Abstract

Medullary bone, a non-structural osseous tissue, serves as a temporary storage site for calcium that is needed for eggshell production in a number of avian species. Previous research focusing primarily on domesticated species belonging to the Anseriformes, Galliformes, and Columbiformes has indicated that rising estrogen levels are a key signal stimulating medullary bone formation; Passeriformes (which constitute over half of extant bird species and are generally small) have received little attention. In the current study, we examined the influence of estrogen on medullary bone and cortical bone in two species of Passeriformes: the Pine Siskin (Spinus pinus) and the House Finch (Haemorhous mexicanus). Females of these species received either an estradiol implant or were untreated as a control. After 4.5–5 months, reproductive condition was assessed and leg (femora) and wing (humeri) bones were collected for analysis using high-resolution (10 μm) micro-computed tomography scanning. We found that in both species estradiol-treated females had significantly greater medullary bone quantity in comparison to untreated females, but we found no differences in cortical bone quantity or microarchitecture. We were also able to examine medullary bone density in the pine siskins and found that estradiol treatment significantly increased medullary bone density. Furthermore, beyond the effect of the estradiol treatment, we observed a relationship between medullary bone quantity and ovarian condition that suggests that the timing of medullary bone formation may be related to the onset of yolk deposition in these species. Further research is needed to better understand the precise timing and endocrine regulation of medullary bone formation in Passerines and to determine the extent to which female Passerines rely on medullary bone calcium during the formation of calcified eggshells.

Keywords: Medullary bone, Estradiol treatment, Microcomputed tomography

1. Introduction

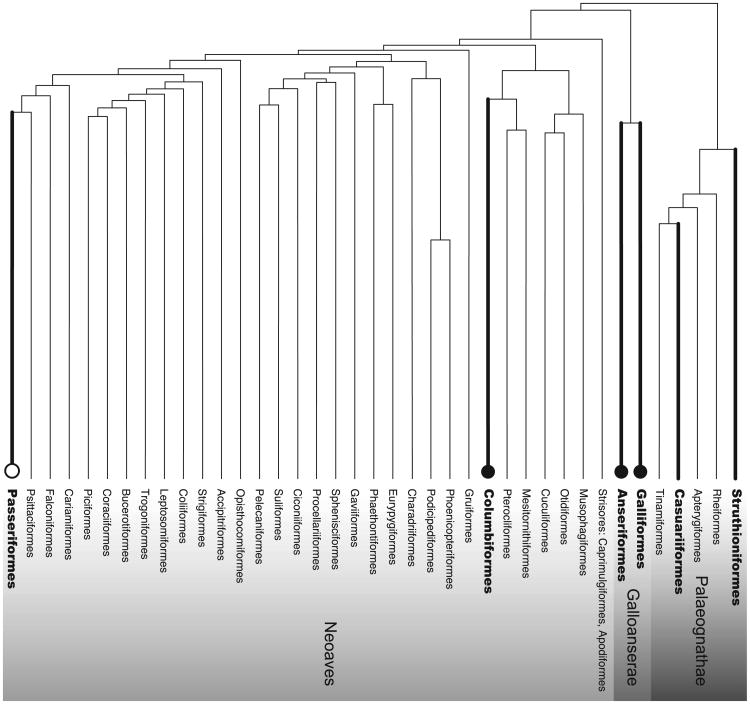

Medullary bone is a non-structural type of osseous tissue that serves as a labile calcium resource and can be used in the production of calcified eggshells (Bloom et al., 1958; Bonucci and Gherardi, 1975). The presence of medullary bone is well documented in the long bones of numerous bird species belonging to the orders Galliformes (chicken, quail, and other landfowl), Anseriformes (ducks and other waterfowl), and Columbiformes (pigeons) (Table 1). Until more recently, the presence of medullary bone among Passeriformes (songbirds) has been a subject of debate, but there is now strong evidence for its presence in several species (Table 1). Moreover, medullary bone has also now been documented in a species of the Struthioniformes (ostriches) and a species of the Casuariiformes (emus and cassowaries) (Table 1). Although these studies represent only a small proportion of avian orders, with most orders remaining to be investigated, the presence of medullary bone is now documented among a diverse distribution of the Aves including the three major clades of the Paleognathae, Gallonanserae, and Neoaves (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Avian species in which medullary bone has been observed and in which it has been determined that estrogens stimulate medullary bone formation.

| Order Species | Documentation of medullary bone (with reference) | Experimental evidence of estrogen-induced medullary bone (with reference) |

|---|---|---|

| Struthioniformes | ||

| Struthio camelus Ostrich | Schweitzer et al. (2005) | – |

| Casuariiformes | ||

| Dromaius novaehollandiae Emu | Schweitzer et al. (2005) | – |

| Galliformes | ||

| Colinus virginianus Bobwhite quail | Ringeon 1940 as reported in Simkiss (1961) | – |

| Coturnix japonica Japanese quail | Van de Velde et al. (1985) |

Turner and Schraer (1977) Miller and Bowman (1981) Fisher and Shraer (1982) Ohashi et al. (1987) |

| Gallus domesticus Domestic chicken |

Bloom et al. (1958) Zambonin-Zallone and Mueller (1969) |

Zondeck (1936) Urist and Deutsch (1960) |

| Anseriformes | ||

| Anas platyrhyncha Mallard/Pekin duck |

Landauer et al. (1941) Landauer and Zondek (1944) |

Landauer et al. (1941) Landauer and Zondek (1944) Acenzi et al. (1963) |

| Branta canadensis Canada goose | Hanson 1958 as reported in Bloom et al. (1958) | – |

| Columbiformes | ||

| Columbia livia Pigeon |

Kyes and Potter (1934) Bloom et al. (1941) |

Acenzi et al. (1963) Pfeiffer and Gardner (1938) Bloom et al. (1942) Riddle et al. (1945) Bonucci and Gherardi (1975) |

| Passeriformes* | ||

| Catharus fuscescens Veery | Squire et al. (2011) | – |

| Hylocichla mustelina Wood Thrush | Squire et al. (2011) | – |

| Molothrus ater Brown-headed cowbird | Ankney and Scott (1980) | – |

| Parus major Great tit | Eeva et al. (2000) | – |

| Passer domesticus House Sparrow | Kirschbaum et al. (1939) and Pfeiffer et al. (1940) | Pfeiffer et al. (1940)# |

| Serinus canaries Canary | Mentioned in Bloom et al. (1958) and reviewed in Simkiss (1961) | – |

– indicates no data.

