ABSTRACT

Antiretroviral-free HIV remission requires substantial reduction of the number of latently infected cells and enhanced immune control of viremia. Latency-reversing agents (LRAs) aim to eliminate latently infected cells by increasing the rate of reactivation of HIV transcription, which exposes these cells to killing by the immune system. As LRAs are explored in clinical trials, it becomes increasingly important to assess the effect of an increased HIV reactivation rate on the decline of latently infected cells and to estimate LRA efficacy in increasing virus reactivation. However, whether the extent of HIV reactivation is a good predictor of the rate of decline of the number of latently infected cells is dependent on a number of factors. Our modeling shows that the mechanisms of maintenance and clearance of the reservoir, the life span of cells with reactivated HIV, and other factors may significantly impact the relationship between measures of HIV reactivation and the decline in the number of latently infected cells. The usual measures of HIV reactivation are the increase in cell-associated HIV RNA (CA RNA) and/or plasma HIV RNA soon after administration. We analyze two recent studies where CA RNA was used to estimate the impact of two novel LRAs, panobinostat and romidepsin. Both drugs increased the CA RNA level 3- to 4-fold in clinical trials. However, cells with panobinostat-reactivated HIV appeared long-lived (half-life > 1 month), suggesting that the HIV reactivation rate increased by approximately 8%. With romidepsin, the life span of cells that reactivated HIV was short (2 days), suggesting that the HIV reactivation rate may have doubled under treatment.

IMPORTANCE Long-lived latently infected cells that persist on antiretroviral treatment (ART) are thought to be the source of viral rebound soon after ART interruption. The elimination of latently infected cells is an important step in achieving antiretroviral-free HIV remission. Latency-reversing agents (LRAs) aim to activate HIV expression in latently infected cells, which could lead to their death. Here, we discuss the possible impact of the LRAs on the reduction of the number of latently infected cells, depending on the mechanisms of their loss and self-renewal and on the life span of the cells that have HIV transcription activated by the LRAs.

KEYWORDS: latency, reactivation, human immunodeficiency virus

INTRODUCTION

Combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) suppresses plasma HIV RNA below the detection limit of laboratory assays and restores the immune systems of infected patients by preventing new rounds of productive infection. However, ART cannot eradicate the infection, and virus replication starts again within weeks of ART cessation (1, 2). Therefore, treatment is required to be lifelong, with possible long-term toxicities. The cause of viral rebound and the most important obstacle to a cure for HIV infection are unclear, but it is generally believed that virus persists, in part, as long-lived latently infected cells (3–5). Since latently infected cells do not produce virus, they are unaffected by the immune system and are unresponsive to ART (6).

The total number of latently infected cells capable of producing replication-competent virus is thought to be roughly 1 million (7), and the most recent estimate of the half-life of latently infected cells is approximately 4 years (4). If it takes 4 years for the number of latently infected cells to decrease by half under ART, and assuming exponential decay, it would take approximately 88 years for these latently infected cells to decay to half a cell, which can be taken as a rough estimate of the time for eradication under ART alone. This estimate could be somewhat reduced if the stochasticity of the process is taken into account (8). One modeling study (9) suggested that it would be enough to reduce the reservoir 10,000-fold in order to prevent reemergence after ART interruption in half of all patients. On the other hand, a recent investigation of rebound after ART interruption (2) suggested that a much smaller reduction (200- to 500-fold) would suffice to achieve this goal. Nevertheless, the time on ART necessary to prevent viral rebound would be between 56 years (for 10,000-fold reduction) and 35 years (for 250-fold reduction), which means that ART would still be lifelong in most infected subjects.

There has been recent interest in pharmaceutical agents that reverse HIV latency and initiate virus production from latently infected cells, facilitating elimination of these cells by immune-mediated mechanisms or viral cytolytic effects. Various latency-reversing agents (LRAs) have been investigated, including drugs that trigger the NF-κB activation pathway, such as prostratin (10) and bryostatin (11) analogues; BET inhibitors enhancing the binding of the viral Tat protein to the HIV TAR element (12); disulfiram (13, 14); and histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi), like valproic acid (15, 16), vorinostat (17, 18), panobinostat (19), and romidepsin (20), that act as epigenetic modifiers. The HDACi were the first compounds to enter clinical trials, given the extensive data on their toxicity from studies in individuals with malignancy. However, all clinical trials of HDACi have demonstrated no decline in the frequency of latently infected cells (15, 18–20).

An increase in plasma HIV RNA was seen with panobinostat (19), romidepsin (20), and disulfiram (14), although in the panobinostat trial (19) this was demonstrated by a nonquantitative assay. Changes in HIV transcription have been demonstrated in all trials by showing an increase in the level of cell-associated HIV RNA (CA RNA) in total and resting CD4+ T cells (21). Synthesis of unspliced (US) HIV RNA is the first step in virus transcription, and multiple subsequent steps, including splicing, cytoplasmic export, synthesis of the regulatory proteins tat and rev, maturation, and budding, are subsequently required for virion release (22), but US HIV RNA is a marker that HIV transcription has been initiated (18).

Our aim here was to analyze the implications of the observed increase in virus transcription and virion production (which we call HIV reactivation), measured as CA RNA and plasma HIV RNA, respectively, in these trials. Three effects of HDACi were of particular interest to us but difficult to measure directly: how many more latently infected cells initiated virus transcription per day following administration of the LRA (the extent of “shock”), how long the new HIV-transcribing cells lived (the extent of “kill” without stimulation of immune response), and, finally, what was the effect of this increased HIV reactivation rate on the overall number of latently infected cells. We attempted to deduce the answers to these questions mainly from measurements of the increased quantity of CA US HIV RNA per million cells (the quantity directly measured in clinical trials), which is an indicator of increased provirus transcription.

Since the quantities of CA US HIV RNA per cell can differ substantially, the observed increase can be the result of two different effects that cannot be differentiated: (i) more infected cells initiate HIV transcription every day and (ii) cells that initiate transcription produce more CA US HIV RNA.

In our model, we assume the first effect, i.e., that the cells that have initiated HIV transcription have similar distributions of viral RNA production rates (regardless of whether HIV transcription has been reactivated naturally or by LRA), so that the cell-associated unspliced HIV RNA level is proportional to the number of latently infected cells with reactivated HIV transcription that are present at any time. This number depends not only on the number of cells that initiate transcription every day (what we call the HIV reactivation rate), but also on the life span of these cells once they have reactivated HIV transcription. One previous study has attempted to model a “multistage delayed activation” pathway of latent cells following vorinostat treatment, allowing the cells to pass through various stages of activation (23). However, for the purposes of our analysis, we consider only a simplified “direct activation” model in which cells become activated and persist for variable periods.

We use the results of the panobinostat (19) and romidepsin (20) trials to illustrate the effect of the interplay of the HIV reactivation rate and death on the US HIV RNA level. For example, although the CA RNA tripled in the presence of panobinostat, our model suggests that the frequency of transcription activation in time increased by less than 10%, while the much larger increase in the number of cells with reactivated HIV was caused by their long life span.

