Abstract

The Rap-pathway has been implicated in various cellular processes but its exact physiological function remains poorly defined. Here we show that the Caenorhabditis elegans homologue of the mammalian guanine nucleotide exchange factors PDZ-GEFs, PXF-1, specifically activates Rap1 and Rap2. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter constructs demonstrate that sites of pxf-1 expression include the hypodermis and gut. Particularly striking is the oscillating expression of pxf-1 in the pharynx during the four larval molts. Deletion of the catalytic domain from pxf-1 leads to hypodermal defects, resulting in lethality. The cuticle secreted by pxf-1 mutants is disorganized and can often not be shed during molting. At later stages, hypodermal degeneration is seen and animals that reach adulthood frequently die with a burst vulva phenotype. Importantly, disruption of rap-1 leads to a similar, but less severe phenotype, which is enhanced by the simultaneous removal of rap-2. In addition, the lethal phenotype of pxf-1 can be rescued by expression of an activated version of rap-1. Together these results demonstrate that the pxf-1/rap pathway in C. elegans is required for maintenance of epithelial integrity, in which it probably functions in polarized secretion.

INTRODUCTION

Rap1 is a member of the family of Ras-like GTPases that function in signal transduction processes by relaying signals received by transmembrane receptors to downstream effector molecules. Ras-like GTPases switch between an active GTP-bound state and an inactive GDP-bound state. Activation of Ras-like GTPases is mediated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), which induce the dissociation of GDP to allow binding of the more abundant GTP. Four different types of GEFs specific for Rap1 have been described in vertebrates, namely C3G, CD-GEF, Epac, and PDZ-GEF (also named RA-GEF [Liao et al., 1999], Nrap-GEP [Ohtsuka et al., 1999], or CNrasGEF [Pham et al., 2000]; reviewed in Bos et al., 2001). These Rap1-GEFs share a highly homologous catalytic domain including a so-called REM or LTE domain. In addition, each GEF has its own characteristic domains, which regulate GEF activity and/or determine its subcellular location. Together these GEFs may account for the various modes of Rap1 activation seen after ligand occupation of distinct growth factor receptors (Altschuler et al., 1995; Franke et al., 1997; Vossler et al., 1997; Posern et al., 1998; Zwartkruis et al., 1998; reviewed in Bos et al., 2001). For example, EPAC directly binds cAMP, which leads to stimulation of its exchange activity (de Rooij et al., 1998; Kawasaki et al., 1998). Regulation of PDZ-GEFs is less well understood. The N-terminal part of PDZ-GEF resembles a cAMP-binding domain, but because the absence of certain conserved residues prohibits binding of cAMP (Liao et al., 1999; Ohtsuka et al., 1999; Kuiperij et al., 2003) an as yet unidentified second messenger has been suggested to regulate PDZ-GEFs (de Rooij et al., 1999). However, it has also been reported that cAMP can induce Ras-GEF activity of PDZ-GEF, under conditions where its PDZ-domain is bound to the β1-adrenergic receptor (Pak et al., 2002). Apart from interacting with GTPases via its catalytic domain, PDZ-GEF1 can stably interact with GTP-bound Rap1 via its Ras-associating (RA) domain in vitro (Liao et al., 1999), whereas PDZ-GEF2 interacts with M-Ras (Gao et al., 2001). The C-terminal VSAV sequence of PDZ-GEF1 can bind to the second PDZ-domain of the neural scaffolding protein S-SCAM, MAGI-1 or the related product of the KIAA0705 gene (Ohtsuka et al., 1999; Kawajiri et al., 2000; Mino et al., 2000), suggesting that PDZ-GEF functions in a signaling complex with scaffolding proteins at sites of cell-cell contact.

Although cloning of the different Rap1-specific GEFs has opened the way to study the precise mechanisms of Rap1 activation, the physiological function of these GEFs and their target Rap1 is still enigmatic. Experiments in tissue culture cells have pointed toward a role for Rap1 in modulation of the Ras-signaling pathway (Kitayama et al., 1989; Cook et al., 1993; Vossler et al., 1997) and cell cycle control (Altschuler and Ribeiro-Neto, 1998; reviewed in Bos et al., 2001). More recently Rap1 was shown to be involved in activation of integrins in T-cells and macrophages (Caron et al., 2000; Katagiri et al., 2000; Reedquist et al., 2000) and overexpression of the Rap1–specific GAP SpaI was found to abolish adhesion of various cell types to extracellular matrix proteins (Tsukamoto et al., 1999). The mechanism by which Rap1 affects integrin function is largely unknown, but may depend on the polarizing activity of Rap1 (Shimonaka et al., 2003). In addition, a role for Epac2 in cAMP-regulated insulin secretion has been reported (Ozaki et al., 2000) and Epac1 has been implicated in the regulation of intracellular calcium levels via phospholipase ε (Schmidt et al., 2001) or the ryanodine receptor (Kang et al., 2003).

Genetic studies in Drosophila have revealed that Rap1 is an essential gene required during embryogenesis. In the absence of maternally supplied Rap1, mutants display morphogenetic defects including mesodermal cell migration, dorsal closure, and head involution (Asha et al., 1999). These defects have been attributed to a diminished activity of the AF-6 homologue Canoe, which directly can bind to GTP-bound Rap1 and colocalizes in adherens junctions (Boettner et al., 2003). Interestingly, generation of Rap1-/- clones in the wing results in defective adherens junction formation (Knox and Brown, 2002), but it is unclear if Canoe is involved in this as well. Apart from Canoe, the Drosophila RalGEF RGL has been proposed to act as a Rap1 effector on the basis of genetic experiments (Mirey et al., 2003). Finally, in the same organism loss of PDZ-GEF leads to larval lethality. Escapees and animals overexpressing PDZ-GEF show defects that suggest a role for PDZ-GEF and Rap1 in ERK activation (Lee et al., 2002).

We have turned to Caenorhabditis elegans as a model system to define its biological function and dissect the Rap1 signaling pathway by genetic approaches. Here we show that the C. elegans homologue of PDZ-GEF, pxf-1, acts upstream of rap-1 and rap-2. Animals, mutant for either pxf-1 or double mutant for rap-1 and rap-2 remain scrawny, have a disorganized cuticle, and display molting defects. Furthermore, a progressive degeneration of the hypodermis is seen, and adults frequently die with a burst vulva phenotype. From this and the fact that an activated version of RAP-1, RAP-1V12, rescues the lethal phenotype of pxf-1, we conclude that the pxf-1/rap pathway is essential for maintenance of epithelial integrity in C. elegans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Worms

General methods for culturing and manipulating worms used in these studies were as described (Lewis and Fleming, 1995). Worms were cultured on NGM plates at 20°C. Strains and mutations used were Bristol N2, dpy-20 (e1362), mut-7 (pk204), ML652 [mcEx204: pML902 + pRF4], PS3352 pkEx246 [pMH86 + JP#38 (cdh-3::GFP)], JR667 [unc-119(e2498::Tc1) III; wIs51], veIS13 [col-19::GFP + pRF4], BC3106 (let-53 (s43) unc-22(s7)/nT1 IV; +/nT1 V), BC2895 (let-73 (s685) unc-22(s7)/nT1 IV; +/nT1 V), BC2049 (let-658 (s1149) unc-22 (s7 unc-331 (e169)/nT1 IV), +/nT1 V), and BC2067 (let-659 (s1152) unc-22 (s7 unc-331 (e169)/nT1 IV; +/nT1 V). Transgenic animals were obtained by injection of plasmid DNA into the gonad of worms (Mello et al., 1991). Transgenic arrays were integrated by irradiating animals with 40 Gy of gamma radiation from a 137 Cs source (Way et al., 1991). Mutant animals isolated from frozen libraries were out-crossed at least five times to wild-type N2 animals before phenotypic analysis.

Constructs

cDNAs from the T14G10.2 gene were obtained from Dr. Kohara (est yk222e6) or directly isolated by PCR on cDNA and cloned into pGEM-T (Promega, Madison, WI). Nucleotide and protein sequences of the different isoforms have been deposited at GenBank under accession numbers AF308447 (PXF-1-A), AF308448 (PXF-1-B), and AF308449 (PXF-1-C). To determine the specificity of the catalytic domain of pxf-1 the region encompassing the REM-, the PDZ-, and the catalytic domain of PXF-1-A (amino acids 467-1173) was amplified using the primers CTCGAGTTCAGAAGTTGAACGAAGGAC and GCGGCCGCTGTTCAATTGCTGAAAAAACTG and cloned as an XhoI/NotI fragment into pMT2HA.

For reporter studies genomic fragments were obtained by PCR and inserted into the SphI/BamHI site of the pPD95.75 GFP vector (Fire, personal communication). Primers used for pT14G10.2::GFP-I were TAAGATCTTCCTGTCGAGGTTTCCGAGG and ATAGCATGCCTTGGACCATTTTGCTATCTGTG; those for pT14G10.2::GFP-II were ATAGCATGCGATGGAGATGTCGCACGAAG and TAGGATCCCATTCTCGGACAGAATCTCG.

