Abstract

Progression of hepatic fibrosis requires sustained inflammation leading to activation of stellate cells into a fibrogenic and proliferative cell type, whereas regression is associated with stellate cell apoptosis. The contribution of hepatic macrophages to these events has been largely overlooked. However, a study in this issue of the JCI demonstrates that macrophages play pivotal but divergent roles, favoring ECM accumulation during ongoing injury but enhancing matrix degradation during recovery. These findings underscore the potential importance of hepatic macrophages in regulating both stellate cell biology and ECM degradation during regression of hepatic fibrosis.

Kupffer cells, the resident macrophage population of the liver, have in recent years lost their leading position in the pecking order of cell types known to contribute to hepatic injury and repair. Long recognized for their activity in liver inflammation, they had been increasingly overlooked while a stellate cell–centric view of hepatic fibrosis had replaced the earlier focus on macrophages (Figure 1). Symbolic of this demotion, a biannual meeting initially convened as the International Kupffer Cell Symposium changed its name in 1990 to the International Symposium on Cells of the Hepatic Sinusoid (1). This evolution has been understandable because recent studies have established the activated hepatic stellate cell and its myofibroblast counterpart as the major sources of ECM in both experimental and human liver disease (2). As a result, a comprehensive picture of hepatic stellate cell activation in liver injury has emerged, resulting in exciting new prospects for targeting a range of growth factors, receptors, and intracellular mediators in the treatment of hepatic fibrosis (3).

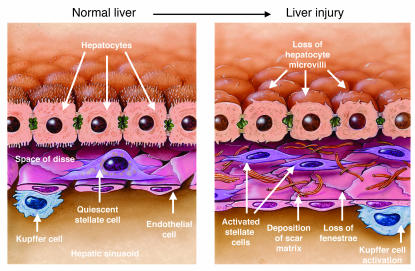

Figure 1.

Cellular events in hepatic fibrosis. As fibrosis develops in response to liver injury, stellate cell activation leads to accumulation of scar matrix. This in turn contributes to the loss of hepatocyte microvilli and endothelial fenestrae, which results in the deterioration of hepatic function. Kupffer cell (macrophage) activation contributes to the activation of stellate cells. Figure modified with permission from The Journal of Biological Chemistry (24).

The paper by Duffield and colleagues in this issue of the JCI (4), however, firmly reestablishes the hepatic macrophage as a central determinant of the liver’s response to injury and repair. The study is built upon 2 important concepts. First, macrophages have more than one pathway of activation and response, depending on the specific stimulus and biologic context; indeed, divergence of macrophage responses has been recognized for many years (5, 6) but has only recently been placed in a biologically coherent context that defines pro- and anti-inflammatory phenotypes. Proinflammatory actions of macrophages include antigen presentation, T cell activation, and cytokine and protease release, among others (7). However, anti-inflammatory actions have been increasingly appreciated, particularly those induced by IL-4, including induction of immune tolerance (8), innate immunity (9), and T cell differentiation (7, 10).

A second, more recently developed concept addresses the behavior of hepatic stellate cells in the resolution of liver injury and fibrosis. Whereas initial interest in stellate cell biology focused on the cells’ activation and fibrogenic properties during progressive liver injury, more recent efforts have explored both their fate as liver injury resolves and the mechanisms underlying persistence of fibrosis in sustained liver injury. This is a vital area of inquiry since clarification of mechanisms by which the liver naturally restores its architecture might be exploited in developing antifibrotic therapies for patients with chronic liver disease. During regression of experimental liver fibrosis, activated stellate cells undergo programmed cell death associated with loss of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase–1 (TIMP-1) expression (11). Because TIMP-1 not only enhances stellate cell survival but also antagonizes matrix degradation, the loss of TIMP-1–expressing stellate cells is thought to unleash latent matrix-degrading activity, leading to the breakdown of scar matrix and the reconstitution of normal hepatic architecture. When liver injury persists, TIMP-1 levels remain high, and progressive cross-linking of collagen may render the accumulating matrix relatively insoluble to proteases (12, 13). This concept is reinforced by studies demonstrating attenuation of fibrosis when TIMP-1 is inhibited (14). Significant gaps in this paradigm have persisted, however, including the source(s) and identity of salutary proteases in fibrosis resolution and the role of other cellular elements, including not only hepatic macrophages, but also sinusoidal endothelium.

