Abstract

Although ventricular arrhythmia remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, available antiarrhythmic drugs have limited efficacy. Disappointing progress in the development of novel, clinically relevant antiarrhythmic agents may partly be attributed to discrepancies between humans and animal models used in preclinical testing. However, such differences are at present difficult to predict, requiring improved understanding of arrhythmia mechanisms across species. To this end, we presently review interspecies similarities and differences in fundamental cardiomyocyte electrophysiology and current understanding of the mechanisms underlying the generation of afterdepolarizations and reentry. We specifically highlight patent shortcomings in small rodents to reproduce cellular and tissue-level arrhythmia substrate believed to be critical in human ventricle. Despite greater ease of translation from larger animal models, discrepancies remain and interpretation can be complicated by incomplete knowledge of human ventricular physiology due to low availability of explanted tissue. We therefore point to the benefits of mathematical modeling as a translational bridge to understanding and treating human arrhythmia.

Keywords: arrhythmia, species, cardiomyocyte, electrophysiology

Burden of Arrhythmia and the Role of Animal Models in Preclinical Therapeutic Testing

Cardiac arrhythmias such as ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation remain leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the Western world. Yet, most of the patients who die from sudden cardiac death do not meet criteria for defibrillator implantation,1 and available antiarrhythmic drugs have limited efficacy. Indeed, the failure of major clinical trials has been a significant discouragement to antiarrhythmic drug development efforts over the past 15 years.2 In part, these failures have been attributed to discrepancies between the experimental models used in preclinical development with human outcomes.3,4 Perhaps, most importantly, the electrophysiologic bases for these failures are challenging to predict from our basic understanding of the differences among commonly used models and species for preclinical drug screening.5 Thus, development of novel treatments urgently requires improved understanding of arrhythmia mechanisms across species, including an awareness of limitations in existing data.6 Here, we review known similarities and differences in fundamental electrophysiology of common model species and discuss how these characteristics are likely to affect the utility of each species for understanding and targeting certain types of arrhythmia. We particularly focus on ventricular currents and cellular mechanisms, but also treat atrial differences where appropriate, and point to the benefits of mathematical modeling as a translational bridge to understanding and treating human arrhythmia.

Conditions for generating cardiac arrhythmia

In all cases, cardiac arrhythmias are complex electrophysiologic behaviors that represent the breakdown of coordinated electrical activity among millions to billions of cardiac cells, each of which has the ability to be independently electrically activated. To distill the mechanisms capable of eliciting these behaviors, it is common to view arrhythmia generation as a process requiring 2 components: (1) a triggering event, such as a spontaneous (ectopic) or reentrant ventricular activation, and (2) a vulnerable tissue substrate into which the event can propagate. Differences in fundamental electrophysiology provide the basis for the susceptibility and characteristics of both components across species, and we begin with a discussion of these differences as they have been described for major model species, including the mouse, guinea pig, rabbit, and dog.

Species Differences in Cardiomyocyte Electrophysiology

The action potential (AP) of the ventricular cardiomyocyte is controlled by a remarkably fine balance of transmembrane ion fluxes. For the purpose of characterizing species differences in these fluxes, it is useful to separate them into the major inward and outward currents they represent.

In all species, the ventricular AP is initiated by the opening of voltage-gated Na+ channels, which carry the fast component of sodium current (INa). The resulting rapid AP upstroke triggers the opening of L-type Ca2+ channels (LTCCs), and the L-type Ca2+ current (ICaL) carries a Ca2+ influx that elicits further Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) via type 2 ryanodine receptors (RyRs). Ca2+ from both sources goes on to participate in myofilament activation, and during relaxation, a portion approximately equal to ICaL influx is extruded from the cell by the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger (NCX). Because each Ca2+ is exchanged for 3 Na+, NCX-mediated Ca2+ extrusion carries a positive current (forward-mode INaCa). This current importantly modulates the trajectory of the AP in late systole and the stability of resting potential during diastolic SR Ca2+ release events. Together, these 3 currents (INa, ICaL, and INaCa) provide the bulk of inward-going charge in virtually all cardiac cell types, and in combination with smaller contributions from other depolarizing currents (eg, T-type calcium current, late sodium current, funny current, and reverse mode Na+/K+ ATPase activity, among others), they provide one arm of the current ensemble that shapes all cardiac APs in mammals.

The other arm, of course, is provided by the repolarizing currents, which are dominated by voltage-activated potassium channels. It is the differential molecular identities and expression of these channels that confer a large portion of the species specificity present in cardiac electrophysiology, and interaction of their complex kinetics with ICaL and INaCa provides all cardiac cells with rich electrophysiologic dynamics that have yielded many counterintuitive findings and surprises over more than half a century of study. For the purpose of this review, we will describe these currents with a view to highlighting those most important for determining species specificity in normal and arrhythmogenic electrical behaviors.

Molecular and functional differences in major depolarizing currents

The molecular constituents of all 3 major inward currents are thought to be relatively consistent across species. However, meaningful functional differences have been established, particularly for the calcium transporters, the largest of which occur for NCX. The exchanger was first isolated from the canine heart by Philipson et al.7 They subsequently cloned the first NCX isoform (NCX1),8 which is recognized as the dominant cardiac form in mammals.9 Although it is not clear how much NCX1 protein expression varies between species, it is clear that exchanger activity differs substantially, and the pattern of activity across species generally reflects the degree to which sarcolemmal calcium fluxes support contractile requirements. At steady state, calcium efflux via NCX is approximately equal to the influx via ICaL. In the mouse and rat, this amounts to a relatively paltry 7%10 of the total calcium cycled during each beat, with the vast remainder being released from and resequestered into the SR. In nondiseased larger mammals, including rabbits and humans, the NCX contribution to calcium clearance is roughly 4-fold higher at 28% to 29% of total. In approximately equal parts, the reduced contribution for sarcolemmal calcium fluxes in rats results from (1) 3- to 4-fold higher SR calcium ATPase (SERCA2) activity,10,11 which favors SR calcium reuptake over NCX extrusion during diastole, and (2) fundamentally reduced NCX activity in the rat.12 Lesser NCX1 expression may partially explain this reduction, but in vivo, an important additional contribution is made by markedly higher intracellular [Na+] in rats and mice, which diminishes the thermodynamic driving force for Ca2+ extrusion.13,14 It is also possible that alterations in exchanger kinetics accompany differential regulation and expression of NCX1 splice variants across species, but these possibilities remain poorly explored. As we discuss later, the overall shift from sarcolemmal calcium sources toward SR-dependent calcium handling has allowed mice and rats to be relatively sensitive model species for SR-dependent arrhythmia phenotypes.

Peak ICaL is slightly reduced in rats compared with larger mammals,11 and in part, this is due to lower channel expression, particularly compared with guinea pig.10 ICaL activation in rats is negatively shifted compared with rabbits15 and guinea pigs,16 and this combines with slightly more positive inactivation to produce a marked increase in window current.15 Similar steady-state properties are observed when calcium is replaced by monovalent charge carriers, and the intrinsic kinetics of inactivation and recovery from inactivation are also slower in rat compared with rabbit.15 Because these observations were generally made under conditions in which SR calcium release had little opportunity to contribute to LTCC inactivation, they suggest that a range of properties independent of differences in calcium handling promote greater LTCC activity in rats than mammals with longer APs. Thus, given the same AP waveform, rat ICaL will be larger and longer.15 In vivo, this partially compensates for the much shorter rat AP and thereby better maintains LTCC-mediated Ca2+ influx.15,17 The molecular bases for these effects are not fully clear, and it is thought that the high sequence homology in critical regions for the major isoforms of both the alpha (α1C) and beta (β2a) LTCC subunits leaves little room for intrinsic differences in gating and permeation.15 It remains possible that differential expression of lesser β subunits or other accessory modulators may be important, but such effects are yet to be established.