Isolation and Rescue of pxf-1 and rap-1 Mutant Animals

Worms mutant for pxf-1 (NL2808 (pk1331)) were isolated from a frozen library as described in Jansen et al. (1997). The first round of the nested PCR reactions was done with the primers AATTGATGCTCTGGTTTGCC and GGTGGTAAACCTCGTGGAGA, followed by a reaction with TCGAGACGAACGATGAGATG and AGGAAGAACACCCGGAAGAT. To detect the wild-type pxf-1 allele, the primers CGATCTGAACCTCTTGTACCTG and CCAAATTTTCCATTTGTGGTGG were used.

For rescue experiments worms with the genotype dpy-20 (e1362), pxf-1 (pk1331)/+, + IV (NL2817) were generated. This line was then crossed with dpy-20 (e1362)/dpy-20 (e1362) IV pkEx10[T14G10 + pMH86] (NL2850). Rescue of the lethal phenotype by the cosmid T14G10 was evident from the appearance of F2 animals that segregated fertile, phenotypically wild-type animals, and animals that combined the pxf-1 mutant phenotype with a dumpy appearance. In addition, genotyping by PCR confirmed that these latter animals were homozygous pxf-1 mutants. Because cosmids K04D7 or K08F4 did not rescue, only mutations in T14G10.1 and 2 could be causative of the mutant phenotype. Therefore, double-stranded RNA for either gene was fed to N2 and ML652 worms. For T14G10.2 this resulted in a delayed progression through larval stages. In addition, microscopic analysis of dlg-1::GFP showed loss of a restricted number of seam cells in 7% (n = 100) of the animals. Complementation tests with let-53, let-73, let-658, and let-659 mutants was done by first placing these mutations in trans to a dpy-20 (e1362) allele, followed by mating to pxf-1 +/+ dpy-20 (e1362) animals. In all cases complementation was observed.

Mutant rap-1 animals (FZ0181; pk2082) were isolated from a frozen library by means of target selected mutagenesis. To this end an 800-base pair fragment was amplified using the primers GACGAGAGTTTTAGTTACAG and GTGAGTTTCAAAAATGTGTG, followed by a nested reaction using TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTCGAAAATGTATCATATCGAGAC and AGGAAACAGCTATGACCATGTTAGCCTCCTTTTCATTGAG. Sequencing of heteroduplex products revealed the presence of a C to T mutation, resulting in a premature stop at position 130 of RAP-1. Rescue was performed by expression of heat shock promotor driven rap-1, which restored alae formation and restored brood size, to the level seen for wild-type animals, carrying the hsp::rap-1 construct.

Analysis of GFP-expression Patterns and Immunofluorescence

Expression of pxf-1 was done by generating worms carrying pT14G10.2::GFP-I (FZ0116; bjEx40[pT14G10.2::GFP-I/pMH86] and FZ0117; bjIs40[pT14G10.2::GFP-I/pMH86]); and pT14G10.2::GFP-II (NL2815 or NL2821). NL2815 and NL2821 are independent lines showing an identical expression pattern. These and other GFP lines described were mounted on agarose pads and observed under a Nikon (Garden City, NY) or Zeiss (Thornwood, NY) immunofluorescence microscope equipped with Nomarski optics. For analysis of pharyngeal expression in NL2815 and NL2821 eggs were collected from bleached gravid adults and viewed at various time-points with a dissecting microscope under UV light. DPY-7 localization was done using the DPY7–5A antibody and procedures described in Roberts et al. (2003) using a Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-mouse antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) for detection.

Electron Microscopy

Homozygous pxf-1 larvae that failed to molt to L3, L2, and L3 larvae from N2 were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.2 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) at 4°C for 4 h, followed by postfixation in 2% OsO4 at 4°C for 2 h. Samples were dehydrated by acetone series and embedded in Epon resin. Ultrathin sections were double-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and viewed with JOEL 1010 (Tokyo, Japan) transmission microscope.

In Vivo Activation of Small GTPases

The specificity of PXF-1 was determined essentially as described in de Rooij et al. (1999). Briefly, Cos-7 cells were transfected with HA-tagged versions of human Rap1, Ral, or Ras and increasing amounts of PXF-1. After 24 h of serum starvation, cells were lysed and GTP-bound GTPases were isolated using activation-specific probes (GST-RalGDS-RBD for Rap1, GST-RalBP for Ral, and GST-Raf1-RBD for Ras). Isolated GTPases were visualized by means of Western blotting using the 12CA5 monoclonal antibody (de Rooij et al., 1999). Rap2 activation was measured in [32P]orthophosphate-labeled cells as described in de Rooij et al. (1999).

RESULTS

Genomic Organization of pxf-1 and Analysis of cDNAs

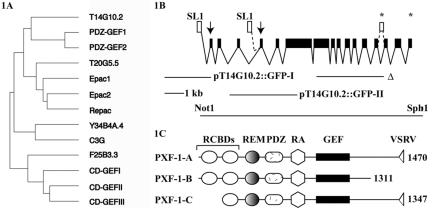

Analysis of the complete genome of C. elegans (Greenstein et al., 1998) reveals the presence of a single homologue for each of the four types of Rap1-GEFs found in vertebrates (Figure 1A). Previously, we had already reported the existence of a C. elegans homologue of the human PDZ-GEF1, which we named CelPDZ-GEF at the time (de Rooij et al., 1999). However, in order to comply with the international nomenclature, we renamed this gene pxf-1 for PDZ-domain containing exchange factor. pxf-1 is located on LG IV and the complete coding sequence is covered by cosmid T14G10 (gene T14G10.2). We cloned three different SL1-spliced messengers from pxf-1 by PCR using primers designed on the basis of predictions made by GENEFINDER, ACeDB as well as sequence information from ESTs of this gene. The protein isoforms encoded by these mRNAs were named PXF-1A to C (Figure 1, B and C). PXF-1-A is the longest isoform (1470 amino acids) and has also been published under the name RA-GEF (Liao et al., 1999). A profile-scan shows that it encodes two cNMP-binding motifs (RCBDs), followed by a Ras exchange motif (REM), a PDZ-domain, a Ras-association (RA) domain and a catalytic domain (GEF). PXF-1-B is encoded by an alternatively spliced messenger and lacks the consensus PDZ-binding motif VSRV at the C-terminus. PXF-1-C resembles PXF-1-A, but does not contain the N-terminal cNMP-binding motif. It is encoded by a transcript in which SL1 is transspliced to exon four. This transcript is derived from an intragenic promoter (see below).

Figure 1.

(A) Phylogenetic tree of catalytic domains of the vertebrate Rap1 guanine nucleotide exchange factors and their C. elegans homologues. The F25B3.3 gene may be more related to the human RasGRF1 gene and thus might function as a RasGEF rather than a RapGEF. (B) Genomic organization of the pxf-1 gene (T14G10.2), located on chromosome IV. Exons are indicated by black boxes, start codons by arrows, and stop codons by asterisks. Differential promoter usage results in transsplicing of SL1 to exon 1 and exon 4. The alternatively spliced exon 14 is indicated by a single white box, but in some cDNAs an intron is removed from this exon (unpublished data). However, both of these splice variants encode PXF-1-C. Promoter fragments used in the reporter constructs and the region deleted in pxf-1 mutants (Δ) are indicated as thin lines (see also Materials and Methods). (C) Schematic representation of the three splice variants of pxf-1. RCBD, related to cNMP binding domain; REM, Ras exchange motif; RA, ras association domain; GEF, guanine nucleotide exchange factor; VSRV, amino acid sequence of the PDZ-binding motif. Numbers at the right indicate the number of amino acids for each isoform.

