Abstract

Recent advancements in sequencing technology allowed researchers to better address the patterns and mechanisms involved in microbial environmental adaptation at large spatial scales. Here we investigated the genomic basis of adaptation to climate at the continental scale in Suillus brevipes, an ectomycorrhizal fungus symbiotically associated with the roots of pine trees. We used genomic data from 55 individuals in seven locations across North America to perform genome scans to detect signatures of positive selection and assess whether temperature and precipitation were associated with genetic differentiation. We found that S. brevipes exhibited overall strong population differentiation, with potential admixture in Canadian populations. This species also displayed genomic signatures of positive selection as well as genomic sites significantly associated with distinct climatic regimes and abiotic environmental parameters. These genomic regions included genes involved in transmembrane transport of substances and helicase activity potentially involved in cold stress response. Our study sheds light on large-scale environmental adaptation in fungi by identifying putative adaptive genes and providing a framework to further investigate the genetic basis of fungal adaptation.

Keywords: Adaptation, population genomics, mycorrhizal fungi, Suillus brevipes

Introduction

The environment in which organisms live plays an important role in shaping the distribution of genetic variability within and between populations across time and space. Environmental adaptation in natural populations leaves genomic signatures of positive selection that shed light on the origins and maintenance of genetic variation within and between populations (Dobzhansky 1948, Novembre & Di Rienzo 2009). Natural selection affects the levels of genetic variability and can lead to selective sweeps, where sites linked to a selected mutation show reduced within-population variability (Nielsen 2005). One way to studying environmental adaptation is to detect genomic regions under positive selection. This approach can be done by using large-scale single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) datasets, detecting statistical outliers and characterizing genes under selection. Another method to studying environmental adaptation is ecological association, in which one detects allele frequencies that exhibit significant statistical association with environmental variables that are used as proxies for natural selection (Frichot et al. 2013, Frichot & François 2015). Genome scans for environmental adaptation produce lists of genetic polymorphisms potentially involved in local adaptation that can be compared to genomic regions under positive selection and provide a better assessment of environmental adaptation.

Studies on the genomics of environmental adaptation are very often conducted in biological systems with pre-defined ecotypes that are recognized based on obvious morphological traits, ecological preferences, or both (e.g. Jones et al. 2012, Laurent et al. 2015, Nachman et al. 2003, Schweizer et al. 2016). Such studies aim to document the genomic basis of ecotypic differences and are based on a priori ideas on relevant population units and environmental parameters that might cause genetic divergence. For most taxa, including the vast majority of microbiological diversity, a priori information on ecotypic variation is scarce if available at all, making studies of environmental adaptation more challenging to implement. Fungi in particular offer little obvious phenotypic variation potentially linked to fitness differences at the population level and there are only a few documented cases of fungal local adaptation relating to environmental differences, such as heavy metal contaminated soils (Colpaert et al. 2011), genetically different plant pathogenic hosts (e.g. Salvaudon et al. 2008, Enjalbert et al. 2005) and thermal clines (Mboup et al. 2012). Recent ecological genomic approaches have revealed additional evidence of fungal adaptation related to subtle environmental variation and allowed candidate genomic regions involved in environmental adaptation to be identified. Such regions provide indirect evidence for fungal adaptation to environmental conditions (an approach coined ‘reverse ecology’; Li et al. 2008) and can be the basis for developing tests aimed at revealing the mechanisms responsible for the process of fungal adaptation. Relevant examples include ecotypic variation in the saprobe Neurospora crassa linked to temperature gradients (Ellison et al. 2011), adaptation to cheese environment in the genus Penicillium (Ropars et al. 2015), host specificity in the wheat pathogen Zymoseptoria graminicola (Stukenbrock et al. 2011) and adaptation to soil chemistry in the ectomycorrhizal fungus Suillus brevipes (Branco et al. 2015). The latter study focused on the same species that we examine here and documented two recently diverged and isolated populations in an obligate fungal symbiont of pine from coastal and montane California. The two populations showed very limited genetic differentiation, but a gene homologous to Nha-1, a membrane Na+/H+ exchanger involved in salt tolerance in plants and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Nass et al. 1997, Apse et al. 1999) differed between the two populations and showed evidence of positive selection. This report was the first to find salt as a potential driver for ectomycorrhizal fungal population differentiation, even though soil chemistry is long known to affect fungal physiology and growth (Smith & Read 2010).

Here we investigated the genomic basis of adaptation to climate at the continental scale in S. brevipes by expanding the genomic dataset studied of Branco et al. (2015). Adding to the previously documented coastal and montane California populations, we sequenced the genomes of individuals from five additional sites in Canada (two locations were sampled), Colorado, Minnesota and Wyoming (United States of America), totaling 55 S. brevipes individuals. This expanded sample encompassed a wide range of environments and enabled us to test whether S. brevipes genomes display signatures of adaptation to distinct climatic regimes. Specifically, we asked whether there is evidence for local adaptation in this species across North America by detecting selective sweeps across the S. brevipes genome and assessing whether large-scale climatic parameters such as temperature and precipitation are associated with genetic differentiation. We hypothesized that this wind-dispersed species would show both strong population structure across the continent and a pattern of climatic adaptation, with genomic signatures of positive selection in regions correlated to temperature and/or precipitation and involved in environmental response. We found strong population differentiation across North America as well as significant genotype-climate associations in genomic regions under strong positive selection. These regions included genes involved in transmembrane transport and helicase activity that are known from other systems to be involve with cold stress response.

Materials and methods

Isolate collection, culturing and DNA extraction and sequencing

We collected fruitbodies of Suillus brevipes and cultured dikaryotic individuals from them from seven pine forests selected from the western and northern range of the species. Specifically we sampled two sites in California (USA), two sites in Alberta (Canada), and one site, each, in Wyoming, Colorado and Minnesota (USA, Fig. 1). A total of 55 dikaryotic S. brevipes individuals were included in our study. This sample contained 28 dikaryotic S. brevipes cultures from California that we had been previously sequenced and reported on Branco et al. (2015), and 27 new individuals from the other parts of range. We sequenced the whole genomes of the new cultures with pair-end 100bp Illumina technology following the protocol described in Branco et al. (2015). We combined these new data with the sequences generated for the S. brevipes populations from coastal and montane California studied in Branco et al. (2015) to produce a total sample of 55 S. brevipes individuals. We used four individuals as outgroups, one S. luteus individual and three individuals of Suillus sp. (S106, S108, S110), a species closely related to S. pseudobrevipes (Nguyen et al, in press). Suillus luteus reads were obtained from the reference genome (http://genome.jgi.doe.gov/Suilu1/Suilu1.home.html) and we sequenced the Suillus sp. (S106, S108, S110) whole genomes from fruitbodies collected in Florida and processed in the same manner as S. brevipes individuals. All details on collection sites for all individuals are summarized in Table S1. Raw reads were deposited in Short Read Archive and accession numbers can also be found in Table S1.