Since the currently tested LRAs were given to patients over only short periods (up to 2 months) because of toxicity concerns, their short-term effects on the reservoir size may have been too small to detect in these studies. We also discuss how different mechanisms of clearance and maintenance of latently infected cells could influence their observed decay rate with the use of LRAs.

RESULTS

Impact of an increased HIV reactivation rate on decay of latently infected cells.

Here, we consider some mechanisms that may cause changes in the number of latently infected cells, i.e., cells with silent provirus. Each day, a proportion of these cells naturally initiate virus transcription, and when this occurs, we no longer consider them to be a part of the latent reservoir. Virus transcription is therefore one possible mechanism that can cause a decrease in the total number of latently infected cells, irrespective of the subsequent life span of these cells (as we do not explicitly consider the possibility of reversion to latency).

We assume that LRAs increase the probability that a latently infected cell will start virus transcription, thus increasing the HIV reactivation rate. This should then increase the rate at which the number of latently infected cells decreases.

The size of the latent reservoir is estimated by measuring the integrated HIV DNA (7) under ART, which includes both silent and virus-transcribing HIV DNA. However, the total integrated HIV DNA would decay at the same rate as the silent HIV DNA as long as the cells transcribing HIV are shorter lived than latently infected cells (equations 11 to 13 below).

Although all investigated LRAs showed increased virus transcription, no changes in the latent-reservoir size were detected after the use of LRA in vivo (14, 18–20) or in vitro (24). One reason could be the short time during which LRAs were given to ART patients (ranging from 8 weeks for panobinostat to 3 weeks for romidepsin and 3 days for disulfiram), making the detection of reservoir decay problematic. In addition, there are also effects unrelated to the duration of LRA exposure that are involved in the dynamics of the pool of latently infected cells. Here, we attempt to answer the following question: if LRA can raise the HIV reactivation rate, should we expect in principle to see faster decay of the latently infected cells, and if so, how much faster would it be? If, for example, the HIV reactivation rate tripled in the presence of LRAs, would latently infected cells decay 3 times faster?

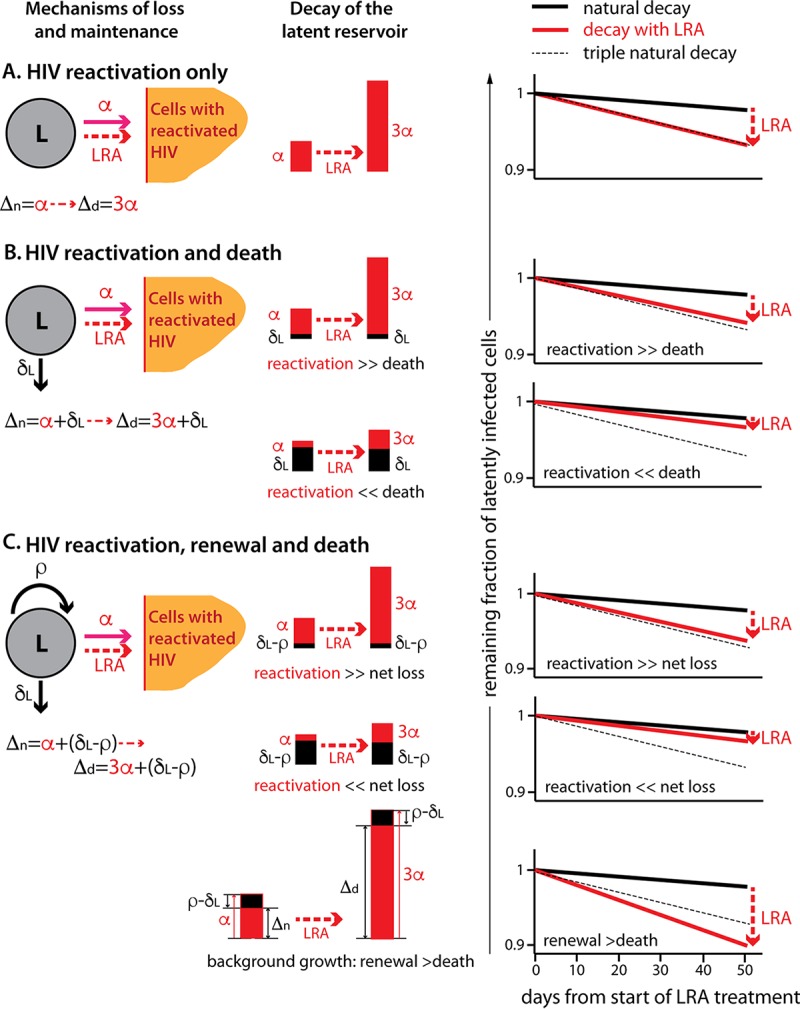

Actually, the fold increase in the HIV reactivation rate would be equal to the fold increase in the decay rate of latently infected cells only if gradual reactivation of HIV over time (in the absence of LRAs) is the only cause of their disappearance from the latent compartment. This situation is described by the simplest model of latent-pool decay (equations 1 and 2 below), in which latent cells can be removed only when they reactivate HIV transcription, thus leaving the latent compartment forever (and subsequently dying). In this case, the natural decay rate, Δn, of latently infected cells under ART is equal to the HIV reactivation rate, αn (Fig. 1A, left, mechanisms). In this case, if the HIV reactivation rate triples in the presence of an LRA (Fig. 1A, middle and right), then the decay of latently infected cells under drug treatment, Δd, will also exactly triple.

FIG 1.

Effects of underlying latent-reservoir dynamics. Depending on the mechanisms driving latent-cell decay under ART, we would see a different relationship between additional virus reactivation and the change in reservoir decay under LRAs. We do not know all the processes that occur in the reservoir, but we show the effects of three scenarios, schematically depicted on the left. (A) HIV reactivation is the only mechanism of loss of latently infected cells (activated cells are represented by a different symbol, because we did not follow them in the model). (B) Latently infected cells can reactivate HIV transcription or simply die without HIV reactivation. (C) Latently infected cells can reactivate HIV, die, and renew by division or new infections. L, latently infected cells; A, cells with reactivated HIV transcription; α, natural HIV reactivation rate (solid red arrow); 3α, 3-fold increase in the HIV reactivation rate in the presence of an LRA (dashed red arrow); δL, death rate of latently infected cells; ρ, renewal rate of the latent reservoir; Δn, natural decay rate of the latent reservoir; Δd, decay rate of the latent reservoir in the presence of an LRA. (Middle) The bars represent the decay rates of the reservoir under ART and with an LRA, with the contribution of HIV reactivation in red. (Right) Reservoir decay under LRA that triples the HIV reactivation rate (red line) compared to the natural decay (solid black line) and triple natural decay (dashed line).

Let us now assume that the natural attrition of the latent compartment is caused not only by HIV reactivation, α, but also by natural death, δL, of latently infected cells without HIV reactivation (Fig. 1B). We assume that only the HIV reactivation rate triples in the presence of the LRA without any effect on the natural death rate. If death plays only an insignificant role in the natural decay of latently infected cells (Fig. 1B, HIV reactivation ≫ death), then the tripling of the natural HIV reactivation rate will still cause an approximate tripling of the decay of latently infected cells. In Fig. 1B, top right, the red line, representing the actual decay of latently infected cells with LRAs, is only slightly above the dashed line, representing the triple natural decay.

