Abstract

RUNX1 is a member of the core-binding factor family of transcription factors and is indispensable for the establishment of definitive hematopoiesis in vertebrates. RUNX1 is one of the most frequently mutated genes in a variety of hematological malignancies. Germ line mutations in RUNX1 cause familial platelet disorder with associated myeloid malignancies. Somatic mutations and chromosomal rearrangements involving RUNX1 are frequently observed in myelodysplastic syndrome and leukemias of myeloid and lymphoid lineages, that is, acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. More recent studies suggest that the wild-type RUNX1 is required for growth and survival of certain types of leukemia cells. The purpose of this review is to discuss the current status of our understanding about the role of RUNX1 in hematological malignancies.

Introduction

It is timely that Blood publishes a review article on RUNX1 since 2016 marks the 25th anniversary of the identification of RUNX1’s involvement in the t(8;21) translocation in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). In 1991, Miyoshi et al localized the breakpoints on chromosome 21 to a gene called AML1, which was an unknown gene at the time.1 In the following two years, groups led by Nancy Speck and Yoshiaki Ito independently identified and characterized AML1 in the context of Moloney murine leukemia virus and polyomavirus, respectively.2-4 It was shown that AML1, also known as CBFa2 and PEBP2aB, is a mammalian homolog of Drosophila runt, which was cloned and characterized by Peter Gergen in the 1980s.5,6 Therefore, a unifying name “Runt-related transcription factor” or RUNX was proposed and accepted in the field.7 There are three related RUNX genes in the mammalian genomes, RUNX1, RUNX2, and RUNX3. All RUNX proteins contain the runt-homology domain (RHD), which is responsible for DNA-binding and interaction with a common heterodimeric partner, CBFβ. The identification of CBFB as the target of chromosome 16 inversion in human AML by our group in 19938 further indicated this group of genes as key players in leukemia. It has been demonstrated that the RUNX1-RUNX1T1 (aka ETO and MTG8) fusion generated by t(8;21) and the CBFB-MYH11 fusion generated by inv(16) are leukemia initiating or driver mutations.9,10

In addition to t(8;21), more than 50 chromosome translocations affect RUNX1.11 The more common, recurrent translocations include t(12;21) in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and t(3;21) in therapy-related AML and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), which generate ETV6-RUNX1 (also known as TEL-AML1) and RUNX1-MECOM (including MDS1 and EVI1) fusions, respectively.12,13

RUNX1 point mutations in leukemia were first identified in 1999.14 Many subsequent studies documented frequent somatic mutations in RUNX1 in MDS, AML, ALL, and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML).15 Germ line mutations of RUNX1 are associated with familial platelet disorder with associated myeloid malignancy (FPDMM).16

Finally, recent studies suggest that normal RUNX1 plays an important role during leukemogenesis. It has been demonstrated that normal RUNX1 is required for leukemia development by both RUNX1-RUNX1T1 and CBFB-MYH11. Similarly, several reports suggest that RUNX1 is important for mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL). The proposed hypothesis is that wild-type RUNX1 is required for survival of these leukemia cells.17

Here, we provide a comprehensive review of the recent literature describing the ways by which RUNX1 is altered that lead to hematologic diseases, including chromosome translocations, somatic and germ line point mutations, and the potential role of normal RUNX1 in leukemogenesis.

Genomic organization and functional domains of RUNX1

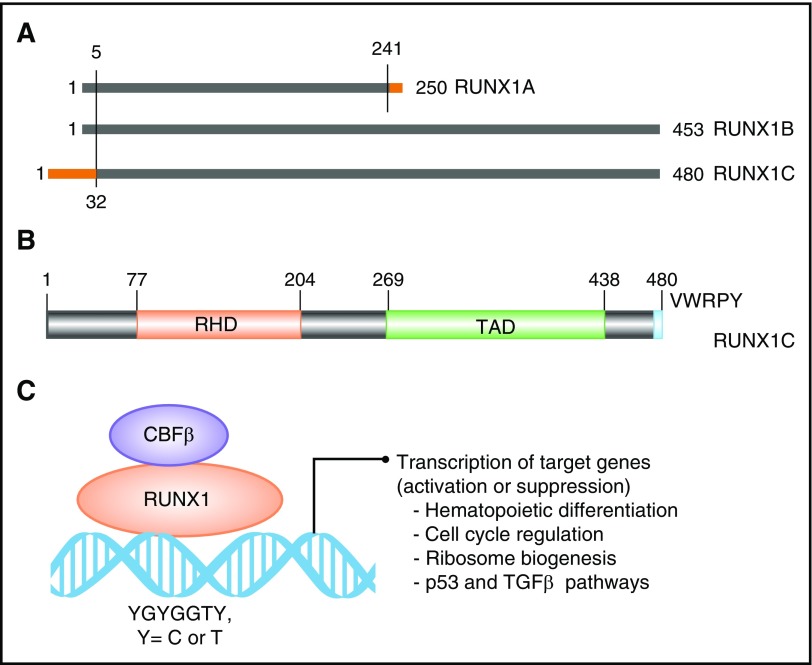

The RUNX1 gene spans ∼261 kb on the long arm of chromosome 21. Three major isoforms are transcribed by use of two promoters and alternative splicing (Figure 1A). Isoforms 1A (250 amino acids) and 1B (453 amino acids) are transcribed from the distal promoter P1 and differ at their carboxyl termini (Figure 1A). Isoform 1C (483 amino acids) is transcribed from the proximal promoter P2 and is identical to isoform 1B except for 32 amino acids encoded by alternative exons at its amino terminus (Figure 1A). The three isoforms are expressed in a temporal and tissue-specific manner. Isoform 1C is expressed at the time of emergence of definitive hematopoietic stem cells, whereas isoforms 1A and 1B are expressed throughout hematopoietic differentiation.18 All 3 isoforms share the conserved 128 amino acid RHD (Figure 1B-C). Isoforms 1B and 1C share another large domain, termed TAD, which consists of activating and inhibitory domains that bind to a number of activating and repressor proteins (Figure 1B). The last five amino acids of isoforms 1B and 1C make the VWRPY motif that interacts with mammalian homolog of Groucho, or TLE1.19 Through interaction with multiple proteins through its domains, RUNX1 controls the expression of its target genes involved in hematopoietic differentiation, ribosome biogenesis, cell cycle regulation, and p53 and transforming growth factor β signaling pathways.20,21

Figure 1.

Domain architect of RUNX1 protein and its role as a transcription factor. (A) A schematic depicting the 3 major isoforms of RUNX1 (1A, 1B, and 1C). Isoforms 1A and 1B are transcribed from P1, and isoform 1C is transcribed from P2, thus differing by 32 amino acids at its 5′ end (marked in orange). Isoform 1A contains only the RHD and differs by 9 amino acids at its 3′ end (marked in orange). (B) Schematic of the protein encoded by the largest isoform, 1C, with major functional domains marked: RHD and transactivation domain (TAD). The numbers above the lines represent the amino acid residues. (C) A schematic of RUNX1 heterodimerization with its binding partner, CBFβ, and interaction with DNA at promoters of target genes that carry the specific binding site: YGYGGTY, where Y is C or T.

RUNX1-RUNX1T1, the fusion gene product of t(8;21)

As mentioned above, RUNX1 and CBFB are frequent targets of chromosome abnormalities in human AML and ALL. In particular, de novo AMLs with translocations affecting either RUNX1 or CBFB are known as core-binding factor (CBF) leukemia. The CBF leukemia chromosomal rearrangements include t(8;21)(q22;q22) in AML subtype M2 and inv(16)(p13.1;q22)/t(16;16)(p13.1;q22) in AML subtype M4Eo.22 Both CBF leukemia subtypes are associated with younger age, with incidence ranging from 20% in pediatric AML23 to less than 5% in older AML.24 Moreover, CBF leukemias are generally associated with relatively good prognosis.

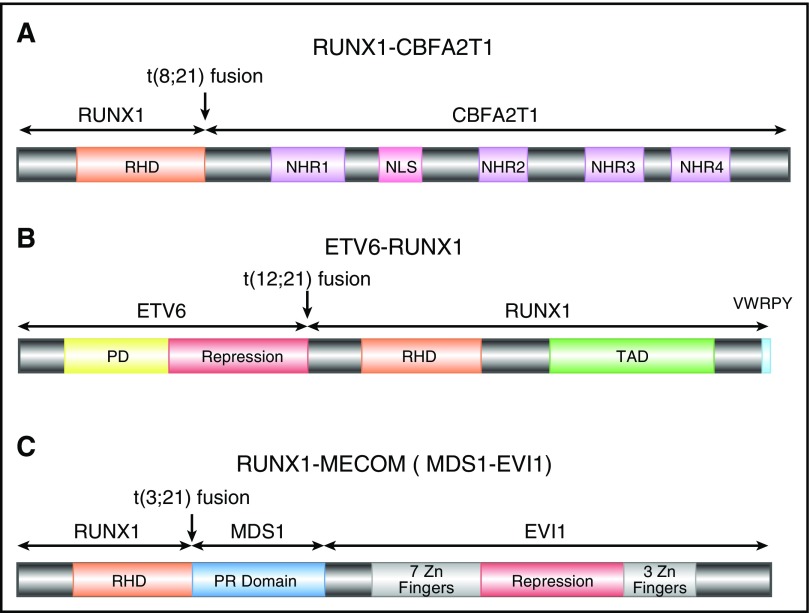

RUNX1-CBFA2T1 (AML1-eight-twenty one oncoprotein [ETO]), the protein product of RUNX1-RUNX1T1, contains the N-terminal 177 amino acids of RUNX1, including the entire RHD, fused with almost the entire CBFA2T1 protein (also known as ETO and myeloid translocation gene on 8q22 [MTG8]) (Figure 2A). CBFA2T1 contains four conserved domains termed nervy homology regions (NHR) 1 to 4.25 NHR2 mediates oligomerization of RUNX1–CBFA2T1, a process that is critical for leukemogenesis.26-28 CBFA2T1 also contains a nuclear localization signal between NHR1 and NHR2.29,30

Figure 2.

