ABSTRACT

The lentiviral accessory proteins Vpx and Vpr are known to utilize CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase to induce the degradation of the host restriction factor SAMHD1 or host helicase transcription factor (HLTF), respectively. Selective disruption of viral CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase could be a promising antiviral strategy. Recently, we have determined that posttranslational modification (neddylation) of Cullin-4 is required for the activation of Vpx-CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase. However, the mechanism of Vpx/Vpr-CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase assembly is still poorly understood. Here, we report that zinc coordination is an important regulator of Vpx-CRL4 E3 ligase assembly. Residues in a conserved zinc-binding motif of Vpx were essential for the recruitment of the CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 complex and Vpx-induced SAMHD1 degradation. Importantly, altering the intracellular zinc concentration by treatment with the zinc chelator N,N,N′-tetrakis-(2′-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine (TPEN) potently blocked Vpx-mediated SAMHD1 degradation and inhibited wild-type SIVmac (simian immunodeficiency virus of macaques) infection of myeloid cells, even in the presence of Vpx. TPEN selectively inhibited Vpx and DCAF1 binding but not the Vpx-SAMHD1 interaction or Vpx virion packaging. Moreover, we have shown that zinc coordination is also important for the assembly of the HIV-1 Vpr-CRL4 E3 ligase. In particular, Vpr zinc-binding motif mutation or TPEN treatment efficiently inhibited Vpr-CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase assembly and Vpr-mediated HLTF degradation or Vpr-induced G2 cell cycle arrest. Collectively, our study sheds light on a conserved strategy by the viral proteins Vpx and Vpr to recruit host CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase, which represents a target for novel anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) drug development.

IMPORTANCE The Vpr and its paralog Vpx are accessory proteins encoded by different human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) lentiviruses. To facilitate viral replication, Vpx has evolved to induce SAMHD1 degradation and Vpr to mediate HLTF degradation. Both Vpx and Vpr perform their functions by recruiting CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase. In this study, we demonstrate that the assembly of the Vpx- or Vpr-CRL4 E3 ligase requires a highly conserved zinc-binding motif. This motif is specifically required for the DCAF1 interaction but not for the interaction of Vpx or Vpr with its substrate. Selective disruption of Vpx- or Vpr-CRL4 E3 ligase function was achieved by zinc sequestration using N,N,N′-tetrakis-(2′-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine (TPEN). At the same time, zinc sequestration had no effect on zinc-dependent cellular protein functions. Therefore, information obtained from this study may be important for novel anti-HIV drug development.

KEYWORDS: zinc binding, Vpx, CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase, Vpr, cell cycle arrest

INTRODUCTION

Lentiviruses carrying accessory genes have evolved to counteract the effects of host cellular restriction factors that inhibit viral infection (1–10). Vpr and its homologous viral protein, Vpx, which are encoded by human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), are specifically packaged into virus particles (11, 12) through an interaction with the p6 region of the Gag precursor (13–18), indicating a role in the early steps of the virus life cycle. More importantly, Vpr is required for viral dissemination and disease progression (19–23). Vpx is a virion-associated viral accessory protein present in HIV-2 and selected SIV lineages (15, 18). Although Vpx has only a moderate effect on viral replication in CD4+ T lymphocytes, with some degree of individual variation (10, 24–26), it is essential for efficient viral replication in macrophages (10, 27) and dendritic cells (28, 29). In SIV-infected monkeys, Vpx is required for viral dissemination and disease progression (30, 31).

Both Vpr and Vpx are released into infected cells after virus fusion (13, 17, 18); they are localized to the nuclei of the infected cells (32–36) and engage the CRL4A (DCAF1) E3 ubiquitin ligase through binding to the DCAF1 substrate specificity receptor (37–40). Despite these similarities, the functional outcomes of engaging the same E3 ubiquitin ligase are very different for Vpr and Vpx. The major phenotype ascribed to Vpr is the induction of G2/M cell cycle arrest in dividing cells, and this activity has been previously reported to be a feature of several SIV Vpr proteins (41–43). Recently, Vpr has been identified as inducing the degradation of host helicase transcription factor (HLTF) (44, 45) and removing viral DNA by recruiting SLX4-MUS81 complexes (46, 47).

The Vpx-CRL4A (DCAF1) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (8, 48) can degrade the restriction factor SAM domain and HD domain-containing protein 1 (SAMHD1) (49, 50), which inhibits HIV-1 infection of myeloid-lineage cells as well as resting CD4+ T cells by depleting cellular deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) to a level at which the viral reverse transcriptase cannot function (4, 51–56). To efficiently block Vpx function, one promising approach is to directly impair the interaction between Vpx and CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase. Previous studies have further demonstrated an evolutionary “arms race” between primate SAMHD1 and lentiviral Vpx; antagonism of SAMHD1 by Vpx occurs in a species-specific manner (57, 58).

We and other groups have recently demonstrated that the posttranslational modification process of neddylation, which is a determinant for the activation of Cullin-RING E3 ligases, is essential for the activity of the Vpx-CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase (59–61). The neddylation inhibitor MLN4924 blocks Vpx function and preserves the antiviral activity of SAMHD1. However, neddylation is important for normal cellular regulation (62–64), a consideration that clearly affects its use as an optimal antiviral target.

The crystal structures of Vpx (8) and Vpr (40) have identified novel zinc-binding motifs. Similar residues in a potential zinc-binding motif are present in diverse Vpx and Vpr proteins of primate lentiviruses. In the present study, we determined that the zinc-binding motifs are crucial for the function of Vpx and Vpr. Furthermore, we demonstrated inhibition of Vpx or Vpr function through targeting the zinc-binding motif by using a zinc chelator, N,N,N′-tetrakis-(2′-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine (TPEN); in contrast, the zinc chelator had no effect on either the antiviral function of zinc-binding SAMHD1 or the cellular CRL4 E3 complex assembly. Therefore, our results reveal a novel zinc-dependent mechanism that may represent a more suitable target for drug design to antagonize primate lentiviruses.

RESULTS

The highly conserved HHCC motif of Vpx is essential for the Vpx-dependent degradation of SAMHD1 and viral infection in myeloid cells.

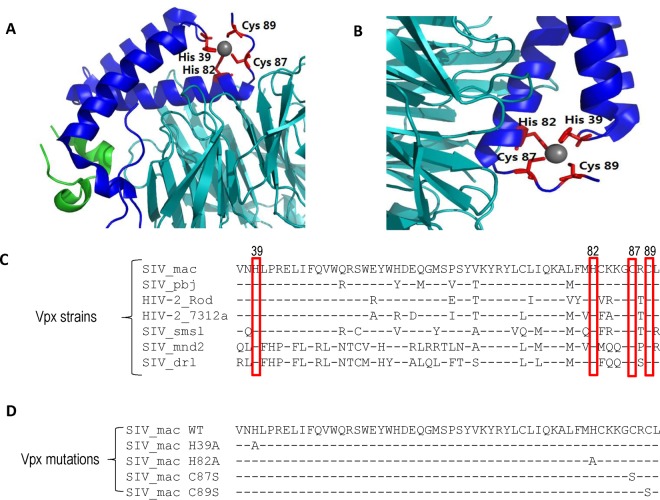

Vpx assembles with DCAF1, DDB1, and Cullin4A to form CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 complexes to induce the ubiquitination and degradation of SAMHD1 (8, 37–39). The crystal structure of the Vpx/DCAF1/SAMHD1 complex revealed an HHCC zinc ion-binding motif (8), but the role of this zinc-binding motif in Vpx function has not been fully characterized. The HHCC residues are not directly involved in the SAMHD1 (Fig. 1A) or DCAF1 (Fig. 1B) interactions. However, this motif is highly conserved among Vpx molecules from diverse HIV-2 and SIV lentiviruses, even when the surrounding amino acids are highly variable (Fig. 1C). To investigate the role of this motif in Vpx functions, we generated a series of single amino acid substitutions (H39A, H82A, C87S, and C89S) in SIVmac239 Vpx (Fig. 1D).

FIG 1.

The highly conserved HHCC motif in Vpx. (A) Structural representation of the Vpx/SAMHD1-CtD/DCAF1-CtD ternary complex. Color codes for the proteins are indicated. The zinc ion is shown as a gray sphere, and HHCC residues of Vpx are in red. DCAF1 is shown in cyan; cylinders represent helices in SAMHD1 (green) and Vpx (blue). Structural superposition was carried out in PDBeFold. CtD, C-terminal domain. (B) Cartoon showing the contact area between the HCCH domain of Vpx and DACF1. (C) Alignment of the zinc-binding sequence of Vpx. A highly conserved domain (H39, H82, C87, and C89) in Vpx was identified in various HIV-2/SIV Vpx proteins, including those from SIVmac239 (GenBank accession no. AAL55641.1), HIV-2 Rod (GenBank accession no. P06939), HIV-2 7312a (GenBank accession no. AAL31353.1), SIV drl (GenBank accession no. AAO22468.1), SIV mnd2 (GenBank accession no. AAK82846.1), SIV pbj (GenBank accession no. AAB59772.1), and SIV smsl (GenBank accession no. AAK55277.1). (D) Schematic representation of the mutations (H39A, H82A, C87S, and C89S) of the HCCH motif in SIVmac239 Vpx used in this study.

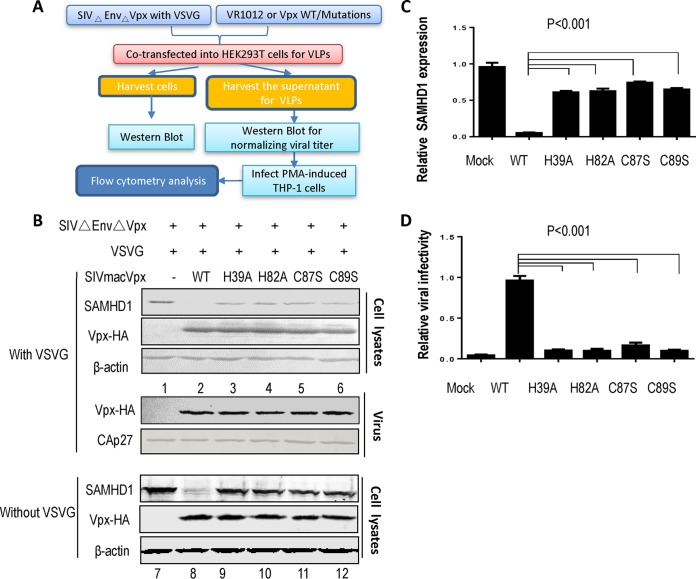

We first evaluated Vpx HHCC mutants with regard to SAMHD1 degradation and viral infection in SAMHD1-functional myeloid cells (39, 60, 65) using a well-established functional assay, as outlined in Fig. 2A. Expression vectors for wild-type (WT) Vpx and Vpx mutants were cotransfected with pSIVΔEnvΔVpx-GFP (37) and pVSV-G into HEK 293T cells. After 48 h, transfected cells were harvested and subjected to Western blotting (Fig. 2B). As expected, WT Vpx expression totally led to the depletion of SAMHD1 in transfected HEK 293T cells (Fig. 2B, lane 2, and C) compared to the control sample (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2B, lane 1, and C). All the Vpx mutants with mutations in the zinc-binding motif showed impaired Vpx-induced degradation of SAMHD1 compared to WT Vpx (Fig. 2B, compare lane 2 with lanes 3 to 6, anti-SAMHD1, and C). Reproducible results indicated that all the Vpx mutants were defective in terms of inducing SAMHD1 depletion compared to WT Vpx (Fig. 2B and C).

