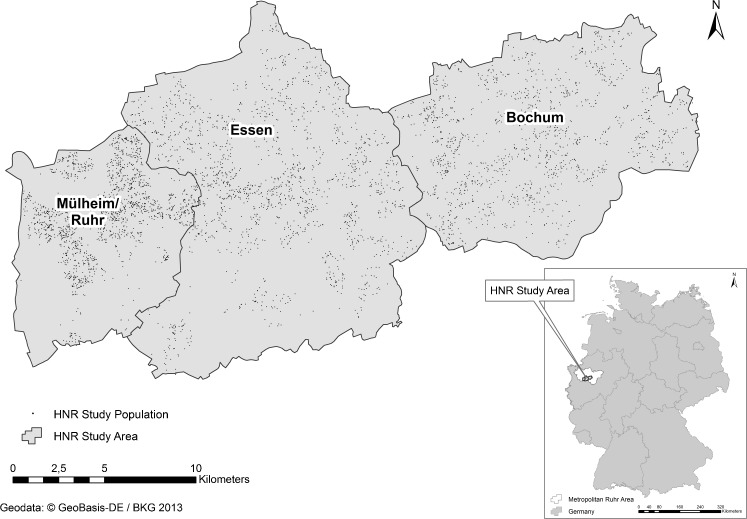

We analyzed data from participants of the Heinz Nixdorf Recall (HNR) study which was conducted in three adjacent cities (Bochum, Essen, and Mülheim/Ruhr) in the metropolitan Ruhr region in Germany (Fig. 1). Details of the design of the HNR have been published elsewhere [26]. In brief, study participants (n = 4814 women and men aged 45–75 years) were randomly selected from population registries and enrolled between 2000 and 2003. The examinations were performed in the Heinz Nixdorf Study Center, Essen, and the baseline response calculated as recruitment efficacy proportion was 55.8% [27]. The study maintained extensive quality management procedures, including a certification and re-certifications according to DIN ISO 9001:2000/2008. It was approved by the local ethics committees and all participants gave informed consent prior to participation.

Fig. 1.

Map of the location of the Heinz Nixdorf Recall (HNR) study area in Germany and the distribution of participants’ residences in the cities Mülheim/Ruhr, Essen, and Bochum

Exposure Assessment

Level of surrounding greenness at each participant’s residence was measured using the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) [28]. The NDVI is commonly used as an indicator of the presence and level of green vegetation. Values of NDVI range from −1 to +1; those approaching −1 generally correspond to water, while values around 0 represent bare surfaces with sparse vegetation, e.g., rock, rooftops, and roads, and values close to 1 represent dense green vegetation. It is calculated according to the level of reflectance of near-infrared and visible red wavelength spectra detected by satellite, using the formula [29]

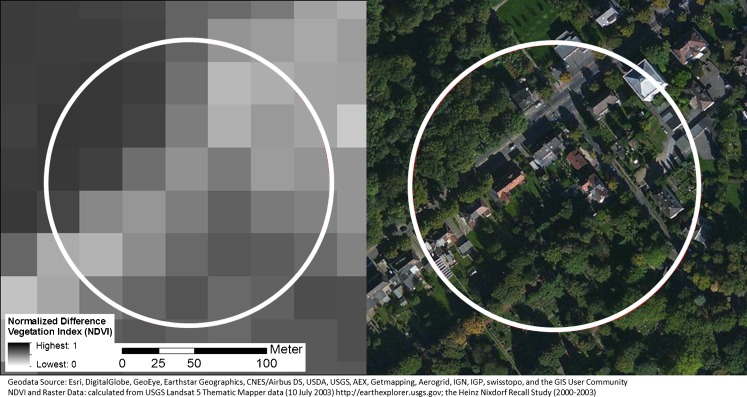

We calculated NDVI across the study area at a 30-m resolution based on United States Geological Survey Landsat 5 Thematic Mapper satellite data bands 3 and 4 (from 10 July 2003, a cloudless day), using the geographic information system (GIS) ArcMap 10.3.1. After excluding negative NDVI values to eliminate any confusion of water—a potentially positive environmental exposure—with poor greenness, we calculated the mean NDVI within a buffer of 100 m around the participants’ addresses (see Fig. 2) using Geospatial Modeling Environment. Residential surrounding greenness measured by NDVI thus refers to the general vegetation level in this area. The 100-m buffer was chosen to represent the immediate (“next-door”) neighborhood and has also been applied in previous studies using the NDVI [20, 30]. For additional analyses, we also calculated the NDVI in a buffer of 1000 m to apply a broader scale of neighborhood. We used this bigger difference to the 100-m buffer because mean NDVI in buffers of 250 and 300 m were strongly correlated with the 100-m values in our population (r = 0.8, p < 0.0001), while the 1000-m NDVI was less correlated (r = 0.5, p < 0.0001).

Fig. 2.

Raster layer with NDVI values in 30-m resolution (left) and a satellite image (right) showing the same area in a 100-m buffer. This example shows a mean NDVI of 0.5 in the 100-m buffer

Self-Rated Health

Information on self-rated health was obtained in a standardized computer-assisted personal interview by the question “How would you describe your overall health status during the last twelve months?” on a five-point Likert scale (“very good,” “good,” “fair,” “poor,” or “very poor”). This health measure was dichotomized, with the answers “poor” or “very poor” representing poor self-rated health status, in order to receive a binary outcome variable for easier interpretation of logistic regression estimates. Dichotomization of the self-rated health variable has been shown to provide robust results when compared with statistical approaches based on the original categories [31].

