Abstract

Objective

Uterine leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is a rare and aggressive disease with poor outcome. Due to its rarity and conflict of data, investigation on finding prognostic factor is challenging. The aim of the study was to investigate the prognostic significance of preoperative 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) in uterine LMS.

Methods

This was a retrospective observational cohort study in 3 tertiary referral hospitals. We retrospectively evaluated data from patients with pathologically proven uterine LMS who underwent preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT scans at 3 institutions. The prognostic implication of PET/CT parameters and other clinico-pathological parameters on disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) was evaluated.

Results

Clinico-patholgical data were reviewed for 19 eligible patients. In the group overall, median DFS and OS were 12 and 20 months, respectively. As for the recurrence, large tumor size, and high tumor maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) were demonstrated as risk factors of recurrence. As for the OS, high tumor SUVmax was demonstrated as the unique risk factor. There were significant differences in tumor size, mitotic count, SUVmax, and DFS between patients with and without recurrence. Also, there were significant differences in tumor size, SUVmax, DFS, and OS between 2 subgroups stratified by cut-off SUVmax.

Conclusion

SUVmax at preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT was associated with worse outcome in patients with uterine LMS. In the preoperative setting, SUVmax can be a valuable non-invasive prognostic marker. Additionally, SUVmax can help identify highly aggressive uterine LMS and may help in adjusting standard treatment toward an individualized, risk-adapted treatment.

Keywords: Uterine Diseases, Leiomyosarcoma, Fluorodeoxyglucose F18, Positron Emission Tomography Computed Tomography, SUVmax, Prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Uterine sarcomas are a rare and heterogeneous group of mesenchymal tumors arising from the smooth muscles and connective tissue elements of the uterus that account for up to 5%–7% of all uterine corpus malignancies [1,2], and leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is the most common histological subtype [3,4]. LMS is characterized histologically as epithelial, myxoid, and rhabdoid, containing osteoclast-like giant cells which may account for variable clinical behavior [5]. Reported symptoms in patients with LMS are irregular bleeding and rapidly enlarging pelvic mass. Remission rates vary from 20% to 60% based upon the extent of disease at the time of primary resection [6,7].

To achieve optimal debulking of tumor, surgical resection including hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and additional surgery is necessary [6,8,9,10]. Generally, prognosis of uterine LMS is poor with 5-year overall survival (OS) rates of 25% [11,12], and 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) rate ranging from 75.8% to 15% stratified by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage [13,14], and an approximately 40% survival independent of stage [15]. Palliative systemic treatment can be considered in patients with advanced or locally recurrent disease, however, response rates are poor. Unlike other adult soft tissue sarcomas, there are separate National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for LMS issued by the Uterine Neoplasm panel, as it is believed that LMS originate in the uterus may be a distinct subgroup of tumors based on gene expression patterns [16].

Use of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) to image functional tumor metabolism has been popular in clinical oncology. Tumor FDG uptake as measured by the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) has proven useful in previous reports as a parameter for grading and describing behavior of sarcomas [17,18,19]. In studies examining patients with chondrosarcoma, liposarcoma, and synovial sarcoma, tumor SUVmax has correlated with tumor grade and disease progression [20,21,22]. However, may be due to the rarity of the tumor, few studies of uterine LMS have been performed, most with case reports.

In this retrospective study, we aimed to investigate the prognostic significance of preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with newly diagnosed, histologically confirmed uterine LMS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients

We retrospectively identified patients with biopsy-proven uterine LMS who underwent preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging at Asan Medical Center, Samsung Medical Center, and Seoul National University Hospital between January 2007 and March 2015. The diagnoses were established through preoperative endometrial biopsy and verified in hysterectomy specimens, and stage was assessed according to the FIGO 2009 criteria for surgical staging. Patients were required to have undergone both preoperative integrated 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging in the 2 weeks prior to surgery. Patients were excluded from analysis if they (1) were previously diagnosed with another malignant disease, (2) had a follow-up duration <4 months, or (3) received a primary treatment other than surgery, such as neoadjuvant chemotherapy or preoperative radiation. After surgery, all patients were clinically and radiologically followed up according to each institutions' clinical protocol. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board, and informed consent was waived due to its retrospective design.