Surprisingly, few data are available to systematically describe functional differences in INa (or late INa) across species.18 In large part, this is because INa remains very difficult to measure in cardiac cells, where its magnitude and kinetics under physiologic conditions strain voltage control in microelectrode preparations. Original studies defining cardiac INa and its pharmacology were performed in rabbit Purkinje fibers, which have several structural characteristics that allow for reliable measurement.19,20 However, modern microelectrode approaches in isolated myocytes still necessitate reducing the current by decreasing the extracellular Na+ concentration, temperature, or channel availability through partial pharmacologic blockade.21,22 All of these strategies meaningfully alter current magnitude or kinetics, and it has therefore been very difficult to compare results between studies and groups. At this time, we are unaware of any study that has systematically assessed differences in intrinsic ventricular sodium current across species. In contrast, the molecular basis of INa has been studied in a number of different species. Although Nav1.5 is the dominant alpha subunit in all cases, nontrivial and variable expression of other isoforms has been observed across species,23,24 and a number of studies have observed roles for these lesser (tetrodotoxin [TTX]-sensitive) isoforms in cardiac INa.25–27 In addition, a wide variety of accessory proteins, including β subunits, scaffolding proteins, and signaling enzymes, may contribute species-dependent effects on INa function, primarily by altering kinetics and trafficking.28–30 For all of these reasons, it seems likely that some systematic species differences in the functional characteristics of cardiac INa (and probably also late INa) exist; however, to our knowledge, none have been clearly reported to date.

Molecular and functional differences in repolarizing currents

The ensemble of K+ currents contributing to repolarization is relatively large, and varying expression of the different K+ currents is the primary explanation for major species differences in cardiac electrophysiology (Figure 1). To simplify our perspective with respect to these species differences, we separate the major K+ currents into 2 groups: (1) those that develop rapidly during the AP (several to 10s of ms) and (2) those that develop slowly (50-100s of ms). This framework is subtly different to conventional nomenclature, which describes cardiac repolarization in terms of (1) the transient outward currents (Ito) and (2) the delayed rectifier currents (IK).31,32 This distinction in convention is important for our purpose because it is more tailored to differentiating among species. For example, in the context of brief APs of mouse and rat myocytes, repolarization proceeds so rapidly that channel species which conduct current after 50 ms will rarely be recruited, even if they are expressed and measurable in conventional square pulse protocols. In this way, the repolarization characteristics in these ubiquitous model species are determined more by differences in the activation kinetics of the repolarizing currents (even among the rapidly activating currents) than by the inactivation kinetics that are conventionally used to separate and classify them. As we discuss below, for several of the rapidly activating currents, the details of these activation kinetics remain somewhat mysterious and they are likely to be critical for shaping and maintaining the stability of repolarization in lower species and perhaps also atrial myocytes of larger species.33

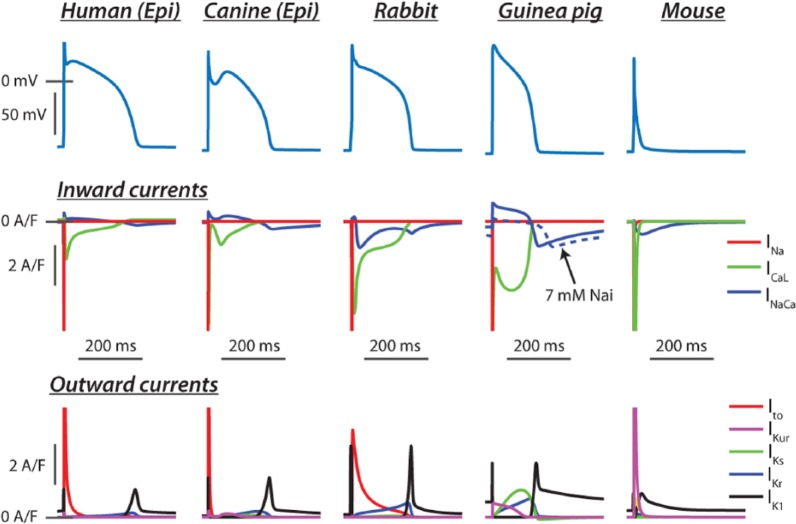

Figure 1.

Computational models represent the most concise, precise, and simple means of storing current information of myocyte electrophysiology. They also present the most simple means of comparing dynamic characteristics between species or those resulting from disease. Human: the left ventricular epicardial model of Grandi et al,34 which has been widely used by others.35,36 The relatively fast and large transient outward current is a characteristic of epicardial myocytes, and humans exhibit more subtle expression of the delayed rectifiers than other larger mammals. In particular, the rapidly activating delayed rectifier dominates over the slowly activating form, which has important implications for repolarization reserve. Canine: epicardial model from Hund and Rudy37 (see also the work by Benson et al38 and Panthee et al39), showing the pronounced Ito,f expression in these cells, which is responsible for the characteristic peak and dome action potential (AP) of this cell type and alters time courses of both ICaL and sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release. Rabbit: the rabbit model of Shannon et al40 (see also the work by Restrepo et al41) was one of the first to accurately reflect large mammal excitation-contraction coupling. Like humans, rabbits rely more heavily on IKr for late repolarization, and this has made them a popular model for studying long QT–associated arrhythmia mechanisms. Guinea pig: Luo and Rudy developed the first biophysically detailed models of ventricular myocyte electrophysiology. These models have been continually revised, and here, we show output of the Faber-Rudy42 model published in 2007. Note the high expression of all currents, and particularly IKs, which makes a major contribution to the stability of the phase 2 plateau. Inward (reverse mode) INaCa is only substantial in this model at high intracellular Na (15 mM), and normal [Na]i is ~7 mM. Mouse: the detailed mouse model of Morotti et al43 (see also the work by Gray et al44 and Schilling et al45) showing how high expression of both Ito,f and IKur overwhelms all inward currents in these cells and thereby markedly abbreviates the AP. This eliminates almost all opportunities for activation of IKs and IKr, both of which are included in the model.

Rapidly developing repolarizing currents

A number of rapidly activating currents contribute to initial repolarization from the AP overshoot and counteract the developing ICaL early in the AP of large mammals. In the mouse and rat, these currents are generally much larger and responsible for all but terminal repolarization of the AP. This species dependence is pronounced and key for permitting the much higher heart rates in mice and rats. Interestingly, these currents have also been shown to exhibit remarkable variability among mammals with longer APs, and the reasons for this variability in terms of whole organ function are still not entirely clear.

In many but not all species, the transient outward current (Ito) dominates the early contribution to repolarization. This current was initially described as the combination of 2 components, one of which (Ito2) responded to intracellular calcium and was shown to be chloride-selective.46,47 This current is detectable and nontrivial in humans,48 rabbits,49 dogs,50,51 and cats,52 but it has not been systematically compared across species. It appears to be more highly expressed in atrial tissue, where it is distinct from the Ca2+-dependent K+ currents.51 In most cases, the role of this current in ventricular myocytes is not regarded to be large, but it remains less well studied than the major K+ conductances. The larger 4-aminopyridine (4-AP)–sensitive component of Ito (Ito1) is K+-selective and much better studied (see reviews of Niwa and Nerbonne53 and Patel and Campbell54). This current can itself be decomposed into 2 components that differ in their rates of inactivation and recovery from inactivation and exhibit strong transmural variation. It is common for these 2 K+-specific components to be summed and referred to simply as Ito, and there are clear species differences in this compound K+-selective current following a pattern of expression where mouse ~ rat > dog > rabbit ~ human > guinea pig. Total murine Ito is approximately 3- to 4-fold larger than rabbit,55 whereas guinea pig Ito is generally undetectable.56–59 Importantly, these differences in the compound current are averaged across regions as well as over the 2 kinetic components. Differences across species in how total Ito and the kinetic subtypes are expressed through the ventricular wall also underlie important characteristics of organ-level electrophysiology54,60 and contraction.61,62 We focus on the defining characteristics of these 2 components and key aspects of species specificity, as discussed below.