Neighborhood Environment and Social Relations

Participants rated satisfaction with their neighborhood (note: the term neighborhood refers to the physical residential environment in this context) and social relations, as well as trust in neighbors, helpfulness of neighbors, and perceived neighborhood safety in a questionnaire.

The questions “How satisfied are you with your residential area?” (neighborhood satisfaction) and “How satisfied are you with your relations to friends, neighbors, acquaintances?” (social satisfaction) could be answered by “very unsatisfied”, “rather unsatisfied,” “rather satisfied”, or “very satisfied”. Both of these items were dichotomized with “very/rather unsatisfied” being the negative and “very/rather satisfied” the positive response.

Agreement with the statements “Most people in my neighborhood are helpful”, “I can trust most people in my neighborhood”, and “I feel safe during daytime in the area where I live” (perceived safety) was expressed by the options “fully disagree”, “rather disagree” “rather agree” or “fully agree.” These items were dichotomized, with “fully/rather disagree” being the negative and “fully/rather agree” the positive response. The information on trust in and helpfulness of neighbors was combined to create a dichotomous variable neighborhood social capital. If participants responded positively concerning both helpfulness of and trust in neighbors, neighborhood social capital was categorized as high. Note that this definition assesses neighborhood social capital on individual level. Further, the scale of neighborhood/living area is not defined in the questionnaire and thus a matter of subjective interpretation.

Covariates

Information was obtained through standardized computer-assisted personal interviews and by self-completed paper and pencil questionnaires. Education and employment status were included as indicators of individual socioeconomic position (SEP). Education was defined by combining school and vocational training as total years of formal education according to the International Standard Classification of Education [32] and categorized into four groups (≤10, 11 to 13, 14 to 17, and ≥18 years). Employment status was also divided into four groups (employed, inactive/homemaker, retired, and unemployed).

Sociodemographic and behavioral covariates including date of birth, household size, and smoking (current, former or never-smoker) were assessed via standardized computer-assisted interviews. Height and weight were obtained by standardized anthropogenic measurements during the clinical examination. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as (weight in kg/[height in m]2).

We applied the 2001 unemployment rate in the respective city unit/district (German terms: in Essen “Stadtteil”, in Bochum and Mülheim/Ruhr “statistischer Bezirk”) as an indicator of neighborhood-level SEP. This data was obtained from the local census authorities of the respective cities of Bochum, Essen, and Mülheim/Ruhr [33].

Statistical Analyses

Of the 4814 participants at baseline, we excluded those with missing data on self-rated health (n = 13), neighborhood satisfaction (n = 107), perceived safety (n = 115), social satisfaction (n = 114), neighborhood social capital (n = 221), NDVI (n = 5), or covariates (n = 46). The final analysis sample included 4480 participants (93% of initial sample).

We used a logistic regression model to analyze the associations between neighborhood greenness and self-rated health (main analysis), as well as relationships of both of these factors with neighborhood satisfaction, perceived safety, social satisfaction, and neighborhood social capital. Odds ratios for the associations with greenness were calculated for an IQR (=0.1) increase in mean NDVI, as in other studies on residential greenness and health outcomes [20, 30, 34]. To account for potential confounding factors, we adjusted for age (continuous), sex, employment status, neighborhood-level SEP (unemployment rate, continuous), household size (>1 person, yes/no), BMI (continuous), and smoking (current, former, never). The included covariates were selected beforehand based on literature and hypothesized pathways. All analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.4.

To explore potentially differential effects in different population groups, we stratified the analysis on greenness and self-rated health by (i) sex, (ii) age (<60/≥60 years), (iii) education level (≤13/>13 years of formal education), (iv) physical activity (sports/no sports), and (v) city of residence.