Clinical characteristics and survival data were obtained from the patients' medical records and institutional tumor records. Tumor histology, grade, and size were obtained from the surgical pathology report.

2. PET/CT

Patients were examined using dedicated PET/CT scanners. Each patient was asked to fast for at least 4 hours prior to undergoing PET/CT. Diuretics were not used for preparation. Fasting blood sugar level was checked by the glucose oxidoperoxidase method using a commercially provided portable glucometer (Accu-Chek®; Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Approximately 0.14 mCi/kg body weight of FDG was administered intravenously 1 hour prior to imaging. After voiding, PET/CT images were acquired. CT was performed before PET; the resulting data were used to generate an attenuation correction map for PET, and the PET images were reconstructed. Each PET scan was acquired from skull base to proximal thigh in 3-dimensional row action maximum likelihood algorithm mode. A total of 7–9 bed positions were examined for PET acquisition, with 2.5 min/bed position.

3. Assessment of 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging

18F-FDG PET/CT data were transferred into the workstation, and intensity values (radioactivity concentration) were converted to SUVs. The SUVmax was then quantitatively used to determine 18F-FDG avidity. SUV was defined as the concentration of 18F-FDG divided by the injected dose, corrected for the body weight of the patient and radioactive decay at scanning time (SUV=activity concentration/[injected dose/body weight]).

4. Statistical analysis

The most discriminating threshold value allowing differentiation of the 2 groups of patients was selected using receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) methodology [23]. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated for each parameter using the nonparametric method representing the overall predictive or prognostic performance [24]. Kaplan-Meier estimates and the log-rank test were done to assess the equality of the survival functions across variables in the DFS and OS analysis. Both DFS and OS were analysed using time-to-event regression. OS was calculated from the date of operation to date of death. DFS was calculated from the date of operation to the date of documented recurrence. Recurrence of disease was defined as the development of tumor on physical examination and/or CT scan that was considered consistent with recurrent LMS. Abnormalities that were considered equivocal were further evaluated for confirmation that they represented recurrence: biopsy was recommended as ideal; however, additional or follow-up imaging was acceptable. If follow-up imaging confirmed that a suspicious finding was indeed a recurrence, then the date of recurrence was the date first documented.

Due to the limited number of patients available for this analysis, only univariate Cox regression models was used to assess the value of selected prognostic factors to predict outcome of LMS patients. The Cox proportional hazard model was used to evaluate prognostic variables, and an estimated hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was presented, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS software for Windows (version 19.0; IBM SPSS, Somers, NY, USA).

RESULTS

1. Patient demographics and tumor characteristics

Between January 2007 and March 2015, data from 19 patients were archived at 3 participating institutions. The median age of participants was 51 years (range, 38–76 years); and 2009 FIGO stage distribution was 42.1% stage I, 5.3% stage II and III, and 47.3% stage IV, as detailed in Table 1. The median size of the primary uterine tumor was 10 cm (range, 3.0–18.5 cm), and the median SUVmax was 14.0 (range, 2.9–54.6). The median follow-up for all patients was 20.0 months. Fourteen of 19 patients developed recurrent disease (73.7%), and 8 patients died of disease (42.1%). All 19 patients were considered evaluable for DFS and OS.

Table 1. Clinico-pathological characteristics of patients who underwent PET/CT before operation for uterine LMS (n=19).

| Characteristics | Patients | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 51 (38–76) | - | |

| DFS (mo) | 12 (4–61) | - | |

| OS (mo) | 20 (4-61) | - | |

| FIGO stage | |||

| I | 8 | 42.1 | |

| II | 1 | 5.3 | |

| III | 1 | 5.3 | |

| IV | 9 | 47.3 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 10.0 (3.0–18.5) | - | |

| SUVmax | 14.0 (2.9–54.6) | - | |

| Recurrence | 14 | 73.7 | |

| Mortality | 8 | 42.1 | |

Values are presented as median (range).