If, on the other hand, latently infected cells decay mainly because they die naturally without HIV reactivation and HIV reactivation contributes only negligibly to the loss (Fig. 1B, HIV reactivation ≪ death), then tripling this low HIV reactivation rate will have almost no effect on the decay rate of latently infected cells. In this case, the actual decay rate of latently infected cells with LRAs (Fig. 1B, right, red line) is only slightly higher than the natural decay (solid black line) and is much lower than triple the natural decay rate (dashed line).

If the latent compartment declines because of HIV reactivation and death of latently infected cells but is also partially maintained by different self-renewal mechanisms, like homeostatic proliferation (25, 26) or infection of new cells (27), then its natural decay would be the sum of the HIV reactivation rate and the net loss due to the balance of the death and renewal rates (Fig. 1C). Again, if death and renewal nearly balance (Fig. 1C, HIV reactivation ≫ net loss), virus activation will be the main cause of the reservoir decline. In this case, if LRA triples the HIV reactivation rate, the decay rate of latently infected cells will also approximately triple.

If the death of latently infected cells is the dominant cause of decay and HIV reactivation and renewal make only small contributions (Fig. 1C, HIV reactivation ≪ net loss), then tripling the HIV reactivation rate will again have almost no effect on decay. In this case, we may be significantly overestimating the increase in the decay rate if we assume that it is equal to the increase in the HIV reactivation rate.

Finally, there is a case where the rate of natural HIV reactivation from latency may be higher than that of the observed decay of the latently infected cells. This would occur when the natural death rate of latently infected cells is lower than the renewal rate, so that the balance of renewal and death without natural HIV reactivation would result in “background growth.” Given that latently infected cells are declining overall, the rate of HIV reactivation from latency must be higher than this background growth rate. The observed decay rate of latently infected cells would then be equal to the difference between HIV reactivation and the background growth (Fig. 1C, bottom). In this case, the tripling of the HIV reactivation rate in the presence of LRA will more than triple the decay rate (Fig. 1C, bottom middle and left). This means that we could be underestimating the increase in the decay rate of the reservoir if we assume that it is equal to the increase in the HIV reactivation rate.

Reversion to latency would slow down the rate of decay of the latent reservoir, with an overall effect somewhat similar to that of additional latent-cell replication.

Interpreting the LRA-induced reactivation of HIV transcription.

We have shown above that even if the increase in the proportion of latent cells that start HIV transcription per day (referred to here as the HIV reactivation rate) under LRAs were precisely known, it is difficult to estimate its impact on the number of latent cells when some of the currently known mechanisms underlying the reservoir decay are taken into account. Here, we deal with the issue of how we estimate the increase in the HIV reactivation rate based on the current number of latently infected cells with reactivated HIV transcription. The increase in this number during LRA treatment is in practice measured indirectly, most often by the increase in CA US HIV RNA (14, 18–20). We show that the number of reactivated latent cells depends not only on the frequency in time at which the cells reactivate transcription, but also on the cell life span in the HIV-transcribing state.

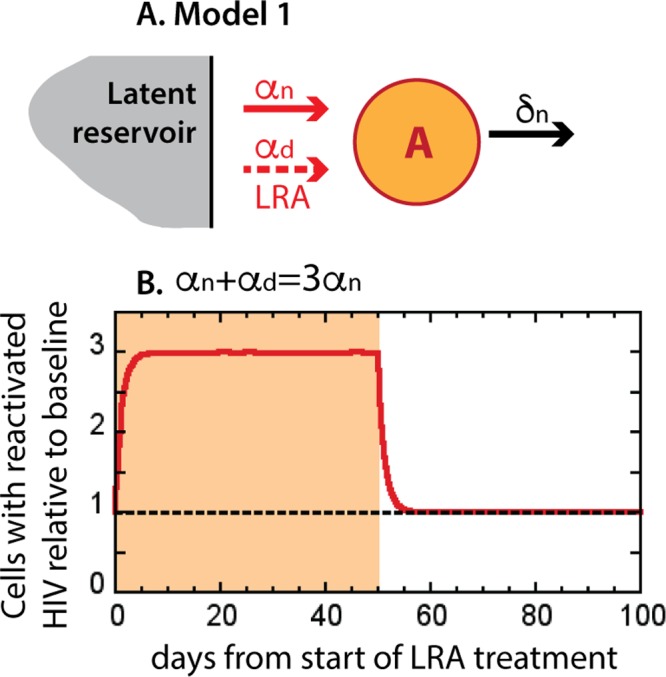

If we introduce an LRA after long-term ART, we assume that it will reactivate HIV transcription in additional latently infected cells and thus enhance the background HIV reactivation rate from αn to αn plus αd (Fig. 2A). Consequently, we will observe an increase in the number of cells with reactivated HIV from baseline (Fig. 2B, dashed line) to a higher level (Fig. 2B, red line). If the cells with LRA-reactivated HIV have the same half-life of 1 day (and therefore the same high death rate) as the cells with naturally reactivated HIV, the new level of HIV-transcribing cells will be reached within days (at the rate δn from equation 13), and the fold increase in the HIV reactivation rate will be approximately equal to the fold increase in the number of the cells with reactivated HIV during LRA treatment (Fig. 2B, shaded area). For example, an LRA may triple the natural HIV reactivation rate, so that αd plus αn is equal to 3αn or αd is equal to 2αn. Then, the net HIV reactivation rate will triple, and the steady-state level of cells transcribing HIV in the presence of LRA will approximately triple (equations 14 and 15).

FIG 2.

Simplest dynamics of infected cells with reactivated HIV transcription under ART and under LRAs. (A) Model 1. All cells with reactivated HIV (A) die at the same rate, δn, irrespective of whether virus was reactivated naturally (αn) or by an LRA (αd); here, the model does not follow the processes in the latent reservoir, and thus, a different symbol is used. (B) Virus-transcribing cells under ART (dashed line) and with an LRA (red line) when the LRA triples the natural HIV reactivation rate.

Impact of the life span of cells with reactivated virus transcription.

The behavior of the cells with reactivated HIV shown in Fig. 2B, in which the fold increase in the number of cells is approximately equal to the fold increase in the HIV reactivation rate, relies on the assumption that all cells with reactivated HIV are short-lived. However, recent studies (24, 28) have suggested that cells with HIV reactivated by HDACi may have longer life spans and that virus-specific CD8+ T cells or other immune responses may need to be stimulated in order to facilitate their elimination.

A scenario in which cells with LRA-reactivated HIV have a longer life span than cells with naturally reactivated HIV is schematically represented in Fig. 3A and described by equations 8 to 10. When we introduce an LRA in this more detailed model, it will again reactivate HIV transcription in additional latently infected cells and thus enhance the background HIV reactivation rate from αn to α, which is equal to αn plus αd. Consequently, we observe increased frequency of HIV-transcribing cells, Ad.