Results

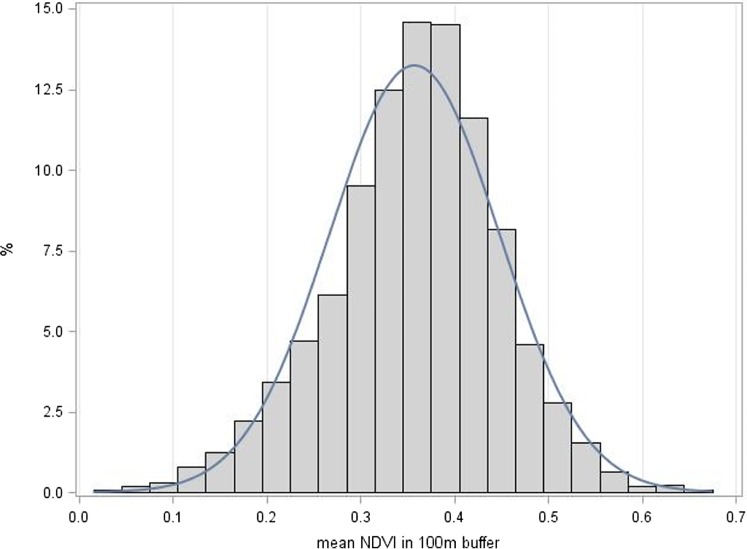

The mean/median NDVI in 100 m around participants’ residence was 0.36 (range 0.02–0.66; Q1 = 0.30, Q2 = 0.42) and 0.40 (range 0.19 to 0.60; Q1 = 0.36, Q2 = 0.43) in the 1000-m buffer. Surrounding greenness was approximately normally distributed (Fig. 3). The overall prevalence of poor self-rated health was 16.4% (n = 735; men 13.1%, women 19.8%). Characteristics of the study population by self-rated health status and by surrounding greenness in 100 m are shown in Table 1. Participants with poor self-rated health were more often female, unemployed, retired, and living alone. They also had lower education and were less physically active. No major differences in mean age and BMI were observed between those with poor and good self-rated health. A vast majority of the study population was satisfied with their neighborhood, felt safe in their neighborhood, was satisfied with their social relations, and reported high neighborhood social capital. We observed that those with lower education (≤13 years) were more likely to live within the lowest quartile of residential greenness (NDVI in 100 m ≤0.30) compared to those with higher education. The same applies to physically inactive participants, smokers, and those reporting low neighborhood social capital and low neighborhood satisfaction. There were no differences in mean age and BMI when comparing by greenness.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of greenness (mean NDVI in a 100-m buffer) in the study population (n = 4480); normal density curve

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population by self-rated health status and by level of surrounding greenness (n = 4480)

| Good health | Poor health | High 100-m NDVI (>0.30) | Low 100-m NDVI (≤0.30) | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Total | 3745 | 83.6 | 735 | 16.4 | 3415 | 76.2 | 1065 | 23.8 | 4480 | 100.0 |

| Female | 1786 | 47.7 | 440 | 59.9 | 1675 | 49.0 | 551 | 51.7 | 2226 | 49.7 |

| Education | ||||||||||

| ≤10 years | 346 | 9.2 | 119 | 16.2 | 334 | 9.8 | 131 | 12.3 | 465 | 10.4 |

| 11–13 years | 2081 | 55.6 | 420 | 57.1 | 1872 | 54.9 | 629 | 58.9 | 2501 | 55.8 |

| 14–17 years | 870 | 23.2 | 148 | 20.1 | 800 | 23.4 | 218 | 20.4 | 1018 | 22.7 |

| ≥18 years | 448 | 12.0 | 48 | 6.5 | 408 | 11.9 | 88 | 8.3 | 496 | 11.1 |

| Employment status | ||||||||||

| Employed | 1627 | 43.4 | 221 | 30.1 | 1393 | 40.8 | 458 | 42.7 | 1848 | 41.3 |

| Inactive/homemaker | 475 | 12.7 | 123 | 16.7 | 460 | 13.5 | 138 | 13.0 | 598 | 13.3 |

| Retired | 1430 | 38.2 | 317 | 43.1 | 1355 | 39.7 | 392 | 36.8 | 1747 | 39.0 |

| Unemployed | 213 | 5.7 | 74 | 10.1 | 207 | 6.1 | 80 | 7.5 | 287 | 6.4 |

| Household size >1 person | 3177 | 84.8 | 563 | 76.6 | 2911 | 85.2 | 829 | 77.8 | 3740 | 83.5 |

| No sports | 1611 | 43.0 | 428 | 58.2 | 1507 | 44.1 | 532 | 50.0 | 2039 | 45.5 |

| Smoking | ||||||||||

| Non-smoker | 1566 | 41.8 | 311 | 42.3 | 1448 | 42.4 | 429 | 40.3 | 1877 | 41.9 |

| Former smoker | 1330 | 35.5 | 238 | 32.4 | 1216 | 35.6 | 352 | 33.1 | 1568 | 35.0 |

| Current smoker | 849 | 22.7 | 186 | 25.3 | 751 | 22.0 | 284 | 26.7 | 1035 | 23.1 |

| Neighborhood satisfaction (satisfied) | 3532 | 94.3 | 670 | 91.2 | 3241 | 94.9 | 961 | 90.2 | 4202 | 93.8 |

| Perceived safety (feel safe) | 3701 | 98.8 | 708 | 96.3 | 3368 | 98.6 | 1041 | 97.7 | 4409 | 98.4 |

| Social satisfaction (satisfied) | 3598 | 96.1 | 671 | 91.3 | 3251 | 95.2 | 1018 | 95.6 | 4269 | 95.3 |

| Neighborhood social capital (high) | 3103 | 82.9 | 524 | 71.3 | 2823 | 82.7 | 804 | 75.5 | 3627 | 81.0 |

| NDVI (100 m) ≤0.30 | 860 | 23.0 | 205 | 27.9 | – | – | – | – | 1065 | 23.8 |

| City of residence | ||||||||||

| Mülheim/Ruhr | 1401 | 37.4 | 253 | 34.4 | 1263 | 37.0 | 391 | 36.7 | 1654 | 36.9 |