Figure 1.

Sampling localities of the studied Suillus brevipes populations in North America. Red - coastal California (16 ind); purple - montane California (9 individuals); yellow – Canada (Alberta), Whitecourt (5 individuals); orange – Canada (Alberta), Castle Rock (7 individuals); blue - Wyoming (7 individuals); black - Colorado (5 individuals); green - Minnesota (6 individuals).

Read filtering, mapping and variant calling

We used a Galaxy workflow to perform read filtering and mapping (Goecks et al. 2010, Blankenberg et al. 2010, Giardine et al. 2005; Supplement 1). In short, we filtered the reads using Trim Galore! 0.3.7 (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/) and additionally filtered by quality with a cut-off value of 20. Filtered paired reads were then mapped to the S. brevipes reference genome (http://genome.jgi.doe.gov/Suillus_brevipes/, assembled in 1555 scaffolds with a N50 of 159 kbp) using Bowtie 2.2.3 (Langmead & Salzberg 2012). Alignments were sorted with SAMtools 0.1.19 (Li et al. 2009) and paired with Paired Read Mate Fixer in Picard 1.129 (http://picard.sourceforge.net). Duplicates and poor alignments were removed also using Picard, as well as filtered for uniquely mapped reads. The genome alignment rate was assessed with Picard and genome coverage with SAMtools. Variant calling was performed using ANGSD 0.801 (Korneliussen et al. 2014), a program based on genotype likelihoods, the marginal probability of the sequencing data given a genotype in a particular individual for a particular site. With our moderate genome coverage data, variant calling comes associated with uncertainty that can lead to biased estimates of allele frequencies and population genetic parameters. ANGSD takes base calling, mapping and alignment errors into account, making it ideal to analyze the genomes included in this study. This software, which was developed for low and medium coverage data and diploid organisms, is equally useful for studying dikaryons.

Population structure and individuals genealogy

We used RAxML (Stamatakis 2014) to infer the S. brevipes individuals maximum-likelihood genealogy based on the full set of SNPs (using the model GTRGAMMA and 100 bootstrap replicates). Population structure was studied using principal components analysis (PCA) with ngsCovar implemented in ngsTools (Fumagalli et al. 2013) and NgsAdmix (Skotte et al. 2013), a software for assigning individuals to differentiated genetic clusters and inferring admixture of related individuals using genotype likelihood data. Analyses were performed with the number of clusters, K, ranging from two to seven and with five replicates per K value. Average likelihoods were compiled using the Evanno method (Evanno et al. 2005) to identify genetically homogeneous groups of individuals. The divergence metrics FST and Dxy were computed for the homogeneous populations only (the two California populations, Colorado and Minnesota) using ANGSD and ngsStat, respectively.

Summary statistics and linkage disequilibrium

Summary statistics and linkage disequilibrium decay were estimated for the four homogenous populations (the two California populations, Colorado and Minnesota). We computed nucleotide diversity (π), Watterson theta (θ) and Tajima's D with ANGSD (Korneliussen et al. 2014) and heterozygosity for all populations using ngsStat in ngsTools (Fumagalli et al. 2013). To assess linkage disequilibrium (LD) decay, we calculated the correlation coefficient (r2) between any two loci across the genome using genotypes. r2 was calculated using VCFTools 0.1.13 (Danecek et al. 2011) with a maximum of 5000bp between SNPs.

Association between genotypes and environmental variables

Genotype-environment associations were assessed using Latent Factor Mixed Models 1.4 (LFMM, Frichot et al. (2013)), a univariate mixed-model approach that estimates the effects of hidden factors representing background residual levels of population structure. We acquired environmental parameters for each S. brevipes homogeneous population using geo-referenced environmental layer datasets (Hijmans et al. 2005). We used a set of 19 climate variables available in BIOCLIM (Hijmans et al. 2005): annual mean temperature, mean diurnal range, isothermality, temperature seasonality, maximum temperature of warmest month, minimum temperature of coldest month, temperature annual range, mean temperature of wettest quarter, mean temperature of driest quarter, mean temperature of warmest quarter, mean temperature of coldest quarter, annual precipitation, precipitation of wettest month, precipitation of driest month, precipitation seasonality, precipitation of wettest quarter, precipitation of driest quarter, precipitation of warmest quarter, and precipitation of coldest quarter.

We normalized the environmental variables (by subtracting each value by the parameter mean and dividing this amount by the corresponding standard deviation) and performed a PCA to reduce the number of variables to be tested (hereafter envPCA). envPC1 and envPC2 explained 95% of the climate variation (envPC1: 66%; envPC2: 29%, Fig S1) and were selected as the environmental variables for LFFM analyses. These principal components depict a combination of temperature and precipitation (Table S2), with envPC1 being heavily influenced by how cold and dry the winters are (with minimum temperature of coldest month, mean temperature of coldest quarter and precipitation of coldest quarter with the highest loadings) and envPC2 roughly informing on weather heterogeneity throughout the year (with mean diurnal range, mean temperature of wettest quarter and annual precipitation with the highest loadings).

In LFMM the optimal latent factor number (K) influences the false discovery rate and should be selected based on the mean genomic inflation factor (λ), which is the median of the squared z scores divided by 0.456. Based on 5 LFMM runs, K=6 had the λ estimates closer to 1.0 for both envPC1 and envPC2. We obtained the median z scores of all five runs and re-adjusted the p-values using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction procedure and set the false discovery rate to 10% as recommended in the program manual. We selected the top 5% SNPs significantly correlated with envPC1 and envPC2 to investigate gene ontology enrichment (see below).

