Abstract

Hypoadiponectinemia is associated with an increased risk of coronary artery disease. Although adiponectin replenishment mitigates neointimal hyperplasia and atherosclerosis in mouse models, adiponectin therapy has been hampered in a clinical setting due its large molecular size. Recent studies demonstrate that AdipoRon (a small-molecule adiponectin receptor agonist) improves glycemic control in type 2 diabetic mice and attenuates postischemic cardiac injury in adiponectin-deficient mice, in part, through activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). To date, it remains unknown as to whether AdipoRon regulates vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation, which plays a major role in neointima formation. In the present study, oral administration of AdipoRon (50 mg/Kg) in C57BL/6J mice significantly diminished arterial injury-induced neointima formation by ~57%. Under in vitro conditions, AdipoRon treatment led to significant inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-induced VSMC proliferation, DNA synthesis, and cyclin D1 expression. While AdipoRon induced a rapid and sustained activation of AMPK, it also diminished basal and PDGF-induced phosphorylation of mTOR and its downstream targets, including p70S6K/S6 and 4E-BP1. However, siRNA-mediated AMPK downregulation showed persistent inhibition of p70S6K/S6 and 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, indicating AMPK-independent effects for AdipoRon inhibition of mTOR signaling. In addition, AdipoRon treatment resulted in a sustained and transient decrease in PDGF-induced phosphorylation of Akt and ERK, respectively. Furthermore, PDGF receptor-β tyrosine phosphorylation, which controls the phosphorylation state of Akt and ERK, was diminished upon AdipoRon treatment. Together, the present findings suggest that orally-administered AdipoRon has the potential to limit restenosis after angioplasty by targeting mTOR signaling independent of AMPK activation.

Keywords: AdipoRon, AMPK, mTOR, PDGF, Vascular smooth muscle cells, Arterial injury

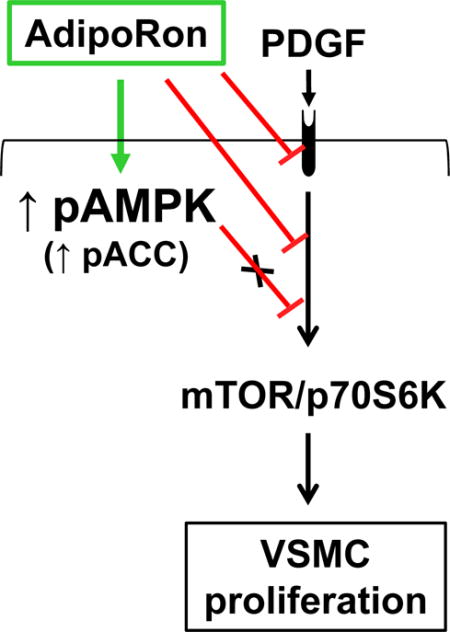

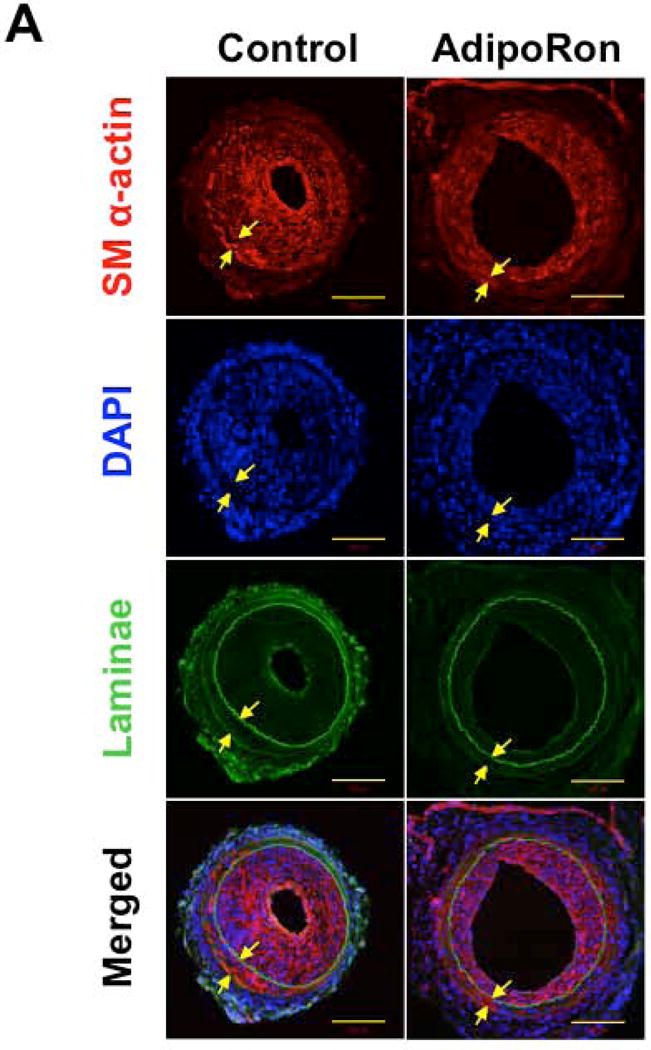

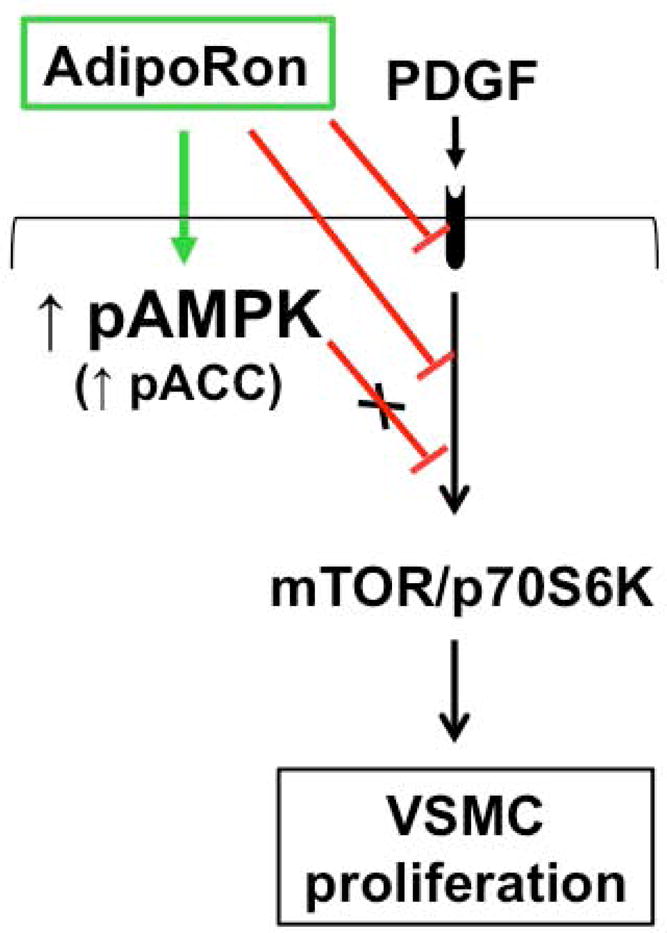

Graphical abstract

AdipoRon inhibits VSMC proliferation through AMPK-independent inhibition of mTOR/p70S6K signaling. AdipoRon activates AMPK and inhibits basal and PDGF-induced mTOR/p70S6K signaling. AMPK downregulation by target-specific siRNA shows persistent inhibition of mTOR signaling in VSMCs.

1. Introduction

Hypoadiponectinemia is closely correlated with insulin resistance and coronary artery disease [1–4]. In adiponectin-deficient mice, a decrease in the circulating concentration of adiponectin leads to insulin resistance and ~2-fold increase in neointima formation after arterial injury [5]. Of importance, adenovirus-mediated adiponectin delivery inhibits exaggerated neointima formation after arterial injury in adiponectin-deficient mice [6]. In addition, it attenuates atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice [7], suggesting a vasoprotective role for adiponectin. Nevertheless, the use of exogenous adiponectin as a rational therapy to reduce cardiovascular disease risk has been hampered in a clinical setting due to its large molecular size and short plasma half-life [8]. Recent studies demonstrate that oral administration of AdipoRon, a small-molecule adiponectin receptor agonist, improves insulin resistance and glycemic control in type 2 diabetic mice [9]. Furthermore, AdipoRon has been shown to attenuate post-ischemic myocardial apoptosis in adiponectin-deficient mice [10]. The beneficial effects of AdipoRon in skeletal muscle cells and cardiac myocytes have been attributed, in part, to activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [9,10]. To date, the likely regulatory effects of AdipoRon toward neointimal hyperplasia in vivo and vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation in vitro have not yet been examined.

The circulating adiponectin exists as globular adiponectin, full-length adiponectin, or oligomeric forms including low molecular weight (LMW), medium molecular weight (MMW), and high molecular weight (HMW) adiponectin [11]. Of importance, adiponectin exhibits its insulin-sensitizing action through adiponectin receptor-mediated AMPK activation in insulin responsive tissues such as skeletal muscle and liver [12]. Studies by Martin and co-workers demonstrate that in VSMCs, adiponectin-mediated AMPK activation leads to inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)/p70S6kinase (p70S6K) signaling thereby promoting a differentiation phenotype [13]. In addition, studies by several investigators, including our recent observations, reveal that AMPK-mediated inhibition of mTOR/p70S6K signaling contributes in part to attenuation of VSMC proliferation [14–16]. However, the role of AdipoRon on AMPK activation and the resultant effects on VSMC proliferative signaling remain unknown.

In addition to activating AMPK [13], adiponectin has been shown to suppress platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor signaling in VSMCs [6,17,18]. In this regard, HMW adiponectin diminishes PDGF-induced VSMC proliferation through direct interaction with PDGF-BB [17,18]. In addition, adiponectin inhibits the autophosphorylation of PDGF receptor-β and the phosphorylation of its downstream effector, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in VSMCs [17]. Nevertheless, the role of AdipoRon on PDGF-induced key proliferative signaling events, including mTOR, Akt, and ERK, remains to be examined in VSMCs.

In the present study, we therefore hypothesize that AdipoRon attenuates VSMC proliferation through activation of AMPK and/or inhibition of PDGF-induced mTOR signaling. The specific objectives are to determine the extent to which AdipoRon regulates neointimal hyperplasia in vivo and VSMC proliferation in vitro. Using C57BL/6J mice, this study has determined the effects of orally-administered AdipoRon on neointima formation after femoral artery injury. Using human aortic VSMCs, this study has also determined the effects of AdipoRon on: i) cell proliferation, DNA synthesis, and cyclin D1 expression; ii) phosphorylation state of AMPK and its downstream target, acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC); iii) PDGF-induced phosphorylation of mTOR and its downstream targets, including p70S6K/S6 ribosomal protein and 4E-BP1; iv) PDGF-induced mTOR signaling after target-specific downregulation of AMPKα1 isoform; v) PDGF-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (a downstream target of MEK1) and Akt (a downstream target of PI 3-kinase); and vi) PDGF receptor-β tyrosine phosphorylation and its association with p85 (an adapter subunit of PI 3-kinase).

