Abstract

Background

Some carcinogenic viruses are known to be transmissible by blood transfusion. Intensive viral screening of transfused blood now exists in most countries. In the UK, high-sensitivity nucleic acid amplification tests for hepatitis C virus were introduced in 1999 and it was thought that this would reduce, and possibly eliminate, transfusion-related liver cancer. We aimed to investigate cancer risk in recipients of blood transfusion in 2000 or after.

Methods

A total of 1.3 million UK women recruited in 1998 on average were followed for hospital records of blood transfusion and for cancer registrations. After excluding women with cancer or precancerous conditions before or at the time of transfusion, Cox regression yielded adjusted relative risks of 11 site-specific cancers for women with compared to without prior blood transfusion.

Results

During follow up, 11 274 (0.9%) women had a first recorded transfusion in 2000 or after, and 1648 (14.6%) of them were subsequently diagnosed with cancer, a mean 6.8 years after the transfusion. In the first 5 years after transfusion there were significant excesses for most site-specific cancers examined, presumably because some had preclinical cancer. However, 5 or more years (mean 8 years) after blood transfusion, there were significant excess risks only for liver cancer (adjusted relative risk = 2.63, 95%CI 1.45–4.78) and for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (adjusted relative risk = 1.74, 1.21–2.51). When analyses were restricted to those undergoing hip or knee replacement surgery, the commonest procedure associated with transfusion, these relative risks were not materially altered.

Conclusions

In a large cohort of UK women, transfusions in the 21st century were associated with long-term increased risks of liver cancer and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Some of these malignancies may have been caused by carcinogenic agents that are not currently screened for in transfused blood.

Keywords: blood transfusion, cancer, lymphoma, liver cancer, blood-borne viruses

Introduction

Some carcinogenic infectious agents are known to be transmissible by blood transfusion. Although screening for hepatitis B and C viruses, human immunodeficiency viruses (HIVs), and human T-cell lymphotrophic viruses (HTLVs) in blood products was introduced in most developed countries during the 1980s and 1990s, transmission of carcinogenic viruses might still have been happening then [1, 2]. To reduce further the risk of virus transmission, nucleic acid amplification testing for Hepatitis C virus was introduced in the late 1990s as a highly sensitive blood screening tool in many countries, including the UK in 1999 [1]. There are no population-based data on cancer risks associated with transfusions in the 21st century, i.e. after the introduction of the nucleic acid amplification test for hepatitis C viruses in the donated blood. Our aim here is to examine on cancer incidence associated with blood transfusions administered in 2000 or later in a large cohort of UK women, among whom we could exclude those with cancer or precancerous conditions (e.g. hepatitis) at the time of or before the transfusion, and among whom we could adjust for known risk factors for cancer, including smoking and alcohol consumption. We investigated transfusion-associated site-specific cancer risks for the 10 most common cancer sites in the cohort, and also for liver cancer, as increased risks of liver cancer before the 21st century blood transfusion have been consistently reported [1, 2].

Methods

The Million Women Study, as described previously [3], is a cohort of 1.3 million UK women recruited at median age 56 years (interquartile range 52–60 years) through the UK National Breast Screening Programme in 1998 on average. At recruitment, participants provided informed consent and completed questionnaires reporting on socio-demographic and behavioural factors, and about their health. Individual data on hospital admissions and incident cancers in participants was obtained by record linkage to National Health Service (NHS) hospital admission, cancer registry, and death data. Conditions were coded using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) and interventions and procedures, including blood transfusions, were coded using the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys Classification of Interventions and Procedures version 4 (OPCS-4; http://www.hscic.gov.uk/). We used OPCS-4 codes X30-34 to define blood transfusion. The study was approved by the Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee for Anglia and Oxford.

Statistical analysis

Follow-up began on 1 January 2000 and the last date of follow-up was 31 December 2013, date of any cancer registration, date of death, or loss to follow up (whichever was earliest). We investigated 11 cancer sites, 10 of which were the most common, having 35 or more cases after blood transfusion, and also liver cancer, as there is strong prior evidence of its association with transfusion [1, 2]. ICD-10 codes used to define each of the 11 cancer sites are given in Supplementary Table S1 in the Appendix, available at Annals of Oncology online. Information on hospital admissions, including day cases and overnight stays, was available up to 31 March 2011 (England) or to 31 December 2008 (Scotland). In the UK, transfusions are given as a day-case admission or during an inpatient stay.