Genome scans for selective sweeps

We used SweeD 3.2.11 (Pavlidis et al. 2013) to search for selective sweeps. These genomic regions are defined by reduced genetic variation (with an excess of rare variants and of high frequency derived variants) around mutation sites due to strong and recent positive selection that has led to the fixation of a single allele (Nielsen 2005). SweeD implements a composite likelihood ratio (CLR) test based on the SweepFinder algorithm (Nielsen et al. 2005). The CLR uses the variation of the whole or derived site frequency spectrum of a genomic sequence to compute the ratio of the likelihood of a selective sweep at a given position to the likelihood of a null model without selective sweep. The null hypothesis relies on the site frequency spectrum (SFS) of the whole genomic sequence rather than on a standard neutral model, which makes it more robust to demographic events such as population expansions (Pavlidis et al. 2013, Nielsen et al. 2005). SweeD was run both separately for each of the populations identified using analyses of population structure to detect population-specific selective sweeps, and on all samples to detect species-wide selective sweeps. We used the empirical derived site frequency spectra of the whole genome as a background for all scaffolds, using the four outgroup individuals to orient SNPs. We considered only scaffolds where the first and last SNPs were more than 3 kb distant, and computed CLR every 1 kb. CLR values not belonging to the 95th percentile were considered as outliers. As the CLR is not designed to test if close outlier values belong to the same selective sweep, we simply defined genomic intervals affected by selective sweeps by merging consecutive outlier positions into single intervals and adding 500 bp at the flanks of each interval.

Outlier Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis

We conducted gene ontology (GO) enrichment analyses on selective sweeps and LFMM outliers using ClueGO 2.2.4, a Cytoscape plugin Java tool that extracts knowledge on putative function for large clusters of genes. We modified the default settings to include minimal number and percentage of genes for GO term/pathway selection and the minimal and maximal level for GO Tree interval as one and twelve respectively. Significance of GO terms was calculated with a two-sided hypergeometric test and p-values corrected using the Benjamini-Hochberg approach. We also identified enrichment of functional domains associated to the two environmental principal components. We used a hypergeometric test to assess differences in functional domains associated with envPC1 and envPC2. The geometric test was further applied to each domain with genetic variation regarding envPC1 and envPC2, with a total of 862 domains examined. Individual functional domains with FDR higher or equal than 0.05 were likely observed by chance after correcting for multiple comparisons.

Results

Suillus brevipes genomes

We obtained over one billion raw Illumina reads and over 900 million high-quality reads from 55 S. brevipes individual genomes, that yielded 1,495,484 high quality single nucleotide polymorphisms across the 52.7Mb genome. Polymorphism level in this species was close to 3% segregating sites. Table S1 summarizes all information on per-individual number of generated raw reads, number of high-quality reads, alignment rate and genome coverage (which varied between 21x and 110x).

Population structure, individual genealogy and summary statistics

We found distinct and clearly differentiated S. brevipes populations across North America, including the two Californian populations previously described in Branco et al. (2015). The genealogy of individuals based on the full set of SNPs (Fig. 2) showed the Canadian samples as paraphyletic and sister to all other populations, with Minnesota nested within Castle Rock and Whitecourt basal to Wyoming, Colorado and coastal and montane California.

Figure 2.

Rooted maximum-likelihood genealogy inferred from the full SNP dataset. We used one individual of S. luteus (Slu) and three individuals of Suillus sp. as outgroups (in gray). The remaining colors correspond to Fig. 1: Red - coastal California; purple - montane California; yellow – Canada (Alberta), Whitecourt; orange – Canada (Alberta), Castle Rock; blue - Wyoming; black - Colorado; green - Minnesota. * indicates bootstrap support value >90.

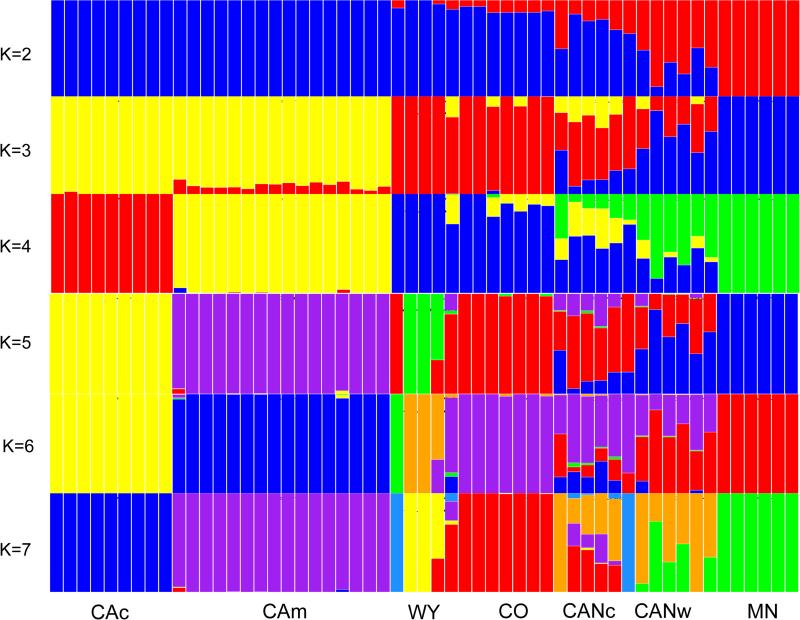

The ngsAdmix analyses were consistent across distinct K values, revealing coastal California, montane California, Colorado and Minnesota as genetically homogeneous (Fig. 3, Figure S2). Individuals from the two populations in Canada and Wyoming showed substantial membership in clusters identified in other populations suggesting potential admixture (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Estimated S. brevipes population structure as inferred by NGSAdmix. Each individual is represented by a bar partitioned into K color segments (K=2 to K=7). CAc - coastal California; CAm - montane California; CANc – Canada (Alberta), Castle Rock; CANw – Canada (Alberta), Whitecourt; CO – Colorado; MN – Minnesota; WY -Wyoming.

The SNP-based PCA also showed S. brevipes population genetic structure (Fig. 4), with the two Californian populations previously analyzed appearing as clearly differentiated but accounting for a small portion of the genomic variability encompassed in the sampled populations. Apart from Minnesota and Colorado, the remaining populations were not as clearly differentiated. Individuals from the two Canadian sites and Wyoming showed some degree of overlap in the ordination space and Canadian individuals spread over both PC1 and PC2 indicating high genetic variability.

Figure 4.

PCA of sampled S. brevipes populations with percentage of variance explained by each principal component. Colors correspond to Fig. 1: Red - coastal California; purple - montane California; yellow – Canada (Alberta), Whitecourt; orange – Canada (Alberta), Castle Rock; blue - Wyoming; black - Colorado; green - Minnesota.

California, Colorado and Minnesota populations showed similar per-base nucleotide diversity (π), Watterson theta (θ) and heterozygosity (Table 1). Linkage disequilibrium (LD) decay curves were very similar across populations (Fig. 5), showing a strong sharp decay in the first hundreds of base pairs. Such pattern indicates very small linkage blocks and therefore pervasive outcrossing in this species.

Table 1.