Schematics of RUNX1 fusion proteins. (A) Schematic diagram of full-length RUNX1-CBFA2T1, illustrating the site of fusion between the 2 proteins. RUNX1-CBFA2T1 comprises the RHD from RUNX1 and 4 Nervy homology regions (NHR1–4) from CBFA2T1. The location of the nuclear localization signal (NLS) is also indicated. (B) Schematic diagram of ETV6-RUNX1, illustrating the site of fusion between the 2 proteins. The ETV6-RUNX1 fusion protein contains the N-terminal non-DNA binding moiety of ETV6 fused to almost the entire RUNX1 protein, including its RHD and TAD domains, and the VWRPY motif. (C) Schematic diagram of RUNX1-MECOM, illustrating the site of fusion between the 2 proteins. In the RUNX1-MECOM fusion, RUNX1 fuses with one or both of the “MDS1 and EVI1 complex locus” genes present at chromosome 3q26.

Isoforms of RUNX1-RUNX1T1 have been identified because of alternative splicing of RUNX1T1 exons. RUNX1T1 contains 14 exons, including 2 alternative exons, 9a and 11a.31 The RUNX1-CBFA2T19a protein lacks NHR3 and NHR4 domains and therefore has reduced capacity to inhibit RUNX1-mediated transcriptional activation. Surprisingly, RUNX1-CBFA2T19a was a more potent inducer of leukemia than was the full-length RUNX1-CBFA2T1 in mouse models.10 It has been hypothesized that the deleted region inhibits leukemogenic potential of RUNX1-CBFA2T1.10 However, the functional significance of RUNX1-CBFA2T19a in human leukemia remains unclear.

RUNX1-CBFA2T1 interacting proteins

Many RUNX1-CBFA2T1 interacting proteins have been identified. As was predicted, RUNX1-CBFA2T1 interacts with the heterodimeric partner of RUNX1, CBFβ. However, the importance of the CBFβ interaction for leukemogenesis by RUNX1-CBFA2T1 is still not completely resolved.26,32 RUNX1-CBFA2T1 forms a corepressor complex with the nuclear receptor corepressor (NCOR1), histone deacetylase (HDAC1), and SIN3A/HDAC,33-37 which inhibits RUNX1 target genes.38 RUNX1-CBFA2T1 also interacts with transcription coactivators, such as histone acetyltransferases p300 and protein arginine methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1) ,39,40 which may enhance its transcription activation activities. A recent study in the RUNX1-CBFA2T1 leukemic cell line Kasumi-1 showed that RUNX1-CBFA2T1 interacted with coactivators p300 and PRMT1 in physiological conditions, whereas it interacted with corepressors only weakly.41 In addition, RUNX1-CBFA2T1 interacts with E proteins and c-Jun.39,42 RUNX1-CBFA2T1 also binds to GATA1 to dysregulate transcriptional activity of GATA1 by preventing its acetylation.43 Furthermore, RUNX1-CBFA2T1 binds to and inhibits myeloid transcription factors CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha (CEBPA) and PU.1, which leads to global suppression of myeloid gene expression.44-47

Secondary mutations in RUNX1-RUNX1T1 leukemia

Secondary chromosome abnormalities in RUNX1-RUNX1T1 leukemia have been described.48 RUNX1-RUNX1T1 leukemia cells frequently (47%) lose the sex chromosomes (either X or Y). In addition, chromosome 9q deletion and trisomy 8 are relatively common findings in RUNX1-RUNX1T1 leukemia. In fact, del(9q) might be a poor prognostic factor in t(8;21) AML.49-51

KIT, RAS, and fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) are frequently mutated in CBF leukemia.51,52,53 In a recent report, 135 adult patients with RUNX1-RUNX1T1 AML were analyzed for activating mutations involving signal transduction pathways (FLT3-ITD, FLT3-D835, KIT-D816, NRAS codons 12/13/61) and MLL partial tandem duplication (PTD). Strikingly, almost one third of all RUNX1-RUNX1T1 AML patients had mutations affecting RAS pathway, whereas none showed MLL-PTD.48 KIT-D816 mutations had adverse prognostic impact on RUNX1-RUNX1T1 leukemia, whereas the impact of other KIT mutations was less significant.48,52,54 Importantly, most reports suggest an association between these class I mutations55 and worse outcomes in CBF-AML patients.54 In addition, frequent mutations of epigenetic genes, such as ASXL1 and ASXL2, have been found in RUNX1-RUNX1T1 leukemia.48,56 Other genes with frequent mutations include IDH1 and IDH2, identified in approximately 5% of RUNX1-RUNX1T1 leukemia.48

We recently performed whole exome sequencing and single nucleotide polymorphism array analyses of relapsed CBF leukemia to identify mutations that are responsible for relapse.57 In addition to mutations in previously known AML driver genes such as FLT3, KIT, NRAS, and DNMT3A, we found recurrent mutations in DHX15, which encodes an RNA helicase implicated in pre-messenger RNA splicing. Moreover, we found a relapse-specific deletion on chromosome 3, with a minimal overlap region containing 3 genes including GATA2, which is a master regulator of hematopoiesis and also has roles in leukemia.57,58 Our data suggest two potential mechanisms for leukemia relapse, one with a therapy-resistant leukemia clone and the other with a therapy-resistant preleukemia clone, which survived treatments, gained other mutations, and gave rise to relapse.57

Signaling pathways in RUNX1-RUNX1T1 leukemia

Involvement of signaling pathways such as thrombopoietin/myeloproliferative leukemia (TPO/MPL), JAK/STAT, Wnt, and PI3K/AKT in CBF leukemia has been reported. TPO/MPL signaling was important for survival and leukemogenesis by RUNX1-CBFA2T1, likely through upregulating Bcl-xL and activating PI3K/AKT and JAK/STAT pathways.59,60 Loss of CBL function was shown to enhance TPO-mediated proliferation of RUNX1-CBFA2T1 cells.61 RUNX1-CBFA2T1 may upregulate the Wnt signaling pathway,62 through upregulation of γ-catenin.63 In addition, RUNX1-CBFA2T1 upregulates COX-2, which in turn activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling.64 Acetylated RUNX1-CBFA2T1 phosphorylates AKT1 through upregulation of ID1, which interacts with AKT1.65 On the other hand, the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway may be attenuated in RUNX1-RUNX1T1 leukemia.59 It was also reported that NF-κB signaling was inhibited by wild-type RUNX1 through interaction with IκB kinase complex, and RUNX1-CBFA2T1 lost this ability. Consequently, NF-κB signaling was activated in RUNX1-CBFA2T1 cells.66

Dysregulation of tumor suppressors has been observed in RUNX1-RUNX1T1 leukemia. p14ARF (CDKN2A) and NF1 expression were transcriptionally repressed through dominant inhibition of RUNX1 function.67,68 Antiapoptosis genes BCL2 and Bcl-xL are also directly or indirectly upregulated by RUNX1-CBFA2T1.60,69

Specific microRNA signatures in RUNX1-RUNX1T1 leukemia

Recent studies revealed the importance of microRNAs (miRNAs) in the pathogenesis of CBF leukemia. In 2008, 2 groups independently performed the first genome-wide miRNA analyses in CBF leukemia.70,71 In both reports the authors identified signature miRNAs expressed in t(8;21) and inv(16) leukemia, ranging from 2 to 10 in each, that can be used to distinguish them from other types of AML. It was found that miR-126/126* expression was specifically elevated in CBF leukemia, which inhibited apoptosis and increased leukemia cell viability.70

Importantly, miRNAs have been shown to have functional relevance in leukemogenesis, with some miRNAs acting as oncogenes and others as tumor suppressors. Downregulated miRNAs in RUNX1-RUNX1T1 AML, which were shown to act as tumor suppressors, include miR-9,72 miR-223,73 and miR-193a.74 Epigenetic suppression of miR-193a by RUNX1-CBFA2T1 enhances the oncogenic activity of RUNX1-CBFA2T1 by directly enhancing expression of DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A), HDAC3, KIT, CCND1, and MMDM2 and indirectly decreasing phosphatase and tensin homolog.74 On the other hand, miR-24 is downregulated in RUNX1-CBFA2T1 cells.75 Moreover, miR-126 plays a pivotal role in the regulation of leukemic stem cells and therapeutic resistance in RUNX1-RUNX1T1 leukemia.76,77

ETV6-RUNX1 (TEL-AML1) in childhood ALL

The most common chromosome abnormality in childhood ALL is t(12;21), occurring in 17% of the patients78; t(12;21) occurs during B-cell differentiation prior to the onset of immunoglobulin gene rearrangement, giving rise to leukemic blasts that appear to be blocked at the pre-B cell stage79-82. An inframe fusion is generated by t(12;21) between ETV6 (also known as TEL) on chromosome 12 and RUNX1 on chromosome 21 (Figure 2B). ETV6-RUNX1 encodes the N-terminal non-DNA–binding moiety of ETV6 and almost the entire RUNX1 protein.12,79,83

