Abstract

Background

In LUX-Lung 7, the irreversible ErbB family blocker, afatinib, significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS), time-to-treatment failure (TTF) and objective response rate (ORR) versus gefitinib in patients with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Here, we present primary analysis of mature overall survival (OS) data.

Patients and methods

LUX-Lung 7 assessed afatinib 40 mg/day versus gefitinib 250 mg/day in treatment-naïve patients with stage IIIb/IV NSCLC and a common EGFR mutation (exon 19 deletion/L858R). Primary OS analysis was planned after ∼213 OS events and ≥32-month follow-up. OS was analysed by a Cox proportional hazards model, stratified by EGFR mutation type and baseline brain metastases.

Results

Two-hundred and twenty-six OS events had occurred at the data cut-off (8 April 2016). After a median follow-up of 42.6 months, median OS (afatinib versus gefitinib) was 27.9 versus 24.5 months [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.86, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.66‒1.12, P = 0.2580]. Prespecified subgroup analyses showed similar OS trends (afatinib versus gefitinib) in patients with exon 19 deletion (30.7 versus 26.4 months; HR, 0.83, 95% CI 0.58‒1.17, P = 0.2841) and L858R (25.0 versus 21.2 months; HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.62‒1.36, P = 0.6585) mutations. Most patients (afatinib, 72.6%; gefitinib, 76.8%) had at least one subsequent systemic anti-cancer treatment following discontinuation of afatinib/gefitinib; 20 (13.7%) and 23 (15.2%) patients received a third-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Updated PFS (independent review), TTF and ORR data were significantly improved with afatinib.

Conclusion

In LUX-Lung 7, there was no significant difference in OS with afatinib versus gefitinib. Updated PFS (independent review), TTF and ORR data were significantly improved with afatinib.

Clinicaltrials.gov identifier

Keywords: afatinib, gefitinib, NSCLC, overall survival

Introduction

Non-small-cell lung cancers (NSCLCs) with activating epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations are extremely sensitive to the EGFR-targeting tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) gefitinib, erlotinib and afatinib [1–8]. These three agents are established first-line treatment options in this setting; however, until recently, there was an absence of prospective randomised head-to-head comparisons to help guide treatment decisions.

To our knowledge, the recent randomised phase IIb LUX-Lung 7 trial was the first study to compare the irreversible ErbB family blocker, afatinib, with a reversible EGFR TKI, gefitinib, in treatment-naïve patients with advanced NSCLC harbouring a common EGFR mutation (exon 19 deletion/L858R) [9]. In this trial, afatinib significantly improved progression-free survival [PFS; hazard ratio (HR) 0.73, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.57‒0.95, P = 0.0165], time-to-treatment failure (TTF; HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.58‒0.92, P = 0.0073) and objective response rate (ORR; 70% versus 56%; odds ratio 1.873, 95% CI 1.176–2.985, P = 0.0083) compared with gefitinib. Overall, afatinib was well tolerated, with a predictable and manageable adverse event (AE) profile. Treatment-related AEs were experienced in 97.5% and 96.2% of patients in the afatinib and gefitinib arms, respectively. The most frequent grade ≥3 treatment-related AEs were diarrhoea (12.5%), rash/acne (9.4%) and fatigue (5.6%) with afatinib and elevated liver enzymes (8.8%), rash/acne (3.1%) and interstitial lung disease (ILD) (1.9%) with gefitinib. There was one drug-related fatal AE; a case of hepatic and renal failure with gefitinib treatment. There was no difference in the drug discontinuation rate due to treatment-related AEs between afatinib and gefitinib.

Along with PFS and TTF, overall survival (OS) was a co-primary endpoint of LUX-Lung 7; however, OS data were immature at the time of the primary analysis. Here, we report the mature OS results, including prespecified subgroup analysis and post-hoc analysis of the impact of post-study treatment on OS.