Average per-base nucleotide diversity (π), Watterson theta (θ) and heterozygosity across Suillus brevipes populations. CAc - California coast, CAm - California mountain, CO - Colorado, MN - Minnesota.

| Nucleotide diversity | Watterson theta | Heterozygosity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAc | 0.098 | 0.093 | 0.093 |

| CAm | 0.106 | 0.113 | 0.104 |

| CO | 0.108 | 0.110 | 0.1 |

| MN | 0.123 | 0.142 | 0.115 |

Figure 5.

Linkage disequilibrium decay in each population across the whole genome. Populations are color-coded as in Fig. 1: Red - coastal California; purple - montane California; black - Colorado; green - Minnesota.

Genomic pairwise FST revealed high levels of differentiation between populations of S. brevipes (Table 2). The California montane and coastal populations were the least differentiated (with FST CAc-CAm = 0.09), while Minnesota was the most differentiated, with FST values of 0.3 and over when compared to California and Colorado. These results are in accordance with both the phylogeny and admixture analyses.

Table 2.

Pairwise FST across Suillus brevipes populations. CAc - California coast, CAm - California mountain, CO - Colorado, MN - Minnesota.

| CAc | CAm | CO | MN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAc | - | |||

| CAm | 0.09 | - | ||

| CO | 0.19 | 0.12 | - | |

| MN | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.3 | - |

Selective sweep detection and association between genomic sites and environmental variables

Selective sweep analyses revealed over 1500 genomic regions with signatures of positive selection in each population and all populations combined. Only 95 sites were recovered as swept in all analyses. Sweeps were prevalent across the majority of scaffolds, with larger scaffolds containing more swept sites (Fig. S3). Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analyses failed to detect enriched GO categories across the sweeps, indicating that sites under positive selection span a wide range of functions.

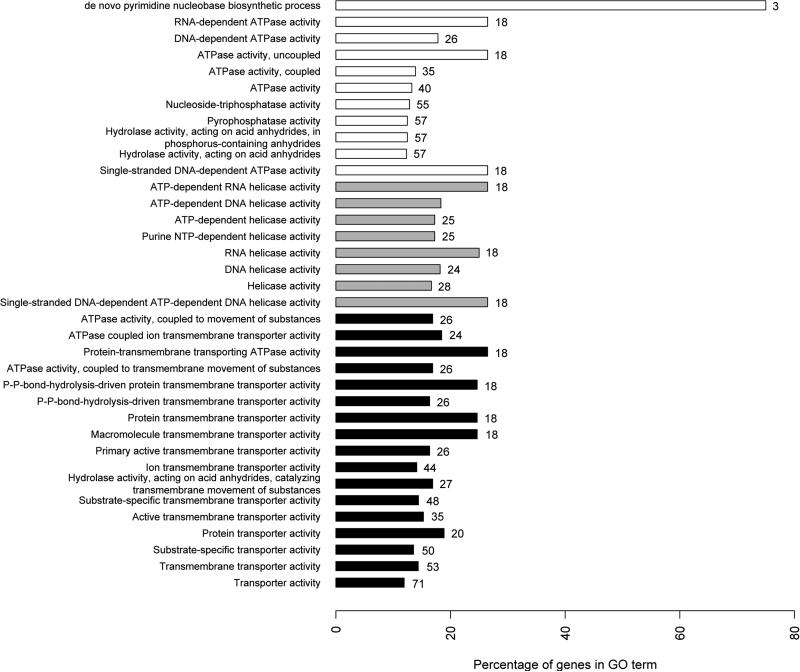

LFMM analyses found 18744 sites significantly associated with envPC1 (which is heavily influenced by winter temperature and precipitation) and 6776 sites with envPC2 (which is correlated with weather heterogeneity throughout the year). GO enrichment analyses on these sites revealed that the categories significantly enriched for envPC1 were ATPase-driven transmembrane transporters and ATPase-dependent helicases (Fig. 6a), while envPC2 was significantly enriched with protein transmembrane transporter activity (Fig 6b).

Figure 6.

Percentage and number of genes assigned to different gene ontology categories significantly correlated with envPC1 (a) and envPC2 (b) as assessed by ClueGO (p<0.005). Only the genes that were significantly correlated with one envPC compared to the other were listed. ‘Percentage of genes in GO term’ refers to the percentage of genes from the uploaded cluster that were associated with the term, compared to all S. brevipes genes associated with the same term. The numbers on bars correspond to the numbers of genes from the analyzed cluster associated with each category. Gray - helicase activity; black - transmembrane transporters; white - other categories.

We found a total 862 functional domains in the LFMM sites correlated with the two environmental principal components (727 in envPC1, 459 in envPC2, with an overlap of 324 domains). A hypergeometric test revealed significant differences between the domains in envPC1 and envPC2 (p = 1.8e-93). Of 862 functional domains with genetic variation either in envPC1 or envPC2, three were identified as not randomly enriched in envPC1 or/and envPC2 (Table 3; FDR < 0.05; p < 0.05). The domains’ functions were protein kinase, WD40 repeats and nucleic acid binding and DNA/RNA helicase.

Table 3.

Significantly enriched pfam domains in envPC1 and envPC2, with respective function overlap and counts.

| ID | p-value | Function | Overlap (envPC1 vs envPC2) | Total count | envPC1 count | envPC2 count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD000001 | 1.62E-05 | Protein kinase | 12 | 338 | 54 | 22 |

| PD000018 | 1.94E-09 | WD40 repeats | 15 | 565 | 56 | 28 |

| PF00270 | 1.55E-05 | Nucleic acid binding, DNA/RNA helicase | 9 | 65 | 16 | 11 |

We found 43 individual genomic sites that were both significantly associated with environmental parameters and showed signatures of positive selection as assessed by LFMM and selective sweep analysis (Table 4). These sites were located across the scaffolds and most were outliers restricted to a single population. These results suggest the existence of local adaptation, with different alleles being selected for in different populations. Eleven genomic sites currently have no predicted function and four sites were included in start/stop codons. The latter were adjacent to transporter genes and hydrolases, indicating potential loss-of-function mutations. Notably, the Na+/H+ exchanger associated with salt tolerance found to be fixed in the coastal California population in Branco et al. (2015) was also found to be a relevant genomic region for that population only, and it was under strong positive selection and strongly associated with both envPC1 and envPC2.

Table 4.