2. Material and methods

2.1. Chemicals

AdipoRon was purchased from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI). Recombinant human PDGF-BB was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The primary antibodies for phospho-PDGFRβTyr751 (3161), PDGFRβ (3169), phospho-AMPKαThr172 (2535), pan-AMPKα (2532), phospho-ACCSer79 (11818), ACC (3676), phospho-C-RafSer338 (9427), C-Raf (12552), phospho-MEK1/2Ser217/221 (9154), MEK1/2 (8727), phospho-44/42 MAPK (pERK1/2; 4370), 44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2; 4695), phospho-AktThr308 (2965), phospho-AktSer473 (9271), Akt (4691), phospho-mTORSer2448 (5536), mTOR (2972), phospho-p70S6KThr389 (9234), p70S6K (2708), phospho-4E-BP1Ser65 (9451), 4E-BP1 (9644), phospho-S6 ribosomal proteinSer235/236 (4857), S6 ribosomal protein (2217), cyclin D1 (2922), β-actin (8457). GAPDH (5174), anti-rabbit IgG HRP-linked secondary antibody (7074), signal stain antibody diluent (8112), and signal stain boost IHC detection reagent (8114) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1706516) was purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). The primary antibody for p85 (05217) was purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). AMPKα1 silencer select siRNA and scrambled siRNA were purchased from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). Human aortic smooth muscle cells, vascular cell basal medium and vascular smooth muscle cell growth kit were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, Virginia). The primary antibody for smooth muscle α-actin was purchased from Abcam (ab5694; Cambridge, MA). The primary antibody for Ki-67 (RM-9106-S1) and Mayer’s hematoxylin (TA-125-MH) were purchased from Thermo Scientific (Wilmington, DE). Goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (A-11037) and prolong gold anti-fade mountant with DAPI (P36931) were purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). ImmPACT DAB peroxidase HRP substrate (SK-4105) was purchased from Vector laboratories (Burlingame, CA). All surgical tools were purchased from Roboz Surgical Instrument (Gaithersburg, MD). All other chemicals were from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ) or Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO).

2.2. Animals

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Charlie Norwood Veterans Affairs Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines and were approved by the committee. Male C57BL/6J mice (12 weeks of age, 24–25 g, Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were maintained in a room at a controlled temperature of 23°C with a 12:12-hr dark-light cycle. The mice had free access to water and rodent chow diet (8904; Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI).

2.3. Experimental protocol for AdipoRon treatment in mice

At 13 weeks of age, mice were divided into two groups. AdipoRon was suspended in 0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose and administered orally to the first group of mice (n = 7) at a dose of 50 mg/Kg/day for 21 days. A control group (n = 5) was kept in parallel where an equivalent volume of the vehicle was administered daily.

2.4. Femoral artery injury in mice

One day after AdipoRon or vehicle administration, left femoral artery injury was performed in all mice, as described [19,20]. In brief, the left femoral artery was exposed by dissection and the femoral nerve was carefully separated. A small branch between rectus femoris and vastus medialis muscles was isolated, ligated distally, and looped proximally. After topical application of a drop of 1% lidocaine, transverse arterioctomy was applied in the muscular branch. An incision was made to allow the insertion of a straight spring wire (0.38 mm in diameter, No. C-SF-15-15, Cook, Bloomington, IN) into the femoral artery. The wire was left for 1 min in place to denude and dilate the artery and then removed. Suturing was performed in the proximal portion of the muscular branch to restore the blood flow in the main femoral artery. Right femoral artery was used as sham control.

2.5. Tissue collection

On day 21 (after femoral artery injury), mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and then perfused via the left ventricle with 0.9% NaCl solution followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. The femoral artery was excised carefully and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1–2 days before being processed for frozen sections, as described [20].

2.6. Morphometric analysis of femoral artery

5 μm-thick cross-sections of the injured femoral artery were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and elastic van gieson (EVG). The images were taken by AxioCam high resolution camera (HRc) attached to an Observer Z1 microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Inc., Thornwood, NY) using 20x magnification power. Cross-sectional arterial microscopic images were analyzed for intima-to-media ratios within the middle portion of each lesion using image analysis software (Axiovision, release 4.8.2 SP3). The intimal area from each section was determined by subtraction of the lumen area from the internal elastic lamina (IEL) area. The medial area was determined by subtraction of the IEL area from the external elastic lamina (EEL) area, as described [20].

2.7. Immunofluorescence analysis of femoral artery

The cross sections of the injured femoral artery were subjected to immunofluorescence analysis for smooth muscle α-actin (SM α-actin) to confirm that the neointimal layer is composed of vascular smooth muscle cells. In addition, immunofluorescence analysis was performed for Ki-67, a marker of cell proliferation. The femoral artery sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and blocked by incubation with 5% normal goat serum for 1 hr. Subsequently, the sections were exposed to the primary antibody specific for SM α-actin (1:200 dilution) for 1 hr at room temperature or Ki-67 (1:30 dilution) overnight at 4°C. After washing 3 times with PBS, the sections were incubated with the secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa fluor 594 with red fluorescence). The cross-sections were then mounted using prolong antifade with DAPI and the images were captured using confocal microscope at 20x magnification power, as described [20].

2.8. Immunohistochemical analysis of femoral artery

The cross sections of the injured femoral artery were subjected to immunohistochemical analysis to examine the phosphorylation state of S6 ribosomal protein, a downstream target mTOR/p70S6K signaling. The femoral artery sections were fixed in 10% neutral buffer formalin and blocked by incubation with 5% normal goat serum for 1 hr. This was followed by incubation with the primary antibody specific for pS6 (1:75 dilution in signal stain antibody diluent) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing 3 times, hydrogen peroxide was added to block endogenous peroxidases and left for 10 min at room temperature. The sections were washed again 3 times and then incubated with signal stain IHC detection reagent for 30 min at room temperature. After intermittent washes, the sections were exposed to diaminobenzidine (DAB) working solution for 8 min. This was followed by counterstaining with Mayer’s hematoxylin. The sections were dehydrated by sequential immersions in 95% ethanol (2 times, 10 seconds each), 100% ethanol (2 times, 10 seconds each), xylene (2 times, 10 seconds each). They were then mounted using mounting medium (SP15-500, Fisher Scientific) and stored at room temperature. Images were captured using AxioCam high resolution camera (HRc) attached to an Observer Z1 microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Inc., Thornwood, NY) at 20x magnification power.

The intensity of pS6 staining in the neointima was quantified using Fiji software (ImageJ version 2.0.0-rc-15, National Institutes of Health). Reciprocal intensity, which was found to be directly proportional to antigen concentration, was calculated by subtracting the mean intensity in the neointimal area from the maximum intensity in white, non-stained background (250), as described [21].

2.9. Cell culture and treatments

Human aortic VSMCs were maintained in vascular cell basal medium, vascular smooth muscle cell growth supplement (SMGS), and antibiotic-antimycotic solution at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2, as described [22]. After the attainment of confluence (~7–10 days), VSMCs (passages 3–4) were trypsinized, and seeded onto 60 mm petri dishes. Subconfluent VSMCs were maintained in medium devoid of serum (SMGS) for 48 hr to achieve quiescence, and then subjected to treatments as described in the respective legends. DMSO (0.1%) was used as vehicle control for AdipoRon treatment.

2.10. Alamar blue assay

The effect of AdipoRon on VSMC proliferation was initially assessed using Alamar blue substrate, as described previously [23,24]. Serum-deprived VSMCs were incubated with increasing concentrations of AdipoRon (5, 25, 50 and 100 μM) for 96 hr. The medium and treatments were replenished at the 48 hr time point. The cells were exposed to Alamar blue (Invitrogen) during the last 4 hr. Alamar blue assay was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions by measuring fluorescence (excitation/emission: 560/590 nm) using a spectrophotometer.

2.11. Cell counts

The effects of AdipoRon on basal and PDGF-induced VSMC proliferation were determined by cell counts using automated counter (Invitrogen), as described [22]. Serum-deprived VSMCs were incubated with increasing concentrations of AdipoRon (5, 25, 50 and 100 μM) for 30 min, and then exposed to PDGF (30 ng/ml) for 96 hr. The medium and treatments were replenished at the 48 hr time point. After 96 hr, the cells were washed twice with PBS, trysinized, and then counted.

2.12. DNA synthesis

The effects of AdipoRon on basal and PDGF-induced DNA synthesis were determined using click iT® EdU microplate assay according to manufacturer’s instructions (Life technologies), as described [15]. Serum-deprived VSMCs were incubated with Adiporon (50 μM) for 24 hr and then exposed to PDGF (30 ng/ml) for the next 24 hr. During the last 18 hr of treatments, VSMCs were incubated with 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU; a nucleoside analog). Subsequently, cells were exposed to the supplied fixative reagent followed by labeling of EdU with green-fluorescent Oregon Green® azide. Signal amplification was achieved by incubation with HRP-conjugated anti-Oregon Green® antibody followed by reaction with Amplex® UltraRed substrate that produces a bright red fluorescent product (excitation/emission: 568/585 nm).

2.13. Immunoblot analysis

VSMC lysates (20 μg protein per lane) were subjected to electrophoresis using precast 4–12% NuPage mini-gels (Life Technologies), as described [22]. The resolved proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (EMD Millipore). Subsequently, the membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat milk and probed with the respective primary antibodies. The immunoreactivity was detected using HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (7074; Cell Signaling) followed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). β-actin or GAPDH was used as internal controls. The protein bands were quantified using ImageJ.

2.14. Immunoprecipitation studies

Serum-deprived VSMCs were incubated with AdipoRon (50 μM) for 48 hr followed by exposure to PDGF (30 ng/ml) for 2 min. VSMC lysates were obtained using 1x RIPA buffer with protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (524629, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) The lysates were vortexed and then centrifuged at 5000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants (200 μg protein) were incubated with anti-p85 primary antibody (1:50 dilution) overnight at 4°C, with continuous mixing. The antigen-antibody complexes were subjected to immunoprecipitation by mixing with magnetic beads (50 μL per sample) for 30 min at room temperature. After discarding the supernatants, the beads were washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% tween 20 (PBS-T). Elution step was performed by mixing the beads with 2x Laemmli buffer containing dithiothreitol and bromophenol blue and heating at 90°C for 10 min. The eluted samples were then used for immunoblotting.

2.15. Nucleofection of VSMCs with AMPKα1 siRNA

Subconfluent VSMCs were transfected with 500 pmoles of target-specific Silencer Select Pre-Designed siRNA (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) using Amaxa Nucleofector-II device U-025 program (Lonza, Germany). Scrambled siRNA- and target-specific AMPKα1 siRNA-transfected VSMCs were incubated in complete medium for 48 hr. Subsequently, VSMCs were deprived of serum for 24 hr and then subjected to treatments as described in the figure legend.

2.16. Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the means ± SEM. Statistical significance was tested using unpaired student t-test for morphometric analyses, AMPK α1 expression, and Akt, ERK and PDGFR-P phosphorylation (where only PDGF (0 μM AdipoRon) and PDGF (25 or 50 μM AdipoRon)-treated conditions were compared since the protein bands under control conditions were at undetectable intensities). One-way ANOVA and repeated measures one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons tests were used for testing significance in concentration- and time-dependent studies, respectively. Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons tests were used for all other results in the study. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For siRNA data, the effects of AdipoRon treatment (AdipoRon versus vehicle) and PDGF exposure (PDGF versus control) were compared using regular two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons test for each siRNA (Scr. and AMPK α1) separately. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc. V6.0f, San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Oral administration of AdipoRon attenuates neointima formation after arterial injury in mice

Recent studies by Okada-Iwabu et al. have shown that oral administration of AdipoRon (50 mg/Kg) in C57BL/6 mice results in a maximal plasma concentration of ~12 μM [9]. In the present study, a similar treatment protocol was followed in C57BL/6J mice by administering AdipoRon orally (50 mg/Kg) for 21 days.