FIG 2.

The HHCC domain is crucial for Vpx-induced human SAMHD1 degradation and SIV infection. (A) Schematic representation of the effects of zinc-binding domain Vpx mutants on viral infectivity and SAMHD1 degradation. In this study, Vpx WT or one of the mutants was cotransfected with SIVmac239ΔEnvΔVpx-GFP into HEK 293T cells with or without VSV-G. Supernatants containing VLPs were collected and used to infect PMA-induced macrophage-like THP-1 cells. Viral infectivity was measured by flow cytometry. (B) The mutations in the HHCC domain affect Vpx-mediated SAMHD1 degradation. HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with a control vector or one of the Vpx WT/mutants, SIVmac239ΔEnvΔVpx-GFP, and VSV-G. At 48 h posttransfection, the expression levels of endogenous SAMHD1 and Vpx with an HA tag were analyzed by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as the loading control. (C) Relative expression of endogenous SAMHD1. Endogenous SAMHD1 expression levels with or without (100%) Vpx were measured (n = 3, mean ± SD). Error bars represent the standard deviation from triplicate independent experiments. P < 0.001, by ANOVA test. (D) Effects of Vpx mutations on SIV infection in PMA–THP-1 cells. The harvested virus was used to infect PMA-treated (100 ng/ml per day) macrophage-like THP-1 cells for 3 days, and then the cells were examined by flow cytometry for GFP-positive cells. Representative flow cytometry data are shown. Relative infective ability of Vpx-containing SIV VLPs (100%) and Vpx mutants containing SIV VLPs (n = 3, mean ± SD). Error bars represent the standard deviation from triplicate independent experiments. P < 0.001, by ANOVA test.

SAMHD1 is able to restrict Vpx-deficient HIV-2/SIV viral infectivity in myeloid cells and resting CD4+ T cells (53, 66). By recruiting the Cullin4A-containing E3 ubiquitin ligase, the virion-packaged protein Vpx overcomes the restriction imposed by SAMHD1 and promotes viral infection in myeloid cells in the early phase of the viral replication cycle (4). To examine the role of the Vpx HHCC motif in promoting viral infection, we used differentiated myeloid cells (differentiated THP-1 cells) to investigate the infectivity of the viruses generated as outlined in Fig. 2A. THP-1 cells were pretreated with 100 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) overnight, and the cells were then challenged by viruses with equal amounts of CAp27. After 48 h, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-positive cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Consistent with previous reports, Vpx was required for efficient SIVmac infection of differentiated myeloid cells (Fig. 2D). In the absence of Vpx, SIVmacΔVpx infectivity was >90% lower than in its presence (Fig. 2D). At the same time, the data revealed that the zinc-binding motif mutants of Vpx failed to efficiently facilitate viral infection in differentiated THP-1 cells (>80% reduction) compared to WT Vpx (Fig. 2D; P < 0.001 versus WT). Thus, the zinc-binding motif is crucial for Vpx-induced SAMHD1 degradation and enhancement of viral infectivity in myeloid cells. Our data showed that endogenous SAMHD1 is completely wiped out by WT Vpx (Fig. 2B, lane 2), which may suggest that there is reinfection of the cells by the vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSV-G)-pseudotyped virus. To address this issue, we repeated the experiments without VSV-G. As expected, the endogenous SAMHD1 degradation by Vpx WT or mutants was less efficient in the absence of VSV-G, which revealed that the 100% deletion of SAMHD1 was due to reinfection by the Vpx containing VSV-G-pseudotyped virion. However, the SAMHD1 expression level by Vpx mutants in the presence of VSV-G was shown to be similar to that in the absence of VSV-G.

The zinc-binding motif is critical for Vpx-CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase assembly but not for the recruitment of SAMHD1.

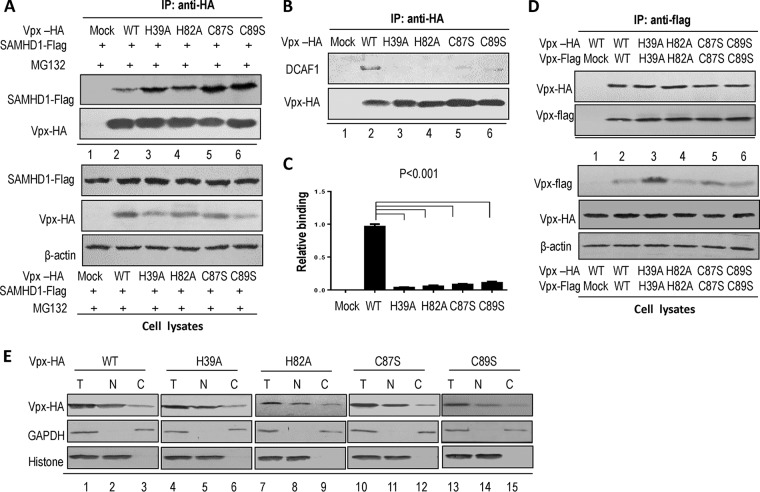

To further investigate whether the functional domain of Vpx is involved in the recruitment of CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase or its substrate SAMHD1, we performed coimmunoprecipitation assays using samples from transfected HEK 293T cells. For the Vpx-SAMHD1 interaction, HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Vpx WT or mutant (H39A, H82A, C87S, or C89S) plus Flag-tagged SAMHD1. After 24 h, the cells were treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10 μM) overnight to prevent SAMHD1 degradation. Treated cells were harvested, lysed, and subjected to immunoprecipitation as previously described (6). SIVmac Vpx interacted with SAMHD1 in the coimmunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 3A, lane 2). In the absence of Vpx, SAMHD1 was not detected (Fig. 3A, lane 1), indicating that the interaction between Vpx and SAMHD1 was specific. The results of the analogous experiments showed that all the Vpx mutants maintained the ability to bind SAMHD1 compared to WT Vpx (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3.

Effects of mutations in the Vpx HHCC domain on the interaction between Vpx and DCAF1 or human SAMHD1. (A) Ability of WT or Vpx mutants to interact with SAMHD1. HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with WT or one of the Vpx-HA mutants and SAMHD1-Flag. At 12 h posttransfection, the cells were treated with MG132 (10 μM) for 12 h. At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation with anti-HA affinity matrix. Protein expression was confirmed by Western blotting of cell lysates. The interaction of SAMHD1 with WT or the Vpx mutants was detected by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody to detect Vpx-HA and anti-Flag antibody to detect human SAMHD1 (IP: anti-HA). (B) Mutants of the zinc domain in Vpx decreased the interaction with DCAF1. HEK 293T cells were transfected with a control vector or WT or mutant Vpx-HA expression vector. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were harvested, immunoprecipitated with anti-HA affinity matrix, and then analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody to detect Vpx-HA and anti-DCAF1 antibody to detect endogenous DCAF1 (IP: anti-HA). (C) Relative ability of WT Vpx (100%) and Vpx mutants to bind DCAF1 (n = 3, mean ± SD). Error bars represent the standard deviation from triplicate experiments. P < 0.001, by ANOVA test. (D) Mutations in the Vpx HHCC domain have no effect on the dimerization of Vpx. HEK 293T cells were transfected with a control vector or WT or mutant Vpx-Flag expression vector and WT or mutant Vpx-HA. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were harvested, immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag affinity matrix, and then analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody to detect Vpx-HA and anti-Flag antibody to detect Vpx-Flag (IP: anti-flag). (E) Effect of mutations in the HHCC domain on the subcellular localization of Vpx. HEK 293T cells were transfected with WT or mutant Vpx-HA. Then, nuclei and cytoplasm were extracted from cells. All samples were analyzed by Western blotting. Histone was used as the loading control of nuclei, and recombinant glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as the loading control for cytoplasm or the total cell lysate. T, total cell lysate; N, nuclei; C, cytoplasm.

We then examined the role of the zinc-binding motif in the interaction between Vpx and DCAF1. HA-tagged Vpx WT or mutants (H39A, H82A, C87S, and C89S) were expressed in HEK 293T cells. Cells were harvested, lysed, and then loaded onto HA agarose-conjugated beads for immunoprecipitation. Our Western blotting data indicated that the DCAF1 binding of all these Vpx variants was significantly decreased (80% to 95%) compared to that of WT Vpx (Fig. 3B and C). This interaction was specific, since endogenous DCAF1 was not detected in the absence of Vpx (Fig. 3B, lane 1). Collectively, the zinc-binding site mutants of Vpx impaired Vpx-CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase assembly, consistent with their reduced ability to cause Vpx-dependent SAMHD1 degradation. To examine whether the HHCC motif in Vpx is important for its dimerization, a negative-control VR1012 or WT or mutant Vpx-Flag with WT or mutant Vpx-HA was transfected into HEK 293T cells, and then the cells were loaded onto Flag agarose-conjugated beads for immunoprecipitation. The results showed that all mutations (Fig. 3D, lanes 3 to 6) maintained the ability to form dimers compared to Vpx WT (Fig. 3D, lane 2). This interaction was specific, since Vpx-HA was not detected in the absence of Vpx-Flag (Fig. 3D, lane 1). SAMHD1 is primarily found in the nucleus (67), and Vpx is also known to be predominantly translocated to the nucleus (31, 39), so nuclear localization of Vpx may be required for Vpx-mediated degradation of SAMHD1. To evaluate the potential effect of mutations on the subcellular localization of Vpx, we transfected Vpx-HA WT or mutations into HEK 293T cells for chromatin fractionation. The results indicated that Vpx WT and mutations were localized both to the cytoplasm (Fig. 3D, lane 3) and to the nucleus (Fig. 3D, lane 2) but were predominantly in the nucleus as reported before. Thus, the mutations in the HHCC domain of Vpx significantly inhibit Vpx-dependent viral infection and Vpx-induced SAMHD1 degradation not by abolishing dimerization or localization of Vpx but by impairing Vpx-CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase assembly.

