Abstract

Hypercholesterolemia is a well known risk factor for the development of neurodegenerative disease. However, the underlying mechanisms are mostly unknown. In recent years, it has become increasingly evident that cholesterol-driven effects on physiology and pathophysiology derive from its ability to alter the function of a variety of membrane proteins including ion channels. Yet, the effect of cholesterol on G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels expressed in the brain is unknown. GIRK channels mediate the actions of inhibitory brain neurotransmitters. As a result, loss of GIRK function can enhance neuron excitability, whereas gain of GIRK function can reduce neuronal activity. Here we show that in rats on a high-cholesterol diet, cholesterol levels in hippocampal neurons are increased. We also demonstrate that cholesterol plays a critical role in modulating neuronal GIRK currents. Specifically, cholesterol enrichment of rat hippocampal neurons resulted in enhanced channel activity. In accordance, elevated currents upon cholesterol enrichment were also observed in Xenopus oocytes expressing GIRK2 channels, the primary GIRK subunit expressed in the brain. Furthermore, using planar lipid bilayers, we show that although cholesterol did not affect the unitary conductance of GIRK2, it significantly enhanced the frequency of channel openings. Last, combining computational and functional approaches, we identified two putative cholesterol-binding sites in the transmembrane domain of GIRK2. These findings establish that cholesterol plays a critical role in modulating GIRK activity in the brain. Because up-regulation of GIRK function can reduce neuronal activity, our findings may lead to novel approaches for prevention and therapy of cholesterol-driven neurodegenerative disease.

Keywords: cholesterol, electrophysiology, lipid bilayer, lipid-protein interaction, molecular docking, neuron, structure-function, G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium channel, cholesterol-induced channel activation, hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons

Introduction

G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK)3 (or Kir3) channels mediate many of the actions of inhibitory neurotransmitters (1–9), translating chemical transmission to electrical signaling at post-synaptic sites, and thereby constituting the main mechanism for generating slow inhibitory post-synaptic potentials (10). Specifically, in response to neurotransmitter stimulation of G protein-coupled receptors such as the GABAB receptor, GIRK channels hyperpolarize neurons, thereby controlling their excitability (e.g. Refs. 3 and 11–15). As a result, an increase in GIRK currents may affect synaptic function early in development and reshape the electrical balance in the brain in mature animals (16).

Cholesterol, a critical component of the membranes in all mammalian cells necessary for cell viability, growth, and proliferation, has been shown to alter the function of multiple ion channels including atrial GIRK channels (17). An increase in cholesterol levels is associated not only with the development of cardiovascular disease (18–20) but also with the development of neurodegenerative disease (21–23). Yet, the effect of cholesterol on GIRK channels expressed in the brain is unknown. We thus focused on the role of cholesterol in the regulation of GIRK channels expressed in the brain.

The most common effect of cholesterol on ion channels is a decrease in channel activity (e.g. for reviews, see Refs. 24–26). Examples of channels that were shown to be suppressed by cholesterol include several inwardly rectifying potassium channels (27, 28) (e.g. Kir1.1, Kir2.x (x = 1–4), and the C-terminal truncation mutant that renders Kir6.2 active as homomers, Kir6.2Δ36 (29)) as well as Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels (30, 31), voltage-gated Na+ channels (32), N-type Ca2+ channels (33), and volume-sensitive Cl− channels (34). In contrast, very few types of channels were enhanced by cholesterol enrichment and/or suppressed by cholesterol depletion. Examples include the transient receptor potential canonical channel TRPC1 (35), Ca2+-permeable stretch-activated cation channels (36), and the epithelial Na+ channels (37, 38). Furthermore, within specific subfamilies of ion channels, the impact of cholesterol is generally uniform. For example, all members of the Kir2 subfamily of channels are suppressed by cholesterol (28). Thus, our earlier observations of increased GIRK currents in atrial myocytes from rats on a high-cholesterol diet were unexpected (17). In particular, atrial KACh channels that are heterotetramers of GIRK1 and GIRK4 (39) were up-regulated by cholesterol (17). Furthermore, unlike the majority of subfamilies of ion channels, the impact of cholesterol varied within the GIRK subfamily. Whereas the highly active pore mutant GIRK4* (GIRK4_S143T (40, 41)) was up-regulated by cholesterol (17, 27), GIRK1* (GIRK1_F137S (40)) was down-regulated by cholesterol enrichment (17). These findings suggested that GIRK4 played a dominant role in determining the impact of cholesterol on atrial KACh channels.

In the brain, however, expression of GIRK4 is low (42). Conversely, different combinations of GIRK1, GIRK2, and GIRK3 are abundant (10, 43–47, 49). For example, GIRK1, GIRK2a, GIRK2c, and GIRK3 are expressed in the hippocampus (3, 50–52). Thus, in view of the differential effect of cholesterol on GIRK subunits expressed in the heart, we investigated the effect of cholesterol on hippocampal GIRK currents. Our data demonstrate that in hippocampal neurons, GIRK currents are enhanced by cholesterol.

Among GIRK subunits expressed in hippocampal neurons, functional channels may be formed from GIRK2 subunits as homomers or as heteromers with GIRK1 and/or GIRK3, both of which do not express as homomers in the plasma membrane (3, 51–57). Given that GIRK1* was suppressed by cholesterol (17), and that the effect of cholesterol on homomeric GIRK3 channels cannot be determined, we investigated the effect of cholesterol on GIRK2 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Our data showed that similarly to the effect of cholesterol on hippocampal GIRK currents, GIRK2 currents in Xenopus oocytes were enhanced by cholesterol. Furthermore, to determine the effect of cholesterol on the open probability of the channel, we employed channel reconstitution into planar lipid bilayers. Last, using a combination of homology modeling, molecular docking, and site-directed mutagenesis, we identified two putative cholesterol-binding sites in GIRK2.

Results

Cholesterol levels in pyramidal neurons are increased in rats on high-cholesterol diet

We have previously shown that after 18–23 weeks on a high-cholesterol diet, rats exhibit a significant increase in total cholesterol and LDL (low density lipoprotein) (58). To determine the physiological relevance of an increase in blood serum cholesterol levels to neuronal channel activity, we determined the effect of an 18–23-week-long hypercholesterolemic diet on cholesterol levels in neurons. In particular, we focused on pyramidal neurons freshly isolated from the CA1 region of the hippocampus of rats that have been previously shown to express GIRK subunits (50–52).

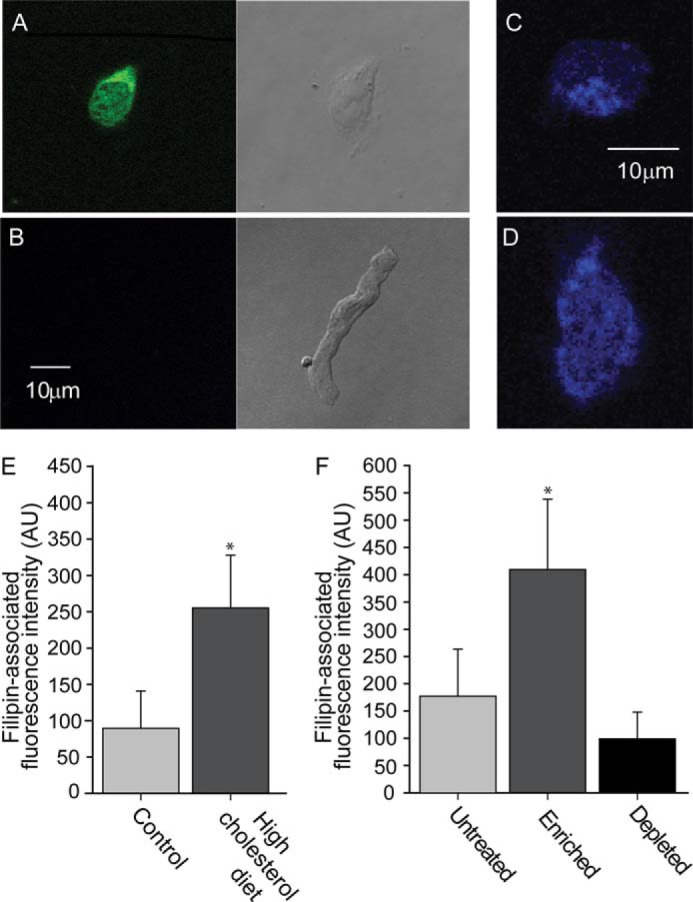

First, to distinguish freshly isolated pyramidal neurons from other cell types, we used neuron-specific enolase-associated immunofluorescent staining. As Fig. 1, A and B, demonstrates, an enolase-associated immunofluorescence signal was detected from pyramidal neurons, but not from cerebral artery myocytes, thereby allowing to specifically identify neuronal cells.

Figure 1.