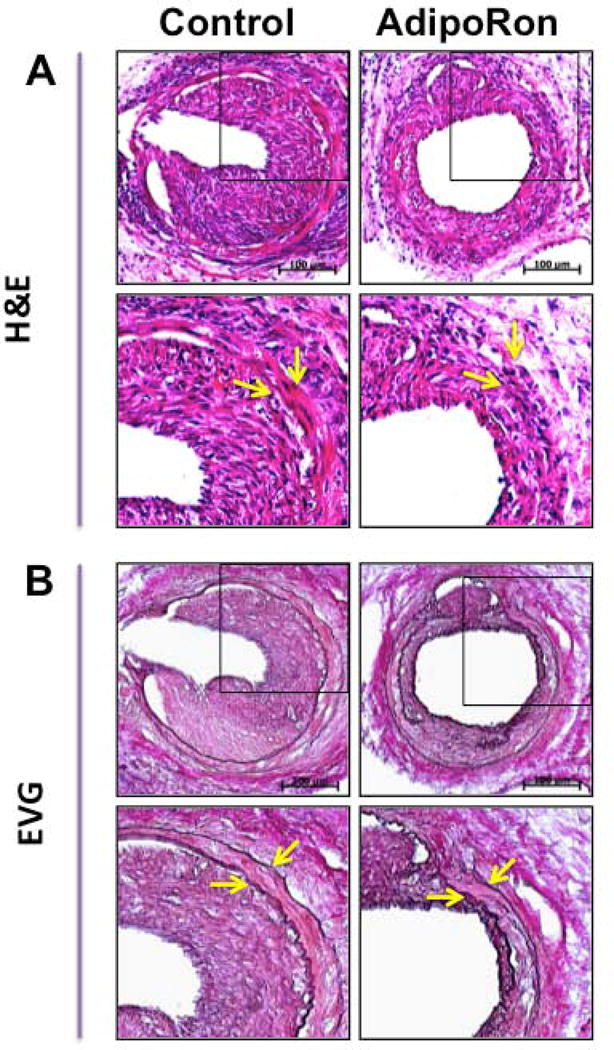

As shown in Fig. 1A–B, H&E- and EVG-stained sections revealed a marked decrease in neointima formation in the injured femoral artery from AdipoRon-treated mice. In addition, morphometric analyses showed significant decreases in intima/media ratio and intimal area by ~63.2% and ~57.5%, respectively, in AdipoRon-treated group (Fig. 1C). There were no significant differences in the medial layer and lumen area between control and AdipoRon-treated groups (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Effects of AdipoRon on injury-induced neointima formation in mouse femoral artery. AdipoRon was administered orally (50 mg/Kg) a day before femoral artery injury and for the following 21 days until sacrifice. Femoral artery sections from AdipoRon- and vehicle-treated (Control) mice were then subjected to: A) Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E); and B) Elastic Van Gieson (EVG) staining. The arrows indicate internal and external elastic laminae; scale bars represent 100 μm. C) Morphometric analyses of injured femoral arteries that include intima/media ratio and intimal area. The data shown are the means ± SEM. * p < 0.05; n = 5 to 7 mice/group.

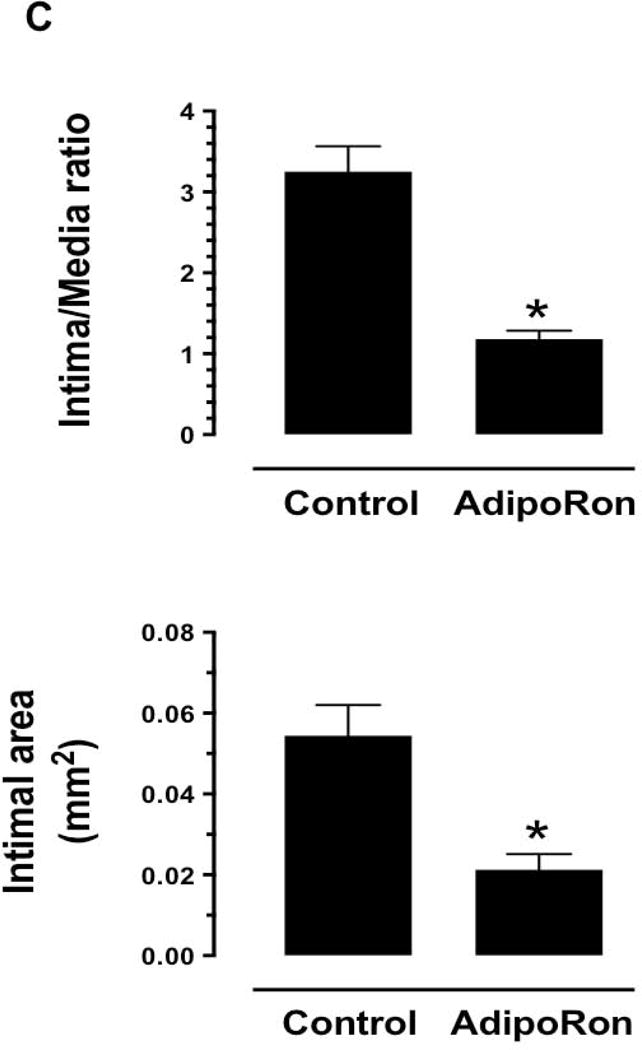

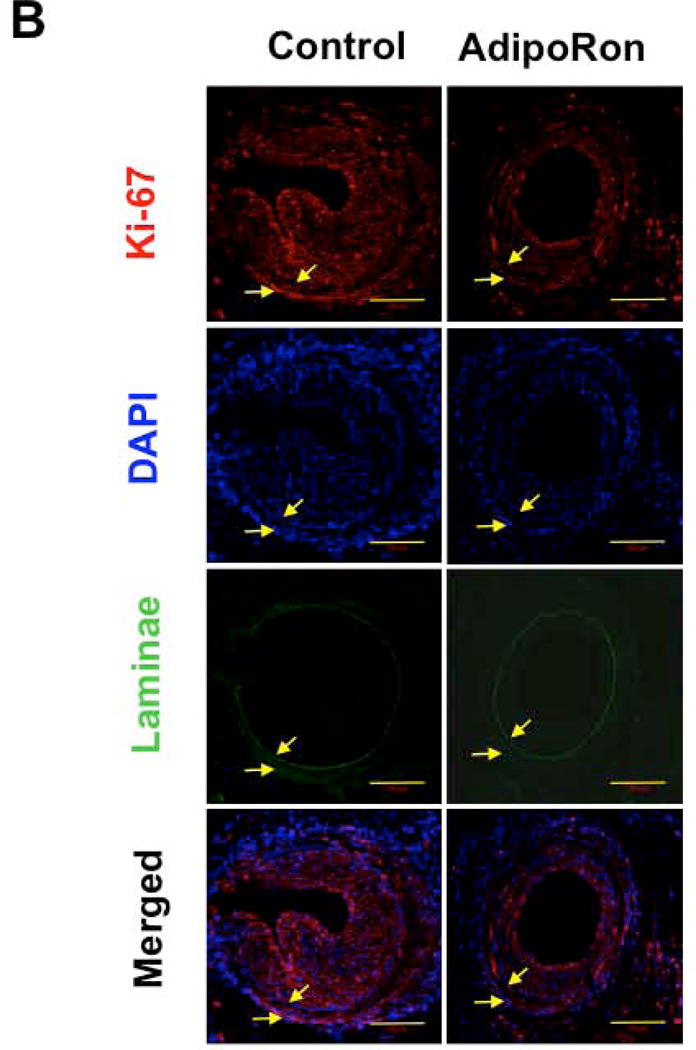

Immunofluorescence analysis of injured femoral artery sections showed a marked decrease in smooth muscle cells in the neointimal layer in AdipoRon-treated group, as revealed by SM α-actin immunoreactivity (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, AdipoRon treatment resulted in a marked decrease in Ki-67 immunoreactivity, a marker of cell proliferation (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Effects of AdipoRon on smooth muscle α-actin and Ki-67 immunoreactivity in the injured femoral artery. Confocal immunofluorescence analyses show the images for A) smooth muscle (SM) α-actin and B) Ki-67 (in red). The representative images for nuclei (DAPI, blue), elastin autofluorescence (laminae, green), and merged staining are also shown. The arrows indicate internal and external elastic laminae; scale bars represent 100 μm.

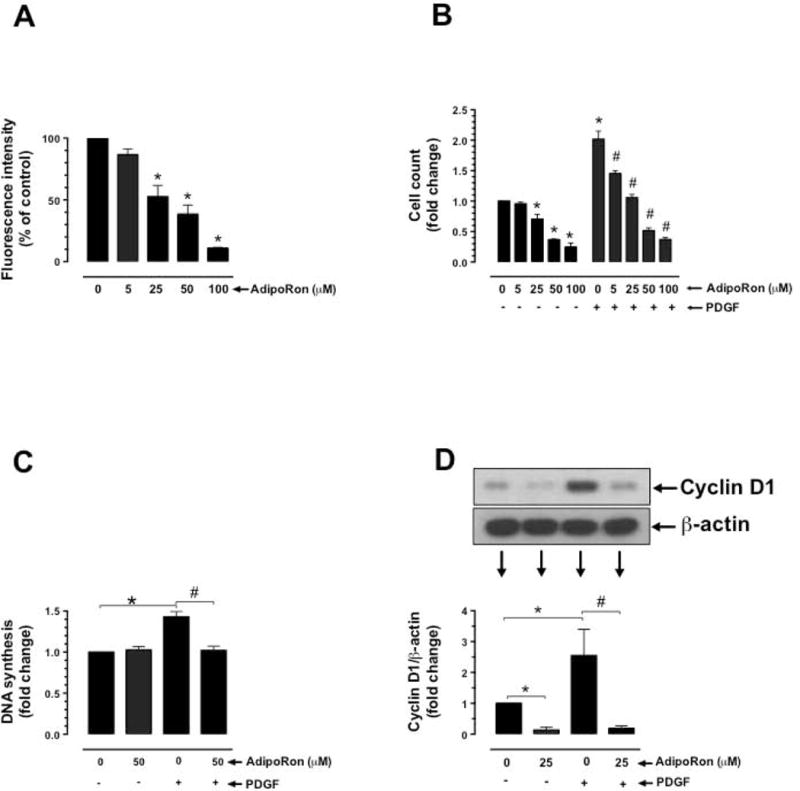

3.2. AdipoRon inhibits basal and PDGF-induced VSMC proliferation

Previous studies have shown that adiponectin inhibits VSMC proliferation induced by PDGF-BB, a potent mitogen [6,17,18]. To determine the likely regulatory effects of AdipoRon on VSMC proliferation, serum-deprived VSMCs were incubated with AdipoRon at the indicated concentrations (5–100 μM) and time intervals with and without PDGF-BB exposure. AdipoRon concentrations in the range of 1–50 μM have been used in recent studies with rodent skeletal muscle arteries and cells [9,25]. In the present study with human aortic VSMCs, there were significant decreases in cell number with AdipoRon treatment alone at 25 to 100 μM concentrations, as revealed by Alamar blue assay and cell counting using automated counter (Fig. 3A and B). PDGF-induced VSMC proliferation was diminished by > 60% upon AdipoRon treatment at 5 to 100 μM concentrations. Furthermore, PDGF-induced increases in DNA synthesis and cyclin D1 expression were suppressed by AdipoRon pretreatment at the indicated concentrations (Fig. 3C and D).