The zinc chelator TPEN inhibits Vpx-mediated SAMHD1 degradation and Vpx-dependent viral infection.

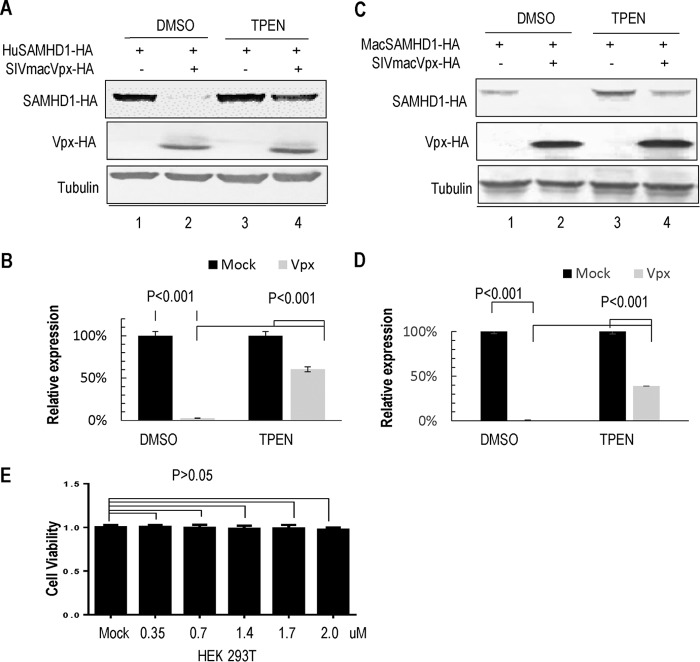

The HHCC residues of Vpx do not directly interact with DCAF1 (8). It is therefore plausible that zinc coordination is important for Vpx's interaction with DCAF1. To test this hypothesis, we used the membrane-permeable zinc chelator TPEN to evaluate the requirement for zinc in Vpx-induced SAMHD1 degradation. HA-tagged human SAMHD1 was expressed with or without SIVmac239 Vpx in HEK 293T cells. Cells were treated with 1.79 μM TPEN, or an equal volume of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a control, for 12 h prior to harvesting and then analyzed by Western blotting. The results showed that TPEN treatment potently impaired Vpx-induced human SAMHD1 degradation (P < 0.001 versus DMSO treatment) (Fig. 4A and B). To further address the effects of SIVmac-encoded Vpx on the samhd1 gene product of the natural host Macaca mulatta, we cotransfected pMac-SAMHD1-HA with SIVmac239 Vpx or empty vector VR1012 into HEK 293T cells. After 24 h, the cells were treated with 1.79 μM TPEN or the equivalent volume of DMSO, respectively. We found that Vpx-induced Mac-SAMHD1 degradation could be inhibited by TPEN (Fig. 4C and D). Furthermore, the various concentrations of TPEN tested had no detectable effect on the viability of the HEK 293T cells (P > 0.05 versus DMSO treatment) (Fig. 4E).

FIG 4.

TPEN treatment inhibits Vpx-induced degradation of SAMHD1. (A) TPEN inhibits the degradation of human SAMHD1 by SIVmac Vpx. HEK 293T cells were transfected with a control vector or WT or mutant Vpx-HA expression vector and human SAMHD1-HA. At 12 h after transfection, the cells were treated with DMSO or TPEN for 12 h and then analyzed by Western blotting. (B) Effects of TPEN on the relative expression of human SAMHD1 with or without (100%) Vpx (n = 3, mean ± SD). Error bars represent the standard deviation from three experiments. P < 0.001, by ANOVA test. (C) TPEN inhibits the degradation of Mac-SAMHD1 by SIVmac Vpx. A method similar to that described above was used. (D) Effects of TPEN on the relative expression of Mac-SAMHD1 with or without (100%) Vpx are shown in the bar graph (n = 3, mean ± SD). Error bars represent the standard deviation from three experiments. P < 0.001, by ANOVA test. (E) MTT assay results for assessing the metabolic activity of HEK 293T cells after TPEN treatment are shown in the bar graph (n = 3, mean ± SD). Error bars represent the standard deviations from triplicate experiments. P > 0.05, by ANOVA test.

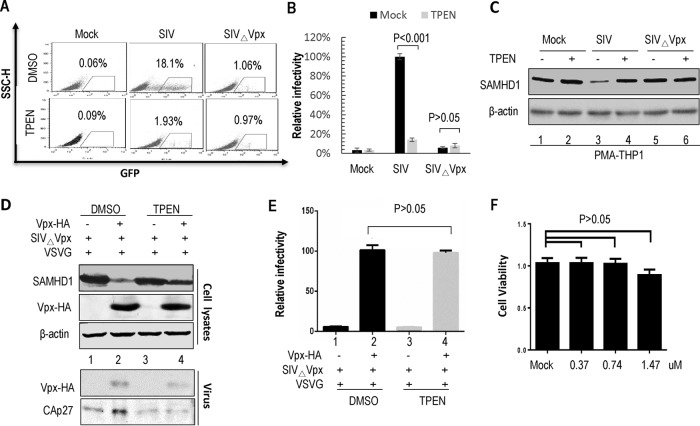

To investigate the impact of TPEN treatment on Vpx-dependent viral infection, we cultured THP-1 cells with 100 nM PMA for 24 h to promote differentiation and then treated them with 1.4 μM TPEN or DMSO for 12 h. The treated cells were then infected with the same viral titer of the G protein of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV-G)-pseudotyped SIVmac-GFP or SIVmacΔVpx-GFP virus-like particles (VLPs). Compared to control samples, TPEN-treated cells showed significantly lower viral infection with SIVmac-GFP, and the ratio of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-positive cells (TPEN treated to control) decreased by more than 80% (Fig. 5A and B, P < 0.001 versus DMSO treatment). As expected, SIVmacΔVpx-GFP infection was inhibited in PMA-treated macrophage-like THP-1 cells compared to SIVmac-GFP. The Western blotting results indicated that the SIVmac-GFP virus infectivity induced endogenous SAMHD1 degradation (Fig. 5C, lane 3), which was blocked by TPEN treatment (Fig. 5C, lane 4).

FIG 5.

TPEN treatment inhibits Vpx-induced SIV infection in macrophage cells. (A) TPEN is a highly effective inhibitor of Vpx-dependent SIVmac infection in PMA-treated macrophage-like THP-1 cells. THP-1 cells were pretreated with PMA for 1 day and then incubated with DMSO or TPEN for 12 h. The two groups of treated cells were infected with equivalent amounts of SIVmac239-ΔVpx-GFP or SIVmac239-GFP VLPs. The percentage of GFP-positive cells was determined by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry data are shown. (B) The relative infectivity of SIVmac293-GFP (100%) or SIVmac239-ΔVpx-GFP VLPs in PMA-induced macrophage-like THP-1 cells after TPEN treatment is shown in the bar graph (n = 3, mean ± SD). Error bars represent the standard deviation from triplicate experiments. P < 0.001, by ANOVA test. (C) The effect of TPEN treatment on SAMHD1 expression during SIVmac infection of primary macrophages. Cell extracts were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-SAMHD1 antibody to detect endogenous SAMHD1. β-Actin was used as the loading control. (D) Effect of TPEN on the amount of Vpx packaged into VLPs. HEK 293T cells were transfected with a control vector or WT or mutant Vpx-HA expression vector and SIVmac239-ΔVpx-GFP. At 6 h after transfection, the cells were treated with DMSO or TPEN for 48 h. The supernatants were centrifuged and then analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. (E) Viral infection ability in PMA-treated THP-1 cells. Virions obtained in the experiment in panel D were used to infect the PMA-treated THP-1 cells for 48 h, and the infection ability was determined by flow cytometry. (F) Results of the MTT assay for assessing the metabolic activity of PMA–THP-1 cells after TPEN treatment are shown in the bar graph (n = 3, mean ± SD). Error bars represent the standard deviation from triplicate experiments. P > 0.05, by ANOVA test.

To evaluate the potential effect of TPEN on Vpx packaging into SIV virions, we cotransfected the pHA-Vpx vector, or empty vector, with VSV-G and SIVmac239ΔENVΔVpx–GFP into HEK 293T cells. After 6 h, 1.79 μM DMSO or TPEN was added to the cells for 48 h. The supernatants and cells were harvested, purified, and analyzed by Western blotting. Our data indicated that the expression of SAMHD1 was inhibited by TPEN treatment of HEK 293T cells (Fig. 5D, lane 4) compared to expression in HEK 293T cells not treated with TPEN (Fig. 5D, lane 2). Moreover, TPEN had no influence on the amount of Vpx protein packaged into SIVmac virions (Fig. 5D, lane 4) and did not affect the ability of virus to infect PMA-treated THP-1 cells (Fig. 5E, lane 4) compared to DMSO treatment (Fig. 5D, lane 2, and E, lane 2, P > 0.05 versus DMSO treatment). Furthermore, treatment of the THP-1 cells with the various doses of TPEN had no adverse effect on cell viability (Fig. 5F, P > 0.05 versus DMSO treatment). Thus, the zinc chelator TPEN significantly inhibits Vpx-dependent viral infection by abolishing Vpx-mediated degradation of SAMHD1.

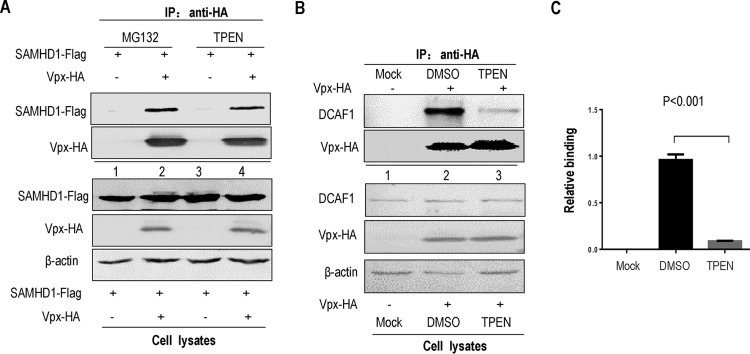

TPEN treatment selectively inhibits the interaction of Vpx and DCAF1.