Methods

Study design and treatment

Full details on the trial design of LUX-Lung 7 have been published [9]. LUX-Lung 7 was a multicentre, international, randomised, open-label phase IIb trial (64 sites; 13 countries). Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years with treatment-naïve pathologically confirmed stage IIIB/IV adenocarcinoma and a documented common activating EGFR mutation (exon 19 deletion/L858R). Patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of 0 or 1, at least one measurable lesion [Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1] and adequate organ function. Patients were randomised 1:1 to once-daily oral afatinib 40 mg or gefitinib 250 mg and were treated until disease progression, intolerable AEs or other reasons necessitating withdrawal. Treatment beyond radiological progression was allowed for patients deemed to be receiving continued clinical benefit by the treating physician.

The co-primary endpoints were PFS by independent central review, TTF (time from randomisation to the time of treatment discontinuation for any reason including disease progression, treatment toxicity, and death) and OS. ORR by independent central review was a secondary endpoint. AEs were assessed according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0 (NCI CTCAE 3.0). Post-study treatments were provided at the physician’s discretion and assessed retrospectively.

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines as defined by the International Conference on Harmonization. All patients provided written informed consent.

Statistical plan

Three analysis timepoints were planned. The primary PFS/TTF analysis was planned after 250 PFS events and was previously published [9]. The primary OS analysis (reported herein) was planned after approximately 213 OS events and a follow-up period of at least 32 months for patients still alive. The final analysis will be undertaken at study completion (when all patients have completed treatment, or 5 years since the last patient was entered, whichever occurs first).

All randomised patients were included in the primary assessment of OS, and updated analysis of PFS and TTF (intention-to-treat population). Safety analysis included all patients who received at least one dose of study drug. OS and PFS/TTF were analysed by a log-rank test stratified by EGFR mutation type and the presence of baseline brain metastases. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to calculate HRs and 95% CIs. Prespecified subgroups included EGFR mutation type (exon 19 deletion/L858R), baseline brain metastases (presence versus absence), ECOG PS (0 versus 1), sex, age (<65 versus ≥65 years), ethnic origin (Asian versus non-Asian) and smoking history. ORR and disease control rate (DCR) were compared with a logistic regression model. All statistical testing was two sided at the nominal 5% significance level, with no adjustment for multiplicity. Data were analysed with SAS version 9.4.

Results

Patients

A total of 319 patients were randomised and treated with afatinib (n = 160) or gefitinib (n = 159). Baseline characteristics have been published and were similar between treatment groups [9]. Two-hundred and twenty-six OS events had occurred at the data cut-off of 8 April 2016; 109 (68.1%) and 117 (73.6%) patients treated with afatinib and gefitinib, respectively, had died by this time. At the time of analysis, the median duration of treatment was 13.7 months (range: 0‒46.4) with afatinib and 11.5 months (range: 0.5‒48.7) with gefitinib. Forty (25.0%) and 21 (13.2%) patients were treated for >24 months with afatinib and gefitinib, respectively. At data cut-off, 14 (8.8%) and 8 (5.0%) patients remained on treatment with afatinib and gefitinib.

Following discontinuation of study treatment, the majority of patients received at least one systematic anti-cancer therapy (72.6% and 76.8% in the afatinib and gefitinib arms, respectively; Table 1). Many patients also received third-line (43.8% and 55.0%), fourth-line (24.0% and 31.1%) and fifth-line therapies (13.0% and 19.2%, respectively). Fewer patients in the afatinib arm received a subsequent EGFR TKI than in the gefitinib arm (45.9% versus 55.6%); this imbalance was observed in both the EGFR exon 19 deletion (51.8% versus 59.8%) and L858R (38.1% versus 50.0%) subgroups. Twenty (13.7%) and 23 (15.2%) patients who discontinued study treatment in the afatinib and gefitinib arms received a third-generation EGFR TKI.

Table 1.