Fig. 3.

Effects of AdipoRon on basal and PDGF-induced VSMC proliferation. Serum-deprived VSMCs were incubated with: A) increasing concentrations of AdipoRon (5 to 100 μM) for 96 hr to determine the changes in Alamar blue fluorescence (n = 8); B) AdipoRon (5 to 100 μM) for 30 min followed by exposure to PDGF (30 ng/ml) for 96 hr to determine the changes in cell counts (n = 5); C) AdipoRon (50 μM) for 30 min followed by exposure to PDGF (30 ng/ml) for 24 hr to determine the changes in DNA synthesis (n=3); and D) AdipoRon (25 μM) for 30 min followed by exposure to PDGF (30 ng/ml) for 48 hr to determine the changes in cyclin D1 expression (n = 5). β-actin was used as an internal control. The data shown are the means ± SEM. *, # p < 0.05 compared with control (− PDGF and/or 0 μM AdipoRon) or PDGF (+ PDGF and 0 μM AdipoRon), respectively, using one-way ANOVA (A) or two-way ANOVA (B, C and D) followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons test.

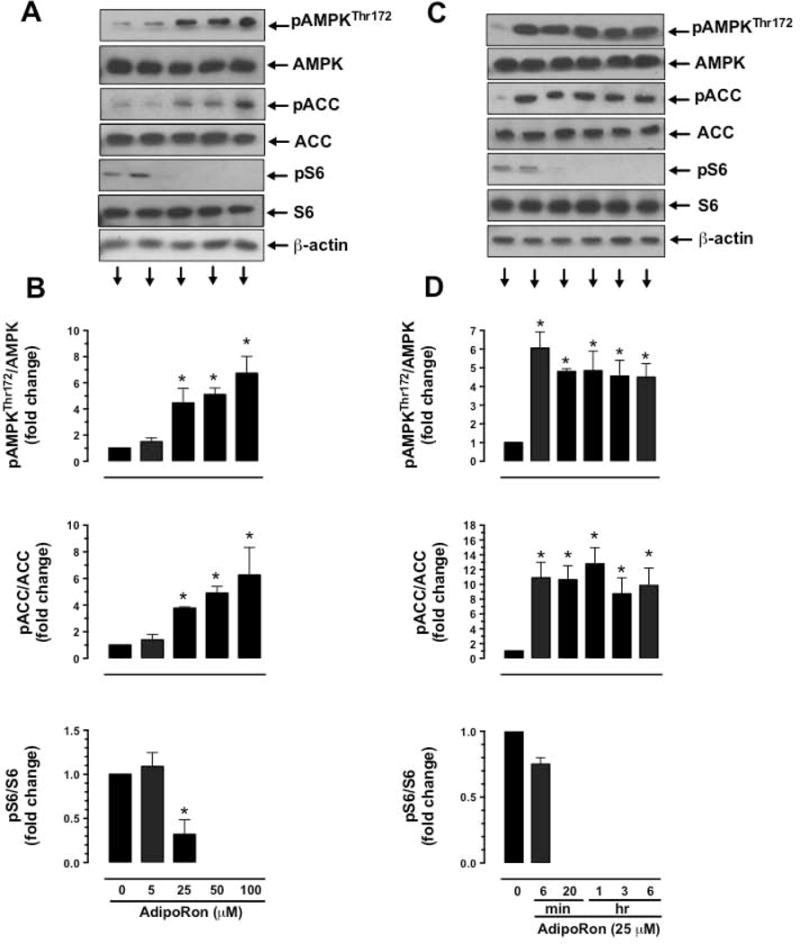

3.3. AdipoRon enhances AMPK and ACC phosphorylation with an accompanying decrease in S6 phosphorylation in VSMCs

To determine the effects of AdipoRon on AMPK activation, concentration and time-dependent studies were performed to quantify AdipoRon-mediated changes in the phosphorylation state of AMPK and its downstream target, ACC. To determine the relationship between AMPK activation and mTOR signaling, these studies quantified the changes in the phosphorylation state of S6 ribosomal protein (a downstream target of mTOR/p70S6K). As shown in Fig. 4A and B, VSMC exposure to increasing concentrations of AdipoRon for 48 hr resulted in robust increases in AMPKThr172 phosphorylation. In particular, AdipoRon treatment at 25, 50 and 100 μM concentrations led to ~4.4, ~5.1 and ~6.7 fold increases in AMPK phosphorylation, respectively. In addition, AdipoRon treatment at similar concentrations resulted in ~5, ~7.5 and ~7.4 fold increases in the phosphorylation of ACC, a downstream target of AMPK (Fig. 4A and B). Notably, AdipoRon-mediated increases in the phosphorylation of AMPK and ACC were accompanied by diminutions in the phosphorylation of S6 ribosomal protein, which were observed at 25 to 100 μM concentrations (Fig. 4A and B). Time course studies with AdipoRon revealed a rapid rise in the phosphorylation of AMPK and ACC as early as 6 min with sustenance in the phosphorylation state of AMPK and ACC for a prolonged time interval (Fig. 4C and D). In addition, AdipoRon abolished S6 phosphorylation at 20 min to 6 hr time points (Fig. 4C and D).

Fig. 4.

Concentration- and time dependent- effects of AdipoRon on the phosphorylation of AMPK, ACC, and S6 in VSMCs. Serum-deprived VSMCs were incubated with: A-B) increasing concentrations of AdipoRon (5 to 100 μM) for 48 hr; or C-D) a fixed concentration of AdipoRon (25 μM) at the indicated time intervals. VSMC lysates were then subjected to immunoblot analysis using primary antibodies specific for pAMPKThr172, AMPK, pACC, ACC, pS6 and S6. β-actin was used as internal control. The data shown in the bar graphs are the means ± SEM. * p < 0.05 compared with control (0 μM AdipoRon) using one-way ANOVA (B) or repeated measures one-way ANOVA (D) followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (n = 3–5).

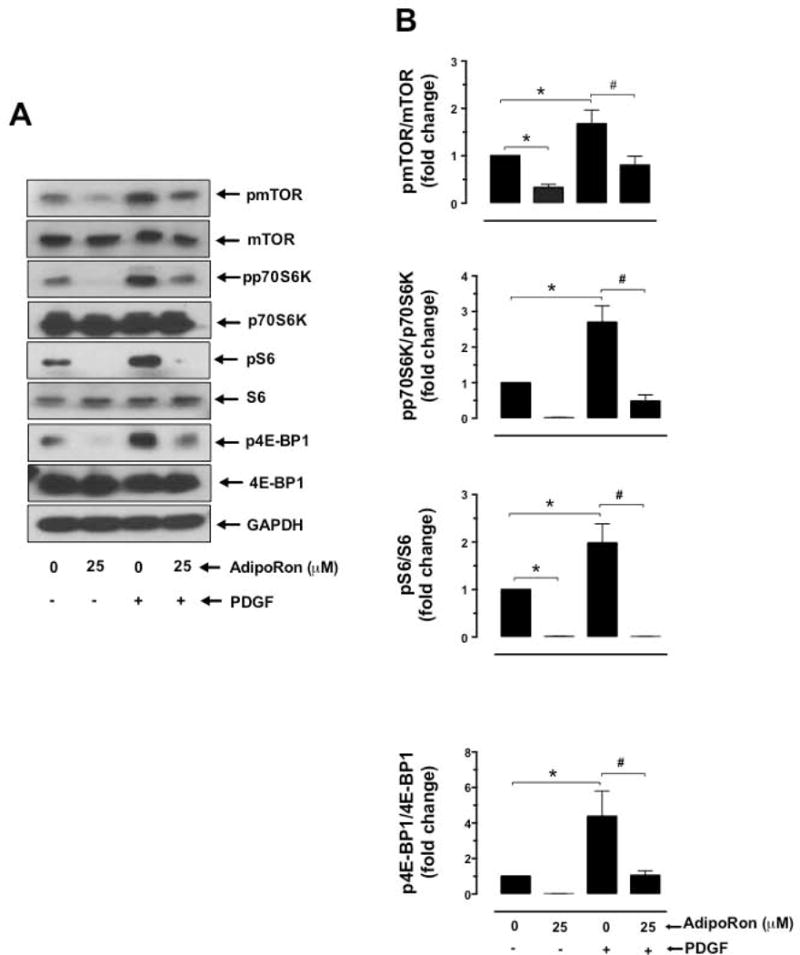

3.4. AdipoRon inhibits basal and/or PDGF-induced acute phosphorylation of mTOR, p70S6K, S6, and 4E-BP1 in VSMCs

To further determine the effects of AdipoRon on mTOR signaling, AdipoRon-treated VSMCs were incubated with or without PDGF to quantify the changes in the phosphorylation state of mTOR and its downstream targets, including p70S6K/S6 ribosomal protein and 4E-BP1. As shown in Figure 5A and B, AdipoRon at 25 μM concentration diminished basal phosphorylation of mTOR by ~67% and completely abolished PDGF-induced phosphorylation of mTOR. In addition, AdipoRon abolished basal and PDGF-induced increases in the phosphorylation of p70S6K, pS6, and 4E-BP1.

Fig. 5.

Effects of AdipoRon on basal and PDGF-induced phosphorylation of mTOR, p70S6K, S6, and 4E-BP1 in VSMCs. A-B) Serum-deprived VSMCs were incubated with AdipoRon (25 μM) for 3 hr followed by stimulation with PDGF (30 ng/ml) for 6 min. VSMC lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis using primary antibodies specific for pmTORSer2448, mTOR, pp70S6K, p70S6K, pS6, S6, p4E-BP1 and 4E-BP1. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The data shown in the bar graphs are the means ± SEM. *, # p < 0.05 compared with control (− PDGF and 0 μM AdipoRon) or PDGF (+ PDGF and 0 μM AdipoRon), respectively, using two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (n = 3).