Given the essential role of the zinc-binding motif of Vpx in the interaction between Vpx and DCAF1, we next checked whether the metal chelator TPEN would interfere with Vpx function by removing the Vpx protein from the CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase or by disrupting the binding between Vpx and SAMHD1. pHA-Vpx and pFlag-SAMHD1 or pHA-Vpx alone was transfected into HEK 293T cells, and 1.79 μM TPEN/10 μM MG132 or DMSO was injected into the culture medium at 36 h posttransfection. After another 12 h, the cells were harvested and lysed for anti-HA immunoprecipitation. The results indicated that TPEN treatment did not destroy the ability of Vpx to bind to SAMHD1, compared to MG132 treatment (Fig. 6A, lanes 2 and 4), but it dramatically decreased the binding of DCAF1 to Vpx (>85%) (Fig. 6B, compare lanes 2 and 3; Fig. 6C, P < 0.001 versus DMSO treatment). This interaction was apparently specific, since endogenous DCAF1 was not detected in the absence of Vpx (Fig. 6B, lane 1). Thus, our studies showed that the zinc chelator TPEN affects zinc binding by the Vpx protein and impairs Vpx-CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 complex assembly, perhaps by destroying the normal conformation of the zinc-binding domain in Vpx.

FIG 6.

Effect of TPEN or MG132 on the interaction of Vpx with DCAF1 or SAMHD1. (A) Effects of TPEN and MG132 on the interaction between Vpx and SAMHD1. A control vector or Vpx expression vector and SAMHD1 expression vector were cotransfected into HEK 293T cells. After 12 h of transfection, the cells were treated with DMSO or TPEN/MG132 for 12 h. The cells were harvested, then immunoprecipitated with anti-HA affinity matrix, and then analyzed by Western blotting. The interaction of SAMHD1 with WT or mutant Vpx molecules was detected by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody to detect Vpx-HA and anti-Flag antibody to detect SAMHD1. (B) The effect of TPEN on the expression of Vpx in HEK 293T cells and the binding activity of Vpx with endogenous DCAF1. Protein expression was confirmed by Western blotting of cell lysates. The binding activity was detected by coimmunoprecipitation with anti-HA affinity matrix, and the immunoprecipitates were subjected to Western blotting (IP: anti-HA). (C) The relative binding activities of Vpx and DCAF1 after DMSO or TPEN treatment were measured and are shown in the bar graph (n = 3, mean ± SD).

TPEN treatment has no effect on cellular E3 complex assembly.

Selective inhibition of Vpx function benefits from the failure of TPEN treatment to cause cellular toxicity. Therefore, we asked whether TPEN treatment would affect DCAF1 assembly with other CRL4 E3 ligase components. DDB1-Flag and a control vector or DCAF1-HA expression vector were transfected into HEK 293T cells. At 12 h posttransfection, 1.79 μM TPEN or DMSO was added to the culture medium for 12 h. The cells were then harvested and lysed for anti-HA immunoprecipitation. Western blotting revealed that TPEN had no effect on the expression of DDB1 or DCAF1 (Fig. 7A, compare lanes 2 and 3) and did not disrupt the interaction between DDB1 and DCAF1 (P > 0.05 versus DMSO treatment) (Fig. 7B, compare lanes 2 and 3, and C).

FIG 7.

TPEN treatment does not affect DCAF1 and DDB1 interaction. (A) Effect of TPEN on the expression of DCAF1 and DDB1. HEK 293T cells were transfected with a control vector or DCAF1-HA expression vector and DDB1-Flag. At 12 h posttransfection, a portion of the cells was treated with DMSO or TPEN for 12 h, and cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting with anti-Flag and anti-HA antibody to detect DDB1 and DCAF1. (B) Effect of TPEN on the binding activity of DCAF1 to DDB1. Cell lysates from the groups in panel A were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA affinity matrix and then analyzed by Western blotting (IP: HA). (C) The effect of TPEN inhibition of the relative binding activity of DCAF1 to DDB1 is shown in the bar graph of the DDB1/DCAF1 binding ratios (n = 3, mean ± SD). Error bars represent the standard deviation from triplicate experiments. P > 0.05, by ANOVA test.

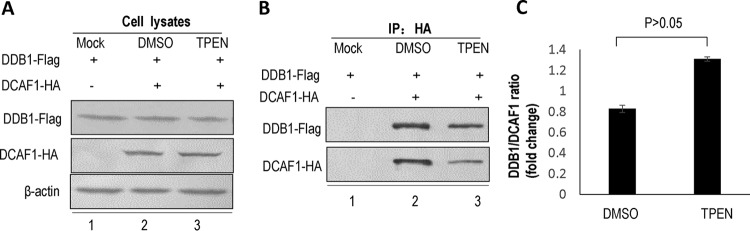

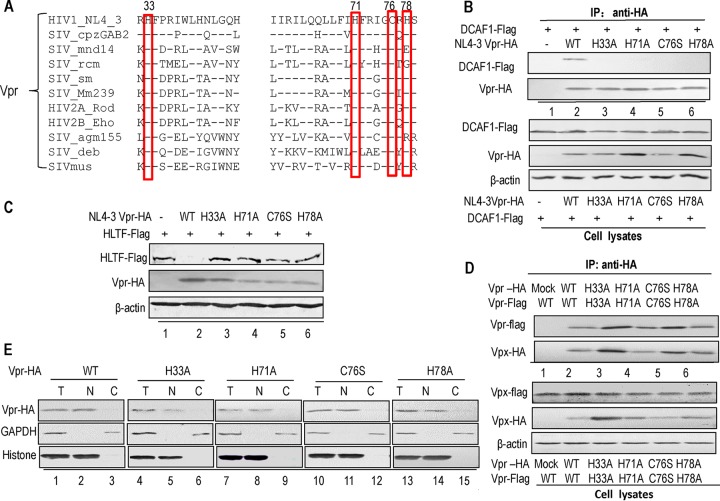

The HHCH motif is critical for HIV-1 Vpr-CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase assembly and Vpr-induced HLTF degradation.

As for Vpx, sequence analysis of the Vpr proteins from diverse HIVs and SIVs has indicated the presence of a potential zinc-binding motif (Fig. 8A). To examine whether the HHCH motif in HIV-1 Vpr is also important for its function, we generated a series of constructs of zinc-binding site mutants (H33A, H71A, C76S, and H78A) of HIV-1 Vpr. pHA-Vpr WT or one of the mutants was cotransfected with pFlag-DCAF1 into HEK 293T cells for 48 h, and the cells were subsequently harvested for coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP). The co-IP results revealed that all the HHCH motif mutants showed an impaired ability to bind DCAF1 (Fig. 8B, lanes 3 to 6) compared to WT Vpr (Fig. 8B, lane 2). Recent reports have indicated that Vpr can utilize CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase to induce HLTF degradation (44, 45). To address the role of the zinc-binding motif in HLTF degradation mediated by Vpr, we transfected the WT or mutant Vpr expression vectors and HLTF expression vector into HEK 293T cells. At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were harvested for Western blotting. All of the tested zinc-binding site mutations impaired Vpr-induced degradation of HLTF (Fig. 8C, lanes 3 to 6) compared to WT Vpr (Fig. 8C, lane 2). To determine whether mutations in the HHCH motif affect Vpr function through destroying dimerization or localization of Vpr, a negative-control VR1012 or WT or mutant Vpr-HA with WT or mutant Vpr-Flag was transfected into HEK 293T cells and then the cells were loaded onto HA agarose-conjugated beads for immunoprecipitation. The results showed that all the mutations (Fig. 8D, lanes 3 to 6) maintained the ability to form dimers compared to Vpx WT (Fig. 8D, lane 2). This interaction was specific, since Vpx-HA was not detected in the absence of Vpx-Flag (Fig. 8D, lane 1). For the potential effect of mutations on the subcellular localization of Vpr, we transfected Vpx-HA WT or mutations into HEK 293T cells for chromatin fractionation. The results indicated that all the mutations were localized in the nucleus (Fig. 8E, lanes 2, 4, 7, 10, and 13) compared to the localization of Vpr WT (Fig. 8E, lane 2).

FIG 8.

Mutations in the conserved HHCH motif of Vpr affect the interaction with DCAF1 and Vpr-mediated degradation of HLTF. (A) Alignment of the zinc-binding sequences of various HIV/SIV Vpr subtypes, including HIV-1 NL4-3 (GenBank accession no. P12520.2), HIV-2A Rod (GenBank accession no. P06938), HIV-2B Eho (GenBank accession no. U27200.1), SIV cpzGAB2 (GenBank accession no. AF382828.1), SIV agm155 (GenBank accession no. P27976), SIV deb (GenBank accession no. FJ919724.2), SIV rcm (GenBank accession no. ADK78264.1), SIV Mm239 (GenBank accession no. EU280806.2), SIV mus (GenBank accession no. AAR02370.1), SIV sm (GenBank accession no. JX860419.1), and SIV mnd14 (GenBank accession no. AAK82847.1). (B) Mutants in the highly conserved HHCH motif of Vpr have lost the ability to interact with DCAF1. A control vector or Vpr expression vector and the DCAF1 expression vector were cotransfected into HEK 293T cells. At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were harvested and immunoprecipitated with anti-HA affinity matrix and then analyzed by Western blotting (IP: anti-HA). Protein expression was confirmed by Western blotting of cell lysates. (C) Mutations in Vpr affect Vpr-induced HLTF degradation. HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with a control vector or Vpr WT or mutant expression vector and the HLTF expression vector. At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. (D) Mutations in the Vpr HHCH domain have no effect on the dimerization of Vpx. HEK 293T cells were transfected with a control vector or WT or mutant Vpr-HA expression vector and WT or mutant Vpr-Flag. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were harvested, immunoprecipitated with anti-HA affinity matrix, and then analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody to detect Vpr-HA and anti-Flag antibody to detect Vpr-Flag (IP: anti-HA). (E) Effect of mutations in the HHCH domain on the subcellular localization of Vpr. HEK 293T cells were transfected with WT or mutant Vpr-HA. Then, nuclei and cytoplasm were extracted from cells. All samples were analyzed by Western blotting. Histone was used as the loading control of nuclei, and recombinant glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as the loading control of cytoplasm or total cell lysates. T, total cell lysates; N, nuclei; C, cytoplasm.

TPEN treatment inhibits Vpr-CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase functions.