DFS, disease-free survival; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; LMS, leiomyosarcoma; OS, overall survival; PET/CT, positron emission tomography/computed tomography; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value.

2. Correlations between PET/CT and clinico-pathological parameters

In the current study, tumor SUVmax was correlated with higher FIGO stage (p=0.003; Pearson coefficient=0.644), tumor size (p=0.004; Pearson coefficient=0.622), and lymph node (LN) metastasis (p=0.024; Pearson coefficient=0.577).

3. Prediction of outcome

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the results of regression analyses of prognostic factors for PFS and OS in the current study. The ROC curve analyses demonstrated that the AUC for recurrence and survival were maximal when the threshold SUVmax was 23.95. The AUC for DFS at the cut-off SUVmax was 0.750 (p=0.105; 95% CI=0.517–0.983), and for OS was 0.722 (p=0.107; 95% CI=0.468–0.975).

Table 2. Analyses of prognostic factors for progression-free survival in patients with uterine LMS.

| Variables | Test for DFS | HR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | - | 1.020 | 0.960–1.084 | 0.515 |

| FIGO stage | III, IV vs. I, II | 2.072 | 0.695–6.175 | 0.191 |

| Tumor size | - | 1.206 | 1.049–1.385 | 0.008 |

| Deep myometrial invasion | Present vs. absent | 1.759 | 0.194–15.949 | 0.652 |

| LVSI | Present vs. absent | 1.597 | 0.478–5.334 | 0.446 |

| LN metastasis | Present vs. absent | 14.003 | 0.876–223.866 | 0.062 |

| Adnexal invasion | Present vs. absent | 1.330 | 0.292–6.055 | 0.712 |

| Mitotic count | - | 1.012 | 0.995–1.031 | 0.176 |

| SUVmax | - | 1.052 | 1.010–1.096 | 0.014 |

CI, confidence interval; DFS, disease-free survival; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; HR, hazard ratio; LMS, leiomyosarcoma; LN, lymph node; LVSI, lymphovascular space invasion; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value.

Table 3. Analyses of prognostic factors for OS in patients with uterine LMS.

| Variables | Test for OS | HR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | - | 0.981 | 0.894–1.077 | 0.691 |

| FIGO stage | III, IV vs. I, II | 4.049 | 0.797–20.564 | 0.092 |

| Tumor size | - | 1.134 | 0.972–1.323 | 0.111 |

| Deep myometrial invasion | Present vs. absent | 0.815 | 0.073–9.051 | 0.867 |

| LVSI | Present vs. absent | 1.235 | 0.275–5.537 | 0.783 |

| LN metastasis | Present vs. absent | 1,202,304.284 | 0.000–9,484,264 | 0.963 |

| Adnexal invasion | Present vs. absent | 1.502 | 0.174–12.971 | 0.712 |

| Mitotic count | - | 0.884 | 0.524–1.493 | 0.646 |

| SUVmax | - | 1.056 | 1.008–1.107 | 0.022 |

CI, confidence interval; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; HR, hazard ratio; LMS, leiomyosarcoma; LN, lymph node; LVSI, lymphovascular space invasion; OS, overall survival; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value.