The fast component (Ito,fast or Ito,f) is distinguished by its very rapid recovery from inactivation (τ, 20-50 ms), but also inactivates with a time constant of ~10 ms (50-80 ms in room temperature recordings), and is therefore often separated from other components by these decay kinetics.63,64 The molecular basis of this current is now thought to involve both homomultimerization and heteromultimerization of Kv4.2/4.3 pore-forming alpha subunits.53,65 These pores may be regulated by a number of accessory subunits, including the K channel–interacting proteins (KChIPs), MinK-related peptides (MiRPs), Kvβ 1-3 family proteins,53 and di-aminopeptidyl transferase-like protein 6 (DPP632). Functionally, high expression of Ito,f in the epicardium relative to endocardium underlies a large portion the transmural Ito gradient in most species, and in the dog, this gradient is very large and completely due to region-specific expression of Ito,f.54

The slow component of Ito (Ito,slow or Ito,s) inactivates 5- to 8-fold more slowly than Ito,f and is defined for its much slower recovery from inactivation (τ, 1 s), which can have important implications for the frequency dependence of repolarization. Kv1.4 is the dominant alpha subunit, and it generally exhibits an opposite transmural gradient to Ito,f (endocardium > epicardium). The rabbit is a noteworthy exception where it provides the bulk of total Ito throughout the heart and is expressed at higher levels in the epicardium presumably to maintain the overall transmural gradient in Ito.66 It remains unclear whether there are any important regulatory subunits for this current,32 but it is at least known to be regulated by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII).55

The final major rapidly activating outward current is the ultrarapidly activating delayed rectifier (IKur), which has been known by a variety of other names (IK,slow, IKsus) as its existence has been established by different methods and in different species and regions of the heart.31 This current is prominent in the atria of large mammals51,67 and throughout the hearts of mice and rats,64,68–70 where it makes a major contribution to the more rapid repolarization and shaping the triangular AP waveforms in these cells. It is distinguished from the transient outward currents by markedly slower inactivation, and for this reason, deactivation is probably the dominant process terminating IKur during repolarization in vivo. In part, this is because the cells in which IKur is strongly expressed also repolarize relatively rapidly (Figure 1). IKur in mice was originally known as IK,slow, and it has now been shown that there are 2 components with differing activation kinetics (IK,slow1/IKur and IK,slow2).71 The more rapidly activating and inactivating component is virtually identical to IKur observed in other species and tissues and is carried by Kv1.5. C-type inactivation of this channel is cooperative and importantly regulated by β-subunit interaction with the C-terminal domain.72 For this reason, in vivo inactivation is generally thought to be considerably faster than is observed in heterologous expression of alpha subunit alone. The more slowly activating IK,slow2 exhibits differing pharmacology and is sensitive to millimolar tetraethylammonium, but not low-concentration (µM) 4-AP, and appears to be encoded by Kv2.1. Depending on temperature and the method used to separate these currents, it is likely that this more slowly activating component often contributes to a large proportion of the pedestal current, which is often named the steady-state voltage-dependent current (Iss).33 The similar inactivation characteristics but differing activation kinetics of the various rapidly activating currents can give the overall current ensemble differing decay kinetics depending on the relative expression of the components and due to temperature.33 This can be exaggerated by differences in β-subunit expression, which is important for both Kv1.5 inactivation73 and Kv2.1 activation.74 Together, these characteristics make kinetically based separation of these currents very challenging.33 Finally, it should be noted that another rapidly activating and slowly inactivating current (IKp) has been described in guinea pig75,76 but is probably identical to IKur.31,77

Slowly developing repolarizing currents

The remaining delayed rectifier currents, which are known as the rapidly activating (IKr) and slowly activating (IKs) forms, exhibit much slower current development. As described below, the role of these currents in rats and mice remains somewhat controversial, but under normal circumstances, it is unlikely that they make more than a minor contribution to repolarization in these species. In contrast, important differences exist for the balance of IKr and IKs among mammals with longer APs, where they determine the trajectory and duration of the phase 2/3 plateau.78 As the delayed rectifiers slowly push repolarization out of the ICaL activation range, the voltage-independent inward rectifier (IK1) is also recruited to drive terminal repolarization in ventricles of all species and in most other types of myocyte in the heart. This current also exhibits differing expression across species, which modifies both the trajectory of late repolarization and the stability of resting potential.

Among these slowly developing currents, the species dependence of the delayed rectifiers has particular importance for repolarization reserve and susceptibility to long QT (LQT)–associated arrhythmias such as torsades de pointes. Because IKr is also now recognized as a critical target for understanding the cardiotoxic outcomes of many drugs, the question of which species provides the best foundation for assessing delayed rectifier block has been brought strongly into focus over the past 10 years.

IKr is functionally unique among cardiac currents in that its contribution to repolarization results largely from channels that are recovering from inactivation, rather than proceeding in a canonical activation to inactivation sequence. This behavior is due to the very rapid form of C-type inactivation of hERG tetramers (human ether-a-go-go-related gene), which greatly outstrips their more moderate activation kinetics.73 In this way, hERG channels accumulate in the inactivated conformations at the AP peak and early plateau, and as potential returns toward rest, they recover through the open state before deactivating, often with multiple slower kinetic components.79 These characteristics contrast with IKs, for which the KvLQT1 (KCNQ1) pore activates and deactivates very slowly (τact, 1 s; τdeact, 100-300 ms79,80) and exhibits only very slight inactivation, which is completely eliminated on coassembly with minK (KCNE1) β subunits.81 These differentiating kinetics have a number of implications for species differences, but 2 of the most important are as follows. (1) the kinetics of IKs cause it to accumulate in or near5,82 activation at higher heart rates or during prolonged depolarization. This allows it to provide a reserve of outward current that can be recruited with diminution of other outward currents (most notably IKr) and also underlies its contribution to steep restitution of AP duration in species exhibiting an AP plateau. These roles have very important implications for pharmacologic characterization in different species. (2) In myocytes with brief APs, the window-like activation characteristics of IKr allow it to make a small contribution to repolarization when hERG is expressed. This contrasts with IKs, for which activation kinetics are too slow to contribute to repolarization in species and tissues exhibiting shorter APs, at least for as long as repolarization remains stable.

As mentioned above, there remains some debate surrounding the role of these currents in mice and rats because murine knockout of KCNQ1/KCNE183–85 causes exaggerated rate-dependent and adrenergic slowing of repolarization. In larger mammals, these changes are indicative of reduced repolarization reserve. However, these animals exhibit little change in AP characteristics and minimally detectable IKs under normal conditions. One interpretation of these results is that the IKs in small rodents can only be unmasked during adrenergic modulation, which both prolongs the murine AP secondary to exaggerated Ca2+ cycling86 and is well known to increase IKs.87 E-4031-sensitive hERG currents can be detected in mice, but hERG knockout does not elicit measurable changes to the electrocardiogram or arrhythmia susceptibility in vivo.88 Together, these findings support the general perspective that the delayed rectifiers play only very minor roles in mice, and probably also rats.

There are many established differences in both expression and kinetics of the delayed rectifiers across the larger mammals exhibiting long APs. Of greatest importance for our discussion is the role that the balance of IKr and IKs plays in defining the susceptibility of these species to AP prolongation and LQT-associated arrhythmia. Differences in this balance are most strongly observed and clinically relevant under conditions straining repolarization. In species with robust IKs, particularly guinea pig (Figure 1) and also dog,79 inhibition of IKr causes voltage-dependent recruitment of IKs, thereby resisting further AP and QT prolongation. Species with less pronounced IKs, including humans and, to a somewhat lesser extent, rabbits,78 exhibit higher sensitivity to IKr blockade. This characteristic is thought to be crucial for human susceptibility to QT prolongation and torsades de pointes, particularly during hERG blockade.82 The greater similarity between rabbits and humans in this respect is one major reason that the rabbit has become an important model for understanding the mechanisms and clinical manifestations of both drug-induced and congenital LQT syndrome.89–92 Although a full treatment of clinical and preclinical implications of different LQT models is beyond the scope of this review, we direct the reader to other excellent recent reviews.78,91

The voltage-independent K+ current, also known as the K+ inward rectifier or IK1, plays a major role in terminal repolarization of the AP and is the dominant stabilizer of resting potential in cardiac myocytes. To provide this stabilization, IK1 conductance needs to be very large at potentials approaching rest, but exhibits pronounced inward rectification such that channel conductance becomes very small positive to −10 mV.93 This rectification results from field-induced block of the channel pore (formed by Kir2.1 and possibly Kir2.2/3) by intracellular Mg2+ and more prominently polyamines.93,94 This effect is physiologically critical because it allows phases 1 and 2 of the AP to be largely immune from the repolarizing influence of the IK1 channel population, which would otherwise be very large at positive potentials and therefore completely eliminate the ventricular AP plateau in larger mammals. It is important to note that the differences in rectification do not determine the existence or absence of plateau among species, but simply that rectification prevents IK1 from hastening early repolarization in all cardiac cells. In addition, IK1 conductance is positively regulated by extracellular [K+] in the physiologic range, meaning that changes in extracellular [K+] influence resting potential and terminal repolarization in a nonlinear way that depends on a balance between this change in IK1 conductance and an opposing change in Nernst equilibrium for K+. Because baseline IK1 conductance and plasma [K+] vary among species, tissues, and pathologic state, the changes in these cellular properties are clinically relevant and nontrivial.