ETV6-RUNX1 is able to dimerize with wild-type ETV684 through interactions between the pointed domains (PD) of both proteins and disrupt ETV6 activity.85 However, the significance of this interaction is not clear, because the wild-type ETV6 allele is lost in many t(12;21) ALL cases.86 Furthermore, ETV6-RUNX1 is able to cooperate with other transcription factors (such as ETS-1, PU.1, and C/EBPα) to drive target gene expression.87,88 The transcriptional activities of ETV6-RUNX1 involve recruitment of NCOR/HDAC complexes to the ETV6 moiety of the fusion protein.89 The PD of ETV6 may be required for repression, which can interact with SIN3A.90 A central repression domain, located between PD and ETS DNA-binding domain, interacts with NCOR1 and HDACs.91-93 It is likely that oligomerization of ETV6 allows for stable formation of repressor–corepressor complexes.94

Studies of identical twins with concordant ALL provide unequivocal evidence that ETV6-RUNX1 arises prenatally.95,96 Monozygotic twins share their blood supplies, so a preleukemia clone arising from one twin will likely be shared with the other twin in utero. Consequently, it has been observed that the leukemia concordance rate for identical twins is much higher than for other sibling combinations, reaching 100% for infant leukemia.96 Molecularly, it has been confirmed that the breakpoints of t(12;21) in the twins are identical to each other,95 consistent with their derivation from a common leukemia clone. Interestingly, twins typically have different sets of secondary mutations in their leukemia cells.97 These findings have led to the hypothesis that ETV6-RUNX1 leads to the generation and expansion of a covert preleukemic clone that can persist for many years before acquiring secondary mutations and producing overt leukemia.96,98

There might not be an exclusive second genetic “hit,” but at diagnosis most cases of ETV6-RUNX1 ALL have deletions of the normal ETV6 allele.99 Deletions are subclonal to ETV6-RUNX1100 and are distinct in their genomic boundaries between twins101 or even between relapse and diagnostic samples from the same individuals.102 Indeed, in 143 ETV6-RUNX1 patient samples analyzed for additional genetic lesions, over half showed complete deletion of the normal ETV6 allele.103 In addition to ETV6, PAX5, which is essential for B-cell commitment, is a frequently mutated gene in ETV6-RUNX1 leukemia.104,105 Deletions have also been found in other genes encoding for transcription factors important for B-cell differentiation and maturation, such as EBF1, IKZF1, E2A, LEF1, and IKZF3.104

Other chromosomal translocations affecting RUNX1

RUNX1 is involved in t(3;21)(q26;q22), which is found in both therapy-related MDS and chronic myeloid leukemia in blast crisis.13 Near the breakpoints on 3q26, there are two genes called EVI1 and MDS1, both of which have been demonstrated to form fusions with RUNX1106,107 (Figure 2C). EVI1 and MDS1 are located close to each other, and some transcripts contain exons from both genes, so they have been recently designated as MECOM, for “MDS1 and EVI1 complex locus.” EVI1 has been recognized as an important player in leukemogenesis. It is involved in other chromosome abnormalities affecting 3q26, and its expression is elevated in many leukemia cases, even those without 3q26 abnormalities, which predict adverse outcome in AML.108

In addition to these relatively common chromosome translocations described above, there are over 50 other translocations that also affect RUNX1.11 However, the partner genes have been identified in less than half of these translocations.11

RUNX1 somatic mutations in MDS

It took 8 years since the first report of RUNX1 involvement in leukemias by chromosomal rearrangements to identify somatic and germ line RUNX1 mutations in MDS, AML without translocations, and FPDMM.14,16 Song and colleagues identified a frameshift mutation in RUNX1 in 1 of 14 patients with sporadic MDS.16 They were unable to categorize the mutation as somatic or inherited because of the lack of corresponding germ line DNA. Subsequently, Imai et al109 demonstrated the somatic nature of RUNX1 mutations in 2 out of 37 MDS patients. Harada et al110 reported an increased incidence of RUNX1 mutations in radiation-associated MDS by screening atomic bomb survivors from Hiroshima who developed MDS. These earlier studies did not screen the entire coding region of RUNX1; therefore, the actual incidence of RUNX1 mutations might be higher than reported in these MDS patients. Subsequently, several studies reported somatic mutations in RUNX1 in patients with primary MDS, therapy-related MDS, and AML from progression of MDS.111-118 RUNX1 mutations also occur in ∼20% of Fanconi anemia and 64% of congenital neutropenia (CN) patients who develop MDS.119,120 RUNX1 mutations in MDS are distributed throughout the gene, affecting both major functional domains. RUNX1 is one of the most frequently mutated genes in MDS, accounting for roughly 10% of the cases.115,118,121

Analysis of 132 primary MDS cases115 revealed a positive correlation between RUNX1 mutations and shorter survival (median survival of 11 months vs 28 months). Tsai et al observed that MDS patients with RUNX1 mutations had a higher risk and shorter latency for progression to AML in comparison with MDS patients without RUNX1 mutations.118 The exact role of RUNX1 in progression of MDS to AML is not known. For MDS cases with mutated RUNX1, it is proposed that secondary cytogenetic changes, particularly deletion of the entire chromosome 7 or its long arm (-7/7q-), and activating mutations in the RTK-RAS pathway lead to leukemic transformation.114-116 Several reports suggest that cooperating mutations in FLT3, MLL, and JAK2 cause leukemic transformation of MDS by providing a growth advantage to RUNX1-mutated hematopoietic progenitors.117,122 Using single-cell genomic analysis, Skokowa and colleagues demonstrated that RUNX1 and CSF3R cooperate during leukemogenesis in CN patients.120 Interestingly, they also identified a germ line RUNX1 mutation in familial CN/AML.

RUNX1 somatic mutations in AML

Osato and colleagues were the first to demonstrate occurrence of somatic point mutations in RUNX1 in patients with cytogenetically normal AML (CN-AML).14 They identified missense and nonsense mutations in RUNX1 in 5 of 109 CN-AML patients. Subsequent screening of additional AML patients revealed especially high frequency of RUNX1 mutations in AML-M0, with 27% of AML-M0 patients showing inactivating RHD mutations.123-127 Interestingly, biallelic RUNX1 mutations were observed in many AML-M0 patients, indicating a complete lack of RUNX1 function in their leukemic cells.123,124 Greif and colleagues identified RUNX1 mutations in ∼16% of patients with CN-AML.128 The mutations represent a broad spectrum of missense, nonsense, and framehshift changes distributed throughout the protein, with a higher frequency in the RHD.128

Overall, somatic mutations in RUNX1 are detected in approximately 3% of pediatric and 15% of adult de novo AML patients.120,125,128-130 They are associated with older age, male gender, and poor prognosis when compared with the RUNX1 wild-type AML patients.120,125,126,128,129 Expression profiling has revealed a distinct gene expression profile in RUNX1-mutated versus RUNX1 wild-type AML samples.128,129,131 Furthermore, RUNX1 mutations are frequently observed together with FLT3-ITD, FLT3-TKD, and MLL-PTD.126,128,131,132 In addition, mutations in other AML driver genes (ASXL1, CEBPA, DNMT3A, NRAS, KIT, IDH1, IDH2, WT1) are also observed in RUNX1-mutated AML samples.128,129,131,132 Interestingly, RUNX1 and NPM1 mutations seem to be mutually exclusive.128,129,131 These studies indicate that leukemogenesis is driven by mutations that provide a growth advantage to the hematopoietic progenitor cells with differentiation defects due to mutated RUNX1. Recent studies have proposed molecular subclassification of AML based on mutation spectrum that would help in choosing the proper treatment options.133,134

RUNX1 somatic mutations in ALL

Recently, several independent studies taking different approaches have identified recurrent somatic mutations in RUNX1 in ALL. First, Grossman and colleagues performed a systematic screening of RUNX1 in 128 ALL patients.135 They identified 17 different RUNX1 mutations distributed throughout the RHD and TAD in 15 patients, 13 with T-ALL (18%) and 2 with B-ALL (7%). Interestingly, 2 of the 13 T-ALL patients had biallelic RUNX1 mutations. They further demonstrated association of RUNX1 mutations with higher age and poor prognosis. Next, Della Gatta et al performed global transcriptional network analysis of T-ALL induced by TLX1 and TLX3 and identified RUNX1 as a key mediator of T-ALL.136 Prompted by their data, they screened T-ALL samples for RUNX1 mutations and identified mutations in 4 out of 12 T-ALL cell lines and 5 out of 114 of T-ALL primary samples. A third study137 performed whole-genome sequencing and identified RUNX1 as one of the recurrently mutated genes (3 out of 12 patients) in patients with ETP-ALL (early T-cell precursor ALL). Screening of additional patients revealed RUNX1 mutations or deletions in 12 cases (10 ETP-ALL and 2 non- ETP-ALL). In these studies, the somatic nature of RUNX1 mutations was demonstrated in patients in whom appropriate germ line samples were available. Furthermore, biallelic mutations were observed in some patients, indicating the role of RUNX1 as a tumor suppressor in ALL.

Familial platelet disorder with predisposition to acute myeloid leukemia (FPDMM)

FPDMM or FPD/AML is a rare autosomal dominant disorder with clinical symptoms of mild-to-moderate thrombocytopenia, platelet dysfunction, bleeding propensity, and a significant risk of hematological malignancies, especially MDS and AML. In 1969, Weiss and colleagues138 described the first multigenerational pedigree with symptoms of FPD/AML. Subsequent studies identified additional families with similar clinical symptoms and performed linkage analysis and mutation screening to identify germ line mutations in RUNX1 as the cause of FPD/AML.16,139-142 To date, more than 70 FPD/AML families with inherited RUNX1 mutations have been identified (Table 1). At least one family is reported with symptoms of FPD/AML without a RUNX1 mutation.143 Stockley and colleagues described RUNX1 mutations in 3 families with a phenotype of reduced platelet dense-granule secretion.144 It is not clear whether these families represent a spectrum of FPD/AML phenotype or have a different inherited platelet disorder due to RUNX1 mutations. In addition to the inherited mutations, de novo RUNX1 mutations were reported recently in patients with thrombocytopenia without a family history of FPD/AML.145,146 A de novo translocation, t(16;21)(p13;q22), with a breakpoint in intron 1 of RUNX1, was reported in a patient with storage pool disease, thrombocytopenia, and AML.147

Table 1.