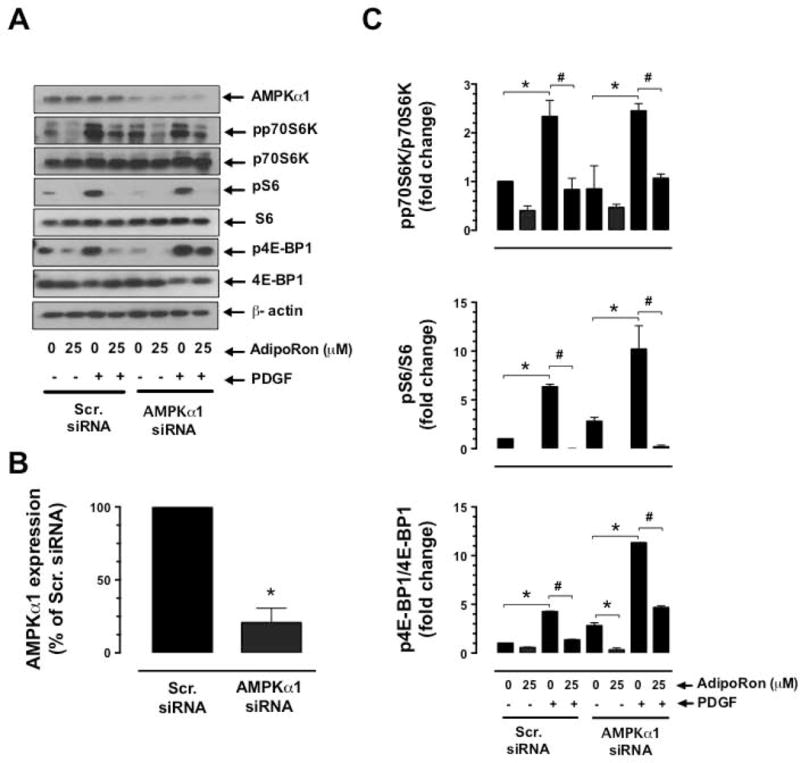

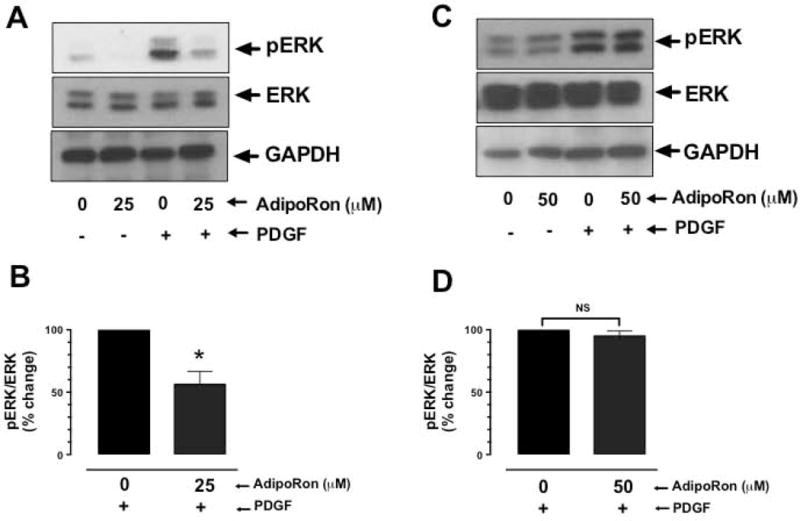

3.5. Target-specific downregulation of AMPK does not affect AdipoRon-mediated diminutions in basal and PDGF-induced mTOR signaling in VSMCs

To determine the cause and effect relationship between AdipoRon-mediated AMPK activation and mTOR inhibition, VSMCs were nucleofected with AMPKα1 siRNA. As shown in Fig. 6A and B, nucleofection with AMPKα1 led to the downregulation of AMPK protein by 79.2%. Under these conditions, AdipoRon-mediated inhibition of basal and PDGF-induced phosphorylation of p70S6K, pS6, and 4E-BP1 and expression of cyclin D1 remained essentially the same as shown in Fig. 6C and D. These findings suggest that AdipoRon attenuates mTOR signaling in VSMCs independent of its role in AMPK activation.

Fig. 6.

Effects of AMPKα1 downregulation on AdipoRon-mediated changes in basal and PDGF-induced mTOR signaling and cyclin D1 expression in VSMCs. VSMCs were transfected with scrambled (Scr.) or AMPKα1 siRNA and maintained in culture for 48 hr. Subsequently, serum-deprived VSMCs were incubated with A-C) AdipoRon (25 μM) for 3 hr followed by stimulation with PDGF (30 ng/ml) for 6 min; or D) Adiporon (25 μM) for 30 min followed by exposure to PDGF (30 ng/ml) for 48 hr. VSMC lysates were then subjected to immunoblot analysis using the primary antibodies specific for AMPKα1, pp70S6K, p70S6K, pS6, S6, p4E-BP1, 4E-BP1 and cyclin D1. β-actin was used as internal control. The data shown in the bar graphs are the means ± SEM. * p < 0.05 compared with control (− PDGF and 0 μM AdipoRon) [C and D] or Scr. siRNA (B). # p < 0.05 compared with PDGF (+ PDGF and 0 μM AdipoRon) [C and D]. Statistical significance was determined by applying unpaired student t test (B) or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (C and D) (n = 3).

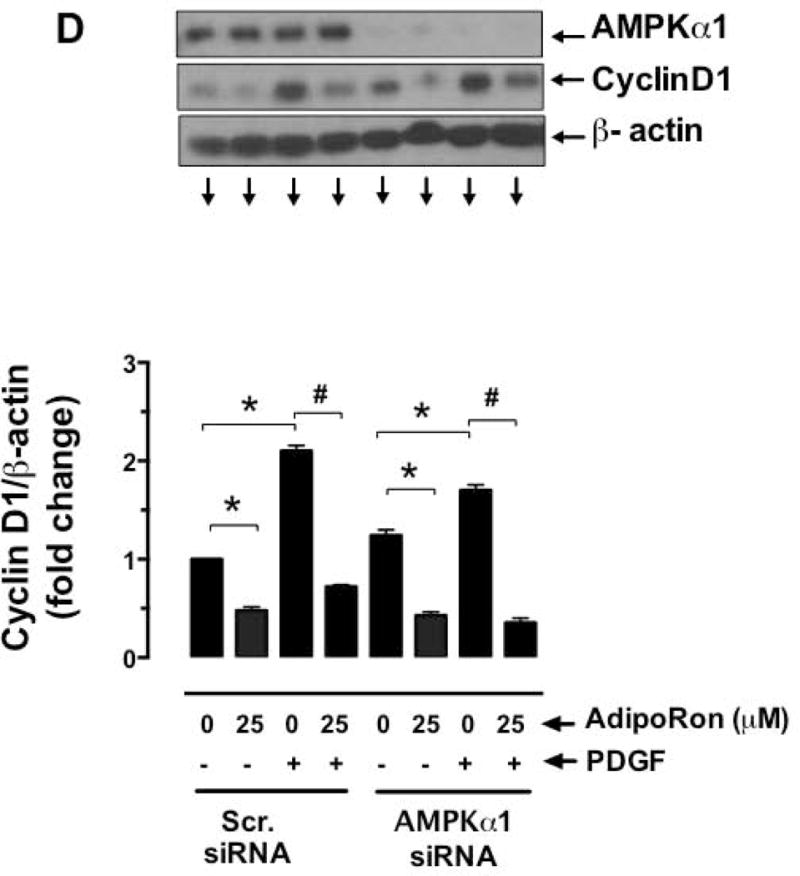

3.6. AdipoRon inhibits basal and PDGF-induced phosphorylation of Akt in VSMCs

Previous studies have shown that sustained inhibition of mTOR signaling results in the activation of feedback regulatory loop involving activation of Akt [26]. To determine whether AdipoRon inhibition of mTOR signaling has such an effect on Akt phosphorylation, AdipoRon-treated (3 hr or 48 hr) VSMCs were stimulated with PDGF for 6 min. As shown in Fig. 7A–B, AdipoRon treatment (25 μM, 3 hr) resulted in a significant decrease in PDGF-induced AktSer473 and AktThr308 phosphorylation by 44% and 29%, respectively. In addition, long-term exposure to AdipoRon (50 μM, 48 hr) led to a significant decrease in PDGF-induced AktThr308 phosphorylation by 61.7% (Fig. 7C–D).

Fig. 7.

Effects of AdipoRon on basal and PDGF-induced phosphorylation of Akt in VSMCs. Serum-deprived VSMCs were incubated with: A-B) AdipoRon (25 μM) for 3 hr or C-D) AdipoRon (50 μM) for 48 hr followed by stimulation with PDGF (30 ng/ml) for 6 min. VSMC lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis using primary antibody specific for pAktSer473, pAktThr308 and Akt. β-actin was used as an internal control. The data shown in the bar graphs are the means ± SEM. * p < 0.05 using unpaired student t test (n = 3).

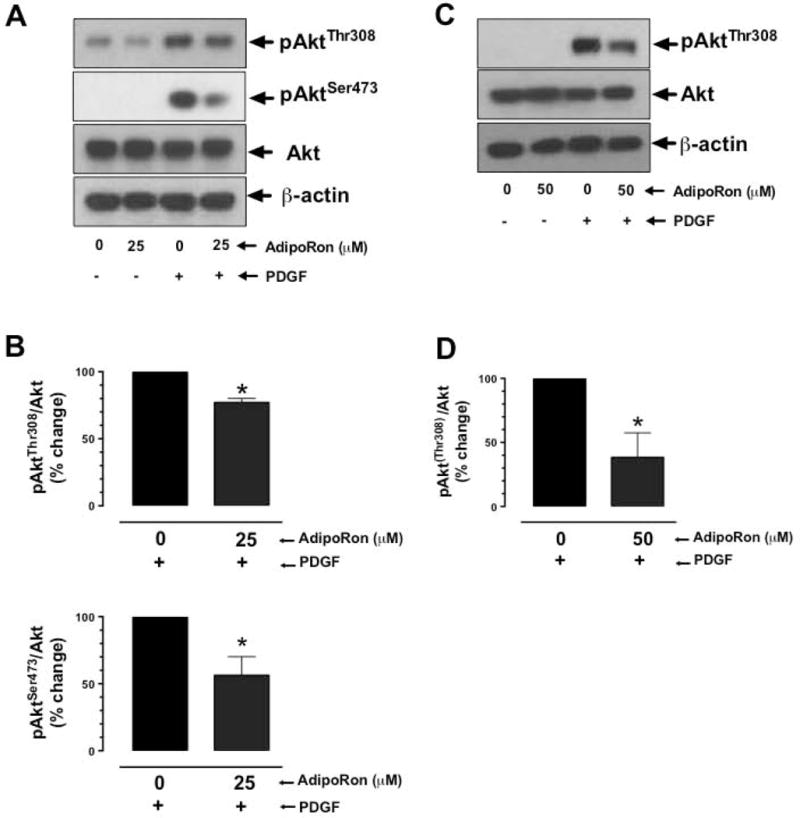

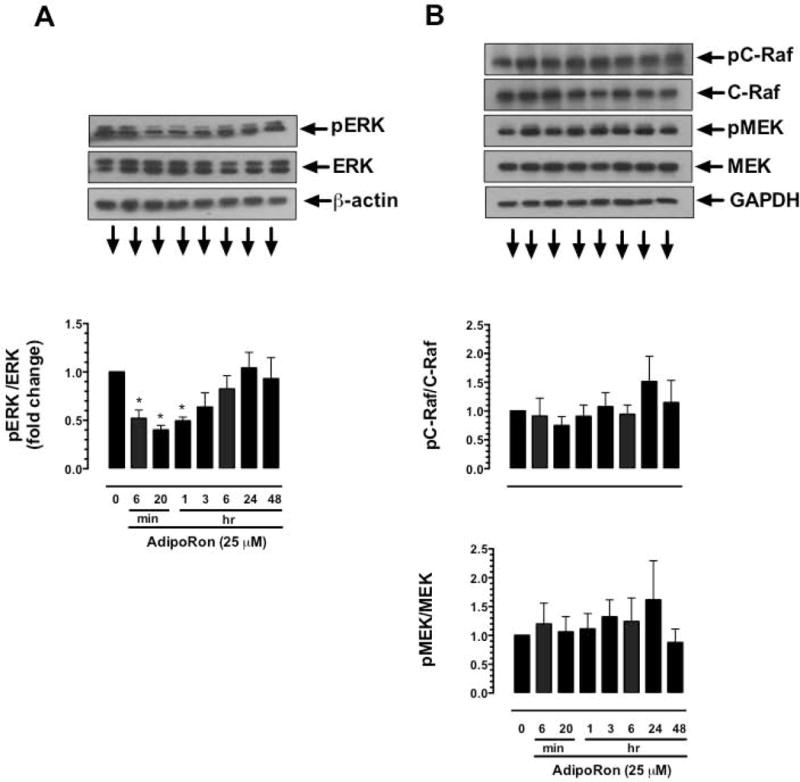

3.7. AdipoRon inhibits basal and PDGF-induced ERK phosphorylation in a transient manner in VSMCs

Inhibition of mTOR signaling has also been shown to result in ERK activation through a feedback regulatory mechanism [27,28]. To determine if AdipoRon inhibition of mTOR signaling has an effect on ERK phosphorylation, AdipoRon-treated (3 hr or 48 hr) VSMCs were stimulated with PDGF for 6 min. Fig. 8A–B shows that in AdipoRon-treated (25 μM, 3 hr) VSMCs, there was a significant decrease in PDGF-induced ERK phosphorylation by 44%. Upon long-term exposure to AdipoRon (50 μM, 48 hr), there was no significant change in PDGF-induced ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 8C–D).