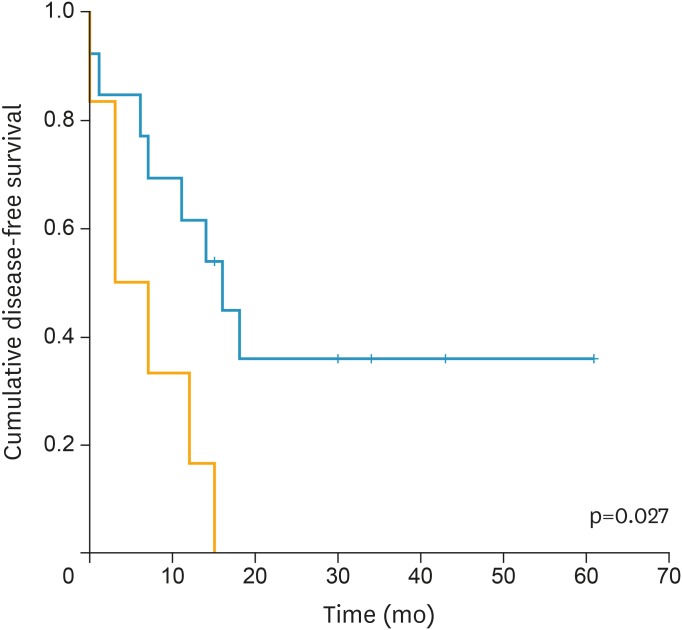

Large tumor size (p=0.008; HR=1.206; 95% CI=1.049–1.385), and high tumor SUVmax (p=0.014; HR=1.052; 95% CI=1.010–1.096) were demonstrated as risk factors of recurrence. Kaplan-Meier survival graphs in Fig. 1 depicts that DFS significantly differed in groups categorized based on SUVmax (p=0.027, log-rank test).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival graph shows significantly different DFS between the groups categorized by SUVmax above (orange line) and below (blue line) cut-off value (23.95) (p=0.027, log-rank test).

DFS, disease-free survival; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value.

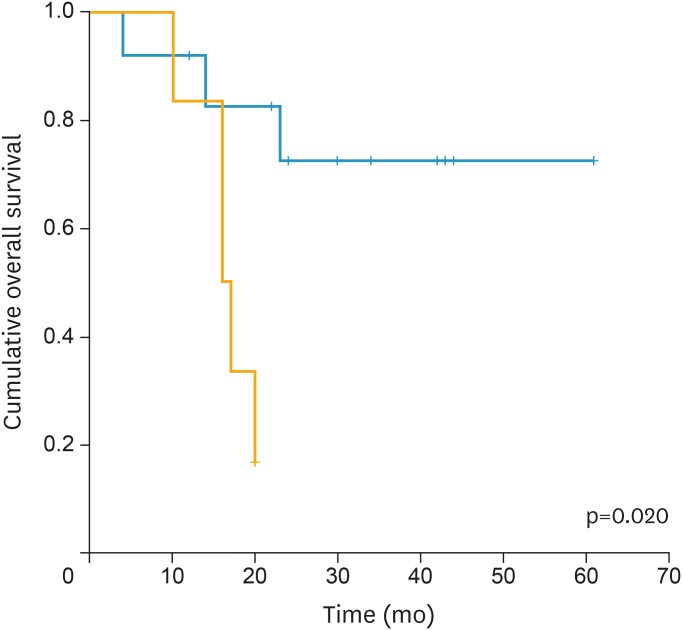

As for the OS high tumor SUVmax (p=0.022; HR=1.056; 95% CI=1.008–1.107) was demonstrated as the unique risk factor. Kaplan-Meier survival graphs in Fig. 2 shows that OS significantly differed in groups categorized by SUVmax (p=0.020, log-rank test).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival graph shows significantly different OS between the groups categorized by SUVmax above (orange line) and below (blue line) cut-off value (23.95) (p=0.020, log-rank test).

OS, overall survival; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value.

4. Differences between recurrent and non-recurrent groups

Table 4 summarizes the clinic-pathological and 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging-derived characteristics of patients without and with recurrence. There were significant differences in tumor size, mitotic count, SUVmax, and DFS between patients with and without recurrence.

Table 4. Clinico-pathological and PET/CT derived characteristics of patients without and with recurrence (n=19).

| Variables | Without recurrence (n=5) | With recurrence (n=14) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age (yr) | 49.200 | 4.868 | 52.786 | 10.613 | 0.331 |

| Tumor size | 5.600 | 2.434 | 12.250 | 3.615 | 0.001 |

| Mitotic count | 5.500 | 2.121 | 50.714 | 42.244 | 0.030 |

| SUVmax | 9.790 | 5.605 | 22.933 | 16.570 | 0.019 |

| DFS (mo) | 36.600 | 16.979 | 8.071 | 6.245 | 0.018 |

DFS, disease-free survival; PET/CT, positron emission tomography/computed tomography; SD, standard deviation; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value.