Inherited RUNX1 mutations in FPD/AML families

| Reference | No. of families | Family ID* | RUNX1 mutation (on isoform C) | Hematological malignancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 6 | 1 | Large deletion | AML |

| 2 | V118GfsX11 | AML | ||

| 3 | R204X | AML | ||

| 4 | R201X | AML | ||

| 5 | R201Q | AML | ||

| 6 | R166Q | AML | ||

| 193 | 1 | D198Y | MDS, AML | |

| 148 | 3 | 1 | K110E | Myeloblastic leukemia |

| 2 | R162fsX | AML | ||

| 3 | Y287X | AML | ||

| 194 | 1 | A134P | AML | |

| 143 | 1 | None† | MDS, AML | |

| 195 | 1 | V118GfsX11 | AML | |

| 196, 197, 164 | 1 | T246RfsX8 | CMML, AML | |

| 198 | 1 | T148HfsX9 | AML | |

| 199 | 1 | F330SfsX | MDS | |

| 151 | 5 | A | G363fsX227 | MDS, AML, ALL |

| B | A55fsX81 | AML | ||

| C | D123H | AML | ||

| D | K117fsX101 | MDS, AML, CMML | ||

| E | R320X | MDS, AML | ||

| 200 | 1 | P263LfsX48 | AML | |

| 162 | 1 | R201X | MDS, AML | |

| 163 | 4 | 1 | A156E | AML |

| 2 | R204Q | AML, T-ALL | ||

| 3 | Q335RfsX259 | AML, T-ALL | ||

| 4 | Large deletion | MDS, AML | ||

| 149 | 1 | S388X | MDS, AML | |

| 170 | 2 | 1 | Duplication of exons 2-6 | AML |

| 2 | Deletion of 35 amino acids | MDS, AML | ||

| 153 | 1 | R201X | AML, T-ALL | |

| 150, 165, 164 | 2 | A | R201Q | MDS, AML, T-ALL |

| B | R166X | AML | ||

| 147 | 3 | 1 | G170R | MDS, AML |

| 2 | Q262X | MDS, AML | ||

| 3 | t(16;21)(p13;q22) (de novo) | MDS, AML | ||

| 154 | 1 | G289fsX21 | MDS, CMML | |

| 201 | 1 | L472fsX123 | MDS, AML | |

| 159 | 3 | 1 | G199E | None |

| 2 | G170W | MDS, AML | ||

| 3 | N260fsX50 | MDS, AML | ||

| 155 | 1 | L472P | AML, HCL | |

| 166 | 7 | 16 | N260fs | None |

| 18 | F330fs | MDS, AML | ||

| 19 | R201X | AML | ||

| 32 | L472P | HCL | ||

| 53 | G289fs | MDS | ||

| 54 | S167N | MDS, AML | ||

| 57 | G199E | None | ||

| 168 | 1 | R166X | AML | |

| 145 | 4 | 4 | V118GfsX6 | None |

| 5 | R166Q (de novo) | None | ||

| 6 | D198N (de novo) | None | ||

| 7 | R201PfsX12 | None | ||

| 171 | 9 | A | R107H | AML |

| B | A156E | AML | ||

| C | R201Q | AML, T-ALL | ||

| D | R204Q | AML, T-ALL | ||

| E | T196R | MDS, AML | ||

| F | Q335RfsX261 | AML, T-ALL | ||

| G | I364MfsX230 | None | ||

| H | T148HfsX9 | AML | ||

| I | R166X | AML | ||

| 202 | 1 | W279X | None | |

| 164 | 8 | 5 | P245S | None |

| 6 | G135V | T-ALL | ||

| 7 | D332TfsX | AML | ||

| 8 | H404PfsX | AML | ||

| 9 | G135V | None | ||

| 10 | G170RfsX | AML | ||

| 11 | T196R | None | ||

| 14 | T148HfsX | AML | ||

| 172 | 2 | 32 | L472P | HCL |

| 58 | N465K | MDS |

Identification of each pedigree is based on the publication describing it.

Family without RUNX1 mutations.

Most FPD/AML patients carry point mutations or small indels in RUNX1 that cause missense, nonsense, or frameshift changes in the protein (Table 1). A few cases with large intragenic deletions and duplications have also been reported (Table 1). Interestingly, mutations are clustered in the RHD and TAD domains with a few exceptions (Table 1, Figure 1). Each FPD/AML pedigree carries a unique mutation, and recurrent mutations are observed in only a few amino acid residues (Table 1). Functional studies showed that most mutations are dominant-negative, loss of function, or hypermorphic.148-150 In general, missense and nonsense mutations are dominant-negative, whereas frameshift mutations and large deletions are loss of function, leading to haploinsufficiency. The broad spectrum of mutations and their effects on RUNX1 function indicate that a proper RUNX1 dosage is critical for thrombocyte differentiation.

Overall lifetime risk of MDS and AML in FPD patients is 35% to 40%, and average age of onset is 33 years (range, 6–77 years).151,152 In addition, FPD/AML patients may develop other types of leukemias, such as T-ALL, Hairy cell leukemia (HCL), and CMML.151,153-155 Interestingly, higher incidence of MDS and AML have been observed in families with certain types of mutations.148,151 The exact mechanism of thrombocytopenia and leukemia in FPD/AML patients is not clear. Animal models (mouse and zebrafish) with heterozygous RUNX1 knockout alleles do not display FPD/AML phenotypes.156,157 Therefore, we and others have generated induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from FPD/AML patients to study disease mechanism.158-161 Together, these studies demonstrated that megakaryopoiesis defects in FPD/AML patients are caused by RUNX1 mutations.

RUNX1 mutations in FPD/AML patients are not sufficient for leukemogenesis. Progression to malignant disease likely occurs by acquisition of additional somatic mutations followed by clonal evolution.162 Several studies have identified loss-of- function somatic mutations in the normal RUNX1 allele as a frequent second hit during leukemogenesis in FPD/AML patients.146,163,164 Antony-Debre and colleagues reported trisomy 21 with duplication of the RUNX1-mutated chromosome or loss of the normal RUNX1 allele in 5 FPD/AML families.164 It is proposed that complete loss of RUNX1 function, either by somatic mutations of the normal copy or by dominant-negative function of the inherited mutations, leads to genome instability.160 In addition, cooperating somatic mutations in more than 20 genes and copy number changes are observed in MDS and leukemic samples from FPD/AML patients.154,155,162,164-169 ASXL1, CBL, CDC25C, FLT3, PHF6, SRSF2, and WT1 were identified as recurrently mutated genes. Additional studies using unbiased genomic approaches are required to identify recurrently mutated genes that cooperate with RUNX1.

Diagnosis of FPD/AML can be missed, because not all patients display clinical symptoms until the malignant disease develops.151,170-172 Furthermore, anticipation leads to occurrence of MDS and AML in younger individuals in subsequent generations. Therefore, a molecular diagnosis by sequencing of all RUNX1 coding exons and copy number analysis for deletions is recommended in families with young patients with MDS and AML.167,170,173 This is of particular concern if bone marrow transplantation from a presumably healthy family member is considered for the treatment of disease. The ability to correct RUNX1 mutation in iPSCs by genome-editing technology may open new avenues for gene therapy in FPD/AML patients in the near future.158,161

Requirement of normal RUNX1 for leukemogenesis

In recent years there is an increasing recognition of the importance of normal RUNX1, as well as its heterodimeric partner, CBFβ, in leukemogenesis.

The story starts with CBF leukemia, those with RUNX1-RUNX1T1 and CBFB-MYH11 fusion genes. The initial hint came from clinical sequencing studies, which showed that RUNX1 mutations do not occur in CBF leukemia patients, even though such mutations are relatively common in other subtypes of AML.125,131,174 Experimentally, RUNX1-RUNX1T1 and CBFB-MYH11 were initially thought to induce leukemia through inhibiting normal RUNX1/CBFB, because Runx1-Runx1t1 and Cbfb-MYH11 knockin mice had embryonic hematopoietic defects similar to those found in Runx1−/− and Cbfb−/− embryos.175,176 Molecular studies seemed to support a RUNX1 dominant suppression mechanism for the fusion genes as well.177-179 However, more recent studies revealed a complicated picture, because both fusion genes were found to have RUNX1-independent functions. For example, Cbfb-MYH11 knockin embryos have defects in primitive hematopoiesis, which is absent in Runx1−/− and Cbfb−/− embryos.175,180 Moreover, it was found that the dysregulated genes by Cbfb-MYH11 were quite different from those dysregulated in Runx1−/− and Cbfb−/− mice.180 More important, Cbfb-MYH11 knockin mice with a mutated Runx1 developed leukemia much more slowly than did those with wild-type Runx1.181 These data suggest that normal Runx1 is required for leukemogenesis by Cbfb-MYH11. Interestingly, RUNX1 knockdown in ME-1, a cell line derived from an inv(16) patient, led to significant apoptosis.17