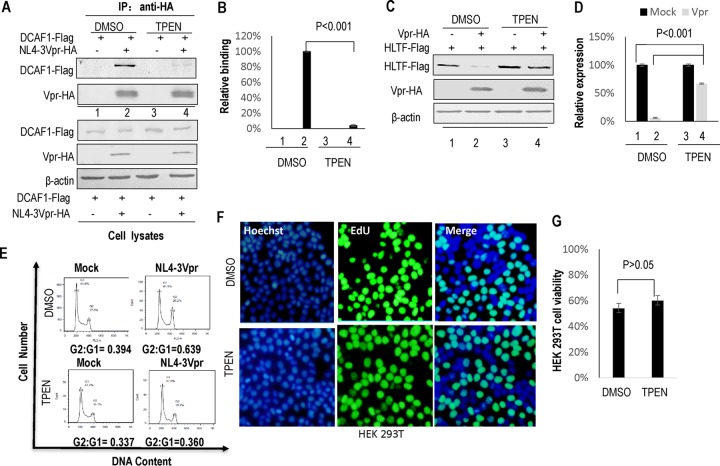

To determine whether zinc sequestration, rather than Vpr amino acid mutation, can affect Vpr-DCAF1 (CRL4-E3) assembly, we conducted coimmunoprecipitations using samples from transfected HEK 293T cells that had been cotransfected with an expression vector for Flag-DCAF1 plus a control vector or one of the various expression vectors for WT or mutant HA-Vpr. Our Western blotting data suggested that TPEN treatment significantly disrupted the Vpr-DCAF1 interaction (Fig. 9A, lane 4) compared to control DMSO treatment (Fig. 9A, lane 2). The ability of Vpr to bind DCAF1 was decreased by >90% in the presence of TPEN (Fig. 9B). This interaction was specific, since Flag-tagged DCAF1 was not detected in the absence of HA-Vpr expression (Fig. 9A, lanes 1 and 3). Further analysis revealed that TPEN treatment significantly inhibited the Vpr-mediated degradation of HLTF (Fig. 9B, lane 4, and C, lane 4) compared to control DMSO treatment (Fig. 9B, lane 2, and C, lane 2, P < 0.001 versus DMSO treatment). Previous reports have demonstrated that HIV-1 Vpr recruits DCAF1-CRL4 E3 ligase to induce cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase (43, 68–70). We observed that TPEN treatment also interfered with Vpr-triggered G2/M cell cycle arrest (Fig. 9E). To confirm that TPEN treatment does not affect cell the cycle directly, TPEN or DMSO was cocultured with HEK 293T cells for 48 h and then the cells were measured by 5-ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation assay. The HEK 293T cell viability was expressed as the percentages of EdU-positive cells in total Hoechst 33342-positive cells. The data showed that TPEN treatment did not affect the cell viability (Fig. 9E and G). Collectively, zinc binding is important for the interaction between Vpr and CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase as well as for Vpr-induced HLTF degradation and G2/M cell cycle arrest.

FIG 9.

TPEN affects Vpr-induced G2/M arrest and HLTF degradation. (A) Effect of TPEN on the relative binding activity of Vpr to DCAF1. HEK 293T cells were transfected with a control vector or Vpr-HA expression vector and DCAF1-HA. At 12 h posttransfection, a portion of the cell preparation was treated with DMSO or TPEN for 12 h and then detected by Western blotting with anti-Flag and anti-HA antibody to detect DDB1 and DCAF1 in the cell lysates. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA affinity matrix and then analyzed by Western blotting (IP: anti-HA). (B) The relative ability of WT Vpx to bind DCAF1 after DMSO (100%) or TPEN (n = 3, mean± SD) treatment. Error bars represent the standard deviation from triplicate experiments. P < 0.01, by ANOVA test. (C) TPEN affects Vpr-induced HLTF degradation. HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with a control vector or Vpr WT or mutant expression vector and HLTF expression vector. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were treated with DMSO or TPEN for 12 h. The cells were harvested and detected by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. β-Actin was used as the loading control. (D) The effect of DMSO or TPEN treatment on the relative expression of HLTF with or without (100%) Vpx expression is shown in the bar graph (n = 3, mean ± SD). Error bars represent the standard deviation from triplicate experiments. P < 0.01, by ANOVA test. (E) Effect of TPEN on the induction of G2/M arrest by Vpr. A control vector or Vpr expression vector and GFP expression vector were transfected into HEK 293T cells. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were treated with DMSO or TPEN for 12 h. They were then harvested, fixed with ice-cold ethanol, and then subjected to RNase A treatment and propidium iodide staining before flow cytometric analysis. The G2/G1 ratios were calculated by dividing the proportion of cells in G2/M by the proportion of cells in G1. Analysis of the flow cytometry data was carried out using FlowJo software. (F) The impact of TPEN on the cell proliferation of HEK 293T cells. TPEN or a negative control, DMSO, was cocultured with HEK 293T cells for 48 h, and cell proliferation was measured by a 5-ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation assay using an EdU assay kit. The HEK 293T cell viability was expressed as the percentage of EdU-positive cells (green cells) in total Hoechst 33342-positive cells (blue cells). All experiments were done in triplicate, and three independent experiments were performed. (G) Comparison of effect of DMSO or TPEN treatment on proliferation of HEK 293T cells.

DISCUSSION

Cullin family protein-associated E3 ligases are frequently utilized by viral accessory proteins to subvert the action of host proteins that interfere with HIV replication. SAMHD1 is a specific inhibitor of HIV/SIV infection in myeloid cells (53, 71). HIV-2 and SIV Vpx molecules recruit Cul4-DDB1-DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase to induce the degradation of SAMHD1 in order to promote viral replication in macrophages and dendritic cells. The molecular mechanism underlying the Vpx-mediated hijacking of Cul4-DDB1-DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase has not been fully characterized. The crystal structure of the Vpx-DCAF1-DDB1-SAMHD1 complex was found to include a novel zinc coordination motif (HHCC) in Vpx (8), but the role of this zinc-binding domain in Vpx function was not clear. We now report that the Vpx zinc-binding motif is indeed essential for Vpx function. In particular, the zinc-binding motif is critical for Vpx's interaction with DCAF1 and thus the assembly of the Vpx-CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (Fig. 3B and C). In contrast, mutations in this motif had little effect on Vpx's interaction with the substrate SAMHD1 (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, Vpx virion packaging was also not blocked by interference with the binding of Vpx to zinc (Fig. 5D). Thus, zinc binding is specifically required for the assembly of the Vpx-CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex.

Interestingly, the assembly of the Vpx-CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex is a particularly vulnerable step in Vpx function. Reducing the intracellular concentration of zinc with the membrane-permeable zinc chelator TPEN selectively inhibited CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase-dependent Vpx function by interrupting the Vpx-DCAF1 interaction without affecting the zinc-binding-dependent antiviral function of SAMHD1 (72) (Fig. 6B). Moreover, inhibition of Vpx function could be achieved by TPEN treatment without any detectable effect on cell viability (Fig. 4E and 5F).

The assembly of the cellular CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase, as indicated by the interaction between DCAF1 and DDB1, was also not affected by TPEN treatment (Fig. 7). Therefore, drug development based on zinc sequestration may be a promising strategy for HIV therapy.

Like Vpx, HIV-1 Vpr assembles with DCAF1 to form a CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase (43, 68, 69). Sequence analysis of Vpr proteins has revealed an HHCH motif that is similar to the HHCC motif in Vpx (Fig. 8A) (57, 58, 73, 74). This similarity raises the possibility that Vpr uses a similar zinc-dependent mechanism to recruit DCAF1. Indeed, mutations in the HHCH motif of HIV-1 Vpr disrupted Vpr's interaction with DCAF1 (Fig. 8B). As was true for Vpx, treatment with TPEN resulted in the disruption of the interaction between Vpr and DCAF1 (Fig. 9A). More importantly, Vpr function, as indicated by its ability to induce cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase, was inhibited by TPEN treatment (Fig. 9E).

Recently, it was reported that HIV-1 recruits the CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase to trigger HLTF degradation (44, 45). We have confirmed the ability of HIV-1 Vpr to trigger HLTF degradation in our system (Fig. 8C and 9C). The HIV-1 Vpr HHCH mutants were all defective in mediating HLTF degradation (Fig. 8C). Treatment with TPEN also blocked Vpr-induced HLTF degradation (Fig. 9C). Thus, the zinc-binding motifs that are highly conserved among diverse HIV/SIV Vpx (H39, H82, C87, and C89) and Vpr (H33, H71, C76, and H78) molecules play essential roles in viral CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase function.

Selective and efficient disruption of viral ubiquitin E3 ligase could be a novel antiviral strategy. Recently, we and other groups discovered that posttranslational modification by neddylation is critical for Vpx-CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase function (59–61). A neddylation-activating enzyme (NAE) inhibitor, MLN4924, inhibited the neddylation of Vpx-bound Cullin4 and blocked the Vpx-induced degradation of SAMHD1 proteins (60). However, since the neddylation modification is also essential for cellular CRL functions involved in cell cycle control (75, 76), signal transduction (77–79), and cell survival from DNA damage (62, 63, 80), using the neddylation inhibitor MLN4924 to inhibit viral replication may not be sufficiently selective (64). We now suggest that a highly conserved zinc-binding motif of the viral proteins Vpx and Vpr is responsible for the recruitment of the CRL4 (DCAF1) E3 ligase, and TPEN directly inhibits the binding of Vpx/Vpr and DCAF1 but not the cellular CRL4 E3 ligase assembly and might therefore be less toxic to host cells.

We have previously reported that zinc binding is important for HIV-1 Vif-CRL5/bovine immunodeficiency virus (BIV) Vif-CRL2 assembly and Vif-dependent APOBEC3 degradation (81–85). This study extends our understanding of viral proteins utilizing the zinc-binding motif to form Cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases. Future studies should address the following issues: (i) the structural and functional benefits of the zinc-binding domain in viral proteins for CRL E3 ligase assembly and (ii) whether zinc binding is critical and widespread among other viral proteins that also utilize CRL E3 ligase to counteract host factors. All in all, our studies shed light on a broadly conserved feature of Vpx/Vpr-CRL4 E3 ligase assembly that represents a novel target for antiviral drug discovery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

The plasmids pHuSAMHD1-HA, pHuSAMHD1-Flag, pMac-SAMHD1-HA, pVpr-HA, pDDB1-Flag, pDCAF1-HA, and pDCAF1-Flag were constructed as previously described (39). The SIVmac239ΔEnvΔVpx-GFP construct was a gift from J. Skowronski and has been previously described (37). pSIVmac239 Vpx-HA with an N-terminal HA tag was cloned into the VR1012 vector via the SalI and BglII sites. pVpr-H33A, pVpr-H71A, pVpr-C76S, pVpr-H78A, pVpx-H39A, pVpx-H82A, pVpx-C87S, and pVpx-C89S were constructed from pSIVmac-Vpx-HA/Flag or pNL4-3-Vpr-HA/Flag by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. The primers for all mutations are given in Table 1. The human HLTF sequence (NCBI reference sequence NM_001318935.1) was synthesized with an N-terminal Flag tag and subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 (+) vector via HindIII and NotI sites (Shanghai Generay Biotech Company).