5. Differences between high and low groups categorized by SUVmax

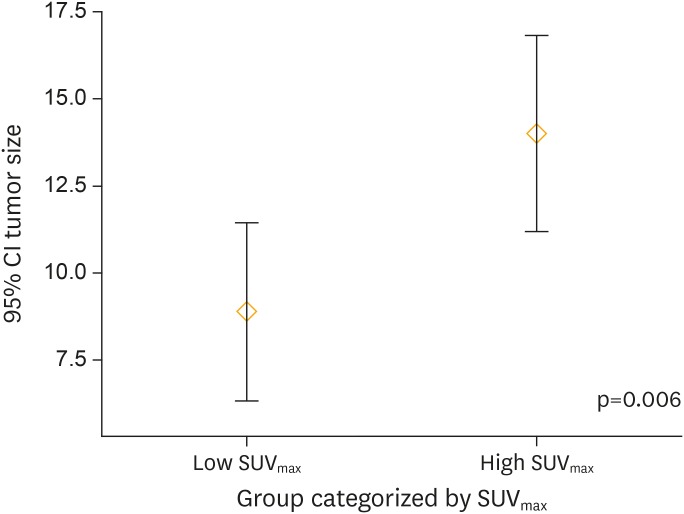

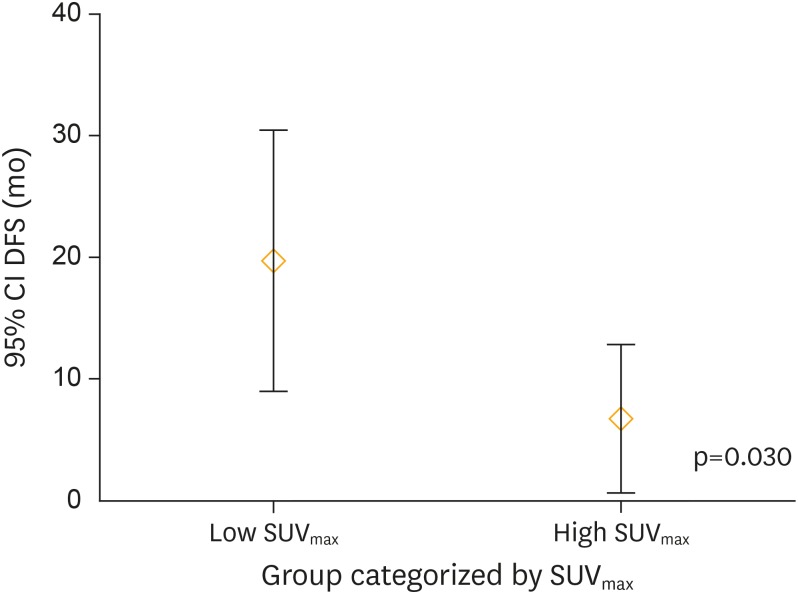

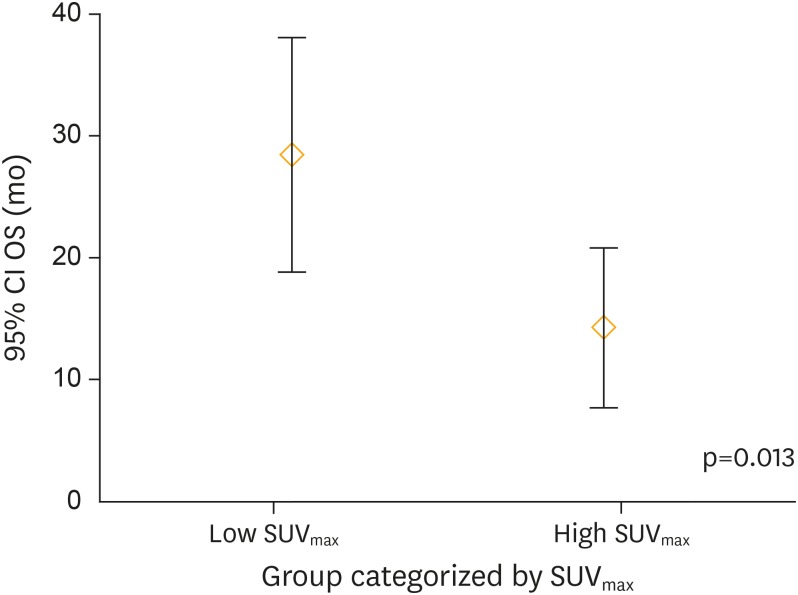

Table 5 summarizes the clinic-pathological and 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging-derived characteristics of patients stratified by cut-off SUVmax. Figs. 3-5 depict the distribution pattern of each parameters between high and low SUVmax groups.

Table 5. Clinico-pathological and PET/CT derived characteristics of 2 subgroups stratified by cut-off SUVmax (n=19).

| Variables | Low SUVmax (n=13) | High SUVmax (n=6) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age (yr) | 52.462 | 10.154 | 50.500 | 8.408 | 0.667 |

| Tumor size | 8.879 | 4.214 | 14.000 | 2.683 | 0.006 |

| Mitotic count | 36.571 | 36.414 | 55.000 | 73.539 | 0.784 |

| SUVmax | 10.293 | 4.791 | 39.367 | 10.822 | 0.001 |

| DFS (mo) | 19.692 | 17.778 | 6.667 | 5.820 | 0.030 |

| OS (mo) | 28.462 | 15.888 | 14.333 | 6.250 | 0.013 |

DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; PET/CT, positron emission tomography/computed tomography; SD, standard deviation; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value.

Fig. 3.

Tumor size distribution between patients categorized by SUVmax. There was significant difference (p=0.006) of tumor size distribution between patient groups categorized by SUVmax.

CI, confidence interval; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value.

Fig. 4.

DFS distribution between patients categorized by SUVmax. There was significant difference (p=0.030) of DFS distribution between patient groups categorized by SUVmax.

CI, confidence interval; DFS, disease-free survival; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value.

Fig. 5.

OS distribution between patients categorized by SUVmax. There was significant difference (p=0.013) of OS distribution between patient groups categorized by SUVmax.