Fig. 8.

Effects of AdipoRon on basal and PDGF-induced phosphorylation of ERK in VSMCs. Serum-deprived VSMCs were incubated with: A-B) AdipoRon (25 μM) for 3 hr or C-D) AdipoRon (50 μM) for 48 hr followed by stimulation with PDGF (30 ng/ml) for 6 min. VSMC lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis using primary antibodies specific for pERK and ERK. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The data shown in the bar graphs are the means ± SEM. * p < 0.05 using unpaired student t test; NS, not significant (n = 3).

To determine the differential effects of AdipoRon on ERK phosphorylation, VSMCs were treated with AdipoRon (25 μM) at increasing time intervals. As shown in Fig. 9A, AdipoRon treatment resulted in a transient inhibition of ERK phosphorylation at earlier time points (by ~50%, ~60% and ~60% at 6 min, 20 min and 1 hr, respectively) followed by restoration of ERK phosphorylation at the later time points (24 hr and 48 hr). To examine whether AdipoRon-mediated transient decrease in ERK phosphorylation is reflected by similar changes in upstream kinases (C-Raf and MEK), time dependency studies were performed to determine the phosphorylation state of C-Raf and MEK. Unlike the findings observed with ERK phosphorylation, AdipoRon treatment did not result in significant changes in the phosphorylation of C-Raf and MEK at any of the indicated time points (Fig. 9B).

Fig. 9.

Time-dependent effects of AdipoRon on the phosphorylation of ERK, C-Raf, and MEK in VSMCs. Serum-deprived VSMCs were incubated with AdipoRon (25 μM) at increasing time intervals (6 min to 48 hr). VSMC lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis using primary antibody specific for A) pERK and ERK or B) pC-Raf and C-Raf or pMEK and MEK. β-actin or GAPDH was used as internal controls. The data shown in the bar graphs are the means ± SEM. * p < 0.05 using repeated measures one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (n = 3).

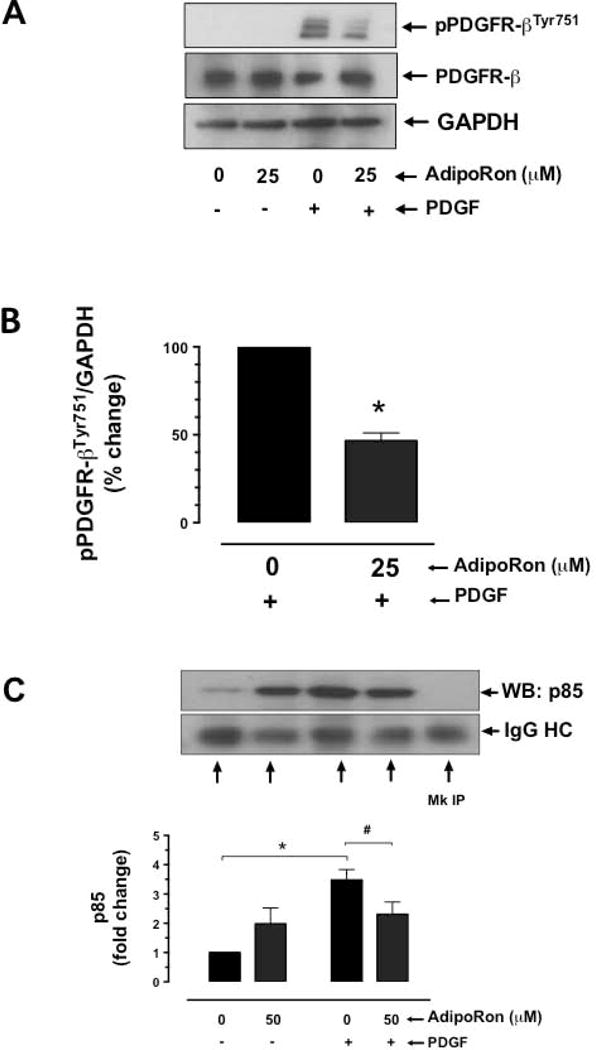

3.8. AdipoRon inhibits PDGF receptor tyrosine phosphorylation and its association with p85 adapter subunit of PI 3-kinase in VSMCs

Previous studies have shown that adiponectin inhibits PDGF receptor-β autophosphorylation with an accompanying decrease in ERK phosphorylation [29]. In the present study, exposure of VSMCs to AdipoRon at 25 μM concentration led to a significant decrease in PDGF-induced phosphorylation of PDGFRTyr751 by ~53.4%, as revealed by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 10A and B). In addition, immunoprecipitation studies revealed a significant decrease in the association of PDGF receptor with the p85 adapter subunit of PI 3-kinase by 47% (Fig. 10C).

Fig. 10.

Effect of AdipoRon on PDGFR-β tyrosine phosphorylation and its association with p85 adaptor subunit of PI 3-kinase in VSMCs. A-B) Serum-deprived VSMCs were incubated with AdipoRon (25 μM) for 3 hr followed by stimulation with PDGF (30 ng/ml) for 6 min. VSMC lysates were then subjected to immunoblot analysis using primary antibodies specific for p-PDGFR-βTyr751 and PDGFR-β. GAPDH was used as internal control. C) Serum-deprived VSMCs were incubated with AdipoRon (50 μM) for 48 hr followed by stimulation with PDGF (30 ng/ml) for 2 min. The cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using PDGFR-β primary antibody and then probed with p85 primary antibody. The data shown in the bar graphs are the means ± SEM. *, # p < 0.05 compared with control (− PDGF and/or 0 μM AdipoRon) or PDGF (+ PDGF and 0 μM AdipoRon), respectively, using unpaired student t test (B) or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (C) [n = 3]. MC = Mock, HC = heavy chain.

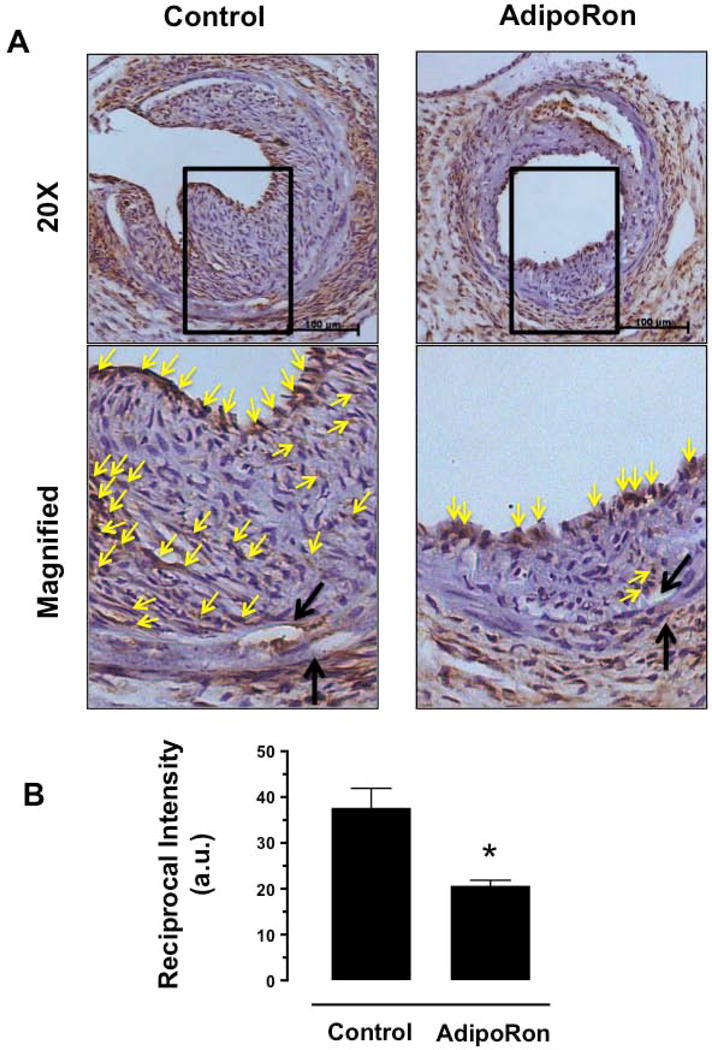

3.9. AdipoRon attenuates S6 phosphorylation in the neointimal layer of injured femoral artery

Since AdipoRon inhibited mTOR/p70S6K signaling in VSMCs independent of AMPK (as illustrated in Fig. 6), we next examined the phosphorylation state of S6 ribosomal protein (a downstream target of mTOR/p70S6K signaling) in the injured femoral artery. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed a significant decrease in S6 phosphorylation in the neointimal layer in AdipoRon-treated group, compared with control (Fig. 11A and B). In conjunction with the observed findings from VSMCs in vitro, these data suggest that the decrease in mTOR/p70S6K signaling may contribute in part to AdipoRon inhibition of neointima formation in the injured artery.

Fig. 11.

Effects of AdipoRon on the phosphorylation state of S6 ribosomal protein in the injury femoral artery. The femoral artery sections from AdipoRon-treated and control mice were subjected to immunohistochemical analysis using primary antibody specific for pS6. A) The representative images of pS6 immunoreactivity were visualized using diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining at a magnification 20x. The scale bars represent 100 μm (upper panel). Black arrows indicate internal and external elastic laminae; yellow arrows indicate pS6 (lower panel). B) The intensity of pS6 staining was quantified and expressed as reciprocal intensities. The data shown in the bar graph are the means ± SEM. * p < 0.05 using unpaired t-test (n = 3). a. u. = arbitrary units.