| Bochum | 1107 | 29.6 | 202 | 27.5 | 1073 | 31.4 | 236 | 22.2 | 1309 | 29.2 |

| Essen | 1237 | 33.0 | 280 | 38.1 | 1079 | 31.6 | 438 | 41.1 | 1517 | 33.9 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age | 59.4 | 7.7 | 60.0 | 7.9 | 59.5 | 7.7 | 59.4 | 8.0 | 59.5 | 7.8 |

| Body mass index | 27.7 | 4.4 | 28.6 | 5.4 | 27.8 | 4.5 | 28.2 | 4.9 | 27.9 | 4.6 |

| NDVI 100-m buffer | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.35 | 0.09 | 0.40 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.36 | 0.09 |

| NDVI 1000-m buffer | 0.40 | 0.06 | 0.39 | 0.06 | 0.41 | 0.05 | 0.35 | 0.06 | 0.40 | 0.06 |

| % unemployed in district | 12.4 | 3.4 | 12.9 | 3.6 | 12.1 | 3.3 | 13.9 | 3.6 | 12.5 | 3.4 |

Residential Surrounding Greenness and Self-Rated Health

The regression analysis revealed an inverse association of higher greenness and poor self-rated health, with an adjusted OR of 0.90 (95% CI 0.82–0.98) per 0.1-increase in NDVI within the 100-m buffer. The crude OR did not differ much (Table 2). The association between greenness and self-rated health was similar in the 1000-m buffer with an adjusted OR of 0.90 (95% CI 0.77–1.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for the associations between surrounding greenness, neighborhood environment and social relations, and self-rated health (n = 4480)

| Poor self-rated health | Neighborhood satisfaction (satisfied) | Perceived safety (feel safe) | Social satisfaction (satisfied) | Neighborhood social capital (high) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDVI 100 ma | |||||

| Unadjusted | 0.85 (0.78, 0.93) | 1.59 (1.40, 1.81) | 1.37 (1.06, 1.75) | 1.11 (0.95, 1.29) | 1.32 (1.21, 1.43) |

| Adjustedb | 0.90 (0.82, 0.98) | 1.41 (1.23, 1.61) | 1.12 (0.86, 1.44) | 0.98 (0.84, 1.15) | 1.22 (1.12, 1.32) |

| NDVI 1000 ma | |||||

| Unadjusted | 0.77 (0.68, 0.88) | 2.05 (1.68, 2.49) | 1.80 (1.23, 2.62) | 1.31 (1.04, 1.63) | 1.55 (1.37, 1.76) |

| Adjustedb | 0.90 (0.77, 1.05) | 1.54 (1.23, 1.94) | 1.08 (0.70, 1.68) | 1.09 (0.84, 1.42) | 1.36 (1.18, 1.57) |

| Poor self-rated health (=dependent variable) | |||||

| Unadjusted | – | 0.62 (0.47, 0.83) | 0.31 (0.19, 0.51) | 0.43 (0.32, 0.58) | 0.51 (0.43, 0.62) |

| Adjustedb | – | 0.70 (0.52, 0.94) | 0.36 (0.22, 0.60) | 0.43 (0.31, 0.58) | 0.53 (0.44, 0.64) |

aOR per 0.1 NDVI increase

bAdjusted for age, sex, employment status, neighborhood-level SEP, household size, BMI, and smoking

Stratified analyses indicated no differences in the association between greenness and self-rated health by gender, education, and city of residence. Comparisons by age group and physical activity revealed that the association was present only among participants younger than 60 years and those who were physically inactive (Table 3).

Table 3.

Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for the association between a 0.1 increase in NDVI (100 m) and poor self-rated health in different population strata

| Cases (N) | Total (N) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 295 | 2254 | 0.84 (0.74, 0.97) | 0.91 (0.79, 1.06) |

| Female | 440 | 2226 | 0.86 (0.77, 0.96) | 0.89 (0.79, 1.00) |

| Age | ||||

| <60 years | 382 | 2388 | 0.77 (0.69, 0.87) | 0.84 (0.74, 0.95) |

| ≥60 years | 353 | 2092 | 0.96 (0.84, 1.09) | 0.97 (0.85, 1.11) |

| Education | ||||

| ≤13 years | 539 | 2966 | 0.87 (0.79, 0.96) | 0.91 (0.82, 1.01) |

| >13 years | 196 | 1514 | 0.86 (0.72, 1.01) | 0.88 (0.74, 1.05) |

| Sports | ||||

| Yes | 307 | 2441 | 0.94 (0.82,1.08) | 1.01 (0.88, 1.16) |

| No | 428 | 2039 | 0.82 (0.73, 0.92) | 0.83 (0.73, 0.93) |

| City of residence | ||||

| Mülheim/Ruhr | 253 | 1654 | 0.88 (0.75, 1.03) | 0.91 (0.76, 1.09) |

| Bochum | 202 | 1309 | 0.86 (0.72, 1.02) | 0.88 (0.73, 1.05) |

| Essen | 280 | 1517 | 0.85 (0.75, 0.97) | 0.91 (0.79, 1.04) |

aAdjusted for age (not in age-strata), sex (not in sex-strata), employment status, neighborhood-level SEP, household size, BMI, and smoking

Residential Surrounding Greenness and Neighborhood Environment and Social Relations

An increase of 0.1 in NDVI in the 100-m buffer was positively associated with neighborhood satisfaction (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.23–1.61) and neighborhood social capital (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.12–1.32) in the adjusted model, but not with perceived safety (OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.86–1.44) and social satisfaction (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.84–1.15). As shown in Table 2, the crude estimates were somewhat decreased by adjustment, particularly for neighborhood satisfaction (crude OR 1.59) and perceived safety (crude OR 1.37). Magnitude of the associations was similar considering NDVI in a 1000-m buffer. It is noticeable that the effect of adjustment on the crude estimates for neighborhood satisfaction (crude OR 2.05) and perceived safety (crude OR 1.80) was even more pronounced for the association with greenness in 1000 m around the residence.

