Abstract

Tumor suppressor genes and their effector pathways have been identified for many dominantly heritable cancers, enabling efforts to intervene early in the course of disease. Our approach on the subject of early intervention was to investigate gene expression patterns of morphologically normal one-hit cells before they become hemizygous or homozygous for the inherited mutant gene which is usually required for tumor formation. Here, we studied histologically non-transformed renal epithelial cells from patients with inherited disorders that predispose to renal tumors, including von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease and Tuberous Sclerosis (TSC). As controls, we studied histologically normal cells from non-cancerous renal epithelium of patients with sporadic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). Gene expression analyses of VHLmut/wt or TSC1/2mut/wt versus wild-type (WT) cells revealed transcriptomic alterations previously implicated in the transition to precancerous renal lesions. For example, the gene expression changes in VHLmut/wt cells were consistent with activation of the hypoxia response, associated, in part, with the Warburg effect. Knockdown of any remaining VHL mRNA using shRNA induced secondary expression changes, such as activation of NF?B and interferon pathways, that are fundamentally important in the development of RCC. We posit that this is a general pattern of hereditary cancer predisposition, wherein haploinsufficiency for VHL or TSC1/2, or potentially other tumor susceptibility genes, is sufficient to promote development of early lesions, while cancer results from inactivation of the remaining normal allele. The gene expression changes identified here are related to the metabolic basis of renal cancer and may constitute suitable targets for early intervention.

Keywords: VHL, TSC1, TSC2, transcriptomics, primary kidney epithelial cells

INTRODUCTION

The discovery of tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) and their pivotal role in the etiology of hereditary cancer presents the opportunity to study phenotypically normal-appearing, histologically non-transformed target tissues, for possible intervention [1]. This approach may also lead to early intervention of clinically-identifiable pre-neoplastic lesions such as polyposis of the colon and squamous or basal skin cancers, wherein hundreds of lesions appear before progression to carcinoma [2]. While efforts to prevent lesion formation have not been entirely successful, the use of anti-inflammatory drugs, as one such example, can result in decreased tumor formation [3]. We chose to study two forms of hereditary kidney cancer, i.e., von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) and Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC), due to germline mutations of VHL or TSC1/2, respectively. Patients with VHL or TSC can develop hundreds of small benign renal lesions. In TSC, these lesions include angiomyolipomas, benign cysts, and renal cell carcinoma (RCC), all thought to be two-hit lesions, as is the case for angiofibromas (cortical tubers are still a matter of uncertainty) [4–6]. VHL is especially interesting because biallelic somatic inactivation of VHL occurs in the majority of sporadic (non-hereditary) RCCs [7, 8]. Therefore, our specific strategy has been to study histologically normal “one-hit” renal epithelial cells, i.e., heterozygous VHLmut/wt or TSC1/2mut/wt cells (referred to herein as VHL-single hit and TSC1/2-single hit cells) from affected kidneys of mutation carriers. Here, we report aberrant patterns of gene expression in non-transformed VHL- or TSC1/2-”one-hit” renal epithelial cells from patients with germline VHL or TSC1/2 mutations. Importantly, the transcriptional changes that are differentially observed in these cells are suggestive of metabolic alterations that cause an altered energy production by the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and glycolysis. Specifically, the investigations reported here uncover early transcriptional changes on the path to RCC that might provide targets for interventions. Correspondingly, transcriptional alterations have also been described in one-hit cells from target tissues of patients with dominantly inherited susceptibility to colon or breast cancers [9–11].

The high rate of somatic VHL mutations in sporadic kidney cancers, particularly clear cell renal cell carcinomas (ccRCC) suggests that inactivation of the VHL protein plays a critical role in the initiation of RCC in the general population [7, 8]. As noted, the affected adult kidney from VHL patients typically contains hundreds of very small tumors that do not metastasize [12], wherein removal of the whole kidney is not necessary, providing a window for effective intervention before progression to metastatic cancer.

TSC is caused by inactivation of either TSC1 or TSC2, leading to activation of the mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1). The TSG activity of TSC1 and TSC2 depends upon the interaction of their respective protein products [13–15].

Consistent with earlier findings [16], transcriptomic profiles of morphologically normal, non-transformed (MNNT) kidney epithelial cells carrying germline mutations of VHL or TSC1/2 are different from each other and from those of individuals not harboring a germline mutation (wild-type, WT) of these genes. The comparative expression profiling of kidney epithelial cells from WT, VHL-single hit, and TSC1/2-single hit individuals reported here may provide critical insights into renal oncogenesis, including deranged signaling pathways and altered intermediary metabolism. Importantly, the molecular alterations described here may serve as markers of early progression and aid in the development of novel intervention strategies.

RESULTS

Genome-wide transcriptome analysis

Our primary goal was to compare transcriptomes of MNNT renal epithelial cells harboring a mutation in one allele of VHL or TSC1/2, to monitor the earliest gene expression changes associated with one-hit inactivation of a given TSG [11, 16, 25]. To confirm that cultured cells from VHL patients retained their heterozygous status while grown in vitro, we performed VHL mutation analysis on five cultures. Four different monoallelic sequence variants were identified in four cultures: an in-frame deletion c.227_229delTCT was identified in cultures VHL-4 and VHL-5, whereas missense substitutions c.499C>T and c.473T>C were found in VHL-1 and VHL-6 cells, respectively (Supplemental Table 2; Supplemental Figure 1). Each change is pathogenic and previously reported in ccRCC or pheochromocytomas [26–29]. Additionally, a likely non-pathogenic missense substitution, c.21C>A, was identified in VHL-5. In each instance, the VHL mutation was heterozygous, with one allele being normal. In the fifth culture, no obvious VHL mutation was found, although clinical features of the corresponding patient were consistent with a diagnosis of VHL disorder. In each case, results in vitro conformed with those obtained upon admission of patients. Also, MNNT one-hit cells were obtained from six patients diagnosed with TSC1 or TSC2 based on distinctive clinical features, although mutational analysis is not available for this TSC1/2 patient group.

Next, we performed a global transcriptomic analysis on MNNT cells of VHL-single hit, TSC1/2-single hit, and WT individuals using Affymetrix U133plus2 chips that enabled better resolution of probesets [16]. Using a FDR cutoff of 20%, a total of 1,318 and 80 probe sets were differentially expressed between one-hit cells from VHL patients and WT controls (Supplemental Table 3), and between one-hit cells from TSC patients and WT controls (Supplemental Table 4), respectively. These probe sets correspond to a total of 1,036 differentially expressed genes for VHL cells and 62 differentially expressed genes for TSC cells. Figure 1 depicts a heatmap of genes differentially expressed between one-hit VHL or TSC and WT cells. We validated a fraction of the differentially expressed genes using real-time RT-PCR (Supplemental Tables 5, 6). Box plots depicting examples of differentially-expressed genes in VHL and TSC mutant cells are shown in Supplemental Figures 2 and 3, respectively.

Figure 1. Gene expression patterns, as heatmap, between VHLmut/wt and wild-type (WT) renal epithelial cells (A), and between TSC1/2mut/wt and WT renal epithelial cells (B) U, up-regulated; D, down-regulated.