Subsequent therapies in patients who discontinued study treatment, in the overall population and in EGFR mutation subgroups

| Treatment, n (%) | Overall population |

Exon 19 deletion |

L858R mutation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afatinib (n = 146) | Gefitinib (n = 151) | Afatinib (n = 83) | Gefitinib (n = 87) | Afatinib (n = 63) | Gefitinib (n = 64) | |

| None | 38 (26.0) | 28 (18.5) | 20 (24.1) | 14 (16.1) | 18 (28.6) | 14 (21.9) |

| Systemic anti-cancer therapy | 106 (72.6) | 116 (76.8) | 61 (73.5) | 69 (79.3) | 45 (71.4) | 47 (73.4) |

| Chemotherapya | 84 (57.5) | 91 (60.3) | 48 (57.8) | 55 (63.2) | 36 (57.1) | 36 (56.3) |

| Platinum based | 70 (47.9) | 71 (47.0) | 40 (48.2) | 44 (50.6) | 30 (47.6) | 27 (42.2) |

| EGFR TKI | 67 (45.9) | 84 (55.6) | 43 (51.8) | 52 (59.8) | 24 (38.1) | 32 (50.0) |

| EGFR TKI monotherapy | 63 (43.2) | 74 (49.0) | 39 (47.0) | 47 (54.0) | 24 (38.1) | 27 (42.2) |

| First-generation | ||||||

| Gefitinib | 22 (15.1) | 27 (17.9) | 11 (13.3) | 21 (24.1) | 11 (17.5) | 6 (9.4) |

| Erlotinib | 23 (15.8) | 30 (19.9) | 16 (19.3) | 21 (24.1) | 7 (11.1) | 9 (14.1) |

| Second-generation | ||||||

| Afatinib | 6 (4.1) | 12 (7.9) | 4 (4.8) | 8 (9.2) | 2 (3.2) | 4 (6.3) |

| Poziotinib | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.7) |

| Third-generation | ||||||

| Osimertinib | 15 (10.3) | 17 (11.3) | 9 (10.8) | 11 (12.6) | 6 (9.5) | 6 (9.4) |

| Olmutinib | 5 (3.4) | 5 (3.3) | 5 (6.0) | 3 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.1) |

| EGFR TKI-containing combinationb | 7 (4.8) | 15 (9.9) | 5 (6.0) | 8 (9.2) | 2 (3.2) | 7 (10.9) |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitor | 3 (2.1) | 4 (2.6) | 2 (2.4) | 4 (4.6) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Radiotherapy | 26 (17.8) | 34 (22.5) | 16 (19.3) | 15 (17.2) | 10 (15.9) | 19 (29.7) |

Chemotherapy or chemotherapy-based combination.

Including gefitinib (afatinib arm, n = 7; gefitinib arm, n = 11), erlotinib (n = 0; n = 5) and osimertinib (n = 0; n = 1).