Cox regression was used to estimate relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for incident cancer by time since the first recorded blood transfusion (0–4 and 5 or more years after first transfusion) as a time-varying variable, compared with person-years without a prior blood transfusion. We estimated cancer risk by two time periods since transfusion because bleeding and/or chronic anaemia could be a symptom of preclinical cancer, and so the risk of cancer is expected to be high in the first few years after blood transfusion. It seems unlikely, however, that any preclinical cancer causing symptoms that would necessitate a blood transfusion would remain undiagnosed for 5 years or longer.

In the analyses of liver cancer risk, we excluded blood transfusion recipients who had prior or concurrent viral hepatitis, chronic hepatitis, or gastroesophageal varices (ICD-10 codes B1, I85, I86.4, I98.2, K73, and K74). In the analyses of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myeloma, and leukaemia, we excluded blood transfusion recipients who had prior or concurrent polycythaemia vera, myelodysplastic syndromes, neoplasm of uncertain behaviour of haematological malignancies or unspecific sites, or aplastic anaemia (ICD-10 codes: D45-48 and D60-61). In analyses for endometrial cancer, we excluded women who reported at recruitment that they had a history of hysterectomy. In analyses for ovarian cancer, we excluded women who reported at recruitment that they had a history of bilateral oophorectomy.

In all analyses, age was used as the underlying time variable, and hazard ratios (referred to as relative risks hereafter) were further stratified by year of birth (before 1940, 1940–1945, 1946, and after), region (Scotland and nine regions in England), and socioeconomic status (Townsend social deprivation [4], in quintiles), and adjusted for adult height (<155, 155–159, 160–164, 165–169, 170–174, and 175+ cm), smoking status (never, former, current <15, 15–24, 25+ cigarettes/day), body mass index (<22.5, 22.5–24.9, 25.0–27.4, 27.5–29.9, 30.0–32.4, 32.5–34.9, 35.0–37.4, and 37.5+ kg/m2, calculated from reported height and weight), and alcohol consumption (0, 1–4, 5–14, and 15+ g/day) [5]. Missing values (<6%) were treated as a separate category. We present standard p values and 95% confidence intervals, but only considered the P values statistically significant after correction for multiple comparisons using the Holm–Bonferroni method [6] at P < 0.05. To compare cancer risk before and after full adjustment, we calculated the percentage attenuation of the minimally adjusted RR after fully adjustment additionally for adult height, smoking status, body mass index, and alcohol consumption, i.e. (minimally adjusted RR−fully adjusted RR)/(minimally adjusted RR−1).

We also estimated the excess absolute cancer risks per 1000 women in the 5–9 years after transfusion. These were estimated by logistic models using STATA 14.2 (xtgee and margins), adjusted for age (in 5 year spans) and the same above-mentioned covariates including year of birth, region, socioeconomic status, adult height, smoking status, body mass index, and alcohol consumption.

Results

Among 1 299 246 women without prior cancer followed for 16.5 million person-years after 1 January 2000 (12.7 years per women on average), 11 274 (0.9%) women had one or more blood transfusions with the first one recorded in 2000 or later. In 2000–2013, 160 041 cancers occurred in the entire cohort, of which 1648 were in the 11 274 women who had had a blood transfusion in 2000 or later. The characteristics of women with and without a record of blood transfusion in 2000 or later are shown in Table 1. Compared with women without a record of blood transfusion, women with a record of blood transfusion were older at baseline, more likely to come from the most deprived tertile of the population, to be a current smoker, to have greater body mass index, and to drink less alcohol.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women with and without a record of blood transfusion, censored at any cancer diagnosis

| Women without a record of blood transfusion | Women with a record of blood transfusion | |