Thus, comparative analyses of VHL one-hit (VHLmut/wt) vs. WT cells, and TSC one-hit (TSC1/2mut/wt) vs. WT cells revealed notable changes in the global gene expression, indicating that heterozygous germline mutations in VHL or TSC1/2 do indeed affect the expression profiles of MNNT renal epithelial cells.

Biological themes of VHL one-hit cells

To define biological themes, GO analysis was carried out on the 1,036 differentially expressed genes (571 down-regulated; 465 up-regulated) between VHL-single hit and WT cells, which revealed enrichment of several biological processes (Table 1). Genes up-regulated in VHL-single hit cells are involved in processes such as histone acetylation, oxidative stress and cell-redox homeostasis, including ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic processes. Conversely, down-regulated genes involved DNA damage response, cell cycle arrest, mitochondrial morphogenesis, induction of apoptosis, and TGF-β signaling (Table 1).

Table 1. Gene Ontology (GO) categories (biological processes) enriched for both up and down-regulated genes in one-hit VHL cells.

| GOBPID | Term | Genes |

|---|---|---|

| GO:0043981 | histone acetylation | MEAF6,PHF17,PHF16 |

| GO:0007093 | mitotic cell cycle checkpoint | ZWINT,RPS27L,CCNA2,CCNB1,BUB3 |

| GO:0034101 | erythrocyte homeostasis | FOXO3,ARNT,LYN,PRDX1,ACVR1B,SFXN1 |

| GO:0030099 | myeloid cell differentiation | FOXO3,ARNT,LYN,PSEN1,TGFBR2,CASP8,SCIN,ACVR1B,SFXN1,CDC42 |

| GO:0043161 | proteasomal ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process | ERLIN2,HSPA5,HSP90AB1,PSMA6,PSMA7,PSMD5,RAD23B,DERL1,CCNB1,BUB3 |

| GO:0009060 | aerobic respiration | IDH1,SDHB,UQCRH,CAT,SUCLG1 |

| GO:0045454 | cell redox homeostasis | PDIA6,DNAJC16,PDIA3,GSR,PRDX1,TXNDC12,SELT,PDIA4 |

| GO:0042542 | response to hydrogen peroxide | TXNIP,PRDX1,APTX,SLC8A1,CASP6,CAT |

| GO:0006979 | response to oxidative stress | TXNIP,IDH1,ARNT,PRDX1,APTX,PSEN1,SLC8A1,TPM4,CASP6,ATRN,CAT |

| GO:0006511 | ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process | UBE4B,ERLIN2,FBXO21,RNF144B,HSPA5,HSP90AB1,PSMA6,PSMA7,PSMD5,RAD23B,UBE2G1,DERL1,CCNB1,BUB3 |

| GO:0055114 | oxidation reduction | SLC25A13,KDM5B,HIBADH,EGLN3,COX15,CYP51A1,ALDH9A1,KDM1A,GLUD1,GSR,HADHA,HCCS,HGD,IDH1,MAOA,ALDH6A1,P4HA1,PRDX1,TXNDC12,RDH11,PCYOX1,KDM3B,OGFOD1,PECR,SDHB,SQLE,UQCRH,CYB5B,CAT |

| Downregulated Biological Processes | ||

| GO:0070584 | mitochondrion morphogenesis | DNM1L,COL4A3BP,OPA1 |

| GO:0000045 | autophagic vacuole assembly | ATG4B,C12orf44,ATG9A |

| GO:0008629 | induction of apoptosis by intracellular signals | CDKN1A,C16orf5,PML,UACA,AEN,CUL4A |

| GO:0046626 | regulation of insulin receptor signaling pathway | GRB14,PTPRF,RELA,TSC2 |

| GO:0032570 | response to progesterone stimulus | RELA,TGFB1,THBS1,FOSL1 |

| GO:0008286 | insulin receptor signaling pathway | AKT2,GRB14,PHIP,PTPRF,RELA,TSC2 |

| GO:0043536 | positive regulation of blood vessel endothelial cell migration | PDGFB,TGFB1,THBS1 |

| GO:0007179 | transforming growth factor beta receptor signaling pathway | LTBP2,MEN1,PDGFB,PML,TGFB1,TGFB1I1,THBS1,USP9Y,LTBP4 |

| GO:0001952 | regulation of cell-matrix adhesion | CDK6,RASA1,THBS1,TSC2 |

| GO:0007162 | negative regulation of cell adhesion | COL1A1,ARHGDIA,RASA1,TGFB1,THBS1 |

| GO:0010810 | regulation of cell-substrate adhesion | CDK6,COL1A1,RASA1,THBS1,TSC2 |

| GO:0009411 | response to UV | CDKN1A,MEN1,PML,ATR,TMEM161A,UACA,RELA |

| GO:0042770 | DNA damage response, signal transduction | CDKN1A,C16orf5,PML,ATR,UACA,AEN,FBXO31,CEP63 |

| GO:0006977 | DNA damage response, signal transduction by p53 class mediator resulting in cell cycle arrest | CDKN1A,C16orf5,PML,ATR,AEN |

| GO:0007050 | cell cycle arrest | CDKN1A,GAS2L1,MEN1,PML,MAPK12,TGFB1,THBS1,SESN2,CUL4A |

| GO:0031571 | G1/S DNA damage checkpoint | CDKN1A,PML,FBXO31 |

| GO:0031575 | G1/S transition checkpoint | CDKN1A,PML,TGFB1,FBXO31 |

| GO:0007064 | mitotic sister chromatid cohesion | PDS5B,NIPBL |

| GO:0030036 | actin cytoskeleton organization | SORBS3,FMNL2,DAAM1,FLNA,RND3,RHOG,PDGFB,CCDC88A,RAC2,RASA1,ROCK1,TSC2,CALD1,DIAPH3,PDLIM7,CYTH2,ARHGEF17 |

The enrichment analysis was done using GO-Stats package (Bioconductor). Categories were selected based on p-value cutoff < 0.01.

Importantly, several of the expression changes detected in VHL one-hit cells are consistent with the known biology of the VHL protein, including its role in the degradation of transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF1) under normoxic but not hypoxic conditions [8, 30].