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Overall survival

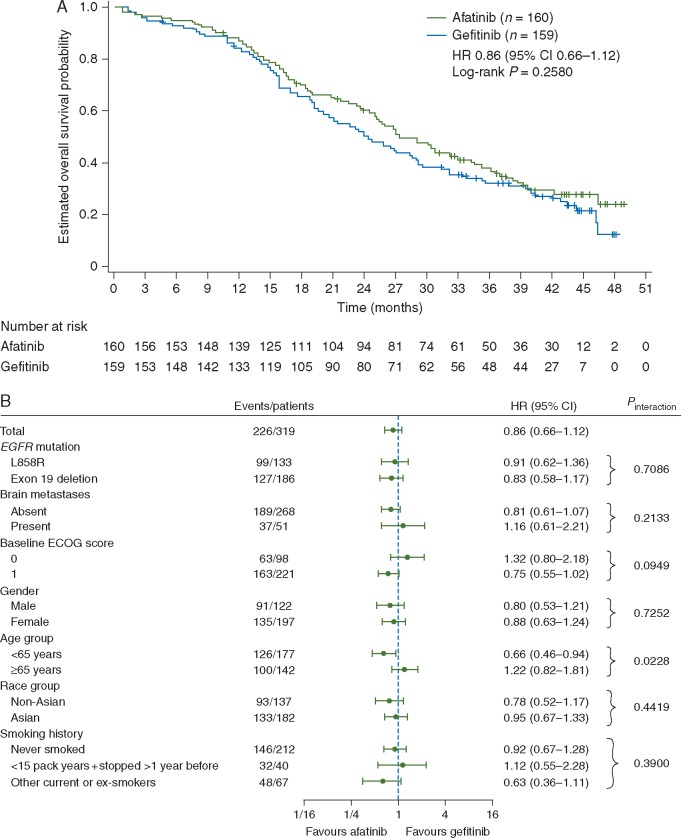

After a median follow-up of 42.6 months, median OS with afatinib versus gefitinib was 27.9 versus 24.5 months (HR, 0.86; 95% CI 0.66‒1.12; P = 0.2580; Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Overall survival. Kaplan–Meier curve (A) and forest plot of pre-specified subgroup analyses (B). CI, confidence interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HR, hazard ratio.

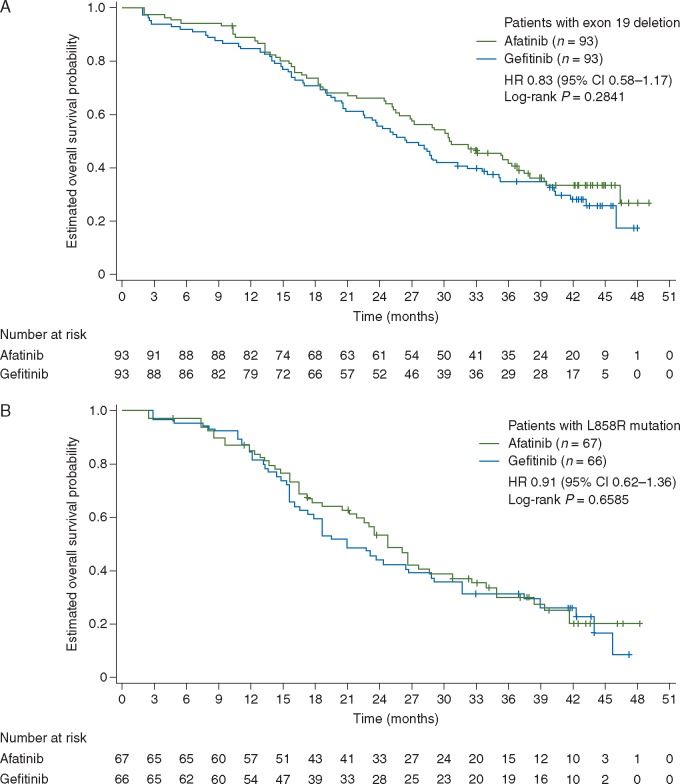

OS with afatinib versus gefitinib was similar across prespecified subgroups of interest (Figure 1B). There was no significant OS difference between afatinib and gefitinib in pre-planned subgroups that were used as stratification factors, i.e. baseline brain metastases (presence versus absence) and EGFR mutation type (exon 19 deletion versus L858R). Median OS with afatinib versus gefitinib in patients with exon 19 deletions (30.7 versus 26.4 months; HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.58‒1.17, P = 0.2841; Figure 2A) and patients with the L858R mutation (25.0 versus 21.2 months; HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.62‒1.36, P = 0.6585; Figure 2B) was generally consistent with the overall EGFR mutation-positive study population. There was no interaction between OS and patient subgroups, except for age based on the cut-offs of <65 and ≥65 years (Figure 1B). However, further post-hoc analysis demonstrated a consistent trend for OS benefit with afatinib independent of age group (no interaction observed at cut-offs of 60, 70 or 75 years). Similar median OS with afatinib was seen at cut-offs of 60, 65, 70 and 75 years (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Of note, subgroup sample sizes decreased with increasing age cut-off.

Figure 2.

Overall survival in patients with common EGFR mutations. Patients with exon 19 deletion (A) and patients with L858R mutation (B). CI, confidence interval; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HR, hazard ratio.