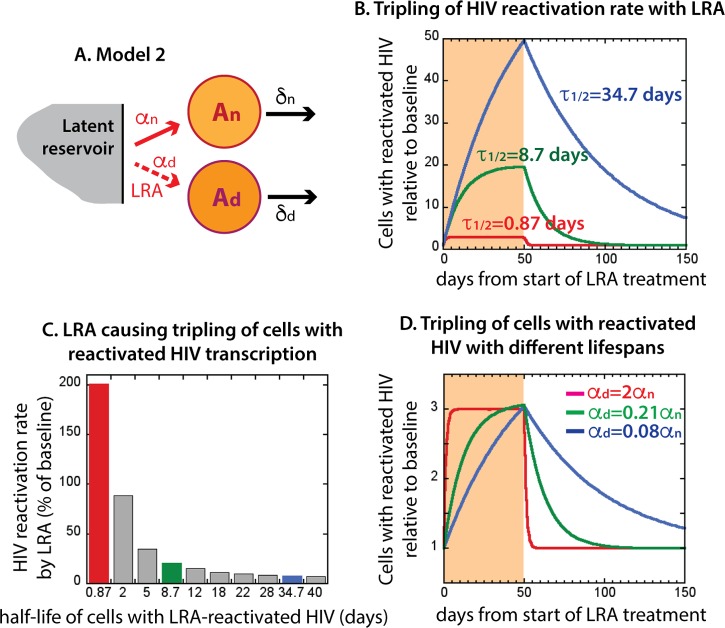

FIG 3.

Life span of cells after HIV reactivation by an LRA. Cells with HIV transcription reactivated by an LRA may live longer than cells with naturally reactivated virus. (A) Model 2, unlike model 1, has two types of HIV-transcribing cells: short-lived cells with naturally reactivated HIV, An, and potentially long-lived cells with LRA drug-reactivated HIV, Ad; again, the model does not depend on the processes within the latent reservoir. (B) Increase in the number of all virus-transcribing cells (relative to baseline with no LRA) when the half-life of the cells with LRA-reactivated HIV is 0.87 days (δd = 0.8 day−1; red line), 8.7 days (δd = 0.08 day−1; green line), or 34.7 days (δd = 0.02 day−1; blue line) and the LRA-induced HIV reactivation rate, αd, is 2αn, so that the total HIV reactivation rate, α, is 3αn. (C) LRA HIV reactivation rate (as a percentage of the natural virus activation rate) that would be necessary to measure a tripling of the number of HIV-transcribing cells over 50 days, depending on the half-life of the cells with LRA-reactivated virus (half-life: 0.87 days, red bar; 8.7 days, green bar; 34.5 days, blue bar). (D) Dynamics of tripling of HIV-transcribing cells with different life spans under LRA (half-life: 0.87 days, red line; 8.7 days, green line; 34.5 days, blue line).

We investigated the effect of the longer life span of cells with LRA-reactivated HIV on the total number of HIV-transcribing cells (Fig. 3B). We assumed that the cells with naturally reactivated HIV had a short half-life of 1 day and then investigated the effects of different life spans for cells with LRA-reactivated HIV. We assumed that LRA-induced HIV reactivation, αd, was twice the natural HIV reactivation rate (αd = 2αn), so that the total HIV reactivation rate of the latently infected cells (α = αn + αd = 3αn) is triple the natural HIV reactivation rate (equation 13).

In Fig. 3B, we show the results of continuous LRA administration over 50 days. As before, tripling of the HIV reactivation rate led to tripling of the number of HIV-transcribing cells when the cells with LRA-reactivated HIV were short-lived (the red line in Fig. 3B is equivalent to the red line in Fig. 2B). However, when the cells with LRA-reactivated HIV were 10 times longer lived than the cells with natural HIV reactivation, tripling the HIV reactivation rate resulted in an ∼20-fold increase in the number of HIV-transcribing cells (Fig. 3B, green line). If cells with LRA-reactivated HIV were 40 times longer lived, then the number of HIV-transcribing cells would increase 50-fold for the same tripling of the HIV reactivation rate (and would have increased even further if LRA were administered for a longer period). This occurs because, when the cells with reactivated HIV have a short life span, so that only the cells with recently reactivated virus are present at any time, their number is roughly proportional to the HIV reactivation rate. However, when the cells with reactivated HIV are longer lived, we see an accumulation of these cells over a long period, and their final number is much higher than the increase in the HIV reactivation rate. If, indeed, the cells with LRA-reactivated virus lived substantially longer than the cells with naturally reactivated HIV transcription, this would mean that we have to reassess our assumptions about the efficacy of some HDACi in reactivating HIV in latently infected cells.

We have shown above how, if an LRA triples the HIV reactivation rate, this may lead to up to a 50-fold increase in the number of HIV-transcribing cells when they are long-lived. However, in the studies of LRAs, it is the amount of reactivated virus that is measured, not the reactivation rate itself. The next question is, given an observed change in the amount of reactivated virus, how much would the HIV reactivation rate need to change for different life spans of the reactivated cells? Figure 3C shows that the LRA-induced HIV reactivation rate needed for tripling of the baseline number of cells transcribing HIV decreased sharply when these cells were progressively longer lived. For short-lived LRA-reactivated cells, we obtained tripling of their number with tripling of the HIV reactivation rate (Fig. 3C, red bar), but for the 40 times longer-lived LRA-reactivated cells, the same result was achieved with only 8% increase in the virus activation rate (Fig. 3C, blue bar).

The dynamics of increase in the number of cells with reactivated HIV that led to their tripling after 50 days of continuous LRA administration are shown in Fig. 3D for different cell life spans. When these cells turn over rapidly (red line), they reach the maximum level very fast (within a few days), but when they are longer lived (green and blue lines), this level builds up more slowly over time. When LRA is removed from the system, the cells with LRA-activated virus decay toward baseline at a rate equal to their death rate. Therefore, the most obvious signature of a longer life span of the cells with virus reactivated by LRA is slower decay toward baseline when the drug is removed.

This model allows us to roughly estimate the life span of the cells with reactivated virus and the actual increase in the virus activation rate for HDACi used as LRAs.

Implications of the model for interpreting clinical trial data.

A recent clinical trial of the drug panobinostat (19) showed CA RNA increased 3-fold in the presence of the drug. The drug completely disappeared from plasma within less than a week after the last administration, and the levels of histone acetylation also normalized quickly, but the cell-associated HIV RNA dropped only halfway to baseline in a month after the drug's disappearance. One interpretation of this result is that the cells that reactivated HIV transcription in the presence of the drug persisted once the drug was removed (and acetylation normalized) because they died slowly. In this case, the half-life of the cells with HIV reactivated by panobinostat would be at least 30 days (as roughly estimated from Fig. 1A in reference 19), the approximate time after which CA US HIV RNA drops to half of the above-mentioned baseline level at the last dose, and the observed 3-fold increase in cell-associated HIV RNA with panobinostat would be the result of only around 8% increase in the HIV reactivation rate. Another possibility is that the cells with reactivated HIV are dividing, in addition to dying at a natural rate. We did not consider this possibility, because we assumed that virus transcription would lead to cell cycle arrest (29, 30).