|---|---|---|

| n=1 287 972 | n=11 274 | |

| Age at start of follow up in years (mean, SD) | 58 (5) | 60 (5) |

| Information taken at recruitment | ||

| Lowest quintile of socioeconomic status (%) | 20 | 25 |

| Have ever smoked (%) | 49 | 54 |

| Body mass index in kg/m2 (mean, SD) | 26 (5) | 27 (6) |

| Alcohol consumption in g/day (mean, SD) | 7 (9) | 6 (9) |

| Number of cancer cases (ICD-10 code)a | ||

| Colorectal cancer (C18-20) | 17 547 | 291 |

| Liver cancer (C22) | 1227 | 25 |

| Pancreatic cancer (C25) | 4135 | 54 |

| Lung cancer (C34) | 16 587 | 197 |

| Breast cancer (C50) | 55 284 | 265 |

| Endometrial cancer (C54) | 9977 | 40 |

| Ovarian cancer (C56) | 7887 | 55 |

| Renal cancer (C64) | 3234 | 48 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (C82-85) | 6099 | 114 |

| Myeloma (C90) | 2424 | 38 |

| Leukaemia (C91–93, 95) | 2762 | 70 |

| Other cancers | 31230 | 451 |

ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, Revision 10.

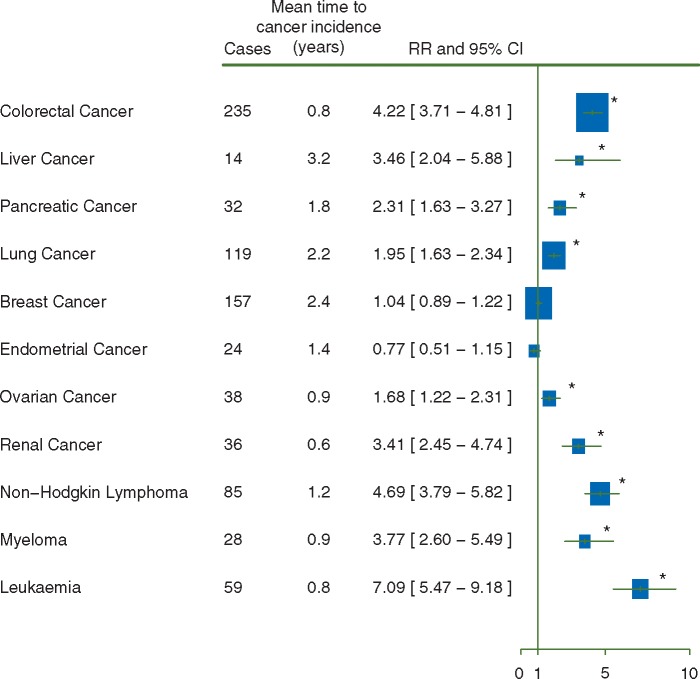

Fully adjusted relative risks for the 10 most common cancers and liver cancer in the first 5 years after transfusion, i.e. after adjustment for age, year of birth, region, socioeconomic status, adult height, body mass index, smoking, and alcohol consumption, are shown in Figure 1. Results for minimally adjusted RRs and RRs with additional adjustment for each factor can be found in the Supplementary Appendix, available at Annals of Oncology online. Relative risks of most cancers were relatively insensitive to additional adjustment (change of relative risk <15% after adjustment), but the relative risk of lung cancer was sensitive to adjustment for smoking status (25% change after adjustment), and the relative risk of endometrial cancer was sensitive to adjustment for body mass index (35% change after adjustment).

Figure 1.

Risk of cancer in the first 5 years after the 21st century blood transfusion. (♣) Risks were adjusted for age, year of birth, region, socioeconomic status, height, body mass index, smoking, and alcohol consumption. *P<0.05 after correction for multiple comparisons.