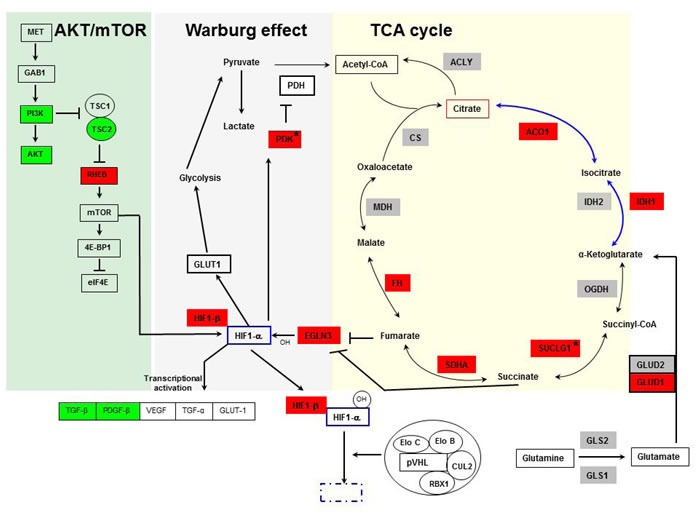

Using pathway analyses and data mining to evaluate the transcriptome of VHL-single hit cells, we found gene alterations involved in signal transduction, glycolysis and TCA cycle (Figure 2; Supplemental Figure 4). Signaling defects relevant to RCC involved MET, PI3K/AKT and HIF1α pathways. In VHL-single hit cells PIK3R2, AKT2 and TSC2 were down-regulated, whereas RHEB, encoding an activator of mTOR, was up-regulated. HIF1-mediated hypoxia signaling is critical in both sporadic and VHL-associated RCC subtypes. Although the HIF1α (HIF1A) and EPAS1 (HIF2A) genes were not differentially expressed, we found that the HIF1β (ARNT) gene is up-regulated in VHL one-hit cells. When stabilized either under hypoxia or pseudo-hypoxic conditions, together with HIF1β, HIF1α induces downstream target genes, e.g., VEGF, TGFA, TGFB, PDGFB and GLUT1. We also found that genes encoding TGFβ and PDGFβ, which are involved in angiogenesis and induction of growth hormone signaling, are down-regulated (Figure 2; Supplemental Figure 4); this may be because additional transcription factors, such as AP-1, are necessary for cooperation with HIF and induction of VEGF [31].

Figure 2. Pathways showing involvement of TCA cycle, Warburg effect, AKT-mTOR (yellow, gray and green background, respectively), and HIF in.

VHL-single hit cells. Genes depicted in green indicate down-regulation, and red indicate up-regulation in VHL-single hit cells vs. WT cells. Genes not colored and shown in gray color are not differentially expressed. VHL-single hit cells show partial activation of Warburg effect, whereby entry of pyruvate into TCA cycle is restricted due to activation of PDK, whereas other arm of the Warburg effect through HIF activation of glucose transporter and glycolysis is not active. mTOR-mediated transcriptional activation of HIF is active. *, genes experimentally validated.

Importantly, we found evidence for partial activation of the HIF pathway in VHLmut/wt cells, because its transcriptional target, EGL-Nine homolog 3 (EGLN3/PHD3) [32] is significantly overexpressed. EGLN3 and its family members serve as critical cellular oxygen sensors encoding proline hydroxylases involved in HIF1α degradation [32]. Under hypoxic conditions, increased expression of EGLN3 is necessary for survival and G1 to S transition of tumor cells [33], suggesting that in VHL-single hit cells a condition of modified steady state and feedback regulation exists that favors RCC development. Reduced activity of pVHL in VHL-single hit cells might lead to partial degradation of hydroxylated HIF1α, permitting limited stabilization of HIF1α leading to activation of its downstream targets. Consistent with this possibility, we observed overexpression of the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase gene (PDK), several TCA cycle genes, e.g., SDHB-encoding succinate dehydrogenase, and genes encoding components of the isocitrate dehydrogenase, reductive glutamine pathway, e.g., GLUD1, IDH1 and ACO1. Notably, PDK inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase and thereby blocks import of pyruvate into the TCA cycle [34, 35] (Figure 2).

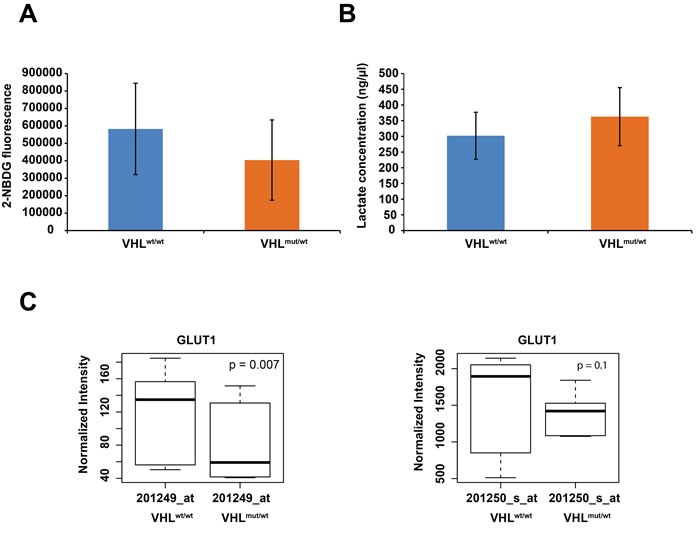

To verify the contention of partial activation of HIF1α targets in VHL one-hit cells, we determined if these cells show altered glucose uptake and lactate production. While we observed decreased glucose uptake in comparison to WT cells (Figure 3A), lactate production was increased (Figure 3B). These results are corroborated by our finding of reduced GLUT1 expression (Figure 3C), resulting in reduced glucose uptake. Overexpression of PDK1 (Figure 2) would inhibit decarboxylation of pyruvate mediated by pyruvate dehydrogenase, leading to increased lactate in the cytosol. These results suggest that in VHL-single hit cells, increased PDK expression and lactate production, but not glucose consumption, represents the initial events of the “Warburg effect”, whereas in the classic Warburg effect of two-hit VHLmut/mut cancer cells and, indeed, in essentially most cancers, both lactate production and glucose consumption are elevated.

Figure 3.

A. Summary of averaged 2-NBDG fluorescence, indicating glucose uptake for 5 WT and 5 VHL-single hit cultures. B. Summary of averaged lactate concentration for 5 WT and 5 VHL-single hit cultures. C. Box plots of differential GLUT1 expression between VHLmut/wt vs. WT cells, as determined with indicated Affymetrix probes.

Besides alterations in the expression of TCA cycle-related genes, we observed overexpression of PGK1, encoding phosphoglycerate kinase 1, a critical glycolytic enzyme that catalyzes conversion of 1,3-diphosphoglycerate to 3-phosphoglycerate. PGK1 also acts as an ‘angiogenic switch’ whereby overexpression of PGK1 reduces secretion of VEGF1 and IL8 through increased angiostatin, whereas, at metastatic sites, high levels of CXCL12 negatively regulate PGK1 expression, thereby enhancing angiogenic response for metastatic growth [36]. Interestingly, while PGK1 is overexpressed in VHL-single hit cells, CXCL12 is nearly 4-fold up-regulated (log2 1.9) in VHL-depleted cells (VHLknock-down; see below), suggesting the importance of VHL for its regulation.