Romidepsin is the most potent LRA evaluated to date. Although during administration CA HIV RNA reaches on average 4 times the baseline level, which is only a small change compared to panobinostat (19) and vorinostat (18) when the uncertainties are taken into account, the dynamics of decay after the last dose are quite different from those of the other two HDACi. The drug half-life in plasma is only several hours (31). After the last dose, CA RNA decays quite quickly, with a half-life of approximately 2 days (estimated as the time in which CA US RNA drops from the peak after the last dose halfway to baseline in Fig. 2B in reference 20), while acetylation, interestingly, persists for longer (half-life, ∼5 days). The observed slow disappearance of acetylation is probably the effect from uninfected cells. We assume that the decay of the CA RNA reflects the death of the cells with the reactivated virus. The rise in CA HIV RNA after administration of romidepsin is accompanied by a rise in plasma virus, suggesting that HIV transcription needs to be followed by viral production for the infected cells to be killed.

The high death rate of the cells with reactivated HIV, with a 4-fold increase in their number, suggests that the HIV reactivation rate increased 2.5 times. However, how much this considerable increase would translate into a reduction of the number of the latently infected cells depends on the mechanisms involved in the maintenance and clearance of the latent reservoir, as discussed above.

It should be noted that the conclusions about the increase in the HIV reactivation rate under LRAs hold even if we include reversion to latency in the model (equations 17 to 19). In this case, cells with LRA-reactivated HIV decay because they either return to latency or die, so that their observed decay rate is the sum of the death rate and the rate of reversion to latency. While they may be even longer lived than observed, it is their life span in the HIV-transcribing state that determines the increase in CA HIV RNA caused by the increase in the HIV reactivation rate.

DISCUSSION

Several classes of drugs have been identified as having the capacity to increase HIV transcription and/or virus production in latently infected cells and are planned to be or are currently being tested in clinical trials for their latency-reversing effects (32). As the results of these trials become available, it is important to interpret them correctly and to understand their implications. The aim of these trials is to ascertain whether the drugs indeed increase virus transcription in patients on ART with undetectable viral loads (as proof of concept). This was measured by the increase in CA US HIV RNA in total and resting CD4+ T cells relative to baseline. In addition, plasma HIV RNA was commonly quantified to determine if increased transcription was followed by increased plasma virus. Cell-associated HIV DNA, or alternative measures of the reservoir, were determined to establish if there was any decay of the latently infected cells during the period of LRA treatment and follow-up.

On average, a 2- to 4-fold increase in CA US HIV RNA was observed in clinical trials of the HDACi vorinostat (18), panobinostat (19), and romidepsin (20) and with the anti-alcoholism drug disulfiram (14), which verified that these drugs can increase viral transcription under ART. With romidepsin, the increase in transcription was associated with an increase in plasma HIV RNA quantifiable by standard clinical assays, indicating that production of virions followed increased viral transcription. However, no significant changes in the reservoir of integrated or total HIV DNA were detected in any of these trials.

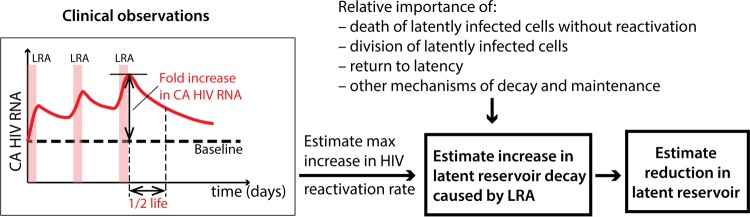

We developed simple models in order to (i) understand why we may not observe a reduction in integrated HIV DNA even when reactivation of virus transcription and production increase several times above baseline and (ii) show that a very small increase in the frequency of HIV reactivation events can lead to a much larger increase in the CA US HIV RNA when the cells with reactivated virus are long-lived. The steps to estimate the increase of latent-reservoir decay caused by LRAs, starting from a measured increase in the CA HIV RNA level, are summarized in Fig. 4. From the maximum increase of CA HIV RNA under LRAs and its half-life after LRA removal, one can estimate the increased HIV reactivation rate. An increased HIV reactivation rate is only one of the mechanisms that govern the latent-reservoir decay, and the change in this overall decay strongly depends on the relative importance of all the other mechanisms.

FIG 4.

Steps from measuring the increase in CA HIV RNA under LRA treatment to estimating the reduction of the latent HIV reservoir. LRAs increase the rate of reactivation of HIV transcription in latently infected cells. By measuring the maximal fold increase in the quantity of CA HIV RNA in blood under LRA treatment and the rate of decay after LRA treatment is stopped, one can estimate the greatest possible increase in the HIV reactivation rate. HIV reactivation is only one of a number of mechanisms of loss and renewal that regulate the number of cells latently infected by HIV in patients on ART. Other factors involved in the maintenance of the latent reservoir can also significantly affect our estimates of reservoir reduction. The final reduction of the latent reservoir caused by increasing HIV reactivation can be estimated only when the relative contributions of these mechanisms are better understood.

We showed that increasing HIV reactivation would considerably accelerate decay if the reservoir decays mostly because HIV in latently infected cells reactivates and the cells then die. However, if, for example, most latently infected cells simply die by apoptosis before reactivating virus and only a small proportion die from reactivating virus transcription or production, then increasing this small proportion would have a negligible effect on reservoir decay. Indeed, there is some in vitro (33) and in vivo (2) evidence that reactivation from latency may not be the dominant cause of reservoir decline. If in addition a proportion of the cells with LRA-reactivated virus do not die when the drug is removed but slowly return to a latently infected state, then the effect of virus reactivation on reduction of the reservoir will be even smaller. The range of possible outcomes for the reservoir decay becomes even larger as other mechanisms, such as replication of latently infected cells, are taken into account. We considered only a limited number of potential factors, since our aim was to show how, by taking them into account, one could come to very different conclusions about the effects of LRAs on the latent reservoir. Other mechanisms, such as a return to latency or new infections under ART, would probably significantly reduce the impact of LRAs, leading to more different outcomes, and are worth exploring in the future.

While panobinostat and romidepsin caused similar increases in patients' CA HIV RNA, the life spans of cells with reactivated HIV (as judged by the decay of CA HIV RNA after cessation of LRA treatment [19, 20]) differed by a factor of about 15: approximately 30 days for panobinostat and 2 days for romidepsin. Recent in vitro experiments also suggest that cells with virus transcription reactivated by vorinostat and panobinostat may be longer lived than cells that reactivate virus naturally (24, 28). Consequently, our model predicted that the potentials of these drugs to reactivate virus in latently infected cells are very different (around 8% above the baseline reservoir HIV reactivation rate for panobinostat and approximately 2.5-fold increase for romidepsin).

An interesting question is why cells with reactivated HIV are so much longer lived under panobinostat (and vorinostat) than under romidepsin. Another difference between romidepsin and the other HDACi was that romidepsin was the only HDACi that also caused bursts of plasma HIV RNA following the peaks in CA US HIV RNA, indicating that virus transcription was followed by production of virions (20). We thus speculate that initiating viral transcription may not be enough but that virus production may likely be a necessary first step to initiate viral cytopathic effects or immune recognition and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) killing of infected cells.