Other studies using radiographs from Tree Swallows (Tachycineta bicolor), Brown-headed cowbirds, and Great tits that were 9–22 days pre-laying and 17–25 days post-laying suggested no medullary bone (Pahl et al., 1997).

See text for description of evidence from this study.

Fig. 1.

Phylogeny of avian orders based on Prum et al. (2015). Heavy lines indicate orders in which medullary bone has been observed. Light lines indicate orders that have not yet been studied. Filled circles indicate orders in which estrogen-stimulated medullary bone deposition has been documented. The open circle for Passeriformes indicates that medullary bone is likely estrogen-induced (see text for details). References are listed by species in Table 1.

As a calcium reservoir for eggshell production, medullary bone formation necessarily precedes eggshell formation (Bloom et al., 1958; Ankney and Scott, 1980). Medullary bone formation has been shown to be closely associated with ovarian follicle development (Kyes and Potter, 1934; Bloom et al., 1958) and, furthermore, medullary bone resorption and the subsequent release of calcium has been associated with production of calcified eggshells in several avian species (Bloom et al., 1941, 1958; Mueller et al., 1964; Ankney and Scott, 1980). Changes in circulating hormone levels appear to play an important role in triggering medullary bone formation. Studies focusing on four species belonging to the orders Galliformes, Anseriformes, and Columbiformes have found that elevated estrogen levels stimulate medullary bone formation (Table 1), and it has been presumed that this is the case across the Aves and their recent ancestors (e.g., Prondvai, In press). Yet, these studies reflect a small subset of avian diversity (Fig. 1), particularly in light of the fact that most, if not all of them, focused on domesticated birds. Thus, comparative data on a greater diversity of avian species, including non-domesticated species, are needed before we can confidently draw conclusions about distribution and evolution of this trait. It seems particularly critical to obtain more information about Passerines, given that they represent over half of all extant bird species and are generally smaller in size than the species previously studied.

To that end, the goal of the current study was to examine the influence of estrogens and reproductive status on medullary bone development in females of two species belonging to the Passeriformes. Medullary bone has been documented in several passerine species, but the role of estrogens in triggering medullary bone development in this group remains poorly studied (Table 1). A single previous passerine study that was conducted on the house sparrow (Passer domesticus) found that estradiol caused “hyperossification,” which we believe is consistent with medullary bone formation based on the histological analysis included in the study (Pfeiffer et al., 1940). Here, we used micro-computed tomography to visualize and quantify medullary bone in the wing (humeri) and leg (femora) bones of estradiol treated and non-estradiol treated female House Finches (Haemorhous mexicanus) and Pine Siskins (Spinus pinus) of known reproductive status. Thus, we were also able to examine medullary bone quantity relative to the ovarian condition and maximum follicle size of each individual at the time of sacrifice.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethics

Experimental procedures for both house finch and pine siskin studies were approved by the UC Davis Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All birds were collected under the appropriate state (CA, OR, or WY) and federal permits.

2.2. Experimental design for house finches

The house finches that were used for this study were captured and treated as part of a separate study that focused on the influence of hormones on the transition from breeding to molt (Brazeal, 2014). House finches were collected throughout the month of June 2009 near Davis, CA (38°32′ N, 121°44′ W) and Dixon, CA (38°26′ N, 121°49′ W) using potter traps. Upon capture, birds were housed in groups until June 27, 2009 when they were assigned to one of two groups: unimplanted females (n = 8) housed with testosterone-implanted males, and estrogen implanted females (n = 3) paired with unimplanted males. Once assigned to a group, the birds were housed individually in cages placed into acoustic isolation chambers (Industrial Acoustics Company, Bronx, NY) that had 3 shelves, each of which fit 2 cages. The cage set-up was such that an unimplanted female was on the same shelf as a testosterone-implanted male and an estrogen-implanted female was on the same shelf as an unimplanted male. In this way, the cages were adjacent to each other and it was possible for the birds to interact. Additionally, the pairs of birds could hear, but not see, birds on the other shelves of the same chamber. From the time of capture through the duration of the experiment, all birds were housed on photoperiods that mimicked natural changes in day length at a latitude of 38°N.

Estradiol (E2) treated females initially received implants on July 2, 2009 and were switched to lower dose implants on July 24, 2009 (described below). At the end of the study (December 1, 2009), all birds were sacrificed with an overdose of isoflurane followed by decapitation. At the time of sacrifice, the ovary of each female was examined to quantify reproductive condition.

2.3. Experimental design for pine siskins

The pine siskins used for this study were part of a larger experiment focused on reproductive timing (Watts et al., 2016). The birds were captured in Jackson, WY (43° 28′ N, 110° 48′ W) between 26 Aug and 11 Sept 2009 and in Mt Ashland, OR (42° 4′N 122° 43′W) on 2 Dec 2009. Two additional females had been captured in Jackson, WY on 13–14 Oct 2008. All pine siskins were captured using mist nets. Upon capture birds were housed in large indoor flight cages on photoperiods that simulated natural changes in day length at a latitude of 38°N, and prior to winter solstice (21 Dec 2009), males and females were separated into different cages. Following winter solstice birds were maintained on winter solstice day length (9.7L:14.3D) until 13 Jan 2010 at which point they were put on 12L:12D for the remainder of the experiment. This photoperiod was selected for the purpose of the original study (Watts et al., 2016) as it is permissive for reproductive development in this species, but not highly stimulatory; birds eventually terminate reproduction and initiate molt when held on this photoperiod (Watts unpublished).

