ABSTRACT

HIV can spread by both cell-free and cell-to-cell transmission. Here, we show that many of the amino acid changes in Env that are close to the CD4 binding pocket can affect HIV replication. We generated a number of mutant viruses that were unable to infect T cells as cell-free viruses but were nevertheless able to infect certain T cell lines as cell-associated viruses, which was followed by reversion to the wild type. However, the activation of JAK-STAT signaling pathways caused the inhibition of such cell-to-cell infection as well as the reversion of multiple HIV Env mutants that displayed differences in their abilities to bind to the CD4 receptor. Specifically, two T cell activators, interleukin-2 (IL-2) and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), both capable of activation of JAK-STAT pathways, were able to inhibit cell-to-cell viral transmission. In contrast, but consistent with the above result, a number of JAK-STAT and mTOR inhibitors actually promoted HIV-1 transmission and reversion. Hence, JAK-STAT signaling pathways may differentially affect the replication of a variety of HIV Env mutants in ways that differ from the role that these pathways play in the replication of wild-type viruses.

IMPORTANCE Specific alterations in HIV Env close to the CD4 binding site can differentially change the ability of HIV to mediate infection for cell-free and cell-associated viruses. However, such differences are dependent to some extent on the types of target cells used. JAK-STAT signaling pathways are able to play major roles in these processes. This work sheds new light on factors that can govern HIV infection of target cells.

KEYWORDS: HIV-1, Env mutant, cell-associated viruses, cell dependence, reversion

INTRODUCTION

HIV-1 infection of cells can be efficiently established by free virus or directly via cell-cell contact, both involving the binding of the HIV gp120 protein to the cellular CD4 receptor and either the CCR5 or CXCR4 coreceptor (1–3). It has been reported that cell-to-cell transmission is more physiologically relevant and efficient although cell-free HIV may be used to initiate new infections in tissue culture (4–7).

HIV-1 entry into target cells is believed to be a multistep and complex process initiated by the envelope protein gp120 binding to cell surface CD4, triggering conformational changes of gp120, followed by a second-step interaction between gp120 and either CXCR4 or CCR5, resulting in fusion between the viral envelope and the cellular plasma membrane (8). In addition to viral gp120 and other viral proteins, several host cell components, including intrinsic immune factors (9) and histocompatibility antigens, can influence HIV infectivity (10, 11). However, some viral factors can also counteract innate host defense mechanisms (12). It has also been reported that HIV can under some circumstances enter target cells via a CD4/coreceptor-independent mechanism (13–18), potentially broadening the spectrum of cells that HIV is able to infect.

HIV has very high genetic variability and evolves quickly. The viral population in an infected individual is highly heterogeneous due to the error-prone nature of reverse transcriptase and may contain diverse viral swarms, termed quasispecies, that are similar but genetically distinct (19–21). This heterogeneity includes large numbers of mutations, including those responsible for drug resistance and also for the replicative fitness of HIV, which are critical for transmission and pathogenesis. Furthermore, a large proportion of HIVs may be defective due to the spontaneous generation of lethal mutations that can then be spread through recombination and rescue of drug resistance phenotypes (22–25). Indeed, viral recombination has been shown to occur between complementary defective viral forms, resulting in increased viral replicative fitness and improved capacity for transmission. In one case, a highly infectious virus-producing cell line was reported to contain five copies of the HIV genome, none of which was infectious individually; recombination was shown to be responsible for the generation of infectious viral progeny (26). Increased efficiency of HIV transmission may also increase the likelihood that target cells become infected by multiple virions, thereby increasing the likelihood of viral recombination (21–26) and helping to facilitate viral escape from selection pressure produced by both the immune system and the drugs used in HIV treatment (21, 27, 28).

Both viral and cellular factors are involved in transmission; e.g., the viral envelope protein not only is responsible for viral entry but also modulates certain functions of host cells that facilitate infection. Mutations in viral envelope proteins may affect viral infectivity through different mechanisms. For example, certain mutations, including those at positions G367R and D368R in the CD4 binding site (CD4bs) of gp120, may cause the virus to become noninfectious (24, 29–31). However, the mutants can be rescued by superinfection and recombination or even by spontaneous back-mutation to wild type in some T cell lines. In addition, HIV that has been pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSV-G) cannot successfully infect resting T cells (32).

The study of Env-mutated viruses that are able to mediate infection only by cell-to-cell transmission may help to clarify some of the mechanisms involved. We have recently reported that a G367R mutation at the CD4 binding site within Env resulted in noninfectiousness for cell-free viruses but did not abrogate infection of certain T cell lines via cell-cell transmission; moreover, such infection often led to reversion of the G367R substitution (33). We have now investigated additional mutations within Env that are located at the CD4 binding site and have focused on two important motifs, notably the GGDPE region at amino acid positions 366 to 370 and the bridging sheet at positions 426 to 431. We now show that G367R, D368R, M426R, and W427V each resulted in noninfectivity in culture as cell-free viruses but that cell-to-cell transmission of HIV into some T lymphocyte-derived cell lines could still occur and that this led to phenotypic reversions to wild-type virus in each case (experimental procedures illustrated in Fig. 1). Activation of the Janus kinase (JAK) and the signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathways, by agents such as interleukin-2 (IL-2) and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) inhibited this cell-associated viral transmission, while JAK-STAT inhibitors promoted both the transmission and reversion events described. Thus, cell-to-cell transmission of HIV can involve both viral and cellular factors, and, in particular, the activation of JAK-STAT signaling pathways may be able to inhibit this mode of infection. Conceivably, molecules that activate JAK-STAT signaling might be able to play a role in the control of HIV infection.

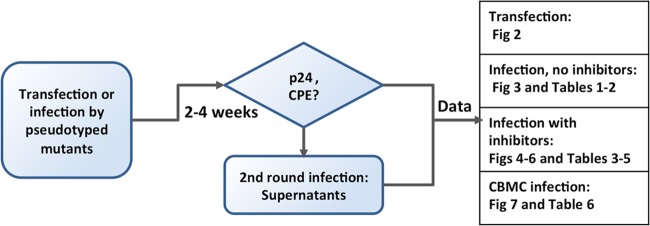

FIG 1.

Flow chart of the general experimental procedures performed with HIV Env mutants. Twelve Env mutants were generated based on pNL4-3 for transfection in MT2, MT4, and C8166 cells. VSV-G pseudotyped mutant viruses were prepared for infection in MT2, MT4, C8166, and CBMC cells in the presence or absence of reagents targeting cell signaling. pNL4-3 was used as a control.

RESULTS

Env mutations in the CD4 binding region result in noninfectiousness by cell-free virus but allow reversions following cell-to-cell transmission in some infected T cell lines.

The deficit caused by the Env mutant D368R in regard to cell-free infection has been well studied (29–31). However, it is not known whether mutations at other positions that surround the CD4 binding site might result in a similar phenotype. Here, we employed three T cell lines, MT2, MT4, and C8166, that express both the CD4 and CXCR4 receptors to investigate the effects of mutations within the GGDPE motif or the bridging sheet on viral infection. MT2 and MT4 cells can behave differently with regard to support of viral replication of viruses that are mutated at the CD4 binding site even though both cell lines are highly sensitive to wild-type infection, as reported previously (33).