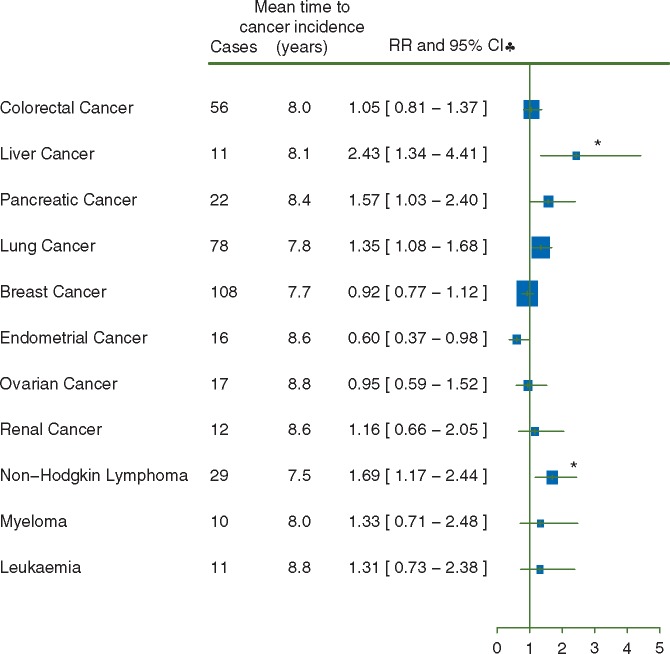

For 9 out of 11 cancer sites RRs were increased in the first 5 years after blood transfusion (Figure 1, P < 0.05 after correction for multiple comparisons), as expected, because some of the transfusions could well have been for precancerous conditions. Risks were much lower in the period 5 or more years after transfusion than in the period less than 5 years after transfusion (Figure 2; mean time of cancer incidence since transfusion = 8.0 years). The only RRs that remained significantly elevated 5 or more years after transfusion, after allowing for multiple comparisons, were those for liver cancer (RR = 2.43, 95%CI 1.34–4.41, P = 0.04) and for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (RR = 1.69, 95%CI 1.14–2.44, P = 0.05). Transfusion-associated RRs for liver cancer and non-Hodgkin lymphoma were slightly attenuated by adjustment for smoking, alcohol consumption, and body mass index (risk attenuation 13% for liver cancer and 7% for non-Hodgkin lymphoma). Sensitivity analysis excluding women with missing values for any of the adjustment variables yielded similar results for liver cancer (RR = 2.48, 95%CI 1.33–4.65) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (RR = 1.79, 95%CI 1.23–2.60).

Figure 2.

Risk of cancer 5 or more years after the 21st century blood transfusion. (♣) Risks were adjusted for age, year of birth, region, socioeconomic status, height, body mass index, smoking, and alcohol consumption. *P<0.05 after correction for multiple comparisons.

Table 2 shows the conditions and procedures recorded at the time of transfusion in the 11 women who developed liver cancer and the 29 women who had non-Hodgkin lymphoma 5 or more years after blood transfusion. Of the 11 women who developed liver cancer, about half (55%, 6/11) had had surgery at the time of transfusion (of which half, 3, were for hip or knee replacements) and 3 had investigations for non-cancer related, non-variceal gastrointestinal bleeding. None had a condition associated with liver disease or with liver cancer (having excluded all women with prior viral hepatitis, chronic hepatitis, or gastroesophageal varices in the analyses). Relative risk for 5 or more years after transfusion was similar when we restricted analysis to transfusion during hospital admissions for hip or knee replacement (three liver cancers, RR = 2.10, 95%CI 0.68–6.55), although the confidence interval was wide.

Table 2.

Procedures and conditions recorded at the time of transfusion in women who developed liver cancer or non-Hodgkin lymphoma 5 or more years after blood transfusion

| Conditions and procedures recorded at the time of transfusion |

|---|

| Liver cancer (11 in total) occurring 5 or more years after blood transfusion: |

| 6 had a transfusion associated with a surgical procedure, including 3 with knee or hip replacement surgery |

| 3 had a transfusion associated with investigations for gastrointestinal bleeding (not varices nor cancer) |

| 2 had transfusion for other conditions, none associated with liver disease or cancer |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (29 in total) occurring 5 or more years after blood transfusion: |

| 16 had a transfusion associated with a surgical procedure, including 12 with knee or hip replacement surgery |

| 9 had a transfusion associated with investigations for gastrointestinal bleeding (not varices nor cancer) |

| 4 had transfusion for other conditions, none associated with non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