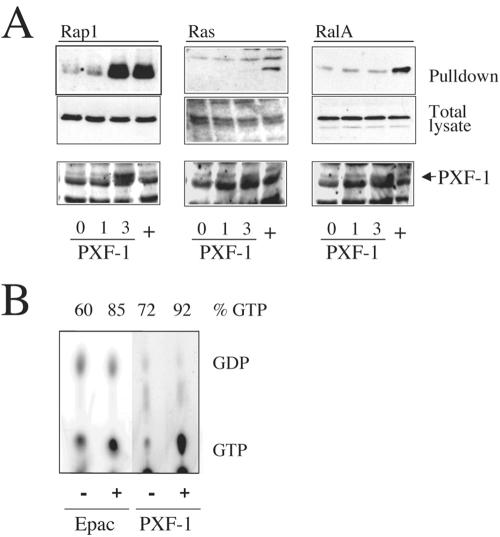

PXF-1 Is a Rap-specific Exchange Factor

To determine the specificity of PXF-1 for the various Ras-like GTPases cotransfection studies were performed in Cos7 cells. A HA-tagged version of PXF-1, encompassing amino acids 467-1173 of PXF-1-A, was coexpressed with HA-tagged human Rap1, Ral, or Ras. GTP-bound GTPases were isolated by virtue of their high-affinity binding to activation-specific probes (see Materials and Methods) and detected by Western blotting. Increasing the amount of PXF-1 specifically activated Rap1 but not Ras or RalA (Figure 2A). Because Rap2 has a high basal level of GTP, the activation-specific probe assay is less sensitive for Rap2. Therefore, the effect of PXF-1 on Rap2 was tested in [32P]orthophosphate-labeled cells, from which HA-tagged Rap2 was immunoprecipitated. Separation of nucleotides bound to Rap2 by TLC showed that coexpression of PXF-1 with HA-tagged Rap2A resulted in a clear increase in the GTP/GDP ratio of Rap2A (Figure 2B). Together, these results show that PXF-1 is a Rap-specific exchange factor.

Figure 2.

(A) In vivo activation of Rap1 by PXF-1. HA-Rap1, HA-RalA, and HA-Ras were cotransfected with increasing amounts of pxf-1 (0, 1, and 3 μg) into Cos-7 cells. As positive controls Epac, CalDAGGEFIII, and Rlf were used as positive controls (lanes labeled +) for Rap, Ras, and Ral activation, respectively. GTP-bound Rap1, Ral, or Ras was isolated using activation specific probes and visualized with 12CA5 antibodies after Western blotting (top panels). Total lysates were blotted and probed with 12CA5 to show equal levels of the transfected HA-tagged GTPases (middle panels) or increasing PXF-1 expression (bottom panels). (B) TLC of nucleotides bound to HA-Rap2A, isolated from [32P]orthophosphate–labeled Cos-7 cells, which had been transfected with HA-Rap2A in the presence or absence of 3 μg pxf-1. GTP/GDP ratios were measured using a phospho-imager. Activation of HA-Rap2A by human EPAC1 is shown as a positive control.

Expression of pxf-1 as Determined by GFP Reporter Constructs

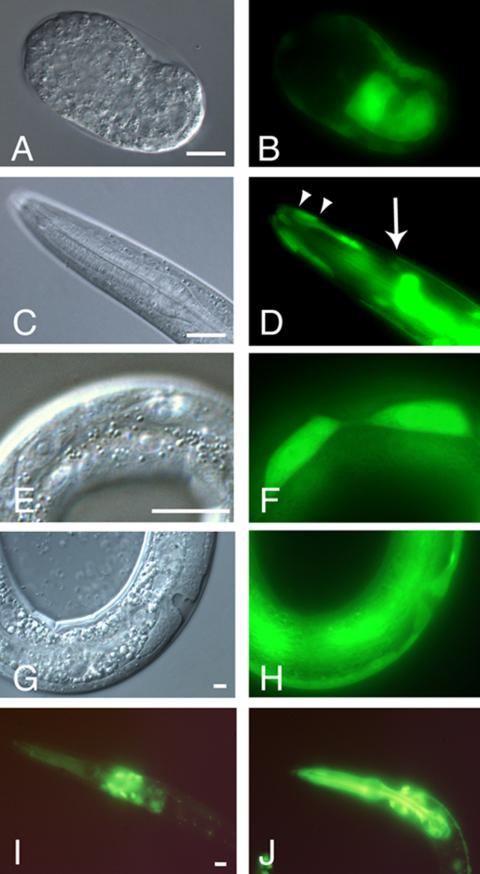

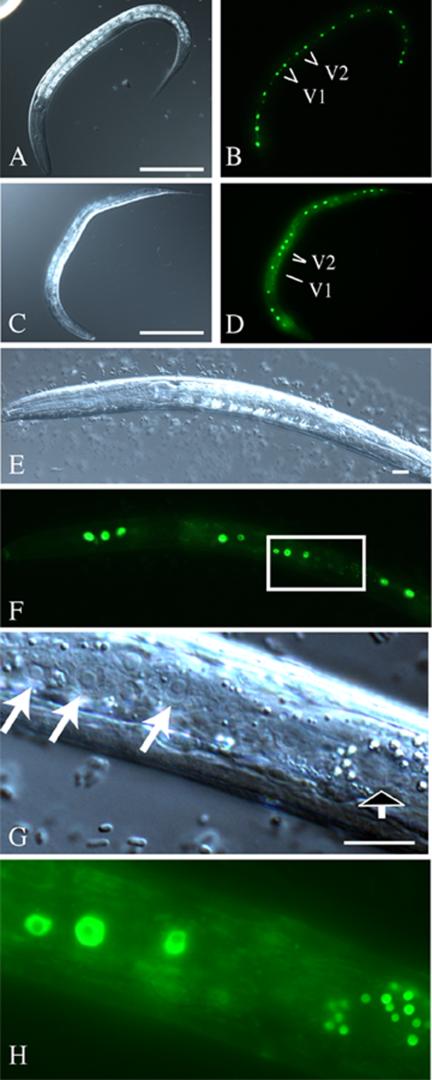

Expression from the upstream pxf-1 promoter was studied by means of a GFP-reporter construct, containing genomic sequences from nucleotide -2394 to +26, relative to the translational start codon in exon I (pT14G10.2::GFP-I; Figure 1B). Expression was first seen at the comma stage in endodermal precursor and slightly later in the hypodermal cells of the embryo (Figure 3, A and B, and unpublished data). During elongation and larval stages many cells of the embryo express GFP, but particularly strong staining was seen in the hypodermis (Figure 3, C and D) and gut. In addition, several neurons in the head were brightly labeled. In general, expression in the lateral seam cells (Figure 3, E and F) and hyp10 was most prominent. However, expression could also clearly be seen in the other hypodermal cells, like the syncytial hyp7 and the Pn.p cells during and after the time of vulval induction (Figure 3, G and H, and unpublished data). In the adult new sites of strong expression included the hermaphrodite-specific neurons (HSNs) and the oviduct sheath cells. The lateral seam cells, which are fused in the adult and other hypodermal cells were also GFP positive (unpublished data).

Figure 3.

Expression of pxf-1. DIC (A, C, E, and G) and epifluorescence (B, D, F, H, I, and J) micrographs of embryos and larvae carrying pT14G10.2::GFP-I as an extrachromosomal array (A–H) or an integrated pT14G10.2::GFP-II construct (I and J). In each case the bar indicates 10 μm. (A and B) Expression in endodermal cells of a comma stage embryo. (C and D) Expression in the hyp7 syncytium (anterior edge marked by arrow) and the annular hyp4 (anterior and posterior margins marked by arrowheads) of a L2 larva. GFP-expressing gut cells are outside the focal plane. (E and F) Expression in lateral seam cells in early L4 larva. (G and H) Expression in hypodermis during vulval formation. (I) Expression in head neurons, but not in the pharynx of a L3 larva during intermolt (see text for details). (J) Expression in head neurons and in the pharynx of a molting L3 larva.

To investigate expression from the downstream promoter a reporter construct was used that contains sequences from nucleotide +990 relative to the translation start of exon I to +4500 located in exon VI (plasmid pT14G10.2::GFP-II; Figure 1B). Expression was detected first in neuronal precursor cells at the comma stage. Slightly later strong expression was found in the hypodermal cells. In newly hatched L1 larvae this construct continued to be expressed in neuronal cells in the head and tail, in cells of the ventral nerve cord and of the pharynx. During the early L1 stage hypodermal expression disappeared. The GFP-positive neurons in animals carrying pT14G10.2::GFP-II were identified as the RMDD, RMD, RMDV, SMDD, and SMDV, which are ring motoneurons. Also the more posteriorly located BDU cells and the ALN, PVR, and PVT cells in the tail expressed GFP. In the course of our studies we noticed a striking difference in GFP expression levels in the pharynx. Analysis of synchronized worms showed that GFP is present around the time of molting, but is barely detectable during part of the intermolts (Figure 3, I and J) or in adults. During the outgrowth of the gonadal primordium expression was seen in the distal tip cell and oviduct sheath cells (unpublished data). It is possible that the two reporter constructs used here contain enhancer elements, which act on both promoters. However, the results clearly show that pxf-1 is widely and dynamically expressed in the main epithelia during all stages.