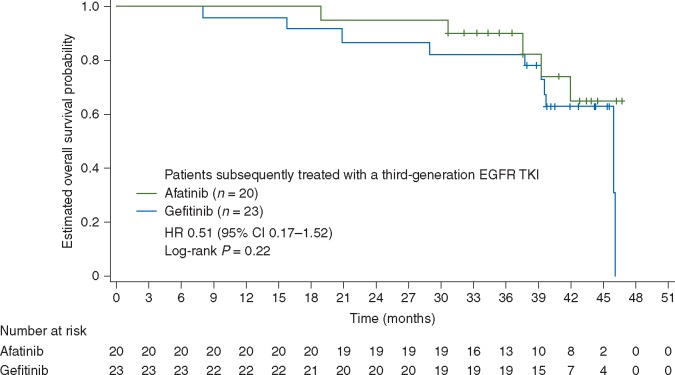

In a post-hoc analysis, median OS with afatinib versus gefitinib in patients who received a third-generation EGFR TKI following discontinuation of study treatment was ‘not evaluable’ versus 46.0 months (HR 0.51, 95% CI 0.17‒1.52, P = 0.22; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Overall survival in patients subsequently treated with a third-generation EGFR TKI following discontinuation of study treatment. CI, confidence interval; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HR, hazard ratio; TKIs, tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Other efficacy endpoints

Updated analysis of the co-primary endpoints showed similar findings to the primary analysis [9]. PFS by independent review (median 11.0 versus 10.9 months; HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.57‒0.95, P = 0.0178; supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online) and TTF (median 13.7 versus 11.5 months; HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.60‒0.94, P = 0.0136; supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online) were significantly improved with afatinib versus gefitinib.

Updated ORR was also significantly higher with afatinib than with gefitinib [72.5% versus 56.0%; odds ratio 2.121 (95% CI 1.32–3.40); P = 0.0018; supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online]. The DCR was 91.3% versus 87.4% (afatinib versus gefitinib; odds ratio 1.552, 95% CI 0.75–3.22, P = 0.2372).

Safety

The safety profiles of afatinib and gefitinib were virtually unchanged since the primary analysis [9]. The frequency of all-cause grade ≥3 AEs was 56.9% and 53.5%, and of treatment-related grade ≥3 AEs was 31.3% and 19.5%, with afatinib and gefitinib, respectively (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). The most frequent treatment-related grade ≥3 AEs with afatinib were diarrhoea (13.1% versus 1.3%), rash/acne (9.4% versus 3.1%) and fatigue (5.6% versus 0%). The most frequent treatment-related grade ≥3 AEs with gefitinib were elevated alanine transaminase (8.2% versus 0%), rash/acne, elevated aspartate aminotransferase (2.5% versus 0%) and interstitial lung disease (1.9% versus 0%; supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). There was one drug-related fatal AE; a case of hepatic and renal failure with gefitinib treatment. Rates of treatment discontinuations due to drug-related AEs remained equally low (6.3% each).

Discussion

In this updated analysis of LUX-Lung 7, a 14% reduction in risk of death was observed in patients with EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC treated with first-line afatinib versus gefitinib, that corresponded to a numerical difference of 3.4 months in median OS, without reaching statistical significance. These findings were generally consistent across key patient subgroups, including those based on gender, ethnicity (Asian versus non-Asian), and EGFR mutation type (exon 19 deletion versus L858R). Although initial analyses suggested a potential interaction between OS and patient age, subsequent post-hoc analysis demonstrated no clear pattern of association, and similar median OS with afatinib was observed for patients aged </≥60,</≥65, </≥70 and </≥75 years. Afatinib conferred long-term survival in a high proportion of patients, with 24-month and 30-month survival rates of 60.9% and 48.0%, respectively. These frequencies were consistent with a previous global, phase III trial, which assessed afatinib versus cisplatin/pemetrexed in patients with NSCLC harbouring common EGFR mutations (LUX-Lung 3). In this study, 59.6% and 49.8% of afatinib-treated patients survived for at least 24 and 30 months, respectively [10]. In the present study, as in the primary analysis, afatinib significantly improved PFS, TTF and ORR versus gefitinib. No unexpected AEs were observed and discontinuation rates due to treatment-related AEs remained equally low in both arms.