Cholesterol levels in pyramidal neurons are increased in hypercholesterolemic rats. A and B, neuron-specific, enolase-associated immunofluorescence signal was detected from (A) pyramidal neurons from the CA1 hippocampal region, but not from (B) cerebral artery myocytes. C–E, filipin-associated fluorescence signal of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons from rats on control (C) versus (D) a high-cholesterol diet. E, summary data of filipin-associated fluorescence signals of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons from rats on control and on a high-cholesterol diet (n = 12–13). F, summary data of filipin-associated fluorescence signals obtained from control, cholesterol-depleted, and cholesterol-enriched isolated hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons (n = 12–14). Significant difference is indicated by an asterisk (*, p ≤ 0.05).

Next, we determined the cellular cholesterol content of freshly isolated pyramidal neurons using filipin staining. As shown in Fig. 1, C–E, the cholesterol level in neurons isolated from animals that have been on a high-cholesterol diet for 18–23 weeks was significantly higher than in neurons isolated from animals subjected to a control iso-caloric diet. These data demonstrate that along with an increase in blood serum cholesterol, cholesterol levels in hippocampal neurons are also increased following high-cholesterol dietary intake.

In vitro cholesterol enrichment of pyramidal neurons results in increased cholesterol levels in the neurons

Having demonstrated that a high cholesterol diet leads to increased cholesterol levels in hippocampal neurons, we next tested whether in vitro enrichment of cholesterol has a similar effect, and could thus serve as a model system to test the effect of cholesterol on hippocampal GIRK currents. To this end, we enriched hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons by exposing the neurons for 1 h to methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) saturated with cholesterol, a well known cholesterol donor (59). As demonstrated in Fig. 1F, this treatment resulted in an increase in cholesterol levels in hippocampal neurons that was comparable with the increase in cholesterol levels in the neurons observed following high-cholesterol dietary intake (Fig. 1D). Conversely, cholesterol depletion of hippocampal neurons by a 30-min exposure to cholesterol-free MβCD, which acts as a cholesterol acceptor (59), resulted in a decrease in cholesterol levels (Fig. 1F).

These data demonstrate that in vitro cholesterol enrichment of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons can serve as a model system that represents the effect of a high-cholesterol dietary intake on the levels of cholesterol in the neurons.

GIRK currents in hippocampal pyramidal neurons are up-regulated by cholesterol

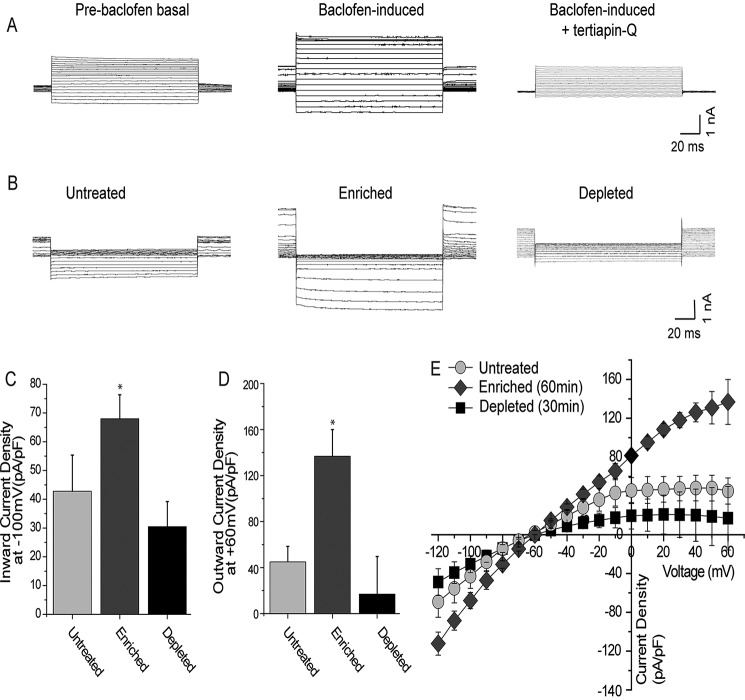

Next, to investigate the role of cholesterol in modulating hippocampal GIRK channels, we examined the effect of both cholesterol enrichment and depletion on baclofen-induced GIRK currents in freshly isolated neurons obtained from the CA1 region of the hippocampus of rats. As shown in Fig. 2, A–E, cholesterol enrichment by exposing hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons for 1 h to MβCD saturated with cholesterol resulted in an ∼2-fold increase in both inward and outward baclofen-induced GIRK currents that were sensitive to the selective GIRK channel-blocker tertiapin-Q (60). Conversely, cholesterol depletion following a 30-min exposure to cholesterol-free MβCD decreased hippocampal GIRK currents (Fig. 2, A–E). Similarly to the effect of cholesterol enrichment on both inward and outward GIRK currents, cholesterol depletion also had a substantial effect on both the larger inward currents and the physiologically relevant smaller outward currents.

Figure 2.

Cholesterol up-regulates neuronal GIRK channels in neurons from the CA1 hippocampal region. A, representative traces of pre-baclofen (basal), baclofen-induced, and baclofen-induced tertiapin-Q-blocked GIRK currents. B, representative traces of baclofen-induced tertiapin-blocked control, cholesterol-enriched and cholesterol-depleted GIRK currents. In A and B, Vholding = −80 mV. Summary data: (C) inward current densities at −100 mV and (D) outward current densities at +60 mV. E, I-V curves. Significant difference is indicated by an asterisk (*, p ≤ 0.05).

Cholesterol enrichment leads to an increase in the open probability of GIRK2∧

To obtain insights into the molecular mechanism that underlies cholesterol regulation of GIRK channels expressed in the brain, we focused on GIRK2, a channel that expresses as a homotetramer and is abundantly present in the brain. Because we have previously shown that GIRK1* was down-regulated by cholesterol, we hypothesized that GIRK2 subunits would dominate the effect of cholesterol on GIRK currents in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. We thus tested the effect of cholesterol on GIRK2∧ (GIRK2_E152D), a pore mutant of GIRK2 that increases its membrane expression and activity (61).

Our earlier studies have demonstrated that cholesterol enrichment leads to an increase in the open probability (62) of both GIRK4* and GIRK1/GIRK4, the channels predominantly expressed in the heart. In contrast, our data indicated that cholesterol does not affect the conductance of the channels (62). To test if this is also the case for the neuronal GIRK2 channel, we determined the effect of cholesterol on both the open probability and the conductance of GIRK2∧. To that end, we reconstituted the channel in planar lipid bilayers that enable control over the amount of cholesterol in the membrane-forming lipid mixture.

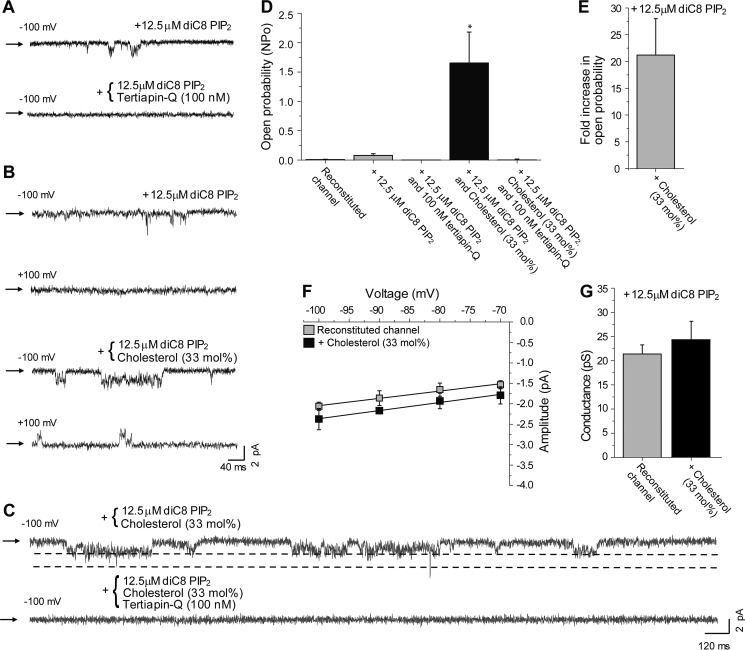

We first confirmed that the channel was incorporated in the bilayers by using the selective GIRK channel blocker tertiapin-Q (60). Fig. 3A shows representative single channel activity traces of the reconstituted channel in the absence and presence of tertiapin-Q. As can be seen in Fig. 3A and in the summary data in Fig. 3D, the resultant currents were sensitive to tertiapin-Q.

Figure 3.

Cholesterol leads to an increase in the open probability of GIRK2∧. Representative traces of GIRK2∧ reconstituted in lipid bilayers with 12.5 μm diC8-PI(4,5)P2 (A) at −100 mV without and with 100 nm of the channel blocker tertiapin-Q; B at −100 and 100 mV without and with 33 mol % cholesterol; and C, at −100 mV with 33 mol % cholesterol and without and with 100 nm of the channel blocker tertiapin-Q. D, summary data showing the effect of 12.5 μm diC8-PI(4,5)P2, 100 nm tertiapin-Q, and 33 mol % cholesterol on the open probability of GIRK2∧ (n = 3–6). E, summary data showing the effect of 33 mol % cholesterol on the open probability of GIRK2∧ in the presence of 12.5 μm diC8-PI(4,5)P2. F, current-voltage curves obtained from single channel recordings of GIRK2∧ reconstituted in lipid bilayers with and without cholesterol. The conductance was calculated from the slope of the linear fit of the currents recorded between −100 and −70 mV. G, summary data showing that cholesterol does not affect the conductance of GIRK2∧ in the presence of 12.5 μm diC8-PI(4,5)P2.