Neighborhood Environment and Social Relations and Self-Rated Health

Results of the regression analysis showed a negative association between all investigated aspects of the neighborhood environment and social relations with poor self-rated health (Table 2). The OR for poor self-rated health in the adjusted model was lowest for those reporting high perceived safety (0.36, 95% CI 0.22–0.60), followed by those with high social satisfaction (0.43, 95% CI 0.31–0.58), high neighborhood social capital (0.53; 95% CI 0.44–0.64), and high neighborhood satisfaction (0.70, 95% CI 0.52–0.94).

Further Results

Neighborhood satisfaction and social satisfaction were positively associated with neighborhood social capital and were also strongly associated with each other (for estimates see Supplement, Table S1a and b). Social satisfaction was more strongly associated with neighborhood social capital than neighborhood satisfaction, while neighborhood satisfaction showed a more pronounced association with perceived safety, which was not significantly associated with social satisfaction.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that a 0.1-increase in residential NDVI reduced the odds of poor self-rated health by approximately 10%, considering both the 100- and 1000-m scale and taking into account potential confounders. Further, residential greenness was positively associated with neighborhood satisfaction and neighborhood social capital which in turn were also associated with less poor self-rated health. Social satisfaction and perceived safety were associated with better health, but not with greenness.

Our results are in line with previous studies, where greenness has shown associations with different health aspects and outcomes [6, 35]. When comparing our results to those of other studies, it is important to bear in mind that a variety of different methods has been used to assess “greenness” in this research field [36]. These include subjective perception of greenness [21] or self-reports of visiting green space [37], access to public green spaces such as parks as well as objective measures of surrounding greenness at residence, such as the NDVI applied in our study. Nevertheless, other studies that used objective measures of greenness as exposure variable and self-rated health as an outcome show results that point in the same direction as ours [20, 38, 39].

A connection between greenness and health seems intuitively plausible, but the mechanisms are not yet fully understood. For example, proximity to green spaces such as parks may encourage physical activity and thus promote health. However, our aim was to investigate the impact of residential surrounding greenness using the NDVI, so the access to green recreational areas was not measured in our study. We found an association between greenness and health only in the physically inactive, and those with lower surrounding greenness were less physically active in our study, which may imply higher health benefits from physical activity than from greenness. A review of studies comparing physical and mental well-being benefits of indoor vs. outdoor physical activity found some support favoring activity in natural outdoor environments, but the authors caution that further research is needed in this area [40]. Yet, in our study we had no information on whether physical activity was performed outdoors. Based on what is known from previous research and our study results, we assume that green surroundings positively influence health, well-being, and satisfaction. This would be in line with the so-called biophilia hypothesis introduced by Edward O. Wilson [41]. It describes an innate affinity towards nature and other living beings which is, as a result of evolution, deeply rooted in the human biology. Thus, humans would be born with a preference for natural elements and surroundings, and consequently, a lack of these may impair their well-being. The biophilia hypothesis finds support in a large variety of publications including experimental and observational research on stress recovery, visual and restorative effects of nature and green, physical activity in natural environments, and diverse aspects of human health and well-being [42, 43].

Our result of increased neighborhood satisfaction in the presence of higher surrounding greenness further confirms a preference of green environments and stresses the necessity of incorporating natural elements in the design of urban living areas. This association has been observed in previous studies as well. For example, Hur et al. [44]. found correlations of both objective greenness (NDVI) and perceived naturalness and openness with overall neighborhood satisfaction in a sample of 725 homeowners in Franklin County, Ohio. Similarly, a Swedish study of 24,847 public health survey participants found associations of perceived green qualities with neighborhood satisfaction, physical activity, and general health which were mostly confirmed for GIS-assessed green qualities [45]. Another study [46] found associations with various aspects of GIS-measured landscape structure, such as variety in size and shape of tree patches, and neighborhood satisfaction in a mailed survey including 311 single-family households in the city of College Station, Texas. Results like these were also found in an analysis of the LARES survey [7]. Overall, it is not fully clear how greenness and nature add to neighborhood satisfaction, especially if it does more than increasing the neighborhood’s attractiveness.