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Primer sequence (5′–3′)a |

|---|---|

| Vpx-H39A | F: GGCGGTAAACGCCCTACCAAGGGAG |

| R: CTCCCTTGGTAGGGCGTTTACCGCC | |

| Vpx-H82A | F: GCTTTATTTATGGCTTGCAAGAAAGGCT |

| R: AGCCTTTCTTGCAAGCCATAAATAAAGC | |

| Vpx-C87S | F: CAAGAAAGGCTCTAGATGTCTAGGGG |

| R: CCCCTAGACATCTAGAGCCTTTCTTG | |

| Vpx-C89S | F: GAAAGGCTGTAGATCTCTAGGGGAAGGA |

| R: TCCTTCCCCTAGAGATCTACAGCCTTTC | |

| Vpr-H33A | F: GTGAAGCTGTTAGAGCTTTTCCTAGGATATGG |

| R: CCATATCCTAGGAAAAGCTCTAACAGCTTCAC | |

| Vpr-H71A | F: ACTGCTGTTTATCGCTTTCAGAATTGGGTG |

| R: CACCCAATTCTGAAAGCGATAAACAGCAGT | |

| Vpr-C76S | F: CATTTCAGAATTGGGAGTCGACATAGCAGAAT |

| R: ATTCTGCTATGTCGACTCCCAATTCTGAAATG | |

| Vpr-H78A | F: AATTGGGTGTCGAGCTAGCAGAATAGGCGT |

| R: ACGCCTATTCTGCTAGCTCGACACCCAATT |

F, forward primer; R, reverse primer (Shanghai Sangon Biotech Company).

Cell culture and antibodies.

HEK 293T cells (ATCC no. CRL-11268) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; HyClone) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA), 1 mM Na-pyruvate, and 100 μg/ml penicillin-streptomycin. Human monocytic cell line THP-1 (ATCC no. TIB-202) cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium (RPMI 1640; HyClone) with 10% FBS. All cell lines were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The following antibodies were used: mouse anti-HA monoclonal antibody (MAb; Covance; MMS-101R), rabbit anti-Vprbp polyclonal antibody (DCAF1; Shanghai Genomics; SG4220-28), mouse anti-Flag M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma; F1804), mouse anti-β-tubulin monoclonal antibody (Covance; MMS-410P), mouse anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (Sigma; A3853), and goat anti-mouse-SAMHD1 polyclonal antibody (Abcam; ab67820).

The following reagents were purchased: MG132 (catalog no. C2211; Sigma) and N,N,N′-tetrakis-(2′-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine (TPEN; catalog no. P4413; Sigma).

Transfection and coimmunoprecipitation.

DNA transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen; catalog no. 52887) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

For coimmunoprecipitation assays, HEK 293T cells were harvested at 48 h after transfection, washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), lysed in lysis buffer (150 mM Tris, pH 7.5, with 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and complete protease inhibitor cocktail tablets [(Roche]) at 4°C for 30 min, and then centrifuged for clarification at 10,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Precleared cell lysates were mixed with anti-HA antibody-conjugated agarose beads (Roche; catalog no. 190-119) or anti-Flag antibody-conjugated agarose beads (Sigma; A-2220) and incubated at 4°C for 3 h or overnight. Samples were then washed eight times with washing buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, with 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.05% Tween 20). The binding proteins were eluted with elution buffer (0.1 M glycine-HCl, pH 2.0), and the eluted materials were analyzed by Western blotting with appropriate antibodies.

Western blot analysis.

Briefly, cell lysates were harvested and boiled in 1× loading buffer (0.08 M Tris, pH 6.8, with 2.0% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.1 M dithiothreitol [DTT], and 0.2% bromophenol blue) and SDS-PAGE sample buffer followed by separation on a 10 to 12% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose (NC) membranes for Western blot analysis. Antibodies were diluted in PBS plus 1% milk followed by a corresponding alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated secondary antibody diluted 1:1,000. Proteins were visualized using nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP) obtained from Sigma. The Image J software was used to calculate the signal ratio of Western blotting data.

Cytotoxicity assays.

MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) (Promega; G4100) was used to assess the cytotoxicity of TPEN. Human monocytic THP-1 cells were stimulated with 100 ng/ml of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Promega; catalog no. V1171) in 96-well plates for 24 h and then treated with various doses of TPEN or DMSO for 48 h. HEK 293T cells were incubated in 96-well plates for 24 h and then treated with various doses of DMSO or TPEN for 12 h. For both cell lines, the supernatants were replaced with 100 μl of fresh culture medium. Fresh medium was added with 20 μl MTT solution (5 mg/ml) for 4 h at 37°C and then removed; 150 μl of DMSO was then added to the adherent PMA–THP-1 cells for 10 min at room temperature. Each cell sample was mixed using a pipette, and the absorbance was read at 490 nm. The value for the DMSO-treated control cell group was set to 100%.

Viral particle production and infection.

For Vpx-containing virus-like particle (VLP) packaging assays, HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with 1.2 μg of SIVmac239ΔEnvΔVpx-GFP, 0.2 μg of pCMV encoding VSV-G, and 0.5 μg of wild-type (WT) or mutant Vpx expression vector. At 48 h after transfection, the cell culture medium was harvested. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min in a Sorvall RT 6000B centrifuge and filtration through a 0.22-μm-pore-size membrane (Millipore). Virus particles were then concentrated by centrifugation through a 30% sucrose cushion at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C in a Sorvall Ultra80 ultracentrifuge. Cell lysates and precipitates containing viral particles were resuspended in lysis buffer (PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 and complete protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche]) and analyzed by Western blotting. To verify the infectivity of Vpx WT or mutant-containing VLPs, viral infectivity was determined as follows: THP-1 cells prepared in 12-well plates were induced with 100 ng/ml PMA for 24 h. After the medium was removed, the PMA-induced cells were infected with the same viral titer in a total volume of 1 ml of RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS per well and then incubated for 3 days under the same conditions. Viral infectivity in the PMA–THP-1 cells was examined using FACSCalibur flow cytometry (Becton, Dickinson) by counting the number of GFP-positive cells.

For the assays testing the effect of TPEN on Vpx packaging into VLPs, 1.2 μg of SIVmac239ΔEnvΔVpx-GFP, 0.2 μg of pCMV encoding VSV-G, and 0.5 μg of WT or mutant Vpx expression vector were cotransfected into HEK 293T cells. After 6 h, the supernatants were removed and the cells were treated with DMSO or TPEN (1.79 μM) for 48 h. The cells were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting. The supernatants were divided into two portions: one portion was used to infect PMA-treated THP-1 cells and then viral infectivity was measured by FACSCalibur flow cytometry, and the other was centrifuged at 35,000 × g for 3 h and resuspended in lysis buffer. Viral lysates were analyzed by Western blotting.

To investigate the role of TPEN in Vpx-dependent viral infection in PMA-treated macrophage-like THP-1 cells, 1.2 μg of SIVmac239ΔEnvΔVpx-GFP or SIVmac239ΔEnv-GFP and 0.2 μg of pCMV encoding VSV-G were cotransfected into HEK 293T cells for 48 h. The supernatants were harvested, filtered, and centrifuged at 35,000 × g for 3 h to purify the SIVmac-GFP or SIVmac ΔVpx-GFP VLPs. Meanwhile, the THP-1 cells were cultured in 100 nM PMA for 24 h and then treated with 1.4 μM TPEN or DMSO for 12 h. The treated cells were infected with equal titers of SIVmac-GFP or SIVmac ΔVpx-GFP VLPs for 3 days. The cells were then harvested, and the cell suspensions were divided into two equal portions: the portion used for viral infection of VLPs was analyzed by FACSCalibur flow cytometry, and the other was examined by Western blotting.

Chromatin fractionation assay.

HEK 293T cells were transfected with plasmids for 48 h and then divided into two equal portions: one portion was loaded in 120 μl 1× loading buffer for confirming the level of protein expression, while the other was prepared by scraping HEK 293T cells into cold PBS and resuspending them in 200 μl hypotonic lysis buffer (10 μM HEPES, pH 8.0, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 μM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, and protein inhibitors) at 4°C for 15 min. NP-40 was added to a final concentration of 0.5%, vortexed for 10 s, and centrifuged at 7,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant (cytoplasmic) was harvested and added to 40 μl 4× loading buffer. The nuclei were washed twice with cold PBS and restored in 100 μl 1× loading buffer.

Cell cycle analysis.

HEK 293T cells were transfected with 2 μg of pVpr-HA, or VR1012 as a negative control, and 0.3 μg of pcDNA3.1-GFP and then harvested at 48 h posttransfection. The cells were washed, then resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 60 min, and then fixed with 95% ethanol at 4°C overnight. Following RNase A (1 mg/ml) treatment, 10 μg/ml propidium iodide staining (2 × 106 cells/ml), and incubation in the dark on ice for 30 min, cells expressing the internal membrane-anchored GFP were analyzed for DNA content by FACSCalibur flow cytometry (Becton, Dickinson). At least 10,000 GFP-positive cells were analyzed to determine their distribution in the various phases of the cell cycle by using FlowJo software.

EdU incorporation assay.

The impact of coculture of TPEN on the proliferation of HEK 293T cells was measured by a 5-ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation assay using an EdU assay kit (Ribobio, Guangzhou, China), according to the manufacturer's instructions. After coculturing for 48 h, the cells in each well were labeled with 200 μM EdU for an additional 2 h at 37°C. At room temperature, the cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 30 min and then permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 20 min. After being washed with PBS three times, the cells were treated with 200 μl of 1× Apollo reaction cocktail for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the cells were stained with 200 μl of Hoechst 33342 for 30 min and visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The EdU-positive cells (green cells) were counted using Image-Pro Plus (IPP) 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA). The HEK 293T cell viability was expressed as the percentage of EdU-positive cells in total Hoechst 33342-positive cells (blue cells). All experiments were done in triplicate, and three independent experiments were performed.

Modeling of the zinc-binding domain assay.

Structure superposition was carried out using SSM (86) implemented in PDBeFold (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/msd-srv/ssm/) according to the information from the crystal structure of Vpx (8).

Data analysis.

The numerical and graphical analyses of all data were based on at least three repetitions of each experiment and are presented as means and standard deviations (SD). Differences among groups were analyzed by an analysis of variance (ANOVA) test (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant, and P values of >0.05 were considered nonsignificant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jacek Skowronski for critical reagents; Yuanyuan Li and Chunyan Dai for technical assistance; and Deborah McClellan for editorial assistance.