On the first day of the treatment, 18 Feb 2010, females were randomly assigned to one of two groups: the estradiol implanted (E2, n = 8) or the non-implanted (CTR, n = 8) groups. Two days after implantation, on 20 Feb 2010, each female was moved into an individual cage with a randomly assigned male partner. Birds were then housed in acoustic isolation chambers (Industrial Acoustics Company, Bronx, NY) with 1 or 2 other cages of birds belonging to the same treatment group for the duration of the experiment. Several females (n = 4) showed adverse reactions to the original estradiol implant dose (i.e., lethargy and excessive lipid in the blood; see Watts et al., 2016 for further details). Therefore, as necessary, the original implant was removed and replaced with a lower dose implant. This occurred 1–2 months after the original implants were given.

Throughout the study, all birds were monitored and notations were made when a female had laid an egg. Between 5 and 8 July 2010, all birds were euthanized with an overdose of isoflurane and perfused transcardially with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. At necropsy, the ovary was examined to quantify reproductive condition.

2.4. 17β-estradiol implants

For both the house finch and pine siskin experiments estradiol implants were created using silastic tubing (1.47 mm inner diameter) filled with crystalline 17β-estradiol (Sigma E-8875) and sealed at both ends with silicon adhesive. For house finches, implants were 10 mm (inner length of packed hormone). For pine siskins, implants were 5 mm (inner length of packed hormone). Implant sizes were based on doses (corrected for body size) used in other songbirds to stimulate female reproductive behavior and achieve circulating estradiol levels similar to those in breeding females (Wingfield and Farner, 1978; Moore, 1983; Wingfield and Monk, 1994; Searcy and Capp, 1997). We also confirmed that this dose induced defeathering of the brood patch in female pine siskins in a pilot study. Implants were soaked in sterile saline overnight before implanting. Following application of a topical anesthetic, implants were inserted subcutaneously on the flank through a small incision, which was sealed with veterinary adhesive.

When the original estradiol dose was too high, house finches were switched to a 5 mm implant. For pine siskins, ‘low dose’ implants were made by mixing 2 mg of crystalline 17β-estradiol per mL of silicon adhesive and extruding an implant that was ∼2 mm diameter and 10 or 7 mm in length. The 7 mm length implants were used for females for which the dose from the 10 mm extruded implant was still too high. The silastic implants were monitored visually to ensure that there was still hormone remaining in the implants throughout the studies. Since this was not possible for the low dose pine siskin implants, these were replaced with new ones after approximately 2 months.

2.5. Plasma corticosterone assay

Because both the house finch and pine siskin data were collected as part of larger experiments with different foci (Brazeal, 2014; Watts et al., 2016), the control birds in these experiments did not receive empty implants or sham implant surgeries. However, the control birds in both experiments were subject to surgical laparotomies to measure gonadal condition (see Brazeal, 2014 and Watts et al., 2016 for details). Implanted birds did not receive this additional type of surgery. Stress and increases in glucocorticoid levels have been found to have adverse effects on cortical bone quantity in birds (Urist and Deutsch, 1960; Satterlee and Roberts, 1990). However, stress has also been found to induce higher quantities of medullary bone, which has been attributed to a stress-induced decrease in reproduction (Satterlee and Roberts, 1990). Given these effects of stress on bone, and medullary bone in particular, we wanted to assess whether differences in surgical procedures between treatment groups might cause differences in stress levels. To quantify potential differences in stress between the treatment groups, we measured circulating corticosterone (CORT) levels from blood samples collected during the pine siskin experiment on 16 April 2010 and 25 May 2010. Blood was collected from the alar vein into heparinized microhematocrit tubes, which were stored on ice until they were centrifuged and the plasma collected. Plasma was stored at −20 °C until it was assayed for CORT. Only samples collected within 4 min of first opening the acoustic isolation chamber that day were included for analysis. Sixteen samples collected from 11 females (n = 7 CTR, 4 E2) met this criterion. In cases where two samples were collected from the same individual, their mean value was used for analysis. Plasma CORT was measured using an enzyme immunoassay kit from Enzo Life Sciences (ADI-900-097) with a six-point standard curve ranging from 2000 pg/mL to 3.9 pg/mL Samples were run at a 1:20 dilution with 1%(of raw plasma volume) steroid displacement buffer. Samples were run in duplicate on a single plate. The intra-plate coefficient of variation (based on a plasma pool) was 9.8% and assay sensitivity was 0.2 ng/mL

2.6. Quantifying reproductive condition

Ovary condition was scored on a scale from 1 to 6 as: 1, smooth, entirely regressed; 2, slightly granular appearance, some follicles may be visible; 3, small distinct follicles visible, but no follicular hierarchy evident; 4, follicles obvious, hierarchy evident; 5, large, yolky follicles evident; 6, yolky follicle ready for ovulation and/or egg in oviduct (Hahn, 1998). Intermediate scores (±0.5) were also given where appropriate. Most notably, cases in which yolk was visible in one or more small follicles, but there were no large yolky follicles, were scored as 4.5. Additionally, if follicles were visible, the diameter of the largest follicle was measured to the nearest 0.1 mm with dial calipers.

2.7. Micro-computed tomography scanning

After sacrifice, bird carcasses were stored at -20 °C until they were shipped to The University of Scranton and prepared for scanning. Prior to scanning at The University of Scranton, all femora and humeri were dissected free of soft tissue and placed in 70% ethanol at 4 °C. We then scanned the right (when available) femur and humerus from each bird vertically in a cylindrical sample holder (20 mm D × 65 mm H) at a voltage of 55 kV and an intensity of 45 μA using high-resolution (10 μm) micro-computed tomography scanning (μCT 80, Scanco Medical, Basserdorf, Switzerland). The volume of interest (VOI) for medullary bone analysis was centered at the mid-diaphysis and spanned ±0.75 mm of the length of each individual bone. In the case of 3 house finches (2 controls and 1 implanted), the right femora were unavailable for scanning due to use for a different protocol and, thus, the left femora were scanned. Finally, for one of the implanted house finches, neither femur was available for scanning.