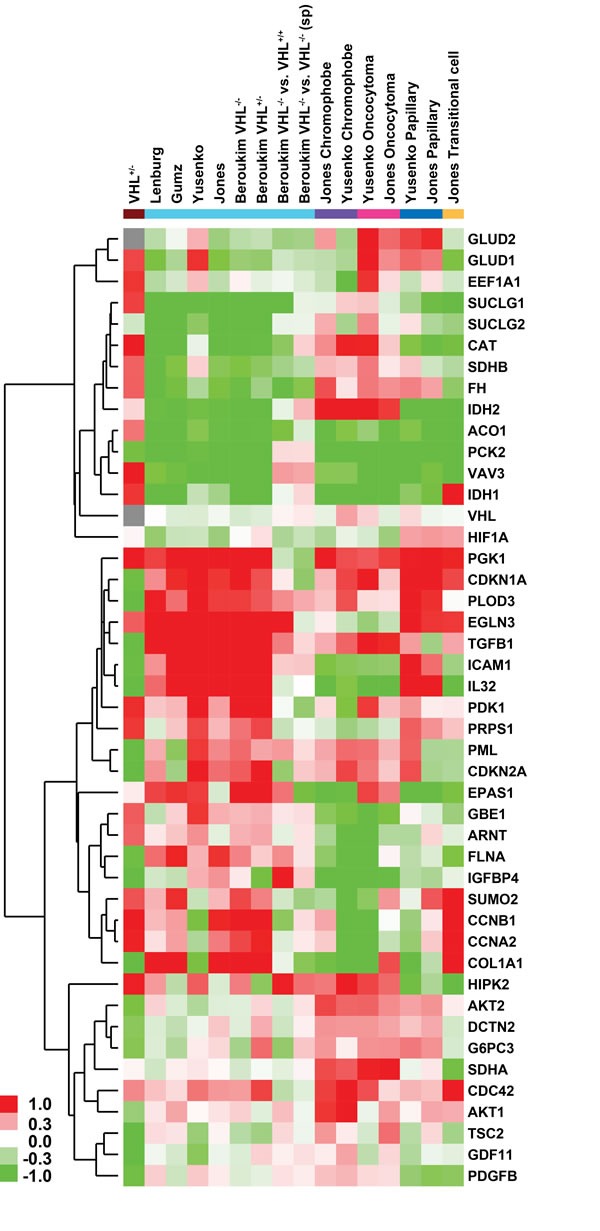

To delineate a common theme of differential gene expression patterns across published transcriptomic profiling studies of RCC subtypes and our non-transformed VHL-single hit kidney epithelial cells, we compared over- and under-expression of 45 genes involved in the Warburg effect, glycolysis, TCA cycle, and AKT/mTOR signaling (Figure 4). This analysis revealed that VHL-single hit cells exhibit a distinct gene expression profile, different from ccRCC tumor and WT cells. However, a similar over-expression pattern is observed for genes such as GLUD1, PGK1, EGLN3, PDK1, PRPS1, PCK2, GBE1, HIF1β, SUMO2, CCNB1, CCNA2, HIPK2 and CDC42 (Figure 4). Similar results were observed when we compiled a list of 268 genes that are known to be involved in these pathways (including HIF1α targets); of these, 189 genes can be compared across published studies in a heatmap (Supplemental Figure 5).

Figure 4. Heatmap of glycolysis, TCA cycle, HIF and AKT pathway genes depicting fold-changes in.

VHL-single hit cells and different kidney malignancies compared to their respective normal kidney epithelium (from studies in Supplemental Table 1). ccRCC, clear cell RCC; pRCC, papillary RCC; trans-cRCC, transitional cell RCC. Datasets normalized using RMA and LIMMA were used to calculate fold -changes (no p-value cutoff was enforced). Green and red color in heatmap indicates down- and up-regulation in RCC or VHLmut/wt cells, whereas gray indicates no fold change. Brown indicates VHL-single hit cells; cyan indicates studies of ccRCC, including comparisons based on VHL mutation status, a) among sporadic tumors with loss of two copies vs. one copy of VHL loss; b) VHL two-hit sporadic tumor vs. familial VHL loss cases; purple indicates chromophobe; magenta indicates oncocytoma; blue indicates papillary; and beige indicates transitional-cell RCC. Genes in matrix were hierarchically clustered (average linkage with uncentered Pearson correlation).

Transcriptomic profile of VHL-single hitVHL knock-down cells

If the expression changes in VHL-single hit cells represent an initial step during renal tumorigenesis, we hypothesized that rendering these cells VHL-null (i.e., two-hit inactivation) would further perturb their transcriptome and influence other causal mechanisms of transformation, as in ccRCC. We showed previously, through meta-analysis of multiple cancer datasets, that in a majority of ccRCC samples, NFκB is constitutively active, and that its key regulators and targets are uniformly up-regulated [37]. We also reported an enriched IFN signature in ccRCC [37]. Both NFκB and IFN gene sets are overexpressed in ccRCC samples where VHL is biallelically inactivated, but not in cells having functional VHL [37].

Thus, we knocked down the remaining VHL mRNA by infection with lentivirus-expressing VHL shRNA. The resulting cells, designated as VHL-single hitVHLknock-down, were profiled using expression arrays and compared to lentiviral vector-infected cells, designated VHL-single hitpLKOcontrol. Using a FDR cutoff of 20%, a total of 3,090 probe sets, corresponding to 2,018 genes, were differentially expressed between VHL-single hitVHLknock-down and VHL-single hitpLKOcontrol cells (Supplemental Table 7). Loss of any remaining VHL mRNA resulted in overexpression of 14 NFκB target genes. Of interest, IFNB1, BCL2A1 and IKBKE, each a direct target of NFκB and mediator of both canonical and non-canonical IFN signaling and innate immunity, were overexpressed upon loss of expression of the second copy of VHL (Supplemental Table 7).

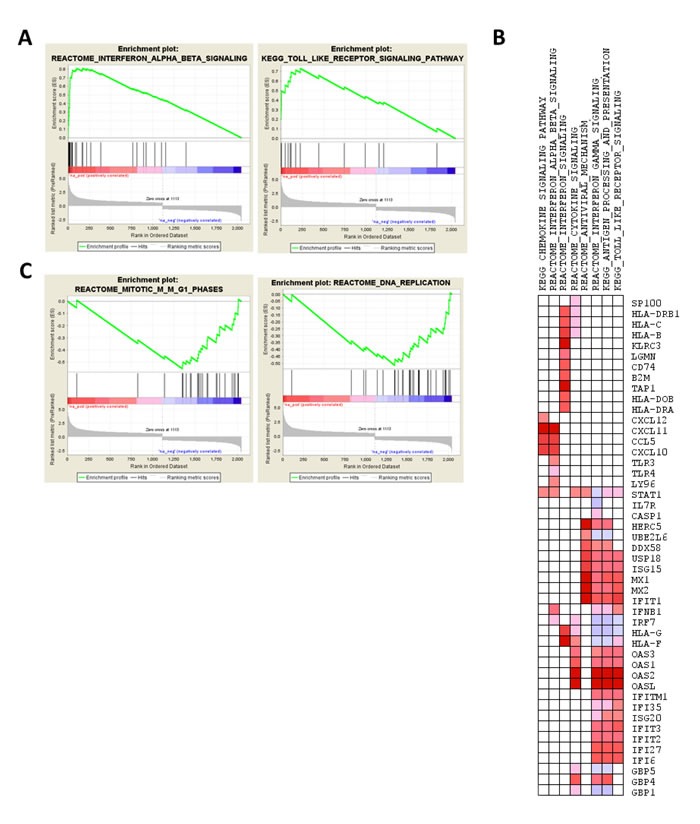

Analysis of GO categories (Supplemental Table 8) using GOstats package revealed enrichment of biological processes, including innate immunity and anti-viral signaling pathways. Similarly, enrichment analysis of pathways, using GSEA, indicated that interferon signaling, toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling (Figure 5A-5B) are enriched for overexpressed genes, whereas genes involved in cell cycle and replication are enriched for underexpressed genes in one-hit VHLknock-down cells (Figure 5C; Supplemental Table 9).

Figure 5. Enrichment analysis of the transcriptomic profile of.