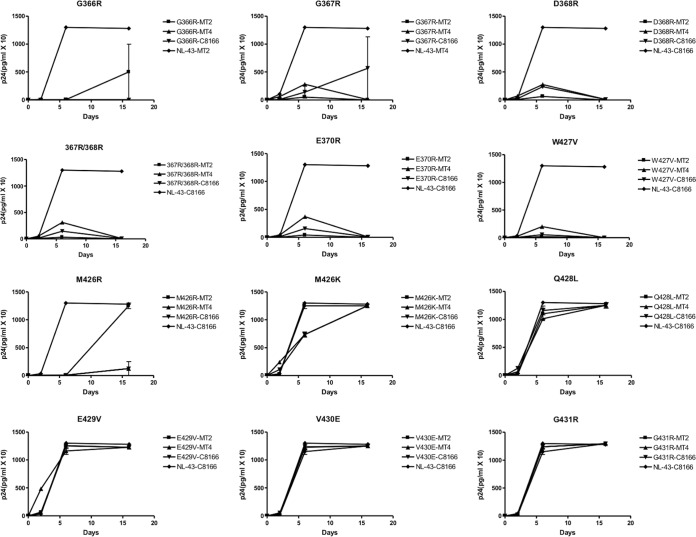

DNA samples of 12 different HIV Env mutants and wild-type HIV-1 were separately transfected in duplicate into MT2, MT4, and C8166 cells to synthesize viral proteins and to lead to viral replication. p24 values and cytopathic effects (CPE) were monitored to assess whether infection had occurred, and culture fluids were used to initiate a new round of infection. As shown in Fig. 2, the p24 values resulting from the transfections of the proviral DNA containing the G366R, G367R, D368R, 367R/368R, G370R, or W427V mutation commonly resulted in an initial slight increase in values in each of MT2, MT4, and C8166 cells, followed by a decrease in the second week. However, both the G366R and G367R mutations yielded successful infections in C8166 cells after 2 weeks, and the recovered viruses were infectious in a subsequent round; sequencing confirmed that reversion to a wild-type virus had occurred. The M426R substitution resulted in delayed replication in MT4 and C8166 cells but less so in MT2 cells. Replication of M426K viruses was better than that of M426R viruses in each of MT2, MT4, and C8166 cell lines, suggesting that the change to an R residue was more deleterious than a K substitution. Replication of viruses containing a substitution at position Q428L, E429V, V430E, or G431R was comparable to that of wild-type virus, and the culture fluids derived from these transfections were infectious over second rounds of infection. In summary, among mutations in the GGDPE motif, the infectivity of viruses containing G366R, D368R, and G370R was the most compromised while viruses containing M426K and M426R were significantly affected among those with the bridging sheet mutations, with the W427V mutant having the lowest infectivity.

FIG 2.

Growth curves of HIV Env-mutated viruses after transfection of three T cell lines. A total of 200,000 cells were transfected with viral DNA (~0.8 μg for the mutants, 0.1 μg for pNL4-3) at 37°C and grown in 24-well plates in duplicate. The cultures were fed every 3 days, and the supernatants were monitored at the times indicated for p24 levels and for levels of infectiousness at day 16 after infection. CPE was also read at day 16 after infection.

Pseudotyping.

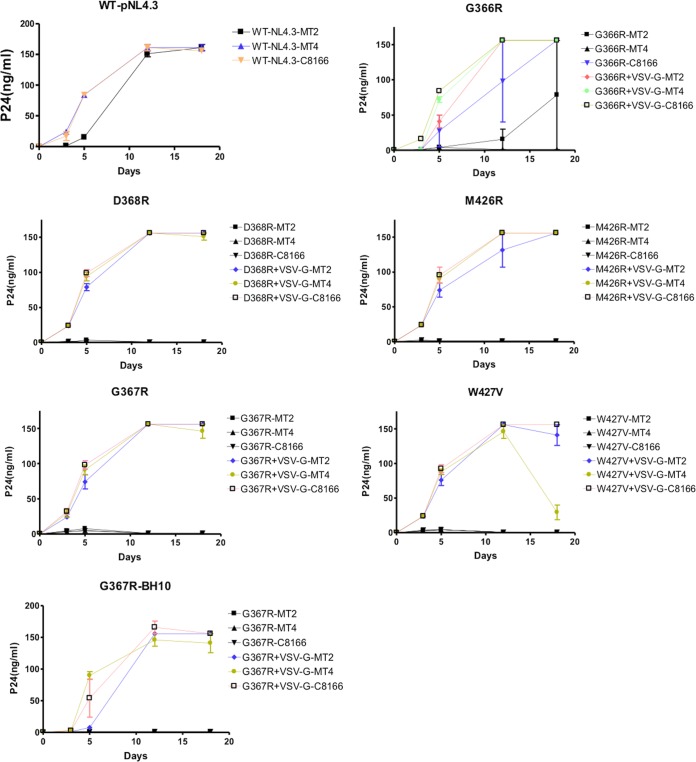

The transfection experiments did not provide adequate data due to the low transfection efficiency of cells in suspension and related factors. Therefore, additional experiments were carried out using the pseudotyped viruses. Based on the results shown in Fig. 2, the mutations that potentially affected infectiousness were further investigated in the context of VSV-G pseudotyped viruses. The G366R virus was partially infectious as free virus for MT2 and C8166 cells, with increases in p24 values being observed over 2 to 3 weeks (Fig. 3). Similarly, each of the G367R, D368R, M426R, and W427V constructs was noninfectious as cell-free virus in each of the MT2, MT4, and C8166 cell lines, but the use of VSV-G pseudotyped viruses led to recovery of infection after 2 weeks in MT2 and C8166 cells but not in MT4 cells (Fig. 3 and summarized in Table 1). We note that successful infection with mutated viruses does not necessarily mean that viral progeny will be infectious even though the infection curves of mutated viruses can look similar to those of wild-type viruses performed at infection doses that are 1,000-fold lower than those used for the mutants. For this reason, cell-free progeny needs to be evaluated for infectiousness over a second round. It should be noted that p24 values in MT4 culture fluids began to decline within 2 weeks after infection and that these culture fluids were not infectious when employed as cell-free virus. These results indicate that the infected cells produced noninfectious progeny that would disappear slowly over time due to outgrowth of uninfected cells. Pseudotyped viruses were used in most subsequent experiments.

FIG 3.

Infection curves of Env mutants and VSV-G pseudotyped viruses. A total of 105 cells were infected with the mutant viruses (~50 ng of p24 per 105 cells, 50 pg for pNL4-3) at 37°C for 3 h, washed, and grown in 24-well plates in triplicate. p24 values were determined at 3- to 7-day intervals.

TABLE 1.