Scanco Software (Scanco Medical, Baserdorf, Switzerland) was used to examine two-dimensional (2D) cross sections of each bone. Contour lines were manually drawn on these 2D cross sections to isolate medullary bone from cortical bone and define the VOI for three-dimensional (3D) analysis of medullary bone as well as cortical bone. Cortical bone was analyzed in order to determine if any observed effects of estrogen-treatment were specific to medullary bone or affected both bone tissue types, as studies have suggested that both tissue types may be important calcium reserves for eggshell production (e.g. Taylor and Moore, 1954). A Gaussian filter was applied to each image to remove noise and segmentation using a unique threshold for each bird was done to separate bone from non-bone. The 3D analysis provided quantitative measures of medullary bone in the femur and humerus from each bird, reported as the percentage of medullary bone relative to the total tissue volume in the VOI (BV/TV,%). Tissue mineral density of the medullary bone (TMD, mgHA/ccm) was also calculated in the femur and humerus from each bird. In addition, quantitative measures of cortical bone volume (Ct.BV), periosteal volume (Ps.V), and marrow volume (Ma.V) were calculated in the femur and humerus from each bird.

2.8. Statistics

Differences in medullary BV/TV, TMD, Ps.V, Ma.V, and Ct.BV in the Pine Siskins were determined using the Kruskall-Wallis statistic with a post hoc Dunn's test. Differences in CORT levels in Pine Siskins as well as differences in medullary BV/TV, TMD, Ps.V, Ma. V, and Ct.BV in the House Finches were examined using a Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical analyses were done using SPSS Predictive Analytics Software (PASW) Statistics 18 Release 18.0.2 and R (R Development Core Team, 2011). The post-Hoc Dunn's test was calculated manually. P values less than 5% were considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Estrogen influenced medullary bone quantity

We looked for evidence of medullary bone in 8 untreated (control, CTR) female House Finches and 3 estradiol-treated (E2) female House Finches. We found that E2 treated females had significantly greater medullary BV/TV as compared to the CTR females in both the femora (69.3 ± 9.1% versus 0.0 ± 0.0%, respectively, p < 0.05) and humeri (71.7 ± 7.6% versus 0.1 ± 0.2%, respectively, p < 0.05). Two CTR female House Finches had trace medullary BV/TV (less than 1% medullary BV/TV). All of the birds (E2 treated and CTR) had an ovarian stage of 3.5 or less and a maximum follicle size of less than or equal to 1 mm (Table 2) at the time of sacrifice.

Table 2.

Ovarian condition and maximum follicle size data for the female House Finches (HOF) and Pine Siskins (PS), who were classified into either a High Medullary BV/TV (≥65%) or Low Medullary BV/TV (≤50%) group.

| Bird ID | Ovarian Condition | Maximum Follicle Size (mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Medullary BV/TV (≥ 65%) | Low E2-1 HOF | 2 | <0.5 |

| Low E2-2 HOF | 2 | <0.5 | |

| Low E2-3 HOF | 2 | <0.5 | |

| High E2-1 PS | 2 | 0.4 | |

| High E2-2 PS | 2 | 0.6 | |

| High E2-3 PS | 2 | 1.0 | |

| CTR-1 PS | 4.5 | 1.9 | |

| Low E2-1 PS | 5.5 | 8.8 | |

| High E2-4 PS | 6 | 9.3 | |

| Low Medullary BV/TV (≤50%) | CTR-1 HOF | 2 | <0.5 |

| CTR-2 HOF | 2 | <0.5 | |

| CTR-3HOF | 2 | <0.5 | |

| CTR-4 HOF | 2 | <0.5 | |

| CTR-5 HOF | 3 | <0.5 | |

| CTR-6 HOF | 2 | <0.5 | |

| CTR-7 HOF | 3.5 | 1 | |

| CTR-8 HOF | 2 | <0.5 | |

| Low E2-2 PS | 2 | 0.5 | |

| CTR-2 PS | 2 | 1.2 | |

| Low E2-3 PS | 3 | 0.5 | |

| CTR-3 PS | 4 | 1.3 | |

| CTR-4 PS | 4.5 | 2.1 | |

| Low E2-4 PS | 4.5 | 2.0 | |

| CTR-5 PS | 4.5 | 2.0 | |

| CTR-6 PS | 4.5 | 2.0 | |

| CTR-7 * PS | 5.5 | 8.2 | |

| CTR-8 * PS | 5.5 | 8.3 |

Denotes females that had laid an egg within 24 h of sacrifice and had a large yolking follicle in the ovary at the time of necropsy.

Estrogen levels also had a significant impact on medullary BV/TV in the female Pine Siskins (Fig. 2). Medullary BV/TV in the femora of high E2 treatment birds was 240% of that in both the low E2 and CTR groups (p < 0.05, respectively) and there was no difference in medullary BV/TV between the low E2 and CTR groups. Medullary BV/TV in the humeri of high E2 treatment birds was 230% of that in the low E2 and 240% of that in the CTR groups (p < 0.05, respectively) and there was no difference in medullary BV/TV between the low E2 and CTR groups. Interestingly, medullary BV/TV varied considerably across the 16 females that we examined (Fig. 3), ranging from a high of 83% in the humerus from a high E2 female to a low of less than 1% in the femur from a low E2 female.

Fig. 2.

Medullary BV/TV in the a) femora and b) humeri from female Pine Siskins receiving a high dose of E2, a low dose of E2, or no exogenous estradiol (control, CTR) reported as a percentage of the control. Letters indicate groups with significant differences in medullary BV/TV (mean ± SD, p < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Two dimensional cross sectional images of the mid-diaphysis of the humerus of each female Pine Siskin studied showing the variation in medullary BV/TV across individuals from the a) High E2 (n = 4), b) Low E2 (n = 4), and c) Control, CTR (n = 8) groups.