VHL-null cells, i.e., comparison of VHL-single hitVHL knockdown vs. VHL-single hitpLKOcontrol. A. Enrichment plot for IFNB and TLR pathways. B. Pathways enriched for down-regulated genes (mitosis and DNA replication pathways in Reactome database). C. Leading edge analysis of up-regulated genes contributing to enrichment of pathway sets curated for interferon and anti-viral signaling pathways, depicted as heatmap (red and blue color indicate over- and underexpression of genes in VHL-single hitVHL knockdown cells).

Transcriptomic profiles of TSC mutant cells

Unlike VHL-single hit cells, only 62 genes (corresponding to 80 differentially expressed probesets) were differentially expressed in TSC1/2mut/wt cells, suggesting that monoallelic inactivation of TSC1 or TSC2 leads to a relatively small perturbation of the gene expression profile. GO analysis of differentially expressed genes (30 down-regulated; 32 up-regulated) revealed that genes involved in response to hydrogen peroxide and cell division are significantly up-regulated, whereas genes involved in T cell activation, regulation of G2/M transition, and reactive oxygen species are down-regulated (Table 2). Furthermore, compared to WT cells, TSC1/2-single hit cells showed down-regulation of multiple genes encoding endothelial markers and cell adhesion molecules, while several oncogenes, including ERBB4 and VAV3, were up-regulated (Supplemental Table 4). Dramatic loss (~25-fold) of expression of AQ-1, encoding water channel aquaporin, with preferential localization in the renal proximal convoluted tubules and the descending thin limb of the loop of Henle, was observed in TSC1/2-single hit cells. AQ-1 is considered a differentiation marker of proximal renal tubular cells and its down-regulation is associated with loss of the differentiated phenotype and poor prognosis in RCC [38]. Thus, these data provide additional evidence that some features of the clinical phenotype are already present in one-hit cells, in this case heterozygous TSC1/2mut/wt cells. Down-regulation of genes encoding endothelial markers, e.g., VCAM1, MCAM and THBD, was also observed. The WT1 gene, a TSG often mutated in pediatric Wilms’ tumor, was also down-regulated in TSC1/2-one-hit cells (Supplemental Table 4). WT1 negatively regulates the cell cycle and induces apoptosis through transcriptional regulation of the pro-apoptotic factor BCL2. WT1 also controls the mesenchymal-epithelial transition during renal development [39]. Altered expression of several of these genes was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR analysis (Supplemental Table 6).

Table 2. Gene Ontology (GO) categories (biological processes) enriched for both up and down-regulated genes in one-hit TSC1/2 cells.

| GOBPID | Term | a3 |

|---|---|---|

| GO:0010986 | positive regulation of lipoprotein particle clearance | LIPG |

| GO:0060074 | synapse maturation | ERBB4 |

| GO:0051301 | cell division | CAT,CCNA2,CCNG2,CDK1 |

| GO:0007095 | mitotic cell cycle G2/M transition DNA damage checkpoint | CCNA2 |

| GO:0043551 | regulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity | VAV3 |

| GO:0050847 | progesterone receptor signaling pathway | UBR5 |

| GO:0030518 | steroid hormone receptor signaling pathway | UBR5,MED14 |

| GO:0051973 | positive regulation of telomerase activity | PARM1 |

| GO:0042542 | response to hydrogen peroxide | ERBB4,CAT |

| GO:0009101 | glycoprotein biosynthetic process | MGAT4A,ST8SIA4,CHST9 |

| Downregulated biological processes | ||

| GO:0007568 | aging | CDKN2A,CRYAB,SERPINE1 |

| GO:0001300 | chronological cell aging | SERPINE1 |

| GO:0002691 | regulation of cellular extravasation | ICAM1 |

| GO:0022614 | membrane to membrane docking | ICAM1,VCAM1 |

| GO:0042110 | T cell activation | CDKN2A,ICAM1,VCAM1 |

| GO:0033079 | immature T cell proliferation | CDKN2A |

| GO:0032836 | glomerular basement membrane development | WT1 |

| GO:0010389 | regulation of G2/M transition of mitotic cell cycle | CDKN2A |

| GO:0031641 | regulation of myelination | CDH2 |

| GO:0000302 | response to reactive oxygen species | CRYAB,SERPINE1 |

The enrichment analysis was done using GO-Stats package (Bioconductor). Categories were selected based on p-value cutoff < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we identified altered gene expression patterns in cultured, MNNT one-hit renal epithelial cells of patients with VHL or TSC as compared to WT kidney epithelial cells. VHL and TSC are two of the ~10 phakomatoses that are characterized by dominant inheritance and scattered heterozygous precancerous lesions. These lesions are examples of haploinsufficiency for TSG mutations that may cause malignancy upon transition to the homozygous state [40].

Expression of genes involved in processes associated with the Warburg effect of aerobic glycolysis was altered in normal appearing VHL-single hit cells. However, this hypoxic response in VHL-single hit cells appears to be incomplete, since HIF1α activity was not associated with overexpression of some of its canonical downstream targets, such as VEGF and GLUT1. Yet overexpression of EGLN3, a transcriptional target of HIF1α [41, 42], does indicate that VHL-single hit cells are under hypoxic stress [41]. EGLN3 is involved in the G1>S transition in carcinoma cells [33] wherein its up-regulation is a direct response to hypoxia as a means for survival while under stress [33, 43]. Importantly, we did find increased expression HIF1β that is needed in order to confer stability and permit DNA binding of HIF1α, confirming our contention of the nature of events occurring early on in one-hit cells.

In further support of our contention of incomplete hypoxic response, while changes in expression levels of both HIF1α, HIF2α are not observed in our in vitro model, an in vivo mouse model of Vhl one-hit type 2B mutation (R167Q) shows low basal level expression in both these genes similar to cells with intact VHL, suggesting the pVHL in VHL one-hit cells does not stabilize HIF proteins. Interestingly, mice with Vhl one-hit type 2B mutation develop renal cysts and fail to progress to renal adenocarcinoma, suggesting VHL mutation alone is not sufficient for transformation [44].

In ccRCC, stabilization of HIF1α upon loss of VHL leads to activation of the Warburg effect through increased glucose uptake and lactate production, including restricted entry of pyruvate into mitochondria through activation of PDK1, a HIF1α target [34, 35]. Shunting of pyruvate away from the TCA cycle reduces levels of acetyl-coA, a glucose-derived carbon source for lipid biogenesis [45]. Interestingly, in vitro studies indicate that cancer cells supplement deficiency of acetyl-coA for lipid biogenesis through reductive glutamine metabolism mediated by cytoplasmic and/or mitochondrial IDH1 and IDH2, respectively [43, 44].

In VHL-single hit cells, we observed overexpression of PDK1, suggesting that the resulting inactivation of PDH would shunt pyruvate from mitochondria to cytosol with subsequent conversion of pyruvate to lactate. Indeed, we demonstrated increased lactate production in VHL-single hit cells (Figure 3B).

However, expression of GLUT1, a critical HIF1α target involved in the Warburg effect, is not elevated in VHL one-hit cells. In keeping with reduced expression of GLUT1, glucose uptake is lower in VHLmut/wt vs. WT cells (Figure 3A). Thus, increased lactate production, but not glucose uptake, conforms with our observation that VHLmut/wt cells are transcriptionally different from WT and ccRCC cells, and that they presumably represent the earliest phases of malignant transformation, i.e., cancer initiation (1). In this context, it should be noted that contrary to tumor cells, low glucose content in non-tumor cell lines has been shown to increase the stability of HIF1α [46].