Next, we determined the effect of cholesterol on the open probability and conductance of the reconstituted channel in lipid bilayers. To that end, we used 33% cholesterol, the molar fraction of cholesterol found in native membranes of mammalian cells (63), and thereby commonly used for studying cholesterol effects on potassium channels (62, 64, 65). Representative single channel traces of the reconstituted GIRK2∧ channel protein in control bilayers and in bilayers with cholesterol are depicted in Fig. 3B for both inward (−100 mV) and outward (+100 mV) currents. To confirm that the effect of cholesterol on the currents observed was due to an increase in GIRK2∧ activity, we subjected the cholesterol-containing bilayers to tertiapin-Q. The extended trace in Fig. 3C demonstrates the sensitivity of the currents to tertiapin-Q confirming that the effect observed is an increase in GIRK2∧ activity by cholesterol.

As evident in the representative traces (Fig. 3, A and B), and quantified in the summary data (Fig. 3D), cholesterol increased the overall open probability of the channel, NPo, from 0.08 ± 0.03 in the absence of cholesterol to 1.7 ± 0.5 in the presence of 33% cholesterol. This implies that enriching the bilayers with 33% cholesterol resulted in a 21.2 ± 6.8-fold increase in the open probability of the channel (Fig. 3E).

In contrast, cholesterol did not have a significant effect on the conductance of GIRK2∧ (Fig. 3, F and G). Specifically, the conductance of the channel was 21.4 ± 1.9 pS in the absence of cholesterol, and 24.3 ± 3.8 pS in the presence of 33% cholesterol (Fig. 3, F and G).

Identification of cholesterol putative binding regions in GIRK2∧

Our earlier studies of a member of a different subfamily of inwardly rectifying potassium channels, Kir2.1, which is down-regulated by cholesterol (28), suggested that cholesterol may bind to two non-annular hydrophobic regions in the transmembrane domain of the channel (66). We hypothesized that despite the opposite impact of cholesterol on Kir2.1 and GIRK2∧ (down-regulated versus up-regulated, respectively), cholesterol would bind to similar regions of the transmembrane domain of the two channels. To test this hypothesis, we employed a combined computational-experimental approach.

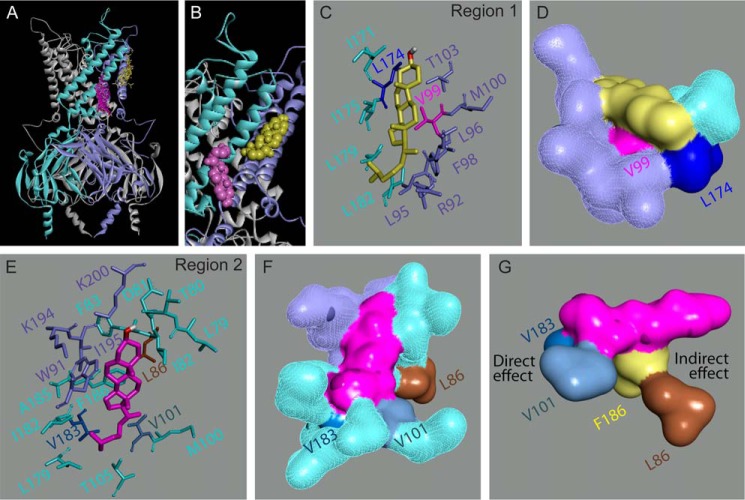

First, we carried out molecular docking analysis of cholesterol to the transmembrane domain of the channel and its interface with the cytosolic domain. To that end, we used a model of GIRK2 that was based on a crystal structure of the channel, PDB code 3SYO (67). Because the crystal structure lacked unstructured regions of the N and C termini, we modeled them to obtain a more complete structure of the channel. Analysis of the top 100 poses obtained from the molecular docking analysis led to two putative cholesterol-binding sites in GIRK2 located primarily at the center of the transmembrane domain and at the interface between the transmembrane and cytosolic domains of the channel (Fig. 4A). These results suggest that indeed cholesterol binds to two regions in GIRK2 that correspond to the putative cholesterol-binding sites of Kir2.1.

Figure 4.

Putative cholesterol binding sites in GIRK2∧. A, location of the cholesterol molecule (yellow and magenta) at two putative cholesterol-binding sites of GIRK2∧ between two adjacent subunits of the channel (cyan and violet) as obtained from molecular docking. B, enlargement of the channel region that includes the two putative cholesterol-binding sites. Stick (C) and surface (D) presentations depicting the residues that surround the cholesterol molecule (yellow) in site 1 including Val99 and Leu174. Stick (E) and surface (F) presentations depicting the residues that surround the cholesterol molecule (magenta) in site 2 including Leu86, Val101, and Val183. G, surface presentation of the cholesterol molecule of site 2 showing the direct interaction between the cholesterol molecule and Val101 and Val183 as well as its indirect interaction with Leu86 via Phe186.

To corroborate these results, we next determined the effect of mutations of four representative types of residues on the sensitivity of GIRK2∧ to cholesterol. The representative residues were identified based on interactions observed in poses that represent the two putative binding sites obtained from the docking analysis (Fig. 4B). The four types of residues and the specific mutations tested based on the computational analysis were as follows.

Type a: Directly interacting residues located at the bottom of each of the two putative binding sites

In both sites the cholesterol molecule was engulfed by multiple hydrophobic residues (Fig. 4, C and E). Among these, Val99 and Leu174 in site 1 and Val101 and Val183 in site 2 were located at the bottom of the corresponding binding pocket directly interacting with the cholesterol molecule (Fig. 4, D and F). Based on their locations, these residues were likely to be crucial for cholesterol modulation of the channel, and their mutation was expected to have a significant effect on the sensitivity of the channel to cholesterol.

Type b: A residue that could have an indirect effect on the sensitivity of the channel to cholesterol

The location of the Leu86 residue in site 2 suggested that it could play a role in the regulation of the channel by cholesterol in an indirect manner through the aromatic Phe186 residue that interacted with the ring structure of the cholesterol molecule (Fig. 4G). Thus, its mutation was predicted to affect the sensitivity of the channel to cholesterol.

Type c: Mutation-tolerant residue positioned in proximity to the cholesterol molecule, but not tightly packed

Ile195 is positioned along the ring structure of the cholesterol molecule in site 2 (Fig. 4E), albeit in a manner that could potentially tolerate mild mutations. Accordingly, its mutation was not expected to have an effect on cholesterol modulation of the channel.

Type d: A residue that faces away from both putative cholesterol-binding sites

The side chain of Met100 was facing the membrane away from both putative binding sites (Fig. 4, C and E). Accordingly, its mutation was not expected to affect the sensitivity of the channel to cholesterol.

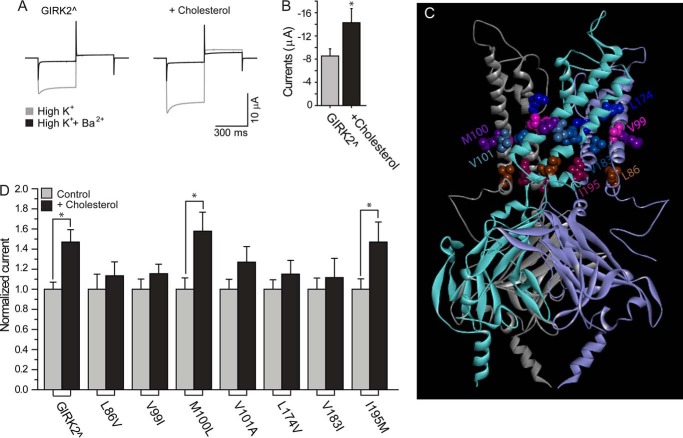

The locations of the above seven representative residues are depicted in Fig. 5C. We mutated each of these representative residues to a similar type of residue that differed from the original residue either by its size or three-dimensional structure of its side chain. This approach guarantees that in the majority of cases, the mutation would result in a functional channel, and that the effect on basal channel activity would be minimal (66). Also, because these mutations were very mild, only mutations of residues that were highly critical for cholesterol sensitivity of the channel were expected to have an effect.

Figure 5.

The effect of cholesterol on GIRK2∧ depends on residues in the transmembrane domain of the channel. A and B, cholesterol up-regulates GIRK2∧ when expressed in Xenopus oocytes. A, representative traces at −80 and +80 mV. B, summary data at −80 mV (n = 6–9). C, a ribbon presentation of GIRK2 channel showing the representative transmembrane residues (in ball presentation) whose effect on cholesterol sensitivity of the channel was tested in mutagenesis studies displayed in D. The location of the residues is depicted in ball presentation in two adjacent subunits of the channel. D, whole cell basal currents recorded in Xenopus oocytes at −80 mV showing the effect of cholesterol enrichment on GIRK2∧ and L86V, V99I, M100L, V101A, L174V, V183I, and I195M (n = 11–23). Significant difference is indicated by an asterisk (*, p ≤ 0.05).