Differences in IK1 expression are prominent across regions of the heart. In particular, IK1 is virtually absent in the sinus node, and in nearly all species, the atria exhibit 2- to 3-fold lower IK1 than the ventricles.95–97 The rectification properties are also exaggerated in the ventricles96,98 and may represent differences in polyamine concentration, their interaction with the channel,94 or differing contributions from the various Kir2 isoforms.95,99 Characterization of species differences in early investigations was less systematic, but differences in current expression and rectification were observed. Guinea pig IK1 is relatively large and may also exhibit greater contribution of Mg2+-dependent rectification compared with cat and rabbit,100 but not sheep.95 Among species that are commonly used to model human physiology, both the rabbit78 and dog79 exhibit larger ventricular IK1 expression than humans, whereas rectification properties are relatively similar. Both species exhibit 2- to 3-fold larger currents within the range relevant to repolarization, and this appears to extend to the inward portion of the voltage range.79 The mouse is unique among species in that the tissue distribution of IK1 appears to be the opposite of larger species. Murine IK1 is at least as large in the atria compared with ventricles, with the left atrium having slightly higher expression at potentials negative to EK.101 In sum, these characteristics may leave human myocytes more susceptible to diastolic depolarization accompanying events such as spontaneous calcium release and slightly reduce the rate of terminal repolarization compared with other large mammals (Figure 1).

Species-Dependent Mechanisms Underlying Early Afterdepolarizations

Early afterdepolarizations (EADs) are oscillations in membrane potential occurring prior to terminal repolarization of the AP, which can occur either during the plateau region of the AP (phase 2) or during late repolarization (phase 3). Classically, these events are thought to occur anytime the balance of currents contributing to the plateau is disrupted and AP duration is prolonged, ie, when outward currents are reduced and/or inward currents are increased.102 As we describe below, this perspective remains informative because it indicates the origin of the dysfunction, but it does not offer a precise account of the mechanisms governing EAD generation and may therefore have limited ability to guide effective therapeutic interventions. A more detailed account takes into consideration how the trajectory of repolarization interacts with the kinetics of the contributing currents to determine stable and unstable regimes of cardiac repolarization. Because AP shape varies markedly, it is perhaps not surprising that fundamentally different mechanisms underlie EAD generation across species.

EADs in large mammals

As detailed above, ventricular cardiomyocytes from large species including humans, dogs, sheep, guinea pigs, and rabbits exhibit prolonged APs with clear phase 2/3 plateau. Early afterdepolarizations observed in these species are generally initiated late in the plateau, and early studies of EAD mechanisms established that no matter which current is the proximal source destabilizing repolarization, reactivation of the LTCC pool provides most of the current during the EAD upstroke.103,104 Over subsequent years, the range of stimuli and currents capable of destabilizing repolarization in these species has been extended as different experimental maneuvers have been tested. Aside from ICaL, the most important destabilizing currents are forward-mode INaCa resulting from exaggerated or discoordinated SR calcium release105–108 (Figure 2A) and increased late sodium current.109,110 Similarly, maneuvers that reduce K+ channel conductance and repolarization reserve have been known to elicit EADs for some time.79,103,105 Together, these observations contributed to the concise and satisfying interpretation that EADs are a straightforward extension of reduced repolarization reserve and excessive AP prolongation. Although this perspective is useful in that EADs are correlated with both AP prolongation and reduced repolarization reserve, there are several exceptions to this premise that required further explanation. Two of the most compelling are as follows: (1) AP duration can be markedly increased without resulting in EADs, whereas AP triangulation (independent of AP duration) strongly predicts EAD generation,111–113 and (2) brief APs with ample repolarization reserve and little or no plateau, as occurring in rodents or the atria of large mammals, still exhibit EADs during a range of challenges.86,114–118

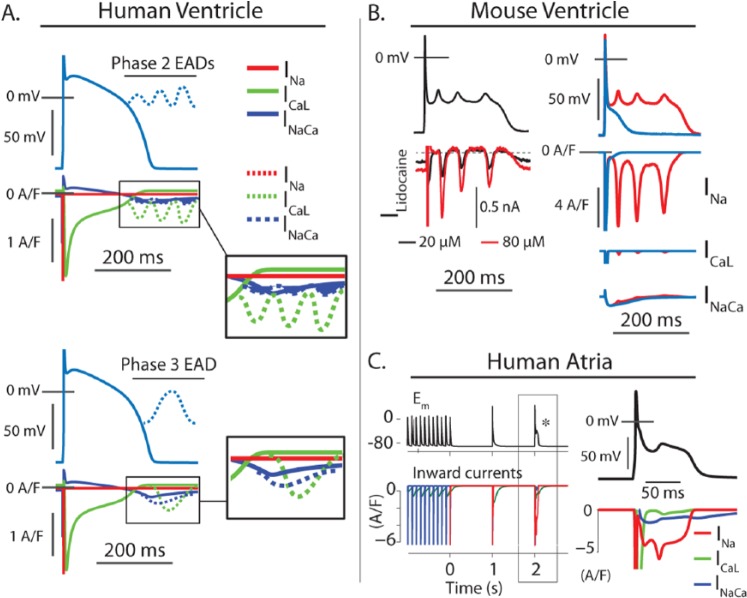

Figure 2.

Early afterdepolarization (EAD) mechanisms differ across species and tissues. (A) Schematic representation of EAD mechanisms in large mammal ventricular myocytes. The long action potential plateau observed in ventricular myocytes from humans and other large mammals promotes EADs that initiate within the activation range of ICaL. As a result, the broad range of maneuvers or defects that can destabilize repolarization in these cells converge at ICaL reactivation, which carries most of the inward current in all cases. In some cases, discoordinated intracellular calcium release (systolic calcium waves) can act as the initiating factor and generate sufficient INaCa to drive these reactivation events. Because INaCa is favored at negative potentials, these types of events are more likely to generate an EAD during terminal repolarization and still ICaL carries most of the current during the EAD upstroke. (B) Murine EADs involve fundamentally different mechanisms. At left, an action potential clamp experiment showing the lidocaine-sensitive current during an EAD waveform is recorded in a mouse ventricular myocyte. At these concentrations, lidocaine binds primarily to inactivated Na+ channels, and this current indicates a reactivating component of INa. Because this component is sensitive to the trajectory of repolarization, it represents nonequilibrium dynamics rather than window-range reactivation. At right, the same EAD waveform is imposed on a mouse ventricular myocyte model, which shows that compared with the other major inward currents, INa is by far the greatest contributor to EADs in mice. (C) EAD mechanisms associated with reinitiation of atrial fibrillation (AF) in a human atrial myocyte model. Rapid pacing and acetylcholine administration can be used to simulate atrial fibrillation in atria of large mammals (AF115). When the pacing is stopped to simulate termination of AF, spontaneous EADs occur at sinus rates, as has been observed in canine atria.119 These events result from INa reactivation very similar to that occurring in the mouse ventricle. This may be important in certain specific contexts of human atrial disease.