Interestingly, we also observed that TCA cycle genes such as those encoding succinate-CoA ligase (SUCLG1), succinate dehydrogenase complex (SDHB), and fumarate hydratase (FH) are over-expressed in VHL-single hit cells. This suggests that, in these cells, like most non-malignant cells, the TCA cycle progresses largely towards acetyl-CoA in the oxidative state. Yet, in VHL-single hit cells we also observed overexpression of genes encoding cytosolic ACO1 and IDH1 - critical components of reductive glutamine metabolism - again suggesting that these cells, in addition to effective forward progression of the TCA cycle, have also activated an oncogenic metabolic shift that is seen in RCC, including a partial reversal of the TCA cycle.

To determine the effect of loss of the remaining functional allele of VHL in VHL-single hit cells, we depleted the remaining VHL mRNA using VHL shRNA lentiviral infection. Transcriptomic profiles of these VHL knockdown cells revealed overexpression of several direct targets/effectors of NFκB and IFN, including IRF7, STAT1, IFNB1 and IKBKE. Consistent with this, we recently reported overexpression of NFκB and IFN signaling in VHL-null ccRCC cells [37]. This is also consistent with studies showing that loss of VHL leads to activation of NFκB through CARD9, an agonist for NFκB [47].

Fewer changes were observed in TSC-mutant cells, indicating that heterozygosity for TSC1/2 has a lesser impact on transcription than monoallelic VHL mutations. TSC1 and TSC2 are negative regulators of AKT/mTOR signaling, and inhibitors of mTOR are efficacious in TSC patients. AKT/mTOR signaling is activated in many human cancers, including RCC [48]. Thus, it is possible that TSC1/2 haploinsufficiency is sufficient to shift cells toward the initiated state, which would further sensitize them to factors associated with malignant conversion.

In conclusion, analyses of primary cell cultures from kidneys of individuals with or without VHL or TSC1/2 mutations indicate that heterozygosity for TSG mutations is associated with detectable changes in gene expression that can be characterized as the initiated state in otherwise histologically normal cells. Many of these changes are consistent with the biology of homozygously-mutant RCC cells, thereby supporting the idea that gene alterations in one-hit cells represent relevant risk biomarkers and potential targets for therapeutic or preventive agents. We also note that since most non-hereditary ccRCCs are mutant for VHL, these results may be relevant to the management of this much larger group of renal cancers. Agents that reverse these pathways in VHL or TSC might be useful in the earliest stage of oncogenesis, perhaps even in preventing loss of the wild-type TSG allele in predisposed individuals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject accrual and specimens

All VHL, TSC and control (WT) subjects were recruited with the approval of the Fox Chase Cancer Center (FCCC) or National Cancer Institute (NCI) Institutional Review Board, and were chosen irrespective of gender, race and age. Specimens and accompanying information were de-identified. Individuals treated previously with chemotherapy or radiation were ineligible. Kidney biopsies were collected during surgery performed at NCI (VHL patients) and hospitals throughout the USA (TSC patients). As control tissues, we used normal renal epithelium adjacent to sporadic renal tumors from patients who underwent nephrectomy; these were designated WT, due to the absence of VHL or TSC1/2 mutations. In total, kidney epithelium was accrued from 6 VHL patients, 6 TSC1/2 mutation carriers, and 6 WT controls.

Establishment of primary kidney epithelial cell cultures

Preparation of early passage (2-5) renal epithelial cultures was as described [16]. They grew robustly in culture (doubling time, 48 h) and did not show overt signs of transformation; all cultures underwent senescence by passages 7-10. These renal epithelial strains are defined here as VHL-single hit (or VHL mutant), TSC-single hit (TSC mutant) and control (WT) cells. Cultures from mutation carriers were phenotypically indistinguishable from those derived from WT controls and did not differ with regard to proliferation rate or level of apoptosis [16].

VHL mutational analysis

To confirm that the primary cultures from VHL patients retained their “one-hit” status in vitro, we performed a VHL mutation analysis on five of them. Genomic DNA was extracted using the Gentra Puregene Tissue Kit (Qiagen), per the manufacturer's protocol. The complete coding sequence and flanking exon-intron borders of VHL were investigated by direct sequencing. PCR reactions were performed using PFU Turbo (Agilent) following cycling program: 95°C for 2 min; 35 cycles of (95°C 30 sec, 65°C 30 sec, 72°C 1 min); 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were gel-purified and sequenced using forward and reverse primers: preT7, (GGGAGGTCTATATAAGCAGa) and T3 (ATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGA), respectively. Mutation nomenclature is in accordance with HGVS (http://www.hgvs.org/mutnomen/) recommendations. VHL cDNA sequences (GenBank accession #NM_000551) are shown with A of the ATG translation-initiation codon numbered as +1.

VHL down-regulation in one-hit kidney epithelial cells

Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) lentiviruses targeting human VHL (named shVHL B2 and shVHL B4), with the sequences CAATGTTGACGGACAGCCTAT and TAGGATTGACATTCTACAGTT, were from Thermo Scientific OpenBio-Systems. Control lentivirus pLKO and shVHL B2 and shVHL B4 lentiviral constructs and appropriate packaging plasmids were transfected into 95% confluent 293T cells with the ViraPower™ Lentiviral Expression System (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). Supernatants were harvested 48 h after transfection and filtered through 0.45-μm pore filters (Millipore). Five primary VHL renal epithelial cell cultures were transduced with either control lentivirus (pLKO) or lentiviruses expressing shVHL B2 or shVHL B4 in the presence of 6 μg/ml polybrene (Santa Cruz) and analyzed 5-7 d after infection. Resulting strains are referred to as one-hit VHLpLKO control and one-hit VHLknock-down, respectively.

Immunoblotting

Protein extracts were prepared from cultured cells transiently transduced with shVHL B2, shVHL B4 or control shRNA, using RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 10 mM NaF, and 1 mM each of sodium pyrophosphate, sodium orthovanadate, dithiothreitol, and EDTA), plus protease inhibitors. Lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore). Membranes were blocked in 4% nonfat dry milk in TPBST and incubated with anti-VHL antibody from GeneTex, 1/1000 dilution in 4% nonfat dry milk in TPBST. Anti-β-actin (Sigma) was used as a loading control. Detection was performed using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham).

RNA extraction and amplification

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells using a guanidinium isothiocyanate-based buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol and acid phenol [11]. Amplification of total RNAs was with the one-cycle Ovation™ biotin system (NuGEN) [17].

Hybridization and microarray analysis

For each sample, 2.2 μg of ssDNA, labeled and fragmented using a NuGEN kit, was hybridized to Affymetrix arrays (Human U133 plus 2.0) as described [17]. After washing and staining with biotinylated antibody and streptavidin-phycoerythrin, arrays were scanned with an Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000 for data acquisition.

Real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) validation of microarray data

Validation of microarray findings was performed by real-time RT-PCR on microfluidic cards, TaqMan Low Density Arrays (LDA; Applied Biosystems). A 48-gene custom array (47 candidate biomarkers and 1 housekeeping gene, GAPDH) was from Applied Biosystems. This panel was tested for all samples in quadruplicate to ensure accuracy and reproducibility.