This work was supported in part by funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31600132), the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (no. 2012CB911100), the Chinese Ministry of Education (no. IRT1016), and Tianjin University.

X.-F.Y., W.W., and R.B.M. conceived and designed the overall project. H.W., H.G., J.S., Y.R., W.Z., W.G., W.Z., Z.L., and G.L. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. X.-F.Y. and W.W. wrote the paper with help from all authors.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wei W, Guo H, Ma M, Markham R, Yu XF. 2016. Accumulation of MxB/Mx2-resistant HIV-1 capsid variants during expansion of the HIV-1 epidemic in human populations. EBioMedicine 8:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sayah DM, Sokolskaja E, Berthoux L, Luban J. 2004. Cyclophilin A retrotransposition into TRIM5 explains owl monkey resistance to HIV-1. Nature 430:569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature02777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stremlau M, Owens CM, Perron MJ, Kiessling M, Autissier P, Sodroski J. 2004. The cytoplasmic body component TRIM5alpha restricts HIV-1 infection in Old World monkeys. Nature 427:848–853. doi: 10.1038/nature02343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstone DC, Ennis-Adeniran V, Hedden JJ, Groom HC, Rice GI, Christodoulou E, Walker PA, Kelly G, Haire LF, Yap MW, de Carvalho LP, Stoye JP, Crow YJ, Taylor IA, Webb M. 2011. HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase. Nature 480:379–382. doi: 10.1038/nature10623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goujon C, Moncorge O, Bauby H, Doyle T, Ward CC, Schaller T, Hue S, Barclay WS, Schulz R, Malim MH. 2013. Human MX2 is an interferon-induced post-entry inhibitor of HIV-1 infection. Nature 502:559–562. doi: 10.1038/nature12542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu X, Yu Y, Liu B, Luo K, Kong W, Mao P, Yu XF. 2003. Induction of APOBEC3G ubiquitination and degradation by an HIV-1 Vif-Cul5-SCF complex. Science 302:1056–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.1089591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheehy AM, Gaddis NC, Choi JD, Malim MH. 2002. Isolation of a human gene that inhibits HIV-1 infection and is suppressed by the viral Vif protein. Nature 418:646–650. doi: 10.1038/nature00939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwefel D, Groom HC, Boucherit VC, Christodoulou E, Walker PA, Stoye JP, Bishop KN, Taylor IA. 2014. Structural basis of lentiviral subversion of a cellular protein degradation pathway. Nature 505:234–238. doi: 10.1038/nature12815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neil SJ, Zang T, Bieniasz PD. 2008. Tetherin inhibits retrovirus release and is antagonized by HIV-1 Vpu. Nature 451:425–430. doi: 10.1038/nature06553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu XF, Yu QC, Essex M, Lee TH. 1991. The vpx gene of simian immunodeficiency virus facilitates efficient viral replication in fresh lymphocytes and macrophage. J Virol 65:5088–5091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen EA, Dehni G, Sodroski JG, Haseltine WA. 1990. Human immunodeficiency virus vpr product is a virion-associated regulatory protein. J Virol 64:3097–3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu XF, Matsuda M, Essex M, Lee TH. 1990. Open reading frame vpr of simian immunodeficiency virus encodes a virion-associated protein. J Virol 64:5688–5693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selig L, Pages JC, Tanchou V, Preveral S, Berlioz-Torrent C, Liu LX, Erdtmann L, Darlix J, Benarous R, Benichou S. 1999. Interaction with the p6 domain of the gag precursor mediates incorporation into virions of Vpr and Vpx proteins from primate lentiviruses. J Virol 73:592–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Accola MA, Bukovsky AA, Jones MS, Gottlinger HG. 1999. A conserved dileucine-containing motif in p6(gag) governs the particle association of Vpx and Vpr of simian immunodeficiency viruses SIV(mac) and SIV(agm). J Virol 73:9992–9999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henderson LE, Sowder RC, Copeland TD, Benveniste RE, Oroszlan S. 1988. Isolation and characterization of a novel protein (X-ORF product) from SIV and HIV-2. Science 241:199–201. doi: 10.1126/science.3388031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paxton W, Connor RI, Landau NR. 1993. Incorporation of Vpr into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virions: requirement for the p6 region of gag and mutational analysis. J Virol 67:7229–7237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu X, Conway JA, Kim J, Kappes JC. 1994. Localization of the Vpx packaging signal within the C terminus of the human immunodeficiency virus type 2 Gag precursor protein. J Virol 68:6161–6169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu XF, Ito S, Essex M, Lee TH. 1988. A naturally immunogenic virion-associated protein specific for HIV-2 and SIV. Nature 335:262–265. doi: 10.1038/335262a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato K, Misawa N, Iwami S, Satou Y, Matsuoka M, Ishizaka Y, Ito M, Aihara K, An DS, Koyanagi Y. 2013. HIV-1 Vpr accelerates viral replication during acute infection by exploitation of proliferating CD4+ T cells in vivo. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003812. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herate C, Vigne C, Guenzel CA, Lambele M, Rouyez MC, Benichou S. 2016. Uracil DNA glycosylase interacts with the p32 subunit of the replication protein A complex to modulate HIV-1 reverse transcription for optimal virus dissemination. Retrovirology 13:26. doi: 10.1186/s12977-016-0257-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malim MH, Emerman M. 2008. HIV-1 accessory proteins—ensuring viral survival in a hostile environment. Cell Host Microbe 3:388–398. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell BJ, Hirsch VM. 1997. Vpr of simian immunodeficiency virus of African green monkeys is required for replication in macaque macrophages and lymphocytes. J Virol 71:5593–5602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noel RJ Jr, Kumar A. 2007. SIV Vpr evolution is inversely related to disease progression in a morphine-dependent rhesus macaque model of AIDS. Virology 359:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guyader M, Emerman M, Montagnier L, Peden K. 1989. VPX mutants of HIV-2 are infectious in established cell lines but display a severe defect in peripheral blood lymphocytes. EMBO J 8:1169–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kappes JC, Conway JA, Lee SW, Shaw GM, Hahn BH. 1991. Human immunodeficiency virus type 2 vpx protein augments viral infectivity. Virology 184:197–209. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90836-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marcon L, Michaels F, Hattori N, Fargnoli K, Gallo RC, Franchini G. 1991. Dispensable role of the human immunodeficiency virus type 2 Vpx protein in viral replication. J Virol 65:3938–3942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kyei GB, Cheng X, Ramani R, Ratner L. 2015. Cyclin L2 is a critical HIV dependency factor in macrophages that controls SAMHD1 abundance. Cell Host Microbe 17:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mangeot PE, Duperrier K, Negre D, Boson B, Rigal D, Cosset FL, Darlix JL. 2002. High levels of transduction of human dendritic cells with optimized SIV vectors. Mol Ther 5:283–290. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goujon C, Riviere L, Jarrosson-Wuilleme L, Bernaud J, Rigal D, Darlix JL, Cimarelli A. 2007. SIVSM/HIV-2 Vpx proteins promote retroviral escape from a proteasome-dependent restriction pathway present in human dendritic cells. Retrovirology 4:2. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibbs JS, Lackner AA, Lang SM, Simon MA, Sehgal PK, Daniel MD, Desrosiers RC. 1995. Progression to AIDS in the absence of a gene for vpr or vpx. J Virol 69:2378–2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirsch VM, Sharkey ME, Brown CR, Brichacek B, Goldstein S, Wakefield J, Byrum R, Elkins WR, Hahn BH, Lifson JD, Stevenson M. 1998. Vpx is required for dissemination and pathogenesis of SIV(SM) PBj: evidence of macrophage-dependent viral amplification. Nat Med 4:1401–1408. doi: 10.1038/3992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belshan M, Ratner L. 2003. Identification of the nuclear localization signal of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 Vpx. Virology 311:7–15. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6822(03)00093-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kappes JC, Parkin JS, Conway JA, Kim J, Brouillette CG, Shaw GM, Hahn BH. 1993. Intracellular transport and virion incorporation of vpx requires interaction with other virus type-specific components. Virology 193:222–233. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahalingam S, Van Tine B, Santiago ML, Gao F, Shaw GM, Hahn BH. 2001. Functional analysis of the simian immunodeficiency virus Vpx protein: identification of packaging determinants and a novel nuclear targeting domain. J Virol 75:362–374. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.1.362-374.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo H, Wei W, Wei Z, Liu X, Evans SL, Yang W, Wang H, Guo Y, Zhao K, Zhou JY, Yu XF. 2013. Identification of critical regions in human SAMHD1 required for nuclear localization and Vpx-mediated degradation. PLoS One 8:e66201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pancio HA, Vander Heyden N, Ratner L. 2000. The C-terminal proline-rich tail of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 Vpx is necessary for nuclear localization of the viral preintegration complex in nondividing cells. J Virol 74:6162–6167. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.13.6162-6167.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srivastava S, Swanson SK, Manel N, Florens L, Washburn MP, Skowronski J. 2008. Lentiviral Vpx accessory factor targets VprBP/DCAF1 substrate adaptor for cullin 4 E3 ubiquitin ligase to enable macrophage infection. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000059. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bergamaschi A, Ayinde D, David A, Le Rouzic E, Morel M, Collin G, Descamps D, Damond F, Brun-Vezinet F, Nisole S, Margottin-Goguet F, Pancino G, Transy C. 2009. The human immunodeficiency virus type 2 Vpx protein usurps the CUL4A-DDB1 DCAF1 ubiquitin ligase to overcome a postentry block in macrophage infection. J Virol 83:4854–4860. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00187-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei W, Guo H, Han X, Liu X, Zhou X, Zhang W, Yu XF. 2012. A novel DCAF1-binding motif required for Vpx-mediated degradation of nuclear SAMHD1 and Vpr-induced G2 arrest. Cell Microbiol 14:1745–1756. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu Y, Zhou X, Barnes CO, DeLucia M, Cohen AE, Gronenborn AM, Ahn J, Calero G. 2016. The DDB1-DCAF1-Vpr-UNG2 crystal structure reveals how HIV-1 Vpr steers human UNG2 toward destruction. Nat Struct Mol Biol 23:933–940. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He J, Choe S, Walker R, Di Marzio P, Morgan DO, Landau NR. 1995. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral protein R (Vpr) arrests cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle by inhibiting p34cdc2 activity. J Virol 69:6705–6711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Re F, Braaten D, Franke EK, Luban J. 1995. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr arrests the cell cycle in G2 by inhibiting the activation of p34cdc2-cyclin B. J Virol 69:6859–6864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Belzile JP, Duisit G, Rougeau N, Mercier J, Finzi A, Cohen EA. 2007. HIV-1 Vpr-mediated G2 arrest involves the DDB1-CUL4AVPRBP E3 ubiquitin ligase. PLoS Pathog 3:e85. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hrecka K, Hao C, Shun MC, Kaur S, Swanson SK, Florens L, Washburn MP, Skowronski J. 2016. HIV-1 and HIV-2 exhibit divergent interactions with HLTF and UNG2 DNA repair proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:E3921–E3930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605023113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lahouassa H, Blondot ML, Chauveau L, Chougui G, Morel M, Leduc M, Guillonneau F, Ramirez BC, Schwartz O, Margottin-Goguet F. 2016. HIV-1 Vpr degrades the HLTF DNA translocase in T cells and macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:5311–5316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600485113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laguette N, Bregnard C, Hue P, Basbous J, Yatim A, Larroque M, Kirchhoff F, Constantinou A, Sobhian B, Benkirane M. 2014. Premature activation of the SLX4 complex by Vpr promotes G2/M arrest and escape from innate immune sensing. Cell 156:134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou X, DeLucia M, Ahn J. 2016. SLX4-SLX1 protein-independent down-regulation of MUS81-EME1 protein by HIV-1 viral protein R (Vpr). J Biol Chem 291:16936–16947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.721183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeLucia M, Mehrens J, Wu Y, Ahn J. 2013. HIV-2 and SIVmac accessory virulence factor Vpx down-regulates SAMHD1 enzyme catalysis prior to proteasome-dependent degradation. J Biol Chem 288:19116–19126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.469007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahn J, Hao C, Yan J, DeLucia M, Mehrens J, Wang C, Gronenborn AM, Skowronski J. 2012. HIV/simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) accessory virulence factor Vpx loads the host cell restriction factor SAMHD1 onto the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex CRL4DCAF1. J Biol Chem 287:12550–12558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.340711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwefel D, Boucherit VC, Christodoulou E, Walker PA, Stoye JP, Bishop KN, Taylor IA. 2015. Molecular determinants for recognition of divergent SAMHD1 proteins by the lentiviral accessory protein Vpx. Cell Host Microbe 17:489–499. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berger A, Sommer AF, Zwarg J, Hamdorf M, Welzel K, Esly N, Panitz S, Reuter A, Ramos I, Jatiani A, Mulder LC, Fernandez-Sesma A, Rutsch F, Simon V, Konig R, Flory E. 2011. SAMHD1-deficient CD14+ cells from individuals with Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome are highly susceptible to HIV-1 infection. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002425. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hrecka K, Hao C, Gierszewska M, Swanson SK, Kesik-Brodacka M, Srivastava S, Florens L, Washburn MP, Skowronski J. 2011. Vpx relieves inhibition of HIV-1 infection of macrophages mediated by the SAMHD1 protein. Nature 474:658–661. doi: 10.1038/nature10195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laguette N, Sobhian B, Casartelli N, Ringeard M, Chable-Bessia C, Segeral E, Yatim A, Emiliani S, Schwartz O, Benkirane M. 2011. SAMHD1 is the dendritic- and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature 474:654–657. doi: 10.1038/nature10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bonifati S, Daly MB, St Gelais C, Kim SH, Hollenbaugh JA, Shepard C, Kennedy EM, Kim DH, Schinazi RF, Kim B, Wu L. 2016. SAMHD1 controls cell cycle status, apoptosis and HIV-1 infection in monocytic THP-1 cells. Virology 495:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yan J, Kaur S, DeLucia M, Hao C, Mehrens J, Wang C, Golczak M, Palczewski K, Gronenborn AM, Ahn J, Skowronski J. 2013. Tetramerization of SAMHD1 is required for biological activity and inhibition of HIV infection. J Biol Chem 288:10406–10417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.443796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koharudin LM, Wu Y, DeLucia M, Mehrens J, Gronenborn AM, Ahn J. 2014. Structural basis of allosteric activation of sterile alpha motif and histidine-aspartate domain-containing protein 1 (SAMHD1) by nucleoside triphosphates. J Biol Chem 289:32617–32627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.591958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang C, de Silva S, Wang JH, Wu L. 2012. Co-evolution of primate SAMHD1 and lentivirus Vpx leads to the loss of the vpx gene in HIV-1 ancestor. PLoS One 7:e37477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fregoso OI, Ahn J, Wang C, Mehrens J, Skowronski J, Emerman M. 2013. Evolutionary toggling of Vpx/Vpr specificity results in divergent recognition of the restriction factor SAMHD1. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003496. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hofmann H, Norton TD, Schultz ML, Polsky SB, Sunseri N, Landau NR. 2013. Inhibition of CUL4A neddylation causes a reversible block to SAMHD1-mediated restriction of HIV-1. J Virol 87:11741–11750. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02002-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wei W, Guo H, Liu X, Zhang H, Qian L, Luo K, Markham RB, Yu XF. 2014. A first-in-class NAE inhibitor, MLN4924, blocks lentiviral infection in myeloid cells by disrupting neddylation-dependent Vpx-mediated SAMHD1 degradation. J Virol 88:745–751. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02568-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nekorchuk MD, Sharifi HJ, Furuya AK, Jellinger R, de Noronha CM. 2013. HIV relies on neddylation for ubiquitin ligase-mediated functions. Retrovirology 10:138. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ma T, Chen Y, Zhang F, Yang CY, Wang S, Yu X. 2013. RNF111-dependent neddylation activates DNA damage-induced ubiquitination. Mol Cell 49:897–907. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li T, Guan J, Huang Z, Hu X, Zheng X. 2014. RNF168-mediated H2A neddylation antagonizes ubiquitylation of H2A and regulates DNA damage repair. J Cell Sci 127:2238–2248. doi: 10.1242/jcs.138891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brown JS, Jackson SP. 2015. Ubiquitylation, neddylation and the DNA damage response. Open Biol 5:150018. doi: 10.1098/rsob.150018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wei W, Guo H, Gao Q, Markham R, Yu XF. 2014. Variation of two primate lineage-specific residues in human SAMHD1 confers resistance to N terminus-targeted SIV Vpx proteins. J Virol 88:583–591. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02866-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baldauf HM, Pan X, Erikson E, Schmidt S, Daddacha W, Burggraf M, Schenkova K, Ambiel I, Wabnitz G, Gramberg T, Panitz S, Flory E, Landau NR, Sertel S, Rutsch F, Lasitschka F, Kim B, Konig R, Fackler OT, Keppler OT. 2012. SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 infection in resting CD4(+) T cells. Nat Med 18:1682–1687. doi: 10.1038/nm.2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rice GI, Bond J, Asipu A, Brunette RL, Manfield IW, Carr IM, Fuller JC, Jackson RM, Lamb T, Briggs TA, Ali M, Gornall H, Couthard LR, Aeby A, Attard-Montalto SP, Bertini E, Bodemer C, Brockmann K, Brueton LA, Corry PC, Desguerre I, Fazzi E, Cazorla AG, Gener B, Hamel BC, Heiberg A, Hunter M, van der Knaap MS, Kumar R, Lagae L, Landrieu PG, Lourenco CM, Marom D, McDermott MF, van der Merwe W, Orcesi S, Prendiville JS, Rasmussen M, Shalev SA, Soler DM, Shinawi M, Spiegel R, Tan TY, Vanderver A, Wakeling EL, Wassmer E, Whittaker E, Lebon P, Stetson DB, Bonthron DT, Crow YJ. 2009. Mutations involved in Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome implicate SAMHD1 as regulator of the innate immune response. Nat Genet 41:829–832. doi: 10.1038/ng.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tan L, Ehrlich E, Yu XF. 2007. DDB1 and Cul4A are required for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr-induced G2 arrest. J Virol 81:10822–10830. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01380-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wen X, Duus KM, Friedrich TD, de Noronha CM. 2007. The HIV1 protein Vpr acts to promote G2 cell cycle arrest by engaging a DDB1 and Cullin4A-containing ubiquitin ligase complex using VprBP/DCAF1 as an adaptor. J Biol Chem 282:27046–27057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hrecka K, Gierszewska M, Srivastava S, Kozaczkiewicz L, Swanson SK, Florens L, Washburn MP, Skowronski J. 2007. Lentiviral Vpr usurps Cul4-DDB1[VprBP] E3 ubiquitin ligase to modulate cell cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:11778–11783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702102104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.St Gelais C, Wu L. 2011. SAMHD1: a new insight into HIV-1 restriction in myeloid cells. Retrovirology 8:55. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-8-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhu C, Gao W, Zhao K, Qin X, Zhang Y, Peng X, Zhang L, Dong Y, Zhang W, Li P, Wei W, Gong Y, Yu XF. 2013. Structural insight into dGTP-dependent activation of tetrameric SAMHD1 deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase. Nat Commun 4:2722. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chakrabarti L, Guyader M, Alizon M, Daniel MD, Desrosiers RC, Tiollais P, Sonigo P. 1987. Sequence of simian immunodeficiency virus from macaque and its relationship to other human and simian retroviruses. Nature 328:543–547. doi: 10.1038/328543a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Laguette N, Rahm N, Sobhian B, Chable-Bessia C, Munch J, Snoeck J, Sauter D, Switzer WM, Heneine W, Kirchhoff F, Delsuc F, Telenti A, Benkirane M. 2012. Evolutionary and functional analyses of the interaction between the myeloid restriction factor SAMHD1 and the lentiviral Vpx protein. Cell Host Microbe 11:205–217. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bornstein G, Ganoth D, Hershko A. 2006. Regulation of neddylation and deneddylation of cullin1 in SCFSkp2 ubiquitin ligase by F-box protein and substrate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:11515–11520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603921103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hershko A. 2005. The ubiquitin system for protein degradation and some of its roles in the control of the cell division cycle. Cell Death Differ 12:1191–1197. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Milhollen MA, Traore T, Adams-Duffy J, Thomas MP, Berger AJ, Dang L, Dick LR, Garnsey JJ, Koenig E, Langston SP, Manfredi M, Narayanan U, Rolfe M, Staudt LM, Soucy TA, Yu J, Zhang J, Bolen JB, Smith PG. 2010. MLN4924, a NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor, is active in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma models: rationale for treatment of NF-kappaB-dependent lymphoma. Blood 116:1515–1523. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-272567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Read MA, Brownell JE, Gladysheva TB, Hottelet M, Parent LA, Coggins MB, Pierce JW, Podust VN, Luo RS, Chau V, Palombella VJ. 2000. Nedd8 modification of cul-1 activates SCF(beta(TrCP))-dependent ubiquitination of IkappaBalpha. Mol Cell Biol 20:2326–2333. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.7.2326-2333.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]