One unexplained result in some patients who underwent vorinostat or panobinostat treatment was an increase in CA HIV RNA in follow-up weeks postdosing. One possible explanation could be that the relaxed histone conformation in a portion of infected cells was different after deacetylation from the conformation before the HDACi administration, leaving the integrated HIV genome more exposed to transcription. Indeed, persistent changes in host gene expression were observed following vorinostat treatment (18). This could result in an increased proportion of cells with integrated provirus naturally initiating virus transcription after deacetylation. Modeling of the effects of vorinostat on CA US RNA levels has suggested a complex multistage delayed activation model can be used to describe HIV reactivation from latency under vorinostat treatment (23). Fitting of a future stochastic model with an increased probability of HIV reactivation in a proportion of latently infected cells following panobinostat treatment could give a lower estimate of the half-life of the cells transcribing HIV.

A way to achieve the ultimate goal of decreasing the size of the HIV reservoir in patients on ART may be the search for more potent LRA combinations that can reactivate virus transcription or production in a larger proportion of latently infected cells or a search for less toxic LRAs, preferably specific for HIV-infected cells, that can be given continuously with ART. However, characterizing the fate of cells with virus reactivated by LRAs is a key challenge for the field: do they ultimately die, or do they return to latency when the drug is removed? Under which conditions does virus reactivation result in elimination of infected cells? The other challenge is identifying all the effects of these drugs in the context of HIV (32). New tools that detect the frequency of HIV RNA-producing cells could, for example, clarify if they facilitate expansion of infected cells (34). Above all, we need a better understanding of the mechanisms of maintenance and decay of the reservoir and the role that activation plays in the decay in order to decide if virus reactivation is the best approach or if interventions that, for example, enhance cellular apoptosis in infected cells (35) would yield better results.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Models. (i) Models of reservoir decay (decay of cells with silent viral DNA).

We define L as latently infected cells, i.e., cells with integrated HIV DNA that do not transcribe or produce virus, and A as cells with reactivated HIV transcription and increase in CA RNA (which may or may not be associated with viral protein production and increase in plasma virus). When the latently infected cells enter the transcription phase, they move from the latent-cell compartment, L, to the compartment, A, with reactivated HIV. The rate at which this process occurs is the HIV reactivation rate, α. Basically, the HIV reactivation rate here is the proportion of latently infected cells that start HIV transcription per day, and it is proportional to the frequency of virus reactivation events in time. If reactivation of HIV transcription were the only process by which cells could leave the latent-cell compartment, then the change in the number of latently infected cells over time t would be described by the following equation:

| (1) |

Latently infected cells in this case would decay exponentially from their initial level (L0), with the decay rate equal to the HIV reactivation rate:

| (2) |

This decay is caused simply by HIV reactivation, because the cells with reactivated HIV transcription are no longer counted as latently infected, and it is not affected by the cell life span once the cells enter the transcription phase.

A more general description of the dynamics of the latently infected cells under ART would take into account the total HIV reactivation rate, α (which may be the sum of natural and LRA-induced transcription); the death rate of latently infected cells without HIV transcription, δL; and the renewal rate of the latent reservoir, ρ, for example, by homeostatic replication. In order to describe this more general scenario, we should replace equation 1 for the reservoir dynamics under ART with the following equation:

| (3) |

In this case, latently infected cells would decay at the rate α + δL – ρ:

| (4) |

Again, the life span of the cells in the compartment, A, with reactivated HIV transcription or production has no influence on the number of latently infected cells, L, in our simple model. This would not be true if we considered a more complex model in which the surviving cells with reactivated HIV could revert to latency. We briefly address a model with reversion to latency below.

In Fig. 1, the parameters were chosen so that the total decay of latently infected cells under ART in the absence of LRAs (solid black line) was 4.5 × 10−4 per day, resulting in a half-life of approximately 4 years.

(ii) Modeling cells with reactivated HIV transcription.

In Materials and Methods below, we consider only the changes in the number of latently infected cells. Here, we focus on the changes in the number of cells that have reactivated HIV transcription and/or production. This number is influenced by how many latently infected cells initiate HIV transcription per day and by the subsequent life span of these cells (i.e., by the rate at which they die).

(a) HIV reactivation under ART without LRAs.

In order to better understand the relationship between the increase in the number of cells that transcribe virus that are present at any time (as measured, for example, by CA HIV RNA) and the increase in the frequency of HIV reactivation events, we start from the simplest model of HIV reactivation under ART in the absence of an LRA. The cells with reactivated HIV transcription () are generated from the latently infected cells, L*, at the natural HIV reactivation rate, αn, and become short-lived viral RNA-producing cells that die at the rate δn:

| (5) |

where L* decays at the natural decay rate of the latently infected cells, Δn, possibly described as Δn = αn + δL − ρ,

| (6) |

The estimate for the half-life of virus-producing cells is around 1 day (36, 37), which would translate into a death rate of 0.8 per day. We use this value for the death rate, δn, of the cells with naturally reactivated HIV in all modeling. Similar assumptions were used in other models of HIV reactivation from latency (38).

If the cells with naturally activated virus die faster than latently infected cells decay (δn ≫ Δn), the long-term solution of equation 5 is as follows:

| (7) |

We use this expression as the baseline number of HIV-transcribing cells during ART before the start of LRA treatment (Fig. 2 and 3). Note that this number increases as the natural HIV reactivation rate, αn, and the life span of the cells with reactivated HIV (1/δn) increase.

(b) Cells transcribing HIV under LRAs.

When we introduce the LRA (at t = 0), HIV transcription in latently infected cells, L, is reactivated by the drug at the LRA-induced HIV reactivation rate, αd, in addition to the natural HIV reactivation. In addition to the cells with naturally reactivated HIV transcription, An, this creates cells with drug-reactivated HIV transcription, Ad, which die at the death rate δd (not necessarily equal to the death rate, δn, of the cells with naturally reactivated HIV):

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

Latently infected cells now decay at the higher rate Δn + αd,

| (11) |

At the beginning of the LRA treatment, the cells with naturally reactivated HIV start at the baseline given by equation 7 but rapidly (after ∼1/δn) reach the new steady state, An:

| (12) |

The cells with HIV reactivated by the drug approach their steady-state numbers at a rate equal to their death rate, δd:

| (13) |

The fold increase in the number of infected cells with reactivated HIV compared to baseline, f, is then as follows:

| (14) |

We assume that latently infected cells decay much more slowly than cells with reactivated HIV transcription die. Specifically, we assume that the decay of latently infected cells is much slower than the death rate of the cells with activated HIV transcription (Δn, Δn + αd ≪ δn, δd). Approximating Δn ≈ Δn + αd ≈ 0 means treating latently infected cells as a constant (L = L0) during the LRA treatment period (and is consistent, with no observed HIV DNA decay). In this approximation (used to plot Fig. 2 and 3), the steady states of cells with naturally activated virus, An ≈ αnL0/δn, are the same before and during LRA treatment, and the fold increase in infected cells with reactivated HIV with LRA is given by the following equation:

| (15) |

Equations 14 and 15 also describe the increase in CA HIV RNA, provided that virus-transcribing infected cells contain the same average level of CA HIV RNA whether they have HIV reactivated naturally or by an LRA. If the latently infected cells with HIV reactivated by an LRA contain on average fewer or more HIV RNA copies per cell, then Ad(t) in equation 14 needs to be multiplied by a scaling factor.