Data were obtained in the form of threshold-cycle number (Ct) for each candidate biomarker identified and GAPDH for each genotype (WT, VHL-single hit, TSC1/2-single hit). For each gene, Ct values were normalized to GAPDH, and the corresponding Ct values obtained for each genotype. Relative quantitation was computed using the Comparative Ct method (Applied Biosystems Reference Manual, Bulletin #2) between VHL or TSC1/2 mutants and WT primary cell RNAs. Relative quantitation is the ratio of normalized amounts of mRNA target for VHL, TSC1/2 and WT cells, and was computed as 2^(-Ct) where ∆Ct is the difference between mean Ct values for VHL or TSC1/2 mutant and mean ∆Ct values for WT RNAs.

Statistical analysis of microarray data

Primary cultures were analyzed for each genotype: VHL (VHLmut/wt), TSC (TSC1mut/wt or TSC2mut/wt), and WT (both VHLwt/wt and TSCwt/wt), using six biological replicates per experimental condition (total: 18 samples). For each sample, probe-level data in the form of raw signal intensities from Affymetrix arrays were preprocessed using the Robust Multi-chip Average (RMA) method [18].

Linear Models for Microarray Data (LIMMA) was used for class comparisons [19–21]. All comparisons were two-sided. The Benjamini-Hochberg method [22] was applied to control False Discovery Rate (FDR). Differentially expressed genes were identified based on statistical significance (FDR < = 20%) and biological significance (up- or down-regulated ≥ 2-fold) and validated using RT-PCR, with the analysis comparing five paired VHL shRNA- and control-infected primary VHL-single hit strains.

Mining for functional categories and pathways

Gene ontology (GO) functional categories, enriched in over- and under-expressed genes, were identified using conditional hyper-geometric tests in the GOstats package [23]. A p-value cutoff of 0.01 was used in selecting GO terms. Gene networks were generated using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis version 6.5 (Ingenuity® Systems, www.ingenuity.com). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) [24] was performed against lists of differentially expressed genes for VHL-single hit vs. WT, TSC-single hit vs. WT, and VHL-single hitVHL knock-down vs. VHL-single hitpLKO control comparisons. Gene sets from MSigDB [24], including positional, curated, motif and computational sets, were tested. Default parameters were chosen, except that maximum intensity of probes was selected while collapsing probe sets for each gene.

To discover a common theme of differential gene expression patterns across previously published transcriptomic profiling studies of RCC subtypes to that of VHL one-hit kidney epithelial cells, we obtained raw gene expression data from previous studies (Supplemental Table 1). The renal cancer subtypes evaluated were ccRCC, oncocytoma, chromophobe, papillary, transitional cell and Wilms’ tumor. Data were analyzed as previously outlined; and since the primary focus was on observing up- or down-regulation, no p-value or fold-change cutoffs were enforced.

Glucose uptake assay

Five WT and five VHL-single hit cultures were seeded in 6-well plates at ~70% confluency and incubated with serum-free, low glucose DMEM. 2-NBDG (2-(N-(7-Nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)Amino)-2-Deoxyglucose) (Life Technologies) was dissolved in sterile Milli-Q water at a concentration of 100 mM. After 24 h, cells were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with 2-NBDG (final concentration: 100 μM). 2-NBDG uptake reaction was stopped by removing the media and washing cells once with pre-chilled PBS. Cells were collected, centrifuged and resuspended in 500 μl PBS for flow cytometry analysis.

Lactate production assay

Lactate levels were quantitated from media of 5 WT and 5 VHL-single hit cultures, per Sigma's instructions. Cells were seeded on 6-well plates in ACL-4 complete media; after 24 h, cells were cultured in phenol red-free complete RPMI-1640 overnight; media was then removed from the cells and deproteinized with a 10-kDa MWCO spin filter to remove lactate dehydrogenase. The soluble fraction was assayed directly. Cells were trypsinized and counted for normalization of lactate concentration.

The authors would like to dedicate this article to the memory of Alfred G. Knudson, scientist, mentor and friend, who worked on the manuscript up to his final days and passed away shortly before submission. He will be missed greatly by us and by scientists and clinicians in the fields of oncology and cancer genetics all over the world.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS FIGURES AND TABLES

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH contract N01 CN-95037, NIH grant P30 CA-06927, FCCC Kidney Keystone Program, an appropriation from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. The Cell Culture, Genomics, and Bioinformatics & Biostatistics Facilities of FCCC provided expert assistance in this investigation.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this work.