Of the 29 women who developed non-Hodgkin lymphoma 5 or more years after transfusion, about half (55%, 16/29) had surgery at the time of transfusion (of which three quarters, 12, were for hip or knee replacements) and 9 had investigations for non-cancer related, non-variceal gastrointestinal bleeding. The remaining four women had a variety of conditions not associated with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. All women with prior polycythaemia vera, myelodysplastic syndromes, neoplasm of uncertain behaviour of haematological malignancies or unspecific sites, and aplastic anaemia were excluded from the analyses. Because non-Hodgkin lymphoma is weakly associated with a wide range of haematological conditions and other chronic conditions [7, 8], we further excluded women with a range of chronic conditions including rheumatologic diseases, other anaemias, viral hepatitis, and renal failure at baseline, and there was no substantial change in the relative risk after these further exclusions (RR for 5 or more years after transfusion 2.05, 95%CI 1.21–3.47, 14 cases). Risk was similar when analysis was restricted to transfusions associated with hip or knee replacements (12 non-Hodgkin lymphomas, RR = 2.14, 95%CI 1.21–3.77).

We estimated the absolute cancer incidence per 1000 person-years for liver cancer and non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the 5–9 years after blood transfusion, after adjustment. The absolute risk for liver cancer was 0.16 (95%CI 0.08–0.24) per 1000 person-years 5 or more years after blood transfusion, compared with 0.07 (95%CI 0.06–0.07) per 1000 person-years among women without a history of blood transfusion who had the same lifestyle profile. This is equivalent to about 1 excess liver cancer in every 2300 blood recipients 5–9 years after transfusion. For non-Hodgkin lymphoma, the absolute risks were 0.40 (95%CI 0.31–0.49) per 1000 person-years 5 or more years after blood transfusion compared to 0.28 (95%CI 0.27–0.29) per 1000 person-years among women without a history of blood transfusion, equivalent to about 1 excess non-Hodgkin lymphoma in every 1700 blood recipients 5–9 years after transfusion. For both cancers combined, there was about 1 excess cancer in every 1000 blood recipients in the 5–9 years after transfusion.

Discussion

In this report, we investigated risk of the 10 commonest cancers and of liver cancer in the 21st century blood transfusion recipients, an era after the introduction of nucleic acid amplification testing for hepatitis C virus, a more sensitive test than the previous antibody-based tests [1]. We found significant excesses both for liver cancer and for non-Hodgkin lymphoma 5 or more years (mean 8 years) after first known blood transfusion. The reasons the transfusions were done in these women appeared to be for conditions unlikely to be pre-clinical manifestations of either liver cancer or non-Hodgkin lymphoma; for example, a third of the transfusions were associated with hip or knee replacement surgery. In the analyses, we excluded women with known possible precancerous conditions at or before transfusion (as well as women without known cancer) and adjusted for potential confounding factors, such as smoking or alcohol consumption.

Cancers that are known to be caused by viruses are hepatocellular carcinoma (hepatitis viruses), some lymphomas (Epstein–Barr virus), nasopharyngeal carcinoma (Epstein–Barr virus), anogenital cancers and head and neck cancers (Human Papillomavirus), adult T-cell leukaemia (HTLV), and Kaposi sarcoma (Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus) [9]. Screening for hepatitis viruses, HTLV, and HIV in blood is a policy in UK and most developed countries. Since the introduction of nucleic acid amplification testing for hepatitis C virus in 1999 in the UK, it has been reported that only about 1 in a million blood transfusions carry the virus, and no known case of transfusion-related viral hepatitis soon after transfusion has been reported in the UK since 2005 [10]. However, cancers and other conditions long after transfusion have been less studied.

No other study has reported on cancer risk associated with the 21st century blood transfusion. A large study from Denmark and Sweden reported relative risks 5–9 years after blood transfusion in 1992–2002 of 1.86 for liver cancer and 1.20 for non-Hodgkin lymphoma [2]. The authors were not able to exclude people with prior precancerous conditions, and did not have information on life-style risk factors, and concluded that they could not exclude the possibility of confounding by these factors. The RRs found here for liver cancer and for non-Hodgkin lymphoma were significantly increased even after adjusting for known risk factors for cancer, including smoking, alcohol and body mass index and excluding women with possible precancerous conditions. Furthermore, the relative risks in this study did not change substantially in sensitivity analyses restricted to transfusions associated with hip or knee replacement surgery, where confounding by the indication for transfusion seems unlikely.