To test the effect of these mutants on the sensitivity of the channel to cholesterol, we turned to the Xenopus oocyte heterologous expression system, a highly efficient tool for mechanistic studies of ion channels. To determine whether this expression system could serve as a model system, we first tested whether the effect of cholesterol on GIRK2∧ was similar to the effect of cholesterol on GIRK currents in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. As shown in Fig. 5, A and B, cholesterol had a similar impact on GIRK2∧ currents as on GIRK currents in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Enrichment of Xenopus oocytes with cholesterol resulted in an ∼2-fold increase in whole cell currents.

We thus proceeded to determine the effect of mutations of the four representative types of residues described above on the sensitivity of GIRK2∧ to cholesterol. As shown in Fig. 5D, five of the seven mutants tested were insensitive to cholesterol (residues of types a and b). More specifically, as predicted by the molecular docking analysis, whereas M100L (type d) and I195M (type c) mutations did not affect the sensitivity of the channel to cholesterol, the L86V (type b), V99I (type a), V101A (type a), L174V (type a), and V183I (type a) mutations abrogated its cholesterol sensitivity. The clear correspondence between the computational prediction and the mutagenesis data further support the notion that cholesterol binds to similar regions of the transmembrane domains of GIRK2∧ and Kir2.1.

Discussion

In recent years, cholesterol has emerged as a major ion channel regulator (e.g. for reviews, see Refs. 24–26). The major finding of the current study is that cholesterol enhances the currents of GIRK channels expressed in the brain. Because GIRK channels mediate many of the actions of inhibitory neurotransmitters (1–9), an increase in GIRK currents may be detrimental (16). Elevated cholesterol levels have been associated with the development of neurodegenerative disease (21–23). Thus, our findings regarding cholesterol modulation of neuronal GIRK currents may lead to novel approaches for prevention and therapy of cholesterol-driven neurodegenerative disease.

Our earlier data has shown that the GIRK4* homomer was up-regulated by cholesterol as was the GIRK1/GIRK4 heteromer, which underlies atrial KAch currents in the heart (17, 27). In contrast, GIRK1* was down-regulated by cholesterol suggesting that GIRK4 dominates the effect of cholesterol on GIRK channels expressed in the heart (17). In the brain, expression of GIRK4 channels is low, and GIRK1, GIRK2, and GIRK3 are more abundant (42–49). In view of the opposite impact of cholesterol on GIRK1 and GIRK4, it was therefore unclear whether an increase in cholesterol levels would up-regulate the activity of GIRK channels expressed in the brain or down-regulate it.

To determine the potential physiological relevance of increased levels of cholesterol in neurons, we first investigated whether a high cholesterol dietary intake could result in an increase in cholesterol levels in neurons that express GIRK channels. Our data demonstrated that a high-cholesterol diet results in a 2–3-fold increase in cholesterol levels in pyramidal neurons freshly isolated from the CA1 region of the hippocampus of rats. These results were surprising as the majority of cholesterol in the brain is synthesized de novo within the brain tissue, and an intact blood barrier is expected to preclude cholesterol influx from the blood (68). Moreover, increased dietary intake of cholesterol has been shown to inhibit endogenous synthesis of cholesterol (69, 70). An increase in cholesterol content has also been reported recently in cerebral arteries of rats following a high-cholesterol diet (71). Noteworthy, immediately prior to cholesterol determination, the arteries were stripped of the endothelial layer suggesting that diet-driven accumulation of cholesterol within the brain spread beyond the blood-brain barrier. Such equilibration of brain cholesterol content with blood cholesterol may be attributed to hypercholesterolemia-induced damage of the blood-brain barrier (72, 73).

To facilitate the studies of cholesterol regulation of GIRK channels in neurons, we determined the effect of cholesterol manipulation in vitro on cholesterol levels. This treatment yielded an increase in cholesterol levels within the hippocampal neuronal cells that was comparable with the cholesterol increase observed due to a high-cholesterol diet in vivo. This result paved the way to using in vitro manipulation of cholesterol levels in hippocampal neurons as a physiological model system to test the effect of cholesterol on neuronal GIRK channels.

Using neuronal cholesterol in vitro enrichment as a model system, our data showed that similarly to GIRK channels expressed in atrial cardiomyocytes, GIRK channels expressed in hippocampal CA1 neurons are also up-regulated by cholesterol despite the different subunit composition of the channel. These data indicated also that in the case of hippocampal GIRK channels, the effect of cholesterol on GIRK1 is dominated by the effect of cholesterol on the other GIRK subunits, GIRK2 and/or GIRK3. Because GIRK3 as a homomer does not form functional channels, we focused on GIRK2. Our data using both Xenopus oocytes and lipid bilayers demonstrated that similarly to GIRK currents in freshly dissociated CA1 neurons, GIRK2∧ is up-regulated by cholesterol.

Furthermore, the planar lipid bilayer data demonstrated that cholesterol up-regulates GIRK2∧ currents by increasing its open probability. This increase in channel activity by cholesterol is unlikely to be explained by the effect of cholesterol on membrane rigidity. An increase in membrane rigidity is expected to increase the energetic cost of the bilayer deformation that occurs when a protein undergoes a conformational change (74). Thus, to minimize this energetic cost, a decrease in channel activity would be expected (62). Yet, cholesterol increases GIRK2∧ activity suggesting that this regulation may depend instead on specific interactions between the channel and individual cholesterol molecules in the bilayer.

GIRK channels are a subfamily within the inwardly rectifying potassium (Kir) family of channels. Our recent studies of a member of the Kir2 subfamily, Kir2.1, which is down-regulated by cholesterol, led to the identification of cholesterol regulatory sites in the cytosolic domain of the channel as well as two putative cholesterol-binding sites in the transmembrane domain (66, 86). One primary binding site was located at the center of the transmembrane domain. The second binding site was located at the interface of the transmembrane and cytosolic domains, and was possibly a transient binding site. We have also shown that despite the opposite impact of cholesterol on Kir2.1 and GIRK4* (down-regulated versus up-regulated), mutations of residues in the cytosolic CD-loop of GIRK4* have a similar effect on the modulation of the channel by cholesterol as do mutations in the same regulatory region in Kir2.1 (27). In both cases, these mutations significantly reduced or even abrogated the sensitivity of the channels to cholesterol. We thus hypothesized that the binding site(s) of cholesterol in GIRK2∧ would be located in channel regions that correspond to the cholesterol putative binding regions identified in Kir2.1. These two putative binding sites were located between the transmembrane α-helices of Kir2.1 in nonannular regions that occluded membrane phospholipids. To determine whether this is the case in GIRK2∧ as well, we used a combined computational-experimental approach. We first performed a molecular docking study to search for putative cholesterol-binding sites. Subsequently, we tested the results obtained computationally in a functional study, and determined the effect of mutations of representative transmembrane residues of GIRK2∧ on its cholesterol sensitivity. We observed a clear correspondence between the predictions obtained based on the molecular docking analysis and the mutagenesis data. Specifically, residues whose mutation significantly affected the sensitivity of GIRK2∧ to cholesterol were predicted to either directly interact with the cholesterol molecule (Val99, Val101, Leu174, and Val183) or affect the sensitivity of the channel to cholesterol via a critical adjacent residue (Leu86 through the aromatic Phe186). Two of these residues, Val99 and Leu174, were located in a site at the center of the transmembrane domain (site 1). Leu86, Val101, and Val183, on the other hand, were located at a second site at the interface of the transmembrane and cytosolic domains (site 2). This correspondence between the functional assay and the results of the molecular docking supports the notion that GIRK2∧ has two putative cholesterol-binding sites located in the same regions as the putative sites in Kir2.1.

Three cholesterol-binding motifs have been previously identified. The first and well established cholesterol recognition amino acid consensus (CRAC) motif is -(L/V)X1–5YX1–5(R/K)-, where X1–5 represents 1–5 residues of any amino acid (75, 76). This motif has been identified in several ion channels (77–79). A second motif is the cholesterol consensus motif that was proposed based on the complexed crystal structure of the β-adrenergic receptor with cholesterol. This motif includes residues on adjacent helices of the G protein-coupled receptor: (W/Y)(I/V/L)(K/R) on one helix and (F/Y/R) on a second helix (80). Last, the inverted CRAC sequence, the CARC motif, (R/K)X1–5(Y/F)X1–5(L/V), has been suggested to be responsible for cholesterol interactions with AChR, and was shown to be more consistent in predicting cholesterol recognition motifs in integral membrane proteins (81). The common characteristic of these three motifs is that they all include a hydrophobic residue (I/L/V), an aromatic residue (F/Y/W), and a positively charged residue (R/K).