Decay of the integrated viral DNA.

The final aim of eradication strategies is to eliminate total intact integrated viral DNA. The measurement of integrated viral DNA does not differentiate between transcriptionally silent DNA and DNA with initiated transcription. Therefore, the number of cells with viable viral DNA (D) is proportional to the sum of the numbers of latent cells and cells with activated virus transcription (both naturally and by LRAs). Without the LRA, the natural decay of the replication-competent integrated viral DNA (7) would be the same as the natural decay of the latently infected cells. Using the model in equation 4, it would be as follows: Δn = αn + δn – ρ. After the administration of LRA at t = 0, there is an additional, drug-induced HIV reactivation rate, αd, and additional cells with drug-reactivated HIV, so that L(t), An(t), and Ad(t) are given by equation 11, equation 12, and equation 13, respectively, and the total number of cells with integrated viral DNA is the sum of the three,

| (16) |

This number decays at the lowest rate in equations 11 to 13. Therefore, the decay of the total integrated DNA is equal to the decay of the latently infected cells if the cells with reactivated HIV die faster than the decay of latently infected cells (δd > Δn + αd).

Reversion to latency.

If the cells with reactivated HIV not only die, but also return to latency at rate λ, the model with natural and drug-induced HIV reactivation can be described by the following differential equations:

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

Latently infected cells and cells with reactivated HIV under LRAs (reactivated both naturally and by LRAs) would in the long term decay at a rate lower than Δn + αd (with the correction dependent on all the other parameters, increasing monotonically with λn and λd). When the LRA is removed (αd = 0 in equations 17 to 19), cells with HIV reactivated by LRAs decay at a rate equal to the sum of the death rate and the rate of reversion to latency (δd + λd).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NHMRC (Australia) grants APP1025567 and APP1052979. M.P.D. and S.J.K. are NHMRC research fellows. S.R.L. is an NHMRC practitioner fellow. S.R.L. is supported by the National Institutes of Health Delaney AIDS Research Enterprise (DARE) to Find a Cure collaboratory (U19 AI096109 and 12047955) and the American Foundation for AIDS Research (109226-58-RGRL).