Discussion

The present findings reveal that oral administration of AdipoRon, a small-molecule adiponectin receptor agonist, attenuates neointima formation in the injured femoral artery in C57BL/6J mice. Under in vitro conditions, AdipoRon inhibits PDGF-induced VSMC proliferation through mechanisms involving AMPK-independent inhibition of mTOR/p70S6K/S6 signaling (Fig. 12). In particular, AdipoRon induces a rapid and sustained phosphorylation of AMPK and its downstream target, ACC. In addition, AdipoRon inhibits PDGF-induced phosphorylation of mTOR and its downstream targets, including p70S6K/S6 and 4E-BP1. These inhibitory effects on the phosphorylation of p70S6K/S6 and 4E-BP1 signaling components are persistent even after target-specific downregulation of endogenous AMPK using siRNA, suggesting AMPK-independent effects for AdipoRon inhibition of PDGF-induced mTOR signaling and cyclin D1 expression in VSMCs. Furthermore, AdipoRon treatment results in a sustained and transient decrease in PDGF-induced phosphorylation of Akt and ERK, respectively. Importantly, PDGF receptor-β tyrosine phosphorylation, which controls the phosphorylation state of Akt and ERK, is diminished upon AdipoRon treatment. Thus, AdipoRon has the potential to inhibit key proliferative signaling events, including mTOR/p70S6K, induced in response to PDGF, a potent mitogen released at the site of arterial injury [30,31].

Fig. 12.

AdipoRon inhibits VSMC proliferation through AMPK-independent inhibition of mTOR/p70S6K signaling. AdipoRon activates AMPK and inhibits basal and PDGF-induced mTOR/p70S6K signaling. AMPK downregulation by target-specific siRNA shows persistent inhibition of mTOR signaling in VSMCs.

In conjunction with several previous reports that document the ability of adiponectin to inhibit PDGF-induced VSMC proliferation [6,16–18], the present findings suggest that AdipoRon may provide a novel treatment option to attenuate exaggerated VSMC proliferation. From a mechanistic standpoint, adiponectin has been shown to have multiple targets that contribute to inhibition of VSMC proliferation. First, full length adiponectin binds with PDGF-BB (a potent VSMC mitogen), thereby inhibiting its association with PDGF receptor in VSMCs [17]. In particular, high molecular weight and medium molecular weight forms of adiponectin bind with PDGF-BB, thereby precluding its bioavailability at the pre-receptor level [18]. Second, full length adiponectin has been shown to inhibit autophosphorylation of PDGF receptor-β and the activation of its downstream effector, ERK [17]. Third, adiponectin inhibition of PDGF-induced VSMC proliferation does not require adiponectin receptors (AdipoR1 and/or AdipoR2), as evidenced in studies involving target-specific downregulation of AdipoR1/R2 [18]. Fourth, treatment of VSMCs with adiponectin leads to the activation of AMPK [13,32], which is implicated in the suppression of VSMC proliferation [14,15,33]. Although AdipoRon activates AMPK in a robust and sustained manner in VSMCs, it inhibits PDGF-induced VSMC proliferation through an AMPK-independent mechanism.

It is noteworthy that both adiponectin and AdipoRon promote AMPK activation in VSMCs. Yet, they exhibit differences in the temporal activation of AMPK. For instance, recombinant full-length adiponectin has been shown to enhance AMPKThr172 phosphorylation at 30 min and 6–12 hr time points in rat aortic VSMCs [34] and human aortic VSMCs [32], respectively. In a different study, treatment with full-length adiponectin enriched in HMW oligomers, but not truncated globular adiponectin, leads to a detectable increase in AMPKThr172 phosphorylation at the 24 time point in human coronary artery VSMCs [13]. Regardless of the monomeric or oligomeric forms, adiponectin requires a much longer time frame to enhance AMPKThr172 phosphorylation in VSMCs. In contrast to adiponectin, AdipoRon enhances AMPKThr172 phosphorylation as early as 6 min, which remains elevated in a sustained manner for up to 48 hr in human aortic VSMCs (present study). These findings are consistent with the recent observations of a rapid rise in AMPKThr172 phosphorylation in AdipoRon-treated mouse myoblast C2C12 cell line [9]. As expected, the increase in AMPKThr172 phosphorylation by adiponectin or AdipoRon results in enhanced phosphorylation of ACC (a downstream target of AMPK). It is likely that the differences in the temporal activation of AMPK by adiponectin and AdipoRon are attributable to the differential activation of proximal signaling events, including adipoR1/R2 and LKB1 [35], in VSMCs.

Studies by several investigators, including our recent findings, have shown that AMPK activation results in the suppression of mTOR/p70S6K signaling in different tissues/cell types [36,37], including VSMCs [14,15]. Importantly, adiponectin- or AdipoRon-mediated AMPK activation is associated with inhibition of mTOR/p70S6K signaling in VSMCs. Yet, there are differences in the cause and effect relationship between these two signaling events depending on the agonist. For instance, adiponectin-mediated AMPK activation leads to inhibition of mTOR/p70S6K signaling in human coronary or femoral artery VSMCs, as evidenced in experimental approaches involving the use of pharmacological agents (e.g., compound C, an AMPK inhibitor) or target-specific siRNAs [13,38]. In the present study involving AMPK downregulation by target-specific siRNA, AdipoRon-mediated decrease in mTOR signaling remains essentially unaltered. This is revealed by persistent decreases in the phosphorylation state of p70S6K/S6 and 4E-BP1 signaling components under basal and PDGF-stimulated conditions. Taken together, although AMPK activation by adiponectin is critical for the suppression of mTOR/p70S6K signaling [13,38], AdipoRon-mediated inhibition of mTOR/p70S6K signaling occurs independent of AMPK activation in VSMCs.

Previous studies have documented the existence of a negative feedback regulatory loop whereby inhibition of mTOR/p70S6K signaling results in the activation of Akt in different cell types under normal and diseased states [26–28]. Notably, adiponectin-mediated inhibition of mTOR/p70S6K signaling is associated with Akt activation (at 4–24 hour time points) in human coronary artery VSMCs [13]. In addition, adiponectin overexpression diminishes p70S6K signaling with an accompanying increase in Akt phosphorylation in VSMCs [39]. However, in a different study, adiponectin does not affect Akt phosphorylation in human VSMCs [32]. Furthermore, C1q/TNF-related protein-9 (CTRP9), an adipocytokine and a conserved paralog of adiponectin, fails to activate Akt in human VSMCs [40]. In the present study, acute or prolonged treatment with AdipoRon leads to inhibition of PDGF-induced Akt phosphorylation in VSMCs. Together, in the absence of an apparent negative feedback regulatory loop, AdipoRon treatment may inhibit PDGF receptor-mediated proximal signaling components, including Akt in VSMCs.

Although inhibition of mTOR/p70S6K or PI 3-kinase may lead to ERK inhibition [41] or ERK activation [26–28] in different cell types, studies with adiponectin demonstrate its inhibitory effects on PDGF-induced ERK phosphorylation in human VSMCs [17]. In addition, adiponectin attenuates IGF1-induced ERK phosphorylation in rat aortic VSMCs [34]. However, in a different study, adiponectin induces ERK phosphorylation in porcine coronary artery VSMCs [42]. In the present study, AdipoRon treatment between 6 min and 48 hr does not affect the basal phosphorylation of C-Raf and MEK, the kinases upstream of ERK. However, AdipoRon treatment results in a transient decrease in basal ERK phosphorylation at 6–60 min time points with a reversal to the pre-existing phosphorylation state at 24–48 hr time points. Accordingly, acute exposure to AdipoRon inhibits PDGF-induced ERK phosphorylation, whereas prolonged treatment with AdipoRon does not result in significant changes in PDGF-induced ERK phosphorylation. At this juncture, it is important to note that a transient decrease in ERK phosphorylation followed by its reactivation has been evidenced in recent studies with a PI 3-kinase inhibitor [27,28]. Further studies are clearly warranted to determine AdipoRon regulation of PI 3-kinase activity and its relationship with C-Raf/MEK-independent ERK signaling [43,44] in VSMCs.

Furthermore, AdipoRon inhibits PDGF receptor-β tyrosine phosphorylation in VSMCs, as has been evidenced in previous studies with adiponectin [17]. Since adiponectin inhibits PDGF ligand association with PDGF receptor [17,18] and activates protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B [45], future studies should determine which of these two mechanisms mediates AdipoRon inhibition of PDGF receptor-β tyrosine phosphorylation. Importantly, this decrease in PDGF receptor tyrosine phosphorylation may contribute in part to the observed inhibitory effects of AdipoRon on: i) the association of p85 (adapter subunit of PI 3-kinase) with the activated PDGF receptor; ii) Akt activation; and iii) mTOR/p70S6K/S6 and 4E-BP1 signaling in VSMCs.

In conclusion, the present findings strongly suggest that orally-administered AdipoRon has the potential to limit restenosis after angioplasty at the lesion site by targeting VSMC proliferative signaling events, including mTOR/p70S6K. Although AdipoRon activates AMPK reminiscent of adiponectin action, AMPK activation does not play an intermediary role toward AdipoRon-mediated inhibition of VSMC proliferation. In a recent study, AdipoRon has been shown to promote vascular smooth muscle relaxation through AMPK-independent mechanism [25]. In view of the reported beneficial effects of AdipoRon in improving glycemic control in type 2 diabetic mice [9], strategies that utilize this small-molecule to suppress exaggerated VSMC proliferation may provide a realistic alternative to rapamycin/sirolimus (an mTOR inhibitor), which has been shown to exhibit adverse effects including glucose intolerance and diabetes in rodent models [46,47].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/National Institutes of Health Grant (R01-HL-097090) and University of Georgia Research Foundation Fund. AF was supported by a Scholarship from Umm Al-Qura University, Mecca, Saudi Arabia.