Isolation of Animals Mutant for pxf-1

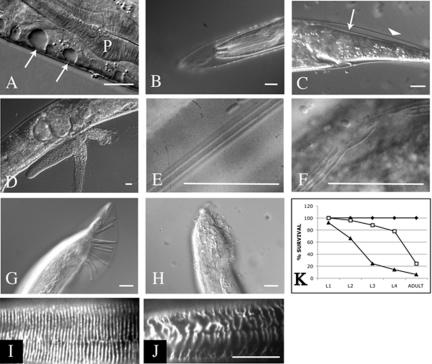

To investigate the function of pxf-1, a deletion library of mutant worms was screened by PCR (Jansen et al., 1997). A single mutant allele of pxf-1 was isolated, in which a 3.4-kb genomic region (encoding amino acids 613-1306 of PXF-1-A; see Figure 1B) was deleted. PXF-1 protein derived from this allele lacks most of the PDZ domain as well as the complete catalytic domain, and therefore is likely to be nonfunctional, at least with respect to Rap activation. No homozygous line could be established because deletion of pxf-1 results in lethality during late larval stages or early adulthood. Timed egglays showed that mutant animals progressed slower through larval stages than wild-type animals. A fraction of the mutant animals could be identified after 24 h by their uncoordinated movement and their slightly smaller size. Inspection by Nomarski optics at 48 h after egg lay showed the appearance of vacuoles just underneath the cuticle in a small fraction of mutant animals. Most commonly these vacuoles were found in the tail region or around the anterior part of the pharynx (Figure 4A). These vacuoles appear to be signs of degeneration of the hypodermis, which at later time points can become more pronounced. From the L2 stage onward, mutant animals displayed molting defects: frequently animals were enclosed within their old cuticle or part of the anterior cuticle remained attached to the pharynx, obstructing it (Figure 4, B and C, Table 1). In some instances animals that were encased in their old cuticle escaped from it and resumed feeding. It is not uncommon for such animals to have trails of old cuticle attached to their bodies or encircling it. The lumen of the gut was enlarged in most mutants and contained undigested bacteria. About 25% of homozygous mutant animals reached adulthood (Table 2). Almost all of them moved in an uncoordinated manner and their body size was strongly reduced as compared with wild-type animals (see Figure 9). Homozygous animals had developed a fairly normal gonad and were able to lay a restricted number of fertilized eggs (see Table 2). Hereafter, the proximal gonad started to degenerate and egg-laying stopped. Mutants then became immotile and died as a “bag of worms.” Alternatively, worms died as a result of a burst vulva (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Phenotype of pxf-1 (pk1331) mutant animal as seen by DIC microscopy (A–H) or immunofluorescence microscopy (I and J). In each case the bar indicates 10 μm. (A) Small vacuoles (white arrows) underneath the cuticle in the pharynx region of a L4 larva. P, the pharynx. (B) L4 larva encased in its old cuticle. Note that the pharyngeal cuticle has been expelled. (C) Unshed cuticle at the posterior part of a L4 larva. The unshed cuticle is indicated with an arrowhead, the new cuticle with an arrow. (D) Adult animal in which the gonads are protruding from the body cavity. (E) Alae of an adult wild-type animal. (F) Disrupted alae of pxf-1 mutant. (G) Sensory rays of wild-type male. (H) Lack of sensory rays in pxf-1 mutant male. (I and J) Localization of DPY-7 in the anterior part of wild-type (I) and pxf-1 (J) L3 larvae, using a monoclonal anti-DPY7–5A antibody. (K) Percentage of survival to the indicated developmental stage of wild-type animals (♦; n = 75), pxf-1-/- mutants from heterozygous hermaprodites (□; n = 82), and from homozygous mutants (▴; n = 76).

Table 1.

pxf-1-/-[ρ] animals analyzed in three separate experiments

| Hours after hatching | unc (%) | vac (%) | mol (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 34 | 4 | 0 |

| 48 | 34 | 12 | 2 |

| 72 | 62 | 32 | 32 |

| 96 | 86 | 70 | 62 |

| 120 | 92 | 84 | 62 |

Values are cumulative percentage of 62 animals.

unc, uncoordinated movement; vac, presence of vacuoles; mol, molting defect.

Table 2.

Survival and proliferation rates of pxf-1 mutant animals

| Genotype | % survival until adult stage | No. of progenya |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 100 | 165 ± 20 (5) |

| pxf-1-/- | 100 | 155 ± 36 (5) |

| pxf-1-/- | 25 (54/212) | 5 ± 3 (14) |

| pxf-1-/- pkEx10[dpy-20 (+) T14G10] | 71 | 54 ± 22 (14) |

| pxf-1-/- bjIs20[Rol-6;hsp::rap-1V12;rap-1::GFP] | 66 | 43 ± 17 (14) |

Larvae (L1 or L2) from heterozygous hermaphrodites were singled and scored for their survival to the adult stage. For pxf-1-/- bjIs20[Rol-6;hsp::rap-1V12;rap-1::GFP], counting of animals surviving to adulthood and number of offspring was done on animals given a daily heat shock. Genotyping of animals was done by PCR.

Values in parentheses are number of animals

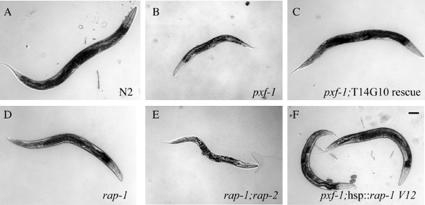

Figure 9.

Overview micrographs of adult wild-type and mutant worms. Scale bar, 100 μm. Pictures are taken 2 d after the animals had reached the L4 stage. (A) Wild-type N2; (B) pxf-1 (pk1331); (C) pxf-1 (pk1331) pkEx10[dpy-20 (+) T14G10]; (D) rap-1 (pk2082); (E) rap-1 (pk2082); rap-2 (gk11); and (F) pxf-1 (pk1331) bjIs20[Rol-6;hsp::rap-1V12].

Given the high expression of pxf-1 in seam cells, we inspected the alae, which are cuticular structures secreted by lateral hypodermal (seam) cells after fusion. In virtually all mutant adults alae were less distinct or interrupted (Figure 4, E and F). In males, the lateral hypodermal cells V5, V6, and T form sensory rays in the tail. In pxf-1 mutant males these structures are malformed and barely visible (n = 9; Figure 4, G and H and unpublished data). Formation of spicules on the other hand appeared normal. Although clear cuticle defects in pxf-1 adults were noticed, the earliest defects in pxf-1 mutants were observed at the L2 stage. At this stage the cuticle does not contain any alae, but only circumferential ridges (the annuli), which appeared to be present. To obtain a more detailed view of the cuticle, we immunostained wild-type and pxf-1 mutant larvae with an antibody against the collagen DPY-7 (kindly provided by Dr. I. Johnstone). In wild-type animals this antibody detects DPY-7 in very regular circumferential bands (Roberts et al., 2003). In contrast, in pxf-1 animals DPY-7 was present in bands, which not always ran parallel and were wider and often interrupted (Figure 4, I and J). This demonstrates that also at earlier stages the hypodermis is affected in secretion of the cuticle. Taken together, these results indicate a requirement for PXF-1 in the hypodermis, especially in the seam cells.

Adult homozygous pxf-1 hermaphrodites produce a small brood. Only a minority of the offspring from these mutants develops beyond the L3 stage (Figure 4K). They display the same, albeit more severe phenotypic traits. In addition, a low level of embryonic lethality is seen (7%). This strongly suggests that there is maternal contribution of PXF-1 protein to embryos. Yet it also demonstrates that significant development in the absence of PXF-1 is possible. This is in striking contrast with the situation in Drosophila, where PDZ-GEF mutant animals from heterozygous mothers show high level of embryonic lethality (Lee et al., 2002).

Transformation of mutant animals with the cosmid T14G10, carrying the complete pxf-1 gene, as an extrachromosomal array led to complete rescue of all aspects of the above described phenotype (see Table 2). No rescue was seen with the overlapping cosmids K04D7 or K08F4. Because RNAi with T14G10.2 (see also Materials and Methods) resulted in a delayed growth and a low frequency (7%) of hypodermal abnormalities described below we conclude that the phenotype described is caused by disruption of pxf-1.