CI, confidence interval; OS, overall survival; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we investigated in detail the clinical feasibility of preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with uterine LMS. We have shown that preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT provided valuable prognostic information in patients with uterine LMS. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigating the prognostic value of preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT in uterine LMS, focusing on the tumor SUVmax.

Our key finding was that SUVmax was the powerful prognostic factor of both DFS and OS. Taking into account the correlations seen between SUVmax and conventional prognostic variables (FIGO stage, tumor size, and LN metastasis), we performed regression analysis and were able to demonstrate that SUVmax was better predictor of outcome. However, due to the small number of enrolled patients, multivariate analysis could not be performed, and deserves further evaluation.

Outcome for those exhibiting SUVmax less than 23.95 was favorable and remarkably different from that of the poor-prognosis group. As described in the Results section, tumor SUVmax in this study was correlated with tumor size (p=0.004), higher FIGO stage (p=0.003), and LN metastasis (p=0.024). Current evidence suggests that tumor size and tumor metabolic activity are more important predictors of recurrence than previously known clinicopathological parameters in uterine LMS. Hence, preoperative information of tumor size and SUVmax may be utilized to triage patients with high risk of recurrence and poor prognosis. Considering that 18F-FDG PET/CT continues to be investigated as a non-invasive method to image and characterize tumors as well as potentially predict patient survival, current finding can be used in the future for patient stratification and evaluation of risk-adaptive treatment and surveillance strategies for uterine LMS. Due to the rare incidence of uterine LMS, further multi-institutional studies are recommended to confirm and validate the current finding.