Our earlier studies of putative cholesterol-binding sites in Kir2.1 suggested that although a CARC motif may represent a part of site 2, the cholesterol binding region at site 1 that did not include a positively charged residue differed from all three previously identified cholesterol binding motifs (66). In GIRK2∧, site 1 partially overlaps with a CARC motif: Arg92-Phe98-Val101. Site 2, on the other hand, includes residues Trp91-Ile195-Lys200 from one subunit, and Phe186 from an adjacent subunit, thereby resembling the cholesterol consensus motif. However, whereas Trp91, Ile195, and Lys200 are located in proximity to each other at the interface between the transmembrane and cytosolic domains, they belong to different helices. Trp91 is in the outer helix, Ile195 is in the inner helix, and Lys200 is in the helix that links the inner helix to the cytosolic domain. Thus, similarly to Kir2.1, the putative cholesterol binding sites in GIRK2∧ also diverge from the known cholesterol binding motifs.

In summary, our study unveiled the molecular details of cholesterol-driven up-regulation of neuronal GIRK2 channel function. This channel represents an addition to the short list of channels that are up-regulated by elevated levels of cholesterol. Our data indicate that this effect is due to an increase in the open probability of the channel, and is likely driven by direct cholesterol binding to the transmembrane domain of the channel. These data may ultimately lead to the development of novel approaches to counteract the effect of elevated cholesterol on neuronal and brain function.

Experimental procedures

Rat high cholesterol diet

A group of 25-day-old male Sprague-Dawley rats was placed on a high-cholesterol diet (2% cholesterol in standard rodent food) (Harland-Teklad). Another group of the same age was fed an isocaloric, cholesterol-free diet from the same supplier. Rats were sacrificed after 18–23 weeks on control or high-cholesterol diet.

Preparation of freshly dissociated hippocampal neurons

Hippocampi from adult male Sprague-Dawley rats were dissected in ice-cold, oxygenated dissociation solution containing (in mm): 82 Na2SO4, 30 K2SO4, 5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, and 0.001% phenol red indicator, pH 7.4. The CA1 region was dissected out and immediately incubated for 9 min at 37 °C in dissociation solution containing 3 mg/ml of protease (Type XXIII, Sigma). The enzyme solution was then replaced with dissociation solution containing 1 mg/ml of trypsin inhibitor and 1 mg/ml of bovine serum albumin, and the tissue was allowed to cool to room temperature under an oxygen atmosphere. As cells were needed, tissue was triturated to release individual cells into a recording chamber filled with Tyrode's extracellular recording solution containing (in mm): 150 NaCl, 8 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4, with NaOH. Cells were used within 6–8 h following incubation in the dissociation solution (see above).

Identification of pyramidal hippocampal neurons

CA1 pyramidal neurons were identified morphologically under an Olympus IX-70 microscope (×40), based on size and shape (82). Cells identified as pyramidal neurons had a large pyramidal-shaped cell body with a thick apical dendritic stump and, in some neurons, one to four basal dendritic stumps. We confirmed that this morphology corresponded to a neuronal tissue by immunofluorescent staining of freshly dispersed neurons using a chicken polyclonal IgY primary antibody against a neuron-specific enolase (1:100, Abcam) and a DyLight 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:100, Abcam) following conventional procedures (52, 83).

Filipin staining

Cholesterol measurements in isolated neurons from rats on a high-cholesterol diet were performed in three independent experiments. Each experiment involved one rat on a high-cholesterol diet and one rat representing an age-matched control that received regular rodent chow. Filipin staining was performed immediately after neuron isolation. In each experiment, staining procedures were performed simultaneously on the preparations from neurons isolated from the rats on a high-cholesterol diet versus control.

Cholesterol measurements following in vitro cholesterol manipulation of isolated neurons were performed in two sets of experiments. In the first set of experiments, one rat donor was used for all three groups (naive cholesterol, cholesterol depletion, and cholesterol enrichment), and in the second set of experiments, a mixture of neurons was obtained from two donors. This mixture was used for imaging of all three groups (naive cholesterol, cholesterol depletion, and cholesterol enrichment). For experiments with cholesterol manipulation in vitro, cells were isolated, immediately subjected to either manipulation of cholesterol level or control incubation in Tyrode's solution, and then immediately stained with filipin. In each set of experiments, the staining procedures were performed simultaneously on preparations with naive cholesterol, depleted, and enriched cholesterol levels.

Filipin staining was performed according to a conventional protocol. In brief, freshly dispersed neurons on glass slips were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Upon paraformaldehyde washout, cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton in PBS for 10 min. Upon washout of Triton, cells were stained with filipin-containing PBS (25 μg/ml prepared from a stock solution of 10 mg/ml of filipin in DMSO) for 2 h at room temperature in the dark. Upon washout, slips were mounted using ProLong AntiFade kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and sealed using clear nail polish. Fluorescence images were obtained using 405 laser line of Olympus FV-1000 laser scanning confocal system (Center Valley, PA). Fluorescence was quantified using the built-in function in FV10-ASW 3.1 software (Olympus American Inc., Center Valley, PA). A minimum of 4–5 cells were imaged from each slide. Fluorescence was quantified by measuring the intensity of pixels above a set threshold defined as the mean fluorescence intensity outside the cells (i.e. background).

Cholesterol enrichment and depletion of hippocampal neurons

As previously described for other cell types (84), CA1 pyramidal neurons were depleted of cholesterol by exposure to the cholesterol acceptor MβCD. Alternatively, cells were enriched with cholesterol by treatment with MβCD saturated with cholesterol, a well known cholesterol donor. Depletion was carried out with freshly prepared 5 mm MβCD in Tyrode's extracellular recording solution for 30 min. For enrichment, an MβCD-cholesterol complex was prepared in Tyrode's extracellular recording solution as described previously (59). In brief, cholesterol powder was added to 5 mm MβCD in Tyrode's extracellular recording solution. This preparation was sonicated, and then incubated overnight in a shaking water bath at 37 °C. The cells were incubated with the MβCD-cholesterol complex-containing solution for 1 h.

Whole cell voltage-clamp recordings from pyramidal hippocampal neurons

Recordings of CA1 pyramidal neurons were carried out in the presence of Tyrode's extracellular recording solution (mm) 150 NaCl, 4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4. Patch pipettes are pulled from 100-μl calibrated pipettes for electrophysiological recordings with aspirator already included into the pipette (Drummond Scientific Company, Broomall, PA). Pipette resistances ranged from 2 to 5 mΩ when filled with internal solution containing (in mm): 135 potassium gluconate, 10 NaCl, 1 EGTA, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 14 creatine phosphate (Tris salt), 4 Mg-ATP, and 0.3 GTP (Tris salt), pH adjusted to 7.4 with KOH ([Mg2+]free ≈ 2.1 mm). An Ag/AgCl electrode was used as ground electrode. The liquid junction potential between the internal solution and Tyrode's solution (in which the current is zeroed before obtaining a seal) was calculated to reach 16.4 mV (pCLAMP9.2, Molecular Devices). Membrane potentials were not corrected for this junction potential. Experiments were carried out at room temperature (21 °C). GIRK currents were acquired using an EPC8 (HEKA) amplifier and digitized at 1 kHz using a Digidata 1320A A/D converter and pCLAMP8 software (Molecular Devices). Macroscopic currents were evoked from a holding potential of −80 mV by 200-ms long, 10-mV depolarizing steps from −120 to +60 mV. Currents were low pass-filtered at 1 kHz and sampled at 5 kHz. Current amplitude was averaged within 100–150 ms after the start of the depolarizing step. The extracellular solution also contained 1 μm tetrodotoxin and 10 μm NiCl2. To evoke GIRK currents, we used 100 μm baclofen (52), a GABAB receptor agonist. Pre-baclofen (basal) currents were subtracted from baclofen-induced currents to isolate baclofen-specific currents. The channel was then selectively blocked with 100 nm tertiapin-Q (60). The resulting currents were then subtracted from the baclofen-specific currents to isolate the tertiapin-Q-sensitive GIRK component. Subtraction of the traces was performed using a built-in function in Clampfit 9.2 software (Molecular Devices). Notably, tertiapin-Q has been shown to partially inhibit the outward currents of calcium- and voltage-gated potassium channels of large conductance (BK) at a similar nanomolar concentration (85). However, under the experimental conditions used in this study, the contribution of BK channel block to the tertiapin-Q-sensitive currents is expected to be insignificant. First, the blocking kinetics of the GIRK and BK channels by tertiapin-Q differ substantially. Second, the application protocols of tertiapin-Q are very different. Specifically, inhibition of BK channels by tertiapin-Q is use- and voltage-dependent, and requires over 15 min of stimulation by depolarizing steps (85). In contrast, inhibition of GIRK channels by tertiapin-Q does not involve continuous stimulation of the cell with voltage steps, and occurs within 1 min (60). Data were presented as mean ± S.E. Statistical analysis was performed using InStat 3.0 (GraphPad). Significance was obtained using either t test or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey test in accordance with experimental design. Final plotting and fitting of the data were conducted using Origin 7.0 (Originlab).

Expression of recombinant channels in Xenopus oocytes

cRNAs were transcribed in vitro using the “Message Machine” kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Oocytes were isolated and microinjected as described previously (76, 86). Expression of channel protein in Xenopus oocytes was accomplished by injection of the desired amount of cRNA. Each oocyte was injected with 2 ng of channel cRNA. All oocytes were maintained at 17 °C. Two-electrode voltage-clamp recordings were performed 2 days following injection. For harvesting the protein-containing membrane vesicles for lipid bilayer experiments, oocytes were processed as previously described (87, 88).