Despite being recognised as the first-line standard-of-care in patients with EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC, an enduring feature of randomised controlled trials of EGFR TKIs in this setting has been a lack of clear OS benefit, even against platinum-doublet chemotherapy. Across multiple phase III trials, neither erlotinib [4, 7, 11] nor gefitinib [12–14] has demonstrated statistically significant OS improvement against chemotherapy. Although afatinib did not significantly improve OS versus chemotherapy in the overall populations of the LUX-Lung 3 and LUX-Lung 6 trials, a significant improvement in OS was observed with afatinib in a prespecified sub-analysis of each trial, in patients with NSCLC harbouring exon 19 deletion mutations [10]. In the current study, there was no significant difference in OS between afatinib and gefitinib in patients with NSCLC harbouring an exon 19 deletion. Emerging evidence suggests that first-generation and second-generation EGFR TKIs may be particularly active in NSCLC with exon 19 deletions compared with the L858R mutation [15], but this is based on trials that used chemotherapy as a comparator rather than TKI versus TKI comparisons. Therefore, as any efficacy benefit with afatinib over gefitinib in LUX-Lung 7 would not necessarily be restricted to patients harbouring exon 19 deletions only, we claim that the choice of a TKI for an individual patient might not be based on EGFR mutational profile.

The rates of post-progression therapy observed in this trial were noticeably high. Around 75% of patients in both arms received at least one systemic anti-cancer therapy, and multiple lines of therapy were common (∼25% received at least four lines). This rate of post-progression therapy is somewhat higher than reported in most previous trials including EGFR mutation-positive patients treated with EGFR TKIs (66%‒68% in erlotinib trials [4, 7, 11], 64%‒90% in gefitinib trials [12, 14, 16] and 58%‒70% in afatinib trials [5, 6]. In LUX-Lung 7, there were slight imbalances in the number of patients who received a subsequent first- (30.8% and 37.7%) or second-generation (4.1% and 10.6%) EGFR TKI monotherapy in the afatinib and gefitinib arms, respectively, although the uptake of third-generation EGFR TKIs was similar (13.7% and 15.2%). Although there is a general paucity of prospective data assessing the effectiveness of sequencing of first- and second-generation EGFR TKIs, it is conceivable that these imbalances might have influenced OS. Previous studies, for example, indicate that afatinib therapy administered post-gefitinib/erlotinib [17, 18], or gefitinib rechallenge [19] offer modest efficacy benefits.

Furthermore, the limited sample size may have impaired the power of the trial to address the differences in OS benefit between afatinib and gefitinib in clinical practice.

The primary OS analysis described herein fulfilled the protocol requirement in terms of the planned number of events and minimum follow-up time. However, at the time of writing, 29% of patients in LUX-Lung 7 were still alive and a final OS analysis is planned on study completion to assess the impact of a reduction in censored patients. It should be noted that LUX-Lung 7 was not powered for OS. As an exploratory phase IIb trial, no formal hypothesis was defined and sample size was based on controlling the width of the CI for the HR of PFS [9]. Given the influence of non-NSCLC-related deaths and post-study treatments, OS requires larger sample sizes than PFS [20].

Given the recent development of third-generation EGFR TKIs such as osimertinib and olmutinib, which are highly effective against T790M mutation-positive tumours [21, 22], improved understanding of, and screening for, mechanisms of acquired resistance to first-line EGFR-targeted agents will allow for the most appropriate and effective sequence of treatments for EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC patients. It is known that 50%‒60% of patients treated with erlotinib or gefitinib develop T790M-positive tumours following disease progression [23, 24]. Recent data indicate a similar frequency of T790M-mediated resistance in patients treated with first-line afatinib [25]. Therefore, regardless of the choice of the first-line TKI in patients with EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC, similar numbers of patients are likely to benefit from a subsequent third-generation EGFR TKI. Although patient numbers are small, this assertion is supported by the current study. In both treatment arms, survival rates were striking in patients who received a subsequent third-generation EGFR TKI, with 3-year OS rates of up to 90%. These findings bode well for the strategy of sequential treatment with EGFR TKIs, which could potentially make EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC a chronic disease, at least in a subset of patients.