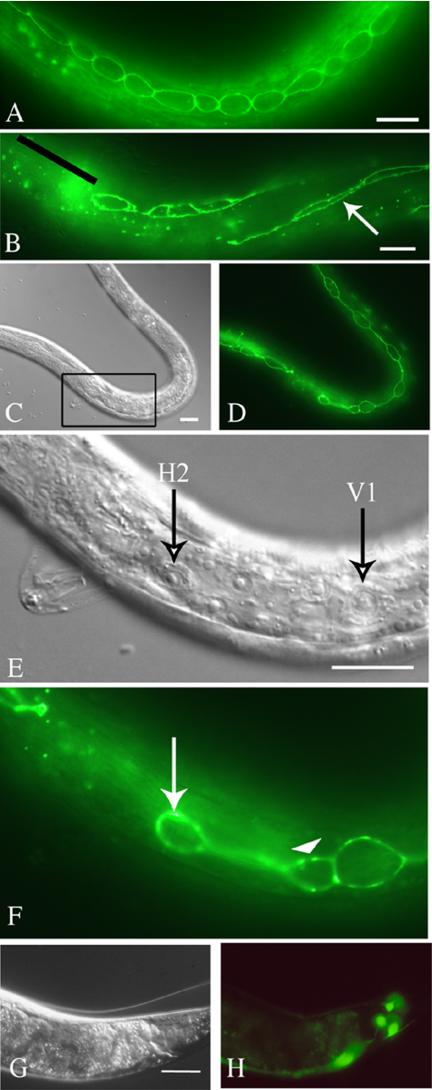

Hypodermal Defects in pxf-1 Mutant Animals

To analyze the hypodermal defects in more detail, various GFP-reporter constructs were introduced into a pxf-1 mutant background. The seam cells are known to be important for cuticle secretion, and their cell division is tightly coupled to molting events (Sulston and Horvitz, 1977; Austin and Kenyon, 1994). When the seam cells of mutant L1 larvae were marked using either the cdh-3::GFP (Pettitt et al., 1996) or the SCM::GFP construct (Koh and Rothman, 2001), it was clear that the correct number of seam cells had been specified. The SCM::GFP marker marks the nuclei of seam cells, which are very regularly spaced in wild-type animals (Figure 5, A and B). Using the SCM::GFP marker, no abnormalities were seen in the division patterns of these seam cells during the L1 to L2 molt (Sulston and Horvitz, 1977; Austin and Kenyon, 1994). However, at later stages mutant animals were seen in which expression of the SCM::GFP was extremely weak or absent at various positions along the body. The seam cell nuclei were often irregularly spaced in more affected animals (Figure 5, C–H). Weakly staining nuclei often had a shrunken appearance. Nomarski microscopy confirmed that the lack of SCM::GFP expression resulted from a loss of seam cells (Figure 5, G and H). Importantly, however, animals that could not complete molting frequently had normal appearing seam cells, demonstrating that hypodermal degeneration does not necessarily precede molting defects. We also noted a number of mutant animals in which seam cell expression was weak in the midbody and in which the nuclei of the seam cells still could be seen by Nomarski optics. This most likely resulted from the inability of mutants to feed, because starvation of wild-type animals resulted in a similar decrease of SCM::GFP expression in the midbody.

Figure 5.

pxf-1 mutants display loss of seam cells. DIC (A, C, E, and G) and epifluorescence (B, D, F, and H) micrographs of wild-type (A and B) and pxf-1 mutant animals (C–H) transgenic for SCM::GFP. Scale bars, 100 μm (A and C); 10 μm (E and G). (A and B) Late wild-type L2 larva, showing the regular spacing of seam cells. Descendants of the V1 and V2 cells are indicated. (C and D) pxf-1 mutant L2 larva, in which one of the V1 and V4 descendants are missing. Descendants of the V1 and V2 cells are indicated. (E and F) pxf-1 mutant L2 larva, in which V3 descendants have degenerated. (G and H) Enlargement of the region indicated in F. The black and white arrow indicates the place in which a V3 descendant is expected, but where no nucleus is seen. The brightly fluorescent dots may represent remnants of this nucleus. Other seam cell nuclei are indicated with white arrows.

Given the fact that lack of Rap1 in Drosophila perturbs adherens junction formation (Knox and Brown, 2002), we used dlg-1::GFP to mark the adherens junctions of seam and other cells (Figure 6; McMahon et al., 2001). Adherens junctions in pxf-1 mutant L1 larvae had a regular, uninterrupted appearance and showed that also the shape of seam cells was normal. As expected, also with this marker we noticed a loss of seam cells from the early L2 stage onward. Interestingly, in a restricted number of animals this marker revealed seam cells with an abnormal morphology (Figure 6, C–F), suggesting that such cells were affected in their ability to reorganize cell-cell contacts or the cytoskeleton. dlg-1::GFP staining in other parts of the body like the pharynx and the Pn.p cells was normal. If present, the seam cells fused normally at the L4 to adult molt. Analysis of pxf-1 mutants with various other GFP constructs, including pT14G10.2::GFP-II, did not reveal any other abnormalities (Figure 6, G and H).

Figure 6.

Morphology of seam cells in pxf-1 visualized by dlg-1::GFP. Epifluorescence (A, B, D, F, and H) and DIC (C, E, and G) micrographs of wild-type (A) and pxf-1 mutant animals (B–H) transgenic for dlg-1::GFP (A–F) or pT14G10.2::GFP-II (G and H). In each case the bar indicates 10 μm. (A) Wild-type L2 larva, showing the regular organization of seam cells. (B) pxf-1 mutant L2 larva, in which anterior seam cells are missing (indicated by a black line above their expected location). A white arrow indicates the array of Pn.p cells. (C–F) pxf-1 mutant in which seam cells have undergone their first round of division during L2. (E and F) A higher magnification of the inset from C. Seam cells have formed processes extending in anterior and posterior directions from their cell body. The descendant of H2 (H2pp) has a dumb-bell shape with a very thin cytoplasmic bridge connecting the anterior part with a nucleus (arrow) and the posterior part (arrowhead), which is contacting the descendant of V1 (V1pa). (G and H) Normal appearance of neurons labeled by pT14G10.2::GFP-II in a pxf-1 mutant adult that displayed uncoordinated movement and had a molting defect.

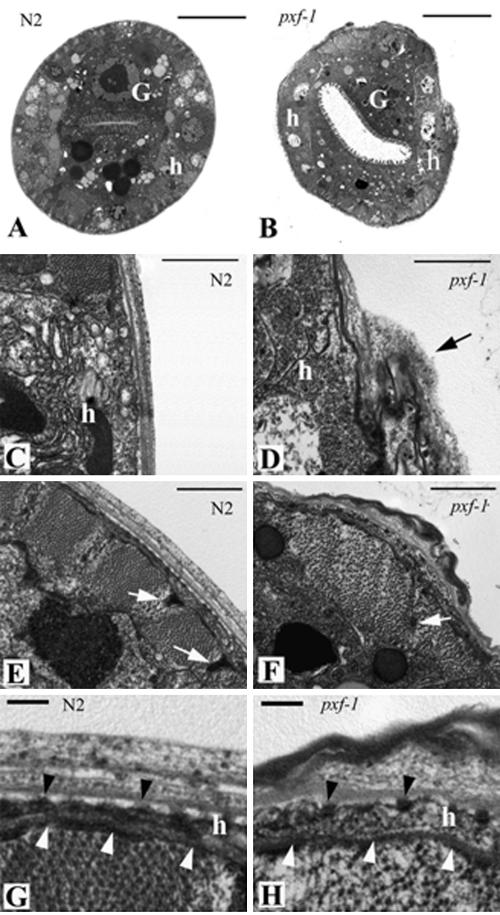

As a complementary approach in the analysis of pxf-1 mutants, electron microscopy was used to investigate L2 and L3 larvae (Figure 7). In contrast to wild-type worms, which have a characteristic round shape, pxf-1 mutants were deformed (Figure 7, A and B). The lumen of the gut was clearly enlarged, consistent with images from light microscopy. Microvilli are present but have a shortened appearance. The most striking difference was found in the cuticle of mutants, which was irregular around the entire circumference, varied in thickness and was folded. Furthermore, the overall organization appears much more loose than in wild-type siblings. Importantly, both the underlying lateral hypodermis and hyp7 had a fairly normal appearance, with a basal lamina and fibrous organelles being present (Figure 7, C, D, G, and H). Muscles of pxf-1 mutants were less regularly spaced compared with those of wild-type animals, slightly disorganized and their dense bodies were less prominent (Figure 7, E and F). The defects in muscle organization were unexpected given the fact that no muscle expression of pxf-1 was seen using GFP-reporters. However, it is well established that the hypodermis is of crucial importance for muscle architecture and mechanical coupling of muscle cells with the cuticle (for a review, see Michaux et al., 2001). Therefore, it is a realistic option that disorganization of muscle cells may result from hypodermal defects. Other cells like the ventral cord neurons appeared normal (unpublished data). In summary, ultrastructural analysis demonstrates that pxf-1 is required in the hypodermis for proper formation of the cuticle and that hypodermal degeneration does not precede cuticle defects.

Figure 7.