Bilayer experiments

Bilayer experiments were performed as described (62, 87). The experimental apparatus consisted of two 1.4-ml chambers separated by a Teflon film that contains a single hole (200 μm in diameter). The bilayer recording solution in both chambers consisted of (mm): 150 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Tris/HEPES, pH 7.4. Bilayer lipids were dissolved in chloroform, then dried under N2 atmosphere and re-suspended in n-decane as previously described (64). A lipid bilayer was formed by “painting” the hole with a 1:1 mixture of l-α-phosphatidylethanolamine (POPE) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-(phosphor-l-serine) sodium salt (POPS) dissolved in n-decane to a final concentration of 25 mg/ml. For experiments with cholesterol, cholesterol powder was first dissolved in chloroform and then added to the lipid mixture in chloroform to reach the desired concentration of 33 mol % prior to drying under N2. The cis side was defined as the chamber connected to the voltage-holding electrode, and all voltages were referenced to the trans side (ground) of the chamber. To activate the GIRK channel (90), 12.5 μm diC8-PI(4,5)P2 was added to the cis chamber (62, 87). The pellet obtained from the membrane preparation of oocytes injected with the channel-coding cRNA was re-suspended in 100 μl of bilayer recording solution. After bilayer formation (80–120 pF), a 5-μl aliquot of resuspended membrane preparation was added to the cis side of the chamber and stirred for 5 min. The orientation of the channel insertion was defined by the rectification in response of a set of voltages from −100 to +100 mV. Records were low-passed filtered at 1 kHz, and sampled at 5 kHz. The identity of the channel was confirmed by the addition of the selective blocker tertiapin-Q (100 nm) (60) to the chamber corresponding to the extracellular side of the bilayer. Ion currents were recorded for 20 s using a Warner BC-525D amplifier, low-pass filtered at 1 kHz using the 4-pole Bessel filter built in the amplifier, and sampled at 5 kHz with Digidata 1322A/pCLAMP 9.2 (Molecular Devices). The bilayer channel unitary current amplitude (pA) and channel open probability (Po) were determined using a built-in function in Clampfit 9.2 (Molecular Devices). If multiple channel events (e.g. opening levels) were observed in a single bilayer recording, the total number of functional channels (n) in the bilayer was estimated from the number of opening levels at −100 mV. In such cases, the product of the number of channels (n) and the Po was used to measure the channel activity in the bilayer. Data were presented as mean ± S.E. Statistical analysis was performed using InStat 3.0 (GraphPad). Significance was obtained using either t test or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey test in accordance with the experimental design. Final plotting and fitting of the data were conducted using Origin 7.0 (Originlab).

Homology modeling

A combined ROSETTA/SWISS-MODEL protocol was used for the development and refinement of the structures. First, multiple sequence alignment was performed using CLUSTALW algorithm. Then models were generated from the alignment in a stepwise manner. Backbone coordinates for the aligned positions were extracted from the template and regions of insertions/deletions in the alignment were modeled by either searching loop library or by a search in the conformational space using constraint space programming. The backbone atom positions of the template structure were averaged for the generated models with multiple sequence alignments. The templates were weighted by their sequence similarity to the target sequence and outlier atom positions were excluded. A scoring function was used to assess favorable interactions (hydrogen bonds, disulfide bridges) and unfavorable close contacts for the determination of the side chain conformations that were derived from a backbone-dependent rotamer library. We used QMEAN score to provide an estimate for the degree of nativeness of the structural features observed in the model and determine the quality of the models compared with experimental structures. The score function penalized structural features of models that exhibited considerable deviations from the expected observed properties including, for example, unexpected solvent accessibility, inter-atomic packing, and backbone geometry.

Molecular docking

The cholesterol molecule was docked to the channel using AutoDock 4 (91). Input files for both the channel and cholesterol (the ligand) were prepared using MGL Tools 1.5.2 (91). The grid maps for van der Waals and electrostatic energies were prepared using AutoGrid version 4.0 with 126 × 126 × 126 points spaced at 0.375 Å distances. Default Autodock parameters were used except that each docking simulation consisted of 100 runs of a Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm. As a genetic algorithm, the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm uses the language of natural genetics in which the state of the ligand corresponds to the genotype, and its atomic coordinates correspond to the phenotype. In the implementation of the AutoDock genetic algorithm, the genes were considered as a string of real values representing the Cartesian coordinates for the ligand translation, four variables for the quaternion defined the orientation of the ligand, and one value defined each ligand torsion. In the initial step of the conformational space search of the ligand, we generated a population of random conformers that uniformly covered the grid space. Subsequently, the population of each generation was subjected to mutation, crossover, and a local search. The size of the initial random population of individuals was set to 150 individuals, the maximal number of energy evaluations was 2.5 × 106, the maximal number of generations was set as 27,000, the probability of performing local search on an individual was set as 0.06, the probability that a gene would undergo a random change was 0.02, and the crossover probability was 0.80.

Cholesterol enrichment of Xenopus oocytes

Treatment of Xenopus oocytes with a mixture of cholesterol and lipids has been shown to increase the cholesterol/phospholipid molar ratio of the plasma membrane of the oocytes (89). Thus, to enrich the oocytes with cholesterol we used a 1:1:1 (w/w/w) mixture containing cholesterol, porcine brain l-α-phosphatidylethanolamine, and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (Avanti Polar Lipids, Birmingham, AL). The mixture was evaporated to dryness under a stream of nitrogen. The resultant pellet was suspended in a buffered solution consisting of 150 mm KCl and 10 mm Tris/HEPES, pH 7.4, and sonicated at 80 kHz in a bath sonicator (Laboratory Supplies, Hicksville, NY). Xenopus oocytes were treated with a cholesterol/lipid mixture for 1 h immediately prior to electrophysiological recordings.

Two-electrode voltage clamp recording and analysis

Whole cell currents were measured by conventional two microelectrode voltage clamp with a GeneClamp 500 amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA), as reported previously (48, 86). A high potassium solution was used to superfuse oocytes (96 mm KCl, 1 mm NaCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 5 mm KOH/HEPES, pH 7.4). Basal currents represent the difference of inward currents obtained (at −80 mV) in the presence of 3 mm BaCl2 in high potassium solution from those in the absence of Ba2+. Data were presented as mean ± S.E. Statistical analysis was performed using Origin 7.0 (Originlab). Significance was obtained using t test or one-way ANOVA in accordance with the experimental design. Final plotting of the data were conducted using Origin 7.0 (Originlab).

Author contributions

A. N. B. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and participated in the writing of the manuscript. S. D. and S. N. designed and performed the homology modeling and molecular docking. A. R. D. initiated the project, designed and performed experiments, analyzed experimental data and computational results, and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Diomedes Logothetis (VCU) for facilitating the two-electrode voltage clamp experiments in Xenopus oocytes and for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Alex Dopico (UT HSC) for facilitating the bilayers experiments and helpful discussions. In addition, we deeply thank Shivantika Bisen (UT HSC) for excellent technical assistance. Computational resources from Compute Canada/WestGrid are gratefully acknowledged.

This work was supported in part by Scientist Development Grant 11SDG5190025 from the American Heart Association (to A. R.-D.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- GIRK

- G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium

- Kir channel

- inwardly rectifying potassium channel

- PI(4,5)P2

- phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- MβCD

- methyl-β-cyclodextrin

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- diC8

- 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycerol.