Similar findings have been reported for the RUNX1 requirement in leukemia cells with RUNX1-RUNX1T1. Ben-Ami and colleagues showed that the t(8;21) leukemia cell line, Kasumi-1, required normal RUNX1 for survival.17 They believed that a delicate balance between the wild-type RUNX1 and RUNX1-RUNX1T1 is important for leukemia cell survival. Similarly, in a model for leukemogenesis using human CD34+ cells transduced with leukemia fusion genes, Goyama and colleagues showed that wild-type RUNX1 is required for RUNX1-RUNX1T1–expressing cells to grow.182 Moreover, Ptasinska and colleagues demonstrated that transcriptional network in t(8;21) leukemia cells is regulated by a dynamic equilibrium between RUNX1-CBFA2T1 and RUNX1 complexes, which compete for binding of identical DNA target sites.46 Li and colleagues showed that RUNX1 was a member of the transcription factor complex containing RUNX1-CBFA2T1, and the relative binding signals of RUNX1 and RUNX1- CBFA2T1 on chromatin determine which genes are repressed or activated by RUNX1- CBFA2T1.39 Recently, Staber and colleagues demonstrated that functional RUNX proteins are required for maintaining an adequate level of PU.1 in hematopoietic cells, which is important for leukemia development by RUNX1-RUNX1T1 in a murine transplantation model.183

Interestingly, Goyama and colleagues found that RUNX1 may also be required by leukemia cells with MLL fusion genes.182 Knocking down RUNX1 in human CD34+ cells transduced with MLL-AF9 inhibited the growth of these cells in culture. Moreover, inhibition of RUNX1, either through short hairpin RNA knockdown or a RUNX1 chemical inhibitor, Ro5-3335,184 suppressed leukemia development by MLL-AF9 in a mouse model. They also found that additional MLL fusion genes require RUNX1 for leukemogenesis.182

Another recent study by Wilkinson et al185 showed that RUNX1 is a direct target of MLL-AF4. RUNX1 is overexpressed in primary ALLs with the MLL-AF4 fusion gene,185,186 and knocking down MLL-AF4 leads to downregulation of RUNX1 expression. Moreover, RUNX1 is required for the growth of MLL-AF4 leukemia cells.185 In addition, it was found that high RUNX1 expression correlates with a poor clinical outcome in ALL patients with MLL fusion genes.185

The impact of normal RUNX1 on other hematologic malignancies is still unclear. There was a recent study suggesting that high RUNX1 expression is associated with poor prognosis in CN-AML.187 The authors analyzed several publicly available datasets and determined that RUNX1 expression is markedly higher in CN-AML than in normal bone marrow. They also compared the molecular characteristics and clinical outcome of 157 CN-AML patients between RUNX1high and RUNX1low groups. They showed that RUNX1high patients were more likely to carry FLT3-ITD but no CEBPA mutations, and the RUNX1high patients had poorer overall survival and event-free survival. The association between RUNX1 expression level and disease outcome was validated in a separate dataset from 162 CN-AML patients. Further studies and experimental tests need to be carried out to validate these findings and understand the underlying mechanisms.

Concluding remarks

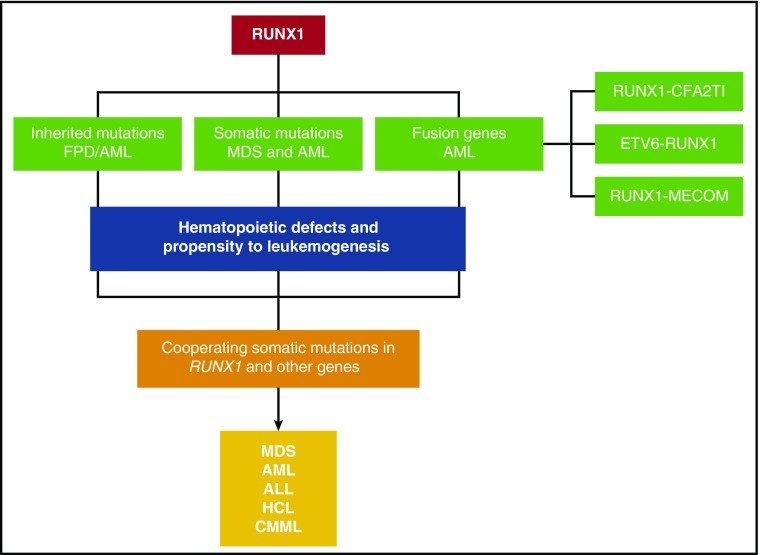

From this review it is clear that RUNX1 is a major player in hematologic malignancies (Figure 3). In general, mutations (both somatic and inherited) are loss of function or dominant-negative. RUNX1 fusion proteins are able to dominantly repress RUNX1 function as well. On the basis of recent molecular studies, it seems that RUNX1 is part of a transcriptional complex that regulates important target genes in hematopoiesis, whereas mutated RUNX1 or RUNX1 fusion proteins disrupt the balance or composition of such a complex. Recent studies suggest that wild-type RUNX1 may also play an active role in leukemia development, at least in the case of CBF leukemia and certain types of MLL leukemia. These findings are consistent with recent observations that other transcription factors such as PU.1, GATA1, and CEBPA also play roles during leukemogenesis.188-190 Overall, these findings all underscore the importance of RUNX1 in maintaining normal hematopoiesis and preventing the development of malignancy.

Figure 3.

A schematic depicting the various mechanisms by which RUNX1 gene is altered in hematological malignancies. Inherited mutations cause FPD/AML. Somatic mutations and fusion genes with cooperating mutations in other genes cause hematological malignancies, such as MDS, AML, ALL, HCL, and CMML.

RUNX1 sits at the top of the hematopoietic differentiation cascade. The high incidence of RUNX1 somatic mutations in multiple types of hematologic malignancies provides strong support for its essential function in maintaining the proper balance between lineage-specific progenitors during hematopoietic differentiation. The key question that remains to be answered is what mechanisms underlie leukemogenesis and how they can be harnessed to develop potential targeted therapies for these patients. In comparison with the large numbers of publications reporting RUNX1 mutations in various hematological malignancies, there have been only a few papers that study the underlying mechanisms using in vitro or in vivo models.109,148,191,192 Part of the reason for this lack of mechanistic studies of RUNX1 mutations is the lack of suitable animal models. A similar issue exists for the study of FPDMM, because mice and zebrafish heterozygous for RUNX1 knockout mutations do not display the FPDMM phenotype. The application of human-induced pluripotent stem cells and human CD34+ cells as models and the recently developed genome-editing technologies such as CRISPR-Cas9 will, we hope, accelerate the studies of these important mutations, leading to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of leukemia and the next generations of targeted treatments.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Julia Fekecs for the expert design of the figures.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: R.S. wrote the sections on RUNX1 mutations in MDS, AML, ALL, and FPDMM; Y.K. wrote the sections on RUNX1-RUNX1T1, ETV6-RUNX1, and other chromosome translocations affecting RUNX1; P.L. wrote the “Introduction,” the section on the requirement of normal RUNX1 in leukemogenesis, and the “Concluding remarks,” and performed the overall editing of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Paul Liu, 49 Convent Dr, Building 49, Room 3A26, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: pliu@mail.nih.gov.