Outlier genomic positions in both LFMM and selective sweeps, with location, protein identification number, population, function, association to environmental PC and whether they are located in Dxy outlier windows. Grey highlights the sodium/proton exchanger described in (Branco et al. 2015).

| Population | Scaffold | Position | Protein ID | Function | PC | Dxy outlier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAc | 8 | 148810 | 1781890 | Binding | 1 | |

| CAc | 50 | 112014 | 420413 | DNA binding, transcription | 1 | |

| CAc | 32 | 38903 | 798540 | GTPase activity, transcription factor binding | 1 | |

| CAc | 15 | 190772 | 186662 | Hydrolase activity | 1 | yes |

| CAc | 12 | 293833 | 718100 | Integral to membrane; Na+/H+ exchanger | 1, 2 | yes |

| CAc | 42 | 167903 | 952639 | No annotation | 1 | |

| CAc | 50 | 143767 | 1853970 | No annotation | 1 | |

| CAc | 60 | 35465 | 833182 | No annotation | 1, 2 | |

| CAc | 12 | 323480 | 186662 | Oxidoreductase activity | 1 | yes |

| CAc | 27 | 176597 | 871448 | Prenyltransferase activity, integral to membrane | 1 | |

| CAc | 42 | 47281 | 1864144 | Protein kinase activity | 1 | |

| CAc | 32 | 190685 | - | Start codon | 1 | |

| CAc | 60 | 38348 | 804009 | Tetrapeptide transporter, OPT1/isp4 | 1 | |

| CAc | 32 | 189047, 189371, 190230 | 798695 | Vacuolar proton-transporting V-type ATPase, V1 domain | 1 | |

| CAc, CAm, CO | 42 | 203805 | 856219 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | 1, 2 | yes |

| CAc, CO | 63 | 173649 | 732802 | Hydrolase activity | 1 | |

| CAc, CO, MN | 23 | 88396 | 722280 | Small oligopeptide transporter | 1 | yes |

| CAc, MN | 19 | 109622 | 950841 | Oxidoreductase activity | 1 | |

| CAc, MN | 12 | 250675 | - | Stop codon | 1 | |

| CAm | 94 | 92412 | 857933 | Beta-glucan synthesis-associated, SKN1 | 2 | |

| CAm | 32 | 34301 | 871507 | Calcium ion binding | 1 | |

| CAm | 17 | 242097 | 770019 | No annotation | 2 | |

| CAm | 43 | 47379 | 1839120 | No annotation | 1 | |

| CAm, CO | 36 | 193163 | 831272 | No annotation | 1 | |

| CAm, CO | 106 | 47087 | 739551 | No annotation | 2 | yes |

| CAm, CO | 22 | 52119 | - | Stop codon | 1 | |

| CAm, MN | 8 | 71288 | 853314 | Alpha/beta hydrolase fold-1 | 1, 2 | |

| CAm, MN | 78 | 96366 | 738222 | No annotation | 1 | |

| CO | 11 | 182993 | 716688 | No annotation | 1, 2 | |

| CO | 20 | 126831 | 770517 | Nucleotide catabolic process | 1 | |

| CO | 50 | 110208 | 729737 | Oxidoreductase activity | 1, 2 | |

| CO | 17 | 137848 | 769788 | Regulation of transcription, translational initiation | 1 | |

| CO | 1 | 353572 | 1926079 | Ubiquitin-protein ligase activity | 2 | |

| MN | 199 | 58134 | 747856 | Cyclic nucleotide biosynthetic process | 2 | |

| MN | 8 | 41947 | 715982 | Ion channel activity | 1, 2 | |

| MN | 1 | 838431 | 824286 | Mitochondrial intermembrane space protein transporter complex | 1 | |

| MN | 110 | 82327 | 1053000 | NADH quinone oxireductase | 1 | |

| MN | 181 | 54297 | 878990 | No annotation | 1, 2 | |

| MN | 11 | 367299 | 793247 | Phosphoglicerate mutase | 1 | |

| MN | 86 | 10054 | 834508 | Protein binding | 1 | |

| MN | 40 | 165975 | 800418 | Protein kinase activity | 1 | |

| MN | 63 | 70718 | - | Stop codon | 1 | |

| MN | 86 | 5096 | 857630 | Transporter activity | 1 |

Discussion

Suillus brevipes biogeography

Suillus brevipes is an obligate mycorrhizal associate of Pinus subgenus Pinus and is widespread in North America (Smith, A. H. & Thiers, H. D. 1964, Nguyen et al., in press), tightly associated with the range of its hosts. This species is one of the most ruderal of the genus and is commonly found with young pine trees at forest margins and also with introduced and invasive pines (Ashkannejhad & Horton 2006, Peay et al. 2007, Hynson et al. 2013). This high level of host specificity limits the species distribution and creates a mosaic continental structure of habitat for S. brevipes.

In spite of the prolific production of aerially dispersed meiotic spores in Suillus spp. (Peay et al. 2012, Dahlberg & Stenlid 1994), there is mounting evidence that effective dispersal is limited to a fairly fine spatial scale, which is consistent with the idea that ‘almost nothing is everywhere’ (Gladieux et al. 2015a, Taylor et al. 2006, Peay et al. 2010). In fact, recent work showed that the spore loads of ectomycorrhizal fungi, including Suillus species, decrease exponentially as spores travel away from their source, support the hypothesis that these fungi are not very effective at dispersing over long distances (Peay et al. 2012). For example, even though S. pungens was estimated to produce 8 trillion spores/km2 within its host forest, its spore load decreased exponentially with distance from the forest edge, with spore levels insufficient to consistently colonize pine seedlings at distances greater than 1km (Peay et al. 2012). Such observed dispersal limitation at the local scale is also consistent with both the population genomics results of Branco et al. (2015) revealing two isolated and locally adapted S. brevipes populations in California and the results reported here. Long distance spore dispersal in S. brevipes is thus likely to be rare, and if it occurs, immigrant genotypes may be less fit than local ones. This explanation is consistent with our finding that North American S. brevipes is subdivided into multiple, clearly circumscribed genetic clusters.

The least distinct and most genetically diverse populations occur in the two Canadian sites and to a less extent in Wyoming. The finding of individuals assigned to multiple clusters in Canada might suggest admixture between individuals from differentiated populations. This hybridization idea is consistent with the known postglacial history of P. banksiana and P. contorta, the only hosts in this area. In fact, these pine species form their own hybrid zone in western Alberta within the Whitecourt site that we sampled (Yeatman 1967). Population genetic studies (Godbout et al. 2010) and pollen records (Williams et al. 2004) suggest that these pine species met in Alberta as the glaciers retreated, by reinvasion from Eastern North America (P. banksiana) and from one or more western mountain corridors (P. contorta) (Critchfield 1985).