References

- 1. Dascal N. (1997) Signalling via the G protein-activated K+ channels. Cell Signal. 9, 551–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hibino H., Inanobe A., Furutani K., Murakami S., Findlay I., and Kurachi Y. (2010) Inwardly rectifying potassium channels: their structure, function, and physiological roles. Physiol. Rev. 90, 291–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lüscher C., and Slesinger P. A. (2010) Emerging roles for G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 301–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andrade R., Malenka R. C., and Nicoll R. A. (1986) A G protein couples serotonin and GABA(B) receptors to the same channels in hippocampus. Science 234, 1261–1265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kofuji P., Hofer M., Millen K. J., Millonig J. H., Davidson N., Lester H. A., and Hatten M. E. (1996) Functional analysis of the weaver mutant GIRK2 K+ channel and rescue of weaver granule cells. Neuron 16, 941–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Labouèbe G., Lomazzi M., Cruz H. G., Creton C., Luján R., Li M., Yanagawa Y., Obata K., Watanabe M., Wickman K., Boyer S. B., Slesinger P. A., and Lüscher C. (2007) RGS2 modulates coupling between GABAB receptors and GIRK channels in dopamine neurons of the ventral tegmental area. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 1559–1568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Michaeli A., and Yaka R. (2010) Dopamine inhibits GABA A currents in ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons via activation of presynaptic G-protein coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium channels. Neuroscience 165, 1159–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Velimirovic B. M., Koyano K., Nakajima S., and Nakajima Y. (1995) Opposing mechanisms of regulation of a G-protein-coupled inward rectifier K+ channel in rat brain neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 1590–1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Surmeier D. J., Mermelstein P. G., and Goldowitz D. (1996) The weaver mutation of GIRK2 results in a loss of inwardly rectifying K+ current in cerebellar granule cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 11191–11195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lüscher C., Jan L. Y., Stoffel M., Malenka R. C., and Nicoll R. A. (1997) G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRKs) mediate postsynaptic but not presynaptic transmitter actions in hippocampal neurons. Neuron 19, 687–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sharon D., Vorobiov D., and Dascal N. (1997) Positive and negative coupling of the metabotropic glutamate receptors to a G protein-activated K+ channel, GIRK, in Xenopus oocytes. J. Gen. Physiol. 109, 477–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hille B. (1992) G protein-coupled mechanisms and nervous signaling. Neuron 9, 187–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wickman K., and Clapham D. E. (1995) Ion channel regulation by G proteins. Physiol. Rev. 75, 865–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. David M., Richer M., Mamarbachi A. M., Villeneuve L. R., Dupré D. J., and Hebert T. E. (2006) Interactions between GABA-B1 receptors and Kir3 inwardly rectifying potassium channels. Cell Signal. 18, 2172–2181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lober R. M., Pereira M. A., and Lambert N. A. (2006) Rapid activation of inwardly rectifying potassium channels by immobile G-protein-coupled receptors. J. Neurosci. 26, 12602–12608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cooper A., Grigoryan G., Guy-David L., Tsoory M. M., Chen A., and Reuveny E. (2012) Trisomy of the G protein-coupled K+ channel gene, Kcnj6, affects reward mechanisms, cognitive functions, and synaptic plasticity in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 2642–2647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Deng W., Bukiya A. N., Rodríguez-Menchaca A. A., Zhang Z., Baumgarten C. M., Logothetis D. E., Levitan I., and Rosenhouse-Dantsker A. (2012) Hypercholesterolemia induces up-regulation of KACh cardiac currents via a mechanism independent of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and Gβγ. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 4925–4935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kruth H. S. (2001) Lipoprotein cholesterol and atherosclerosis. Curr. Mol. Med. 1, 633–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ross R. (1999) Atherosclerosis: an inflammatory disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 340, 115–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Steinberg D. (2002) Atherogenesis in perspective: hypercholesterolemia and inflammation as partners in crime. Nat. Med. 8, 1211–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ho Y. S., Poon D. C., Chan T. F., and Chang R. C. (2012) From small to big molecules: how do we prevent and delay the progression of age-related neurodegeneration? Curr. Pharm. Des. 18, 15–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stefani M., and Liguri G. (2009) Cholesterol in alzheimer's disease: unresolved questions. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 6, 15–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ong W. Y., and Halliwell B. (2004) Iron, atherosclerosis, and neurodegeneration: a key role for cholesterol in promoting iron-dependent oxidative damage? Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1012, 51–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maguy A., Hebert T. E., and Nattel S. (2006) Involvement of lipid rafts and caveolae in cardiac ion channel function. Cardiovasc. Res. 69, 798–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Levitan I., Fang Y., Rosenhouse-Dantsker A., and Romanenko V. (2010) Cholesterol and ion channels. Subcell. Biochem. 51, 509–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rosenhouse-Dantsker A., Mehta D., and Levitan I. (2012) Regulation of ion channels by membrane lipids. Compr. Physiol. 2, 31–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rosenhouse-Dantsker A., Leal-Pinto E., Logothetis D. E., and Levitan I. (2010) Comparative analysis of cholesterol sensitivity of Kir channels: Role of the CD loop. Channels 4, 63–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Romanenko V. G., Fang Y., Byfield F., Travis A. J., Vandenberg C. A., Rothblat G. H., and Levitan I. (2004) Cholesterol sensitivity and lipid raft targeting of Kir2.1 channels. Biophys. J. 87, 3850–3861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tucker S. J., Gribble F. M., Zhao C., Trapp S., and Ashcroft F. M. (1997) Truncation of Kir6.2 produces ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the absence of the sulphonylurea receptor. Nature 387, 179–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bolotina V., Omelyanenko V., Heyes B., Ryan U., and Bregestovski P. (1989) Variations of membrane cholesterol alter the kinetics of Ca2+-dependent K+ channels and membrane fluidity in vascular smooth muscle cells. Pflügers Arch. 415, 262–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dopico A. M., Bukiya A. N., and Singh A. K. (2012) Large conductance, calcium- and voltage-gated potassium (BK) channels: regulation by cholesterol. Pharmacol. Ther. 135, 133–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu C. C., Su M. J., Chi J. F., Chen W. J., Hsu H. C., and Lee Y. T. (1995) The effect of hypercholesterolemia on the sodium inward currents in cardiac myocyte. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 27, 1263–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Toselli M., Biella G., Taglietti V., Cazzaniga E., and Parenti M. (2005) Caveolin-1 expression and membrane cholesterol content modulate N-type calcium channel activity in NG108-15 cells. Biophys. J. 89, 2443–2457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Levitan I., Christian A. E., Tulenko T. N., and Rothblat G. H. (2000) Membrane cholesterol content modulates activation of volume-regulated anion current in bovine endothelial cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 115, 405–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lockwich T. P., Liu X., Singh B. B., Jadlowiec J., Weiland S., and Ambudkar I. S. (2000) Assembly of Trp1 in a signaling complex associated with caveolin-scaffolding lipid raft domains. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 11934–11942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chubinskiy-Nadezhdin V. I., Negulyaev Y. A., and Morachevskaya E. A. (2011) Cholesterol depletion-induced inhibition of stretch-activated channels is mediated via actin rearrangement. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 412, 80–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shlyonsky V. G., Mies F., and Sariban-Sohraby S. (2003) Epithelial sodium channel activity in detergent-resistant membrane microdomains. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 284, F182–F188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Awayda M. S., Awayda K. L., Pochynyuk O., Bugaj V., Stockand J. D., and Ortiz R. M. (2011) Acute cholesterol-induced anti-natriuretic effects: role of epithelial Na+ channel activity, protein levels, and processing. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 1683–1695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Krapivinsky G., Gordon E. A., Wickman K., Velimirović B., Krapivinsky L., and Clapham D. E. (1995) The G-protein-gated atrial K+ channel IKACh is a heteromultimer of two inwardly rectifying K+-channel proteins. Nature 374, 135–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chan K. W., Sui J. L., Vivaudou M., and Logothetis D. E. (1996) Control of channel activity through a unique amino acid residue of a G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channel subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 14193–14198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vivaudou M., Chan K. W., Sui J. L., Jan L. Y., Reuveny E., and Logothetis D. E. (1997) Probing the G-protein regulation of GIRK1 and GIRK4, the two subunits of the KACh channel, using functional homomeric mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 31553–31560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wickman K., Karschin C., Karschin A., Picciotto M. R., and Clapham D. E. (2000) Brain localization and behavioral impact of the G-protein-gated K+ channel subunit GIRK4. J. Neurosci. 20, 5608–5615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lesage F., Guillemare E., Fink M., Duprat F., Heurteaux C., Fosset M., Romey G., Barhanin J., and Lazdunski M. (1995) Molecular properties of neuronal G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 28660–28667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lesage F., Duprat F., Fink M., Guillemare E., Coppola T., Lazdunski M., and Hugnot J. P. (1994) Cloning provides evidence for a family of inward rectifier and G-protein coupled K+ channels in the brain. FEBS Lett. 353, 37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bond C. T., Ammälä C., Ashfield R., Blair T. A., Gribble F., Khan R. N., Lee K., Proks P., Rowe I. C., Sakura H., Ashford M. J., Adelman J. P., and Ashcroft F. M. (1995) Cloning and functional expression of the cDNA encoding an inwardly-rectifying potassium channel expressed in pancreatic β-cells and in the brain. FEBS Lett. 367, 61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nelson C. S., Marino J. L., and Allen C. N. (1997) Cloning and characterization of Kir3.1 (GIRK1) C-terminal alternative splice variants. Mol. Brain Res. 46, 185–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liao Y. J., Jan Y. N., and Jan L. Y. (1996) Heteromultimerization of G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K + channel proteins GIRK1 and GIRK2 and their altered expression in weaver brain. J. Neurosci. 16, 7137–7150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. He C., Yan X., Zhang H., Mirshahi T., Jin T., Huang A., and Logothetis D. E. (2002) Identification of critical residues controlling G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channel activity through interactions with the βγ subunits of G proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6088–6096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Koyrakh L., Luján R., Colón J., Karschin C., Kurachi Y., Karschin A., and Wickman K. (2005) Molecular and cellular diversity of neuronal G-protein-gated potassium channels. J. Neurosci. 25, 11468–11478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chen X., and Johnston D. (2005) Constitutively active G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channels in dendrites of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 25, 3787–3792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. VanDongen A. M., Codina J., Olate J., Mattera R., Joho R., Birnbaumer L., and Brown A. M. (1988) Newly identified brain potassium channels gated by the guanine nucleotide binding protein Go. Science 242, 1433–1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Leaney J. L. (2003) Contribution of Kir3.1, Kir3.2A and Kir3.2C subunits to native G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium currents in cultured hippocampal neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 18, 2110–2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Grigg J. J., Kozasa T., Nakajima Y., and Nakajima S. (1996) Single-channel properties of a G-protein-coupled inward rectifier potassium channel in brain neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 75, 318–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Witkowski G., Szulczyk B., Rola R., and Szulczyk P. (2008) D1 dopaminergic control of G protein-dependent inward rectifier K+ (GIRK)-like channel current in pyramidal neurons of the medial prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience 155, 53–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Miyake M., Christie M. J., and North R. A. (1989) Single potassium channels opened by opioids in rat locus ceruleus neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 3419–3422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kawano T., Zhao P., Nakajima S., and Nakajima Y. (2004) Single-cell RT-PCR analysis of GIRK channels expressed in rat locus coeruleus and nucleus basalis neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 358, 63–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bajic D., Koike M., Albsoul-Younes A. M., Nakajima S., and Nakajima Y. (2002) Two different inward rectifier K+ channels are effectors for transmitter-induced slow excitation in brain neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 14494–14499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bukiya A. N., and Rosenhouse-Dantsker A. (2015) Hypercholesterolemia effect on potassium channels in Hypercholesterolemia (Kumar S. A., ed) pp. 95–119, Intech, Croatia [Google Scholar]