References

- 1.Miyoshi H, Shimizu K, Kozu T, Maseki N, Kaneko Y, Ohki M. t(8;21) breakpoints on chromosome 21 in acute myeloid leukemia are clustered within a limited region of a single gene, AML1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(23):10431-10434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang S, Wang Q, Crute BE, Melnikova IN, Keller SR, Speck NA. Cloning and characterization of subunits of the T-cell receptor and murine leukemia virus enhancer core-binding factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13(6):3324-3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bae SC, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Ogawa E, et al. Isolation of PEBP2 alpha B cDNA representing the mouse homolog of human acute myeloid leukemia gene, AML1. Oncogene. 1993;8(3):809-814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogawa E, Maruyama M, Kagoshima H, et al. PEBP2/PEA2 represents a family of transcription factors homologous to the products of the Drosophila runt gene and the human AML1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(14):6859-6863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gergen JP, Wieschaus EF. The localized requirements for a gene affecting segmentation in Drosophila: analysis of larvae mosaic for runt. Dev Biol. 1985;109(2):321-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gergen JP, Butler BA. Isolation of the Drosophila segmentation gene runt and analysis of its expression during embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 1988;2(9):1179-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS, Gergen JP, et al. Nomenclature for Runt-related (RUNX) proteins. Oncogene. 2004;23(24):4209-4210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu P, Tarlé SA, Hajra A, et al. Fusion between transcription factor CBF beta/PEBP2 beta and a myosin heavy chain in acute myeloid leukemia. Science. 1993;261(5124):1041-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castilla LH, Garrett L, Adya N, et al. The fusion gene Cbfb-MYH11 blocks myeloid differentiation and predisposes mice to acute myelomonocytic leukaemia. Nat Genet. 1999;23(2):144-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan M, Kanbe E, Peterson LF, et al. A previously unidentified alternatively spliced isoform of t(8;21) transcript promotes leukemogenesis. Nat Med. 2006;12(8):945-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Braekeleer E, Douet-Guilbert N, Morel F, Le Bris MJ, Férec C, De Braekeleer M. RUNX1 translocations and fusion genes in malignant hemopathies. Future Oncol. 2011;7(1):77-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golub TR, Barker GF, Bohlander SK, et al. Fusion of the TEL gene on 12p13 to the AML1 gene on 21q22 in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(11):4917-4921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nucifora G, Begy CR, Kobayashi H, et al. Consistent intergenic splicing and production of multiple transcripts between AML1 at 21q22 and unrelated genes at 3q26 in (3;21)(q26;q22) translocations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(9):4004-4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osato M, Asou N, Abdalla E, et al. Biallelic and heterozygous point mutations in the runt domain of the AML1/PEBP2alphaB gene associated with myeloblastic leukemias. Blood. 1999;93(6):1817-1824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osato M. Point mutations in the RUNX1/AML1 gene: another actor in RUNX leukemia. Oncogene. 2004;23(24):4284-4296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song WJ, Sullivan MG, Legare RD, et al. Haploinsufficiency of CBFA2 causes familial thrombocytopenia with propensity to develop acute myelogenous leukaemia. Nat Genet. 1999;23(2):166-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ben-Ami O, Friedman D, Leshkowitz D, et al. Addiction of t(8;21) and inv(16) acute myeloid leukemia to native RUNX1. Cell Reports. 2013;4(6):1131-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Challen GA, Goodell MA. Runx1 isoforms show differential expression patterns during hematopoietic development but have similar functional effects in adult hematopoietic stem cells. Exp Hematol. 2010;38(5):403-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imai Y, Kurokawa M, Tanaka K, et al. TLE, the human homolog of groucho, interacts with AML1 and acts as a repressor of AML1-induced transactivation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;252(3):582-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chuang LS, Ito K, Ito Y. RUNX family: regulation and diversification of roles through interacting proteins. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(6):1260-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai X, Gao L, Teng L, et al. Runx1 deficiency decreases ribosome biogenesis and confers stress resistance to hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17(2):165-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paschka P, Dohner K. Core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemia: can we improve on HiDAC consolidation? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:209-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ravindranath Y, Chang M, Steuber CP, et al. ; Pediatric Oncology Group. Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) studies of acute myeloid leukemia (AML): a review of four consecutive childhood AML trials conducted between 1981 and 2000. Leukemia. 2005;19(12):2101-2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grimwade D, Walker H, Harrison G, et al. ; Medical Research Council Adult Leukemia Working Party. The predictive value of hierarchical cytogenetic classification in older adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML): analysis of 1065 patients entered into the United Kingdom Medical Research Council AML11 trial. Blood. 2001;98(5):1312-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis JN, McGhee L, Meyers S. The ETO (MTG8) gene family. Gene. 2003;303:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwok C, Zeisig BB, Qiu J, Dong S, So CW. Transforming activity of AML1-ETO is independent of CBFbeta and ETO interaction but requires formation of homo-oligomeric complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(8):2853-2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan M, Ahn EY, Hiebert SW, Zhang DE. RUNX1/AML1 DNA-binding domain and ETO/MTG8 NHR2-dimerization domain are critical to AML1-ETO9a leukemogenesis. Blood. 2009;113(4):883-886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Cheney MD, Gaudet JJ, et al. The tetramer structure of the Nervy homology two domain, NHR2, is critical for AML1/ETO’s activity. Cancer Cell. 2006;9(4):249-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barseguian K, Lutterbach B, Hiebert SW, et al. Multiple subnuclear targeting signals of the leukemia-related AML1/ETO and ETO repressor proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(24):15434-15439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Odaka Y, Mally A, Elliott LT, Meyers S. Nuclear import and subnuclear localization of the proto-oncoprotein ETO (MTG8). Oncogene. 2000;19(32):3584-3597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolford JK, Prochazka M. Structure and expression of the human MTG8/ETO gene. Gene. 1998;212(1):103-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roudaia L, Cheney MD, Manuylova E, et al. CBFbeta is critical for AML1-ETO and TEL-AML1 activity. Blood. 2009;113(13):3070-3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gelmetti V, Zhang J, Fanelli M, Minucci S, Pelicci PG, Lazar MA. Aberrant recruitment of the nuclear receptor corepressor-histone deacetylase complex by the acute myeloid leukemia fusion partner ETO. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(12):7185-7191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lutterbach B, Westendorf JJ, Linggi B, et al. ETO, a target of t(8;21) in acute leukemia, interacts with the N-CoR and mSin3 corepressors. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(12):7176-7184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang J, Hoshino T, Redner RL, Kajigaya S, Liu JM. ETO, fusion partner in t(8;21) acute myeloid leukemia, represses transcription by interaction with the human N-CoR/mSin3/HDAC1 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(18):10860-10865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amann JM, Nip J, Strom DK, et al. ETO, a target of t(8;21) in acute leukemia, makes distinct contacts with multiple histone deacetylases and binds mSin3A through its oligomerization domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(19):6470-6483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hildebrand D, Tiefenbach J, Heinzel T, Grez M, Maurer AB. Multiple regions of ETO cooperate in transcriptional repression. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(13):9889-9895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuchenbauer F, Feuring-Buske M, Buske C. AML1-ETO needs a partner: new insights into the pathogenesis of t(8;21) leukemia. Cell Cycle. 2005;4(12):1716-1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y, Wang H, Wang X, et al. Genome-wide studies identify a novel interplay between AML1 and AML1/ETO in t(8;21) acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(2):233-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shia WJ, Okumura AJ, Yan M, et al. PRMT1 interacts with AML1-ETO to promote its transcriptional activation and progenitor cell proliferative potential. Blood. 2012;119(21):4953-4962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun XJ, Wang Z, Wang L, et al. A stable transcription factor complex nucleated by oligomeric AML1-ETO controls leukaemogenesis. Nature. 2013;500(7460):93-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang J, Kalkum M, Yamamura S, Chait BT, Roeder RG. E protein silencing by the leukemogenic AML1-ETO fusion protein. Science. 2004;305(5688):1286-1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi Y, Elagib KE, Delehanty LL, Goldfarb AN. Erythroid inhibition by the leukemic fusion AML1-ETO is associated with impaired acetylation of the major erythroid transcription factor GATA-1. Cancer Res. 2006;66(6):2990-2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vangala RK, Heiss-Neumann MS, Rangatia JS, et al. The myeloid master regulator transcription factor PU.1 is inactivated by AML1-ETO in t(8;21) myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2003;101(1):270-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pabst T, Mueller BU, Harakawa N, et al. AML1-ETO downregulates the granulocytic differentiation factor C/EBPalpha in t(8;21) myeloid leukemia. Nat Med. 2001;7(4):444-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ptasinska A, Assi SA, Martinez-Soria N, et al. Identification of a dynamic core transcriptional network in t(8;21) AML that regulates differentiation block and self-renewal. Cell Reports. 2014;8(6):1974-1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hiebert S. Differentiation or leukemia: is C/EBPalpha the answer? Nat Med. 2001;7(4):407-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krauth MT, Eder C, Alpermann T, et al. High number of additional genetic lesions in acute myeloid leukemia with t(8;21)/RUNX1-RUNX1T1: frequency and impact on clinical outcome. Leukemia. 2014;28(7):1449-1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marcucci G, Mrózek K, Ruppert AS, et al. Prognostic factors and outcome of core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia patients with t(8;21) differ from those of patients with inv(16): a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5705-5717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schlenk RF, Benner A, Krauter J, et al. Individual patient data-based meta-analysis of patients aged 16 to 60 years with core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia: a survey of the German Acute Myeloid Leukemia Intergroup. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(18):3741-3750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wakita S, Yamaguchi H, Miyake K, et al. Importance of c-kit mutation detection method sensitivity in prognostic analyses of t(8;21)(q22;q22) acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25(9):1423-1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qin YZ, Zhu HH, Jiang Q, et al. Prevalence and prognostic significance of c-KIT mutations in core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia: a comprehensive large-scale study from a single Chinese center. Leuk Res. 2014;38(12):1435-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chou FS, Wunderlich M, Griesinger A, Mulloy JC. N-Ras(G12D) induces features of stepwise transformation in preleukemic human umbilical cord blood cultures expressing the AML1-ETO fusion gene. Blood. 2011;117(7):2237-2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tokumasu M, Murata C, Shimada A, et al. Adverse prognostic impact of KIT mutations in childhood CBF-AML: the results of the Japanese Pediatric Leukemia/Lymphoma Study Group AML-05 trial. Leukemia. 