Electron microscopic analysis of wild-type (A, C, E, and G) and pxf-1 mutants (B, D, F, and H). Pictures are taken from the midbody of L3 larvae. (A and B) Cross sections, showing the overall shape of wild-type (A) and pxf-1 mutant (B). Note the widened gut lumen in the pxf-1 mutant. The gut cells (labeled G) contain fewer electron dense vesicles as compared with wild-type cells. Hypodermal cells are labeled h and in the pxf-1 mutant underlie a cuticle, which is thin and irregular around the entire circumference. (C and D) Lateral hypodermis (h). Abnormal accumulation of cuticle structures in pxf-1 mutant is indicated by an arrow. (E) Wild-type animal, showing the regular organization of muscle cells. (F) Muscle quadrant of pxf-1 mutant. White arrow indicates dense body. (G and H) Hyp7 (h) and cuticle of wild-type and pxf-1 mutant animals. The cuticle has a striated and regular organization in the wild-type animal (G), whereas those of the pxf-1 mutant display extra folds and a looser organization (H). The basal lamina underneath the hypodermis is indicated with white arrowheads; fibrous organelles are marked with black arrowheads. Bar, 5 μm (A and B), 1 μm (C–F), or 200 nm (G and H).

pxf-1 Acts Upstream of rap-1 and rap-2

To obtain genetic evidence for pxf-1 as a rap-specific GEF, rap mutants were investigated. The C. elegans genome contains three genes with high homology to vertebrate Rap proteins. Of these, rap-1 (C27B7.8) and rap-2 (C25D7.7) are clear homologues of Rap1 and Rap2, respectively, whereas rap-3 (C08F8.7) encodes a more distinct member. rap-2 null mutants (VC14; kindly provided by Dr. R. Barstead) did not display any detectable phenotype. We therefore used target-selected mutagenesis and isolated a rap-1 mutant carrying a premature stop-codon at position 130 (FZ0181, pk2082). Truncation of RAP-1 at this position leads to a loss of the G5-loop, known to be required for GTP binding and of the C-terminal CAAX-box motif, involved in membrane targeting. We therefore believe that this mutant represents a null allele. Homozygous rap-1 mutants are viable and fertile, but show striking similarities to pxf-1 mutants. First, they develop slower than wild-type and especially the molting process appears retarded. Alae of adults are almost always (94%) absent or interrupted (Figure 8A), and loss of seam cells is seen during late larval stages using the SCM::GFP and dlg-1::GFP markers (unpublished data). Adult hermaphrodites die with a burst vulva phenotype at a low frequency (∼5%, Figure 8B) or die as a bag of worms after degeneration of the proximal gonad. Consequently, rap-1 mutants have a reduced brood-size (36% of that of wild-type animals). In males, sensory rays are formed, but especially the most posterior rays are frequently lost (Figure 8C). To see if RAP-2 would function redundantly with RAP-1, double mutants were generated. Although removal of a single rap-2 allele did not affect the rap-1 phenotype, removal of both alleles largely reproduced the pxf-1 phenotype: it caused lethality at a late larval or early adult stage, and animals had an enlarged gut lumen with undigested bacteria (Figure 8D). Furthermore, animals remained scrawny (Figure 9E), they showed molting defects, and adults almost invariably died with a burst vulva phenotype or as a bag of worms as seen for pxf-1.

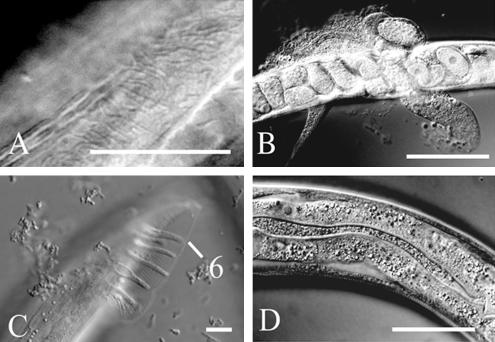

Figure 8.

DIC micrographs of rap-1 (A–C) and rap-1; rap-2 mutant animals (D). Scale bars, 10 μm (A, C, and D); 100 μm (B). (A) Disrupted alae in rap-1 mutant. (B) Adult with burst vulva. (C) rap-1 male, lacking rays posterior to ray 6 (numbered as in Sulston and Horvitz, 1977). (D) Widened gut with undigested material in a L4 larva, double mutant for rap-1 and -2.

Given the fact that the rap-1 phenotype was most similar to that of pxf-1, we tried to rescue pxf-1 mutants with an activated version of RAP-1, RAP-1V12. When placed under the control of the heat shock promoter (hsp), expression of RAP-1V12 by a daily heat shock in wild-type animals slowed progress through larval stages, but did not affect viability. In pxf-1 mutants expression of RAP-1V12 significantly increased the number of mutants that reached adulthood as well as the number of progeny (Table 2). Furthermore, when grown continuously at 20°C, lines homozygous for pxf-1 could be propagated. However, even though RAP-1V12 largely rescued the lethality of the pxf-1 mutation, pxf-1-/-; hsp::rap-1V12 animals develop slower and remain somewhat smaller than wild-type worms (Figure 9F).

DISCUSSION

PXF-1 Is an Exchange Factor for RAP1 and RAP2

In this report we have characterized the pxf-1 gene (T14G10.2) of C. elegans, which encodes three protein isoforms. When compared with human PDZ-GEF proteins, it is clear that PXF-1-C is most similar to hPDZ-GEF1 because it contains a single RCBD. The other isoforms contain two of these motifs and consequently resemble hPDZ-GEF2 (de Rooij et al., 1999; Liao et al., 1999; Kuiperij et al., 2003). Strikingly, alternative splicing of mRNA from this latter gene also yields proteins that either contain a PDZ-binding motif at the C-terminus, resembling PXF-1-A, or lack it as seen for PXF-1-B (Kuiperij et al., 2003). Like its mammalian homologues, PXF-1 displays guanine nucleotide exchange activity toward Rap1 and Rap2. Our transfection studies confirm the findings of Liao et al. (1999), who showed that in tissue culture cells PXF-1 activates Rap1. However, these authors also demonstrated Ras-exchange activity in vitro, which we could not detect in our cotransfection experiments. Ras activation by human PDZ-GEF1 in tissue culture cells has also been reported (Pak et al., 2002), and we have currently no explanation for this discrepancy. Importantly, our genetic experiments provide evidence that PXF-1 functions as a RAP-exchange factor in vivo. First, disruption of pxf-1 or rap-1 shows that they both function in the hypodermis and in particular the lateral hypdermal cells. Clearly, the pxf-1 phenotype is more severe than that of rap-1 mutants, which appears to result from functional redundancy of rap-1 with rap-2. The presence of a single functional rap-1 or rap-2 allele is sufficient for viability, but double mutants display a lethal phenotype, which is virtually identical to that of pxf-1 mutants. Moreover, overexpression of an activated version of RAP-1 (RAP-1V12) rescues the lethal phenotype of pxf-1, which strongly supports the notion that pxf-1 acts upstream of rap-1 in vivo. pxf-1-/-; hsp::rap-1V12 animals still develop more slowly and remain smaller than wild-type animals. It is possible that this is due to the fact that PXF-1 has functions other than RAP-1 activation. However, we think it is more likely that heat-shock driven overexpression of RAP-1V12 does not mimic the spatio-temporal control of RAP-1 activation by PXF-1. Furthermore, despite being less sensitive to GTPase activating proteins, RAP-1V12 may still require PXF-1 activity to become highly GTP-bound. Indeed, in an analogous situation signaling by a gain-of-function allele of let-60/ras was found to be diminished by lowering the activity of its upstream activator SOS-1 (Chang et al., 2000). So far, analysis of pxf-1 mutants did not reveal a role for PXF-1 as a LET-60/RAS-GEF: vulval development in hermaphrodites and spicule formation in males, both known to be dependent on LET-60 RAS, appear normal. This is consistent with a genetic analysis of PDZ-GEF in Drosophila, which led to the conclusion that it functions as a Rap1-GEF rather then a Ras-GEF (Lee et al., 2002).

pxf-1 Is Required in the Hypodermis

GFP-reporter studies show that pxf-1 is widely expressed in a specific spatio-temporal pattern, suggesting a function for pxf-1 in multiple tissues. In line with this, pxf-1 mutants have a pleiotropic phenotype, which includes uncoordinated movement, an enlarged gut lumen, and a strongly reduced fertility. Many aspects of the phenotype however, point to a critical function for pxf-1 in seam cells, where it is highly expressed. For example, the alae, which are secreted by the seam cells, are faint and interrupted in almost all mutant adults. Second, the sensory rays in males, formed by the seam cells V5, V6, and T are malformed. Also the “burst vulva” phenotype hints to a compromised seam cell function, because it is indicative of a loss of contact between seam cells and the utse or VulE cells, which are connected to the uterus (Sharma-Kishore et al., 1999; Newman et al., 2000).