Phenotypic reversion of HIV Env mutants in T cell linesa

| Mutant (pseudotyping) | MT2 cells |

MT4 cells |

C8166 cells |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPE | Amt of p24 in SN (ng/ml) | CPE | Amt of p24 in SN (ng/ml) | CPE | Amt of p24 in SN (ng/ml) | |

| G366R | +/−b | +/− | − | <0.1 | + | >100 |

| G366R (VSV-G) | + | >100 | − | <0.1 | + | >100 |

| G367R | − | <0.1 | − | <0.1 | − | <0.1 |

| G367R (VSV-G) | + | >100 | − | <0.1 | + | >100 |

| D368R | − | <0.1 | − | <0.1 | − | <0.1 |

| D368R (VSV-G) | + | >100 | − | <0.1 | + | >100 |

| M426K | + | >100 | + | >100 | + | >100 |

| M426R | − | <0.1 | − | <0.1 | − | <0.1 |

| M426R (VSV-G) | + | >100 | − | <0.1 | + | >100 |

| W427V | − | <0.1 | − | <0.1 | − | <0.1 |

| W427V (VSV-G) | + | >100 | − | <0.1 | + | >100 |

| Q428L | + | >100 | + | >100 | + | >100 |

| E429V | + | >100 | + | >100 | + | >100 |

| V430E | + | >100 | + | >100 | + | >100 |

| G431R | + | >100 | + | >100 | + | >100 |

A total of 100,000 cells were infected with mutated viruses (∼50 ng of p24) at 37°C for 3 h, washed, and grown in 24-well plates in triplicate. The cultures were fed every 3 days, and the supernatants (SN) were monitored for infectivity at day 16 after infection. Cytopathic effect (CPE) and p24 values were also read at day 16 after infection. The results obtained with the Q428L, E429V, V430E, and G431R mutants followed from transfection of DNA into cells.

+/−, only one sample of three was positive.

The effects of G367R and D368R are similar in regard to viral infection and reversion.

The growth curves of the G367R-containing virus in MT2, MT4, and C8166 cells are displayed in Fig. 3 and summarized in Table 2. Few differences were observed in growth or reversion rates regardless of whether the G367R virus had been generated from HxB2D or pNL4-3 clones (Fig. 3 and Table 2), suggesting that genetic viral background did not have a major impact on the role of the G367R substitution in the context of viral entry.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of G367R reversion generated from HxB2D or pNL4-3 clones in T cell lines

| Cell line | No. of cells per well | G367R-HxB2D reversiona |

G367R-pNL4-3 reversiona |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPE | SN infectivity | CPE | SN infectivity | ||

| MT2 | 105 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 |

| 5 × 103 | 1/4 | 2/4 | 2/4 | 2/4 | |

| MT4 | 105 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 1/3 | 1/3 |

| 5 × 103 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | |

| C8166 | 105 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 |

| 5 × 103 | 2/4 | 3/4 | 3/4 | 3/4 | |

G367R-HxB2D and G367R-pNL4-3 are VSV-G pseudotyped viruses. Cells were infected with the mutant viruses (∼50 ng of p24 per 105 cells) at 37°C for 3 h, washed, and grown in 24-well plates (105 cells) in triplicate or in 96-well plates (5 × 103 cells) in quadruplicate. The cultures were fed every 3 to 5 days, and supernatants (SN) were monitored for infectivity at day 16 after infection. Cytopathic effect (CPE) and p24 values were evaluated at day 16 after infection. Values represent the number of positive samples/the number of tested samples.

In order to decrease the probability that reversion would occur during the first round of infection, we deliberately employed a limited number of cells in some of our experiments. Our results show that viral growth rates and rates of reversion were similar and cell type dependent for both the G367R and D368R substitutions, with phenotypic reversion occurring rapidly and frequently over 2 to 3 weeks in MT2 and C8166 cells but hardly at all in MT4 cells under controlled conditions (Fig. 4A and B). Reversion was closely related to the number of cells and quantity of virus used for infection, with faster reversions occurring when higher numbers of cells were employed. Sequencing confirmed that the G367R mutations in all the samples that were infectious as cell-free viruses had reverted to wild type while the R residue of D368R was mutated to Q (CGA to CAA).

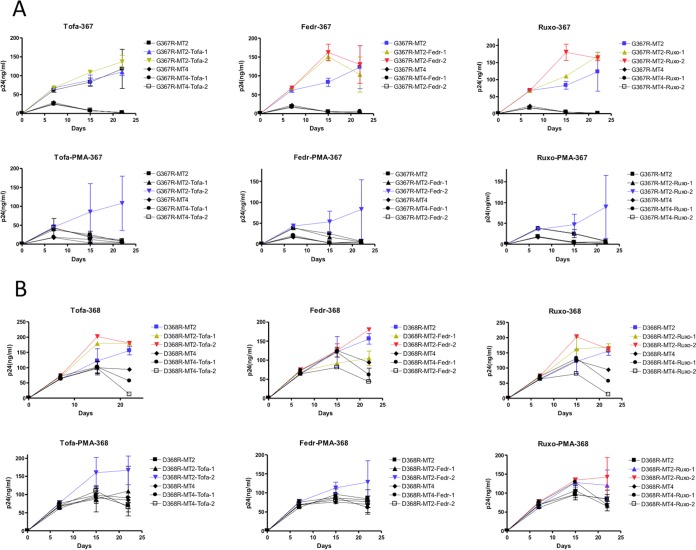

FIG 4.

The effects of PMA and JAK inhibitors on the growth of the VSV-G pseudotyped Env mutants G367R (A) and D368R (B). Cells were infected with the mutant viruses (~50 ng of p24 per 105 cells) at 37°C for 3 h, washed, and grown in 96-well plates (5 ×103 cells/well) in the presence or absence of PMA (0.1 ng/ml) and/or JAK inhibitors. p24 values were monitored at intervals of 6 to 7 days. Tofa-1, tofacitinib 10 nM; Tofa-2, tofacitinib 100 nM; Fedr-1, fedratinib 10 nM; Fedr-2, fedratinib 100 nM; Ruxo-1, ruxolitinib 10 nM; Ruxo-2, ruxolitinib 100 nM.

G367R virus and D368R reversions are inhibited by PMA and IL-2 but promoted by JAK-STAT and mTOR inhibitors.

To investigate potential mechanisms of reversion, we wished to determine what the effect of reagents that affect cell signaling might be. Because both PMA and IL-2 affect the JAK-STAT and mTOR signaling pathways, we included inhibitors that act against JAK-STAT and mTOR, respectively.

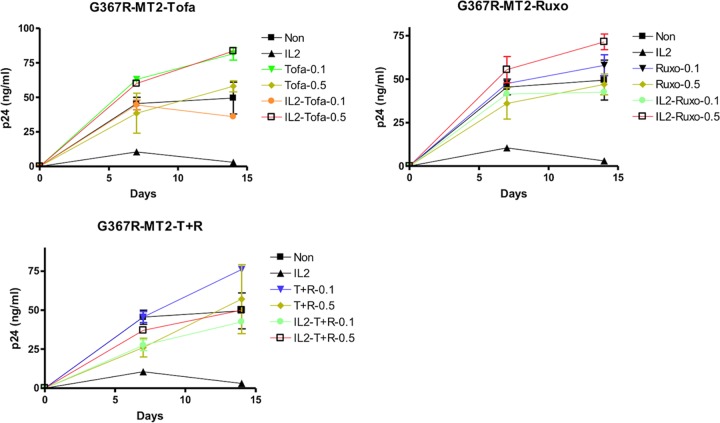

Three JAK inhibitors were employed in our experiments: tofacitinib that inhibits JAK3 (34), fedratinib that inhibits JAK2, and ruxolitinib that is specific for JAK1/2 (35). All three inhibitors were able to increase the phenotypic reversion of the mutants at submicromolar concentrations. Growth of the G367R or D368R virus in MT2 cells was inhibited in the presence of PMA or IL-2. However, this inhibition was counteracted by JAK inhibitors (Fig. 4 and 5).