We observed an association of surrounding greenness with neighborhood social capital, but not with social satisfaction and perceived safety. This may be because social satisfaction is influenced by various factors that may outweigh the impact of greenness. Also, this variable may depend more on social relationships that exist outside the neighborhood, as opposed to the neighborhood social capital (e.g., friends/family vs. neighbors). Participants more frequently reported social satisfaction than high neighborhood social capital. It is striking that social satisfaction did not differ by greenness, while neighborhood social capital showed big differences by both greenness and self-rated health status (Table 1). One possible explanation for this finding is that participants with lower greenness may be likelier to live in deprived neighborhoods. Previous studies [47, 48] have found that living in deprived neighborhoods was associated with lower social capital (in terms of trusting neighbors, helping each other out, etc.), which may add to the observed result in our study. Considering perceived safety, total number of participants who did not feel safe was very limited (n = 71) and thus confidence intervals were rather broad for the greenness-safety relationship. The odds ratio showed a tendency towards a positive effect of higher greenness on perceived safety, though, and safety was also related to neighborhood satisfaction. One advantage of our study is that we had the opportunity to study both social satisfaction in general and social capital specifically relating to neighbors. Social relations have been investigated in the context of greenness and health before, and some studies support the hypothesis of potential mediation in this context [19, 20, 49]. In contrast, Fan et al. [50] found a negative effect of neighborhood greenness on social support. An earlier study found an association between the use of green outdoor common spaces and social ties and sense of community in a sample of 91 elderly inner city inhabitants [51]. It is possible that both greenness and relations with neighbors influence the perception of the neighborhood (satisfaction). Though the question “How satisfied are you with your residential area?” intends to capture satisfaction with the physical environment, answers to it may not only reflect the respondent’s attitude towards physical aspects but also the perception of the people sharing the neighborhood, depending on the interpretation of the question.

Regarding the association between neighborhood satisfaction and self-rated health found in our study, our results also support previous research. A Japanese study (n = 8139) observed an association of neighborhood dissatisfaction with poor self-rated health with an OR of 1.22 (95% CI 1.04–1.42), adjusting for various contextual and individual factors, including personality traits and sense of coherence [52]. Another study analyzed data of 199,790 participants of the Korean Community Health Survey [12]. This study used similar questionnaire instruments as the HNR study and found that trust of neighbors, exchange of help with neighbors, frequent contact with friends/neighbors, and satisfaction with the physical environment, including perceived safety, were positively associated with self-rated health in both urban and rural communities, after adjusting for relevant confounding factors. Similar results were reported based on findings from a computer-assisted telephone survey carried out in Vancouver which also found that neighborhood dissatisfaction was associated with fair/poor self-reported health (OR 2.24, 95% CI 1.65–3.03) [53]. It is tempting to suggest that satisfaction increases health, which has also been found in a previous prospective study on life satisfaction and health [54]. However, it is not possible to infer the direction of this association from our cross-sectional design. Those who report better health may generally be more satisfied with other aspects of their life, including their neighborhood and social relations. For instance, neighborhood satisfaction and social satisfaction were strongly associated (supplement, Table S1). Also, information about perception of the neighborhood and social environment as well as individual health was obtained from self-reports by the same individuals, which may introduce same-source bias [55].

General strengths of this study include an objective measure of greenness based on high-quality satellite imagery and individual exposure assessment based on residential addresses. The outcome self-rated health was assessed by a widely used and simple instrument which has been shown to well-reflect objective health status [56]. We investigated a large number of randomly selected participants, allowing associations to be studied in different subgroups. Furthermore, comprehensive measurements enabled inclusion of many potential confounding factors in our analyses. We had only few dropouts due to missing data (7% of the initial cohort), which makes bias due to missing data unlikely.

Regarding limitations of our study apart from already mentioned ones, the exposure assessment has some drawbacks. While the NDVI is considered a good tool for quantifying neighborhood greenness [28], it does not provide information about the present type, or “quality,” of greenness. It is not possible to distinguish trees from grass or bushes using the NDVI, for example. Future research would thus profit from additionally incorporating measures of type or quality of greenness. This is important for city planners, as there may be specific types of greenness that are particularly valuable for health [57]. Also, we had no information about actual use of the greenness, non-residential exposures to greenness such as park visits, or time spent in other environments, including the workplace. This may contribute to exposure misclassification. Further, causal inference is not possible based on the cross-sectional study design. We investigated a general population sample of middle-aged and older men and women living in an urbanized area in Germany and hence our results cannot be generalized to populations from other countries, or children, young adults, and residents of very rural areas. While most previous studies on health effects of green environments have focused on adult populations, several studies support associations of greenness with different health indicators in children as well [58–60].

Conclusion

According to our results, there is an association between residential surrounding greenness and self-rated health. This result adds to existing evidence suggesting that greenness is a beneficial health resource. Further, higher greenness was associated with neighborhood satisfaction and neighborhood social capital, which were also associated with better self-rated health. Incorporating green elements even in small-scale neighborhoods may represent an important mean of improving city dwellers’ health and well-being, possibly also by positively influencing social capital. In this context, the importance of creating environmental equality cannot be stressed enough, especially as we—like other authors before—found an unequal distribution of greenness by socioeconomic position. Since various different methods are used to study green environments, improving understanding of what these different indicators of greenness measure and how they can be evaluated and combined in health research are crucial tasks for further research.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOCX 16 kb)

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to all study participants and to the dedicated personnel of the study center and data management center of the Heinz Nixdorf Recall study. We thank the city councils of Bochum, Essen, and Mülheim, Germany, for providing data. We further thank Birgit Sattler from the University of Duisburg-Essen for GIS counseling.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding Information

The study was funded by the Heinz Nixdorf Foundation, Germany [Chairman: M. Nixdorf; Past Chairman: Dr. Jur. G. Schmidt (deceased)]. The study was also supported by grants from the German Research Council (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft; ER 155/6-1, ER 155/6-2, SI 236/8-1 and SI 236/9-1) and the Kulturstiftung Essen, Germany.