- 59. Christian A. E., Haynes M. P., Phillips M. C., and Rothblat G. H. (1997) Use of cyclodextrins for manipulating cellular cholesterol content. J. Lipid Res. 38, 2264–2272 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kitamura H., Yokoyama M., Akita H., Matsushita K., Kurachi Y., and Yamada M. (2000) Tertiapin potently and selectively blocks muscarinic K+ channels in rabbit cardiac myocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 293, 196–205 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yi A., Lin Y.-F., Jan Y. N., and Jan L. Y. (2001) Yeast screen for constitutively active mutant G protein-activated potassium channels. Neuron 29, 657–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bukiya A. N., Osborn C. V., Kuntamallappanavar G., Toth P. T., Baki L., Kowalsky G., Oh M. J., Dopico A. M., Levitan I., and Rosenhouse-Dantsker A. (2015) Cholesterol increases the open probability of cardiac KACh currents. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1848, 2406–2413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gimpl G., Burger K., and Fahrenholz F. (1997) Cholesterol as modulator of receptor function. Biochemistry 36, 10959–10974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bukiya A. N., Belani J. D., Rychnovsky S., and Dopico A. M. (2011) Specificity of cholesterol and analogs to modulate BK channels points to direct sterol-channel protein interactions. J. Gen. Physiol. 137, 93–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Crowley J. J., Treistman S. N., and Dopico A. M. (2003) Cholesterol antagonizes ethanol potentiation of human brain BKCa channels reconstituted into phospholipid bilayers. Mol. Pharmacol. 64, 365–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Rosenhouse-Dantsker A., Noskov S., Durdagi S., Logothetis D. E., and Levitan I. (2013) Identification of novel cholesterol-binding regions in Kir2 channels. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 31154–31164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Whorton M. R., and MacKinnon R. (2011) Crystal structure of the mammalian GIRK2 K+ channel and gating regulation by G proteins, PIP2, and sodium. Cell 147, 199–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Björkhem I., and Meaney S. (2004) Brain cholesterol: long secret life behind a barrier. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 806–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Jones P. J., Pappu A. S., Hatcher L., Li Z. C., Illingworth D. R., and Connor W. E. (1996) Dietary cholesterol feeding suppresses human cholesterol synthesis measured by deuterium incorporation and urinary mevalonic acid levels. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 16, 1222–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Clayton P. T. (1998) Disorders of cholesterol biosynthesis. Arch. Dis. Child 78, 185–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bukiya A., Dopico A. M., Leffler C. W., and Fedinec A. (2014) Dietary cholesterol protects against alcohol-induced cerebral artery constriction. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 38, 1216–1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Acharya N. K., Levin E. C., Clifford P. M., Han M., Tourtellotte R., Chamberlain D., Pollaro M., Coretti N. J., Kosciuk M. C., Nagele E. P., Demarshall C., Freeman T., Shi Y., Guan C., Macphee C. H., Wilensky R. L., and Nagele R. G. (2013) Diabetes and hypercholesterolemia increase blood-brain barrier permeability and brain amyloid deposition: beneficial effects of the LpPLA2 inhibitor darapladib. J. Alzheimers Dis. 35, 179–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Dias I. H., Polidori M. C., and Griffiths H. R. (2014) Hypercholesterolaemia-induced oxidative stress at the blood-brain barrier. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 42, 1001–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lundbaek J. A., Collingwood S. A., Ingólfsson H. I., Kapoor R., and Andersen O. S. (2010) Lipid bilayer regulation of membrane protein function: Gramicidin channels as molecular force probes. J. R. Soc. Interface 7, 373–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Li H., and Papadopoulos V. (1998) Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor function in cholesterol transport: identification of a putative cholesterol recognition/interaction amino acid sequence and consensus pattern. Endocrinology 139, 4991–4997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Epand R. M. (2006) Cholesterol and the interaction of proteins with membrane domains. Prog. Lipid Res. 45, 279–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Picazo-Juárez G., Romero-Suárez S., Nieto-Posadas A., Llorente I., Jara-Oseguera A., Briggs M., McIntosh T. J., Simon S. A., Ladrón-de-Guevara E., Islas L. D., and Rosenbaum T. (2011) Identification of a binding motif in the S5 helix that confers cholesterol sensitivity to the TRPV1 ion channel. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 24966–24976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Singh A. K., McMillan J., Bukiya A. N., Burton B., Parrill A. L., and Dopico A. M. (2012) Multiple cholesterol recognition/interaction amino acid consensus (CRAC) motifs in cytosolic C tail of Slo1 subunit determine cholesterol sensitivity of Ca2+- and voltage-gated K+ (BK) channels. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 20509–20521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Baier C. J., Fantini J., and Barrantes F. J. (2011) Disclosure of cholesterol recognition motifs in transmembrane domains of the human nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Sci. Rep. 1, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Hanson M. A., Cherezov V., Griffith M. T., Roth C. B., Jaakola V.-P., Chien E. Y., Velasquez J., Kuhn P., and Stevens R. C. (2008) A specific cholesterol binding site Is established by the 2.8-Å structure of the human β-adrenergic receptor. Structure 16, 897–905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Fantini J., and Barrantes F. J. (2013) How cholesterol interacts with membrane proteins: an exploration of cholesterol-binding sites including CRAC, CARC, and tilted domains. Front. Physiol. 4, 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sodickson D. L., and Bean B. P. (1996) GABA(B) receptor-activated inwardly rectifying potassium current in dissociated hippocampal CA3 neurons. J. Neurosci. 16, 6374–6385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Vaithianathan T., Narayanan D., Asuncion-Chin M. T., Jeyakumar L. H., Liu J., Fleischer S., Jaggar J. H., and Dopico A. M. (2010) Subtype identification and functional characterization of ryanodine receptors in rat cerebral artery myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 299, C264-C278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Shouffani A., and Kanner B. I. (1990) Cholesterol is required for the reconstruction of the sodium- and chloride-coupled, γ-aminobutyric acid transporter from rat brain. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 6002–6008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kanjhan R., Coulson E. J., Adams D. J., and Bellingham M. C. (2005) Tertiapin-Q blocks recombinant and native large conductance K+ channels in a use-dependent manner. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 314, 1353–1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Rosenhouse-Dantsker A., Logothetis D. E., and Levitan I. (2011) Cholesterol sensitivity of Kir2.1 is controlled by a belt of residues around the cytosolic pore. Biophys. J. 100, 381–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Leal-Pinto E., Gómez-Llorente Y., Sundaram S., Tang Q.-Y., Ivanova-Nikolova T., Mahajan R., Baki L., Zhang Z., Chavez J., Ubarretxena-Belandia I., and Logothetis D. E. (2010) Gating of a G protein-sensitive mammalian Kir3.1 prokaryotic kir channel chimera in planar lipid bilayers. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 39790–39800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Aleksandrov A., Velimirovic B., and Clapham D. E. (1996) Inward rectification of the IRKI K+ channel reconstituted in lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 70, 2680–2687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Santiago J., Guzmàn G. R., Rojas L. V., Marti R., Asmar-Rovira G. A., Santana L. F., McNamee M., and Lasalde-Dominicci J. A. (2001) Probing the effects of membrane cholesterol in the Torpedo californica acetylcholine receptor and the novel lipid-exposed mutation alpha C418W in Xenopus oocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 46523–46532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Sui J. L., Petit-Jacques J., and Logothetis D. E. (1998) Activation of the atrial KACh channel by the βγ subunits of G proteins or intracellular Na+ ions depends on the presence of phosphatidylinositol phosphates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 1307–1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Morris G. M., Goodsell D. S., Halliday R. S., Huey R., Hart W. E., Belew R. K., and Olson A. J. (1998) Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J. Comput. Chem. 19, 1639-1662 [Google Scholar]