FIG 5.

The effects of IL-2 and JAK inhibitors on the growth of the VSV-G pseudotyped Env mutant G367R. MT2 cells were infected with the mutant virus (~50 ng of p24 per 105 cells) at 37°C for 3 h, washed, and grown in 96-well plates (5 × 103 cells/well) in the presence or absence of IL-2 (20 IU/ml) and/or JAK inhibitors. p24 values were measured at intervals of 7 days. Tofa-0.1, tofacitinib 0.1 μM; Tofa-0.5, tofacitinib 0.5 μM; Ruxo-0.1, ruxolitinib 0.1 μM; Ruxo-0.5, ruxolitinib 0.5 μM; T+R-0.1, tofacitinib and ruxolitinib 0.1 μM; T+R-0.5, tofacitinib and ruxolitinib 0.5 μM.

In MT2 cells, JAK inhibitors were able to reverse the inhibitory effect of PMA and IL-2 in a dose-dependent way, with 0.1 ng/ml of PMA preventing both G367R and D368R reversion. The JAK inhibitors tofacitinib and ruxolitinib at 10 or 100 nM were more efficient than fedratinib at reversing the inhibitory effect of PMA (Table 3). The presence of 100 nM ruxolitinib increased the toxicity of PMA for MT2 cells (Table 3). Higher concentrations of JAK inhibitors were needed to reverse the inhibitory effect of IL-2 (20 IU/ml) (Fig. 5 and Table 4). The combination of tofacitinib and ruxolitinib did not lead to synergy in regard to reversion but was toxic for MT2 cells (Table 4). None of the JAK inhibitors was able to enhance G367R and D368R growth or reversion in MT4 cells (Fig. 5), which were not sensitive to JAK inhibitors, even at concentrations as high as 1.0 μM (not shown).

TABLE 3.

The effects of PMA and JAK inhibitors on G367R and D368R reversion in MT2 cells

| JAK inhibitor and concn (nM) | PMA (ng/ml) | G367R reversiona |

D368R reversiona |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPE | SN infectivity | CPE | SN infectivity | ||

| None | 0 | 4/8 | 4/8 | 6/8 | 6/8 |

| 0.1 | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0/8 | |

| Tofacitinib | |||||

| 100 | 0 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| 10 | 0 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| 100 | 0.1 | 2/4 | 2/4 | 2/4 | 2/4 |

| 10 | 0.1 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| Fedratinib | |||||

| 100 | 0 | 2/4 | 2/4 | 3/4 | 3/4 |

| 10 | 0 | 2/4 | 2/4 | 2/4 | 2/4 |

| 100 | 0.1 | 1/4 | 1/4 | 1/4 | 1/4 |

| 10 | 0.1 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| Ruxolitinib | |||||

| 100 | 0 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 3/4 | 3/4 |

| 10 | 0 | 3/4 | 3/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| 100 | 0.1 | ND | 1/4 | ND | 1/4 |

| 10 | 0.1 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 1/4 | 1/4 |

G367R and D368R were VSV-G pseudotyped viruses. MT2 cells were infected with the mutant viruses (∼50 ng of p24 per 105 cells) at 37°C for 3 h, washed, and grown in 96-well plates at 5 × 103 cells/well. The cultures were fed every 3 to 5 days, and the supernatants (SN) were checked for infectivity at day 16 after infection. Cytopathic effect (CPE) and p24 values were evaluated at day 16 after infection. Values represent the number of positive samples/the number of tested samples. ND, not determined because of toxicity to MT2 cells.

TABLE 4.

The effects of IL-2 and JAK inhibitors on G367R reversion in MT2 cells

| JAK inhibitor and concn (nM) | IL-2 (IU/ml) | G367R reversiona |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| CPE | SN infectivity | ||

| None | 0 | 2/8 | 2/8 |

| 20 | 0/8 | 0/8 | |

| Tofacitinib | |||

| 500 | 0 | 1/4 | 1/4 |

| 100 | 0 | 1/4 | 1/4 |

| 500 | 20 | 1/4 | 1/4 |

| 100 | 20 | 1/4 | 1/4 |

| Ruxolitinib | |||

| 500 | 0 | 2/4 | 2/4 |

| 100 | 0 | 1/4 | 1/4 |

| 500 | 20 | 3/4 | 3/4 |

| 100 | 20 | 1/4 | 1/4 |

| Tofacitinib plus ruxolitinib | |||

| 500 | 0 | 1/4 | 1/4 |

| 100 | 0 | 1/4 | 1/4 |

| 500 | 20 | 0/4b | 0/4 |

| 100 | 20 | 1/4 | 1/4 |

G367R was a VSV-G pseudotyped virus. MT2 cells were infected with the mutant virus (∼50 ng of p24 per 105 cells) at 37°C for 3 h, washed, and grown in 96-well plates at 5 × 103 cells/well. The cultures were fed every 3 to 5 days, and the supernatants (SN) were checked for infectivity at day 16 after infection. Cytopathic effect (CPE) and p24 values were evaluated at day 16 after infection. Tofacitinib and ruxolitinib were used together in some studies at 100 μM or 500 nM. Values represent the number of positive samples/the number of tested samples.

The combination of both inhibitors at 500 nM and IL-2 was toxic to MT2 cells.

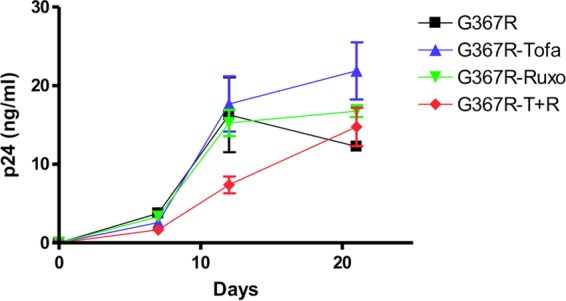

The effect of the JAK-STAT and mTOR signaling pathways on the reversion of G367R were also studied using STAT and mTOR inhibitors. Our results confirmed that both 5,15-diphenylporphyrin (5,15-DPP), specific for STAT3, and rapamycin, specific for mTOR, can promote G367R growth and reversion. Although JAK inhibitors did not enhance G367R mutant growth and reversion in MT4 cells, both STAT3 and mTOR inhibitors enhanced G367R mutant growth and reversion in MT4 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6 and Table 5). Both 5,15-DPP at concentrations above 50 nM and rapamycin above 1 nM promoted G367R reversion in MT4 cells. These results indicate that constitutive STAT and mTOR activities are elevated in MT4 cells and can be inhibited by STAT inhibitors and rapamycin but not by JAK inhibitors.

FIG 6.

The effects of STAT and mTOR inhibitors on growth of the VSV-G pseudotyped Env mutant G367R. MT4 cells were infected with the mutant virus (~10 ng of p24 per 105 cells) at 37°C for 3 h, washed, and grown in 96-well plates (5 × 104 cells/well) in the presence or absence of 5,15-DPP (5, 50, or 500 nM) or rapamycin (0.1, 1, or 10 nM). p24 values were monitored at intervals of 6 to 7 days.

TABLE 5.