In an effort to better understand the variability in medullary BV/TV, we sought to compare medullary BV/TV values to the information collected at necropsy regarding the ovarian condition of each bird (Table 2) and classified birds as having high medullary BV/TV (BV/TV greater than or equal to 65%) or low medullary BV/TV (BV/TV less than or equal to 50%). We found that, regardless of ovarian condition, all 4 high E2 females had high medullary BV/TV. In addition, one low E2 female who was about to lay an egg at the time of necropsy and one CTR female at ovarian stage 4.5 and maximum follicle size = 1.9 mm also had high medullary BV/TV. The remaining 10 female Pine Siskins had low medullary BV/TV. This was the case for 5 CTR and 2 low E2 females who had an ovarian condition less than or equal to 4.5 (the point at which yolk deposition is just beginning) and a maximum follicle size of less than or equal to 2.1 mm. Additionally, 2 low E2 females who had laid an egg within 24 h of sacrifice and had a large yolking follicle in their ovary at the time of sacrifice also had low medullary BV/TV.

3.2. Estrogen influenced medullary bone density

Not only did estrogen have an impact on medullary bone volume fraction, but it also impacted medullary TMD as well. Examining TMD in the House Finches did not yield between group comparisons since the majority of the CTR females lacked medullary bone. However, analysis was possible in the Pine Siskins, where TMD in both bones from the high E2 treatment group was 150% of that in both bones from the CTR (p < 0.05) groups (Fig. 4). No significant differences in TMD were found in either bone between the high E2 treatment and the low E2 treatment group nor in either bone between the low E2 treatment group or the CTR group.

Fig. 4.

Medullary TMD in the a) femora and b) humeri from female Pine Siskins receiving a high dose of E2, a low dose of E2, or no exogenous estradiol (control, CTR) normalized to the control. * indicate groups with significant differences in medullary TMD (mean ± SD, p < 0.05).

3.3. Estrogen and cortical bone quantity

Cortical bone morphology was compared between control and treated birds in both species to assess whether estrogen treatment also impacted cortical bone. In both species, there was no effect of estrogen treatment on cortical bone volume (p > 0.05; Table 3). Likewise, Ps.V and Ma.V were not affected by estrogen treatment in either species of bird (p > 0.05; Table 3).

Table 3.

Indices of cortical bone morphology in the femora and humeri from control and estrogen treated House Finches and Pine Siskins (mean ± SD).

| House Finches | Pine Siskins | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| CTR | Low-E2 | CTR | Low-E2 | High-E2 | ||

| Femur | Ps.V (mm3) | 2.03 ± 0.23 | 1.86 ± 0.31 | 1.28 ±0.08 | 1.31 ±0.11 | 1.33 ± 0.15 |

| Ma.V (mm3) | 1.41 ± 0.17 | 1.12 ± 0.30 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 0.82 ±0.12 | 0.83 ± 0.06 | |

| Ct.BV (mm3) | 0.52 ± 0.09 | 0.66 ±0.13 | 0.37 ± 0.08 | 0.38 ±0.11 | 0.41 ±0.11 | |

| Humerus | Ps.V (mm3) | 3.27 ± 0.28 | 3.18 ± 0.40 | 2.29 ±0.11 | 2.41 ±0.15 | 2.40 ±0.17 |

| Ma.V (mm3) | 1.99 ± 0.17 | 1.90 ± 0.35 | 1.40 ± 0.11 | 1.50 ±0.09 | 1.46 ± 0.05 | |

| Ct.BV (mm3) | 1.13 ± 0.15 | 1.18 ± 0.15 | 0.78 ± 0.10 | 0.81 ±0.10 | 0.84 ±0.13 | |

3.4. Estrogen treatment and plasma corticosterone

A plot of CORT concentration as a function of time to sample collection indicated no relationship between sampling time and CORT concentration within the 4 min window, so data from all samples were retained in the analysis. Circulating CORT levels did not differ significantly between CTR (mean ± 1 standard deviation: 4.84 ± 2.58 ng/mL) and E2 (4.02 ± 2.46 ng/mL) Pine Siskins (U = 16, n1 = 4, n2 = 7, p = 0.79). Moreover, females in both treatment groups laid eggs during the experiment, which is consistent with a lack of stress-induced reproductive suppression.

4. Discussion

Few studies on the endocrine regulation of medullary bone formation in birds have examined either non-domesticated species or species outside of the Galliformes, Anseriformes, and Columbiformes. Therefore, in this study we focused on the role of estradiol in medullary bone formation in wild-caught House Finches and Pine Siskins, non-domesticated species belonging to the order Passeriformes, the largest of the avian orders. Consistent with studies in other species, we found that estradiol treatment had a significant impact on the presence of medullary bone in both House Finches and Pine Siskins. Estradiol-treated House Finches had significantly more medullary bone than untreated females, who largely lacked medullary bone. Furthermore, all birds regardless of group had an ovarian stage less than or equal to 3.5 and a maximum follicle size less than or equal to 1.0. High medullary bone volume fraction (≥65%) was found in the Pine Siskins that received the higher dose of estradiol, regardless of ovarian stage or maximum follicle size in these high dose birds. Only two other Pine Siskins had high medullary bone volume. One of these had received a low dose of estradiol and was about to lay an egg at the time of sacrifice. The other did not receive estradiol treatment, and was at ovarian stage of 4.5 and had a maximum follicle size of 1.9 mm at the time of sacrifice (not unlike a number of birds with low medullary bone). The occurrence of high medullary bone volume in a control female is consistent with our interpretation that medullary bone development in the estradiol-treated females was not an artifact of a supraphysiological dose of estradiol as has been suggested to occur in rodents (Samuels et al., 1999). Low medullary bone volume fraction (≤50%) was found in the remaining Pine Siskins, the majority of which were at an ovarian stage ≤4.5 and had maximum follicle sizes of ≤2.0 mm. There were 2 exceptions to this finding and both females had just laid an egg within 24 h of sacrifice and had another large yolking follicle in the ovary at the time of sacrifice, thus they had low medullary bone volume fraction despite having ovarian stages higher than 4.5 and maximum follicle sizes greater than 2.0 mm. These data support the important influence of estradiol on the presence of medullary bone, and suggest an important time in the ovarian cycle (i.e., yolk deposition) when medullary bone formation appears to begin. Finally, our data suggest that at least some Passerines may rely on medullary bone, in part, as a source of calcium for eggshell formation.