The molting defect seen in pxf-1 mutants provides the most direct evidence for a hypodermal function of pxf-1. Molting is a complex process in which first a stage-specific, collageneous cuticle is synthesized underneath the old one by cells of the pharynx and hypodermis. During this period high secretory activity is seen in the hypodermis, including the lateral seam cells (Singh, 1978). Simultaneously, the cortical actin cytoskeleton in the hypodermis undergoes a dramatic reorganization into circumferential-oriented actin bundles, which disappear again during the final stages of cuticle formation (Costa et al., 1997). Two observations suggest that the molting defect in pxf-1 mutants is not simply the result of the observed loss of seam cells, but instead suggest that pxf-1 plays an active role in the process of molting. First, in many young animals, which could not complete molting, all seam cells were present and no signs of degeneration of the hypodermis were seen. Also ultra-structural analysis shows the presence of hypodermal cells underneath an abnormally organized cuticle in pxf-1 mutants. Second, pharyngeal expression of pxf-1 precisely coincides with molting and is barely detectable during intermolts. Similar oscillating expression patterns have been reported for genes encoding structural proteins of the cuticle like collagen genes (Johnstone, 2000; McMahon et al., 2003), but also for the lin-42 gene, which regulates the timing of molting events (Jeon et al., 1999) and the nuclear hormone receptor nhr-23, disruption of which also causes molting defects (Kostrouchova et al., 1998). Finally, loss of seam cells has also been described for worms, mutant for plx-1, which encodes a plexin-type of transmembrane receptor for semaphorins (Fujii et al., 2002). However, for plx-1 no molting defects have been reported. Loss of seam cells in plx-1 mutants is caused by a reduced number of cell divisions during larval stages. After each division the anterior seam cell daughter fuses with hyp-7 in wild-type worms, whereas the posterior cell will undergo further divisions. These divisions require that the posterior cell reestablishes contacts with its anterior and posterior neighbors (Austin and Kenyon, 1994). In plx-1 mutants this does not occur, most likely because of changes in adhesive properties. Given the fact that the Rap1 pathway is involved in cell-matrix and cell-cell adhesion, we considered this an attractive scenario for our pxf-1 mutant. Although seam cells sporadically display an abnormal morphology in pxf-1 mutants, analysis of seam cells with the SCM::GFP marker show that the majority of cell divisions occurs normally and that seam cells are lost by degeneration. The precise cause of this degeneration is currently unknown, but it is possible that the disorganized cuticle provides insufficient protection against mechanical stress.

The hypodermal degeneration and rupture of the vulval region distinguishes pxf-1 mutants from previously described molting mutants like those carrying mutations in lrp-1, nhr-23, or nhr-25 (Kostrouchova et al., 1998; Yochem et al., 1999; Asahina et al., 2000; Gissendanner and Sluder, 2000). Instead, the pxf-1 phenotype much more resembles that of worms, in which sec-23 functioning is reduced by RNAi during larval stages (Roberts et al., 2003). Apart from the molting defect and burst vulva phenotype, these animals also grow slowly and have an enlarged gut lumen filled with undigested bacteria. In addition, both have a disorganized cuticle, as determined by detection of DPY-7 collagen using immunofluorescence. Null mutants of sec-23 were isolated on the basis of their inability to secrete cuticle components. Although sec-23 mutants are embryonic lethal and thus have a more severe phenotype, the RNAi result shows that compromised secretion of cuticle components can lead to molting defects. Likewise, loss of pxf-1 or rap-1 and rap-2 may reduce the (polarized) secretory activity of the hypodermis to a level below that required for molting. A role for pxf-1 in secretion is in line with the expression observed in tissues involved in polarized secretion, such as the hypodermis and gut. Furthermore, also the Rap-specific exchange factor, Epac2, has been shown to be involved in enhancing secretion, namely of insulin from pancreatic beta-cells (Ozaki et al., 2000). The Rap1 pathway appears not to be absolutely required for secretion, but may increase the efficiency indirectly by organizing some spatial feature. Intriguingly, in yeast the RAP-1 homologue RSR1 is essential for proper bud site selection, but not for bud formation per se. Bud site selection relies on polarization of the cytoskeleton to target secretory vesicles to a specific site in the cell. Also the well-documented stimulatory effect of Rap1 on integrin function in lymphocytes may depend on the polarizing activity of Rap1 in these cells (Shimonaka et al., 2003), possibly via its effector RapL (Katagiri et al., 2003). Definite proof for a role of pxf-1 and rap-1/2 in polarized secretion awaits further characterization of these mutants. In any case, the described hypodermal defect offers a good starting point for identification of additional components of the Rap1 pathway in C. elegans and opens the way to a comparative analysis of this pathway in distinct organisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Y. Kohara for kindly providing us with cDNA clones and Dr. A. Fire for GFP vectors; Theresa Stiernagle and the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center for sending various mutant and GFP-marker strains; and Dr. M. Labouesse for ML652, Dr. A. Rougvie for veIS13, Dr. J. Pettitt for PS3352, Dr. Barstead for VC14 (rap-2), Dr. J. Rothman for JR667, and Dr. I. Johnstone for the DPY-7 antibody. We thank Stephen Wicks for identifying GFP-expressing neurons. We thank the facility of Laboratory of Electron Microscopy, Institute of Parasitology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, and all members of the Plasterk and Bos lab for critical comments and continuous support. We especially thank Karen Thijssen, Marieke van der Horst, and Rene Ketting for technical assistance. We thank Rik Korswagen for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society, Koningin Wilhelmina Fonds (M.V.), the Center for Biomedical Genetics (F.Z.), the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO-ALW; J.d.R.), and grant Grantova Agentura Akademie Ved KJB5022303 (M.A.).

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E04–06–0492. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0492.