The effects of STAT and mTOR inhibitors on G367R reversion in MT4 cells

| Inhibitor and concn (nM) | G367R reversiona |

|

|---|---|---|

| CPE | SN infectivity | |

| None | 0/8 | 0/8 |

| 5,15-DPP | ||

| 5 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| 50 | 1/4 | 1/4 |

| 500 | 1/4 | 1/4 |

| Rapamycin | ||

| 0.1 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| 1 | 1/4 | 1/4 |

| 10 | 2/4b | 2/4b |

G367R was a VSV-G pseudotyped virus. MT4 cells were infected with the mutant viruses (∼10 ng of p24 per 105 cells) at 37°C for 3 h, washed, and grown in 96-well plates at 5 × 104 cells/well. The cultures were fed every 3 to 5 days, and the supernatants (SN) were checked for infectivity at day 21 after infection. Cytopathic effect (CPE) and p24 values were read at day 16 after infection. Values represent the number of positive samples/the number of tested samples.

The results were statistically significant by a t test in comparison to results in the absence of inhibitor (P < 0.05).

G367R virus reversions are promoted by JAK inhibitors in CBMCs.

We also wished to determine whether G367R reversion would take place in primary cells as well as in cell lines. For this purpose, cord blood mononuclear cells (CBMCs) were infected and grown in the presence of IL-2 as well as in the presence or absence of JAK inhibitors. The growth of CBMCs and infection of HIV require the presence of IL-2 in the culture medium. VSV-G pseudotyped G367R mutants can infect CBMCs and produce p24 at levels about 10 times less than the level in MT2 cells. However, reversion in this circumstance was not observed over 3 weeks of infection. The JAK inhibitor tofacitinib at a concentration of 100 nM promoted the reversion of G367R, but this was not accomplished when ruxolitinib or a combination of both inhibitors (the concentration is inhibitory to the replication of CBMCs [data not shown]) was studied (Fig. 7 and Table 6). Two of four samples showed reversion on the basis of p24 increases and the infectivity of supernatants after 21 days of G367R infection, a result attributable to the ability of JAK inhibitors to counteract IL-2 because IL-2 activates JAK3 and because tofacitinib is its specific inhibitor. Even more significantly, coculture of infected CBMCs and MT2 cells resulted in infection of the latter and of JAK inhibitor-treated samples over 21 days, as monitored by p24 values. Reversion of mutated HIV-1 eventually occurred, and the progeny were able to initiate new rounds of infection as cell-free virus over 2 to 3 weeks (Table 6). Viral reversion occurred in all the samples that were cocultured with CBMCs in the presence of tofacitinib. Reversion also occurred in cases treated with the combination of tofacitinib-ruxolitinib (4/4) and with the majority of samples (3/4) treated with ruxolitinib. CPE appeared earlier in the presence of tofacitinib than when both tofacitinib and ruxolitinib together or ruxolitinib alone was present, and p24 values became positive as well. In contrast, no viral growth occurred in samples cocultured with CBMCs after 21 days without JAK inhibitors; therefore, CPE and positive p24 values were not found. Coculture with C8166 cells yielded similar results (data not shown). However, JAK inhibitors at the higher concentrations inhibited the replication of CBMCs; the reversion of G367R was not observed in these cells when they were tested alone although reversion could still be observed after coculture (data not shown).

FIG 7.

The effects of IL-2 and JAK inhibitors on growth of the VSV-G pseudotyped Env mutant G367R in cord blood mononuclear cells (CBMCs). CBMCs were infected with the mutant virus (~50 ng of p24 per 107 cells) at 37°C for 3 h, washed, and grown in 24-well plates in quadruplicate (5 × 106 cells/well). The cultures were grown in the presence of 100 nM of either tofacitinib, ruxolitinib, or a combination of both and fed every 5 to 7 days. Fresh CBMCs (5 × 106) were added at day 7. p24 values were checked at intervals of 6 to 7 days. Tofa, tofacitinib; Ruxo, ruxolitinib; T+R, tofacitinib and ruxolitinib.

TABLE 6.

The effects of JAK inhibitors on G367R reversion in CBMCs

| JAK inhibitor (100 nM) | G367R reversion in CBMCs (SN infectivity)a | G367R reversion in CBMC and MT2 coculturea |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| CPE | SN infectivity | ||

| None | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| Tofacitinib | 2/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| Ruxolitinib | 0/4 | 3/4 | 3/4 |

| Tofacitinib plus ruxolitinib | 0/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 |

G367R was a VSV-G pseudotyped virus. CBMCs were infected with the mutant virus (∼50 ng of p24 per 107 cells) at 37°C for 3 h, washed, and grown in 24-well plates in quadruplicate at 5 × 106 cells/well. IL-2 (10 IU/ml) was used to support the growth of CBMCs. A total of 5 × 106 fresh CBMCs were added at day 7, and the supernatants (SN) or cocultures were assessed for infectivity of MT2 cells at day 21 after infection. CPE and p24 values were evaluated at day 21 after infection of MT2 cells. Tofacitinib and ruxolitinib were used together in some studies at 100 nM. Values represent the number of positive samples/the number of tested samples.

DISCUSSION

Many viruses can spread significantly by direct cell-cell contact (36), but some, such as HIV, can efficiently infect target cells via both cell-free and cell-to-cell routes. Most HIV studies have relied on the use of cell-free virus for infection due to convenience even though it is clear that cell-associated transmission is also important (37, 38), with some reports indicating that infection via cell-free versus cell-associated routes might occur at different speeds and efficiencies (39). A recent report indicates that cell-to-cell transmission is required to trigger apoptosis of infected CD4+ T cells (40). It is also true that many primary HIV isolates are unable to mediate cell-free infection until adapted in culture. Possibly, a number of mutations may contribute to the enhancement of cell-free infection, but these may be difficult to ascertain when isolates of unknown background are studied.

In contrast, it is easier to follow the evolution of HIV mutated variants that possess a defined background. We have recently reported that the HIV Env mutant G367R is useful for the study of cell-to-cell infection since transmission can occur only via cell-associated virus but not free virus, a characteristic that may also be true for D368R and other mutations that affect CD4 binding (29–31). Accordingly, we mutated several sites within Env that closely contact the CD4 receptor molecule. Our results confirm that both G366R and M426K may have altered the CD4 binding pocket less than G367R and D368R. Thus, viruses containing these mutations possessed severely impaired cell-free infectivity but retained viability. However, mutations that drastically change the CD4 binding pocket can erode cell-free infectiousness, and we have now extended these findings by showing that each of M426R, G367R, D368R, and W427V mutations resulted in a loss of cell-free but not cell-associated infectivity. In each case, the amino acid substitutions would induce a change in the CD4 binding pocket due to the hydrophilic nature of the R residue or to hydrophobicity in the case of a V residue, thus significantly decreasing CD4 binding ability. The infectiousness of the mutants as cell-associated forms seems to be cell type dependent, mainly for MT2, C8166, and SupT1 cells, providing evidence of the role of host factors other than receptors in this process. Moreover, viral replication and reversion were modulated by the presence of cytokines, T cell activators, and JAK inhibitors.

HIV entry begins as the viral particle binds to CD4 to induce the conformational change of the Env protein, prior to binding to a coreceptor that triggers the fusion of the viral envelope and the cellular plasma membrane (8). The viral particle can also enter the cell by endocytosis (41). Many viruses, including retroviruses such as HIV-1, use endocytosis as an entry route (41, 42) although several other factors can enhance viral entry in this circumstance (43).