Alternatively, Canadian admixture can be interpreted as Alberta hosting the oldest S. brevipes populations, and therefore the most diverse, from which all other populations would be derived. This interpretation is consistent with the individuals genealogy and with previous findings of artifactual inference of admixture in ancestral populations in other organisms (Kauer et al. 2003, Schöfl & Schlötterer 2006, Gladieux et al. 2008), but would require the presence of a pine refugia in this area during glaciation..

Adaptation in Suillus brevipes

We found evidence consistent with abiotic environmental adaptation in S. brevipes populations across North America. Genes found both under positive selection and significantly associated with climatic environmental variables were mainly involved in transmembrane transport of substances and helicase activity. Even though these gene categories are involved in multiple cell functions, we argue that they can be directly related to environmental adaptation, namely in the physiological responses to conditions determined by variations in temperature and precipitation.

Transmembrane transporter genes are known to play important roles, including responding to environmental stress in wide variety of organisms (Chan et al. 2011, Krulwich et al. 2011, Mansour 2014, Chen et al. 2003, Apse et al. 1999, Rizzello et al. 2013, Mahajan & Tuteja 2005, Heide & Poolman 2000). In fungi, transporters are involved in environmental sensing and are crucial for detecting and responding to a wide variety of cues, including chemistry, temperature and water availability (Aguilera et al. 2007, Bahn & Mühlschlegel 2006, Bahn et al. 2007, Maldonado-Mendoza et al. 2001, Javelle et al. 2003, Harrison et al. 2002, Dietz et al. 2011, Pettersson et al. 2005, Peter et al. 2016). Temperature and precipitation differences across the sampled sites can therefore be directly linked to the enriched transporter gene categories detected in our study. Cold stress in particular affects the activity of membrane transporters due to changes in membrane fluidity that can have multiple nefarious consequences, including decreased nutrient uptake (Aguilera et al. 2007). Water stress on the other hand can be mitigated by membrane proteins that mediate water transfer (aquaporins, Carbrey & Agre 2009). These transporters are known to occur in fungi (Pettersson et al., 2005), being involved in the transport of both water and ammonia in ectomycorrhizal fungi and presumed to be directly linked to mechanisms of environmental adaptation (Dietz et al. 2011, Peter et al. 2016).

Helicases are motor proteins that separate nucleic acids strands. These enzymes are involved in many fundamental processes such as replication, transcription, translation and nucleic acid repair and are known to be involved in environmental stress response. RNA helicases play a role in responding to abiotic stressors by changing the export of nuclear mRNA, translation initiation, mRNA decay, rRNA processing, transcription and the progression of cell cycle (Owttrim 2006). RNA helicases are known to be involved in adaptation to cold in bacteria and fungi (Barria et al. 2013, Pandiani et al. 2010, Aguilera et al. 2007). In the aforementioned “reverse ecology” study of Neurospora crassa populations (Ellison et al. 2011), an RNA helicase was one of several genes hypothesized to be important to cold adaptation and one of only two genes whose role in cold adaptation could be confirmed by gene deletion. Cold stress can lead to the stabilization of RNA secondary structure, impairing transcription, translation and degradation, and RNA helicases act to melt such structures allowing for RNA degradation (Barria et al. 2013). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, RNA helicases are induced during the early stages of cold stress response (Aguilera et al. 2007).

DNA helicases are involved in DNA repair, as they allow repair machinery to access the single stranded DNA (Goldman et al. 2002), and are also induced by cold stress (Vashisht et al. 2005), allowing for repair mechanisms to act on this molecule. Further functional tests addressing the role of candidate genes are needed to investigate potential differences in environmental adaptation (including cold and water stress response) in S. brevipes individuals across North America.

The membrane Na+/H+ exchanger described in Branco et al. (2015) to be under strong positive selection, was again found here among the highly differentiated genes and strongly associated with envPC1 and envPC2 in the coastal California population. This gene is homologous to Nha-1, known for enhancing salt tolerance in plants and S. cerevisiae (Apse et al. 1999, Nass et al. 1997) and a good candidate for local adaptation in S. brevipes. It is therefore not surprising that this gene is located in a putative selective sweep region and located in a Dxy outlier genomic window. However, our LFMM analyses were restricted to climatic variables and did not include soil parameters, so possible explanations for the strong correlation with envPCs include pleiotropic functional properties or linkage to another gene truly correlated with weather variability.

Concluding remarks

Our study provides a unique large-scale view of within species evolution and sheds light on the factors driving environmental adaptation in fungi. We used a large-scale dataset to detect genomic regions correlated to climatic parameters and harboring signatures of positive selection without any prior information on phenotypic differences, population units or environmental factors that could underlie potential adaptation. Such reverse ecology approach is very suitable for microbial systems, where there is very little a priori information. Fungi in particular have small genome sizes, simple morphologies, short generation times and a multitude of life styles, being exceptional models for studying adaptation in eukaryotes (Gladieux et al., 2014). Reverse ecology has in fact revealed hidden fungal environmental adaptation in several species so far (e.g. Branco et al. 2015, Ellison et. al. 2011, Gladieux et. al. 2015b and Badouin et. al. submitted to this issue). Genome scans are therefore a useful framework for identifying putative adaptive genes responsible for local adaptation, and the results can motivate functional tests aimed at linking genotypes to phenotypes and are crucially needed for a full understanding of the genetic basis of adaptation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Cathy Cripps and her lab for providing Suillus cultures and Matthew Smith for inadvertently providing an extra outgroup species. Holly Edes and Ravi Alla provided technical assistance, Lucinda Lawson assisted in obtaining and analyzing climatic data, Olivier François helped implementing LFFM, Steven Wu assisted in implementing enrichment analyses. Tatiana Giraud provided comments on earlier drafts and enthusiastically supported this study. Three anonymous reviewers provided insightful comments on this manuscript. This work was funded by NSF Dimension of Biodiversity grant DBI-1046115 and DEB-1257528, and used the Vincent J. Coates Genomics Sequencing Laboratory at UC Berkeley, supported by NIH S10 Instrumentation Grants S10RR029668 and S10RR027303.

Footnotes

Author contributions

S.B., J.W.T. and T.D.B. designed the study, S.B., N.N., R.V., K.G.P., J.W.T. and T.D.B. collected samples, S.B. processed the samples, S.B., K.B., H-L.L., P.G., C.E.E and H.B. performed analyses, S.B. wrote the manuscript with comments from all co-authors.

Data accessibility

DNA sequences: Short Read Archive accessions in Table S1 (Supporting information).