Editorial note

This paper has been accepted based in part on peer-review conducted by another journal and the authors’ response and revisions as well as expedited peer-review in Oncotarget.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kopelovich L, Shea-Herbert B. Heritable one-hit events defining cancer prevention? Cell Cycle. 2013;12:2553–2557. doi: 10.4161/cc.25690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rustgi AK. Hereditary gastrointestinal polyposis and nonpolyposis syndromes. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1694–1702. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412223312507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boolbol SK, Dannenberg AJ, Chadburn A, Martucci C, Guo XJ, Ramonetti JT, Abreu-Goris M, Newmark HL, Lipkin ML, DeCosse JJ, Bertagnolli MM. Cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression and tumor formation are blocked by sulindac in a murine model of familial adenomatous polyposis. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2556–2560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang P, Cornejo KM, Sadow PM, Cheng L, Wang M, Xiao Y, Jiang Z, Oliva E, Jozwiak S, Nussbaum RL, Feldman AS, Paul E, Thiele EA, et al. Renal cell carcinoma in tuberous sclerosis complex. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:895–909. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai V, Parker WE, Orlova KA, Baybis M, Chi AW, Berg BD, Birnbaum JF, Estevez J, Okochi K, Sarnat HB, Flores-Sarnat L, Aronica E, Crino PB. Fetal brain mTOR signaling activation in tuberous sclerosis complex. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24:315–327. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tyburczy ME, Wang JA, Li S, Thangapazham R, Chekaluk Y, Moss J, Kwiatkowski DJ, Darling TN. Sun exposure causes somatic second-hit mutations and angiofibroma development in tuberous sclerosis complex. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:2023–2029. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latif F, Tory K, Gnarra J, Yao M, Duh FM, Orcutt ML, Stackhouse T, Kuzmin I, Modi W, Geil L. Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Science. 1993;260:1317–1320. doi: 10.1126/science.8493574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen C, Kaelin WG., Jr The VHL/HIF axis in clear cell renal carcinoma. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeung AT, Patel BB, Li XM, Seeholzer SH, Coudry RA, Cooper HS, Bellacosa A, Boman BM, Zhang T, Litwin S, Ross EA, Conrad P, Crowell JA, Kopelovich L, Knudson A. One-hit effects in cancer: altered proteome of morphologically normal colon crypts in familial adenomatous polyposis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7579–7586. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herbert BS, Chanoux RA, Liu Y, Baenziger PH, Goswami CP, McClintick JN, Edenberg HJ, Pennington RE, Lipkin SM, Kopelovich L. A molecular signature of normal breast epithelial and stromal cells from Li-Fraumeni syndrome mutation carriers. Oncotarget. 2010;1:405–422. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellacosa A, Godwin AK, Peri S, Devarajan K, Caretti E, Vanderveer L, Bove B, Slater C, Zhou Y, Daly M, Howard S, Campbell KS, Nicolas E, Yeung AT, Clapper ML, Crowell JA, et al. Altered gene expression in morphologically normal epithelial cells from heterozygous carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Cancer Prev Res. 2010;3:48–61. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walther MM, Lubensky IA, Venzon D, Zbar B, Linehan WM. Prevalence of microscopic lesions in grossly normal renal parenchyma from patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease, sporadic renal cell carcinoma and no renal disease: clinical implications. J Urol. 1995;154:2010–2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosner M, Hanneder M, Siegel N, Valli A, Fuchs C, Hengstschlager M. The mTOR pathway and its role in human genetic diseases. Mutat Res. 2008;659:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Slegtenhorst M, Nellist M, Nagelkerken B, Cheadle J, Snell R, van den Ouweland A, Reuser A, Sampson J, Halley D, van der Sluijs P. Interaction between hamartin and tuberin, the TSC1 and TSC2 gene products. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1053–1057. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.6.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plank TL, Yeung RS, Henske EP. Hamartin, the product of the tuberous sclerosis 1 (TSC1) gene, interacts with tuberin and appears to be localized to cytoplasmic vesicles. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4766–4770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stoyanova R, Clapper ML, Bellacosa A, Henske EP, Testa JR, Ross EA, Yeung AT, Nicolas E, Tsichlis N, Li YS, Linehan WM, Howard S, Campbell KS, et al. Altered gene expression in phenotypically normal renal cells from carriers of tumor suppressor gene mutations. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:1313–1321. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.12.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caretti E, Devarajan K, Coudry R, Ross E, Clapper ML, Cooper HS, Bellacosa A. Comparison of RNA amplification methods and chip platforms for microarray analysis of samples processed by laser capture microdissection. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103:556–563. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3:Article3. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.R Development Core Team . Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2005. A language and environment for statistical computing. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, Hornik K, Hothorn T, Huber W, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Falcon S, Gentleman R. Using GOstats to test gene lists for GO term association. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:257–258. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bellacosa A. Genetic hits and mutation rate in colorectal tumorigenesis: versatility of Knudson's theory and implications for cancer prevention. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;38:382–388. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maher ER, Webster AR, Richards FM, Green JS, Crossey PA, Payne SJ, Moore AT. Phenotypic expression in von Hippel-Lindau disease: correlations with germline VHL gene mutations. J Med Genet. 1996;33:328–332. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.4.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zbar B, Kishida T, Chen F, Schmidt L, Maher ER, Richards FM, Crossey PA, Webster AR, Affara NA, Ferguson-Smith MA, Brauch H, Glavac D, Neumann HP, et al. Germline mutations in the Von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) gene in families from North America, Europe, and Japan. Hum Mutat. 1996;8:348–357. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1996)8:4<348::AID-HUMU8>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woodward ER, Eng C, McMahon R, Voutilainen R, Affara NA, Ponder BA, Maher ER. Genetic predisposition to phaeochromocytoma: analysis of candidate genes GDNF, RET and VHL. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1051–1056. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.7.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dalgliesh GL, Furge K, Greenman C, Chen L, Bignell G, Butler A, Davies H, Edkins S, Hardy C, Latimer C, Teague J, Andrews J, Barthorpe S, et al. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature. 2010;463:360–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaelin WG., Jr The von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor protein: O2 sensing and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:865–873. doi: 10.1038/nrc2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Damert A, Ikeda E, Risau W. Activator-protein-1 binding potentiates the hypoxia-induciblefactor-1-mediated hypoxia-induced transcriptional activation of vascular-endothelial growth factor expression in C6 glioma cells. Biochem J. 1997;327:419–423. doi: 10.1042/bj3270419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.L del Peso, Castellanos MC, Temes E, Martin-Puig S, Cuevas Y, Olmos G, Landazuri MO. The von Hippel Lindau/hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway regulates the transcription of the HIF-proline hydroxylase genes in response to low oxygen. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48690–48695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hogel H, Rantanen K, Jokilehto T, Grenman R, Jaakkola PM. Prolyl hydroxylase PHD3 enhances the hypoxic survival and G1 to S transition of carcinoma cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim JW, Tchernyshyov I, Semenza GL, Dang CV. HIF-1-mediated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: a metabolic switch required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Cell Metab. 2006;3:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papandreou I, Cairns RA, Fontana L, Lim AL, Denko NC. HIF-1 mediates adaptation to hypoxia by actively downregulating mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Cell Metab. 2006;3:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang J, Wang J, Dai J, Jung Y, Wei CL, Wang Y, Havens AM, Hogg PJ, Keller ET, Pienta KJ, Nor JE, Wang CY, Taichman RS. A glycolytic mechanism regulating an angiogenic switch in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:149–159. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peri S, Devarajan K, Yang DH, Knudson AG, Balachandran S. Meta-analysis identifies NF-kappaB as a therapeutic target in renal cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takenawa J, Kaneko Y, Kishishita M, Higashitsuji H, Nishiyama H, Terachi T, Arai Y, Yoshida O, Fukumoto M, Fujita J. Transcript levels of aquaporin 1 and carbonic anhydrase IV as predictive indicators for prognosis of renal cell carcinoma patients after nephrectomy. Int J Cancer. 1998;79:1–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980220)79:1<1::aid-ijc1>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hosono S, Luo X, Hyink DP, Schnapp LM, Wilson PD, Burrow CR, Reddy JC, Atweh GF, Licht JD. WT1 expression induces features of renal epithelial differentiation in mesenchymal fibroblasts. Oncogene. 1999;18:417–427. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tucker M, Goldstein A, Dean M, Knudson A. National Cancer Institute Workshop Report: the phakomatoses revisited. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:530–533. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.7.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pescador N, Cuevas Y, Naranjo S, Alcaide M, Villar D, Landazuri MO, Del Peso L. Identification of a functional hypoxia-responsive element that regulates the expression of the egl nine homologue 3 (egln3/phd3) gene. Biochem J. 2005;390:189–197. doi: 10.1042/BJ20042121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schodel J, Oikonomopoulos S, Ragoussis J, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Mole DR. High-resolution genome-wide mapping of HIF-binding sites by ChIP-seq. Blood. 2011;117:e207–217. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-314427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su Y, Loos M, Giese N, Hines OJ, Diebold I, Gorlach A, Metzen E, Pastorekova S, Friess H, Buchler P. PHD3 regulates differentiation, tumour growth and angiogenesis in pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1571–1579. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee CM, Hickey MM, Sanford CA, McGuire CG, Cowey CL, Simon MC, Rathmell WK. VHL Type 2B gene mutation moderates HIF dosage in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 2009;28:1694–1705. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anastasiou D, Cantley LC. Breathless cancer cells get fat on glutamine. Cell Res. 2012;22:443–446. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dehne N, Hintereder G, Brune B. High glucose concentrations attenuate hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha expression and signaling in non-tumor cells. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:1179–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang H, Minamishima YA, Yan Q, Schlisio S, Ebert BL, Zhang X, Zhang L, Kim WY, Olumi AF, Kaelin WG., Jr pVHL acts as an adaptor to promote the inhibitory phosphorylation of the NF-kappaB agonist Card9 by CK2. Mol Cell. 2007;28:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Altomare DA, Testa JR. Perturbations of the AKT signaling pathway in human cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:7455–7464. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.