Other than the recent CTONG 0901 trial which compared gefitinib with erlotinib and found no difference in efficacy and safety [26], LUX-Lung 7 is the only published trial to compare the first-line EGFR-targeted TKIs in patients with EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC [although another head-to-head trial is currently comparing the second-generation TKI, dacomitinib, versus gefitinib (ARCHER-1050)]. In summary, although LUX-Lung 7 was an exploratory phase IIb trial, we believe that the size of the trial (with 319 randomised patients it was as large as many phase III trials in the same setting) and the totality of the data being largely positive across multiple clinically relevant, independently assessed endpoints, suggests that afatinib may be a more effective treatment option than gefitinib in the first-line setting. Treatment-related AEs with afatinib were predictable, did not negatively impact health-related quality of life, and were largely manageable with tolerability-guided dose reductions such that the treatment discontinuation rate was the same as with gefitinib. We hypothesise that the efficacy benefits with afatinib reflect a broader mechanism of action compared with gefitinib.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients, their families, the investigators and staff who participated in the study. The authors were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions, were involved at all stages of manuscript development and have approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim. Medical writing assistance, supported financially by Boehringer Ingelheim, was provided by Lynn Pritchard of GeoMed, an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare plc, during the preparation of this article. There is no applicable grant number.

Disclosure

LP-A has received honoraria from Roche, MSD, BMS, Novartis, Lilly, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Clovis and Bayer. KO’B has received honoraria for participating in advisory boards and/or speaker bureaus and has received travel grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Roche, Pfizer, Lilly Oncology, MSD, BMS and Novartis. LZ has participated in advisory boards for AstraZeneca and BMS and has conducted corporate-sponsored research for BMS, Pfizer and Lilly. He has also received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Roche and Lilly. VH has participated in advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Roche, Pfizer, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim, Amgen and Lilly. MB has participated in advisory boards for Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Pfizer, AstraZeneca and BMS, and has conducted corporate-sponsored research for Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, BMS, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Clovis, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim and Genentech. He is a member of the Board of Directors for IASLC. JC-HY has participated in advisory boards and received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Roche/Genentech/Chugai, Astellas, MSD, Merck Serono, Pfizer, Novartis, Clovis Oncology, Merrimack, BMS and Ono pharmaceutical. TM is employed by The Chinese University of Hong Kong and reports stock ownership/options in Sanomics Ltd. He has received honoraria and participated in advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Roche/Genentech, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck Serono, MSD, Janssen, Clovis Oncology, BioMarin, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, SFJ Pharmaceutical, ACEA Biosciences, Inc., Vertex Pharmaceuticals, BMS, Celgene, AVEO and Biodesix. He has also received honoraria from Prime Oncology and Amgen and participated in advisory boards for geneDecode Co., Ltd. He has conducted corporate-sponsored research for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Novartis, SFJ Pharmaceutical, Roche, MSD, Clovis Oncology and BMS. He is a member of the Board of Directors for IASLC, Chinese Lung Cancer Research Foundation Ltd, Chinese Society of Oncology and the Hong Kong Cancer Therapy Society. DHL has received honoraria from AstraZeneca Korea, BMS Korea, Boehringer Ingelheim Korea, MSD Korea, Mundi Korea, Ono Korea, Roche Korea and Samyang Biopharmaceuticals. JL has received honoraria for academic talks from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca and Roche. SAL has participated in an advisory board for Boehringer Ingelheim. JF, ND and AM are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim. KP has participated in an advisory board for Boehringer Ingelheim and has conducted corporate-sponsored research for AstraZeneca. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K. et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 2380–2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y. et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S. et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 947–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R. et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: 239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N. et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 3327–3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wu YL, Zhou C, Hu CP. et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin plus gemcitabine for first-line treatment of Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring EGFR mutations (LUX-Lung 6): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu YL, Zhou C, Liam CK. et al. First-line erlotinib versus gemcitabine/cisplatin in patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: analyses from the phase III, randomized, open-label, ENSURE study. Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 1883–1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G. et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2011; 12: 735–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Park K, Tan EH, O'Byrne K. et al. Afatinib versus gefitinib as first-line treatment of patients with EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (LUX-Lung 7): a phase 2B, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 577–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yang JC, Wu YL, Schuler M. et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin-based chemotherapy for EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinoma (LUX-Lung 3 and LUX-Lung 6): analysis of overall survival data from two randomised, phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 141–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G. et al. Final overall survival results from a randomised, Phase III study of erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment of EGFR mutation-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802). Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 1877–1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fukuoka M, Wu YL, Thongprasert S. et al. Biomarker analyses and final overall survival results from a phase III, randomized, open-label, first-line study of gefitinib versus carboplatin/paclitaxel in clinically selected patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in Asia (IPASS). J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 2866–2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Maemondo M. et al. Updated overall survival results from a randomized phase III trial comparing gefitinib with carboplatin-paclitaxel for chemo-naive non-small cell lung cancer with sensitive EGFR gene mutations (NEJ002). Ann Oncol 2013; 24: 54–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yoshioka H, Mitsudomi T, Morita S. et al. Final overall survival results of WJTOG 3405, a randomized phase 3 trial comparing gefitinib (G) with cisplatin plus docetaxel (CD) as the first-line treatment for patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). J Clin Oncol 2014; 32 (Suppl. 15): abstract 8117. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee CK, Wu YL, Ding PN. et al. Impact of Specific Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Mutations and Clinical Characteristics on Outcomes After Treatment With EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Versus Chemotherapy in EGFR-Mutant Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 1958–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Maemondo M. et al. Final overall survival results of NEJ002, a phase III trial comparing gefitinib to carboplatin (CBDCA) plus paclitaxel (TXL) as the first-line treatment for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29 (Suppl. 15): abstract 7519. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miller VA, Hirsh V, Cadranel J. et al. Afatinib versus placebo for patients with advanced, metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer after failure of erlotinib, gefitinib, or both, and one or two lines of chemotherapy (LUX-Lung 1): a phase 2b/3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: 528–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schuler M, Yang JC, Park K. et al. Afatinib beyond progression in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer following chemotherapy, erlotinib/gefitinib and afatinib: phase III randomized LUX-Lung 5 trial. Ann Oncol 2016; 27: 417–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cappuzzo F, Morabito A, Normanno N. et al. Efficacy and safety of rechallenge treatment with gefitinib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2016; 99: 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pilz LR, Manegold C, Schmid-Bindert G.. Statistical considerations and endpoints for clinical lung cancer studies: Can progression free survival (PFS) substitute overall survival (OS) as a valid endpoint in clinical trials for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer? Transl Lung Cancer Res 2012; 1: 26–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Janne PA, Yang JC, Kim DW. et al. AZD9291 in EGFR inhibitor-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1689–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Park K, Lee JS, Lee KH. et al. Updated safety and efficacy results from phase I/II study of HM61713 in patients (pts) with EGFR mutation positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who failed previous EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI). J Clin Oncol 2015; 33 (Suppl. 15): abstract 8084. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T. et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 786–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pao W, Miller VA, Politi KA. et al. Acquired resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib is associated with a second mutation in the EGFR kinase domain. PLoS Med 2005; 2: e73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wu SG, Liu YN, Tsai MF. et al. The mechanism of acquired resistance to irreversible EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor-afatinib in lung adenocarcinoma patients. Oncotarget 2016; 7: 12404–12413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yang J-J, Zhou Q, Yan H-H. et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Erlotinib versus Gefitinib in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harboring EGFR Mutations (CTONG0901). J Thorac Oncol 2015; 10 (Suppl 2): S321. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.