Our mutants have enabled us to show that cell-associated entry can involve different phenotypes of HIV. We have previously shown that the replication and reversion of the G367R mutant can be inhibited by the endocytosis inhibitor chlorpromazine (33), suggesting that this mutant may use endocytosis as a primary entry route since wild-type HIV infection in activated T cells cannot be inhibited by endocytosis inhibitors. It is possible that although our Env mutants suffer from impaired binding to CD4, they can attain cell entry through endocytosis. As in other cases of cell-associated viral transmission, cells infected by the mutants did not show any cytopathic effects but died as the mutants reverted to a wild-type phenotype alongside an increase in p24 values, indicating that low-level replication of the mutants had occurred. The efficiency of endocytosis is a cell-dependent phenomenon.

Certain T cell lines such as MT2, C8166, and SupT1 support the replication of the viral mutants better than MT4, Jurkat, and PM-1 cells, as studied here and as reported recently (33). This may involve differences in the responsiveness to PMA and IL-2 that can inhibit the replication of the mutated viruses and a possibly differential role for the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, as suggested by the effects of the JAK inhibitors tofacitinib and ruxolitinib. The fact that STAT and mTOR inhibitors enhanced G367R replication and promoted reversion in MT4 cells further supports a role for the JAK-STAT and mTOR signaling pathways in HIV cell-to-cell transmission. The activation of the JAK-STAT pathway can also be modulated by immunological status. As shown here, both PMA and IL-2 can affect the replication of the mutated viruses, and immune activation can trigger the immune response of the host to inhibit virus replication.

One of the consequences of virus infection is the release of interferon (IFN) that can also stimulate the JAK-STAT pathway and trigger the expression of multiple interferon-stimulated genes. Although the functions of many activated genes are not clear, several can inhibit both viral infection and replication. A class of interesting molecules includes the interferon-induced transmembrane (IFITM) proteins that have been reported to inhibit infection by a broad spectrum of viruses (44–50). This may result from a decrease of viral transmission into cells, involving decreased fusion between viral envelopes and cellular membranes. IFITM proteins can inhibit viral membrane and cellular endosomal or lysosomal vesicles from participating in membrane fusion. The T cell lines used in our experiments have different levels of IFITM proteins (45), e.g., low levels in MT2 and SupT1 cells but high levels in other cell lines. MT4 cells may have elevated constitutive JAK and STAT activity. However, STAT, but not JAK, activity is uniquely sensitive to inhibitors (Fig. 4 and 6). This may explain why our Env mutants such as G367R can replicate and revert in MT2 but not in MT4 cells as well as why replication of the mutants is inhibited in the presence of PMA or IL-2, either of which can induce the expression of IFN and subsequently of IFITM proteins.

The inhibitory effect of IFITM proteins on Env mutants may be more severe than that on wild-type viruses because the ability of the mutated viruses to bind to CD4 is impaired, resulting in a preference for endocytosis. There is an endocytic signal in IFITM proteins responsible for antiviral activity (51). Interestingly, prolonged passage of HIV in IFITM-expressing T lymphocytes leads to emergence of Env mutants that overcome IFITM restriction. G367E is a resistance mutation selected in the presence of elevated levels of IFITM protein 1 (52, 53), implying that mutations including G367R at the CD4 binding site may help HIV-1 to evade IFITM protein-mediated inhibition.

Of course, multiple factors may be involved in the PMA-mediated reversion of Env mutants, in part because PMA can itself have multiple effects and can activate several signaling pathways, especially over several weeks in culture. There is also a potential for feedback loops to become involved. We used PMA in our studies because it was previously shown to inhibit the reversion of the G367R mutation. PKC may also play a role in this process, as reported previously (33). Although PMA is not a specific JAK activator, it can activate JAK-STAT signaling pathways, and JAK/STAT inhibitors can affect the reversion rates of various mutants (e.g., G367R) in the presence of either PMA or IL-2.

However, the roles that the JAK-STAT and mTOR signaling pathways play in HIV infection may be much more complex. HIV replication in T lymphocytes requires T cells to be activated and continuously needs IL-2 stimulation. Thus, inhibition of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway will inhibit HIV replication. In agreement with this, JAK inhibitors were recently reported to inhibit HIV replication in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and macrophages (54, 55). In contrast to many other viral infections, the activation of the immune system cannot easily inhibit HIV spread within a host. Notably, PMA and IL-2 cannot inhibit the replication of wild-type HIV in T cells or cell lines. Our results indicate that several mutants that affect CD4 binding react differently than wild-type virus. The replication of the resultant viruses was inhibited in the presence of PMA or IL-2. Inhibition of the JAK-STAT and mTOR signaling pathways promoted the replication and reversion of the mutants. The activation of T cells inhibited the spread and replication of these mutated viruses. However, further study of the differential influences of JAK and STAT constituents, e.g., JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and STAT1 to STAT5, will be necessary. It is also relevant that HIV infection has been reported to affect the activation of STAT pathways (56, 57).

Our observations suggest that the CD4 binding ability of HIV-1 provides a mechanism of viral escape from inhibition by host immune activation and promotes cell-free infection. Env-mutated viruses are not sensitive to either neutralizing antibodies or to entry inhibitors (33, 58, 59). However, such viruses may be sensitive to inhibition by nonspecific immune factors, e.g., IFN released by infected cells and activated immune cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

MT2, MT4, and C8166 cells were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. All cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 1% l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin under 5% CO2 at 37°C. 293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (Invitrogen). Culture medium was changed every 3 days. Cord blood mononuclear cells (CBMCs) were obtained through our Hospital Department of Obstetrics following standard procedures.

Viruses.

BH10 and pNL4-3 were used as wild-type HIV-1. Wild-type viruses and Env mutants that contained a mutation in the CD4 binding site of gp120 were generated and replicated in T cell lines by transfection of proviral plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 as recommended by the manufacturer (Invitrogen). Env mutant viruses were also generated by transfection of proviral plasmids in 293T cells for further analysis. In some cases, pVPack-VSV-G (Stratagene), which encodes the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) envelope glycoprotein, was used at a ratio of 1:1 to HIV to produce VSV-G pseudotyped viruses. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the viruses were harvested, analyzed for p24, and stored at −80°C. Wild-type virus stocks were amplified in MT2 cells or in CBMCs. Virus stocks were kept at −70°C until use.

HIV Env mutants.

Viruses mutated at the Env CD4 binding site were generated by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis as reported previously (24). Two important motifs forming the CD4 binding site (30), GGDPE at amino acid positions 366 to 370 and amino acids 426 to 431 of the bridging sheet, were mutated. Twelve mutants were obtained in total, including G366R, G367R, D368R, G367R/D368R, and G370R in the GGDPE motif and M426(R/K), W427V, Q428L, E429V, V430E, and G431R in the bridging sheet. G367R was generated in both HxB2D and pNL4-3 to compare the effects of this substitution in different viral backbones. All the other mutants were built into pNL4-3 only. Standard sequencing was performed using an ABI genetic analyzer (according to the manufacturer's protocol) with plasmids or DNA obtained from samples of second-round infections by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) amplification.

Viral infection.