To define the conditions for EAD initiation, a quantitative approach is more precisely required. Tran et al120 provided a first formal description of these conditions using a model of the guinea pig AP. In this model, the transition between stable and unstable repolarization is determined by the rates at which reactivating ICaL can grow and deactivating or inactivating IK declines when membrane potential returns toward rest. If the conditions favor faster growth in ICaL, as occurs when repolarization slows below 0 mV (where ICaL recovers much more rapidly and IK deactivates), EADs ensue.121 This dynamic explanation has also been studied in rabbit cells and models122 and succinctly clarifies several characteristics of EADs in larger mammals: (1) AP prolongation does not elicit EADs if it occurs at positive potentials because ICaL recovery is limited and slow in that potential range, and (2) AP triangulation is highly predictive of EADs and associated arrhythmias because it lengthens the time spent in potential ranges where ICaL can recover and grow rapidly while IK deactivates.112,113 Finally, this explanation of EAD mechanisms constitutes a form of dynamic chaos that is also capable of explaining the irregular nature of EAD appearance under some conditions and which was otherwise attributed to stochasticity in channel gating.122,123 As such, this conceptual and quantitative framework provides our most complete account of EAD mechanisms in APs from large mammals and reconciles contradictory aspects of prior conceptual models. These mechanisms extend to EADs in myocytes from smaller mammals and other more rapidly repolarizing cardiac cell types, but these cells also house additional EAD dynamics that are not readily observed in large mammalian myocytes.

EADs in mice and large mammalian atria

As described above, the rapidly repolarizing potassium currents, Ito and IKur, are highly expressed in the mouse and rat, and this affords those species much more rapid repolarization. IKur is also expressed in atrial tissue of larger mammals and thereby results in a more triangular atrial AP with a much more negative phase 2/3 plateau compared with ventricular tissue. We have recently shown that the rapid repolarization of mouse ventricle fundamentally alters EAD dynamics86 because the mouse myocyte repolarizes through the ICaL activation range within 5 to 10 ms. This simultaneously prevents ICaL from entering the unstable regime accessible in larger mammals and facilitates a regime in which INa is capable of reactivating (Figure 2B). The limited time spent at positive potentials largely prevents accumulation of sodium channels in the slowly recovering states of intermediate and deep inactivation and deposits the membrane potential in a range where a very small portion of channels can rapidly recover from fast inactivation and undergo reactivation events. Although this interaction between INa and IK has not yet been assessed in quantitative detail, this nonequilibrium reactivation of INa appears to be the dominant mechanism of EAD initiation in mice (Figure 2B). Once initiated, murine EADs may reach potentials that recruit further reactivation of ICaL and exhibit dynamics much more similar to large mammals.86 Interestingly, mouse-like EAD dynamics have also been observed in canine atrial preparations when repolarization is accelerated via dual pharmacologic challenge by acetylcholine and β-adrenergic agonists or by autonomic nerve stimulation.115,116,119 Computational analyses involving a human atrial model suggest that INa reactivation is the initiating current in these EADs, secondary to prolongation of the low phase 3 plateau, just as in the mouse (Figure 2C).114 With this similarity noted, it is important to reinforce that the atria of humans and other large mammals do not normally repolarize on the same timescale as the mouse. Because the atrial AP of larger mammals (including humans) is much longer (~200 vs 50 ms in mouse), it is also likely that these dynamics are relatively specific to the particular conditions used in these studies. Thus, the repolarization trajectory of large mammalian atria can allow a range of EAD regimes including both ICaL and nonequilibrium INa reactivation, but ventricle-like ICaL-IK dynamics are more probable in most pathologic circumstances.

Finally, despite unique EAD mechanisms present in mice, this species is now often used to examine arrhythmia mechanisms and interventions.124 Most often, the sensitivity of murine EADs to various maneuvers is then interpreted in the context of the established dynamics for large mammals.118 This is likely to incorrectly emphasize the role of ICaL in the murine mechanism and to contribute to the poor translation of findings across levels of preclinical and clinical studies.

Ca2+ Waves and Delayed Afterdepolarizations

Spontaneous RyR Ca2+ release, which can be visualized as a propagating Ca2+ wave, produces a phasic depolarization of the membrane potential as released Ca2+ is extruded by NCX. As noted above, Ca2+ waves occurring late in the APs of large species can elicit EADs, which may subsequently recruit LTCCs. However, in both small and large species, spontaneous Ca2+ waves can occur at resting membrane potential due to spontaneous RyR openings, with resulting NCX current eliciting delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs). When of sufficient magnitude, DADs can trigger sufficient Na+ channel opening to elicit a spontaneous AP. Although the basic mechanisms of Ca2+ wave and DAD generation are shared across species, susceptibility to these events is dependent on species-specific parameters, including RyR sensitivity, cellular Ca2+ flux balance, cellular ultrastructure, and heart rate (diastolic interval).

RyR opening is steeply dependent on cytosolic [Ca2+], although the precise nature of this relationship is also determined by other factors including [Mg2+], pH, and SR luminal [Ca2+].125 In bilayer studies mimicking physiologic conditions, most reports indicate that half maximal activation of RyRs occurs within a range of 2 to 10 µM cytosolic [Ca2+] (reviewed in a study by Bers126). However, there appear to be species-dependent differences as recent studies have demonstrated that RyRs from rat hearts exhibit substantially lower Ca2+ sensitivity than those from human, sheep, and dog.127–129 This finding is not generally supported by studies examining Ca2+ spark probability in cardiomyocytes; indeed, Satoh et al130 observed higher spark rates in rat than rabbit cardiomyocytes. This discrepancy is likely due to differences in luminal [Ca2+], on which Ca2+ spark frequency has a near-exponential dependence.131 Following termination of electrical pacing, rabbit cells exhibit rapid loss of SR Ca2+ due to prominent Ca2+ extrusion by NCX. In rat cells, however, SR Ca2+ reuptake by SERCA dominates over NCX function, and SR Ca2+ content is maintained.130 This high luminal SR Ca2+ sustains high RyR open probability, despite the reported low sensitivity of the channel to cytosolic Ca2+.127,128 In agreement with this observation, unstimulated cells from rats and mice exhibit regular Ca2+ waves during conditions of Ca2+ overload, whereas in rabbit cells sparks and waves rapidly cease following cessation of electrical pacing.130,132,133 Guinea pig cardiomyocytes also exhibit a pronounced loss of SR Ca2+ content during rest, whereas ferret and human cardiomyocytes may show a slow decline or increase in releasable Ca2+.134–136 Such interspecies differences should be carefully considered when interpreting Ca2+ wave susceptibility in resting cells.

Species differences in Ca2+ wave generation are also apparent in the more physiologic context of electrical stimulation. Indeed, pacing frequency is a key regulator of RyR Ca2+ sensitivity. Although SR content is high in cardiomyocytes from small rodents, it is relatively maintained across the physiologic range of pacing frequencies.137 In contrast, SR content is lower in large species but increases with pacing rate, which is expected to augment the potential for waves. Simultaneously, there is accumulation of diastolic [Ca2+] at increasing frequency, as SERCA and NCX become unable to keep up with Ca2+ influx. Rising cytosolic Ca2+ levels increase the likelihood of waves both directly, by triggering RyR opening, and indirectly, by activating CaMKII, which phosphorylates the RyR and increases its Ca2+ sensitivity. These proarrhythmic, RyR-sensitizing effects of high heart rates are tempered somewhat by RyR “refractoriness.”126 This term refers to the fact that following each Ca2+ transient RyRs exhibit a brief period of reduced availability. Thus, at high pacing frequencies, there is less diastolic interval when RyRs are available to be activated. For this reason, it might be envisioned that animals with high heart rates such as mice have limited susceptibility to Ca2+ waves in vivo.