Abbreviations

- VSMCs

vascular smooth muscle cells

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- ACC

acetyl CoA carboxylase

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- p70S6K

p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase

- S6

S6 ribosomal protein

- 4E-BP1

eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- PI 3-kinase

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- EVG

elastic van gieson

- H&E

haematoxylin and eosin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hotta K, Funahashi T, Bodkin NL, Ortmeyer HK, Arita Y, Hansen BC, Matsuzawa Y. Circulating concentrations of the adipocyte protein adiponectin are decreased in parallel with reduced insulin sensitivity during the progression to type 2 diabetes in rhesus monkeys. Diabetes. 2001;50:1126–1133. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.5.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Otsuka F, Sugiyama S, Kojima S, Maruyoshi H, Funahashi T, Matsui K, Sakamoto T, Yoshimura M, Kimura K, Umemura S, Ogawa H. Plasma adiponectin levels are associated with coronary lesion complexity in men with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1155–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Eynatten M, Humpert PM, Bluemm A, Lepper PM, Hamann A, Allolio B, Nawroth PP, Bierhaus A, Dugi KA. High-molecular weight adiponectin is independently associated with the extent of coronary artery disease in men. Atherosclerosis. 2008;199:123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitta Y, Takano H, Nakamura T, Kodama Y, Umetani K, Fujioka D, Saito Y, Kawabata K, Obata JE, Mende A, Kobayashi T, Kugiyama K. Low adiponectin levels predict late in-stent restenosis after bare metal stenting in native coronary arteries. Int J Cardiol. 2008;131:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Yamauchi T, Kubota T, Moroi M, Matsui J, Eto K, Yamashita T, Kamon J, Satoh H, Yano W, Froguel P, Nagai R, Kimura S, Kadowaki T, Noda T. Disruption of adiponectin causes insulin resistance and neointimal formation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25863–25866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200251200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuda M, Shimomura I, Sata M, Arita Y, Nishida M, Maeda N, Kumada M, Okamoto Y, Nagaretani H, Nishizawa H, Kishida K, Komuro R, Ouchi N, Kihara S, Nagai R, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y. Role of adiponectin in preventing vascular stenosis. The missing link of adipo-vascular axis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37487–37491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okamoto Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Nishida M, Arita Y, Kumada M, Ohashi K, Sakai N, Shimomura I, Kobayashi H, Terasaka N, Inaba T, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y. Adiponectin reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Circulation. 2002;106:2767–2770. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000042707.50032.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holland WL, Scherer PE. Cell biology. Ronning after the adiponectin receptors. Science. 2013;342:1460–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.1249077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okada-Iwabu M, Yamauchi T, Iwabu M, Honma T, Hamagami K, Matsuda K, Yamaguchi M, Tanabe H, Kimura-Someya T, Shirouzu M, Ogata H, Tokuyama K, Ueki K, Nagano T, Tanaka A, Yokoyama S, Kadowaki T. A small-molecule adipor agonist for type 2 diabetes and short life in obesity. Nature. 2013;503:493–499. doi: 10.1038/nature12656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Zhao J, Li R, Lau WB, Yuan YX, Liang B, Li R, Gao EH, Koch WJ, Ma XL, Wang YJ. Adiporon, the first orally active adiponectin receptor activator, attenuates post-ischemic myocardial apoptosis through both AMPK-mediated and AMPK-independent signalings. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2015;309:E275–E282. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00577.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors. Endocrine Reviews. 2005;26:439–451. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Minokoshi Y, Ito Y, Waki H, Uchida S, Yamashita S, Noda M, Kita S, Ueki K, Eto K, Akanuma Y, Froguel P, Foufelle F, Ferre P, Carling D, Kimura S, Nagai R, Kahn BB, Kadowaki T. Adiponectin stimulates glucose utilization and fatty-acid oxidation by activating amp-activated protein kinase. Nature Med. 2002;8:1288–1295. doi: 10.1038/nm788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding M, Xie Y, Wagner RJ, Jin Y, Carrao AC, Liu LS, Guzman AK, Powell RJ, Hwa J, Rzucidlo EM, Martin KA. Adiponectin induces vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation via repression of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 and foxo4. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1403–1410. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.216804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim EJ, Choi YK, Han YH, Kim HJ, Lee IK, Lee MO. Roralpha suppresses proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells through activation of amp-activated protein kinase. Int J Cardiol. 2014;175:515–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osman I, Segar L. Pioglitazone, a ppargamma agonist, attenuates pdgf-induced vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation through ampk-dependent and ampk-independent inhibition of mtor/p70s6k and erk signaling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;101:54–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anfossi G, Russo I, Doronzo G, Pomero A, Trovati M. Adipocytokines in atherothrombosis: Focus on platelets and vascular smooth muscle cells. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:174341. doi: 10.1155/2010/174341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Maeda K, Kuriyama H, Okamoto Y, Kumada M, Hotta K, Nishida M, Takahashi M, Nakamura T, Shimomura I, Muraguchi M, Ohmoto Y, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y. Adipocyte-derived plasma protein adiponectin acts as a platelet-derived growth factor-bb-binding protein and regulates growth factor-induced common postreceptor signal in vascular smooth muscle cell. Circulation. 2002;105:2893–2898. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000018622.84402.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Lam KS, Xu JY, Lu G, Xu LY, Cooper GJ, Xu A. Adiponectin inhibits cell proliferation by interacting with several growth factors in an oligomerization-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18341–18347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sata M, Maejima Y, Adachi F, Fukino K, Saiura A, Sugiura S, Aoyagi T, Imai Y, Kurihara H, Kimura K, Omata M, Makuuchi M, Hirata Y, Nagai R. A mouse model of vascular injury that induces rapid onset of medial cell apoptosis followed by reproducible neointimal hyperplasia. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:2097–2104. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shawky NM, Pichavaram P, Shehatou GS, Suddek GM, Gameil NM, Jun JY, Segar L. Sulforaphane improves dysregulated metabolic profile and inhibits leptin-induced vsmc proliferation: Implications toward suppression of neointima formation after arterial injury in western diet-fed obese mice. J Nutr Biochem. 2016;32:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen D. Quantifying chromogen intensity in immunohistochemistry via reciprocal intensity. 2013 http://www.nature.com/protocolexchange/protocols/2931.

- 22.Pyla R, Poulose N, Jun JY, Segar L. Expression of conventional and novel glucose transporters, glut1, −9, −10, and −12, in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;304:C574–589. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00275.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishizawa K, Izawa Y, Ito H, Miki C, Miyata K, Fujita Y, Kanematsu Y, Tsuchiya K, Tamaki T, Nishiyama A, Yoshizumi M. Aldosterone stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via big mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 activation. Hypertension. 2005;46:1046–1052. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000172622.51973.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho KJ, Owens CD, Longo T, Sui XX, Ifantides C, Conte MS. C-reactive protein and vein graft disease: Evidence for a direct effect on smooth muscle cell phenotype via modulation of pdgf receptor-beta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H1132–H1140. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00079.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong K, Lee S, Li R, Yang Y, Tanner MA, Wu J, Hill MA. Adiponectin receptor agonist, adiporon, causes vasorelaxation predominantly via a direct smooth muscle action. Microcirculation. 2016;23:207–220. doi: 10.1111/micc.12266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang H, Bajraszewski N, Wu E, Wang H, Moseman AP, Dabora SL, Griffin JD, Kwiatkowski DJ. Pdgfrs are critical for pi3k/akt activation and negatively regulated by mtor. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:730–738. doi: 10.1172/JCI28984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carracedo A, Ma L, Teruya-Feldstein J, Rojo F, Salmena L, Alimonti A, Egia A, Sasaki AT, Thomas G, Kozma SC, Papa A, Nardella C, Cantley LC, Baselga J, Pandolfi PP. Inhibition of mtorc1 leads to mapk pathway activation through a pi3k-dependent feedback loop in human cancer. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3065–3074. doi: 10.1172/JCI34739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Will M, Qin AC, Toy W, Yao Z, Rodrik-Outmezguine V, Schneider C, Huang X, Monian P, Jiang X, de Stanchina E, Baselga J, Liu N, Chandarlapaty S, Rosen N. Rapid induction of apoptosis by pi3k inhibitors is dependent upon their transient inhibition of ras-erk signaling. Cancer Discovery. 2014;4:334–347. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Maeda K, Kuriyama H, Okamoto Y, Kumada M, Hotta K, Nishida M, Takahashi M. Adipocyte-derived plasma protein adiponectin acts as a platelet-derived growth factor-bb-binding protein and regulates growth factor-induced common postreceptor signal in vascular smooth muscle cell. Circulation. 2002;105:2893–2898. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000018622.84402.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubin K, Tingstrom A, Hansson GK, Larsson E, Ronnstrand L, Klareskog L, Claesson-Welsh L, Heldin CH, Fellstrom B, Terracio L. Induction of b-type receptors for platelet-derived growth factor in vascular inflammation: Possible implications for development of vascular proliferative lesions. Lancet. 1988;1:1353–1356. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heldin CH, Westermark B. Mechanism of action and in vivo role of platelet-derived growth factor. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1283–1316. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Son BK, Akishita M, Iijima K, Kozaki K, Maemura K, Eto M, Ouchi Y. Adiponectin antagonizes stimulatory effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha on vascular smooth muscle cell calcification: Regulation of growth arrest-specific gene 6-mediated survival pathway by adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase. Endocrinology. 2008;149:1646–1653. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stone JD, Narine A, Shaver PR, Fox JC, Vuncannon JR, Tulis DA. Amp-activated protein kinase inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration and vascular remodeling following injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H369–381. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00446.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Motobayashi Y, Izawa-Ishizawa Y, Ishizawa K, Orino S, Yamaguchi K, Kawazoe K, Hamano S, Tsuchiya K, Tomita S, Tamaki T. Adiponectin inhibits insulin-like growth factor-1-induced cell migration by the suppression of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation, but not akt in vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertens Res. 2009;32:188–193. doi: 10.1038/hr.2008.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T. Adiponectin receptor signaling: A new layer to the current model. Cell Metab. 2011;13:123–124. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inoki K, Kim J, Guan KL. Ampk and mtor in cellular energy homeostasis and drug targets. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:381–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saha AK, Xu XJ, Lawson E, Deoliveira R, Brandon AE, Kraegen EW, Ruderman NB. Downregulation of ampk accompanies leucine- and glucose-induced increases in protein synthesis and insulin resistance in rat skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2010;59:2426–2434. doi: 10.2337/db09-1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhan JK, Wang YJ, Wang Y, Tang ZY, Tan P, Huang W, Liu YS. Adiponectin attenuates the osteoblastic differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells through the ampk/mtor pathway. Exp Cell Res. 2014;323:352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ding M, Carrao AC, Wagner RJ, Xie Y, Jin Y, Rzucidlo EM, Yu J, Li W, Tellides G, Hwa J, Aprahamian TR, Martin KA. Vascular smooth muscle cell-derived adiponectin: A paracrine regulator of contractile phenotype. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:474–484. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uemura Y, Shibata R, Ohashi K, Enomoto T, Kambara T, Yamamoto T, Ogura Y, Yuasa D, Joki Y, Matsuo K, Miyabe M, Kataoka Y, Murohara T, Ouchi N. Adipose-derived factor ctrp9 attenuates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointimal formation. FASEB J. 2013;27:25–33. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-213744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doronzo G, Viretto M, Russo I, Mattiello L, Di Martino L, Cavalot F, Anfossi G, Trovati M. Nitric oxide activates pi3-k and mapk signalling pathways in human and rat vascular smooth muscle cells: Influence of insulin resistance and oxidative stress. Atherosclerosis. 2011;216:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fuerst M, Taylor CG, Wright B, Tworek L, Zahradka P. Inhibition of smooth muscle cell proliferation by adiponectin requires proteolytic conversion to its globular form. J Endocrinol. 2012;215:107–117. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huser M, Luckett J, Chiloeches A, Mercer K, Iwobi M, Giblett S, Sun XM, Brown J, Marais R, Pritchard C. Mek kinase activity is not necessary for raf-1 function. EMBO J. 2001;20:1940–1951. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grammer TC, Blenis J. Evidence for mek-independent pathways regulating the prolonged activation of the erk-map kinases. Oncogene. 1997;14:1635–1642. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beales IL, Garcia-Morales C, Ogunwobi OO, Mutungi G. Adiponectin inhibits leptin-induced oncogenic signalling in oesophageal cancer cells by activation of ptp1b. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;382:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Houde VP, Brule S, Festuccia WT, Blanchard PG, Bellmann K, Deshaies Y, Marette A. Chronic rapamycin treatment causes glucose intolerance and hyperlipidemia by upregulating hepatic gluconeogenesis and impairing lipid deposition in adipose tissue. Diabetes. 2010;59:1338–1348. doi: 10.2337/db09-1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schindler CE, Partap U, Patchen BK, Swoap SJ. Chronic rapamycin treatment causes diabetes in male mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;307:R434–443. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00123.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]