Given that confounding by known risk factors or indications for transfusion seem unlikely, the possibility that the excess risks of liver cancer and of non-Hodgkin lymphoma many years after the 21st century transfusions may be due to carcinogenic agents being transmitted in transfused blood needs to be considered. For liver cancer the extremely low carrier rate of hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses (<0.01%) reported among UK donors [11, 12] and the low false-negative rate in blood screening (<1%) has been estimated to correspond to a risk of less than 5 per million blood recipients under nucleic acid amplification tests [1]. However, we found about 1 excess liver cancer in every 2300 blood recipients in the 5–9 years after transfusion, much higher than the reported prevalence of the known hepatitis viruses. Breakthrough infections of screened viruses are unlikely to explain the excess of liver cancer, and the role of other viruses associated with liver cancer that were not screened for, such as Hepatitis G virus [13], needs to be investigated.

The excess risk of transfusion-associated non-Hodgkin lymphoma has been consistently reported previously [14–28]. Some have proposed the possibility of introduction of donor lymphoma cells through blood, although a large register-based study of cancer in the donors did not support this hypothesis [29]. Others have suggested that chemical or biological components of transfused blood may cause a temporary immunomodulation [30, 31], promoting lymphoma development, but this hypothesis would not explain why risks remain high many years after transfusion. Emerging evidence has suggested possible associations between viruses and some non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases, including Epstein–Barr virus [32] and again Hepatitis G virus [33, 34], and these viruses are not screened for in transfused blood.

Our findings are limited by the type of information on transfusion that was available. We did not have information on the type or the number of transfusions, nor on transfusions done before the hospital records began or on unrecorded transfusions. We could not investigate transfusion-associated cancer risks longer than 10 years after transfusion, because we restricted our study to the transfusions in the 21st century. Additionally, associations may be confounded by unmeasured factors, including conditions not recorded at the time of transfusion, or by transfusion history or other history prior to the period of data availability. Furthermore, we have no information for men or people transfused at younger ages.

Blood transfusions are generally given for life-threatening situations, and the immediate benefits would out-weight the long-term risk of cancer. Nevertheless, the long-term excess risks of liver cancer and of non-Hodgkin lymphoma warrants search for carcinogenic agents not currently screened for in transfused blood.

Key message

Screening for the blood-borne viruses in transfused blood has been extensive in the UK during the 21st century. In this large prospective study of UK women, we found increased risks of liver cancer and non-Hodgkin lymphoma more than 5 years after transfusion, suggesting that some of these malignancies may be caused by carcinogenic agents that are not currently screened for in transfused blood.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants in the Million Women Study. The Million Women Study Collaborators are listed in Appendix.

Funding

The Million Women Study is funded by Medical Research Council and Cancer Research UK (Cancer Research UK: C570/A16491, Medical Research Council: MR/K02700X/1).

Disclosure

All authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Soldan K, Davison K, Dow B.. Estimates of the frequency of HBV, HCV, and HIV infectious donations entering the blood supply in the United Kingdom, 1996 to 2003. Euro Surveill 2005; 10: 17–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hjalgrim H, Edgren G, Rostgaard K. et al. Cancer incidence in blood transfusion recipients. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007; 99: 1864–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Green J, Cairns BJ, Casabonne D. et al. Height and cancer incidence in the Million Women Study: prospective cohort, and meta-analysis of prospective studies of height and total cancer risk. Lancet Oncol 2011; 12: 785–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Townsend P, Phillimore P, Beattie A.. Health and Deprivation: Inequality and the North. London: Croon Helm; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Allen NE, Beral V, Casabonne D. et al. Moderate alcohol intake and cancer incidence in women. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009; 101: 296–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat 1979; 6: 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abe SK, Inoue M, Sawada N. et al. Hepatitis B and C virus infection and risk of lymphoid malignancies: a population-based cohort study (JPHC Study). Cancer Epidemiol 2015; 39: 562–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baecklund E, Iliadou A, Askling J. et al. Association of chronic inflammation, not its treatment, with increased lymphoma risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54: 692–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martin D, Gutkind JS.. Human tumor-associated viruses and new insights into the molecular mechanisms of cancer. Oncogene 2008; 27(Suppl 2): S31–S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NHS Choices. Risk of a blood transfusion. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/blood-transfusion/Pages/risks.aspx (3 July 2015, date last accessed).