References

- Altschuler, D. L., Peterson, S. N., Ostrowski, M. C., and Lapetina, E. G. (1995). Cyclic AMP-dependent activation of Rap1b. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 10373-10376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschuler, D. L., and Ribeiro-Neto, F. (1998). Mitogenic and oncogenic properties of the small G protein Rap1b. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 7475-7479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahina, M., Ishihara, T., Jindra, M., Kohara, Y., Katsura, I., and Hirose, S. (2000). The conserved nuclear receptor ftz-F1 is required for embryogenesis, moulting and reproduction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Cells 5, 711-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asha, H., de Ruiter, N. D., Wang, M. G., and Hariharan, I. K. (1999). The Rap1 GTPase functions as a regulator of morphogenesis in vivo. EMBO J. 18, 605-615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J., and Kenyon, C. (1994). Cell contact regulates neuroblast formation in the Caenorhabditis elegans lateral epidermis. Development 120, 313-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettner, B., Harjes, P., Ishimaru, S., Heke, M., Fan, H.Q., Qin, Y., Van Aelst, L., and Gaul, U. (2003). The AF-6 homolog canoe acts as a Rap1 effector during dorsal closure of the Drosophila embryo. Genetics 165, 159-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos, J. L., de Rooij, J., and Reedquist, K. A. (2001). Rap1 signalling: adhering to new models. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2, 369-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron, E., Self, A. J., and Hall, A. (2000). The GTPase Rap1 controls functional activation of macrophage integrin alphaMbeta2 by LPS and other inflammatory mediators [In Process Citation]. Curr. Biol. 10, 974-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C., Hopper, N. A., and Sternberg, P. W. (2000). Caenorhabditis elegans SOS-1 is necessary for multiple RAS-mediated developmental signals. EMBO J. 19, 3283-3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, S. J., Rubinfeld, B., Albert, I., and McCormick, F. (1993). RapV12 antagonizes Ras-dependent activation of ERK1 and ERK2 by LPA and epidermal growth factor in Rat-1 fibroblasts. EMBO J. 12, 3475-3485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M., Draper, B. W., and Priess, J. R. (1997). The role of actin filaments in patterning the Caenorhabditis elegans cuticle. Dev. Biol. 184, 373-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rooij, J., Boenink, N. M., van Triest, M., Cool, R. H., Wittinghofer, A., and Bos, J. L. (1999). PDZ-GEF1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor specific for Rap1 and Rap2. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 38125-38130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rooij, J., Zwartkruis, F. J., Verheijen, M. H., Cool, R. H., Nijman, S. M., Wittinghofer, A., and Bos, J. L. (1998). Epac is a Rap1 guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor directly activated by cyclic AMP. Nature 396, 474-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke, B., Akkerman, J. W., and Bos, J. L. (1997). Rapid Ca2+-mediated activation of Rap1 in human platelets. EMBO J. 16, 252-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, T., Nakao, F., Shibata, Y., Shioi, G., Kodama, E., Fujisawa, H., and Takagi, S. (2002). Caenorhabditis elegans PlexinA, PLX-1, interacts with transmembrane semaphorins and regulates epidermal morphogenesis. Development 129, 2053-2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X., Satoh, T., Liao, Y., Song, C., Hu, C. D., Kariya Ki, K., and Kataoka, T. (2001). Identification and characterization of RA-GEF-2, a Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor that serves as a downstream target of M-Ras. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 42219-42225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gissendanner, C. R., and Sluder, A. E. (2000). nhr-25, the Caenorhabditis elegans ortholog of ftz-f1, is required for epidermal and somatic gonad development. Dev. Biol. 221, 259-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein, D., Hird, S., Plasterk, R. H., Andachi, Y., Kohara, Y., Wang, B., Finney, M., and Ruvkun, G. (1998). Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology. The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. Science 282, 2012-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, G., Hazendonk, E., Thijssen, K. L., and Plasterk, R. H. (1997). Reverse genetics by chemical mutagenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Genet. 17, 119-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, M., Gardner, H. F., Miller, E.A., Deshler, J., and Rougvie, A. E. (1999). Similarity of the C. elegans developmental timing protein LIN-42 to circadian rhythm proteins. Science 286, 1141-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, I. L. (2000). Cuticle collagen genes. Expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Trends Genet. 16, 21-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, G., Joseph, J. W., Chepurny, O. G., Monaco, M., Wheeler, M. B., Bos, J. L., Schwede, F., Genieser, H. G., and Holz, G. G. (2003). Epac-selective cAMP analog 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP as a stimulus for Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release and exocytosis in pancreatic beta-cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 8279-8285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri, K., Hattori, M., Minato, N., Irie, S., Takatsu, K., and Kinashi, T. (2000). Rap1 is a potent activation signal for leukocyte function-associated antigen 1 distinct from protein kinase C and phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 1956-1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri, K., Maeda, A., Shimonaka, M., and Kinashi, T. (2003). RAPL, a Rap1-binding molecule that mediates Rap1-induced adhesion through spatial regulation of LFA-1. Nat. Immunol. 4, 741-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawajiri, A., Itoh, N., Fukata, M., Nakagawa, M., Yamaga, M., Iwamatsu, A., and Kaibuchi, K. (2000). Identification of a novel beta-catenin-interacting protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 273, 712-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki, H., Springett, G. M., Mochizuki, N., Toki, S., Nakaya, M., Matsuda, M., Housman, D. E., and Graybiel, A. M. (1998). A family of cAMP-binding proteins that directly activate Rap1. Science 282, 2275-2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama, H., Sugimoto, Y., Matsuzaki, T., Ikawa, Y., and Noda, M. (1989). A ras-related gene with transformation suppressor activity. Cell 56, 77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox, A. L., and Brown, N. H. (2002). Rap1 GTPase regulation of adherens junction positioning and cell adhesion. Science 295, 1285-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh, K., and Rothman, J. H. (2001). ELT-5 and ELT-6 are required continuously to regulate epidermal seam cell differentiation and cell fusion in C. elegans. Development 128, 2867-2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostrouchova, M., Krause, M., Kostrouch, Z., and Rall, J. E. (1998). CHR3, a Caenorhabditis elegans orphan nuclear hormone receptor required for proper epidermal development and molting. Development 125, 1617-1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiperij, H. B., de Rooij, J., Rehmann, H., van Triest, M., Wittinghofer, A., Bos, J. L., and Zwartkruis, F. J. (2003). Characterisation of PDZ-GEFs, a family of guanine nucleotide exchange factors specific for Rap1 and Rap2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1593, 141-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. H., Cho, K. S., Lee, J., Kim, D., Lee, S. B., Yoo, J., Cha, G. H., and Chung, J. (2002). Drosophila PDZ-GEF, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rap1 GTPase, reveals a novel upstream regulatory mechanism in the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 7658-7666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J. A., and Fleming, J. T. (1995). Basic culture methods. Methods Cell Biol. 48, 3-29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y. et al. (1999). RA-GEF, a novel Rap1A guanine nucleotide exchange factor containing a Ras/Rap1A-associating domain, is conserved between nematode and humans. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 37815-37820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, L., Legouis, R., Vonesch, J. L., and Labouesse, M. (2001). Assembly of C. elegans apical junctions involves positioning and compaction by LET-413 and protein aggregation by the MAGUK protein DLG-1. J. Cell Sci. 114, 2265-2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, L., Muriel, J. M., Roberts, B., Quinn, M., and Johnstone, I. L. (2003). Two sets of interacting collagens form functionally distinct substructures within a Caenorhabditis elegans extracellular matrix. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 1366-1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello, C. C., Kramer, J. M., Stinchcomb, D., and Ambros, V. (1991). Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 10, 3959-3970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaux, G., Legouis, R., and Labouesse, M. (2001). Epithelial biology: lessons from Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene 277, 83-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mino, A., Ohtsuka, T., Inoue, E., and Takai, Y. (2000). Membrane-associated guanylate kinase with inverted orientation (MAGI)-1/brain angiogenesis inhibitor 1-associated protein (BAP1) as a scaffolding molecule for Rap small G protein GDP/GTP exchange protein at tight junctions. Genes Cells 5, 1009-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirey, G., Balakireva, M., L'Hoste, S., Rosse, C., Voegeling, S., and Camonis, J. (2003). A Ral guanine exchange factor-Ral pathway is conserved in Drosophila melanogaster and sheds new light on the connectivity of the Ral, Ras, and Rap pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 1112-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman, A. P., Inoue, T., Wang, M., and Sternberg, P. W. (2000). The Caenorhabditis elegans heterochronic gene lin-29 coordinates the vulval-uterine-epidermal connections. Curr. Biol. 10, 1479-1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuka, T., Hata, Y., Ide, N., Yasuda, T., Inoue, E., Inoue, T., Mizoguchi, A., and Takai, Y. (1999). nRap GEP: a novel neural GDP/GTP exchange protein for rap1 small G protein that interacts with synaptic scaffolding molecule (S-SCAM). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 265, 38-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki, N. et al. (2000). cAMP-GEFII is a direct target of cAMP in regulated exocytosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 805-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak, Y., Pham, N., and Rotin, D. (2002). Direct binding of the beta1 adrenergic receptor to the cyclic AMP-dependent guanine nucleotide exchange factor CNrasGEF leads to Ras activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 7942-7952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettitt, J., Wood, W. B., and Plasterk, R. H. (1996). cdh-3, a gene encoding a member of the cadherin superfamily, functions in epithelial cell morphogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 122, 4149-4157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham, N., Cheglakov, I., Koch, C. A., de Hoog, C. L., Moran, M. F., and Rotin, D. (2000). The guanine nucleotide exchange factor CNrasGEF activates ras in response to cAMP and cGMP. Curr. Biol. 10, 555-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posern, G., Weber, C. K., Rapp, U. R., and Feller, S. M. (1998). Activity of Rap1 is regulated by bombesin, cell adhesion, and cell density in NIH3T3 fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 24297-24300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reedquist, K. A., Ross, E., Koop, E. A., Wolthuis, R. M., Zwartkruis, F. J., van Kooyk, Y., Salmon, M., Buckley, C. D., and Bos, J. L. (2000). The small GTPase, Rap1, mediates CD31-induced integrin adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 148, 1151-1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, B., Clucas, C., and Johnstone, I. L. (2003). Loss of SEC-23 in Caenorhabditis elegans causes defects in oogenesis, morphogenesis, and extracellular matrix secretion. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 4414-4426. Epub 2003 Aug 4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, M., Evellin, S., Weernink, P. A., von Dorp, F., Rehmann, H., Lomasney, J. W., and Jakobs, K. H. (2001). A new phospholipase-C-calcium signalling pathway mediated by cyclic AMP and a Rap GTPase. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 1020-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma-Kishore, R., White, J. G., Southgate, E., and Podbilewicz, B. (1999). Formation of the vulva in Caenorhabditis elegans: a paradigm for organogenesis. Development 126, 691-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimonaka, M., Katagiri, K., Nakayama, T., Fujita, N., Tsuruo, T., Yoshie, O., and Kinashi, T. (2003). Rap1 translates chemokine signals to integrin activation, cell polarization, and motility across vascular endothelium under flow. J. Cell Biol. 161, 417-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R. N. (1978). Some observation on molting in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nematologica 24, 63-71. [Google Scholar]

- Sulston, J. E., and Horvitz, H. R. (1977). Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 56, 110-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto, N., Hattori, M., Yang, H., Bos, J. L., and Minato, N. (1999). Rap1 GTPase-activating protein SPA-1 negatively regulates cell adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 18463-18469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossler, M. R., Yao, H., York, R. D., Pan, M. G., Rim, C. S., and Stork, P. J. (1997). cAMP activates MAP kinase and Elk-1 through a B-Raf- and Rap1-dependent pathway. Cell 89, 73-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way, J. C., Wang, L., Run, J. Q., and Wang, A. (1991). The mec-3 gene contains cis-acting elements mediating positive and negative regulation in cells produced by asymmetric cell division in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 5, 2199-2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yochem, J., Tuck, S., Greenwald, I., and Han, M. (1999). A gp330/megalin-related protein is required in the major epidermis of Caenorhabditis elegans for completion of molting. Development 126, 597-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwartkruis, F. J., Wolthuis, R. M., Nabben, N. M., Franke, B., and Bos, J. L. (1998). Extracellular signal-regulated activation of Rap1 fails to interfere in Ras effector signalling. EMBO J. 17, 5905-5912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]