References

- 1.Yen IH, Michael YL, Perdue L. Neighborhood environment in studies of health of older adults. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(5):455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Environment and health risks: a review of the influence and effects of social inequalities. 2010. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/78069/E93670.pdf. Accessed 28 Oct 2016.

- 3.Maas J. Green space, urbanity, and health: how strong is the relation? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(7):587–592. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.043125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Vries S, Verheij RA, Groenewegen PP, Spreeuwenberg P. Natural environments—healthy environments? An exploratory analysis of the relationship between greenspace and health. Environ Plan A. 2003;35(10):1717–1731. doi: 10.1068/a35111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell R, Popham F. Greenspace, urbanity and health: relationships in England. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(8):681–683. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.053553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee ACK, Maheswaran R. The health benefits of urban green spaces: a review of the evidence. J Public Health. 2011;33(2):212–222. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braubach M. Residential conditions and their impact on residential environment satisfaction and health: results of the WHO large analysis and review of European housing and health status (LARES) study. Int J Environ Pollut. 2007;30(3/4):384–403. doi: 10.1504/IJEP.2007.014817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartig T, Mitchell R, de Vries S, Frumkin H. Nature and health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35(1):207–228. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gascon M, Triguero-Mas M, Martínez D, et al. Residential green spaces and mortality: a systematic review. Environ Int. 2016;86:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolch JR, Byrne J, Newell JP. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: the challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landsc Urban Plan. 2014;125:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poortinga W, Dunstan FD, Fone DL. Perceptions of the neighbourhood environment and self rated health: a multilevel analysis of the Caerphilly Health and Social Needs Study. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):285. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J, Park J, Kim M. Social and physical environments and self-rated health in urban and rural communities in Korea. IJERPH. 2015;12(11):14329–14341. doi: 10.3390/ijerph121114329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chuang Y, Chuang K, Yang T. Social cohesion matters in health. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2013;12(87). http://www.equityhealthj.com/content/12/1/87. Accessed 28 Oct 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Reblin M, Uchino BN. Social and emotional support and its implication for health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(2):201–205. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f3ad89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umberson D, Montez JK. Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(1 Suppl):S54. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol. 1988;94:S95–S120. doi: 10.1086/228943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macintyre S, Ellaway A, Cummins S. Place effects on health: how can we conceptualise, operationalise and measure them? Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(1):125–139. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groenewegen PP, van den Berg AE, Maas J, Verheij RA, de Vries S. Is a green residential environment better for health? If so, why? Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 2012;102(5):996–1003. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2012.674899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maas J, van Dillen SM, Verheij RA, Groenewegen PP. Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relation between green space and health. Health Place. 2009;15(2):586–595. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dadvand P, Bartoll X, Basagaña X, et al. Green spaces and general health: roles of mental health status, social support, and physical activity. Environ Int. 2016;91:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugiyama T, Leslie E, Giles-Corti B, Owen N. Associations of neighbourhood greenness with physical and mental health: do walking, social coherence and local social interaction explain the relationships? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(5):e9. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.064287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ulrich RS. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science. 1984;224(4647):420–421. doi: 10.1126/science.6143402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan R. Nature of the view from home: psychological benefits. Environ Behav. 2001;33(4):507–542. doi: 10.1177/00139160121973115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honold J, Lakes T, Beyer R, van der Meer E. Restoration in urban spaces: nature views from home, greenways, and public parks. Environ Behav. 2016;48(6):796–825. doi: 10.1177/0013916514568556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ulrich RS, Simons RF, Losito BD, Fiorito E, Miles MA, Zelson M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J Environ Psychol. 1991;11(3):201–230. doi: 10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80184-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmermund A, Möhlenkamp S, Stang A, et al. Assessment of clinically silent atherosclerotic disease and established and novel risk factors for predicting myocardial infarction and cardiac death in healthy middle-aged subjects: rationale and design of the Heinz Nixdorf RECALL Study. Am Heart J. 2002;144(2):212–218. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.123579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stang A, Moebus S, Dragano N, et al. Baseline recruitment and analyses of nonresponse of the Heinz Nixdorf recall study: identifiability of phone numbers as the major determinant of response. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005;20(6):489–496. doi: 10.1007/s10654-005-5529-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rhew IC, Vander Stoep A, Kearney A, Smith NL, Dunbar MD. Validation of the normalized difference vegetation index as a measure of neighborhood greenness. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(12):946–952. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weier J, Herring D. Measuring Vegetation (NDVI & EVI). http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Features/ MeasuringVegetation/printall.php. Accessed 28 Oct 2016.

- 30.Hystad P, Davies HW, Frank L, et al. Residential greenness and birth outcomes: evaluating the influence of spatially correlated built-environment factors. Environ Health Perspect. 2014 doi: 10.1289/ehp.1308049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manor O, Matthews S, Power C. Dichotomous or categorical response? Analysing self-rated health and lifetime social class. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29(1):149–157. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. International standard classification of education ISCED 1997. English edition.—Re-edition. Montreal, QC: UNESCO-UIS; 2006.