- 11.Foundation for Liver Research. Hepatitis B: Out of the shadow. 2004; http://www.liver-research.org.uk/liver-research-files/Hepatitis-B---Out-of-the-Shadows.pdf (3 July 2015, date last accessed).

- 12.Public Health England. Hepatitis C in the UK: 2014 report. 2014; http://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/337115/HCV_in_the_UK_2014_24_July.pdf (3 July 2015, date last accessed).

- 13. Kew MC. Hepatitis viruses (other than hepatitis B and C viruses) as causes of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. J Viral Hepat 2013; 20: 149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Riedl R, Engels EA, Warren JL. et al. Blood transfusions and the subsequent risk of cancers in the United States elderly. Transfusion 2013; 53: 2198–2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang Y, Holford TR, Leaderer B. et al. Blood transfusion and risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in Connecticut women. Am J Epidemiol 2004; 160: 325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maguire-Boston EK, Suman V, Jacobsen SJ. et al. Blood transfusion and risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Am J Epidemiol 1999; 149: 1113–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cerhan JR, Engels EA, Cozen W. et al. Blood transfusion, anesthesia, surgery and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in a population-based case–control study. Int J Cancer 2008; 123: 888–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Adami J, Nyren O, Bergstrom R. et al. Blood transfusion and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: lack of association. Ann Intern Med 1997; 127: 365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cerhan JR. New epidemiologic leads in the etiology of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the elderly: the role of blood transfusion and diet. Biomed Pharmacother 1997; 51: 200–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brandt L, Brandt J, Olsson H. et al. Blood transfusion as a risk factor for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J Cancer 1996; 73: 1148–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Anderson H, Brandt L, Ericson A. et al. Blood transfusion at delivery and risk of subsequent malignant lymphoma in the mother. Vox Sang 1998; 75: 145–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blomberg J, Moller T, Olsson H. et al. Cancer morbidity in blood recipients—results of a cohort study. Eur J Cancer 1993; 29A: 2101–2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cerhan JR, Wallace RB, Folsom AR. et al. Transfusion history and cancer risk in older women. Ann Intern Med 1993; 119: 8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cerhan JR, Wallace RB, Dick F. et al. Blood transfusions and risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma subtypes and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2001; 10: 361–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chow EJ, Holly EA.. Blood transfusions as a risk factor for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in the San Francisco Bay Area: a population-based study. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 155: 725–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Inoue Y, Wada Y, Motohashi Y, Koizumi A.. History of blood transfusion before 1990 is associated with increased risk for cancer mortality independently of liver disease: a prospective long-term follow-up study. Environ Health Prev Med 2010; 15: 180–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Memon A, Doll R.. A search for unknown blood-borne oncogenic viruses. Int J Cancer 1994; 58: 366–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Skanberg J, Frisk B.. Blood transfusion does not influence the development of malignant tumours. Eur J Surg 1999; 165: 528–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Edgren G, Hjalgrim H, Reilly M. et al. Risk of cancer after blood transfusion from donors with subclinical cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2007; 369: 1724–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vamvakas EC, Blajchman MA.. Deleterious clinical effects of transfusion-associated immunomodulation: fact or fiction? Blood 2001; 97: 1180–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chow EJ, Holly EA.. Blood transfusions and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Epidemiol Rev 2002; 24: 269–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Teras LR, Rollison DE, Pawlita M. et al. Epstein–Barr virus and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the cancer prevention study-II and a meta-analysis of serologic studies. Int J Cancer 2015; 136: 108–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chang CM, Stapleton JT, Klinzman D. et al. GBV-C infection and risk of NHL among U.S. adults. Cancer Res 2014; 74: 5553–5560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Krajden M, Yu A, Braybrook H. et al. GBV-C/hepatitis G virus infection and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a case control study. Int J Cancer 2010; 126: 2885–2892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.