Cells were infected with mutated or wild-type virus for 3 h at 37°C. Cells were washed three times with RPMI 1640 medium immediately following infection to remove unbound virus and were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium and split into wells at appropriate concentrations. Cytopathic effects (CPE) were monitored daily by microscopy, and supernatants were evaluated for p24 antigen at 3- to 7-day intervals (bioMérieux, Netherlands).

Viral infection by coculture.

Donor cells infected with VSV-G pseudotyped viruses with gp120 containing G367R were mixed at various dilutions with target cells to grow in single wells. CPE and levels of p24 were monitored in order to assess both infection efficiency and reversion.

Chemicals.

Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), the STAT inhibitor 5,15-diphenylporphyrin (5,15-DPP, specific to STAT3), and rapamycin, which serves as an inhibitor of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), were purchased from Cayman Chemical, Inc. (Ann Arbor, MI). IL-2 was from Roche Diagnostics (Laval, Quebec). The JAK inhibitor tofacitinib, which targets JAK3, was purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX) while fedratinib, which is specific for JAK2, was obtained from ApexBio Technology (Hsinchu City, Taiwan). Ruxolitinib, which inhibits both JAK1 and -2, was obtained from LC Labs (Woburn, MA).

A flow chart of the general experimental procedure is illustrated in Fig. 1 to indicate periods of treatment and observation as well as information on data collection and analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Susan Germinario and Estrella Moyal for technical and secretarial assistance, respectively.