Unfortunately, likely due to the rarity of the tumor, few studies of LMS have been performed, and the rarity of this disease makes evidence-based strategy of uterine LMS particularly challenging. Moreover, making a preoperative diagnosis of uterine LMS is usually very difficult. Endometrial cytology is not useful for diagnosing uterine LMS, as the tumor is usually located within the myometrium, and only 30% of uterine LMS are diagnosed by endometrial curettage [25]. Only patients with biopsy-proven LMS may undergo comprehensive workup including PET/CT, which is relatively a rare and difficult situation in clinical setting. Nevertheless, the principal finding of the current study was that SUVmax was the powerful prognostic factor of both DFS and OS, and SUVmax was better predictor of outcome than conventional prognostic factors. So, if the uterine mass is strongly suspected as having possibility of LMS, information on metabolic characteristics of the mass is critical and important especially in the pretreatment stage to decide the extent of surgical approach and to predict the prognosis. Here lies the clinical significance of preoperative PET/CT scanning in uterine LMS. However, to validate the results of the current study, additional large prospective studies are necessary to confirm the predictive value of preoperative PET/CT in clinical practice.

One of the advantages of the present study is its generalizability. Calculation of SUVmax was performed from data obtained independently at 3 institutions. In collecting clinic-pathological and PET/CT data, we allowed for heterogeneities resulting from different treatment policies and the variable experiences of nuclear medicine physicians. Despite these heterogeneities, the results of analysis demonstrated clinically acceptable performance. The most significant bias might be measurement error as there was no central review process.

There are several limitations to our study including the general rarity of uterine LMS and the small number of patients available for analysis. Due to the difficulty in pretreatment diagnosis, most patients received surgery under the impression of uterine leiomyoma, and pretreatment imaging workup was unavailable. Preoperative PET/CT was performed in patients with histologic confirmation or after suspicious findings at MRI scans. However, we believe findings of the current study warrant reporting with the potential for a larger multi-institutional study at a later time. Second, an important caveat to the interpretation of these data is their retrospective nature and the selection biases that are inherent in this context. PET/CT was not performed in every case before primary treatment. The application of PET/CT to only selected cases might cause bias and influence the study results. Additionally, most (89.5%) patients in this study population had stage I and IV disease, and this might influence on the survival analysis. Nevertheless, this report is noteworthy because it is the first study to show the prognostic value of preoperative SUVmax in patients with uterine LMS, and our findings suggest the need for further studies on metabolic parameters.

This study underlines the importance of multi-institutional collaboration in order to make meaningful progress in such rare tumour type. Moreover, current findings demonstrate the potential of future similar investigations to improve the outcomes of patients with this rare and aggressive disease. Our study results are promising and need to be confirmed in prospective large trial.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

- Conceptualization: C.H.H.

- Data curation: C.H.H.

- Formal analysis: L.H.J., L.J.J., M.S.H., K.S.Y., C.H.H.

- Investigation: C.H.H.

- Methodology: P.J.Y., L.J.W., C.H.H.

- Project administration: C.H.H.

- Resources: C.H.H.

- Supervision: C.G.J., C.H.H.

- Validation: P.J.Y., L.J.W., C.H.H.

- Visualization: C.H.H.

- Writing - original draft: P.J.Y., L.J.W., C.H.H.

- Writing - review & editing: P.J.Y., L.J.W., L.H.J., L.J.J., M.S.H., K.S.Y., C.G.J., C.H.H.