- 33.Dragano N, Hoffmann B, Stang A, et al. Subclinical coronary atherosclerosis and neighbourhood deprivation in an urban region. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24(1):25–35. doi: 10.1007/s10654-008-9292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dadvand P, Sunyer J, Basagaña X, et al. Surrounding greenness and pregnancy outcomes in four Spanish birth cohorts. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(10):1481–1487. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.James P, Banay RF, Hart JE, Laden F. A review of the health benefits of greenness. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2015;2(2):131–142. doi: 10.1007/s40471-015-0043-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jorgensen A, Gobster PH. Shades of green: measuring the ecology of urban green space in the context of human health and well-being. Nature and Culture. 2010;5(3). doi:10.3167/nc.2010.050307.

- 37.van den Berg M, van Poppel M, van Kamp I, et al. Visiting green space is associated with mental health and vitality: a cross-sectional study in four European cities. Health Place. 2016;38:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maas J, Verheij RA, Spreeuwenberg P, Groenewegen PP. Physical activity as a possible mechanism behind the relationship between green space and health: a multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):206. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Triguero-Mas M, Dadvand P, Cirach M, et al. Natural outdoor environments and mental and physical health: relationships and mechanisms. Environ Int. 2015;77:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson Coon J, Boddy K, Stein K, Whear R, Barton J, Depledge MH. Does participating in physical activity in outdoor natural environments have a greater effect on physical and mental wellbeing than physical activity indoors? A systematic review. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45(5):1761–1772. doi: 10.1021/es102947t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson EO. Biophilia. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grinde B, Patil GG. Biophilia: does visual contact with nature impact on health and well-being? IJERPH. 2009;6(9):2332–2343. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6092332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gullone E. The biophilia hypothesis and life in the 21st century: increasing mental health or increasing pathology? J Happiness Stud. 2000;1:293–321. doi: 10.1023/A:1010043827986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hur M, Nasar JL, Chun B. Neighborhood satisfaction, physical and perceived naturalness and openness. J Environ Psychol. 2010;30(1):52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Jong K, Albin M, Skärbäck E, Grahn P, Björk J. Perceived green qualities were associated with neighborhood satisfaction, physical activity, and general health: results from a cross-sectional study in suburban and rural Scania, southern Sweden. Health Place. 2012;18(6):1374–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee S, Ellis CD, Kweon B, Hong S. Relationship between landscape structure and neighborhood satisfaction in urbanized areas. Landsc Urban Plan. 2008; 85(1): 60–70.

- 47.Nettle D, Colléony A, Cockerill M, Moreno Y. Variation in cooperative behaviour within a single city. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e26922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hill JM, Jobling R, Pollet TV, Nettle D. Social capital across urban neighborhoods: a comparison of self-report and observational data. Evol Behav Sci. 2014;8(2):59–69. doi: 10.1037/h0099131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Vries S, van Dillen SM, Groenewegen PP, Spreeuwenberg P. Streetscape greenery and health: stress, social cohesion and physical activity as mediators. Soc Sci Med. 2013;94:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fan Y, Das KV, Chen Q. Neighborhood green, social support, physical activity, and stress: assessing the cumulative impact. Health Place. 2011;17(6):1202–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kweon B, Sullivan WC, Wiley AR. Green common spaces and the social integration of inner-city older adults. Environ Behav. 1998;30(6):832–858. doi: 10.1177/001391659803000605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oshio T, Urakawa K. Neighbourhood satisfaction, self-rated health, and psychological attributes: a multilevel analysis in Japan. J Environ Psychol. 2012;32(4):410–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Collins PA, Hayes MV, Oliver LN. Neighbourhood quality and self-rated health: a survey of eight suburban neighbourhoods in the Vancouver Census Metropolitan Area. Health Place. 2009;15(1):156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siahpush M, Spittal M, Singh GK. Happiness and life satisfaction prospectively predict self-rated health, physical health, and the presence of limiting, long-term health conditions. Am J Health Promot. 2008;23(1):18–26. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.061023137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Diez-Roux AV. Neighborhoods and health: where are we and were do neighborhoods and health: where are we and where do we go from here? Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2007;55(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.respe.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu S, Wang R, Zhao Y, et al. The relationship between self-rated health and objective health status: a population-based study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):320. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wheeler BW, Lovell R, Higgins SL, et al. Beyond greenspace: an ecological study of population general health and indicators of natural environment type and quality. Int J Health Geogr. 2015;14(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s12942-015-0009-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCracken DS, Allen DA, Gow AJ. Associations between urban greenspace and health-related quality of life in children. Preventive Med Reports. 2016;3:211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ward JS, Duncan JS, Jarden A, Stewart T. The impact of children’s exposure to greenspace on physical activity, cognitive development, emotional wellbeing, and ability to appraise risk. Health Place. 2016;40:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Markevych I, Thiering E, Fuertes E, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of the effects of residential greenness on blood pressure in 10-year old children: results from the GINIplus and LISAplus studies. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):4086. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 16 kb)