This research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sattentau QJ, Weiss RA. 1988. The CD4 antigen: physiological ligand and HIV receptor. Cell 52:631–633. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90397-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feng Y, Broder CC, Kennedy PE, Berger EA. 1996. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science 272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder CC, Feng Y, Kennedy PE, Murphy PM, Berger EA. 1996. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science 272:1955–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sourisseau M, Sol-Foulon N, Porrot F, Blanchet F, Schwartz O. 2007. Inefficient human immunodeficiency virus replication in mobile lymphocytes. J Virol 81:1000–1012. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01629-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen P, Hubner W, Spinelli MA, Chen BK. 2007. Predominant mode of human immunodeficiency virus transfer between T cells is mediated by sustained Env-dependent neutralization-resistant virological synapses. J Virol 81:12582–12595. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00381-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carr JM, Hocking H, Li P, Burrell CJ. 1999. Rapid and efficient cell-to-cell transmission of human immunodeficiency virus infection from monocyte-derived macrophages to peripheral blood lymphocytes. Virology 265:319–329. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato H, Orenstein J, Dimitrov D, Martin M. 1992. Cell-to-cell spread of HIV-1 occurs within minutes and may not involve the participation of virus particles. Virology 186:712–724. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90038-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klasse PJ. 2012. The molecular basis of HIV entry. Cell Microbiol 14:1183–1192. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01812.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lama J, Planelles V. 2007. Host factors influencing susceptibility to HIV infection and AIDS progression. Retrovirology 4:52. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geijtenbeek TB, Torensma R, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GC, Adema GJ, van Kooyk Y, Figdor CG. 2000. Identification of DC-SIGN, a novel dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3 receptor that supports primary immune responses. Cell 100:575–585. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaslow RA, Carrington M, Apple R, Park L, Munoz A, Saah AJ, Goedert JJ, Winkler C, O'Brien SJ, Rinaldo C, Detels R, Blattner W, Phair J, Erlich H, Mann DL. 1996. Influence of combinations of human major histocompatibility complex genes on the course of HIV-1 infection. Nat Med 2:405–411. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon V, Bloch N, Landau NR. 2015. Intrinsic host restrictions to HIV-1 and mechanisms of viral escape. Nat Immunol 16:546–553. doi: 10.1038/ni.3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman TL, LaBranche CC, Zhang W, Canziani G, Robinson J, Chaiken I, Hoxie JA, Doms RW. 1999. Stable exposure of the coreceptor-binding site in a CD4-independent HIV-1 envelope protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:6359–6364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vidricaire G, Gauthier S, Tremblay MJ. 2007. HIV-1 infection of trophoblasts is independent of gp120/CD4 Interactions but relies on heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J Infect Dis 195:1461–1471. doi: 10.1086/515576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuyama AC, Hong F, Saiman Y, Wang C, Ozkok D, Mosoian A, Chen P, Chen BK, Klotman ME, Bansal MB. 2010. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 infects human hepatic stellate cells and promotes collagen I and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression: implications for the pathogenesis of HIV/hepatitis C virus-induced liver fibrosis. Hepatology 52:612–622. doi: 10.1002/hep.23679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dumonceaux J, Nisole S, Chanel C, Quivet L, Amara A, Baleux F, Briand P, Hazan U. 1998. Spontaneous mutations in the env gene of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 NDK isolate are associated with a CD4-independent entry phenotype. J Virol 72:512–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haim H, Strack B, Kassa A, Madani N, Wang L, Courter JR, Princiotto A, McGee K, Pacheco B, Seaman MS, Smith AB III, Sodroski J. 2011. Contribution of intrinsic reactivity of the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins to CD4-independent infection and global inhibitor sensitivity. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002101. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolchinsky P, Mirzabekov T, Farzan M, Kiprilov E, Cayabyab M, Mooney LJ, Choe H, Sodroski J. 1999. Adaptation of a CCR5-using, primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate for CD4-independent replication. J Virol 73:8120–8126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domingo E, Holland JJ. 1997. RNA virus mutations and fitness for survival. Annu Rev Microbiol 51:151–178. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyerhans A, Cheynier R, Albert J, Seth M, Kwok S, Sninsky J, Morfeldt-Manson L, Asjo B, Wain-Hobson S. 1989. Temporal fluctuations in HIV quasispecies in vivo are not reflected by sequential HIV isolations. Cell 58:901–910. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90942-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quan Y, Brenner BG, Dascal A, Wainberg MA. 2008. Highly diversified multiply drug-resistant HIV-1 quasispecies in PBMCs: a case report. Retrovirology 5:43. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Del Portillo A, Tripodi J, Najfeld V, Wodarz D, Levy DN, Chen BK. 2011. Multiploid inheritance of HIV-1 during cell-to-cell infection. J Virol 85:7169–7176. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00231-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onafuwa-Nuga A, Telesnitsky A. 2009. The remarkable frequency of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genetic recombination. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 73:451–480. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00012-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quan Y, Liang C, Brenner BG, Wainberg MA. 2009. Multidrug-resistant variants of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) can exist in cells as defective quasispecies and be rescued by superinfection with other defective HIV-1 variants. J Infect Dis 200:1479–1483. doi: 10.1086/606117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quan Y, Xu H, Wainberg MA. 2014. Defective HIV-1 quasispecies in the form of multiply drug-resistant proviral DNA within cells can be rescued by superinfection with different subtype variants of HIV-1 and by HIV-2 and SIV. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:21–27. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, Kappes JC, Conway JA, Price RW, Shaw GM, Hahn BH. 1991. Molecular characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cloned directly from uncultured human brain tissue: identification of replication-competent and -defective viral genomes. J Virol 65:3973–3985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sigal A, Kim JT, Balazs AB, Dekel E, Mayo A, Milo R, Baltimore D. 2011. Cell-to-cell spread of HIV permits ongoing replication despite antiretroviral therapy. Nature 477:95–98. doi: 10.1038/nature10347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mostowy R, Kouyos RD, Fouchet D, Bonhoeffer S. 2011. The role of recombination for the coevolutionary dynamics of HIV and the immune response. PLoS One 6:e16052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Migueles SA, Welcher B, Svehla K, Phogat A, Louder MK, Wu X, Shaw GM, Connors M, Wyatt RT, Mascola JR. 2007. Broad HIV-1 neutralization mediated by CD4-binding site antibodies. Nat Med 13:1032–1034. doi: 10.1038/nm1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet RW, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA. 1998. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature 393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thali M, Olshevsky U, Furman C, Gabuzda D, Li J, Sodroski J. 1991. Effects of changes in gp120-CD4 binding affinity on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein function and soluble CD4 sensitivity. J Virol 65:5007–5012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu D, Wang W, Yoder A, Spear M, Wu Y. 2009. The HIV envelope but not VSV glycoprotein is capable of mediating HIV latent infection of resting CD4 T cells. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000633. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quan Y, Xu H, Kramer VG, Han Y, Sloan RD, Wainberg MA. 2014. Identification of an env-defective HIV-1 mutant capable of spontaneous reversion to a wild-type phenotype in certain T-cell lines. Virol J 11:177. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghoreschi K, Jesson MI, Li X, Lee JL, Ghosh S, Alsup JW, Warner JD, Tanaka M, Steward-Tharp SM, Gadina M, Thomas CJ, Minnerly JC, Storer CE, LaBranche TP, Radi ZA, Dowty ME, Head RD, Meyer DM, Kishore N, O'Shea JJ. 2011. Modulation of innate and adaptive immune responses by tofacitinib (CP-690,550). J Immunol 186:4234–4243. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson GS, Tian A, Hebbard L, Duan W, George J, Li X, Qiao L. 2013. Tumoricidal effects of the JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib (INC424) on hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro. Cancer Lett 341:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhong P, Agosto LM, Munro JB, Mothes W. 2013. Cell-to-cell transmission of viruses. Curr Opin Virol 3:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Politch JA, Marathe J, Anderson DJ. 2014. Characteristics and quantities of HIV host cells in human genital tract secretions. J Infect Dis 210(Suppl 3):S609–S615. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson DJ, Le Grand R. 2014. Cell-associated HIV mucosal transmission: the neglected pathway. J Infect Dis 210(Suppl 3):S606–S608. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kolodkin-Gal D, Hulot SL, Korioth-Schmitz B, Gombos RB, Zheng Y, Owuor J, Lifton MA, Ayeni C, Najarian RM, Yeh WW, Asmal M, Zamir G, Letvin NL. 2013. Efficiency of cell-free and cell-associated virus in mucosal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol 87:13589–13597. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03108-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galloway NL, Doitsh G, Monroe KM, Yang Z, Munoz-Arias I, Levy DN, Greene WC. 2015. Cell-to-cell transmission of HIV-1 is required to trigger pyroptotic death of lymphoid-tissue-derived CD4 T cells. Cell Rep 12:1555–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyauchi K, Kim Y, Latinovic O, Morozov V, Melikyan GB. 2009. HIV enters cells via endocytosis and dynamin-dependent fusion with endosomes. Cell 137:433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cossart P, Helenius A. 2014. Endocytosis of viruses and bacteria. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 6:a016972. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kubo Y, Hayashi H, Matsuyama T, Sato H, Yamamoto N. 2012. Retrovirus entry by endocytosis and cathepsin proteases. Adv Virol 2012:640894. doi: 10.1155/2012/640894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perreira JM, Chin CR, Feeley EM, Brass AL. 2013. IFITMs restrict the replication of multiple pathogenic viruses. J Mol Biol 425:4937–4955. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu J, Pan Q, Rong L, He W, Liu SL, Liang C. 2011. The IFITM proteins inhibit HIV-1 infection. J Virol 85:2126–2137. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01531-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brass AL, Huang IC, Benita Y, John SP, Krishnan MN, Feeley EM, Ryan BJ, Weyer JL, van der Weyden L, Fikrig E, Adams DJ, Xavier RJ, Farzan M, Elledge SJ. 2009. The IFITM proteins mediate cellular resistance to influenza A H1N1 virus, West Nile virus, and dengue virus. Cell 139:1243–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Diamond MS, Farzan M. 2013. The broad-spectrum antiviral functions of IFIT and IFITM proteins. Nat Rev Immunol 13:46–57. doi: 10.1038/nri3344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bailey CC, Zhong G, Huang IC, Farzan M. 2014. IFITM-family proteins: the cell's first line of antiviral defense. Annu Rev Virol 1:261–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-031413-085537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith S, Weston S, Kellam P, Marsh M. 2014. IFITM proteins-cellular inhibitors of viral entry. Curr Opin Virol 4:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Savidis G, Perreira JM, Portmann JM, Meraner P, Guo Z, Green S, Brass AL. 2016. The IFITMs inhibit Zika virus replication. Cell Rep 15:2323–2330. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jia R, Xu F, Qian J, Yao Y, Miao C, Zheng YM, Liu SL, Guo F, Geng Y, Qiao W, Liang C. 2014. Identification of an endocytic signal essential for the antiviral action of IFITM3. Cell Microbiol 16:1080–1093. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ding S, Pan Q, Liu SL, Liang C. 2014. HIV-1 mutates to evade IFITM1 restriction. Virology 454–455:11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu J, Li M, Wilkins J, Ding S, Swartz TH, Esposito AM, Zheng YM, Freed EO, Liang C, Chen BK, Liu SL. 2015. IFITM proteins restrict HIV-1 infection by antagonizing the envelope glycoprotein. Cell Rep 13:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haile WB, Gavegnano C, Tao S, Jiang Y, Schinazi RF, Tyor WR. 2016. The Janus kinase inhibitor ruxolitinib reduces HIV replication in human macrophages and ameliorates HIV encephalitis in a murine model. Neurobiol Dis 92:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gavegnano C, Detorio M, Montero C, Bosque A, Planelles V, Schinazi RF. 2014. Ruxolitinib and tofacitinib are potent and selective inhibitors of HIV-1 replication and virus reactivation in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:1977–1986. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02496-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bovolenta C, Camorali L, Mauri M, Ghezzi S, Nozza S, Tambussi G, Lazzarin A, Poli G. 2001. Expression and activation of a C-terminal truncated isoform of STAT5 (STAT5Δ) following interleukin 2 administration or AZT monotherapy in HIV-infected individuals. Clin Immunol 99:75–81. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bovolenta C, Camorali L, Lorini AL, Ghezzi S, Vicenzi E, Lazzarin A, Poli G. 1999. Constitutive activation of STATs upon in vivo human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood 94:4202–4209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abela IA, Berlinger L, Schanz M, Reynell L, Gunthard HF, Rusert P, Trkola A. 2012. Cell-cell transmission enables HIV-1 to evade inhibition by potent CD4bs directed antibodies. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002634. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ayouba A, Cannou C, Nugeyre MT, Barre-Sinoussi F, Menu E. 2008. Distinct efficacy of HIV-1 entry inhibitors to prevent cell-to-cell transfer of R5 and X4 viruses across a human placental trophoblast barrier in a reconstitution model in vitro. Retrovirology 5:31. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]