References

- 1.Toro JR, Travis LB, Wu HJ, Zhu K, Fletcher CD, Devesa SS. Incidence patterns of soft tissue sarcomas, regardless of primary site, in the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program, 1978-2001: an analysis of 26,758 cases. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2922–2930. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Angelo E, Prat J. Uterine sarcomas: a review. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abeler VM, Røyne O, Thoresen S, Danielsen HE, Nesland JM, Kristensen GB. Uterine sarcomas in Norway. A histopathological and prognostic survey of a total population from 1970 to 2000 including 419 patients. Histopathology. 2009;54:355–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amant F, Moerman P, Neven P, Timmerman D, Van Limbergen E, Vergote I. Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 2005;366:491–505. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yorulmaz G, Erdogan G, Pestereli HE, Savas B, Karaveli FS. Epithelioid leiomyosarcoma with rhabdoid features. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2007;119:557–560. doi: 10.1007/s00508-007-0822-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gadducci A, Cosio S, Romanini A, Genazzani AR. The management of patients with uterine sarcoma: a debated clinical challenge. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:129–142. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Major FJ, Blessing JA, Silverberg SG, Morrow CP, Creasman WT, Currie JL, et al. Prognostic factors in early-stage uterine sarcoma. A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 1993;71:1702–1709. doi: 10.1002/cncr.2820710440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zivanovic O, Leitao MM, Iasonos A, Jacks LM, Zhou Q, Abu-Rustum NR, et al. Stage-specific outcomes of patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma: a comparison of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics and American Joint Committee on cancer staging systems. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2066–2072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leitao MM, Jr, Zivanovic O, Chi DS, Hensley ML, O'Cearbhaill R, Soslow RA, et al. Surgical cytoreduction in patients with metastatic uterine leiomyosarcoma at the time of initial diagnosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:409–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hensley ML, Barrette BA, Baumann K, Gaffney D, Hamilton AL, Kim JW, et al. Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG) consensus review: uterine and ovarian leiomyosarcomas. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24:S61–S66. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giuntoli RL, 2nd, Metzinger DS, DiMarco CS, Cha SS, Sloan JA, Keeney GL, et al. Retrospective review of 208 patients with leiomyosarcoma of the uterus: prognostic indicators, surgical management, and adjuvant therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:460–469. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gadducci A, Landoni F, Sartori E, Zola P, Maggino T, Lissoni A, et al. Uterine leiomyosarcoma: analysis of treatment failures and survival. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;62:25–32. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapp DS, Shin JY, Chan JK. Prognostic factors and survival in 1396 patients with uterine leiomyosarcomas: emphasis on impact of lymphadenectomy and oophorectomy. Cancer. 2008;112:820–830. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siedhoff MT, Kim KH. Morcellation and myomas: balancing decisions around minimally invasive treatments for fibroids. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112:769–771. doi: 10.1002/jso.24010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks SE, Zhan M, Cote T, Baquet CR. Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis of 2677 cases of uterine sarcoma 1989-1999. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:204–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao UN, Finkelstein SD, Jones MW. Comparative immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of uterine and extrauterine leiomyosarcomas. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:1001–1009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eary JF, Conrad EU, Bruckner JD, Folpe A, Hunt KJ, Mankoff DA, et al. Quantitative [F-18]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in pretreatment and grading of sarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:1215–1220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eary JF, O'Sullivan F, Powitan Y, Chandhury KR, Vernon C, Bruckner JD, et al. Sarcoma tumor FDG uptake measured by PET and patient outcome: a retrospective analysis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29:1149–1154. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0859-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folpe AL, Lyles RH, Sprouse JT, Conrad EU, 3rd, Eary JF. (F-18) fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography as a predictor of pathologic grade and other prognostic variables in bone and soft tissue sarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1279–1287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brenner W, Conrad EU, Eary JF. FDG PET imaging for grading and prediction of outcome in chondrosarcoma patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:189–195. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brenner W, Eary JF, Hwang W, Vernon C, Conrad EU. Risk assessment in liposarcoma patients based on FDG PET imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:1290–1295. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0170-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lisle JW, Eary JF, O'Sullivan J, Conrad EU. Risk assessment based on FDG-PET imaging in patients with synovial sarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:1605–1611. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0647-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metz CE. Basic principles of ROC analysis. Semin Nucl Med. 1978;8:283–298. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(78)80014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz LB, Diamond MP, Schwartz PE. Leiomyosarcomas: clinical presentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:180–183. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(12)90910-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]