We thank Mykola Pinkevych for careful reading of the manuscript and useful suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chun T-W, Davey RT Jr, Engel D, Lane HC, Fauci AS. 1999. Re-emergence of HIV after stopping therapy. Nature 401:874–875. doi: 10.1038/44755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinkevych M, Cromer D, Tolstrup M, Grimm AJ, Cooper DA, Lewin SR, Sogaard OS, Rasmussen TA, Kent SJ, Kelleher AD, Davenport MP. 2015. HIV reactivation from latency after treatment interruption occurs on average every 5-8 days-implications for HIV remission. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005000. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chun TW, Fauci AS. 1999. Latent reservoirs of HIV: obstacles to the eradication of virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:10958–10961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.10958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siliciano JD, Kajdas J, Finzi D, Quinn TC, Chadwick K, Margolick JB, Kovacs C, Gange SJ, Siliciano RF. 2003. Long-term follow-up studies confirm the stability of the latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells. Nat Med 9:727–728. doi: 10.1038/nm880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katlama C, Deeks SG, Autran B, Martinez-Picado J, van Lunzen J, Rouzioux C, Miller C, Vella S, Schmitz JE, Ahlers J, Richman DD, Sékaly R-P. 2013. Barriers to a cure for HIV: new ways to target and eradicate HIV-1 reservoirs. Lancet 381:2109–2117. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60104-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finzi D, Blankson J, Siliciano JD, Margolick JB, Chadwick K, Pierson T, Smith K, Lisziewicz J, Lori F, Flexner C, Quinn TC, Chaisson RE, Rosenberg E, Walker B, Gange S, Gallant J, Siliciano RF. 1999. Latent infection of CD4+ T cells provides a mechanism for lifelong persistence of HIV-1, even in patients on effective combination therapy. Nat Med 5:512–517. doi: 10.1038/8394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chun TW, Carruth L, Finzi D, Shen X, DiGiuseppe JA, Taylor H, Hermankova M, Chadwick K, Margolick J, Quinn TC, Kuo YH, Brookmeyer R, Zeiger MA, Barditch-Crovo P, Siliciano RF. 1997. Quantification of latent tissue reservoirs and total body viral load in HIV-1 infection. Nature 387:183–188. doi: 10.1038/387183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conway JM, Coombs D. 2011. A stochastic model of latently infected cell reactivation and viral blip generation in treated HIV patients. PLoS Comput Biol 7:e1002033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill AL, Rosenbloom DIS, Fu F, Nowak MA, Siliciano RF. 2014. Predicting the outcomes of treatment to eradicate the latent reservoir for HIV-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:13475–13480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406663111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beans EJ, Fournogerakis D, Gauntlett C, Heumann LV, Kramer R, Marsden MD, Murray D, Chun T-W, Zack JA, Wender PA. 2013. Highly potent, synthetically accessible prostratin analogs induce latent HIV expression in vitro and ex vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:11698–11703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302634110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeChristopher BA, Loy BA, Marsden MD, Schrier AJ, Zack JA, Wender PA. 2012. Designed, synthetically accessible bryostatin analogues potently induce activation of latent HIV reservoirs in vitro. Nat Chem 4:705–710. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boehm D, Calvanese V, Dar RD, Xing S, Schroeder S, Martins L, Aull K, Li P-C, Planelles V, Bradner JE, Zhou M-M, Siliciano RF, Weinberger L, Verdin E, Ott M. 2013. BET bromodomain-targeting compounds reactivate HIV from latency via a Tat-independent mechanism. Cell Cycle 12:452–462. doi: 10.4161/cc.23309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spivak AM, Andrade A, Eisele E, Hoh R, Bacchetti P, Bumpus NN, Emad F, Buckheit R, McCance-Katz EF, Lai J, Kennedy M, Chander G, Siliciano RF, Siliciano JD, Deeks SG. 2014. A pilot study assessing the safety and latency-reversing activity of disulfiram in HIV-1-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 58:883–890. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elliott JH, McMahon JH, Chang CC, Lee SA, Hartogensis W, Bumpus N, Savic R, Roney J, Hoh R, Solomon A, Piatak M, Gorelick RJ, Lifson J, Bacchetti P, Deeks SG, Lewin SR. 2015. Short-term administration of disulfiram for reversal of latent HIV infection: a phase 2 dose-escalation study. Lancet HIV 2:e520–. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00226-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shehu-Xhilaga M, Rhodes D, Wightman F, Liu HB, Solomon A, Saleh S, Dear AE, Cameron PU, Lewin SR. 2009. The novel histone deacetylase inhibitors metacept-1 and metacept-3 potently increase HIV-1 transcription in latently infected cells. AIDS 23:2047–2050. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328330342c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehrman G, Hogue IB, Palmer S, Jennings C, Spina CA, Wiegand A, Landay AL, Coombs RW, Richman DD, Mellors JW, Coffin JM, Bosch RJ, Margolis DM. 2005. Depletion of latent HIV-1 infection in vivo: a proof-of-concept study. Lancet 366:549–555. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67098-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Archin NM, Liberty AL, Kashuba AD, Choudhary SK, Kuruc JD, Crooks AM, Parker DC, Anderson EM, Kearney MF, Strain MC, Richman DD, Hudgens MG, Bosch RJ, Coffin JM, Eron JJ, Hazuda DJ, Margolis DM. 2012. Administration of vorinostat disrupts HIV-1 latency in patients on antiretroviral therapy. Nature 487:482–485. doi: 10.1038/nature11286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elliott JH, Wightman F, Solomon A, Ghneim K, Ahlers J, Cameron MJ, Smith MZ, Spelman T, McMahon J, Velayudham P, Brown G, Roney J, Watson J, Prince MH, Hoy JF, Chomont N, Fromentin R, Procopio FA, Zeidan J, Palmer S, Odevall L, Johnstone RW, Martin BP, Sinclair E, Deeks SG, Hazuda DJ, Cameron PU, Sékaly R-P, Lewin SR. 2014. Activation of HIV transcription with short-course vorinostat in HIV-infected patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004473. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasmussen TA, Tolstrup M, Brinkmann CR, Olesen R, Erikstrup C, Solomon A, Winckelmann A, Palmer S, Dinarello C, Buzon M, Lichterfeld M, Lewin SR, Ostergaard L, Sogaard OS. 2014. Panobinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, for latent-virus reactivation in HIV-infected patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy: a phase 1/2, single group, clinical trial. Lancet HIV 1:e13–. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(14)70014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sogaard OS, Graversen ME, Leth S, Olesen R, Brinkmann CR, Nissen SK, Kjaer AS, Schleimann MH, Denton PW, Hey-Cunningham WJ, Koelsch KK, Pantaleo G, Krogsgaard K, Sommerfelt M, Fromentin R, Chomont N, Rasmussen TA, Ostergaard L, Tolstrup M. 2015. The depsipeptide romidepsin reverses HIV-1 latency in vivo. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005142. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pasternak AO, Lukashov VV, Berkhout B. 2013. Cell-associated HIV RNA: a dynamic biomarker of viral persistence. Retrovirology 10:41. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Ross AL, Ananworanich J, Benkirane M, Cannon P, Chomont N, Douek D, Lifson J, Lo Y-R, Kuritzkes D, Margolis D, Mellors J, Persaud D, Tucker JD, Barre-Sinoussi F, International AIDS Society towards a Cure Working Group. 2016. International AIDS Society global scientific strategy: towards an HIV cure 2016. Nat Med 22:839–850. doi: 10.1038/nm.4108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ke R, Lewin SR, Elliott JH, Perelson AS. 2015. Modeling the effects of vorinostat in vivo reveals both transient and delayed HIV transcriptional activation and minimal killing of latently infected cells. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005237. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shan L, Deng K, Shroff NS, Durand CM, Rabi SA, Yang H-C, Zhang H, Margolick JB, Blankson JN, Siliciano RF. 2012. Stimulation of HIV-1-specific cytolytic T lymphocytes facilitates elimination of latent viral reservoir after virus reactivation. Immunity 36:491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maldarelli F, Wu X, Su L, Simonetti FR, Shao W, Hill S, Spindler J, Ferris AL, Mellors JW, Kearney MF, Coffin JM, Hughes SH. 2014. Specific HIV integration sites are linked to clonal expansion and persistence of infected cells. Science 345:179–183. doi: 10.1126/science.1254194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner TA, McLaughlin S, Garg K, Cheung CYK, Larsen BB, Styrchak S, Huang HC, Edlefsen PT, Mullins JI, Frenkel LM. 2014. Proliferation of cells with HIV integrated into cancer genes contributes to persistent infection. Science 345:570–573. doi: 10.1126/science.1256304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorenzo-Redondo R, Fryer HR, Bedford T, Kim E-Y, Archer J, Pond SLK, Chung Y-S, Penugonda S, Chipman JG, Fletcher CV, Schacker TW, Malim MH, Rambaut A, Haase AT, McLean AR, Wolinsky SM. 2016. Persistent HIV-1 replication maintains the tissue reservoir during therapy. Nature 530:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nature16933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones RB, O'Connor R, Mueller S, Foley M, Szeto GL, Karel D, Lichterfeld M, Kovacs C, Ostrowski MA, Trocha A, Irvine DJ, Walker BD. 2014. Histone deacetylase inhibitors impair the elimination of HIV-infected cells by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004287. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshizuka N, Yoshizuka-Chadani Y, Krishnan V, Zeichner SL. 2005. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr-dependent cell cycle arrest through a mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway. J Virol 79:11366–11381. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11366-11381.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petravic J, Ellenberg P, Chan ML, Paukovics G, Smyth RP, Mak J, Davenport M. 2014. Intracellular dynamics of HIV infection. J Virol 88:1113–1124. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02038-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.VanderMolen KM, McCulloch W, Pearce CJ, Oberlies NH. 2011. Romidepsin (Istodax, NSC 630176, FR901228, FK228, depsipeptide): a natural product recently approved for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Antibiot 64:525–531. doi: 10.1038/ja.2011.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rasmussen TA, Lewin SR. 2016. Shocking HIV out of hiding. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 11:394–401. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doitsh G, Galloway NLK, Geng X, Yang Z, Monroe KM, Zepeda O, Hunt PW, Hatano H, Sowinski S, Muñoz-Arias I, Greene WC. 2014. Cell death by pyroptosis drives CD4 T-cell depletion in HIV-1 infection. Nature 505:509–514. doi: 10.1038/nature12940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baxter AE, Niessl J, Fromentin R, Richard J, Porichis F, Charlebois R, Massanella M, Brassard N, Alsahafi N, Delgado G-G, Routy J-P, Walker BD, Finzi A, Chomont N, Kaufmann DE. 2016. Single-cell characterization of viral translation-competent reservoirs in HIV-infected individuals. Cell Host Microbe 20:368–380. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Badley AD, Sainski A, Wightman F, Lewin SR. 2013. Altering cell death pathways as an approach to cure HIV infection. Cell Death Dis 4:e718–. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perelson AS, Neumann AU, Markowitz M, Leonard JM, Ho DD. 1996. HIV-1 dynamics in vivo: virion clearance rate, infected cell life-span, and viral generation time. Science 271:1582–1586. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramratnam B, Bonhoeffer S, Binley J, Hurley A, Zhang L, Mittler JE, Markowitz M, Moore JP, Perelson AS, Ho DD. 1999. Rapid production and clearance of HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus assessed by large volume plasma apheresis. Lancet 354:1782–1785. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conway JM, Perelson AS. 2016. Residual viremia in treated HIV+ individuals. PLoS Comput Biol 12:e1004677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]