Data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.p5dm3

References

- Aguilera J, Randez-Gil F, Prieto JA. Cold response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: new functions for old mechanisms. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2007;31:327–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apse MP, Aharon GS, Snedden WA, Blumwald E. Salt Tolerance Conferred by Overexpression of a Vacuolar Na+/H+ Antiport in Arabidopsis. Science. 1999;285:1256–1258. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkannejhad S, Horton TR. Ectomycorrhizal ecology under primary succession on coastal sand dunes: interactions involving Pinus contorta, suilloid fungi and deer. The New Phytologist. 2006;169:345–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badouin H, Gladieux P, Gouzy J, et al. Widespread selective sweeps throughout the genome of the model pathogenic fungi and identification of effector candidates. Molecular Ecology. doi: 10.1111/mec.13976. Submitted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahn Y-S, Mühlschlegel FA. CO2 sensing in fungi and beyond. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2006;9:572–578. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahn Y-S, Xue C, Idnurm A, et al. Sensing the environment: lessons from fungi. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2007;5:57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barria C, Malecki M, Arraiano CM. Bacterial adaptation to cold. Microbiology. 2013;159:2437–2443. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.052209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenberg D, Von Kuster G, Coraor N, et al. Galaxy: a web-based genome analysis tool for experimentalists. In: Ausubel FM, editor. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Wiley; 2010. pp. 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branco S, Gladieux P, Ellison CE, et al. Genetic isolation between two recently diverged populations of a symbiotic fungus. Molecular Ecology. 2015;24:2747–2758. doi: 10.1111/mec.13132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbrey JM, Agre P. Discovery of the Aquaporins and Development of the Field. In: Beitz PDE, editor. Aquaporins Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 2009. pp. 3–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CX, Reyes-Prieto A, Bhattacharya D. Red and Green Algal Origin of Diatom Membrane Transporters: Insights into Environmental Adaptation and Cell Evolution. PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e29138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Toone WM, Mata J, et al. Global Transcriptional Responses of Fission Yeast to Environmental Stress. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2003;14:214–229. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colpaert JV, Wevers JHL, Krznaric E, Adriaensen K. How metal-tolerant ecotypes of ectomycorrhizal fungi protect plants from heavy metal pollution. Annals of Forest Science. 2011;68:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Critchfield WB. The late Quaternary history of lodgepole and jack pines. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 1985;15:749–772. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg A, Stenlid J. Size, distribution and biomass of genets in populations of Suillus bovinus (L.: Fr.) Roussel revealed by somatic incompatibility. New Phytologist. 1994;128:225–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danecek P, Auton A, Abecasis G, et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2156–2158. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz S, von Bülow J, Beitz E, Nehls U. The aquaporin gene family of the ectomycorrhizal fungus Laccaria bicolor: lessons for symbiotic functions. New Phytologist. 2011;190:927–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobzhansky T. Genetics of Natural Populations. XVI. Altitudinal and Seasonal Changes Produced by Natural Selection in Certain Populations of Drosophila Pseudoobscura and Drosophila Persimilis. Genetics. 1948;33:158–176. doi: 10.1093/genetics/33.2.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CE, Hall C, Kowbel D, et al. Population genomics and local adaptation in wild isolates of a model microbial eukaryote. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011:201014971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014971108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enjalbert J, Duan X, Leconte M, Hovmøller MS, DE Vallavieille-Pope C. Genetic evidence of local adaptation of wheat yellow rust (Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici) within France. Molecular ecology. 2005;14:2065–2073. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Molecular Ecology. 2005;14:2611–2620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frichot E, François O. LEA: An R package for landscape and ecological association studies. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. 2015;6:925–929. [Google Scholar]

- Frichot E, Schoville SD, Bouchard G, François O. Testing for Associations between Loci and Environmental Gradients Using Latent Factor Mixed Models. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2013;30:1687–1699. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli M, Vieira FG, Korneliussen TS, et al. Quantifying Population Genetic Differentiation from Next-Generation Sequencing Data. Genetics. 2013;195:979–992. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.154740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardine B, Riemer C, Hardison RC, et al. Galaxy: a platform for interactive large-scale genome analysis. Genome Research. 2005;15:1451–1455. doi: 10.1101/gr.4086505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladieux P, Feurtey A, Hood ME, et al. The population biology of fungal invasions. Molecular Ecology. 2015;24:1969–1986. doi: 10.1111/mec.13028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladieux P, Wilson BA, Perraudeau F, et al. Genomic sequencing reveals historical, demographic and selective factors associated with the diversification of the fire-associated fungus Neurospora discreta. Molecular Ecology. 2015b;22:5657–5675. doi: 10.1111/mec.13417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladieux P, Ropars J, Badouin H, et al. Fungal evolutionary genomics provides insight into the mechanisms of adaptive divergence in eukaryotes. Molecular Ecology. 2014;23:753–773. doi: 10.1111/mec.12631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladieux P, Zhang X-G, Afoufa-Bastien D, et al. On the Origin and Spread of the Scab Disease of Apple: Out of Central Asia. PLOS ONE. 2008;3:e1455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godbout J, Beaulieu J, Bousquet J. Phylogeographic structure of jack pine (Pinus banksiana; Pinaceae) supports the existence of a coastal glacial refugium in northeastern North America. American Journal of Botany. 2010;97:1903–1912. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1000148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goecks J, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J, Galaxy Team Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biology. 2010;11:R86. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman GH, McGuire SL, Harris SD. The DNA Damage Response in Filamentous Fungi. Fungal Genetics and Biology. 2002;35:183–195. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.2002.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison MJ, Dewbre GR, Liu J. A Phosphate Transporter from Medicago truncatula Involved in the Acquisition of Phosphate Released by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. The Plant Cell. 2002;14:2413–2429. doi: 10.1105/tpc.004861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heide T van der, Poolman B. Osmoregulated ABC-transport system of Lactococcus lactis senses water stress via changes in the physical state of the membrane. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2000;97:7102–7106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, Jones PG, Jarvis A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology. 2005;25:1965–1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hynson NA, Merckx VSFT, Perry BA, Treseder KK. Identities and distributions of the co-invading ectomycorrhizal fungal symbionts of exotic pines in the Hawaiian Islands. Biological Invasions. 2013;15:2373–2385. [Google Scholar]