Circulating corticosterone levels did not differ in estrogen-treated Pine Siskins versus untreated Pine Siskins, and, importantly, treated females did lay eggs. Thus, the increase in medullary bone seen in the treated females was not likely a result of stress, as has been reported in previous studies examining the impact of stress on medullary bone (Satterlee and Roberts, 1990). Stress has also been reported to affect cortical bone (Satterlee and Roberts, 1990; Urist and Deutsch, 1960), however our results indicate no differences in cortical bone quantity or morphology across the pine siskin treatment groups, again suggesting that differences in medullary bone do not reflect differences in stress levels across treatment groups. That cortical bone quantity did not differ between the treatment groups indicates that the effect of estradiol is specific to medullary bone. This finding is in contrast to previous studies in male Japanese quail (Turner et al., 1993) and laying hens (reviewed in Whitehead, 2004), in which elevated estrogen levels were associated with reduced cortical bone quantity and may suggest a different response to estrogen in these species. Alternatively, the findings could be a result of the estrogen dose that was used, the duration of the dose, or the fact that turnover rates are at least 10 times greater in medullary bone as compared to cortical bone due to a larger surface area in medullary bone (Hurwitz, 1965).

We found that females who had received a high estrogen dose had significantly greater medullary bone quantity, despite the fact that birds varied in their ovarian conditions (i.e., degree of follicular development) at the time of sacrifice. This finding suggests that sufficiently high estrogen levels can trigger medullary bone deposition regardless of the reproductive status of the female, and is consistent with studies in other species indicating that estrogens are a key signal responsible for stimulating medullary bone formation. Although we do not know the mechanism by which estrogen stimulated medullary bone formation in the Pine Siskins and House Finches, studies of Galliform birds point to osteoblasts as a key site of action for estrogens to stimulate medullary bone formation. Estrogen receptors have been identified on both preosteoblasts and osteoblasts found in medullary bone (Ohashi et al., 1991), with evidence suggesting that estrogens both stimulate osteoblast secretion of bone matrix and inhibit osteoclast resorption of medullary bone (Ohashi et al., 1990). Some studies have suggested the importance of androgens as well as estrogens in medullary bone production (Bloom et al., 1942), though other studies suggest that doses of estrogens above a threshold level are sufficient to trigger medullary bone development even in the absence of elevated endogenous androgens (Riddle et al., 1945). Since we did not block androgens in the present experiments, we cannot rule out a potentially synergistic role of endogenous androgens with the estradiol treatment. Additional work will be needed to more closely evaluate the potential role of androgens in medullary bone formation.

The timing of medullary bone formation relative to the formation of an egg has been examined by numerous studies. A cyclical pattern of medullary bone formation followed by resorption was reported in female pigeons during the reproductive cycle. This involved medullary bone formation up until the point when the egg reached the shell gland, at which point medullary bone resorption occurred until the time just after the first egg was laid and the second egg was ovulated, after which medullary bone formation would resume and again be prevalent until the 2nd egg reached the shell gland (Bloom et al., 1941; note that clutch size in pigeons is consistently only 2). Cellular evidence from actively laying hens supports this cyclic pattern, as osteoblasts were found to be more active (indicating bone formation) during the time when the egg was in the isthmus or magnum and osteoclasts were more active (indicating bone resorption) when the egg was in the shell gland and vagina (Kusuhara, 1975). The development of medullary bone in females during the breeding season appears to be associated with follicular development, with medullary bone appearing when follicles were at least 4.5 mm in size in pigeons (Kyes and Potter, 1934) and 18 mm in hens (Bloom et al., 1958). In the current study, our data suggest that, at least for the untreated females and those treated with low doses of estrogen, a critical point for medullary bone formation may be when follicles are approximately 2.0 mm in diameter and yolk deposition is commencing. Studies have shown that estradiol levels increase rapidly as yolk deposition begins in European Starlings (Williams et al., 2004). Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that testosterone levels peaked in the canary one day prior to the first egg being laid and remain high until incubation commenced (Schwabl, 1996). We therefore hypothesize that the commencement of yolk deposition may be an important point in the reproductive cycle for medullary bone formation in passerines.

The extent to which medullary bone contributes calcium to the formation of the eggshell is not readily clear, with only a few studies quantifying the calcium contribution from medullary bone. Studies in laying hens have suggested percentages ranging from as little as 10% (Deobald et al., 1936) to as much as 25–45% of the calcium needed for eggshell formation coming from medullary bone (Driggers and Comar, 1949; Mueller et al., 1964). Yet other studies have reported differences in the weight of bones suggesting that calcium reserves may be used for eggshell formation (Ankney and Scott, 1980), and some species make eggs while not feeding (e.g., Ankney and MacInnes, 1978). We found 2 female Pine Siskins who had low medullary bone volume fraction at the time of sacrifice despite having advanced follicular development. Both of these females had laid an egg within 24 h of sacrifice and both had another large yolking follicle in their ovary, suggesting that some medullary bone reserves may have been utilized to provide some of the calcium for eggshell formation and had not been replenished at the time of sacrifice. Future studies are needed in order to quantify the contribution of medullary bone calcium to the calcification of the eggshell in these passerines.