Species differences in SR and sarcolemmal Ca2+ fluxes have consequences not only for determining Ca2+ wave susceptibility but also for the subsequent generation of DADs. Because SERCA and NCX compete for the same pool of Ca2+, high NCX activity and/or low SERCA activity reduce SR Ca2+ content, making spontaneous Ca2+ release less likely.106,138 However, when a wave does occur in this scenario, proportionally greater released Ca2+ is extruded due to prominent NCX activity.139 Thus, in large species with robust transsarcolemmal Ca2+ cycling, larger proarrhythmic DADs are expected per unit released Ca2+. In contrast, healthy mice and rats exhibit prominent SR reuptake which more easily overloads the SR, but also draws Ca2+ away from the NCX during a wave, minimizing DAD amplitude. Such opposing effects complicate prediction of arrhythmic potential in different species and also in disease scenarios where SERCA and NCX expression are often inversely regulated.140–142

Finally, accumulating evidence indicates that the precise arrangement of dyads is an important determinant of Ca2+ wave propagation and DAD generation. In both small and large species, RyRs are localized with a regular striated appearance along z-lines (reviewed in a study by Louch et al143). Small rodents have a high density of similarly organized T tubules, meaning that a large proportion of RyRs are present in or very near dyads.144–146 Thus, when spontaneous Ca2+ release occurs, nearby NCX in the T tubules is well positioned to mediate Ca2+ extrusion during Ca2+ sparks or waves.147,148 In larger species, such as pigs and humans, T-tubule density is considerably lower.144,149 Thus, a large fraction of RyRs can be considered extradyadic or “orphaned,”146 with NCX molecules located considerably distant. In such cells, Ca2+ is expected to be quickly removed from RyR release sites in dyads and more slowly from orphaned RyRs. In agreement with this prediction, Biesmans et al147 observed a bi-exponential time course of NCX current following Ca2+ release. Based on these observations, it has been hypothesized that low T-tubule density may limit DAD generation during Ca2+ waves.150 However, the orientation of dyads should also be considered, as not all dyads are oriented transversely along z-lines. Especially in rodents, a fairly high proportion of T tubules and RyRs are positioned longitudinally (axially) along the cell, spanning sarcomeres.146,151 Mathematical modeling has predicted that RyRs in these dyads may abet Ca2+ wave propagation.152,153 In addition to interspecies considerations, changing dyadic orientation is likely important for determining arrhythmic potential in diseases, such as heart failure, where there is loss of transversely oriented dyads at z-lines but formation of longitudinally oriented dyads.145,146,151

Tissue-Level Considerations

Although we have focused this review on the cellular mechanisms that differentiate arrhythmia susceptibility among common model species, very important differences also exist at the tissue and organ levels and warrant a cursory treatment at least. These differences can be broadly classified as either structural or functional, and the manner in which they affect arrhythmogenesis results from their influence on arrhythmogenic tissue substrate or the interaction between cellular triggers of arrhythmia and that substrate. Although a number of structural (eg, tissue size and conduction system structure) and physiologic (gap junction conductance, heterogeneity in current expression, diastolic interval and restitution properties, alternans susceptibility, etc.) characteristics may contribute to these differences, we reduce the complexities to those contributing to either reentry or ectopy.

Tissue size as a limitation to reentry

The length of a propagating wave in cardiac tissue is given by the product of the conduction velocity of the wavefront and the effective refractory period (CV·ERP). In the mouse, ventricular ERP is approximately 30 ms.154 Assuming a bulk myocardial conduction velocity of 50 cm/s, this yields a wavelength of approximately 1.5 cm, which is close to the distance that the wavefront traverses during activation of an adult mouse heart. This simple calculation is commonly used to argue that the mouse heart is too small to permit sustained reentry, and both early experiments155 and more recent theoretical treatments156 helped this idea to gain general acceptance. However, experiments involving optically recorded arrhythmia then convincingly have shown that reentry is possible in the mouse heart and that reentrant vortices can be significantly smaller than the wavelengths predicted from CV and ERP during normal pacing in the same tissue (15-30 mm157). The explanation provided for this effect was that a stable circuit could be generated by dispersion of action potential duration (APD) moving from short APs at the rotor core to longer APs at more distant sites.157 This dynamic stabilization fundamentally modified arguments surrounding limits to reentry and reinforces the importance of dynamic substrates in arrhythmia. It has also been suggested that certain conditions that push cardiac tissue away from properties of a continuous medium toward a system of discrete electrical components (cells) can facilitate reentry on a much smaller scale. These behaviors have been termed microreentry and are thought to occur in conditions involving severe local tissue heterogeneity (eg, fibrosis) or markedly reduced and heterogeneous intercellular coupling as in ischemia.158

Susceptibility to dynamic functional substrates

Disregarding structural substrates, dispersion of repolarization due to ischemia or dynamic mechanisms is the most important form of arrhythmia substrate in the heart and can arise in otherwise healthy myocardium. However, the degree to which this dispersion is able to contribute to arrhythmia in vivo depends greatly on its degree, the intrinsic heart rate of the animal, and the spatial scale of the tissue, as described above. In humans and large mammals, dispersion of repolarization has long been considered an important precursor of arrhythmia in a range of congenital and acquired arrhythmias.159,160 The largest regional differences in AP duration in large mammals occur transmurally, and APD dispersion across the left ventricle (LV) wall is thought to be one of the most important sources of arrhythmogenic substrate. As such, the existence and importance of different transmural cell types to repolarization dynamics have been the focus of spirited investigation and debate, some of which probably rest on the specific characteristics of the canine wedge preparation.159,161–163 Certain characteristics of the canine wedge, particularly the existence of M cells, have received support from studies of human tissues,164,165 but a large portion of the transmural variation in underlying currents remains unknown in humans. As such, it is difficult to compare the value of large animal models in this respect. As discussed for the arguments related to reentry, the size of the mouse heart imposes some limits on the degree to which dispersion can provide sufficient substrate for initiation or maintenance of arrhythmia. However, heterogeneity in APD has also been observed in mice,154 and several investigations have shown that manipulation of repolarizing currents can exacerbate this to an extent that promotes arrhythmia.166,167 Given the very thin mouse ventricular free wall, it is probable that these heterogeneities must occur in an apicobasal rather than transmural basis to permit reentry, but we are unaware of any study that has assessed this directly.

In addition to intrinsic heterogeneity in APD, dynamic instabilities can also produce reentrant substrate. APD alternans is the best described of these behaviors and is observed as a period 2 variation in APD (short-long-short-long), which is typically induced by rapid pacing. Because this behavior involves complex interaction of sarcolemmal current carriers and the intracellular calcium machinery, it is generally studied in species with similar current ensembles as humans or at least with prominent phase 2/3 plateau.168–171 To our knowledge, no study has attempted to describe the importance of species differences in current expression or calcium handling for alternans mechanisms, although excellent reviews of general alternans mechanisms are provided elsewhere.172,173 With this in mind, we highlight 2 key aspects of these general mechanisms that are likely to be strongly influenced by known species differences: (1) destabilization of calcium handling is likely to be the proximal cause of the cellular behavior in large mammals under physiologic conditions,174,175 and (2) the ability of alternation in APD to create substrate for reentry depends on the alternans becoming spatially discordant or out of phase in adjacent regions of tissue.173 Given the marked differences in calcium handling (described above), APD restitution,154 heart size (described above), and intrinsic heart rate, it is very likely that the small rodents exhibit differing mechanisms of cellular alternans and differing susceptibility to alternans-dependent arrhythmia than larger species. Even among larger mammals, smaller differences in these characteristics are likely to set up important distinctions that muddy translation from preclinical to clinical studies.176

Tissue-level determinants of ectopy

In contrast to determinants of reentry, it is likely that smaller cardiac dimensions render the heart more susceptible to ectopy and premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). This property results from the pronounced effect that tissue volume has on electronic load. Xie et al177 nicely demonstrated this relationship in 1-, 2-, and 3-dimensional simulations, where the corresponding number of contiguous cells required to generate a propagating event increased from 10s to 1000s to 100 000s. No experimental study has systematically assessed species differences in the number of cells required to generate PVCs, largely because experimental approaches to estimating these quantities involve many challenges. However, separate investigations using different approaches have described approximate source-sink characteristics in rabbits178 and mice.179 Although the different approaches (local β-adrenergic stimulation in rabbit vs optogenetic stimulation in mouse) introduce additional uncertainty, the number of cells required for murine PVCs (100-2000) was markedly less than in the rabbit (~10 000 to million). As suggested by Xie et al,177 this large difference is likely to indicate a major effect of tissue geometry that had previously only been assessed by simulations. In addition, both studies observed a marked LV/right ventricle (RV) difference in the number of cells required to initiate ectopy. Ablation of the RV Purkinje network by the Lugol solution eliminated this difference in mice, but not in rabbits. In the mouse, this was taken to indicate that the Purkinje network can play an important role in determining PVC requirements, and the authors showed that the primary difference between the RV and LV was that the activating light was not able to fully penetrate the thicker LV free wall and reach the endocardial Purkinje network. Separate investigations of murine ectopy support this role for Purkinje cells.180,181 The explanation of interventricular differences in the rabbit requires further explanation but may simply be due to the thinner RV wall, which more closely approximated a 2-dimensional current sink in their experiments. Together, these tissue-level determinants along with the increased reliance on intracellular calcium cycling in small rodents make them quite a sensitive model for arrhythmias associated with spontaneous SR calcium release and DADs.