2015;29(12):2438-2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gilliland DG. Molecular genetics of human leukemias: new insights into therapy. Semin Hematol. 2002;39(4 Suppl 3):6-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Micol JB, Duployez N, Boissel N, et al. Frequent ASXL2 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia patients with t(8;21)/RUNX1-RUNX1T1 chromosomal translocations. Blood. 2014;124(9):1445-1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sood R, Hansen NF, Donovan FX, et al. Somatic mutational landscape of AML with inv(16) or t(8;21) identifies patterns of clonal evolution in relapse leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30(2):501-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hyde RK, Liu PP. GATA2 mutations lead to MDS and AML. Nat Genet. 2011;43(10):926-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pulikkan JA, Madera D, Xue L, et al. Thrombopoietin/MPL participates in initiating and maintaining RUNX1-ETO acute myeloid leukemia via PI3K/AKT signaling. Blood. 2012;120(4):868-879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chou FS, Griesinger A, Wunderlich M, et al. The thrombopoietin/MPL/Bcl-xL pathway is essential for survival and self-renewal in human preleukemia induced by AML1-ETO. Blood. 2012;120(4):709-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goyama S, Schibler J, Gasilina A, et al. UBASH3B/Sts-1-CBL axis regulates myeloid proliferation in human preleukemia induced by AML1-ETO. Leukemia. 2016;30(3):728-739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Steffen B, Knop M, Bergholz U, et al. AML1/ETO induces self-renewal in hematopoietic progenitor cells via the Groucho-related amino-terminal AES protein. Blood. 2011;117(16):4328-4337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zheng X, Beissert T, Kukoc-Zivojnov N, et al. Gamma-catenin contributes to leukemogenesis induced by AML-associated translocation products by increasing the self-renewal of very primitive progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;103(9):3535-3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang Y, Wang J, Wheat J, et al. AML1-ETO mediates hematopoietic self-renewal and leukemogenesis through a COX/β-catenin signaling pathway. Blood. 2013;121(24):4906-4916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang L, Man N, Sun XJ, et al. Regulation of AKT signaling by Id1 controls t(8;21) leukemia initiation and progression. Blood. 2015;126(5):640-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nakagawa M, Shimabe M, Watanabe-Okochi N, et al. AML1/RUNX1 functions as a cytoplasmic attenuator of NF-κB signaling in the repression of myeloid tumors. Blood. 2011;118(25):6626-6637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Linggi B, Müller-Tidow C, van de Locht L, et al. The t(8;21) fusion protein, AML1 ETO, specifically represses the transcription of the p14(ARF) tumor suppressor in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Med. 2002;8(7):743-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang G, Khalaf W, van de Locht L, et al. Transcriptional repression of the neurofibromatosis-1 tumor suppressor by the t(8;21) fusion protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(14):5869-5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Klampfer L, Zhang J, Zelenetz AO, Uchida H, Nimer SD. The AML1/ETO fusion protein activates transcription of BCL-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(24):14059-14064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li Z, Lu J, Sun M, et al. Distinct microRNA expression profiles in acute myeloid leukemia with common translocations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(40):15535-15540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jongen-Lavrencic M, Sun SM, Dijkstra MK, Valk PJ, Löwenberg B. MicroRNA expression profiling in relation to the genetic heterogeneity of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;111(10):5078-5085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Emmrich S, Katsman-Kuipers JE, Henke K, et al. miR-9 is a tumor suppressor in pediatric AML with t(8;21). Leukemia. 2014;28(5):1022-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fazi F, Racanicchi S, Zardo G, et al. Epigenetic silencing of the myelopoiesis regulator microRNA-223 by the AML1/ETO oncoprotein. Cancer Cell. 2007;12(5):457-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li Y, Gao L, Luo X, et al. Epigenetic silencing of microRNA-193a contributes to leukemogenesis in t(8;21) acute myeloid leukemia by activating the PTEN/PI3K signal pathway. Blood. 2013;121(3):499-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zaidi SK, Dowdy CR, van Wijnen AJ, et al. Altered Runx1 subnuclear targeting enhances myeloid cell proliferation and blocks differentiation by activating a miR-24/MKP-7/MAPK network. Cancer Res. 2009;69(21):8249-8255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li Z, Chen P, Su R, et al. Overexpression and knockout of miR-126 both promote leukemogenesis. Blood. 2015;126(17):2005-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lechman ER, Gentner B, Ng SW, et al. miR-126 regulates distinct self-renewal outcomes in normal and malignant hematopoietic stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(4):602-606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jamil A, Theil KS, Kahwash S, Ruymann FB, Klopfenstein KJ. TEL/AML-1 fusion gene. its frequency and prognostic significance in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2000;122(2):73-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Romana SP, Mauchauffé M, Le Coniat M, et al. The t(12;21) of acute lymphoblastic leukemia results in a tel-AML1 gene fusion. Blood. 1995;85(12):3662-3670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hotfilder M, Röttgers S, Rosemann A, Jürgens H, Harbott J, Vormoor J. Immature CD34+CD19- progenitor/stem cells in TEL/AML1-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia are genetically and functionally normal. Blood. 2002;100(2):640-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pine SR, Wiemels JL, Jayabose S, Sandoval C. TEL-AML1 fusion precedes differentiation to pre-B cells in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Res. 2003;27(2):155-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Panzer-Grümayer ER, Cazzaniga G, van der Velden VH, et al. Immunogenotype changes prevail in relapses of young children with TEL-AML1-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia and derive mainly from clonal selection. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(21):7720-7727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shurtleff SA, Buijs A, Behm FG, et al. TEL/AML1 fusion resulting from a cryptic t(12;21) is the most common genetic lesion in pediatric ALL and defines a subgroup of patients with an excellent prognosis. Leukemia. 1995;9(12):1985-1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McLean TW, Ringold S, Neuberg D, et al. TEL/AML-1 dimerizes and is associated with a favorable outcome in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1996;88(11):4252-4258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gunji H, Waga K, Nakamura F, et al. TEL/AML1 shows dominant-negative effects over TEL as well as AML1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;322(2):623-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cavé H, Cacheux V, Raynaud S, et al. ETV6 is the target of chromosome 12p deletions in t(12;21) childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 1997;11(9):1459-1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wotton D, Ghysdael J, Wang S, Speck NA, Owen MJ. Cooperative binding of Ets-1 and core binding factor to DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14(1):840-850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Petrovick MS, Hiebert SW, Friedman AD, Hetherington CJ, Tenen DG, Zhang DE. Multiple functional domains of AML1: PU.1 and C/EBPalpha synergize with different regions of AML1. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(7):3915-3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zelent A, Greaves M, Enver T. Role of the TEL-AML1 fusion gene in the molecular pathogenesis of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Oncogene. 2004;23(24):4275-4283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lopez RG, Carron C, Oury C, Gardellin P, Bernard O, Ghysdael J. TEL is a sequence-specific transcriptional repressor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(42):30132-30138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fenrick R, Amann JM, Lutterbach B, et al. Both TEL and AML-1 contribute repression domains to the t(12;21) fusion protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(10):6566-6574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Guidez F, Petrie K, Ford AM, et al. Recruitment of the nuclear receptor corepressor N-CoR by the TEL moiety of the childhood leukemia-associated TEL-AML1 oncoprotein. Blood. 2000;96(7):2557-2561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang L, Hiebert SW. TEL contacts multiple co-repressors and specifically associates with histone deacetylase-3. Oncogene. 2001;20(28):3716-3725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mavrothalassitis G, Ghysdael J. Proteins of the ETS family with transcriptional repressor activity. Oncogene. 2000;19(55):6524-6532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ford AM, Bennett CA, Price CM, Bruin MC, Van Wering ER, Greaves M. Fetal origins of the TEL-AML1 fusion gene in identical twins with leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(8):4584-4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Greaves MF, Maia AT, Wiemels JL, Ford AM. Leukemia in twins: lessons in natural history. Blood. 2003;102(7):2321-2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ma Y, Dobbins SE, Sherborne AL, et al. Developmental timing of mutations revealed by whole-genome sequencing of twins with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(18):7429-7433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wiemels JL, Ford AM, Van Wering ER, Postma A, Greaves M. Protracted and variable latency of acute lymphoblastic leukemia after TEL-AML1 gene fusion in utero. Blood. 1999;94(3):1057-1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Patel N, Goff LK, Clark T, et al. Expression profile of wild-type ETV6 in childhood acute leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2003;122(1):94-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Romana SP, Le Coniat M, Poirel H, Marynen P, Bernard O, Berger R. Deletion of the short arm of chromosome 12 is a secondary event in acute lymphoblastic leukemia with t(12;21). Leukemia. 1996;10(1):167-170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Maia AT, Ford AM, Jalali GR, et al. Molecular tracking of leukemogenesis in a triplet pregnancy. Blood. 2001;98(2):478-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ford AM, Fasching K, Panzer-Grümayer ER, Koenig M, Haas OA, Greaves MF. Origins of “late” relapse in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia with TEL-AML1 fusion genes. Blood. 2001;98(3):558-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Stams WA, Beverloo HB, den Boer ML, et al. Incidence of additional genetic changes in the TEL and AML1 genes in DCOG and COALL-treated t(12;21)-positive pediatric ALL, and their relation with drug sensitivity and clinical outcome. Leukemia. 2006;20(3):410-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mullighan CG, Goorha S, Radtke I, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic alterations in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2007;446(7137):758-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lilljebjörn H, Soneson C, Andersson A, et al. The correlation pattern of acquired copy number changes in 164 ETV6/RUNX1-positive childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemias. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(16):3150-3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Caligiuri MA, Strout MP, Gilliland DG. Molecular biology of acute myeloid leukemia. Semin Oncol. 1997;24(1):32-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nucifora G. The EVI1 gene in myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 1997;11(12):2022-2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lugthart S, van Drunen E, van Norden Y, et al. High EVI1 levels predict adverse outcome in acute myeloid leukemia: prevalence of EVI1 overexpression and chromosome 3q26 abnormalities underestimated. Blood. 2008;111(8):4329-4337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Imai Y, Kurokawa M, Izutsu K, et al. Mutations of the AML1 gene in myelodysplastic syndrome and their functional implications in leukemogenesis. Blood. 