Macrophage depletion in mice identifies novel roles in regulating hepatic fibrosis

Duffield and colleagues have generated a transgenic mouse model in which macrophages can be selectively depleted in a regulated manner (4). Expression of a human version of a diptheria toxin receptor driven by the promoter of a myeloid antigen (CD11b) renders transgenic macrophages (called CD11b-DTR cells) susceptible to killing by administration of diptheria toxin. Careful control experiments confirmed that susceptibility is macrophage specific and does not affect other cell lineages. Next the investigators compared the impact of macrophage depletion on hepatic fibrosis between a murine model in which macrophages were depleted during the progression of fibrosis by the administration of diptheria toxin after 12 weeks of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) intoxication but before the final dose of CCl4, and another in which macrophages were depleted by diphtheria toxin administration only 3 days after the last dose of toxin was administered, at which time recovery from CCl4-mediated fibrosis had begun. These modest differences between the progression and recovery models of hepatic fibrosis in the timing of macrophage depletion (approximately 10 days) — specifically, the occurrence of depletion either before or after the final dose of CCl4 — yielded completely opposite effects on hepatic matrix accumulation. Depletion of macrophages while injury was progressing had an antifibrotic effect whereas depletion during early recovery led to sustained accumulation of matrix.

Divergent phenotypes of hepatic macrophages – one cell type or two?

These results are fascinating, and they raise some important but unanswered questions regarding the underlying mechanisms. Are the same macrophages responsible for promoting matrix accumulation during progression and preventing it during recovery through phenotype switching, or are different subsets of macrophages recruited during this brief interval? While the former seems more likely and is consistent with evolving concepts (7, 15), an alternative explanation also supported by this (4) and much earlier studies (16) is the recruitment and differentiation of bone marrow–derived monocytes into hepatic macrophages. In fact, it is uncertain whether all these recruited monocytes become classic Kupffer cells or remain phenotypically distinguishable as a novel subpopulation. Regardless, if phenotypic conversion of the same cells accounts for this divergent behavior in progression versus recovery, what are the signals driving this switch? One approach to clarifying these questions would be to isolate CD11b-DTR–expressing cells by flow cytometry at different intervals during progression and recovery (without diptheria toxin administration) to analyze their transcriptional profile by microarray and to perform functional studies. This approach could be used in mice chimeric for bone marrow cells so that the phenotype of CD11b-DTR–expressing cells from liver could be distinguished from those derived from bone marrow.

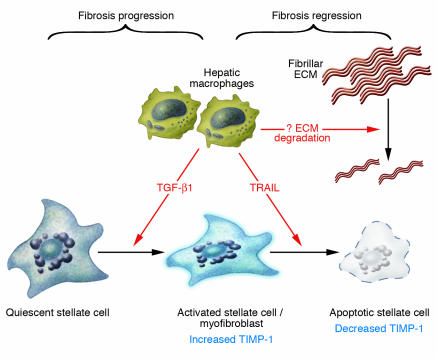

How do the divergent macrophage phenotypes present during fibrosis progression versus recovery affect matrix production and degradation? In particular, are the effects of macrophage depletion mediated largely through their impact on activated stellate cells and/or myofibroblasts? During fibrosis progression, it is believed that macrophages are likely to promote activation of stellate cells through release of paracrine factors, including TGF-β1, since this phenomenon has been demonstrated in culture (17, 18) (Figure 2). In contrast, the simultaneous loss of macrophages (termed scar-associated macrophages by Duffield et al.; ref. 4) and activated stellate cells during recovery suggests that macrophages could also provoke apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells by the expression of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (known as TRAIL) and other apoptotic stimuli, as recently reported (19). Thus, the biphasic nature of macrophages could yield divergent effects on stellate cells, promoting their activation during progression and apoptosis during recovery. One potential regulator of this duality could be the cytokine TNF-α or its downstream signaling mediator NF-κB, since delicate temporal regulation of NF-κB signaling in hepatocytes can elicit profound and divergent effects on apoptosis and growth (20).

Figure 2.

The double-edged sword of hepatic macrophage activity in hepatic fibrosis progression versus recovery. The findings by Duffield et al. (4) in this issue of the JCI suggest that hepatic macrophages may induce divergent effects on liver fibrosis by promoting stellate cell activation in the face of continued injury and fibrosis; and stellate cell apoptosis during recovery associated with fibrosis regression as injury subsides. Evidence from other studies implicates TGF-β1 as one potential paracrine stimulator of stellate cell activation by macrophages, while TRAIL may mediate stellate cell apoptosis during fibrosis regression associated with recovery. Apoptosis associated with the loss of TIMP-1 may unmask latent matrix protease activity released by either macrophages, stellate cells, or other cell types. It is not certain if the same macrophages account for the divergent activities of this cell type or whether different macrophage subsets mediate these opposing pathways.

Do hepatic macrophages degrade ECM during fibrosis regression?

A more compelling question is whether macrophages directly promote matrix degradation during resolution of liver fibrosis through production of matrix-degrading proteases or by stimulating either the release or activation of proteases by other cell types, including stellate cells. Identifying macrophages as the elusive source of enzymes that degrade the fibrillar interstitial (i.e., scar) matrix during fibrosis resolution would represent a major advance, although the primary substrate for the hepatic macrophage’s major known metalloproteinase, MMP-9, is basement-membrane collagen, not fibrillar collagen (21). Still, more careful characterization of recovery-associated macrophages could yield some surprises, including macrophage release of additional proteases or the existence of a more broad substrate specificity of MMP-9 that also includes fibrillar collagens; moreover, recent data suggest that activated stellate cells may also express MMP-9 (22). Finally, degradation of fibrillar ECM by recovery-associated macrophages may yield an altered extracellular milieu that no longer supports survival of activated stellate cells, since breakdown of interstitial collagen represents loss of an important survival signal (23).