Summary and Recommendations

In general, the small size of the mouse and rat hearts combines with their differing potassium current profiles and limits their utility for reflecting diseases of human ventricular repolarization across all levels of observation. At the cellular level, their repolarization dynamics differ enough that they are relatively poor models of general AP changes and EAD dynamics in the human ventricle. At the tissue level, they appear to lack the size and specific patterns of heterogeneity thought to underlie important mechanisms of substrate generation in humans and other large mammals. However, these small rodent models may be more applicable to repolarization dynamics in the human atria, where their AP dynamics can more reasonably be regarded as exaggerated versions of the human atrial myocyte. In addition, the heightened dependence of small rodent myocytes on intracellular calcium cycling and the small size of mouse and rat hearts make them relatively sensitive models of spontaneous calcium release at the cellular level and calcium-driven focal arrhythmia in tissue.

Large mammals remain the first choice for addressing questions of specific tissue dynamics in arrhythmias of all types, and many large animal models of specific arrhythmogenic conditions have been created. Because expression of the delayed rectifiers is relatively similar between nondiseased rabbits (as well as heart failure dogs) and humans, these models have been very instructive for understanding the roles of IKr and IKs in determining repolarization reserve and susceptibility to LQTs arrhythmia. Similarly, the balance of sarcolemmal and intracellular calcium fluxes in rabbits, dogs, sheep, and pigs is relatively similar to humans, thus allowing them to be relatively good models of the interaction between calcium-sensitive transporters (particularly NCX and ICaL) and calcium-insensitive modulators of the AP. As such, these species remain the best models for studying these subtleties in detail, particularly at the cellular level and in the context of LQT-associated drug screening. Of course, the specifics of regional heterogeneities in current expression described above must be carefully considered when addressing questions specific to arrhythmogenic substrate. Due to limited tissue availability, human-specific regional heterogeneity remains a work in progress. As these data become available, the models appropriate for specific clinically oriented questions will become clear.

Finally, the wealth of information that has been collected to describe these differences and similarities across species is naturally, efficiently, and usefully stored in the mathematical models that have been developed to represent them. These models constitute the most systematic means at our disposal for interpreting results across species. Thus, we recommend continued interaction among modelers, experimentalists, and clinicians to define the following: (1) the shortcomings of existing models across species, (2) where a lack of reliable experimental data precludes quality model development, and (3) the utility and limits of modeling for linking arrhythmia dynamics observed in experiments with the broad range of criteria and therapeutics used to classify and treat patients.

Footnotes

Peer review:Six peer reviewers contributed to the peer review report. Reviewers’ reports totaled 766 words, excluding any confidential comments to the academic editor.

Funding:The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (consolidator grant, WEL) under grant agreement no. 647714. Additional support was provided by the SUURPh initiative of the Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research, the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority, Anders Jahres Fund for the Promotion of Science, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo University Hospital Ullevål, and the University of Oslo.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: AGE and WEL drafted and revised the article text. AGE performed mathematical simulations and prepared the figures.