We have previously reported medullary bone in both wing bones (humerus and radius-ulna complex) and leg (tibiotarsusfibula complex) bones of 2 species of laying Passeriformes (Squire et al., 2011). In the current study we also found medullary bone in both the wing (humerus) and leg (femur) bones and furthermore, we found similar quantities of medullary bone in the mid-diaphyseal regions examined in both bones. Most studies have focused on examining medullary bone in leg bones (Bonucci and Gherardi, 1975; Ankney and Scott, 1980; Eeva et al., 2000), and those that have looked at wing bones have reported significantly less or no medullary bone in the humerus as compared to the femur (Clunies et al., 1992; Kim et al., 2004). This contrasting evidence may point to a difference in the manner in which medullary bone is used as a storage site and resource for calcium during the laying cycle in these particular species or in Passeriformes more generally.

In summary, we found that estrogen treatment influenced the quantity of medullary bone found in the long bones of female House Finches and Pine Siskins. This result is consistent with the results from the one other similar study in a Passeriform (Pfeiffer et al., 1940). Based on our results, we suggest that high estrogen levels may be sufficient to trigger formation of medullary bone in these birds, even when birds are not in full reproductive condition. Furthermore, we hypothesize that commencement of yolk deposition may be a critical time in the initiation of medullary bone formation in these passerine females. Overall, our finding that medullary bone formation was induced by elevated estrogen levels is similar to findings from other avian groups and is consistent with the hypothesis this is a highly conserved trait across the Aves. However, we note that our current understanding of this trait remains limited to just a very small representation of the diverse avian groups. Other areas where future studies are needed in order to deepen our understanding of the roles that hormones play in the initiation of medullary bone formation include studies on the precise timing of the initiation of formation, the extent of and manner by which calcium from medullary bone is used for eggshell formation in passerine birds, and the potential influence of body size on the use and regulation of medullary bone.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by the National Science Foundation (MRI # 0722751 to MES, IOS-0744705 to TPH, and IOS-1456954 to HEW) and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1F32HD056980 to HEW). We thank Jamie Cornelius, Deanna de Castro, and Wes Dowd for assistance in the field and laboratory, Dillan Patel for his assistance with the microCT analysis, Mary Lohuis and Bert Raynes for logistical support, and an anonymous reviewer for feedback on an earlier draft of this manuscript. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the NICHD or NIH.

References

- Acenzi A, Francois C, Bocciarelli D. On the bone induced by estrogens in birds. J Ultrastruct Res. 1963;8:491–505. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(63)80051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankney CD, MacInnes CD. Nutrient reserves and reproductive performance of female lesser snow geese. Auk. 1978;95:459–471. [Google Scholar]

- Ankney CD, Scott DM. Changes in nutrient reserves and diet of breeding brown-headed cowbirds. Auk. 1980;97:684–696. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom W, Bloom MA, McLeah FC. Calcification and ossification. Medullary bone changes in the reproductive cycle of female pigeons. Anat Rec. 1941;81:443–475. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom MA, McLean FC, Bloom W. Calcification and ossification. The formation of medullary bone in male and castrate pigeons under the influence of sex hormones. Anat Rec. 1942;83:99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom MA, Domm LV, Nalbandov AV, Bloom W. Medullary bone of laying chickens. Am J Anat. 1958;102:411–453. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001020304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonucci E, Gherardi G. Histochemical and electron microscope investigations on medullary bone. Cell Tissue Res. 1975;163:81–97. doi: 10.1007/BF00218592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazeal K. Proximate factors influencing timing and overlap of the breeding-molt transition in cardueline finches. 2014 http://gradworks.umi.com/36/46/3646257.html.

- Clunies M, Emslie J, Leeson S. Effect of dietary calcium level on medullary bone calcium reserves and shell weight of leghorn hens. Poult Sci. 1992;71:1348–1356. doi: 10.3382/ps.0711348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deobald HJ, Lease EJ, Hart EB. Studies on the calcium metabolism of laying hens. Poult Sci. 1936;15:179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Driggers JC, Comar CL. The secretion of radioactive calcium (Ca45) in the Hen's egg. Poult Sci. 1949;28:420–424. doi: 10.1126/science.109.2829.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eeva T, Ojanen M, Rasanen O, Lehikoinen E. Empty nests in the great tit (Parus major) and the pied flycatcher (Ficedula hypoleuca) in a polluted area. Environ Pollut. 2000;109:303–309. doi: 10.1016/s0269-7491(99)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LW, Shraer H. Keratan sulfate proteoglycan isolated from the estrogen-induced medullary bone in Japanese quail. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1982;72(2):227–232. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(82)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn TP. Reproductive seasonality in an opportunistic breeder, the red crossbill, Loxia curvirostra. Ecol. 1998;79:2365–2375. [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz S. Calcium turnover in different bone segments of laying fowl. Am J Physiol. 1965;208:203–207. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1965.208.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WK, Ford BC, Mitchell AD, Elkin RG, Leach RM. Comparative assessment of bone among wild-type, restricted ovulator and out-of-production hens. Br Poult Sci. 2004;45:463–470. doi: 10.1080/00071660412331286172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum A, Pfeiffer CA, van Heuverswyn L, Gardner WU. Studies on gonad-hypophyseal relationship and cyclic osseous changes in the english sparrow, Passer domesticus L. Anat Rec. 1939;75(2):249–263. [Google Scholar]

- Kusuhara S. Enzymohistochemical studies on the formation and resorption of bones in laying hens. Japanese J Zootech Sci. 1975;46(5):277–282. [Google Scholar]

- Kyes P, Potter TS. Physiological Marrow Ossification in Female Pigeons. Anat Rec. 1934;60:377–379. [Google Scholar]

- Landauer W, Zondek B. Observations on the structure of bone in estrogen-treated cocks and drakes. Am J Path. 1944;20(1):179–209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landauer W, Pfeiffer CA, Gardner WU, Shaw JC. Blood serum and skeletal changes in two breeds of ducks receiving estrogens. Endocrinology. 1941;28(3):458–462. [Google Scholar]