- Javelle A, André B, Marini A-M, Chalot M. High-affinity ammonium transporters and nitrogen sensing in mycorrhizas. Trends in Microbiology. 2003;11:53–55. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(02)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones FC, Grabherr MG, Chan YF, et al. The genomic basis of adaptive evolution in threespine sticklebacks. Nature. 2012;484:55–61. doi: 10.1038/nature10944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauer M, Dieringer D, Schlötterer C. Nonneutral admixture of immigrant genotypes in African Drosophila melanogaster populations from Zimbabwe. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2003;20:1329–1337. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korneliussen TS, Albrechtsen A, Nielsen R. ANGSD: Analysis of Next Generation Sequencing Data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:356. doi: 10.1186/s12859-014-0356-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krulwich TA, Sachs G, Padan E. Molecular aspects of bacterial pH sensing and homeostasis. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2011;9:330–343. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent S, Pfeifer SP, Settles M, et al. The population genomics of rapid adaptation: disentangling signatures of selection and demography in white sands lizards. Molecular Ecology. 2016;25:306–323. doi: 10.1111/mec.13385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YF, Costello JC, Holloway AK, Hahn MW. “Reverse Ecology” and the Power of Population Genomics. Evolution. 2008;62:2984–2994. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan S, Tuteja N. Cold, salinity and drought stresses: an overview. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2005;444:139–158. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Mendoza IE, Dewbre GR, Harrison MJ. A Phosphate Transporter Gene from the Extra-Radical Mycelium of an Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus Glomus intraradices Is Regulated in Response to Phosphate in the Environment. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2001;14:1140–1148. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.10.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour MMF. The plasma membrane transport systems and adaptation to salinity. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2014;171:1787–1800. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mboup M, Bahri B, Leconte M, et al. Genetic structure and local adaptation of European wheat yellow rust populations: the role of temperature-specific adaptation. Evolutionary Applications. 2012;5:341–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2011.00228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachman MW, Hoekstra HE, D'Agostino SL. The genetic basis of adaptive melanism in pocket mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100:5268–5273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0431157100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nass R, Cunningham KW, Rao R. Intracellular Sequestration of Sodium by a Novel Na+/H+ Exchanger in Yeast Is Enhanced by Mutations in the Plasma Membrane H+−ATPase. Insights into mechanisms of sodium tolerance. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:26145–26152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen R. Molecular Signatures of Natural Selection. Annual Review of Genetics. 2005;39:197–218. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.112420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen R, Williamson S, Kim Y, et al. Genomic scans for selective sweeps using SNP data. Genome Research. 2005;15:1566–1575. doi: 10.1101/gr.4252305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novembre J, Di Rienzo A. Spatial patterns of variation due to natural selection in humans. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2009;10:745–755. doi: 10.1038/nrg2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen NH, Vellinga EC, Bruns TD, Kennedy PG. Global phylogenetic assessment of Suillus ITS sequences supports morphologically defined species while revealing synonymous and undescribed taxa. Mycologia. doi: 10.3852/16-106. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owttrim GW. RNA helicases and abiotic stress. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34:3220–3230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandiani F, Brillard J, Bornard I, et al. Differential involvement of the five RNA helicases in adaptation of Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579 to low growth temperatures. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2010;76:6692–6697. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00782-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidis P, Živković D, Stamatakis A, Alachiotis N. SweeD: Likelihood-based detection of selective sweeps in thousands of genomes. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2013;30:2224–2234. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peay KG, Bidartondo MI, Elizabeth Arnold A. Not every fungus is everywhere: scaling to the biogeography of fungal–plant interactions across roots, shoots and ecosystems. New Phytologist. 2010;185:878–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peay KG, Bruns TD, Kennedy PG, Bergemann SE, Garbelotto M. A strong species–area relationship for eukaryotic soil microbes: island size matters for ectomycorrhizal fungi. Ecology Letters. 2007;10:470–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peay KG, Schubert MG, Nguyen NH, Bruns TD. Measuring ectomycorrhizal fungal dispersal: macroecological patterns driven by microscopic propagules. Molecular Ecology. 2012;21:4122–4136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter M, Kohler A, Ohm RA, et al. Ectomycorrhizal ecology is imprinted in the genome of the dominant symbiotic fungus Cenococcum geophilum. Nature Communications. 2016;7:12662. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson N, Filipsson C, Becit E, Brive L, Hohmann S. Aquaporins in yeasts and filamentous fungi. Biology of the Cell. 2005;97:487–500. doi: 10.1042/BC20040144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzello A, Romano A, Kottra G, et al. Protein cold adaptation strategy via a unique seven-amino acid domain in the icefish (Chionodraco hamatus) PEPT1 transporter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:7068–7073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220417110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ropars J, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, López-Villavicencio M, et al. Adaptive Horizontal Gene Transfers between Multiple Cheese-Associated Fungi. Current Biology. 2015;25:2562–2569. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvaudon L, Giraud T, Shykoff JA. Genetic diversity in natural populations: a fundamental component of plant–microbe interactions. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2008;11:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöfl G, Schlötterer C. Microsatellite variation and differentiation in African and non-African populations of Drosophila simulans. Molecular Ecology. 2006;15:3895–3905. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer RM, vonHoldt BM, Harrigan R, et al. Genetic subdivision and candidate genes under selection in North American grey wolves. Molecular Ecology. 2016;25:380–402. doi: 10.1111/mec.13364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skotte L, Korneliussen TS, Albrechtsen A. Estimating individual admixture proportions from next generation sequencing data. Genetics. 2013;195:693–702. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.154138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AH, Thiers HD. A contribution towards a monograph of North American species of Suillus. Published by the authors; Ann Harbor, MI: 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SE, Read DJ. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Academic Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML Version 8: A tool for Phylogenetic Analysis and Post-Analysis of Large Phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stukenbrock EH, Bataillon T, Dutheil JY, et al. The making of a new pathogen: Insights from comparative population genomics of the domesticated wheat pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola and its wild sister species. Genome Research. 2011;21:2157–2166. doi: 10.1101/gr.118851.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JW, Turner E, Townsend JP, Dettman JR, Jacobson D. Eukaryotic microbes, species recognition and the geographic limits of species: examples from the kingdom Fungi. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2006;361:1947–1963. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vashisht AA, Pradhan A, Tuteja R, Tuteja N. Cold- and salinity stress-induced bipolar pea DNA helicase 47 is involved in protein synthesis and stimulated by phosphorylation with protein kinase C. The Plant Journal. 2005;44:76–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JW, Shuman BN, Webb T, Bartlein PJ, Leduc PL. Late-Quaternary Vegetation Dynamics in North America: Scaling from Taxa to Biomes. Ecological Monographs. 2004;74:309–334. [Google Scholar]

- Yeatman CW. Biogeography of Jack Pine. Canadian Journal of Botany. 1967;45:2201–2211. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.