References

- 1. Myerburg RJ, Mitrani R, Interian A, Castellanos A. Interpretation of outcomes of antiarrhythmic clinical trials: design features and population impact. Circulation. 1998;97:1514–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Waring MJ, Arrowsmith J, Leach AR, et al. An analysis of the attrition of drug candidates from four major pharmaceutical companies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:475–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hamlin RL. Animal models of ventricular arrhythmias. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;113:276–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sanguinetti MC, Bennett PB. Antiarrhythmic drug target choices and screening. Circ Res. 2003;93:491–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dorian P, Newman D. Rate dependence of the effect of antiarrhythmic drugs delaying cardiac repolarization: an overview. Europace. 2000;2:277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cox B. CHAPTER 1. Ion channel drug discovery: a historical perspective. In: Cox B, Gosling M, eds. Ion Channel Drug Discovery. Cambridge, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2014:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Philipson KD, Longoni S, Ward R. Purification of the cardiac Na+-Ca2+ exchange protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;945:298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nicoll DA, Longoni S, Philipson KD. Molecular cloning and functional expression of the cardiac sarcolemmal Na(+) -Ca2+ exchanger. Science. 1990;250:562–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Philipson KD, Nicoll DA. Sodium-calcium exchange: a molecular perspective. Annu Rev Physiol. 2000;62:111–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bers DM. Excitation-Contraction Coupling and Cardiac Contractile Force. Vol 2 Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Su Z, Li F, Spitzer KW, Yao A, Ritter M, Barry WH. Comparison of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase function in human, dog, rabbit, and mouse ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:761–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sham JS, Hatem SN, Morad M. Species differences in the activity of the Na(+) -Ca2+ exchanger in mammalian cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 1995;488:623–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lewalle A, Niederer SA, Smith NP. Species-dependent adaptation of the cardiac Na+/K+ pump kinetics to the intracellular Na+ concentration. J Physiol. 2014;592:5355–5371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shattock MJ, Bers DM., Rat vs. rabbit ventricle: Ca flux and intracellular Na assessed by ion-selective microelectrodes. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:C813–C822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yuan W, Ginsburg KS, Bers DM. Comparison of sarcolemmal calcium channel current in rabbit and rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1996;493:733–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hadley RW, Lederer WJ. Intramembrane charge movement in guinea-pig and rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1989;415:601–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Terracciano CM, MacLeod KT. Measurements of Ca2+ entry and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ content during the cardiac cycle in guinea pig and rat ventricular myocytes. Biophys J. 1997;72:1319–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Noble D, Noble PJ. Late sodium current in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease: consequences of sodium-calcium overload. Heart. 2006;92:iv1–iv5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bean BP, Cohen CJ, Tsien RW. Lidocaine block of cardiac sodium channels. J Gen Physiol. 1983;81:613–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Colatsky JJ, Tsien RW. Sodium channels in rabbit cardiac Purkinje fibres. Nature. 1979;278:265–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bondarenko VE, et al. Computer model of action potential of mouse ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1378–H1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sakakibara Y, Furukawa T, Singer DH, et al. Sodium current in isolated human ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:H1301–H1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Blechschmidt S, Haufe V, Benndorf K, Zimmer T. Voltage-gated Na+ channel transcript patterns in the mammalian heart are species-dependent. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;98:309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zimmer T, Haufe V, Blechschmidt S. Voltage-gated sodium channels in the mammalian heart. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2014;2014:449–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lines GT, Sande JB, Louch WE, Mørk HK, Grøttum P, Sejersted OM. Contribution of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger to rapid Ca2+ release in cardiomyocytes. Biophys J. 2006;91:779–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Radwański PB, Brunello L, Veeraraghavan R, et al. Neuronal Na+ channel blockade suppresses arrhythmogenic diastolic Ca2+ release. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;106:143–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Torres NS, Larbig R, Rock A, Goldhaber JI, Bridge JH. Na+ currents are required for efficient excitation-contraction coupling in rabbit ventricular myocytes: a possible contribution of neuronal Na+ channels. J Physiol. 2010;588:4249–4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Abriel H. Cardiac sodium channel Na(v)1.5 and interacting proteins: physiology and pathophysiology. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:2–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abriel H, Kass RS. Regulation of the voltage-gated cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 by interacting proteins. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15:35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Herren AW, Bers DM, Grandi E. Post-translational modifications of the cardiac Na channel: contribution of CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation to acquired arrhythmias. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305:H431–H445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nerbonne JM. Molecular basis of functional voltage-gated K+ channel diversity in the mammalian myocardium. J Physiol. 2000;525:285–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nerbonne JM. Molecular basis of functional myocardial potassium channel diversity. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2016;8:257–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brouillette J, Clark RB, Giles WR, Fiset C. Functional properties of K+ currents in adult mouse ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 2004;559:777–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Grandi E, Pasqualini FS, Bers DM. A novel computational model of the human ventricular action potential and Ca transient. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:112–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Augustin CM, Neic A, Liebmann M, et al. Anatomically accurate high resolution modeling of human whole heart electromechanics: a strongly scalable algebraic multigrid solver method for nonlinear deformation. J Comput Phys. 2016;15:622–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Holzem KM, Gomez JF, Glukhov AV, et al. Reduced response to IKr blockade and altered hERG1a/1b stoichiometry in human heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;96:82–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hund TJ, Rudy Y. Rate dependence and regulation of action potential and calcium transient in a canine cardiac ventricular cell model. Circulation. 2004;110:3168–3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Benson AP, Aslanidi OV, Zhang H, Holden AV. The canine virtual ventricular wall: a platform for dissecting pharmacological effects on propagation and arrthyhmogenesis. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;96:187–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Panthee N, Okada J, Washio T, et al. Tailor-made heart simulation predicts the effect of cardiac resynchronization therapy in a canine model of heart failure. Med Image Anal. 2016;31:46–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shannon TR, Wang F, Puglisi J, Weber C, Bers DM. A mathematical treatment of integrated Ca dynamics within the ventricular myocyte. Biophys J. 2004;87:3351–3371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Restrepo JG, Weiss JN, Karma A. Calsequestrin-mediated mechanism for cellular calcium transient alternans. Biophys J. 2008;95:3767–3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Faber GM, Silva J, Livshitz L, Rudy Y. Kinetic properties of the cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel and its role in myocyte electrophysiology: a theoretical investigation. Biophys J. 2007;92:1522–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Morotti S, Edwards AG, McCulloch AD, Bers DM, Grandi E. A novel computational model of mouse myocyte electrophysiology to assess the synergy between Na+ loading and CaMKII. J Physiol. 2014;592:1181–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gray B, Bagnall RD, Lam L, et al. A novel heterozygous mutation in cardiac calsequestrin causes autosomal dominant catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:1652–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schilling JM, Horikawa YT, Zemljic-Harpf AE, et al. Electrophysiology and metabolism of caveolin-3-overexpressing mice. Basic Res Cardiol. 2016;111:28–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kenyon JL, Gibbons WR. 4-Aminopyridine and the early outward current of sheep cardiac Purkinje fibers. J Gen Physiol. 1979;73:139–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kenyon JL, Gibbons WR. Influence of chloride, potassium, and tetraethylammonium on the early outward current of sheep cardiac Purkinje fibers. J Gen Physiol. 1979;73:117–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang Z, Fermini B, Nattel S. Delayed rectifier outward current and repolarization in human atrial myocytes. Circ Res. 1993;73:276–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang Z, Fermini B, Feng J, Nattel S, et al. Role of chloride currents in repolarizing rabbit atrial myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H1992–H2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tseng GN, Hoffman BF. Two components of transient outward current in canine ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1989;64:633–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yue L, Feng J, Li GR, Nattel S, et al. Transient outward and delayed rectifier currents in canine atrium: properties and role of isolation methods. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H2157–H2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Furukawa T, Myerburg RJ, Furukawa N, Bassett AL, Kimura S. Differences in transient outward currents of feline endocardial and epicardial myocytes. Circ Res. 1990;67:1287–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Niwa N, Nerbonne JM. Molecular determinants of cardiac transient outward potassium current (I(to)) expression and regulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:12–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Patel SP, Campbell DL. Transient outward potassium current, “Ito,” phenotypes in the mammalian left ventricle: underlying molecular, cellular and biophysical mechanisms. J Physiol. 2005;569:7–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wagner S, Hacker E, Grandi E, et al. Ca/calmodulin kinase II differentially modulates potassium currents. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:285–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Findlay I. Is there an A-type K+ current in guinea pig ventricular myocytes? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H598–H604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sanguinetti MC, Jurkiewicz NK. Two components of cardiac delayed rectifier K+ current. Differential sensitivity to block by class III antiarrhythmic agents. J Gen Physiol. 1990;96:195–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sanguinetti MC, Jurkiewicz NK. Delayed rectifier outward K+ current is composed of two currents in guinea pig atrial cells. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:H393–H399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zicha S, Moss I, Allen B, et al. Molecular basis of species-specific expression of repolarizing K+ currents in the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1641–H1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Akar FG, Wu RC, Deschenes I, et al. Phenotypic differences in transient outward K+ current of human and canine ventricular myocytes: insights into molecular composition of ventricular Ito. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H602–H609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bassani RA, Altamirano J, Puglisi JL, Bers DM. Action potential duration determines sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ reloading in mammalian ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 2004;559:593–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dong M, Yan S, Chen Y, et al. Role of the transient outward current in regulating mechanical properties of canine ventricular myocytes. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21:697–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Guo W, Xu H, London B, Nerbonne JM. Molecular basis of transient outward K+ current diversity in mouse ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1999;521:587–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Xu H, Guo W, Nerbonne JM. Four kinetically distinct depolarization-activated K+ currents in adult mouse ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:661–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Guo W, Li H, Aimond F, et al. Role of heteromultimers in the generation of myocardial transient outward K+ currents. Circ Res. 2002;90:586–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fedida D, Giles WR. Regional variations in action potentials and transient outward current in myocytes isolated from rabbit left ventricle. J Physiol. 1991;442:191–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Li GR, Feng J, Wang Z, Fermini B, Nattel S. Adrenergic modulation of ultrarapid delayed rectifier K+ current in human atrial myocytes. Circ Res. 1996;78:903–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bou-Abboud E, Li H, Nerbonne JM. Molecular diversity of the repolarizing voltage-gated K+ currents in mouse atrial cells. J Physiol. 2000;529:345–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Boyle WA, Nerbonne JM. A novel type of depolarization-activated K+ current in isolated adult rat atrial myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:H1236–H1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Brunet S, Aimond F, Li H, et al. Heterogeneous expression of repolarizing, voltage-gated K+ currents in adult mouse ventricles. J Physiol. 2004;559:103–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Li H, Guo W, Yamada KA, Nerbonne JM. Selective elimination of I(K,slow1) in mouse ventricular myocytes expressing a dominant negative Kv1.5alpha subunit. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H319–H328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Heinemann SH, Rettig J, Graack HR, Pongs O. Functional characterization of Kv channel beta-subunits from rat brain. J Physiol. 1996;493:625–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wu W, Sanguinetti MC. Molecular basis of cardiac delayed rectifier potassium channel function and pharmacology. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2016;8:275–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Gordon E, Roepke TK, Abbott GW. Endogenous KCNE subunits govern Kv2.1 K+ channel activation kinetics in Xenopus oocyte studies. Biophys J. 2006;90:1223–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Backx PH, Marban E. Background potassium current active during the plateau of the action potential in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1993;72:890–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Yue DT, Marban E. A novel cardiac potassium channel that is active and conductive at depolarized potentials. Pflugers Arch. 1988;413:127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Nerbonne JM, et al. Genetic manipulation of cardiac K(+) channel function in mice: what have we learned, and where do we go from here? Circ Res. 2001;89:944–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Baczkó I, Jost N, Virág L, Bősze Z4, Varró A. Rabbit models as tools for preclinical cardiac electrophysiological safety testing: importance of repolarization reserve. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2016;121:157–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Jost N, Virág L, Comtois P, et al. Ionic mechanisms limiting cardiac repolarization reserve in humans compared to dogs. J Physiol. 2013;591:4189–4206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Virág L, Iost N, Opincariu M, et al. The slow component of the delayed rectifier potassium current in undiseased human ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49:790–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Tristani-Firouzi M, Sanguinetti MC. Voltage-dependent inactivation of the human K+ channel KvLQT1 is eliminated by association with minimal K+ channel (minK) subunits. J Physiol. 1998;510:37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]