In summary, the exciting study by Duffield and colleagues (4) offers a new perspective in the study of hepatic injury and repair by resurrecting the prominence of hepatic macrophages, illustrating their dual phenotype in fibrosis progression and recovery, and highlighting their importance in regulating hepatic matrix degradation.

Footnotes

See the related article beginning on page 56.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: CCl4, carbon tetra-chloride; TIMP-1, tissue inhibitor of metalloprotein-ase–1; TRAIL, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand.

Conflict of interest: The author has declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Wisse, E., Knook, D.L., and McCuskey, R.S. 1990. Fifth international symposium on cells of the hepatic sinusoid. The Kupffer Cell Foundation. Tuscon, Arizona, USA. 558 pp.

- 2.Pinzani M, Rombouts K. Liver fibrosis: from the bench to clinical targets. Dig. Liver Dis. 2004;36:231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrosis and therapeutic implications. Nature Clinical Practice in Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2004;1:98–105. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duffield JS, et al. Selective depletion of macrophages reveals distinct, opposing roles during liver injury and repair. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:56–65. doi:10.1172/JCI200523928. doi: 10.1172/JCI22675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decker K. Biologically active products of stimulated liver macrophages (Kupffer cells) Eur. J. Biochem. 1990;192:245–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wake K, et al. Cell biology and kinetics of Kupffer cells in the liver. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1989;118:173–229. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60875-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goerdt S, Orfanos CE. Other functions, other genes: alternative activation of antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 1999;10:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knolle PA, Gerken G. Local control of the immune response in the liver. Immunol. Rev. 2000;174:21–34. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.017408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vazquez-Torres A, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 dependence of innate and adaptive immunity to Salmonella: importance of the Kupffer cell network. J. Immunol. 2004;172:6202–6208. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun Z, et al. Hepatic allograft-derived Kupffer cells regulate T cell response in rats. Liver. Transpl. 2003;9:489–497. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iredale JP, et al. Mechanisms of spontaneous resolution of rat liver fibrosis. Hepatic stellate cell apoptosis and reduced hepatic expression of metalloproteinase inhibitors. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;102:538–549. doi: 10.1172/JCI1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Issa R, et al. Spontaneous recovery from micronodular cirrhosis: evidence for incomplete resolution associated with matrix cross-linking. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1795–1808. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy FR, et al. Inhibition of apoptosis of activated hepatic stellate cells by tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 is mediated via effects on matrix metalloproteinase inhibition: implications for reversibility of liver fibrosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:11069–11076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parsons CJ, et al. Antifibrotic effects of a tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 antibody on established liver fibrosis in rats. Hepatology. 2004;40:1106–1115. doi: 10.1002/hep.20425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duffield JS. The inflammatory macrophage: a story of Jekyll and Hyde. Clin. Sci. 2003;104:27–38. doi: 10.1042/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gale RP, Sparkes RS, Golde DW. Bone marrow origin of hepatic macrophages (Kupffer cells) in humans. Science. 1978;201:937–938. doi: 10.1126/science.356266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuoka M, Tsukamoto H. Stimulation of hepatic lipocyte collagen production by Kupffer cell-derived transforming growth factor beta: implication for a pathogenetic role in alcoholic liver fibrogenesis. Hepatology. 1990;11:599–605. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840110412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman SL, Arthur MJ. Activation of cultured rat hepatic lipocytes by Kupffer cell conditioned medium. Direct enhancement of matrix synthesis and stimulation of cell proliferation via induction of platelet-derived growth factor receptors. J. Clin. Invest. 1989;84:1780–1785. doi: 10.1172/JCI114362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischer R, Cariers A, Reinehr R, Haussinger D. Caspase 9-dependent killing of hepatic stellate cells by activated Kupffer cells. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:845–861. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pikarsky E, et al. NF-kappaB functions as a tumour promoter in inflammation-associated cancer. Nature. 2004;431:461–466. doi: 10.1038/nature02924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knittel T, et al. Expression patterns of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells of rat liver: regulation by TNF-alpha and TGF-beta1. J. Hepatol. 1999;30:48–60. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han YP, et al. Essential role of matrix metalloproteinases in interleukin-1-induced myofibroblastic activation of hepatic stellate cell in collagen. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:4820–4828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310999200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Issa R, et al. Mutation in collagen-1 that confers resistance to the action of collagenase results in failure of recovery from CCl4-induced liver fibrosis, persistence of activated hepatic stellate cells, and diminished hepatocyte regeneration. FASEB J. 2003;17:47–49. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0494fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedman SL. Molecular regulation of hepatic fibrosis, an integrated cellular response to tissue injury. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:2247–2250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]