2000;96(9):3154-3160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Harada H, Harada Y, Tanaka H, Kimura A, Inaba T. Implications of somatic mutations in the AML1 gene in radiation-associated and therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2003;101(2):673-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Christiansen DH, Andersen MK, Pedersen-Bjergaard J. Mutations of AML1 are common in therapy-related myelodysplasia following therapy with alkylating agents and are significantly associated with deletion or loss of chromosome arm 7q and with subsequent leukemic transformation. Blood. 2004;104(5):1474-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Harada H, Harada Y, Niimi H, Kyo T, Kimura A, Inaba T. High incidence of somatic mutations in the AML1/RUNX1 gene in myelodysplastic syndrome and low blast percentage myeloid leukemia with myelodysplasia. Blood. 2004;103(6):2316-2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Steensma DP, Gibbons RJ, Mesa RA, Tefferi A, Higgs DR. Somatic point mutations in RUNX1/CBFA2/AML1 are common in high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome, but not in myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. Eur J Haematol. 2005;74(1):47-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Niimi H, Harada H, Harada Y, et al. Hyperactivation of the RAS signaling pathway in myelodysplastic syndrome with AML1/RUNX1 point mutations. Leukemia. 2006;20(4):635-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chen CY, Lin LI, Tang JL, et al. RUNX1 gene mutation in primary myelodysplastic syndrome—the mutation can be detected early at diagnosis or acquired during disease progression and is associated with poor outcome. Br J Haematol. 2007;139(3):405-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Migas A, Savva N, Mishkova O, Aleinikova OV. AML1/RUNX1 gene point mutations in childhood myeloid malignancies. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(4):583-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ismael O, Shimada A, Hama A, et al. De novo childhood myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative disease with unique molecular characteristics. Br J Haematol. 2012;158(1):129-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tsai SC, Shih LY, Liang ST, et al. Biological activities of RUNX1 mutants predict secondary acute leukemia transformation from chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(15):3541-3551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Quentin S, Cuccuini W, Ceccaldi R, et al. Myelodysplasia and leukemia of Fanconi anemia are associated with a specific pattern of genomic abnormalities that includes cryptic RUNX1/AML1 lesions. Blood. 2011;117(15):e161-e170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Skokowa J, Steinemann D, Katsman-Kuipers JE, et al. Cooperativity of RUNX1 and CSF3R mutations in severe congenital neutropenia: a unique pathway in myeloid leukemogenesis. Blood. 2014;123(14):2229-2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Haferlach T, Nagata Y, Grossmann V, et al. Landscape of genetic lesions in 944 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2014;28(2):241-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Dicker F, Haferlach C, Sundermann J, et al. Mutation analysis for RUNX1, MLL-PTD, FLT3-ITD, NPM1 and NRAS in 269 patients with MDS or secondary AML. Leukemia. 2010;24(8):1528-1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Preudhomme C, Warot-Loze D, Roumier C, et al. High incidence of biallelic point mutations in the Runt domain of the AML1/PEBP2 alpha B gene in Mo acute myeloid leukemia and in myeloid malignancies with acquired trisomy 21. Blood. 2000;96(8):2862-2869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Roumier C, Eclache V, Imbert M, et al. ; Groupe Francais de Cytogenetique Hematologique (GFCH); Groupe Français d’Hématologie Cellulaire (GFHC). M0 AML, clinical and biologic features of the disease, including AML1 gene mutations: a report of 59 cases by the Groupe Français d’Hématologie Cellulaire (GFHC) and the Groupe Français de Cytogénétique Hématologique (GFCH). Blood. 2003;101(4):1277-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Tang JL, Hou HA, Chen CY, et al. AML1/RUNX1 mutations in 470 adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: prognostic implication and interaction with other gene alterations. Blood. 2009;114(26):5352-5361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Schnittger S, Dicker F, Kern W, et al. RUNX1 mutations are frequent in de novo AML with noncomplex karyotype and confer an unfavorable prognosis. Blood. 2011;117(8):2348-2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Al-Kzayer LF, Sakashita K, Al-Jadiry MF, et al. Frequent coexistence of RAS mutations in RUNX1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia in Arab Asian children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(11):1980-1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Greif PA, Konstandin NP, Metzeler KH, et al. RUNX1 mutations in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia are associated with a poor prognosis and up-regulation of lymphoid genes. Haematologica. 2012;97(12):1909-1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Mendler JH, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, et al. RUNX1 mutations are associated with poor outcome in younger and older patients with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia and with distinct gene and MicroRNA expression signatures. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(25):3109-3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Schuback HL, Arceci RJ, Meshinchi S. Somatic characterization of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia using next-generation sequencing. Semin Hematol. 2013;50(4):325-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Gaidzik VI, Bullinger L, Schlenk RF, et al. RUNX1 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: results from a comprehensive genetic and clinical analysis from the AML study group. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(10):1364-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Matsuno N, Osato M, Yamashita N, et al. Dual mutations in the AML1 and FLT3 genes are associated with leukemogenesis in acute myeloblastic leukemia of the M0 subtype. Leukemia. 2003;17(12):2492-2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kihara R, Nagata Y, Kiyoi H, et al. Comprehensive analysis of genetic alterations and their prognostic impacts in adult acute myeloid leukemia patients. Leukemia. 2014;28(8):1586-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ohgami RS, Ma L, Merker JD, et al. Next-generation sequencing of acute myeloid leukemia identifies the significance of TP53, U2AF1, ASXL1, and TET2 mutations. Mod Pathol. 2015;28(5):706-714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Grossmann V, Kern W, Harbich S, et al. Prognostic relevance of RUNX1 mutations in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2011;96(12):1874-1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Della Gatta G, Palomero T, Perez-Garcia A, et al. Reverse engineering of TLX oncogenic transcriptional networks identifies RUNX1 as tumor suppressor in T-ALL. Nat Med. 2012;18(3):436-440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Zhang J, Ding L, Holmfeldt L, et al. The genetic basis of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2012;481(7380):157-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Weiss HJ, Chervenick PA, Zalusky R, Factor A. A familial defect in platelet function associated with impaired release of adenosine diphosphate. N Engl J Med. 1969;281(23):1264-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Luddy RE, Champion LA, Schwartz AD. A fatal myeloproliferative syndrome in a family with thrombocytopenia and platelet dysfunction. Cancer. 1978;41(5):1959-1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Dowton SB, Beardsley D, Jamison D, Blattner S, Li FP. Studies of a familial platelet disorder. Blood. 1985;65(3):557-563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ho CY, Otterud B, Legare RD, et al. Linkage of a familial platelet disorder with a propensity to develop myeloid malignancies to human chromosome 21q22.1-22.2. Blood. 1996;87(12):5218-5224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Arepally G, Rebbeck TR, Song W, Gilliland G, Maris JM, Poncz M. Evidence for genetic homogeneity in a familial platelet disorder with predisposition to acute myelogenous leukemia (FPD/AML). Blood. 1998;92(7):2600-2602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Minelli A, Maserati E, Rossi G, et al. Familial platelet disorder with propensity to acute myelogenous leukemia: genetic heterogeneity and progression to leukemia via acquisition of clonal chromosome anomalies. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2004;40(3):165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Stockley J, Morgan NV, Bem D, et al. ; UK Genotyping and Phenotyping of Platelets Study Group. Enrichment of FLI1 and RUNX1 mutations in families with excessive bleeding and platelet dense granule secretion defects. Blood. 2013;122(25):4090-4093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Ouchi-Uchiyama M, Sasahara Y, Kikuchi A, et al. Analyses of genetic and clinical parameters for screening patients with inherited thrombocytopenia with small or normal-sized platelets. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(12):2082-2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Schmit JM, Turner DJ, Hromas RA, et al. Two novel RUNX1 mutations in a patient with congenital thrombocytopenia that evolved into a high grade myelodysplastic syndrome. Leuk Res Rep. 2015;4(1):24-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Buijs A, Poot M, van der Crabben S, et al. Elucidation of a novel pathogenomic mechanism using genome-wide long mate-pair sequencing of a congenital t(16;21) in a series of three RUNX1-mutated FPD/AML pedigrees. Leukemia. 2012;26(9):2151-2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Michaud J, Wu F, Osato M, et al. In vitro analyses of known and novel RUNX1/AML1 mutations in dominant familial platelet disorder with predisposition to acute myelogenous leukemia: implications for mechanisms of pathogenesis. Blood. 2002;99(4):1364-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Churpek JE, Garcia JS, Madzo J, Jackson SA, Onel K, Godley LA. Identification and molecular characterization of a novel 3′ mutation in RUNX1 in a family with familial platelet disorder. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51(10):1931-1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Bluteau D, Gilles L, Hilpert M, et al. Down-regulation of the RUNX1-target gene NR4A3 contributes to hematopoiesis deregulation in familial platelet disorder/acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2011;118(24):6310-6320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Owen CJ, Toze CL, Koochin A, et al. Five new pedigrees with inherited RUNX1 mutations causing familial platelet disorder with propensity to myeloid malignancy. Blood. 2008;112(12):4639-4645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.West AH, Godley LA, Churpek JE. Familial myelodysplastic syndrome/acute leukemia syndromes: a review and utility for translational investigations. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1310:111-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Nishimoto N, Imai Y, Ueda K, et al. T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia arising from familial platelet disorder. Int J Hematol. 2010;92(1):194-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Shiba N, Hasegawa D, Park MJ, et al. CBL mutation in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia secondary to familial platelet disorder with propensity to develop acute myeloid leukemia (FPD/AML). Blood. 2012;119(11):2612-2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Toya T, Yoshimi A, Morioka T, et al. Development of hairy cell leukemia in familial platelet disorder with predisposition to acute myeloid leukemia. Platelets. 2014;25(4):300-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Okuda T, van Deursen J, Hiebert SW, Grosveld G, Downing JR. AML1, the target of multiple chromosomal translocations in human leukemia, is essential for normal fetal liver hematopoiesis. Cell. 1996;84(2):321-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Sood R, English MA, Belele CL, et al. Development of multilineage adult hematopoiesis in the zebrafish with a runx1 truncation mutation. Blood. 2010;115(14):2806-2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Connelly JP, Kwon EM, Gao Y, et al. Targeted correction of RUNX1 mutation in FPD patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells rescues megakaryopoietic defects. Blood. 2014;124(12):1926-1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Sakurai M, Kunimoto H, Watanabe N, et al. Impaired hematopoietic differentiation of RUNX1-mutated induced pluripotent stem cells derived from FPD/AML patients. Leukemia. 2014;28(12):2344-2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Antony-Debré I, Manchev VT, Balayn N, et al. Level of RUNX1 activity is critical for leukemic predisposition but not for thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2015;125(6):930-940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]