- Miller SC, Bowman BM. Medullary Bone osteogenesis following estrogen administration to mature male Japanese quail. Dev Biol. 1981;87:52–63. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MC. Effect of female sexual displays on the endocrine physiology and behaviour of male white-crowned sparrows, Zonotrichia leucophrys. J Zool. 1983;199:137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller WJ, Schraer R, Schraer H. Calcium metabolism and skeletal dynamics of laying pullets. J Nutr. 1964;84:20–26. doi: 10.1093/jn/84.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi T, Kusuhara S, Ishida K. Effects of oestrogen and anti-oestrogen on the cells of the endosteal surface of male Japanese quail. Br Poult Sci. 1987;28:727–732. doi: 10.1080/00071668708417008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi T, Kusuhara S, Ishida K. Electron microscopic observations of osteoblasts and osteoclasts on the medullary bone of tamoxifen-treated hens. Japanese Poultry Sci. 1990;27:122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi T, Kusuhara S, Ishida K. Estrogen target cells during the early stage of medullary bone osteogenesis: immunohistochemical detection of estrogen receptors in osteogenic cells of estrogen-treated male Japanese quail. Calcif Tiss Int. 1991;49:124–127. doi: 10.1007/BF02565134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl R, Winkler DW, Graveland J, Baiterman BW. Songbirds do not create long-term stores of calcium in their legs prior to laying: results from high-resolution radiography. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1997;264:239–244. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer CA, Gardner WU. Skeletal changes and blood serum calcium level in pigeons receiving estrogen. Endocrinology. 1938;23:485–491. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer CA, Kirschbaum A, Gardner WU. Relation of estrogen to ossification and the levels of serum calcium and lipoid in the english sparrow, Passer Domesticus. Yale J Biol Med. 1940;13(2):279–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prondvai E. Medullary bone in fossils: function, evolution and significance in growth curve reconstructions of extinct vertebrates. J Evol Biol. doi: 10.1111/jeb.13019. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prum RO, Berv JS, Dornburg A, Field DJ, Townsend JP, Lemmon EM, Lemmon AR. A comprehensive phylogeny of birds (Aves) using targeted next-generation DNA sequencing. Nature. 2015;526:569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature15697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: 2011. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- Riddle O, Rauch VM, Smith GC. Action of estrogen on plasma calcium and endosteal bone formation in parathyroidectomized pigeons. Endocrinology. 1945;36(1):41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels A, Perry MJ, Tobias JH. High-dose estrogen induces de novo medullary bone formation in female mice. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(2):178–186. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterlee DG, Roberts ED. The influence of stress treatment on femur cortical bone porosity and medullary bone status in Japanese quail selected for high and low blood corticosterone response to stress. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1990;95A(3):401–405. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(90)90239-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwabl H. Environment modifies the testosterone levels of a female bird and its eggs. J Exp Zool. 1996;276:157–163. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-010X(19961001)276:2<157::AID-JEZ9>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer MH, Wittmeyer JL, Horner JR. Gender-specific reproductive tissue in ratites and Tyrannosaurus rex. Science. 2005;308:1456–1460. doi: 10.1126/science.1112158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searcy WA, Capp MS. Estradiol dosage and the solicitation display assay in red-winged blackbirds. Condor. 1997;99:826–828. [Google Scholar]

- Simkiss K. Calcium Metabolism and Avian Reproduction. Biol Rev. 1961;36:321–367. [Google Scholar]

- Squire ME, Brague JC, Smith RJ, Owen JC. Evidence of medullary bone in two species of thrushes. Wilson J Ornithol. 2011;123(4):831–835. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor TG, Moore JH. Skeletal depletion in hens laying on a low-calcium diet. Br J Nutr. 1954;8(2):112–124. doi: 10.1079/bjn19540020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RT, Schraer H. Estrogen-induced sequential changes in avian bone metabolism. Calcif Tissue Res. 1977;24(1):157–162. doi: 10.1007/BF02223310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RT, Bell NH, Gary CV. Evidence that estrogen binding sites are present in bone cells and mediate medullary bone formation in Japanese quail. Poult Sci. 1993;72(4):728–740. doi: 10.3382/ps.0720728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urist MR, Deutsch NM. Effects of cortisone upon blood, adrenal cortex, gonads, and the development of osteoporosis in birds. Endocrinology. 1960;60:805–818. doi: 10.1210/endo-66-6-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Velde JP, Vermeiden JP, Bloot AM. Medullary bone matrix formation, mineralization, and remodeling related to the daily egg-laying cycle of Japanese quail: a histological and radiological study. Bone. 1985;6:321–327. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(85)90322-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts HE, Edley B, Hahn TP. A potential mate influences reproductive development in female, but not male, pine siskins. Horm Behav. 2016;80:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead CC. Overview of bone biology in the egg-laying hen. Poult Sci. 2004;83:193. doi: 10.1093/ps/83.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TD, Kitaysky AS, Vezina F. Individual variation in plasma estradiol-17 and androgen levels during egg formation in the European Starling Sturnus vulgaris: implications for regulation of yolk steroid. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2004;136:346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield JC, Farner DS. The annual cycle of plasma irLH and steriod hormones in feral populations of the white-crowned sparrow, Zonotrichia leucophrys gambelii. Biol Reprod. 1978;19:1046–1056. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod19.5.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield JC, Monk D. Behavioral and hormonal responses of male song sparrows to estradiol-treated females during the non-breeding season. Horm Behav. 1994;28:146–154. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1994.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambonin-Zallone A, Mueller WJ. Medullary bone of laying hens during calcium depletion and repletion. Calcif Tissue Res. 1969;4:136–146. doi: 10.1007/BF02279115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zondeck B. Impairment of anterior pituitary function by follicular hormone. Lancet. 1936;228:842–847. [Google Scholar]